Abstract

This work focuses on the development of a diagnostic approach for detecting and localizing sensor faults in an autonomous photovoltaic system. The considered system is composed of a photovoltaic module and a resistive load. However, an adaptation stage formed by a DC/DC voltage boost converter is necessary to transfer energy from the source to the load. The diagnostic scheme is based on a sliding mode observer (SMO) that is robust to uncertainties and parametric variations. The SMO incorporates adaptive gains optimized via parametric adaptation laws, with stability rigorously verified through Lyapunov analysis. The method effectively identifies both independent and simultaneous sensor faults, employing an optimized threshold selection strategy to balance detection sensitivity and false alarm resistance. Simulation results under varying environmental conditions, system parameter fluctuations, and noisy measurement demonstrate the approach’s superior performance, achieving a 20% reduction in mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) and 90% faster settling time compared to existing techniques. These enhancements immediately increase the dependability, efficiency, and lifetime of the PV system, which are critical for lowering carbon emissions and ensuring the economic feasibility of solar energy investments. Key innovations include a novel residual generation mechanism, seamless integration with backstepping sliding mode maximum power point tracking (MPPT) control, and enhanced transient response characteristics.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the field of photovoltaics has grown significantly due to a number of stimulating factors, including lower production costs and support policies pushed by global sustainability initiatives, as well as the urgent need to shift to low-carbon energy sources. These stimulating factors make the return on investment of a photovoltaic installation more and more interesting. However, like all other industrial processes, a photovoltaic system can be subjected, during its operation, to various faults and anomalies, leading to a drop in the performance of the system and even to the total unavailability of the system. All these unfavorable consequences will obviously reduce the productivity of the installation, increase its energy waste, and reduce the profit of the installation, which requires a maintenance cost to restore the system to normal. This threatens the economic and environmental sustainability of solar power. In [1,2], the authors presented an in-depth literature study on the different types of faults that can affect a photovoltaic (PV) system. Among these faults, we can cite partial shading faults, open-circuit faults, short-circuit faults, hot spot faults, as well as those that can occur in the sensors, switches, and passive components constituting the power converter used. Therefore, the development of diagnostic methods for fault detection in the behavior of PV systems is particularly important and necessary due to the degree of expansion of PV systems and the need to optimize their reliability, performance, and overall contribution to a sustainable energy mix [3]. In this context, different techniques for fault diagnosis and detection in PV systems have been developed during the last decade. In [1,2,3], a comprehensive overview of the most common fault detection approaches, exploiting all important types of faults in PV systems, is given. Extensive discussions on the effectiveness and performance of these techniques have been conducted. Artificial intelligence (AI) techniques have been employed to overcome the problems related to the detection and localization of faults affecting a PV system. A systematic review about the application of machine learning and deep learning approaches in fault diagnosis of PV systems is presented in [4,5,6,7]. This study has shown that the application of AI in PV fault detection is very accurate and efficient. Furthermore, in [8], the artificial neural network (ANN) is employed for the identification and detection of faults of an autonomous PV system. Indeed, the diagnostic system is composed of two ANN blocks: the first to model the healthy system and the second for the classification of the different faults. Additionally, an online two-layered thermal signature-based technique for fault monitoring in PV systems is developed in [9]. The method leverages temperature measurements from the front, back, and junction box of PV panels to detect and classify faults such as short circuits, open circuits, grounding, and partial shading. The approach offers a cost-effective, efficient, and precise solution for real-time fault diagnosis at the module level, enhancing PV system reliability and maintenance. Moreover, Hajji et al. [10] used the techniques of machine learning and deep learning for the diagnosis of a grid-tied PV system under variable solar radiation. Additionally, Garoudja et al. [11] presented a comparative study between the probabilistic neural network (PNN) and the ANN classifiers in term of robustness and accuracy. The obtained results validate the effectiveness of the PNN classifier to detect failures in PV systems in the cases of noisy and noise-free data. In [12], a novel method for diagnosing open-circuit faults in semiconductor power switches of three-phase grid-connected photovoltaic (PV) inverters is proposed. Indeed, a hybrid approach is introduced combining ReliefF-mRMR for multi-domain feature selection and Northern Goshawk Optimization-Hybrid Kernel Extreme Learning Machine (NGO-HKELM) for fault classification. The ReliefF-mRMR method ensures comprehensive fault feature extraction, while NGO-HKELM optimizes kernel parameters to balance generalization and exploration capabilities. Another data-driven approach for fault diagnosis in PV arrays is developed in [13], combining ANN, specifically radial basis functions, with machine learning techniques. Moreover, in [14], a diagnosis method based on time series and support vector machine (SVM) is proposed to improve the timeliness, accuracy, and feasibility of fault diagnosis for PV arrays. Additionally, in [15], a long short-term memory (LSTM) architecture is used to detect degradation in PV systems using performance ratios. A dataset including a PV array in normal and degraded states under different environmental conditions has been created to estimate the performance ratio. In contrast, a simple and reliable diagnostic method, based on voltage and current analysis, has been proposed for the detection of anomalies within PV modules. This approach allows the differentiation of different types of faults in varying environmental conditions. On the other hand, diagnostic methods based on nonlinear observers have attracted the attention of several researchers. The principle of these methods consists in generating residuals that are calculated by using the difference between the real outputs and those estimated by the observer. In [16,17], an extended Kalman filter (EKF) is used to overcome the problem of open-switch and sensor fault diagnosis for DC/DC converters. However, the EKF offers precise estimation but struggles with nonlinearities, while unscented Kalman filters (UKF) improve nonlinear handling at higher computational cost [18,19]. In [20,21], the extended Luenberger observer and the high gain observer are used for detection and isolation of open-circuit and short-circuit faults within a PV system, respectively. Thanks to its robustness against uncertainties and parameter variations, the sliding mode observer is employed for the diagnosis of PV systems presenting sensor and actuator faults [22].

