Abstract

Rapid urbanization and widening urban–rural disparities have contributed to decreasing youth engagement with rural development in China. As traditional outreach initiatives struggle to attract young people’s attention, immersive digital technologies have emerged as promising tools for strengthening connections to rural environments. This study explores how immersive virtual reality (VR) experiences shape university students’ behavioral intentions toward rural engagement. Using a cognitive–affective–behavioral (CAB) framework, an immersive VR experiment was conducted with 209 Chinese undergraduates using a panoramic rural video. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) validated a serial mediation model linking perceived sensory dimensions, restorative experiences (RE), and place identity (PI) to rural visit intention (RVI) and environmentally responsible behavioral intention (ERBI). The results show that VR significantly enhances RE and PI, with PI serving as the stronger mediator, particularly for students with limited rural exposure. Multigroup analysis further revealed demographic heterogeneity: women demonstrated stronger RE–PI pathways, while urban and short-term rural residents showed greater sensitivity to VR-induced presence. Overall, the findings indicate that immersive VR can reduce urban–rural psychological distance and strengthen youth engagement. The study demonstrates how digital immersive tools may support targeted education and policy interventions aimed at promoting sustainable rural development.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the outflow of young talent from rural China—especially university students aged 18–22 years—has intensified. Despite initiatives such as the One Village, One University Student program, only about 28% of students report willingness to work in rural areas, and smaller proportion ultimately return [1]. Despite approximately 470,000 young people participating in grassroots revitalization programs in 2021, sustained engagement remains limited [2]. This persistent talent gap has become a structural constraint on rural development, even as China’s National Rural Revitalization Strategy positions youth as a central force in promoting sustainable rural transformation [3]. Similar patterns of weak emotional attachment and low behavioral involvement among young people have been documented in other rapidly urbanizing countries, highlighting a broader global challenge [4]. The issue is closely related to urban–rural psychological distance, which reflects not only geographic separation but also cognitive and affective disconnection from rural spaces [5,6]. Recent policy emphasis on digital empowerment for rural revitalization raises new opportunities for engaging youth [7]. However, the effectiveness of these digital initiatives depends on a clear understanding of the psychological mechanisms—particularly how technologies can alter youth’s cognition, emotion, and behavior regarding rural life. The cognitive–affective–behavioral (CAB) framework thus offers a compelling lens for exploring how immersive experiences can reforge youths’ emotional and behavioral ties with rural environments [8].

Within rural studies, the framework has been applied to understand how individuals form place attachment, emotional bonds, and behavioral intentions toward rural areas [9,10]. Yet, research on youth engagement in rural revitalization often examines isolated variables rather than modeling the full CAB pathway [4]. Recent years have seen a growing rise in immersive VR applications in rural development, landscape perception, and environmental education [11,12]. These studies show that VR can enhance perceptual engagement with rural spaces, strengthen emotional connectedness, and reduce urban–rural psychological distance among young people. VR also facilitates pro-environmental attitudes, spatial learning, and place-based engagement by providing multisensory and embodied experiences that traditional media formats cannot offer. Despite these advances, studies examining youth responses to rural environments still commonly rely on traditional media formats such as photographs, static videos, or desktop panoramas, which offer limited interactivity and immersion [13]. Immersive VR provides stronger presence and engagement, making rural spaces more perceptually accessible to urban youth [14].

However, much of the recent VR literature remains outcome-oriented and does not unpack the cognitive–affective mechanisms through which VR shapes rural engagement. VR is often conceptualized as an affective stimulus rather than examined as a cognitive trigger within structured behavioral models [15,16]. Few studies explore how immersive technologies interact with environmental perceptions to influence behavioral responses through restorative experience, place identity (PI), or nature connectedness [17,18,19]. Although VR has also been shown to foster pro-environmental norms and behavioral change through emotional and cognitive engagement [20], these findings remain fragmented and under-theorized in youth-focused rural revitalization contexts [4]. To address this, the present study incorporated immersive VR as a cognitive component within a CAB-based serial mediation model, integrating perceived sensory dimensions (PSD), restorative experiences (RE), and PI to explore how virtual rural environments influence behavioral intentions.

The CAB framework also suggests that pathways may vary across demographic groups. Prior research suggests that gender, urban–rural identity, and rural living experience significantly shape perceptions of rurality, emotional attachment, and PI [4,21]. Additionally, users’ demographic characteristics can influence their sensitivity to immersive digital technologies, affecting presence, empathy, and behavioral motivation [18]. Therefore, understanding of subgroup heterogeneity is crucial for tailoring youth engagement strategies to the needs of different demographic groups may help bridge psychological and social divides and enhance youth participation in rural development [9].

Building on the CAB framework, this study conceptualizes “cognition” as comprising PSD and immersive VR experience, “affect” as involving RE and PI, and “behavior” as represented by rural visit intention (RVI) and environmentally responsible behavioral intention (ERBI) [9]. These two behavioral intentions represent complementary aspects of youth engagement in rural revitalization. RVI signals youths’ willingness to re-enter rural environments, not only as visitors but also as participants in social, educational, or professional activities, indicating potential talent return. ERBI reflects the value-driven side of engagement, showing willingness to assume responsibility for sustainable rural development.

Thus, this study aims to examine how immersive virtual rural environments influence youths’ behavioral intentions through restorative and identity-based mechanisms; identify psychological heterogeneity across gender, household registration, and rural living experience using multigroup analysis (MGA); and provide insights for digitally supported rural education and revitalization policies. A serial mediation model based on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) is employed to assess indirect effects and subgroup differences [22].

