Abstract

Using data of China’s A-share-listed companies between 2014 and 2024, we investigate the effect of carbon finance on the speed of dynamic capital structure adjustment and the degree of deviation of enterprises. We find that carbon finance has a significantly positive effect on the speed of adjusting the capital structure and that carbon finance is consistent in keeping firms in line with their target leverage ratio, according to a number of robustness tests. Notably, cross-sectional analyses show that this effect is more pronounced among firms with lower green innovation outputs and greater indebtedness. Further research indicates that the underlying mechanism driving this relationship lies in alleviating financing constraints and reducing financing costs. By bridging the gap between market-oriented environmental regulations and corporate financial policies, our study provides policymakers with evidence to improve carbon finance mechanisms and gives managers a foundation for transforming carbon finance into a strategic tool for proactively optimizing capital structure.

1. Introduction

To effectively tackle global warming and climate change, many countries have implemented a series of command–control carbon reduction policies. For example, in 1997, the Kyoto Protocol proposed treating carbon emission rights as a tradable commodity in the market, thereby establishing a carbon emission trading system [1]. In 2005, the European Union took the lead in piloting its Emissions Trading System, followed by countries such as New Zealand and the United States. To give full play to the market’s role in carbon governance, the World Bank’s Carbon Finance Sector introduced the concept of carbon finance in 2006. Carbon finance is a trading and investment activity based on “carbon emission rights” and their derivatives. Carbon finance is the market-based environmental regulation and focuses on developing financial mechanisms to support greenhouse gas emission reduction targets and promote a low-carbon economy [2,3]. The growth of carbon finance is closely linked to the carbon finance market, primarily involving the secondary market for trading carbon emission rights. This market encompasses government entities, emission-control enterprises, green companies, financial institutions, and individual stakeholders. Emission-control firms can buy or sell carbon quotas, while green firms provide certified voluntary emission reductions. By facilitating the trading of carbon commodities, the carbon financial market effectively channels green investments and directs capital towards innovative firms, enhancing their incentives for sustainable practices.

Since then, China has established eight carbon emissions trading markets; thus, the development of carbon finance has accelerated rapidly. Policy supports within the carbon finance systems, such as tax incentives and a financing chain, foster a virtuous cycle and strengthen green energy in the macroeconomy by establishing a green supply chain, encouraging collaborative emission reduction among enterprises in the supply chain, promoting an overall green upgrade of the industrial chain, and providing the macroeconomy with sustainable green power. With the development of carbon finance, related research is emerging, aimed at constructing a robust carbon finance market system [4,5,6] and analyzing its macroeconomic effects [7,8]. However, little research examines the significant impact of carbon finance on microenterprises.

The influence of carbon finance on microenterprises is important, since it operates at a systemic level and ultimately depends on how microenterprises alter the financial structures. This knowledge will enable policymakers to plan considered support measures more carefully, thereby assisting the sustainable growth of microenterprises, which is to emphasize fundamentally the great positive contribution that, with the aid of carbon finance, microenterprises will make to macroeconomic growth.

This research is concerned with the effects of carbon finance on dynamic capital structure adjustments. Inventively, capital structure adjustments are dynamic, which is one of the important methods for firms to respond to carbon finance. They induce much more efficient long-term allocation of resources to invigorate the market.

Using data from Chinese A-share-listed companies covering the period from 2014 to 2024, we examine the effect of carbon finance on the dynamic adjustment of capital structure. We find that useful policies on carbon finance materially contribute to optimizing the capital structures of enterprises. More particularly, carbon finance greatly increases the speed of dynamic capital structure adjustments, while the deviation from target capital structures is again much improved, which in turn materially promotes enterprise financing efficiency and contributes to economic sustainable growth in the future.

Furthermore, we examine whether carbon finance can help rectify the inefficiencies in the traditional credit allocation system. We expect that firms with lower levels of green innovation are more likely to optimize their capital structures and accelerate their low-carbon transformation when incentivized by policies. We also expect that the effect of carbon finance on the speed of dynamic structural adjustments is greater in firms with higher liabilities. Indeed, we find that the relationship between carbon finance and the speed of dynamic capital structure adjustment is more pronounced in firms with lower levels of green innovation and liability. Additionally, we find that carbon finance affects dynamic capital structure adjustment by alleviating financing constraints and enhancing monitoring.

Our study contributes to the literature in two ways. First, this paper adds to the literature about the relationship between macroeconomic policies and the dynamic adjustment of capital structures. The existing literature mainly focuses on how macroeconomic factors [9,10], law [11], and economic policy uncertainty [12] affect corporate capital structure adjustments. This paper enriches the prior literature by examining the impact of carbon finance on the dynamic adjustment of capital structure.

Second, this paper expands the prior literature by examining how carbon finance affects firms’ behavior. Existing research mainly focuses on the effects of carbon finance on macroeconomic development [13,14,15,16,17]. However, whether and how carbon finance affects firms’ behavior is unclear. This paper fills the gap by exploring the key role of carbon finance policy in optimizing firms’ capital structure.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Determinants of Dynamic Capital Structure Adjustment

The study of optimal capital structure has evolved from a static to a dynamic framework, laying a solid theoretical foundation for this study. Early classical theories, such as the capital structure irrelevance theory (MM theory) proposed by Modigliani and Miller (1958) [18] in the late 1950s and the subsequent introduction of the ‘taxed MM theory’, opened the way for modern capital structure research. Since then, preferential financing theory, agency theory, and static trade-off theory have been developed, which together reveal how internal factors such as taxes, bankruptcy costs, information asymmetry, and agency conflicts determine the static optimal capital structure.

However, the above static theories have difficulty in explaining why, in reality, firms’ capital structures consistently deviate from the theoretical optimum. These theories also do not explain why firms do not immediately adjust to the target level. To fill this theoretical gap, Fischer et al. (1989) [19] proposed the dynamic trade-off theory of capital structure. This theory states that firms are not always in the optimal state. Each firm has an optimal target capital structure. When a firm’s capital structure deviates from this target, it will adjust its debt-to-equity ratios to bring them to, or close to, the target level [9,19,20,21]. Obviously, the more a firm’s capital structure converges to the target, the more it favors enhancement of the firm’s value [22]. However, many factors affect how firms actually adjust their capital structures. These factors influence both the speed of adjustment [8] and the extent to which actual structures deviate from targets [23]. For example, firms incur adjustment costs due to market frictions such as agency costs and information asymmetry. Firms will only adjust their capital structure when the expected benefit exceeds the adjustment cost. The speed of adjustment depends on the balance between these benefits and costs [24,25,26].

The focus of this study is primarily on external environmental factors affecting enterprises. Existing studies have shown that the macroeconomic environment [9,10,27], the legal environment [11], economic policy uncertainty [12], and other factors have a significant impact on the adjustment of the capital structure of enterprises. For example, the macroeconomic environment affects the speed and scale of the adjustment of the capital structure of enterprises. Enterprises generally speed up the adjustment faster and on a larger scale in a boom period and slowly adjust in a recession period [9,10,27]. The institutional environment also plays an important role. Öztekin and Flannery (2012) [11] find that the better the legal system, the smaller the adjustment cost and the faster the adjustment speed. Economic policy uncertainty makes it difficult for enterprises to predict future policies and government assistance, which may prompt them to adopt a more prudent capital structure strategy to avoid potential shocks [12]. Other factors, such as the marketization process and fiscal and monetary policy, are also found to have an impact on the capital structure decision-making of enterprises [28,29]. Firstly, the external environment can influence the investment opportunity of the enterprises, change the external business risk and capital demand of the enterprises, and thus influence the income of adjusting the capital structure [27]. On the other hand, a change in the external environment may impact the availability and cost of the financing and thus the price of the adjustment of the capital structure [25]. These changes may affect the feasibility and convenience of adjusting the capital structure of the enterprises [30].

