Abstract

Increasing precipitation variability has been tightly coupled to livestock grazing through direct impacts on vegetation productivity in rangeland ecosystems. However, where and to what extent such impacts occur has not been quantified systematically at the regional scale; thus, adaptive grazing management is plagued by this knowledge gap. Hence, using 20 years of precipitation, rangeland productivity, and livestock density data across Tibet, we assessed long-term precipitation variability impacts on alpine rangeland grazing, specifically highlighting variations in intra- and inter-annual precipitation variability. We showed that the precipitation concentration index (PCI) and coefficient of variation in precipitation (CVP) both increased significantly across Tibet over the past two decades, especially in the western region. On the contrary, grazing intensity (GI) in most rangeland areas markedly declined over the same period. Moreover, we found that GI is highly responsive to PCI and CVP for the alpine steppe, but interestingly, only PCI is significantly associated with GI for the alpine meadow. Furthermore, the Granger causality test indicates an extremely significant causality between GI and PCI, further highlighting that PCI was a remarkable determinant of rangeland grazing over the last two decades. Notably, we statistically identified rangelands with higher precipitation variability that experienced intensive livestock grazing, specifically, GI responded positively to CVP and PCI. In conclusion, our findings provide novel support for the increasing precipitation variability impacts on rangeland grazing over time across Tibet, especially the intra-annual variation. Thus, we advocate the implementation of adaptive grazing management, such as excluding and minimizing grazing for the alpine rangeland ecosystem under higher precipitation variability.

1. Introduction

A large proportion of rangeland ecosystems have converged toward intensified livestock production driven by the growing global population, rising demands for livestock products, and the pursuit of improving food nutrition [1,2,3,4]. However, this intensification is associated with accelerating climate changes, especially high fluctuations in precipitation that primarily control rangeland productivity [5,6,7]. The frequency and intensity of precipitation have the potential to cause changes in biomass, composition, and diversity of plant communities, thus indirectly influencing rangeland grazing [8,9,10]. Moreover, precipitation variability will likely continue under future global warming [11,12,13]. As understanding of rangeland grazing reacts to precipitation variability improves, it becomes necessary to reassess such impacts to enable identifying intensive rangelands to support optimal grazing schemes at the regional scale. Therefore, exploring the effect of precipitation variability on rangeland grazing may further guide the implementation of grazing management when facing a changing climate.

Rangeland ecosystems are known to be highly sensitive to variable precipitation, both within and across years. Previous studies have shown that precipitation regimes act as a crucial driver of rangeland grazing by directly affecting vegetation productivity [14,15,16]. Nonetheless, considering variability adds greater nuance to the anticipated response of precipitation to rangeland productivity; the resulting effects on rangeland productivity are heterogeneous across a variety of timescales and characteristics, consequently affecting their carrying capacity, which refers to the maximum sustainable stocking rate of grazing livestock. Furthermore, this was recognized in recent studies that increasing precipitation variability has been more common [11,17,18], highlighting more variable rangeland productivity under a higher precipitation variability. Thus, optimizing livestock grazing under the fluctuation of rangeland productivity is important to mitigate the loss of climate change. Nevertheless, rangeland research has been dominated by studies of precipitation change rather than precipitation variability. This knowledge gap is a key challenge for managing livestock production under increasing precipitation variability.

Theoretically, non-equilibrium concepts in rangeland ecology stress that rangeland dynamics are affected by precipitation, including frequency and intensity [19,20]. Furthermore, rangelands at the non-equilibrium paradigm advocate that livestock management needs to consider temporal variability and spatial heterogeneity of precipitation, especially in arid and semi-arid environments [21,22]. The suitability for intensified livestock grazing may need to be assessed locally within different regions under a changing precipitation regime. Moreover, future precipitations are likely to include greater variability; predictions of rangeland grazing to precipitation will have to account for the magnitude of variability. For this reason, adaptive grazing management that accounts for precipitation variability is essential for maintaining the productivity and livestock production of rangeland environments. However, compared with precipitation change impacts on rangeland productivity, relatively little is known about the impact of such precipitation variability on rangeland grazing and the adaptation responses available to livestock management.

Long-term monitoring studies emphasize the responses of net primary productivity (NPP) to the annual total amount or mean annual precipitation [15,23]. Nevertheless, recent evidence suggests that enhanced precipitation variability significantly impacts rangeland productivity and grazing compared with precipitation amount [24,25,26]. Zeng et al. [27] revealed that the adaptability of vegetation productivity to precipitation variability determines its resistance to environmental changes in arid and semiarid grassland ecosystems. Compared with trends in mean and extreme precipitation, precipitation variability has experienced a more widespread increase with greater magnitudes across China [28]. Although precipitation variability is projected to increase, the effects of precipitation variability remain less explored than the well-demonstrated changes in the mean state of precipitation. Generally, variability in precipitation characterizes changes in metrics at inter-annual and intra-annual scales; the precipitation concentration index (PCI) and coefficient of variation in precipitation (CVP) were mostly employed to indicate precipitation variations within and between years [18,29,30]. Consequently, using these indicators to quantify the impacts of precipitation variability on rangeland grazing can help decide when, where, and how to optimize livestock grazing management.

The Tibetan Plateau is widely recognized as Asia’s water tower and serves a critical role in regional and global hydroclimate. Rangelands are distributed throughout the Tibetan Plateau and largely dedicated to livestock production. Livestock grazing is the dominant land use in rangelands and can interact with climate to impact the alpine rangeland ecosystem. As reported by empirical analyses, precipitation regimes have undergone dramatic changes over the Tibetan Plateau [31,32], particularly favorable warm-wet climate conditions have dominated rangeland productivity increase over the last decades [33]. Furthermore, the variation in precipitation over the Tibetan Plateau has exhibited distinct regional and seasonal differences in the last two decades, in particular, the precipitation variability and its spatial heterogeneity across different regions of the plateau [31,34,35]. Geographically, Tibet is situated in the southwest of the Tibetan Plateau, with an average altitude of above 4000 m and dramatic geography. Tibet’s unique tectonic geomorphology shapes regional precipitation gradients and variations. But precipitation variability has still received less attention; little feedback information can provide for grazing management in the face of long-term precipitation variability. Most existing knowledge concerning rangeland productivity to precipitation change is based on aboveground net primary productivity (ANPP) and precipitation data. For instance, it has been intensively reported that coordinated variation between inter-annual changes in precipitation and rangeland productivity [36,37,38]. Nevertheless, these studies have not fully considered the impacts of precipitation variability on rangeland grazing. It is still less acknowledged where and to what extent precipitation variability is on rangeland grazing. More importantly, with growing observational evidence pointing to increased occurrences of variable precipitation over the past decades across the Tibetan Plateau, it is necessary to examine whether an increase in precipitation variability has already emerged and, if so, the potential effects on rangeland grazing. Understanding these impacts is crucial for alpine rangeland grazing and ensuring the sustainability of livestock production in the face of increasing precipitation variability.

