Abstract

Purpose: This paper takes an original approach to the topic of social entrepreneurship. The purpose of this study is to identify and analyze social entrepreneurship capital resources in rural areas based on farms located in rural areas of the Silesian Voivodeship (region in Poland). The research presented in this paper covers the characteristics of local change leaders in the context of building a sustainable foundation for the development of pro-social and economic activities. Methodology: The first stage of this project, a literature review, involved identifying the social entrepreneurship environment in rural areas. The second stage of this research involved an analysis of the initiative potential of change leaders. The empirical research used a survey method, in-depth interviews, and participant observation. Findings and implications: The most important findings of this research concern the possibilities for the development of social entrepreneurship in rural areas with the participation of local change leaders (agents). This article analyzes the characteristics of the initiative potential of change leaders in the context of their role as animators of social life and creators of sustainable mechanisms for implementing innovative social practices. The conclusions formulated in this article are of an applied nature. This paper highlights the need to create a system of real support through the effective activation of organizations operating in rural areas, strengthening the role of change leaders as animators of local life, local partnerships and equal opportunities.

1. Introduction

Contemporary research on entrepreneurship includes analyses of the activities of individuals and organizations, with a clear focus on achieving social and economic goals [1,2]. Alongside the activities of for-profit enterprises and non-profit NGOs, the phenomenon of social entrepreneurship has been developing dynamically [3,4,5]. Social entrepreneurship combines economic (commercial) and social dimensions and is rooted in the pursuit of a social mission and the creation of value. The creation of value for society, together with competitive market value, is considered fundamental [6]. The essence of social entrepreneurship lies in the achievement of social objectives while generating profits that ensure the sustainability of activities [7]. Economic efficiency, in turn, determines the scale and scope of initiatives undertaken for the benefit of local communities.

Social entrepreneurship addresses the needs of, and responds to the problems faced by, individuals and groups at risk of social and professional exclusion. It identifies real challenges within local communities and seeks innovative, sustainable, and balanced solutions to them [8]. It pursues non-standard approaches, creating social value despite often limited resources [9]. It aligns with the principles of sustainable development, integrating social, economic, and environmental dimensions [10,11].

Social entrepreneurship significantly contributes to social, economic, cultural, and environmental development and is becoming an increasingly important element of local, regional, national, and global development policy. This is also the case in the context of rural development. The literature highlights a notable lack of research on social entrepreneurship in rural areas [12,13]. Given this research gap, undertaking in-depth studies appears to be well justified. Examining the capital resources that support social entrepreneurship in rural areas emerges as a promising area for empirical investigation. It is assumed that individuals with a high level of initiative may act as local leaders of change, helping to create a sustainable basis for the development of social entrepreneurship.

2. Social Entrepreneurship in Rural Areas—Literature Review

The contemporary approach to rural development increasingly emphasizes the significance of social capital and social entrepreneurship as foundations for structural and evolutionary change. Particular attention is paid to the complex links between social networks, the institutional environment, and the ability of local leaders to initiate action. Moyes, Ferri, Henderson, and Whittam [14] examined the role of network structures in shaping capital in their research on entrepreneurship in rural areas. They proposed a distinction between two fundamental types of capital: “core social capital” and “augmented social capital.”

Core social capital refers to intra-group ties rooted in close family, neighborhood, and community relationships, which strengthen activities within local groups. Augmented social capital, by contrast, encompasses intergroup ties that transcend the boundaries of traditional communities and facilitate connections with external actors [14]. It is generally assumed that augmented social capital plays a key role in creating more expansive and dynamic entrepreneurial structures, as intergroup ties increase access to diverse resources and enable the integration of local initiatives into broader systems of influence. In this sense, augmented social capital provides a basis for the development of more open and sustainable forms of social entrepreneurship that extend beyond the traditional local sphere.

Research on social innovation in rural communities remains in its infancy, revealing a significant gap in the literature. One emerging direction of empirical inquiry concerns the relationship between social entrepreneurship and the development of various forms of capital arising within social networks that generate social innovation [15]. Studies conducted in rural communities in Colombia indicate that the development of social entrepreneurship acts as a catalyst for “interactive and collective learning.” Consequently, social entrepreneurship not only supports the emergence of local innovation but may also lead to institutional change, which in turn contributes to long-term structural transformation. Operating within the framework of social networks, social entrepreneurship becomes a mechanism for the effective use of local knowledge.

Steiner, Farmer, and Bosworth [13] highlight the strong compatibility between social entrepreneurship and the characteristics of traditional rural life. They regard social entrepreneurship as a “natural” development model for such communities. As the authors note, “social enterprise is suggested as aligned with features of traditional rural life. The collective working associated with rurality is significant to community-initiated and run social enterprises” [13]. This suggests that collective cooperation rooted in rural culture—based on mutual assistance, solidarity, and collaborative action—creates a favorable environment for social initiatives. An analysis of the impact of social capital on entrepreneurial behavior in rural Pakistan confirms that social capital significantly shapes proactive attitudes [16]. In this context, the cooperative dimension of social capital is particularly important, as entrepreneurial activity contributes to reducing economic disparities and promoting more inclusive forms of growth.

