Abstract

This study systematically reviewed 38 peer-reviewed articles (2020–2024) on social media and environmental communication in China following the PRISMA 2020 guidelines. It identified dominant research patterns across themes, theories, methods, and platforms. The field is heavily shaped by behavioral models (e.g., TPB, NAT) and survey-based designs, while institutional dynamics, platform governance, and cross-platform processes remain underexamined. Weibo and WeChat dominate as research sites, whereas short-video platforms like TikTok and Bilibili are emerging but undertheorized. Cross-level frameworks are frequently reduced to individual-level predictors, and social media are often treated as neutral delivery tools. The review highlights the need for multi-level approaches linking individual cognition, media architectures, and governance contexts to better capture how environmental publics form and operate in China’s platformed ecology. This study contributes to the realization of the Sustainable Development Goals by revealing how social media infrastructures mediate environmental awareness, engagement, and systemic change.

1. Introduction

Climate change, air pollution and associated extreme weather events are intensifying risks to public health, food security and economic stability worldwide, and these burdens are unevenly distributed across regions and social groups [1]. Given these interconnected crises, the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development proposes 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), with a particular call for strengthening education, public awareness, and institutional capacity building in climate change mitigation, adaptation, impact reduction, and early warning [2]. In this context, effective environmental communication emerges as a crucial enabling condition for advancing multiple SDGs, as it translates scientific evidence into public understanding, everyday practices and political support.

Environmental communication examines how humans perceive, discuss, and respond to environmental issues, with increasing attention to climate change communication [3]. In recent years, social media have emerged as a pivotal arena for environmental discourse, facilitating rapid information dissemination and mobilizing public engagement in debates around climate change, pollution and sustainability. Scholars have shown that social media platforms can enhance environmental awareness and shape public perceptions by enabling interactive and participatory communication [4,5]. These digital networks allow governments, NGOs, businesses and citizen activists to disseminate information in real-time, advocate for policy change and experiment with new sustainability narratives, while also enabling bottom-up discussion and critique. Recent scholarship underscores that sustainable development depends not only on the content of environmental messages but also on the configuration of communication structures and processes of mediatization, which condition the distribution of voice, the visibility of particular sustainability imaginaries, and the capacity of societies to advance progress towards the SDGs [6,7].

China presents a particularly significant context for examining this nexus. As the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases and a crucial player in global climate governance, it faces major environmental challenges and policy imperatives [8]. China’s highly developed digital platforms, notably WeChat, Weibo and TikTok (known as Douyin in China), reach vast audiences and have become primary channels through which many citizens obtain environmental and climate information [9,10]. At the same time, strong state and platform governance shape the online communication environment: authorities promote official narratives (such as carbon-neutrality goals) while censoring or downplaying content deemed likely to spark collective action or criticism [11]. Consequently, climate discourse is expanding yet remains predominantly top-down; between 2017 and 2021, only about 0.12% of Weibo’s trending topics were climate-related, indicating the difficulty of bringing climate issues into the digital mainstream [12]. This combination of high participatory potential and intensive governance makes China a distinctive setting for examining how social media can advance environmental communication.

Globally, scholarship on social media and climate or environmental communication has expanded rapidly, and several recent reviews synthesize this work. Sultana et al.’s systematic review of climate change and social media identified 45 studies published between 2009 and 2022, but showed that evidence is heavily concentrated on Twitter and other Western platforms, with most cases located in the United States and Europe and non-Western contexts such as China appearing only at the margins [13]. Pearce et al.’s earlier critical review of social media and climate change likewise highlights a substantial bias toward Twitter-based studies and calls for more research on visual communication and alternative platforms beyond Twitter [14]. As a result, existing reviews tell us relatively little about how environmental issues are communicated on Chinese social media, where domestically governed platforms such as WeChat, Weibo, and TikTok operate within a distinctive media-governance regime and digital ecology. This gap motivates the present review, which systematically examines empirical studies of social media and environmental communication in China to map thematic, theoretical, methodological, and platform-specific developments in this emerging field.

In response to scholarly calls for a stronger theoretical integration of sustainability into communication research and for a more effective mobilization of social media in climate communication, this review attempts to answer the following research questions:

RQ1: What are the main environmental topics addressed in studies on social media and environmental communication in China?

RQ2: What are the main theoretical frameworks applied in studies on social media and environmental communication in China?

RQ3: What are the main research methodologies employed in studies on social media and environmental communication in China?

RQ4: What are the main social media platforms examined in studies on environmental communication in China?

RQ5: What are the main research gaps and suggestions for future research on social media and environmental communication in China?

Each of these questions will be addressed through a systematic synthesis of findings from relevant studies published between 2020 and 2024, offering a timely assessment of the present status, trends, and future challenges at the intersection of social media, environmental communication, and the Chinese context.

2. Materials and Methods

The review is guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) framework [15], which provides a standardized and transparent protocol for literature identification, screening, and analysis [16].

2.1. Research Strategy

This review aims to map how scholarship on social media and environmental communication in China is represented within the international, English-language academic conversation. To identify relevant literature, a systematic search was initiated in August 2025 across two major academic databases: Web of Science and Scopus. These two databases are widely used in meta-analysis studies and are recognized for their broad subject coverage and high authority in international academic searches [17,18]. The search scope covers publications from 2020 to 2024. This time frame was chosen to capture the latest developments in digital platform and environmental communication research in the Chinese context. Due to the fact that the year 2025 is still ongoing at the time of data collection, and in line with previous studies that recommend not including incomplete years in bibliometric analyses [19], data for this year were therefore excluded from the analysis.

To ensure regional focus, all queries required the use of “China” and related terms such as “Chinese” in the subject field. For social media, we defined it as social networking platforms rather than the general term “online media”. Therefore, our core terms included “social media”, “social media platforms”, and platform-specific keywords such as “Weibo”, “WeChat”, and “TikTok”. To maintain consistent and comprehensive coverage of environmental communication, the analysis used the following key terms: “environmental communication”, “environmental discourse”, “climate communication”, and “green communication” as key terms. We combined terms with Boolean operators (AND/OR).

