7.1. Study 1

A total of 122 individuals participated in the study; however, two questionnaire forms (less than 3% of the total sample) were deemed unsuitable for analysis because the majority of survey items were left unanswered. Thus, analyses were conducted based on data from 120 participants. Of the participants, 50.4% (n = 60) were male and 49.6% (n = 59) were female. Regarding marital status, 56% (n = 66) were single and 44% (n = 53) were married. In terms of educational attainment, 66% (n = 79) held a bachelor’s degree, 10% (n = 12) had an associate degree, another 10% (n = 12) completed secondary education, 9% (n = 11) held a master’s degree, and 4% (n = 5) had a doctorate. The average age of participants was approximately 32 years. Additionally, one participant did not respond to the gender and marital status items, while two participants left the educational status and age questions unanswered.

To assess participants’ awareness levels regarding the concept of neuroplasticity, three questions were administered. These questions were as follows: “Have you heard of the concept of neuroplasticity before?”, “Do you know what neuroplasticity means?”, and “Are you aware of the effects of neuroplasticity on working life?” Three participants did not respond to the first question, while four participants left the second and third questions unanswered.

Among the respondents, 66% (n = 79) stated that they had not heard of the concept of neuroplasticity before, whereas 34% (n = 41) indicated that they had. Furthermore, 73% (n = 88) reported that they did not know what the concept referred to, while 27% (n = 32) claimed they did. Additionally, 82% (n = 98) of the participants stated that they were not aware of the effects of neuroplasticity on working life, while 18% (n = 22) indicated that they had such awareness.

Following these questions on neuroplasticity awareness, participants were provided with a brief definition of the concept. In the survey note, neuroplasticity was defined as “the brain’s capacity to reorganize its structure and function in response to environmental stimuli such as new experiences, learning, or injuries.”

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, Cronbach’s alphas, and factor loadings for the items of the NLWLS.

Descriptive statistics regarding the NLWLS indicated that the overall mean score of the scale was below the midpoint (M = 1.86, SD = 1.08), suggesting that participants’ general neuroplasticity literacy and engagement in related behaviors are relatively limited. Similarly, both subdimensions—EB (M = 1.64, SD = 1.03) and DCR (M = 1.96, SD = 1.22)—also yielded means below the scale midpoint. These results indicate that participants rarely engage in cognitive EB and demonstrate minimal DCR behaviors, although some limited engagement in DCR was observed. Overall, the findings reflect relatively low levels of neuroplasticity-related awareness and behaviors compared to the potential scale range (

Table 1).

To examine the underlying factor structure of the NLWLS, an EFA was conducted on the Study 1 dataset (n = 120). The data were suitable for factor analysis, as indicated by the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy (KMO = 0.865) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (χ2 = 1119.504, df = 36, p < 0.001).

Principal Axis Factoring (PAF) was employed as the extraction method. An oblique rotation (Promax) was applied, given that the two subdimensions (EB and DCR) were expected to be correlated. Promax rotation is particularly appropriate for moderately sized samples and allows for correlated factors, providing a more accurate representation of the latent structure than orthogonal rotations.