The results above show that dynamic capital structure adjustment is still a popular issue in the financial management of enterprises, which focuses on the influencing factors. As a new industry, carbon finance may have a significant impact on the external financial environment of enterprises. The study of how this changing environment leads to the change in capital structure provides a new research angle.

2.2. Research on the Impact of Carbon Finance on Enterprises

The concept of carbon finance has emerged as an important field as the low-carbon economy has developed [31]. Carbon finance is a market-based environmental regulation and focuses on and creating financial mechanisms to support greenhouse gas emission reduction targets and promote a low-carbon economy [2,3]. This concept is connected to, yet distinct from, climate finance and green finance. Green finance refers to financial services that support environmentally friendly economic activities, address climate change, and promote resource efficiency. Its scope is the broadest. Climate finance, a crucial and substantial subset of green finance, is a specific financial activity that aims to address climate change. It focuses on mitigating and adapting to climate change. Carbon finance encompasses financial activities centered on carbon emissions trading and pricing mechanisms. Carbon finance serves as a tool and a subset of climate finance, particularly within the mitigation domain. Its purpose is to establish economic incentives for reducing emissions through market-based mechanisms that assign a price to carbon emissions. Scholars generally agree that carbon finance is a vital part of the global climate governance system and that its influence on the financial sector cannot be ignored [32]. As an investment and financing activity focused on reducing carbon emissions, carbon finance centers on pricing carbon-emission rights through financial innovation. It guides the flow of funds to low-carbon technologies and applications and is attracting increasing attention from all quarters.

Carbon finance is attracting a profoundly increasing number of scholars studying it in depth. From a macro perspective, research abroad and at home on the impact of carbon finance has focused mainly on increasing carbon market capacity; also, the effects of reducing carbon emissions and stimulating macroeconomic development have been investigated. Geng et al. (2022) [33] state that carbon finance can promote green and inclusive economic growth by reconstructing the financial system. Fullerton and West (2002) [34] found that carbon finance is a rapidly growing field that has already led to considerable reductions in greenhouse gas emissions through ‘carbon trading and services’. Many studies have examined the efficiency of carbon trading. Amongst others, the correctness of the following conclusions can be drawn from the studies carried out. Using a multi-actor general equilibrium model, Tang et al. (2015) [35] found that trading in carbon emissions substantially reduced GHG emissions. Zhou and Li (2019) [2] have found that carbon finance helps achieve low-cost emissions reductions. Klemetsen et al. (2020) [36] and Colmer et al. (2025) [37] both found that schemes leading to trading in carbon emissions caused a substantial reduction in the emissions of regulated factories and enabled a direct effect on the level of emissions. Further to this, Gao (2023) [38] used county-based satellite data from China to show that carbon finance helps promote low-carbon economic growth to a greater extent and pointed to the importance of financial mechanisms. Ren and Fu (2019) [39] have shown that measures like those referred to can also improve regional total factor productivity, thereby leading to greater economic effects. From the perspective of green economic efficiency, Liao et al. (2020) [40] show that carbon emissions trading promotes green economic growth by stimulating innovation. These conclusions have been confirmed by Jiang et al. (2023) [7], who have seen that carbon finance is of great help to the attainment of qualitative high economic growth.

However, there remains a notable gap in research regarding the influence of carbon finance on corporate financing decisions as a financial tool in addressing firms’ decision-making. Our research is most closely connected to Campiglio (2016) [41], who provides the best general understanding of the role of green finance in low-carbon financing through a real-world analysis of carbon finance. In this paper, Campiglio (2016) [41] notes the opportunity to discuss concrete obstacles related to corporate behaviors of transition to low carbon, a possible problem of high risk and low return in the innovation link. Campiglio (2016) [41] proposes the establishment of new, specific financial institutions or of confirmed additional capital market policies distinct from the normal structures of interest rates to meet financial supply purposes. This research emphasizes the fact that if carbon finance makes advancement possible, it can reduce financial constraints a lot in the progress of time of the transition to low carbon. We have widened this literature again to think over the profit within the variable constitutional financial structure of carbon finance.

3. Theoretical Analysis and Research Assumptions

3.1. Carbon Finance and Capital Structure Adjustment

The primary aim of carbon finance is to facilitate and encourage the development of a low-carbon economy through various financial mechanisms. This is achieved through a squeeze of mechanisms based on markets. The duality of carbon finance as a device for government surveillance and as a market-based approach is effective in changing the capital structure through the easing of the constraint on finance and the improvement of regulatory surveillance.

From the perspective of alleviating financing constraints, carbon finance is positively associated with the availability of funding to firms and accelerates the changes necessary in their capital structures. Carbon credit pledge financing, too, inverts the rights to future revenue from carbon assets into existing collateral, thus unlocking an illiquid form of environmental assets and effectively making them available to the varying capital structures. Moreover, it addresses the engineering problems posed by green projects through innovative financial mechanisms that address the capital mismatch arising from high initial investments and a long cycle of returns. To summarize, the innovative financial tools provided by carbon finance render enterprises diverse financing mechanisms and greatly improve access to financing. These financial tools enable enterprises to adjust their leverage levels more flexibly, reducing financing costs and improving access to funds, thereby accelerating the convergence of their capital structures toward target levels.

The governance aspect of carbon finance enhances the credit efficiency of financial institutions from the perspective of alleviating financing constraints. The funds which flow through carbon finance arise from banks, institutional investors, and even state treasuries. The funding basis and credit orientation permits more elastic financing of enterprises. As carbon finance is extended, the capital supply mechanism is also changing. The channels of financing have also shifted from being primarily governmental and by the banks to being more marketized. Thus, as carbon finance continues, the transaction costs to the enterprises for obtaining external funds for credit will decrease. The new efficient and varied method will minimize the transaction costs normally incurred by enterprises in changing their capital structure and expedite the adjustments.

Furthermore, carbon finance can improve supervision of debt and accelerate the process of restructuring capital. Debt in this case serves to control firms’ free cash flow, limit excessive spending by management, and correct self-serving managers [42], which induces managers to work with greater diligence. Carbon finance is subject to a multi-layered system of strict state supervision, which is designed to achieve climate goals, prevent greenwashing, and preserve market reliability. In particular, loans to various credit institutions are protections, state-enforced enforcement measures, and financial penalties. In this case, the government uses blockchain technologies to control transactions, diminish the amount of credit attributed to moral hazard in the credit market, and accelerate the process of corporate capital structure.

In conclusion, if a company’s capital structure is too low relative to its target capital structure, it must increase liabilities. The progress of carbon financing increases the company’s access to financing. It also lowers the cost of funds raised on credit. This permits management to secure credit funds at reduced costs from a greater number of sources, thus raising the liability level and diminishing the distance from the target capital structure. On the other hand, if the capital structure is above the target, too great liabilities may be incurred, resulting in increased financial risk and bankruptcy costs, necessitating a reduction in liabilities. It follows that the over-indebtedness resulting therefrom increases the financial risk to the company and the bankruptcy costs, thus inducing management to lower the level of indebtedness. Furthermore, the impact of carbon finance may increase the financial risk and bankruptcy costs resulting from over-indebtedness, which has the effect of inducing management to reduce liabilities. Hence, the following hypothesis is advanced by this study:

H1.

Carbon finance has accelerated the pace of dynamic capital structure adjustments within enterprises.