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Clear inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined to ensure that the selected studies aligned with the research scope and addressed the identified research questions. These criteria were formulated with reference to prior literature and are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.3. Data Screening

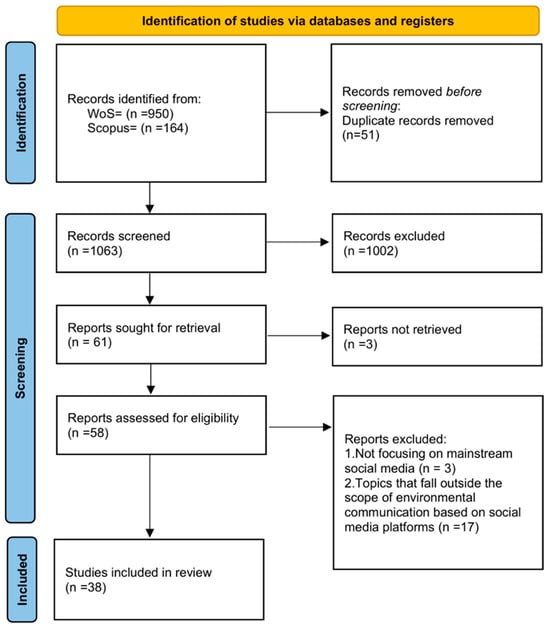

The screening process aimed to remove duplicate and irrelevant records. An initial 1114 records were retrieved from Web of Science (n = 950) and Scopus (n = 164). Duplicate records were first removed across databases, yielding 1063 records for screening. Titles and abstracts were then assessed against pre-specified inclusion criteria: publication period 2020–2024, peer-reviewed journal articles, English-language, and subject categories limited to Communication Studies, Environmental Science, Environmental Studies, and Humanities and Social Sciences. These fields were selected to capture the application and development of environmental communication within communication studies and the broader humanities and social sciences while acknowledging its interdisciplinary links with environmental science. After screening and database consolidation, 58 articles advanced to eligibility assessment.

To minimize the risk of bias during the screening and subsequent stages of this review, our team followed established guidance for systematic reviews and the PRISMA framework, with a strong emphasis on a priori protocol, dual screening, and transparent documentation. We defined review questions and key concepts in advance and agreed on the databases, time frame, search strings, and inclusion and exclusion criteria. At least two team members independently screened titles/abstracts and, where necessary, full texts; discrepancies were resolved through discussion. A piloted, standardized data-extraction template and calibration meetings were used to harmonize coding and thematic categories, and all key decisions were recorded, thereby enhancing the transparency, reproducibility, and auditability of the review.

2.4. Data Eligibility

At the eligibility stage, all 58 articles were assessed in full text against the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Studies were excluded if they focused on non-mainstream platforms such as Ant Forest, or addressed themes outside the scope of social media–based environmental communication (e.g., financial technologies, consumer marketing, air pollution psychology, or non-Chinese contexts). In total, 23 articles were excluded for these reasons. The final dataset therefore comprised 38 empirical studies, which were included in the systematic review and subsequent synthesis (see Figure 1). The PRISMA 2020 list can be found in Table S1.

Figure 1.

The PRISMA2020 framework utilized in this study for systematic review.

3. Results

3.1. Publication Trends

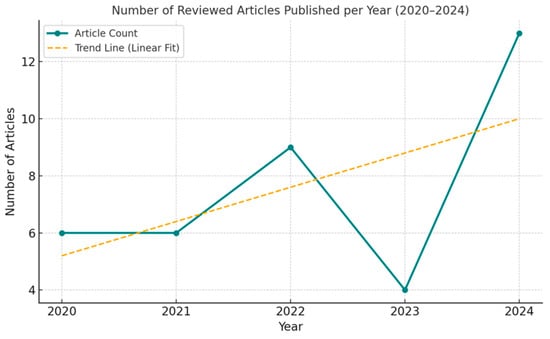

Between 2020 and 2024, scholarly interest in social media and environmental communication in China demonstrated a discernible upward trend (see Figure 2). A linear regression fitted to annual publication counts yielded a positive slope, indicating a steady increase in research output over the five-year period. This growth parallels China’s policy emphasis on carbon neutrality and ecological modernization, which has positioned digital platforms as pivotal sites of environmental governance and public discourse. Throughout this period, platforms such as Weibo, WeChat, and TikTok increasingly served as venues for information dissemination, civic participation, and behavioral guidance related to environmental issues.

Figure 2.

Yearly distribution of reviewed articles with linear trend line (2020–2024).

From 2020 to 2021, approximately half of the studies relied on survey-based methods to examine environmental attitudes and behavioral intentions. However, even during this early phase, a diversity of research themes—including digital discourse, citizen engagement, and institutional communication—had already begun to emerge. In contrast, the period from 2022 to 2024 witnessed a methodological expansion, with increasing adoption of content analysis, experimental designs, and computational approaches such as topic modeling. These later studies more explicitly engaged with complex issues such as misinformation, risk perception, and the communicative dynamics of policy implementation. This evolution reflects both the maturation of the field and a growing interest in interdisciplinary frameworks that connect individual behavior with institutional and discursive processes in China’s digital ecology.

3.2. Research Topics in Reviewed Studies

In terms of topic modeling, a latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA) unsupervised model was employed to analyze a corpus comprising 38 documents, thereby identifying latent themes. The LDA is a probabilistic topic model based on Bayesian latent variables, which conceptualizes documents as a collection of subjects, each represented by a set of words [20]. In this study, we used Python 3.13.5 along with the Gensim and pyLDAvis libraries to implement a LDA model. To ensure semantic validity, the text was cleaned using a multi-stage preprocessing pipeline: (1) removal of common English stop-words (e.g., a, the, and, of), (2) removal of high-frequency academic terms (e.g., study, results, methods), (3) removal of domain-generic environmental words (e.g., climate, environment, information), and (4) iterative elimination of recurring noise tokens identified through several test runs (e.g., signi, uence, environ, network, users, three, only). Words ≤ 3 characters, broken citation tokens, and reference sections were also removed, and multiword variants (e.g., norms) were merged for consistency. After cleaning, the final dictionary contained 5769 unique terms, and the top 30 most frequent words were extracted to support subsequent topic modeling.

