Abstract

Numerous models exist for estimating the specific energy yield of wind turbines, typically relying on meteorological wind speed data and turbine characteristics. However, the applicability and accuracy of these models must be validated against real-world data, particularly concerning the conditions specific to Poland. The primary objective of this study was to verify the accuracy of existing wind energy yield models for onshore wind turbine installations in Polish conditions. The study was conducted in two parts. First, the compliance of wind speed data derived from two global reanalysis databases (ERA5 and MERRA) was analyzed against actual hourly measurements. These measurements were collected from nacelle-mounted sensors at the hub height of six operational turbines (two 3 MW and four 0.8 MW units) at a wind farm site over the course of 2019. Second, a computational model for the specific energy yield was verified using the same on-site measurements, incorporating data on turbine configuration, location, and the ERA5/MERRA inputs. A significant discrepancy was observed: wind speeds measured directly on the higher-capacity turbines (3 MW) were consistently higher than those reported in the ERA5 and MERRA databases. This difference is attributed to the fact that the coarse grid resolution of global databases does not capture the precise, optimized placement of turbines at sites specifically selected for high wind potential, often considering local topography. Despite this initial wind speed variance, the subsequent verification of the energy yield model showed satisfactory agreement with real production data. The relative mean bias error (rMBE) was found to be below 8% for the ERA5 input paired with the 3 MW turbine data and below 12% for the MERRA input paired with the 0.8 MW turbine data. The findings confirm that while global reanalysis databases may underestimate local wind speeds due to generalized grid resolution, the tested energy yield model provides satisfactory results for wind turbine planning in Poland.

1. Introduction

Climate change and extreme weather events are affecting the stability of energy systems while causing strong negative socio-cultural issues in the regions where they occur. The physical damage and energy supply disruptions directly result in major power interruptions and energy price increases. Mitigations, actions, and adaptive solutions need to be identified in order to reduce energy system vulnerabilities and the socioeconomic effects on local communities [1].

The integration of renewable energy sources (RES) into power systems is coupled with the use of machine learning (ML)-based tools for forecasting energy production and consumption [2]. This approach is proving to be crucial for enhancing the reliability of energy systems and optimizing the utilization of low-carbon energy sources, such as wind turbines [3]. This is particularly important because a significant worldwide increase in the installed capacity and production of RES (mainly photovoltaics and wind energy) is being observed [4].

In this context, the proper design and selection of wind turbine installations for investors (based on wind assessments using meteorological data or proprietary measurements) have a direct impact on the economics of the investment and management stability, as well as many other aspects [5,6,7]. Furthermore, surplus electricity from wind turbines can be utilized, for instance, for hydrogen production [8,9], energy storage [10], or heat [11].

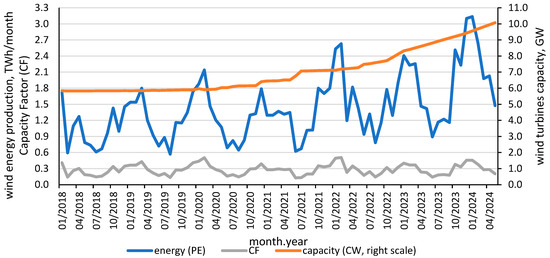

Figure 1 presents the increase in installed capacity and the amount of energy produced on a monthly scale for the years 2018–2024.

Figure 1.

Onshore monthly wind energy production (PE), capacity factor (CF), and capacity (CW) in Poland in 2018–2024.

Between 2018 and 2024, Poland experienced an increase in installed capacity from 5.8 GW to over 10 GW. Monthly energy production ranged from 0.57 TWh in August 2019 to 2.6 TWh in February 2022 and 3.1 TWh in January 2024. From 2018 to 2022, the global capacity increased from 541 GW to 846 GW [12].

Literature Review

One of the main barriers to building new wind turbines is regulations in the context of the national potential of wind energy development [13]. Research of wind energy potential in south-eastern Poland was performed by Duraczynski and Filipowicz [14,15]. Filipowicz et al. conducted a study of building integrated wind turbines operation (example of Center of Energy AGH in Poland, Cracow) [16].

The potential for developing renewable energy in Poland has been investigated by Paska et al. [17], as well as the cooperation and synchronization between onshore and offshore wind energy [18]. The share of wind energy in Poland is expected to be higher in the future than it is in 2024 [19,20]. This development will necessitate the assessment of wind energy potential.

Bilgili et al. investigated potential of wind offshore energy productivity in Europe [21]. Ilhan et al. analyzed five 2 MW turbines in onshore wind farms [22].

Cacciuttolo et al. analyzed publications on the potential of various sources classified as renewable for South America, including wind energy [23,24]. Nelli et al. analyzed the agreement between weather data from the ERA5 service for the Arabian Peninsula [25]. Suo et al. examined the quality assessment of ERA5 wind speed for the coastal area of Bohai Bay using as a metric of quality the r2 coefficient [26]. Su et al. examined the effect of different types of turbines and their locations on productivity [27]. Jurasz et al. compared 40 years of wind speed research and used the Spearman coefficient of correlation and the Mann–Kendal test on the wind speed data [28].

