Green Transformation of China’s Light Industry: Regulatory and Innovation Policy Scenarios, 2023–2036

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.2. Methodology

2.3. Variable Selection

2.4. Determination of System Boundaries

2.5. Research Hypothesis

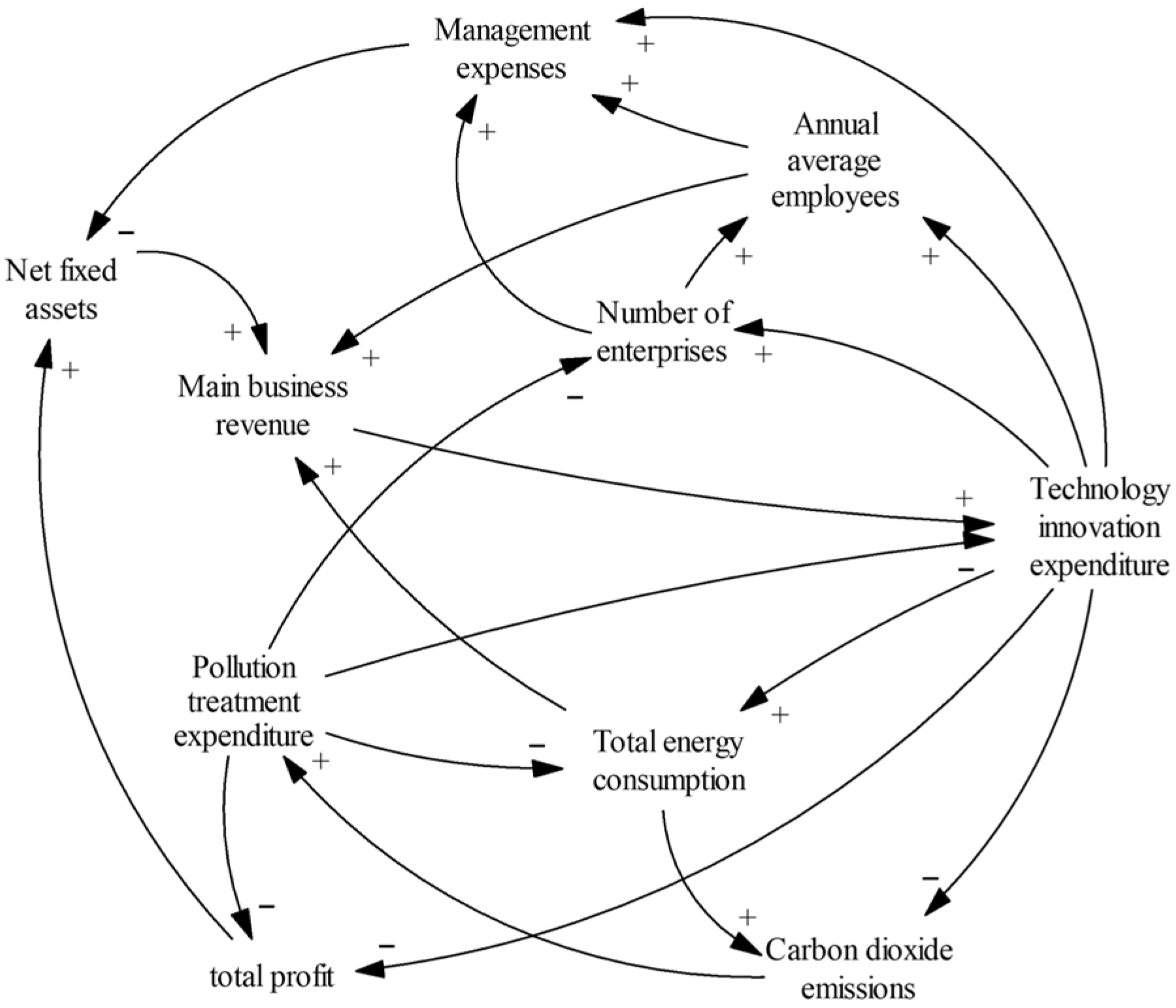

2.6. Causality Analysis

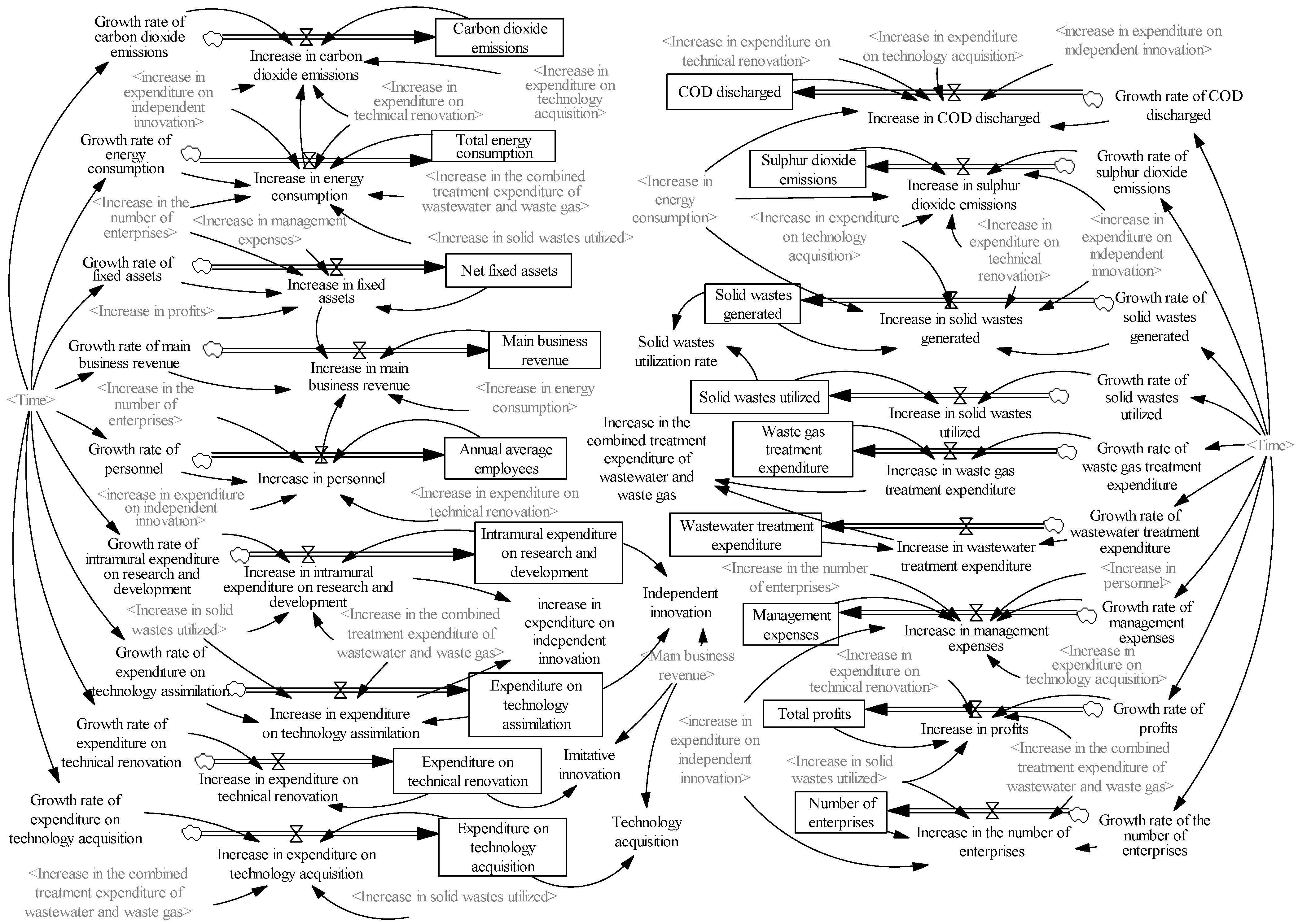

2.7. Establishment of System Flow Diagram

2.8. Design of Model Equations

- (1)

- Carbon dioxide emissions = INTEG (Increase in carbon dioxide emissions, 1466.795), unit: ten thousand tons.