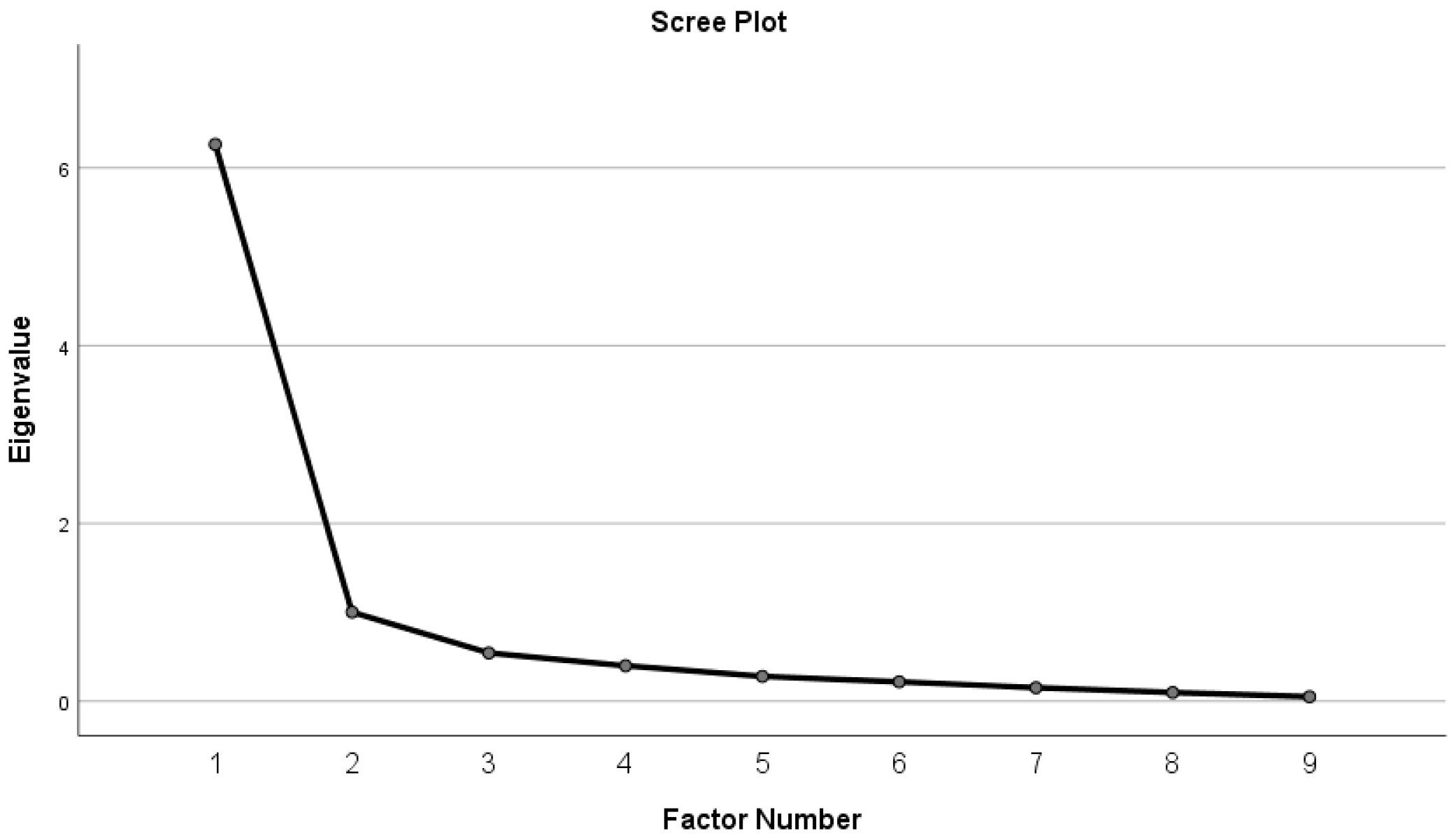

Communalities ranged from 0.558 to 0.924, indicating that all items shared sufficient variance with the extracted factors. The EFA revealed two factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 (Factor 1 = 6.042; Factor 2 = 0.789), explaining 75.90% of the cumulative variance. Pattern and structure matrices (

Table 1) show that all items loaded primarily on their respective factors, with cross-loadings examined and found to be minor relative to primary loadings, supporting the two-factor solution.

The factor structure is visually confirmed by the scree plot (

Figure 2), which shows a clear inflection point after the second factor, further supporting the two-factor solution. Pattern and structure matrices (

Table 1) show that all items loaded primarily on their respective factors, with cross-loadings examined and found to be minor relative to primary loadings, supporting the two-factor solution.

To further validate the factor structure, a parallel analysis with 100 randomly generated datasets was conducted. Only two factors had eigenvalues exceeding the 95th percentile of the random data (Factor 1 = 6.042 > 0.677; Factor 2 = 0.789 > 0.486), whereas subsequent factors did not exceed the random threshold, confirming the appropriateness of the two-dimensional solution (EB and DCR).

According to the reliability analysis, the overall Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the NLWLS was α = 0.95, indicating excellent internal consistency. At the subdimension level, the DCR subscale also demonstrated excellent reliability (α = 0.95), while the EB subscale showed good reliability (α = 0.87). All factor loadings for the scale items exceeded 0.70, indicating a high level of construct validity (

Table 1).

Item-level mean scores ranged from 1.53 to 2.09. This indicates that participants’ responses to the scale items were generally concentrated within the “low” range of agreement. Overall, the findings support that the NLWLS is a psychometrically reliable and structurally valid measurement instrument (

Table 1).

Table 2 presents the normality analysis.

