Abstract

Both governments and businesses globally are realizing the importance of treating environmental management and protection programs as ongoing efforts that go beyond their immediate operations. However, past initiatives to improve the impact of these programs have faced setbacks due to growing environmental challenges. In this direction, the current study aims to develop a research model that examines the interplay between green supply chain management (GSCM), intellectual capital (IC), corporate social responsibility (CSR), and sustainable performance (SP) within Saudi Arabia’s drilling sector. Additionally, it examines the mediating roles of IC and CSR. Contextualized within the Saudi Vision 2030 framework, which emphasizes sustainability and industrial advancement, this study utilized a quantitative approach by applying structural equation modeling (SEM) to analyze survey data from 334 employees in the Eastern Region’s drilling industry. The findings indicate that GSCM significantly enhanced SP, IC, and CSR. Furthermore, CSR demonstrated a positive impact on both SP and IC and, crucially, significantly mediated the positive relationship between GSCM and SP. Conversely, IC, while positively influenced by GSCM and CSR, did not show a significant direct impact on SP, nor did it act as a significant mediator in the GSCM-SP linkage in this context. This research highlights the prominent role of CSR in translating GSCM practices into holistic performance improvements within this industrial setting. It suggests that firms seeking to maximize the benefits of GSCM should strategically embed these initiatives within a robust and visible CSR strategy to effectively meet stakeholder expectations and drive sustainable performance aligned with national goals.

1. Introduction

Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 is a strategic initiative to fundamentally transform the country’s economic framework. A key aspect of this vision involves revitalizing the industrial sector, including critical operations within the drilling field. This focus on supply chain modernization serves a crucial dual purpose under Vision 2030: firstly, driving economic diversification, and secondly, embedding national sustainability objectives into industrial operations. Within the crucial drilling sector’s supply chain, the push for economic diversification is powerfully demonstrated through initiatives such as the IKTVA program (which aims to increase local content by 70%) [1]. Concurrently, Saudi Vision 2030’s emphasis on environmental stewardship necessitates the adoption of GSCM practices. This convergence of ambitious localization mandates and sustainability goals creates a dynamic context within the drilling sector, potentially leading to both synergies and tensions in green supply chain strategy and operations [2].

This study is conducted in Saudi Arabia, an economy that represents the typical challenges and opportunities inherent in emerging markets. Characterized by a strategic pivot from the natural oil business to a more sustainable one [3], the Saudi context serves as a critical case study for examining the dynamics of sustainability transitions. However, the challenges often faced by emerging economies are distinct from those of developed economies that proactively drive GSCM for sustainable development goals; underdeveloped institutional frameworks, a constantly changing environment, and significant resource constraints characterized by cost-driven rather than green motivations are among the issues faced by emerging economies [4,5]. While the growth potential is a critical measure to characterize an emerging economy, it is also fundamental to equip strong institutions with policy and strategic resources that facilitate efficient business operations [6]. Conversely, the Saudi economy possesses unique advancements, such as political and economic reform, huge investment in the industrial sector, and adoption of cutting-edge technologies, as embodied by Vision 2030 and programs such as IKTVA [7]. While previous studies, such as [4,5], were mainly conducted in other emerging markets, such as the UAE and Vietnam, which share similar challenges in GSCM implementation, the specific drivers, strategic contexts, and other contextual factors vary. As argued in [8], a comprehensive understanding of emerging markets is lacking, necessitating further rigorous research for clarity. To this end, further empirical evidence investigating the pathways from GSCM to SP in the Saudi economy, specifically the drilling sector, is imperative to provide new insights and robust conceptual understanding for sustainable transition management in emerging economies.

GSCM is a proactive strategy aimed at improving the environmental sustainability of both operations and products. While early perspectives often emphasized GSCM primarily for compliance with standards and regulations [9], the concept has evolved into a proactive, strategic approach. Contemporary views recognize GSCM not only for its environmental benefits but also as a critical driver for achieving a competitive advantage, generating cost savings, improving overall performance, and creating long-term value for companies [10,11]. Because of its influence on different business aspects, from acquiring raw materials to reaching the final consumer, GSCM has become a significant topic in academic discussions [12,13].

Sustainable performance (SP) refers to an organization’s ability to achieve its business goals and increase long-term shareholder value by integrating economic, environmental, and social opportunities into its business strategies and operations [14]. The rising concern for sustainability has spurred significant research into the incorporation of eco-friendly and socially responsible practices within supply chain management [15,16]. To enhance sustainability, numerous companies have implemented more environmentally friendly activities in their supply chains. These activities involve performing environmental assessments, launching certification programs, assisting suppliers with their environmental projects, and promoting teamwork in sustainability initiatives [17].

In the environmental management context, IC refers to the total knowledge and expertise that a company utilizes in its processes and activities focused on organizational and ecological concerns [18,19]. Prior research has emphasized IC’s crucial and beneficial role in strengthening resources that contribute to establishing sustainable competitive advantages and boosting overall organizational performance [20,21]. Companies’ effective utilization of their employees’ knowledge and skills, along with the strategic management of their intellectual assets, boosts their capacity for innovation [18]. However, the function of IC extends significantly beyond the firm’s internal boundaries. It is also critical for effectively managing relationships with external stakeholders, enabling the necessary exchange of environmental information, and navigating external pressures, such as international environmental regulations and heightened consumer environmental awareness.