- (2)

- Total energy consumption = INTEG (Increase in energy consumption, 1190.920), unit: ten thousand tons of standard coal.

- (3)

- Net fixed assets = INTEG (Increase in fixed assets, 1091.938), unit: billion yuan.

- (4)

- Main business revenue = INTEG (Increase in main business revenue, 3154.210), unit: billion yuan.

- (5)

- Annual average employees = INTEG (Increase in personnel, 144.313), unit: ten thousand people.

- (6)

- COD discharged = INTEG (Increase in COD discharged, 19.488), unit: ten thousand tons.

- (7)

- Sulphur dioxide emissions = INTEG (Increase in sulphur dioxide emissions, 8.831), unit: ten thousand tons.

- (8)

- Solid wastes generated = INTEG (Increase in solid wastes generated, 331.563), unit: ten thousand tons.

- (9)

- Wastewater treatment expenditure = INTEG (Increase in wastewater treatment expenditure, 5.277), unit: billion yuan.

- (10)

- Waste gas treatment expenditure = INTEG (Increase in waste gas treatment expenditure, 2.055), unit: billion yuan.

- (11)

- Increase in the combined treatment expenditure of wastewater and waste gas = Increase in wastewater treatment expenditure + Increase in waste gas treatment expenditure, unit: billion yuan.

- (12)

- Solid wastes utilized = INTEG (Increase in solid wastes utilized, 299.188), unit: 10,000 tons.

- (13)

- Solid wastes utilization rate = Solid wastes utilized ÷ Solid wastes generated, unit: %.

- (14)

- Intramural expenditure on R&D = INTEG (Increase in intramural expenditure on R&D, 26.428), unit: billion yuan.

- (15)

- Expenditure on technical renovation = INTEG (Expenditure on technical renovation, 30.785), unit: billion yuan.

- (16)

- Expenditure on technology acquisition = INTEG (Increase in expenditure on technology acquisition, 4.364), unit: billion yuan.

- (17)

- Expenditure on technology assimilation = INTEG (Increase in expenditure on technology assimilation, 0.685), unit: billion yuan.

- (18)

- Independent innovation = (Intramural expenditure on R&D + Expenditure on technology assimilation) ÷ Main business revenue, unit: %.

- (19)

- Imitative innovation = Expenditure on technical renovation ÷ Main business revenue, unit: %.

- (20)

- Technology acquisition = Expenditure on technology acquisition ÷ Main business revenue, unit: %.