The main objective of this work is the development of a sensor fault detection and isolation scheme within an isolated PV system. Such systems are frequently used in rural or off-grid settings where dependability is critical for sustainable community development and energy access. The developed structure is based on a sliding mode observer to generate the residuals. The motivation for choosing a sliding mode observer for sensor fault diagnosis is justified by the three key advantages of SMO that make it particularly suitable for photovoltaic systems operating in real-world, variable environments essential for sustainable infrastructure: (1) its inherent robustness to system uncertainties and parameter variations, which are common in real-world photovoltaic operations due to environmental fluctuations; (2) its finite-time convergence property, which enables rapid fault detection, essential for maintaining system stability and maximizing energy harvest; and (3) its relatively low computational complexity compared to data-driven methods, making it more practical for real-time implementation on low-cost hardware, thereby improving the economic sustainability of advanced monitoring solutions. In addition, the evaluation of the residuals is carried out by choosing a specific threshold.

To summarize the novel aspects of this work in the context of the existing literature, this paper consolidates its main contributions into a cohesive diagnostic framework that advances the state of the art. While individual techniques like sliding mode observers exist, the novelty of this research lies in the specific integration and enhancement of these components to create a more robust and efficient solution. The main contributions of this work are summarized in the following points:

- We have developed an efficient diagnostic approach using a single observer to estimate the state variables of the studied system.

- The presented method is able to detect and locate faults either in the simultaneous case or in the independent case.

- The detection performance over a range of threshold values in the presence of sensor faults, measurement noise, parameter variations, and varying environmental conditions is studied in order to determine the optimal threshold value.

- The residuals are generated in a robust way to avoid false alarms that can be caused by disturbances or noises.

- The sliding mode observer gains are determined through parametric adaptation laws that ensure system stability and enhance the efficiency of the diagnostic approach.

- Stability analysis of the sliding mode observer is conducted by choosing an appropriate Lyapunov function.

- A comparative study between the proposed diagnostic method and another existing in the literature was conducted based on a graphical and tabular analysis.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 is dedicated to presenting the mathematical model of the studied photovoltaic system. The mathematical development of the designed sliding mode observer is presented in Section 3. The objective of Section 4 is to illustrate the proposed diagnostic approach. The simulation results related to the application of the developed diagnostic method to the photovoltaic system are presented in Section 5. A comparative study will be conducted in Section 6 showing the effectiveness of the developed diagnostic approach. The conclusions of the paper are presented in Section 7, where some perspectives will be discussed.

2. Photovoltaic System Modeling

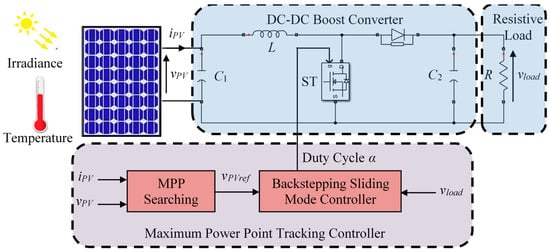

In this part, a mathematical model of the dynamics of an autonomous photovoltaic system is presented in order to introduce the fault diagnosis scheme. The nonlinear photovoltaic system studied in this paper is represented by the graph displayed in Figure 1. The considered system is composed of a photovoltaic module supplying a resistive load. However, an impedance matching stage between the source and the load is essential. This is done by integrating a DC/DC converter. The latter allows the extraction of maximum power from the photovoltaic module in order to transmit it to the load.

Figure 1.

Structure of the autonomous photovoltaic system.

A photovoltaic module is a set of cells connected in series or in parallel. Therefore, its model is based on that of a photovoltaic cell. According to [23], the mathematical model of a photovoltaic module is given by the following set of Equations:

where iPV, iph, i0, and vPV are the PV current, the photocurrent, the cell reverse saturation current, and the PV voltage, respectively. ns and np are the numbers of cells connected in series and in parallel, respectively. q is the electron charge, K is the Boltzmann constant, A is the ideality factor of the p-n junction, and T is the cell temperature. i0r, iscr and vOC denote, respectively, the reverse saturation current, the cell short-circuit current and the open-circuit voltage. Finally, Eg, Tr, Ki, and G are the band gap energy of the semi-conductor used in the cell, the cell reference temperature, the short-circuit current temperature coefficient, and the solar radiation, respectively.

The dynamic model of the DC/DC boost converter is established by applying the Kirchhoff’s laws in the two modes of operation of the switch (ST:ON/ST:OFF). Thus, we obtain the following differential equations [23].

In the following, we are interested in the development of a nonlinear observer based on the sliding mode theory. This observer will be used for the diagnosis of sensor faults affecting the photovoltaic system.

3. Sliding Mode Observer

The measurement of all the quantities of a physical process is often essential in order to implement state feedback control strategies, for example, or fault monitoring and diagnostic strategies. However, for technical or economic reasons, it is not always possible to access all the state variables representing these quantities. Hence, the development of an observer is required. This observer is responsible for estimating the state of the system. The use of sliding mode observers for nonlinear systems is motivated by their robustness to parametric uncertainties. For the development of the sliding mode observer, the following assumptions are taken into account for the autonomous photovoltaic system.

- The photovoltaic voltage vPV and the voltage across the load vload are measured variables, while the inductor current iL is unmeasured.

- The photovoltaic current iPV and the duty cycle α are known parameters.

The sliding mode observer consists of introducing discontinuous terms to force the system to reach the desired trajectory and to maintain the sliding motion around them [24]. Based on the sliding mode control principle, the observer designed to estimate vPV, vload, and iL has the following structure:

where , , and are the estimates of , , and respectively. , are the discontinuous terms.