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews relevant theories, including attention restoration theory (ART), stress reduction theory (SRT), and the CAB framework, and integrates them to develop this study’s conceptual model. Section 3 describes the experimental design and VR setup, along with the PLS-SEM and MGA methods. Section 4 presents the empirical results, and Section 5 discusses the theoretical contributions, practical implications, and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Theories Background on Restorative Environment

Restorative environment theories, namely, ART and SRT, provide complementary explanations for how natural environments facilitate psychological recovery. ART emphasizes the role of environmental features such as being away, fascination, extent, and compatibility in restoring attentional capacity [23,24], whereas SRT highlights unconscious physiological and emotional responses that promote short-term stress relief [19,25]. Although originating from different theoretical traditions, ART and SRT together clarify how perceived sensory dimensions contribute to restorative experience. ART explains the cognitive pathway, in which PSD elements such as coherence, soft fascination, and extent help replenish directed attention. SRT complements this by describing an affective pathway, where serene, refuge-like, or nature-rich cues evoke stress reduction and positive emotional responses. Thus, PSD influences RE through both attentional recovery and emotional restoration, offering a more integrated understanding of why restorative outcomes arise in rural environments. Rural environments often align more closely with these restorative features due to their ecological richness and compatibility with human psychological needs [26,27].

2.2. PSD and RE

The PSD framework was originally developed by Grahn and Stigsdotter [28] to describe landscape characteristics that support psychological restoration. It comprises eight dimensions: serene, nature, rich in species, space, refuge, prospect, culture, and social. As a key component of the cognition stage in the CAB framework, PSD reflects individuals’ perceptual appraisal of environmental stimuli, which initiates the affective and behavioral responses that follow.

To ensure both theoretical coherence and statistical parsimony, this study selected four of the eight PSDs: refuge, nature, serene, and rich in species. These dimensions have been empirically shown to be most strongly associated with psychological restoration. In a controlled experimental setting, they received the highest restoration ratings among all PSDs [29]. Grahn and Stigsdotter [28] found that nature and refugees were highly correlated with stress reduction, while Yakınlar and Akpınar [30] further confirmed their contributions to adults’ mental well-being.

Previous studies have established robust theoretical and empirical connections between PSDs and REs. Thus, based on robust empirical evidence linking PSDs to REs and theoretical arguments concerning dimensional redundancy [29], this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H1:

In immersive rural VR environments, PSDs positively influence university students’ restorative experiences.

2.3. RE and PI

Both RE and PI jointly form the affect stage in the CAB framework, mediating how environmental perception is internalized emotionally before driving behavioral intentions. RE, defined as psychological recovery from mental fatigue and stress, allows individuals to mentally detach themselves from routine concerns [24]. REs were measured using three items adapted from previous research on mental restoration in VR environments [31].

PI refers to the emotional and symbolic connections that individuals form in specific environments, including feelings of attachment, belonging, and pride [9]. It is typically distinguished from place dependence, which reflects functional reliance on a place’s resources. As Tešin et al. [10] explain, PI captures symbolic and affective ties, whereas place dependence emphasizes practical utility and irreplaceability. For university students who briefly experience rural settings through VR, emotional identification is more likely to emerge than functional dependence. Therefore, the present study focused on PI as the key affective mechanism linking REs to behavioral intentions. Previous research has consistently found that significant REs, even within virtual settings, enhance individuals’ PI [27]. Thus:

H2:

REs positively influence PI among university students in immersive rural VR environments.

2.4. VR Presence: Its Role in Enhancing RE and PI

While environmental features shape RE and PI, engagement is also influenced by how individuals interact with their surroundings. VR strengthens engagement by creating a heightened sense of presence, reducing psychological distance, intensifying emotional resonance, and motivating pro-rural intentions [14,32]. Traditional media formats such as photographs, static videos, or desktop-based panoramas have long been used to represent rural environments, but they lack interactivity and immersion, resulting in weaker spatial presence and emotional resonance [13]. Empirical studies show that VR head-mounted displays significantly enhance feelings of presence and autonomy, allowing users to explore and engage with virtual spaces as if physically present. This embodied experience reduces urban–rural psychological distance and evokes stronger cognitive engagement and affective responses [14].

VR presence refers to a user’s subjective sense of “being there” in a virtual environment; it typically comprises two dimensions: self-location (which describes the feeling of being physically situated within a mediated environment) and possible actions (which reflect the user’s perceived ability to interact within the virtual setting) [33]. In this study, self-location scores were uniformly high, with limited variance, which reduced their analytical value. Conversely, possible actions varied substantially across participants [18]. Therefore, we measured VR presence using only the possible actions dimension. In immersive VR settings, the possible actions cue allows users to mentally simulate how they might move or interact within the rural environment. This imagined engagement enhances their perceived ability to participate in the scene, fostering emotional connectedness and contributing to the development of place identity [9].

Evidence shows that VR effectively enhances restorative experiences by improving attention focus and psychological detachment [32]. Studies such as Luo et al. [31] further confirm that immersive VR scenes produce greater attention restoration and higher presence compared to non-immersive formats. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3:

In immersive rural VR environments, VR presence (possible actions) positively influences REs among university students.

Beyond its restorative function, VR facilitates the development of PI. When users perceive a high degree of possibility of action, they tend to engage more emotionally and symbolically with the environment, thereby fostering a sense of belonging and identification [31]. Hence:

H4:

In immersive rural VR environments, VR presence (possible actions) positively influences PI among university students.

2.5. RVI and ERBI

We examined two distinct types of behavioral intentions. RVI aligns with the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), which posits that behavioral intention is shaped by attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control [34]. In the rural revitalization context, RVI reflects youths’ willingness to re-engage with rural areas not only as tourists, but also through social practice, volunteer service, employment, and entrepreneurship. Such participation serves as an early indicator of potential talent return and sustained integration into rural communities [35].

ERBI resonates with the Value–Belief–Norm (VBN) theory, which emphasizes that pro-environmental behaviors are driven by values, ecological beliefs, and moral obligations [36]. In rural settings, ERBI captures the responsibility-driven dimension of youth engagement, reflecting their commitment to rural ecological stewardship and community sustainability [37,38].