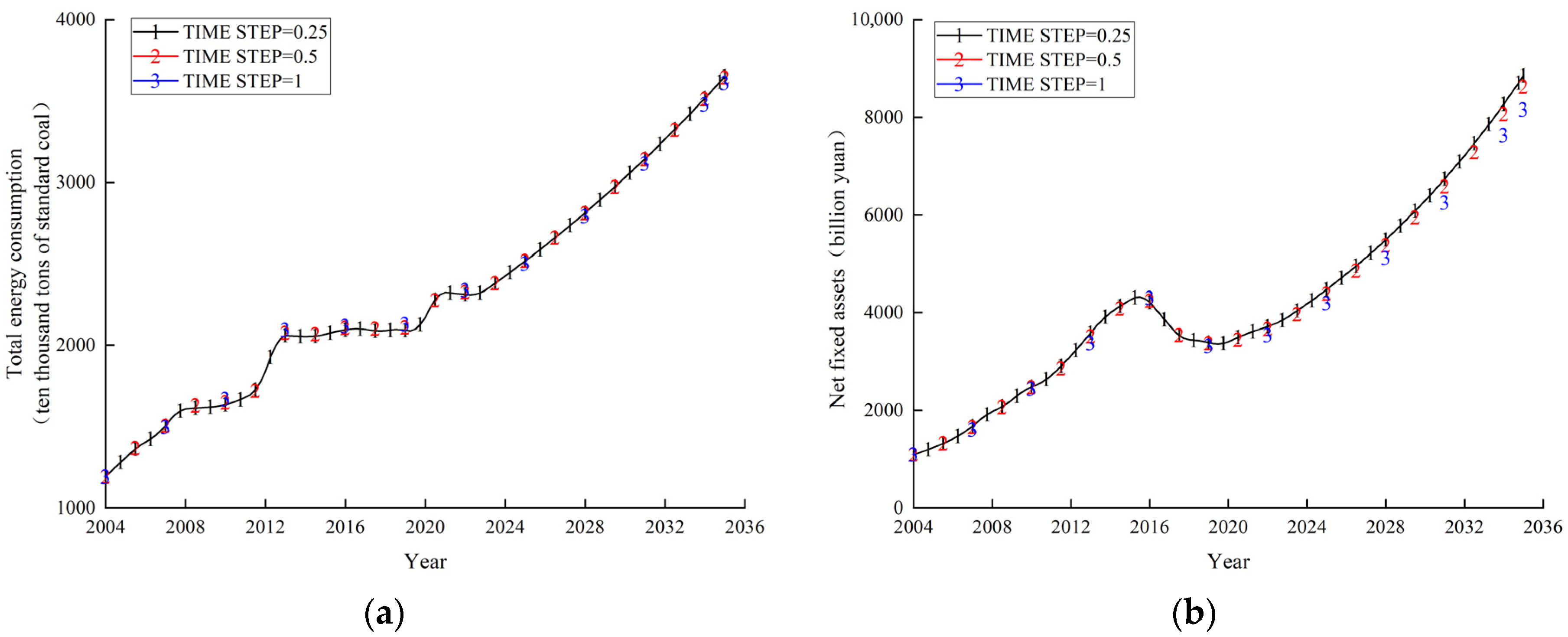

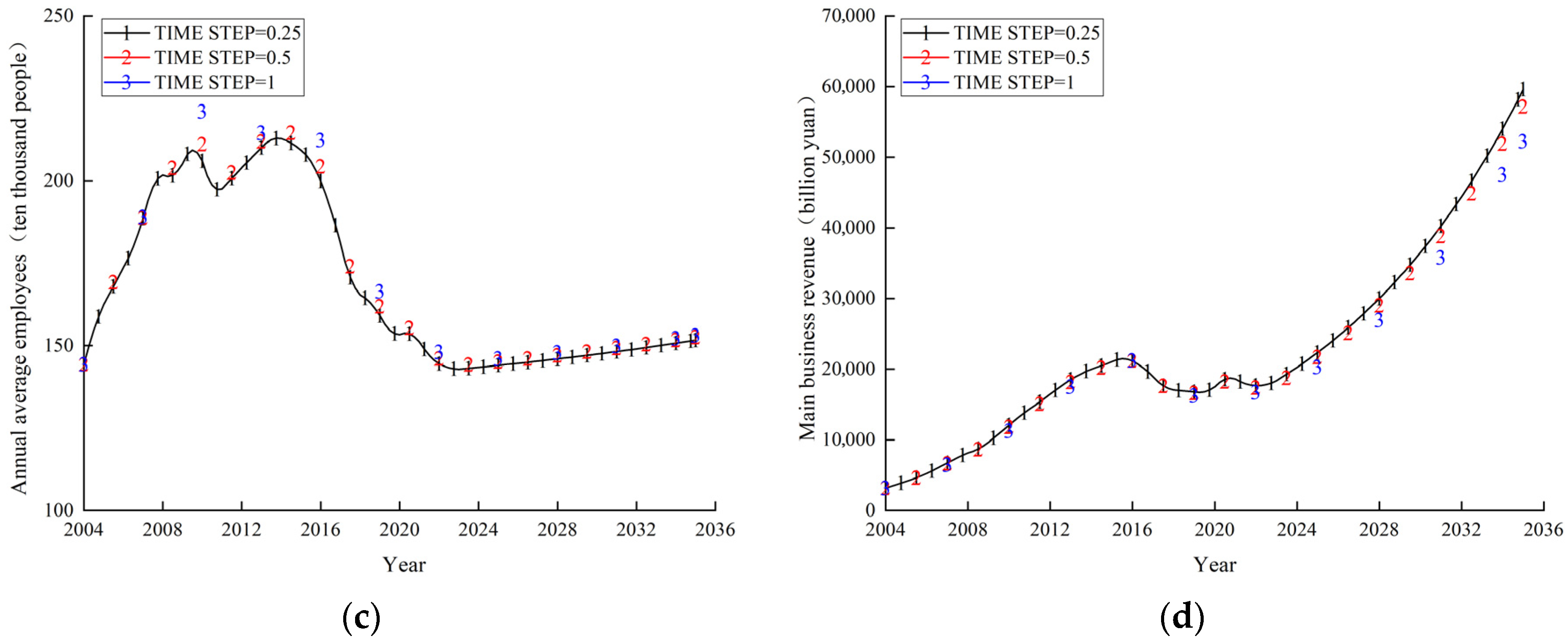

2.9. Model Validation

2.9.1. Stability Validation

2.9.2. Historical Validation

2.9.3. Sensitivity Analysis

- (1)

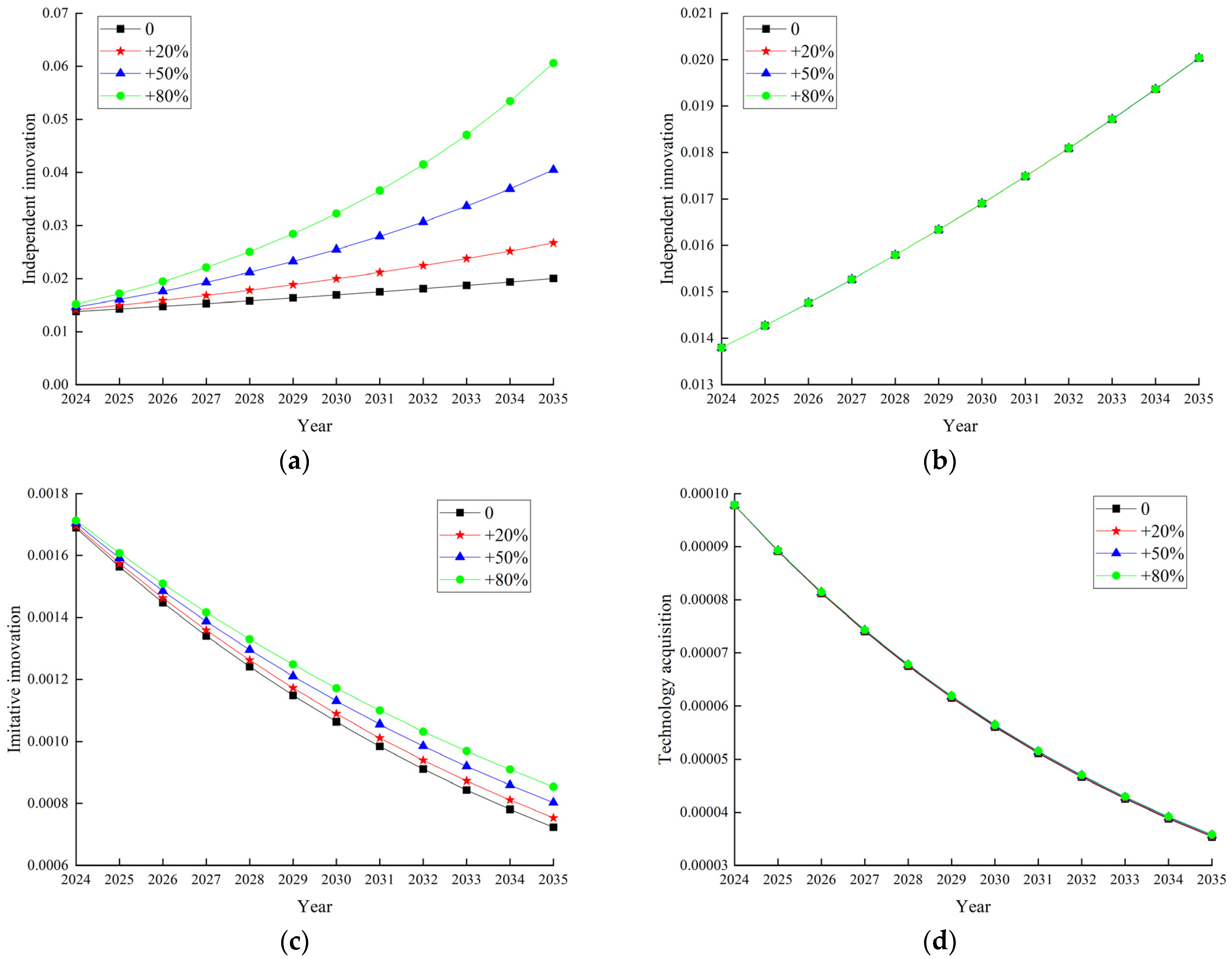

- Sensitivity analysis of technological innovation

- (2)