The MERRA database was used to calculate wind energy in Poland and Europe [29,30]. Sakuru investigated wind power and energy potential across India, including the ERA5 reanalysis data [31]. Jung and Schindler researched the influence of wind speed model resolution, using ERA5 as a basis [32]. Ruiz et al. assessed wind energy potential in the Caribbean region of Colombia, based on ten-minute wind observations and also ERA5 data [33].

There is a lack of studies comparing modeled and actual wind energy production for different types of wind turbines, particularly in Central European regions. This comparison is important given the numerous plans to install new wind turbines and to increase the share of wind energy in Poland’s energy mix.

2. Materials: Wind Turbine Installation

Wind turbines installation (group of wind turbines, Figure 2) is located in Poland in Gaj Olawski (Lower Silesia Voivodeship in Poland): 50.92° N 17.24° E. The list of wind turbines includes: 2 × 3 MW named T3_1 and T3_2 and four wind turbines with a capacity of 0.8 MW: T08_1, T08_2, T08_3, and T08_4.

Figure 2.

Part of wind turbine farm in Gaj Olawski (research object)–photo.

Properties of wind turbines which are installed are included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of wind turbine for simulation. Source: own study based on [34,35].

Table 1.

Characteristics of wind turbine for simulation. Source: own study based on [34,35].

| Parameter | Value for 3 MW (T3) | Value for 0.8 MW (T08) | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| wind turbine model (T) | ENERCON E-115 | ENERCON E-53 | - |

| nominal power (NP) | 3 | 0.8 | MW |

| hub height | 92 | 60 | m |

| cut-in wind speed (cisp) | 2 | 3 | m/s |

| rated wind speed (rws) | 11.5 | 12 | m/s |

| cut-out wind speed (cosp) | 25 | 34 | m/s |

| cross-sectional area of the wind (swept area) (A) | 10,515.5 | 2198 | m2 |

| coefficient of power, max (Cp), please also see Figure 3 | 0.47 | 0.49 | - |

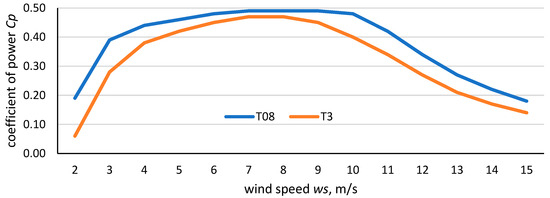

Figure 3.

Coefficient of power Cp for turbines: T08 and T3. Source: own study based on [34,35].

Turbine T08 achieves a higher maximum efficiency (peaking near 0.50) over a broader range of wind speeds, approximately between 7 and 10 m/s, demonstrating superior performance compared to turbine T3, which peaks at about 0.47 around 8 m/s.

2.1. Wind Turbine Installation Specific Yield

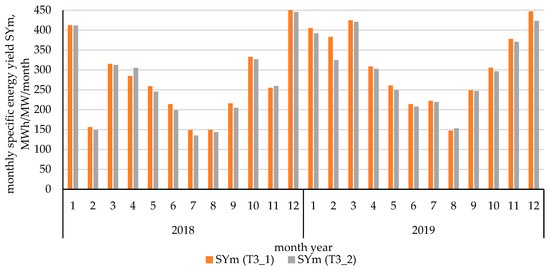

The energy generation results of the installation were measured at the output of the wind turbine every 5 min. The values obtained in this way were subsequently aggregated to the hourly and monthly scale (SYm) and calculated per 1 MW of the wind turbine’s installed capacity (see Figure 4).

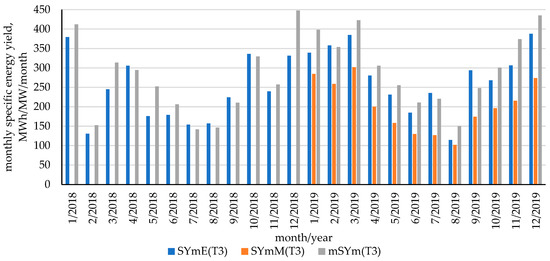

Figure 4.

Measured monthly unit wind specific yields (SYm)—results from 3 MW wind turbines’ capacity.

The annual specific yield for turbine T3_1 was 3193 MWh/MW in 2018, while in 2019 it rose significantly to 3743.8 MWh/MW. Similarly, turbine T3_2 recorded an annual specific yield of 3136.6 MWh/MW in 2018, increasing to 3606.3 MWh/MW in 2019. The peak monthly value was registered in December 2018, reaching 450 MWh/MW/month for T3_1 and 446 MWh/MW/month for T3_2. Conversely, the lowest monthly value recorded was 147 MWh/MW/month for T3_1 in August 2019 and 135 MWh/MW/month for T3_2 in July 2018. This indicates a high amplitude in monthly performance, as the highest recorded monthly yields were approximately three times higher than the lowest monthly yields.

