Abstract

Leadership, organizational culture, and their effects on employee attitudes are key focuses in organizational behavior studies. In this research, there were two main aims: first, to explore how organizational trust influences the relationship between leadership styles and organizational culture, and second, to clarify the mediating role of organizational culture in the link between leadership styles and affective occupational commitment among academics in Istanbul, Türkiye. Participants were selected from various states and private universities using convenience sampling. A cross-sectional survey involving quantitative methods were used to examine the relationships between key variables. The data was collected from 352 respondents. Effective leaders build trust and adapt organizational culture, which fosters employee commitment to their roles. Despite the relevant theoretical framework, there is a strong and positive link between trust in organization, leadership, and organizational culture, so the hypothesized moderating role of trust in organization was rejected. In contrast, the findings confirm the mediating role of organizational culture in the connection between leadership styles and affective occupational commitment. Moreover, another significant research finding was that leadership styles are effective when an organization has a supportive and innovative culture. Most academics expressed dissatisfaction with the effectiveness of leadership and their work environment, indicating challenges in promoting a positive culture. This study clarifies the dimensions of leadership styles, organizational trust, culture, and emotional commitment, thereby contributing to the literature concerning these areas.

1. Introduction

Leadership, organizational culture, and their connections to employee attitudes are prominent topics in the field of organizational behavior. Although numerous research studies have been conducted, the findings often vary due to differences in study design and the characteristics of the sampling frames. These variations can be attributed to the cultural and educational backgrounds of respondents [1,2,3,4,5], as well as the socioeconomic characteristics of the countries where the studies were conducted.

Since the mediating role of organizational culture on organizational commitment is a subject of debate, especially for small and large organizations, this link is worth re-examining by focusing on academics in universities. As Schein (1992) emphasized, the development of organizational culture dynamics depends upon new, unique leadership behavior, which helps organizations survive despite new challenging social, cultural, and environmental conditions [6].

Commitment theory remains popular among researchers today, and organizational change management (OCM) refers to how an individual psychologically identifies with their organization. Some newer theoretical approaches to OCM have been taken, such as Levinger’s cohesiveness theory (as noted by [7] Agnew, 2009) and Dunger’s (2023) three-dimensional concept of the OCM scale, which includes identification, involvement, and loyalty as key components [1]. However, most researchers have favored the three-component theory that Meyer and colleagues developed in 1993.

Past research by Abdullah et al. (2015) indicated that the mediating role of organizational culture between leadership practices and OCM was not empirically observed when the sample consisted of small businesses [8]. However, other studies, such as those by Shim et al. (2015) and Lee (2022), confirm the mediating effect of organizational culture on OCM [9,10]. Despite these mixed empirical findings, in the present study the uncertainty regarding the mediating role of organizational culture between leadership styles and organizational culture change is addressed, particularly in the context of university structures and objectives, which fundamentally differ from those of small or large businesses.

The success of effective leaders often depends on their ability to build trust and direct their followers to focus on achieving organizational goals by changing the dynamics of organizational culture and making employees have a strong commitment to performing their job tasks properly. While the previous studies generally focused on students’ perceptions on organizational culture, leadership styles and performance, the present study is directly related to the perceptions of academics on the aforementioned concepts. In this context leadership styles are of importance to understand better the role of department heads, deans and the members of rectorate.

There were two main objectives in the present study. The first was to examine how organizational trust affects the relationship between leadership styles and organizational culture. The second was to explain the mediating mechanism of organizational culture in the association between leadership styles and affective occupational commitment among university lecturers. A research question was also formulated to identify differences in the perceptions of the key concepts by gender and the status of lecturers.

Generally speaking, Turkey is a collectivist country, and the most frequently observed leadership style is benevolent leadership. An issue that should be emphasized is that the organizational culture of private universities has not been firmly established because of the founders’ demands and interference in the management of faculties, even in the assessment of curricula. For state universities, the same problem exists in terms of the extent to which the influence of the Institution for Higher Education affects the selection of academics as well as the functioning of faculties.

2. Conceptual Background

2.1. Leadership

It has become customary or even obligatory when defining leadership to start by emphasizing its complexity due to its multifaceted nature. A detailed examination of the relevant literature revealed the most important facets of the concept of leadership, such as its importance in fostering change, articulating vision, and directing a group of people sharing similar values and beliefs.

Leadership can be regarded as a deliberate and intentional process that focuses on guiding individuals or groups toward achieving specific goals. This process is inherently rooted in values that shape the leader’s actions and decisions. Leadership involves steering a collective effort while remaining aligned with core values, prioritizing the well-being and growth of the team members and the organization [11,12].

According to Yukl (2013), there are two opposing approaches to understanding today’s leadership processes: the so-called specialized role and shared influence [13]. The first assumes that a leader has a specialized role, while the latter implies an influential function in any social unit by enriching social relations among followers. The second approach is quite obviously beneficial for universities. This collaborative approach empowers diverse voices and enhances the group’s overall effectiveness. The crucial point concerns the lecturers’ level of motivation and ethical attitudes for the sake of the high level of performance of their universities as well as constructive social interactions between them.

Today, many universities in the United States and a number of other countries exhibit a hierarchical and often authoritarian leadership style, particularly within academic faculties. In this environment, leaders tend to have high professional status and adopt an individualistic approach, often disregarding the recommendations of boards of directors and committees [12].

Ogbonna and Harris (2000, p. 766) [4] emphasize that the existing literature on leadership highlights a crucial point, i.e., to be an effective leader, one must possess the ability to comprehend and navigate the intricacies of the cultural environment in which one operates. This understanding is not merely beneficial but rather an essential requirement for achieving leadership success.

When it comes to universities, it is important to emphasize that, regardless of the various leadership theories, an effective leader can influence their followers to improve the quality of education. Avolio et al. (2009) conducted a comprehensive analysis of the evolution of leadership theories that emerged during the latter part of the twentieth century and continued to develop into the early twenty-first century [14]. These theories can be broadly categorized into three traditional frameworks: trait, behavioral, and situational/contingency theories. Additionally, Likert’s four-type leadership model offers further insights by defining effective and ineffective leadership behaviors. This model classifies leadership styles into four distinct categories: exploitative–authoritative, benevolent–authoritative, consultative, and participative leadership.

What stands out during this evolution is the increasing recognition that contemporary leadership practices must differ fundamentally from these traditional approaches. The rigid structures and assumptions underpinning older leadership theories are often ill-equipped to address the complexities of modern organizations, which operate within highly dynamic and interconnected environments in today’s globalized world [15]. At present, the needs of followers shaped by factors such as digitalization and globalization require leaders to adopt more flexible and adaptive strategies. Researchers such as Eberly et al. (2013), Eddy (2006), and Turner and Baker (2018) underscore the importance of evolving leadership models that are responsive to the challenges posed by today’s social systems, ultimately highlighting the necessity for a shift towards more innovative and collaborative leadership paradigms [11,15,16].

