Abstract

European Union (EU) countries are struggling with the high costs of operating healthcare facilities due to energy consumption. The rational use of resources, including renewable energy sources (RESs), is a goal of sustainable development in terms of solving environmental problems. There are few literature studies that analyze the impact of the use of RESs in the healthcare sector on the achievement of sustainable development goals in EU countries. This study examines the potential of RESs to address environmental challenges in EU healthcare systems and their impact on the Healthcare Index (HI). A quantitative analysis explores the relationship between the Environmental Performance Index (EPI), Environmental Health Score (EHS) and HI. Data were taken from Yale Center for Environmental Law and Policy (YCELP), European Environment Agency (EEA), and the Numbeo. This study assessed the relationship by using SPSS 29. This study concluded that RESs should be prioritized in healthcare facilities to increase environmental performance and thus meet sustainable development goals. The use of RESs affects environmental performance and improves HI. The results indicate significant positive correlations, highlighting the benefits of RES adoption for both environmental and health indicators.

1. Introduction

Sustainable development has become an important concept in healthcare in recent years. In healthcare, sustainable development means using resources efficiently and reducing waste. It also involves improving health outcomes that will last for future generations [1]. This approach ensures that healthcare systems are resilient and can continue to deliver benefits over time [2].

The functioning of health systems cannot be analyzed in isolation from the environ-mental and social context, as population health and quality of care are closely linked to the assumptions of sustainable development [3]. Achieving high-quality healthcare re-quires not only proper organization but also taking into account factors such as environmental factors. Lack of analysis of environmental factors increases the demand for medical services and leads to facility overload, longer waiting times and a decrease in the quality of care. Scientific studies indicate that countries with better environmental quality with higher EPI values are characterized by better health outcomes and a lower burden on their health systems, which promotes a higher level of quality of care [4]. An important element shaping the quality of healthcare is energy infrastructure. A stable supply of energy is essential for the functioning of diagnostic systems, maintaining the cold chain for medicines and vaccines, operating theaters and intensive care units. Research shows that facilities using RESs—particularly photovoltaic systems with energy storage—achieve greater energy stability, fewer service interruptions, and greater operational efficiency [5,6].

The literature emphasizes that the organization of the health system is crucial for the quality of care [7]. However, the sustainable approach broadens this perspective by pointing out that health systems, according to WHO guidelines, must not only be effective but also resilient, innovative and in line with the principles of social responsibility. By incorporating the principles of sustainable development in the organization of healthcare, the quality of healthcare is influenced by, among others, investments in modern infrastructure and health promotion and disease prevention through a health-promoting environment.

Improving environmental indicators (e.g., EPI) not only promotes public health but also reduces pressure on the healthcare system, enabling improvements in service quality. This means that policies promoting environmental sustainability are also policies for im-proving the quality of care [8]. However, the relationship between health and the environment is not only unidirectional. The healthcare sector itself has a substantial impact on environmental conditions.

The healthcare sector is a major contributor to global carbon emissions, accounting for approximately 5.2% of total carbon emissions, as reported by the Lancet Report published in 2022 [3]. This highlights the urgent need for healthcare facilities to adopt more environmentally friendly practices and actively reduce their carbon footprint [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. The use of RESs is undertaken for many reasons, mainly out of concern for the environment in pursuit of sustainable development goals, but also because of the desire to reduce operating costs [12,13,14,15,16]. In terms of levelized cost of energy (LCOE), RESs remained the most cost-competitive option for new energy generation in 2024 [17]. In addition, investing in modern technologies can contribute to reducing energy consumption and the overall environmental impact of healthcare services [18,19,20]. It aims to address major issues such as reducing environmental damage, reducing social inequalities, and overcoming economic difficulties [18] meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs [12,18,21].

The specific research questions of our study are presented below.

- Does the use of RESs translate into better functioning of the healthcare system as measured by the HI?

- Is there a relationship between the EPI and the HI?

- Is there a relationship between environmental health outcomes and the HI?

- Do countries with higher EPI values have higher healthcare indicators?

A gap in the existing literature was identified regarding the indicators that influence the HI. Therefore, the next section of this article discusses multiple variables that affect the HI. This study was conducted to examine and explain the impact of sustainable practices on the HI in EU member states.

2. Literature Review

Many EU member states are heavily dependent on fossil fuels for energy production, making them a major contributor to greenhouse gas emissions [22,23,24,25,26]. For example, in 2023, approximately 73% of Poland’s energy came from fossil fuels, which is a major obstacle to reducing the country’s dependence on fossil fuels and transitioning to clean energy, a sustainable energy source [27]. In countries with a high share of fossil fuels in their energy mix, healthcare systems are heavily dependent on fossil fuels, causing healthcare facilities to face rising energy costs and environmental problems. It is therefore natural that there is an urgent need to the adopt more sustainable energy practices [27,28,29].

