Abstract

Background: Understanding public acceptance of autonomous vehicles (AVs) is essential for cities transitioning toward smart mobility systems. Dubai aims to transform 25% of trips to autonomous mode by year 2030, yet little is known about residents’ readiness. Methods: An online survey (N = 302; 2024/2025) measured awareness, perceived benefits/risks, trust, cybersecurity concerns, and behavioral intention (BI). Constructs were analyzed using descriptive statistics and regression. Results: Cybersecurity concern was the strongest negative predictor of BI, while perceived usefulness (accident reduction) showed a weak, marginal positive effect. Gender, age, and cost effects were not statistically significant. Conclusions: Public acceptance is shaped more by trust, safety perception, and perceived system reliability than by demographics or cost. Policy actions should focus on transparent regulation, cybersecurity audits, and public AV pilots.

1. Introduction

Technological advancements and the demands of fast-paced daily life are driving significant improvements across various forms of transportation. One of these is autonomous mobility, which refers to the ability to travel between two points without a human driver. The adoption of this technology offers numerous benefits to cities and communities, including reduced pollution, congestion, and traffic accidents. Autonomous vehicles (AVs) have the potential to lower greenhouse gas emissions. Studies have shown that fully connected autonomous vehicles (ConFAVs) can reduce delays and improve traffic flow, thereby substantially reducing greenhouse gas emissions [1]. Additionally, AVs are often electric, further reducing their environmental impact. AVs can enhance traffic efficiency by reducing stop-and-go traffic and optimizing vehicle travel. Research found that AVs could improve urban traffic flow, reduce congestion, and increase travel speeds. This improvement in traffic efficiency is crucial for lowering urban congestion [2]. Autonomous vehicles have the potential to reduce traffic accidents by eliminating human error. A report highlighted that driverless cars could reduce traffic fatalities by up to 90% by removing human emotions and errors from driving [3]. This significant reduction in accidents underscores the safety benefits of AVs [4]. The implementation of autonomous vehicles could enhance the use of urban space by ensuring smoother traffic flow and reducing demand for parking spaces and related infrastructure [5,6,7]. The technology could also lead to more efficient land use planning and encourage a shift from personal vehicle ownership to autonomous vehicle sharing, resulting in better land use for buildings and the community [8,9]. Such trends could help stimulate urban economic development by restructuring city layouts and minimizing the waste of valuable urban land [10,11].

Autonomous vehicles also offer an opportunity to advance environmental sustainability, especially in rapidly growing urban environments. This can happen through improvements in traffic flow efficiency and reduced stop-and-go driving. In addition, AVs can decrease fuel consumption, since they are mostly electric, and produce fewer greenhouse gas emissions, contributing to healthier, more environmentally friendly cities [12]. Additionally, AV-based shared mobility can support more efficient land use by reducing parking demand, enabling the repurposing of land for community, public spaces, pedestrian-friendly neighborhoods, and mixed-use developments [13].

From a social sustainability perspective, AVs can enhance mobility equity by improving access for people with mobility limitations, including people with disabilities, seniors, or residents without driving licenses [1]. AVs can provide them safe, reliable, and independent travel options, leading to more inclusive transportation systems, essential for a socially sustainable urban development [3,14]. Therefore, understanding how diverse groups (social and income, physical abilities, age groups) perceive AV benefits and risks is critical for ensuring that AV solutions contribute to socially inclusive and sustainable cities [15,16].

Because of these benefits, cities worldwide have been testing many AV implementation modes, mainly AV shuttles and robotaxis. Integrating autonomous vehicles into public transport systems is not just about technology; it also involves addressing social acceptance, legal frameworks, and potential impacts on urban planning and traffic management. As cities adapt to incorporate these vehicles, there is a need to understand the implications of these technologies for public perception and the future of urban mobility [13]. In Dubai (our case study city), a comprehensive strategy was released in 2016, targeting 25% of trips in AV mode by the year 2030 across the different modes of transport: metro, shuttle, taxi, ferry, and private vehicles. To achieve this target, the city is working on multiple enablers, including but not limited to legislation, certification, innovative business partnerships, and public acceptance [17,18,19]. The latter part is the focus of this research paper.

2. Research Gaps and Objectives

Identifying research gaps in evaluating public perceptions of autonomous vehicle (AV) deployment is essential for guiding future studies and policymaking. These gaps were examined in Dubai and are relevant to the broader MENA region. Key gaps include:

- Cultural and Social Factors: Limited research exists on how Dubai’s cultural and social composition influences AV perceptions, despite its importance for localized deployment strategies [20].

- Longitudinal Evidence: Most studies are cross-sectional; longitudinal studies are needed to capture how perceptions evolve as AV technologies and infrastructure mature [21].

- Diverse Demographics: There is limited evidence on how different age groups, genders, and socio-economic statuses perceive AVs differently [20].

- Public Awareness Campaigns: The effectiveness of awareness and education campaigns in shaping AV acceptance remains underexplored [12].

- Integration with Existing Transport Systems: More research is needed on how AVs can be integrated with current public transport systems in Dubai and how this affects user acceptance.

- Safety and Cybersecurity: Detailed studies on user-specific concerns, particularly cybersecurity and trust in data protection, are lacking [12].

- Economic Implications: Limited research addresses the role of financial considerations—service costs, job displacement, affordability—in shaping AV acceptance [22].

- Environmental Impact Awareness: Additional research is needed on how awareness of benefits influences perceptions and acceptance of AVs [12].

Although behavioral models such as TAM, UTAUT, and DOI have been widely applied to study AV adoption, most existing studies have been conducted in post-deployment or monocultural settings where users already possess some familiarity with AV technologies. These frameworks are less suitable for pre-deployment contexts such as Dubai, where cultural variation is high, policy evolves rapidly, and user experience with AVs is minimal.

Dubai represents a unique environment due to its ambitious AV policy targets (25% autonomous trips by 2030), its highly multicultural population (approximately 85% expatriates), and ongoing regulation and infrastructure development across transport modes. This context enables examination of how Cultural Trust (CT) and Policy Readiness (PR) interact with traditional TAM constructs—Perceived Usefulness (PU) and Ease of Use (PEOU)—in shaping behavioral intention.

The following objectives guide this study:

- Measure levels of AV awareness and behavioral intention among Dubai residents.

- Test a TAM integrating PU, PEOU, CT, and PR.

- Identify key barriers and demographic factors—especially cybersecurity, age, and expatriate status—that influence AV acceptance.

- Provide policy and design recommendations to support public readiness in multicultural smart cities.

These objectives explain the study’s theoretical and policy contributions. This research forms part of a larger mixed-methods research that will later employ validated multi-item scales and structural equation modeling (SEM). While this exploratory phase uses single-item indicators, future phases will extend the measurement model to evaluate the complete TAM framework in the MENA context.

