ADS-LI: A Drone Image-Based Segmentation Model for Sustainable Maintenance of Lightning Rods and Insulators in Steel Plant Power Infrastructure

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background of Study

1.2. Problem Statement and Research Objectives

- A PointRend-based instance segmentation model is constructed to accurately recognize lightning rods and insulators from the images captured using a drone.

- A diagnosis model is designed to quantitatively determine anomalies based on the results.

- The aforementioned two models are integrated to implement ADS-LI, which automatically detects anomalies when the user uploads drone images.

1.3. Research Process

2. Literature Review

2.1. Advances in Equipment Maintenance Strategies

2.2. PdM Using Machine Learning Technology

2.3. AI-Based Diagnostics for Electrical Equipment

2.4. Object Detection-Based PdM

2.5. Limitation of Previous Research

- An object detection model that can automatically identify insulators and lightning rods from drone images was developed. The model is configured to robustly detect repetitive shapes and linear structures under diverse environmental conditions, and it simultaneously performs object classification and localization.

- Quantitative indicators are designed to numerically encode traditional qualitative decision rules. For lightning rods, anomalies are determined based on deviations in the slope between centroid coordinates. For insulators, anomalies are determined based on the effective area preservation ratio.

- An automated diagnostic system that integrates object detection and anomaly decision functions was implemented. Users can simply upload images and automatically obtain equipment recognition and anomaly diagnosis results.

- Conventional visual inspection methods suffer from work safety risks and long diagnostic times. By applying drone and AI technologies, the proposed approach enables non-contact diagnosis of elevated equipment and improves diagnostic efficiency and worker safety.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. ADS-LI Dataset Construction