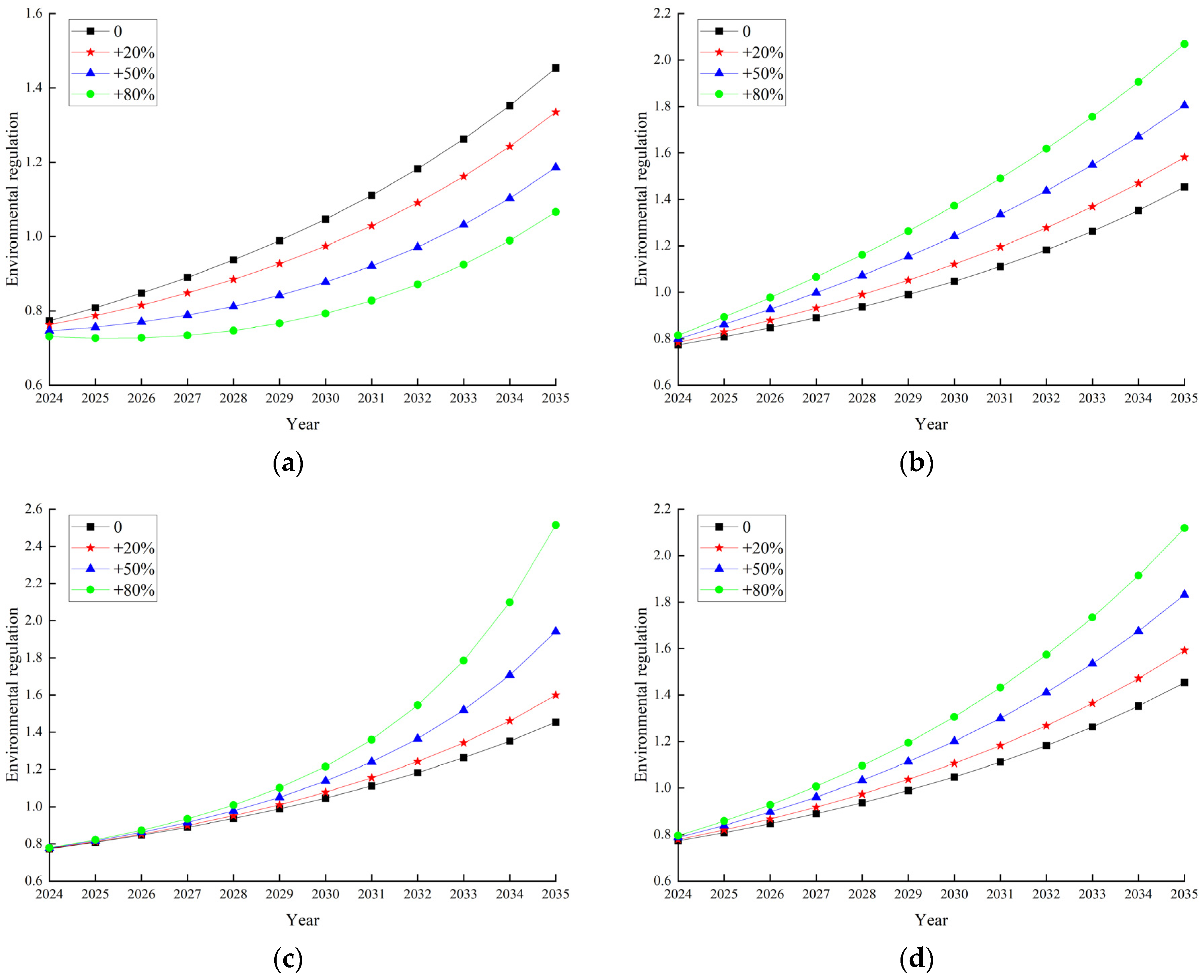

- Sensitivity analysis of environmental regulation

2.10. Design of Green Transformation Pathways

3. Results

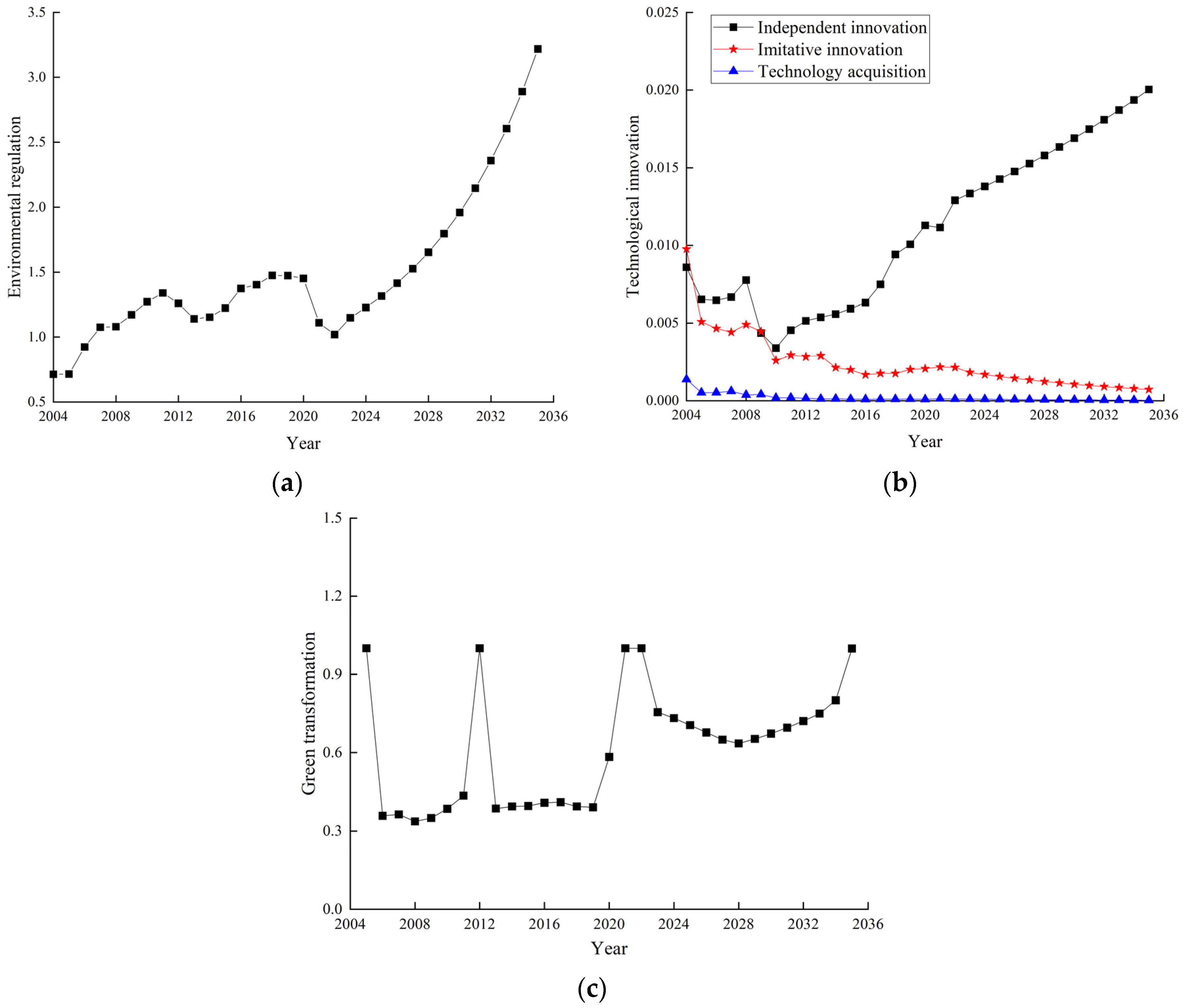

3.1. Baseline Pathway Analysis

3.2. Simulation of Green Transformation Pathways

3.2.1. Single Development Mode

3.2.2. Government–Enterprise Collaboration Mode

3.2.3. Technology Collaboration Mode

3.2.4. Diversified Collaboration Mode

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

4.1. Conclusions

4.2. Recommendations

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Deng, C.; Su, Z.; Feng, Y. Extreme climate and corporate financialization: Evidence from China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2024, 81, 306–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Gao, L.; Meng, Q.; Zhu, M.; Xiong, M. Nonlinear causal relationships between urbanization and extreme climate events in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 139889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Zhang, H.; Ye, S. Transition risks and industry connectedness under China’s dual carbon goal: Analysis based on high-dimensional time-frequency complex network. J. Quant. Tech. Econ. 2025, 42, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.G.; Chagas, M.F.; Folegatti, M.I.S.; Seabra, J.E.A.; Ramos, N.P.; Scachetti, M.T.; Picoli, J.F.; Moreira, M.M.R.; Novaes, R.M.L.; Bonomi, A.M.; et al. RenovaCalc: Calculation of Carbon Intensities Under Brazil’s National Biofuel Policy. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Li, C.; Zhang, S. Digital economy and carbon emission intensity: Evidence from ASEAN. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madjar, R.M.; Vasile Scăețeanu, G.; Butcaru, A.-C.; Moț, A. Sustainable approaches to agricultural greenhouse gas mitigation in the EU: Practices, mechanisms, and policy integration. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhu, Y. Can China’s energy policies achieve the “dual carbon” goal? A multi-dimensional analysis based on policy text tools. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Z.; Feng, H. Selection and application of China environmental sustainability policy instrumental: A quantitative analysis based on “dual carbon” policy text. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1418253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lin, B. Ecological total-factor energy efficiency of China’s heavy and light industries: Which performs better? Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 72, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhang, J.; Liu, C. Environmental regulation, financing constraints, and enterprise emission reduction: Evidence from pollution levy standards adjustment. J. Financ. Res. 2021, 495, 51–71. Available online: http://www.jryj.org.cn/CN/Y2021/V495/I9/51 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Yu, E.; Ni, Z. Can green transformation of enterprises improve the efficiency of financial assets allocation under carbon peaking and carbon neutrality goals? Stat. Res. 2025, 42, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H. Accelerating high-quality development of the light industry. West Leather 2022, 44, 2. Available online: https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-XBPG202213050.htm (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y. Research on the green transformation path of light industry under the background of new-type industrialization. Digit. Transform. 2025, 2, 30–37. Available online: https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-SZHZ202504004.htm (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Zhao, J.; Wang, X.; Li, X. Impact mechanisms of green technology innovation and environmental regulation on the green development of cities in the Yellow River Basin. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2024, 34, 132–141. Available online: https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-ZGRZ202409013.htm (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Wu, P.; Li, Y.; Ye, K. Environmental regulation, technological innovation and green total factor productivity of industrial enterprises: An analysis based on Chinese interprovincial panel data. Sci. Sci. Manag. S. T. 2024, 45, 110–128. Available online: https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-KXXG202407006.htm (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Blind, K. The influence of regulations on innovation: A quantitative assessment for OECD countries. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Feng, Y.; Wang, A. The heterogeneous effects of different types of environmental regulation on technological innovation of industrial enterprises. Manag. Rev. 2021, 33, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Huang, N.; Shen, H. Can market-incentive environmental regulation promote corporate innovation? A natural experiment based on China’s carbon emissions trading mechanism. J. Financ. Res. 2020, 1, 171–189. Available online: https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTotal-JRYJ202001010.htm (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Wang, Z.; Cao, Y.; Lin, S. The characteristics and heterogeneity of environmental regulation’s impact on enterprises’ green technology innovation—Based on green patent data of listed firms in China. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2021, 39, 909–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yu, S.; Li, M.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, C. Study of the impact of industrial restructuring on the spatial and temporal evolution of carbon emission intensity in Chinese provinces—Analysis of mediating effects based on technological innovation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, R. Does green economy contribute towards COP26 ambitions? Exploring the influence of natural resource endowment and technological innovation on the growth efficiency of China’s regional green economy. Resour. Policy 2023, 80, 103189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, P.; Yang, M.; Chen, L. How do environmental technology standards affect the green transition of China’s manufacturing industry—A perspective from technological transformation. China Ind. Econ. 2021, 9, 118–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Cheng, H.; Shao, L.; Chen, H.; Liu, X. Empirical study on the effects of coordinated development of two-way FDI on regional green transformation under the carbon peaking and carbon neutrality goals: Local and spatial spillovers. China Soft Sci. 2024, 2, 104–112. Available online: https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-ZGRK202402011.htm (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Qi, Y. Energy conservation and emission reduction, environmental regulation, and China’s industrial green transformation. Jiangxi Soc. Sci. 2018, 38, 70–79. Available online: https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTotal-JXSH201803018.htm (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Deng, H.; Yang, L. Haze governance, local competition and industrial green transformation. China Ind. Econ. 2019, 10, 118–136. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/11.3536.f.20191016.0911.014 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Ouyang, X.; Liao, J.; Wei, X.; Du, K. A good medicine tastes bitter: Environmental regulation that shapes China’s green productivity. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 105, 107423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Hu, J.; Chen, X. Environmental regulation and green total factor productivity: Dilemma or win-win? China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2018, 28, 140–149. Available online: https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-ZGRZ201811016.htm (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Richardson, P.G. Mixed Blessings: Valedictory Thoughts on System Dynamics Practice. Syst. Dyn. Rev. 2025, 41, e70010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhouma, A.; Mellios, N.; Brouwer, F.; Maria, G.J.; Laspidou, C. Assessing vineyard sustainability through a water-energy-food-ecosystems nexus indicator using system dynamics modelling. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2025, 19, 100346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, S.; Churruca, K.; Jalali, S.M.; Ellis, A.L.; Braithwaite, J. Conceptualising the impact of telehealth on rural workforce sustainability using system dynamics and the gartner hype cycle. Npj Health Syst. 2025, 2, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Khan, A.I.K.; Khan, H. System dynamics modeling of social sustainability in circular construction transitions: Causal loop analysis of stakeholder engagement mechanisms from selected developing countries’ perspective. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2026, 117, 108197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. Green industrial revolution in China: A perspective from the change of environmental total factor productivity. Econ. Res. J. 2010, 45, 21–34. Available online: https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTotal-JJYJ201011005.htm (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Oh, D.H. A global Malmquist-Luenberger productivity index. J. Prod. Anal. 2010, 34, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Liu, Z. Environmental regulation, clean-technology innovation and China’s industrial green transformation. Sci. Res. Manag. 2021, 42, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Research on the mediating and threshold effects of environmental regulation on industrial green transformation. Theor. Pract. Financ. Econ. 2023, 44, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. China’s industrial green total factor productivity and its determinants: An empirical study based on ML index and dynamic panel data model. Stat. Res. 2016, 33, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.Y.; Xu, J.; Zhao, J. Dual effects of outward foreign direct investment on industrial green transformation: Based on the bilateral stochastic frontier model. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2024, 34, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, H. Heterogeneous technological innovation and the improvement of green total factor productivity. Financ. Account. Mon. 2020, 18, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Z.; Sun, Z. Research on the green productivity of China’s light industry and the influencing factors under the constraints of carbon emissions: Based on the panel data of 16 Chinese light industry sectors. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2020, 30, 58–68. Available online: https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-ZGRZ202005007.htm (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Tao, F.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, H. Does environmental regulation improve the quantity and quality of green innovation: Evidence from the target responsibility system of environmental protection. China Ind. Econ. 2021, 2, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Tao, Y.; Cao, S.; Cao, Y. Theoretical and empirical analysis on the development of digital finance and economic growth in China. J. Quant. Technol. Econ. 2020, 37, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Wu, X.; Zhu, J. Digital finance and enterprise technology innovation: Structural feature, mechanism identification and effect difference under financial supervision. J. Manag. World 2020, 36, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Song, P.; Chen, Z. The technological path choice of China’s industrial green transformation under environmental regulation: Independent innovation or technology outsourcing? Commer. Res. 2020, 2, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cai, N.; Mao, J.; Yang, C. Independent innovation, technology introduction and green growth of industry in China: An empirical research based on industry heterogeneity. Stud. Sci. Sci. 2015, 33, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Hao, S. ESG, Innovation and the competitive advantage of construction enterprises in China—An analysis based on the system dynamics. Systems 2025, 13, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.H.; Dai, Y. A system dynamics study on the relationship between financial flexibility and new product development performance. J. Syst. Sci. 2026, 1, 114–122. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/14.1333.N.20250722.1337.030 (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Yang, Z.H.; Zhou, X.Y.; Lu, Y.Z.; Yang, A. Evolutionary State of AI-enabled smart library digital-Intelligent service system: A simulation analysis based on system dynamics model. Digit. Libr. Forum. 2025, 21, 21–32. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/11.5359.g2.20250818.0945.002 (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Wu, R.; Yang, C.; Ma, Y.Z.; Yu, T.; Zhao, H. Analysis of synergistic effects of electricity-energy-carbon market based on system dynamics. Sci. Technol. Manag. Res. 2024, 44, 211–221. Available online: https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-KJGL202420021.htm (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Fan, H.; Zheng, Y.; Li, X.; Xu, Z.; Khan, H.; Khan, I. The nexus between technological innovations, foreign direct investment, and carbon emissions: Evidence from global perspective. J. Knowl. Econ. 2025, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Shen, S. Opportunity or curse: Can green technology innovation stabilize employment? Sustainability 2024, 16, 5805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldegheishem, A. Nexus between renewable energy, technological innovation, and carbon dioxide emissions in Saudi Arabia. Open Geosci. 2025, 17, 20250768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, X.; Hu, Z.; Li, Y. Does industrial robot adoption inhibit environmental pollution in China? An empirical study on energy consumption and green technology innovation. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieply, I.; Wang, F. Does pollution control foster innovation? Quasi-experimental evidence from China’s two-control zone policy. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2025, 29, 1808–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, P.; Shi, J. Dynamic evolution of China’s government environmental regulation capability and its impact on the coupling coordinated development of the economy-environment. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2024, 91, 101785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Han, Z.; Liang, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Xie, J. Independent innovation or secondary innovation: The moderating of network embedded innovation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Cai, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Tan, H. Dual environmental regulation and corporate green transformation: How does digital leadership affect transformation effectiveness? Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 86, 108690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, Y. Environmental regulation and green transition: Quasi-natural experiment from China’s efforts in sulfur dioxide emissions control. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 139741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Xu, R.; Shen, Z.Y.; Song, M. Which type of innovation is more conducive to inclusive green growth: Independent innovation or imitation innovation? J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 406, 137026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, K. Effects of the digital economy on carbon emissions in China: An analysis based on different innovation paths. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 79451–79468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q. Digital technology innovation empowers green transformation and upgrading of manufacturing industry. Sustain. Environ. 2025, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, N.; Huo, Y. Impact of digital technology innovation on carbon emission reduction and energy rebound: Evidence from the Chinese firm level. Energy 2025, 320, 135187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S. The non-cooperative game and cooperative game between independent innovation firm and imitative innovation firm. J. Knowl. Econ. 2023, 15, 5443–5465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, F.U.; Kamil, R.; Appiah, O.K. Leveraging green technological innovation for corporate value creation: The mediating role of environmental performance in the Japanese manufacturing sector. J. Knowl. Econ. 2025, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hou, Y.; Geng, K. Environmental regulation, green technology innovation, and industrial green transformation: Empirical evidence from a developing economy. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Annual Average Employees (Ten Thousand People) | Total Energy Consumption (Ten Thousand Tons of Standard Coal) | Net Fixed Assets (Billion Yuan) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Historical Value | Simulated Value | Error (%) | Historical Value | Simulated Value | Error (%) | Historical Value | Simulated Value | Error (%) | |