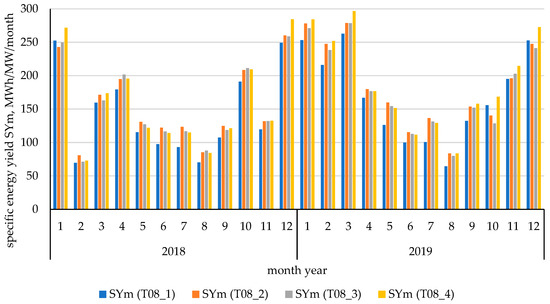

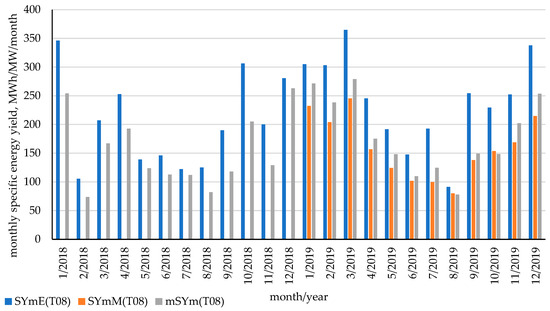

Figure 5.

Measured monthly unit wind energy production (SYm)—results from 0.8 MW wind turbines capacity.

The annual specific energy yield for the T08 turbine group exhibited a consistent and significant increase in 2019 compared to 2018 across all four units. For instance, turbine T08_1 produced 1704.5 MWh/MW in 2018, which rose to 2025.6 MWh/MW in 2019. Similarly, the highest annual output was achieved by T08_4, generating 1897.4 MWh/MW in 2018 and the overall maximum yield of 2230 MWh/MW in 2019. This overall upward trend suggests that the year 2019 was characterized by more favorable wind conditions compared to the preceding year, benefiting the entire T08 fleet.

The analysis of monthly extremes reveals a high degree of seasonal volatility. The peak monthly specific yield (SYm) for all T08 turbines was uniformly recorded in March 2019, with values ranging from 263 MWh/MW/month for T08_1 up to 297 MWh/MW/month for T08_4. Conversely, the lowest monthly values were found in the range of 64 MWh/MW/month (T08_1 in August 2019) to 81 MWh/MW/month (T08_2 in February 2018). The substantial difference between these extremes is highlighted by the fact that the highest recorded monthly yields were approximately four times higher than the lowest monthly yields.

Furthermore, a significant disparity exists when comparing the peak performance of the two turbine classes. When comparing the highest monthly specific yield (SYm) values achieved by the 3 MW turbines (T3, peaking at 450 MWh/MW/month) to those of the 0.8 MW turbines (T08, peaking at 297 MWh/MW/month for T08_4), the T3 class achieved values over 60% higher. This difference underscores the impact of turbine size and design on maximal energy output capacity, even when the smaller units benefit from similar seasonal variations.

2.2. Wind Speed Data

Wind speed data were obtained for the location of wind installation: Gaj Olawski (51.0° N; 17.25° E) from the ERA5 database website [36]. Data are available for each hour, in this case use for the period 1 January 2019—31 December 2019 and 1 January 2018—31 December 2018, as [37]:

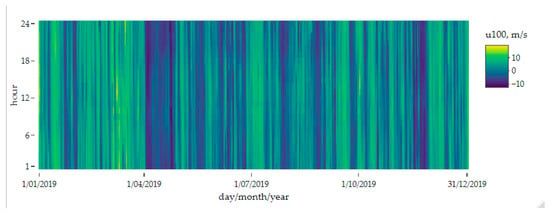

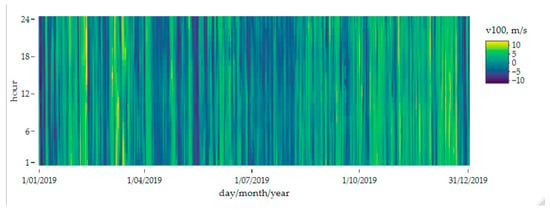

- u100—the eastward component of the 100 m wind. It is the horizontal speed of air moving towards the east, at a height of 100 m above the surface of the Earth; from ERA5 database, m/s [38]–Figure A1 in Appendix A.

- v100—the northward component of the 100 m wind. It is the horizontal speed of air moving towards the north, at a height of 100 m above the surface of the Earth; from ERA5 database, m/s [38]–Figure A2.

Calculations based on available data were performed for the years 2018 and 2019. The selection criterion was the availability of comparative data from actual measurements (energy production data for both years and wind speed data for 2019). In addition to the ERA5 data, data from the MERRA service were also obtained for the Gaj Oławski location (50.92° N, 17.24° E) [39].

3. Methods

3.1. Comparison of Measured and ERA5, MERRA Wind Speed Values

The initial step in the calculations involved determining the potential onshore wind power for the Gaj Oławski location. For this purpose, hourly wind speed data were collected for the period 1 January 2019 to 31 December 2019. The data was retrieved hourly from the ERA5 and MERRA databases (see Section 2, Appendix A, Figure A1 and Figure A2).