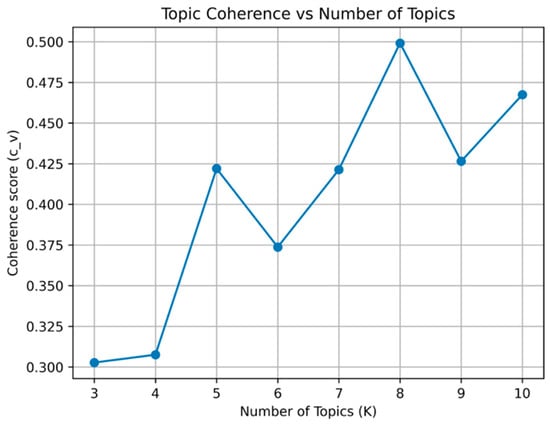

Coherence is a widely used statistic that captures semantic similarity within a topic and distinctiveness between topics [21]. To identify an appropriate number of topics, LDA models with K = 3–10 was estimated in Python using identical preprocessing procedures and hyperparameters. Topic coherence (Cv metric) was computed for each model, and the resulting scores are plotted in Figure 3. Coherence gradually increased from K = 3 (Cv ≈ 0.30) and reached its highest value at K = 8 (Cv ≈ 0.50), while the K = 7 model achieved a slightly lower but comparable score (Cv = 0.4214). As previous work notes, coherence typically improves as more topics are added, but very high scores at large K can reflect over-fitting or redundant, low-prevalence topics rather than genuinely new themes. In our case, pyLDAvis inspection of the K = 8 solution revealed one topic accounting for approximately 0% of tokens and lacking a clear substantive interpretation, indicating an over-fitted residual topic. Following recommendations that topic selection should combine automatic metrics with parsimony and human interpretability, we therefore adopted the seven-topic solution for subsequent analysis.

Figure 3.

Variation of topic coherence (Cv) with the number of topics (k) in the LDA model.

Topic naming was conducted by combining the top-ranked keywords within each topic and a close reading of representative texts with the highest topic probabilities, following the interpretive strategy of Bennett et al. [22]. This hybrid approach ensured that each topic label reflected both statistical salience and contextual meaning. The seven topics can be summarized as (see Table 2): (1) carbon-related communication and message processing/text analysis, combining carbon and “dual-carbon” issues with elaboration, dual-processing models and textual or emotional analysis; (2) norms, risk and interpersonal narrative in communication, linking social norms, risk perception, responsibility and willingness to act through interpersonal discussion and narrative exposure; (3) ENGOs and ecological activism in the online public sphere, focusing on community-based, microblog-mediated advocacy and grassroots–state interactions; (4) waste and incineration conflicts and civic mobilization, including public deliberation, protests and event-driven participation around waste-to-energy projects; (5) psychological distance, perceived threat and pro-environmental intentions, especially in experimental studies on waste sorting and climate risk framing; (6) agenda-setting and visual social media actors, highlighting how youth, celebrities and platforms such as Bilibili use framed videos to shape environmental agendas; and (7) misinformation, authority and scientific credibility, examining how authority cues, expert references and semantic features influence the perceived veracity of climate and environmental information.

Table 2.

Categories from LDA topic analysis and a brief summary of their content.

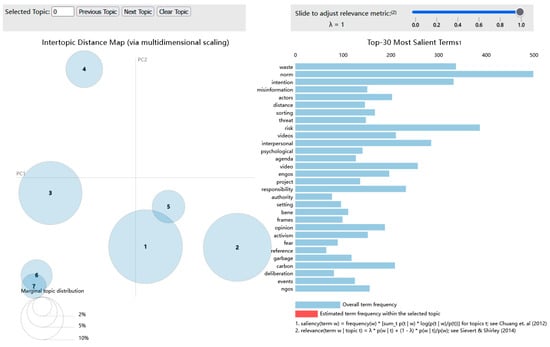

In the pyLDAvis visualization of the final seven-topic model (Figure 4), the left panel shows an inter-topic distance map. Each circle corresponds to one topic; the size of the circle represents the marginal prevalence of that topic in the corpus (larger circles indicate topics that appear more often across documents). The distance between circles reflects their similarity: topics 1 and 5 as well as topics 6 and 7 partly overlap, indicating that they share related concepts (e.g., norms, risk and environmental behavior), whereas topics 2, 3 and 4 are more distant and therefore capture more distinct thematic areas. Interactive visualization of LDA topic models using pyLDAvis is shown in Figure S1.

Figure 4.

Visual of LDA topic model using pyLDAvis [23,24].

To complement the topic modeling results, a word cloud was generated using the titles, abstracts, and keywords of the 38 reviewed articles (see Figure 5). This visualization highlights dominant lexical themes such as “climate change”, “video”, “emotion”, and “frame”, which align closely with the topic clusters identified via LDA. It also underscores the increasing prominence of video platforms such as Bilibili and TikTok in the discourse on environmental communication in China.

Figure 5.

Word cloud of key terms in the reviewed literature.

3.3. Theoretical Frameworks in Reviewed Studies

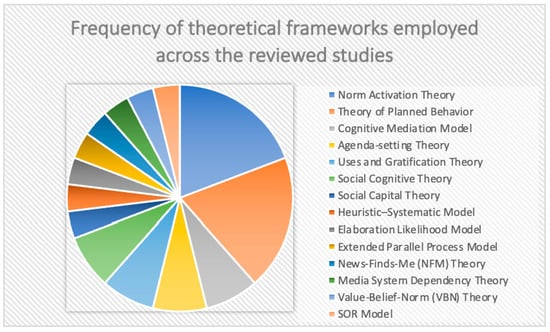

The theoretical frameworks and models used in the reviewed articles were identified and classified; details are reported in Table 3. More than half of the studies (54%) explicitly employed a theoretical framework or model. As shown in Figure 6, the most frequently used theories were the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and Norm Activation Theory (NAT), both commonly applied to explain pro-environmental behaviors such as waste sorting and low-carbon practices. Other recurrent frameworks included Social Cognitive Theory, Uses and Gratifications Theory (UGT), and Agenda-Setting Theory, typically used to examine how social media facilitates the dissemination of environmental protection information and user engagement. The Cognitive Mediation Model (CMM) was also employed to explain how media attention and information processing shape knowledge acquisition, risk perception, and policy support regarding environmental issues. Additionally, theories grounded in emotion and cognition, such as the stimulus–organism–response (SOR) model, the heuristic-systematic model (HSM), and the elaboration likelihood model (ELM), were employed to analyze information framing design and its persuasive effects.

Table 3.

Theoretical foundation or framework employed in the reviewed studies.

Figure 6.

Frequency of theoretical frameworks employed across the reviewed studies.