Another important area of research concerns the role of social capital in fostering entrepreneurship in agricultural communities, with particular emphasis on the specific nature of social and institutional relations. Two interrelated factors are especially important in shaping conditions conducive to entrepreneurial activity: the quality of the institutional environment and the level of trust [17]. Scholars emphasize that trust—both within communities and in relations between residents and public institutions—constitutes a key resource that enables the effective functioning of cooperation networks, knowledge exchange, and the initiation of activities. The development of such networks promotes community involvement and supports the functioning of civil society [18,19]. In mobilizing rural resources, particular weight is placed on the synergy between formal structures and informal relationships.

Valuable insights also emerge from studies examining the relationship between social capital and entrepreneurial behavior. Research conducted by Roxas and Azmat [20] in rural communities in the Philippines confirms a link between trust, the intensity of social interaction, and the willingness to undertake entrepreneurial initiatives. In this context, embedded relational capital acts as a catalyst for entrepreneurial activity. Similar findings emerge from studies by Trigkas, Partalidou, and Lazaridou [21] on mountainous rural communities in Greece, which show that both interpersonal and institutional trust promote cooperation and engagement. A stable and supportive institutional environment not only encourages the initiation of new ventures but also contributes to their long-term sustainability [22].

Empirical studies across diverse geographical contexts lead to the conclusion that social entrepreneurship in rural areas operates at the intersection of multiple levels of social and institutional networks. Individuals and groups in rural settings often act as leaders of change, initiating mechanisms for the implementation of innovative social practices [23]. The ability to drive change in peripheral areas requires adaptability and leadership skills, particularly in contexts characterized by dominant traditional structures and limited access to resources. An important perspective highlights the dual role of local leaders and geographical proximity.

Research by Lan, Zhu, Ness, Xing, and Schneider [24] examined the role of local leaders as key actors shaping the entrepreneurial spirit in rural communities in China. Drawing on qualitative interviews conducted in Yunnan and Zhejiang provinces, the authors analyzed leadership, entrepreneurial activity, and the development of rural cooperatives. Their findings indicate that strong, actively engaged leaders promote the mobilization of local resources, stimulate resident participation, and strengthen communities’ capacity for self-organization. In transitional economies, social entrepreneurship acts as a compensatory mechanism that supports the development of structures rooted in local contexts.

Another analytical perspective emphasizes the significance of geographical proximity in promoting the development of social entrepreneurship in rural areas [25]. Spatial closeness facilitates trust-building and intensifies social interactions. Territorial conditions also enhance the capacity of communities to solve problems collectively and undertake joint initiatives. Interestingly, the study by Friedrichs and Wahlberg [25] assigns particular importance to volunteer work, identifying it as a significant driver of change. Volunteers functioning as local leaders and initiators of grassroots activities play a central role in activating residents and implementing initiatives.

The literature underscores that rural areas—despite infrastructural shortcomings—possess unique relational, cultural, and environmental resources that can effectively support entrepreneurial development, including forms characterized by elevated levels of risk. In this context, special attention is given to the role of entrepreneurs, who act as intermediaries integrating local resources and potential with external support structures [12]. The ability to navigate between different levels of social networks is considered crucial. Lang and Fink [12] observe that social entrepreneurship in rural areas is based on a proactive stance and a willingness to take risks. These activities are not adaptive in nature but rather reflect initiative and creativity. As such, social entrepreneurship strengthens the resilience of rural communities and acts as a catalyst for socio-economic change. Nonetheless, the conceptualization of the role of social entrepreneurs in rural areas remains underdeveloped [12].

Risk is inherent in social entrepreneurship. Research on the relationship between selected elements of social capital and the development of entrepreneurship includes the analysis of risk [26]. Studies conducted in rural South Africa indicate that the ability to identify and exploit new opportunities is a key factor determining the success of entrepreneurial initiatives [27]. However, in rural contexts—characterized by limited access to resources and often weak institutional support—the search for innovative solutions involves greater risk than in urban settings.

The literature highlights the growing importance of social entrepreneurship, most often in the context of meeting community needs, addressing local problems, and preventing exclusion [28]. Social entrepreneurship is increasingly regarded as an alternative model for conducting economic activity and providing services in rural areas. According to Steiner, Farmer, and Bosworth [13], this phenomenon remains insufficiently recognized in both academic research and public policy, which limits its potential in peripheral regions. In light of structural transformations affecting rural areas and the growing interest in innovative local development strategies, the authors call for the formulation of a dedicated research agenda on rural social enterprises [13].

Research to date on social entrepreneurship in rural areas clearly demonstrates the need for further inquiry, particularly concerning operational models and social outcomes. In the context of socio-economic change in rural areas, social entrepreneurship is emerging as an important subject of reflection within local development theory, empirical investigation, and public policy. Steiner, Farmer, and Bosworth [13] emphasize that knowledge of business models used by rural social enterprises remains fragmented and insufficient. They point to a lack of understanding of how rural social enterprises integrate with local economic and social systems. This gap highlights the necessity for in-depth analysis to better understand how social entrepreneurship contributes to local resilience, job creation, strengthening social capital, and reducing exclusion in rural areas.