3.2. Carbon Finance and the Allocation of Credit Resources

Research has shown that the distribution of lending resources in traditional financial systems is often inefficient, leading to credit discrimination [43]. This can slow the distribution of credit resources to the real economy, creating excessive capital in corporations that invest their capital surpluses in financial markets, while organizations that really require credit for ongoing financing are unable to secure it [44]. The result is a slower capital utilization of the concerned enterprises and a lower degree of value of the company.

Studies suggest that the level of debt is an important factor in the adjustment made by firms in their capital structure. The speed at which they move towards the target capital structure differs significantly between over-indebted and under-indebted firms. It is therefore essential to take this asymmetrical position into account in empirical studies of capital structure. In practice, however, it is exactly the motivation, weight, and speed of adjustment to capital structure that differ widely between firms according to their levels of indebtedness. For example, over-indebted firms are likely to be more risk-averse and more inclined to realign themselves with their normal objective gearing. On the other hand, under-indebted firms may be less likely to approach recapitalization because they have a lower level of financial risk [45].

Similarly, the development of carbon finance can help compensate for these inefficiencies in the traditional credit allocation system [46]. Carbon finance exists mainly for the purpose of supporting those green and innovative firms that have decided to change their practices in a sustainable direction, and it provides a definite advantage in available access to the required credit resources in question. With enhanced policy signals and increased market liquidity, carbon finance expands its financial support for green and innovative firms, enabling them to secure more self-financing from financial institutions and overcome barriers to technological innovation. As a result, enterprises with lower green innovation gain greater flexibility in their recapitalization efforts and can more swiftly adjust their capital structures.

In summary, we expect the relationship between carbon finance and the speed of dynamic capital structure adjustment to vary with liability and green innovation.

H2a.

The relationship between carbon finance and the pace of dynamic capital structure adjustment is more pronounced among enterprises with relatively high debt ratios.

H2b.

The relationship between carbon finance and the pace of dynamic capital structure adjustment is more pronounced among enterprises with lower green innovation capabilities.

3.3. The Mediating Mechanism of Carbon Finance in Influencing Dynamic Capital Structure Adjustment

According to dynamic capital structure theory, firms have an optimal capital structure. However, due to adjustment costs, their actual capital structure continuously deviates from the target level [30]. These adjustment costs primarily manifest as frictions in external financing, centered on financing constraints (i.e., the ease of obtaining funds) and financing costs (i.e., the price of acquiring capital) [11]. Carbon finance is a market mechanism that internalizes environmental risks and rewards. This, in addition to reducing adjustment frictions through two parallel, interconnected pathways, can be effective in accelerating the convergence to the target capital structure for firms.

To begin with, there are mechanisms for relieving financing constraints. These constraints are caused by information asymmetry, agency problems, and agency information asymmetry in capital markets. Such problems exclude enterprises from receiving, when they want it, sufficient outside finance on reasonable terms [47]. Carbon finance, with its specific information-governance and resource-allocation qualities, can, in a systematic manner, relieve such financing constraints. The systems in carbon finance, such as carbon emissions trading systems and procedures such as the green credit approval process, require firms to disclose standardized verifiable information about their carbon emissions and environmental impacts. This is a type of certification process. It transmits favorable signals to capital markets about a firms’ governance standards, technological advances, and long-run sustainable development competencies [48]. This diminishes information asymmetries between firms and the market [49]. This diminishment reduces adverse selection and credit rationing stemming from information asymmetry. Within the sustainable finance ambit, financiers are increasingly incorporating environmental performance into the core decision-making processes used in credit assessments. Strong carbon credentials are viewed as key indicators of lower policy and transition risk for enterprises [50]. Hence, the evolution of carbon finance encourages banks to favorably allocate credit resources to low-carbon enterprises. This enhances their access to debt finance. In addition, with the reduction in financing constraints, there are fewer impediments for enterprises which want to secure outside funding in the course of capital structure adjustments. When financing constraints are acute, firms that have been used to formulating viable capital structure adjustments often refrain from implementing changes in structural arrangements because they cannot secure timely finance [11]. On the contrary, a loosening up of financing constraints improves the flexibility of firms and allows for, more readily, swifter access when required to capital markets when they have deviations in their capital structure. The necessary finance is then able to be obtained for adjustments [9]. Hence, carbon finance enhances the feasibility of more rapid adjustments in capital structure by modifying the accessibility of financing.

Secondly, there is a reduction in the financing costs mechanism. Financing costs are a direct price friction in capital structure adjustments. Carbon finance affects both the quantity (supply) and price (cost) of capital. Financial institutions incur substantial costs in collecting, processing, and supervising information in their lending operations. The monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) systems instituted by carbon finance provide reliable, third-party-certified information about corporate environmental performance. This greatly reduces the investigation costs and ongoing supervising costs to financial institutions [51]. Lower supervising costs induce financial institutions to be more willing and effective in leveraging the governance function of debt to reduce management’s moral hazard [42]. As agency costs are reduced, the resulting credit risk premium declines in parallel. Climate risks have also become an important factor in asset pricing. Empirical studies show that capital markets price climate risks. Investors require higher expected returns on carbon-intensive assets to compensate for the loss potential in the future [52]. Conversely, corporations with higher carbon performance demonstrate greater reliability in future cash flows and asset security. Therefore, the equity and debt capital markets require lower environmental risk premiums. By identifying and rewarding such corporations, carbon finance can lower their overall capital costs directly [50]. Lower financing costs also directly increase the marginal benefits of capital structure adjustments. According to the trade-off theory, firms constantly weigh the benefits of adjusting to target levels against the costs to be incurred. A major element of these adjustment costs is high financing costs, which inhibit firms’ motivation to adjust [30]. Where the financing costs decline due to the result of carbon finance, the actual cost of equity financing or debt refinancing declines. Then, the adjustment in either direction, up by an increase in debt or down by a decrease in debt, becomes economically more viable, greatly increasing firms’ incentives to proactively and quickly restructure their capital.

In summary, carbon finance influences the pace of capital structure adjustment through two mechanisms: alleviating financing constraints and reducing financing costs.

H3a.

Carbon finance can accelerate firms’ dynamic capital structure adjustments by alleviating financing constraints.

H3b.

Carbon finance can accelerate firms’ dynamic capital structure adjustments by reducing financing costs.

3.4. Theoretical Framework

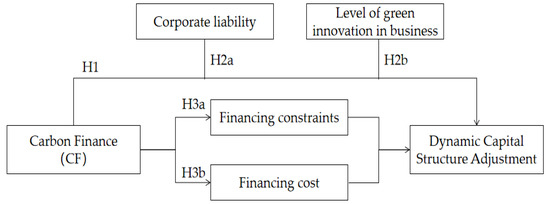

The theoretical framework for this study is depicted in Figure 1, which shows the causal relationships study. The above research hypotheses provide the basis for the framework, which seeks to develop a clearly articulated, mechanistically consistent analytical framework. First, it is expressly concerned with the direct effects of carbon finance on firms’ dynamic capital structure adjustments (H1). Second, it concerns the fact that this relationship will differ across companies with varying levels of indebtedness (H2a) and different levels of green innovation (H2b). Finally, it will put forward the mechanisms of carbon finance which we have suggested operate synchronously, namely, the alleviating of financing constraints (H3a) and the lowering of financing costs (H3b), in other words, accelerating the dynamic capital structure adjustment process.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework diagram of the impact of carbon finance on dynamic capital structure adjustments in enterprises.

This theoretical framework offers detailed guidance for statistical testing later. By uniting direct effects, cross-sectional investigation, and underlying mechanisms, it clarifies the complex interaction between carbon finance and financial behavior in corporations. It also gives a more systematic basis for investigation for what is behind the improvement of capital structure. The following sections will use statistical models to test the theoretical concepts rigorously.