Here, we conducted a quantitative assessment of the potential for rangeland intensification in the face of long-term trends in precipitation variability in Tibet. We hypothesized that the higher precipitation variability could significantly impact rangeland grazing, especially in intensive grazing and arid rangelands. To achieve this, we intend to (1) assess the spatial and temporal heterogeneity of precipitation variability, particularly focusing on CVP and PCI, (2) analyze the change trend and relationship of precipitation variability and grazing intensity, and (3) identify intensive grazing rangelands that have undergone significant precipitation variability. As a result, this study will help identify intensified grazing areas in precipitation variability to facilitate adaptive grazing management under a future variable climate.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

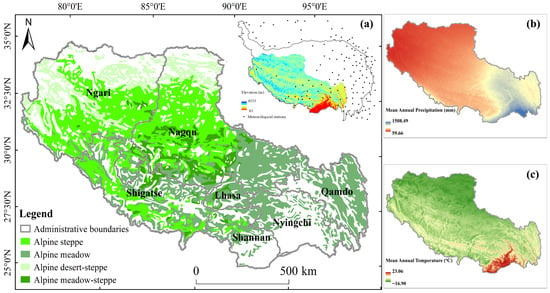

This study focused on the rangeland ecosystem in the Tibet Autonomous Region (hereinafter Tibet), China (26°50′–36°53′ N, 78°25′–99°06′ E; Figure 1). Administratively, this region is composed of Lhasa Municipality, Shannan Prefecture, Shigatse Prefecture, Nyingchi Prefecture, Qamdo Prefecture, Nagqu Prefecture, and Ngari Prefecture. The topography of the area has an average of 4000 m above sea level. Most of the region is characterized by an alpine climate, including an annual average temperature range of −16 to 23 °C, and a mean annual precipitation range of 59–1508 mm. Rangelands are the dominant ecosystem and basic resource for livestock production in this area, typically including alpine meadow, meadow-steppe, steppe, and desert-steppe. The typical functional types of plant communities are legumes, grasses, sedges, and forbs, such as Kobresia pygmaea and Carex moorcroftii in alpine meadow, Stipa purpurea and Stipa capillacea in alpine steppe, and Stipa subsessiliflora and Ceratoides lateens in alpine desert-steppe. The vegetation coverage exceeds 50% in alpine meadows, ranges from 20% to 50% in alpine steppes, and is less than 20% in alpine desert-steppes. However, rangelands are vulnerable to climate change, and many rangelands may already be at capacity or overgrazed in the face of a changing climate. There are concerns over increasing rangeland management issues in recent decades. Moreover, understanding the status of rangeland grazing under variable climates remains relatively unexplored. Hence, it is urgent to assess the impacts of climatic variability on livestock grazing rangelands for local adaptive grazing management.

Figure 1.

The location of the study area (a) and its geographic patterns of climate (b,c).

2.2. Data Gathering and Processing

Remote sensing-based NPP dataset is effectively applied in quantifying rangeland productivity and carrying capacity [39,40]. Firstly, we estimated NPP data by the Carnegie–Ames–Stanford Approach [41]. Secondly, the NPP was converted to aboveground biomass (AGB) via a series of localized parameters. The conversion factor of units of carbon is 0.45, and the ratio of belowground NPP to aboveground NPP is based on prior research [42]. The simulated AGB can be regarded as forage yield for rangeland grazing. Thus, yearly AGB was used to calculate rangeland productivity in the follow-up evaluation. This simulated AGB dataset has been verified by the field-measured biomass from 2000 to 2019 and applied in previous studies [43,44]. Furthermore, a map of percent rangeland was obtained from a 1:1,000,000 scale rangeland resource map, involving rangeland type and area (https://www.resdc.cn, accessed on 1 March 2017). According to equations applied in previous studies on Tibet [45,46], we evaluated rangeland carrying capacity.

The AGB was calculated as follows:

where AGBi is annual rangeland forage yield (kg), ANPPi and BNPPi are aboveground NPP and belowground NPP, i is a certain rangeland type i (alpine meadow and steppe), and Ai is land area of rangeland type i (m2) obtained from the rangeland resource map.

The calculation of rangeland carrying capacity was defined by Duan et al. [46]:

where Cc is rangeland carrying capacity (i.e., sustainable livestock number of grazing on rangeland, standard sheep units, SU), Ui is the proper rangeland utilization rate, Ei is the proportion of edible plants, Hi is the conversion coefficient of standard dry forage, respectively, in a certain rangeland type i. The conversion coefficients are 1 and 0.95, respectively, in the alpine meadow and steppe; utilization rates are set to 45% in the steppe, and 50% in the meadow as per the national standard (NY/T635-2015). The proportions of edible plants are 78% and 76% in the alpine meadow and steppe, respectively. I is the daily intake of dry forage for a standard sheep unit (1.32 kg/day), and D is rangeland grazing days (365 days).

The stocking rate was calculated using the following equation:

In which Sr is the actual number of livestock for each administrative district (SU/km2). Li is the actual number of a certain livestock type i (cattle, yak, and sheep) for each county, Ri is the slaughter rate of a certain livestock type I; a large animal like cattle or yak is equivalent to four standard sheep units in this study. Ai is the land area of rangeland type i.

To quantify the rangeland grazing, rangeland carrying capacity, and stocking rate are commonly used to determine grazing intensity. As defined in the literature [47,48], rangeland carrying capacity is estimated by rangeland productivity and the utilization rate of rangeland grazing. Stocking rate is calculated by the actual grazing livestock density in a unit area. Livestock density was derived from the livestock statistical data provided by the local government from 2000 to 2019 (http://data.cnki.net, accessed on 30 June 2020). The GI was defined as follows:

In which GI is the grazing intensity on rangeland, Sr (standard sheep units per square kilometer, SU/km2) is the actual grazing livestock density, Cc is the quantified rangeland carrying capacity (SU/km2). If GI > 1, it indicates that the actual livestock grazing is above the sustainable carrying capacity, and vice versa.

