Abstract

Young people in developing countries play a pivotal role in advancing sustainable practices; however, little is known about whether the psychological determinants behind their pro-environmental behaviors (PEBs) differ across developmental stages This study integrates the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) with environmental information exposure to explain young people’s PEBs and to examine their developmental heterogeneity, an aspect often overlooked in prior research. Using survey data from young people in Hue City, Vietnam (n = 995), we applied multigroup structural equation modeling to compare high school students, university students, and young workers. The integrated model explains 43.1% of the variance in PEBs. Intention is positively predicted by self-efficacy, subjective norm, attitude, and perceived vulnerability, and negatively predicted by reward and cost orientation. PEBs are directly predicted by intention, self-efficacy, and environmental information exposure. Subgroup contrasts reveal that response cost is negligible for high school students but a strong deterrent for older groups; self-efficacy directly predicts behavior only among university students and young workers; and environmental information exposure directly predicts behavior only among high school students. The findings underscore the importance of recognizing developmental heterogeneity among young people and suggest tailoring interventions to developmental stages, particularly in climate-vulnerable developing and emerging Asian contexts.

1. Introduction

Promoting pro-environmental behavior (PEB) has become a principal pathway for achieving sustainable development goals [1,2]. Young people play a pivotal role in driving this transformation because they are not only emerging consumers and voters but also the next generation of leaders and decision-makers [3,4,5]. Thus, developing a more thorough understanding of what motivates PEB among young people is crucial with practical applications for creating a sustainable future [1,6]. However, research and campaigns often implicitly treat young people as a homogeneous group, overlooking differences across developmental stages [7]. Despite sharing commonalities, cognitive and affective capacities vary across developmental stages, affecting their attitudes towards climate change and their daily PEB [8]. These differences reflect not only age but also shifts in resource control, social pressures, and dominant institutional contexts (school, university, workplace), which lead to distinct motivations and barriers [9,10]. Accordingly, this study aims to identify subgroup-specific drivers and barriers to inform targeted, effective policies and programs.

Young people’s PEB is jointly driven by individual attributes (e.g., gender, age, PBC, environmental literacy, attitudes, intentions, personal norms, connectedness with nature, climate-change concern), interpersonal influences (parents’ PEB, parent/peer communication, subjective and descriptive norms), and institutional/community engagement (participation in school or green activities and environmental clubs) [11,12]. However, several studies indicate subgroup differences among young people. High school students are predominantly shaped by family and school socialization, where subjective norms play a crucial role in influencing their intentions and actions [6,9,13]. By contrast, university students often face resource and time constraints that hinder follow-through despite favorable attitudes and environmental knowledge [9,10,14,15]. Although young people across various groups are exposed to environmental information via the internet and social media, university students typically receive additional exposure through formal coursework and university activities, while high school students often acquire little knowledge from school, and their practices often originate from family habits [9]. For young workers, financial independence presents both opportunities and challenges; they often face time pressures and the need for convenience. Their behavior is additionally shaped by workplace norms and organizational conditions [15,16,17]. In this context, perceived behavioral control and self-efficacy are vital for transforming intentions into PEB [10,14].

With this paper, we aim to contribute to the continuing need to understand this phenomenon by providing an additional understanding of the predictors of PEB of high school students, university students and young workers, drawing on the theory of planned behavior, protection motivation, and environmental information exposure. Specifically, we compare the relative salience of key drivers across subgroups, and test whether environmental information exposure exerts a direct effect on PEB.

Viet Nam offers a compelling setting for research on promoting PEB among young people. The country is highly exposed to climate risks while experiencing rapid economic growth, which together intensifies the need for effective societal responses [18,19]. Its large youth cohort provides both urgency and opportunity for scalable engagement, as documented by United Nations population statistics. Furthermore, at the 26th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, the Government of Viet Nam pledged to achieve net zero emissions by 2050 and has sought to learn from international experience in designing climate policies, which place a premium on public participation and the diffusion of everyday low-carbon practices.

In practice, youth engagement has been advanced through a variety of national and partner-supported initiatives, including the Youth Climate Action Network, the Youth4Climate Learning Hub, capacity-building programs (e.g., Movers, Training-of-Trainers), youth policy-participation events (e.g., Mock COP, Youth Statements at COY/Pre-COP/COP), innovation contests, and large-scale Youth Union campaigns [20]. At the high-school level, climate change education has been officially integrated into subjects such as Geography, Biology, Physics, Chemistry, Civic Education, Technology, etc., as well as extracurricular activities [21]. Several member universities have opened training programs in environmental protection at both undergraduate and graduate levels and have also incorporated some environment-related courses into the curricula of other disciplines [22]. For young workers, participation typically occurs through community and workplace initiatives, such as waste sorting, plastic reduction, and green commuting, often implemented via youth unions within enterprises or under corporate social responsibility programs. However, youth projects across various sectors are not practical because they all face common difficulties, including financial constraints, a lack of knowledge and skills, and inadequate facilities for implementing environmental protection actions. Many youth groups lack the resources to implement and sustain projects, while funding mechanisms often require legal status or advanced management skills that young teams rarely possess. At the same time, many participants, particularly outside formal education settings, report limited practical training in project design, financial planning, and policy engagement. Broader and more institutionalized training is still needed, including the integration of climate-related content into regular school and university curricula. These gaps highlight that current youth policies are not yet adequately equipped to ensure equitable and sustainable participation across all subgroups.

Hue City, recognized as Viet Nam’s first green city and an early pilot for sustainable development, provides a unique and suitable setting to explore subgroup differences in youth engagement. Hue has implemented a series of integrated, citywide initiatives, such as the Green Sunday movement, the Plastic Smart Cities program, and the Deposit–Return pilot, which engage high school students, university students, and young workers through shared participation channels [23,24,25]. The Youth Union system further coordinates environmental campaigns across schools, universities, public offices, and enterprises, ensuring consistent objectives and communication frameworks. These overlapping mechanisms create relatively uniform policy exposure to PEB-related activities among youth subgroups, allowing observed differences to primarily reflect intrinsic behavioral and psychological factors rather than policy disparity. However, while the overall policy messaging is consistent, workplace-specific capacity-building programs for young employees remain less institutional compared to those in the education sector. Therefore, this study investigates subgroup-specific determinants of PEB among high-school students, university students, and young workers in Hue City, aiming to identify how psychological, social, and contextual factors jointly shape their engagement within a shared policy environment.

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Integrating Models

Theory of Planned Behavior [26] posits that intention drives behaviors shaped by attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. The Protection Motivation Theory [27,28], PBC is highly compatible with the concept of self-efficacy, further strengthening the integration of TPB and PMT. Empirical studies support the effectiveness of integrating these two models, research on farmers [29] and rural residents [30].

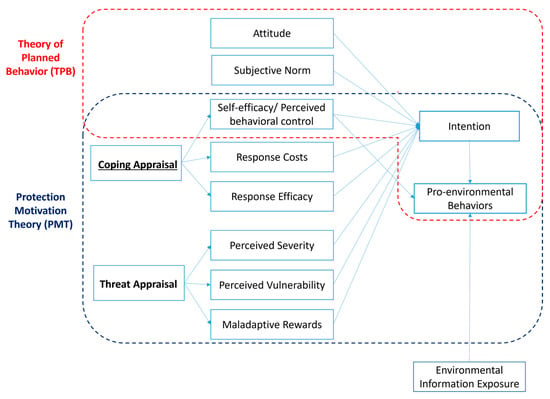

There are numerous previous studies that applied these models to high school and university students, excluding young workers under 30 years of age, indicating that the application of these theoretical models to predict PEBs is still limited in certain demographic groups and contexts [6,13,31,32,33,34]. Although TPB has been explored in high school and university populations, and PMT has been widely applied among university students, neither model has been utilized extensively to understand PEBs in the context of working young adults. This suggests that our understanding of how these models function across different life stages and educational and professional contexts is incomplete. This underscores the need for further research and model testing to fully comprehend how each theory can be best applied to different target audiences and to ensure that interventions are effectively tailored to each demographic group. Therefore, this study, to our knowledge, is among the first to merge the TPB and PMT to explore the determinants of PEBs among young people, focusing on those from diverse social backgrounds in developing countries (see Figure 1). In addition, exposure to environmental information has recently been considered a driving factor for PEB, so this study incorporated this factor into the combined model [35,36].