Together, these two intentions provide a comprehensive framework for evaluating youth engagement. RVI emphasizes the participatory dimension, while ERBI underscores the responsibility dimension—both essential for advancing rural revitalization goals and bridging the urban–rural divide.

2.6. PI and Behavioral Intentions

Behavioral intention is a critical antecedent of actual behavior [39]. PI reinforces the motivation to return to or explore a place, as strong self–place connections cultivate curiosity and commitment [40]. Empirical studies confirm that PI, particularly when enhanced through immersive VR, significantly increases visit intention [16]. In the context of rural revitalization, university students’ intention to visit rural areas represents not only a form of psychological connection but also a potential source of human capital and creative engagement in rural development efforts [3]. Thus. The following hypothesis is proposed:

H5:

In immersive rural VR environments, PI positively influences rural visit intentions among university students.

PI enhances ERBI by fostering emotional attachment, moral obligation, and alignment with place values. Individuals who perceive the rural environment as part of their self-identity are more likely to engage in behaviors that protect and preserve it [41]. When individuals integrate a location into their self-concept, they exhibit greater concern for and willingness to protect their environment [42]. This is particularly relevant to rural revitalization goals, in which cultivating youth environmental stewardship is essential for sustaining rural landscapes’ ecological and cultural integrity. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H6:

In immersive rural VR environments, PI positively influences ERBI among university students.

RVI and ERBI represent the behavior stage in the CAB framework, capturing downstream expressions of prior cognitive and affective processes.

2.7. Conceptual Framework

This study proposes a serial mediation model [43], in which two perceptual antecedents, PSD and VR presence, shape participants’ behavioral intentions through the dual mediators of RE and PI. PSD reflects sensory perceptions of the rural landscape, whereas VR presence captures participants’ perceived interactive immersion in a virtual rural environment [18,33].

The PSD construct was modeled as a reflective–formative higher-order construct composed of four reflective first-order dimensions: serene, nature, refuge, and rich in species. Following Hair et al. [22], the repeated-indicators approach was employed to estimate the formative relationships among the dimensions and the second-order construct.

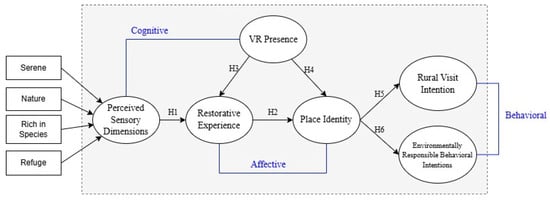

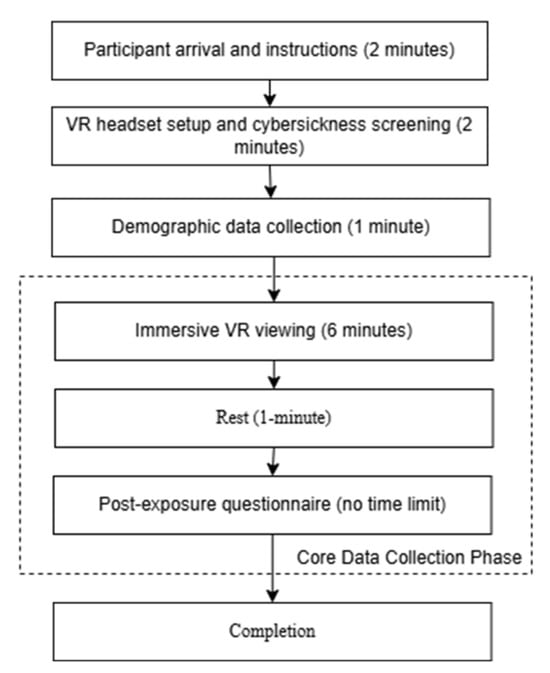

This structure reflects a psychological transition from environmental perception to affective identification and, ultimately, behavioral motivation. To explore whether these mediation paths differ across individual characteristics such as gender, household registration type, and rural living experience, this study also incorporated a multigroup comparison logic into the framework, aligning with recent calls to account for subgroup heterogeneity in environmental psychology [9,41]. Figure 1 illustrates the hypothesized serial mediation model, which allows for empirical validation of the sequential mechanisms proposed by the CAB framework, enhancing our understanding of how digital immersion translates into pro-rural behavioral responses.

Figure 1.

Proposed serial mediation model and hypotheses.

3. Research Methods

3.1. Participants and Data Collection

This study investigated how VR-based rural landscape experiences influence university students’ behavioral intentions and environmental responsibility. Undergraduate students were selected as the target group, given their formative stage of value development and high potential for long-term environmental engagement [18]. The formal experiment was conducted at Laboratory 301 of the Art Building at Wuhan University of Bioengineering.

A total of 220 undergraduate students aged 18–22 years were recruited through campus advertisements. The sample exhibited approximately equal gender distribution and diverse academic backgrounds. All the participants reported normal or corrected-to-normal vision, unimpaired color perception, and intact hearing. To minimize physiological confounding variables, participants were instructed to maintain regular sleep patterns and avoid alcohol consumption or sleep deprivation for three days prior to the experiment.

A pre-test involving 12 additional students was conducted to refine the experimental procedures. This included adjustments to the VR headset for optimal fit, audio-visual calibration, and refinement of the questionnaire item wording.

The participants completed a brief demographic questionnaire before the VR experience. The questionnaire covered gender, household registration (hukou), and rural living experiences. In the context of China’s household registration system, participants were classified as having either an agricultural or non-agricultural hukou, indicating rural or urban residency, respectively. Rural living experience was categorized as either “no or short-term” (less than one month cumulatively) or “long-term” (one month or more). It is noteworthy that over 70% of the participants held an agricultural household registration (hukou). This is attributable to the university’s student recruitment patterns, as a substantial portion of the student body comes from predominantly rural regions such as Enshi city in Hubei Province.