This study examines public perceptions and challenges associated with AV deployment in Dubai and provides insights to support successful AV integration. It evaluates user perceptions, identifies key acceptance drivers, and examines demographic variations and the effects of awareness drives. Dubai’s diverse expatriate population, rapid economic growth, and investment in innovation provide a distinctive context for studying AV acceptance. Findings from Dubai can inform AV adoption strategies across the Gulf, the Middle East, and comparable global cities.

The study also contributes to global discussions on AV adoption by highlighting the importance of cultural and contextual influences in shaping acceptance. It extends the literature by (1) incorporating cultural and policy dimensions into TAM for the MENA region, (2) providing empirical evidence from a pre-deployment context, and (3) offering guidance for policymakers and planners on enhancing public trust and readiness for AV services.

3. Problem Statement

Despite increasing interest in AV technologies, several research gaps remain:

- Long-Term Impacts: More longitudinal research is needed to understand the long-term implications of AV deployment on traffic, urban planning, and environmental sustainability.

- Cultural Contexts: Comparative studies across different cultural and regulatory environments are limited.

- Behavioral Responses: Additional research is needed on demographic differences in behavioral responses to AVs [23].

- Ethical Frameworks: Ethical frameworks addressing AV decision-making in critical scenarios are underdeveloped.

- Localized Studies: Research tailored to Dubai’s unique socio-economic and cultural context is limited.

- Pilot Programs: Additional pilot programs are needed to test and refine AV technologies in Dubai’s real-world environment.

Addressing these gaps will help Dubai design and implement AV systems that improve transportation efficiency, public trust, and safety.

4. Research Overview

This study evaluates Dubai residents’ perceptions and acceptance of autonomous vehicle (AV) deployment. By identifying key factors influencing public attitudes towards AVs. To ensure a logical progression from understanding the global context to identifying key factors and applying these insights (the case of Dubai), the research aims to respond to the following questions:

- What is the current state of AV technology worldwide, and what lessons can be learned from past experiences? What are the critical factors determining public acceptance of AVs?

- How can insights from global AV technology and public acceptance be applied to enhance AV system planning, facility design, and implementation for future deployment in Dubai?

The approaches followed to answer these questions are divided into two main phases:

Phase 1: The Literature Review, which focuses on analyzing the current state of Autonomous Vehicle (AV) technology worldwide, including the implementation of primary AV programs. This phase involves reviewing previous research on AV and examining the findings and limitations of existing studies. Insights from this phase include identifying gaps in the literature, developing theoretical frameworks, gaining methodological insights, identifying trends and patterns, understanding public perception, assessing technological impact, acknowledging cultural differences, and identifying future research directions.

Phase 2: The Community Survey aims to evaluate public knowledge about AV, assess perceptions of safety, benefits, and negative impacts, gather opinions on the future of AV, and understand demographic differences in perspectives. Insights from this survey help understand public opinion and concerns, gauge community readiness, inform policy decisions, tailor solutions based on community feedback, promote public engagement, gain cultural insights, and establish benchmarking standards.

This structured approach ensures a comprehensive understanding of public acceptance and facilitates the development of informed policies and regulations for integrating AVs into urban mobility systems in the UAE.

5. Literature Review

The global research interest in autonomous vehicle (AV) adoption has increasingly shifted toward public perception and acceptance, recognizing that technological readiness alone is insufficient for successful deployment. Prior research highlights several acceptance indicators, including safety, trust in technology, regulatory frameworks, affordability, and ethical concerns [19,20]. Cross-national studies also reveal cultural and contextual variations in AV acceptance, suggesting that the transferability of findings across regions requires caution.

The rapid advancement of autonomous vehicle (AV) technology has urged research into investigating the factors influencing public acceptance, adoption, and trust in this new technology. Understanding these factors is essential, as not all AV benefits can be realized if users are unwilling to adopt the technology. Recent studies have integrated various behavioral and technological frameworks, including the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT), and Diffusion of Innovation (DOI), to examine perceptions, attitudes, and perceived risks associated with AVs. This literature review synthesizes key findings from recent empirical and conceptual studies across diverse cultural and geographical contexts, highlighting the psychological, social, and demographic determinants that shape user acceptance and trust. Together, these insights provide a comprehensive foundation for policymakers, designers, and researchers to develop strategies that promote equitable and widespread adoption of autonomous vehicles. A summary of the literature review on the acceptance of autonomous vehicles is shown in Table 1:

Table 1.

Summary of Literature on Autonomous Vehicle (AV) Acceptance.

5.1. Cross-Disciplinary Enablers of AV Acceptance

Beyond behavioral intention models, AV acceptance is strongly shaped by infrastructure, communication reliability, and human–technology interaction. Several recent studies illustrate this broader socio-technical landscape:

- Interpretive Structural Model for EV Charging Station Location (India)—highlights how the accessibility of charging and road infrastructure influences perceived convenience and trust in emerging transport technologies [29].

- Empowering Sustainable Public Transportation: Electric Bus Revolution—emphasizes how policy support and infrastructure readiness drive user acceptance in public mobility transitions [30].

- Intersection Fog-Based Distributed Routing for V2V Communication and Bus-Trajectory-Based VANET Routing—demonstrate how reliable, low-latency communication systems strengthen perceived safety and reduce cybersecurity concerns [31].

- Consensus Reaching for Product Design Combining Trust and Empathy Relationships—shows that participatory co-design enhances public trust and emotional engagement with technology [2,11].

- Technology-Organization-Environment (TOE) Framework for New Energy Vehicles —identifies policy and institutional readiness as essential contextual moderators of technological adoption [32].

- Radar Data Representations in Autonomous Driving—underlines that transparent sensor performance affects user perception of safety and control [33].

- The integration of these cross-disciplinary findings strengthens the theoretical foundation for the extended TAM applied in this research, acknowledging that user acceptance depends not only on individual attitudes but on the reliability of underlying socio-technical systems.

5.2. Theoretical Framework: Extending TAM for Dubai

Sustainable deployment of AV technology needs a strong governance structure, regulations and long-term policy readiness. These ensure safety, data protection, and ethical operation to gain public trust and sustainable mobility planning [3]. Cybersecurity standards and transparent safety audit can help integrate AVs into broader sustainable development strategies [18,33]. Understanding residents’ policy expectations are essential to designing rational long-term planning pathways.

To better understand the factors affecting public acceptance, the study extended the TAM to a multicultural pre-deployment context. TAM suggests that (PU) and (PEOU) shape users’ (ATT) and (BI) to adopt technology.