Figure 1.

Conceptual model shows the combination of the Protection Motivation Theory and the Theory of Planned Behavior.

2.2. Asian Studies and Research Questions

Across research on young people in emerging and developing Asian countries, the TPB has emerged as the most frequently adopted framework (Table 1). Within the TPB model, attitude and perceived behavioral control are generally found to be positive predictors of behavioral intention, particularly in countries such as India, Thailand, and China. However, these effects are not uniformly significant: attitude showed no effect in Iran and Bangladesh, while PBC was statistically non-significant in Malaysia. These inconsistencies suggest that individual-level evaluative beliefs and perceived agency may vary across socio-cultural contexts. In line with prior findings [37], the correlation can significantly vary based on culture. The impact of subjective norms also demonstrates considerable variation. While SN appears to have a positive influence on behavioral intentions in Indonesia, Malaysia, it was not significant in China, Vietnam or Bangladesh. These findings imply that the role of social pressure among youth may be contextually dependent, potentially shaped by differences in cultural collectivism, institutional engagement, or levels of environmental discourse in public education and media. Although TPB has been instrumental in explaining behavioral intention, the current literature demonstrates limited theoretical expansion beyond its core constructs. For example, only one study used PMT to assess additional psychological drivers such as perceived threat, cost, and reward. In the context of PMT, rewards are conceptualized as perceived benefits of not engaging in pro-environmental behavior, such as convenience or time-saving. These rewards represent part of the maladaptive response appraisal, which may reduce pro-environmental intention by making environmentally harmful choices seem more personally advantageous.

Furthermore, recent studies have shown that environmental information obtained through digital or traditional media, as well as through interpersonal and community sources such as parents, peers, and school or youth organizations, can directly or indirectly promote intentions or PEBs [38,39,40]. However, information-related constructs, particularly environmental information exposure (EIE)—remain underexamined among young people. To date, only two studies in China and Indonesia examined EIE in the context of young people in Asia [39,40], finding it to be a significant positive predictor of intention or behavior. Therefore, this study aims to explore additional factors from PMT and information-related constructions to predict pro-environmental behavior in young people better.

Based on the theoretical specifications of TPB and PMT, attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (or self-efficacy) are expected to exert positive effects on intention. PMT further predicts positive effects of response efficacy, self-efficacy, perceived severity, and perceived vulnerability, alongside negative effects of response costs and maladaptive rewards. Environmental information exposure is also expected to have a positive influence on pro-environmental behavioral outcomes. These expected impact directions are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Impacts of factors on intention or behavior by the original models, and studies in Asian developing and emerging countries.

Table 1.

Impacts of factors on intention or behavior by the original models, and studies in Asian developing and emerging countries.

| Authors | Country | Theory | AT | SN | PBC/SE | RE | Co | PS | PV | Re | EIE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPB | - | TPB | + | + | + | na | na | na | na | na | na |

| PMT | - | PMT | na | na | + | + | − | + | + | − | na |

| [41] | Malaysia | TPB | + | + | n.s. | na | na | na | na | na | na |

| [40] | Indonesia | TPB | na | + | na | na | na | na | na | na | + |

| [42] | Thailand | TPB | + | + | + | na | na | na | na | na | na |

| [32] | Iran | PMT | n.s. | na | + | n.s | − | n.s | n.s | − | na |

| [43] | Vietnam | TPB | + | n.s | na | na | − | na | na | na | na |

| [31] | India | TPB | + | + | + | na | na | na | na | na | na |

| [44] | Bangladesh | TPB + NAM | n.s. | n.s. | + | na | na | na | na | na | na |

| [39] | China | TPB | + | na | na | na | na | na | na | na | + |

| [45] | China | TPB | + | n.s. | + | na | na | na | na | na | na |

| Our hypothesis based on previous studies | - | TPB + PMT | + | + | + | + * | − | + * | + * | − | + |

Notes: AT, Attitude; SN, Subjective Norm; PBC, Perceived Behavioral Control; PS, Perceived Severity; PV, Perceived Vulnerability; Re, Rewards; SE, Self-Efficacy; RE, Response Efficacy; Co, Response Costs; +, positive correlation; −, negative correlation; n.s., not significant; “na” = not included in the model. * shows that the prediction is due to the original model.

Research questions are proposed:

- RQ1: To what extent do TPB constructs—attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control—predict pro-environmental behavioral intention among young people in emerging and developing Asian countries?

- RQ2: How do PMT-related variables—perceived threat, cost, and reward of maladaptive responses—influence pro-environmental behavioral intention in this context?

- RQ3: What is the effect of environmental information exposure on young people’s intention to engage in pro-environmental behavior?

3. Methods

3.1. Sample

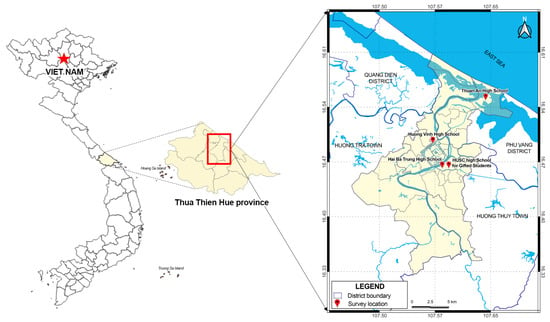

To test the conceptual model illustrated in Figure 1, data were collected from Hue City in the Thua Thien Hue Province, Vietnam. Thua Thien Hue Province is situated in central Vietnam (16° N and 108° E) and is bordered to the east and west by the South China Sea and Laos, respectively. The province has an area of 5060 km2 and is subdivided into nine administrative districts, including Hue City (Figure 2). The estimated population for 2023 was approximately 1,160,000 with a total workforce of 625,127 individuals aged ≥15 years (People’s Committee). Owing to its tropical location and unique topography, frequent severe weather events such as storms, floods, droughts, and hot and dry winds occur annually, and the province is regarded as one of the most disaster-prone regions in Vietnam [46]. In addition, Thua Thien Hue faces challenges related to economic development, unsustainable resource utilization, and population growth, necessitating comprehensive disaster risk management programmers in the context of climate change [47]

Figure 2.

Map showing the survey area and targeted schools.

Table 2 summarizes our samples. The questionnaire was pretested before the primary survey and modified accordingly. The main survey began in February and ended in late April 2024. Self-reporting questionnaires were distributed in the high schools and departments of Hue University of Science. Regarding young workers, an online survey was conducted among those aged 15–30 years who lived or worked in Hue City. To mitigate the possibility of common method variance, we adhered to the guidelines suggested by Podsakoff et al. [48] to ensure that data for all the variables in our theoretical model were collected using the same measurement instrument. A total of 1018 responses were collected, of which 995 valid cases were included in the analysis. 23 cases with substantial missing data on key variables were excluded.