| 2004 | 144.313 | 144.313 | 0.000 | 1190.920 | 1190.920 | 0.000 | 1091.938 | 1091.940 | 0.000 |

| 2005 | 164.688 | 165.932 | 0.756 | 1311.983 | 1313.150 | 0.089 | 1221.188 | 1234.080 | 1.056 |

| 2006 | 175.250 | 177.360 | 1.204 | 1423.981 | 1425.950 | 0.138 | 1372.188 | 1394.860 | 1.652 |

| 2007 | 185.875 | 188.999 | 1.681 | 1492.836 | 1495.760 | 0.196 | 1565.938 | 1601.330 | 2.260 |

| 2008 | 205.063 | 210.525 | 2.664 | 1644.489 | 1649.810 | 0.324 | 1876.750 | 1939.530 | 3.345 |

| 2009 | 202.938 | 208.537 | 2.759 | 1655.210 | 1660.450 | 0.317 | 2051.125 | 2122.640 | 3.487 |

| 2010 | 214.625 | 220.967 | 2.955 | 1662.413 | 1667.840 | 0.326 | 2347.875 | 2435.490 | 3.732 |

| 2011 | 199.125 | 201.598 | 1.242 | 1698.990 | 1701.520 | 0.149 | 2523.563 | 2584.330 | 2.408 |

| 2012 | 205.156 | 208.128 | 1.449 | 1759.414 | 1762.790 | 0.192 | 2864.188 | 2937.680 | 2.566 |

| 2013 | 211.188 | 214.486 | 1.562 | 2088.991 | 2093.510 | 0.216 | 3282.313 | 3368.640 | 2.630 |

| 2014 | 216.500 | 220.497 | 1.846 | 2075.869 | 2080.940 | 0.244 | 3716.875 | 3821.450 | 2.814 |

| 2015 | 213.750 | 217.926 | 1.954 | 2076.456 | 2081.890 | 0.262 | 3978.250 | 4092.500 | 2.872 |

| 2016 | 208.250 | 212.312 | 1.951 | 2113.122 | 2116.580 | 0.164 | 4178.250 | 4298.270 | 2.872 |

| 2017 | 192.063 | 195.575 | 1.829 | 2131.526 | 2135.150 | 0.170 | 3715.625 | 3819.140 | 2.786 |

| 2018 | 167.088 | 170.301 | 1.923 | 2107.563 | 2111.020 | 0.164 | 3253.029 | 3342.930 | 2.764 |

| 2019 | 163.813 | 166.436 | 1.602 | 2125.875 | 2128.530 | 0.125 | 3229.563 | 3312.720 | 2.575 |

| 2020 | 152.813 | 155.516 | 1.769 | 2102.563 | 2108.590 | 0.287 | 3133.625 | 3217.230 | 2.668 |

| 2021 | 153.813 | 157.275 | 2.251 | 2341.500 | 2349.010 | 0.321 | 3307.875 | 3404.460 | 2.920 |

| 2022 | 144.288 | 148.051 | 2.608 | 2328.938 | 2336.990 | 0.346 | 3434.297 | 3536.960 | 2.989 |

| 2023 | 140.931 | 144.931 | 2.838 | 2316.375 | 2324.530 | 0.352 | 3560.719 | 3670.030 | 3.070 |

| Year | Main business revenue (billion yuan) | Carbon dioxide emissions (ten thousand tons) | Solid wastes generated (ten thousand tons) | ||||||

| Historical value | Simulated value | Error (%) | Historical value | Simulated value | Error (%) | Historical value | Simulated value | Error (%) | |

| 2004 | 3154.210 | 3154.210 | 0.000 | 1466.795 | 1466.800 | 0.000 | 331.563 | 331.563 | 0.000 |

| 2005 | 4128.093 | 4144.040 | 0.386 | 1530.039 | 1545.080 | 0.983 | 345.250 | 345.407 | 0.045 |

| 2006 | 5063.072 | 5096.690 | 0.664 | 1597.276 | 1621.050 | 1.488 | 376.625 | 376.886 | 0.069 |

| 2007 | 6416.399 | 6469.250 | 0.824 | 1641.608 | 1667.620 | 1.585 | 417.963 | 418.283 | 0.077 |

| 2008 | 7885.441 | 7971.640 | 1.093 | 1875.292 | 1909.810 | 1.841 | 455.813 | 456.227 | 0.091 |

| 2009 | 8914.736 | 9014.640 | 1.121 | 1857.365 | 1901.280 | 2.364 | 471.250 | 471.791 | 0.115 |

| 2010 | 11,135.667 | 11,265.300 | 1.164 | 1931.639 | 1981.690 | 2.591 | 520.269 | 520.901 | 0.121 |

| 2011 | 13,361.159 | 13,520.100 | 1.190 | 1884.778 | 1924.560 | 2.111 | 519.288 | 519.821 | 0.103 |

| 2012 | 15,216.730 | 15,408.400 | 1.260 | 2127.909 | 2170.580 | 2.005 | 498.069 | 498.538 | 0.094 |

| 2013 | 17,238.941 | 17,494.200 | 1.481 | 2733.793 | 2813.600 | 2.919 | 487.081 | 487.771 | 0.142 |

| 2014 | 18,838.162 | 19,121.500 | 1.504 | 2545.243 | 2616.050 | 2.782 | 495.000 | 495.688 | 0.139 |

| 2015 | 19,791.575 | 20,091.600 | 1.516 | 2702.836 | 2773.430 | 2.612 | 486.969 | 487.612 | 0.132 |

| 2016 | 20,889.749 | 21,211.700 | 1.541 | 2617.523 | 2684.550 | 2.561 | 975.706 | 976.967 | 0.129 |

| 2017 | 19,230.159 | 19,522.900 | 1.522 | 2357.911 | 2415.530 | 2.444 | 907.719 | 908.845 | 0.124 |

| 2018 | 16,200.838 | 16,438.300 | 1.466 | 1871.118 | 1912.560 | 2.215 | 1003.406 | 1004.600 | 0.119 |

| 2019 | 15,989.494 | 16,225.700 | 1.477 | 1792.189 | 1829.040 | 2.056 | 1151.194 | 1152.550 | 0.118 |

| 2020 | 15,665.413 | 15,892.300 | 1.448 | 1635.367 | 1660.530 | 1.539 | 482.725 | 483.177 | 0.094 |