3. Materials and Methods

The exploration of the phenomenon of social entrepreneurship in rural areas was conducted against the background of the characteristics of a local change leader. The following research assumption was adopted: people with high initiative potential, expressed through a set of features, can act as local change leaders for the development of social entrepreneurship.

The research problem concerned the strengthening of pro-social and economic activities with the participation of change leaders. The research question was formulated as follows: what features determine the initiative potential of leaders? The aim of the empirical study was to understand the structure of the potential of change leaders for the development of social entrepreneurship in rural areas.

The research project involved identifying and analyzing social entrepreneurship capital among selected groups and assessing their readiness to undertake pro-social and pro-social and economic activities. The project consisted of two stages. The first stage was theoretical research, which involved describing the specifics of social entrepreneurship in rural areas. The second stage involved an empirical analysis of the structure of the potential of change leaders.

The literature review was conducted using secondary data analysis. The empirical research used surveys, in-depth interviews, and participant observation. The empirical exploration was conducted among entities operating in rural areas. This research was conducted among owners of educational, agritourism, agricultural, and agricultural retail trade (RHD) farms. This research was carried out in close cooperation with the Silesian Agricultural Advisory Center in Częstochowa and the Association of Educational Farms of the Silesian Province.

A total of 25 respondents participated in the survey (Table 1). The majority of the actors were educational farms—12, including 5 with activities combined with agritourism, agriculture, and agricultural retail trade.

Table 1.

Structure of respondents participating in the survey.

Quantitative research was performed using an author-developed survey addressed to entities operating in rural areas of the Silesian Province. The survey questionnaire contained 16 questions concerning areas such as risk, openness, creativity, cooperation, sensitivity, and motivation. The questions in the questionnaire were grouped according to these areas. Each of them was precisely described from the perspective of social entrepreneurship. The selection of these areas for analysis is based on the author’s many years of research on the issue of social entrepreneurship, the role of change leaders, and the determinants of entrepreneurial potential [3,4,5]. In order to assess the reliability of the scales used, Cronbach’s α coefficients were calculated for the six dimensions analyzed (commitment, motivation, creativity, openness, cooperation, and resilience). The values obtained ranged from 0.71 to 0.84, which indicates satisfactory internal consistency of the measured constructs and allows the results to be treated as reliable in further descriptive analyses.

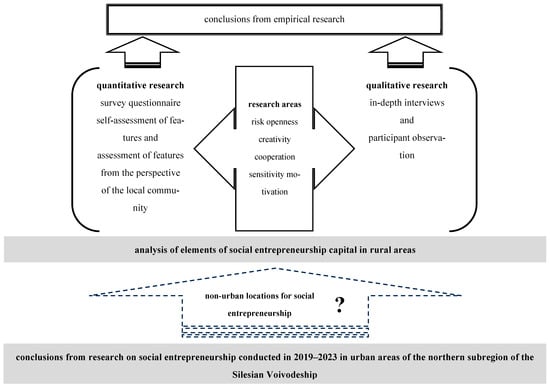

The methodological sequence of studies on social entrepreneurship in rural areas is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Methodological sequence of studies on social entrepreneurship in rural areas. Source: Own work.

In the proposed research approach, quantitative data analysis was carried out on two levels. The first, individual level consisted of self-assessment of characteristics by the study participants. In the second, respondents assessed characteristics from the perspective of the local community. This study used a five-point rating scale from lowest (1) to highest (5). It was agreed that values 1 and 2 reflect a low level of the feature, 3 reflects an average level, and 4 and 5 reflect a high level.

Qualitative research was conducted in parallel with quantitative research at the turn of April and May 2025. In-depth interviews were conducted with five owners of educational farms located in the northern part of the Silesian Voivodeship in three poviats: Częstochowa (3 entities), Myszków, and Kłobuck. The interview scenario was structured around six main thematic areas concerning risk, openness, creativity, cooperation, sensitivity, and motivation. The interviews were accompanied by participant observation consisting of field visits to individual farms. The qualitative coding process was carried out by a single researcher. To reduce the risk of bias, coding was performed in several stages: (1) multiple readings of the transcripts, (2) creation and comparison of codes at intervals, (3) consultation of preliminary categories with two colleagues not involved in the project. These measures were intended to improve the transparency and stability of the interpretation. This mixed research approach, based on triangulation, although carried out on a statistically small sample, is a clear and coherent concept. Of course, it does not exhaust the potential of the issue, but nevertheless, the idea of empirical research seems to be an interesting example of interpreting the social world and the processes that occur within it.