A smaller number of studies drew on Social Capital Theory, Media System Dependency Theory (MSDT), and News-Finds-Me (NFM). Overall, theoretical applications remain fragmented; however, a gradual shift toward dual-framework integration is evident (e.g., pairing behavioral and communication models), indicating movement toward conceptual consolidation in social-media-based environmental communication research.

3.4. Research Methods in Reviewed Studies

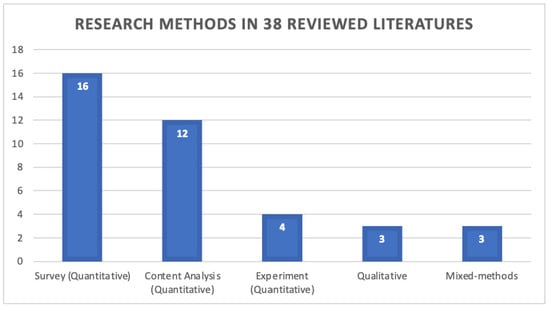

The reviewed studies demonstrate a strong dominance of quantitative approaches (see Table 4). As shown in Figure 7, the majority relied on survey questionnaires and content analysis, often aimed at measuring public perceptions, attitudes, and behavioral intentions toward environmental issues on social media. A smaller number of quantitative studies adopted experimental designs to test the effects of message framing, emotional appeals, or short-video features on pro-environmental behaviors. Overall, more than two-thirds of the reviewed literature applied quantitative methods, underscoring the field’s preference for structured, data-driven approaches.

Table 4.

Methods and platforms used in 38 reviewed studies.

Figure 7.

Research methods in 38 reviewed studies.

In contrast, qualitative studies were comparatively underrepresented. Only a limited number of articles employed ethnographic approaches, grounded theory, or discourse analysis to examine environmental NGOs’ strategies, government communication practices, or citizen mobilization on platforms such as Weibo and WeChat. These studies provide richer contextual insights but remain a minority within the overall body of literature. A few mixed-methods studies also appeared, integrating surveys with content analysis or combining textual data with experimental validation, reflecting early efforts to bridge methodological divides.

3.5. Social Media Platform in Reviewed Studies

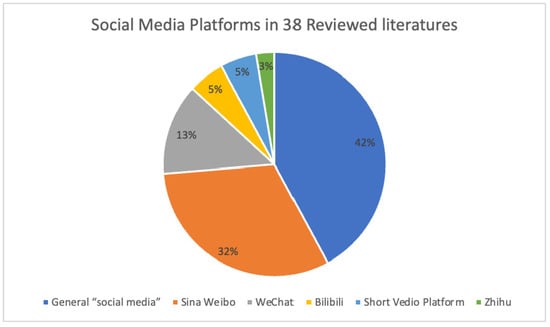

The reviewed studies covered a wide spectrum of social media platforms, reflecting the diversity of China’s digital ecosystem. As shown in Figure 8, Weibo and WeChat were the most frequently studied platforms, often serving as primary cases for examining environmental discourse, government messaging, or NGO mobilization. A smaller but growing number of studies focused on video platforms such as TikTok and Bilibili, highlighting their increasing relevance for visual storytelling and public engagement on environmental issues. In addition, niche platforms including Zhihu, QQ groups, and online forums occasionally appeared in studies of community dialogue and activism.

Figure 8.

Social Media Platforms in 38 Reviewed studies.

It is noteworthy that a subset of quantitative studies did not analyze any single platform directly but instead treated social media as a general construct. For example, some surveys assessed participants’ use of multiple platforms—such as WeChat, QQ, TikTok, Kuaishou, Douban, and Weibo—and created composite indices that represented aggregated social media usage. In these cases, social media were operationalized as a broad measure of digital communication rather than a platform-specific environment.

4. Discussion

Media are seen as a powerful instrument to deliver messages and information to the public [61]. Social media have become a key arena for environmental communication in China, shaping public awareness, participation, and issue visibility. This review synthesizes current research and discusses its main patterns across four dimensions—research themes, theoretical frameworks, methodological choices, and platform characteristics—to clarify how China’s digital media environment structures environmental communication.

4.1. Thematic Development

Topics 1 does not focus on specific groups of actors or analytical levels, but rather represents the context in which carbon-related issues are constructed, interpreted, and assessed.

At a macro level, Topics 3 and 6 reflect how China’s state-centric, hierarchically managed media system structures climate communication. Climate and environmental messages are tightly aligned with official priorities and the “dual carbon” agenda, with policy documents calling for the use of new media to promote low-carbon lifestyles and mobilize participation. Network and second-level agenda-setting studies on Weibo show that, despite growing engagement, climate discussions still cluster around a narrow group of institutional and celebrity accounts that define which issues and attributes become salient [12]. This helps explain why Topic 6 foregrounds agenda setters and visible communicators. Topic 3 complements this by showing how environmental NGOs and grassroots initiatives use the same platforms to extend, translate and sometimes cautiously contest official agendas. For example, by turning citizen pollution reporting into “embedded” forms of data activism within government-led campaigns. Social media thus operate simultaneously as channels for promoting national climate initiatives and as relatively constrained public arenas in which NGOs and ordinary users can supplement official discourse and surface specific environmental problems.

At the micro level, Topics 2 and 5 indicate a parallel shift toward governing climate issues through individual cognition and everyday lifestyle practices. Survey-based studies inspired by norm activation theory and related behavioral models conceptualize perceived risk, responsibility and moral norms as the main psychological pathways through which exposure to authoritative and social media translates into pro-environmental behavior. Cognitive mediation frameworks and elaboration likelihood model in areas such as waste sorting and “dual carbon” campaigns propose similar sequences linking media use, attention, elaboration and interpersonal discussion to knowledge, risk perception and policy support [35,42]. In this context, social media users are largely constructed as responsible citizens whose psychological distance, risk perceptions and perceived norms can be strategically adjusted through message design, rather than as political actors in environmental decision-making. This orientation is anchored in culturally specific assumptions, such as the moderating role of Zhongyong thinking [28] and gendered divisions of environmental labor that make women key targets of household waste-sorting campaigns [34].

Beyond macro agendas and micro-level psychology, Topic 4 captures issue-specific tensions around waste and incineration conflicts and civic mobilization. Since 2019, national guidelines and local regulations have been in place such as compulsory household waste sorting in major cities [62]. Studies use this setting to examine how social media shape willingness to sort waste, how government accounts mobilize participation and manage complaints, and how online debates around incinerator siting transform local NIMBY concerns into networked claims [48].