After excluding 11 incomplete or invalid responses, 209 valid questionnaires were retained for the analysis, resulting in a final response rate of 95%. A priori power analysis using G*Power 3.1 (effect size f2 = 0.15, α = 0.05, power = 0.95, 2 predictors) indicated a minimum sample size of 107. Our final sample of 209 participants thus exceeds this requirement. All the participants provided written informed consent and were informed of their right to withdraw at any stage without penalty. Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review board of Wuhan University of Bioengineering (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participants’ demographic characteristics (N = 209).

3.2. VR Rural Scenario Development and Implementation

To create an authentic and immersive rural experience, a continuous six-minute 180° panoramic video was recorded across a chain of natural and cultural scenes in Hubei Province, using an Insta360 Pro 2 camera (Arashi Vision Inc., Shenzhen, China). Ambisonic audio was captured to synchronize environmental sounds, including birdsongs, wind, flowing water, and night-time village ambience, thus enhancing spatial and emotional immersion [17].

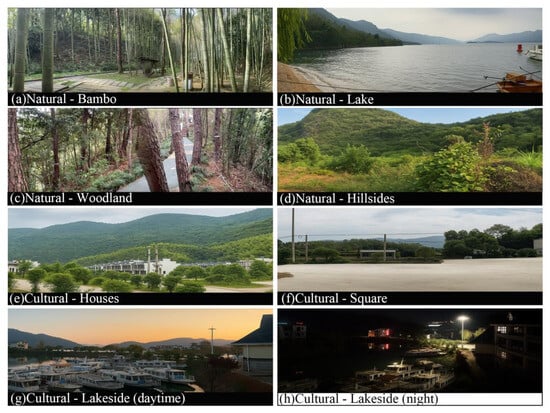

The video followed a narrative sequence ranging from natural to cultural elements. It opened with scenes of bamboo forests, lakes, woodland paths, and earthen hills, which are features associated with a high restorative potential [24]. It then transitioned into culturally rural scenes such as newly built hillside houses, village squares, and lakeside residential areas with moored boats. The sequence concluded with a nighttime panorama, contrasting day and night atmospheres, and emphasizing the temporal dynamics of rural life.

This spatiotemporal narrative aimed to portray the rural environment as a dynamic lived space rather than a static backdrop, thereby enhancing attentional engagement and facilitating affective and cognitive immersion [24,44]. Figure 2 shows excerpts selected from the VR scenario.

Figure 2.

Proposed serial mediation model and hypotheses. Representative Rural Scenes Included in the VR Experience: (a–d) Natural environments; (e–h) Cultural environments.

The final video was edited and stabilized using Adobe Premiere Pro 2023 (Adobe Inc., San Jose, CA, USA), and uploaded to PICO 4 Ultra headsets (Pico Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). Before exposure to the rural scene, participants watched a two-minute neutral urban VR clip to screen for cybersickness. Those without symptoms proceeded to the full six-minute rural VR experience. During the session, the participants were encouraged to freely explore the environment using head movement. Following a brief one-minute rest, the participants completed a post-exposure questionnaire on their smartphones. Appendix A shows the headset used and formal experimental sequence.

3.3. Measurements

The questionnaire consists of six latent constructs, each measured using validated multi-item scales. All items are rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Table 2 presents an overview of the constructs, sources, and sample items. The measurement items were adapted from previously validated scales in environmental psychology and VR research literature to ensure reliability and validity.

Table 2.

Summary of Constructs and Representative Measurement Items.

3.4. Data Analysis Approach

PLS-SEM was applied using SmartPLS 4.0 software to estimate the proposed CAB-based mediation model. This method is particularly suitable for theory development involving complex models, hierarchical constructs, and non-normal data distributions [45,46].

The PSD construct was modeled as a reflective–formative second-order construct composed of four reflective dimensions (serene, nature, refuge, and rich in species) and estimated using the repeated indicators approach [22].

The model evaluation followed a two-step approach. The measurement model was assessed for internal consistency, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. Second, the structural model was tested using bootstrapping with 5000 re-samples to examine the significance of the direct and indirect effects, including serial mediation paths [43].

To explore subgroup heterogeneity, bootstrap-based MGA was conducted across sex, household registration type, and rural living experience. Compared with the permutation test, the bootstrap MGA is more flexible and does not require strict measurement invariance, which makes it suitable for exploratory subgroup comparisons with moderate sample sizes [45,47,48]. This procedure allowed for the identification of potential differences in CAB pathways across subpopulations.

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Analysis

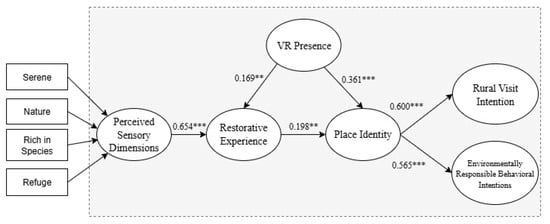

The analysis followed a two-step procedure: evaluation of the measurement model and structural model testing. Reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha (α ≥ 0.70) and composite reliability (CR ≥ 0.70 and <0.95). Convergent validity was verified by average variance extracted (AVE ≥ 0.50), and indicator loadings (loadings ≥ 0.708) were examined for all constructs [22]. Table 3 reports the factor loadings, Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability, and AVE values for each construct, confirming satisfactory reliability and convergent validity. Discriminant validity was assessed using the heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT < 0.90). As shown in Table 4, all the HTMT values fell below the recommended threshold, indicating acceptable discriminant validity (Figure 3).

Table 3.

Data of the Measurement Model.

Table 4.

HTMT Ratio.

Figure 3.