Equation used for the hourly wind speed based on ERA5 data is

where

- wsE: wind speed calculated based on ERA5 data, m/s

- τ: hour of year

- u100: the eastward component of the 100 m wind, from ERA5 database, m/s

- v100: the northward component of the 100 m wind, from ERA5 database, m/s

- mwsE: monthly mean wind speed calculated based on ERA5 data, m/s

- τm: hour of month

- d: number of days in month

- mo: month of analyses

- mwsM: monthly mean wind speed calculated based on MERRA database, m/s

- wsM: wind speed from MERRA database, m/s

- mws: measured monthly mean wind speed for T3 or T08 wind turbine, m/s

- ws: monthly measured wind speed on wind turbine, m/s

- T: T3 or T08

The comparison of the monthly calculated values of wind speed with the measured values was made according to the following Equation on relative mean bias error (rMBE) [40]:

The comparison of the monthly calculated values of wind energy production with the measured values was made according to the above Equation (5) for rMBE. The RSME value was also determined by following Equation [41]:

where

- : total number of observations (for example, 12 per year)

3.2. Comparison of Measured and Based on ERA5 Wind Energy Production

For the collected data, the potential average hourly power of wind turbines was determined based on wind power calculations:

where

- WTP: hourly mean wind turbine power, MW

- τ: hour of year

- Cp: power coefficient of wind turbine, turbine producer data, from Table 1

- ρ: density of air, 1.2 from [42], kg/m3

- A: cross-sectional area of the wind (swept area), from Table 1, m2

- ws: wind speed (wsE or wsM), please also see Equation (2), m/s

- NP: nominal power of wind turbine, from Table 1, MW

- cisp: cut-in speed, from Table 1, m/s

- cosp: cut-off speed, from Table 1, m/s

- rws: rated wind speed, from Table 1, m/s

Theoretical hourly unit wind turbine energy (based on nominal power) was calculated based on the following Equation, for ERA5:

where

- SYhE: hourly unit wind turbine specific yield based on ERA5 data, MWh/MW

- SYmE: monthly unit wind turbine specific yield based on ERA5 data, MWh/MW/month

- Calculation of the hourly unit wind turbine specific yield based on MERRA wind speed data:

- SYhM: hourly unit wind turbine specific yield based on MERRA data, MWh/MW

- SymM: monthly unit wind turbine specific yield based on MERRA data, MWh/MW/month

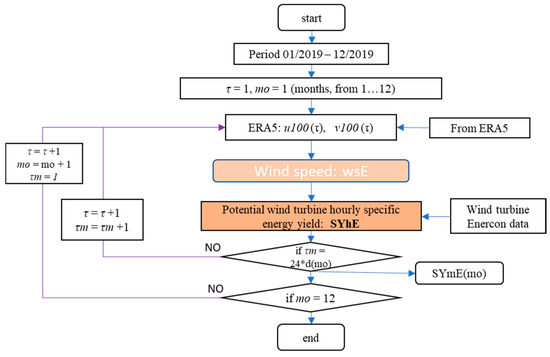

The algorithm for calculations (only for ERA5 data) is presented in the Figure 6 below:

Figure 6.

Algorithm of calculation hourly unit wind turbine specific yield values (SYhE) and for monthly specific yield (SYmE); d(m)—number of days in month m.

Mean value (for many wind turbines with the same capacity) of wind turbine measured specific yields are calculated using the following Equations:

where

- Sym: monthly measured unit wind turbine specific energy yield, MWh/MW/month

- mSYm: monthly measured unit wind turbine specific energy yield, MWh/MW/month

The comparison of the daily and monthly calculated values of wind turbine specific yields with the measured values was made according to the following Equation on relative mean bias error (rMBE) [40]:

where

- Sym: monthly measured unit wind turbine specific energy yield, MWh/MW/month

The comparison of the monthly calculated values of wind energy production with the measured values was made according to the following Equation (5) for rMBE. The RSME value was also determined by following Equation [41]:

where

- : total number of observations (months)

- mSYm: mean monthly measured unit specific energy yield for wind turbines, MWh/MW/month

3.3. Capacity Factor Calculation

Based on a methodology similar to the Capacity Factor (CF) calculation shown in the works of Boretti and Castelletto [43] and Kulpa et al. [44], monthly CF values were calculated according to the following formula:

where

- mCF: mean (for T3 or T08) monthly capacity factor

- mo: month of analyses

- : mean monthly measured specific yields

- d: number of days in the month

For comparison purposes, the monthly capacity factor for all existing wind turbines in Poland was also determined based on PSE data:

where

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Comparison of Measured and ERA5, MERRA Wind Speed

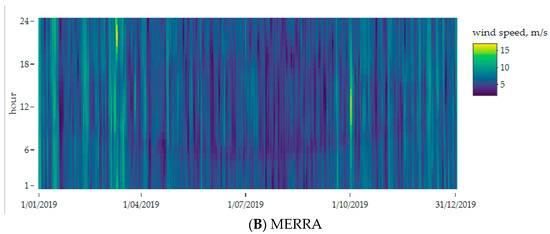

The wind speed calculation method based on ERA5 allowed for the determination of average hourly wind speeds–Figure 7A.

Figure 7.