Two additional constructs were added to the model for Dubai, as shown in Table 2:

- Cultural Trust (CT): rooted in UTAUT’s Social Influence and DOI’s Trust and Observability dimensions, CT captures variations in perceived reliability and social endorsement across Emirati and expatriate groups.

- Policy Readiness (PR): derived from the Technology-Organization-Environment (TOE) framework, PR reflects users’ confidence in government preparedness, regulatory clarity, and institutional oversight.

Table 2.

Operationalization table.

Table 2.

Operationalization table.

| Construct | Conceptual Basis | Operational Indicator (Current Study) | Intended Multi-Item Scale (Future Work) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PU | TAM | “AVs will reduce accidents/congestion” | [4,34] |

| PEOU | TAM | “AVs will be reliable/easy to use” | [4] |

| CT | UTAUT/DOI | “Trust in government/technology providers” | [9] multi-item trust scale |

| PR | TOE Framework | “Dubai is ready for AV deployment.” | [30] |

| Cyber Risk | Information Systems Security | “Concern about hacking” | Multi-item privacy/security scale |

| BI | TAM | “I would use AVs in the future” | [35] |

Note: In this phase of the research, constructs Cultural Trust (CT) and Policy Readiness (PR) were measured using single-item exploratory indicators. These do not represent validated scales. Therefore, theoretical interpretations involving CT/PR are exploratory and will be expanded in the next phase using multi-item validated scales.

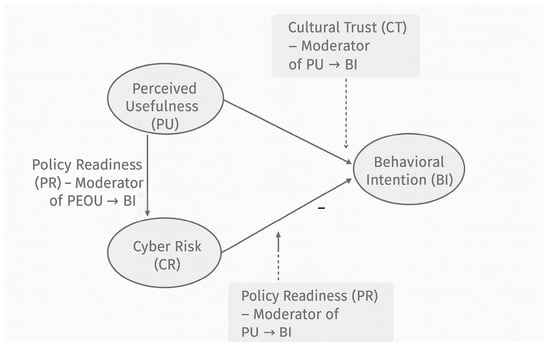

The extended model hypothesizes that:

H1.

Perceived Usefulness (PU) positively influences Behavioral Intention (BI).

H2.

Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) positively influences Behavioral Intention (BI).

H3.

Cultural Trust (CT) moderates the PU → BI relationship, such that higher CT strengthens the likelihood of adoption.

H4.

Policy Readiness (PR) moderates the PEOU → BI relationship such that higher perceived readiness reinforces adoption.

H5.

Cyber Risk negatively influences Behavioral Intention.

Figure 1 presents the adapted Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) extended for Dubai. The model integrates Cultural Trust (CT), Policy Readiness (PR), and Cyber Risk (CR) alongside the original TAM constructs (PU, PEOU). CT and PR are treated as exploratory single-item proxies in this phase, and CR represents perceived cybersecurity threats. The figure aligns with the operationalization table, ensuring complete correspondence between conceptual and empirical elements.

Figure 1.

The adapted TAM framework. Note: All constructs were assessed on five-point Likert scales; each will be expanded into 3–5 items in subsequent model validation.

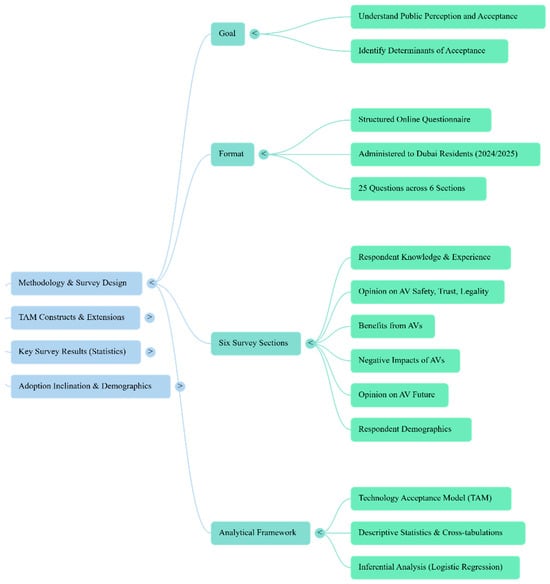

6. Methodology: Survey Overview

The structured online questionnaire was administered to Dubai residents in 2024/2025. The survey captured respondents’ knowledge of AVs, perceptions of safety and trust, perceived benefits and risks, future expectations, and demographic characteristics. Key questions were mapped to the TAM (Technology Acceptance Model), a statistical framework for analyzing how users come to accept and use a technology [36].

The survey combines the TAM modules with the ones aiming to answer the research key questions, which are:

- Behavioral Intention (BI): willingness to ride in, purchase, or support AV deployment.

- Cultural Trust (CT): differences in trust levels between expatriates and residents.

- Policy Readiness (PR): perceived adequacy of Dubai’s legal and institutional frameworks.

Data analysis proceeded in two stages:

- Descriptive Statistics and Cross-tabulations: Initial summaries explored demographic differences in perceptions (e.g., gender, age, education).

- Inferential Analysis: Given the exploratory nature of the study, an exploratory modeling approach was applied to observe general effect directions and the relative strength of links between variables. For example, the model assessed whether younger age, higher education, or greater trust predicted willingness to adopt AVs. Regression coefficients (β) and significance levels (p-values) were reported.

6.1. Survey Design

A structured online questionnaire was developed to measure AV awareness, perceptions, and behavioral intentions. The survey consisted of 25 items across six sections: demographics, awareness, perceived benefits, perceived risks, extended TAM constructs, and behavioral intention, as shown in Figure 2

Figure 2.

Methodology overview and Survey design.

6.2. Survey Sampling, Measures, and Recruitment

The survey was distributed through Ajman University, Dubai RTA communication channels, and professional LinkedIn groups between December 2024 and February 2025. Approximately 413 invitations were issued, yielding 302 valid responses (73% effective rate). Participation was voluntary with no financial incentive. The survey was administered in English. Inclusion criteria required participants to be 18 years or older and current residents of Dubai. While the sample includes diverse nationalities, the distribution does not perfectly match the Dubai population structure.

Appendix A provides a complete item-to-construct mapping and question text for replication purposes.

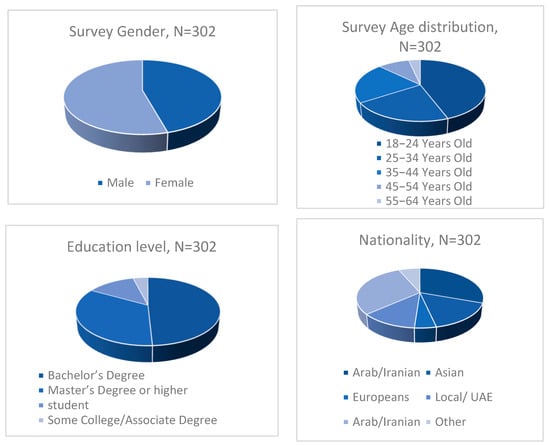

The survey reflected a diverse demographic profile. The following Figure 3 shows the Demographic Distribution displaying N and % for gender, age, education, and nationality.