A critical perspective for understanding the broader context of corporate responsibilities is provided by Stakeholder Theory. Originating from the seminal work of [22], this theory challenges the traditional shareholder-centric view, arguing instead that organizations must manage their relationships with a wide array of groups—stakeholders—who can affect or are affected by the achievement of the firm’s objectives. These stakeholders typically include employees, customers, suppliers, financiers, communities, governmental bodies, and environmental advocates [23]. The theory suggests that long-term organizational success and value creation are intrinsically linked to a firm’s ability to effectively address and balance the often diverse interests and concerns of various stakeholders [24]. In the context of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, with its strong emphasis on economic diversification, environmental sustainability, social well-being, and localized supply chains (e.g., the IKTVA program), engaging constructively with stakeholder expectations is paramount. Therefore, Stakeholder Theory offers a compelling rationale for why firms increasingly adopt practices such as GSCM and engage in CSR, as these actions often represent direct responses to stakeholder pressures and expectations regarding environmental and social issues, ultimately contributing to the firm’s legitimacy and sustainable performance [25].

CSR encompasses a company’s commitment to operate ethically and contribute to sustainable development by considering its impact on society and the environment, often beyond mere legal compliance [13]. While CSR initiatives can lead to beneficial outcomes, such as enhanced reputation and stakeholder satisfaction [26,27], the core of CSR involves distinct areas of accountability. This responsibility extends to relationships with various stakeholders, including those within the supply chain. Conceptually, this study focuses on assessing these responsibilities through the three pillars of sustainability: environmental responsibility (EnvR) (e.g., minimizing pollution, sustainable resource use), social responsibility (SR) (e.g., fair labor practices, community engagement, ethical conduct), and economic responsibility (EcoR) (e.g., financial transparency, ethical governance contributing to long-term viability) [17,28,29]. Recent studies have reaffirmed that GSCM significantly improves sustainable performance dimensions (economic, environmental, and social) when mediated by constructs such as CSR and IC. For example, in ref. [30], the authors find that GSCM enhances operational, social, and economic outcomes through integrated practices in the Saudi industrial sector. Another study shows that human capital, a component of IC, is a strong predictor of sustainable financial performance [31]. Research in other countries also suggests that different kinds of IC (structural, relational, human) vary in their mediating strength in GSCM linkages [32,33]. These studies provide a foundation for comparing the strength and role of CSR versus IC as mediators in the drilling context, an area that remains underexplored.

The Resource-Based View (RBV) offers a foundational theory for how firms achieve sustained competitive advantage, positing that this advantage derives from controlling resources and capabilities that are valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable (VRIN) [34,35]. While individual green practices or resources might sometimes be replicated, achieving sustained competitive advantage often stems from the complex, synergistic integration of multiple GSCM practices into the firm’s unique configuration of intellectual capital. This intricate system-level capability is far more difficult for competitors to understand and imitate. Applied to GSCM, the RBV suggests that developing and implementing green practices can create unique organizational capabilities that enhance environmental and overall performance [36]. Crucially, the RBV considers all valuable firm resources, including intangible assets. This integrated RBV perspective provides holistic grounding, suggesting that both GSCM capabilities and the enabling IC assets contribute to competitive advantage and improved performance when they possess VRIN attributes. Indeed, numerous researchers leverage the RBV to investigate how green initiatives and capabilities serve as strategic assets driving improvements [37,38,39].

This study employs both the Resource-Based View and Stakeholder Theory as a theoretical framework. The RBV emphasizes how GSCM and IC serve as strategic assets that drive SP, whereas Stakeholder Theory underlines the role of CSR in meeting stakeholder demands and securing legitimacy. By integrating these perspectives, the current study offers a dual lens that connects internal resources with external stakeholder expectations to explain sustainable performance in Saudi Arabia’s drilling industry. In addition, testing IC and CSR simultaneously as parallel mediators is critical because they reflect alternative mechanisms—internal capability building versus external stakeholder alignment—and are complementary pathways.

While the strategic importance of GSCM is increasingly acknowledged, fully understanding its performance implications remains complex [40]. Rather than suggesting a uniformly weak or uncertain connection, the extant literature indicates that the relationship between GSCM practices and firm performance tends to be highly context-dependent, varying significantly across different industries, regulatory environments, and geographical regions [11,41,42]. Consequently, a key research challenge lies not just in determining whether GSCM impacts sustainable performance but also in elucidating the underlying mechanisms and contingent conditions that shape this relationship. Furthermore, there is a pronounced need for such investigations within the specific context of the Saudi Arabian oil and gas industry, particularly the drilling sector, where empirical research detailing GSCM’s precise performance linkages is still developing [43]. IC’s mediating role may clarify why some studies that examine only the direct link between GSCM and SP report inconsistent results, as they potentially overlook the crucial intermediate step of capability development facilitated by IC [21]. Although prior research globally may have explored the mediating roles of factors such as IC or CSR individually in connecting GSCM to performance outcomes, a notable gap persists regarding the simultaneous mediating influence of both these factors. This focus is chosen while acknowledging that the broader literature explores other potential intervening variables, such as green innovation, organizational learning, and technological capabilities, further highlighting the complexity of the GSCM–performance relationship [44]. This study therefore offers a new assumption that GSCM influences sustainable performance mainly through two mediators—CSR and IC—which vary in their strength and role within Saudi Arabia’s drilling sector.

