Carbon Fraction Distribution in Forest Soils and Leaf Litter Across Vegetation Types in El Chico National Park, Mexico

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

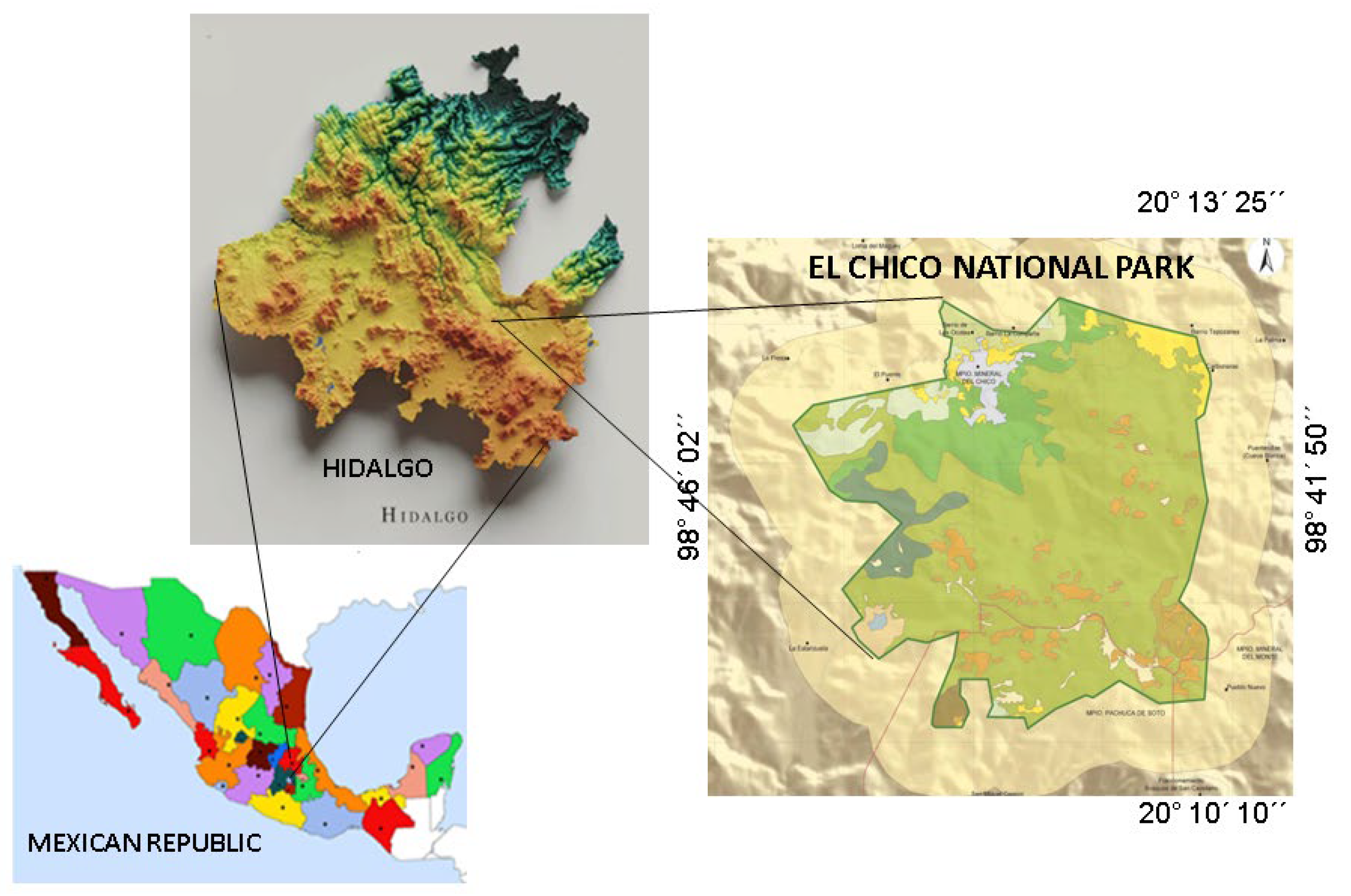

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sampling Design and Representativeness