Figure 3.

Survey demographic distribution.

This analytical framework enhances rigor by moving beyond descriptive patterns to testing statistically significant predictors of AV acceptance. Each construct was measured using Likert-type items. Given the exploratory nature of the study, several constructs were represented by single items. Preliminary reliability checks (Cronbach’s α for multi-item constructs) were conducted, and missing data were handled through listwise deletion.

6.2.1. Statistics: Benefits and Disbenefits of AVs

The survey feedback indicates that most respondents (89%) believe autonomous vehicles (AVs) will help reduce traffic congestion and accidents. There is strong agreement (93%) that AVs will benefit people without a driver’s license and those with disabilities. However, opinions are divided on whether AVs will lead to job losses, with a tendency towards agreement (76%). Despite the potential benefits, significant concerns (85%) remain about AV safety, particularly the risk of hacking that could compromise it.

6.2.2. Statistics: Demographics

The survey demographics reveal a predominantly male respondent base (77%), with most being employed (52%), followed by students (24%), self-employed individuals (14%), and retirees (10%). A significant portion holds higher education degrees: 31% have a bachelor’s degree, 29% a master’s degree, and 14% a doctorate. Most respondents are from Asian and Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, with notable representation from other regions, including Europeans and locals. Most respondents do not have a physical disability; most are under 35, with 32% under 25 and 29% between 25 and 34.

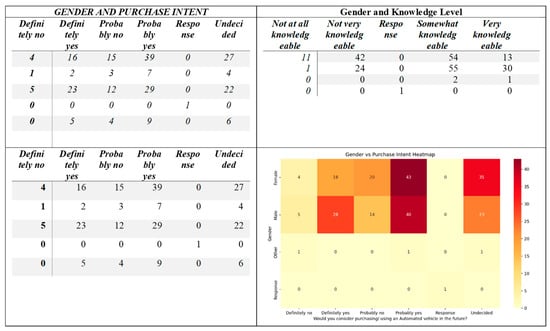

- Respondent’s knowledge and experience in AVs

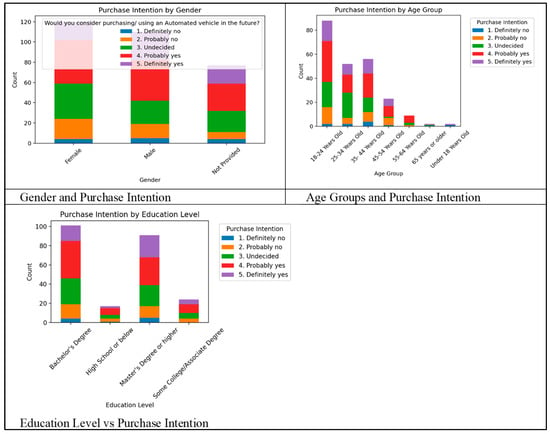

The survey feedback reveals that most respondents are neutral about whether autonomous vehicles can match human driving skills, with a slight tendency towards agreement. Awareness of autonomous vehicles is high, and those familiar with them generally rate their experience positively. Additionally, a significant portion of respondents are likely to consider purchasing an autonomous vehicle in the future, Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Gender and Knowledge Level/Gender and Purchase Intent/Education Level and Purchase Intent. Source: Author’s survey, 2024/2025. Note: Bars represent absolute frequencies. Percentages (relative to N = 302) are shown on labels for more precise comparison.

- b

- Cross-tabulation analysis

- c

- Knowledge Levels

Males tend to report higher levels of knowledge about autonomous vehicles than females do. Both genders show a similar positive inclination towards purchasing or using autonomous vehicles in the future, with “Probably yes” being the most common response. People with bachelor’s and master’s degrees show more interest in autonomous vehicles. A relatively high number of “Undecided” responses across all demographic groups suggests uncertainty about autonomous vehicle adoption. Female respondents show a strong preference towards “Probably yes” with 43 responses, while males show a similar preference with 40 responses, but have more “Definitely yes” responses (28) compared to females (18). The 18–24 age group shows the highest interest, with 34 “Probably yes” responses, while the 25–34 and 35–44 age groups show moderate interest. Older age groups (55+) have fewer responses overall. Bachelor’s degree holders show the highest interest, with 39 “Probably yes” responses. Those with master’s degrees or higher show more polarized opinions, with higher numbers in both positive and negative responses. People with some college education or high school education show a generally positive inclination, but with fewer total responses.

Regarding awareness and experience, only 29.3% of respondents have been in an autonomous vehicle. Approximately 56.7% of respondents are positively inclined (combining “Definitely yes” and “Probably yes”) toward using autonomous vehicles in the future. The graph shows the distribution of self-reported knowledge about autonomous vehicles, indicating varying levels of familiarity with the technology.

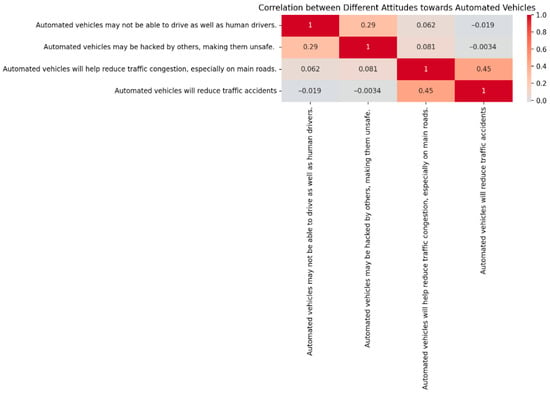

In terms of attitudes and concerns, the visualization illustrates the distribution of responses to key concerns about autonomous vehicles, including safety in comparison to human drivers, potential security issues (such as hacking), traffic congestion reduction, and the potential for accident reduction, Figure 5:

Figure 5.

Attitudes towards autonomous vehicles correlation. Source: Author’s survey, 2024/2025. Note: Bars represent absolute frequencies. Percentages (relative to N = 302) are shown on labels for more precise comparison.

The heatmap illustrates the correlations of attitudes towards autonomous vehicles, highlighting relationships among various concerns and benefits. There is high awareness but low direct experience with autonomous vehicles. Despite limited experience, there is significant openness to future adoption. Safety and security concerns exist alongside recognition of potential benefits. There are mixed feelings about the impact of technology on traffic and safety.