This study addresses the gaps identified in the existing literature by contributing in two key ways. First, it investigates the link between GSCM and SP. Second, it uncovers the mediating influence of IC and CSR on the relationship between GSCM and SP, specifically within the drilling sector in Saudi Arabia. Additionally, this research provides valuable insights for the Saudi oil industry, offering recommendations to improve SP by implementing effective GSCM practices, while considering the mediating roles of IC and CSR. Given the lack of exploration regarding these dual mediating roles in the current literature, it is crucial to reassess and redefine our understanding of the connections between GSCM, SP, IC, and CSR. This study aims to enhance the understanding of GSCM by addressing the following research questions (RQs):

- What is the relationship between GSCM and SP?

- How do IC and CSR mediate the relationship between GSCM and SP?

To provide a clear structure, this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 covers the literature review, theoretical framework, and hypothesis development; Section 3 presents the study’s methodology; Section 4 presents the study analysis and results; and Section 5 discusses the results and their implications.

2. Review of Literature

2.1. Green Supply Chain Management

GSCM is broadly defined as the integration of environmental considerations into all supply chain activities, from sourcing and manufacturing to distribution and end-of-life product management [45,46]. Interest in GSCM has grown significantly over the last two decades, reflected in a substantial increase in related publications [21,41,42,43,44,45,46,47], highlighting its importance in modern business. The adoption of GSCM is increasingly driven by external pressures, including heightened customer demand for sustainable products and stringent government environmental regulations [48]. Successfully implementing GSCM yields considerable benefits, offering the potential not only to improve environmental, economic, and operational performance but also to significantly enhance a company’s reputation, competitive advantage, and market visibility [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. While GSCM encompasses a wide array of practices, such as eco-design and stakeholder collaboration [50], GSCM, in the current study, focuses on four components extensively discussed in the literature: green procurement (GP), green manufacturing (GM), green logistics (GL), and reverse logistics (RL) [49,51,52,53].

GM represents a core internal GSCM practice, focusing on production processes that minimize environmental impact and optimize resource efficiency [54]. Implementing GM can help organizations address environmental regulations, enhance their public image, achieve cost savings via efficiency, and contribute to ecological sustainability [55]. However, implementing GM is not without its challenges, often involving substantial initial investments in cleaner technologies or process redesigns, potential operational disruptions during transition, complexity in re-engineering systems, and the need for specialized employee skills or training [55]. A major advantage of green manufacturing is its potential to significantly improve operational efficiency and lower production costs through reduced energy consumption, minimized waste generation, and optimized material usage [56]. Consistent with these principles, the GM framework in this study considers aspects such as substituting hazardous materials, implementing energy efficiency initiatives, controlling emissions, and minimizing noise pollution [52,53].

GP is conceptualized as aligning procurement activities with environmental objectives, emphasizing waste reduction, recycling, and the use of sustainable materials [57]. It aims to conserve resources, protect ecosystems, prevent pollution, reduce energy and water consumption, and minimize waste [58]. A primary challenge associated with GP is the often-higher initial purchase price of environmentally preferable products and the potential difficulty in finding suppliers who meet specific green criteria [59]. GP can significantly enhance an organization’s corporate image and competitiveness by signaling strong environmental responsibility to customers, investors, and other stakeholders [59]. Within this study’s framework, GP encompasses collaborating with suppliers on environmental goals, specifying requirements for sustainable materials, conducting supplier environmental audits, and selecting suppliers based on ecological criteria [52,53].

GL involves sustainable policies, practices, and technologies aimed at mitigating the environmental footprint of moving, storing, and managing goods [60]. In other words, GL seeks to reduce the negative ecological impacts of transportation, warehousing, inventory management, distribution, and packaging [61]. A significant disadvantage often associated with implementing green logistics initiatives is the substantial initial financial investment in acquiring eco-friendly transport fleets, advanced route optimization technologies, and sustainable warehouse infrastructure [61]. Therefore, relevant practices include ensuring loading and unloading safety, as they prevent disruptions, minimize damage-related waste, and support the smooth, resource-efficient flow of goods throughout the supply chain [51]. Based on these concepts, the GL framework here includes environmentally friendly transportation management, green packaging solutions, and energy/resource efficiency improvements in warehousing and distribution [51].

RL focuses on planning, implementing, and controlling the efficient flow of products, materials, and information from consumption back to the origin or point of disposal to capture value or ensure proper handling [62]. Effective RL capabilities enable companies to manage product end-of-life, recover value, comply with regulations (e.g., take-back mandates), and handle recalls efficiently [63]. It can also lead to cost savings, new revenue streams, and improved customer loyalty [64]. A key disadvantage of reverse logistics is its inherent complexity and unpredictability regarding the volume, timing, and condition of product returns, which significantly increases management challenges and operational costs compared to traditional forward logistics [65]. This study’s RL component emphasizes managing return processes, value recovery operations (recycling, remanufacturing), and environmentally sound disposal [49].

2.2. Sustainable Performance (SP)

SP reflects an organization’s overall long-term health and value generation, assessed holistically across multiple dimensions. It moves beyond pure financial metrics to incorporate environmental and social considerations, guided by the principle of creating lasting value for a broad range of stakeholders [66]. The assessment of SP has become increasingly critical for investors, consumers, and regulators evaluating a company’s long-term viability, resilience, and ethical standing [67]. Accurately measuring SP across its interrelated dimensions presents complexities, requiring diverse frameworks and indicators [68]. In this study, SP is viewed from three aspects: environmental performance (EnvP), social performance (SocP), and economic performance (EcoP) [69,70].