Table 2.

Collected sample.

We created this map using QGIS version 3.28 and a base map from HCMGIS (QGIS Python Plugins Repository) https://plugins.qgis.org/plugins/HCMGIS/ accessed on 2 November 2025. Map lines delineate the study areas and do not necessarily depict accepted national boundaries.

3.2. Measures

The questionnaire consisted of three sections: demographics and socioeconomic background; environmental and climate engagement; environmental information and constructs from the TPB and PMT, assessed using validated five-point scales (strongly disagree to strongly agree) (see Appendix A). Items with low factor loadings were excluded.

Pro-environmental behavior (PEB) refers to actions of individuals to minimize environmental harm or actively help restore the natural environment. Ref. [49] developed an 18-item environmental action scale based on a pre-test of a sample of international students from six different countries and a sample of prominent environmental activists. This scale has demonstrated good reliability, provides a valid measure of the level of participation in environmental actions, and has been applied in subsequent studies. To construct a scale appropriate for young people, an additional six personal activities were included [5]. In the present study, we identified ecologically friendly behaviors and modified them to better fit the Vietnamese culture and youth

Using a recommended two-step approach [50] we first performed a confirmatory factor analysis and validated our measurements. The measurement model converged with an acceptable fit [51] with χ2 = 1088.8, degrees of freedom [df] = 468, comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.947, goodness of fit index (GFI) = 0.936, Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) = 0.937, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.037, and standardized root mean squared residual (RMSR) = 0.032. Table 3 lists the evidence for the validity and reliability of the measures used. All measurement scales were reliable as most composite reliability (CR) coefficients exceeded the threshold of 0.7; however, some values of these indexes were low but still acceptable [4,52]. Convergent validity was supported because most average variance extracted (AVE) values were above 0.50, and those slightly below this level were still considered acceptable given their CR values exceeded 0.60, consistent with Fornell and Larcker’s (1981) criteria [53]. Discriminant validity was also achieved, as all AVE values were greater than the corresponding maximum shared variances (MSVs) [53].

Table 3.

Construct reliability and convergent/discriminate validity.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

The software SPSS (version 27.0) was used to analyze the primary data using descriptive statistics, independent t-tests, chi-square tests, Cronbach’s alpha, exploratory factor analysis (EFA), and multicollinearity diagnostics through the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). A multicollinearity check was performed prior to Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to ensure predictor independence. We proceeded with SEM analysis using AMOS software (version 24) to analyze the interrelationships among the latent variables. First, we conducted multigroup analysis to identify the similarities and differences in the model structure across the three groups and then examined the similarities and differences in individual structural weights across the groups. Throughout this study, we used the 5% level as the criterion for statistical significance.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Sample Information

Females accounted for 52.3% of the study population and the mean age was 18 years (SD = 3.2). The respondent sample predominantly comprised individuals with a high level of education, and none reported having less than a high school diploma (Table 4). The percentage of individuals who participated in courses, seminars, and workshops in the environmental field was notably high (39.5%). This ratio for university students reached 44.7%; currently, general environmental education is mandated as a required course for all students at Hue University of Science. The involvement rate in environmental or climate change organizations was notably low, at 7.1% across 995 samples.

Table 4.

Personal attributes of the respondents.

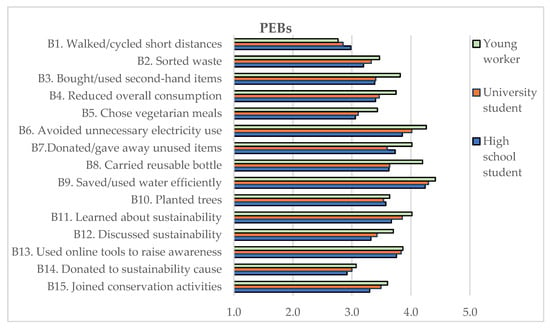

4.2. PEBs in the Three Groups

Figure 3 summarizes how often young people engage in PEBs (always, often, sometimes, rarely, or never). Overall, working individuals appear to practice PEBs more frequently than students. A one-way ANOVA comparing PEBs among the three pairs of groups (high school students-university students, high school students-young workers, and university students-young workers) showed that young workers (mean = 3.74) scored significantly higher than both high school students (mean = 3.47, p < 0.001) and university students (mean = 3.52, p < 0.01), whereas high school and university students did not differ (p > 0.05). As presented in Table 5, suburban high school students practiced more PEBs than urban students. Among university students, no difference was found in PEBs between study majors; however, females reported more PEBs than males. Young workers showed no significant differences in PEBs according to the field of work or sex.

Figure 3.

Pro-environmental behaviors.

Table 5.

Pro-environmental behaviors across three groups.

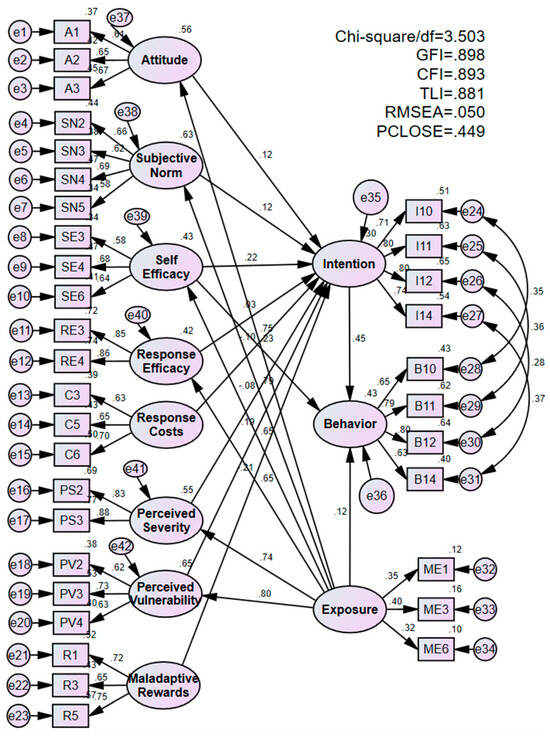

4.3. SEM Analysis of the Pooled Sample

The structural model described in Figure 1 was estimated for the pooled sample and yielded acceptable fit indicators. The results show that all the resultant fit indices met the acceptance levels (χ2/df = 3.503; GFI = 0.900; CFI = 0.900; TLI = 0.881; RMSEA = 0.050, SRMR = 0.070) [51] (Figure 4). These statistics revealed a good model approximation of the sample data. A multicollinearity check was performed prior to the SEM analysis to ensure independence among predictors. All VIF values ranged from 1.107 to 1.634, which is well below the commonly accepted threshold of 3.3 [54]. We also inspected the correlation matrix among the TPB/PMT constructs; inter-construct correlations ranged from 0.00 to 0.51 and were all below the 0.80 threshold that is commonly used to indicate problematic multicollinearity.

Figure 4.

Standardized path diagram of the structural model (pooled sample).

For intention, self-efficacy, perceived vulnerability, and attitude all show significant positive effects (Table 6). Subjective norms exhibit a marginally significant positive influence (p = 0.052), suggesting a weak yet noticeable social effect in this sample. Response costs and maladaptive rewards both exhibit apparent negative effects on intention, whereas response efficacy and perceived severity do not demonstrate significant contributions to this effect. For actual pro-environmental behavior, intention and self-efficacy remain strong positive predictors, and environmental information exposure also shows a direct and significant effect. These findings reflect the general pattern of relationships observed in the pooled youth sample. Overall, most of the relationships expected based on previous TPB and PMT studies (as summarized in the last line of Table 1) are also observed in the pooled sample. These include the positive effects of self-efficacy, perceived vulnerability, subjective norms, and attitude on intention, as well as the negative effects of response costs and maladaptive rewards. This alignment with theoretical expectations strengthens the validity of our integrated model. However, response efficacy followed the theorized positive direction but remained non-significant and perceived severity, which is expected to be positive, was instead negative and non-significant.