4. Research Design

4.1. Data Source and Sample

This research subject is focused on the listed companies in China for the period between 2014 and 2024. We use the data from 2014 to 2024 because 2014 can be regarded as the first full year in which carbon finance policies shifted from institutional establishment to market operation, thus better reflecting their actual impact on corporate financial behavior. The relevant data on enterprises comes from the CSMAR database. The sample is narrowed according to the following rules: (1) financial companies are excluded; (2) companies tagged as ST, PT, and *ST are omitted; and (3) samples with missing variables or aberrant data are disregarded. All continuous variables are winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles to reduce the influence of outliers. The data for the development of carbon finance are accounted for in the China Statistical Yearbook, China Energy Statistical Yearbook, and Financial Statistical Yearbook. Some of this information, integrated with the firm data, made a database with 15,128 annual records.

4.2. Variable and Model Design

4.2.1. Independent Variables

This study creates a carbon finance development index (CF) to measure the level of carbon finance development in Chinese provinces. The carbon finance system encompasses multiple dimensions, including economics, finance, the environment, and energy. It is influenced by factors such as economic foundations, technological capabilities, and national policies. When selecting evaluation indicators, it is important to ensure comparability, scientific rigor, practicality, operability, systematicity, and a hierarchical structure while remaining grounded in objective realities that fully reflect the essence and uniqueness of carbon finance. Specifically, the indicator system is constructed from the following five dimensions. The entropy method is employed to evaluate the levels of carbon finance development in China’s 30 provinces based on the variability in each indicator. First, the data standardization process is conducted. To eliminate the impact of dimensional differences, range standardization is applied to both positive and negative indicators to ensure dimensionless processing of raw data. For positive indicators . For negative indicators, . Here, i denotes the enterprise under evaluation, and j denotes the evaluation indicator. Next, the data is normalized to obtain a standard matrix . The entropy values for each indicator are calculated, , where K = 1/ln n, and n is the number of companies to be evaluated. Finally, the coefficient of variation for each indicator is calculated, , and the total weight for each indicator is calculated, , where j = 1, 2, …, m, and m is the number of evaluation indicators. Therefore, the value of the carbon finance development level for the i enterprise is . The specific indicators and their weights are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The measurement indicator system for the development level of carbon finance.

Financial Environment (FE): This is a positive indicator measured by the financial sector’s value added. Value added by the financial sector refers to the outcomes generated by financial production activities within a specific period. It reflects the regional financial industry’s overall development level and dynamism. A vibrant and developed FE can provide richer, more efficient financial services and ample financial support, as well as diversified financing channels for low-carbon technology research and development (R&D), clean energy projects, and industrial green transformation [53]. A more developed financial sector typically indicates greater depth, breadth, and efficiency in the region’s financial markets [54]. This facilitates the attraction and allocation of capital toward green and low-carbon sectors, driving the formation and development of a carbon finance ecosystem. Thus, the magnitude of the financial sector’s value added directly reflects the quality and potential of the financial environment that underpins the development of carbon finance.

Technological Innovation (TI): TI is characterized and measured by the number of regional patent authorizations, a positive indicator. TI is the driving force behind reducing carbon emission intensity, improving energy utilization efficiency, and achieving green transformation [55]. More patent authorizations lead to greater research and development (R&D) output and innovation capabilities [56], which are directly related to breakthroughs and applications of energy-saving and carbon-reducing technologies. Progress in these technologies can directly reduce carbon emissions in the production process and spawn new green industries and business models [57], providing a solid technical foundation and broad application scenarios for the carbon finance market. Thus, the number of regional patent authorizations reflects a region’s innovation vitality and its accumulation of low-carbon technology. It is also a key indicator of a region’s long-term potential for low-carbon transformation and technical support capabilities for carbon finance development.

Policy Support (PS): The green credit ratio, which is the proportion of interest expenditure of the six high-energy-consuming industries to the total interest expenditure of industrial industries, is a negative indicator used for characterization and measurement. It reflects the financial system’s support for green and low-carbon industries, as well as the degree to which high-carbon industries are restricted in the allocation of credit resources [58]. It also reflects financial institutions’ response to the national green industry policy and the “dual-carbon” goal in credit investment. A lower ratio indicates a smaller proportion of credit funds flowing to high-carbon industries. This means that more credit resources are allocated to low-carbon or green industries and enterprises. It reflects financial institutions’ inclination toward green and low-carbon development, as well as restrictions on high-carbon activities in credit policy [59]. Such behavior is an important indicator of the government’s promotion of carbon finance development.

Energy Efficiency (EE): This is measured by carbon emissions intensity per unit of GDP, calculated by dividing carbon emissions by regional GDP. This is a negative indicator. It reflects the degree to which economic development depends on resource and energy consumption, as well as the contribution of regional economic growth to carbon emissions [60]. In theory, a lower carbon emissions intensity per unit of GDP leads to a smaller increase in carbon emissions as the same unit of GDP grows with technological and economic development. This reflects the level of science and technology, as well as the rationality of economic growth structures. This indicator is also related to the level of economic development and to carbon emissions from fossil fuel consumption. It directly reflects the utilization rate of carbon resources by society as a whole [61] and the comprehensive development level of low-carbon technology over a given period. Because carbon emissions intensity is related to the economic structure, the size of the indicator reflects the obstacles and the potential for further reducing energy intensity when regional technical and monetary capital accumulation reaches a certain level.

Financial Decarbonization (FC): This indicator reflects the degree to which financial institutions participate in carbon finance. It is characterized and measured by financial carbon intensity, a negative indicator. Financial carbon intensity is the amount of carbon in the financial system. It is expressed as the ratio of a region’s total carbon emissions to its total social financing, or the amount of carbon emissions supported by total social financing per unit. FC depicts the relationship between regional financial development and carbon emissions and reflects sustainable financial development. Changes to this indicator reflect profound shifts, including modifications to the financial resource allocation mechanism, the capital utilization structure, and continuous innovation in environmental finance [62]. Due to the unavailability of total social financing data for each province, this study uses the balance of financial institutions’ various loans as a proxy for total social financing.

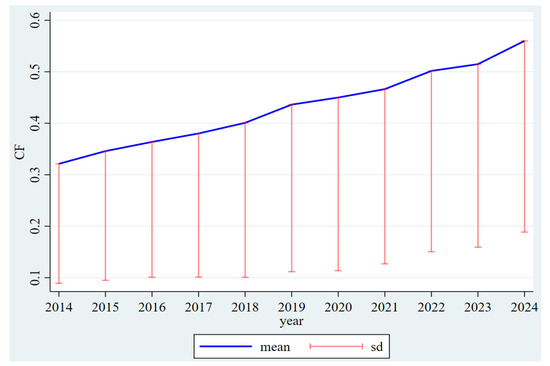

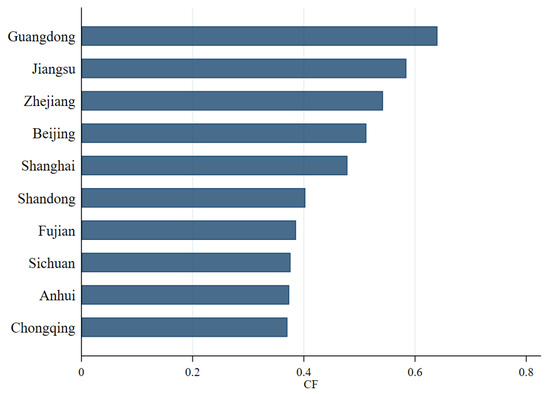

According to the aforementioned index system, the time-trend analysis of China’s carbon finance development is presented in Figure 2. The results indicate that the national carbon finance development level index increased from 0.32 in 2014 to 0.56 in 2024, a 75% increase, indicating a continuous and steady upward trend. This indicator proves that China’s carbon finance system has undergone significant development and refinement over the past decade. From 2014 to 2024, the top ten provinces in the national carbon finance development index were Guangdong, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Beijing, Shanghai, Shandong, Fujian, Sichuan, Anhui, and Chongqing, in that order. Figure 3 shows the specific results. Guangdong province ranked first with an index value of 0.64. Geographically, eight of the top ten provinces are in the economically developed eastern coastal areas with abundant financial resources. This indicates that carbon finance development is closely related to regional economic levels and policy support. Additionally, Sichuan and Chongqing were selected as representatives of the western region, reflecting positive progress in carbon finance under the western development strategy.