EnvP reflects an organization’s effectiveness in navigating its relationship with the natural environment [71]. It signifies a commitment to ecological stewardship, aiming to reduce pollution, conserve vital resources such as energy and water, minimize waste generation, and protect biodiversity [72]. Robust EnvP is crucial, as it helps organizations comply with environmental regulations and enhance their reputation and stakeholder trust, often leading to operational efficiencies and cost savings. However, achieving superior EnvP also involves challenges, such as the potential need for substantial upfront investment in greener technologies or processes, the complexity of accurately measuring certain environmental impacts, and potential trade-offs with short-term economic objectives. In sustainability assessments, EnvP is often operationalized through indicators such as reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, decreased consumption of hazardous or toxic materials, improvements in waste reduction and recycling rates, and mitigation of environmental accidents or spills [69,70].

SocP defines how effectively an organization manages its relationships with and impacts on its diverse stakeholders, including employees, customers, suppliers, and the wider community [73]. The importance of strong SocP is substantial: it can significantly enhance employee morale, attraction, and retention; build brand reputation and customer loyalty; strengthen community relations (improving the social license to operate, which is particularly pertinent in Saudi Arabia’s community-focused context and alignment with Vision 2030’s quality of life goals [2]); and mitigate social and reputational risks. SocP emphasizes ethical conduct, social equity, and responsible value delivery, encompassing crucial areas such as fair labor practices, human rights, occupational health and safety, positive community engagement, and value delivered responsibly throughout the chain [26]. However, achieving and demonstrating high SocP faces challenges, notably the difficulty in quantifying often intangible social impacts; the potential costs associated with robust social programs, fair wages, and ethical sourcing; and the complexity of navigating diverse, sometimes competing, stakeholder expectations across different cultural contexts. In practical assessments, SocP is often evaluated using specific factors or indicators, such as employee satisfaction and safety metrics, measurable contributions to stakeholders’ quality of life, investments in workforce training and development, and demonstrated support for community initiatives [69,70,74].

EcoP addresses an organization’s financial health and its capacity to generate economic value sustainably over the long term, without undermining environmental or social integrity [75]. This dimension focuses on enduring financial stability, operational efficiency, competitive market standing, and long-term value creation within ecological and social boundaries [76]. Strong EP is fundamental in providing the financial resources necessary for reinvestment in environmental and social initiatives, fostering innovation, and ensuring organizational longevity [77]. The primary challenge associated with EP within a sustainability framework involves effectively navigating the inherent tension between optimizing short-term financial results and making the necessary long-term investments in environmental protection and social equity, alongside the difficulty in accurately quantifying the direct economic returns derived from these sustainability commitments. Within a sustainability context, EcoP assessment may include traditional financial metrics alongside sustainability-influenced economic indicators, such as cost reductions from waste treatment or resource efficiency (e.g., energy consumption value added, material purchasing costs) or mitigation of environmentally related costs (e.g., waste discharge fees) [69,70,78].

2.3. Intellectual Capital (IC)

IC refers to the collective intangible assets of an organization, encompassing the knowledge and expertise of its employees, its internal processes and systems, and its valuable external relationships, which together drive value creation and competitive advantage [79]. The importance of IC is substantial, as it constitutes the vital repository of organizational knowledge essential for driving sustainable competitive advantage, enhancing innovation capabilities, improving the quality of strategic decision-making, and ultimately boosting overall corporate performance [79]. Despite these significant benefits, organizations face notable challenges in managing IC effectively, primarily stemming from the inherent difficulties in accurately measuring and valuing these intangible assets, mitigating the risks of knowledge loss (e.g., through employee turnover impacting human capital), and efficiently codifying tacit knowledge into accessible structural capital [80,81]. In the contemporary business landscape, in which sustainability initiatives are strongly emphasized globally and within Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, the application of core IC principles is increasingly directed towards achieving environmental objectives, giving rise to the growing strategic importance of IC for sustainable value creation and environmental management. IC will be explored from three aspects: green human capital (GHC), green structural capital (GSC), and green relational capital (GRC) [82].

GHC defines the collective environmental knowledge, skills, abilities, attitudes, and commitment possessed by employees, which organizations can strategically leverage to achieve their sustainability objectives [83,84]. It underscores the vital role of human resource management in actively fostering environmental sustainability by developing specific green competencies in employees, promoting environmental awareness and values (often through targeted training and consistent internal communication), and encouraging the adoption of pro-environmental behaviors within daily work routines [85,86]. The importance of investing in GHC is widely acknowledged in contemporary research [20,82]. It is recognized for significantly enhancing organizational environmental performance, boosting green innovation capacity, and enabling deeper integration of sustainability principles into core operations [19,82]. However, cultivating a strong GHC base presents distinct challenges, including the potentially significant costs and time investment required for specialized green training and development, difficulties in shifting deeply ingrained employee attitudes or behaviors towards environmental responsibility, complexities in accurately measuring acquired green competencies, and the ongoing challenge of attracting and retaining specialized green talent [82], particularly within competitive or rapidly transforming economic environments such as that of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030.