3.1.1. Data Acquiring

3.1.2. Data Cleaning and Standardization

3.1.3. Data Labeling

3.2. ADS-LI Architecture

3.3. Instance Segmentation Module

3.3.1. Model Training

3.3.2. Fine-Tuning

3.4. Anomaly Detection Module

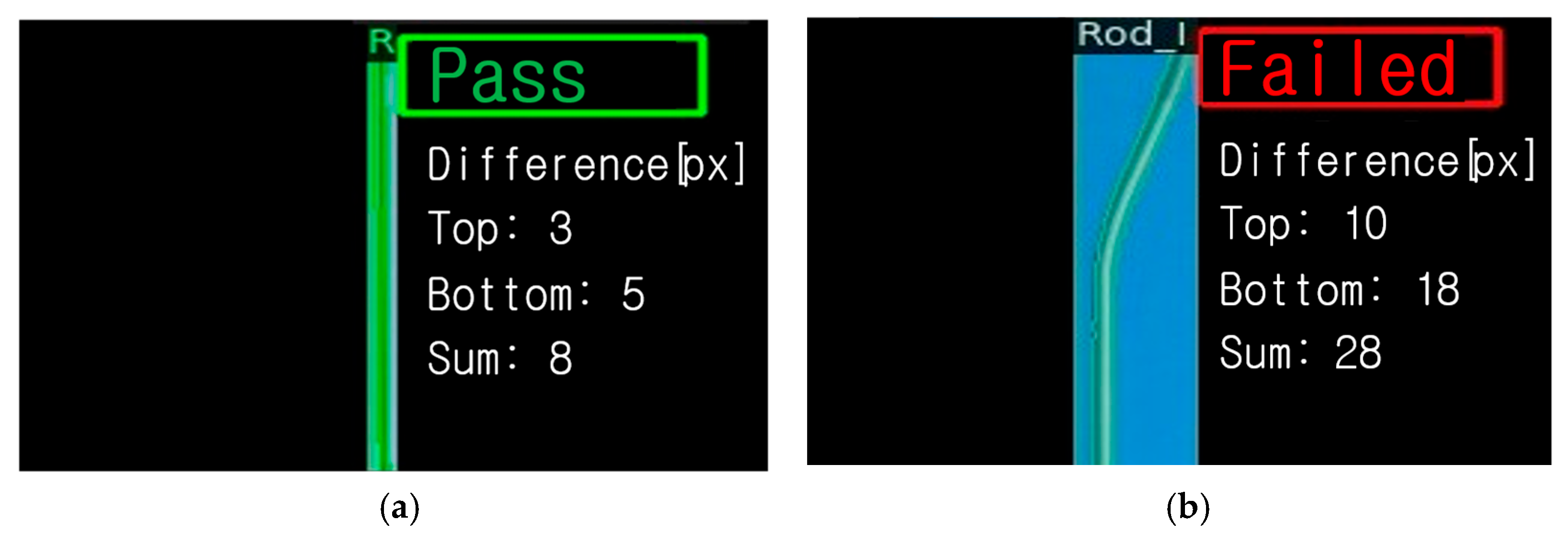

3.4.1. Lightning Rod Anomaly Detection

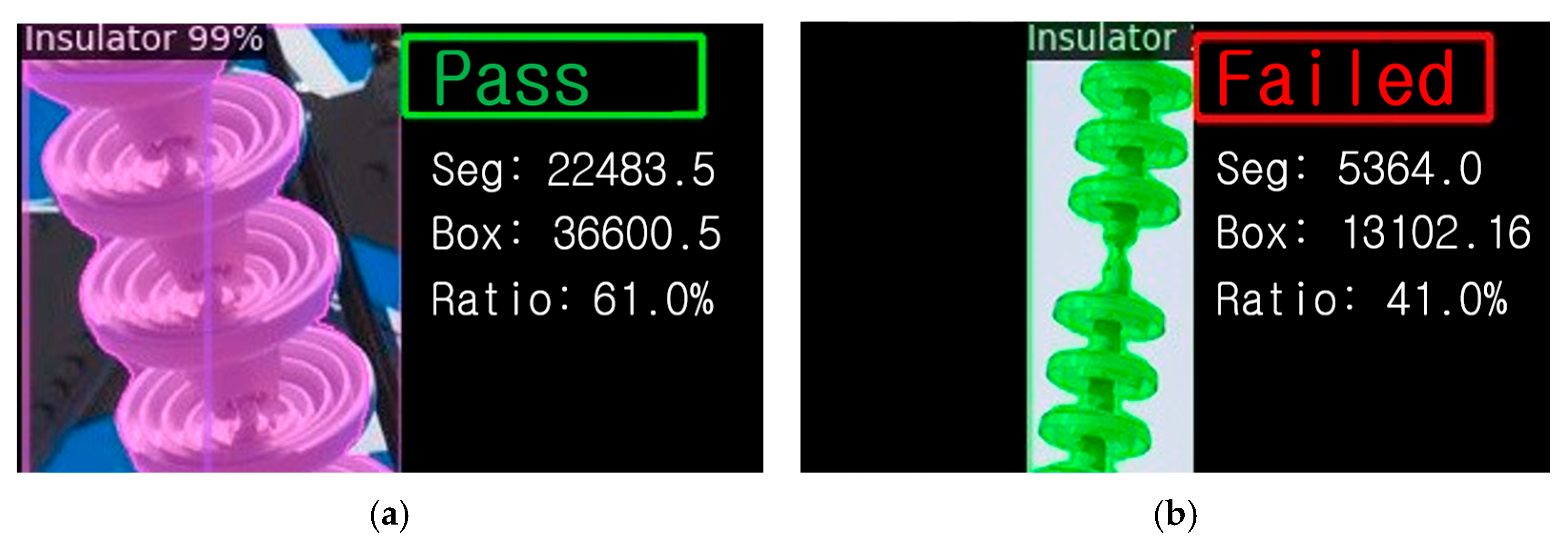

3.4.2. Insulator Anomaly Detection

3.5. Experimental Setting

3.5.1. Metrics for Instance Segmentation Evaluation

3.5.2. Metrics for Anomaly Detection Evaluation

- Lightning-rod diagnostic criterion: center-coordinate tilt ; threshold .

- Insulator diagnostic criterion: mask area ratio ; threshold .

- True Positive (TP): Abnormal objects are accurately classified as abnormal objects.

- True Negative (TN): Normal objects are accurately classified as normal objects.

- False Positive (FP): Normal objects are misclassified as abnormal objects.

- False Negative (FN): Abnormal objects are misclassified as normal objects.