Structural Model with Standardized Path Coefficients and Significance Levels. ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

4.2. Structural Model and Predictive Assessment

A structural model was evaluated to test the hypothesized relationships between the constructs. As shown in Table 5, all six hypothesized direct paths were statistically significant, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) excluding zero. Specifically, PSD significantly predicted RE (β = 0.654, 95% CI [0.569, 0.731], p < 0.001), supporting H1. RE significantly influenced PI (β = 0.198, 95% CI [0.083, 0.311], p = 0.001), thus supporting H2. VR presence was a significant predictor of both RE (β = 0.169, 95% CI [0.068, 0.271], p = 0.001; H3) and PI (β = 0.361, 95% CI [0.236, 0.487], p < 0.001; H4). Furthermore, PI positively predicted both RVI (β = 0.600, 95% CI [0.476, 0.704], p < 0.001; H5) and ERBI (β = 0.565, 95% CI [0.482, 0.652], p < 0.001; H6). All variance inflation factor values were below 3.3, indicating no multicollinearity issues [45]. A PLS prediction procedure was applied to further assess the model’s predictive relevance [49]. As reported in Table 6, the Q2_ predicted values for all four endogenous constructs were positive, confirming that the model performed better than the naïve benchmark (e.g., mean-based prediction). Notably, RE (Q2 = 0.493) demonstrated strong predictive relevance, followed by PI (Q2 = 0.182), with acceptable values for both behavioral intention constructs. These results support the model’s practical utility in predicting psychological and behavioral responses to immersive VR experiences in rural areas.

Table 5.

Result of the Structural Model.

Table 6.

PLS predict LV Summary.

4.3. Serial Mediation Effects of RE and PI

Bias-corrected bootstrapping with 5000 resamples was employed [22]. As shown in Table 7, all the hypothesized indirect effects were statistically significant. Specifically, PSD exerted significant serial mediation effects on both RVI (indirect effect = 0.078, p = 0.001; 95% CI = [0.032, 0.128]) and ERBI (indirect effect = 0.073, p = 0.001; 95% CI = [0.031, 0.120]) through the sequential mediators of RE and PI. These results suggest that participants’ sensory impressions of the rural environment indirectly fostered behavioral intentions via a dual-stage cognitive–affective mechanism.

Table 7.

Result of Specific Indirect and Mediating Effects.

Similarly, VR presence, representing the users’ perceived ability to act in an immersive environment, also demonstrated multiple indirect pathways. The full sequential mediation paths were statistically significant but showed smaller effect sizes: VR → RE → PI → RVI (indirect effect = 0.020, p = 0.034; 95% CI = [0.005, 0.042]), and VR → RE → PI → ERBI (indirect effect = 0.019, p = 0.035; 95% CI = [0.004, 0.040]). In contrast, simpler mediation chains via PI alone demonstrated stronger indirect effects: VR → PI → RVI (indirect effect = 0.217, p < 0.001; 95% CI = [0.139, 0.308]), and VR → PI → ERBI (indirect effect = 0.204, p < 0.001; 95% CI = [0.134, 0.282]).

This pattern is consistent with prior findings that the attenuation of serial mediation is common because of the multiplicative nature of path coefficients over longer causal chains [48,50]. One plausible explanation lies in VR presence’s possible actions dimension, which enhances perceived agency and control within the scene. This psychological cue may facilitate symbolic identification and emotional belonging to the virtual rural space, which are hallmarks of PI, even without prior mental restoration [33,51]. Essentially, immersive interactivity alone may be sufficient to elicit a sense of belonging, thereby promoting pro-environmental behavioral intentions.

The co-existence of significant direct and indirect effects in the same direction suggests complementary mediation, confirming that both restorative and identity-based processes are crucial psychological pathways through which sensory and technological cues shape behavioral responses [43].

4.4. Bootstrap MGA

To examine whether the structural model relationships varied across demographic subgroups, bootstrap-based MGA was conducted using SmartPLS 4 software [45]. As shown in Table 8, most path differences across gender, household registration type, and rural living experience were not statistically significant (p > 0.05, two-tailed), suggesting general consistency in the structural mechanism across groups.

Table 8.

MGA Summary.

However, several significant differences were observed among groups. First, the RE → PI pathway was significantly stronger among female participants (p = 0.033). Second, the VR presence → PI pathway differed significantly across household registration types (p = 0.044), with a stronger effect observed in the non-agricultural group. Third, the same path (VR → PI) showed a significant difference based on rural living experience (p = 0.038), with short-term rural residents showing a stronger effect.

These findings suggest that while the overall model structure remains consistent, certain psychological pathways may vary depending on the demographic background, warranting further interpretation in Section 5.

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary of the Findings

This study investigated how immersive VR rural environments influence university students’ RVI and ERBI through cognitive and affective mechanisms, guided by the CAB framework [8,9,52]. Two distinct types of cognitive antecedents were modeled: environmental appraisal (PSD), which reflects students’ subjective evaluation of scene attributes, and mediated experiential cognition (VR presence), which captures the psychological sense of immersion and interactivity. All six hypothesized direct paths were supported. Both restorative and identity-based mechanisms significantly mediated behavioral intentions. Among the two mediators, PI demonstrated a more substantial effect, particularly among students with limited rural experience. Notably, VR presence was able to directly foster place identity—independent of prior restorative experience—while PSD only influenced place identity indirectly through RE [18,27]. This finding underscores the distinctive theoretical role of immersive VR as both a cognitive and affective stimulus, exceeding the capacity of traditional media. It expands the scope of digital interventions within environmental psychology, demonstrating how immersive technologies can extend place-based engagement beyond conventional communication approaches. Meanwhile, MGA revealed partial heterogeneity: Female participants exhibited stronger RE → PI effects [53], whereas students with urban hukou or short-term rural exposure showed increased sensitivity to the impact of VR presence [15,54]. These subgroup patterns may be partly explained by differences in familiarity and perceived psychological distance. Individuals with lower prior exposure to rural environments often experience heightened novelty, stronger contrast effects, and more pronounced emotional reactions when encountering rural scenes in VR. Such amplified affective and cognitive responses can strengthen restorative experience and facilitate the formation of place identity, aligning with psychological distance theory and prior findings on immersive environmental engagement. These findings highlight the importance of designing targeted interventions to address psychological differences across youth segments [43].