GSC constitutes the non-human, organizational dimension of IC, defining the codified knowledge, established systems, operational routines, databases, supportive organizational culture, and physical infrastructure that collectively institutionalize environmental management within a company [83]. This typically encompasses assets such as formal environmental management systems (EMSs, e.g., the increasingly adopted ISO 14001 standard), green IT solutions, documented environmental operating procedures, patents for green technologies, and facilities designed or retrofitted for resource efficiency [87,88]. The importance of developing robust GSC is particularly pronounced in Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, where achieving sustainability goals and demonstrating adherence to international environmental standards are key strategic priorities for many organizations. Strong GSC enables the standardization of green practices, enhances environmental monitoring and reporting capabilities vital for governance, improves resource efficiency contributing to economic diversification, reliably translates environmental strategy into consistent operational actions [83,84,85,86,87,88], and fosters more predictable environmental outcomes [87]. However, building and maintaining effective GSC presents significant challenges, including the often substantial upfront financial investments required; the considerable time and resources needed for system development, documentation, and implementation; the potential risk of creating overly rigid systems that might stifle necessary operational agility; and the difficulty of ensuring these structures move beyond formality to become genuinely embedded within the daily organizational culture. Critically, in a dynamic environment such as Saudi Arabia’s, GSC demands continuous updating to remain effective and compliant with potentially evolving environmental regulations and technological advancements spurred by ongoing development initiatives. This study operationalizes GSC through key sub-variables: the maturity and effectiveness of existing environmental management systems, the adoption and quality of environmentally friendly facilities and infrastructure, and the extent to which formal environmental procedures are documented and consistently implemented [82].

GRC defines the value generated from an organization’s network of relationships with key external stakeholders, including customers, suppliers, local communities, partners, and regulatory bodies, specifically concerning environmental matters and shared sustainability objectives [83]. This capital resides fundamentally in the quality of these connections, encompassing mutual understanding on green issues, established trust, collaborative potential that can fuel eco-innovation, and the organization’s overall green reputation and credibility within its operating environment [88]. The importance of actively cultivating strong GRC is increasingly critical for organizations navigating the business landscape in Saudi Arabia. It facilitates access to vital external knowledge and partnerships for eco-innovation aligned with Vision 2030 goals. It significantly enhances stakeholder trust and the crucial social license to operate within local communities, improves positioning in rapidly developing green markets, fosters the deeper supply chain collaboration needed for both domestic growth and international competitiveness [88], and ultimately contributes to building resilient and respected green brand identities [83]. However, developing and maintaining high-quality GRC presents distinct challenges, such as the significant ongoing investment of time and resources required for genuine, long-term relationship building, as well as the persistent difficulty of measuring the return on investment from these relational activities [88]. The GRC framework employed in this study is operationalized through highly relevant sub-variables focused on key market relationships, assessing the level and quality of environmental collaboration initiatives with key suppliers and evaluating the intensity and effectiveness of green value communication and collaborative relationships directed towards customers and the wider market [82].

2.4. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

CSR is broadly understood as the voluntary commitment by organizations to integrate social and environmental considerations into their business operations and stakeholder interactions, extending beyond mere legal compliance [89,90]. While numerous frameworks exist, the influential pyramid model [91] conceptualizes CSR in layers—economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic responsibilities—providing valuable context. The importance of engaging in CSR is widely debated but often linked to enhancing corporate image, building trust with stakeholders (employees, customers, communities, investors), attracting talent, and potentially improving long-term financial performance, although research indicates that this link is complex and context-dependent [26,92,93]. Key challenges include navigating the definitional ambiguity of CSR, incurring the potential costs associated with initiatives, effectively measuring the actual impact, and avoiding perceptions of superficial engagement. With Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030, CSR is gaining prominence, with an emphasis on sustainability, economic diversification, social well-being, and increasing stakeholder expectations for responsible corporate conduct. Various empirical studies and meta-analyses indicate a generally optimistic, albeit complex and context-dependent, connection between corporate social performance and financial success [26,93].

Within the CSR framework, EnvR defines a company’s commitment to proactively managing its impact on the natural environment. This involves understanding and mitigating the environmental consequences of business activities [71]. EnvR facilitates compliance with environmental regulations (which are evolving in Saudi Arabia), enables better risk management, drives operational efficiencies through resource conservation (energy, water) and waste reduction, enhances corporate reputation among environmentally conscious stakeholders, and can stimulate green innovation [94,95]. Adopting structured approaches like environmental management systems (EMSs), such as ISO 14001, demonstrates this commitment formally [96]. However, pursuing robust EnvR presents challenges, including the potential costs of pollution control technologies or process changes, difficulties in accurately measuring certain environmental impacts, and managing potential short-term trade-offs with economic performance goals. Typical sub-variables used to assess EnvR include investments in pollution prevention, quantifiable reductions in emissions and waste, resource conservation metrics (energy/water efficiency), adoption of a certified EMS, and development of greener products/services [28,41,46].

SR defines how a company manages its relationships with and impacts on its various social stakeholders, emphasizing ethical behavior and fairness in all interactions [97]. Key stakeholders typically include employees, customers, suppliers, and the local communities where the organization operates. The importance of SR is significant for building long-term value: it can enhance employee morale, engagement, attraction, and retention [98]; build customer loyalty among socially conscious consumers [27]; strengthen community relations; and, crucially, foster more stable and ethical supply chains [99]. Key challenges involve the costs associated with fair labor practices, health and safety investments, and community programs [100]. Common sub-variables for assessing SR include fair labor practices (wages, working conditions, diversity/inclusion—e.g., valuing the contributions of disabled people); investments in employee health, safety, and development; ethical treatment of customers; community engagement and investment programs (e.g., employee volunteering support); and responsible supply chain practices [29,101].