(A) Calculated wind speed values based on data from ERA5 for the nearest place for the installation site according to the available ERA5 data geographical grid (51° N and 17.25° E) hub height 100 m, (B) MERRA hub height 80 m (50.92° N and 17.24° E); both for period 01 January 2019–31 December 2019.

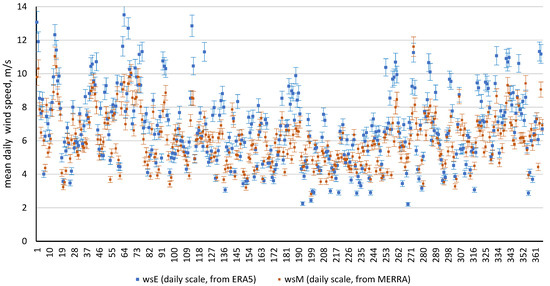

The results of the average daily wind speed calculations for the ERA5 and MERRA data are presented in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Mean daily wind speed: ERA5 and MERRA data.

For the ERA5 data, the lowest average daily wind speed was 2.2 m/s, and the highest was 13.5 m/s, while for the MERRA data, these values ranged from 2.8 m/s to 11.6 m/s, respectively.

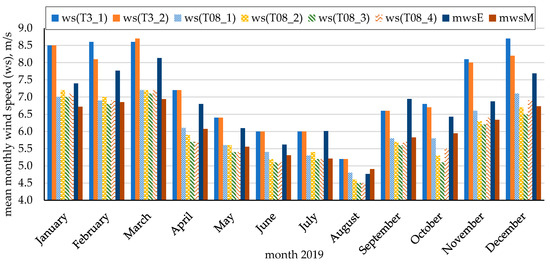

A comparison of measured and ERA5 wind speed for months in the year 2019 is depicted in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Comparison between calculated monthly mean wind speed values based on data from ERA5 for the closest place for the installation according to the available ERA5 geographical grid (51° N and 17.25° E) and MERRA database and measured monthly mean wind speed values on six wind turbines.

The average monthly wind speed in January and December ranged between 6.7 and 8.7 m/s, but in August, it ranged between 4.7 and 5.7 m/s. The comparison of rMBE and RMSE for monthly wind speed values is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Values of rMBE and RSME for monthly mean wind speed.

4.2. Comparison of Measured and Calculated Wind Energy Production

The calculated SYmE and SYmM values based on Equation (12) are compared with the calculated mSYm values (based on Equation (11) for the T3 turbines (with a capacity of 3 MW)—the comparison results are presented in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Comparison between calculated monthly unit wind energy production based on data from ERA5 and MERRA and measured monthly unit wind energy production values on two wind turbines (3 MW capacity each).

The sum of the calculated monthly specific yield values for T3 based on ERA5 data in 2018 was 2858.3 MWh/MW/year (the measured average value was 3164.8 MWh/MW/year, a difference of 9.7%), and, in 2019, it was 3383.8 MWh/MW/year (the measured average value was 3675.1 MWh/MW/year, a difference of 8.0%). In contrast, the sum of the calculated monthly specific yield values for T3 based on MERRA data in 2019 was 2422.0 MWh/MW/year (34% lower than the measured value). Shown as Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Comparison between calculated monthly unit wind energy production based on data from ERA5 and measured monthly unit wind energy production values on four wind turbines (0.8 MW capacity each).

The sum of the calculated monthly specific yield values for T08 based on ERA5 data in 2018 was 2421.2 MWh/MW/year (the measured average value was 1833.4 MWh/MW/year, a difference of +32%), and in 2019, it was 2915.7 MWh/MW/year (the measured average value was 2177.7 MWh/MW/year, a difference of +34%). In contrast, the sum of the calculated monthly specific yield values for T08 based on MERRA data in 2019 was 1919.4 MWh/MW/year (12% lower than the measured value). The full accuracy assessment, including a comparison of these calculated values in terms of relative mean bias error (rMBE) and root mean square error (RMSE), is available in Table 3.

Table 3.

rMBE and RSME values for monthly values of specific yields, LoD–lack of data.

Analysis of the 2019 data indicated that the computational model based on ERA5 data (SYmE) is characterized by a significant overestimation of the yield for the T08 wind turbines (rMBE: 0.339), which is consistent with the findings from the preceding chart, where a persistent inflation of values was observed. This overestimation is accompanied by a relatively high overall error (RMSE: 66.497). In contrast, for the T3 turbines, the same model exhibited a very small underestimation (rMBE: −0.079) with a lower error (RMSE: 39.090). Interestingly, the comparison of the measured data (SYmM) with the mSYm values in 2019 showed the highest overall accuracy (the lowest RMSE: 26.118) and a moderate underestimation (rMBE: −0.119) for the T08 turbines, suggesting that the mSYm model for T08 most accurately reflected the actual measurements. The data for 2018 is incomplete, as measured SYmM values for both systems were absent, designated as LoD (Lack of Data). Nevertheless, the SYmE (based on ERA5) model for 2018 exhibited similar tendencies to those observed in 2019: a significant overestimation for T08 (rMBE: 0.321) with an RMSE of 56.862, and a slight underestimation for T3 (rMBE: −0.097) with an RMSE of 47.680. In conclusion, the table confirms a systematic and substantial positive bias (overestimation) of the computational model based on ERA5 data for the T08 turbines in both analyzed years, while simultaneously indicating the best agreement (lowest RMSE) between the measurements and the mSYm model results for T08 in 2019.