They categorized these developments as newer leadership theories, including charismatic leadership, inspirational leadership, transformational leadership, and full-spectrum leadership theory. In addition to this foundational work, Eddy et al. (2006) contributed further by introducing cultural, symbolic, and cognitive leadership theories into the discourse on effective leadership [11].

The cultural and symbolic leadership theories emphasize the complex interactions and relationships between leaders and their followers. These theories assert that effective leadership is not just about authority or control; it involves understanding and navigating the cultural contexts and shared symbols that influence group dynamics and follower engagement. Leaders who grasp these cultural nuances can foster a more cohesive and motivated team.

Conversely, cognitive leadership theory provides a different perspective by focusing on the strategic decision-making processes and trade-offs that leaders must navigate to achieve personal and organizational goals. This theory highlights the importance of cognitive skills in leadership, such as problem-solving, critical thinking, and the ability to synthesize information to drive organizational outcomes. By considering how leaders think and make decisions, cognitive leadership theory offers insights into the mechanisms that underpin effective leadership in complex organizational environments.

In this context, Bass and Avolio (1995) developed the Multifactor Leadership Theory (MLT), which encompasses a wide range of ineffective and effective leadership behaviors [17]. The breadth of the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) makes it more suitable for administration at all organizational levels and across different economic sectors [18]. Similarly, Meuser et al. (2016) highlight several important leadership styles based on a comprehensive literature review conducted over the previous two decades [19]. These styles include charismatic leadership, transformational leadership, strategic leadership, leadership and diversity, and participative/shared leadership. Contemporary views on leadership can be summarized as follows:

The charismatic leadership theory posits that leaders possess a vision, understand their followers’ needs, and are willing to take risks in their actions. Transformational leaders exhibit core characteristics such as individualized consideration, inspirational motivation, idealized influence, and intellectual stimulation. In contrast, transactional leaders focus on directing their followers to achieve pre-established goals by clearly defining roles and task requirements.

Authentic leadership, rooted in positive psychology, is defined by several essential traits. These traits encompass the ability to foster self-awareness in both leaders and their team members, the cultivation of a supportive organizational culture and climate, and the capacity to impact employees’ attitudes toward their work positively. Such leadership practices are crucial in creating a healthier workplace environment, enhancing employee engagement, and increasing overall job satisfaction [20]. Authentic leaders are recognized for making transparent decisions and consistently aligning their words with their actions. On the other hand, visionary leaders can create a compelling vision for a group and guide their followers by effectively leveraging their influence.

Current perspectives on leadership can be summarized as follows: Charismatic Leadership: This theory asserts that leaders have a vision for their followers’ needs while also being willing to take risks. Transformational Leadership: Such leaders are characterized by individualized consideration, inspirational motivation, idealized influence, and intellectual stimulation. Transactional Leadership: In contrast to transformational leaders, transactional leaders direct their followers toward achieving predefined goals by clearly outlining roles and task expectations. Authentic leaders are known for their transparent decision-making processes that align their actions with their words consistently. In contrast, visionary leaders excel at crafting compelling visions for groups while effectively guiding their followers through influential means.

In the current study, the relationship between leadership style and organizational culture is explored. Following the approach of other researchers such as Dayan (2021), Tütüncü and Akgündüz (2012), Bakan (2009), Huang (2011), and Pedraja-Rejas (2006), the authors have chosen the same leadership scale [21,22,23,24,25]. As stated by Barik (2024, p. 12142), “It (academic leadership) includes developing a dynamic intellectual community, encouraging creativity, and developing the abilities of teachers, staff, and students.” [26]. The leadership scale of Ogbonna and Harris was developed to understand the behaviors of leaders in higher education and how they guide, support, and involve academics and students.

2.2. Organizational Trust

The essence of organizational trust lies in the fair play of members within any social system. Trust is also a multidimensional concept and researchers have explained it differently. Trust is briefly employees’ perception of leaders and superiors during the course of organizational functioning; the crucial issue is here whether the said perception is positive and strong enough regarding the creation of a trust climate. In terms of social exchange theory organizational trust plays a vital role in ensuring that employees experience peace, success, and productivity within their workplace. When employees have confidence in their organization, it enhances their dedication to their roles and contributes positively to the overall success of the organization. Studies indicate that organizational trust has a substantial effect on employees’ likelihood of leaving, their job satisfaction levels, and their commitment to the organization. Additionally, earlier research indicates that employees who have faith in their managers and organizations tend to be more diligent in fulfilling their responsibilities.

Theoretically, there are two main types of trust: cognitive and affective. Cognitive trust is about the willingness of two parties toward each other and is related to reciprocal behavior; affective organizational or occupational trust is, in a word, emotional and implies the existence of fairness and honesty [27]. The level of trust in an organization of an individual varies according to leadership styles and organizational functioning by emphasizing the strong link between affective commitment and trust [28]. Aryee et al. (2002) found that trust in the organization serves as a partial mediator in the connections among distributive and procedural justice, as well as job satisfaction, turnover intentions, and organizational commitment [29].

The dimensions of the concept of trust, which differ among academics, are competence, benevolence, leader integrity or confidence, trust and reliance or integrity, competence, consistency, loyalty, and openness [29,30,31]. However, the organizational trust inventory that we used was developed by Nyhan and Marlowe and has two dimensions, namely trust in the supervisor and trust in the organization. Paliszkiewicz, following Young-Ybarra, states that trust has three components: dependability, predictability, and faith [32]. Employees typically maintain a positive and constructive attitude toward the intentions and actions of others, even under the condition of vulnerability. Organizations should challenge uncertainties in today’s globalized atmosphere and build more potent, warm, and effective employee relations. The results of many empirical studies on organizational trust indicate that whenever the level of organizational trust is high, the employees’ organizational commitment and performance are also high [31,32,33,34].

Suppose those in leadership positions and high-status managers in universities or organizations establish an effective communication network with the individuals they work with and create an environment of trust via a supportive approach. In that case, employees’ loyalty and faith in management will increase. In this respect, social exchange theory is one of the most influential conceptual frameworks for understanding organizational behavior and the employee–organization relationship. It is obvious that trust is an important issue in organizations, and it may play a crucial role in a university setting in terms of the quality of relationships and communication networks. Trust is generally investigated under two headings: trust in the leader and trust in the organization. In the present study, the focus is on assessing lecturers’ and professors’ perceptions of their superiors and the members of the university rectorate.

Regardless of the type of organization, leaders’ negative behaviors, as well as the quality and frequency of communication practices, can harm employees [30,35,36]. Especially in higher education institutions, faculty members who are all experienced in their fields and have high self-confidence expect the planning, implementation, and promises made by the department heads, deans, and provosts to whom they are affiliated to be kept, so if this situation fails to be realized the climate of trust will be damaged.

It is also worth using the operationalization of this concept as an emergent state. As expressed by Burke et al. (2007, p. 609) “Emergent states refer to cognitive, motivational, or affective states that are dynamic and vary as a function of contextual factors as well as inputs, processes, and outcomes” [37]. Moreover, past research findings show that affective commitment has a strong and positive effect on some important organizational outputs such as absenteeism turnover intention.