Utilizing (5) and (6), the dynamics of the state estimation errors are as follows:

where respectively denote the photovoltaic voltage error, the load voltage error, and the inductor current error. They are defined in the following way:

The discontinuous terms (, ) are selected as follows:

, , , and are the sliding mode observer gains, and denotes the sign function. In order to prove the asymptotic stability of the sliding mode observer, the following theorem is proposed.

Theorem 1.

Given the system observation error (7) controlled by the discontinuous signals described in (9), the sliding mode is established around by selecting adaptive laws for the gains of the observer as follows:

where are positive constants and are the optimal values of , respectively.

Proof.

In order to prove the convergence of the system error dynamic towards zero, let us introduce the following candidate Lyapunov function:

The derivative of V is given by

Using Equations (7), (9), and (10) and performing the necessary developments, the derivative of the Lyapunov function V can be expressed as follows:

where and are two cross terms defined by

By choosing and , both cross terms and are equal to zero.

Thus, verifies the following inequality:

As a result, the system observation error converges asymptotically to zero. This demonstrates the stability of the observer. □

4. Sensor Fault Detection and Isolation Strategy with Sliding Mode Observer

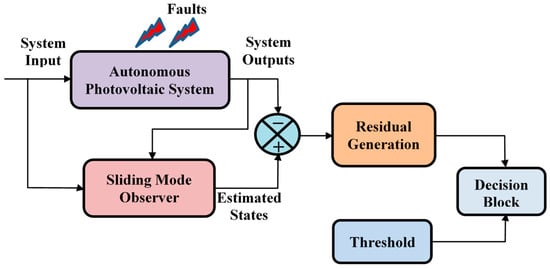

Figure 2 shows the overall diagram of the developed diagnostic approach. This method is based on the use of a sliding mode observer to generate the residuals. This observer allows for the estimation of the predicted state values using the same input (backstepping sliding mode controller) as the actual PV system. Subsequently, the residuals are generated between the nominal state values and the values estimated by the sliding mode observer. The residuals are then evaluated against threshold values. A fault is considered to occur when the generated residual exceeds the threshold values.

Figure 2.

Diagram of the diagnostic approach.

4.1. Residuals Generation

The first step in a fault diagnosis and identification procedure is the generation of residuals. Indeed, it is an indicator of system failure. In the case of observer-based diagnostic approaches, the residuals represent the difference between the actual output and the estimated output [25]. In other words, it is the estimation error. As mentioned earlier, vPV and vload are assumed to be measurable, while the variable iL is assumed to be unmeasurable. For sensor fault detection, two residuals r1 and r2 will be considered as follows:

After generating the residuals, the second step of the fault diagnosis and identification system is fault detection. This step determines the presence or absence of a fault. Detection involves evaluating the residuals against a suitably chosen threshold [26].

4.2. Threshold Selection

The selection of tolerable threshold values is generally critical for accurate fault diagnosis. Most often, the smaller the threshold values, the shorter the detection time for faults. However, small threshold values can easily lead to false alarms, which reduce the reliability of the diagnosis. On the other hand, high threshold values would slow down the diagnostic process. Thus, threshold values have a direct impact on the robustness and speed of diagnosis [27]. These two aspects must be carefully balanced so that the false alarm rate and the missed detection rate are low. Ideally, the residuals of a fault-free system hover around zero values. The threshold or limit values that allow for fault detection are defined as follows:

where denotes the residual vector when the system operates without faults.

The decision logic for the sensor faults is designed as follows:

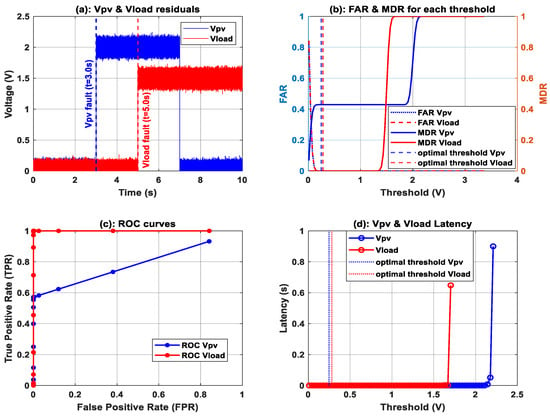

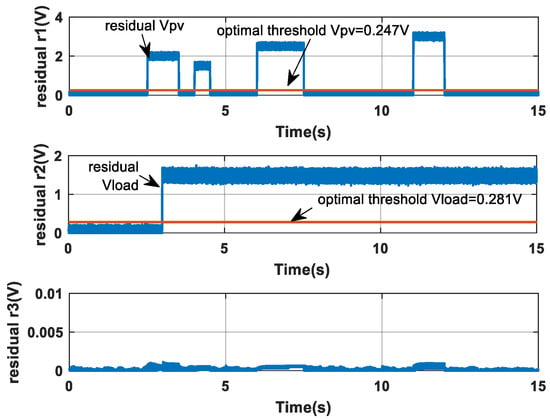

4.3. Threshold Sensitivity

This section will focus on the study of threshold sensitivity. Complete simulations are conducted to assess detection performance across a range of threshold values, enabling us to identify the optimal thresholds. The simulations will account for sensor faults, measurement noise, parameter variations, and changing environmental conditions. Specifically, an intermittent fault was introduced to the voltage vPV during the interval [3 s, 7 s], and an abrupt fault was applied to the voltage vload at time t = 5 s. Gaussian noise is added to the measured variables (vPV and vload). Additionally, variations were made to the passive components of the DC/DC converter (inductance L and the two capacitors C1 and C2), as well as the resistive load (R), with these parameters experiencing a 20% increase from their nominal values. Furthermore, the temperature T rises from 25 °C to 28 °C at time t = 5 s, and the illumination G increases from 600 W/m2 to 1000 W/m2 at time t = 5 s. To quantitatively assess the detection performance for each threshold value, we employ three key metrics: the False Alarm Rate (FAR), the Missed Detection Rate (MDR), and the detection Latency. These are defined as follows:

- The False Alarm Rate (FAR) is the percentage of false alarms generated during normal operation. It is calculated as

- The Missed Detection Rate (MDR) is the percentage of actual faults that the system fails to detect. It is calculated aswhere Nuf denotes the number of undetected faults and Tf is the total number of faults.