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

This study advances environmental psychology by empirically validating an extended CAB framework in immersive rural environments [8,9]. By embedding ART and SRT into digitally simulated natural environments, this study demonstrates that both cognitive (sensory perception and presence) and affective (restoration and identity) processes are critical for shaping behavioral intentions [24,25]. Importantly, the results highlight that higher levels of immersive presence are associated with stronger symbolic and emotional attachment in virtual rural environments, emphasizing the symbolic and emotional attachment formed through interactivity [33,51]. This finding suggests a complementary pathway to classic environmental psychology models, indicating that the influence of immersive presence on place identity is not fully mediated by restorative experience; rather, in addition to the pathway through cognitive restoration, there exists a parallel direct effect from VR presence to symbolic and emotional attachment. Unlike traditional media, which primarily rely on passive exposure, VR interventions create a sense of spatial autonomy and psychological “being there.” This autonomy not only strengthens emotional attachment but also enables users to experience and rehearse real-world behaviors within a controlled, risk-free environment. Thus, this study contributes by empirically validating an interaction-driven mechanism of place attachment in digital environments, highlighting that beyond visual restoration, the sense of agency enabled by virtual operability is vital to understanding modern human–place relationships. Moreover, this study refines the application of the CAB framework by situating it within youth-centered rural revitalization discourse and virtual environmental exposure, areas where prior research has often overlooked affective mediators in VR settings [15,18]. The inclusion of MGA also responds to calls to recognize heterogeneity in environmental behavior models, providing a differentiated understanding of how immersive design influences diverse youth populations [53,54]. By distinguishing participatory RVI and ERBI, this study advances a multidimensional view of youth engagement in rural contexts. The dual-path approach, grounded in the TPB and VBN Theory, shows that immersive VR can activate both practical and normative drivers of pro-rural behavior. This refinement supports more nuanced environmental behavior models and offers actionable insights for environmental psychology and policy design.

5.3. Practical Implications: Enhancing Policy–Education Synergy

This study addresses national concerns over youth disengagement from rural revitalization, despite policies such as One Village, One University Student [1,2]. By activating cognitive and affective mechanisms, immersive rural VR can reduce psychological distance, strengthen symbolic connections with rural places, and foster visits and environmental responsibility intentions among students. In university education, VR offers clear advantages over both traditional media and on-site teaching: compared to conventional materials, it provides stronger immersion and engagement; compared to field visits, it avoids the logistical, cost, and safety constraints often associated with organizing on-site rural teaching. To align with China’s digital rural revitalization strategy [3], universities are encouraged to embed immersive VR into curricula, such as environmental psychology or service learning. These experiences can enhance pro-rural engagement, particularly when tailored to subgroup differences. Female students’ stronger RE → PI pathways suggest emphasizing restorative visuals and reflective scenes to deepen their affective involvement. Urban and non-agricultural students who are more responsive to VR presence may benefit from interactive, novel rural narratives that enhance symbolic belonging. For those with limited rural exposure, immersive storytelling paired with structured reflection can bridge familiarity gaps [15,53].

RVI can translate into youth participation through field practice, internships, volunteering, short-term work, or return entrepreneurship. These activities promote talent return, introduce new ideas and skills, stimulate rural vitality, and strengthen youth–rural ties [1,3]. ERBI reflects sustained support for rural sustainability through environmental protection, community building, resource conservation, and advocacy. This responsibility fosters long-term “return–stay–care–protect” cycles, enhancing governance and ecological stewardship [37,38]. These pathways suggest that VR education can both engage youth directly in rural life and cultivate enduring responsibility for sustainable rural development, providing evidence for policy programs that integrate digital interventions into revitalization strategies.

To maximize impact, multi-sectoral partnerships among universities, local governments, and rural communities should be fostered to integrate digital engagement platforms with real-world rural initiatives [55]. By designing demographically sensitive interventions, universities and policymakers can collaboratively foster rural consciousness and long-term behavioral engagement among youths, thereby contributing to more inclusive and psychologically grounded rural revitalization. Efforts must also be made to ensure equitable access to immersive technologies in under-resourced or remote areas, minimizing new digital divides in rural development [56]. As digital rural revitalization is promoted globally [57], lessons from this research may inform similar policy–education synergy in other countries facing youth–rural disengagement, contributing to a broader global effort in sustainable rural development. However, the potential impact of the digital divide should be considered, as unequal access to VR equipment and digital infrastructure may limit the scalability of VR-based rural engagement programs.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Despite validating the CAB-based mechanism through which immersive rural VR experiences influence behavioral intentions, this study had several limitations. First, its sample consisted of undergraduate students from a single university. Although diverse in discipline and rural-urban backgrounds, homogeneity in age and education level limits the generalizability of the findings. Second, this experiment employed a prerecorded 180° panoramic video. Although this setup offers strong sensory immersion, it lacks real-time interaction and free movement, thus potentially leading to an underestimation of VR presence’s full impact on psychological mechanisms. Future studies could include traditional 2D videos or other non-immersive formats to better isolate the specific effects of immersive VR. Future studies may further distinguish recent from childhood rural experience to capture more nuanced forms of familiarity. Third, behavioral intentions were measured using self-reported questionnaires without longitudinal tracking of actual behaviors. Future studies should incorporate objective indicators such as field visits or voluntary engagement to assess intention–behavior consistency.

Future research can extend this study in several ways. First, broader participant recruitment across regions, age groups, and educational backgrounds could enhance external validity. Second, highly interactive VR systems featuring eye tracking, haptic feedback, or room-scale movement could be introduced to examine how interactivity moderates the cognitive–affective process. Third, future research should consider including a comparison group exposed to traditional media formats, in order to more clearly differentiate the effects of immersive experiences. In addition, the underlying mechanisms behind the observed subgroup differences were not deeply explored. Future studies may use qualitative interviews to better understand these processes. Lastly, incorporating variables such as rural mental imagery or urban–rural psychological distance may enrich the explanatory power of the CAB framework and support the theoretical integration between environmental psychology and rural governance studies.

