Evolution and Key Differences in Maturity Models for Industrial Digital Transformation: Focus on Industry 4.0 and 5.0

Abstract

1. Introduction

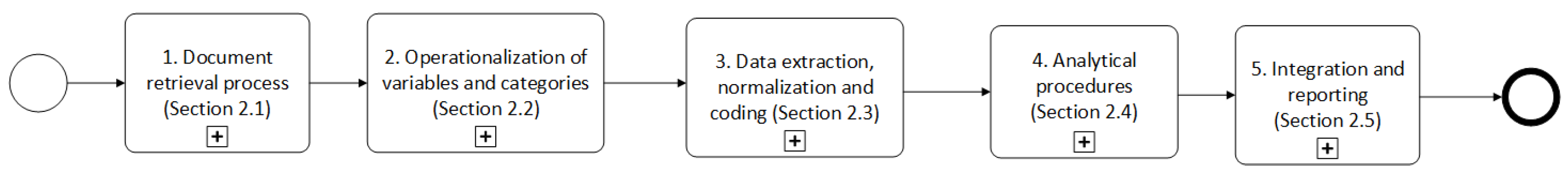

2. Materials and Methods

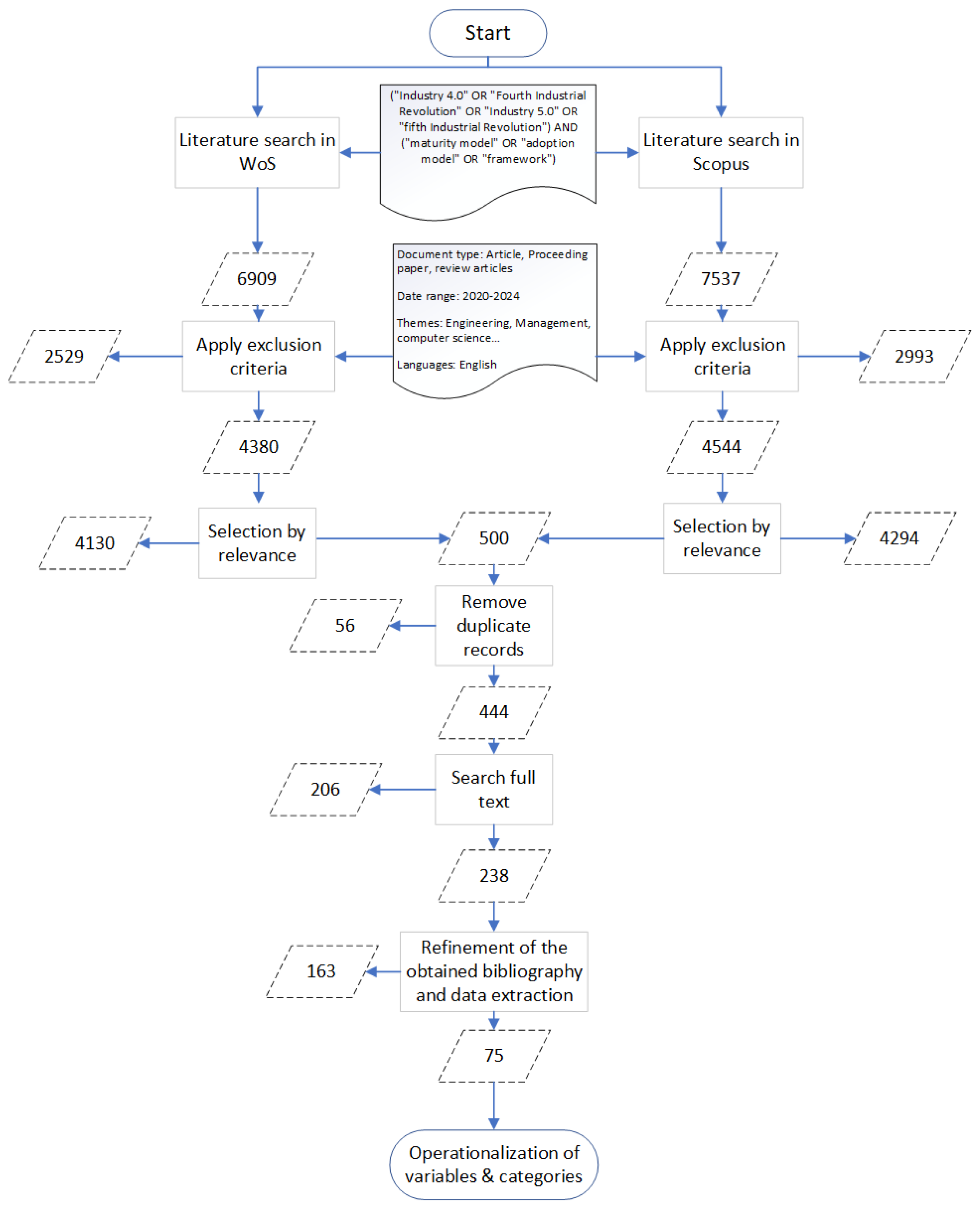

2.1. Document Retrieval Process (RQ1–RQ4, Review Framework)

("Industry 4.0"’ OR "Fourth Industrial Revolution"’ OR "Industry 5.0"’ OR "Fifth Industrial Revolution"’) AND ("maturity model"’ OR "adoption model"’ OR "‘framework"’)

2.2. Operationalization of Variables and Categories

2.2.1. V1—Temporality and Evolution

- Operational definition: Temporal evolution of the model. Enables estimation of relevance, update frequency, and possible I4.0→I5.0 transitions, allowing interpretation of trends and relationships with other variables.

- Unit/measurement: Model; numerical/mixed.

- Recording structure: year_pub (YYYY)

- Boundary rules:

- If multiple editions exist, the version valid during 2020–2024 is used.

- In cases with ambiguous dates, the DOI or the repository date of the cited version is prioritized.

- Evidence: Editorial metadata (DOI/date), version notes, forewords, or “Version/Revision History” sections.

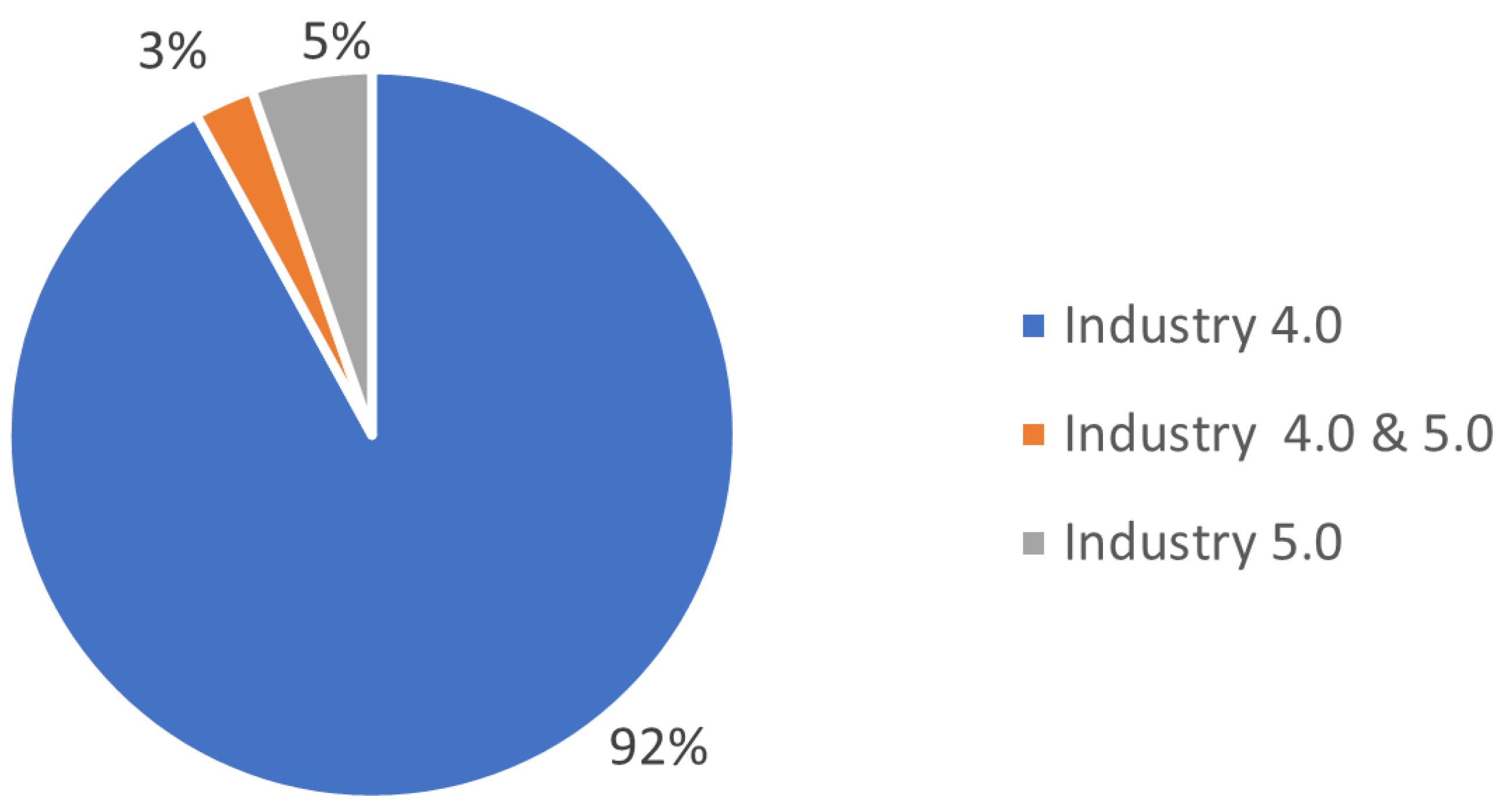

2.2.2. V2—Industry 4.0/5.0 Scope

- Operational Definition: This variable captures how each maturity model is positioned along the I4.0→I5.0 transition. It is coded at the model level in one of three mutually exclusive categories: Industry 4.0, Hybrid, or Industry 5.0.

- Unit/Measurement: Model; nominal.

- Coding Principle: The category is assigned based on the evaluative content of the instrument (dimensions, items, indicators, levels), not only on the conceptual labels used in the title or introduction.

- Categories:

- −

- Industry 4.0 (I4.0): Models centred on digital technologies, automation, data and processes/organization (e.g., IoT, CPS, analytics, automation, smart manufacturing), with no explicit indicators on human-centricity, sustainability or resilience. These aspects may be mentioned in the narrative, but they are not part of the scoring structure.

- −

- Hybrid (I4.0 & I5.0): Models that explicitly refer to people, well-being, ethics, sustainability (e.g., SDGs, ESG) or resilience as aims or principles, but that only incorporate them partially or descriptively in the evaluation (e.g., qualitative comments, non-scored criteria). This category also includes models self-labelled as “Industry 5.0” whose instrument remains predominantly techno-centric.

- −

- Industry 5.0 (I5.0): Models that contain at least one dimension, subdimension or group of items that directly evaluates human-centricity (e.g., ergonomics, skills, participation, privacy/security by design), sustainability (environmental and/or social) and/or resilience (e.g., business continuity, flexibility, recovery capacity), and where these aspects are explicitly integrated into levels, indicators or weights.

- Coding Rules:

- −

- The instrument (dimensions, items, level descriptions) is reviewed before assigning the category.

- −

- If explicit indicators on people, sustainability or resilience are present, the model is coded as I5.0, even if the article only refers to Industry 4.0.