- The detection Latency is the time delay between the instant a fault is injected and the moment it is successfully detected. It is defined as

The simulation results offer a thorough evaluation of the sliding mode observer-based fault detection system for photovoltaic application. Figure 3a illustrates the residual amplitudes for both PV voltage (vPV) and load voltage (vload), distinctly showing spikes at the intentional fault injection times (3 s and 5 s, respectively). These residual signals exhibit excellent sensitivity to faults while maintaining stability during normal operation, with noise levels remaining below 0.2 V in fault-free conditions. Figure 3b shows the classic trade-off between FAR and MDR as the threshold varies. At low thresholds, FAR exceeds 50%, indicating excessive false alarms. At high thresholds, MDR surpasses 70%, rendering the system insensitive to faults. The optimal thresholds (0.247 V for vPV and 0.281 V for vload) strike a balance, achieving FAR < 3% and MDR < 2%. Figure 3c presents the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve, a fundamental tool for evaluating the diagnostic capability of the fault detection system. This curve visualizes the trade-off between True Positive Rate (TPR) and False Positive Rate (FPR). This figure demonstrates the exceptional diagnostic capability of the proposed SMO, with an Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 0.78 and 0.98 for vPV and vload, respectively. The curve’s proximity to the top-left corner indicates near-perfect discrimination between normal and faulty operation. Figure 3d presents the latency characteristics of the fault detection system, showing the time delay between fault occurrence and detection across different threshold values. This is crucial for evaluating the real-time performance of the diagnostic approach. The latency analysis exhibits our system’s real-time capability, with detection delays below 3 ms for the optimal thresholds. The exponential increase in latency beyond 2 V thresholds confirms the necessity of our threshold optimization approach.

Figure 3.

Threshold sensitivity analysis.

5. Results and Discussion

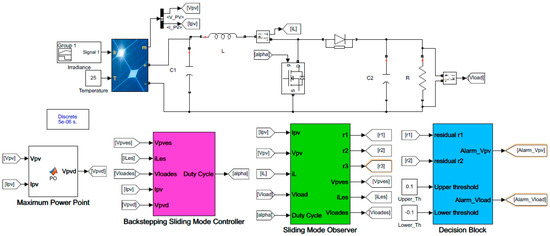

In this section, we will evaluate the performance of the sliding mode observer-based diagnostic approach using numerical simulations within the Matlab/Simulink version 2020 environment. To achieve this, we considered two specific sensor fault cases.

First case: Independent multiple sensor faults functioning under a closed-loop control law alongside abrupt changes in environmental conditions and system parameters.

Second case: Simultaneous multiple sensor faults operating within a closed-loop control law amid rapid fluctuations in environmental conditions and system parameters.

For the two considered cases, the overall simulation scheme is composed of a photovoltaic generator, a DC/DC boost converter, a resistive load, a backstepping sliding mode MPPT controller, a residual generation block, and a decision block as illustrated in Figure 4. The parameters of the photovoltaic generator are gathered in Table 1. The values of the passive components constituting the boost converter are and . The load has a value of . The performance of the sliding mode observer is assessed in the presence of noisy measurement and parametric variations in the passive components of the boost converter, the resistive load, and climatic conditions. The resistive load and passive components experience a 20% increase in their nominal values. The irradiance rises from to at , then drops to at . The temperature rises from 25 °C to 28 °C at .

Figure 4.

Simulation scheme.

Table 1.

PV module KC200GH-2P specifications (Kyocera Corporation, Kyoto, Japan).

5.1. First Case: Independent Multiple Sensor Faults

This part presents the simulation results related to the application of the diagnostic scheme considering independent sensor faults. Indeed, an intermittent fault fvPV and an abrupt fault fvload have been introduced on the output voltage of the photovoltaic module vPV and on the voltage across the load vload, respectively. Equations (23) and (24) illustrate the expressions of fvPV and fvload.

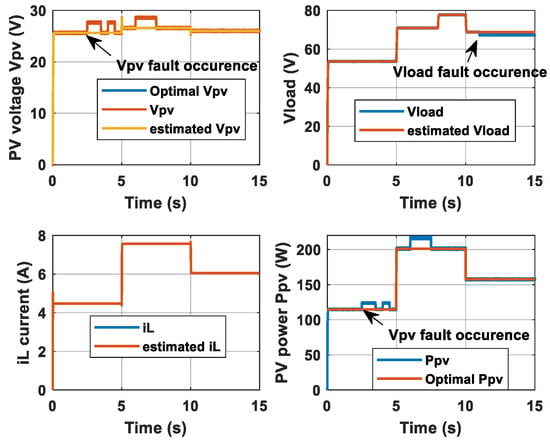

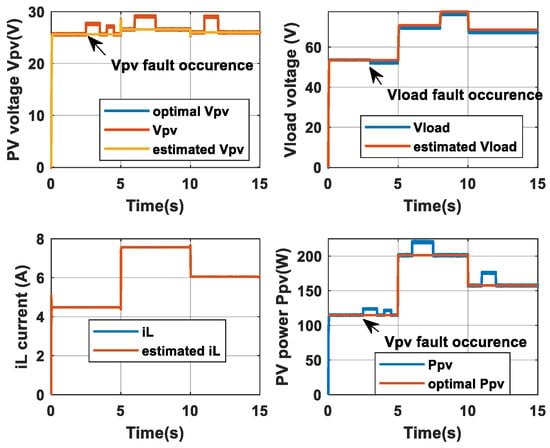

The simulation results are illustrated in Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8. Figure 5 depicts the graphical representations of the three state variables of the system (vPV, vload, and iL), as well as their estimates obtained from the sliding mode observer. These results demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed method for estimating the states of the system despite the presence of fluctuations in environmental conditions, system parameter variations, and sensor faults. Furthermore, this figure shows the evolution of the power pPV generated by the solar panel and the optimal power. It can be inferred that the backstepping sliding mode controller allows the extraction and tracking of the maximum power point for each level of sunlight. On the other hand, the generated power is sensitive to the sensor fault of the voltage vPV.