6. Conclusions

This study enriches environmental psychology by extending the CAB framework to immersive virtual rural contexts and uncovering how sensory perception and digital presence jointly foster restorative and identity-based processes. The empirical results confirm that immersive rural VR enhances both restorative experience and place identity, with the latter emerging as the key affective mechanism driving rural visit intention and environmentally responsible behavioral intention. The findings further indicate that students with limited rural exposure and certain demographic groups exhibit heightened sensitivity to VR-induced presence, suggesting meaningful variability in how different youth segments respond to immersive rural environments.

By integrating PLS-SEM and multi-group comparisons, this study offers new insights into the design of context-sensitive and demographically responsive VR interventions. These results underscore the theoretical relevance of combining perceptual appraisal, restorative processes, and identity formation within a unified CAB-based mechanism. As rural revitalization efforts increasingly intersect with digital education and engagement tools, this study provides a timely empirical foundation for leveraging immersive VR to reduce urban–rural psychological distance and promote more sustainable youth–rural connections.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.C. and R.M.; methodology, N.C. and R.M.; software, N.C.; validation, N.C. and R.M.; formal analysis, N.C.; investigation, N.C.; resources, N.C.; data curation, N.C.; writing—original draft preparation, N.C.; writing—review and editing, R.M. and K.F.; visualization, N.C.; supervision, R.M.; project administration, R.M.; funding acquisition, N.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board Wuhan University of Bioengineering (protocol code WUB202507 and 25 September 2025 of approval for studies involving humans).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank all reviewers for their valuable comments on this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A shows the headset used and formal experimental sequence.

Figure A1.

(a) VR Device (PICO 4 Ultra); (b) Participant Experiencing VR.

Figure A2.

Experimental Procedure Flowchart Illustrating Key Phases of Data Collection.