- −

- If such indicators are absent, but human-centric, sustainable or resilient goals are stated as principles, the model is coded as Hybrid.

- −

- If neither indicators nor principles related to I5.0 are identified, the model is coded as I4.0.

- −

- When multiple levels of analysis are reported (e.g., plant, line, supply chain), the most granular level for which an evaluable instrument is provided is used as reference.

- Evidence: Coding decisions are anchored in the instrument’s rubrics, evaluation matrices, scales, and criteria tables.

2.2.3. V3—Covered Maturity Dimensions (Classification)

- Operational Definition: Thematic classification evaluated by the instrument. Allows measurement of breadth (covered areas) and balance (technological vs. socio-organizational), and relates to V2.

- Unit/Measurement: Model; multi-label.

- Dimension Catalog:

- −

- Technology/Digital Infrastructure;

- −

- Processes/Operations/Lean CPS;

- −

- People/Competencies;

- −

- Organization/Governance/Leadership;

- −

- Strategy/Business Model;

- −

- Data/Analytics/AI;

- −

- Customer/Value/Experience;

- −

- Sustainability (E/S/G);

- −

- Security/Cybersecurity/Privacy.

- Boundary Rules:

- A dimension is only coded if it appears in items/criteria/levels.

- Synonyms are mapped to the corresponding family (e.g., “governance” ↔ organization).

- In cases of explicit overlap in the instrument, multiple tags are allowed.

- Evidence: Lists of evaluated dimensions, criteria matrices, or level definitions linked to each dimension.

2.2.4. V4—Number of Maturity Levels

- Operational Definition: Formal progression structure. Estimates diagnostic granularity and comparability across models.

- Unit/Measurement: Model; ordinal/categorical (discrete) or continuous (score).

- Categories:

- −

- Discrete Levels: [36] (6, ≥7)

- −

- Continuous/Score: Continuous scale without discrete levels (e.g., 0–1; 0–100)

- Rule: If levels are present but lack distinguishing criteria, code as discrete and add a note on interpretability risk.

- Evidence: Level definitions, evaluation rubrics, thresholds, or progression tables.

2.2.5. V5—Referenced Digital Technologies

- Operational Definition: Technological footprint of the model (within the instrument). Allows profiling of the evaluated stack, detecting coverage biases (e.g., excessive focus on automation vs. data), and linking to V2 and V3.

- Unit/Measurement: Model; multi-label.

- Technology Catalog:

- −

- IoT/CPS: Sensors, IIoT gateways, IT/OT integration, protocols (OPC UA, MQTT), real-time monitoring.

- −

- Cloud/Edge: Cloud/edge deployments, hybrid architecture, service orchestration/provisioning.

- −

- Big Data/Analytics: Data pipelines, quality, lakes/warehouses, descriptive/predictive/prescriptive analytics.

- −

- AI/ML: Applied models (maintenance, quality, planning), MLOps.

- −

- Robotics/AMR/Cobots: Industrial/collaborative robots, AGV/AMR, robotic cells, collaborative safety.

- −

- Simulation/Digital Twin: Process/discrete simulation; connected digital twin (data/state synchronization).

- −

- AR/VR/MR (XR): Operational guidance, training, remote assistance, 3D visualization.

- −

- Additive Manufacturing: 3D printing (polymers/metals), prototyping, direct production.

- −

- Blockchain (DLT): Immutable traceability, smart contracts, data integrity.

- −

- Cybersecurity: Vulnerability management, access control, hardening, continuity, privacy.

- Key Rule: To be marked as “present,” the technology must be integrated into items/criteria/indicators or levels (e.g., checklists, rubrics, KPIs, weighting). Contextual mentions do not count.

- Evidence: Specific items/indicators from the instrument, evaluation tables, or level definitions requiring the technology.

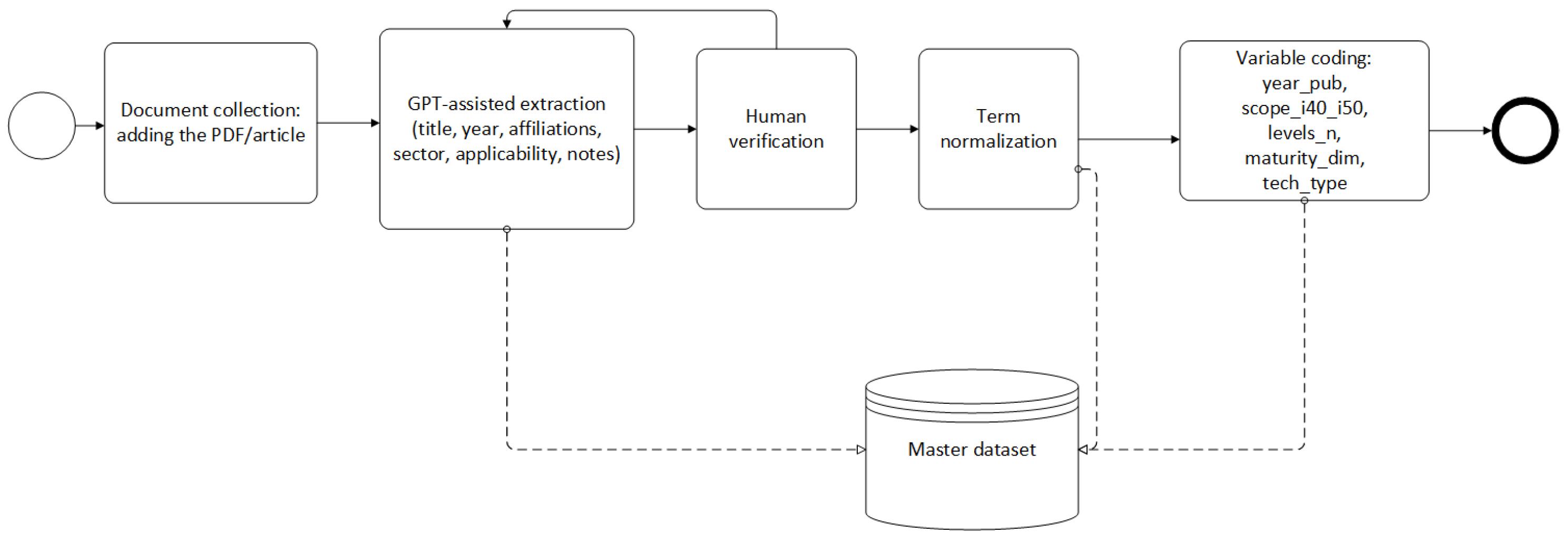

2.3. Data Extraction and Coding (RQ.1–RQ.4)

2.4. Analytical Procedures

2.4.1. Univariate Descriptive Statistics (RQ.1–RQ.4)

- For single-category variables (e.g., scope_i40_i50, levels_type), percentages were calculated based on valid N (i.e., models with available data).

- For multi-label variables (e.g., dim_*, tech_*), a single model may be tagged with multiple categories; therefore, the sum of percentages may exceed 100%.

2.4.2. Temporal Analysis (RQ.1)

- Each model was assigned its year of publication (year_pub).

- In cases of multiple editions, the version valid within 2020–2024 was considered.

2.4.3. Descriptive Cross-Tabulations and Exploratory Inferential Analysis (RQ.3–RQ.4)

- scope_i40_i50 × dimensions;

- scope_i40_i50 × type/number of levels;

- scope_i40_i50 × technologies.

2.4.4. Normalization of Dimensions (V3) and Level Structure (V4)

Dimension Grouping (V3)

- Semantic analysis: evaluation of each dimension’s meaning to detect similarity patterns (keywords and context in the Industry 4.0 ecosystem). For instance, “Cybersecurity” and “Security and Governance” were grouped due to their shared aim of protecting systems, data, and processes.

- Thematic classification: identification of broad categories (technology, processes, people, sustainability, etc.) as transversal axes. Terms such as “Technology”, “Digitalization”, and “IoT” were grouped under Technology and Digitalization.

- Functional relationships: assessment of how each dimension contributes to broader goals; e.g., “Smart Processes” and “Lean Production” grouped under Processes and Operations (operational efficiency).

- Hierarchical abstraction: association of specific dimensions with broader categories according to specificity; e.g., “Workforce Training” and “Human Resource Development” within People and Competencies.

- Alignment with reference frameworks: consideration of recognized pillars in the literature and frameworks (e.g., RAMI 4.0) to structure categories into strategic areas; e.g., “Big Data” and “Artificial Intelligence” in Technology and Digitalization.

- Intersection and multidimensionality: when a term could fit multiple categories, assignment favored the primary purpose, acknowledging cross-cutting concepts such as Sustainability and Social Responsibility.

- Parsimony and clarity: unification of near-synonyms to avoid redundancy; e.g., “Material Flow Automation” and “Automation” normalized under Technology and Digitalization.

Level Structure Coding (V4)

Outputs for Subsequent Analysis

2.4.5. Visual Representations (RQ1–RQ4)

- Bar Charts (simple, stacked, or grouped): Used to show differences in prevalence between categories.

- −

- Stacked bars describe the internal composition of each category.

- −

- Grouped bars present side-by-side comparisons across subcategories.

Charts are typically sorted from highest to lowest frequency. Labels are expressed as percentages when the denominator corresponds to each group’s total, or as raw counts when absolute volume is of interest. - Line Charts (2020–2024 series):

- −

- These are used to depict year-over-year changes with a single axis.

- −

- The same axis range is maintained across comparable charts.

- −

- The number of models per year (annual N) is indicated.

Dual axes and 3D effects are not used. - Matrices/Heatmaps:

- −

- These summarize patterns in descriptive cross-tabulations with multiple category combinations.

- −

- The color scale is adjusted by row or column based on the reported percentage and includes a legend.