Figure 5.

Evolutions of the PV power and of (vPV, vload, and iL) and their estimates for case 1.

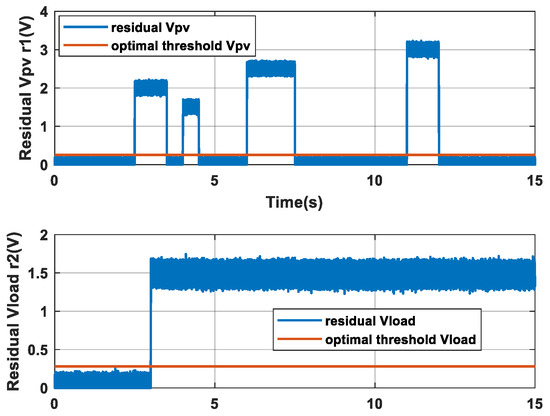

Figure 6.

Evolution of residuals (r1 and r2) for the first case.

Figure 7.

Evolution of (vPV and vload) faults detection signals for case 1.

Figure 8.

Sliding mode observer gains λ1, λ2, K1, and K2 for case 1.

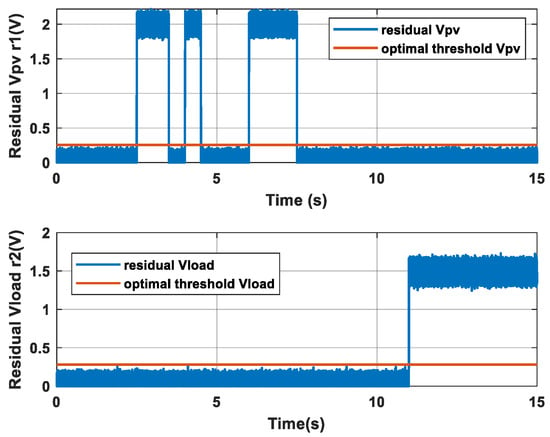

Figure 6 illustrates the evolution of the residuals r1 and r2 associated with the variables vPV and vload, respectively. At the moments when the two faults are applied, the residuals r1 and r2 deviate from their initial values (zero), which proves the detection of a fault.

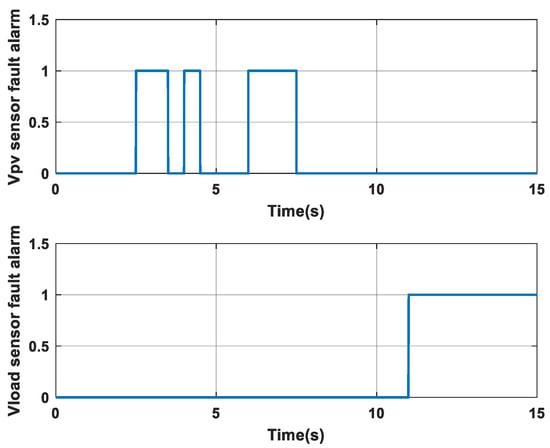

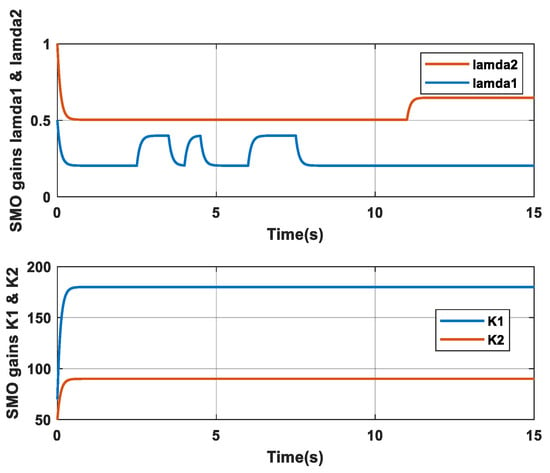

The faults are quickly detected when the residuals exceed the optimal thresholds, as shown in Figure 7. Figure 8 illustrates the evolution of the observer gains. By analyzing this figure, we observe that the gains λ1 and λ2 converge to their optimal values when there is no fault and stabilize at a different value when a fault is present. Furthermore, the gains K1 and K2 also converge to their optimal values. Consequently, the proposed diagnostic scheme demonstrates robustness in detecting and locating the separately introduced sensor faults.

5.2. Second Case: Simultaneous Multiple Sensor Faults

This part illustrates the performance of the proposed diagnostic approach in the case where faults occur simultaneously. In fact, two additive faults were applied to the first vPV sensor and the second vload sensor according to the two Equations (25) and (26).

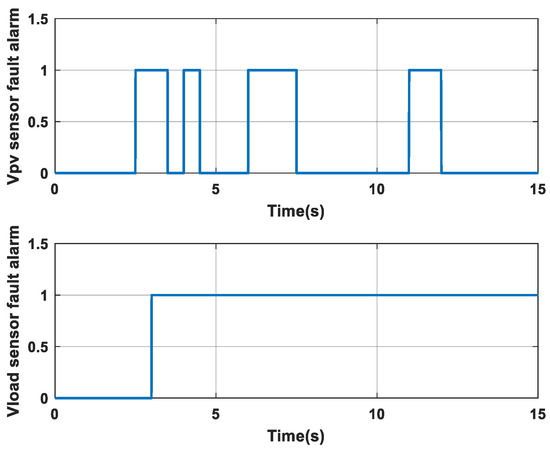

The simulation results corresponding to the application of simultaneous sensor faults are presented in Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12. Figure 9 displays the outputs of the system and the observer, as well as the evolution of power delivered by the photovoltaic module and its optimal value. These results demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed method for state estimation and maximum power point tracking, even for a system subjected to variations in climatic conditions, system parameter variations, and sensor faults.