Table 6.

Results of hypothesis testing.

4.4. Comparison of Structural Models Among the Three Groups

We conducted a multigroup structural model analysis of the three groups. The chi-square difference test results indicate no significant difference between the Measurement Weight Constrained Model, which assumed the same measurement weights across the three groups, and the Unconstrained Model (Δχ2Δd.f.=34 = 51.430; p = 0.270), suggesting measurement invariance. Δχ2 (delta chi-square) represents the change in the chi-square statistic between two nested models, assessing whether imposing additional constraints significantly worsens model fit. Similarly, Δd.f. (delta degrees of freedom) indicates the difference in degrees of freedom between the two models compared.

We imposed equal constraints on both the measurement and structural weights across the three groups. This is called a Structural Weight Constrained Model. The difference between this model and the Unconstrained Model was Δχ2Δd.f.=80 = 101.754 and p = 0.051, which was marginally non-significant, suggesting that the structural weights are nearly invariant across the three groups. To further investigate potential group differences, two separate comparisons were made. The first compared high school and university students pooled together against young workers, while the second compared high school students against a combined sample of university students and young workers. The first comparison between Structural Weight Constrained and Unconstrained Models revealed no significant differences (Δχ2Δd.f.=40 = 49.535; p = 0.144). In the second comparison, while the equality of the measurement weights was accepted as Δχ2Δd.f.=23 = 27.075 and p = 0.253, a significant difference was found between the Structural Weight Constrained and Unconstrained Models (Δχ2Δd.f.=40 = 58.715; p = 0.028). This indicates structural weight differences between high school students and the combined sample of university students and young workers.

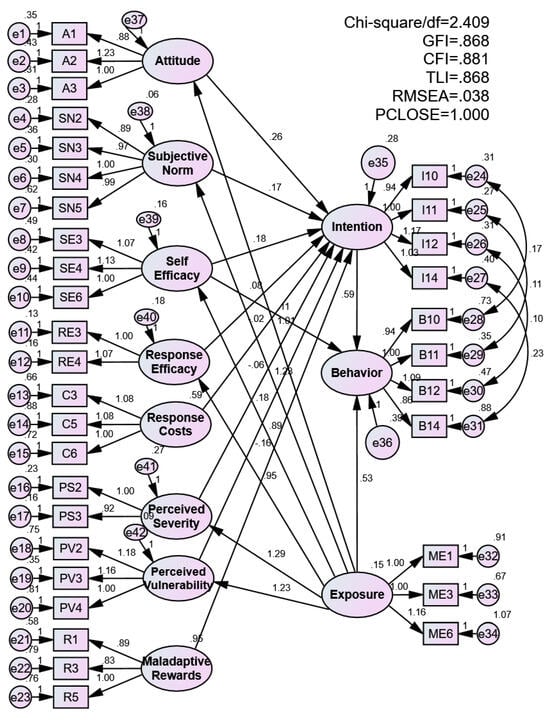

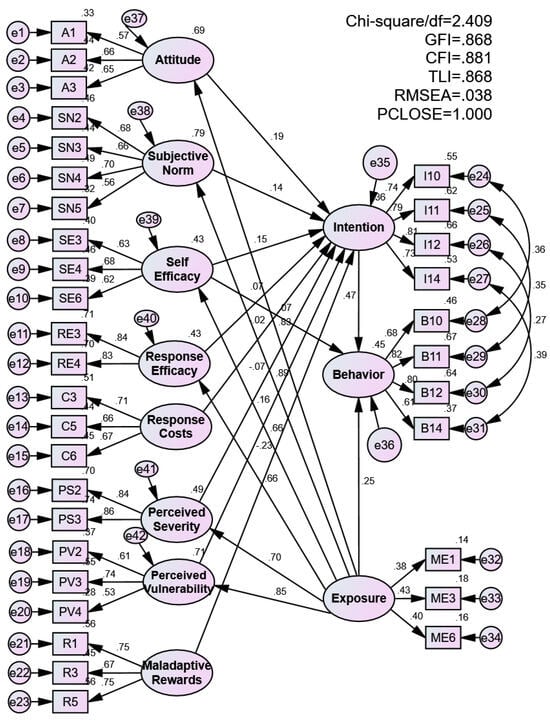

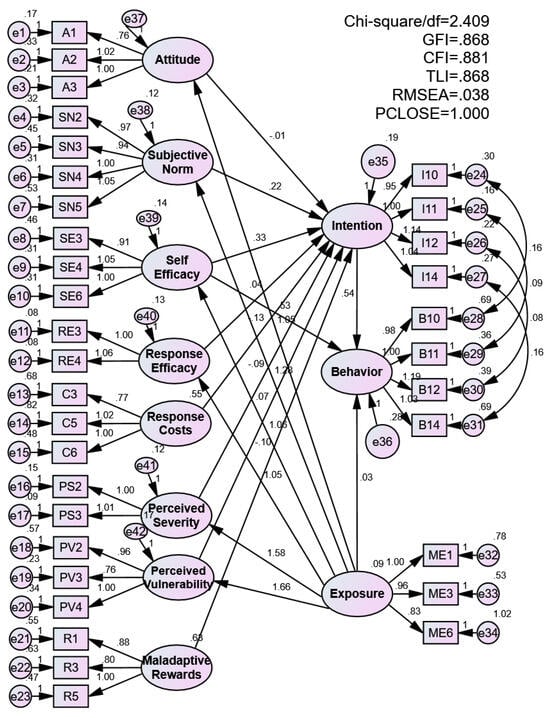

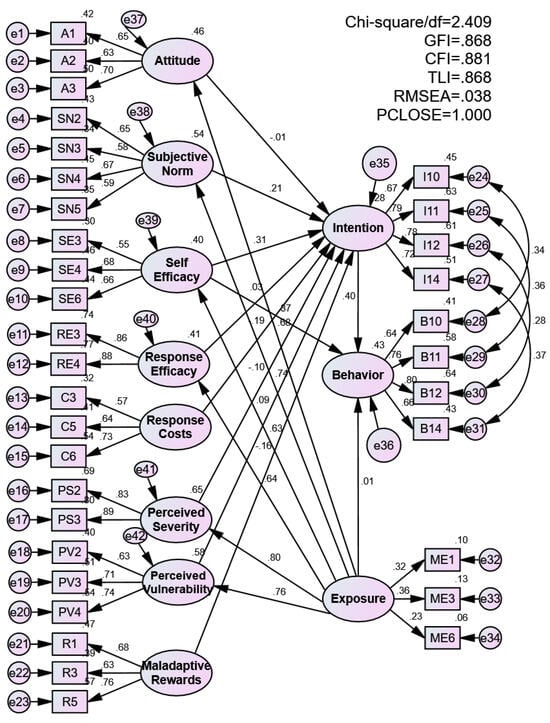

We further examined which structural paths differed between the two joint groups—high school students versus the combined sample of university students and young workers. The results revealed that the structural weight of the Self-efficacy → Behavior path was significantly different between the two groups (p = 0.009), as were the Exposure → Behavior (p = 0.041) and Cost → Intention (p = 0.029) paths. Figure 4 presents the estimated final model. This model achieved an acceptable fit to the data (χ2/d.f. = 2.409, GFI = 0.868, RMSEA = 0.038) [55].