3.5.3. Experimental Environment

| Listing 1. Python code for the lightning-rod bending function. |

| def bending(cnt): x_ = [p[0][0] for p in cnt] y_ = [p[0][1] for p in cnt] max_x = x_[findNearNum(y_, np.max(y_))[0]] mid_x = x_[findNearNum(y_, np.mean(y_))[0]] min_x = x_[findNearNum(y_, np.min(y_))[0]] return (max_x, mid_x, min_x) |

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

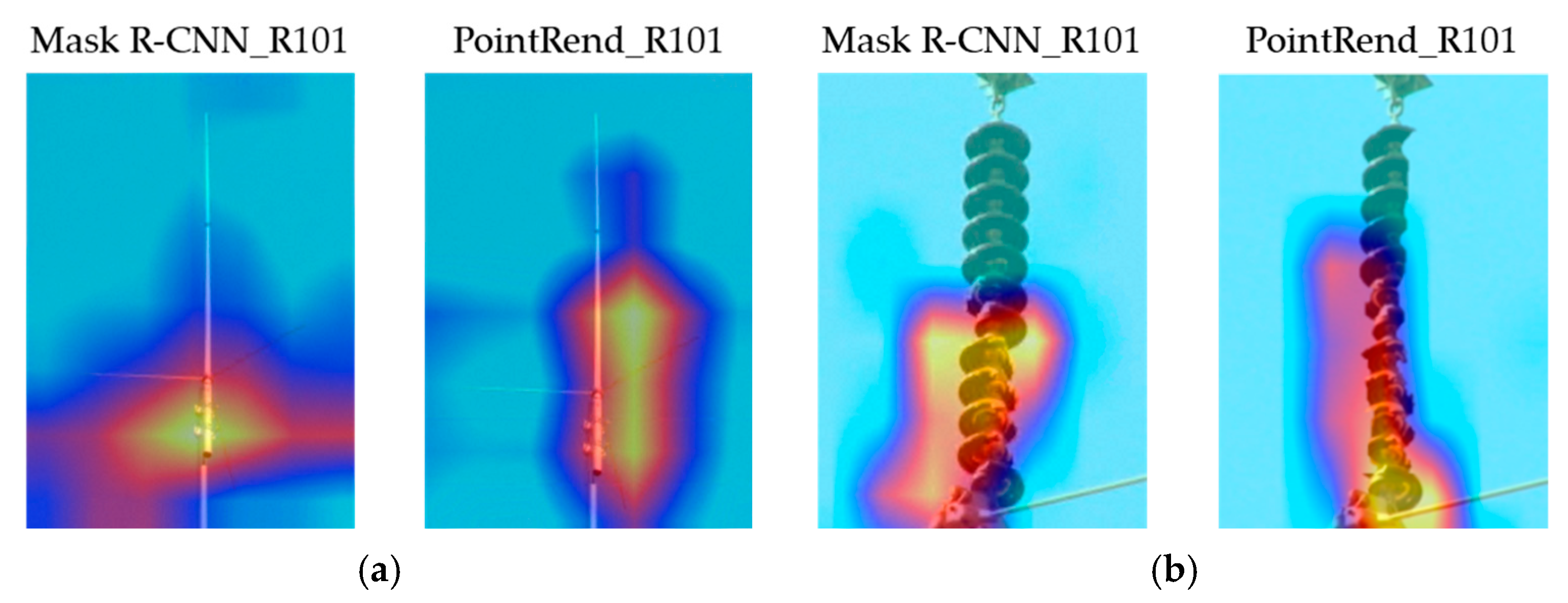

4.1. Instance Segmentation

4.2. Anomaly Detection

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Summary and Contributions

6.2. Future Studies and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| AP | Average Precision |

| CBM | Condition-Based Maintenance |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| COCO | Common Objects in Context |

| CV | Computer Vision |

| DGA | Dissolved Gas Analysis |

| FCN | Fully Convolutional Network |

| FPS | Frames Per Second |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| JSON | JavaScript Object Notation |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| PdM | Predictive Maintenance |