Figure 9.

Evolution of the PV power and of (vPV, vload, and iL) and their estimates for case 2.

Figure 10.

Evolution of residuals (r1 and r2) for the second case.

Figure 11.

Evolution of (vPV and vload) fault detection signals for case 2.

Figure 12.

Sliding mode observer gains λ1, λ2, K1, and K2 for case 2.

The residuals r1 and r2, illustrated in Figure 10, are zero before the application of the faults, while they quickly reach a certain value when a fault occurs. A fault is detected when the residual exceeds the optimal threshold value.

Additionally, Figure 11 demonstrates that the developed diagnostic approach allows for the detection and localization of the simultaneously applied sensor faults.

6. Comparative Study

The objective of this section is to conduct a comparative study between the proposed diagnostic method and the one developed by [28]. To contextualize this comparison within the broader field, Table 2 provides a summarized overview of various fault diagnosis approaches for PV systems, highlighting their relative strengths and limitations across key operational metrics. Following this, a direct graphical and quantitative comparison with the method from [28] is conducted under identical simulation conditions.

Table 2.

Comparative Analysis of PV Fault Diagnosis Approaches.

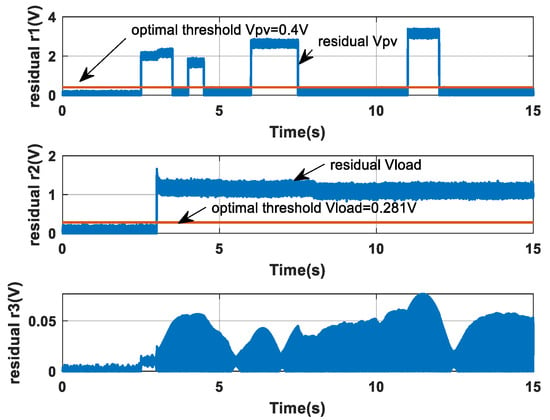

The fault detection approach presented in [28] relies on a sliding mode observer for generating residuals, while employing backstepping control for tracking the maximum power point. The observer’s gains are determined empirically. In [28], the authors focused on a single fault affecting the voltage supplied by the photovoltaic generator vPV, whereas this work considers two faults impacting both the voltage vPV and the voltage at the load terminals vload. To facilitate the comparison between the two methods, numerical simulations were performed under identical conditions. Specifically, two simultaneous intermittent faults were introduced to the voltage sensors vPV and vload. Additionally, white noise with a mean of zero and a variance of 0.05 was added to the measured variables, along with sudden variations in illumination, temperature, and system parameters.

The comparative study is based on an analysis of estimation errors by evaluating several performance indices, namely: Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Integral Square Error (ISE), Integral Absolute Error (IAE), and Integral Time Absolute Error (ITAE). Mathematically, these functions are defined as follows:

On the other hand, the comparison between the two approaches is carried out in terms of characteristics of the transient response such as: rise time, settling time, overshoot, and steady state error. Moreover, the comparative study includes quantitative measures such as false alarm rate (FAR), missed detection rate (MDR), and detection latency.

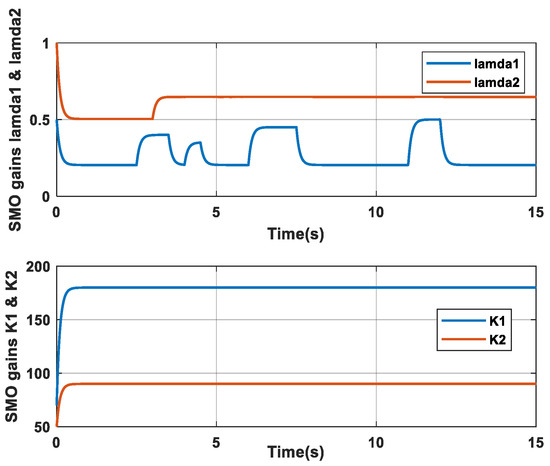

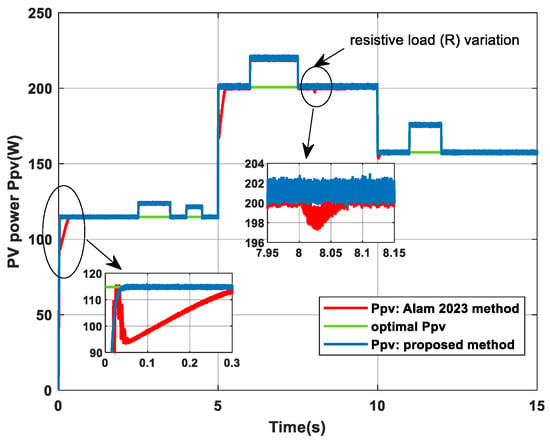

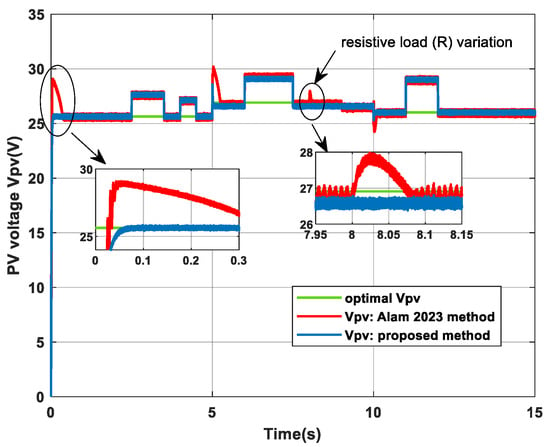

The comparison of the two approaches relies on graphical and tabular analysis. A deeper analysis of the graphical results in Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15 and Figure 16 provides critical insights into the performance differences between the two diagnostic approaches.