In a CSR context, EcoR defines a company’s duty to be profitable and financially viable while operating ethically and contributing positively to the economy, thereby meeting the expectations of core stakeholders such as shareholders, employees, creditors, and customers [22,92]. The importance extends beyond shareholder returns; a sustainably profitable company provides stable employment, generates tax revenues supporting public services, and possesses the financial capacity to invest in environmental and social initiatives [102]. Fulfilling EcoR contributes directly to national economic goals, such as diversification and stability under Saudi Vision 2030. The primary challenge lies not in profitability itself but in balancing economic objectives with environmental and social stewardship, ensuring ethical financial conduct (transparency, fair competition), avoiding economic harm (e.g., through pollution or unfair labor practices), and contributing equitably to the host economy [14,103]. Key sub-variables reflecting EcoR within CSR often include consistent profitability, ethical financial reporting and governance, job creation and stability, payment of taxes, investment in R&D/innovation, contribution to local economic development (e.g., through local sourcing), and delivery of fair value to customers [17].

2.5. Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis Development

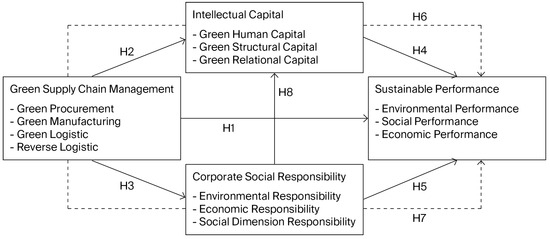

Following the previous discussion of the theoretical background and related literature, this study proposes an integrated model of green supply chain management, intellectual capital, corporate social responsibility, and sustainable performance as independent constructs. Green supply chain management is predicted to influence sustainable performance (dependent construct) through intellectual capital and corporate social responsibility as mediator variables (Figure 1), with each variable representing a specific and important component.

Figure 1.

Research model.

2.5.1. GSCM and SP

The perspective of the RBV argues that GSCM practices represent strategic organizational capabilities [104]. When effectively developed and integrated, these capabilities become valuable, rare, and difficult for competitors to imitate, leading to sustained competitive advantage manifested as improved sustainable performance [61,105]. Implementing GSCM directly targets the EnvP dimension of SP by reducing emissions, conserving resources, and minimizing waste [70]. Furthermore, collaboration with suppliers on environmental and social standards (GP) and community engagement through responsible logistics or take-back programs (RL) contribute positively to SocP. While some studies highlight potential short-term EcoP challenges due to initial investment costs in green technologies and processes [12], the long-term perspective suggests significant economic benefits, including reduced operational costs (energy, materials, waste disposal), enhanced compliance, improved corporate image leading to market advantages, and potential for green innovation, ultimately outweighing initial outlays [106,107]. While many empirical studies and meta-analyses report a positive overall GSCM-SP link [11,61,70], the impact can be context-dependent. Research has shown differential effects, where GSCM might significantly impact operational or economic performance but have non-significant effects on environmental performance in specific contexts [8,108]. Therefore, the positive relationship may not be uniform across all dimensions or contexts. Within Saudi Arabia, the drive towards Vision 2030 sustainability goals and the implementation of programs such as IKTVA, which encourages supply chain localization and efficiency, likely amplify the strategic importance of GSCM. Companies adopting robust GSCM may gain advantages in regulatory compliance, resource efficiency (critical for economic diversification), and stakeholder reputation, thus supporting the hypothesized positive impact on overall SP in this specific context. This study posits a positive relationship between the adoption of GSCM practices and overall SP, encompassing its environmental, social, and economic dimensions. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is proposed:

H1:

GSCM has a positive impact on SP.

2.5.2. GSCM and IC

The implementation of GSCM practices actively contributes to the development of organizational intellectual capital (IC), particularly its green components—GHC, GSC, and GRC. The process of implementing GSCM necessitates organizational learning and the development of new knowledge-based resources. For instance, adopting green purchasing requires buyers to acquire new knowledge about sustainable materials and supplier auditing techniques (enhancing GHC) and build collaborative relationships with suppliers focused on environmental goals (enhancing GRC) [109]. Implementing green manufacturing or reverse logistics often demands new employee skills and environmental awareness (GHC), alongside the development of new operational routines, environmental monitoring systems, and databases (GSC) [110,111]. Having employees engage directly in GSCM activities, such as green audits or cross-functional improvement teams, further develops their environmental competencies and commitment (GHC) [83].

Empirical studies provide support for this causal direction, indicating that comprehensive GSCM adoption correlates with higher levels of GRC within firms [20,112,113]. However, this development is not automatic and faces challenges, notably the significant investments required for specialized training (GHC), green information systems (GSC), and nurturing environmentally focused external relationships (GRC) [107]. Within the Saudi Arabian context, organizations striving to implement advanced GSCM practices to align with Vision 2030 or specific sector requirements (e.g., environmental standards in energy or manufacturing) will inherently need to invest in developing the associated GHC, GSC, and GRC, thus supporting the proposed relationship. Therefore, GSCM implementation acts as a catalyst for knowledge creation and resource development, and, supported by emerging empirical evidence, Hypothesis 2 is proposed.

H2:

GSCM has a positive impact on IC.