Precipitation data were obtained from meteorological stations covering the Tibetan Plateau (http://data.cma.cn, accessed on 22 September 2020), including monthly precipitation observation data from 2000 to 2019. Monthly sum precipitation was interpolated into raster surfaces at 1 km spatial resolution by ANUSPLIN 4.3. The interpolation data were employed to calculate the PCI and CVP.

The PCI was calculated by the following equation:

where PCI is the precipitation concentration index, pi is the monthly precipitation (mm), and i is the month.

The CVP was calculated as the standard deviation of the full time series (2000–2019) based on the mean of annual precipitation. Thus, changes in within-year and between-year precipitation variability were quantified.

2.3. Sliding Window Analysis

To examine the change in precipitation variability to rangeland grazing over the past two decades, spanning from 2000 to 2019, we used the sliding window technique to highlight longer-term trends of precipitation variability and livestock grazing. This method, as a featurization for operating long time-series data, was commonly applied in previous studies, especially for climate change and variability [49,50,51]. Given the current time series, we set a moving window of 9 years to statistically analyze the longer-term trends; a 9-year window size is feasible to separate the components of interdecadal and interannual variations [44]. This was performed to provide a more stable regression relationship for the period 2000–2019.

Moreover, to determine if the window size is the best for the stable regression relationship, we tested the regression relationship between CVP and GI by setting window sizes from 5 to 10 years. Under this scenario, a 9-year window size showed the best correlation (R2 = 0.8998, p < 0.001). Consequently, the PCI, CVP, and GI were calculated in 9-year windows moving after each calculation and ending after the last complete 9-year window (centered to 2004–2015), and the PCI and CVP also regress GI within each 9-year window.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

We utilized the Sen’s slope estimator [52] and the nonparametric Mann–Kendall test [53] to calculate the change trend and its significance value for two indicators (PCI and CVP) of precipitation variability. Then, the change trend of precipitation variability was determined by the Mann–Kendall test at a 95% confidence interval (Table 1). In addition, to identify intensive rangelands that have undergone significant precipitation variability, we performed Granger causality test and partial correlation analysis to examine the relationship between grazing intensity and precipitation variability. All the analyses were conducted in R version 4.1.0, including the “trend”, “raster”, “stats”, “ppcor”, “lmtest”, and “tseries” packages (RStudio Team, 2021).

Table 1.

The change trend of precipitation variability during 2000−2019.

3. Results

3.1. The Intra- and Inter-Annual Precipitation Variability Across Tibet

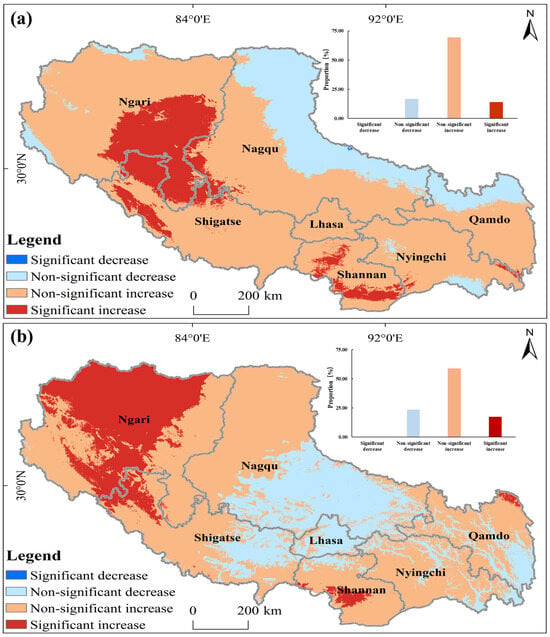

Generally, most areas experienced an increase in precipitation variability across Tibet in the period of 2000–2019 (Figure 2), mainly significant (p < 0.05) in the west region (Ngari Prefecture). Spatially, we observed broadly similar spatial patterns in increased trends of PCI and CVP, whereas a non-significant decrease was predominantly found in the north-central part of Tibet. For intra-annual precipitation variability (Figure 2a), we found that PCI increased in most areas (83.27%) during 2000–2019, but only 13.81% of the region showed statistical significance. Similarly, no significant decline was found for inter-annual precipitation variability (Figure 2b); CVP showed an increased trend in most areas (76.39%), particularly in the western region (statistically significant in 17.51%).

Figure 2.

The intra-annual and inter-annual precipitation variability across Tibet during 2000–2019. (a) Precipitation concentration index and (b) coefficient of variation in precipitation.

3.2. The Change Trend and Relationship of Precipitation Variability and Grazing Intensity

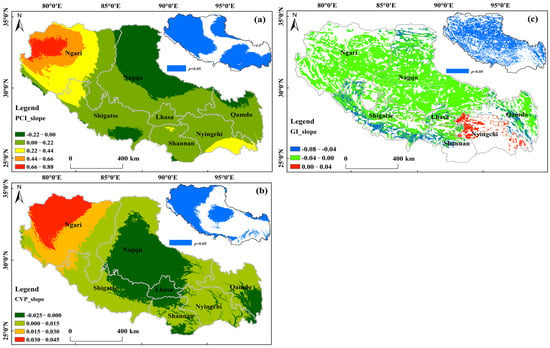

Over the whole of Tibet, PCI and CVP robustly increased (p < 0.05), particularly in Ngari Prefecture, with the slope of PCI achieving 0.88 and the slope of CVP maximally achieving 0.045 in a 9-year window size of 2004–2015 (Figure 3a,b). From spatial distribution, PCI and CVP both showed positive changes in the alpine steppe (mainly in Ngari Prefecture), whereas they had negative changes in the alpine meadow (Nagqu Prefecture). Conversely, GI in most areas significantly declined over the past 20 years, with the slope of −0.08 (Figure 3c), but it observably (p < 0.05) increased to a slope of 0.04 in Nyingchi Prefecture.

Figure 3.

The spatial-temporal changes in precipitation variability (a,b) and grazing intensity (c).

Under the stable regression relationship, we found that PCI and CVP increased significantly from 2004 (the 2000–2008 window) to 2015 (the 2011–2019 window) across Tibet (Figure 4a,b), and the maximum reached 23.23 and 0.052, respectively. On the contrary, GI decreased significantly over the last two decades (Figure 4c) and has been reduced to less than 1. At the rangeland biome scale (Figure 4d), GI had a significant (p < 0.001) correlation with both PCI (R2 = −0.89) and CVP (R2 = −0.84) for the alpine steppe. Interestingly, GI of alpine meadow was significantly correlated with PCI (R2 = −0.85, p < 0.001), but not correlated with CVP (R2 = −0.36, p > 0.05).