| 2021 | 17,979.838 | 18,265.600 | 1.589 | 1681.474 | 1719.660 | 2.271 | 518.088 | 518.717 | 0.122 |

| 2022 | 16,446.106 | 16,706.800 | 1.585 | 1567.609 | 1598.400 | 1.964 | 504.650 | 505.234 | 0.116 |

| 2023 | 16,510.719 | 16,771.700 | 1.581 | 1453.744 | 1479.480 | 1.770 | 544.263 | 544.866 | 0.111 |

| Pathway | Mode | Environmental Regulation | Independent Innovation | Imitative Innovation | Technology Acquisition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Single development mode | Increase | |||

| 2 | Decrease | ||||

| 3 | Increase | ||||

| 4 | Decrease | ||||

| 5 | Increase | ||||

| 6 | Decrease | ||||

| 7 | Increase | ||||

| 8 | Decrease | ||||

| 9 | Government–enterprise collaboration mode | Increase | Increase | ||

| 10 | Increase | Decrease | |||

| 11 | Increase | Increase | |||

| 12 | Increase | Decrease | |||

| 13 | Increase | Increase | |||

| 14 | Increase | Decrease | |||

| 15 | Decrease | Increase | |||

| 16 | Decrease | Decrease | |||

| 17 | Decrease | Increase | |||

| 18 | Decrease | Decrease | |||

| 19 | Decrease | Increase | |||

| 20 | Decrease | Decrease | |||

| 21 | Technology collaboration mode | Increase | Increase | Increase | |

| 22 | Increase | Increase | Decrease | ||

| 23 | Increase | Decrease | Increase | ||

| 24 | Increase | Decrease | Decrease | ||

| 25 | Decrease | Increase | Increase | ||

| 26 | Decrease | Increase | Decrease | ||

| 27 | Decrease | Decrease | Increase | ||

| 28 | Decrease | Decrease | Decrease | ||

| 29 | Diversified collaboration mode | Increase | Increase | Increase | Increase |

| 30 | Increase | Increase | Increase | Decrease | |

| 31 | Increase | Increase | Decrease | Increase | |

| 32 | Increase | Increase | Decrease | Decrease | |

| 33 | Increase | Decrease | Increase | Increase | |

| 34 | Increase | Decrease | Increase | Decrease | |

| 35 | Increase | Decrease | Decrease | Increase | |

| 36 | Increase | Decrease | Decrease | Decrease | |

| 37 | Decrease | Increase | Increase | Increase | |

| 38 | Decrease | Increase | Increase | Decrease | |

| 39 | Decrease | Increase | Decrease | Increase | |

| 40 | Decrease | Increase | Decrease | Decrease | |

| 41 | Decrease | Decrease | Increase | Increase | |

| 42 | Decrease | Decrease | Increase | Decrease | |

| 43 | Decrease | Decrease | Decrease | Increase | |

| 44 | Decrease | Decrease | Decrease | Decrease |

| Pathway | Growth Rate of Solid Wastes Utilized | Growth Rate of Intramural Expenditure on R&D | Growth Rate of Expenditure on Technological Renovation | Growth Rate of Expenditure on Technology Acquisition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline pathway | 0.0566 | 0.1374 | 0.0177 | 0.0013 |

| Increase by 50% | 0.0849 | 0.2061 | 0.0266 | 0.0020 |

| Decrease by 50% | 0.0283 | 0.0687 | 0.0089 | 0.0007 |

| Year | Pathway 0 | Pathway 1 | Pathway 2 | Pathway 3 | Pathway 4 | Pathway 5 | Pathway 6 | Pathway 7 | Pathway 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 0.7320 | 0.7320 | 0.7319 | 0.7386 | 0.7254 | 0.7321 | 0.7319 | 0.7320 | 0.7320 |

| 2025 | 0.7050 | 0.7050 | 0.7050 | 0.7188 | 0.6924 | 0.7051 | 0.7048 | 0.7050 | 0.7050 |

| 2026 | 0.6768 | 0.6768 | 0.6767 | 0.6985 | 0.6587 | 0.6770 | 0.6766 | 0.6768 | 0.6768 |

| 2027 | 0.6495 | 0.6496 | 0.6495 | 0.6798 | 0.6265 | 0.6498 | 0.6493 | 0.6495 | 0.6495 |

| 2028 | 0.6350 | 0.6351 | 0.6350 | 0.6648 | 0.6332 | 0.6350 | 0.6350 | 0.6350 | 0.6350 |

| 2029 | 0.6527 | 0.6527 | 0.6526 | 0.6567 | 0.6503 | 0.6527 | 0.6526 | 0.6527 | 0.6527 |

| 2030 | 0.6727 | 0.6728 | 0.6726 | 0.6788 | 0.6697 | 0.6727 | 0.6726 | 0.6727 | 0.6727 |

| 2031 | 0.6952 | 0.6953 | 0.6951 | 0.7050 | 0.6913 | 0.6953 | 0.6952 | 0.6952 | 0.6952 |

| 2032 | 0.7206 | 0.7207 | 0.7205 | 0.7371 | 0.7152 | 0.7207 | 0.7206 | 0.7206 | 0.7206 |

| 2033 | 0.7492 | 0.7493 | 0.7491 | 0.7794 | 0.7416 | 0.7492 | 0.7491 | 0.7492 | 0.7492 |

| 2034 | 0.8006 | 0.8007 | 0.8003 | 0.8447 | 0.8314 | 0.8004 | 0.8006 | 0.8006 | 0.8006 |

| 2035 | 0.9992 | 0.9996 | 0.9987 | 0.9980 | 0.9996 | 0.9993 | 0.9991 | 0.9992 | 0.9992 |

| Mean | 0.7240 | 0.7241 | 0.7239 | 0.7417 | 0.7196 | 0.7241 | 0.7239 | 0.7240 | 0.7240 |

| Year | Pathway 9 | Pathway 10 | Pathway 11 | Pathway 12 | Pathway 13 | Pathway 14 | Pathway 15 | Pathway 16 | Pathway 17 | Pathway 18 | Pathway 19 | Pathway 20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 0.7386 | 0.7254 | 0.7321 | 0.7319 | 0.7320 | 0.7320 | 0.7386 | 0.7254 | 0.7320 | 0.7319 | 0.7319 | 0.7319 |

| 2025 | 0.7189 | 0.6924 | 0.7051 | 0.7048 | 0.7050 | 0.7050 | 0.7188 | 0.6924 | 0.7051 | 0.7048 | 0.7050 | 0.7050 |

| 2026 | 0.6985 | 0.6588 | 0.6770 | 0.6766 | 0.6768 | 0.6768 | 0.6985 | 0.6587 | 0.6769 | 0.6765 | 0.6767 | 0.6767 |

| 2027 | 0.6799 | 0.6266 | 0.6498 | 0.6493 | 0.6496 | 0.6496 | 0.6798 | 0.6265 | 0.6498 | 0.6492 | 0.6495 | 0.6495 |

| 2028 | 0.6648 | 0.6332 | 0.6351 | 0.6350 | 0.6351 | 0.6351 | 0.6647 | 0.6332 | 0.6350 | 0.6349 | 0.6350 | 0.6350 |

| 2029 | 0.6568 | 0.6504 | 0.6528 | 0.6527 | 0.6527 | 0.6527 | 0.6567 | 0.6503 | 0.6526 | 0.6526 | 0.6526 | 0.6526 |

| 2030 | 0.6789 | 0.6698 | 0.6728 | 0.6727 | 0.6728 | 0.6728 | 0.6787 | 0.6696 | 0.6726 | 0.6726 | 0.6726 | 0.6726 |

| 2031 | 0.7051 | 0.6914 | 0.6954 | 0.6953 | 0.6953 | 0.6953 | 0.7049 | 0.6912 | 0.6952 | 0.6951 | 0.6951 | 0.6951 |