2.5.3. GSCM and CSR

It is suggested that adopting GSCM positively influences a firm’s overall CSR profile, as defined by its environmental, social, and economic responsibilities. The primary justification lies in the direct alignment of GSCM with core CSR dimensions. GSCM inherently addresses the environmental responsibility component of CSR by focusing on reducing pollution, conserving resources, and minimizing waste throughout the supply chain [114,115]. This directly responds to the environmental concerns of stakeholders such as customers, regulators, communities, and investors [25]. Furthermore, GSCM practices often incorporate SocR aspects; for example, green purchasing may involve auditing suppliers for fair labor practices alongside environmental criteria [116], and GL might aim to reduce local community disruption or emissions [115,117]. RL programs can also enhance customer well-being through responsible product end-of-life management. GSCM’s focus on efficiency and waste reduction also contributes positively to long-term EcoR by lowering operational costs and enhancing resource productivity [115]. Therefore, GSCM serves as a tangible mechanism through which companies operationalize their environmental and related social commitments, making CSR principles actionable within core business processes [40]. From a stakeholder perspective, visible GSCM initiatives signal a company’s commitment beyond mere compliance, enhancing its overall CSR reputation [25]. In Saudi Arabia, where stakeholder awareness of CSR is growing and Vision 2030 promotes responsible business conduct, implementing GSCM provides credible evidence of a firm’s commitment to environmental stewardship and broader social responsibility, thus strengthening its overall CSR standing. Supported by clear linkages between GSCM activities and the environmental, social, and economic dimensions of CSR, Hypothesis 3 is proposed:

H3:

GSCM has a positive impact on CSR.

2.5.4. IC and SP

This hypothesis posits that a firm’s IC positively influences its multidimensional SP. This relationship is strongly grounded in the RBV [118,119]. IC (comprising GHC, GSC, GRC) represents the specific knowledge assets enabling firms to effectively manage environmental challenges and leverage sustainability opportunities. GHC employees’ environmental skills, knowledge, and commitment drive green innovation, improve environmental management effectiveness, and facilitate stakeholder engagement, positively impacting EnvP and SocP [83,84,85,86]. Through embedded environmental systems, processes, and culture, GSC enables resource efficiency, ensures compliance, standardizes green practices, and supports informed decision-making, contributing primarily to EnvP and EcoP [20,88]. Through strong external relationships focused on sustainability, GRC facilitates access to green markets, fosters collaboration for eco-innovation, and builds trust and reputation, enhancing SocP, EcoP, and potentially EnvP through shared learning [120].

Empirical research largely supports a positive link between IC and various performance outcomes, including SP dimensions [20,83,121]. Importantly, studies suggest that these IC components often act synergistically, producing greater impacts on SP when developed together rather than in isolation [20,122]. However, some nuances should be acknowledged, as some research indicates that the strength of the relationship between specific IC components and individual SP dimensions might vary depending on industry context or strategic focus [123,124]. Mixed findings have been reported in several studies, mainly those conducted in other emerging markets, such as Indonesia. For example, one study [123] revealed that GSC had a significant positive effect on financial performance, and GHC had a negative effect, while GRC was not significant. Another international study conducted in a developed economy found that human and relational capital positively affect performance, but structural capital negatively affects asset growth [124]. Although the RBV suggests that IC should improve SP, the strength of the IC–SP link may depend on contextual contingencies such as industrial context, and the maturity of IC’s activities in a specific business environment might lead to such inconsistent sustainability outcomes. In the Saudi Arabian context, developing IC is vital for companies navigating the transition towards a more sustainable economy aligned with Vision 2030. The required innovation, efficiency improvements, and stakeholder collaboration necessitate strong GHC, GSC, and GRC. Based on the robust theoretical foundation of the RBV and substantial empirical support highlighting IC as critical for achieving sustainability goals, Hypothesis 4 is proposed.

H4:

IC has a positive impact on SP.

2.5.5. CSR and SP

CSR activities help organizations maintain societal acceptance and secure their social license to operate, which is crucial for long-term survival and success [125]. By addressing the needs and expectations of diverse stakeholders (employees, customers, community, investors) through CSR, firms build trust, enhance their reputation, foster cooperation, and ultimately create long-term value, contributing positively to SP [126]. Robust empirical evidence, including from influential meta-analyses, generally supports a positive, albeit complex, relationship between CSR engagement and corporate performance, including financial and non-financial aspects relevant to SP [26,94,127].

The mechanisms linking CSR to SP include enhancing intangible assets such as reputation and brand loyalty [128], attracting and retaining motivated employees [129] (related to SocP), mitigating social and environmental risks [130], and stimulating innovation in sustainable products and processes, which can improve both environmental and economic performance [131,132]. However, it is essential to acknowledge the counterarguments and complexities. Some economic theories argue that CSR, beyond compliance, diverts resources from profit maximization, potentially harming short-term economic performance [133,134]. Research also recognizes potential trade-offs and highlights that the CSR-SP link is often context-dependent, influenced by industry, geography, and firm characteristics [76,135]. In Saudi Arabia, increasing governmental focus (Vision 2030), investor scrutiny, and public awareness likely strengthen the business case for CSR contributing positively to SP by enhancing legitimacy and stakeholder relations. This study proposes that engaging in CSR activities positively influences sustainable performance (SP), which is a central proposition in the CSR literature. Therefore, considering the strong balance of empirical evidence—while acknowledging the complexities—Hypothesis 5 is proposed.

H5:

CSR has a positive impact on SP.