2.5. Integration and Reporting

3. Declaration of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

4. Results

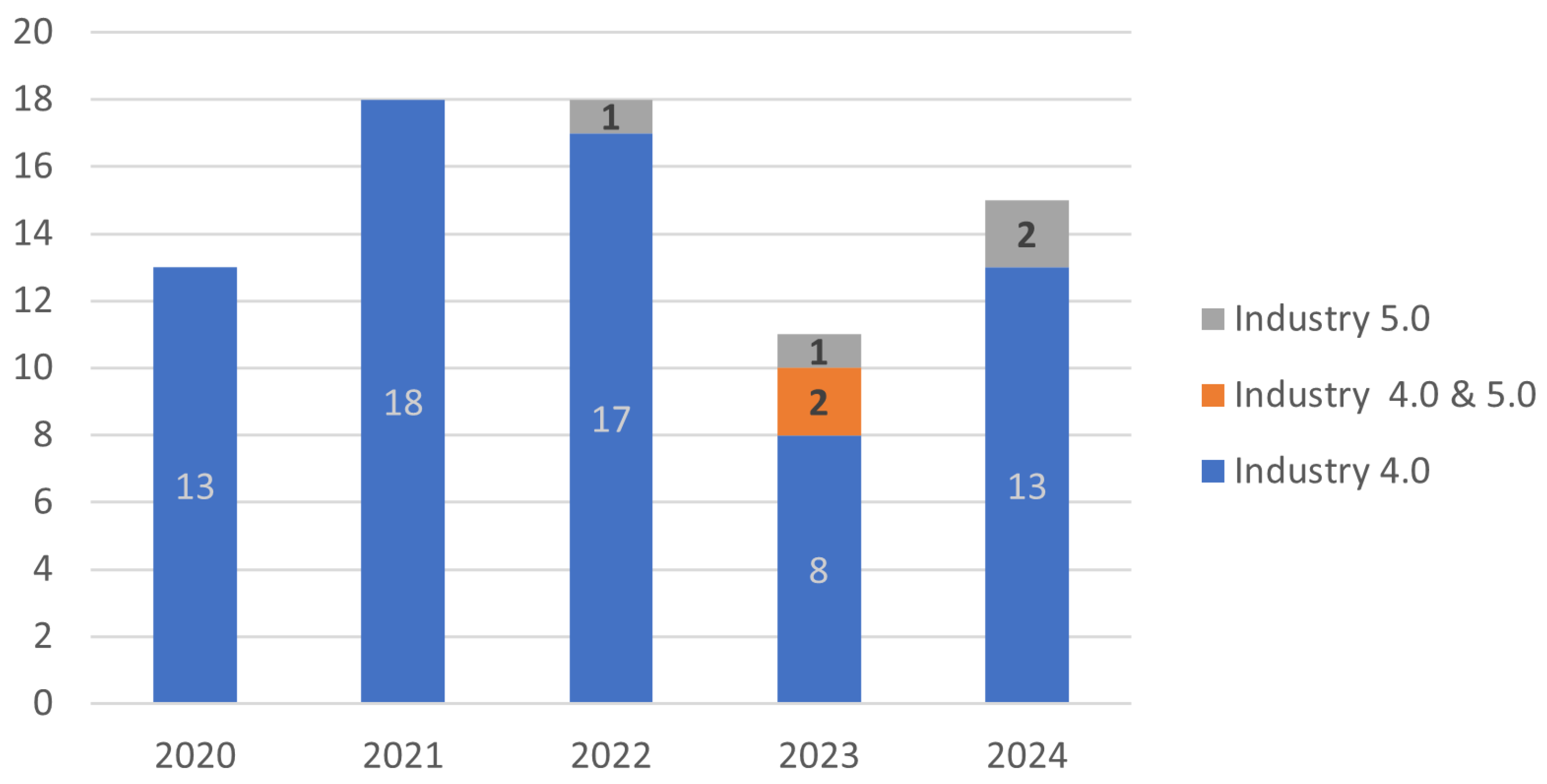

4.1. RQ.1 How Have Industry 4.0 and 5.0 Maturity Models Evolved Between 2020 and 2024?

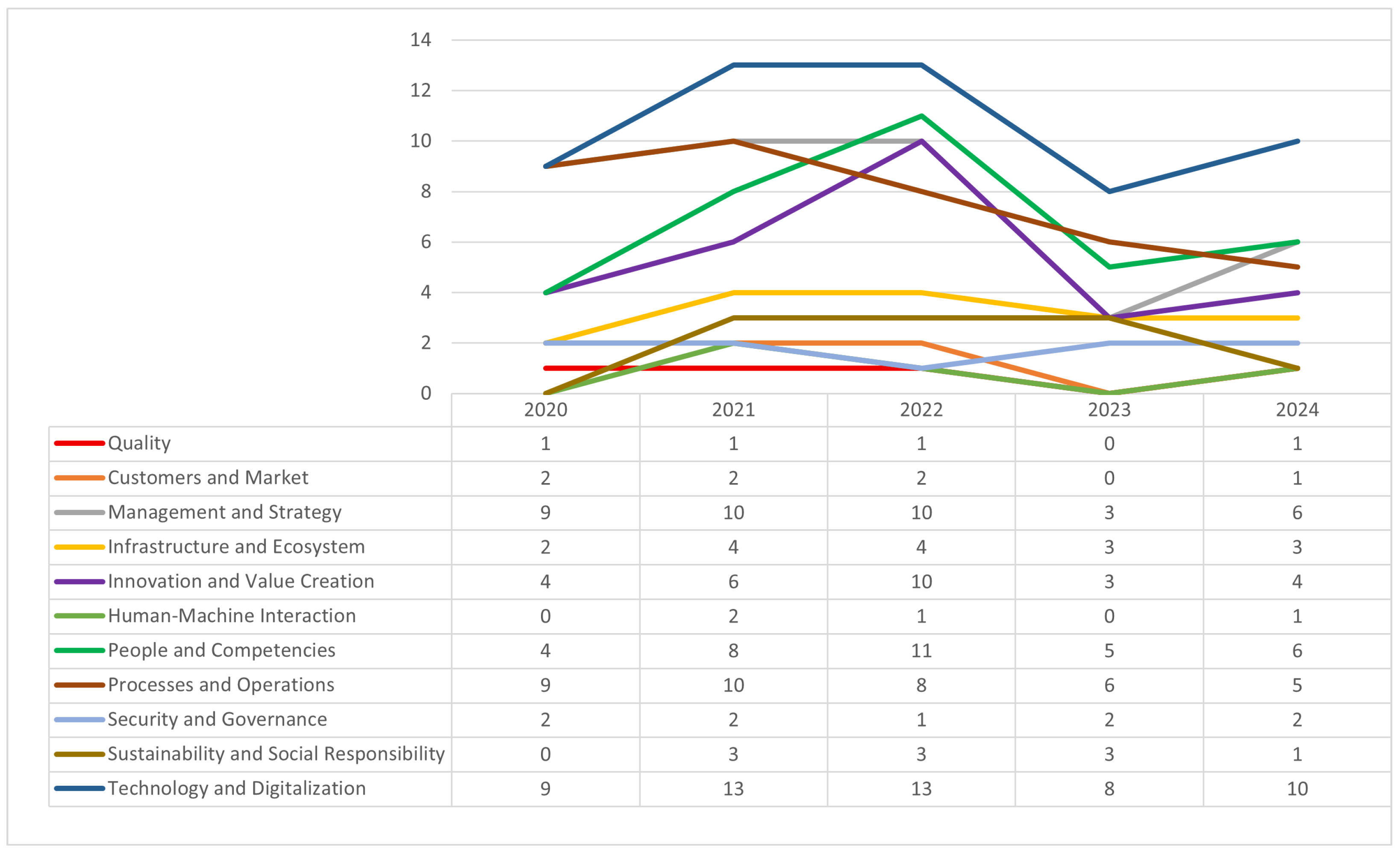

4.2. RQ.2 Are There Significant Differences in the Dimensions Evaluated Between Industry 4.0 and 5.0 Maturity Models?

- Technological vs. human-sustainable focus: Models classified as Industry 4.0 (predominant until 2021–2022) focused heavily on digitization, automation, and efficiency. This explains why dimensions such as Technology, Processes, and Strategy dominated those years. Industry 4.0 involved extensive digitization and automation of production using IoT, AI, robotics, etc., aiming for increased productivity and real-time decision-making. In contrast, Industry 5.0 (conceptualized from 2021 onwards) complements 4.0 by emphasizing environmental sustainability, resilience, and human-centricity. Consequently, dimensions directly related to these new emphases (Sustainability, Human–Machine Interaction) only appear as the Industry 5.0 agenda takes hold. This reinforces the correlation: it is not coincidental that these dimensions emerged prominently from 2021–2022; they reflect the new vision encouraging industry to adopt technology in a human-centric and sustainable way. For example, Industry 5.0 promotes “optimizing Human–Machine Interactions” and “making production respectful of planetary boundaries” [38], precisely what the Human–Machine Interaction and Sustainability dimensions evaluate in a maturity model.

- Progressive integration: Initially, models were purely Industry 4.0 (all models in 2020 and most from 2021–2022). However, even before explicit “5.0” models existed, some models from 2021 already included sustainability within a 4.0 context. This suggests a gradual transition: authors of 4.0 models voluntarily began incorporating sustainability and human factors, anticipating their growing relevance. The first explicitly Industry 5.0 model emerged in 2022, and by 2023, more hybrid 4.0/5.0 or pure 5.0 models appeared, solidifying these dimensions. The increasing prominence of People and Competencies also aligns with Industry 5.0’s vision of empowering workers rather than replacing them, highlighting employee training and well-being as keys to maturity [38]. This indicates that the boundary between 4.0 and 5.0 in maturity models is fluid: during 2021–2022, elements of both paradigms coexisted until formal 5.0 models emerged.

- Persistence of 4.0 foundations: Despite the arrival of new approaches, core Industry 4.0 dimensions remain intact. Technology and Digitalization continue to be omnipresent (even Industry 5.0 models include them since technological foundations remain essential). Processes and Operations, and Management and Strategy, though fluctuating, still feature prominently in many models. This aligns with the notion that Industry 5.0 complements rather than replaces 4.0. That is, Industry 5.0 advancements add layers (sustainability, resilience, human-centric approach) built upon the platform established by 4.0 (digitization, automation). For example, an Industry 5.0 maturity model evaluates both how digitized the company is (a legacy dimension from 4.0) and how sustainable or human-centered it is (new dimensions from 5.0). In summary, coexistence is evident: during 2023–2024, the few Industry 5.0 models still assess technological and process maturity while incorporating new criteria.

- Shifts in priority: However, adjustments in relative importance are noticeable. In recent years, driven by Industry 5.0, sustainability transitioned from nonexistence to prominence in advanced models, while dimensions like Quality lost explicit relevance. This suggests models adapt their focus according to current priorities. Quality was foundational in traditional industrial models but might now be implicitly assumed or integrated within operations in the digital-sustainable era. Conversely, sustainability emerges as a new cornerstone. Thus, the evolution of dimensions reflects the industry’s shifting goals: from seeking efficiency and quality (Industry 4.0) toward additionally emphasizing sustainability and resilience (Industry 5.0). As a reference, the European Commission highlights that industry should now “accelerate innovative change” and provide prosperity “while respecting planetary boundaries and placing worker well-being at the center,” a message clearly influencing maturity models post-2021 [38].

4.3. RQ.3 Is There a Significant Relationship Between the Number of Levels in Industry 4.0 and 5.0 Maturity Models and the Dimensions Evaluated Within These Models?