| R-CNN | Region-based Convolutional Neural Network |

| RoI | Region of Interest |

| RTK | Real-Time Kinematic |

| SHM | Structural Health Monitoring |

| TN | True Negative |

| TP | True Positive |

| FN | False Negative |

| FP | False Positive |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

| Absolute Deviation Sum (unit: px) | |

| Area Ratio (unit: %) | |

| Bounding Box Area of Insulator (unit: px2) | |

| Segmentation Area of Insulator (unit: px2) | |

| Point Top | |

| Point Middle | |

| Point Bottom | |

| Threshold for Lightning Rod (unit: px) | |

| Threshold for Insulator (unit: %) |

References

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Power Systems in Transition. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/power-systems-in-transition (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Electricity 2025. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/electricity-2025 (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- U.S. Department of Energy. Transforming the Nation’s Electricity System: The Second Installment of the Quadrennial Energy Review. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2017/02/f34/Quadrennial%20Energy%20Review%20Summary%20for%20Policymakers.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- IEEE Std 1243-1997; IEEE Guide for Improving the Lightning Performance of Transmission Lines. IEEE Standards Association: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1997; pp. 1–44.

- NFPA 780; Standard for the Installation of Lightning Protection Systems 2020. National Fire Protection Association (NFPA): Quincy, MA, USA, 2020. Available online: https://edufire.ir/storage/Library/other/NFPA%20780-2020.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Li, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, W. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle for Transmission Line Inspection: Status, Standardization, and Perspectives. Front. Energy Res. 2021, 9, 713634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Employment and Labor. 2023 Industrial Accident Status Analysis. Available online: https://www.moel.go.kr/policy/policydata/view.do?bbs_seq=20241201548 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Zhai, F.; Yang, T.; Chen, H.; He, B.; Li, S. Intrusion Detection Method Based on CNN–GRU–FL in a Smart Grid Environment. Electronics 2023, 12, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Shang, W. Hyperspectral Anomaly Detection Based on Spectral Similarity Variability Feature. Sensors 2024, 24, 5664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pix4D. 60% Faster Transmission Tower Inspections with Drones. Available online: https://www.pix4d.com/blog/transmission-tower-inspections (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- Xin, M.; Xu, C.; Gao, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, B. High-Precision Recognition Algorithm for Equipment Defects Based on Mask R-CNN Algorithm Framework in Power System. Processes 2024, 12, 2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, M.A.A.; Mecheter, I.; Qiblawey, Y.; Fernandez, J.H.; Chowdhury, M.E.H.; Kiranyaz, S. Deep learning in automated power line inspection: A review. Appl. Energy 2025, 385, 125507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.R.; Haider, Z.M.; Malik, F.H.; Almasoudi, F.M.; Alatawi, K.S.S.; Bhutta, M.S. A Comprehensive Review of Microgrid Energy Management Strategies Considering Electric Vehicles, Energy Storage Systems, and AI Techniques. Processes 2024, 12, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, D.Y.; Jin, I.J.; Bang, I.C. Heat-vision based drone surveillance augmented by deep learning for critical industrial monitoring. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraaba, L.; Al-Soufi, K.; Ssennoga, T.; Memon, A.M.; Worku, M.Y.; Alhems, L.M. Contamination Level Monitoring Techniques for High-Voltage Insulators: A Review. Energies 2022, 15, 7656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, G.A.; Hassan, W.; Mahmood, F.; Shafiq, M.; Rehman, H.; Kay, J.A. Review on Partial Discharge Diagnostic Techniques for High Voltage Equipment in Power Systems. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 51382–51394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waleed, D.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Tariq, U.; El-Hag, A.H. Drone-Based Ceramic Insulators Condition Monitoring. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 6007312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojek, I.; Jasiulewicz-Kaczmarek, M.; Piechowski, M.; Mikołajewski, D. An Artificial Intelligence Approach for Improving Maintenance to Supervise Machine Failures and Support Their Repair. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Fu, H.; Zheng, Y.; Tao, F.; Liu, Y. The advance of digital twin for predictive maintenance: The role and function of machine learning. J. Manuf. Syst. 2023, 71, 581–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werbińska-Wojciechowska, S.; Giel, R.; Winiarska, K. Digital Twin Approach for Operation and Maintenance of Transportation System—Systematic Review. Sensors 2024, 24, 6069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Flanigan, K.A.; Bergés, M. State-of-the-art review and synthesis: A requirement-based roadmap for standardized predictive maintenance automation using digital twin technologies. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2024, 62, 102800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikołajewska, E.; Mikołajewski, D.; Mikołajczyk, T.; Paczkowski, T. Generative AI in AI-Based Digital Twins for Fault Diagnosis for Predictive Maintenance in Industry 4.0/5.0. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J.; Rios-Colque, L.; Peña, A.; Rojas, L. Condition Monitoring and Predictive Maintenance in Industrial Equipment: An NLP-Assisted Review of Signal Processing, Hybrid Models, and Implementation Challenges. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, A.; Khan, M.A.; Akram, U.; Obidallah, W.J.; Jawed, S.; Ahmad, A. Deep learning based approaches for intelligent industrial machinery health management and fault diagnosis in resource-constrained environments. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apeiranthitis, S.; Zacharia, P.; Chatzopoulos, A.; Papoutsidakis, M. Predictive Maintenance of Machinery with Rotating Parts Using Convolutional Neural Networks. Electronics 2024, 13, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunyan, S.T.; Khan, Z.H.; Al-Haddad, L.A.; Dhahad, H.A.; Al-Karkhi, M.I.; Ogaili, A.A.F.; Al-Sharify, Z.T. Intelligent Thermal Condition Monitoring for Predictive Maintenance of Gas Turbines Using Machine Learning. Machines 2025, 13, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, T. Comparison of deep learning models for predictive maintenance in industrial manufacturing systems using sensor data. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 23545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleem, F.; Ahmad, Z.; Siddique, M.F.; Umar, M.; Kim, J.-M. Acoustic Emission-Based Pipeline Leak Detection and Size Identification Using a Customized One-Dimensional DenseNet. Sensors 2025, 25, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aminzadeh, A.; Sattarpanah Karganroudi, S.; Majidi, S.; Dabompre, C.; Azaiez, K.; Mitride, C.; Sénéchal, E. A Machine Learning Implementation to Predictive Maintenance and Monitoring of Industrial Compressors. Sensors 2025, 25, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Yogi, B.; Majumdar, R.; Ghosh, P.; Das, S.K. Deep learning-based crack detection and prediction for structural health monitoring. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Yang, W.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, A.; Liu, J.; Lou, T.; Zhang, J. Insulator Defect Detection Based on YOLOv8s-SwinT. Information 2024, 15, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhai, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Ye, G.; Jin, S. Insulator Defect Detection Based on ML-YOLOv5 Algorithm. Sensors 2024, 24, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngwenyama, M.K.; Gitau, M.N. Discernment of transformer oil stray gassing anomalies using machine learning classification techniques. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalila, R.A.M.; Turkben, A.K. Artificial intelligence based partial discharge detection using CNN and KNN to increase the quality of electrical insulation. Discov. Comput. 2025, 28, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eang, C.; Lee, S. Predictive Maintenance and Fault Detection for Motor Drive Control Systems in Industrial Robots Using CNN-RNN-Based Observers. Sensors 2025, 25, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pohakar, P.; Gandhi, R.; Hans, S.; Sharma, G.; Bokoro, P.N. Analysis of multiple faults in induction motor using machine learning techniques. e-Prime Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 2025, 12, 101007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamakloe, E.; Kommey, B.; Kponyo, J.J.; Tchao, E.T.; Agbemenu, A.S.; Klogo, G.S. Predictive AI Maintenance of Distribution Oil-Immersed Transformer via Multimodal Data Fusion: A New Dynamic Multiscale Attention CNN-LSTM Anomaly Detection Model for Industrial Energy Management. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2025, 19, e70011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Li, D.; Li, D.; Li, X.; Gao, Q.; Yu, X. A Lightweight Insulator Defect Detection Model Based on Drone Images. Drones 2024, 8, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, T.; Cunha, T.; Dias, A.; Moreira, A.P.; Almeida, J. UAV Visual and Thermographic Power Line Detection Using Deep Learning. Sensors 2024, 24, 5678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Nashik, S.; Huang, C.; Aibin, M.; Coria, L. Next-Gen Remote Airport Maintenance: UAV-Guided Inspection and Maintenance Using Computer Vision. Drones 2024, 8, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.; Nazario Dejesus, E.; Shekaramiz, M.; Zander, J.; Memari, M. Identification and Localization of Wind Turbine Blade Faults Using Deep Learning. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Vazquez, J.; Prieto-Centeno, I.; Fernandez-Cortizas, M.; Perez-Saura, D.; Molina, M.; Campoy, P. Real-Time Object Detection for Autonomous Solar Farm Inspection via UAVs. Sensors 2024, 24, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barraz, Z.; Sebari, I.; Lamrini, N.; Ait El Kadi, K.; Ait Abdelmoula, I. Fast and automatic solar module geo-labeling for optimized large-scale photovoltaic systems inspection from UAV thermal imagery using deep learning segmentation. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2025, 28, 101048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, D.; Jin, I.J.; Bang, I.C. Advanced thermal monitoring in scaled reactors using deep learning-enhanced drone IR imaging. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 2025, 62, 1180–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intel Corporation. Intel Falcon 8+ System. Available online: https://www.intel.cn/content/dam/www/public/us/en/documents/product-briefs/falcon-8-plus-product-brief.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Saberironaghi, A.; Ren, J.; El-Gindy, M. Defect Detection Methods for Industrial Products Using Deep Learning Techniques: A Review. Algorithms 2023, 16, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, M. Enlarging smaller images before inputting into convolutional neural network: Zero-padding vs. interpolation. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Lin, S.; Cheng, G.; Yao, X.; Ren, H.; Wang, W. Object Detection in Remote Sensing Images Based on Improved Bounding Box Regression and Multi-Level Features Fusion. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenCV. Geometric Image Transformations. Available online: https://docs.opencv.org/4.5.5/da/d54/group__imgproc__transform.html (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Ecma International. ECMA-404: The JSON Data Interchange Syntax, 2nd ed.; December 2017; Available online: https://ecma-international.org/publications-and-standards/standards/ecma-404 (accessed on 24 July 2025).