Figure 13.

Evolution of residuals obtained by the proposed diagnostic method.

Figure 14.

Evolution of residuals obtained by the diagnostic method in Ref. [28].

Figure 15.

Evolution of pPV power with both diagnostic approaches [28].

Figure 16.

Evolution of the vPV voltage with the two diagnostic schemes [28].

Examining the residuals in Figure 13 (proposed method) and Figure 14 (method from [28]) reveals a fundamental distinction in robustness. In Figure 14, the residual r3 exhibits significant deviations when a fault is injected into the PV voltage sensor and the load voltage sensor. This cross-sensitivity indicates that the method from [28] struggles to fully decouple simultaneous faults, which can lead to ambiguity in fault isolation. In contrast, the residuals generated by the proposed method (Figure 13) remain largely unaffected by faults on the non-corresponding sensor. This demonstrates the superior isolation capability of our adaptive SMO, which is a direct result of the optimized gains and the structured residual generation mechanism.

Furthermore, the transient performance illustrated in Figure 15 and Figure 16 underscores the advantage of the integrated control and diagnostic design. The proposed method exhibits a much faster recovery and tighter tracking of the optimal power point and PV voltage reference following disturbances, such as the step change in irradiance at t = 5 s and the resistive load variation. The method from [28] shows more pronounced oscillations and a longer settling time.

Furthermore, the results can be assessed by examining Table 3, Table 4, and Table 5, which provide a comparison of error performance metrics, transient response characteristics, and threshold sensitivity metrics, respectively.

Table 3.

Comparison between both diagnostic methods in terms of error performance metrics.

Table 4.

Comparison between both diagnostic approaches in terms of transient response characteristics.

Table 5.

Comparison between both diagnostic approaches in terms of threshold sensitivity.

As illustrated in Table 3, the proposed diagnostic scheme, which utilizes a backstepping sliding mode controller in conjunction with a sliding mode observer, demonstrates exceptional performance with the lowest values of MAPE, RMSE, ISE, IAE, and ITAE for e1 and e2, thereby indicating higher error performance metrics.

In the same way, the data presented in Table 4 clearly shows that the control law used in the proposed diagnostic approach achieves the best transient response characteristics in terms of rise time, settling time, overshoot, and steady state error.

Moreover, according to Table 5, the proposed diagnostic method presents the minimum FAR, MDR, and latency detection metrics compared to the diagnostic approach presented in [28]. Thus, the proposed diagnostic scheme reveals higher performance in both error metrics and transient response characteristics.

7. Conclusions

The increased demand for clean energy requires reliability and permanent availability of energy production systems that are subject to failures of various kinds. Proactive problem diagnosis is no longer a luxury, but rather a must for reaching the high levels of system uptime and efficiency needed for solar energy to realize its promise as a cornerstone of a sustainable energy future. In order to maintain the system permanently in operation and maximize its energy yield, we have presented in this article a robust sliding mode observer-based fault detection framework that successfully addresses critical challenges in sensor fault identification for autonomous PV systems. The proposed methodology demonstrates exceptional performance in detecting and isolating both independent and simultaneous sensor faults affecting PV voltage and load voltage measurements, with comprehensive validation under varying environmental conditions, varying system parameters, and noisy measurement. Key achievements include a 20% reduction in mean absolute percentage error (MAPE = 0.4559) and 90% faster settling time (0.0292 s) compared to another method, directly translating to less energy loss and more resilient power generation, while maintaining system stability through rigorous Lyapunov analysis and adaptive gains. The research makes three primary contributions: (1) a novel residual generation mechanism that effectively distinguishes between sensor faults and system disturbances, (2) an optimized threshold selection strategy that balances detection sensitivity and false alarm resistance, reducing unnecessary maintenance visits and their associated carbon footprint, and (3) a complete diagnostic architecture integrating the SMO with maximum power point tracking control to safeguard the system’s operational efficiency. Future work will focus on five critical extensions: first, scaling the approach for grid-connected systems by incorporating inverter fault detection and harmonic analysis; second, investigating the scalability and performance of the proposed method in larger PV arrays with multiple strings and different module technologies; third, improving diagnostic intelligence by using machine learning-based fault categorization algorithms to forecast and avoid faults, hence increasing system longevity; fourth, considering developing a fault-tolerant control law to ensure ongoing operation even in degraded modes, which is an essential element for important sustainable infrastructure; and fifth, validating the system through hardware-in-the-loop experiments. These developments will bridge the gap between theoretical innovation and industrial application, particularly for large-scale PV plants where sensor reliability directly impacts energy yield and the overall return on investment and environmental benefit.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B. and K.D.; Methodology, A.B. and K.D.; Software, K.D.; Validation, K.D.; Formal analysis, A.B.A.; Investigation, A.B.A.; Resources, K.D.; Writing—original draft, K.D.; Visualization, A.B.A.; Supervision, A.B.A.; Project administration, A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Jouf University under grant No. (DGSSR-2024-02-02178).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Madeti, S.R.; Singh, S.N. A comprehensive study on different types of faults and detection techniques for solar photovoltaic system. Sol. Energy 2017, 158, 161–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghezouit, B.; Harrou, F.; Sun, Y.; Merrouche, W. Model-based fault detection in photovoltaic systems: A comprehensive review and avenues for enhancement. Results Eng. 2024, 21, 101835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmani, K.; Haddad, A.; Lemenand, T.; Castanier, B.; Alkhedher, M.; Ramadan, M. A critical review of PV systems faults with the relevant detection methods. Energy Nexus 2023, 12, 100257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Rashel, M.R.; Ahmed, M.T.; Kamrul Islam, A.K.M.; Tlemçani, M. Artificial Intelligence in Photovoltaic Fault Identification and Diagnosis: A Systematic Review. Energies 2023, 16, 7417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurukuru, V.S.B.; Haque, A.; Khan, M.A.; Sahoo, S.; Malik, A.; Blaabjerg, F. A Review on Artificial Intelligence Applications for Grid-Connected Solar Photovoltaic Systems. Energies 2021, 14, 4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, H.F.M.; Rebollo, M.Á.G.; Cardeñoso-Payo, V.; Gómez, V.A.; Plaza, A.R.; Moyo, R.T.; Hernández-Callejo, L. Applications of Artificial Intelligence to Photovoltaic Systems: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 10056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navid, Q.; Hassan, A.; Fardoun, A.A.; Ramzan, R.; Alraeesi, A. Fault Diagnostic Methodologies for Utility-Scale Photovoltaic Power Plants: A State of the Art Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aallouche, H.; Ouadi, H. Online fault detection and identification for an isolated PV system using ANN. IFAC Pap. 2022, 55, 468–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navid, Q.; Hassan, A.; Fardoun, A.A.; Ramzan, R. An Online Novel Two-Layered Photovoltaic Fault Monitoring Technique Based Upon the Thermal Signatures. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajji, M.; Yahyaoui, Z.; Mansouri, M.; Nounou, H.; Nounou, M. Fault detection and diagnosis in grid-connected PV systems under irradiance variations. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 4005–4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garoudja, E.; Chouder, A.; Kara, K.; Silvestre, S. An enhanced machine learning based approach for failures detection and diagnosis of PV systems. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 151, 496–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, T.; Qiu, Z.; Gao, H.; Zhu, S. A Method Based on NGO-HKELM for the Autonomous Diagnosis of Semiconductor Power Switch Open-Circuit Faults in Three-Phase Grid-Connected Photovoltaic Inverters. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9588. [Google Scholar]