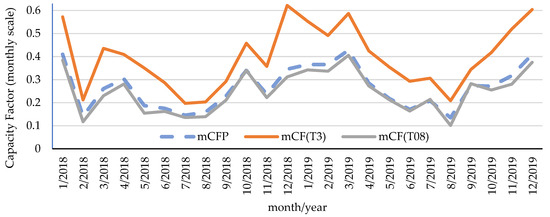

The comparison of the capacity factor (CF) values measured at an onshore wind farm in Poland (capacity is shown in Figure 1) is presented below (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Comparison between measured mean CF for T3 and mean CF for T08 and capacity factor for whole Polish wind turbines (mCFP).

The CF values for T3 were consistently higher than those for T08 across the entire period. All three series exhibited significant seasonal variability, generally showing lower CF values during the summer months and higher values during the winter and early spring.

Specifically, the capacity factor for T3 reached its highest value of 62% in December 2018, while the lowest value was recorded in August 2019 at 21%. The T08 wind turbines also showed substantial fluctuation, achieving their highest capacity factor of 41% in March 2019. Similarly to T3, the T08 recorded its lowest CF value in August 2019, reaching 10%. The calculated mCFP generally follows the seasonal trends of the measured systems but tracks T08 more closely in 2018 and lies between T3 and T08 in 2019.

5. Conclusions

The article examines the compliance of the indications of the wind energy producing model contained in the ERA5 and MERRA website with the measurements carried out for south-western Poland (Gaj Olawski village). The research lasted 2 years, from 2018 to 2019. The annual sum was 3675.1 MWh/MW measured, with model calculations as follows: ERA5: 3383.8 MWh/MW, MERRA: 2422 MWh/MW for T3 in 2019; 2177.7 MWh/MW measured, with model calculations as follows: ERA5: 2915.7 MWh/MW, MERRA: 1919.4 MWh/MW for T08 in 2019. Model adjustment for T3 showed a higher accuracy of results when using ERA5 data, while for T08, MERRA data proved more accurate.

The measured specific yield of wind turbine installations in the years 2018–2019 was around 3420 MWh/MW/year for 3 MW wind turbines and 2006 MWh/MW/year for 0.8 MW wind turbines. The results, in the form of the energy production of six wind turbines over two years, allowed for the validation of the model based on the theoretical methodology (2019 year): rMBE was below 8% (ERA5 and T3) and below 12% (MERRA and T08).

This study presents several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. The comparison between reanalysis datasets and turbine measurements was conducted without adjusting wind speeds to a common hub height, which introduces systematic bias due to differing measurement altitudes. The use of monthly aggregated data reduces temporal resolution and prevents the identification of short-term variability essential for accurate wind resource assessment. Additionally, simplified modeling assumptions, such as constant air density and basic Cp for wind speed relations, limit the physical realism of the energy production simulations. Measurement uncertainties from nacelle-mounted sensors, as well as operational factors such as curtailment or icing, were not evaluated, and the two-year analysis period may not fully represent long-term climatic variability.

Future work should therefore focus on incorporating higher-resolution temporal data (daily or hourly), applying vertical wind profile adjustments to ensure consistent comparison across data sources, and improving the modeling framework with more detailed turbine physics and variable atmospheric conditions. Extending the dataset to multiple years and performing an uncertainty quantification would enhance the robustness of the findings. Furthermore, site-specific bias correction techniques and the calculation of the actual levelized cost of energy (LCOE) should be included to better link meteorological assessments with techno-economic performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.O., L.M. and A.D.; methodology, P.O., J.K. and D.M.; validation, L.M. and A.D.; formal analysis, P.O., D.M., L.M. and J.K.; investigation, P.O.; writing—original draft preparation, P.O., D.M. and L.M.; writing—review and editing, A.D. and J.K.; visualization, L.M., P.O., D.M. and J.K.; supervision L.M., A.D. and P.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding for open access charge: CRUE-Universitat Politècnica de Valencia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| A | area |