Finally, Topic 7 foregrounds the informational conditions under which climate communication occurs. International research shows that climate change is a paradigmatic domain of online misinformation, where misleading claims about climate science and policy circulate widely and can undermine support for mitigation [63]. Chinese studies on Weibo indicate that climate-related misinformation clusters around particular frames and vague authority references, whereas accurate posts more often cite clearly identifiable governmental or expert sources [60]. In summary, these seven themes collectively outline the basic landscape of communication in China’s current social media environment: on the one hand, it is deeply influenced by state-led media governance and a communication research orientation towards individual behavior; on the other hand, it is constantly being shaped and reorganized in specific policy practices such as waste management and in the game surrounding science and authority.

4.2. Theoretical Application

Environmental communication research, particularly in the Chinese context of social media, relies extensively on individual-level behavioral theories such as the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and Norm Activation Theory (NAT). Many studies model how social media use shapes attitudes, norms, and intentions in order to predict pro-environmental behavior, producing detailed accounts of cognitive pathways. This pattern is clearly reflected in our topic structure, where three major topics (T2 and T5) center on psychological distance, norms, and message processing. Critics argue that this individual-centric perspective is not neutral: by treating environmental problems primarily as deficits in awareness or motivation, research tends to assume that voluntary behavioral change is the main lever for sustainable development [64,65]. Citizens are constructed mainly as objects of persuasion, while other potential agents of change—public policy, media organizations, corporations, and collective movements—are pushed to the margins.

At the theoretical level, existing research generally lacks a cross-level analytical architecture that systematically links individual psychology, media systems, and social structures. Although studies of environmental communication in China occasionally draw on cross-level theories, they often compress these frameworks into a set of individual-level variables in empirical practice. Media system dependency (MSD) theory is a typical example: in Ball-Rokeach and DeFleur’s original formulation, MSD is a triadic theory that explains media effects through reciprocal dependencies among social systems, media systems, and audiences at the micro, meso, and macro levels [66]. However, in our corpus, empirical studies that invoke MSD or related concepts usually operationalize it only as individual “media dependence” or “informational media use”, and then insert this indicator as an explanatory variable into TPB- or NAT-type models to predict pro-environmental intentions [29]. In doing so, they effectively weaken the cross-level theoretical potential of MSD and reduce it to a micro-level psychological add-on. The future requires a reconstruction of the theoretical framework of environmental communication, viewing it not only as a matter of individual motivation but also as a relational and institutional process shaped by platform logic, policy guidance, and collective action.

4.3. Trends in Methodological Choices

Chinese-language scholarship on social media and environmental communication is dominated by quantitative designs, especially cross-sectional surveys and descriptive content analyses. This pattern is broadly consistent with international reviews of climate and environmental communication that identify content analysis, experiments, and surveys as the leading methodological avenues in the field, with relatively few mixed-methods or ethnographic studies [67]. In the Chinese case, however, this global tendency is further tightened around individual-level behavioral models: most surveys are explicitly designed to test TPB/NAT-type pathways from media exposure via attitudes, norms, and perceived control to pro-environmental intentions, while content analyses rarely go beyond counting frames, emotions, or call-to-action formats. Methodological choices thus reinforce the theoretical tilt diagnosed above: environmental problems are operationalized as deficits of awareness or motivation, and social media platforms are treated primarily as channels delivering persuasive messages to atomized individuals.

These methodological routines also shape what can and cannot be known about China’s social-media environmental communication. Survey-dominant approaches are well suited to estimate correlations between media use and self-reported behavior, but they are poorly equipped to analyze institutional dynamics, platform governance, or affective publics—phenomena that require longitudinal trace data, network analysis, or in-depth qualitative work. Likewise, descriptive content analysis and basic sentiment classification can map message frequencies on Weibo or WeChat, yet they seldom reconstruct how issues travel across platforms, how actor networks are structured, or how algorithmic curation and moderation policies condition visibility. In contrast, recent international work on climate-related communication increasingly combines computational text-as-data methods with ethnography, experiments, or stakeholder analysis to capture the socio-technical systems within which digital climate discourse unfolds. To advance in this direction, future research in China concerning social media and environmental communication should not only supplement survey content analysis procedures with longitudinal, web-based, and qualitative designs (such as digital ethnography, in-depth interviews, and case studies), but also broaden its sampling beyond adolescents and university students to include marginalized groups such as practitioners and affected communities.

4.4. Media Platforms

Our findings on platforms are closely linked to the survey-dominant methodological pattern identified above. In many quantitative studies, social media use is measured through one or two aggregate items (e.g., overall frequency of “social media” use), with WeChat, Weibo, TikTok and other platforms folded into a single composite variable. This operationalization fits the needs of individual-level cognitive–behavioral models, which require a simple media-input indicator, but it implicitly treats platforms as functionally equivalent channels of exposure rather than as distinct socio-technical environments. As a result, platform measures in much of the Chinese literature indicate how much respondents use social media, but tell us little about how specific platform architectures, governance arrangements or user cultures shape environmental communication.

Where platforms are distinguished, the distribution of research sites further narrows what we can know. Most empirical work in our corpus focused on Weibo, which combines an open, hashtag-driven interface with strong state and institutional presence and has become a key arena for what Yang et al. call “increasing yet constrained” public engagement around climate issues [46]. Studies of environmental NGOs similarly show how Weibo functions as a “networked public screen” on which image events and official campaigns are staged under conditions of managed visibility. In contrast, WeChat, central to everyday communication and community organizing, is largely operationalized as a generic news or chat source, even though work in communication studies has demonstrated how its semi-private groups, subscription accounts and censorship regimes produce a distinct “intimate public” where information sharing, self-censorship and low-key environmental talk are tightly intertwined. Short-video platforms introduce yet another logic: studies of TikTok show that its recommendation algorithm and entertainment-oriented culture tend to fragment public issues and repackage them as personalized, emotionally charged clips, blurring boundaries between public and private spheres and favoring apolitical or celebratory content [68]. Research on Bilibili highlights youth subcultures, damnum-based participation and platform campaigns that both enable creative engagement and embed it in platform and official agendas. However, these differentiated opportunity structures are only sporadically theorized in environmental communication studies, which means that Weibo-based analyses tend to be taken as proxies for “the public”, while the more intimate, affective and youth-oriented environmental publics that form on WeChat, TikTok and Bilibili remain under-explored.