Figure 2.

Time trend analysis of the national carbon finance development level.

Figure 3.

Top 10 provinces by carbon finance development index.

4.2.2. Dependent Variable

Based on studies such as those by Byoun (2008) [63] and Flannery and Rangan (2006) [30], the partial adjustment model estimates the speed at which firms adjust their capital structures. We construct the following model:

where Levi,t represents the actual debt ratio of firm i in year t. Lev_pi,t−1 denotes the adjusted debt ratio of firm i in the previous year t − 1. Di,t is the book value of the firm’s interest-bearing liabilities at the end of year t. Ai,t indicates the book value of the total assets of firm i at the close of year t. NIi,t refers to the net profit of firm i in year t. The term εi,t is a disturbance term. This study focuses on the coefficient γ in Equation (1), whose value typically lies between 0 and 1. Levi,t is the reduction in the gap between the actual and target debt ratios of firm i in year t at a rate of γ. A larger γ value indicates a faster adjustment rate to the firm’s capital structure. The literature has proved that a firm’s target capital structure is determined by factors such as the characteristics and continuous changes in response to changes in the firm’s internal and external environment [30]. Therefore, a firm’s target capital structure is measured by model (2).

where β signifies the regression coefficient associated with a set of characteristic variables related to capital structure, and Controlsi,t−1 represents a characteristic variable influencing the target capital structure. This equation includes control variables such as firm size (Size), firm age (Age), and capital expenditure (Capex) while controlling for industry and year fixed effects. Equation (2) is incorporated into Equation (1) to estimate the target capital structure, resulting in Equation (3):

The firm’s target capital structure () is obtained by regressing Equation (3) and obtaining the estimated value of β, which is then brought into Equation (2). Substituting into Equation (1) examines the impact of carbon finance on the speed of capital structure adjustment. The model adds the cross-multiplier term of the index of the level of development of carbon finance and the degree of deviation of the capital structure to Equation (1):

where , ; CFi,t−1 is the index of the level of carbon finance development. To alleviate the endogeneity problem, this study lags the independent variables by one period. The focus is on the γ1 coefficient, which measures the impact of carbon finance on the speed of corporate recapitalization. If γ1 is significantly greater than zero, it indicates that carbon finance accelerates the recapitalization process. Equation (4) controls for industry and year fixed effects and clusters standard errors at the firm level.

Based on this, the study goes on to analyze the impact of carbon finance on the degree of capital structure deviation. If carbon finance improves the speed at which firms adjust their capital structures, then, in practical terms, it will significantly reduce the deviation of firms’ capital structures from their target structures. Therefore, this study sets the AbsDevi,t variable, representing the degree of capital structure deviation from the target, as the explanatory variable in Equation (2). At the same time, the index representing the level of carbon finance development (CFi,t−1) is added to the right-hand side of the equation, resulting in the following model:

where AbsDevi,t is the absolute value of the difference between the actual and target debt ratios for the period, with the same control variables as in Equation (4), and still controlling for industry and year fixed effects.

4.2.3. Control Variables

(1) Firm age (Age) is measured by the natural logarithm of the difference between the year of observation and the year of establishment. This variable reflects the firm’s historical experience, market maturity, and stability. (2) Firm size (Size) is measured by the natural logarithm of total assets. This variable indicates the enterprise’s resource endowment, market position, and the effects of economies of scale and risk mitigation. (3) Total return on assets (ROA) is measured by the ratio of total profit and interest expense to average total assets. This important measure of corporate profitability is useful in evaluating capital allocation decisions and investment policies. (4) Capital expenditures (Capex) are measured as the ratio of capital expenditures to total assets. This provides an estimate of company growth like asset expansion, asset replacement, and long-term strategic investments. (5) Selling general and administrative expenses (SG&A) are measured by the ratio of SG&A expenses to total assets. This indicates management efficiency, the structure of operating expenses, and the use of company resources. (6) Total asset turnover (AssetsCh) is measured by the ratio of net operating income to average total assets. This provides an estimate of operating efficiency and asset use, both of which are important in capital investment decisions. (7) Stock performance (return) is measured by the annual return of the individual stock, including the reinvestment of dividends. This variable reflects market recognition of the company and investor expectations and current market sentiment and valuations. (8) Institutional investor ownership (IO) is measured by the percentage of shares owned by institutional investors. This indicates the intensity of institutional supervision of corporate governance and the extent of specialization of shareholders, with the overall indication of the company’s outside environment of corporate governance. (9) Reported volatility of stock (Sigma) is measured with the standard deviation of weekly annual stock returns. This indicates the risk of the firm in the market and uncertainty, as well as the company’s risk in the opinion of the investor.

This study introduces control variables for each province to improve the model’s explanatory power and regression line strength. (1) Economic development level (GDP growth) is measured as the provincial gross per capita GDP growth, it is a representation of the general economic dynamism of each province and the cyclical oscillation thereof. (2) Financial development level (Loans) is measured as the percentage of loans of financial institutions to GDP, which is a measure of the availability of financing of regional financial resources, which plays a key role in the sources of financing and costs to companies relating to financing. (3) Industry structure (Industry) is measured as the ratio of the value added of the tertiary industry to that of the secondary. This indicator shows the advanced characteristics of the economic structure of each of the provinces, which again affects management performance, competitive position, and level of competitive advantage. By incorporating these provincial-level control variables, the study can more comprehensively assess the impact of provincial-level indicators on firms’ dynamic capital structure adjustments while controlling for the potential confounding effects of provincial characteristics.

4.2.4. Robustness Variables

To examine how green finance influences the dynamic adjustment of capital structure, the following model has been developed:

Among them, GFi,t−1 is the level of green financial development, as measured by the entropy method. Controls are applied using the same model (4). It still controls for industry and year fixed effects.

4.2.5. Cross-Sectional Variables

To conduct cross-sectional tests, the following model was set up for this study:

where Misi,t represents Debt and GI. Debt is the difference between the firm’s capital structure at the beginning of year t. Levi,t and its target capital structure are used to measure the level of corporate liabilities following Byoun (2008) [63]. When Levi,t— > 0, the real debt level of the company at the beginning of the year is higher than the target debt ratio for the year, and the company is over-indebted; debt takes the value of 1. Conversely, when Levi,t— is less than zero, the company is under-indebted, and Scale takes the value of 0.

The green innovation level of the company (GI) is measured by the ratio of the number of green utility models independently filed by enterprises to the total number of patent applications in the same year. If this ratio is smaller than the median for that year, GI takes a value of 1; otherwise, it takes a value of 0. We are still controlling for industry and year fixed effects. If there is indeed a mismatch of credit resources, the coefficient ρ2 in Equation (8) should be significantly negative. Conversely, if carbon finance can alleviate this mismatch, the coefficient ρ3 in Equation (8) should be significantly positive.

4.2.6. Mediating Variables

To further validate this study’s theoretical logic and analyze how carbon finance influences the dynamic adjustment of corporate capital structure, the following mediation-effect model is set up, based on the mediation test by Glaveli and Geormas [64].