4. Results

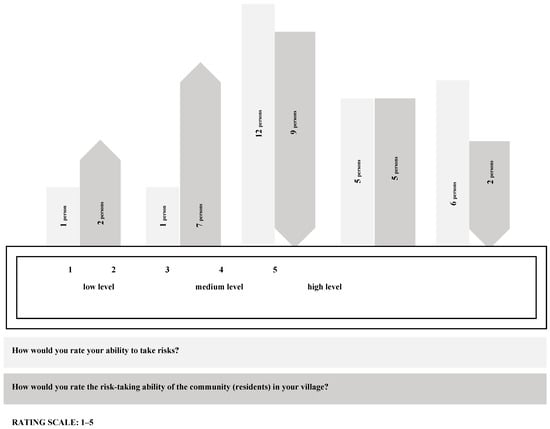

The research results presented in this section have been compiled in a descriptive form, enriched with diagrams illustrating scales and relationships, tables containing summary lists of factors and entities, and narrative interpretations. The results of the respondents’ self-assessment of their risk-taking ability reflect a distribution of responses that oscillates mainly around the medium and high levels. Nearly half of the study participants (12 people) declared a medium risk-taking ability. Another six people gave the highest rating. Only two of the respondents indicated a low level, giving a score of 1 or 2. A more diverse distribution of responses was obtained in the assessment of risk-taking ability in relation to the local community. In this case, a significantly smaller group of respondents (16 people) indicated a high or medium level. As many as 9 people rated the community’s risk-taking ability as low. The results of the self-assessment of risk-taking ability and the assessment from the perspective of the local community are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Assessment of risk-taking ability. Source: Own study based on empirical research.

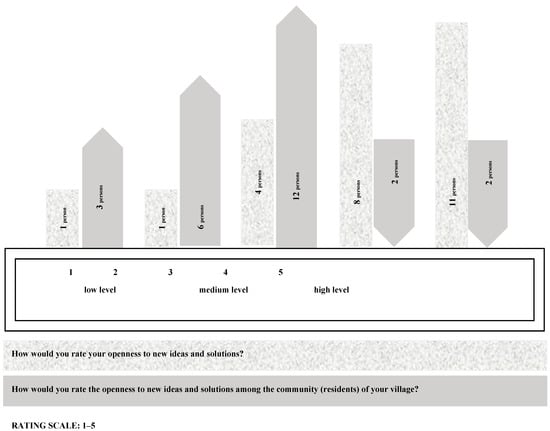

In the case of the trait: openness to new ideas and solutions, the majority of participants in this study were people who rated their openness highly (9 people). Only two respondents declared a low level of self-assessment of this trait. A different distribution of responses was obtained when assessing this trait from the perspective of the local community. In this case, the assessments mostly oscillated around the average and low levels. Such a declaration was made by 12 and 9 people, respectively. Only 2 respondents rated the openness of the local community highest. The results of the self-assessment of openness to new ideas and solutions, together with the assessment from the perspective of the local community, are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Assessment of openness to new ideas and solutions. Source: Own study based on empirical research.

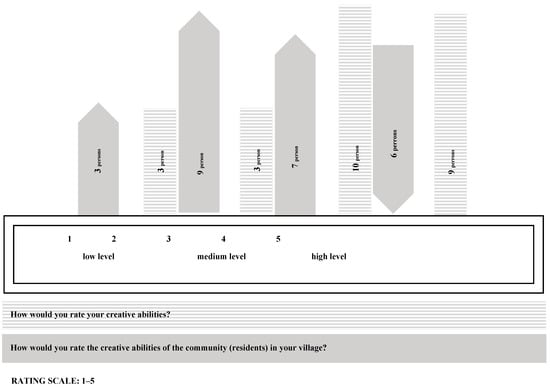

Responses regarding self-assessment of creative abilities indicate a high level of this trait among the vast majority of respondents (19 people). However, this does not translate into an assessment of abilities from the perspective of the local community. In this case, only six respondents gave a rating of 4. When assessing this trait, no one declared the lowest level. Meanwhile, twelve respondents believe that the creativity of the local community is low. None of the participants indicated the highest level. The results of the self-assessment of creative abilities and the assessment from the perspective of the local community are presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Assessment of creative abilities. Source: Own study based on empirical research.

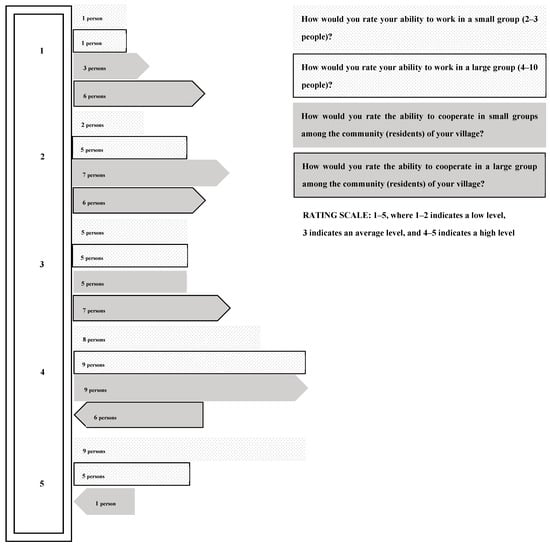

Seventeen respondents declared a high ability to cooperate in a small group of 2–3 people. The self-assessment results mostly indicate an average and high level. Nine, eight, and five respondents rated this trait in the range of 5 to 3 (5, 4, and 3, respectively). A slightly lower level of self-assessment was obtained when examining cooperation in larger teams of 4–10 people. In this case, 14 people rated this trait highly. A significantly different distribution of responses was obtained when assessing the residents’ ability to cooperate. Only ten respondents rated cooperation in small groups highly. According to the next ten, the ability to cooperate at the local community level is low. The same applies to cooperation in large teams. In this case, none of the respondents gave the highest rating. The results of self-assessment of the ability to cooperate and assessment from the perspective of the local community are presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Assessment of teamwork skills. Source: Own study based on empirical research.