6.2.3. Statistics: Gender/Age Groups and Purchase Intention

The findings reveal slight differences in purchase intention across gender. Among females, there is a slight increase in the “Probably yes” and “Definitely yes” categories, indicating a moderate interest in purchasing or using autonomous vehicles in the future. Males show a little more diverse distribution of responses, with significant counts in both “Probably no” and “Probably yes,” suggesting a more divided opinion on AV adoption. The “Undecided” category also has notable representation across genders, indicating that many respondents remain uncertain about AVs. Additionally, although underrepresented, the “Not Provided” category primarily shows interest in the “Probably yes” category, indicating a positive inclination despite the absence of a specified gender. Overall, this analysis suggests that gender does not have a substantial impact on the intentions toward AV adoption.

6.2.4. Statistics: Age Groups and Purchase Intention

When examining purchase intention by age group, younger respondents, mainly those aged 18–24 and 25–34, show a higher interest in autonomous vehicles, with many falling into the “Probably yes” and “Definitely yes” categories. This trend suggests a greater openness to AV technology among younger generations. In contrast, older age groups, particularly those aged 55 and above, are less likely to purchase or use autonomous vehicles. The responses from these older age groups tend more toward “Probably no” or “Definitely no,” reflecting more skepticism or resistance to AV adoption. The undecided category spans various age groups, indicating that while younger respondents are generally more open to AVs, a segment in all age groups remains undecided. This age-based trend suggests a generational divide in attitudes toward AV technology, with younger people showing greater interest in adopting it.

Although descriptive frequencies suggested slight gender and age variation, regression analysis indicated that neither gender nor age significantly predicted Behavioral Intention (p > 0.10). Therefore, no statistically reliable differences exist across gender or age groups.

6.2.5. Education Level vs. Purchase Intention

The data on education level and purchase intention show interesting patterns. Respondents with a bachelor’s degree or higher and those with a high school education or lower show a balanced distribution across the categories, with a notable number expressing a positive purchase intention (either “Probably yes” or “Definitely yes”). Those with a master’s degree or higher show a slight inclination towards “Probably yes,” suggesting moderate interest in AVs among higher-educated individuals, though there are also responses indicating caution or indecision (“Undecided” and “Probably no”). Respondents with some college or associate degrees appear to have varied responses, indicating a range of opinions within this group. This distribution suggests that while education level may influence views on AVs, it does not create a robust and definitive trend. Higher education appears to be associated with a slight preference for AVs, although uncertainty and caution persist across all educational levels, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Gender, Age Groups, Education Level vs. Purchase Intention summary.

Because several constructs (CT, PR, CR) were measured using single-item exploratory indicators, internal consistency reliability metrics (Cronbach’s α, composite reliability, AVE, discriminant validity) are not applicable. Future phases will adopt validated 3–5 item scales and a full measurement model (EFA → CFA). For transparency, the present analysis is treated as exploratory and avoids confirmatory claims about CT and PR.

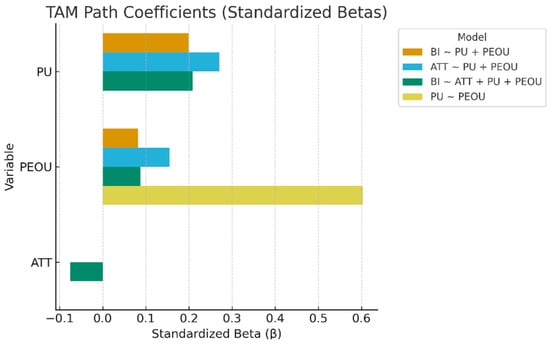

6.3. Survey Results: Inferential Analysis-TAM

To explore potential relationships between the adapted TAM constructs and Behavioral Intention (BI), an exploratory modeling procedure was used. The objective of this stage was to identify effect patterns in the data. The values presented in Table 3 were interpreted as directional and descriptive enhancements to the TAM interpretation.

Table 3.

Exploratory Effect Patterns Associated with Behavioral Intention (BI) (Dubai Survey, 2024/2025).

The model explains approximately 33% of the variance (R2 = 0.33) in behavioral intention, indicating a moderate explanatory power consistent with comparable TAM-based AV studies in pre-deployment contexts.

6.3.1. Model Diagnostics and Moderation

Multicollinearity diagnostics indicated acceptable variance inflation factors (VIF < 2.5). Standardized coefficients and 95% confidence intervals were computed to enable comparison across predictors. The relationship between Accident Reduction and Behavioral Intention (p = 0.07) was treated as suggestive rather than conclusive.

6.3.2. TAM Interpretation and Findings

The regression analysis based on the Dubai public survey explains 33% of the variance in behavioral intention to adopt autonomous vehicles (AVs), demonstrating exploratory directional patterns consistent with the extended (TAM). Among the tested factors, cybersecurity concern showed the most substantial negative effect (β = −0.24, p < 0.001), indicating that fear of hacking significantly reduces willingness to adopt AVs. Conversely, the perceived safety benefits, particularly accident reduction (β = 0.13, p < 0.07) and congestion reduction (β = 0.11, p = 0.12), were positive predictors of acceptance, though only slightly significant.

Demographic variables such as gender and age had weak, non-significant effects, suggesting that attitudes toward safety and trust outweigh demographic influences in shaping adoption intention. The results highlight that public acceptance in Dubai depends primarily on perceived trust, safety assurance, and transparent regulation, rather than personal characteristics or cost perceptions.

Overall, the findings validate the TAM framework adapted for the MENA context, emphasizing the importance of building institutional trust through cybersecurity measures, awareness campaigns, and visible government commitment to safe AV deployment, as summarized in Figure 7 Below:

Figure 7.

TAM coefficients. Source: Author’s survey, 2024/2025. Note: Coefficients represent standardized beta values. Group sample size N = 302.

6.3.3. Qualitative Insights

A total of 74 responses generated 123 coded segments. Percentages refer to the share of coded segments.

Three themes emerged:

- Cybersecurity and data privacy concerns (42%)

- Safety concerns in mixed traffic (33%)

- Need for public awareness and transparent pilot projects (25%)

These qualitative insights support the quantitative finding that Cyber Risk is the strongest determinant of behavioral intention. Appendix B reports the percentage of respondents whose primary theme matched each category. These metrics are now aligned and distinguished explicitly

7. Discussion

The benefits of AV deployment can only be recognized when users accept and trust the technology after experiencing its safety, environmental, and social advantages. The study’s findings—especially related to cybersecurity, safety, and cultural trust—focus on how behavioral perceptions can shape the adoption of AVs. Which aligns with global sustainability research emphasizing that technological readiness alone is insufficient to achieve environmentally friendly and socially just mobility transformations [37]. In the context of Dubai’s smart-city agenda, strengthening public awareness, transparency, and policy coherence will be vital for leveraging AVs to support long-term sustainable urban development [18,38].