Figure 4.

The change trend and relationship of precipitation variability and grazing intensity. (a) precipitation concentration index; (b) coefficient of variation in precipitation; (c) grazing intensity; (d) correlation analysis, significance: *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05.

3.3. The Impact of Precipitation Variability on Alpine Rangeland Grazing

The Granger causality tests between GI and precipitation variables (PCI and CVP) showed that the causality relationships and their significance among variables exhibited consistency (Table 2). Specifically, there was no causality between GI and CVP (p > 0.05), while the causality between GI and PCI was extremely significant (p < 0.01). The above findings might be attributed to the greater influence of PCI on GI than CVP. For rangeland types, the causality relationships between GI_meadow and PCI_meadow, and between GI_steppe and PCI_steppe, were both significant (p < 0.05), whereas no significant causalities were found between GI and CVP, both in alpine meadow and steppe (p > 0.05). It is important to note that causality relationships only demonstrate the existence of causal connections between GI and PCI, and the direction and extent of the influence among variables ultimately need to be quantified through partial correlation analysis.

Table 2.

Granger causality analysis between precipitation variability and grazing intensity.

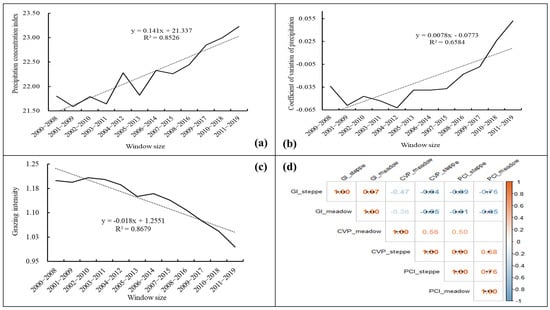

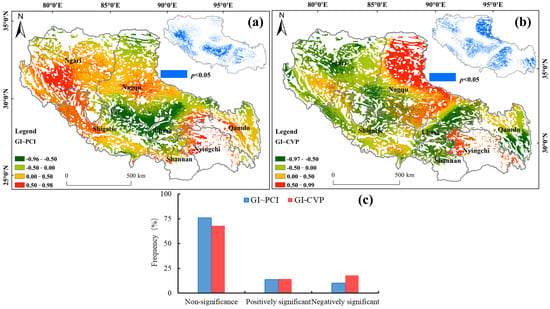

We identified a statistically significant partial correlation between precipitation variability and rangeland grazing (Figure 5). Spatially, a significant correlation was observed between GI and PCI, mainly in the central and western regions, such as Ngari Prefecture, accounting for 24.09% of the rangeland area in totality (Figure 5a,c). Comparably, the proportion of significant correlation between GI and CVP reached 32.23%, mostly including the Nagqu and Nyingchi regions (Figure 5b,c). Notably, PCI exhibited a significant positive correlation with GI in the alpine steppe of the western region (p < 0.05), but CVP showed a significant negative correlation. This indicates that, at this period, GI was primarily driven by the positive impact of PCI, while the increasing trend in PCI would increase GI in arid rangeland. Moreover, we observed that higher PCI or CVP negatively correlated with GI for the alpine meadow in the Nagqu and Lhasa regions. But both higher PCI and CVP positively correlated with GI in Nyingchi, implying that the alpine meadow with higher precipitation variability had experienced intensive livestock grazing in the period.

Figure 5.

Spatial distribution of partial correlation coefficients between grazing intensity and precipitation variables across Tibet. (a) Correlation between precipitation concentration index and grazing intensity; (b) Correlation between coefficient of variation in precipitation and grazing intensity; and (c) frequency of significance between precipitation variability and grazing intensity.

4. Discussion

4.1. Increasing Precipitation Variability Across Tibet

The greater frequency and intensity of precipitation across much of the globe have already been documented by observation studies and model experiments, for example, Zhang et al. [54] assessed precipitation variability on daily to multiyear time scales and found that most of the globe will face a wetter and more variable hydroclimate, while regional precipitation variability changes strongly region dependent because of thermodynamic effects. In the Tibetan Plateau region, Sun et al. [55] revealed that the climate became wetter over the inner Tibetan Plateau in recent decades, specifically increased summer precipitation. Additionally, extreme precipitation frequency showed a significantly increased trend in the Tibetan Plateau [56]. Broadly, we found that most area undergone increases in inter-annual and intra-annual precipitation variability during 2000–2019 over Tibet (Figure 2).

Moreover, our result on changes in observed PCI mainly mirrors previous findings from the research on the Tibetan Plateau, with a significant increase in northwestern Tibet, indicating occurrence of extreme precipitation events (drought or flood) increased in summer. Similarly, enhanced CVP was observed prevailingly over the northwestern region with arid environments but not in the southeastern region with higher precipitation, specifically highlighting the increasing importance of inter-annual precipitation variability on arid rangelands. Precipitation variability has significantly intensified across arid and semi-arid regions over the past few decades [57,58,59]. Gherardi and Sala [15] found that the increase in precipitation variability has a negative impact on dryland ANPP at the global scale, but interannual variability responded positively to dryland productivity in arid sites with mean precipitation under 300 mm/year. Our study confirmed the findings that alpine steppes with arid environments have experienced remarkable precipitation variability during the period of 2000–2019. Precipitation variability will affect water losses and ecosystem functioning in arid and semi-arid regions; the positive impacts of enhanced precipitation variability are attributed to a deepened soil water availability profile and reduced rates of bare soil evaporation [13].

4.2. The Impact of Precipitation Variability on Rangeland Grazing in Tibet

For longer-term trends, the increased slopes of PCI and CVP highlight significant intra-annual and inter-annual precipitation variability, indicating intensified rangelands have undergone a notable increase in precipitation variability over the past two decades (Figure 3a, b). Interestingly, considering the degree of precipitation variability, both PCI and CVP observably increased with more intense precipitation in the alpine steppe with arid environments (Ngari Prefecture), but significantly decreased with fewer precipitation events in the alpine meadow primarily found in Nagqu and Shigatse Prefectures. Zha et al. [38] revealed that growing season precipitation regulated rangeland productivity in dryland regions of Tibetan Plateau, but humid grasslands such as alpine meadows were controlled by the growing season temperature during 2000–2019. Gherardi and Sala [15] also reported that dryland productivity with mean precipitation over 300 mm/year responded negatively to precipitation interannual variability. The interactions of precipitation variability and grazing intensity in alpine steppes provide evidence for non-equilibrium concepts, but this is not the case in alpine meadows. Additionally, grazing intensity showed significant decline across Tibet in the period of 2000–2019 (Figure 3c and Figure 4c), which aligns with previous studies [44,60]. The reduction in grazing intensity is attributed to observably decrease in livestock population and increase in rangeland productivity. Yang et al. [61] revealed that grazing regulates the dynamic of rangeland productivity in the northern Tibet, indirectly indicating a higher decrease in livestock density correlated with an increase in rangeland productivity. In addition, the “Forage-Livestock Balance” policy was implemented as an eco-compensation system to mitigate rangeland degradation in Tibet since 2004. Yan et al. [62] quantitatively revealed that overgrazing on the Tibetan Plateau has gradually declined in recent years by ecological conservation and compensation. Similarly, we statistically identified decrease in livestock population across Tibet in the period of 2000–2019.