- COCO Consortium. COCO—Common Objects in Context: Data Format Overview. Available online: https://cocodataset.org/ (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Lin, T.Y.; Maire, M.; Belongie, S.; Hays, J.; Perona, P.; Ramanan, D.; Dollár, P.; Zitnick, C.L. Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context. In Proceedings of the 13th European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 740–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask R-CNN. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2020, 42, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- POSCO. POSAI VISION. Available online: http://posai-vision-nginx.psfai.posco.com (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Shi, J.; Chen, G.; Chen, Y. Enhanced boundary perception and streamlined instance segmentation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 23612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, Y.; Kim, Y.; Park, J.; Ji, B. Rock Joint Segmentation in Drill Core Images via a Boundary-Aware Token-Mixing Network. Buildings 2025, 15, 3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Sulaiman, N.A.A.; Ding, Y.; Zhao, J. Innovative segmentation technique for aerial power lines via amplitude stretching transform. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Goodacre, R. On Splitting Training and Validation Set: A Comparative Study of Cross-Validation, Bootstrap and Systematic Sampling for Estimating the Generalization Performance of Supervised Learning. J. Anal. Test. 2018, 2, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M.; Podishetti, R.; Koval, L.; Gaafar, M.A.; Grossmann, D.; Bregulla, M. The Effect of Annotation Quality on Wear Semantic Segmentation by CNN. Sensors 2024, 24, 4777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabernik, D.; Šela, S.; Skvarč, J.; Skočaj, D. Segmentation-based deep-learning approach for surface-defect detection. J. Intell. Manuf. 2020, 31, 759–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clabaut, É.; Lemelin, M.; Germain, M.; Bouroubi, Y.; St-Pierre, T. Model Specialization for the Use of ESRGAN on Satellite and Airborne Imagery. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, Z.; Gu, Z.; Li, W. Research on floating object classification algorithm based on convolutional neural network. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 32086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, O.L.F.; de Carvalho Júnior, O.A.; e Silva, C.R.; de Albuquerque, A.O.; Santana, N.C.; Borges, D.L.; Gomes, R.A.T.; Guimarães, R.F. Panoptic Segmentation Meets Remote Sensing. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hütten, N.; Alves Gomes, M.; Hölken, F.; Andricevic, K.; Meyes, R.; Meisen, T. Deep Learning for Automated Visual Inspection in Manufacturing and Maintenance: A Survey of Open-Access Papers. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2024, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.-Y.A.; Lin, C.-C.; Huang, H.-C.; Su, W.-C.; Cheng, C.-Y. Anomaly Detection for Semiconductor Wafer Multi-Wire Sawing Machines Using Statistical and Deep Learning Methods. Mob. Netw. Appl. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, R.C.; Woods, R.E. Digital Image Processing, 4th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2018; pp. 47–70. [Google Scholar]