Current treatments of platforms in the literature constrain our ability to analyze environmental communication as a genuinely cross-platform process in which algorithmic curation, state governance and user cultures jointly channel attention, emotion and mobilization. Recognizing platforms as differentiated but interconnected communicative regimes is therefore crucial if future research is to move beyond treating “social media” as a black box and to explain how China’s digital media ecology shapes the formation of environmental publics.

4.5. Research Gaps and Future Research Suggestions

Building on the thematic clusters (T1–T7), theoretical patterns, methodological trends, and platform analyses presented in this review, several substantive research gaps emerge that are not simply methodological shortcomings but reflect structural blind spots in current scholarship (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Research Gap and Future Study Suggestion in 38 reviewed studies.

First, existing studies treat governance structures, platform architectures, and individual cognition as separate analytical domains, whereas our synthesis shows that these levels operate as an integrated system shaping environmental communication. Future research should model the mechanisms linking macro-level visibility governance, meso-level platform logics and authority cues, and micro-level psychological processes. Such cross-level causal models would allow scholars to explain why specific message formats or emotional cues succeed or fail within China’s differentiated media environment.

Second, our review shows that different environmental topics consistently appear on different platforms—for example, policy-oriented and institutional agendas dominate Weibo, while emotional and narrative-based communication is concentrated on short-video platforms. However, existing studies rarely explain why these topic–platform patterns emerge or what mechanisms drive these differences. Comparative platform analysis should therefore move beyond treating “social media” as a unified construct and investigate how affordances, governance logics, and user cultures jointly shape which issues become visible, depoliticized, or emotionally amplified.

Third, our findings indicate that short-video platforms structure environmental communication through algorithmically curated formats—such as fragmented clips, interpersonal narratives, and personalized recommendations—yet existing studies rarely examine how these algorithmic mechanisms shape which types of environmental content gain visibility or engagement.

Fourth, NGO communication and grassroots mobilization remain structurally marginalized in both practice and scholarship. Research is needed to map the visibility mechanisms available to NGOs under different platform conditions, identify strategies that enable them to circumvent institutional constraints, and assess how platform-level gatekeeping affects the trajectories of environmental activism.

Finally, misinformation research in China has focused on linguistic patterns but not on the socio-technical pathways through which inaccurate or ambiguous content circulates. Future research should investigate authority-anchored misinformation models, the role of algorithmic amplification, and the interplay between vague authority cues and perceived credibility across platforms.

Together, these directions call for a research agenda that moves beyond individual-level behavioral models toward a multi-layered understanding of how environmental publics are shaped through the interaction of governance structures, platform architectures and communicative practices. A pragmatic sustainability perspective helps specify what such an agenda entails: it treats sustainability not as a fixed end-state or checklist of indicators but as an ongoing, context-sensitive process of collective problem solving, in which different actors negotiate acceptable trade-offs between environmental protection, social justice and economic development [69]. Rather than searching for a single optimal communication model, pragmatic approaches emphasize pluralism, experimentation and continual adjustment in response to social and ecological feedbacks. Applied to Chinese social-media research, this would mean shifting the focus from testing isolated behavioral predictors toward examining how concrete media practices and governance arrangements enable or constrain place-based environmental problem solving, civic environmentalism and institutional learning, thereby more explicitly linking everyday digital engagement to SDG-related targets on emission reduction, urban environmental governance and sustainable consumption.

5. Conclusions

This systematic literature review synthesized 38 peer-reviewed studies published between 2020 and 2024 that examined how social media mediate environmental communication in China. Using PRISMA 2020 procedures and a transparent coding strategy, it maps developments across four core dimensions—research themes, theoretical frameworks, methodological choices and media platforms—and a fifth, cross-cutting dimension of research gaps. The analysis identified seven thematic clusters that depict a field shaped by state-led visibility governance, a strong behavioral orientation and uneven attention to platform architectures and (mis)information. Weibo and WeChat dominated as research sites, while short-video and youth-oriented platforms such as TikTok and Bilibili are only beginning to be examined, indicating a gradual shift from descriptive, single-platform or individual-level studies toward more layered analyses of China’s platform-based media ecology.

This review makes three main contributions to environmental communication and sustainability research. First, it integrates a fragmented literature into a multi-level analytical lens linking macro-level media governance, meso-level platform architectures and micro-level psychological processes, and shows that work on agenda setting and NGO activism, misinformation and authority, and cognitive–behavioral pathways has largely evolved in parallel rather than in dialogue. Second, it demonstrates the dominance of individual-level models such as TPB and NAT and the relative neglect of relational, governance-oriented and cross-platform perspectives, which helps explain why citizens are often framed mainly as persuadable consumers and sustainable development is reduced to low-cost lifestyle adjustments rather than institutional accountability, data activism and collective mobilization. Third, by clarifying the potential and structural limits of digital media in promoting emission reduction, urban environmental governance and sustainable consumption, this review offers a multi-level framework to help policymakers, platforms and environmental organizations use different social media in more appropriate ways and link individual behavior change to broader sustainable development efforts, thereby contributing to the pragmatic realization of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly Sustainable Cities and Communities (SDG 11) and Climate Action (SDG 13).