2.3. Organizational Culture

Organizational culture is a collection of shared values, goals, and practices that define the essence of a nation, a society, or an individual organization. Much like the concept of leadership, organizational culture is complex and multifaceted. It captures the attention of researchers and practitioners alike due to its critical role in the effectiveness and functionality of various social systems, regardless of the organization’s nature.

Kilmann, Saxton, and Serpa (1985, p. ix) provided a significant academic perspective on this intricate concept by stating: “Culture means the same formation for an organization as personality means for a person” [38]. This analogy underscores the idea that just as personality shapes an individual’s identity and behavior, culture similarly influences an organization’s collective identity and practices. The shared assumptions and values held by members of any social system form the foundation of that organization’s culture. These assumptions, values, and beliefs influence the perceptions and thoughts of the members of social systems and shape their attitudes and behaviors, contributing to the unique cultural fabric of each organization.

As Schein (1992) reminds us, the founders of organizations play a crucial role [6]. This is because, during the initial establishment, while determining the basic goals and strategies of the business, a business in the growth stages, the founders’ values will reflect their beliefs on deciding organizational strategies. In essence, organizational culture acts as the foundational thread that connects the beliefs and actions of its members, guiding interactions and decisions within the workplace. Some of the key figures in the culture literature are Ghaleb (2024), Wallach (1983), Mansaray and Atan (2025), Hofstede (1991), Schein (1992), and Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner (1998) [6,39,40,41,42,43].

The recent article by Tadesse Bogale (2024), a detailed review of organizational culture, is very valuable [44]. Indeed, organizational culture is the subject of the hypothetical associations between organization culture theory and organizational outcomes such as organizational performance and effectiveness, leadership, employee satisfaction, organizational commitment, organizational change, innovation, artificial intelligence, sustainability, and digitalization. Additionally, empirical evidence supports the connection between organizational culture and several management subdomains highlighted above. In the current study, the focus is also on the links between organizational culture, leadership, and affective commitment in university settings. Universities differ sharply from organizations operating in the market, regardless of whether for-profit or non-profit. It is worth emphasizing again the effect of organizational culture on key organizational outcomes such as innovation, job satisfaction, and commitment [45]. Mansaray and Atan (2025) emphasizes that organizational culture is an essential issue to help employees’ efforts in showing how a company responds to societal demands and nurtures internal motivation [41]. A constructive and adaptive culture not only bolsters organizational resilience but also acts as a lasting source of competitive advantage, contributing significantly to long-term success.

What is important for a university is the coverage of its culture, which concerns members of faculties, administrators, and students, all of whom make university culture highly dynamic and flexible depending on the level of interaction. Almost the same idea was advocated by Diocos and Rosol (2023), who state (p. 44) that the organizational culture of a university implies “a very special case since it is based on the fact that an educational unit is a self-organized system resting on the principles of knowledge and learning” [46]. The assessment of university culture is also problematic, depending on whether the organizational culture is strong or weak, the methods of decision-making in faculties and their departments, and the level and quality of communication between lecturers and administrators [47].

It is essential to understand that every organizational culture serves as a solid foundation and can be primarily categorized as mechanistic, organic, or a combination of both. The classification depends on the organizational objectives and the social systems in place. According to Yahyagil (2015, p. 522), “existing organizational culture models are categorized under two headings: ‘qualitative/descriptive’ and ‘cognitive’ to understand the basic cultural traits of organizations” [48]. From a cognitive perspective, it is essential to recognize that organizational culture revolves around the shared cognitive frameworks of its members. These frameworks influence how individuals perceive the cultural environment in which they operate, guiding their understanding of values, beliefs, and meanings associated with organizational culture. This, in turn, shapes their actions and behaviors [49,50]. Similarly, research conducted in academic institutions indicates that this culture serves as a defining characteristic that sets one organization apart from others. Consequently, organizations that foster well-trained, motivated, and empowered teams are more likely to meet their goals, as these teams cultivate proactive behaviors and develop positive synergies [51].

Today, there are several organizational culture models, each with its own advantages and disadvantages influenced by the structure of the organizations, the subdimensions of culture, and the specific fields in which the organizations operate. Some of the most commonly used models of organizational culture include those developed by Mansaray and Atan (2025), Ghaleb (2024), Wallach (1983), Hofstede (1998), and Ogbonna and Harris (2000) [4,39,40,41,52]. Any given cultural leadership theory can be effective if it accurately reflects the organization’s core values, beliefs, and meanings and aligns with its mission and vision. Consequently, researchers and academics have utilized different models based on the objectives of their studies and the characteristics of the organizations involved.

The relationship between leadership and organizational culture deserves exploration, especially regarding their interconnections concerning different organizational types, structures, and leadership styles. However, this relationship differs significantly in the context of higher education. In a university setting, the expressions of leadership may often be limited to correcting administrative issues rather than fostering improved communication among faculty, introducing innovative educational strategies, or building effective relationships with deans and members of the university rectorate. The effectiveness of these changes largely depends on the willingness of those with the highest status to discuss proposed improvements. This matter is also a part of the current study, with the aim of illuminating this and similar academic discussions according to the empirical results obtained.

3. Affective Occupational Commitment

Organizational commitment, also known as occupational or career commitment, is a frequently investigated subject in organizational behavior studies. Although different researchers have made many attempts to define this concept, Allen and Meyer’s (1990) definition [53], which examines commitment in three conceptual dimensions, namely normative, continuance, and affective, is still preferred by many academics [1,54]. While continuance commitment concerns an employee’s need to remain in his/her organization, normative commitment implies a necessity for an employee; affective commitment is directly related to an employee’s desire or preference to stay where he/she works. It is known that the higher the level of affective commitment will, the higher the level of certain organizational outcomes such as job satisfaction, job performance, and organizational citizenship behavior [30,55]. It should be taken into account that affective commitment should not be thought of as a psychological effect, but rather as a strategic advantage that helps develop emotional engagement in employees and create human dignity and collective well-being [56].

Since affective commitment is positively linked to the betterment of emotional attachment, personal identification, and a physiological tie between employees and the organization, if the efforts of organizational leaders and/or superiors are successful in creating fairness and a trust climate in their social settings, organizational functions are likely to improve within a certain period. Morales-Huamán (2023) rightly states that empirical research conducted in universities shows that organizational culture is an evolving process, requiring academics to create positive synergies and enhance elements of leadership and commitment to the organization [56].

What also has to be emphasized is related to the level of person–organization fit, which is a breaking point [57]. Whenever person–organization fit is high among the employees of any social unit, within the framework of the field of organizational behavior, the relationship between the individual value judgments of business employees and the value system (organizational culture) within the business they work for is defined as person–organization fit [58].

If such a fit occurs in any given organization, the employees will be more willing to do their best in line with the organizational goals. As Wasti and Can (2008, p. 404) point out, “the influence of culture on commitment foci-outcomes relationships” has not been explored [59]. The authors hope to establish facts regarding this subject in the current study.