In Equations (9)–(11), Med is the mediating variable. Specifically, Med includes two indicators: financing constraint (KZ) and financing cost (Cost). This study uses the KZ index to measure firms’ financing constraints and the cost of debt financing to measure financing costs. The latter is the ratio of total interest, fees, and other financial expenses to total liabilities at the end of the period. ϕ0, φ0, and θ0 are constant terms and ϕ1, ϕn, φ1, φ2, φ3, θ1, θ2, and θn are regression coefficients. The control variables are the same as in model (4). Industry and year fixed effects are still controlled for. Suppose carbon finance eases financing constraints and reduces financing costs for enterprises, thereby improving the speed of enterprise capital structure adjustment and reducing target capital structure deviation. In that case, this study expects the ϕ1 coefficient in Equation (9) to be significantly negative and the φ3 coefficient in Equation (10) to be significantly negative. It also expects the θ2 coefficient in Equation (11) to be significantly positive.

The definitions of the key variables are shown in Table 2. Descriptive statistics are shown in Table 3. This shows significant correlations among the variables, and the paper will conduct multivariate linear regression analyses based on the correlation results.

Table 2.

Variable definition.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics.

5. Empirical Analysis

5.1. Baseline Regression

Table 4 presents the results of the baseline regression analysis investigating the impact of the level of carbon finance on the dynamic adjustment of the capital structure. Columns (1) and (2) analyze the effects of carbon finance on the speed of capital structure adjustment. Column (1) controls for industry and year fixed effects, but no other control variables are included. The regression results show a significant positive relationship, indicating that carbon finance can effectively increase the speed of corporate capital structure adjustment. Column (2) introduces firm- and province-level control variables; the findings remain significant. Specifically, the key coefficient of Formula (4) can be obtained from column (2) of Table 4: the coefficient of CF × TLev is γ1 = 0.407. When the enterprise’s carbon finance development level increases from the 25th percentile (0.3352) to the 75th percentile (0.5559), the speed at which the enterprise’s capital structure adjusts will increase by about 8.98 percentage points γ1 × (CF75 − CF25) ≈ 0.0898). This data indicates that the enterprise will accelerate its adjustment to the target capital structure.

Table 4.

Results of the baseline regression.

Columns (3) and (4) analyze the effect of carbon finance on the degree of deviation from the target capital structure. Column (3) controls for industry and year fixed effects but does not include other control variables. The regression results show a significant negative relationship, indicating that carbon finance reduces the deviation of firms’ capital structures from their target structures. The results remain significant when firm- and province-level control variables are included in column (4). The key coefficient of Formula (5) can be found in column (4) of Table 4. The coefficient of CF is β1 = −0.155. When the level of carbon finance increases from the 25th to the 75th percentile, the deviation of the capital structure target decreases by approximately 3.42 percentage points.

Therefore, we can confirm the hypothesis that carbon finance significantly increases the speed at which corporate capital structures adapt and reduces the degree to which they deviate from the target capital structure.

5.2. Robustness Tests

5.2.1. Endogeneity Test

Since corporate capital structure adjustments are continuous, the previous period’s explained variable may affect the current period’s explained variable, resulting in estimation bias. To eliminate this effect, this study incorporates the first-order lag term of the dependent variable into the model and uses dynamic panel GMM estimation. The results are shown in Table 5. The results show that the speed and degree of capital structure adjustment and deviation in one period significantly affect the next period. This suggests that the dynamic effects of capital structure adjustments cannot be ignored. After controlling for the lagged one-period explanatory variable, the sign of the core explanatory variable remains consistent with the benchmark regression. That is, CF × TLev in column (1) remains significantly positive, and CF in column (2) remains significantly negative. This variation does not change the basic assumption of carbon finance regarding the dynamic adjustment of enterprises’ capital structures.

Table 5.

Dynamic panel estimation.

Additionally, the AR(1) statistic is less than 0.1, and the AR(2) statistic is greater than 0.1. This result indicates that there is only first-order autocorrelation and no second-order serial autocorrelation. These results meet the assumptions for using the dynamic panel GMM model. Furthermore, the p-value of the Hansen test is between 0.1 and 0.25. The original hypothesis that the instrumental variables are exogenous is accepted. This indicates that the instrumental variables are effective. These results fully prove the robustness of the benchmark regression.

Furthermore, to mitigate the endogeneity problem due to reverse causality, we selected the average index of carbon finance development in the other provinces for the same year as an instrumental variable. Due to spatial correlation, the carbon finance levels in different provinces have a demonstration and competitive effect on the province, thus affecting its own level of development. This is consistent with the correlation between instrumental variables. At the same time, however, the enterprise’s dynamic capital structure adjustment is not easily affected by the carbon finance development in other provinces during the same year. When calculating the carbon finance level of other provinces in the same year, the development level of the province where the enterprise is located is not considered, thereby meeting the exogeneity requirements of instrumental variables. Therefore, it is reasonable and practical for this study to use the average level of carbon finance development in other provinces for the same year as an instrumental variable.

The results of the two-stage regression are presented in Table 6, with columns (1) and (2) representing carbon finance and the speed of capital structure adjustment, and columns (3) and (4) representing carbon finance and the deviation from the target capital structure. The first-stage regression results in columns (1) and (3) show that the coefficients of Mean_CF × TLev and Mean_CF are significantly positive at the 1% level. They also pass the non-identifiability test and the weak instrumental variable test, indicating that the instrumental variables are appropriately selected. In the second-stage regression results in columns (2) and (4), the CF × TLev and CF coefficients are consistent with the benchmark regression results. These regression results suggest that using the instrumental variable method to address the endogeneity issue leads to a significant increase in the level of carbon finance development, which drives the speed of corporate capital structure adjustment and reduces the deviation from the target capital structure.

Table 6.

Instrumental variables results.

5.2.2. Other Robustness Tests

In addition, this study conducts further robustness tests.

The carbon finance development level evaluation index system comprises five aspects: financial environment (FE), technological innovation (TI), policy support (PS), energy efficiency (EE), and financial decarbonization (FC). In this section, each dimension is regressed against the dynamic adjustment speed and target deviation of corporate capital structure, and the results are presented in Table 7. The results show that, for columns (1) through (4), the regressions of FE and TI on the dynamic adjustment speed and target deviation of corporate capital structure are consistent with the benchmark regression. The positive indicators further demonstrate the robustness of the regression results. Columns (5) to (10) show that the regression results of policy support (PS), energy efficiency (EE), and financial decarbonization (FC), as negative indicators, are opposite to the benchmark regression results. This evidence also proves the robustness of the regression results.

Table 7.

Sub-dimensional test.

In this section, the independent variable, carbon finance, is replaced by the green finance development index in columns (1) and (2) of Table 8. The coefficient for the interaction term GF*TLev in column (1) is significantly positive, indicating that green finance accelerates firms’ capital structure adjustments. The coefficient of the interaction term GF*TLev in column (2) is significantly negative, indicating that green finance substantially reduces the degree of deviation from the target capital structure. The robustness of the above findings is further verified.

Table 8.

Robustness test.

In column (3), the estimation results are based on the partial adjustment model. This section uses the partial adjustment model to test the impact of carbon finance on the speed of firms’ capital structure adjustment, constructing the following model:

At this point, the speed at which firms adjust their capital structure is such that, if the coefficient λ is significantly negative, it indicates that carbon finance increases this speed. In contrast, a significantly positive coefficient indicates the opposite: it decreases this speed. Controls are the same as Equation (4). It still controls for industry and year fixed effects. The regression results are shown in column (3) of Table 8. The results show that the coefficient of the cross-multiplier term of CF × Lev_p is significantly negative, which is highly consistent with the main regression findings.