4.3.1. Relationship Analysis Between Dimensions and Proposed Maturity Levels

4.3.2. Exploratory Inferential Analysis of Level Structure and Dimensional Breadth

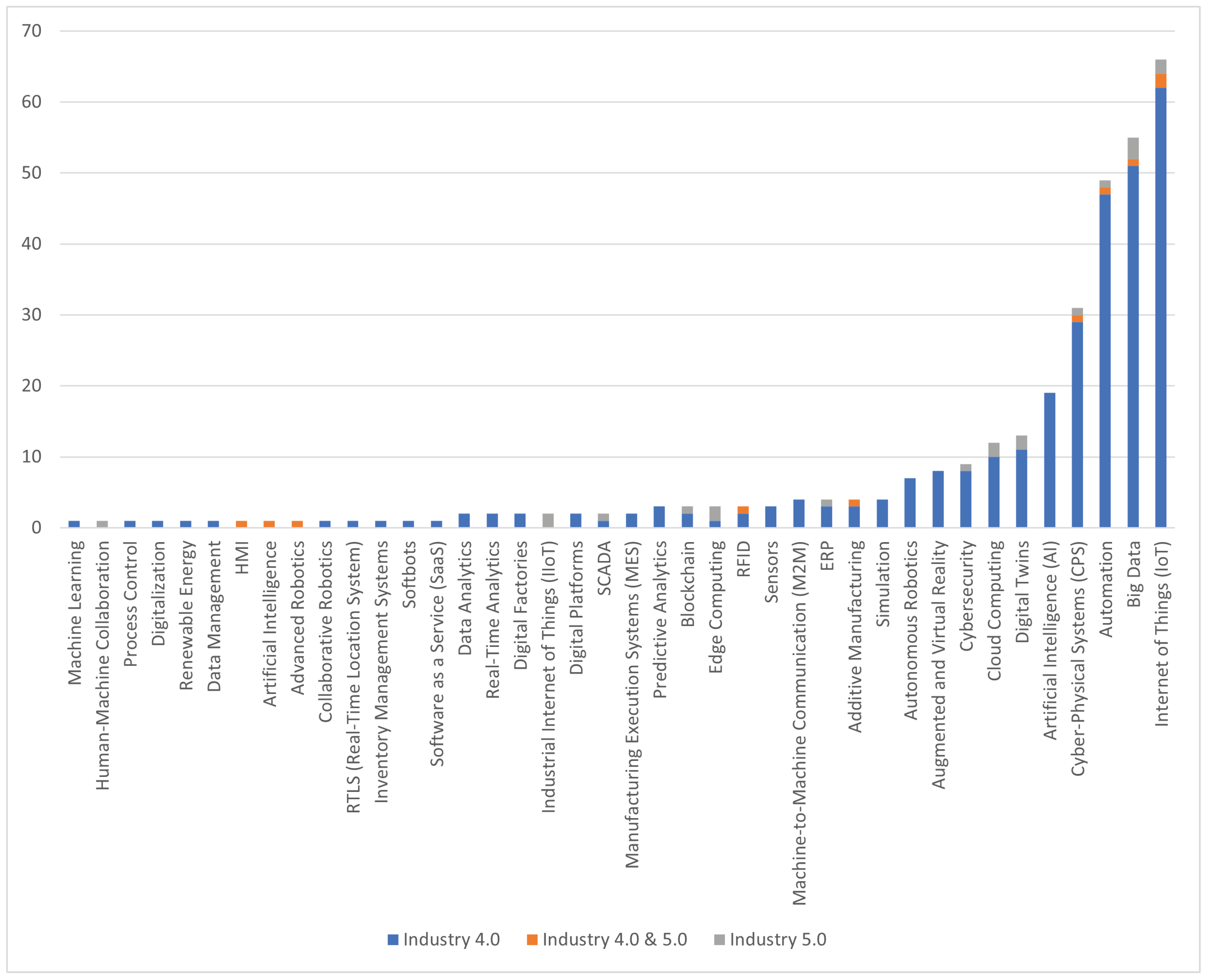

4.4. RQ.4 What Are the Most Frequently Incorporated Enabling Technologies in Industry 4.0 and 5.0 Maturity Models?

Industry 4.0 Models: Focus on Connectivity and Data

Industry 5.0 Models: Focus on Collaboration and Resilience

Transition Between Industry 4.0 and 5.0 Enabling Technologies

Evolution of Enabling Technologies (2020–2024)

5. Discussion

5.1. RQ.1 How Have Industry 4.0 and 5.0 Maturity Models Evolved Between 2020 and 2024?

- Human-Centricity. Maturity assessment should capture the quality of human–machine collaboration, control and decision-making distribution, work design and ergonomics, along with physical and psychological safety, privacy and data protection for employees, and active participation of workers in co-design and continuous improvement. This focus shifts away from the techno-centric logic of I4.0 toward a framework where workers are central actors in value creation.

- Sustainability. Maturity should reflect the integration of environmental principles into strategy and processes, including eco-design, resource efficiency, circularity, and climate impact management across the lifecycle, with traceability and transparency throughout the value chain. This shift aligns operational performance with planetary boundaries and growing societal and regulatory expectations [45,46].

- Resilience. In response to shocks and disruptions, maturity must incorporate the capabilities of anticipation, absorption, adaptation, and recovery, both in operations and in supply chains and digital systems. This includes organizational preparedness, business continuity, cybersecurity, process flexibility, and post-event learning as design components, not merely tactical responses. Thus, resilience, previously peripheral in I4.0, becomes a structural priority in I5.0.

5.2. RQ.2. Are There Significant Differences in the Evaluated Dimensions Between Industry 4.0 and 5.0 Maturity Models?

- Regulatory and societal pressure, particularly after 2021, pushing for the explicit integration of sustainability, well-being, and ethics in maturity assessments.

- Exogenous shocks, which prioritized operational continuity, supply chain robustness, and cyber-resilience, elevating resilience from a “tacit requirement” to a design dimension.

- Learning about human–machine collaboration, which shifted automation “for” humans to automation “with” humans—impacting competencies, ergonomics, safety, and data governance.

- Path dependency, where the continuity of I4.0’s digital core explains why Technology and Processes remain central even in I5.0 models: I5.0 redirects objectives, but does not dismantle capabilities.

5.3. RQ.3 Is There a Significant Relationship Between the Number of Levels in Industry 4.0 and 5.0 Maturity Models and the Evaluated Dimensions?

5.4. RQ.4 What Are the Most Frequently Incorporated Enabling Technologies in Industry 4.0 and 5.0 Maturity Models?

5.5. Underlying Mechanisms: Policy Agendas, Epistemic Communities, and Diffusion

6. Limitations and Future Work

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| I4.0 | Industry 4.0 |

| I5.0 | Industry 5.0 |

| RQ | Research Question |

| WoS | Web of Science |

| SME/SMEs | Small and Medium-sized Enterprise/Enterprises |

| MM | Maturity Model |

| CPS | Cyber–Physical System(s) |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| IIoT | Industrial Internet of Things |

| IT/OT | Information Technology/Operational Technology |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MLOps | Machine Learning Operations |

| DT | Digital Twin |

| AR | Augmented Reality |

| VR | Virtual Reality |

| MR | Mixed Reality |

| XR | Extended Reality |

| AM | Additive Manufacturing (3D printing) |

| AGV | Automated Guided Vehicle |

| AMR | Autonomous Mobile Robot |

| HMI | Human–Machine Interaction/Interface |

| ESG | Environmental, Social and Governance |

| CSR | Corporate Social Responsibility |

| DLT | Distributed Ledger Technology (Blockchain) |

| KPI | Key Performance Indicator |

| RAMI 4.0 | Reference Architectural Model for Industry 4.0 |

| OPC UA | Open Platform Communications Unified Architecture |

| MQTT | Message Queuing Telemetry Transport |

Appendix A. Corpus of Analyzed Maturity Models (MM.01–MM.75)

| ID | Maturity Model | Scope | Reference | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MM.01 | RA–RE–RI–RO Maturity Model (Production Management as-a-Service) | Industry 4.0 | Abner et al. [53] | 2020 |

| MM.02 | IMPULS | Industry 4.0 | Alcácer et al. [54] | 2022 |

| MM.03 | Maturity Framework for SMEs in Industry 4.0 | Industry 4.0 | Amaral and Peças [55] | 2021 |

| MM.04 | I4.0 MM | Industry 4.0 | Angreani et al. [39] | 2024 |

| MM.05 | Fuzzy Maturity Model | Industry 5.0 | Bajic et al. [56] | 2023 |

| MM.06 | Agca et al. (2017) Maturity Model applied to inventory management | Industry 4.0 | Barbalho and Dantas [57] | 2021 |

| MM.07 | Warehouse 4.0 Maturity Model for SMEs | Industry 4.0 | Benmimoun et al. [58] | 2024 |

| MM.08 | Industry 4.0 with Industry 5.0 aspects (sustainability) | Industry 4.0 & 5.0 | Bernhard and Zaeh [48] | 2023 |

| MM.09 | Maturity Model for SMEs in Industry 4.0 | Industry 4.0 | Bohorquez and Gil-Herrera [59] | 2022 |

| MM.10 | ECO Maturity Model | Industry 4.0 | Bretz et al. [60] | 2022 |

| MM.11 | Fuzzy-logic-based Maturity Model for OSCM | Industry 4.0 | Caiado et al. [61] | 2021 |

| MM.12 | Industry 4.0 Maturity Model (Portugal) | Industry 4.0 | Castelo-Branco et al. [62] | 2022 |

| MM.13 | Smart Logistics Maturity Model for SMEs | Industry 4.0 | Chaopaisarn and Woschank [63] | 2021 |

| MM.14 | Maturity Model for Industry 4.0 adoption in Passenger Railway Companies | Industry 4.0 | Chaves Franz et al. [64] | 2024 |

| MM.15 | Modular Maturity Model for Industry 4.0 | Industry 4.0 | Çinar et al. [65] | 2021 |

| MM.16 | IPM (Industry 4.0 Perception Maturity) | Industry 4.0 | Ciravegna-Martins-da fonseca et al. [66] | 2024 |

| MM.17 | Maturity Model for General Contractors in Industry 4.0 | Industry 4.0 | Das et al. [67] | 2024 |

| MM.18 | S3RM Maturity Model for smart and sustainable supply chains | Industry 4.0 & 5.0 | Demir et al. [49] | 2023 |

| MM.19 | Maturity Model based on TQM | Industry 4.0 | Elibal and Özceylan [68] | 2024 |

| MM.20 | Diagnostics of Opportunities – Maturity Model for Digital Transformation | Industry 4.0 | Ericson Öberg et al. [69] | 2024 |

| MM.21 | Maturity Model for Logistics 4.0 | Industry 4.0 | Facchini et al. [70] | 2020 |

| MM.22 | 3D-CUBE Readiness Model for Industry 4.0 | Industry 4.0 | Felippes et al. [36] | 2022 |

| MM.23 | FITradeoff Industry 4.0 Maturity Model | Industry 4.0 | Ferreira et al. [71] | 2024 |

| MM.24 | Data Science Maturity Model (DSMM) | Industry 4.0 | Gökalp et al. [72] | 2021 |

| MM.25 | Industry X.0 Fuzzy Inference Engine | Industry 4.0 | Gomes and Basilio [73] | 2024 |

| MM.26 | Maturity Model for sPSS | Industry 4.0 | Heinz et al. [74] | 2022 |

| MM.27 | Deloitte-based Digital Maturity Model | Industry 4.0 | Herceg et al. [42] | 2020 |

| MM.28 | Singapore Smart Industry Readiness Index (SIRI) adapted to the Moroccan textile industry | Industry 4.0 | Jamouli et al. [75] | 2023 |

| MM.29 | Upper Austria Industry 4.0 Maturity Model | Industry 4.0 | Kieroth et al. [43] | 2022 |

| MM.30 | Maturity model for digital transformation in the manufacturing industry | Industry 4.0 | Kırmızı and Kocaoglu [76] | 2022 |

| MM.31 | Maturity model to improve company performance through Industry 4.0 | Industry 4.0 | Koldewey et al. [77] | 2022 |

| MM.32 | Capability-based maturity model for smart manufacturing | Industry 4.0 | Lin et al. [78] | 2020 |

| MM.33 | Singapore Smart Industry Readiness Index (SIRI) | Industry 4.0 | Lin et al. [79] | 2020 |

| MM.34 | Digital Twin Maturity Model (DTMM) | Industry 4.0 | Liu et al. [80] | 2024 |

| MM.35 | Innovative Capability Maturity Model | Industry 4.0 | Lookman et al. [81] | 2022 |

| MM.36 | COMMA 4.0 (Comprehensive I4.0 Maturity Assessment Model) | Industry 4.0 | Lukhmanov et al. [82] | 2022 |

| MM.37 | Maturity Framework for Readiness toward Industry 5.0 | Industry 5.0 | Madhavan et al. [83] | 2024 |

| MM.38 | Maturity model for MSMEs in Industry 4.0 | Industry 4.0 | Magdalena et al. [84] | 2021 |

| MM.39 | Industry 4.0 Maturity Index | Industry 4.0 | Magnus [85] | 2023 |

| MM.40 | Lean Smart Maintenance Maturity Model (LSM MM) | Industry 4.0 | Maier et al. [86] | 2020 |