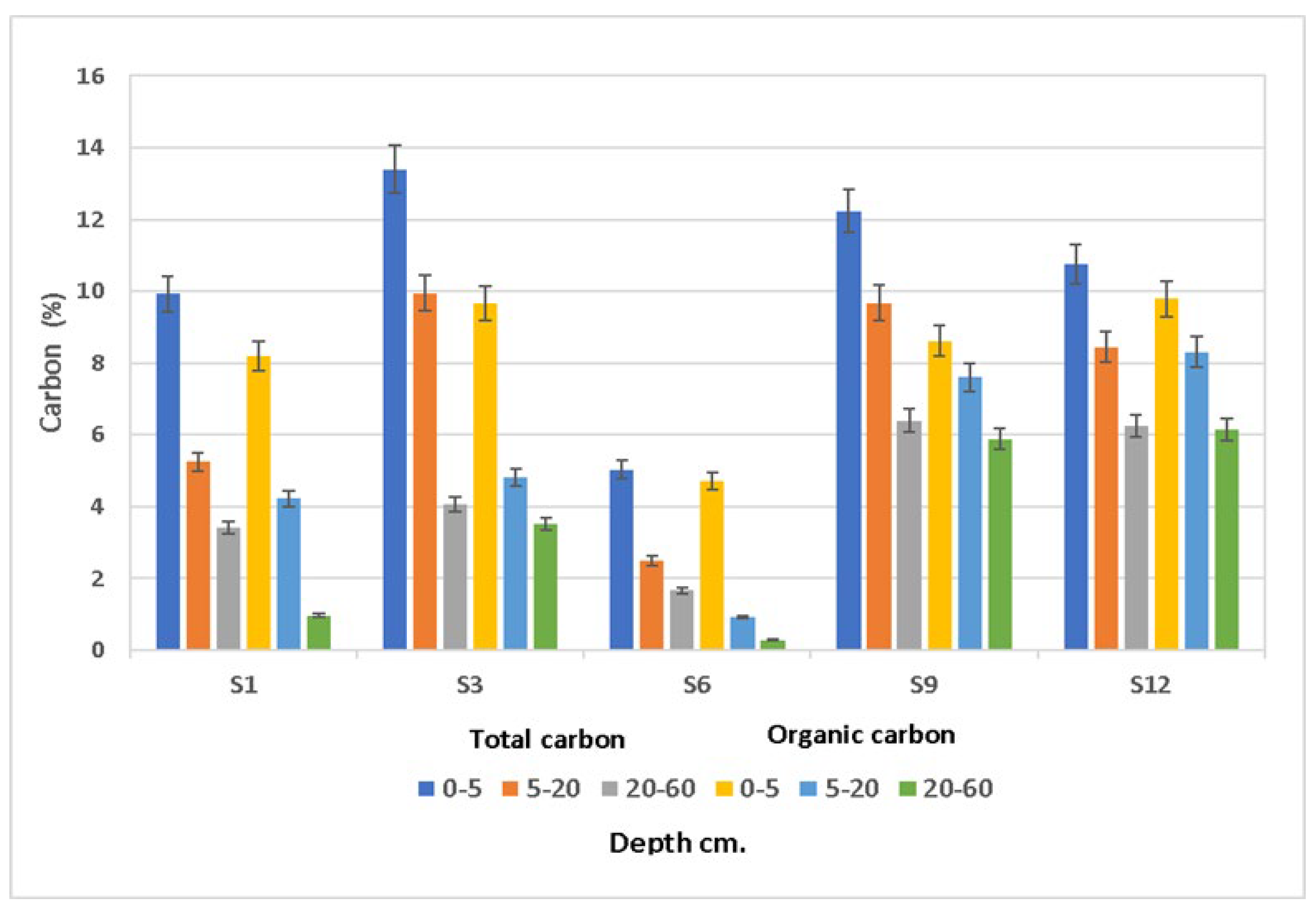

3. Results

4. Discussion

- Low: <50 Mg C ha−1;