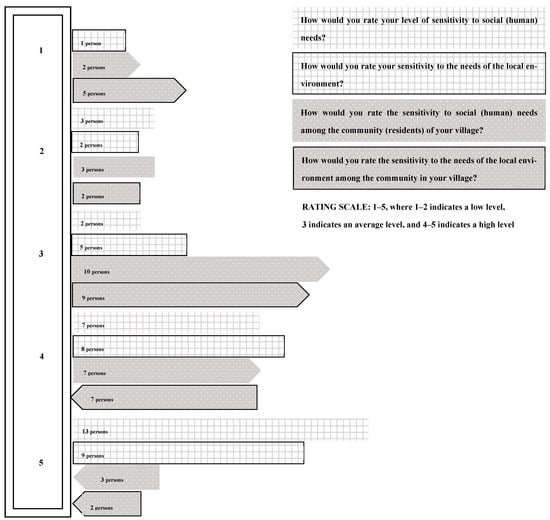

When analyzing self-assessment of sensitivity to social (human) needs, the vast majority of respondents (20 people) indicated a high level. More than half of the respondents rated this trait highest. Only three of the 25 participants in this study had a low level of sensitivity. Similar self-assessment results were obtained in the study of sensitivity to the needs of the local environment, including nature conservation, shared infrastructure, etc. The vast majority of respondents declared a high level of this trait. Only three people had a low level. A slightly lower level of sensitivity to social and local environmental needs was attributed to residents. However, according to the respondents, medium and high ratings still prevail. The results of the self-assessment of sensitivity to social and local environmental needs and the assessment from the perspective of the local community are presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Assessment of sensitivity to social needs and the local environment. Source: Own study based on empirical research.

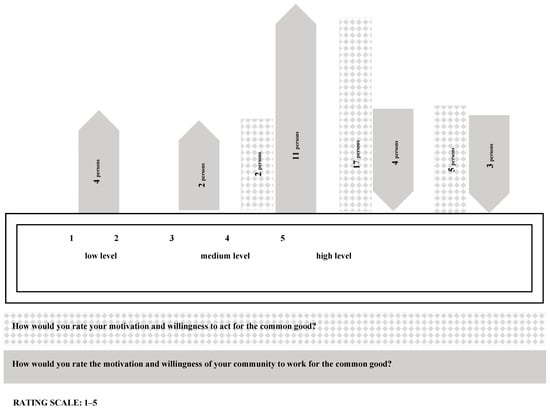

Among the respondents, a high level of self-assessment was achieved in the area of motivation and willingness to act for the common good, as confirmed by the responses of twenty-three people. The remaining two rated the trait at an average level. A different distribution of responses using the full rating scale (i.e., from 1 to 5) was obtained for the assessment of motivation and willingness to act for the common good from the perspective of the community of residents. In this case, only seven respondents rated this trait highly. The remaining eleven indicated an average level. The results of the self-assessment of motivation and willingness to act for the common good and the assessment from the perspective of the local community are presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Assessment of motivation and willingness to act for the common good. Source: Own study based on empirical research.

The table below presents descriptive summary of six dimensions of the survey: self-assessment vs. community assessment (Table 2).

Table 2.

Descriptive summary of six dimensions of the survey (self-assessment vs. community assessment).

Field research involving in-depth interviews with entrepreneurs operating in rural areas was conducted in three poviats: Częstochowa, Myszków, and Kłobuck.

The first interview (IDI1) was conducted at an educational farm located in the Kłobuck poviat. The farm organizes educational workshops for children, young people, and adults on topics related mainly to the cultivation and processing of cereals, bread making according to traditional recipes, and the place and role of forests in the ecosystem. The farm also offers agritourism services.

This was followed by a field visit to an educational farm located in the southern part of the Częstochowa district, during which a second interview (IDI2) was conducted. The main area of activity of the farm is workshops for children in kindergartens and schools, young people, and adults in the field of handicrafts and folk art, Slavic cultural traditions, the material cultural heritage of the countryside and traditional professions, as well as environmental education. The potential of the place allows for the provision of accommodation services, agritourism, the organization of training courses and special events.

Subsequently, an interview (IDI3) was conducted with the owner of a farm in the municipality of Mykanów in the Częstochowa poviat. The farm is involved in fruit growing, including the cultivation of fruit trees, production, and sale of fruit. It conducts educational workshops on the functioning of an orchard and its place in the ecosystem, processing of agricultural products, and herbalism.

During the next field visit, an interview (IDI4) was conducted with an entrepreneur who runs educational classes for children, young people, adults, including seniors and people with disabilities, and manufactures natural products. The educational farm is located in the Częstochowa poviat. It operates in the field of beekeeping, focusing on workshops and the production and sale of bee products. The workshops focus on the life and role of bees in the ecosystem, honey production, and the profession of beekeeping.