References

- Liang, Z.; Zhang, X. A Study on the Innovation and Entrepreneurship Pathways of College Students under the Strategy of Rural Revitalization in China. Adv. Soc. Behav. Res. 2024, 5, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations in China. Youth as a Conduit for Rural Revitalization; United Nations China: Beijing, China, 2022; Available online: https://china.un.org/en/194635-youths-conduit-rural-revitalization (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Zhang, R.; Yuan, Y.; Li, H.; Hu, X. Improving the Framework for Analyzing Community Resilience to Understand Rural Revitalization Pathways in China. J. Rural. Stud. 2022, 94, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; He, L.; Danniswari, D.; Furuya, K. College Students’ Perceptions of and Place Attachment to Rural Areas: Case Study of Japan and China. Youth 2023, 3, 737–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Mao, C. Disparities in Environmental Behavior from Urban–Rural Perspectives: How Socioeconomic Status Structures Influence Residents’ Environmental Actions—Based on the 2021 China General Social Survey Data. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trope, Y.; Liberman, N. Construal-Level Theory of Psychological Distance. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 117, 440–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Chamber of Commerce in China (AmCham China). Report on Rural Revitalization; AmCham China: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Breckler, S.J. Empirical Validation of Affect, Behavior, and Cognition as Distinct Components of Attitude. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 47, 1191–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining Place Attachment: A Tripartite Organizing Framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tešin, A.; Dragin, A.S.; Mijatov Ladičorbić, M.; Jovanović, T.; Zadel, Z.; Surla, T.; Košić, K.; Amezcua-Ogáyar, J.M.; Calahorro-López, A.; Kuzman, B.; et al. Quality of Life and Attachments to Rural Settlements: The Basis for Regeneration and Socio-Economic Sustainability. Land 2024, 13, 1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrió-Colas, L.; Reverté-Villarroya, S.; Castellà-Culvi, A.B.; Barberà-Roig, D.; Gas-Prades, C.; Coello-Segura, A.; Adell-Lleixà, M. Immersive Virtual Reality in Psychotherapeutic Interventions for Youth with Eating Disorders: A Pilot Study in a Rural Context. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, Q. Evaluation of the Impact of VR Rural Streetscape Enhancement on Relaxation–Arousal Responses Based on EEG. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radianti, J.; Majchrzak, T.A.; Fromm, J.; Wohlgenannt, I. A Systematic Review of Immersive Virtual Reality Applications for Higher Education: Design Elements, Lessons Learned, and Research Agenda. Comput. Educ. 2020, 147, 103778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, R.; Cramer, E.M.; Song, H. Using Virtual Reality for Tourism Marketing: A Mediating Role of Self-Presence. Soc. Sci. J. 2020, 59, 657–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel-Alonso, I.; Checa, D.; Guillen-Sanz, H.; Bustillo, A. Evaluation of the Novelty Effect in Immersive Virtual Reality Learning Experiences. Virtual Real. 2024, 28, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantelidis, C.; tom Dieck, M.C.; Jung, T.H.; Smith, P.; Miller, A. Place Attachment Theory and Virtual Reality: The Case of a Rural Tourism Destination. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 36, 3704–3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, S.S.S.; Leung, S.S.K.; Wong, J.W.C.; Lee, T.C.P.; Cartwright, S.R.; Wong, J.T.C.; Man, J.; Cheung, E.; Choi, R.P.W. Brief Repeated Virtual Nature Contact for Three Weeks Boosts University Students’ Nature Connectedness and Psychological and Physiological Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Pilot Study. Front. Public Health 2023, 10, 1057020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tussyadiah, I.P.; Wang, D.; Jung, T.H.; tom Dieck, M.C. Virtual Reality, Presence, and Attitude Change: Empirical Evidence from Tourism. Tourism Manag. 2018, 66, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. Aesthetic and Affective Response to Natural Environment. In Behavior and the Natural Environment; Altman, I., Wohlwill, J.F., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1983; Volume 6, pp. 85–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinlogel, E.P.; Schmid Mast, M.; Renier, L.A.; Bachmann, M.; Brosch, T. Immersive Virtual Reality Helps to Promote Pro-Environmental Norms, Attitudes and Behavioural Strategies. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2023, 8, 100105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, H.D. Is Out of Sight Out of Mind? Place Attachment among Rural Youth Out-Migrants. Sociol. Ruralis 2018, 58, 684–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, S. The Restorative Benefits of Nature: Toward an Integrative Framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M.F. Stress Recovery during Exposure to Natural and Urban Environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, L.; Wang, C.; Zhang, T.; Qiao, H.; Gao, Y.; Tao, Y.; Liu, J. Tourist Rural Destination Restorative Capacity: Scale Development and Validation. J. Travel Res. 2023, 64, 444–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Zhao, X.; Guo, Z. Place Perception and Restorative Experience of Recreationists in the Natural Environment of Rural Tourism. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1341956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grahn, P.; Stigsdotter, U.K. The Relation between Perceived Sensory Dimensions of Urban Green Space and Stress Restoration. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 94, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoltz, J.; Grahn, P. Perceived Sensory Dimensions: An Evidence-Based Approach to Greenspace Aesthetics. Urban For. Urban Greening 2021, 59, 126989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakınlar, N.; Akpınar, A. How Perceived Sensory Dimensions of Urban Green Spaces Are Associated with Adults’ Perceived Restoration, Stress, and Mental Health. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 72, 127572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Shi, J.; Lu, T.; Furuya, K. Sit Down and Rest: Use of Virtual Reality to Evaluate Preferences and Mental Restoration in Urban Park Pavilions. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 220, 104336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, D.; Cai, J. Virtual Reality Greenspaces: Does Level of Immersion Affect Directed Attention Restoration in VR Environments? J 2022, 5, 334–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, W.; Hartmann, T.; Böcking, S.; Vorderer, P.; Klimmt, C.; Schramm, H.; Saari, T.; Laarni, J.; Ravaja, N.; Gouveia, F.R.; et al. A Process Model of the Formation of Spatial Presence Experiences. Media Psychol. 2007, 9, 493–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiong, M.; Miao, H.; Wang, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhou, J. Impact of Perceived Rural Destinations Restorativeness on Revisit Intentions: The Neglected Post-Travel Negative Emotions. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2025, 62, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A Value–Belief–Norm Theory of Support for Social Movements: The Case of Environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, H.; Fan, J.; Lei, Z. A Literature Review and Prospects of Research on Tourists’ Environmentally Responsible Behavior. Tourism Trib. 2018, 33, 122–138. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, K.; Guo, Y.; Han, X. The Relationship between Restorative Perception, Local Attachment, and Environmental Responsible Behavior of Urban Park Recreationists. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Driver, B.L. Prediction of Leisure Participation from Behavioral, Normative, and Control Beliefs: An Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Leisure Sci. 1991, 13, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, M.C.; Hernández, B. Place Attachment: Conceptual and Empirical Questions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonge, J.; Ryan, M.M.; Moore, S.A.; Beckley, L.E. The Effect of Place Attachment on Pro-Environmental Behavioral Intentions of Visitors to Coastal Natural Area Tourist Destinations. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 730–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Ma, Y.; Lin, Y.; Lin, W.; Liu, C.; Mao, L.; Fan, S. Exploring the Mechanism of Host–Guest Value Co-Creation on Tourists’ Environmental Responsibility Behavior in Agricultural Heritage. npj Heritage Sci. 2025, 13, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G., Jr.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and Truths about Mediation Analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tveit, M.; Ode, Å.; Fry, G. Key Concepts in a Framework for Analysing Visual Landscape Character. Landscape Res. 2006, 31, 229–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tenenhaus, M.; Vinzi, V.E.; Chatelin, Y.-M.; Lauro, C. PLS Path Modeling. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2005, 48, 159–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The Use of Partial Least Squares Path Modeling in International Marketing. In Advances in International Marketing; Ghauri, P.N., Sinkovics, R.R., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2009; Volume 20, pp. 277–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M. Multigroup Analysis in Partial Least Squares (PLS) Path Modeling: Alternative Methods and Empirical Results. In Advances in International Marketing; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2011; Volume 22, pp. 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G.; Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Cheah, J.-H.; Ting, H.; Vaithilingam, S.; Ringle, C.M. Predictive Model Assessment in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for Using PLSpredict. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 2322–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and Resampling Strategies for Assessing and Comparing Indirect Effects in Multiple Mediator Models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.J.; Bailenson, J.N. How Immersive Is Enough? A Meta-Analysis of the Effect of Immersive Technology on User Presence. Media Psychol. 2016, 19, 272–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpela, K.M.; Ylén, M.; Tyrväinen, L.; Silvennoinen, H. Favorite Green, Waterside and Urban Environments, Restorative Experiences and Perceived Health in Finland. Health Promot. Int. 2010, 25, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scopelliti, M.; Giuliani, M.V. Choosing Restorative Environments across the Lifespan: A Matter of Place Experience. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Khan, A.; Hsu, C.-W.; Chen, S.-C. Unveiling the Key Determinants and Consequences of Virtual Reality Immersion: Embodiment and Media Novelty Effects. Manag. Mark. 2024, 19, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Q.; Yao, W. Digital Governance and Its Benchmarking College Talent Training under the Rural Revitalization in China—A Case Study of Yixian County (China). Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 984427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Yang, H. From Digital Divide to Social Inclusion: A Tale of Mobile Platform Empowerment in Rural Areas. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, F. Rural Revitalization Driven by Digital Infrastructure: Mechanisms and Empirical Verification. J. Digit. Econ. 2024, 3, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).