| MM.41 | I4.0 Competency Maturity Model (I4.0CMM) | Industry 4.0 | Maisiri et al. [87] | 2021 |

| MM.42 | Maturity Model for Industry 4.0 integration in any company | Industry 4.0 | Melnik et al. [88] | 2020 |

| MM.43 | Maturity Model for the Autonomy of Manufacturing Systems | Industry 4.0 | Mo et al. [89] | 2023 |

| MM.44 | CUDIE Model (Capability to Utilize Data in Industrial Enterprises) | Industry 4.0 | Nausch et al. [90] | 2020 |

| MM.45 | CCMS 2.0 (Company CoMpaSs) with an AI focus | Industry 4.0 | Nick et al. [91] | 2022 |

| MM.46 | Company Compass (CCMS) 2.0 | Industry 4.0 | Nick et al. [92] | 2021 |

| MM.47 | CCMS | Industry 4.0 | Nick et al. [93] | 2020 |

| MM.48 | CCMS2.0e (with AI) | Industry 4.0 | Nick et al. [94] | 2024 |

| MM.49 | TOE-based Digital Maturity Model | Industry 4.0 | P. Senna et al. [95] | 2023 |

| MM.50 | RAISE 4.0 | Industry 4.0 | Pan Nogueras et al. [96] | 2022 |

| MM.51 | VPi4 (Industry 4.0 Index) | Industry 4.0 | Pech and Vrchota [97] | 2020 |

| MM.52 | Process Model for the Implementation of Industry 4.0 Use Cases in SMEs | Industry 4.0 | Peukert et al. [98] | 2020 |

| MM.53 | Maturity Model for Machine Tool Companies | Industry 4.0 | Rafael et al. [99] | 2020 |

| MM.54 | Maturity Model for Smart Manufacturing in SMEs in Malaysia | Industry 4.0 | Rahamaddulla et al. [100] | 2021 |

| MM.55 | SSTRA (Smart SME Technology Readiness Assessment) | Industry 4.0 | Saad et al. [101] | 2021 |

| MM.56 | Maturity Model for Urban Smart Factories | Industry 4.0 | Sajadieh and Noh [102] | 2024 |

| MM.57 | LM4I4.0 Maturity Model for manufacturing SMEs in developing countries | Industry 4.0 | Sajjad et al. [103] | 2024 |

| MM.58 | Industry 4.0 Maturity Model Proposal | Industry 4.0 | Santos and Martinho [104] | 2020 |

| MM.59 | Maturity model for Digital Twins in battery cells | Industry 4.0 | Schabany et al. [37] | 2023 |

| MM.60 | Pay-Per-X Maturity Model (PPX) | Industry 4.0 | Schroderus et al. [105] | 2021 |

| MM.61 | Maturity model to assess the impact of Industry 4.0 on SMEs | Industry 4.0 | Semeraro et al. [106] | 2023 |

| MM.62 | I4MMSME Maturity Model for manufacturing SMEs | Industry 4.0 | Simetinger and Basl [107] | 2022 |

| MM.63 | DigiCoM | Industry 4.0 | Steinlechner et al. [108] | 2021 |

| MM.64 | Readiness Assessment of SMEs in Transitional Economies | Industry 4.0 | Suleiman et al. [109] | 2021 |

| MM.65 | Maturity Model for Worker 4.0 adoption | Industry 4.0 | Treviño-Elizondo and García-Reyes [110] | 2021 |

| MM.66 | ECDMM4.0–Employee Competency Development Maturity Model for Industry 4.0 | Industry 4.0 | Treviño-Elizondo and García-Reyes [111] | 2023 |

| MM.67 | “Maturity Model to Become a Smart Organization based on Lean and I4.0” | Industry 4.0 | Treviño-Elizondo et al. [112] | 2023 |

| MM.68 | Maturity model for digital twins | Industry 4.0 | Uhlenkamp et al. [40] | 2022 |

| MM.69 | SANOL Industry 4.0 Maturity Model | Industry 4.0 | Ünal et al. [113] | 2022 |

| MM.70 | Industry 4.0 Maturity Model for Manufacturing in India | Industry 4.0 | Wagire et al. [114] | 2021 |

| MM.71 | Maturity model for technological integration in industrial companies | Industry 4.0 | Widmer et al. [115] | 2022 |

| MM.72 | Logistics 4.0 Maturity Model | Industry 4.0 | Zoubek and Simon [116] | 2021 |

| MM.73 | Environmental Maturity Model for Industry 4.0 | Industry 4.0 | Zoubek et al. [117] | 2021 |

| MM.74 | Maturity model to assess the automation of production processes | Industry 5.0 | Hetmanczyk [118] | 2024 |

| MM.75 | Maturity model for implementing Logistics 5.0 based on decision-support systems | Industry 5.0 | Trstenjak et al. [119] | 2022 |

Appendix B. GPT Agent Prompt for Data Extraction and Coding (MMs4.0)

- MMs4.0---Interaction Protocol (step-by-step)

- LANGUAGE RULE

- - All interactions with the user must be conducted in the language used in their first message.

- PROCESS RULE

- - The process must proceed step by step, consulting the user before advancing to the next step (explicit confirmation).

- ROLE & SCOPE

- - You are part of a research team responsible for identifying and analyzing maturity models in Industry 4.0 or Industry 5.0 based on the review of PDF articles.

- - Goal: extract relevant information about maturity models defined in the articles or identify mentioned models along with their sources.

- ---

- ### Step 1: Initial Reading of the Title, Abstract, and Keywords

- Objective: Determine whether the article defines a maturity model for Industry 4.0 or 5.0, or mentions existing maturity models.

- Instructions:

- - Review the title, abstract, and keywords.

- - Look for terms such as "Industry 4.0", "Industry 5.0", "maturity model", "digital transformation", etc.

- Actions:

- - If the article defines a maturity model: record the name and a brief description (and proceed to the next step).

- - If the article does not define a model but mentions existing maturity models: identify which ones and record their sources.

- - If the article is not related to maturity models: indicate that it is not relevant for this analysis.

- Example result:

- - "The article defines the ABC Maturity Model for Industry 5.0 adoption."

- - "The article does not define a model but mentions the RAMI 4.0 and Acatech models."

- ---

- ### Step 2: Model Classification

- Objective: Determine whether the model focuses on Industry 4.0, Industry 5.0, or both.

- Instructions:

- - Analyze the content to identify the classification.

- - Look for enabling technologies (I4.0) and for sustainability/human-centric aspects (I5.0).

- Example result:

- - "The model is classified as Industry 4.0, emphasizing technologies such as IoT and Big Data."

- - "The model encompasses Industry 5.0, incorporating sustainability and human---robot collaboration."

- ---

- ### Step 3: Definition and Description of the Maturity Model

- Objective: Understand the structure and purpose of the model.

- Instructions:

- - Find the definition and detailed description of the model.

- - Include diagrams or schematics if available (record figure/table references).

- Example result:

- - "The model proposes five maturity levels, from ‘Initial’ to ‘Optimized,’ focusing on technological and cultural integration."

- ---

- ### Step 4: Identification of Model Elements

- Objective: Detail the key components of the model.

- Instructions:

- - Dimensions or Areas: Identify the assessed areas (e.g., Technology, Processes, People).

- - Maturity Levels: Record the number and description of the levels (e.g., 5 levels).

- - Maturity Indicators: List the indicators or metrics used.

- - Enabling Technologies: Specify the key technologies (e.g., IoT, AI).

- - Implementation Strategies: Mention step-by-step or methodological guides provided.

- Example result:

- - "Dimensions: Strategy, Culture, Technology."

- - "Levels: 4 maturity levels."

- - "Indicators: Process automation, employee training."

- ---

- ### Step 5: Application Sector

- Objective: Identify the industrial sector to which the model applies.

- Instructions:

- - Check whether the article mentions specific sectors such as manufacturing, logistics, healthcare, education, etc.

- Example result:

- - "The model is mainly applied in the automotive manufacturing sector."

- ---

- \#\#\# Step 6: Case Studies or Practical Applications

- Objective: Evaluate applicability and validation of the model.

- Instructions:

- - Look for case studies, experiments, or practical applications mentioned in the article.

- Example result:

- - "A case study reports a 15% productivity increase in a textile company after applying the model."

- ---

- ### Step 7: Consideration of the Developing Country Context

- Objective: Determine whether the model addresses factors specific to developing countries.

- Instructions:

- - Analyze whether the model accounts for limitations such as restricted infrastructure, financial resources, or cultural/educational barriers.

- Example result:

- - "The model adapts recommendations for developing countries, emphasizing low-cost solutions and workforce training."

- ---

- ### Step 8: Model Gaps or Limitations

- Objective: Identify the model’s limitations or areas for improvement.

- Instructions:

- - Record disadvantages or critiques mentioned in the article.

- Example result:

- - "The model does not address cybersecurity aspects."

- - "Lacks empirical validation across different industrial sectors."

- ---

- ### Step 9: Final Validation and Article Classification

- Objective: Determine the article’s relevance and inclusion in the analysis.

- Instructions:

- - Does the article meet the inclusion criteria?

- - Does the model include key elements and consider its application context?

- - What are the article’s shortcomings?

- - Classify the article as Relevant or Not Relevant and justify.

- Example result:

- - "Relevant and included in the comparative analysis; defines a comprehensive maturity model applicable to SMEs in developing countries."

- ---

- ### Step 10: Summary and Presentation of Results

- At the end of the process, prepare a summary in table format (not a spreadsheet), presented horizontally, with the following columns:

- | Identified Maturity Models | Classification (Industry 4.0, 5.0, or both) | Article Reference (APA format) | Application Sector | Identified Dimensions (e.g., logistics, SMEs, manufacturing) | Number of Maturity Levels | Enabling Technologies | Performance Indicators (KPIs) | Evaluation Instruments | Model Gaps or Limitations (from Step 8) | Consideration of the Application Context (Developing countries) | Country of Origin of the Model |