Given the higher level of carbon financial development in municipalities, the results of this study may be sample-specific. Therefore, the test was re-run with the municipalities removed, and the regression results are shown in columns (4) to (5) in Table 8. These results show that, even after removing municipalities directly under the central government, the effect of the level of carbon financial development on the deviation of firms’ capital structure adjustment speed from the target capital structure remains consistent with the principal regression. This further verifies the robustness of the conclusions.

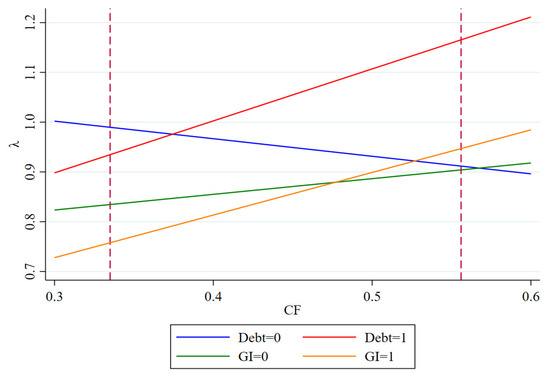

5.3. Cross-Sectional Test

In traditional finance, allocating credit resources poses a problem that manifests as certain forms of credit discrimination. This hinders support for green technology innovation, preventing enterprises that need credit support from obtaining funds. It also reduces the speed at which enterprises adjust their capital structure and decreases their value. The development of carbon finance can help alleviate traditional finance’s inefficiencies in allocating credit resources. This part of the empirical regression analysis is based on model (10), and the results are shown in Table 9. In column (1), the coefficient of Debt × TLev is significantly negative at the 1% level, indicating that highly indebted firms have a slower rate of capital restructuring. In comparison, the coefficient of Debt × CF × TLev is significantly positive at the 1% level. This suggests that the correlation between carbon finance and the pace of dynamic capital structure adjustment is more pronounced among enterprises with higher debt ratios, thereby confirming H2a. In column (2), the coefficient of GI × TLev is significantly negative, indicating that firms with a low level of green innovation have a slower rate of capital structure adjustment. Meanwhile, the coefficient of GI × CF × TLev is significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating that the effect of carbon finance on the rate of capital structure adjustment is stronger in firms with low levels of green innovation, thereby confirming H2b. Overall, these results suggest that a mismatch in credit resources in traditional finance decreases the speed of enterprise capital structure adjustment. However, carbon finance can alleviate this mismatch, thereby increasing the speed of capital structure adjustment in over-indebted enterprises and in enterprises with low levels of green innovation.

Table 9.

Cross-sectional test results.

To more intuitively show the results of the cross-sectional test, this study presents Figure 4. It depicts the speed of capital structure adjustment (λ) of enterprises with different characteristics under various levels of carbon finance development. The low (0.335) and high (0.556) dividing points on the horizontal axis correspond to the 25th and 75th percentiles of CF in the sample, respectively. This makes it convenient to examine the marginal effect of CF from low to high levels. As the blue and red lines in Figure 4 show, high-debt enterprises (red line) are more sensitive to the development level of carbon finance (slope is 1.044), while low-debt enterprises (blue line) are much less sensitive (slope is −0.353). This proves that carbon finance development has accelerated the correction process, especially for high-debt enterprises, which have the most serious capital structure imbalance and the most urgent need for adjustment. As shown by the green and orange lines, the adjustment speed of low-green-innovation enterprises (orange line) increases significantly with the development of carbon finance (slope is 0.856). In contrast, the adjustment speed of high-innovation enterprises (green line) increases only slightly (slope = 0.315). These results strongly confirm the hypothesis of this paper: carbon finance provides key financial support to enterprises with weak green innovation capabilities that face financing discrimination. This support addresses the shortcomings of the traditional credit system and significantly speeds up the adjustment of enterprises’ capital structures.

Figure 4.

Cross-sectional analysis: Line chart showing the adjustment speed (λ) of different groups. The red dashed lines indicate the 25th (0.335) and 75th (0.556) percentiles of carbon finance in the sample.

5.4. Mechanism Test

This study argues that carbon finance eases financing constraints and improves financing availability for enterprises. Moreover, it improves the supervisory ability of financial institutions and reduces financing costs for enterprises. This, in turn, reduces the cost of adjusting the capital structure and the deviation from the target capital structure. To further verify the theoretical logic of this study and analyze how carbon finance affects the dynamic adjustment of corporate capital structures, this section conducts an empirical analysis based on models (12) and (13). The regression results are shown in Table 10.

Table 10.

Mediating effect.

The mechanisms for analyzing financing constraints are presented in columns (1) to (3) of Table 10. In column (1), the coefficient of CF is significantly negative at the 1% level, indicating that carbon finance significantly reduces financing constraints for enterprises. In column (2), the coefficient of KZ × TLev is significantly negative, indicating that the higher the level of financing constraints for enterprises, the slower their capital structure adjustment. The proportion of the mediating effect in the total effect was 2.10%. In column (3), the coefficient of KZ is significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating that the greater the financing constraints on enterprises, the greater the deviation from their target capital structure. The proportion of the mediating effect in the total effect was 9.17%. These results demonstrate that carbon finance accelerates the adjustment of corporate capital structures and reduces the deviation from target structures by alleviating corporate financing constraints, thereby confirming H3a.

The mechanisms for analyzing financing costs are presented in columns (4) to (6) of Table 10. In column (4), the CF coefficient is significantly negative at the 1% level, indicating that carbon finance reduces firms’ financing costs. In column (5), the Cost × Lev coefficient is significantly negative, indicating that firms’ financing costs reduce the speed of their capital structure adjustment. The proportion of the mediating effect in the total effect is 1.87%. In column (6), the coefficient of cost is significantly positive at the 1% level, indicating that the greater the cost of corporate finance, the greater the deviation from the target capital structure. The proportion of the mediating effect in the total effect was 8.64%. These results demonstrate that carbon finance accelerates the adjustment of firms’ capital structures and reduces deviation from the target capital structure by lowering financing costs, thereby confirming H3b.

6. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

6.1. Conclusions

In the context of global climate governance and the shift towards a low-carbon economy, carbon finance is a trading and investment activity based on “carbon emission rights” and their derivatives. It has emerged as a key market-driven tool.

Carbon finance is a market-based environmental regulation that promotes green and inclusive economic development by reshaping the financial system. The growth of carbon finance is closely linked to the carbon finance market, primarily involving the secondary market for trading carbon emission rights. This policy would lead to a comprehensive green upgrade of the industrial chain, infusing sustainable green energy into the macroeconomy. However, the significant impact of carbon finance on microenterprises, particularly on their financial decision-making processes, has not been adequately explored. This study addresses this important gap in the literature by constructing a provincial carbon finance development index and employing a dynamic partial adjustment model to systematically examine the relationship between carbon finance and the adjustments of capital structure regarding the speed of adjustment and the deviation from the target of A-share-listed companies of China for the period 2014–2024. The empirical results show that carbon finance has a significant incentivizing effect on the optimization of their financial structure. These conclusions withstand the most stringent tests of robustness when employed with the instrumental variables (IVs) and substitution variable methods, thus confirming their reliability. The analysis brings out the following important results:

- (1)

- The main conclusion of the study is that the impact of carbon finance speeds up the adjustment of companies’ capital structure to reach target leverage ratios while diminishing the extent of deviation from such goals. This suggests that carbon finance improves the efficiency of corporate financing, thereby enabling companies to maintain a capital structure in accordance with long-term objectives of value maximization.