Although mean annual precipitation amount has long been recognized as a major driver of vegetation productivity, we argue that increasing precipitation variability is having a similarly large role on vegetation productivity over time. Our results showed both PCI and CVP had a significant correlation with GI, especially in the alpine steppe with arid environments. Compared to the annual precipitation amount, increasing variability in precipitation also significantly impacted variation in rangeland productivity. An emerging body of literature shows that rangeland productivity is controlled mainly by the amount and variability of precipitation [16,25,63]. Furthermore, recent studies recognized that precipitation variability directly impacts rangeland aboveground productivity on the Tibetan Plateau. For example, Li et al. [64] revealed that cumulative precipitation during the preseason significantly promoted AGB of alpine rangelands in arid regions. Wang et al. [65] emphasized that livestock production is affected extremely by precipitation and stocking rates in the arid steppe, especially the influence of high variation in the amount of annual precipitation on the biomass of forage. Our results are in line with these existing knowledge and field observations, increasing precipitation variability impacted alpine rangeland productivity in Tibet.

Precipitation variability acts as an important constraint on grazing capacity through impacting rangeland productivity [66,67]. We found evidence in support of this idea by evaluating the relationships between precipitation variability and grazing intensity. Generally, areas with a higher PCI have concentrated precipitation in the growing season, including the higher NPP and lower GI, whereas areas with a negative value of CVP have a low mean annual precipitation, including the lower NPP and higher GI. Lotsch et al. [68] globally observed from satellite and precipitation records that grasslands in arid and semi-arid regions are most sensitive to seasonal precipitation anomalies, especially at time scales of 4–6 months. Conversely, Ritter et al. [69] presented that arid grasslands are impacted by intra-annual precipitation variability, but the productivity increased with higher inter-annual precipitation variability. Overall, in line with current understanding, our results illustrate the interplay between precipitation variability and rangeland productivity in shaping livestock carrying capacity and alleviating grazing intensity.

In addition, the significant correlation between precipitation variability and grazing intensity provides substantial evidence to support our hypothesis that the PCI and CVP are competitive precipitation variables affecting rangeland grazing, specifically in the alpine steppe with higher precipitation variance. We identified a statistically significant correlation between PCI, CVP, and GI in the alpine steppe (Figure 4d), implying the alpine steppe has undergone intensive grazing under high precipitation variability over the last two decades. One of the particular interests in our findings is that intra-annual precipitation variability, rather than inter-annual variability, impacts grazing intensity of the alpine meadow at a statistically significant level. Moreover, the magnitude of correlations with GI differed across the indicators; PCI is more closely related to GI than CVP.

4.3. Implications for Adaptive Grazing Management of Alpine Rangeland in Tibet

A large amount of experimental evidence observed that the performance of grazing schemes is likely to impact negatively on rangeland sustainability, such as grazing intensity, livestock density, and grazing duration, together with precipitation regime, thus sustainable grazing schemes need more adaptive grazing management with more flexible strategies [70]. Nevertheless, Derner et al. [71] presented that an essential understanding of the frequency, intensity, and variability of major climatic drivers, besides mean or normal states, is necessary for adaptive grazing management in semiarid rangelands. Although the rangeland grazing depends on many influences in addition to climate, analysis using precipitation variability presented here can help targeting management relate to improve rangeland resilience and maintain livestock production in a changing precipitation. Therefore, a quantitative assessment of the performance of grazing schemes under changing precipitation regime is necessary, filling this information gap could lead to sustainable rangeland grazing.

Collectively, our findings indicate that increasing precipitation variability significantly impacted rangeland grazing across Tibet over the past two decades. In terms of long-term precipitation variability, the Granger causality test indicated that increases in intra-annual precipitation variation positively affected grazing intensity across Tibet (Table 2). This is recognized at the different rangelands around the globe, for example, Godde et al. [30] found that compared with forage productivity and supplementary feed, climate contributed the most to the herd dynamics in semi-arid Australian rangelands, particularly in increases in the inter-annual and intra-annual precipitation variability both reduced herd sizes. In addition, at rangeland biomes, GI typically respond in the different direction to changes on PCI and CVP. The map of partial correlation analysis identified that GI had a significant positive correlation with PCI in the alpine steppe of Nagqu and Ngari region, but showed a significant negative correlation with CVP (Figure 5). This highlights that, at this period, the alpine steppe with higher intra-annual precipitation variability underwent intensive rangeland grazing. The alpine steppe in this region needs to be managed conservatively to achieve production stability because of the large intra-annual variation in precipitation, which is linked with large fluctuations in rangeland productivity.

The increased precipitation variability poses an additional challenge to the climate resilience of rangeland grazing in Tibet. It is thus more difficult for livestock management to adapt to changes in variability than to changes in climate-mean states. However, Irisarri and Oesterheld [72] revealed that human interventions (livestock management) can partially decouple the expected correlation between rangeland productivity and livestock stocking rate across years, thus mitigating environmental impacts, such as precipitation variability. Furthermore. Jablonski et al. [73] concluded that optimizing stocking rate is one of crucial principles for successful livestock grazing management, particularly, setting a well-considered base stocking rate and paying attention to climatic indicators can enable timely adjustments to strategically match livestock to rangeland productivity. In the face of future variable precipitation, rangeland grazing will need to increase its adaptability to livestock management.