Appendix C. Standardization of Terms Associated with Maturity Dimensions

| Standardized Term | Grouped Terms |

|---|---|

| Quality | Quality; Total Quality Management (TQM); Product Quality |

| Customers and Market | Customer; Customer Experience; Customers and Markets; Market Orientation; Supplier Relationships; Culture and Customer; Customer Requirements; Relationship with External Actors; Customers and Suppliers |

| Management and Strategy | Alignment with Reference Architectures; Supply Chain; Organizational Capabilities; Culture; Strategy; Asset Strategy; Digital Strategy; Organizational Strategy; Organizational Structure; Strategy and Culture; Strategy and Management; Strategy and Leadership; Strategy and Organization; Organizational Structure; Philosophy and Objectives; Finance; Management; Strategy Management; Resource Management; Change Management; Organizational Change Management; Knowledge Management; Smart Governance; Leadership and Strategy; Management 4.0; Organization; Support Processes; Organizational Processes |

| Infrastructure and Ecosystem | Ecosystem; Interconnected Ecosystems; Environment; Factory 4.0; Smart Factory; Smart Factories; Infrastructure; Digital Infrastructure; Technological Infrastructure; Logistics 4.0; Autonomous Manufacturing; Connected Manufacturing; Virtual Manufacturing; Physical World; Operator 4.0 |

| Innovation and Value Creation | Value Chain; Innovation Capabilities; Transformation Capabilities; Self-X Capabilities; Expert Human Knowledge; Value Creation; Innovation; Technological Innovation; Innovation and Governance; Intelligence; Continuous Improvement; Business Model; Product; Smart Products; Products and Development; Products and Services; Smart Products and Services; Value Realization; Business Results; Data-Based Services; Servitization; Value |

| Human–Machine Interaction | Human–Machine Interaction; Human-Machine Collaboration; Man; Machine; Human-Machine Interface |

| People and Competencies | Adaptability; Continuous Learning; Human Capabilities; Technical Capabilities; Training; Workforce Training; Human Capital; Collaboration and Communication; Competencies; Worker Competencies; Methodological Competencies; Non-Technical Competencies; Problem-Solving Competencies; Personal Competencies; Activity-Related Competencies; Social and Personal Competencies; Socio-Communicative Competencies; Socio-Communicative and Personal Competencies; Technical Competencies; Communication; Corporate Culture; Organizational Culture; Culture and People; Workforce Development; Human Dimension; Employees; Employees and Corporate Culture; Empowerment; Human-Centric Approach; Workforce; Skills and Capabilities; Business Integration; Interactions; Operability; Participation; People; People and Competencies; People and Culture; Human Resources |

| Processes and Operations | Storage; Material Flow Automation; Intelligent Supply Chain; Production Capacity; Process Capabilities; Asset Communication; Dispatch; Operational Efficiency; Flexibility; Information Flow; Material Flow; Operations Management; Routine Management; Product Identification; Industry 4.0; Lean Production; Logistics; Process Maturity; Maintenance; Predictive Maintenance; Manufacturing and Operations; Method; Operations; Smart Operations; Intelligent Operation; Process Optimization; Planning; Order Preparation; Process; Integrated Processes; Smart Processes; Lean Processes; Operational Processes; Production; Goods Reception; Operational Results; Rotation; Management Systems; Production Data Usage |

| Security and Governance | Cybersecurity; Data and Security; Governance; Data Governance; Performance Measurement; Security and Governance |

| Sustainability and Social Responsibility | Government Support; Support and Incentives; Product Lifecycle; Competitiveness and Sustainability; Legal Considerations; Socioeconomic Context; Industry 1.0–5.0 Practices; Profitability; Resilience; Social Responsibility; Service; Sustainability; Environmental Sustainability |

| Technology and Digitalization | Adoption of 4.0 Technologies; Adoption of Enabling Technologies; Smart Storage; Data Analytics; Automation; Big Data; Technological Capability; Computational Capabilities; Analytics Capabilities; Data Management Capabilities; IT Management Capabilities; Simulation Capabilities; Digital Capabilities; Technological Capabilities; Digital Competencies; Connectivity; Control; CPS; Data; Data Information and Knowledge; Data and Technology; Digitalization; Process Digitalization; Design Execution; Equipment; Design System Flexibility; Data Management; Data and Analytics Management; Technology Management; AI in Value Chain; AI and Self-Adjustment; Integration; Systems Integration; Digital Integration; Digital Intelligence; Interoperability; IoT; IT; Technological Maturity; Virtual Modeling; Virtual World; Business; Automation Level; Objects; Design Principles; Virtual Processes; Data Collection and Analysis; Simulation; Real-Time Design System; Technology; Technology and Data; Advanced Technologies; Industry 4.0 Technologies; ICT; Data-Driven Decision Making; Smart Work; Digital Transformation; Data Usage |

References

- Mathur, A.; Dabas, A.; Sharma, N. Evolution from industry 1.0 to industry 5.0. In Proceedings of the 2022 4th International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communication Control and Networking (ICAC3N), Greater Noida, India, 16–17 December 2022; pp. 1390–1394. [Google Scholar]

- Borda, Z. Historical evolution of industrial robotization: From the first industrial revolution to Industry 5.0. Proc. Int. Bus. Inf. Manag. Assoc. Conf. 2024, 2024, 4343024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcácer, V.; Cruz-Machado, V. Scanning the industry 4.0: A literature review on technologies for manufacturing systems. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2019, 22, 899–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamwal, A.; Agrawal, R.; Sharma, M.; Giallanza, A. Industry 4.0 technologies for manufacturing sustainability: A systematic review and future research directions. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oztemel, E.; Gursev, S. Literature review of Industry 4.0 and related technologies. J. Intell. Manuf. 2020, 31, 127–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.D.; Xu, E.L.; Li, L. Industry 4.0: State of the art and future trends. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 2941–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Ardolino, M.; Bacchetti, A.; Perona, M. The applications of Industry 4.0 technologies in manufacturing context: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021, 59, 1922–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalsoom, T.; Ramzan, N.; Ahmed, S.; Ur-Rehman, M. Advances in sensor technologies in the era of smart factory and industry 4.0. Sensors 2020, 20, 6783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjödin, D.R.; Parida, V.; Leksell, M.; Petrovic, A. Smart Factory Implementation and Process Innovation: A Preliminary Maturity Model for Leveraging Digitalization in Manufacturing Moving to smart factories presents specific challenges that can be addressed through a structured approach focused on people, processes, and technologies. Res.-Technol. Manag. 2018, 61, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Mabkhot, M.M.; Al-Ahmari, A.M.; Salah, B.; Alkhalefah, H. Requirements of the smart factory system: A survey and perspective. Machines 2018, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Kim, D.; Shin, N. Success factors of the adoption of smart factory transformation: An examination of Korean manufacturing SMEs. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 2239–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, D.H. Trend of Smart Factory and Model Factory Cases. E-Bus. Stud. 2016, 17, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajic, B.; Rikalovic, A.; Suzic, N.; Piuri, V. Industry 4.0 implementation challenges and opportunities: A managerial perspective. IEEE Syst. J. 2020, 15, 546–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.M.; Kiel, D.; Voigt, K.I. What drives the implementation of Industry 4.0? The role of opportunities and challenges in the context of sustainability. Sustainability 2018, 10, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadayi-Usta, S. An interpretive structural analysis for industry 4.0 adoption challenges. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2019, 67, 973–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Liu, T.; Zhou, L. Industry 4.0: Towards future industrial opportunities and challenges. In Proceedings of the 2015 12th International Conference on Fuzzy Systems and Knowledge Discovery (FSKD), Zhangjiajie, China, 15–17 August 2015; pp. 2147–2152. [Google Scholar]

- Bellandi, M.; De Propris, L.; Santini, E. Industry 4.0+ challenges to local productive systems and place based integrated industrial policies. In Transforming Industrial Policy for the Digital Age; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019; pp. 201–218. [Google Scholar]

- Das, R.; Muduli, K.; Islam, S.M. Industry 4.0 Adoption in Manufacturing Industries in SME sector: Opportunities and Challenges. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Istanbul, Turkey, 7–10 March 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rauch, E.; Matt, D.T. Status of the Implementation of Industry 4.0 in SMEs and Framework for Smart Manufacturing. In Implementing Industry 4.0 in SMEs; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Poór, P.; Basl, J. Overview of current issues in Industry 4.0 implementation. Zarządzanie Przedsiębiorstwem 2018, 21, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ciucu-Durnoi, A.N.; Delcea, C.; Stănescu, A.; Teodorescu, C.A.; Vargas, V.M. Beyond Industry 4.0: Tracing the Path to Industry 5.0 through Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, J.; Sha, W.; Wang, B.; Zheng, P.; Zhuang, C.; Liu, Q.; Wuest, T.; Mourtzis, D.; Wang, L. Industry 5.0: Prospect and retrospect. J. Manuf. Syst. 2022, 65, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trofimova, N. Impact of Industry 5.0 on Industrial Development. Ekon. I Upr. Probl. Resheniya 2023, 2/4, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, A.; Sharma, D. The Development of Manufacturing Industry Revolutions from 1.0 to 5.0. J. Informatics Educ. Res. 2024, 4, 1230–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallat, R.; Hawbani, A.; Wang, X.; Al-Dubai, A.; Zhao, L.; Liu, Z.; Min, G.; Zomaya, A.Y.; Alsamhi, S.H. Navigating industry 5.0: A survey of key enabling technologies, trends, challenges, and opportunities. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2023, 26, 1080–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulongo, N.Y. Industry 5.0 A Novel Technological Concept. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Smart Applications, Communications and Networking (SmartNets), Harrisonburg, VA, USA, 28–30 May 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslanova, I.V.; Kulichkina, A. Digital maturity: Definition and model. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Scientific and Practical Conference “Modern Management Trends and the Digital Economy: From Regional Development to Global Economic Growth” (MTDE 2020); Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 443–449. [Google Scholar]