The skewness and kurtosis values for the NLWLS and its subdimensions indicate that the dataset demonstrates statistically acceptable levels of normality. For the overall scale, the skewness coefficient was 1.01 and the kurtosis coefficient was −0.11. In the EB subdimension, the skewness was 1.68 and the kurtosis was 2.05, while in the DCR subdimension, the skewness was 0.95 and the kurtosis was −0.36 (

Table 2).

According to the reference range of ±2, all skewness and kurtosis values fall within acceptable limits. These results indicate that the data distribution conforms statistically to a normal distribution and support the applicability of factor analysis and other parametric tests for the scale.

7.2. Study 2

Within the scope of Study 2, a total of 164 individuals participated in the research. Among them, one participant did not respond to the question about marital status, two participants did not answer the education level question, and eight participants did not provide their age.

Among the participants, 59% (n = 96) were women and 41% (n = 68) were men. Regarding marital status, 53% (n = 86) of the participants were married and 47% (n = 78) were single. In terms of educational background, 67% (n = 109) held a bachelor’s degree, 17% (n = 28) had an associate degree, 9% (n = 15) completed secondary education, and 7% (n = 12) had a master’s degree. The average age of participants was approximately 31 years.

To assess participants’ awareness of the concept of neuroplasticity, three questions were posed: “Have you heard of the concept of neuroplasticity before?”, “Do you know what neuroplasticity means?”, and “Do you know the effects of neuroplasticity on working life?” Three participants did not respond to the first question, four did not respond to the second, and four did not respond to the third.

A total of 68% of participants (n = 111) stated that they had not heard of the concept of neuroplasticity before, while 32% (n = 53) reported that they had. Regarding the meaning of the concept, 71% (n = 117) indicated that they did not know what neuroplasticity referred to, whereas 29% (n = 47) claimed to be familiar with it. Additionally, 77% (n = 126) of participants stated that they were not aware of the effects of neuroplasticity on working life, while 23% (n = 38) reported being knowledgeable on the subject.

Following the awareness questions, a brief explanation of the concept of neuroplasticity was provided to participants. In the informative note included in the questionnaire, neuroplasticity was defined as “the brain’s capacity to reorganize its structure and function in response to environmental stimuli such as new experiences, learning, or damage.”

Table 3 presents the means, standard deviations, Cronbach’s alphas, and factor loadings for the items of the NLWLS.

Descriptive statistics for the NLWLS indicated that the overall mean score of the scale was low (M = 2.35, SD = 1.03). At the subdimension level, the EB subscale (M = 2.10, SD = 1.14) and the DCR subscale (M = 2.48, SD = 1.08) also exhibited similarly low mean values. These results suggest that participants’ engagement in or awareness of neuroplasticity-related activities is limited (

Table 3).

According to the reliability analysis, the overall Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the NLWLS was α = 0.93, indicating excellent internal consistency. Among the subdimensions, the DCR subscale demonstrated excellent reliability (α = 0.91), while the EB subscale showed good reliability (α = 0.89). The two-dimensional structure of the scale was maintained, and all items had factor loadings exceeding 0.70 (

Table 3).

All standardized factor loadings were significant and exceeded 0.70 (ranging from 0.769 to 0.989), and the item R

2 values ranged from 0.59 to 0.98. The two latent factors—EB and DCR—were strongly but not excessively correlated (r = 0.714), confirming their conceptual distinctiveness (

Table 3).

Item-level mean scores ranged from 2.05 to 2.68, indicating that participants’ responses to the scale items were generally concentrated within the “low” range of the 5-point Likert scale. Overall, these findings support that the NLWLS is a reliable measurement instrument with high internal consistency and a valid factor structure (

Table 3).

Table 4 presents the normality analysis.

The skewness and kurtosis values for the NLWLS and its subdimensions indicate that the data meet the assumption of normal distribution. For the overall scale, the skewness was 0.45 and the kurtosis was −0.63. In the EB subdimension, skewness was 0.71 and kurtosis −0.55, whereas in the DCR subdimension, skewness was 0.28 and kurtosis −0.78 (

Table 4).

All skewness and kurtosis values fall within the ±2 reference range, indicating that they are within acceptable limits. These findings suggest that the data distribution conforms statistically to a normal distribution and satisfies the necessary assumptions for factor analysis and other parametric tests.