Our results advocate that increasing precipitation variability necessitates adaptive management strategies for rangeland grazing in Tibet. Wang et al. [74] reviewed that the rangeland productivity increases after 2000 on the Tibetan Plateau, mostly because of effective grazing management (exclude or minimize grazing), implying adaptive grazing management can restore degraded rangeland. To achieve adaptive grazing management, we suggest that alpine steppe under higher precipitation variability (e.g., PCI_slope ≥ 0.04, CVP_slope ≥ 0.002) should be subject to minimize grazing intensity, most of which would need to reduce livestock population. Specifically, the magnitude of the GI reduction is larger in alpine steppe of the central and western region (For example, Nagqu and Ngari). In addition, GI_slope can be decreased in about 0.04 to achieve optimal livestock population for adaptive grazing management, such as, alpine meadow in Shannan and Nyingchi, most of which undergone higher precipitation variability and intensive rangeland grazing in the period of 2000–2019.

4.4. Limitation

This study assessed the impact of precipitation variability on rangeland grazing across Tibet, with a focus on PCI, CVP, and GI. However, there may be other factors at play, such as temperature changes, grazing management practices, and rangeland characteristics. Increasing precipitation benefits rangeland productivity due to sufficient water supply in the arid regions, such as the alpine steppe in northwestern Tibet, but warming might negatively affect vegetation productivity [75]. In addition, the impacts of grazing management practices (excluding grazing, stocking method, and timing of grazing) on grazing intensity were not included in this study. The implications of grazing management are highly significant for rangeland productivity [76]. It is equally important that the underlying mechanisms of rangeland characteristics’ response to precipitation remain poorly understood, such as water adaptability of plants [77], plant communities’ response to precipitation [78], and precipitation legacy effects on plants [79]. Our findings also indicated that different alpine rangeland types respond differently in response to precipitation variability (Table 2). Therefore, further research should include above mentioned factors, and thus provide more specific adaptation strategies for local planners.

5. Conclusions

This study emphasizes the importance of considering precipitation variability feedback to the dynamics of rangeland grazing to accurately adapt livestock management in Tibet. Our results indicate that both inter-annual and intra-annual precipitation variability have increased across Tibet over the past two decades, with a statistically significant upward trend observed in the western region, while grazing intensity in most rangeland areas has declined significantly. Moreover, the high degree of observed coupled behavior between grazing intensity and precipitation concentration index suggests that rangeland grazing was more sensitive to intra-annual precipitation variability than inter-annual variability over the past twenty years. Notably, we identified a statistically significant partial correlation between precipitation variability and grazing intensity, further highlighting that rangelands that have experienced substantial precipitation variability and intensive grazing over the past two decades, particularly in alpine steppe with arid environments, should implement adaptive grazing management, such as excluding or minimizing grazing to reduce grazing intensity. However, the uncertainties and mechanisms underlying the effect of precipitation variability on grazing intensity remain to be further assessed under different grazing management practices and rangeland characteristics. Overall, all findings presented here can be used to target policy and management practices to adapt rangeland grazing to increasing precipitation variability. Specifically, we propose that rangelands with higher intra-annual variability, herders should diversify grazing locations or livestock population to mitigate forage scarcity, and rangelands with higher inter-annual variability, policies should incentivize flexible livestock stocking strategies or the establishment of forage reserves.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.D. and J.H.; methodology, C.D.; software, J.H.; validation, X.M., Y.Y. and H.C.; formal analysis, H.C.; investigation, H.C.; resources, Y.Y.; data curation, X.M.; writing—original draft preparation, C.D.; writing—review and editing, J.H.; visualization, Y.Y.; supervision, X.W.; project administration, X.W.; funding acquisition, C.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science and Technology Projects of Xizang Autonomous Region, China, grant number XZ202401ZY0044, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 42401366.