The final model’s structural weights were examined to test the relationships between psychological determinants and pro-environmental intentions and behaviors. Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8 illustrate the estimated paths, and Table 7 summarizes the results.

Figure 5.

Final model estimates for high school students (unstandardized results).

Figure 6.

Final model estimates for high school students (standardized results).

Figure 7.

Final model estimates for university students and young workers (unstandardized results).

Figure 8.

Final model estimates for university students and young workers (standardized results).

Table 7.

Comparison of high school students and others.

For the high-school student group, significant predictors of Intention included Self-efficacy (B = 0.27, p < 0.001), Subjective Norm (B = 0.21, p < 0.01), and Rewards (B = −0.11, p < 0.001). In addition, Intention → Behavior (B = 0.58, p < 0.001) and Exposure → Behavior (B = 0.50, p < 0.01) were significant, indicating that motivational, social, and experiential factors strongly promote PEB among students.

For the combined group of university students and young workers, Rewards → Intention (B = −0.11, p < 0.001), Subjective Norm → Intention (B = 0.21, p < 0.05), and Cost → Intention (B = −0.17, p < 0.001) significantly predicted Intention, while Self-efficacy → Behavior (B = 0.52, p < 0.001) and Intention → Behavior (B = 0.58, p < 0.001) significantly predicted actual behavior. These findings suggest that, for adults, social influence, external rewards, and perceived costs shape intentions, whereas self-efficacy plays a central role in behavioral execution.

Across both groups, Rewards → Intention, Subjective Norm → Intention, and Intention → Behavior were consistently significant and did not differ significantly between groups, highlighting shared motivational mechanisms. In contrast, Severity → Intention (B = –0.08, ns), Vulnerability → Intention (B = 0.12, ns), Response Efficacy → Intention (B = 0.05, ns), and Attitude → Intention (B = 0.06, ns) were non-significant in both samples. Comparative analyses further revealed significant group differences in three relationships: Cost → Intention (p = 0.029), Self-efficacy → Behavior (p = 0.009), and Exposure → Behavior (p = 0.041). These results indicate that perceived cost, personal efficacy, and prior experience operate differently between adolescents and young adults, reflecting distinct psychological mechanisms underlying their pro-environmental engagement.

Several predictors were non-significant in the subgroup models, including attitude, response efficacy, perceived severity, and perceived vulnerability for intention in both high-school students and university students/workers; response costs for high-school students; self-efficacy for behavior among high-school students; and environmental information exposure for behavior among university students and workers. For most of these non-significant predictors, the coefficient signs were consistent with those in the pooled sample, indicating that the general motivational pattern is preserved across groups. However, perceived severity displayed a consistently negative sign in both the pooled and subgroup models, which contradicts the positive direction typically predicted by PMT.

4.5. Potential Differences Between University Students and Workers

Since high-school students are different from the university student-worker group, we examine the potential difference between university students and workers (Table 8). The structural weight invariance test indicated that the structural paths did not significantly differ between university students and workers (p = 0.449), suggesting that the hypothesized relationships are statistically equivalent across the two groups. However, we need to consider the small sample size of the workers. Thus, we intentionally removed the structural weight equivalence constraints and saw the magnitude of the structural weight differences between the two groups.

Table 8.

Comparison of university students and young workers.

As a hint for potential university student-worker differences, we examined variables that were statistically significant at least for one group and had a large relative absolute size. Then Response Costs → Intention coefficient of university students is 4.9 times larger than that of workers. This difference may become statistically significant once we obtain a larger sample of workers. Other relationships did not draw our attention.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to integrate the TPB and the PMT to identify the barriers and motivators of PEBs among young people and to examine whether exposure to environmental information directly influences these behaviors. The results showed that the model explained 43% of the variance in PEBs. This study demonstrates that although young people share similar psychological foundations of pro-environmental intention, their behavioral pathways differ significantly. For both groups, self-efficacy and subjective norms are the primary drivers of intention, while rewards serve as a barrier to intention to do PEB. However, high school students respond more strongly to environmental information exposure, reflecting emotional and experiential engagement. In contrast, university students and young workers tend to behave more pragmatically, as perceived costs and self-efficacy influence their actions in real-life contexts.

The findings of this study align with previous work in Asian developing and emerging countries in showing that attitudes towards PEB, social influence, and perceived control are central drivers of pro-environmental motivation among young people (Table 9). Similar to studies in India, Thailand and China that applied the TPB and reported positive effects of attitude, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control on intention [31,42,45], our results indicate that attitude, subjective norms and self-efficacy significantly increase intention in high school students as well as in university students and young workers. This pattern reinforces the view that youth PEB in the region is shaped not only by pro-environmental attitudes but also by strong social expectations and perceived personal capability. In line with PMT evidence from Iran, perceived severity and response efficacy do not significantly predicts intention, indicating that threat-related cognitions alone are insufficient to motivate everyday pro-environmental behaviors among young people [32]. This is different from several previous studies on young people that reported positive effects of perceived severity and response efficacy on intention [33,34,56]. Zhao’s study provides a possible explanation for this pattern. This study found that the influence of perceived severity and response efficacy varies depending on both the type of behavior and the socioeconomic context of respondents. For low-cost behaviors (such as reducing water and electricity use, cutting down on waste, or lowering everyday consumption), perceiving environmental problems as severe can strengthen intention because these actions require minimal financial resources. In contrast, for high-cost behaviors (like recycling or choosing more expensive green products), severity does not predict intention, as individuals may recognize the seriousness of the issue but still lack the financial means to act [57]. Another explanation is that environmental issues are often perceived as collective problems. Young people may form strong pro-environmental intentions only when they believe in collective efficacy and perceive support from their social group, rather than relying solely on the belief that a single action is effective or beneficial [58,59]. Given that many young people have unstable or limited income, these mechanisms help clarify why perceived severity and response efficacy are relatively weak predictors of intention in our study.

Table 9.

Comparison of this study with previous studies in Asian developing and emerging countries.

At the same time, our results differ from some prior studies in two important respects. First, response cost is a salient barrier for university students and young workers but not for high school students, indicating that young adults act as practically constrained decision makers who weigh time and money, a pattern seldom modeled explicitly in prior regional work that focused on attitudes, norms, and efficacy [31,41,42,45]. These findings align with evidence from Hungary that directly compares high school and university students. High school students tend to report greater freedom in day-to-day spending, while university students experience tighter budget constraints, likely reflecting the transition from family-supported consumption to partial financial independence during university [9]. Second, self-efficacy directly predicts behavior only among university students and young workers. These groups typically possess higher personal autonomy, financial independence, and practical experience, enabling them to translate perceived capability into concrete PEBs [10,14]. In contrast, high school students have limited decision-making power; their environmental protection behavior is often influenced by family habits [9], and lack the situational opportunities necessary to enact environmental behaviors. The results also reflect situations where students believe they can engage in activities to reduce environmental harm, only to encounter later barriers or constraints that prevent them from taking action [60,61]. Third, environmental information exposure directly predicts behavior among high school students but has a negligible effect on older youth. The direct effect of information exposure on behavior was significant only among high school students, likely because this group has limited prior knowledge and relies more heavily on external cues to shape their environmental actions, in line with research showing that students lack the information to practice environmental protection behaviors [9]. For university students and young workers, existing knowledge and established behavioral routines may reduce the direct influence of informational stimuli, making exposure insufficient to drive immediate behavioral change. Studies in Indonesia have acknowledged the importance of information and awareness, yet they have rarely tested exposure as a direct behavioral driver. Our results clarify that exposure is behaviorally consequential for younger adolescents.