The last fifth interview (IDI5) was conducted at an educational farm in the Myszków poviat. The farm provides educational and catering services. Its main activities are educational workshops for preschool and school children and thematic classes for seniors.

In-depth interviews conducted with owners of educational farms focused on identifying key factors (features) influencing the development of social entrepreneurship potential in rural communities. Due to the involvement of educational farm owners in the development of this potential, it was decided that they could act as leaders of change in the local social environment. This group of entrepreneurs can therefore strengthen social entrepreneurship capital, as their activities, in addition to commercial goals, include many pro-social components. Generalized conclusions from the interviews, focused on six main thematic areas, are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Set of representative content from in-depth interviews.

The motivation to act was often described by respondents as stemming from a sense of responsibility for the farm: “I can’t wait for someone else to do something for me, here, you have to act immediately” (ID12). Respondents also pointed to the perceived difference between themselves and the local community: “I have ideas, but sometimes it’s hard to push them through because people are used to what they know’ (ID7). Based on the analysis of the interview content, the area of risk was clearly and unambiguously manifested. The prospect of potential failure did not deter further challenges. Perseverance, consistency, and the ability to cope with difficulties were reflected in the planning and implementation of preventive measures against likely crisis situations.

Openness was declared through the search for new opportunities and readiness for new solutions. However, it did not always involve genuine and natural acceptance of what was new. Openness to new ideas also gave way to what was known and proven. It also did not always manifest itself in everyday activities, as confirmed by field research.

High creativity characterized most entrepreneurial and social activities. At that time, a non-standard and innovative approach was applied in the process of creating new products, managing resources, and space. However, uncritical ingenuity in new applications of proven solutions also dominated in part.

The area of teamwork was expressed through a high ability to initiate and manage a community of ideas and values. The community approach prevailed in the vast majority of cases. Field research particularly emphasized the strength of the community and the role of social networks.

The entrepreneurs participating in the interviews were characterized by a high sensitivity to social needs and the local environment. A pro-social approach dominated their entrepreneurial activities. At the same time, care for the natural environment and nature conservation were also important areas of interest.

In terms of motivation, the statements of most respondents were clear and unambiguous. Strong roots in the local community and a sense of community encouraged them to engage in activities that served the community, especially those in need. The same was true for meeting infrastructure and environmental needs.

5. Discussion

Research on social entrepreneurship capital conducted through surveys, in-depth interviews, and participant observation indicates a set of potential elements identified by entrepreneurs operating educational, agritourism, agricultural, and agricultural retail enterprises. The representatives of the farms participating in this study may be considered an important group of change leaders. It should be emphasized that, compared to the general population of their respective localities, these individuals display higher levels of entrepreneurial capital, adaptability to changing conditions, and the ability to make effective use of local resources. Their activities have both economic and social dimensions, the latter expressed, among other ways, through the initiation of projects serving local communities. In most cases, these individuals play opinion-forming and integrative roles, building trust capital that enhances their capacity to mobilize social capital. Another important dimension is their potential for institutional cooperation with local governments, the education sector, and organizations supporting rural development, which frequently enables them to obtain the resources needed to implement local initiatives. The qualitative findings corroborate the patterns observed in the quantitative results. For instance, high levels of self-assessed motivation correspond with participants’ statements on their readiness to take on challenges and assume responsibility for farm development, suggesting that such attitudes are essential to the functioning of local agricultural enterprises.

The assessment of potential was based on an evaluation of key areas influencing the adoption of entrepreneurial attitudes in the social domain. The analysis of risk-taking, openness, creativity, collaboration, sensitivity, and motivation made it possible to construct a comprehensive profile of leaders in the context of developing social entrepreneurship potential. The most highly rated traits included willingness to act for the common good, sensitivity to social needs, openness to new ideas and solutions, and creativity, cited by 23, 20, 19, and 19 respondents, respectively. The emphasis placed on these traits appears promising, particularly for identifying the real needs of local communities, strengthening social cohesion, and developing non-standard solutions to problems of social exclusion. The search for and implementation of solutions directly addressing the actual needs and expectations of individuals and groups lies at the core of social entrepreneurship. Collaboration also emerged as an important dimension, with the majority of respondents (17 individuals) rating their ability to work effectively in small groups highly. Taken together, these findings suggest that the entrepreneurs surveyed demonstrate a high level of initiative potential.

A high level of initiative potential is closely aligned with heightened sensitivity to the needs of the local environment. Although activities within social entrepreneurship are primarily oriented toward addressing community needs and solving local problems, it is important to note that they also respond to environmental concerns and are often directed toward the development of inclusive and functional shared infrastructure. The survey results confirmed a high level of environmental sensitivity among most of the entrepreneurs (17 individuals), alongside high and moderate levels (11 and 12 individuals, respectively) of risk-taking capacity in the context of activities benefiting both the social and natural environments.