- Haryanti, T.; Rakhmawati, N.A.; Subriadi, A. The Extended Digital Maturity Model. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2023, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teichert, R. Digital transformation maturity: A systematic review of literature. Acta Univ. Agric. Et Silvic. Mendel. Brun. 2019, 67, 1673–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.H.; Lau, H.K. A critical review of maturity models in information technology and human landscapes on industry 4.0. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 13–15 February 2019; pp. 1575–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basl, J.; Doucek, P. Metamodel of indexes and maturity models for industry 4.0 readiness in enterprises. In Proceedings of the IDIMT 2018: Strategic Modeling in Management, Economy and Society—26th Interdisciplinary Information Management Talks, Kutná Hora, Czech Republic, 5–7 September 2018; Oskrdal, V., Doucek, P., Chroust, G., Eds.; Trauner Verlag Universitat: Linz, Austria, 2018; pp. 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro, S.; Leoni, L.; Cantini, A.; De Carlo, F. Trends and Recommendations for Enhancing Maturity Models in Supply Chain Management and Logistics. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 9724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyeme, C.; Liyanage, K. A Critical Review of Smart Manufacturing & Industry 4.0 Maturity Models: Applicability in the O&G Upstream Industry. Adv. Transdiscipl. Eng. 2021, 15, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein-Pensel, F.; Winkler, H.; Brueckner, A.; Woelke, M.; Jabs, I.; Mayan, I.J.; Kirschenbaum, A.; Friedrich, J.; Zinke-Wehlmann, C. Maturity assessment for Industry 5.0: A review of existing maturity models. J. Manuf. Syst. 2023, 66, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Neto, J.B.S.d.; Costa, A.P.C.S. Enterprise maturity models: A systematic literature review. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2019, 13, 719–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felippes, B.; da Silva, I.; Barbalho, S.; Adam, T.; Heine, I.; Schmitt, R. 3D-CUBE readiness model for industry 4.0: Technological, organizational, and process maturity enablers. Prod. Manuf. Res. 2022, 10, 875–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schabany, D.; Hülsmann, T.H.; Schmetz, A. Development of a Maturity Assessment Model for Digital Twins in Battery Cell Industry. Procedia CIRP 2023, 120, 946–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Industry 5.0. 2021. Available online: https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/research-area/industrial-research-and-innovation/industry-50_en (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Angreani, L.S.; Vijaya, A.; Wicaksono, H. Enhancing strategy for Industry 4.0 implementation through maturity models and standard reference architectures alignment. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2024, 35, 848–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlenkamp, J.F.; Hauge, J.B.; Broda, E.; Lutjen, M.; Freitag, M.; Thoben, K.D. Digital Twins: A Maturity Model for Their Classification and Evaluation. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 69605–69635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trstenjak, M.; Greguric, P.; Janic, Z.; Salaj, D. Integrated Multilevel Production Planning Solution According to Industry 5.0 Principles. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herceg, I.V.; Kuc, V.; Mijuskovic, V.M.; Herceg, T. Challenges and Driving Forces for Industry 4.0 Implementation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieroth, A.; Brunner, M.; Bachmann, N.; Jodlbauer, H.; Kurz, W. Investigation on the acceptance of an Industry 4.0 maturity model and improvement possibilities. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 200, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobakhloo, M.; Mahdiraji, H.A.; Iranmanesh, M.; Jafari-Sadeghi, V. From Industry 4.0 Digital Manufacturing to Industry 5.0 Digital Society: A Roadmap Toward Human-Centric, Sustainable, and Resilient Production. Inf. Syst. Front. 2024, 26, 10796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovari, A. Industry 5.0: Generalized Definition, Key Applications, Opportunities and Threats. Acta Polytech. Hung 2024, 21, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latino, M.E. A maturity model for assessing the implementation of Industry 5.0 in manufacturing SMEs: Learning from theory and practice. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2025, 214, 124045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.H.; Langås, E.F.; Sanfilippo, F. Exploring the synergies between collaborative robotics, digital twins, augmentation, and industry 5.0 for smart manufacturing: A state-of-the-art review. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2024, 89, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhard, O.; Zaeh, M.F. A Concept For The Development Of A Maturity Model For The Holistic Assessment Of Lean, Digital, And Sustainable Production Systems. In Proceedings of the Conference on Production Systems and Logistics; Herberger, D., Hubner, M., Eds.; Publish-Ing in Cooperation with TIB—Leibniz Information Centre for Science and Technology University Library: Hannover, Germany, 8–10 March 2023; pp. 837–847. Available online: https://repo.uni-hannover.de/handle/123456789/15400 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Demir, S.; Gunduz, M.A.; Kayikci, Y.; Paksoy, T. Readiness and Maturity of Smart and Sustainable Supply Chains: A Model Proposal. EMJ—Eng. Manag. J. 2023, 35, 181–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamboa-Rosales, N.K.; López-Robles, J.R. Evolving from Industry 4.0 to Industry 5.0: Evaluating the conceptual structure and prospects of an emerging field. Transinformação 2023, 35, e237319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünlü, H.; Demirörs, O.; Garousi, V. Readiness and maturity models for Industry 4.0: A systematic literature review. J. Softw.-Evol. Process 2024, 36, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morillo Trujillo, I. Industria 4.0 y Sociedad 5.0: Análisis de las Estrategias de China, Japón y la Unión Europea. Master’s Thesis, Universidad de Valladolid, Valladolid, España, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Abner, B.; Rabelo, R.J.; Zambiasi, S.P.; Romero, D. Production Management as-a-Service: A Softbot Approach. In Proceedings of the IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology (APMS 2020), Novi Sad, Serbia, 21–23 September 2020; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcácer, V.; Rodrigues, J.; Carvalho, H.; Cruz-Machado, V. Industry 4.0 maturity follow-up inside an internal value chain: A case study. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 119, 5035–5046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, A.; Peças, P. A Framework for Assessing Manufacturing SMEs Industry 4.0 Maturity. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajic, B.; Moraca, S.; Rikalovic, A. Fuzzy maturity model for Smart Manufacturing Readiness: Industry 5.0 perspective. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Zooming Innovation in Consumer Technologies Conference, ZINC, Novi Sad, Serbia, 29–31 May 2023; pp. 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbalho, S.C.M.; Dantas, R.F. The effect of islands of improvement on the maturity models for industry 4.0: The implementation of an inventory management system in a beverage factory 1,2. Braz. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2021, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmimoun, R.; El Kihel, Y.; Embarki, S.; El Kihel, B. Towards a Warehouse 4.0: Proposal of a Maturity Model for SMEs. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Innovative Research in Applied Science, Engineering and Technology, IRASET, Fez, Morocco, 16–17 May 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohorquez, J.H.A.; Gil-Herrera, R.D. Proposal and Validation of an Industry 4.0 Maturity Model for SMEs. J. Ind. Eng. Manag.-Jiem 2022, 15, 433–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretz, L.; Klinkner, F.; Kandler, M.; Shun, Y.; Lanza, G. The ECO Maturity Model—A human-centered Industry 4.0 maturity model. Procedia CIRP 2022, 106, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiado, R.G.G.; Scavarda, L.F.; Gavião, L.O.; Ivson, P.; Nascimento, D.L.D.M.; Garza-Reyes, J.A. A fuzzy rule-based industry 4.0 maturity model for operations and supply chain management. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 231, 107883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelo-Branco, I.; Oliveira, T.; Simoes-Coelho, P.; Portugal, J.; Filipe, I. Measuring the fourth industrial revolution through the Industry 4.0 lens: The relevance of resources, capabilities and the value chain. Comput. Ind. 2022, 138, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaopaisarn, P.; Woschank, M. Maturity Model Assessment of SMART Logistics for SMEs. Chiang Mai Univ. J. Nat. Sci. 2021, 20, e2021025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves Franz, M.L.; Ayala, N.F.; Larranaga, A.M. Industry 4.0 for passenger railway companies: A maturity model proposal for technology management. J. Rail Transp. Plan. Manag. 2024, 32, 100480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çinar, Z.M.; Zeeshan, Q.; Korhan, O. A Framework for Industry 4.0 Readiness and Maturity of Smart Manufacturing Enterprises: A Case Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciravegna-Martins-da fonseca, L.M.; Pereira, T.; Oliveira, M.; Ferreira, F.; Busu, M. Manufacturing Companies Industry 4.0 Maturity Perception Level: A Multivariate Analysis. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2024, 17, 196–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Perera, S.; Senaratne, S.; Osei-Kyei, R. Industry 4.0 Maturity of General Contractors: An In-Depth Case Study Analysis. Buildings 2024, 14, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elibal, K.; Özceylan, E. An Industry 4.0 Maturity Model Proposal Based on Total Quality Management Principles: An Application to an Automotive Parts Manufacturer. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 10815–10832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericson Öberg, A.; Goncalves Machado, C.; Stålberg, L. Diagnostics of Opportunities—A Dialogue Tool for Addressing Digital Factory Maturity. Adv. Transdiscipl. Eng. 2024, 52, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchini, F.; Olesków-Szlapka, J.; Ranieri, L.; Urbinati, A. A Maturity Model for Logistics 4.0: An Empirical Analysis and a Roadmap for Future Research. Sustainability 2020, 12, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D.V.; de Gusmão, A.P.H.; de Almeida, J.A. A multicriteria model for assessing maturity in industry 4.0 context. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2024, 38, 100579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökalp, M.O.; Gökalp, E.; Kayabay, K.; Koçyiğit, A.; Eren, P.E. Data-driven manufacturing: An assessment model for data science maturity. J. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 60, 527–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.D.O.; Basilio, J.C. A Fuzzy Inference Model to Identify the Current Industry Maturity Stage in the Transformation Process to Industry 4.0. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2024, 21, 1607–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz, D.; Benz, C.; Silbernagel, R.; Molins, B.; Satzger, G.; Lanza, G. A Maturity Model for Smart Product-Service Systems. Procedia CIRP 2022, 107, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamouli, Y.; Tetouani, S.; Cherkaoui, O.; Soulhi, A. To diagnose industry 4.0 by maturity model: The case of moroccan clothing industry. Data Metadata 2023, 2, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kırmızı, M.; Kocaoglu, B. Digital transformation maturity model development framework based on design science: Case studies in manufacturing industry. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2022, 33, 1319–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koldewey, C.; Hobscheidt, D.; Pierenkemper, C.; Kühn, A.; Dumitrescu, R. Increasing Firm Performance through Industry 4.0—A Method to Define and Reach Meaningful Goals. Science 2022, 4, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.C.; Sheng, M.L.; Jeng Wang, K. Dynamic capabilities for smart manufacturing transformation by manufacturing enterprises. Asian J. Technol. Innov. 2020, 28, 403–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.C.; Wang, K.J.; Sheng, M.L. To assess smart manufacturing readiness by maturity model: A case study on Taiwan enterprises. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2020, 33, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Lu, J.; Zhou, S. A review of digital twin capabilities, technologies, and applications based on the maturity model. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2024, 62, 102592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lookman, K.; Pujawan, N.; Nadlifatin, R. Measuring innovative capability maturity model of trucking companies in Indonesia. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2022, 9, 2094854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukhmanov, Y.; Dikhanbayeva, D.; Yertayev, B.; Shehab, E.; Turkyilmaz, A. An advisory system to support Industry 4.0 readiness improvement. Procedia CIRP 2022, 107, 1361–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhavan, M.; Sharafuddin, M.A.; Wangtueai, S. Measuring the Industry 5.0-Readiness Level of SMEs Using Industry 1.0–5.0 Practices: The Case of the Seafood Processing Industry. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdalena, L.; Isnanto, R.R.; Wibowo, A.; Warsito, B. Decision Making to Assess the Maturity Dimensions of MSME Using a Data Analysis Approach. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Informatics and Computational Sciences, Semarang, Indonesia, 24–25 November 2021; pp. 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnus, C.S. Smart factory mapping and design: Methodological approaches. Prod. Eng. 2023, 17, 753–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, H.T.; Schmiedbauer, O.; Biedermann, H. Validation of a Lean Smart Maintenance Maturity Model. Teh. Glas.-Tech. J. 2020, 14, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisiri, W.; van Dyk, L.; Coetzee, R. Development of an Industry 4.0 Competency Maturity Model. Saiee Afr. Res. J. 2021, 112, 189–197. [Google Scholar]