| CF | capacity factor |

| cisp | cut-in wind speed |

| cosp | cut-out wind speed |

| Cp | coefficient of power |

| d | number of days in month |

| LCOE | levelized cost of electricity |

| mCFP | mean (for T3 or T08) monthly capacity factor |

| mCFP | mean monthly capacity factor for all wind turbines in Poland |

| ML | machine learning |

| mo | month |

| mSYm | mean monthly measured unit specific energy yield for wind turbines |

| mws | measured monthly mean wind speed for T3 or T08 wind turbine |

| mwsE | monthly mean wind speed calculated based on ERA5 data |

| mwsM | monthly mean wind speed calculated based on MERRA database |

| NP | nominal power |

| PE | wind energy production |

| RES | renewable energy sources |

| rMBE | relative mean bias error |

| RSME | root square mean error |

| rws | rated wind speed |

| SYhE | hourly unit wind turbine specific yield based on ERA5 data |

| SYhM | hourly unit wind turbine specific yield based on MERRA data |

| SYm | specific yield in monthly scale |

| SYmE | monthly unit wind turbine specific yield based on ERA5 data |

| SymM | monthly unit wind turbine specific yield based on MERRA data |

| T | wind turbine model |

| T08 | wind turbine, capacity 0.8 MW |

| T3 | wind turbine, capacity 3 MW |

| u100 | the eastward component of the 100 m wind |

| v100 | the northward component of the 100 m wind |

| ws | monthly measured wind speed on wind turbine |

| wsE | wind speed calculated on ERA5 data |

| wsM | wind speed from MERRA database |

| WTP | hourly mean wind turbine power |

| τ | hour of year |

| τm | hour of month |

| ρ | density of air |

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Eastward component of 100 m wind speed (u100) from ERA5 for the closest place for the installation according to the available ERA5 geographical grid (51° N and 17.25° E), for period 1 January 2019–31 December 2019. Source: own study based on [37].

Figure A2.

Northward component of 100 m wind speed (v100) from ERA5 for the closest place for the installation according to the available ERA5 geographical grid (51° N and 17.25° E), for period 1 January 2019–31 December 2019. Source: own study based on [37].

References

- Castro Hernandez, C.D.; Montuori, L.; Alcázar-Ortega, M.; Olczak, P. Extreme Climate Events and Energy Market Vulnerability: A Systematic Global Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowiński, R.; Komorowska, A. Forecasting Electricity Prices in the Polish Day-Ahead Market Using Machine Learning Models. Polityka Energ. Energy Policy J. 2025, 28, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondón-Cordero, V.H.; Montuori, L.; Alcázar-Ortega, M.; Siano, P. Advancements in Hybrid and Ensemble ML Models for Energy Consumption Forecasting: Results and Challenges of Their Applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 224, 116095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stecuła, K. Renewable Energy Sources as an Opportunity for Global Economic Development. In Proceedings of the 17th International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference SGEM2017, Albena, Bulgaria, 29 June–5 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gulkowski, S. Specific Yield Analysis of the Rooftop PV Systems Located in South-Eastern Poland. Energies 2022, 15, 3666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogus, R.; Soltysik, M.; Czapaj, R. Application of Similarity Analysis in PV Sources Generation Forecasting for Energy Clusters. E3S Web Conf. 2019, 84, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stecuła, K.; Brodny, J. Perspectives on Renewable Energy Development as Alternative to Conventional Energy in Poland. In Proceedings of the International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference Surveying Geology and Mining Ecology Management, SGEM, Albena, Bulgaria, 27 June–6 July 2017; Volume 17, pp. 717–724. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, I.H.; Alakoul, K.A.; Al-Manea, A.; Wetaify, A.R.H.; Saleh, K.; Al-Rbaihat, R.; Alahmer, A. An Overview of Hydrogen Production Techniques: Challenges and Limiting Factors in Achieving Wide-Scale Productivity. AIP Conf. Proc. 2024, 3051, 50003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benalcazar, P.; Komorowska, A. Prospects of Green Hydrogen in Poland: A Techno-Economic Analysis Using a Monte Carlo Approach. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 5779–5796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olczak, P.; Kopacz, M. Operating Parameters and Charging/Discharging Strategies for Wind Turbine Energy Storage Due to Economic Benefits. Energies 2025, 18, 4426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komorowska, A.; Surma, T. Comparative Analysis of District Heating Markets: Examining Recent Prices, Regulatory Frameworks, and Pricing Control Mechanisms in Poland and Selected Neighbouring Countries. Polityka Energ. Energy Policy J. 2024, 27, 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA Wind Power Capacity in the Net Zero Scenario, 2015–2030. Available online: https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/wind-power-capacity-in-the-net-zero-scenario-2015-2030 (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- Piwowar, A.; Dzikuć, M. The Potential of Wind Energy Development in Poland in the Context of Legal and Economic Changes. Acta Polytech. Hung. 2023, 20, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duraczyński, M.; Filipowicz, M. Comparison of Wind and Water Energy Resources for Chosen Locations in South-East Poland. Polityka Energ. Energy Policy J. 2011, 14, 253–270. [Google Scholar]