- Medium: 50–100 Mg C ha−1;

- High: 100–150 Mg C ha−1;

- Very High: >150 Mg C ha−1.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ambrosio-Lazo, A.; Rodríguez-Ortiz, G.; Santiago-García, W.; Ruiz-Luna, J.; Velasco-Velasco, V.A.; Enríquez-del Valle, J.R. Biomasa aérea y carbono en el suelo en rodales de pino-encino bajo tratamiento silvícola. Madera Bosques 2024, 30, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galicia, L.; Saynes, V.; Campo, J. Biomasa aérea, subterránea y necromasa en una cronosecuencia de bosques templados con aprovechamiento forestal. Bot. Sci. 2015, 93, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincă, L.C.; Dincă, M.; Vasile, D.; Spârchez, G.; Holonec, L. Calculating Organic Carbon Stock from Forest Soils. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobo 2015, 43, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Soil carbon sequestration impacts on global climate change and food security. Science 2004, 304, 1623–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockmann, U.; Adams, M.; Crawford, J.; Field, D.; Henakaarchchi, N.; Jenkins, M.; Minasny, B.; McBratney, A.; Courcelles, V.R.d.; Singh, K.; et al. The knowns, known unknowns and unknowns of sequestration of soil organic carbon. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2013, 164, 80–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization). Global Forest Resources Assessment 2015; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2015; ISBN 978-92-5-108826-5. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Secuestro de carbono en tierras áridas. FAO Soils Bull. 2007, 102, 107. [Google Scholar]

- Bruun, T.B.; Elberling, B.; De Neergaard, A.; Magid, J. Organic carbon dynamics in different soil types after conversion of forest to agriculture. Land Degrad. Dev. 2013, 26, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willaarts, B.A.; Oyonarte, C.; Muñoz-Rojas, M.; Ibáñez, J.J.; Aguilera, P.A. Environmental factors controlling soil organic carbon stocks in two contrasting Mediterranean climatic areas of southern Spain. Land Degrad. Dev. 2016, 27, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplin-Kramer, R.; Ramler, I.; Sharp, R.; Haddad, N.; Gerber, J.; West, P.; Mandle, L.; Engstrom, P.; Baccini, A.; Sim, S.; et al. Degradation in carbon stocks near tropical forest edges. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 10158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Castruita, M.; Sánchez-Guzmán, P.; Ortiz-Solorio, C.; Gutiérrez-Castorena, M.C. Carbono orgánico de los suelos de México. Terra Latinoamericana 2005, 23, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Broquen, P.; Candan, F.; Lobartini, J.C.; Girardin, J.L. Relaciones entre carbono orgánico y propiedades edáficas y del sitio en suelos derivados de cenizas volcánicas, sudoeste de Neuquén (Argentina). Cienc. Suelo 2004, 22, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- De Souza, J.J.L.L.; Souza, B.I.; Xavier, R.A.; Cardoso, E.C.M.; de Medeiros, J.R.; da Fonseca, C.F.; Schaefer, C.E.G.R. Organic carbon rich-soils in the Brazilian semiarid region and paleoenvironmental implications. Catena 2022, 212, 106101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancourt, P.; González, J.; Figueroa, B.; González, F. Materia orgánica y caracterización de suelos en proceso de recuperación con coberturas vegetativas en zonas templadas de México. Terra Latinoamericana 1999, 17, 139–148. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Captura de carbono en los suelos para un mejor manejo de la tierra. FAO Soils Bull. 2002, 96, 61. [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo-Arizmendi, L.; Pérez-Suarez, M.; Vargas-Hernández, J.J.; Rozenberg, P.; Correa-Díaz, A. Existencias de carbono orgánico del suelo a lo largo de un gradiente altitudinal en bosques de montaña de Pinus hartwegii Lind. Rev. Mex. Cienc. For. 2025, 16, 87–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galicia, L.; Gamboa, C.A.M.; Cram, S.; Chávez, V.B.; Peña, R.V.; Saynes, V.; Siebe, V. Almacén y dinámica del carbono orgánico del suelo en bosques templados de México. Terra Latinoamericana 2016, 34, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Óskarsson, H.; Arnalds, Ó.; Gudmundsson, J.; Gudbergsson, G. Organic carbon in Icelandic Andosols: Geographical variation and impact of erosion. Catena 2004, 56, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, C.; Tsai, C.; Chen, Z. Soil organic carbon stocks in relation to elevation gradients in volcanic ash soils of Taiwan. Geoderma 2013, 209–210, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imaya, A.; Yoshinaga, S.; Inagaki, Y.; Tanaka, N.; Ohta, S. Volcanic ash additions control soil carbon accumulation in brown forest soils in Japan. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2010, 56, 734–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razo-Zárate, R.; Gordillo-Martínez, A.J.; Rodríguez-Laguna, R.; Maycotte-Morales, C.C.; Acevedo-Sandoval, O.A. Estimación de biomasa y carbono almacenado en árboles de oyamel afectados por el fuego en el Parque Nacional “El Chico”, Hidalgo, México. Madera Bosques 2013, 19, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora, J. Estimación del Contenido de Carbono en Biomasa Aérea en el Bosque de Pino del Ejido La Majada, Municipio de Peribán de Ramos, Michoacán. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo, Morelia, Mexico, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- CONANP (Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas). Programa de Conservación y Manejo Del Parque Nacional El Chico; CONANP: Ciudad de México, México, 2005; p. 236. [Google Scholar]