- Melnik, S.; Magnotti, M.; Butts, C.; Putman, C.; Aqlan, F. Developing a maturity model and an implementation plan for industry 4.0 integration. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Harare, Zimbabwe, 7–10 December 2020; Volume 59, pp. 1695–1707. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, F.; Monetti, F.M.; Torayev, A.; Rehman, H.U.; Mulet Alberola, J.A.; Rea Minango, N.; Nguyen, H.N.; Maffei, A.; Chaplin, J.C. A maturity model for the autonomy of manufacturing systems. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 126, 405–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nausch, M.; Schumacher, A.; Sihn, W. Assessment of Organizational Capability for Data Utilization – A Readiness Model in the Context of Industry 4.0. In Proceedings of the Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering; Durakbasa, N.M., Osman Zahid, M.N., Abd. Aziz, R., Yusoff, A.R., Mat Yahya, N., Abdul Aziz, F., Yazid Abu, M., Gençyilmaz, M.G., Eds.; Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH: Auckland, New Zealand, 25–27 November 2019; pp. 243–252. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-31343-2_21 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Nick, G.; Ko, A.; Szaller, Á.; Zeleny, K.; Kádár, B.; Kovács, T. Extension of the CCMS 2.0 maturity model towards Artificial Intelligence. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2022, 55, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nick, G.; Kovács, T.; Ko, A.; Kádár, B. Industry 4.0 readiness in manufacturing: Company Compass 2.0, a renewed framework and solution for Industry 4.0 maturity assessment. Procedia Manuf. 2021, 54, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nick, G.; Szaller, Á.; Várgedo, T. CCMS Model: A novel approach to digitalization level assessment for manufacturing companies. In Proceedings of the 16th European Conference on Management Leadership and Governance, ECMLG, Oxford, UK, 26–27 October 2020; Griffiths, P., Ed.; Academic Conferences International Limited: Reading, UK, 2020; pp. 195–203. Available online: https://books.google.ro/books?id=c4MIEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA195 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Nick, G.; Zeleny, K.; Kovács, T.; Járvás, T.; Pocsarovszky, K.; Ko, A. Artificial intelligence enriched industry 4.0 readiness in manufacturing: The extended CCMS2.0e maturity model. Prod. Manuf. Res.-Open Access J. 2024, 12, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senna, P.P.; Barros, A.C.; Bonnin Roca, J.; Azevedo, A. Development of a digital maturity model for Industry 4.0 based on the technology-organization-environment framework. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 185, 109645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan Nogueras, M.L.; Perea Muñoz, L.; Cosentino, J.P.; Suarez Anzorena, D. RAISE 4.0: A Readiness Assessment Instrument Aimed at Raising SMEs to Industry 4.0 Starting Levels—an Empirical Field Study. In Proceedings of the Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering, Aalborg, Denmark, 1–2 November 2021; Andersen, A.L., Andersen, R., Brunoe, T.D., Larsen, M.S.S., Nielsen, K., Napoleone, A., Kjeldgaard, S., Eds.; Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pech, M.; Vrchota, J. Classification of small-and medium-sized enterprises based on the level of industry 4.0 implementation. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peukert, S.; Treber, S.; Balz, S.; Haefner, B.; Lanza, G. Process model for the successful implementation and demonstration of SME-based industry 4.0 showcases in global production networks. Prod. Eng. 2020, 14, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafael, L.D.; Jaione, G.E.; Cristina, L.; Ibon, S.L. An Industry 4.0 maturity model for machine tool companies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 159, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahamaddulla, S.R.B.; Leman, Z.; Baharudin, B.T.H.T.B.; Ahmad, S.A. Conceptualizing smart manufacturing readiness-maturity model for small and medium enterprise (Sme) in malaysia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, S.M.; Bahadori, R.; Jafarnejad, H. The smart SME technology readiness assessment methodology in the context of industry 4.0. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2021, 32, 1037–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajadieh, S.M.M.; Noh, S.D. Towards Sustainable Manufacturing: A Maturity Assessment for Urban Smart Factory. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf.-Green Technol. 2024, 11, 909–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjad, A.; Ahmad, W.; Hussain, S.; Chuddher, B.A.; Sajid, M.; Jahanjaib, M.; Ali, M.K.; Jawad, M. Assessment by Lean Modified Manufacturing Maturity Model for Industry 4.0: A Case Study of Pakistan’s Manufacturing Sector. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 6420–6434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.C.; Martinho, J.L. An Industry 4.0 maturity model proposal. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2020, 31, 1023–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroderus, J.; Lasrado, L.A.; Menon, K.; Kärkkäinen, H. Towards a Pay-Per-X Maturity Model for Equipment Manufacturing Companies. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 196, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semeraro, C.; Alyousuf, N.; Kedir, N.I.; Lail, E.A. A maturity model for evaluating the impact of Industry 4.0 technologies and principles in SMEs. Manuf. Lett. 2023, 37, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simetinger, F.; Basl, J. A pilot study: An assessment of manufacturing SMEs using a new Industry 4.0 Maturity Model for Manufacturing Small- and Middle-sized Enterprises (I4MMSME). Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 200, 1068–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinlechner, M.; Schumacher, A.; Fuchs, B.; Reichsthaler, L.; Schlund, S. A maturity model to assess digital employee competencies in industrial enterprises. Procedia CIRP 2021, 104, 1185–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleiman, Z.; Dikhanbayeva, D.; Shaikholla, S.; Turkyilmaz, A. Readiness Assessment of SMEs in Transitional Economies: Introduction of Industry 4.0. In Proceedings of the ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, Association for Computing Machinery, Barcelona, Spain, 8–11 January 2021; pp. 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño-Elizondo, B.L.; García-Reyes, H. The challenge of becoming a worker 4.0—A human-centered maturity model for industry 4.0 adoption. In Proceedings of the IISE Annual Conference and Expo 2021, Montréal, QC, Canada, 22–25 May 2021; Ghate, A., Krishnaiyer, K., Paynabar, K., Eds.; Institute of Industrial and Systems Engineers (IISE): Peachtree Corners, GA, USA, 2021; pp. 584–589. [Google Scholar]

- Treviño-Elizondo, B.L.; García-Reyes, H. An Employee Competency Development Maturity Model for Industry 4.0 Adoption. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño-Elizondo, B.L.; García-Reyes, H.; Peimbert-García, R.E. A Maturity Model to Become a Smart Organization Based on Lean and Industry 4.0 Synergy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, C.; Sungur, C.; Yildirim, H. Application of the Maturity Model in Industrial Corporations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagire, A.A.; Joshi, R.; Rathore, A.P.S.; Jain, R. Development of maturity model for assessing the implementation of Industry 4.0: Learning from theory and practice. Prod. Plan. Control 2021, 32, 603–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widmer, N.; Hassan, A.; Monticolo, D. Assessment Model to Support the Technological Integration within Industrial Companies in the Context of Industry 4.0. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 28th International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Innovation, ICE/ITMC 2022 and 31st International Association for Management of Technology, IAMOT 2022 Joint Conference, Nancy, France, 19–23 June 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoubek, M.; Simon, M. A framework for a logistics 4.0 maturity model with a specification for internal logistics. MM Sci. J. 2021, 2021, 4264–4274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoubek, M.; Poor, P.; Broum, T.; Basl, J.; Simon, M. Industry 4.0 Maturity Model Assessing Environmental Attributes of Manufacturing Company. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetmanczyk, M.P. A Method for Evaluating the Maturity Level of Production Process Automation in the Context of Digital Transformation-Polish Case Study. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trstenjak, M.; Opetuk, T.; Dukic, G.; Cajner, H. Logistics 5.0 Implementation Model Based on Decision Support Systems. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code | Research Question |

|---|---|

| RQ.1 | How have Industry 4.0 and 5.0 maturity models evolved between 2020 and 2024? |

| RQ.2 | Are there significant differences in the evaluated dimensions between Industry 4.0 and 5.0 maturity models? |

| RQ.3 | Is there a significant relationship between the number of levels in Industry 4.0 and 5.0 maturity models and the dimensions evaluated in these models? |

| RQ.4 | What are the most frequently incorporated enabling technologies in Industry 4.0 and 5.0 maturity models? |

| Web of Science | Scopus |

|---|---|

| Engineering Industrial | Engineering |

| Engineering Manufacturing | Computer Science |

| Management | Environmental Science |

| Engineering Electrical Electronic | Energy |

| Computer Science Information Systems | Economics, Econometrics and Finance |

| Computer Science Interdisciplinary Applications | Multidisciplinary |

| Operations Research Management Science | |

| Green Sustainable Science Technology | |

| Computer Science Theory Methods | |

| Environmental Sciences | |

| Computer Science Artificial Intelligence | |

| Business | |

| Telecommunications | |

| Engineering Multidisciplinary | |

| Environmental Studies | |

| Automation Control Systems | |

| Computer Science Software Engineering | |

| Robotics | |

| Economics | |

| Ergonomics | |

| Industrial Relations Labor |

| RQ | Variable | Procedure (Methods) | Evidence/Artifact | Linked Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RQ.1 Evolution of scope (I4.0/Hybrid/I5.0) | V1; V2; V3 |

| Figure 4 Figure 5 Table 4 Table 5 Figure 6 | Temporal transition pattern from I4.0 to I5.0 and category distribution |

| RQ.2 Dimension coverage | V2; V3 |

| Table 6 | Coverage breadth and dimensional profiles |

| RQ.3 Level structure | V2; V3; V4 |

| Table 7 Table 8 | Distribution of discrete/ continuous levels and comparisons by scope |

| RQ.4 Referenced technologies | V2; V5 |

| Figure 7 | Technological profiles by scope category |

| Dimension | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Quality | 4 | 5% |

| Customers and Market | 7 | 9% |

| Management and Strategy | 38 | 51% |

| Infrastructure and Ecosystem | 16 | 21% |

| Innovation and Value Creation | 27 | 36% |

| Human–Machine Interaction | 4 | 5% |

| People and Competencies | 34 | 45% |

| Processes and Operations | 38 | 51% |

| Security and Governance | 9 | 12% |

| Sustainability and Social Responsibility | 10 | 13% |

| Technology and Digitalization | 53 | 71% |

| Number of Dimensions | Frequency | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 2 | 2.67% |

| 3 | 17 | 22.67% |

| 4 | 20 | 26.67% |

| 5 | 16 | 21.33% |

| 6 | 12 | 16.00% |

| 7 | 5 | 6.67% |

| 8 | 2 | 2.67% |

| 12 | 1 | 1.33% |

| Dimensions | Industry 4.0 | Industry 4.0 & 5.0 | Industry 5.0 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality | 4 | - | - | 4 |

| Customers and Market | 7 | - | - | 7 |

| Management and Strategy | 38 | - | - | 38 |

| Infrastructure and Ecosystem | 15 | - | 1 | 16 |

| Innovation and Value Creation | 26 | - | 1 | 27 |

| Human–Machine Interaction | 4 | - | - | 4 |

| People and Competencies | 33 | - | 1 | 34 |

| Processes and Operations | 35 | 1 | 2 | 38 |

| Security and Governance | 9 | - | - | 9 |

| Sustainability and Social Responsibility | 8 | 2 | - | 10 |

| Technology and Digitalization | 50 | 1 | 2 | 53 |

| Maturity Levels | Frequency | % of 75 Models |

|---|---|---|

| 3 levels | 6 | 8.00% |

| 4 levels | 8 | 10.67% |

| 5 levels | 37 | 49.33% |

| 6 levels | 14 | 18.67% |

| 10 levels | 1 | 1.33% |

| 11 levels | 1 | 1.33% |

| 100 levels (percentage scale) | 1 | 1.33% |

| No fixed levels/alternate method | 7 | 9.33% |

| Dimensions/Levels | 0 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 10 | 11 | 100 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality | 1 | 1 | - | 2 | - | - | - | 4 | 8 |

| Customers and Market | - | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | - | - | - | 7 |

| Management and Strategy | - | - | - | 20 | 11 | - | - | - | 33 |

| Infrastructure and Ecosystem | 1 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 3 | - | 1 | - | 16 |

| Innovation and Value Creation | - | 3 | 1 | 13 | 8 | - | - | - | 27 |

| Human–Machine Interaction | - | - | 1 | 2 | 1 | - | - | - | 4 |

| People and Competencies | - | 3 | 2 | 20 | 6 | - | 1 | - | 32 |

| Processes and Operations | - | 2 | 5 | 20 | 9 | - | - | - | 38 |

| Security and Governance | - | - | - | 5 | 4 | - | - | - | 9 |

| Sustainability and Social Responsibility | - | - | - | 8 | 2 | - | - | - | 10 |

| Technology and Digitalization | - | - | 3 | 22 | 12 | 1 | - | - | 38 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Reyes Domínguez, D.; Infante Abreu, M.B.; Parv, A.L. Evolution and Key Differences in Maturity Models for Industrial Digital Transformation: Focus on Industry 4.0 and 5.0. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11042. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411042

Reyes Domínguez D, Infante Abreu MB, Parv AL. Evolution and Key Differences in Maturity Models for Industrial Digital Transformation: Focus on Industry 4.0 and 5.0. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11042. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411042

Chicago/Turabian StyleReyes Domínguez, Dayron, Marta Beatriz Infante Abreu, and Aurica Luminita Parv. 2025. "Evolution and Key Differences in Maturity Models for Industrial Digital Transformation: Focus on Industry 4.0 and 5.0" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11042. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411042

APA StyleReyes Domínguez, D., Infante Abreu, M. B., & Parv, A. L. (2025). Evolution and Key Differences in Maturity Models for Industrial Digital Transformation: Focus on Industry 4.0 and 5.0. Sustainability, 17(24), 11042. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411042