The findings highlighted a pattern of acceptance in Dubai. Traditional TAM predictors (PU and PEOU) contribute modestly to behavioral intention, suggesting that early-stage expectations of usefulness and ease of use are present but not dominant. Instead, cybersecurity concern emerges as the primary barrier, aligning with global evidence that safety and privacy risks shape trust in autonomous vehicle systems.

Cultural Trust plays a secondary but meaningful role, indicating that Dubai’s diverse population evaluates emerging technologies through institutional confidence. Although Policy Readiness showed limited direct influence, qualitative responses suggest that residents expect regulatory clarity and visible government involvement, which may strengthen acceptance as deployment advances.

Demographic variables were largely insignificant, reflecting the city’s highly heterogeneous population and its relatively uniform exposure to smart-city initiatives. The moderate explanatory power (R2 ≈ 0.33) suggests that behavioral intention is influenced by both perceptual and contextual factors, with technical reliability and security concerns outweighing traditional usability perceptions.

Descriptive Analysis: The survey revealed high awareness but limited direct experience with AVs (only ~29% reported having ridden in one). A high percentage (≈57%) expressed positive behavioral intentions (combining “Definitely Yes” and “Probably Yes”), while a significant minority remained undecided. No reliable directional differences were observed across gender or age groups, consistent with previous early-phase AV perception studies. Because demographic proportions in this sample differ from Dubai’s census composition, results should be generalized cautiously. Future work will apply post-stratification weighting to approximate the population structure (gender, age, nationality). TAM analysis: Enhancing public understanding of ease of use and the tangible benefits of autonomous vehicles can strengthen acceptance and future adoption. The results, supported by the TAM framework modified for the MENA region, show the significance of fostering institutional trust through cybersecurity precautions, public awareness efforts, and clear government procedures to assure public safety.

8. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Research

Several limitations were detected; the online survey may over-represent younger, more technologically literate respondents, potentially inflating positive behavioral intentions. As a single-city study, findings cannot be directly generalized to other Gulf or international contexts. Data are self-reported and perception-based, which may introduce social desirability bias. Despite these limitations, the study provides valid exploratory evidence for hypothesis generation in pre-deployment contexts. The level of technological readiness significantly influences public acceptance of autonomous vehicles (AVs). Residents who are more familiar with and confident in AV technology are more likely to embrace its deployment. Safety concerns remain a significant barrier to acceptance, and the public’s perception of AV safety is crucial: higher perceived safety correlates with greater acceptance. Acceptance levels vary across different demographic groups, with younger, tech-savvy individuals showing higher acceptance rates than older residents. Awareness and understanding of AV technology positively affect acceptance, and effective public awareness campaigns can help alleviate fears and misconceptions about AVs. Clear and supportive regulatory frameworks enhance public confidence in AV technology, underscoring the need for comprehensive regulations that address safety, liability, and ethical concerns.

In addition, the study provides novel insights into AV acceptance in Dubai by grounding findings in the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and extending it with MENA-specific variables.

The analysis confirms TAM’s relevance in explaining AV acceptance through Perceived Usefulness, Ease of Use, Cultural Trust, and Policy Readiness, reinforcing the need for transparent governance and legal frameworks to build legitimacy.

While the study advances theory and practice, it has limitations, including a relatively small sample size and reliance on self-reported perceptions. Future research should expand surveys to a larger, more representative sample (500+ respondents) and employ structural equation modeling (SEM) to test complex TAM pathways.

While expert perspectives were planned for a subsequent phase, this paper focused on quantitative analysis, with some qualitative analysis to isolate key determinants of public acceptance. Future work will incorporate more focused qualitative expert insights to triangulate and validate the survey findings. Future research will extend these measures into multi-item latent constructs validated through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation modeling (SEM).

It is essential to conduct longitudinal studies to track changes in public perceptions and acceptance of autonomous vehicles (AVs) over time, as technology and infrastructure evolve. To help tailor deployment strategies to local contexts, an investigation is needed on how cultural and social factors specific to Dubai and the broader MENA region influence user perceptions of AVs. Exploring the perceptions of specific demographic groups, such as age brackets, genders, and socio-economic statuses, will provide a deeper understanding of how they perceive AVs differently. Evaluating the effectiveness of public awareness and education campaigns in altering perceptions and promoting acceptance of AVs is essential. Researching the integration of AVs with existing public transport systems in Dubai and their impact on user perceptions and acceptance will be beneficial. Conducting detailed studies on specific safety and security concerns of users, including cybersecurity threats, and how these concerns impact acceptance, is essential. Examining the financial implications of AV deployment, including job displacement and the cost of AV services, and their impact on public perception and acceptance, will provide valuable insights. Investigating how awareness of the environmental benefits of AVs, such as reduced emissions, affects user perceptions and acceptance is also crucial.

This paper contributes by (a) extending the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) through the incorporation of Cultural Trust and Policy Readiness in a pre-deployment multicultural context, (b) empirically identifying cybersecurity concern as the dominant negative predictor of behavioral intention, and (c) demonstrating that policy readiness acts primarily as a contextual moderator influencing perceived trust and safety.

The model explains roughly one-third of the variance in behavioral intention (R2 ≈ 0.33), indicating that perceptual and contextual factors—rather than cost or demographics—drive AV acceptance in early-stage smart-city settings.

Future research directions include:

- Longitudinal panel surveys to monitor changing public perceptions during pilot rollout phases;

- Mixed-methods expert interviews to triangulate quantitative findings; comparative cross-city studies across the MENA region to assess cultural generalizability;

- Linking perceived-risk indicators with real-world V2X and edge-network resilience metrics;

- Combining stated-preference and revealed-preference approaches in future pilots will enrich both the theoretical and practical understanding of autonomous-vehicle readiness.

- Apply stratified sampling and a complete multi-item SEM-based measurement.

- Extend the analysis to cover extended measures validated through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation modeling (SEM);

- Using single-item indicators (CT, PR, CR) can limit reliability assessment. Future phases will use validated multi-item scales and SEM-based measurement models.