- Enciso-de la Vega, S. Propuesta de nomenclatura estratigráfica para la cuenca de México. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Geol. 1992, 10, 26–36. [Google Scholar]

- World Reference Base for Soil Resources (WRB). Report No. 84; FAO-ISRIC-IUSS: Rome, Italy, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- WRB; IUSS Working Group. Base Referencial Mundial del Recurso Suelo. Sistema Internacional De Clasificación De Suelos Para La Nomenclatura De Suelos Y La Creación De Leyendas De Mapas De Suelos, 4th ed.; Unión Internacional de las Ciencias del Suelo (IUSS): Viena, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Soil Survey Staff. Keys to Soil Taxonomy, 9th ed.; USA Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo-Sandoval, O.; Prieto-García, F.; Gordillo-Martínez, A. Identificar las fracciones de aluminio en un andosol del estado de Hidalgo, México. Rev. Soc. Geol. Esp. 2009, 21, 125–132. [Google Scholar]

- Soil Survey Laboratory. Methods Manual; Soil Survey Investigations Report No. 42; Ver. 3.0; USA Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Norma Oficial Mexicana. Que Establece Las Especificaciones De Fertilidad, Salinidad Y Clasificación De Suelos, Estudio, Muestreo Y Análisis. NOM-021-SEMARNAT-2000; Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales: Mexico City, Mexico, 2000.

- González-Molina, L.; Etchevers-Barra, J.D.; Hidalgo-Moreno, C. Carbono en suelos de ladera: Factores que deben considerarse para determinar su cambio en el tiempo. Agrociencia 2008, 42, 741–751. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B.F.L. Characterization of poorly ordered minerals by selective chemical methods. In Clay Mineralogy: Spectroscopic and Chemical Determinative Methods; Wilson, M.J., Ed.; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1994; pp. 333–357. [Google Scholar]