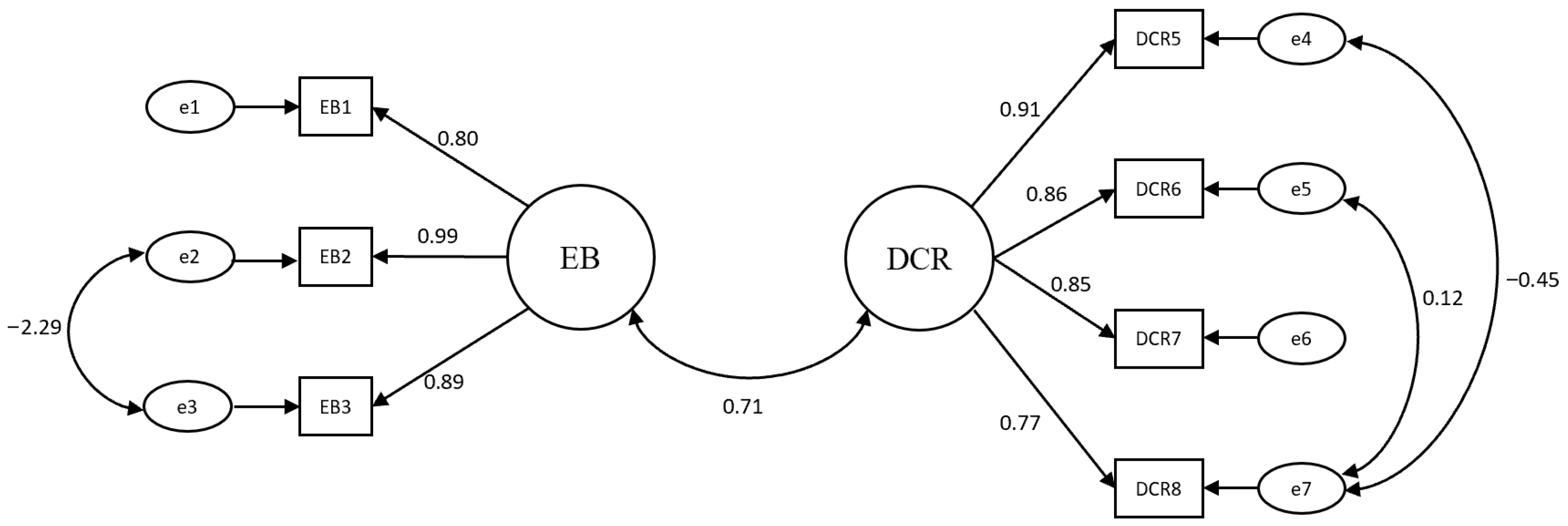

Figure 3 presents the CFA diagram.

Table 5 presents the CFA fit indices, convergent validity, and discriminant validity analyses.

To validate the factorial structure of the NLWLS, a CFA was conducted using robust maximum likelihood estimation with bootstrap correction, appropriate for ordinal five-point items with mild skewness. The analysis results indicated (

Table 5) that the hypothesized two-factor model demonstrated a good fit to the data (χ

2(10) = 17.894,

p = 0.057; CMIN/DF = 1.789; SRMR = 0.026; CFI = 0.991; IFI = 0.991; GFI = 0.971; TLI = 0.980; NFI = 0.979; RMSEA = 0.070).

Model comparison confirmed the superiority of the two-factor solution over a one-factor alternative (Δχ2(4) = 150.201, p < 0.001). Thus, a unidimensional structure could not adequately represent the data.

For the EB subdimension, AVE = 0.799, CR = 0.922, √AVE = 0.894; for DCR, AVE = 0.718, CR = 0.910, √AVE = 0.848. All AVE values exceeded 0.50 and CR values surpassed 0.70, indicating strong convergent validity [

47]. Additionally, the MSV and ASV values (0.510) were lower than the corresponding AVE values, supporting discriminant validity. Discriminant validity was further verified through the HTMT ratio (<0.85) and by inspecting standardized residual covariances (<0.30).

Although one item (EB2) displayed a very high standardized loading (0.989), the sensitivity analysis excluding this item yielded nearly identical fit indices, demonstrating the robustness of the model. Reliability indices were satisfactory, with all Composite Reliability (CR > 0.70) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE > 0.50) values exceeding recommended thresholds.

Overall, the CFA results confirmed that the two-factor NLWLS model exhibits excellent model fit as well as strong convergent and discriminant validity, providing empirical support for the scale’s psychometric soundness and theoretical structure.