In summary, the Vietnamese evidence replicates regional regularities reported in Malaysia, Thailand, China, and India namely that intention is shaped by attitude, social expectations and self-efficacy, and that intention drives behavior. At the same time, it reveals heterogeneity within the youth population that earlier studies did not capture. High school students in Vietnam resemble the social norm-responsive youth described in Southeast Asian TPB studies, whereas university students and young workers behave more like economically constrained decision makers for whom perceived cost is a barrier and self-efficacy is a prerequisite for converting intention into action. The regional implication is that interventions for adolescents should emphasize experiential and community-based programs and social reinforcement, while interventions for older youth should prioritize cost reduction, convenience, and capacity building.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

Theoretically, this study advances an integrated account of youth pro-environmental behavior by combining the Theory of Planned Behavior and Protection Motivation Theory with climate-change information exposure in a single framework. Consistent with these traditions, intention remains the primary pathway to behavior, while coping-related and social–cognitive drivers dominate the formation of intention. Across subgroups, self-efficacy and subjective norm reliably increase intention, while rewards orientation consistently reduces it; perceived cost emerges as a salient deterrent among university students and young workers but is negligible for high school students. By contrast, attitude, response efficacy, and the PMT threat appraisals of perceived severity and perceived vulnerability show no unique association with intention once other drivers are included. Information exposure directly predicts behavior among adolescents but not among older youth without enabling conditions, indicating a stage-contingent role for information. The multi-group results underscore developmental and contextual boundaries: the transition from schooling to employment alters the salience of costs and the direct effect of self-efficacy on behavior. Prior work typically examines students or workers separately and seldom theorizes this transition, despite emerging evidence suggesting that employees increasingly integrate environmental concern with workplace engagement [17,62]. These findings motivate an experience-integrated and age-sensitive refinement of TPB/PMT that treats developmental stage and role-based identity as systematic moderators of intention formation and intention enactment in young people.

5.2. Practical Implications

Regional implications for Asia and climate-vulnerable developing countries. In settings where youth live with recurrent floods, heat, and pollution, interventions should pair experiential, community-based programs for adolescents with cost- and feasibility-oriented policies for older youth. For secondary schools, embed disaster and climate education into the timetable, run regular field projects in collaboration with local NGOs and municipal services, and utilize public recognition by teachers and peers to amplify subjective norms. Link each activity to simple action plans, enabling students to practice doable behaviors both at home and in school. For university students and young workers, lower perceived costs and increased self-efficacy can be achieved through targeted subsidies and discounts for low-carbon options, bulk-procurement schemes via universities, green commuting support (such as transit passes and secure bike parking), reliable recycling and repair infrastructure, and short capability-building modules that convert intention into daily routines. Because self-oriented reward framing can depress intention, mass communication should emphasize collective benefits and shared efficacy rather than individual perks, leveraging the collectivist norms common in the region. Employers and local governments can institutionalize green defaults in dorms, campuses, industrial parks, and SMEs, and offer micro-grants for youth-led projects that improve neighborhood resilience to heat and floods. Implementation should be staged by life stage, utilizing experiential and norm-based strategies for adolescents, and focusing on price relief, convenience, and skills for older youth. Monitoring systems should track changes in perceived cost, self-efficacy, and intention alongside behavior to verify that mechanisms align with the theory and to adapt program components over time.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations. First, while Hue City is Vietnam’s first officially designated “green city” and has piloted several environmental initiatives, many of these programs have only been introduced in recent years. Public engagement remains at an early stage, and the city still lacks supporting infrastructure, such as efficient recycling systems or accessible green transportation. Therefore, although Hue has specific and unique environmental characteristics, it also shares key features with other developing cities undergoing early-stage environmental transitions in Vietnam and possibly in Southeast Asia. Thus, the current study can still serve as a relevant and transferable case study. To further generalize, we may need to consider more factors, including differences in political systems and cultures. For example, one may consider the impacts of a collectivist culture [63]; however, this issue is beyond the scope of current research and needs further investigation.

Second, due to resource constraints, data collection relied on online distribution through social media and work-related contacts. As a result, the worker sample (n = 111) limits representativeness. Additionally, the small size of this group may have influenced model fitness and reduced statistical power in subgroup comparisons. Future research should include a more diverse and balanced sample across occupational and demographic backgrounds.

Third, although this study proposed 15 PEB indicators, the model could only predict four of these effectively. Fourth, although the measurement model met the required thresholds for composite reliability, several constructs showed relatively low AVE and Cronbach’s alpha values. This indicates a potential issue of low convergent validity, which should be interpreted with caution and addressed in future research through improved scale refinement or additional measurement items.

Fifth, to mitigate the possibility of common method variance, we followed recommended procedural guidelines, including ensuring respondent anonymity, improving item clarity, and separating conceptually different constructs within the questionnaire. However, despite efforts to reduce the influence of social desirability bias through face-to-face interviews and assurance of anonymity, the results still showed relatively high levels of PEB. While this study contributes to regional comparisons, future research could expand cross-national validation of integrated TPB–PMT models, particularly in underrepresented Asian contexts. Further exploration of cultural values, risk perception, and climate experience across diverse developing countries would enhance the model’s generalizability and theoretical relevance.

6. Conclusions

This study provides empirical evidence of subgroup differences in pro-environmental behavior among high-school students, university students, and young workers in Hue City. The findings highlight that psychological and informational factors jointly influence young people’s engagement, but the relative importance of each determinant varies across groups. While subjective norms and environmental education have a significant impact on students’ behavior, young workers tend to respond more to practical incentives and workplace conditions. These insights suggest that future youth policies and programs should move beyond uniform approaches, ensuring that educational initiatives, workplace schemes, and community campaigns are tailored to the needs and behavioral motivations of each subgroup.

Although Hue City offers a valuable case for examining youth participation under a consistent policy environment, future research could extend this analysis to other regions or employ longitudinal designs to capture changes over time. Strengthening comparative evidence will help Vietnam and other rapidly developing Asian countries, facing similar climate and development challenges, design more equitable and practical strategies to empower young people as key agents in the transition toward a low-carbon and climate-resilient future.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su172411060/s1, questionnaire and data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.A.M. and T.K.; Methodology, T.A.M. and T.K.; Software, T.K.; Validation, T.K.; Formal Analysis, T.A.M.; Investigation, T.A.M.; Resources, T.K.; Data Curation, T.A.M.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, T.A.M.; Writing—Review and Editing, T.K.; Visualization, T.A.M.; Supervision, T.K.; Project Administration, T.K.; Funding Acquisition, T.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Student Research Grant of the University of Kitakyushu.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. We reviewed the Research Ethics Committee’s checklist at the University of Kitakyushu and confirmed that our non-invasive, anonymous survey was exempt from their review.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The questionnaire and data are available as Supplemental Material.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Grammarly to improve the grammatical accuracy of the text. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Survey Questions

| Construct | Items |

|---|---|

| Attitudes | A1. Governments must force industries and businesses to protect the environment before producing goods with the highest annual efficiency and profitability. |

| A2. One of the most important reasons for the spread of diseases and poverty is the destruction of the environment. | |

| A3. I think that everyone should do their part to help in climate change mitigation and adaptation and it will reduce extreme weather events. | |

| A4. I feel good about myself when I participate in environmental cleanup activities in my local area (removed). | |

| A5. Humans must be able to lower their standard of living in order to protect the environment (removed). | |

| A6. The flora and fauna on this earth have the same right to life as humans (removed). | |