- Vásquez-Polo, J.R.; Macías-Vásquez, F. Fraccionamiento químico del carbono en suelos con diferentes usos en el departamento de Magdalena, Colombia. Terra Latinoamericana 2017, 35, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, H.E.; Fuentes, E.J.P.; Acevedo, H.E. Carbono orgánico y propiedades del suelo. Rev. Cienc. Suelo Nutr. Veg. 2008, 8, 68–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez-Polo, J.R.; Macías-Vásquez, F.; Menjivar, J.C. Respiración del suelo según su uso y su relación con algunas formas de carbono en el departamento del Magdalena, Colombia. Biagro 2013, 25, 175–180. [Google Scholar]

- Eswaran, H.; Van den Berg, E.; Reich, P. Organic carbon in soils of the world. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2000, 57, 192–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Inocente, M.A.; Nájera-Luna, J.A.; Escobedo-Bretado, M.A.; Cruz-Cobos, F.; Hernández, F.J.; Vargas-Larreta, B. Carbono retenido en biomasa y suelo en bosques de El Salto, Durango, México. Investig. Cienc. Univ. Autón. Aguascalientes 2020, 28, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, S.; Wang, J.; Shi, Z.; Lu, L.; Guo, W. Dynamics and speciation of organic carbon during decomposition of leaf litter and fine roots in four subtropical plantations of China. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 300, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, I.E. Caracterización química de los suelos del Bosque de Fray Jorge. In Historia Natural del Parque Nacional Bosque Fray Jorge; Squeo, F.A., Gutiérrez, J.R., Hernández, I.R., Eds.; Ediciones Universidad de La Serena: La Serena, Chile, 2004; Volume 15, pp. 265–279. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.; Zheng, F.; Jia, X.; Liu, P.; Dong, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, B. The combined application of organic and inorganic fertilizers increases soil organic matter and improves soil microenvironment in wheat-maize field. J. Soils Sediments 2020, 20, 2395–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Flores, O.; Vela-Correa, G.; Acevedo-Sandoval, O.A.; Valera-Pérez, M.Á. Concentraciones de carbono orgánico en el arbolado y suelos del área natural protegida El Faro en Tlalmanalco, Estado de México. Terra Latinoamericana 2020, 38, 895–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.T.F.; Gibbs, P.; Nortcliff, S.; Swift, R.S. Measurement of the acid neutralizing capacity of agroforestry tree prunings added to tropical soils. J. Agric. Sci. 2000, 134, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoji, S.; Fujiwara, Y. Active aluminum and iron in the humus horizons of andosols from Northeastern Japan: Their forms, properties, and significance in clay weathering. Soil Sci. 1984, 137, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanzyo, M.; Dahlgren, R.; Shoji, S. Chemical characteristics of volcanic ash soils. In Volcanic Ash Soils: Genesis, Properties and Utilization; Shoji, S., Nanzyo, M., Dahlgren, R., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 1993; Volume 21, pp. 145–187. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Rodríguez, A.; Arbelo, C.D.; Notario, J.S.; Mora, J.L.; Guerra, J.A.; Armas, C.M. Contenidos y formas de carbono orgánico en andosoles forestales: Aproximación a su dinámica. Edafología 2004, 11, 67–102. [Google Scholar]

- Grand, S.; Lavkulich, L.M. Depth distribution and predictors of soil organic carbon in southwestern Canada. Soil Sci. 2011, 176, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ramírez, S.; Ramírez, M.; Jaramillo-López, P.; Bautista, F. Contenido de carbono orgánico en el suelo bajo diferentes condiciones forestales: Reserva de la Biósfera Mariposa Monarca, México. Rev. Chapingo Ser. Cienc. For. Ambient. 2013, 19, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Flores, G.; Etchevers-Barra, J. Contenidos de carbono orgánico de suelos someros en pinares y abetales de áreas protegidas de México. Agrociencia 2011, 45, 849–862. [Google Scholar]