- Zare, A.; Simab, M.; Nafar, M.; Rodrigues, E.M.G. A novel method for fault diagnosis in photovoltaic arrays used in distribution power systems. Energy Syst. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Zhang, B.; Ji, X.; Wu, J. Fault Diagnosis of PV Array Based on Time Series and Support Vector Machine. Int. J. Photoenergy 2024, 2024, 2885545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadashpour, A.; Eskandari, A.; Nedaei, A.; Salehpour, S.; Parvin, P.; Livera, A.; Makrides, G.; Aghaei, M.A. Novel Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM)-based Degradation Detection in Photovoltaic Systems using Performance Ratio. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Energy Transition in the Mediterranean Area (SyNERGY MED), Limassol, Cyprus, 21–23 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, S.; Tang, D.; Hang, J.; Zhao, J.; Gui, S. Robust Open-Switch Fault Diagnosis of Bidirectional DC/DC Converters Based on Extended Kalman Filter with Multiple Corrections. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. 2024, 71, 4363–4374. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, M.; Chafouk, H.; El Mehdi Ardjoun, S.A. Fault Diagnosis in Wind Turbine Current Sensors: Detecting Single and Multiple Faults with the Extended Kalman Filter Bank Approach. Sensors 2024, 24, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varnoosfaderani, N.H.; Khorsandi, A. State estimation in an islanded hybrid solar-wind DC microgrid using Unscented Kalman Filter. Heliyon 2025, 11, e42073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamalinia, E.; Zhang, Z.; Khazaei, J.; Blum, R.S. Data-Driven Dynamic State Estimation of Photovoltaic Systems via Sparse Regression Unscented Kalman Filter. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2025, 21, 2550–2559. [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza Trejo, D.R.; Taheri, S.; Pecina Sánchez, J.A. Switch fault diagnosis for boost DC–DC converters in photovoltaic MPPT systems by using high-gain observers. IET Power Electron. 2019, 12, 2793–2801. [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza Trejo, D.R.; Bárcenas, E.; Hernández Díez, J.E.; Bossio, G.; Espinosa Pérez, G. Open- and Short-Circuit Fault Identification for a Boost dc/dc Converter in PV MPPT Systems. Energies 2018, 11, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, E.; Khan, A.U.; Iqbal, M.; Saeed, A.; Hafeez, G.; Waseem, A.; Albogamy, F.R.; Ullah, Z. Sensor Fault-Tolerant Control of Microgrid Using Robust Sliding-Mode Observer. Sensors 2022, 22, 2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahech, K.; Allouche, M.; Damak, T.; Tadeo, F. Backstepping sliding mode control for maximum power point tracking of a photovoltaic system. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2017, 143, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Yao, L. Sliding mode observer-based fault diagnosis and continuous control set fault tolerant control for PMSM with demagnetization fault. Measurement 2024, 235, 114867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Azeem, F.; Zidan, H.A. Robust residual generator design for sensor fault detection in twin rotor aerodynamic system. e-Prime-Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 2024, 8, 100620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ge, X.; Shen, W. Multi-objective nonlinear observer design for multi-fault detection of lithium-ion battery in electric vehicles. Appl. Energy 2024, 362, 122989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammed Ramees, M.K.P.; Waseem Ahmad, M.A. Noninvasive Sliding Mode Observer Based Approach for Detecting Open-Circuit Faults in HERIC Inverters. e-Prime-Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 2024, 10, 100793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, Z.; Khan, M.A.; Khan, Z.A.; Ahmad, W.; Khan, I.; Khan, Q.; Irfan, M.; Nowakowski, G. Fault Diagnosis Strategy for a Standalone Photovoltaic System: A Residual Formation Approach. Electronics 2023, 12, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).