Data Availability Statement

Precipitation observation data used in this study can be obtained from http://data.cma.cn (accessed on 22 September 2020), and the rangeland resource map can be freely downloaded from https://www.resdc.cn (accessed on 1 March 2017).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Godde, C.M.; Garnett, T.; Thornton, P.K.; Ash, A.J.; Herrero, M. Grazing systems expansion and intensification: Drivers, dynamics, and trade-offs. Glob. Food Secur. 2018, 16, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, R.S.; Fernández-Giménez, M.E.; Galvin, K.A. Dynamics and resilience of rangelands and pastoral peoples around the globe. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2014, 39, 217–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone, R.B.; Conant, R.T.; Sircely, J.; Thornton, P.K.; Herrero, M. Climate change impacts on selected global rangeland ecosystem services. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24, 1382–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, L.A.; Allee, A.M.; Campbell, E.E.; Lynd, L.R.; Soares, J.R.; Jaiswal, D.; de Castro Oliveira, J.; dos Santos Vianna, M.; Morishige, A.E.; Figueiredo, G.K.D.A.; et al. Assessment of yield gaps on global grazed-only permanent pasture using climate binning. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 1820–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCollum, D.W.; Tanaka, J.A.; Morgan, J.A.; Mitchell, J.E.; Fox, W.E.; Maczko, K.A.; Hidinger, L.; Duke, C.S.; Kreuter, U.P. Climate change effects on rangelands and rangeland management: Affirming the need for monitoring. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2017, 3, e01264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briske, D.D.; Ritten, J.P.; Campbell, A.R.; Klemm, T.; King, A.E.H. Future climate variability will challenge rangeland beef cattle production in the Great Plains. Rangelands 2021, 43, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, O.E.; Gherardi, L.A.; Reichmann, L.; Jobbágy, E.; Peters, D. Legacies of precipitation fluctuations on primary production: Theory and data synthesis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2012, 367, 3135–3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, J.D.; Svejcar, T.; Miller, R.F.; Angell, R.A. The effects of precipitation timing on sagebrush steppe vegetation. J. Arid Environ. 2006, 64, 670–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherardi, L.A.; Sala, O.E. Enhanced interannual precipitation variability increases plant functional diversity that in turn ameliorates negative impact on productivity. Ecol. Lett. 2015, 18, 1293–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yun, X.-J.; Wei, Z.-J.; Schellenberg, M.P.; Wang, Y.-F.; Yang, X.; Hou, X.-Y. Responses of plant community and soil properties to inter-annual precipitation variability and grazing durations in a desert steppe in Inner Mongolia. J. Integr. Agric. 2014, 13, 1171–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendergrass, A.G.; Knutti, R.; Lehner, F.; Deser, C.; Sanderson, B.M. Precipitation variability increases in a warmer climate. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 17966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, K.R.; Shi, Z.; Gherardi, L.A.; Lemoine, N.P.; Koerner, S.E.; Hoover, D.L.; Bork, E.; Byrne, K.M.; Cahill, J., Jr.; Collins, S.L.; et al. Asymmetric responses of primary productivity to precipitation extremes: A synthesis of grassland precipitation manipulation experiments. Glob. Change Biol. 2017, 23, 4376–4385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, O.E.; Gherardi, L.A.; Peters, D.P.C. Enhanced precipitation variability effects on water losses and ecosystem functioning: Differential response of arid and mesic regions. Clim. Change 2015, 131, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, F.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Lao, C. Assessing the impacts of droughts on net primary productivity in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 114, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherardi, L.A.; Sala, O.E. Effect of interannual precipitation variability on dryland productivity: A global synthesis. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomey, M.L.; Collins, S.L.; Vargas, R.; Johnson, J.E.; Brown, R.F.; Natvig, D.O.; Friggens, M.T. Effect of precipitation variability on net primary production and soil respiration in a Chihuahuan Desert grassland. Glob. Change Biol. 2011, 17, 1505–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatichi, S.; Ivanov, V.Y.; Caporali, E. Investigating interannual variability of precipitation at the global scale: Is there a connection with seasonality? J. Clim. 2012, 25, 5512–5523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jiang, F.-Q.; Li, L.-H.; Wang, G. Spatial and temporal variability of precipitation concentration index, concentration degree and concentration period in Xinjiang, China. Int. J. Climatol. 2011, 31, 1679–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illius, A.W.; O’Connor, T.G. On the relevance of nonequilibrium concepts to arid and semiarid grazing systems. Ecol. Appl. 1999, 9, 798–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briske, D.D.; Fuhlendorf, S.D.; Smeins, F.E. Vegetation dynamics on rangelands: A critique of the current paradigms. J. Appl. Ecol. 2003, 40, 601–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetter, S. Rangelands at equilibrium and non-equilibrium: Recent developments in the debate. J. Arid Environ. 2005, 62, 321–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Wehrden, H.; Hanspach, J.; Kaczensky, P.; Fischer, J.; Wesche, K. Global assessment of the non-equilibrium concept in rangelands. Ecol. Appl. 2012, 22, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Fang, J.; Ma, W.; Wang, W. Relationship between variability in aboveground net primary production and precipitation in global grasslands. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2008, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloat, L.L.; Gerber, J.S.; Samberg, L.H.; Smith, W.K.; Herrero, M.; Ferreira, L.G.; Godde, C.M.; West, P.C. Increasing importance of precipitation variability on global livestock grazing lands. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, E.; Litvak, M.E.; Rudgers, J.A.; Jiang, L.; Collins, S.L.; Pockman, W.T.; Hui, D.; Niu, S.; Luo, Y. Divergent responses of primary production to increasing precipitation variability in global drylands. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 5225–5237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherardi, L.A.; Sala, O.E. Enhanced precipitation variability decreases grass- and increases shrub-productivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 12735–12740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, N.; Ren, X.; Niu, Z.; Ge, R. The adaptability of vegetation productivity to precipitation variability determines its resistance in central asian grassland ecosystems. J. Arid Environ. 2025, 230, 105428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, T. Increased precipitation variability at multi-timescales in China since the 1960s. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2025, 50, 100808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, P.; Song, J.; Fu, B. Interannual precipitation variability dominates the growth of alpine grassland above-ground biomass at high elevations on the Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 931, 172745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godde, C.; Dizyee, K.; Ash, A.; Thornton, P.; Sloat, L.; Roura, E.; Henderson, B.; Herrero, M. Climate change and variability impacts on grazing herds: Insights from a system dynamics approach for semi-arid Australian rangelands. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 3091–3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, G.; Yang, M.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; Liang, X. The precipitation variations in the Qinghai-Xizang (Tibetan) Plateau during 1961–2015. Atmosphere 2017, 8, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Yong, Z.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, W.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ye, C.; Yang, Y. Spatial and temporal patterns of the extreme precipitation across the Tibetan Plateau (1986–2015). Water 2019, 11, 1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Wang, T.; Xiao, J.; Wang, K.; Yu, W.; Du, Z.; Huang, L.; Yue, T. Grassland productivity increase was dominated by climate in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau from 1982 to 2020. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Pang, G.; Yang, M. Precipitation over the Tibetan Plateau during recent decades: A review based on observations and simulations. Int. J. Climatol. 2018, 38, 1116–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curio, J.; Scherer, D. Seasonality and spatial variability of dynamic precipitation controls on the Tibetan Plateau. Earth System. Dynamics 2016, 7, 767–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wu, J.; Feng, Y.; Niu, B.; He, Y.; Zhang, X. Climate variability rather than livestock grazing dominates changes in alpine grassland productivity across Tibet. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9, 631024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Niu, B.; Zheng, Y.; He, Y.; Cao, Y.; Feng, Y.; Wu, J. Divergent climate sensitivities of the alpine grasslands to early growing season precipitation on the Tibetan Plateau. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, X.; Niu, B.; Li, M.; Duan, C. Increasing impact of precipitation on alpine-grassland productivity over last two decades on the Tibetan Plateau. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leeuw, J.; Rizayeva, A.; Namazov, E.; Bayramov, E.; Marshall, M.T.; Etzold, J.; Neudert, R. Application of the MODIS MOD 17 net primary production product in grassland carrying capacity assessment. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2019, 78, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piipponen, J.; Jalava, M.; de Leeuw, J.; Rizayeva, A.; Godde, C.; Cramer, G.; Herrero, M.; Kummu, M. Global trends in grassland carrying capacity and relative stocking density of livestock. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 3902–3919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, C.S.; Randerson, J.T.; Field, C.B.; Matson, P.A.; Vitousek, P.M.; Mooney, H.A.; Klooster, S.A. Terrestrial ecosystem production: A process model based on global satellite and surface data. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 1993, 7, 811–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Wu, J.; Zhang, X. Effects of grazing on above- vs. below-ground biomass allocation of alpine grasslands on the northern Tibetan Plateau. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0135173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Ding, Q.; Meng, B.; Lv, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Y.; Li, M.; Yi, S. The relative contributions of climate and grazing on the dynamics of grassland NPP and PUE on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, X.; Wu, J.; Ding, Q.; Niu, B.; He, Y. Declining human activity intensity on alpine grasslands of the Tibetan Plateau. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 296, 113198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhang, X.; Niu, B.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z. Dynamic forage-livestock balance analysis in alpine grasslands on the northern Tibetan Plateau. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 238, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, C.; Shi, P.; Zong, N.; Wang, J.; Song, M.; Zhang, X. Feeding solution: Crop-livestock integration via crop-forage rotation in the southern Tibetan Plateau. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2019, 284, 106589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Shi, P.; Zhang, X.; Zong, N.; Chai, X.; Geng, S.; Zhu, W. The rangeland livestock carrying capacity and stocking rate in the Kailash Sacred Landscape in China. J. Resour. Ecol. 2017, 8, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.-W.; Shao, Q.-Q.; Liu, J.-Y.; Wang, J.-B.; Harris, W.; Chen, Z.-Q.; Zhong, H.-P.; Xu, X.-L.; Liu, R.-G. Assessment of effects of climate change and grazing activity on grassland yield in the three rivers headwaters region of Qinghai–Tibet Plateau, China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2010, 170, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smitha, P.S.; Narasimhan, B.; Sudheer, K.P.; Annamalai, H. An improved bias correction method of daily rainfall data using a sliding window technique for climate change impact assessment. J. Hydrol. 2018, 556, 100–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, J.; Li, M.; Cao, Y.; Tilahun, M.; Chen, B. The variability in sensitivity of vegetation greenness to climate change across Eurasia. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 163, 112140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.; Traxl, D.; Boers, N. Empirical evidence for recent global shifts in vegetation resilience. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, P.K. Estimates of the regression coefficient based on Kendall’s Tau. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1968, 63, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, H.B. Nonparametric tests against trend. Econometrica 1945, 13, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Furtado, K.; Wu, P.; Zhou, T.; Chadwick, R.; Marzin, C.; Rostron, J.; Sexton, D. Increasing precipitation variability on daily-to-multiyear time scales in a warmer world. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabf8021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Yang, K.; Guo, W.; Wang, Y.; He, J.; Lu, H. Why has the inner Tibetan Plateau become wetter since the Mid-1990s? J. Clim. 2020, 33, 8507–8522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Dai, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Gu, L. Ancient wisdom: A new perspective on the past and future Chinese precipitation patterns based on the twenty-four solar terms. J. Hydrol. 2024, 641, 131873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhou, H.; Du, L.; Yao, H.; Wang, H. Precipitation trends and variability from 1950 to 2000 in arid lands of Central Asia. J. Arid Land 2015, 7, 514–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zheng, C.; Ma, Y. Variations in precipitation extremes in the arid and semi-arid regions of China. Int. J. Climatol. 2021, 41, 1542–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, R.; Scholz, M. Climate variability impact on the spatiotemporal characteristics of drought and aridity in arid and semi-arid regions. Water Resour. Manag. 2019, 33, 5015–5033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Liu, Y.; Zu, J.; Zhang, J. The influences of climate change and human activities on vegetation dynamics in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wu, J.; Niu, B.; Li, M. Mitigating the negative effects of droughts on alpine grassland productivity in the northern Xizang Plateau via degradation-combating actions. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 134, 104171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Kong, L.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Hu, J.; Ouyang, Z. Grass-livestock balance under the joint influences of climate change, human activities and ecological protection on Tibetan Plateau. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 162, 112040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.-S.; Reynolds, J.F.; Sun, G.-J.; Li, F.-M. Impacts of increased variability in precipitation and air temperature on net primary productivity of the Tibetan Plateau: A modeling analysis. Clim. Change 2013, 119, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhu, W.; He, B. Regional differences in the impact paths of climate on aboveground biomass in alpine grasslands across the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 947, 174421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Jiao, S.; Han, G.; Zhao, M.; Willms, W.D.; Hao, X.; Wang, J.; Din, H.; Havstad, K.M. Impact of stocking rate and rainfall on sheep performance in a desert steppe. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2011, 64, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Houérou, H.N.; Bingham, R.L.; Skerbek, W. Relationship between the variability of primary production and the variability of annual precipitation in world arid lands. J. Arid Environ. 1988, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, J.S.; Adler, P.B. Anticipating changes in variability of grassland production due to increases in interannual precipitation variability. Ecosphere 2014, 5, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotsch, A.; Friedl, M.A.; Anderson, B.T.; Tucker, C.J. Coupled vegetation-precipitation variability observed from satellite and climate records. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2003, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, F.; Berkelhammer, M.; Garcia, C. Distinct response of gross primary productivity in five terrestrial biomes to precipitation variability. Commun. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- di Virgilio, A.; Lambertucci, S.A.; Morales, J.M. Sustainable grazing management in rangelands: Over a century searching for a silver bullet. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2019, 283, 106561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derner, J.D.; Budd, B.; Grissom, G.; Kachergis, E.J.; Augustine, D.J.; Wilmer, H.; Scasta, J.D.; Ritten, J.P. Adaptive grazing management in semiarid rangelands: An outcome-driven focus. Rangelands 2022, 44, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irisarri, J.G.N.; Oesterheld, M. Temporal variation of stocking rate and primary production in the face of drought and land use change. Agric. Syst. 2020, 178, 102750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonski, K.E.; Derner, J.D.; Bailey, D.W.; Davies, K.W.; Meiman, P.J.; Roche, L.M.; Thacker, E.T.; Vermeire, L.T.; Stackhouse-Lawson, K.R. Principles for successful livestock grazing management on western US rangelands. Rangelands 2023, 46, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lv, W.; Xue, K.; Wang, S.; Zhang, L.; Hu, R.; Zeng, H.; Xu, X.; Li, Y.; Jiang, L.; et al. Grassland changes and adaptive management on the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 668–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gao, Q.; Dong, S.; Liu, S.; Wang, X.; Su, X.; Li, Y.; Tang, L.; Wu, X.; Zhao, H. Effects of grazing and climate warming on plant diversity, productivity and living state in the alpine rangelands and cultivated grasslands of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Rangel. J. 2015, 37, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, B.; Delaby, L.; Pierce, K.M.; McCarthy, J.; Fleming, C.; Brennan, A.; Horan, B. The multi-year cumulative effects of alternative stocking rate and grazing management practices on pasture productivity and utilization efficiency. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 3784–3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munson, S.M.; Duniway, M.C.; Johanson, J.K. Rangeland monitoring reveals long-term plant responses to precipitation and grazing at the landscape scale. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 69, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derner, J.D.; Hess, B.W.; Olson, R.A.; Schuman, G.E. Functional group and species responses to precipitation in three semi-arid rangeland ecosystems. Arid Land Res. Manag. 2008, 22, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Wang, J.; Peltier, D.M.P.; Ritter, F.; Ciais, P.; Peñuelas, J.; Xiao, J.; Crowther, T.W.; Li, X.; Ye, J.-S.; et al. Lagged precipitation effects on plant production across terrestrial biomes. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2025, 9, 1800–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).