The use of renewable energy in healthcare has broader implications for environmental sustainability and public health [6,30]. By reducing greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution, renewable energy systems contribute to improved air quality and a reduction in respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, which are common in areas with high levels of coal-based energy production [11,31,32]. This, in turn, reduces the financial burden on the healthcare system, freeing up resources for other health priorities. In addition, the transition to RESs supports the creation of green jobs and local economic development, contributing to sustainable social and economic development [33,34].

Healthcare facilities generate significant amounts of waste, much of which is energy-intensive to manage and dispose of. By using waste-to-energy technologies such as anaerobic digestion or energy recovery incineration, healthcare facilities can convert waste into usable energy, reducing both the amount of waste and their dependence on external energy sources [29,35,36].

For example, organic waste from hospital kitchens can be processed through anaerobic digestion to produce biogas that can be used for heating or electricity generation [37,38]. However, waste management in healthcare is not common practice. Lack of awareness among medical staff and the general public about the proper handling of medical waste, lack of effective regulatory frameworks and national policies, as well as financial constraints are the main obstacles to proper healthcare waste management (HCWM). All these factors increase the risk of threats to the environment and public health [39].

The need for change in energy use illustrates the role of renewable energy as a fundamental element of sustainable development [40,41]. RESs contribute to sustainable development by reducing the dependence of industry, services, and healthcare on fossil fuels and promoting waste management through circular economy practices. However, challenges such as limited current funding, geographical constraints, and high initial investments require political support and incentives to maximize their impact.

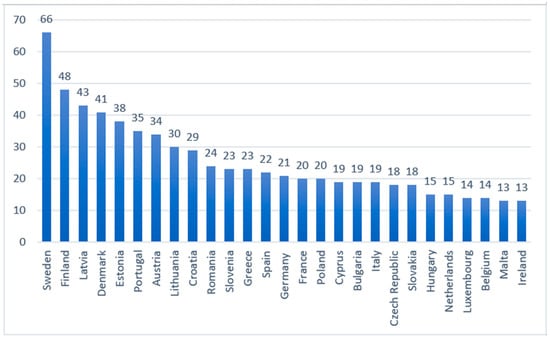

The latest data shows the share of RESs in total energy consumption in some EU-27 countries. According to statistics from Eurostat and the Central Statistical Office in Warsaw, Sweden is the EU leader in renewable energy use, with RESs accounting for 66% of its energy consumption in 2023. In the EU, countries such as Finland (48%), Latvia (43%), Denmark (41%), and Austria (34%) also show significant dependence on renewable energy. Estonia (38%) and Lithuania (30%) perform better than the EU-27 average, showing significant progress in adopting RESs. However, Poland and France remain below the EU average, with renewable energy accounting for only 27% of their gross energy consumption [42,43,44]. Figure 1 provides a visual representation of these trends and illustrates the context of the share of renewable energy in EU countries. This creates a basis for analyzing the use of RESs in various sectors, including healthcare.

Figure 1.

Percentage share of RESs in total electricity production in EU member states.

The adoption of RESs is crucial for improving healthcare outcomes and overall quality of life, especially in regions where fossil fuels dominate the energy mix [45,46]. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA) annual report for 2023, 60.3% of energy production in Poland is based on coal, with RESs accounting for only 27.74%. In Germany and Denmark has the highest share of wind electricity, which together with bioenergy and solar photovoltaic make up over 80% of the electricity mix. In Bulgaria, 66% of the country’s electricity came from sources other than fossil fuels in 2023, and this figure is set to rise due to the continued development of solar energy [47]. In the Czech Republic, coal consumption is declining (PISM Czech Republic in the process of climate and energy transformation) in favor of nuclear energy. Solar farms are also used, accounting for approximately 17% of the Czech energy mix, gas (8%), pumped storage power plants (5%) and hydroelectric power plants (5%). Biomass and wind farms are used to a lesser extent. Energy mixes around the world—Czech Republic—Association “Z energią o prawie” (With Energy About Law).

This dependence on fossil fuels contributes to high carbon dioxide emissions, which are associated with environmental degradation and public health problems, including respiratory and cardiovascular diseases. The transition to a sustainable energy system with greater integration of RESs such as wind, solar, hydro, and biomass is essential not only to reduce the carbon footprint in the countries mentioned, but also to ensure a cleaner environment and more resilient healthcare infrastructure, which will ultimately lead to an improved quality of life.

In many EU countries, the adoption of RESs remains low, and thus the use of renewable sources in healthcare is also low. Total greenhouse gas emissions from the EU-27 member states reached approximately 3222 million tons in 2023. Despite this substantial figure, no detailed data on the carbon footprint of the healthcare sector across the EU is available. Although a few countries have taken steps to measure and monitor greenhouse gas emissions from healthcare (including Germany and Canada), such practices remain the exception rather than the rule [48,49]. The reviewed literature indicates the implementation of RESs in healthcare facilities, highlighting the associated benefits as well as the challenges encountered in their adoption [2,13,18,30,31,50,51,52,53].