- Vela-Correa, G.; López-Blanco, J.; Rodríguez-Gamiño, M.L. Niveles de carbono orgánico total en el suelo de conservación del Distrito Federal, centro de México. Invest. Geogr. Boletín Inst. Geogr. UNAM 2012, 77, 18–30. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-Larreta, B.; Amezcua-Rojas, M.; López-Martínez, J.O.; Cueto-Wong, A.; Cruz-Cobos, F.; Nájera-Luna, J.A.; Aguirre-Calderón, C.G. Estimación de los almacenes de carbono orgánico en el suelo en tres tipos de bosque templado en Durango, México. Bot. Sci. 2023, 101, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrezueta-Unda, S. Efecto de diversos atributos topográficos sobre el carbono orgánico en varios usos del suelo. Cienc. UNEMI 2021, 14, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaguaya-Llamuca, J.L. Determinación de Carbono en el Suelo de Bosque Nativo de Ceja Andina en el Sector Guangra, Parroquia Achupallas, Cantón Alausí, Provincia de Chimborazo. Bachelor’s Thesis, Escuela Superior Politécnica de Chimborazo, Riobamba, Ecuador, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Vásquez-Polo, J.R.; Macías-Vásquez, F.; Menjivar-Flores, J.C. Formas de carbono orgánico en suelos con diferentes usos en el departamento del Magdalena (Colombia). Acta Agron. 2011, 60, 369–379. [Google Scholar]

- Chirilus, G.V.; Lakatos, E.S.; Bălc, R.; Bădărău, A.S.; Cioca, L.I.; David, G.M.; Rpsian, G. Assessment of organic carbon sequestration from Romanian degraded soils: Livada forest plantation case study. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaya, C.A.; Mendoza, M.; Rivera, M.; Páez, R.; Olivares-Martínez, D. Contenido de carbono orgánico y retención de agua en suelos de un bosque de niebla en Michoacán México. Agrociencia 2016, 50, 251–269. [Google Scholar]

- Schiedung, M.; Tregurtha, C.S.; Beare, M.H.; Thomas, S.M.; Don, A. Deep soil flipping increases carbon stocks of New Zealand grasslands. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 2296–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laguna, R.R.; Pérez, J.J.; Calderón, Ó.A.A.; Garza, E.J.T.; Zárate, R.R. Estimación del carbono almacenado en el bosque de pino-encino en la Reserva de la Biósfera el Cielo, Tamaulipas, México. Ra Ximhai 2009, 5, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, J.; del Pino, A.; Salvo, L.; Arrarte, G. Nutrient export and harvest residue decomposition patterns of a Eucalyptus dunnii Maiden plantation in temperate climate of Uruguay. For. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 258, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laclau, P. Biomass and carbon sequestration of ponderosa pine plantations and native cypress forest in northwest Patagonia. For. Ecol. Manag. 2003, 180, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Birdsey, R.A.; Fang, J.; Houghton, R.; Kauppi, P.E.; Kurz, W.A.; Phillips, O.L.; Shvidenko, A.; Lewis, S.L.; Canadell, J.G.; et al. A Large and Persistent Carbon Sink in the World’s Forests. Science 2011, 333, 988–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Garnica, J.G.; Wong-González, J.C.; Paz-Pellat, F. Camas de combustibles forestales y carbono en México. Madera Bosques 2018, 24, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Liu, S.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, W.; He, X.; Su, Y.; Wang, K. Soil carbon and nitrogen accumulation following agricultural abandonment in subtropical karst region. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2018, 130, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAE (Ministerio del Ambiente Ecuador). Estadísticas de Patrimonio Natural. Datos de Bosques, Ecosistémas, Especies, Carbono y Deforestación del Ecuador Continental. Gobierno de Ecuador. 2015. Available online: https://mluisforestal.files.wordpress.com/2016/01/estadisticas-patrimonio-natural-mae.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