- Sornek, K.; Filipowicz, M.; Goryl, W.; Mokrzycki, E.; Mirowski, T.; Duraczyński, M. The Analysis of the Wind Potential in Selected Locations in the Southeastern Poland. E3S Web Conf. 2017, 14, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipowicz, M.; Goryl, W.; Żołądek, M. Study of Building Integrated Wind Turbines Operation on the Example of Center of Energy AGH. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 214, 12122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paska, J.; Surma, T.; Terlikowski, P.; Zagrajek, K. Electricity Generation from Renewable Energy Sources in Poland as a Part of Commitment to the Polish and EU Energy Policy. Energies 2020, 13, 4261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olczak, P.; Surma, T. Energy Productivity Potential of Offshore Wind in Poland and Cooperation with Onshore Wind Farm. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdonek, I.; Tokarski, S.; Mularczyk, A.; Turek, M. Evaluation of the Program Subsidizing Prosumer Photovoltaic Sources in Poland. Energies 2022, 15, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczerbowski, R.; Kornobis, D. The Proposal of an Energy Mix in the Context of Changes in Poland’s Energy Policy. Polityka Energetyczna 2019, 22, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgili, M.; Alphan, H.; Ilhan, A. Potential Visibility, Growth, and Technological Innovation in Offshore Wind Turbines Installed in Europe. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 27208–27226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilhan, A.; Bilgili, M.; Sahin, B. Analysis of Aerodynamic Characteristics of 2 MW Horizontal Axis Large Wind Turbine. Wind Struct. Int. J. 2018, 27, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciuttolo, C.; Navarrete, M.; Atencio, E. Renewable Wind Energy Implementation in South America: A Comprehensive Review and Sustainable Prospects. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciuttolo, C.; Guzmán, V.; Catriñir, P. Renewable Solar Energy Facilities in South America—The Road to a Low-Carbon Sustainable Energy Matrix: A Systematic Review. Energies 2024, 17, 5532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelli, N.; Francis, D.; Alkatheeri, A.; Fonseca, R. Evaluation of Reanalysis and Satellite Products against Ground-Based Observations in a Desert Environment. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suo, C.; Sun, A.; Yan, C.; Cao, X.; Peng, K.; Tan, Y.; Yang, S.; Wei, Y.; Wang, G. Quality Assessment of ERA5 Wind Speed and Its Impact on Atmosphere Environment Using Radar Profiles along the Bohai Bay Coastline. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Wang, X.; Xu, W.; Yuan, L.; Xiong, C.; Chen, J. Offshore Wind Power: Progress of the Edge Tool, Which Can Promote Sustainable Energy Development. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurasz, J.; Mikulik, J.; Dąbek, P.B.; Guezgouz, M.; Kaźmierczak, B. Complementarity and ‘Resource Droughts’ of Solar and Wind Energy in Poland: An ERA5-Based Analysis. Energies 2021, 14, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staffell, I.; Pfenninger, S. Using Bias-Corrected Reanalysis to Simulate Current and Future Wind Power Output. Energy 2016, 114, 1224–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kryzia, D.; Olczak, P.; Wrona, J.; Kopacz, M.; Kryzia, K.; Galica, D. Dampening Variations in Wind Power Generation Through Geographical Diversification. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 214, 12038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuru, S.K.V.S.; Ramana, M. V Wind Power Potential over India Using the ERA5 Reanalysis. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 56, 103038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.; Schindler, D. On the Influence of Wind Speed Model Resolution on the Global Technical Wind Energy Potential. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 156, 112001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil Ruiz, S.A.; Barriga, J.E.C.; Martínez, J.A. Wind Power Assessment in the Caribbean Region of Colombia, Using Ten-Minute Wind Observations and ERA5 Data. Renew. Energy 2021, 172, 158–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enercon E-53. Available online: https://en.wind-turbine-models.com/turbines/530-enercon-e-53 (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- Enercon-E115. Available online: https://pl.wind-turbine-models.com/turbines/832-enercon-e-115-3.000 (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) ERA5: Fifth Generation of ECMWF Atmospheric Reanalyses of the Global Climate. 2017. Available online: https://www.ecmwf.int/en/forecasts/dataset/ecmwf-reanalysis-v5 (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- Copernicus ERA5 Hourly Data on Single Levels from 1979 to Present. Available online: https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/dataset/reanalysis-era5-single-levels?tab=overview (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- ECMWF 2 Metre Temperature. Available online: https://apps.ecmwf.int/codes/grib/param-db?id=167 (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- MERRA Wind MERRA II. Available online: https://www.renewables.ninja (accessed on 30 December 2022).

- O’Sullivan, B.; Chalhoub-Deville, M. Language Testing for Migrants: Co-Constructing Validation. Lang. Assess. Q. 2021, 18, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, K.N.; Rangnekar, S.; Sudhakar, K. Comparative Study of Isotropic and Anisotropic Sky Models to Estimate Solar Radiation Incident on Tilted Surface: A Case Study for Bhopal, India. Energy Rep. 2015, 1, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floors, R.; Nielsen, M. Estimating Air Density Using Observations and Re-Analysis Outputs for Wind Energy Purposes. Energies 2019, 12, 2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boretti, A.; Castelletto, S. Cost of Wind Energy Generation Should Include Energy Storage Allowance. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulpa, J.; Olczak, P.; Stecuła, K.; Sołtysik, M. The Impact of RES Development in Poland on the Change of the Energy Generation Profile and Reduction of CO2 Emissions. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PSE Praca KSE-Generacja Źródeł Wiatrowych i Fotowoltaicznych. Doba Handlowa: 2022-07-25. Available online: https://www.pse.pl/dane-systemowe/funkcjonowanie-kse/raporty-dobowe-z-pracy-kse/generacja-zrodel-wiatrowych (accessed on 20 July 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).