Table 1 below shows the potential for using RESs in healthcare facilities, as well as the potential benefits and challenges.

Table 1.

The potential for using RESs, benefits, and challenges in healthcare facilities.

There is a lack of comprehensive pan-European studies estimating the carbon footprint of the healthcare sector. The available data concern a non-EU country—England [54]. The estimated carbon footprint of the healthcare sector can be calculated by assuming a similar percentage in EU countries. Taking a reference level of 5%, it is estimated that the healthcare sector in the EU may be responsible for 161 million tons of greenhouse gas emissions per year. Research shows that in England, the healthcare sector accounts for around 5% of the country’s total greenhouse gas emissions, including emissions from buildings, transport, and the supply chain. Data from the National Health Service (NHS) England also indicates that around 25% of these emissions can be attributed to energy consumption in healthcare buildings.

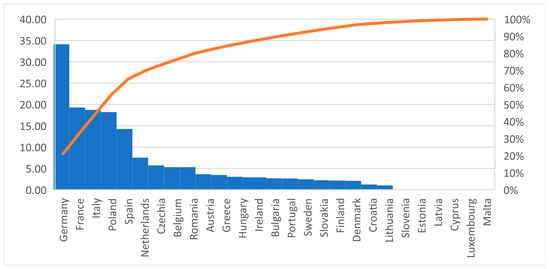

The increasing use of renewable energy in healthcare facilities has significant potential to reduce this carbon footprint and bring countries with a significant share of this footprint closer to the EU’s sustainability goals [44]. See Figure 2, which illustrates a comparative analysis of greenhouse gas emissions in EU countries, highlighting the critical need for greater use of renewable energy in healthcare.

Figure 2.

Greenhouse Gas emissions annually in healthcare settings. Blue bars represent healthcare-related greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions expressed as a percentage of each country’s total GHG emissions. The orange line indicates the cumulative contribution of all EU countries’ healthcare-related GHG emissions.

Figure 2 presents a Pareto analysis of healthcare-related greenhouse gas emissions across EU countries. The graph clearly highlights the potential of Germany, France, Italy, Poland, and Spain to use renewable energy in healthcare facilities to improve environmental sustainability. The chart illustrates greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions attributable to healthcare facilities in EU countries, which account for 5% of total GHG emissions in each country. Greenhouse gas emissions related to healthcare are relatively high. This reflects the significant dependence on fossil fuels in the energy mix, including in the healthcare sector, which contributes to increased emissions. Countries such as the Netherlands, the Czech Republic, Belgium, and Romania have significantly lower emissions. Meanwhile, countries such as Malta, Luxembourg, and Cyprus have negligible emissions, probably due to their smaller healthcare infrastructure and higher rates of renewable energy use.

In countries such as Germany, France, Italy, Poland, and Spain, there is an urgent need to integrate RESs into healthcare facilities in order to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. By increasing the adoption of RESs, as seen in countries such as Sweden and Denmark, which have lower emissions per capita, these countries could achieve a significant reduction in the carbon footprint of the healthcare sector.

The aim of this article is to examine the potential of RESs in solving environmental problems in healthcare in EU countries. The types of RESs, their availability, and the relationship between RES adoption and the following indicators were analyzed: EPI, EHS, and HI.

3. Materials and Methods

This study aims to empirically examine the effect of the independent variables such as RESs, EPI and EHS over dependent variable such as the HI in EU member states, assessing whether improved environmental outcomes represent into measurable gains in HI.

To provide a more comprehensive understanding, each of the key variables used in this study is described in detail below. This explanation clarifies their scope and relevance to the research context.

The dependent variable, the HI, represents an aggregate measure of the overall performance and quality of a healthcare system [55]. It evaluates critical components such as the availability and competence of medical professionals, the adequacy of healthcare infrastructure and equipment, the availability of services, accessibility to physicians, and the cost-effectiveness of care. This index provides a comprehensive assessment of the healthcare infrastructure, services, and resources available within a country.

Among the independent variables, Renewable Energy Resources (RESs) refer to naturally replenishing energy sources, including solar, wind, hydropower, geothermal, and biomass, that can be sustainably utilized for energy production [56]. These resources play a crucial role in reducing reliance on fossil fuels and mitigating greenhouse gas emissions. The second independent variable, the EPI, is a composite indicator designed to evaluate and compare countries’ environmental and ecosystem vitality. It consists of multiple metrics such as air and water quality, biodiversity and habitat protection, climate change mitigation, agriculture, and pollution control [57]. Finally, the EHS measures a country’s efforts to protect its population from environmental health risks. This score is derived from four core issue categories: Air Quality, Sanitation and Drinking Water, Heavy Metals, and Waste Management. Collectively, these dimensions assess the extent to which environmental conditions and regulatory measures reduce health risks associated with pollution, unsafe water, toxic exposures, and improper waste management [58].