When comparing self-assessment results with evaluations of community characteristics, a noteworthy pattern emerges. Entrepreneurs consistently rated their own skills and competencies significantly higher than those they attributed to the broader community. This may reflect, on the one hand, a natural human tendency toward favorable self-evaluation, and on the other, a genuinely higher level of engagement in community-oriented initiatives, as well as an enhanced ability to identify new opportunities or holistically assess the surrounding environment. The largest discrepancies were observed in two of the six analyzed characteristics: openness to new ideas and solutions, and motivation to act for the common good. Respondents rated the creativity and collaborative capacity of the local community particularly low, as almost 50% of responses indicated. Given that entrepreneurship inherently involves collective action, this finding is especially important in the context of mobilizing local communities to engage in initiatives driven by change-oriented leaders.

Two additional characteristics—risk-taking capacity and openness to new ideas and solutions—also warrant attention. According to nine respondents, the local community displays a low level of both traits. Another noteworthy perspective concerns gender differences. While no significant discrepancies emerged in the self-assessment of risk-taking capacity (average of approximately 3.5), women rated this trait in the local community slightly higher than men. Women also assessed their own openness to new ideas and solutions, as well as their creativity, more favorably—by approximately 0.5 points—than male respondents. A similar pattern appeared in their evaluations of these traits at the community level. Moreover, compared with men, women demonstrated greater sensitivity to local needs, including environmental protection and the development of shared infrastructure.

Poon, Thai, and Naybor [29] conducted empirical research on the role of social capital in supporting women’s entrepreneurship in rural areas of northern Vietnam. Their analysis showed that a key factor in women’s entrepreneurial development is family-based social capital, understood as emotional, material, and organizational support derived from close social networks. Strong family ties function as a critical resource for overcoming social and economic barriers. Notably, the authors identified an unusual pattern: greater distance from public markets positively correlated with the likelihood of women engaging in entrepreneurial activity. This suggests that in contexts with limited access to formal market structures, women may be more inclined to establish alternative, locally rooted, and socially network-based forms of economic activity.

In-depth interviews and participant observation carried out in five educational farms further confirmed the strong involvement of both female and male entrepreneurs in activities aimed, on the one hand, at promoting rural cultural heritage through interactions with visitors from outside the community, and on the other, at addressing the internal needs of local residents. Interestingly, the findings reaffirm that women display higher levels of entrepreneurial behavior. Compared to men, they demonstrate greater readiness to engage in non-standard activities requiring openness and creativity.

The owners of the surveyed farms exhibit above-average engagement in the life of their local communities. They express clear willingness and readiness to collaborate in the pursuit of social initiatives. Importantly, they unanimously declared positive attitudes toward solving community-level problems and demonstrated openness to genuine cooperation. According to participants, the importance of neighborly ties, knowledge exchange, and the willingness to support and engage in local initiatives are key factors conducive to the development of social entrepreneurship. On this basis, it may be inferred that experience in cooperation with local communities, non-governmental organizations, and public institutions significantly shapes the initiative potential of change leaders. Due to the small sample size (N = 25) and the exploratory nature of this study, conducting statistical difference tests (e.g., paired-sample t-tests) would not be justified, as these tests require assumptions of normality and distribution stability, which cannot be met in such a small sample. For this reason, a descriptive approach was adopted, providing a more reliable representation of the characteristics of the analyzed group.

6. Conclusions

This paper addresses the issue of social entrepreneurship, a matter of critical importance in the context of responding to social challenges in rural areas. It highlights the role of local change leaders with high initiative potential in creating a sustainable foundation for the development of socially and socio-economically oriented activities in the countryside. The conclusions should be interpreted with caution, as the small sample size and the local character of this study limit the possibility of generalizing the results. Moreover, due to the lack of data on actual economic, employment, or environmental outcomes, it is not possible to include objective measures of impact. This study was therefore designed as a descriptive analysis of perceptions and attitudes.

Representatives of agritourism farms, educational farms, and other non-agricultural enterprises play a significant role in shaping and strengthening social entrepreneurship capital. Their activities, based on inventive solutions and multifaceted social engagement, position them as natural change agents within their local environments. Through job creation, the integration of diverse social groups, and the promotion of local resources and traditions, they contribute to building strong social ties and enhancing trust within their communities. These initiatives are frequently grassroots in nature, meaning that they are embedded in the actual needs of the community and respond directly to the specific challenges faced by rural populations. Owing to their extensive networks with institutions, non-governmental organizations, and external partners, these leaders are able to mobilize both human and material capital, thereby fostering favorable conditions for the development of community-based initiatives.

The conclusions presented in this article have an applicative dimension and may serve as a basis for formulating local-level strategies aimed at strengthening social entrepreneurship. Particular attention should be paid to establishing systems of tangible support through the effective engagement of individuals and organizations operating in rural areas in order to initiate and implement social initiatives that combine economic and social objectives. Equally important is reinforcing the role of change leaders as animators of local life and fostering local partnerships that create an environment conducive to social innovation. The results offer a detailed descriptive overview of the characteristics of family farm owners in the region and the ways in which they perceive the communities in which they operate. This study also highlights a clear discrepancy between self-assessment and assessments of the local environment, which may serve as an important premise for future development efforts.