The Links Between Key Concepts and Hypothesis Development

It is understood from the results of numerous studies in the literature that as long as the mutual exchange in social systems of materialistic and value-based abstract formations is positive in terms of social change theory, the behavior of leaders in every organization positively affects the general performance and organizational functioning of other individuals, and this reflects positively on the organizational culture as well as the emergence of trust climate [6,10,30,60,61]. It is interesting and generally neglected that leadership might be a predictor of organizational culture, and it is this culture that virtually determines how leaders behave. However, the common point that is shared and accepted by all researchers and scholars is the existence of a strong reciprocal association between leadership and organizational culture.

Although leaders in universities, generally speaking, are professors chosen by the university rectorate and/or university senate, it is likely for them to play some kind of traditional leadership role that is somewhat authoritarian and aims at maintaining the existing culture. Furthermore, the faculty leaders who are performing their tasks are not agents of change and aim to maintain a friendly atmosphere without trying to make a radical change. Yet, the role of leadership is connected to organizational culture, and 377 there is a mutual link concerning the achievement of organizational goals by clarifying professional tasks through an effective communication network [4,12,60]. When leaders can share the purpose of their social units, which is important, especially for universities’ faculties and departments, they can successfully establish a collaboration necessary for effective teamwork [12]. This has been taking new forms depending on the quality of interactions among staff members [46].

Such a link between the concepts of leadership and organizational culture might affect certain organizational outcomes such as job satisfaction, performance, and employee well-being, even though the culture of universities is flexible and highly dynamic. As Paliszkiewicz et al. (2014, p. 33) emphasize, “Indeed, it has been observed that employees’ trust in supervisors is associated with their trust in the organization” [32]. Although research studies have focused on different subjects, there is empirical evidence that clearly shows that trust has a moderating role between leadership and organizational culture [60,62,63].

Consequently, as long as the high-status members of universities support professors and lecturers who are working in different faculties and departments to understand and to accept the core cultural values of organizations, creating a sense of fairness and an autonomous atmosphere, leaders will be more effective for the betterment of the quality of education, which might influence students’ identification with their universities and their level of performance. It must be underlined that strong beliefs of employees regarding cultural values imply the strength of affective commitment as well as the willingness of employees to be involved in job-related activities [1].

While the positive relationship between organizational culture and OCM deserves attention as discussed above, scholars and researchers have also confirmed that the findings of their empirical investigations indicate there is a positive relationship between organizational culture and commitment, and that employees’ performance enhancement and commitment have been affected positively by organizational culture [35,64,65]. It has also been recognized that the strength of the organizational culture increases the organizational commitment to the high level of employees’ task performance and their desire to remain where they work. In other words, their perception of OCM depends on strong organizational culture and certain types of leadership, such as servant leaders. Undoubtedly, affective commitment, to which I indirectly attributed values of organizational vision and shared beliefs, inevitably strengthened the emotional ties among the members of the organization to develop socially meaningful behaviors.

4. Methodology

4.1. Sampling Procedure

The study’s respondents were selected from three state and four private universities through convenience sampling. We asked the HR departments of the universities to provide us with email accounts of their lecturers, and we also tried to find their email accounts through the websites of these universities. An online structural questionnaire was developed; then we sent a Google Form repeatedly to instructors working in different universities. The number of usable questionnaires was 352. Although, this result indicates a response rate of 88% which is, indeed, an impressive figure.

4.2. Research Design

A cross-sectional survey was conducted using the quantitative method, employing a correlational (hypothesis testing) design to investigate the associations between key research variables.

4.3. Research Model

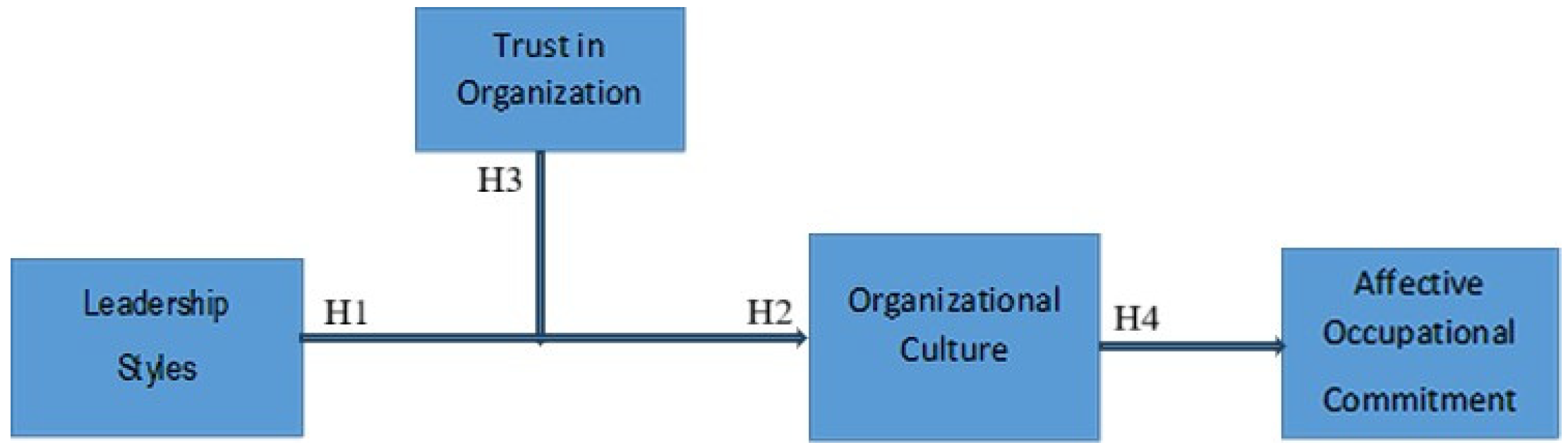

The research model is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research Model.

4.4. Measurement Tools

All four survey instruments used in this research consisted of well-known 5-point Likert-type scales.

- Organizational Trust Inventory: Developed by Nyhan and Marlowe (1997) [28] and called the Organizational Trust Scale by Demircan and Ceylan (2003) [66], who adapted it into Turkish. The scale consists of two subdimensions: trust in the supervisor (eight items) and trust in the organization (4 items).

- Wallach’s (1983) organizational Culture Index consists of 24 items to measure organizational culture’s three conceptual dimensions (bureaucratic, innovative, and supportive) [40]. The Turkish adaptation of the scale was performed by Yahyagil (2004) [67].

- Meyer and colleagues (1993) and then Wasti (1999) developed the affective organizational commitment scale, which includes 5 items [36,68].

- The leadership style scale was developed by Harris and Ogbonna (2001) [69]. It includes 13 items. This instrument assesses leaders’ supportive, participative, and instrumental behaviors. A Turkish adaptation of this tool was published by Bakan (2009) [23].