- OpenCV. Camera Calibration and 3D Reconstruction. Available online: https://docs.opencv.org/4.5.5/d9/d0c/group__calib3d.html (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Chen, L.; Chang, J.; Xu, J.; Yang, Z. Automatic Measurement of Inclination Angle of Utility Poles Using 2D Image and 3D Point Cloud. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grumbach, F.; Müller, A.; Reusch, P.; Trojahn, S. Robustness Prediction in Dynamic Production Processes—A New Surrogate Measure Based on Regression Machine Learning. Processes 2023, 11, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avendaño, J.C.; Leander, J.; Karoumi, R. Image-Based Concrete Crack Detection Method Using the Median Absolute Deviation. Sensors 2024, 24, 2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-End Object Detection with Transformers. In Proceedings of the 16th European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Jiao, X.; Yuan, B. TLINet: A defects detection method for insulators of overhead transmission lines using partially transformer block. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0327139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Gill, S.S. Edge AI: A survey. Internet Things Cyber Phys. Syst. 2023, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenCV. Contour Properties. Available online: https://docs.opencv.org/4.5.5/d1/d32/tutorial_py_contour_properties.html (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Wu, J.; Deng, Q.; Xian, R.; Tao, X.; Zhou, Z. An Instance Segmentation Method for Insulator Defects Based on an Attention Mechanism and Feature Fusion Network. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittino, F.; Puggl, M.; Moldaschl, T.; Hirschl, C. Automatic Anomaly Detection on In-Production Manufacturing Machines Using Statistical Learning Methods. Sensors 2020, 20, 2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, M.; Zhao, Y.; Avdelidis, N.P. A Fault Detection Approach Based on One-Sided Domain Adaptation and Generative Adversarial Networks for Railway Door Systems. Sensors 2023, 23, 9688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, T.; Li, B.; Yang, J.; Xia, Y.; Qian, J. Theoretical Research on Suspension Bridge Cable Damage Assessment Based on Vehicle-Induced Cable Force. Buildings 2024, 14, 3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Gao, Z.; Zhuang, J.; Huang, D.; Huang, G.; Wang, H.; Pei, J.; Zheng, J.; Liu, C. MSMT-RTDETR: A Multi-Scale Model for Detecting Maize Tassels in UAV Images with Complex Field Backgrounds. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.-W.; Choi, S.-W.; Lee, E.-B. Study on Energy Efficiency and Maintenance Optimization of Run-Out Table in Hot Rolling Mills Using Long Short-Term Memory-Autoencoders. Energies 2025, 18, 2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Kirillov, A.; Massa, F.; Lo, W.-Y.; Girshick, R. Detectron2. 2019. Available online: https://github.com/facebookresearch/detectron2 (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- NVIDIA. CUDA Toolkit Documentation. Available online: https://docs.nvidia.com/cuda (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- PyTorch Foundation. PyTorch documentation. Available online: https://docs.pytorch.org/docs/1.10 (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Canonical. Ubuntu 20.04 LTS Release Notes. Available online: https://wiki.ubuntu.com/FocalFossa/ReleaseNotes (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- NVIDIA. NVIDIA RTX A5000. Available online: https://resources.nvidia.com/en-us-briefcase-for-datasheets/nvidia-rtx-a5000-dat-1 (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Chopra, P.; Yadav, S.K. Restricted Boltzmann machine and softmax regression for fault detection and classification. Complex Intell. Syst. 2018, 4, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmström, M.; Skog, I.; Axehill, D.; Gustafsson, F. Uncertainty quantification in neural network classifiers—A local linear approach. Automatica 2024, 163, 111563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirillov, A.; Wu, Y.; He, K.; Girshick, R. PointRend: Image Segmentation as Rendering. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 9796–9805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Cogswell, M.; Das, A.; Vedantam, R.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Grad-CAM: Visual Explanations from Deep Networks via Gradient-Based Localization. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ding, Y.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, E.; Wu, Z.; Shao, L. Surface Defect Detection Methods for Industrial Products: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Tao, C.; Cao, X.; Tsung, F. 3D vision-based anomaly detection in manufacturing: A survey. Front. Eng. Manag. 2025, 12, 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, T.; Zheng, Y.; Zhao, L.; Zheng, E. Industrial Product Surface Anomaly Detection with Realistic Synthetic Anomalies Based on Defect Map Prediction. Sensors 2024, 24, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cazzato, D.; Cimarelli, C.; Sanchez-Lopez, J.L.; Voos, H.; Leo, M. A Survey of Computer Vision Methods for 2D Object Detection from Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. J. Imaging 2020, 6, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Set Value |