| 2032 | 0.7372 | 0.7153 | 0.7208 | 0.7207 | 0.7207 | 0.7207 | 0.7370 | 0.7151 | 0.7206 | 0.7205 | 0.7205 | 0.7205 |

| 2033 | 0.7795 | 0.7418 | 0.7494 | 0.7492 | 0.7493 | 0.7493 | 0.7793 | 0.7415 | 0.7491 | 0.7490 | 0.7491 | 0.7491 |

| 2034 | 0.8448 | 0.8316 | 0.8007 | 0.8009 | 0.8007 | 0.8007 | 0.8446 | 0.8311 | 0.8003 | 0.8005 | 0.8003 | 0.8003 |

| 2035 | 0.9999 | 0.9999 | 1.0000 | 0.9993 | 0.9996 | 0.9996 | 0.9981 | 0.9991 | 0.9992 | 0.9987 | 0.9987 | 0.9987 |

| Mean | 0.7419 | 0.7197 | 0.7242 | 0.7240 | 0.7241 | 0.7241 | 0.7416 | 0.7195 | 0.7240 | 0.7239 | 0.7239 | 0.7239 |

| Year | Pathway 21 | Pathway 22 | Pathway 23 | Pathway 24 | Pathway 25 | Pathway 26 | Pathway 27 | Pathway 28 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 0.7387 | 0.7387 | 0.7385 | 0.7385 | 0.7255 | 0.7255 | 0.7254 | 0.7254 |

| 2025 | 0.7190 | 0.7190 | 0.7187 | 0.7187 | 0.6926 | 0.6926 | 0.6923 | 0.6923 |

| 2026 | 0.6987 | 0.6987 | 0.6983 | 0.6983 | 0.6589 | 0.6589 | 0.6585 | 0.6585 |

| 2027 | 0.6801 | 0.6801 | 0.6796 | 0.6796 | 0.6268 | 0.6268 | 0.6263 | 0.6263 |

| 2028 | 0.6651 | 0.6651 | 0.6644 | 0.6644 | 0.6332 | 0.6332 | 0.6332 | 0.6332 |

| 2029 | 0.6567 | 0.6567 | 0.6567 | 0.6567 | 0.6504 | 0.6504 | 0.6503 | 0.6503 |

| 2030 | 0.6788 | 0.6788 | 0.6787 | 0.6787 | 0.6697 | 0.6697 | 0.6696 | 0.6696 |

| 2031 | 0.7050 | 0.7050 | 0.7049 | 0.7049 | 0.6913 | 0.6913 | 0.6912 | 0.6912 |

| 2032 | 0.7372 | 0.7372 | 0.7370 | 0.7370 | 0.7152 | 0.7152 | 0.7152 | 0.7152 |

| 2033 | 0.7796 | 0.7796 | 0.7792 | 0.7792 | 0.7417 | 0.7417 | 0.7416 | 0.7416 |

| 2034 | 0.8452 | 0.8452 | 0.8442 | 0.8442 | 0.8313 | 0.8313 | 0.8314 | 0.8314 |

| 2035 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9978 | 0.9978 | 0.9996 | 0.9996 | 0.9995 | 0.9995 |

| Mean | 0.7420 | 0.7420 | 0.7415 | 0.7415 | 0.7197 | 0.7197 | 0.7195 | 0.7195 |

| Year | Pathway 29 | Pathway 30 | Pathway 31 | Pathway 32 | Pathway 33 | Pathway 34 | Pathway 35 | Pathway 36 | Pathway 37 | Pathway 38 | Pathway 39 | Pathway 40 | Pathway 41 | Pathway 42 | Pathway 43 | Pathway 44 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | 0.7387 | 0.7387 | 0.7385 | 0.7385 | 0.7255 | 0.7255 | 0.7254 | 0.7254 | 0.7387 | 0.7387 | 0.7385 | 0.7385 | 0.7255 | 0.7255 | 0.7254 | 0.7254 |

| 2025 | 0.7190 | 0.7190 | 0.7187 | 0.7187 | 0.6926 | 0.6926 | 0.6923 | 0.6923 | 0.7190 | 0.7190 | 0.7187 | 0.7187 | 0.6925 | 0.6925 | 0.6922 | 0.6922 |

| 2026 | 0.6988 | 0.6988 | 0.6983 | 0.6983 | 0.6589 | 0.6589 | 0.6585 | 0.6585 | 0.6987 | 0.6987 | 0.6982 | 0.6982 | 0.6589 | 0.6589 | 0.6585 | 0.6585 |

| 2027 | 0.6801 | 0.6801 | 0.6796 | 0.6796 | 0.6268 | 0.6268 | 0.6263 | 0.6263 | 0.6801 | 0.6801 | 0.6795 | 0.6795 | 0.6267 | 0.6267 | 0.6263 | 0.6263 |

| 2028 | 0.6651 | 0.6651 | 0.6645 | 0.6645 | 0.6333 | 0.6333 | 0.6332 | 0.6332 | 0.6650 | 0.6650 | 0.6644 | 0.6644 | 0.6332 | 0.6332 | 0.6331 | 0.6331 |

| 2029 | 0.6568 | 0.6568 | 0.6567 | 0.6567 | 0.6504 | 0.6504 | 0.6504 | 0.6504 | 0.6567 | 0.6567 | 0.6566 | 0.6566 | 0.6503 | 0.6503 | 0.6503 | 0.6503 |

| 2030 | 0.6789 | 0.6789 | 0.6788 | 0.6788 | 0.6698 | 0.6698 | 0.6697 | 0.6697 | 0.6788 | 0.6788 | 0.6787 | 0.6787 | 0.6696 | 0.6696 | 0.6696 | 0.6696 |

| 2031 | 0.7051 | 0.7051 | 0.7050 | 0.7050 | 0.6914 | 0.6914 | 0.6913 | 0.6913 | 0.7050 | 0.7050 | 0.7048 | 0.7048 | 0.6912 | 0.6912 | 0.6911 | 0.6911 |

| 2032 | 0.7373 | 0.7373 | 0.7371 | 0.7371 | 0.7153 | 0.7153 | 0.7153 | 0.7153 | 0.7371 | 0.7371 | 0.7369 | 0.7369 | 0.7151 | 0.7151 | 0.7151 | 0.7151 |

| 2033 | 0.7797 | 0.7797 | 0.7793 | 0.7793 | 0.7418 | 0.7418 | 0.7417 | 0.7417 | 0.7795 | 0.7795 | 0.7791 | 0.7791 | 0.7416 | 0.7416 | 0.7415 | 0.7415 |

| 2034 | 0.8453 | 0.8453 | 0.8444 | 0.8444 | 0.8316 | 0.8316 | 0.8315 | 0.8315 | 0.8451 | 0.8451 | 0.8442 | 0.8442 | 0.8311 | 0.8311 | 0.8312 | 0.8312 |

| 2035 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9971 | 0.9971 | 0.9994 | 0.9994 | 0.9993 | 0.9993 |

| Mean | 0.7421 | 0.7421 | 0.7417 | 0.7417 | 0.7198 | 0.7198 | 0.7196 | 0.7197 | 0.7420 | 0.7420 | 0.7414 | 0.7414 | 0.7196 | 0.7196 | 0.7195 | 0.7195 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, J.; Su, F.; Cao, D. Green Transformation of China’s Light Industry: Regulatory and Innovation Policy Scenarios, 2023–2036. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411105

Chang J, Su F, Cao D. Green Transformation of China’s Light Industry: Regulatory and Innovation Policy Scenarios, 2023–2036. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411105

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Jiangbo, Fang Su, and Di Cao. 2025. "Green Transformation of China’s Light Industry: Regulatory and Innovation Policy Scenarios, 2023–2036" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411105

APA StyleChang, J., Su, F., & Cao, D. (2025). Green Transformation of China’s Light Industry: Regulatory and Innovation Policy Scenarios, 2023–2036. Sustainability, 17(24), 11105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411105