| Subjective Norm | SN1. I feel social pressure to save energy (removed). |

| SN2. As a member of the community, I am expected to engage in environmentally friendly behavior. | |

| SN3. Most people who are important to me recommend protecting the environment. | |

| SN4. Videos on social networks encourage people to engage in pro-environmental behavior (removed). | |

| SN5. If I create new things from recycled materials, others will admire my behavior (removed). | |

| Self-efficacy/Perceived Behavioral Control | SE1. I understand the precautions that must be taken to protect the environment in daily life. |

| SE2. I know how to protect myself and adapt to CC. | |

| SE3. I learned both swimming and drowning prevention skills to prevent accidents during the flood season. | |

| SE4. I know how to secure my house and protect my belongings when there is a storm flooding (removed) | |

| SE5. I believe I can handle whatever happens to the environment (removed). | |

| SE6. There are actions I can take that can make a difference in mitigating the adverse effects of the climate crisis (removed). | |

| Response Efficacy | RE1. I believe that my actions have an influence on global warming and CC (removed). |

| RE2. My involvement in environmental initiatives has a positive influence on sparking interest and motivating others to participate (removed). | |

| RE3. Carrying out pro-environmental behavior will contribute to making life better for future generations. | |

| RE4. Adhering to environmental ethics helps mitigate environmental risks. | |

| Response Costs | C1. I do not have enough money to buy environmentally friendly products. |

| C2. I prefer to save money for myself rather than contribute to an environmental support fund (removed). | |

| C3. Although plastic bags are environmentally harmful, I still use them because they are cheap (removed). | |

| C4. Participating in environmental programs consumes too much of my free time. | |

| C5. There is no point in whether I am the only one doing activities that protect the environment without the involvement of other people too. | |

| C6. Finding information regarding actions that can protect the environment is very difficult for me. | |

| C7. Facilities that support my participation in environmental protection activities are lacking. | |

| Perceived Severity | PS1. CC poses increasingly severe risks for ecosystems, human health, and the economy (removed). |

| PS2. The storms in my area are becoming more intense and more frequent because of CC. | |

| PS3. Flood and flash floods are increasing, a clear sign of the impact of CC. | |

| PS4. Environmental pollution has become a serious threat for humankind (removed). | |

| Perceived Vulnerability | PV1. Environmental pollution can negatively affect my health (removed). |

| PV2. I will experience the negative effects of environmental degradation in my lifetime. | |

| PV3. I feel that summers are getting hotter, and winters are becoming increasingly bitterly cold (removed) | |

| PV4. I am vulnerable to the negative effects of CC. | |

| Rewards | R1. I would rather dedicate my time to my hobbies than engage in environmental protection activities. |

| R2. I prefer personal transport for its convenience although I am aware that using public transport would save energy and reduce emissions. | |

| R3. I would rather purchase new and trendy clothes than reuse old ones. | |

| R4. There are still many things like price and work that I must worry about compared to environmental sustainability. | |

| R5. I am indifferent to activities that can protect the environment because the future is not my problem. | |

| Environmental information exposure | ME1. TV |

| ME2. Books | |

| ME3. Internet | |

| ME4. Environmental experts | |

| ME5. Environmental groups | |

| ME6. Family and friends | |

| Intention/Behavior | I1/B1. Walked or cycled over short distances to protect the environment |

| I2/B2. Sorted waste at home | |

| I3/B3. Repaired or bought second-hand items instead of buying new ones | |

| I4/B4. Actively reduced consumption in general | |

| I5/B5. Preferred vegetarian meals to those containing meat and dairy products | |

| I6/B6. Avoided using nonessential electrical appliances | |

| I7/B7. Gave away unnecessary clothing and furnishings to charity or friends/family | |