| Properties | S1 | S3 | S6 | S9 | S12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BD (Mg m−3) | 0.93 ± 0.23 a | 0.75 ± 0.14 a | 0.93 ± 0.16 a | 0.69 ± 0.08 a | 0.71 ± 0.15 a |

| Clay (%) | 15.67 ± 5.69 ab | 10.44 ± 0.77 ab | 20.83 ± 8.85 a | 7.67 ± 2.03 b | 6.16 ± 0.17 b |

| pH (water 1:2.5) | 5.57 ± 0.29 b | 6.33 ± 0.28 a | 5.84 ± 0.09 ab | 5.58 ± 0.01 b | 5.89 ± 0.06 ab |

| pH (KCl 1:2.5) | 4.24 ± 0.64 a | 5.28 ± 0.49 a | 4.69 ± 0.39 a | 4.58 ± 0.20 a | 4.92 ± 0.07 a |

| ∆pH | −1.33 ± 0.35 a | −1.05 ± 0.22 a | −1.14 ± 0.33 a | −1.00 ± 0.20 a | −0.97 ± 0.08 a |

| Nt (%) | 0.38 ± 0.31 a | 0.53 ± 0.27 a | 0.17 ± 0.21 a | 0.64 ± 0.12 a | 0.70 ± 0.16 a |

| C/N | 11.74 ± 0.33 a | 11.30 ± 0.57 a | 10.26 ± 0.81 a | 12.01 ± 0.69 a | 11.86 ± 3.32 a |

| Alo + 0.5 Feo (%) | 2.79 ± 0.21 a | 2.74 ± 0.23 a | 2.16 ± 0.52 a | 3.41 ± 0.52 a | 3.21 ± 0.60 a |

| CEC cmol+ kg−1 | 17.20 ± 5.80 b | 22.77 ± 6.09 ab | 23.84 ± 2.99 ab | 30.35 ± 3.47 a | 25.21 ± 3.30 ab |

| Fraction | Description | Role in Forest Soils | Ecological Importance | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Labile Carbon (active) | Easily degradable SOC (sugars, recent residues, organic acids) | Immediate energy source for microorganisms; drives nutrient recycling | Sensitive indicator to management and disturbances | [35] |

| Recalcitrant Carbon | Highly decomposed organic matter (humic substances, aromatic compounds) | Accumulates slowly and decomposes very little | Key for carbon sequestration and humus formation | [4,35] |

| Organo-mineral Carbon Fraction | SOC bound to mineral particles (clays, oxides) | Physical/chemical protection against decomposition | Provides long-term carbon stability | [33] |

| Oxidizable Carbon | Chemically estimated by oxidation (Walkley-Black or variants) | Represents accessible labile carbon | Useful for evaluating management impact, disturbances, or ecological recovery | [33,34] |

| Non-oxidizable Carbon | SOC fraction unreactive to strong oxidants (e.g., humins, pyrolitic carbon) | Very stable; persists for decades or centuries | Key for long-term carbon sequestration and stable humic matter formation | [33,34] |

| Total Carbon | Sum of organic and inorganic carbon | Overall measure of soil carbon stock | General indicator of storage potential | [34] |

| Inorganic Carbon | Carbonates (CaCO3, MgCO3); very low in forest | Practically absent in acidic forest soils | No relevant biological function here | [36] |

| Organic Matter | Complete set of organic compounds | Regulates fertility, water, structure, and biodiversity | Basis for ecological functioning of forest soils | [34] |

| Difficult-to-oxidize Carbon | SOC resistant to oxidation or microbial degradation | Accumulates slowly; conserves carbon in soil | Key for durable sequestration and long-term storage | [33,35] |

| Fraction | S1 | S3 | S6 | S9 | S12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC (%) | 6.20 ± 3.36 a | 9.14 ± 4.71 a | 3.06 ± 1.75 a | 9.44 ± 2.93 a | 8.48 ± 2.26 a |