The above data were obtained from multiple internationally recognized sources. In particular, the EPI is prepared by the Yale Center for Environmental Law and Policy that gathered its data from reputable third-party organizations, including international institutions, research bodies, and academic groups. These data were collected through diverse methods such as surveys, peer-reviewed academic research, and government statistics used only when they are independently auditable. The compilation of the EPI is carried out in collaboration with the Columbia University Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN), ensuring transparency and a strictly data-driven approach.

The European Environment Agency (EEA) acquires data regarding RESs primarily through Eurostat, which provides official energy statistics reported by EU member countries under regulatory frameworks such as the Renewable Energy Directive. The EEA further integrates information from its internal policies and measures database, as well as international sources including the IEA and IRENA, to produce comprehensive renewable-energy indicators.

Data about HI and EHS were taken from Numbeo, the world’s largest online crowdsourced database, were also utilized. Numbeo’s dataset is based on structured surveys completed by website contributors, where responses are scored on a scale from −2 (strongly negative perception) to +2 (strongly positive perception). To ensure data reliability, Numbeo applies spam-filtering algorithms that eliminate suspicious or low-quality inputs. Resulting scores are then normalized to a 0–100 scale to facilitate interpretation, and the index is updated semi-annually by incorporating the most recent survey contributions into the existing dataset.

The dataset, presented in Table 2, was constructed based on information from the aforementioned sources for the tear 2024 [44,55,59].

Table 2.

Data prepared for statistical analysis, including the independent variables RESs, EPI, EHS and the dependent variable HI, for EU countries in 2024.

To achieve the research objective, a quantitative and correlational design was adopted in the statistical analysis, applying Pearson’s correlation coefficient as the principal analytical technique.

Before specifying and estimating the statistical model, the distributional properties of the variables were examined. Normality was assessed using skewness and kurtosis diagnostics to verify the suitability of parametric correlation analysis. The results indicated that all variables fall within acceptable ranges (from −0.5 to +1.5), confirming the appropriateness of Pearson’s correlation coefficient and ruling out the need for non-parametric alternatives. This procedure ensures statistical validity and reduces the risk of biased inference caused by non-normal distributions.

Following the verification of normality, a correlation matrix was constructed to evaluate the linear associations between EPI and HQI across EU countries. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was selected due to its analyzing relationships between continuous variables measured on ratio scales. A significance level of 0.05 was adopted, consistent with conventional inferential standards in social sciences and public health research. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences), version 29.0.2.0(20), which ensures methodological transparency. Based on the theoretical framework and empirical considerations described above, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1.

Renewable Energy Usage (%) is positively associated with the HI in EU countries.

H2.

EPI is positively associated with the HI in EU countries indicating that better environmental conditions contribute to higher HI.

H3.

EHS is positively associated with the HI in EU countries.

4. Results

The results showed significant positive correlation for both H2 and H3. For H2, a statistically significant relationship was found between the EPI and the HI (r = 0.549, p = 0.003). The bootstrapped 95% confidence interval indicated that the strength of this relationship in the population may range from weak to strong (95% CI: 0.323–0.738). These findings confirm that countries with higher EPI values tend to exhibit higher HI. Similarly, H3 was supported by the data, with a significant positive correlation observed between EHSs and the HI (r = 0.475, p = 0.012). The bootstrapped 95% confidence interval suggested that the strength of this relationship could vary from very weak to strong (95% CI: 0.101–0.767). Thus, countries with higher EHSs also tend to achieve higher levels of HI.

Table 3 presents the results of our statistical analysis of the relationship between EPI and EHS (independent variable) with HI (dependent variable) in EU countries in 2024. Pearson’s correlation coefficients “r” and significance levels were used to assess the strength and direction of these relationships. The results indicate a significant positive correlation between EPI, EHS and HI.

Table 3.

Correlation between EPI, EHS and HI for EU countries in 2024, showing Pearson’s r with significance levels and 95% bootstrap confidence intervals.

However, a multiple linear regression was performed to examine whether the EPI and EHS predicted the HI. Twenty-seven observations were included in the analysis (N = 27). The results of our study shows that the hypotheses H2 and H3 examined the predictive influence of environmental indicators on the HI in EU countries. Table 4, shows a result for H2, the EPI demonstrated a statistically significant effect on HI. The regression model showed that EPI positively predicted HI, with a standardized beta coefficient of 0.425. The model was statistically significant (F = 5.577, p = 0.010), and the Durbin–Watson statistic (2.064) indicated no autocorrelation in the residuals, meeting assumptions for regression analysis.

Table 4.

Regression results of two predictors variables EPI, EHS over outcome variable (HI) for EU countries in 2024.

A similar analysis was conducted for H3, which tested whether the EHS predicts the HI. The standardized beta coefficient for EHS was 0.176, indicating a smaller but positive effect on healthcare performance. To determine the proportion of explained variance, the coefficient of determination was calculated using the equation: The model explained 31.7% of the variance in HI.