|---|---|

| Number of epochs | 300 |

| Batch size | 4 |

| Test | (px) | Normal Detection for Lightning Rods | Model Selection |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 5 | 9 | |

| 2nd | 10 | 10 | *✓ |

| 3rd | 15 | 10 | |

| 4th | 20 | 10 |

| Test | (%) | Normal Detection for Insulators | Model Selection |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 30 | 10 | |

| 2nd | 35 | 10 | |

| 3rd | 40 | 10 | |

| 4th | 45 | 10 | |

| 5th | 50 | 10 | |

| 6th | 55 | 10 | *✓ |

| 7th | 60 | 9 | |

| 8th | 65 | 8 | |

| 9th | 70 | 8 |

| Item | Version |

|---|---|

| Programming language | Python 3.8.18 |

| Key framework | Detectron2 v0.6 |

| Instance segmentation model | PointRend_R101 |

| Deep learning framework | PyTorch 1.10.2 |

| CUDA version | CUDA 11.3 |

| Image processing library | OpenCV 4.5.5 |

| Operating system | Ubuntu 20.04 LTS |

| GPU specification | NVIDIA RTX A5000 (24 GB) |

| Model | Backbone | Size (Pixel) | (%) | (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mask R-CNN | R101-FPN | 1280 | 48.2 | 32.1 |

| PointRend | R101-FPN | 1280 | 51.8 | 35.1 |

| Category | TP | TN | FP | FN | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lightning rods | 2 | 43 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Insulators | 2 | 42 | 1 | 0 | 0.98 | 0.67 | 1 | 0.80 |

| Total | 4 | 85 | 1 | 0 | 0.99 | 0.80 | 1 | 0.89 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, H.-R.; Choi, S.-W.; Lee, E.-B.; Kim, G.-W. ADS-LI: A Drone Image-Based Segmentation Model for Sustainable Maintenance of Lightning Rods and Insulators in Steel Plant Power Infrastructure. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11151. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411151

Kim H-R, Choi S-W, Lee E-B, Kim G-W. ADS-LI: A Drone Image-Based Segmentation Model for Sustainable Maintenance of Lightning Rods and Insulators in Steel Plant Power Infrastructure. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11151. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411151

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Hyeong-Rok, So-Won Choi, Eul-Bum Lee, and Geon-Woo Kim. 2025. "ADS-LI: A Drone Image-Based Segmentation Model for Sustainable Maintenance of Lightning Rods and Insulators in Steel Plant Power Infrastructure" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11151. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411151

APA StyleKim, H.-R., Choi, S.-W., Lee, E.-B., & Kim, G.-W. (2025). ADS-LI: A Drone Image-Based Segmentation Model for Sustainable Maintenance of Lightning Rods and Insulators in Steel Plant Power Infrastructure. Sustainability, 17(24), 11151. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411151