| Cox (%) | 4.46 ± 3.61 a | 6.00 ± 3.24 a | 1.97 ± 2.39 a | 7.18 ± 1.68 a | 8.09 ± 1.83 a |

| Cnox (%) | 1.74 ± 0.70 a | 3.14 ± 2.34 a | 1.10 ± 0.67 a | 2.26 ± 1.28 a | 0.39 ± 0.49 a |

| Cp (%) | 0.83 ± 0.29 ab | 0.83 ± 0.19 ab | 0.49 ± 0.17 b | 1.43 ± 0.26 a | 1.11 ± 0.40 ab |

| Cdox (%) | 3.62 ± 3.34 ab | 5.17 ± 3.06 ab | 1.48 ± 2.27 a | 5.75 ± 1.42 ab | 6.97 ± 1.43 b |

| SOC (Mg C/ha) | 135.22 ± 4.77 ab | 209.82 ± 8.16 bc | 43.25 ± 2.77 a | 280.99 ± 1.15 cd | 328.77 ± 1.51 d |

| COO (%) | 5.36 ± 3.12 a | 8.31 ± 4.53 a | 2.58 ± 1.64 a | 8.01 ± 2.68 a | 7.37 ± 1.88 a |

| REmos (%) | 1.93 ± 0.02 b | 2.01 ± 0.04 b | 5.12 ± 0.07 c | 1.13 ± 0.08 a | 1.18 ± 0.04 a |

| Vegetation Type | Area (ha) | SOC Content (Mg ha−1) | Total Mg C/Area | CO2 (Mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 23.88 | 135.22 | 3229.05 | 11,850.61 |

| S3 | 106.62 | 209.82 | 22,371.01 | 82,101.60 |

| S6 | 31.75 | 43.25 | 1373.19 | 5039.60 |

| S9 | 127.90 | 280.99 | 35,938.62 | 131,894.74 |

| S12 | 1725.40 | 328.77 | 567,259.76 | 2,081,843.31 |

| Total | 2015.55 | 630,171.63 | 2,312,729.86 |

| Vegetation Type | Biomass Carbon (Mg C ha−1) | CO2 (Mg CO2 ha−1) |

|---|---|---|

| S1 | 6.43 | 23.59 |

| S3 | 6.76 | 24.80 |

| S6 | 5.03 | 18.46 |

| S9 | 6.06 | 22.24 |

| S12 | 8.74 | 32.07 |

| Average | 6.60 | 24.23 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Acevedo-Sandoval, O.A.; Romero-Natale, A.; Romo-Gómez, C.; Camacho-López, C.; Leyva-Morales, J.B.; Salas-Martínez, F.; González-Ramírez, C.A. Carbon Fraction Distribution in Forest Soils and Leaf Litter Across Vegetation Types in El Chico National Park, Mexico. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11028. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411028

Acevedo-Sandoval OA, Romero-Natale A, Romo-Gómez C, Camacho-López C, Leyva-Morales JB, Salas-Martínez F, González-Ramírez CA. Carbon Fraction Distribution in Forest Soils and Leaf Litter Across Vegetation Types in El Chico National Park, Mexico. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11028. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411028

Chicago/Turabian StyleAcevedo-Sandoval, Otilio A., Aline Romero-Natale, Claudia Romo-Gómez, César Camacho-López, José Belisario Leyva-Morales, Fernando Salas-Martínez, and César A. González-Ramírez. 2025. "Carbon Fraction Distribution in Forest Soils and Leaf Litter Across Vegetation Types in El Chico National Park, Mexico" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11028. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411028

APA StyleAcevedo-Sandoval, O. A., Romero-Natale, A., Romo-Gómez, C., Camacho-López, C., Leyva-Morales, J. B., Salas-Martínez, F., & González-Ramírez, C. A. (2025). Carbon Fraction Distribution in Forest Soils and Leaf Litter Across Vegetation Types in El Chico National Park, Mexico. Sustainability, 17(24), 11028. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411028