- (2)

- Cross-sectional test: The impact of carbon finance varies among different enterprises, mainly reflected in two types of companies—those with various levels of green innovation and those with varying levels of debt. This variation reveals that carbon finance is addressing the inefficiencies of traditional credit allocation. It directs credit toward companies that truly need sustained financing—especially those with low levels of green innovation and high debt—accelerating the dynamic adjustment of the capital structure of these two types of enterprises.

- (3)

- Test of mechanism: Financing constraints and the financing cost mechanism were tested. Our empirical research shows that carbon finance will affect capital structure through two channels: first, the reduction in financing constraints and the acceleration of corporate capital structure adjustment can be obtained through the optimization of financing channels and the added convenience of financing; second, the financing cost caused by friction is reduced, and the endogenous motivation of enterprises to actively and rapidly adjust capital can be improved.

6.2. Policy Recommendations

Based on these findings, we have formulated the following specific policy recommendations.

Carbon finance should be treated by governments and regulatory authorities as a core market instrument for high-quality sustainable economic growth. Support for carbon markets widen policy coverage. At the micro level, studies suggest that policy forms should take appropriate, differentiated incentives and constrain policies [65]. The heterogeneity effects identified by these studies scientifically justify the adoption of these ‘tailor-made’ approaches. Governments should set up bespoke support schemes [66]. For companies facing high debt pressure and weak levels of green innovation, more structurally adaptable institutional arrangements and transitional support should be provided to ensure resources flow to the enterprises that need them most. At the same time, based on the development stage of carbon finance and each region’s resource endowments, a regional, step-by-step development strategy should be implemented, encouraging areas with mature conditions to explore first while strengthening policy support and capacity building for lagging regions.

Financial institutions should actively integrate carbon finance into their core businesses, prioritizing companies with higher debt ratios and lower levels of green innovation as key service targets. By optimizing evaluation and service processes, they can more effectively meet these companies’ financing needs. At the same time, the provincial-level carbon finance development index constructed in this study reveals significant regional heterogeneity. Financial institutions should leverage this geographic pattern by deepening product and service innovation in areas with higher index values while focusing on market cultivation and capacity building in relatively underdeveloped regions, implementing differentiated regional strategies.

Enterprises themselves also must fundamentally improve the enterprise managers’ understanding of carbon finance, redefining carbon finance from a passive cost to something positive, a reduction in operational and compliance costs in the enterprises. Instead of a policy burden or compliance cost, the basis of carbon finance becomes a clear strategic tool for enterprises to gain a competitive advantage in a low-carbon world. Development of carbon markets and good carbon asset management becomes a way to create trading profits and reduce compliance costs directly, and in addition, it sends a message to the larger markets that the enterprise is focused on sustainable development strategies and good governance practices. This signaling will improve corporate valuation and attract long-term investors [67].

It is essential for a better understanding of the actual role of carbon finance for microenterprises in the economic system, thus enabling policy-makers to promote help measures for the microenterprises with even more targeted impact. It is these support measures that can enhance the sustainable development capacity of microenterprises and demonstrate the role of carbon finance in macroeconomic growth. Since the change in the dynamic adaptation of the capital structure is an act of free choice of firms, it is of great benefit in terms of the overall advantage of improving efficiency for the allocation of social resources conducive to the improvement of risk resistance of the economic system. This adjustment is a necessary measure for the firms to overcome the effects of carbon finance. For this reason, we are convinced that cooperation between governmental authorities, financial institutions, and firms can improve the carbon finance system, thereby inducing a greater number of enterprises to participate in green innovation. This will lead to qualitatively better economic growth.

This study examines the impact of carbon finance on micro-level enterprises from a dynamic perspective. Yet, it still falls short of outlining the capital structure adjustment process and provides only a partial picture of carbon finance’s influence on firms. Future research will explore this topic from multiple angles, including corporate investment and financing behaviors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.T. and Y.Z.; methodology, X.W.; software, X.T. and X.W.; validation, X.W.; formal analysis, Y.Z.; investigation, X.W.; resources, X.W.; data curation, X.T. and Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z. and S.M.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z.; visualization, Y.Z. and X.W.; supervision, X.T. and Y.Z.; project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Su, L.; Yu, W.; Zhou, Z. Global trends of carbon finance: A bibliometric analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Li, Y. Carbon finance and carbon market in China: Progress and challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 214, 536–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.; Nie, J.; Zhan, H. The impact of carbon emissions trading on the profitability and debt burden of listed companies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callon, M. Civilizing markets: Carbon trading between in vitro and in vivo experiments. Account. Organ. Soc. 2009, 34, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felli, R. On climate rent. Hist. Mater. 2014, 22, 251–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridge, G.; Bulkeley, H.; Langley, P.; Veelen, B.V. Pluralizing and problematizing carbon finance. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2020, 44, 724–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Niu, H.; Ru, Y.; Tong, A.; Wang, Y. Can carbon finance promote high quality economic development: Evidence from China. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraro, C.; Favero, A.; Massetti, E. Investments and public finance in a green, low carbon, economy. Energy Econ. 2012, 34, S15–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobetz, W.; Wanzenried, G. What determines the speed of adjustment to the target capital structure? Appl. Financ. Econ. 2006, 16, 941–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.O.; Tang, T. Macroeconomic conditions and capital structure adjustment speed. J. Corp. Financ. 2010, 16, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztekin, Ö.; Flannery, M.J. Institutional determinants of capital structure adjustment speeds. J. Financ. Econ. 2012, 103, 88–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, Y.; Kashiramka, S.; Singh, S. Economic Policy Uncertainty and Leverage Dynamics: Evidence from an Emerging Economy. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2021, 77, 101836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.M.; Zhang, W.J. Research on industrial carbon emissions and emission reduction mechanisms under carbon trading in China. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2017, 27, 141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.L.; Zhang, X.C.; Liu, Y. Has China’s carbon trading policy delivered an environmental dividend? Econ. Rev. 2018, 6, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.Y.; Wang, Y. The Economic Dividend Effect of a Tradable Policy Mix of Energy Usage Rights and Carbon Emission Rights. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2019, 29, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.J.; Duan, M.S.; Zhang, P. Analysis of the impact of China’s emissions trading scheme on reducing carbon emissions. Energy Procedia 2019, 158, 3596–3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.G.; Wang, J. Spatial Emission Reduction Effects of Carbon Emission Trading in China: Quasi-Natural Experiments and Policy Spillovers. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2021, 19, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modigliani, F.; Miller, M.H. The cost of capital, corporation finance and the theory of investment. Am. Econ. Rev. 1958, 48, 261–297. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, E.O.; Heinkel, R.; Zechner, J. Dynamic capital structure choice: Theory and tests. J. Financ. 1989, 44, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titman, S.; Wessels, R. The determinants of capital structure choice. J. Financ. 1988, 43, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.R.; Harvey, C.R. The theory and practice of corporate finance: Evidence from the field. J. Financ. Econ. 2001, 60, 187–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lööf, H. Dynamic optimal capital structure and technical change. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2004, 15, 449–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titman, S.; Tsyplakov, S. A dynamic model of optimal capital structure. Rev. Financ. 2007, 11, 401–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, R.; Ju, N.; Leland, H. An EBIT-based model of dynamic capital structure. J. Bus. 2001, 74, 483–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, M.T.; Roberts, M.R. Do firms rebalance their capital structures? J. Financ. 2005, 60, 2575–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harford, J.; Klasa, S.; Walcott, N. Do firms have leverage targets? Evidence from acquisitions. J. Financ. Econ. 2009, 93, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korajczyk, R.A.; Levy, A. Capital structure choice: Macroeconomic conditions and financial constraints. J. Financ. Econ. 2003, 68, 75–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]