4.5. Research Hypotheses

In light of the findings of an extensive literature review, it is possible to reach three conclusions, namely the positive link between leadership and organizational culture, organizational trust, and OCM, and the following research question and hypotheses are formulated:

RQ1: Are there differences in the perceptions of key concepts by gender and status of lecturers?

H1.

A strong relationship exists between leadership, organizational culture, and affective commitment.

H2.

Leadership explains the innovative and supportive subdimensions of organizational culture, but not bureaucratic culture.

H3.

Organizational trust moderates the association between leadership and organizational culture.

H4.

Organizational culture mediates the link between leadership and affective occupational commitment.

4.6. Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS v26. Firstly, the reverse items of the measurement instruments were corrected. Secondly, the reliability analyses were performed. Following the descriptive analyses, factor analyses, Herman’s Single-Factor test, and regression analyses were employed. Additional statistical tests were also used.

5. Results

5.1. Participants

The participants involved in the present study were instructors at different state and private universities. A total of 352 respondents, of whom 216 were female instructors and 136 were male instructors, were working in different universities. The mean age of the instructors was 36, and the mean tenure was 16 years. While 13% of the participants were in the 21–25 age group, 23% were in the 26–30 age group, and 32% were over 40 years of age. The distribution of the titles of the instructors is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The titles of the participants.

5.2. Validity and Reliability Level of the Scales

The reliability coefficients of the four scales used in the present study were highly satisfactory, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Reliability analyses of the scales.

All of the key concepts indicate that the perceptions of instructors are somewhat at a moderate level. The skewness and kurtosis values of the key variables of the study are within acceptable limits as well (statistical range: +1.5 and 1.5) [70]; this indicates that the distribution of the research data is normal (Table 3). Since all of the measurement tools are 5-point Likert scales, the actual mean values of each key concept are also calculated as follows: leadership style: 3.20 (participative: 3.14; supportive: 3.04; instrumental: 3.42); organizational trust: 2.96; organizational culture: 3.16 (bureaucratic culture: 3.82, supportive culture: 2.89; innovative culture: 3.11), and affective organizational commitment: 3.11.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics.

5.3. Factor Analyses

Factor analyses were conducted for each of the four key concepts in the study. While the first (leadership styles) scale (KMO value: marvelous) yielded two factors (Table 4), the second (org.culture) also resulted (KMO value: meritorious) in two factors. As expected, the third (TrstinOrg/KMO: 0.793) and fourth (Affectivecomt/KMO: 0.831) scales resulted in single factors. The KMO and Bartlett’s test values of all measurement scales were highly satisfactory.

Table 4.

Factor analysis of leadership styles.

While the KMO value is marvelous the factor loadings for each component exceed the threshold for participative and supportive leadership styles but there is a noticeable absence of instrumental leadership (Table 5). Instrumental leaders are strategically astute individuals who monitor the external environment, set strategies and goals, provide direction and resources, oversee performance, and offer constructive feedback. In other words, instrumental leadership is associated with strategic leadership, the implementation of strategies, and the provision of support to followers in their roles. This gap presents significant challenges for university leaders, particularly due to the bureaucratic structures prevalent in Turkish academia due to there is almost no chance for a dean or department head to suggest educational reforms.

Table 5.

Factor analysis of organizational culture.

Although the factor analysis yielded three components, one of the components has only one item with a moderate loading. Therefore, there are two factors; the first combines innovative and supportive culture, while the second represents bureaucratic culture. It is worth noting that the mean value of bureaucratic culture (3.82) is higher than that of innovative and supportive culture.

Moreover, Herman’s single-factor test was employed to determine whether a set of items can be grouped under a single factor. This technique is often used to assess the validity of a scale and to understand common method variance (Table 6). Since the result of the test indicated that the total variance was 45.49% and did not exceed 50%, common method bias is not present in the present study.

Table 6.

Herman’s single-factor test.

5.4. Correlational Analyses

Pearson’s correlation analysis was performed to determine the direction and strength of four key research concepts, and the results indicated a strong and positive relationship between them. All of the correlation values were statistically significant. Additionally, the correlation values between participative leadership, supportive leadership, instrumental leadership, and organizational culture were 0.500, 0.494, and 0.475, respectively, all of which were statistically significant (see Table 7).

Table 7.

Correlation analysis of key research variables.

5.5. Hypothesis Testing

- To test the first hypothesis (a strong relationship exists between leadership, organizational culture, and affective commitment), Pearson’s correlation test was used, and the result clearly showed a positive, strong, and statistically meaningful relationship between the two concepts (see Table 7). Thus, the first hypothesis was accepted.

- The second hypothesis (leadership explains the innovative and supportive subdimensions of organizational culture, but not bureaucratic culture) was tested using regression analysis, and it was found that leadership styles were explained by the supportive and innovative subdimensions of organizational culture. It is also clear that the impact of the innovative subculture dimension is very weak. As shown in Table 8 and Table 9, the impact of supportive culture is very high (0.652), and the relevant t-test value is 10.751; the effect of innovative culture is also weak (0.164), the relevant t-test value is 2.867, and all of the values are highly significant.

Table 8. Model summary of the regression analysis of organizational culture.

Table 8. Model summary of the regression analysis of organizational culture. Table 9. Coefficients.

Table 9. Coefficients. - Regression analysis was used to test the third research hypothesis (organizational trust moderates the association between leadership and organizational culture), and despite the correlation value of the relationship between leadership styles and trust in the organization, the result indicated that there was no moderation. It is widely recognized that an increase in academics’ perceptions of organizational culture correlates with a rise in organizational trust. However, it is important to consider that the mean trust value in the current study is below the midpoint. Therefore, this finding suggests that respondents do not possess trust in their organization. This result is also contrary to the relevant theoretical framework, but is the case for the present study. Thus, the third hypothesis was rejected.