R2 = (0.563)2 = 0.317 = 31.7%

This means that approximately 31.7% of the variance in HI across EU countries can be explained by both independent variables EPI and EHS. The remaining 68.3% of variance is likely due to other factors, including financing, workforce capacity, governance, medical technologies, demographic factors, and socioeconomic conditions. Compared with these factors, renewable energy usage represents a relatively small external influence, making its independent effect difficult to detect in cross-national data.

In summary, the analysis emphasizes that EPI and EHS have a statistically significant and meaningful impact over HI in the EU member states, confirming the results of our study that sustainable environmental practices and the efficiency of the healthcare system are closely linked. These results confirm our research hypothesis H2 and H3 that EPI and EHS are directly linked with HI in EU member states. The results indicate significant positive correlations, highlighting the benefits of adopting RESs for both environmental and health indicators.

5. Discussion

The results obtained in this study relate to environmental factors of sustainability affecting the quality of healthcare. An important environmental factor is the use of renewable energy sources. The study shows that the use of RESs in healthcare facilities significantly correlates with the improvement of the quality of healthcare, which is also con-firmed by the literature on the subject. Research by other authors focuses on showing the improvement in the quality of this care as a consequence of increasing the reliability of energy supply. Research by Soto et al. [5] and Olatomiwa et al. [6] show that photovoltaic installations in health centers significantly reduce the number of power outages, which translates into quality of care, stable operation of key medical devices such as diagnostic equipment, drug and vaccine coolers, and patient monitoring systems. Research conducted by Misra and Jaffer [60] shows that the implementation of RESs in healthcare facilities affects not only the technical elements but also the functioning of the entire health service delivery system, especially in the context of staff work and the availability of services at night. RESs strengthen the resilience of infrastructure, enabling facilities to operate even during energy crises. Imasiku [61] came to similar conclusions, stressing that access to electricity is crucial for the provision of quality health services. Similar conclusions were presented by Al-Rawi, O.F. et al. [62].

The literature draws attention to the effects of using RESs, taking into account the healthcare system. Teklemariam et al. [63] and Al-Rawi et al. [62] show that investments in RESs reduce the operating costs of healthcare facilities, which makes it possible to shift savings to improving clinical services, developing infrastructure and shortening patient waiting times.

The results of our study show that countries with higher environmental scores tend to have higher healthcare rates. They are consistent with the results of research by other authors, as the energy transformation of healthcare facilities based on photovoltaic installations and other RES technologies contributes to improving the availability and quality of health services. The obtained dependencies confirm that RESs can be treated as an important factor in improving the quality of care, and not only as a tool for reducing emissions or energy costs.

The literature presents studies that analyze the relationships between many environmental determinants (e.g., air quality, water, urban space, green spaces, environmental resources) and healthcare outcomes. These studies lead to the conclusion that a better environment improves health outcomes [3]. In our study, the impact of the RES factor on improving the quality of healthcare was shown.

6. Conclusions

The results of our study showed that our hypothesis H1, Renewable Energy Usage (%) is positively associated with the HI in EU countries, was not statistically significant (p = 0.107). This indicates that RESs do not correspond to better healthcare system performance. This insignificant result is due to some reasons. For example, the limited availability of data is one of the main reasons because national renewable energy statistics are not comparable with the specific energy sources used within healthcare facilities, that often differ from national averages. It likely to reduce the accuracy of the relationship measured. Last but not least, the potential benefits of RESs for population health and healthcare systems develop slowly and gradually. Environmental improvements associated with RESs such as reduced pollution and climate-related risks occur over long periods, whereas the HI reflects current system conditions. As a result, short-term renewable energy data may not align with longer-term health system outcomes.

Hypotheses H2 and H3 were found to be true, so the study suggests that countries with higher EHSs also tend to achieve higher levels of the healthcare index.

The results of our research clearly indicate the important role that RESs play in shaping both environmental sustainability and healthcare outcomes, including the quality of healthcare in the EU. This research provides evidence that the adoption of RESs is positively correlated with EPI and HI in the EU-27 countries. These results not only highlight the environmental and health benefits of switching to renewable energy but also improve sustainability indicators and healthcare outcomes in EU member states.

A high EPI score, indicating better environmental conditions, is positively correlated with better HI. Cleaner energy sources reduce pollution-related health problems, such as respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, thereby reducing the burden on healthcare systems. In addition, the energy efficiency associated with the use of RESs can reduce operating costs in healthcare facilities, making services more accessible and sustainable.

The increasing demand for RESs in the healthcare sector poses a challenge for EU member states due to a lack of sufficient research in healthcare. As our results indicate, increasing the share of renewable energy in healthcare facilities can significantly improve national EPI, EHS and HI. This is particularly important given the energy-intensive nature of healthcare activities regarding renewable sources which contribute significantly to greenhouse gas emissions. The transition to renewable energy can reduce these emissions while addressing energy security concerns, which are critical for Poland, given its historical dependence on coal and imported natural gas.