Overall, this study provides one of the earliest data-driven analyses of autonomous vehicles adoption in Dubai, showing distinct connections between cultural trust, perceived safety, technological awareness, and legislative support in influencing behavioral intention. Due to sampling limitations and reliance on self-reported impressions, the results remain exploratory, even as they improve theory and practice by expanding TAM to include MENA-specific dimensions. However, the findings offer a strong empirical basis for further, more thorough research, especially cross-city comparison studies, longitudinal analysis, and multi-item SEM models that represent the changing reality of AV deployment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.H.; Methodology, D.H. and Q.H.; Formal analysis, I.Z.; Investigation, D.H. and Q.H.; Resources, D.H.; Data curation, D.H. and Q.H.; Writing—original draft, D.H.; Writing—review & editing, D.H. and I.Z.; Supervision, I.Z.; Project administration, I.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Ajman University grant number GR04.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Ajman University (protocol code A-F-H-30-Nov and date of approval 5 December 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

AI tools were used only to support document organization and literature/data management. All analysis, interpretation, and conclusions were made by the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Survey Questions

Survey: Public Perceptions of Autonomous Vehicles (AVs) in Dubai

- Section A—Knowledge and Experience

- Q1. Have you heard about autonomous vehicles (AVs) before?

Scale: Yes/No

- Q2. How would you rate your knowledge about autonomous vehicles?

Scale: 1 = Not knowledgeable … 5 = Very knowledgeable

- Q3. Have you ever been in an autonomous/autonomous vehicle?

Scale: Yes/No

- Q4. If Yes to Q3, please rate your experience. (If No, select NA.)

Scale: 1 = Very negative … 5 = Very positive/NA

- Q5. Would you consider purchasing/using an autonomous vehicle in the future?

Scale: 1 = Definitely no … 5 = Definitely yes

- Section B—Attitudes and Perceived Risks (Agreement)

Scale for Q6–Q11 and Q20–Q21: 1 = Strongly disagree … 5 = Strongly agree

- Q6. Autonomous vehicles may not be able to drive as well as human drivers.

- Q7. Autonomous transportation may be rejected because there is no proof of their safety systems when employed on main roads and highways.

- Q8. The implementation of autonomous vehicles will cause many job closures.

- Q9. Autonomous vehicles may be hacked by others, making them unsafe.

- Q10. Public transport cost will increase when autonomous transport is applied.

- Q11. Legal problems will arise when autonomous vehicles are implemented.

- Section C—Perceived Benefits (Agreement)

Same scale: 1 = Strongly disagree … 5 = Strongly agree

- Q12. Autonomous vehicles will help reduce traffic congestion, especially on main roads.

- Q13. Autonomous vehicles will help people with no driving licenses.

- Q14. Introducing autonomous vehicles will increase efficiency/comfort for long distances.

- Q15. Using an autonomous mode of transportation is a solution for people with determination (people with disabilities).

- Q16. Autonomous vehicles will reduce traffic accidents.

- Section D—Adoption Drivers (Importance)

Scale for Q17–Q19: 1 = Not important … 5 = Very important

- Q17. Safety record and reliability.

- Q18. Cost of the vehicle.

- Q19. Government regulations and policies supporting autonomous vehicles.

- Section E—Policy and Operations (Agreement)

Scale: 1 = Strongly disagree … 5 = Strongly agree

- Q20. Autonomous vehicles should operate in special lanes to avoid congestion and accidents.

- Q21. Human operators still need to play a role in monitoring autonomous vehicle systems.

- Section F—Open-Ended/Preferences

- Q22. How do you envision the future of transportation with autonomous vehicles in Dubai? Which mode will we see first (bus, private cars, taxis, ferry, etc.)? Should AVs use dedicated lanes or be mixed with traffic? (Open response)

- Q23. In your opinion, what are the main barriers to the widespread adoption of autonomous vehicles? (Open response)

- Section G—Demographics

- Q24. Please indicate the following:

- (a)

- Gender: Male/Female/Prefer not to say

- (b)

- Age: 18–24/25–34/35–44/45–54/55–64/65+

- (c)

- Nationality (UAE MoFA 2016 categories): Emirati/GCC/Arab–Iranian/Asian/European/African/Other

- (d)

- Education level: High School or below/Some College–Associate/Bachelor’s Degree/Master’s Degree or higher

- (e)

- Occupation: Student/Employed/Self-employed/Retired/Other

- (f)

- Physical disability: Yes/No/Prefer not to say

- Q25. (Optional) Email address for follow-up on results or pilot participation

Appendix B. Thematic Coding of Open-Ended Responses

Two open-ended survey questions were analyzed:

“How do you envision the future of transportation with autonomous vehicles?”

“In your opinion, what are the main barriers to the widespread adoption of autonomous vehicles?”

A total of 74 meaningful open-ended responses were coded using inductive thematic analysis.

Coding was conducted independently by two reviewers; inter-rater agreement was κ = 0.82, indicating high reliability. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion, Table A1.

Table A1.

Thematic analysis.

Table A1.

Thematic analysis.

| Theme | Description | Frequency (n) | % of Responses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost/Infrastructure Readiness | Concerns about the cost of AV deployment, need for dedicated lanes, infrastructure gaps, operational costs. | 39 | 53% |

| Technology Reliability and Performance | Doubts about system reliability, AI performance, error rates, and safety in mixed traffic. | 31 | 42% |

| Awareness/Public Understanding | Need for public education, familiarity, trust-building, and trial exposure. | 19 | 26% |

| Legal and Regulatory Readiness | Concerns about laws, liability, accident responsibility, and insurance frameworks. | 18 | 24% |

| Cybersecurity and Data Privacy | Fear of hacking, system manipulation, data misuse, and cyber risks. | 9 | 12% |

Note: Some responses contained multiple themes; coding reflects the primary theme. Example Quotes by Theme: 1. Cost/Infrastructure Readiness. “The operation cost might be an obstacle. Technology like this requires high investment.” “Dedicated lanes will be needed, at least in the beginning.” 2. Technology Reliability and Performance. “I don’t trust the technology yet; there are too many uncertainties.” “I see AVs working but only in controlled environments until they prove reliable.” 3. Awareness/Public Understanding. “People need more time to understand AVs before trusting them.” “Awareness campaigns are needed so the public knows how AVs work.” 4. Legal and Regulatory Readiness. “Legal aspects must be addressed first—liability, insurance, safety standards.” “Regulatory clarity is missing for widespread implementation.” 5. Cybersecurity and Data Privacy. “Hacking is my biggest fear.” “Cybersecurity needs to be a top priority for the system to be trusted.”