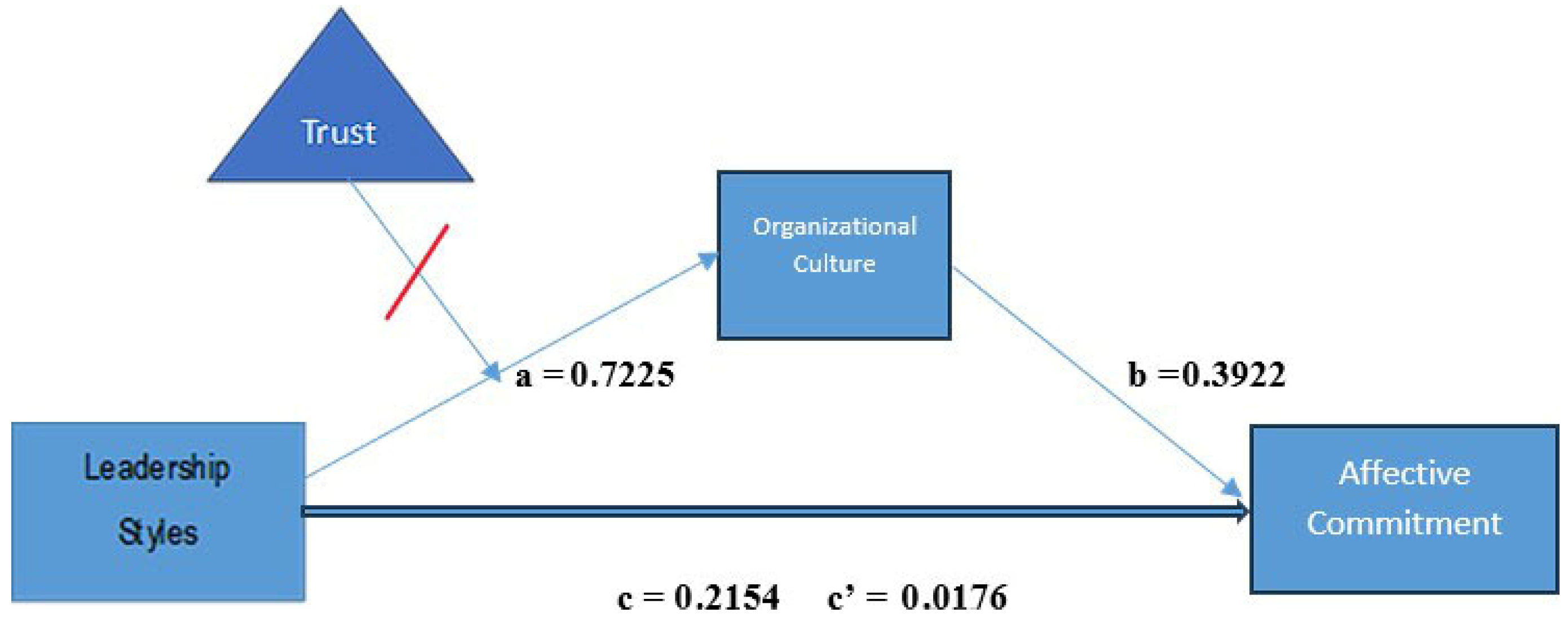

- The last hypothesis of the study (organizational culture mediates the link between leadership and affective occupational commitment) was tested using Hayes’ PROCESS macro, and the result showed that organizational culture partially and complementarily mediated the relationship between leadership styles and affective commitment. The output of the Hayes procedure is presented in Table 10. Consequently, the fourth hypothesis was accepted.

Table 10. The output of Hayes’ procedure.

Table 10. The output of Hayes’ procedure.

The details of Hayes’ macro procedure are presented in Table 10; the mediating role of organizational culture in the relationship between leadership styles and affective commitment was examined in the study. The direct effect of leadership styles on affective commitment, in the presence of the mediator, is also significant (b = 0.392, p < 0.001). Since both total (0.2154) and direct effects (0.1038) are significant, organizational culture partially and complementarily mediates the link between leadership styles and affective commitment.

5.6. Research Question

RQ 1. Are there differences in the perceptions of key concepts by the gender and academic titles of lecturers?

The research question regarding instructors’ perceptions of key research concepts by gender and academic rank was examined using independent t-tests (Table 11). The findings revealed that male instructors exhibited a greater appreciation for the four key research concepts (leadership styles, organizational trust, organizational culture, and affective occupational commitment) compared to their female counterparts, with this difference having high statistical significance. However, a second independent t-test showed that perceptions among the instructors did not vary significantly based on their academic titles (Table 12).

Table 11.

Independent t-test of academics’ perceptions.

Table 12.

Independent t-test results.

6. Discussion

Regarding the objectives of the present study (Figure 2), its findings demonstrate the usefulness of applying implicit measures in organizational settings. The main purpose of the study was to shed light on the mediating role of organizational culture between leadership styles and affective occupational commitment, which is confirmed as a result of the statistical analyses. Contrary to expectations, the organizational culture only partially mediated the sensitive tie between leadership behaviors and affective commitment; the mean values of all three key concepts are actually just a bit higher than the threshold value.

Figure 2.

The revised research model.

The systematic review revealed a detailed overview of the research framework, with Alvesson (2011) stating that the ‘culture-driven’ nature of leadership is neglected in most of the literature, even though organizational culture and leadership have long been considered crucial elements for performance and efficiency achievement [71]. Since it has been emphasized that there is also a strong and positive link between trust in organization, leadership, and organizational culture, the hypothesized moderating role of trust in organization was rejected. For these primary findings, it is necessary to examine the results of reliability tests and descriptive and correlational explanations, as well as the factor analyses, since all of the statistical values considering the aforementioned key concepts are very high, statistically significant, and meaningful.

The third significant finding reveals that leadership styles are effective when a supportive and innovative organizational culture exists, a sentiment shared by university academics, regardless of whether they work at state or private institutions. The findings of the present study demonstrate that bureaucratic culture, with a mean value of 3.82, is the prevailing subculture. Similarly, leadership scored a mean of 3.2, while the mean values for other primary concepts, such as organizational trust (2.96) and affective organizational commitment (3.11), are all comparable. Research results can indicate that the orientation towards bureaucratic culture (hierarchy) is characterized by a lower impact and, despite that, there is a very high correlation value of 0.72 (see Table 7) between leadership styles and organizational culture; the direct effect of leadership on culture is only 22% (see Table 10). The same is also true for the link between leadership, trust in organization, and organizational culture. These results are all in conformity in the present study, and this also explains that factor analysis for leadership styles resulted in two approaches that are supportive and participative.

7. Conclusions

These results indicate that nearly all academics express dissatisfaction with both the effectiveness of leadership and the workplace environment at their institutions. Furthermore, the universities examined in the present research may face challenges in cultivating a positive and innovative culture. The low level of organizational trust is a crucial issue for Turkish academia, which is related to the bureaucratic structure of universities in Turkey. Most probably, this is related to the lack of the moderating effect of organizational trust between leadership styles and organizational culture, regarding their level of motivation, which may not be helpful for the betterment of the quality of academic performance.

It also appears that the leadership approaches employed by department heads and deans may be constrained by a lack of personal autonomy and robust professional connections, with potential influences from the rectorate limiting their capacity for independent action.

After examining the outcomes of all factor analyses, it can be concluded that the results are consistent with the relevant theoretical frameworks. However, the empirical findings reveal a certain level of dissatisfaction among academics concerning organizational operations. This dissatisfaction helps to explain why nearly all academics, irrespective of their rank, express unhappiness with the management practices at their universities, whether public or private institutions.

Additionally, an intriguing finding relates to the perceptions of four key research concepts among male academics, who appear to demonstrate greater sensitivity than their female colleagues. Furthermore, the participants in the present study showed no significant differences in terms of their academic titles, suggesting a shared consensus among instructors regarding both the effectiveness of leadership styles and the overall dissatisfaction with organizational performance.

To conclude, in the present study, the aspects and scope of leadership styles, organizational trust, culture, and emotional commitment are outlined and clarified, and the significant differences among these concepts are highlighted, thereby contributing to the current body of knowledge.