The implementation of renewable energy in healthcare infrastructure can also bring measurable economic benefits. By reducing energy costs, healthcare facilities can devote more resources to patient care and healthcare innovation.

The study’s findings provide a strong rationale for implementing targeted policies to accelerate the deployment of renewable energy in healthcare and other sectors. For countries with a high carbon footprint, these recommendations included the following:

- (1)

- Government subsidies, tax incentives, and grants for renewable energy projects in healthcare facilities can encourage wider use of renewable energy. These measures should be complemented by low-interest loans and public–private partnerships to finance the energy transition.

- (2)

- Clear and enforceable policies are needed to integrate renewable energy into healthcare operations. This includes setting renewable energy targets for hospitals, clinics, and other healthcare providers, as well as establishing energy efficiency standards.

- (3)

- Investments in research and development can stimulate innovation in renewable energy technologies, making them more cost-effective and accessible. Joint efforts between academia, industry, and government can accelerate the implementation of renewable energy in healthcare facilities.

- (4)

- Training programs for healthcare workers and facility managers can raise awareness of the benefits of renewable energy and equip them with the skills needed to implement energy-efficient practices. Awareness campaigns can also build support for renewable energy initiatives.

The positive correlation between RES adoption and environmental and healthcare outcomes underscores the need for a coordinated approach to sustainability. By sharing best practices and consistent policies, EU member states can collectively achieve their climate and healthcare goals.

While this study provides valuable insights, it is not without limitations. The lack of comprehensive data on healthcare-related greenhouse gas emissions across the EU poses a challenge to fully understanding the sector’s carbon footprint. Future research should prioritize the collection of detailed and consistent data to enable more precise analyses.

Furthermore, although the correlation analysis establishes a link between the adoption of RESs, EPI, EHS and HI, it does not prove causality. Further research is needed to explore the mechanisms through which renewable energy influences environmental and health outcomes. Longitudinal studies and case studies of specific countries or healthcare facilities could provide deeper insight into these dynamics.

Finally, the study’s focus on the EU-27 countries limits its applicability to other regions. Extending the analysis to non-EU countries with high shares of renewable energy, such as Norway and Iceland, could provide a more complete understanding of the global potential of RESs in healthcare.