This review also has limitations. The corpus is confined to English-language journal articles indexed in Web of Science and Scopus between 2020 and 2024, so Chinese-language publications and some comparative or cross-regional studies fell outside the scope of this review. The focus on empirical studies that explicitly named Chinese social media platforms further biases the sample toward platform-specific analyses. In addition, topic modeling was conducted on a relatively small set of 38 articles, so the seven-topic solution should be seen as a heuristic for structuring an emerging field rather than a definitive taxonomy, and most primary studies rely on cross-sectional surveys and descriptive content analyses, limiting causal inference and insight into long-term or offline outcomes. These constraints do not undermine the main patterns identified here but they indicate that future research should broaden database and language coverage, revisit the timeframe as new work appears, and complement quantitative synthesis with qualitative, longitudinal, and comparative designs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su172411057/s1, Table S1: PRISMA 2020 Checklist used for the systematic review in this study, Figure S1: Interactive visualization of the LDA topic model using pyLDAvis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: K.S. and M.A.A.; Methodology: K.S.; Validation: M.A.A.; Formal Analysis: K.S. and M.A.A.; Investigation: K.S. and M.A.A.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation: K.S.; Writing—Review and Editing: M.A.A. and K.S.; Visualization: K.S.; Supervision: M.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from publicly accessible bibliographic databases. Specifically, the data were obtained from Web of Science (Document Search—Web of Science Core Collection) and Scopus (Scopus—Homepage). Access to these databases may require a subscription or institutional login.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, B.; Siri, Z.; Haron, M.A. Threshold Effects of PM2.5 on Pension Contributions: A Fuzzy Regression Discontinuity Design and Machine Learning Approach. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G.; Iablonovski, G. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2025, 1st ed.; The Sustainable Development Goals Report; United Nations Research Institute for Social Development: New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, A.; Peterson, T.R. Rethinking Environmental Communication Scholarship. In Environmental Communication; Walter de Gruyter GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, P.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, R.; Lin, Z.; Lu, N. Social Media’s Impact on Environmental Awareness: A Marginal Treatment Effect Analysis of WeChat Usage in China. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Jia, R.; Razzaq, A.; Bao, Q. Social Network Platforms and Climate Change in China: Evidence from TikTok. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 200, 123197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A. Sustainability in Environmental Communication Research: Emerging Trends and Future Challenges. In The Sustainability Communication Reader; Weder, F., Krainer, L., Karmasin, M., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2021; pp. 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weder, F.; Karmasin, M.; Krainer, L.; Voci, D. Sustainability Communication as Critical Perspective in Media and Communication Studies—An Introduction. In The Sustainability Communication Reader; Weder, F., Krainer, L., Karmasin, M., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2021; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. Understanding China’s Changing Engagement in Global Climate Governance: A Struggle for Identity. Asia Eur. J. 2022, 20, 357–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Chung, D.; Zhang, A. The Effect of Social Media Environmental Information Exposure on the Intention to Participate in Pro-Environmental Behavior. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0294577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, X.; Schäfer, M.S. Multimodal Climate Change Communication on WeChat: Analyzing Visual/Textual Clusters on China’s Largest Social Media Platform. Clim. Change 2025, 178, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, C.; Lo, A.Y. Authoritarian Environmentalism 2.0: An Incremental Transition of Environmental Governance in China. Environ. Plan. C Polit. Space 2025, 43, 765–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Lu, Y.; Calabrese, C. Who Sets the Agenda for Climate Change in China? A Longitudinal Analysis of Primary Actors That Drive Online Discussions on Social Media. Environ. Commun. 2024, 18, 695–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, B.C.; Prodhan, T.R.; Alam, E.; Sohel, S.; Bari, A.B.M.M.; Pal, S.C.; Islam, K.; Islam, A.R.T. A Systematic Review of the Nexus between Climate Change and Social Media: Present Status, Trends, and Future Challenges. Front. Commun. 2024, 9, 1301400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, W.; Niederer, S.; Özkula, S.M.; Sánchez Querubín, N. The Social Media Life of Climate Change: Platforms, Publics, and Future Imaginaries. WIREs Clim. Change 2019, 10, e569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ktisti, E.; Hatzithomas, L.; Boutsouki, C. Green Advertising on Social Media: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Liu, W. A Tale of Two Databases: The Use of Web of Science and Scopus in Academic Papers. Scientometrics 2020, 123, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuhassna, H.; Alnawajha, S. Instructional Design Made Easy! Instructional Design Models, Categories, Frameworks, Educational Context, and Recommendations for Future Work. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2023, 13, 715–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köse, S.K.; Aydoğdu, G.; Demir, E.; Kiraz, M. Looking Backward toward the Future: A Bibliometric Analysis of the Last 40 Years of Meningioma Global Outcomes. Medicine 2024, 103, e39241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, R.; Singh, L. The Evolution of Topic Modeling. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 54, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, S.; Spruit, M. Full-Text or Abstract? Examining Topic Coherence Scores Using Latent Dirichlet Allocation. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Data Science and Advanced Analytics (DSAA), Tokyo, Japan, 19–21 October 2017; pp. 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.; Rachunok, B.; Flage, R.; Nateghi, R. Mapping Climate Discourse to Climate Opinion: An Approach for Augmenting Surveys with Social Media to Enhance Understandings of Climate Opinion in the United States. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, J.; Manning, C.D.; Heer, J. Termite: Visualization Techniques for Assessing Textual Topic Models. In Proceedings of the International Working Conference on Advanced Visual Interfaces; ACM: Capri Island Italy, 2012; pp. 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievert, C.; Shirley, K.E. LDAvis: A Method for Visualizing and Interpreting Topics. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Interactive Language Learning, Visualization, and Interfaces, Baltimore, MD, USA, 27 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Han, R.; Cheng, Y. The Influence of Norm Perception on Pro-Environmental Behavior: A Comparison between the Moderating Roles of Traditional Media and Social Media. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, X. Pro-Environmental Behavior Predicted by Media Exposure, SNS Involvement, and Cognitive and Normative Factors. Environ. Commun. 2021, 15, 954–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. An Investigation of the Influencing Factors of Chinese WeChat Users’ Environmental Information-Sharing Behavior Based on an Integrated Model of UGT, NAM, and TPB. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Li, D. Mind the Gap: How Zhongyong Thinking Affects the Effectiveness of Media Use on Pro-Environmental Behaviours in China. Environ. Commun. 2023, 17, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, N.; Chao, N.; Wang, C. Predicting the Intention of Sustainable Commuting among Chinese Commuters: The Role of Media and Morality. Environ. Commun. 2021, 15, 401–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J. More Is Not Always Better: The Role of Social Media Information in Shaping Individual Low-Carbon Behavioral Intention. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2024, 31, 639–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, Z. How Environmental Policy Perception and Social Media Use Impact Pro-Environmental Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Model Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, P.; Li, W.; Yang, W. Adolescents’ Social Media Use and Their Voluntary Garbage Sorting Intention: A Sequential Mediation Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, R.; Xu, J. A Comparative Study of the Role of Interpersonal Communication, Traditional Media and Social Media in Pro-Environmental Behavior: A China-Based Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zheng, W.; Fu, L. Examining Factors Influencing Public Knowledge, Risk Perception, and Policy Support for Waste Classification: A Multigroup Comparison of the Cognitive Mediation Model Based on Gender Differences. Environ. Commun. 2023, 17, 759–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Lei, L.; Chen, L. Text, Short Video, or Long Video? Effects of Attention to Various Types of Social Media on Public Knowledge of Dual Carbon: A Multigroup Comparison Based on Environmental Concern Levels. Environ. Commun. 2024, 18, 610–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Long, R.; Chen, H.; Wang, J. Is Social Media More Conducive to Climate Change Communication Behavior? The Mediating Role of Risk Perception and Environmental Values. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 26, 29401–29427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Chen, Q.; Ma, W.; Evans, R. Promoting Public Engagement with Household Waste Separation through Government Social Media: A Case Study of Shanghai. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 320, 115825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yue, X. A Study on the Mechanism of the Influence of Short Science Video Features on People’s Environmental Willingness in Social Media—Based on the SOR Model. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 990709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zheng, S.; Kaabar, M.K.A.; Yue, X.-G. Online or Offline? The Impact of Environmental Knowledge Acquisition on Environmental Behavior of Chinese Farmers Based on Social Capital Perspective. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 1052797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Skoric, M.M. Getting Their Voice Heard: Chinese Environmental NGO’s Weibo Activity and Information Sharing. Environ. Commun. 2020, 14, 844–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Chen, L.; Liu, S.; Tan, X.; Li, Y. Reconsidering the Effectiveness of Fear Appeals: An Experimental Study of Interactive Fear Messaging to Promote Positive Actions on Climate Change. J. Health Commun. 2024, 29, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, L. Message Presentation Is of Importance as Well: The Asymmetric Effects of Numeric and Verbal Presentation of Fear Appeal Messages in Promoting Waste Sorting. Environ. Commun. 2022, 16, 1059–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Luo, C.; Borah, P. Learning about Climate Change with Algorithmic News? A Two-Wave Panel Study Examining the Role of “News-Finds-Me” Perception. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2024, 29, zmae010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yu, B.; Dai, J. “Climate Change” or “Global Warming”? The (Un)Politicization of Climate in Chinese Social Media Platform. Environ. Commun. 2024, 18, 927–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z. More Than Just an Audience: The New Approach to Public Engagement with Climate Change Communication on Chinese Knowledge-Sharing Networks. Environ. Commun. 2022, 16, 757–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Stoddart, M.C.J. Public Engagement in Climate Communication on China’s Weibo: Network Structure and Information Flows. Polit. Gov. 2021, 9, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Huang, L. Fostering Opinion Leaders’ pro-Environmental Behaviour: Examining the Mediating Role of Social Media Expression and the Moderating Role of Mianzi. Asian J. Commun. 2024, 34, 638–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Anti-Incineration Mobilization on WeChat: Evidence from 12 WeChat Subscription Accounts. Environ. Commun. 2021, 15, 1061–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.; Karackattu, J.T. New Media Activism and Politics of Ecology in the People’s Republic of China. China Rep. 2022, 58, 390–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Hou, Y. COVID-19 Pandemic as an Opportunity or Challenge: Applying Psychological Distance Theory and the Co-Benefit Frame to Promote Public Support for Climate Change Mitigation on Social Media. Environ. Commun. 2024, 18, 550–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goron, C.; Bolsover, G. Engagement or Control? The Impact of the Chinese Environmental Protection Bureaus’ Burgeoning Online Presence in Local Environmental Governance. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2020, 63, 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Wang, Y. The Impact of Climate Change on Media Coverage of Sponge City Programs: A Text Mining and Machine Learning Analysis. Environ. Commun. 2023, 17, 518–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Huang, V.G. Embedded Data Activism: The Institutionalization of a Grassroots Environmental Data Initiative in China. Chin. J. Commun. 2022, 15, 115–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Hu, T.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, M. Exploring the Climate Change Discourse on Chinese Social Media and the Role of Social Bots. Asian J. Commun. 2024, 34, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, P.; Wang, L.; Liu, X.; Wei, Y. The Value of Social Media Tool for Monitoring and Evaluating Environment Policy Communication: A Case Study of the ‘Zero-Waste City’ Initiative in China. Energy Ecol. Environ. 2022, 7, 614–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, S.; Kuang, K.; Liu, S. Climate Communication with Chinese Youth by Chinese Nongovernmental Organizations: A Case Study of Chinese Weather Enthusiasts on Bilibili. Weather Clim. Soc. 2024, 16, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, H. Activating beyond Informing: Action-Oriented Utilization of WeChat by Chinese Environmental NGOs. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Cui, J.; Sun, C.; Li, J.; Li, B.; Guan, W. The Effects of the Type of Information Played in Environmentally Themed Short Videos on Social Media on People’s Willingness to Protect the Environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y. Civic Participation in Chinese Cyberpolitics: A Grounded Theory Approach of Para-Xylene Projects. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Ji, J. Characterizing the Semantic Features of Climate Change Misinformation on Chinese Social Media. Public Underst. Sci. 2023, 32, 845–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alivi, M.A.; Ghazali, A.H.A.; Tamam, E. Significant Effects of Online News on Vote Choice: A Review. Int. J. Web Based Communities 2018, 14, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Jiang, C. Local Nuances of Authoritarian Environmentalism: A Legislative Study on Household Solid Waste Sorting in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treen, K.M.; Williams, H.T.P.; O’Neill, S.J. Online Misinformation about Climate Change. WIREs Clim. Change 2020, 11, e665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniates, M.F. Individualization: Plant a Tree, Buy a Bike, Save the World? Glob. Environ. Polit. 2001, 1, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shove, E. Beyond the ABC: Climate Change Policy and Theories of Social Change. Environ. Plan. Econ. Space 2010, 42, 1273–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball-Rokeach, S.J.; DeFleur, M.L. A Dependency Model of Mass-Media Effects. Commun. Res. 1976, 3, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eise, J.; Lambert, N.J.; Adekunle, T.; Eversole, K.; Eise, L.; Murphy, M.; Sprouse, L. Climate Change Communication Research: A Systematic Review. SSRN Electron. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, N.A.H.M.; Ahmed, N.T.I. Is TikTok a Public Sphere for Democracy in Egypt? The Application of Habermas’s “Pseudo-Public Sphere”. Stud. Media Commun. 2025, 13, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.A. (Ed.) Pragmatic Sustainability: Theoretical and Practical Tools, 1st ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).