8. Limitations

The present study acknowledges several limitations. The primary limitation was related to the sampling frame, which ideally should have included at least one of the largest state universities and one of the largest private universities. A significant obstacle in this study was the reluctance of academics to participate in the survey. Had the questionnaire been accompanied by a cover letter encouraging academics to complete and return them to the rectorate, it may have facilitated the collection of more comprehensive data. In such a scenario, a stratified sampling method could have been employed to enhance data collection. Additionally, future research could benefit from a qualitative approach, selecting two academics from each academic status at both state and private universities.

8.1. Implications

In light of the findings of this paper, higher education institutions should pay attention to the recommendations made by heads of departments and deans of faculties and should discuss their decisions related to the curriculum, establishment of new courses, and selection of academics by giving them more personal freedom and autonomy. Members of the rectorate and the provost of universities should intervene in the decisions and applications of academics if the proposals are not in line with the vision and general principles of their universities. Finally, the creation of an innovative organizational culture must be considered a crucial issue for operational efficiency. It is essential for higher education institutions to prioritize the alignment of leadership styles and the social interactions of academics with HR policies and the rectorate of universities.

8.2. Future Research

It would be helpful if academics were selected for research by a simple random method, some of whom are working at state universities and others at private universities. A comparison would be more useful for the sake of gaining a better understanding of the situation if two more universities from another big city are included in the sampling frame. Another suggestion might well be the use of an interpretivist paradigm that also might be appropriate for an in-depth exploration of how academics expect the nature of the working atmosphere in universities to be, and also how they perceive managerial mechanism.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.A. and Y.Ç.K.; methodology, B.A.; software, Y.Ç.K.; validation, Y.Ç.K.; formal analysis, B.A.; investigation, B.A. and Y.Ç.K.; writing—original draft preparation, B.A. and Y.Ç.K.; writing—review and editing, B.A. and Y.Ç.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Ethical Charter of Trakya University (03/12) on 5 March 2025, and with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dunger, S. Culture Meets Commitment: How Organizational Culture Influences Affective Commitment. Int. J. Organ. Theory Behav. 2023, 26, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar, A.Z. Organizational Culture, Leadership Styles and Organizational Commitment in Turkish Logistics Industry. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 58, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makri, M.; Scandura, T.A. Exploring the Effects of Creative CEO Leadership on Innovation in High-Technology Firms. Leadersh. Q. 2010, 21, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbonna, E.; Harris, L.C. Leadership Style, Organizational Culture and Performance: Empirical Evidence from UK Companies. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2000, 11, 766–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javidan, M.; Dorfman, P.W.; De Luque, M.S.; House, R.J. In the Eye of the Beholder: Cross Cultural Lessons in Leadership from Project GLOBE. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2006, 20, 67–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, E.H. Organizational Culture and Leadership, 2nd ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Agnew, C. Commitment, Theories and Typologies; Purdue University: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, N.H.; Shamsuddin, A.; Wahab, E. Does Organizational Culture Mediate the Relationship between Transformational Leadership and Organizational Commitment? Int. J. Organ. Leadersh. 2015, 4, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, H.S.; Jo, Y.; Hoover, L.T. Police Transformational Leadership and Organizational Commitment: Mediating Role of Organizational Culture. Polic. Int. J. Police Strateg. Manag. 2015, 38, 754–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.N. The Mediating Influence of Organizational Culture on Leadership Style and Organizational Commitment. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2022, 12, 414–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy, P.L.; VanDerLinden, K.E. Emerging Definitions of Leadership in Higher Education: New Visions of Leadership or Same Old “Hero” Leader? Community Coll. Rev. 2006, 34, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astin, A.W.; Astin, H.S.; Allen, K.E.; Burkhardt, J.; Cress, C.M.; Flores, R.A.; Jones, P.; Lucas, N.; Pribush, B.L.; Reckmeyer, W.C. Leadership Reconsidered: Engaging Higher Education in Social Change; W.K. Kellogg Foundation: Battle Creek, MI, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Yukl, G. Leadership in Organizations, 8th ed.; Pearson Education India: Delhi, India, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Avolio, B.J.; Reichard, R.J.; Hannah, S.T.; Walumbwa, F.O.; Chan, A. A Meta-Analytic Review of Leadership Impact Research: Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Studies. Leadersh. Q. 2009, 20, 764–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.R.; Baker, R. A Review of Leadership Theories: Identifying a Lack of Growth in the HRD Leadership Domain. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2018, 42, 470–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberly, M.B.; Johnson, M.D.; Hernandez, M.; Avolio, B.J. An Integrative Process Model of Leadership: Examining Loci, Mechanisms, and Event Cycles. Am. Psychol. 2013, 68, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J. MLQ: Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire; Mind Garden: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M. Improving Organizational Effectiveness Through Transformational Leadership; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Meuser, J.D.; Gardner, W.L.; Dinh, J.E.; Hu, J.; Liden, R.C.; Lord, R.G. A Network Analysis of Leadership Theory: The Infancy of Integration. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 1374–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayça, B. Association between Authentic Leadership and Job Performance—The Moderating Roles of Trust in the Supervisor and Trust in the Organization: The Example of Türkiye. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayan, H.; Dayanç Kıyat, G.B. Liderlik ve Inovasyon Arasındaki Ilis¸kide Rekabet Avantajının Rolü Üzerine Bir Aras¸tırma. Int. Soc. Sci. Stud. J. 2021, 7, 2352–2361. [Google Scholar]

- Tütüncü, Ö.; Akgündüz, Y. Seyahat Acentelerinde Örgüt Kültürü ve Liderlik Arasındaki Ilis¸ki: Kus¸adası Bölgesinde Bir Aras¸tırma. Anatolia Tur. Aras¸Tırmaları Derg. 2012, 23, 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Bakan, İ. Liderlik Tarzları ile Örgüt Kültürü Türleri Arasındaki İlişkiler: Bir Alan Çalışması. Tisk. Acad./Tisk. Akad. 2009, 4, 138. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, T.M. The Relationship between Headmasters’ Leadership Behaviour and Teachers Commitment in Primary Schools in the District of Sarikei, Sarawak. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 29, 1725–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pedraja-Rejas, L.; Rodríguez-Ponce, E.; Rodríguez-Ponce, J. Leadership Styles and Effectiveness: A Study of Small Firms in Chile. Interciencia 2006, 31, 500–504. [Google Scholar]

- Barik, P.B.B.; Barik, V.; Khamkat, P.; Mahanti, K. Academic Leadership in Higher Education. Educ. Adm. Theory Pract. 2024, 30, 12142–12143. [Google Scholar]