| I8/B8. Carried my own reusable bottle | |

| I9/B9. Used water efficiently and avoided unnecessary wastage | |

| I10/B10. Planted trees | |

| I111/B111. Educated myself about sustainability issues | |

| I12/B12. Talked with others about sustainability issues | |

| I13/B13. Used online tools to raise awareness about sustainability issues | |

| I14/B14. Financially supported a sustainability cause | |

| I15/B15. Participated in nature conservation efforts |

References

- UNDP. Achieving SDG 12: Bridging the Intent-Action Gap among Young Consumers; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. How Green is Household Behaviour? Sustainable Choices in a Time of Interlocking Crises; OECD Studies on Environmental Policy and Household Behaviour; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barford, A.; Proefke, R.; Mugerwa, A.; Stocking, B. Young People and Climate Change; The British Academy: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidaković, P.; Zabkar, V.; Zečević, M.; Sagan, A.; Wojnarowska, M.; Sołtysik, M.; Arslanagic-Kalajdzic, M.; Dlacic, J.; Askegaard, S.; Cleff, T. Trying to buy more sustainable products: Intentions of young consumers. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oinonen, I.; Paloniemi, R. Understanding and measuring young people’s sustainability actions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 91, 102124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leeuw, A.; Valois, P.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. Using the theory of planned behavior to identify key beliefs underlying pro-environmental behavior in high-school students: Implications for educational interventions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 42, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitev, K.; Toy, S.; Nash, N.; Whitmarsh, L.; Mastny, L.; Timmer, V.; St. Pierre, K. Life Transitions: Using “Big Life Moments” to Advance Sustainable Everyday Living. 2023. Available online: https://beacon4sl.com/solutions/life-transitions/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Maran, D.A.; Begotti, T.; Brizio, A. Experiences in environmental education with young people: An overview. In Addressing Climate Anxiety in Schools: Pedagogical Perspectives and Theoretical Foundations; Corkett, J.K., Abdel-Aal, W.M.M., Steele, A., Eds.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2025; p. 19. Available online: https://www.routledge.com/Addressing-Climate-Anxiety-in-Schools-Pedagogical-Perspectives-and-Theoretical-Foundations/Corkett-MoawadAbd-El-Aal-Steele/p/book/9781032757520 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Zsóka, Á.; Szerényi, Z.M.; Széchy, A.; Kocsis, T. Greening due to environmental education? Environmental knowledge, attitudes, consumer behavior and everyday pro-environmental activities of Hungarian high school and university students. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 48, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansmann, R.; Laurenti, R.; Mehdi, T.; Binder, C.R. Determinants of pro-environmental behavior: A comparison of university students and staff from diverse faculties at a Swiss University. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 268, 121864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, P.C.; Shrestha, R.; Ray, S.; Knez, R. Determinants of Adolescents’ Pro-Sustainable Behavior: A Systematic Literature Review Using PRISMA. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denault, A.-S.; Bouchard, M.; Proulx, J.; Poulin, F.; Dupéré, V.; Archambault, I.; Lavoie, M.D. Predictors of Pro-Environmental Behaviors in Adolescence: A Scoping Review. Multidiscip. Digit. Publ. Inst. 2024, 16, 5383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, P.; Pietarinen, J.; Havu-Nuutinen, S.; Pöllänen, S.; Pelkonen, P. The Theory of Planned Behavior model and students’ intentions to use bioenergy: A cross-cultural perspective. Renew. Energy 2016, 89, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, K.S.; Head, B.W. Determinants of young Australians’ environmental actions: The role of responsibility attributions, locus of control, knowledge and attitudes. Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 18, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomari, M.M.; EL-Kanj, H.; Topal, A.; Alshdaifat, N.I. Energy conservation behavior of university occupants in Kuwait: A multigroup analysis. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 52, 102198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durr, E.; Bilecki, J.; Li, E.Q. Are beliefs in the importance of pro-environmental behaviors correlated with pro-environmental behaviors at a college campus? Sustainability 2017, 10, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesselink, R.; Blok, V.; Ringersma, J. Pro-environmental behaviour in the workplace and the role of managers and organisation. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 1679–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckstein, D.; Künzel, V.; Schäfer, L. Global Climate Risk Index 2021, no. March. 2021. Available online: http://germanwatch.org/en/download/8551.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- World Bank. Climate Risk Country Profile: Vietnam; The World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA; Asian Development Bank: Metro Manila, Philippines, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. Youth for Climate Action in Viet Nam 2022; UNDP: New York City, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Youth4Climate Policy Working Group; Climate Change Education Team. Youth Engagement for a Sustainable Future Strengthening Climate Change Education in Viet Nam; UNDP Viet Nam: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2025; Available online: https://www.undp.org/vietnam/publications/youth-engagement-sustainable-future-strengthening-climate-change-education-viet-nam (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Nhat, N.T.H. The status and management solutions to environmental protection education in Hue university. Hue Univ. J. Sci. 2011, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WWF. Hue is First City in Vietnam Recognized for Its Commitment to Low-Carbon Development. WWF News. 2016. Available online: https://wwf.panda.org/wwf_news/?271991/hue-first-city-vietnam-recognized-commitment-low-carbon (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Ministry of Agriculture and Environment of Viet Nam. First ‘Deposit–Return’ Model Launched in Hue. Ministry of Agriculture and Environment News; 2025. Available online: https://en.mae.gov.vn/first-depositreturn-model-launched-in-hue-9017.htm (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Hue City Electronic Information Portal. Lan tỏa phong trào Ngày Chủ nhật xanh. Hue City Government News; 2025. Available online: https://hue.gov.vn/Chuyen-trang/Ngay-Chu-nhat-xanh/Tin-tuc-Su-kien/tb/Lan-toa-phong-trao-Ngay-Chu-nhat-xanh-569363 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R.W. A Protection Motivation Theory of Fear Appeals and Attitude Change. J. Psychol. 1975, 91, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddux, J.E.; Rogers, R.W. Protection motivation and self-efficacy: A revised theory of fear appeals and attitude change. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 19, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liang, J.; Yang, J.; Ma, X.; Li, X.; Wu, J.; Yang, G.; Ren, G.; Feng, Y. Analysis of the environmental behavior of farmers for non-point source pollution control and management: An integration of the theory of planned behavior and the protection motivation theory. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 237, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Wang, C.; Sun, M.; Wang, X. Research on the driving factors of rural residents’ pro-environmental behavior under the background of frequent heat waves. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2024, 51, e02893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Young consumers’ intention towards buying green products in a developing nation: Extending the theory of planned behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiei, A.; Maleksaeidi, H. Pro-environmental behavior of university students: Application of protection motivation theory. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 22, e00908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainear, A.M.; Christensen, J.L. Protection Motivation Theory as an Explanatory Framework for Proenvironmental Behavioral Intentions. Commun. Res. Rep. 2017, 34, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Jeong, S.H.; Hwang, Y. Predictors of Pro-Environmental Behaviors of American and Korean Students: The Application of the Theory of Reasoned Action and Protection Motivation Theory. Sci. Commun. 2013, 35, 168–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shutaleva, A.; Martyushev, N.; Nikonova, Z.; Savchenko, I.; Abramova, S.; Lubimova, V.; Novgorodtseva, A. Environmental behavior of youth and sustainable development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, H.; Cohen, F.; Warner, A. Youth and environmental action: Perspectives of young environmental leaders on their formative influences. J. Environ. Educ. 2009, 40, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauw, J.B.-D.; Van Petegem, P. A Cross-Cultural Study of Environmental Values and Their Effect on the Environmental Behavior of Children. Environ. Behav. 2013, 45, 551–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrselja, I.; Pandžić, M.; Rihtarić, M.L.; Ojala, M. Media exposure to climate change information and pro-environmental be-havior: The role of climate change risk judgment. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Id, D.C.; Zhang, A. The effect of social media environmental information exposure on the intention to participate in pro-environmental behavior. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0294577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suminar, J.R.; Hafiar, H.; Amin, K.; Prastowo, A.A. Predicting pro-environmental behavior among generation Z in Indonesia: The role of family norms and exposure to social media information. Front. Commun. 2024, 9, 1461609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phang, G.; Ilham, Z. Theory of planned behavior to understand pro-environmental behavior among Universiti Malaya students. AIMS Environ. Sci. 2023, 10, 691–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vantamay, N. Factors affecting Environmentally Sustainable Consumption Behavior (ESCB) among Thai Youth through the Theory of Planned Behavior. In Proceedings of the RSU International Research Conference 2020, Rangsit University, Thailand, Online, 1 May 2020; pp. 1257–1265. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.N.; Lobo, A.; Nguyen, B.K. Young consumers’ green purchase behaviour in an emerging market. J. Strateg. Mark. 2018, 26, 583–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, H.; Islam, T.; Hoque, M.R.; Asia, S. Understanding Young Consumers’ E-Waste Recycling Behaviour in Bangladesh: A Developing Country Perspective in identified. Recycling 2025, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Wu, N.; Chen, N. Young people’s behavioral intentions towards low-carbon travel: Extending the theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, P.; Shaw, R. Towards an integrated approach of disaster and environment management: A case study of Thua Thien Hue province, central Viet Nam. Environ. Hazards 2007, 7, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoplos, I.; Ngoan, L.D.; Sen, L.T.H.; Huong, N.T.T.; Lindegaard, L.S. The evolving local social contract for managing climate and disaster risk in Vietnam. Disasters 2017, 41, 448–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P.; Lee, J.Y. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alisat, S.; Riemer, M. The environmental action scale: Development and psychometric evaluation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 43, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Kellogg, J.L.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrawad, M.; Lutfi, A.; Alyatama, S.; Al Khattab, A.; Alsoboa, S.S.; Almaiah, M.A.; Ramadan, M.H.; Arafa, H.M.; Ahmed, N.A.; Alsyouf, A.; et al. Assessing customers perception of online shopping risks: A structural equation modeling–based multigroup analysis. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 71, 103188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Siguaw, J.A. Formative versus reflective indicators in organizational measure development: A comparison and empirical illustration. Br. J. Manag. 2006, 17, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit. Sociol. Methods Res. 1992, 21, 230–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, N.; Menzel, S. Predicting the intention to support the return of wolves: A quantitative study with teenagers. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 36, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Cavusgil, E.; Zhao, Y. A protection motivation explanation of base-of-pyramid consumers’ environmental sustainability. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, J.M.; Mlynski, C.; Job, V. Just a drop in the ocean? How lay beliefs about the world influence efficacy, perceptions, and intentions regarding pro-environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 100, 102445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jugert, P.; Greenaway, K.H.; Barth, M.; Büchner, R.; Eisentraut, S.; Fritsche, I. Collective efficacy increases pro-environmental intentions through increasing self-efficacy. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 48, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaim, J.A.; Maloni, M.J.; Napshin, S.A.; Henley, A.B. Influences on Student Intention and Behavior Toward Environmental Sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 124, 465–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suntornsan, S.; Chudech, S.; Piyapong, J. The Role of the Theory of Planned Behavior in Explaining the Energy-Saving Behaviors of High School Students with Physical Impairments. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alherimi, N.; Marva, Z.; Hamarsheh, K.; Alzaaterh, A. Employees’ pro-environmental behavior in an organization: A case study in the UAE. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, P.; Wu, W.; Huo, C. Crucial to Me and my society: How collectivist culture influences individual pro-environmental behavior through environmental values. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 454, 142211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).