References

- Acheampong, R.A.; Cugurullo, F.; Gueriau, M.; Dusparic, I. Can autonomous vehicles enable sustainable mobility in future cities? Insights and policy challenges from user preferences over different urban transport options. Cities 2021, 112, 103134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsson, M.; Oliveira, R.; Racca, M.; Kyrki, V. Social robot co-design canvases: A participatory design framework. ACM Trans. Hum. Robot Interact. 2022, 11, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagloee, S.A.; Tavana, M.; Asadi, M.; Oliver, T. Autonomous vehicles: Challenges, opportunities, and future implications for transportation policies. J. Mod. Transp. 2016, 24, 284–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, V.V.; Chand, S.; Nair, D.J. Autonomous vehicles: Disengagements, accidents and reaction times. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0168054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farzin, I.; Mamdoohi, A.R.; Ciari, F. Autonomous Vehicles Acceptance: A Perceived Risk Extension of Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology and Diffusion of Innovation, Evidence from Tehran, Iran. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2023, 39, 2663–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzin, I.; Mamdoohi, A.R.; Ciari, F. Extension of an adoption model to evaluate autonomous vehicles acceptance. Sci. Iran. 2024, 31, 1779–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garikapati, D.; Shetiya, S.S. Autonomous Vehicles: Evolution of Artificial Intelligence and the Current Industry Landscape. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2024, 8, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Karahanna, E.; Straub, D.W. Trust and tam in online shopping: AN integrated model. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 51–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hőgye-Nagy, Á.; Kovács, G.; Kurucz, G. Acceptance of self-driving cars among the university community: Effects of gender, previous experience, technology adoption propensity, and attitudes toward autonomous vehicles. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2023, 94, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, L. Designing Technology for and With Care. 2025. Available online: https://search.proquest.com/openview/890259d08891f545db10f64907607557/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Neufville, R.; Abdalla, H.; Abbas, A. Potential of Connected Fully Autonomous Vehicles in Reducing Congestion and Associated Carbon Emissions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, N.Y.; Kim, Y. Potential of urban land use by autonomous vehicles: Analyzing land use potential in Seoul capital area of Korea. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 101915–101927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, R.; Dwyer, J.; Peterson, A.; Bubke, A.; Cocks, K.; Paz, A. Towards Design Principles for an Accessible Autonomous Vehicle: Promoting Inclusivity, Independence and Well-Being; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2025; Volume Part F903; pp. 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milakis, D.; van Wee, B. Implications of Vehicle Automation for Accessibility and Social Inclusion of People on Low Income, People with Physical and Sensory Disabilities, and Older People; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, G.M. The impact of autonomous vehicles on urban land use patterns. Fla. State Univ. Law Rev. 2020, 48, 193. Available online: https://heinonline.org/hol-cgi-bin/get_pdf.cgi?handle=hein.journals/flsulr48§ion=7 (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Moody, J.; Bailey, N.; Zhao, J. Public perceptions of autonomous vehicle safety: An international comparison. Saf. Sci. 2020, 121, 634–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, A.; Sahib, U. SMART DUBAI: Accelerating Innovation and Leapfrogging E-Democracy. In Advances in 21st Century Human Settlements; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 197–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katona, G.; Juhasz, J. The history of the transport system development and future with sharing and autonomous systems. Commun.—Sci. Lett. Univ. Zilina 2020, 22, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubai Autonomous Transportation Strategy|The Official Portal of the UAE Government. Available online: https://u.ae/en/about-the-uae/strategies-initiatives-and-awards/strategies-plans-and-visions/transport-and-infrastructure/dubai-autonomous-transportation-strategy (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Mohammed, D.; Horváth, B. Public perception of autonomous vehicles acceptance in Hungary. Int. Rev. Appl. Sci. Eng. 2024, 15, 435–447. Available online: https://akjournals.com/view/journals/1848/aop/article-10.1556-1848.2024.00769/article-10.1556-1848.2024.00769.xml?body=fullhtml-27273&utm_source=TrendMD&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=International_Review_of_Applied_Sciences_and_Engineering_TrendMD_0 (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- Narayanan, S.; Chaniotakis, E.; Antoniou, C. Factors Affecting Traffic Flow Efficiency Implications of Connected and Autonomous Vehicles: A Review and Policy Recommendations; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzammel, C.S.; Spichkova, M.; Harland, J. Cultural Influence on Autonomous Vehicles Acceptance; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, H.J.; Chen, T.B.; Chai, L.T.; Khan, N. A Review of Perceived Risk Role in Autonomous Vehicles Acceptance. Int. J. Manag. Financ. Account. 2023, 4, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.F. Developing and Validating a Model for Assessing Autonomous Vehicles Acceptance. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2024, 40, 5503–5516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Wang, N.; Yuen, K.F. Can autonomy level and anthropomorphic characteristics affect public acceptance and trust towards shared autonomous vehicles? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 189, 122384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L. Exploring the Role of Predictability in Fostering Passenger Trust in Autonomous Ride-Hailing: A Case Study of Apollo Go. Adv. Hum. Factors Transp. 2025, 189, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, S.M.; Ho, J.S.; Tan, B.C.; Lau, T.C.; Khan, N. Navigating the Road to Acceptance: Unveiling Psychological and Socio-Demographic Influences on Autonomous Vehicle Adoption in Malaysia. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, I.; Zheng, J.; Iqbal, M.; Ahmad, M.; Jamal, A.; Severino, A. Interpretive structural model for influential factors in electric vehicle charging station location. Energy 2025, 325, 136154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornatzky, L.G.; Fleischer, M. The Processes of Technological Innovation; Lexington Books-Scientific Research Publishing: Lanham, MD, USA, 1990; Available online: https://www.scirp.org/reference/ReferencesPapers?ReferenceID=1771512 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Sun, G.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, H.; Du, X.; Guizani, M. Intersection Fog-Based Distributed Routing for V2V Communication in Urban Vehicular Ad Hoc Networks. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 21, 2409–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X. TOE Framework-Based Digital Strategy Analysis for New Energy Vehicle Enterprises. In Proceedings of the 2025 10th International Conference on Social Sciences and Economic Development (ICSSED 2025), Shanghai, China, 28 February–2 March 2025; 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Guan, R.; Peng, Z.; Xu, C.; Shi, Y.; Ding, W. Exploring radar data representations in autonomous driving: A comprehensive review. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 7401–7425. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/10952908/ (accessed on 15 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Law No. (9) of 2023 Regulating the Operation of Autonomous Vehicles in the Emirate of Dubai. Available online: https://dlp.dubai.gov.ae/Legislation%20Reference/2023/Law%20No.%20(9)%20of%202023%20Regulating%20the%20Operation%20of%20Autonomous%20Vehicles.html (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. Theoretical extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four longitudinal field studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talebpour, A.; Mahmassani, H.S. Influence of connected and autonomous vehicles on traffic flow stability and throughput. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2016, 71, 143–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, D.; Fujiwara, A.; Shiftan, Y.; Chikaraishi, M.; Tenenboim, E.; Nguyen, T.A.H. Risk Perceptions and Public Acceptance of Autonomous Vehicles: A Comparative Study in Japan and Israel. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadafianshahamabadi, R.; Tayarani, M.; Rowangould, G. A closer look at urban development under the emergence of autonomous vehicles: Traffic, land use and air quality impacts. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021, 94, 103113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).