- Pucetaite, R.; Novelskaite, A.; Markunaite, L. The Mediating Role of Leadership Relationship in Building Organisational Trust on Ethical Culture of an Organisation. Econ. Sociol. 2015, 8, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nyhan, R.C.; Marlowe, H.A., Jr. Development and Psychometric Properties of the Organizational Trust Inventory. Eval. Rev. 1997, 21, 614–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryee, S.; Budhwar, P.S.; Chen, Z.X. Trust as a Mediator of the Relationship between Organizational Justice and Work Outcomes: Test of a Social Exchange Model. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2002, 23, 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, R. Organizational Trust and Leadership. Int. Conf. Knowl. BASED Organ. 2021, 27, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alston, F.; Tippett, D. Does a Technology-Driven Organization’s Culture Influence the Trust Employees Have in Their Managers? Eng. Manag. J. 2009, 21, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliszkiewicz, J.; Koohang, A.; Gołuchowski, J.; Horn Nord, J. Management Trust, Organizational Trust, and Organizational. Performance: Advancing and Measuring a Theoretical Model. Manag. Prod. Eng. Rev. 2014, 5, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, K. The Relationship between Organizational Trust and Organizational Commitment in Turkish Primary Schools. J. Appl. Sci. 2008, 8, 2293–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asunakutlu, T. Güven, Kültür ve Örgütsel Yansımaları. In Kültürel Bağlamda Yönetsel-Örgütsel Davranış (ss. 231-265); Türk Psikologlar Derneği Yayınları: Ankara, Türkiye, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, E.E.; Winston, B.E. A Correlation of Servant Leadership, Leader Trust, and Organizational Trust. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2005, 26, 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J.; Smith, C.A. Commitment to Organizations and Occupations: Extension and Test of a Three-Component Conceptualization. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, C.S.; Sims, D.E.; Lazzara, E.H.; Salas, E. Trust in Leadership: A Multi-Level Review and Integration. Leadersh. Q. 2007, 18, 606–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilmann, R.H.; Saxton, M.J.; Serpa, R. Gaining Control of the Corporate Culture; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaleb, B.D.S.; Dahiam, B. The Importance of Organizational Culture for Business Success. J. Ris. Multidisiplin Dan Inov. Teknol. 2024, 2, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallach, E.J. Individuals and Organizations: The Cultural Match. Train. Dev. J. 1983, 37, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Mansaray, I.; Atan, T. Exploring Corporate Social Responsibility: The Role of Transformational Leadership, Innovative Work Behavior, and Organizational Culture in Public Universities of Sierra Leone. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind; McGraw-Hill: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Trompenaars, F.; Hampden-Turner, C. Riding the Waves of Culture: Understanding Diversity in Global Business; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bogale, A.T.; Debela, K.L. Organizational Culture: A Systematic Review. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2340129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xenikou, A. The Cognitive and Affective Components of Organisational Identification: The Role of Perceived Support Values and Charismatic Leadership. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 63, 567–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diocos, C.B.; Resol, V.P. Organizational Culture and Management Practices of a State College in the Philippines. Int. J. Educ. Res. Rev. (IJERE) 2023, 8, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beytekin, O.F.; Dogan, M.; Beytekin, O. The Organizational Culture at the University. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2010, 2010, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Yahyagil, M.Y. Constructing a Typology of Culture in Organizational Behavior. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2015, 23, 506–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlmann, K.; Schreder, G.; Nagl, M.; Zenk, L. Socio-Cognitive Systems of Organizational Culture and Communication. An Investigation into Implicit Cognitive Processes. Athens J. Mass Media Commun. 2017, 3, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, C.M.; Kilbourne, L.M.; Woodman, R.W. A Shared Schema Approach to Understanding Organizational Culture Change. In Research in Organizational Change and Development; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2003; pp. 225–256. [Google Scholar]

- Santiago-Torner, C.; Jiménez-Pérez, Y.; Tarrats-Pons, E. Interaction Between Ethical Leadership, Affective Commitment and Social Sustainability in Transition Economies: A Model Mediated by Ethical Climate and Moderated by Psychological Empowerment in the Colombian Electricity Sector. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Attitudes, Values and Organizational Culture: Disentangling the Concepts. Organ. Stud. 1998, 19, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, N.J.; Meyer, J.P. The Measurement and Antecedents of Affective, Continuance and Normative Commitment to the Organization. J. Occup. Psychol. 1990, 63, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Herscovitch, L. Commitment in the Workplace: Toward a General Model. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2001, 11, 299–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurk, D.; Hofer, A.; Burmeister, A.; Muehlhausen, J.; Volmer, J. Occupational Commitment from a Life Span Perspective: An Integrative Review and a Research Outlook. Career Dev. Int. 2019, 24, 190–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Huamán, H.I.; Medina-Valderrama, C.J.; Valencia-Arias, A.; Vasquez-Coronado, M.H.; Valencia, J.; Delgado-Caramutti, J. Organizational Culture and Teamwork: A Bibliometric Perspective on Public and Private Organizations. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouraoui, K.; Bensemmane, S.; Ohana, M. Corporate Social Responsibility and Employees’ Affective Commitment: A Moderated Mediation Study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahyagil, M.Y. Birey ve Organizasyon Uyumu ve Çalis¸anlarin Is¸ Tutumlarina Etkisi. Öneri Derg. 2005, 6, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasti, S.A.; Can, Ö. Affective and Normative Commitment to Organization, Supervisor, and Coworkers: Do Collectivist Values Matter? J. Vocat. Behav. 2008, 73, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, E.; Ashraf, M.S.; Iqbal, A.; Shabbir, M.S. Leadership and Employee Behaviour: The Mediating and Moderating Role of Cognitive Trust and Organizational Culture. J. Islam. Account. Bus. Res. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J. Transformational Leadership and Organizational Culture. Public Adm. Q. 1993, 17, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petek, H.; Yeşiltaş, M.D. The Effect of Leadership Styles on Organizational Culture: A Research in the Public Sector. Gazi İktisat Ve İşletme Derg. 2024, 10, 460–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargas, A.D.; Varoutas, D. On the Relation between Organizational Culture and Leadership: An Empirical Analysis. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2015, 2, 1055953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lok, P.; Crawford, J. The Effect of Organisational Culture and Leadership Style on Job Satisfaction and Organisational Commit-ment: A Cross-national Comparison. J. Manag. Dev. 2004, 23, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarhan, N.; Harb, A.; Shrafat, F.; Alhusban, M. The Effect of Organizational Culture on the Organizational Commitment: Evidence from Hotel Industry. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2019, 10, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demircan, N.; Ceylan, A. Örgütsel güven kavramı: Nedenleri ve sonuçları. Yönetim Ve Ekon. Derg. 2003, 10, 139–150. [Google Scholar]

- Yahyagil, M.Y. The Interdependence between the Concepts of Organizational Culture and Organizational Climate: An Empirical Investigation. J. Bus. Adm. 2004, 33, 69–98. [Google Scholar]

- Wasti, S.A. Organizational Commitment in Collectivist Culture: The Case of Turkey. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, Champaign, IL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, L.C.; Ogbonna, E. Leadership Style and Market Orientation: An Empirical Study. Eur. J. Mark. 2001, 35, 744–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics. Always Learning; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Alvesson, M. Leadership and Organizational Culture. In The SAGE Handbook of Leadership; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011; pp. 151–164. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).