The findings confirm the presence of multiple constraints hindering the development of social entrepreneurship in rural settings. Among the most prominent are low levels of public awareness regarding the benefits of identifying real community needs and engaging directly in solving local problems. Limited access to information on funding opportunities for social entrepreneurship initiatives further discourages such activities. Deficiencies in competencies related to establishing and managing socially oriented organizations also constitute a major barrier to the development of social entrepreneurship in rural areas. Nonetheless, despite these challenges, the majority of research participants expressed a willingness to engage in socially beneficial activities, provided that adequate institutional support is available. A promising direction for further research involves situating rural social entrepreneurship within a multi-layered environment of influence encompassing local, regional, national, and international levels.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study is waived for ethical review as that the research do not raise any objections in terms of ethics and good practices established for research in the field of social sciences by Institution Committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The APC was funded by Faculty of Management, Częstochowa University of Technology, ul. H. Dąbrowskiego 69, 42-200 Częstochowa, Poland.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Leadbetter, C. The Rise of Social Entrepreneurship; Demos: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Zahra, S.A.; Gedajlovic, E.; Neubaum, D.O.; Shulman, J.M. A typology of social entrepreneurs: Motives, search processes and ethical challenges. J. Bus. Ventur. 2009, 24, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachura, A. Modelling of cross-organisational cooperation for social entrepreneurship. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachura, A. The perception of social enterprise in the background of features of social leaders. Humanit. Zarządzanie 2022, 23, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachura, A. Fields of synergy—Theory and practice of cooperation between social enterprises and business. Management 2024, 28, 155–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerawardena, J.; Mort, G.S. Investigating social entrepreneurship: A multidimensional model. J. World Bus. 2006, 41, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.K.; Gonin, M.; Besharov, M.L. Managing social-business tensions: A review and research agenda for social enterprise. Bus. Ethics Q. 2013, 23, 407–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chell, E.; Nicolopoulou, K.; Karataş-Özkan, M. Social entrepreneurship and enterprise: International and innovation perspectives. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2010, 22, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dees, J.G. The Meaning of Social Entrepreneurship; Duke University: Durham, NC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; New Society Publishers: Gabriola, BC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Yunus, M. Building Social Business: The New Kind of Capitalism That Serves Humanity’s Most Pressing Needs; PublicAffairs: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, R.; Fink, M. Rural social entrepreneurship: The role of social capital within and across institutional levels. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 70, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, A.; Farmer, J.; Bosworth, G. Rural social enterprise—Evidence to date, and a research agenda. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 70, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyes, D.; Ferri, P.; Henderson, F.; Whittam, G. The stairway to Heaven? The effective use of social capital in new venture creation for a rural business. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 39, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranjo-Valencia, J.C.; Ocampo-Wilches, A.C.; Trujillo-Henao, L.F. From social entrepreneurship to social innovation: The role of social capital. Study case in Colombian rural communities victim of armed conflict. J. Soc. Entrep. 2020, 13, 244–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Yousuf, S. Social capital and entrepreneurial intention: Empirical evidence from a rural community of Pakistan. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2019, 9, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrytsaienko, M.; Hrytsaienko, H.; Andrieieva, L.; Boltianska, L. The role of social capital in development of agricultural entrepreneurship. In Modern Development Paths of Agricultural Production; Nadykto, V., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorelli, H.B. Networks: Between markets and hierarchies. Strateg. Manag. J. 1986, 7, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleland, D.; Gareis, R. (Eds.) Global Project Management Handbook: Planning, Organizing and Controlling International Projects; McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Roxas, H.B.; Azmat, F. Community social capital and entrepreneurship: Analyzing the links. Community Dev. 2014, 45, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigkas, M.; Partalidou, M.; Lazaridou, D. Trust and other historical proxies of social capital: Do they matter in promoting social entrepreneurship in Greek rural areas? J. Soc. Entrep. 2020, 12, 338–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Jiang, D.; Pretorius, L. Trends in sustainable agricultural supply chain management. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2025, 31, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Motta Reis, J.S.; De Almeida Gastão, D.S.; Da Silva, N.R.; Santos, G.; Barbosa, L.C.F.M.; De Sá, J.C. The role of leadership in teams and in business. Prod. Eng. Arch. 2025, 31, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, H.; Zhu, Y.; Ness, D.; Xing, K.; Schneider, K. The role and characteristics of social entrepreneurs in contemporary rural cooperative development in China: Case studies of rural social entrepreneurship. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2014, 20, 379–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Friedrichs, Y.; Wahlberg, O. Social entrepreneurship in rural areas: A sports club’s mobilisation of people, money and social capital. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2016, 29, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochín, G.L.; López Parra, M.E.; Aguilera, Y.L. Financial education in rural communities: A demographic analysis. Research Reviews of Czestochowa University of Technology. Management 2025, 59, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbenyegah, A.T. Determining the risk and effect of selected social capital elements on rural entrepreneurship: Empirical study of two rural district municipalities. Risk Gov. Control Financ. Mark. Inst. 2018, 8, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejdys, J.; Gulc, A.M.; Magruk, A.; Kononiuk, A.; Magruk, A.; Rollnik-Sadowska, E. Future horizons in social innovation: Advancing employment for people with disabilities. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2025, 31, 84–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, J.P.H.; Thai, D.T.; Naybor, D. Social capital and female entrepreneurship in rural regions: Evidence from Vietnam. Appl. Geogr. 2012, 35, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).