Our future research will focus on demonstrating the impact of the remaining factors that influence the quality of healthcare. In our study, we examined two environmental factors: the EPI and the EHS. From the perspective of sustainable development, the quality of healthcare is influenced not only by environmental factors but also by social and economic determinants.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.V., A.K. and S.Ș.M.; methodology, V.V., A.K. and F.L.; software, F.L. and S.Ș.M.; validation, F.L. and S.Ș.M.; formal analysis, A.K. and F.L.; investigation, V.V., A.K., F.L. and S.Ș.M.; resources, A.K. and F.L.; data curation, V.V., A.K., F.L. and S.Ș.M.; writing—original draft preparation, V.V., A.K., F.L. and S.Ș.M.; writing—review and editing, A.K. and F.L.; visualization, F.L. and S.Ș.M.; supervision, A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The article was developed as part of a research internship at the ‘1 December 1918’ University of Alba Iulia in Romania.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dincer, I. Renewable energy and sustainable development: A crucial review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2000, 4, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzeo, D.; Baglivo, C.; Panico, S.; Manieri, M.; Matera, N.; Congedo, P.M. Eco-Sustainable Energy Production in Healthcare: Trends and Challenges in Renewable Energy Systems. Energies 2023, 16, 7285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, M.; Madureira, J.; Mendes, A.; Torres, A. Environmental determinants of population health in urban settings: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, L.; Wilman, E.N.; Laurance, W.F. How Green is “Green Energy”? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2017, 32, 922–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, E.A.; Hernandez-Guzman, A.; Vizcarrondo-Ortega, A.; McNealey, A.; Bosman, L.B. Solar Energy Implementation for Health-Care Facilities in Developing and Underdeveloped Countries: Overview, Opportunities, and Challenges. Energies 2022, 15, 8602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olatomiwa, L.; Sadiq, A.A.; Longe, O.M.; Ambafi, J.G.; Jack, K.E.; Abd’azeez, T.A.; Adeniyi, S. An Overview of Energy Access Solutions for Rural Healthcare Facilities. Energies 2022, 15, 9554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Quality of Care. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/quality-of-care#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Aparicio-Martínez, P.; Martínez-Jiménez, M.P.; Perea-Moreno, A.-J. Health Environment and Sustainable Development. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanello, M.; Napoli, C.D.; Green, C.; Kennard, H.; Lampard, P.; Scamman, D.; Walawender, M.; Ali, Z.; Ameli, N.; Ayeb-Karlsson, S.; et al. The 2023 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: The imperative for a health-centred response in a world facing irreversible harms. Lancet 2023, 402, 2346–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ani, V.A. Powering primary healthcare centers with clean energy sources. Renew. Energy Environ. Sustain. 2021, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corvalan, C.; Villalobos Prats, E.; Sena, A.; Campbell-Lendrum, D.; Karliner, J.; Risso, A.; Wilburn, S.; Slotterback, S.; Rathi, M.; Stringer, R.; et al. Towards Climate Resilient and Environmentally Sustainable Health Care Facilities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirtas, O. Evaluating the Best Renewable Energy Technology for Sustainable Energy Planning. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2013, 3, 23–33. Available online: https://www.econjournals.com/index.php/ijeep/article/view/571 (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Koijen, R.S.J.; Philipson, T.J.; Uhlig, H. Financial Health Economics. Econometrica 2016, 84, 195–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, M.; Alcamo, G.; Nelli, L.C. Energy-Saving Solutions for Five Hospitals in Europe. In Mediterranean Green Buildings & Renewable Energy; Sayigh, A., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammadov, N.S.; Ganiyeva, N.A.; Aliyeva, G.A. Role of Renewable Energy Sources in the World. J. Renew. Energy Electr. Comput. Eng. 2022, 2, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldorai, A. A Survey of Renewable Energy Sources and Their Contribution to Sustainable Development. J. Enterp. Bus. Intell. 2022, 2, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Renewable Power Generation Costs in 2024—Executive Summary. Available online: https://www.irena.org/publications (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- McKee, M. Global sustainable healthcare. Medicine 2018, 46, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dion, H.; Evans, M.; Farrell, P. Hospitals Management Transformative Initiatives: Towards Energy Efficiency and Environmental Sustainability in Healthcare Facilities. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2023, 21, 552–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psillaki, M.; Apostolopoulos, N.; Makris, I.; Liargovas, P.; Apostolopoulos, S.; Dimitrakopoulos, P.; Sklias, G. Hospitals’ Energy Efficiency in the Perspective of Saving Resources and Providing Quality Services through Technological Options: A Systematic Literature Review. Energies 2023, 16, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldovan, F.; Blaga, P.; Moldovan, L.; Bataga, T. An Innovative Framework for Sustainable Development in Healthcare: The Human Rights Assessment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.C.; Fuinhas, J.A.; Pereira, D.A. Have Fossil Fuels Been Substituted by Renewables? An Empirical Assessment for 10 European Countries. Energy Policy 2018, 116, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, F.; Felgueiras, C.; Smitková, M. Fossil Fuel Energy Consumption in European Countries. Energy Procedia 2018, 153, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, F.; Felgueiras, C.; Smitková, M.; Caetano, N. Analysis of Fossil Fuel Energy Consumption and Environmental Impacts in European Countries. Energies 2019, 12, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipiak, B.Z.; Wyszkowska, D. Determinants of Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions in European Union Countries. Energies 2022, 15, 9561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gołasa, P.; Wysokiński, M.; Bieńkowska-Gołasa, W.; Gradziuk, P.; Golonko, M.; Gradziuk, B.; Siedlecka, A.; Gromada, A. Sources of Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Agriculture, with Particular Emphasis on Emissions from Energy Used. Energies 2021, 14, 3784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtaszek, H.; Miciuła, I.; Modrzejewska, D.; Stecyk, A.; Sikora, M.; Wójcik-Czerniawska, A.; Smolarek, M.; Kowalczyk, A.; Chojnacka, M. Energy Policy until 2050—Comparative Analysis between Poland and Germany. Energies 2024, 17, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sanz-Calcedo, J.; Al-Kassir, A.; Yusaf, T. Economic and Environmental Impact of Energy Saving in Healthcare Buildings. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaiby, R.; Krenyácz, É. Energy efficiency in healthcare institutions. Soc. Econ. 2023, 45, 494–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, C.A.; Wever, R.; Teoh, C.; De Clercq, S. Designing cradle-to-cradle products: A reality check. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2010, 3, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominiak, N.; Oleszczyk, N. The use of renewable energy sources in Poland against a European Union background. Ann. Pol. Assoc. Agric. Aribus. Econ. 2019, XXI, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Marks-Bielska, R.; Bielski, S.; Pik, K.; Kurowska, K. The Importance of Renewable Energy Sources in Poland’s Energy Mix. Energies 2020, 13, 4624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senay, E.; Landrigan, P.J. Assessment of Environmental Sustainability and Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting by Large Health Care Organizations. JAMA Netw. Open 2018, 1, e180975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dion, H.; Evans, M. Strategic Frameworks for Sustainability and Corporate Governance in Healthcare Facilities: Approaches to Energy-Efficient Hospital Management. Benchmarking Int. J. 2024, 31, 353–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pous De La Flor, J.; Castañeda, M.C.; Pous Cabello, J. Energy Storage Developing Circular Economy in Existing Facilities for Renewable Energy Use. In Circular Economy on Energy and Natural Resources Industries; Mora, P., Acien Fernandez, F.G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janik-Karpińska, E.; Brancaleoni, R.; Niemcewicz, M.; Wojtas, W.; Foco, M.; Podogrocki, M.; Bijak, M. Healthcare Waste—A Serious Problem for Global Health. Healthcare 2023, 11, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, M.L.U.; Iqbal, A.; Chang, C.; Li, W.; Ju, M. Anaerobic digestion. Water Environ. Res. 2019, 91, 1253–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obileke, K.; Nwokolo, N.; Makaka, G.; Mukumba, P.; Onyeaka, H. Anaerobic digestion: Technology for biogas production as a source of renewable energy—A review. Energy Environ. 2021, 32, 191–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, C.; Priyadarshini, A. Review of current healthcare waste management methods and their effect on global health. Healthcare 2021, 9, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chías, P.; Abad, T. Green hospitals, green healthcare. Int. J. Energy Prod. Manag. 2017, 2, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.; Lu, W.; Liu, B.; Hassanein, Z.; Mahmood, H.; Khalid, S. Exploring the role of fossil fuels and renewable energy in determining environmental sustainability: Evidence from OECD countries. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Database. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Central Statistical Office in Warsaw. Statistical Yearbook of Warsaw 2023. Available online: https://warszawa.stat.gov.pl/publikacje-i-foldery/roczniki-statystyczne/rocznik-statystyczny-warszawy-2023,6,20.html (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- European Environment Agency. World Energy Outlook 2023—Analysis. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2023 (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Khosla, R.; Miranda, N.D.; Trotter, P.A.; Mazzone, A.; Renaldi, R.; McElroy, C.; Cohen, F.; Jani, A.; Perera-Salazar, R.; McCulloch, M. Cooling for sustainable development. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 4, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggerio, C.A. Sustainability and sustainable development: A review of principles and definitions. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 786, 147481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Energy in Bulgaria, Between Past and Future. Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso. Available online: https://www.balcanicaucaso.org/eng/Areas/Bulgaria/Energy-in-Bulgaria-between-past-and-future-233520 (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Quitmann, C.; Terres, L.; Maun, A.; Sauerborn, R.; Reynolds, E.; Bärnighausen, T.; Franke, B. Assessing greenhouse gas emissions in hospitals: The development of an open-access calculator and its application to a German case-study. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2025, 16, 100262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowlan, J.; Miller, F.A. Estimating greenhouse gas emissions from the health sector in Canada: Mind the gap. Healthc. Manag. Forum 2025, 38, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kara, S.; Hauschild, M.; Sutherland, J.; McAloone, T. Closed-loop systems to circular economy: A pathway to environmental sustainability? CIRP Ann. 2022, 71, 505–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukuła, K. Dynamics of Producing Renewable Energy in Poland and EU-28 Countries within the Period of 2004–2012. Folia Oecon. Stetin. 2015, 15, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rashid, S.; Malik, S.H. Transition from a Linear to a Circular Economy. In Renewable Energy in Circular Economy; Bandh, S.A., Malla, F.A., Hoang, A.T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tee, N.C.H.; Yeo, J.-A.; Choolani, M.; Poh, K.K.; Ang, T.L. Healthcare in the era of climate change and the need for environmental sustainability. Singap. Med. J. 2024, 65, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS England. Five Years of a Greener NHS: Progress and Forward Look. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/five-years-of-a-greener-nhs-progress-and-forward-look (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Numbeo: Health Care. Available online: https://www.numbeo.com/health-care (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- European Environment Agency. EEA Datahub—Environmental Data Portal. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/datahub/datahubitem-view/1fd08152-1371-4274-8091-b50467738376 (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Block, S.; Emerson, J.W.; Esty, D.C.; de Sherbinin, A.; Wendling, Z.A. 2024 Environmental Performance Index; Yale Center for Environmental Law & Policy: New Haven, CT, USA, 2024; pp. 1–300. Available online: https://epi.yale.edu (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Yale Center for Environmental Law & Policy. Environmental Performance Index—Environmental Health (HLT). Available online: https://epi.yale.edu/measure/2024/HLT (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Yale Center for Environmental Law and Policy (YCELP). Available online: https://envirocenter.yale.edu/ (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Misra, R.; Jaffer, H. Solar Powering Public Health Centers: A Systems Thinking Lens. Sol. Compass 2023, 7, 100052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imasiku, K. Comprehensive approaches to electrifying rural health facilities: Integrating renewable energy and financial mechanisms in Sub-Saharan Africa. Energy Strateg. Rev. 2025, 59, 101736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rawi, O.F.; Bicer, Y.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G. Sustainable solutions for healthcare facilities: Examining the viability of solar energy systems. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 11, 1220293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teklemariam, S.K.; Schiasselloni, R.; Cattani, L.; Bozzoli, F. Solar Energy Solutions for Healthcare in Rural Areas of Developing Countries: Technologies, Challenges, and Opportunities. Energies 2025, 18, 3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).