2.5.6. IC Mediates the Relationship Between GSCM and SP

Drawing on the Resource-Based View, GSCM practices might yield some direct operational efficiencies that contribute to SP; their sustained and strategic impact is realized primarily by building valuable, often intangible assets [105,118]. As argued, implementing GSCM necessitates organizational learning, fostering GHC (employee skills/awareness), GSC (systems/routines), and GRC (collaborative relationships). Subsequently, this enhanced IC equips the organization with the necessary capabilities, such as green innovation capacity, enhanced efficiency through embedded knowledge, and stronger stakeholder trust, to achieve superior SP across its environmental, social, and economic dimensions [20,83]. This perspective suggests that IC acts as a crucial mechanism, translating GSCM efforts into holistic SP outcomes. For example, GSCM investments in supplier collaboration (a GSCM practice) build GRC, which then facilitates access to green markets and co-innovation, ultimately improving SP. This mediating role of IC may help explain why some studies focusing solely on the direct GSCM–SP relationship yield inconsistent results, as they potentially overlook the critical intermediate step of capability development through IC [40].

The GSCM- IC relationship is perhaps less frequently emphasized in the literature than the IC -GSCM direction, where existing IC enables GSCM adoption. Empirical studies specifically testing IC as a mediator in the GSCM- SP relationship appear to be less common than those examining alternative pathways, for example, GSCM mediating other factors [136]. While acknowledging the possibility of alternative model specifications (such as IC -> GSCM -> SP), this hypothesis focuses on GSCM implementation as an active driver of necessary organizational learning and capability building. In the Saudi Arabian context, where organizations are rapidly adopting new practices to align with Vision 2030, simply implementing GSCM processes might not produce the desired SP results unless these practices effectively cultivate the underlying GHC, GSC, and GRC to sustain performance in a changing environment. This hypothesis proposes an indirect pathway where the influence of GSCM practices on SP operates significantly through the development of IC. The justification rests on integrating the logic of GSCM’s impact on IC and IC’s influence on SP within the study’s framework. Therefore, based on the theoretical argument positioning IC development as the key mechanism for GSCM’s strategic impact on SP, Hypothesis 6 is proposed.

H6:

IC mediates the relationship between GSCM and SP.

2.5.7. CSR Mediates the Relationship Between GSCM and SP

Another key element of this relationship is corporate social responsibility (CSR), which incorporates GSCM into the framework by tackling environmental, social, and ethical issues. CSR’s ability to mediate this relationship hinges on how well it aligns sustainability objectives with stakeholder expectations [137]. In other words, ineffective execution of CSR strategies can lead to reduced performance. This suggests that GSCM influences SP largely because it enhances the firm’s broader CSR profile, which subsequently drives SP outcomes. The core argument is that GSCM practices serve as highly visible and tangible demonstrations of a company’s commitment to specific aspects of CSR, particularly environmental stewardship [40,114]. As argued, GSCM directly improves the environmental dimension of CSR and often positively influences social aspects (e.g., responsible sourcing, community impact of logistics), thereby contributing to a stronger overall CSR perception among stakeholders [25]. Subsequently, this enhances the overall CSR profile, reflecting a broader commitment to ethical and responsible operations, which builds stakeholder trust, strengthens legitimacy, enhances reputation, and potentially fosters innovation, ultimately leading to improved multidimensional SP [26,126,127]. For instance, the positive effect of reduced emissions due to GSCM on SP is mediated by the improved environmental CSR performance that stakeholders recognize and value.

It is important to address potential model specification concerns. While this hypothesis positions CSR as the mediator, alternative perspectives exist; for example, CSR might be viewed as a driver of GSCM adoption [138], or GSCM itself could be modeled as mediating the effect of broader strategic orientations on performance. However, this hypothesis specifically focuses on the pathway where GSCM’s primary contribution to overall SP comes from bolstering the firm’s total CSR image and performance. In the Saudi Arabian context, where demonstrating credible CSR commitment aligned with Vision 2030 is increasingly important for maintaining stakeholder trust and a positive reputation, concrete actions such as GSCM are vital inputs. The SP benefits may accrue less from the GSCM actions in isolation and more from how these actions collectively enhance the company’s perceived legitimacy and overall CSR profile in the eyes of regulators, investors, customers, and the community. This research proposes that CSR acts as a mediator, channeling the impact of GSCM practices onto overall SP. Based on the reasoning that GSCM enhances key CSR dimensions and that this improved overall CSR profile drives SP via stakeholder responses, Hypothesis 7 is proposed:

H7:

CSR mediates the relationship between GSCM and SP.

2.5.8. CSR’s Impact on IC

This hypothesis posits that engaging in CSR activities fosters the development of a firm’s IC. Implementing CSR programs focused on employee well-being, ethical conduct, or environmental training directly contributes to GHC by enhancing skills, awareness, motivation, and commitment among the workforce [139,140]. Adopting CSR often necessitates developing new organizational structures, management systems (e.g., for sustainability reporting, stakeholder dialogue, ethical audits), and routines and cultivating a supportive organizational culture, thereby building GSC [141]. Furthermore, CSR inherently involves proactive engagement with external stakeholders (customers, suppliers, communities, Non-Government Organizations (NGOs)). These interactions build trust, enhance corporate reputation, foster collaborative networks, and provide valuable external insights and feedback, significantly strengthening GRC [24,142]. CSR can thus be viewed as an investment in intangible assets.

Companies known for strong CSR practices are often perceived as attractive, aiding in attracting and retaining high-quality talent [129]. The processes of addressing complex social and environmental issues through CSR often spur organizational learning, facilitate knowledge sharing across departments, and drive sustainability-focused innovation, further enriching the firm’s overall IC base [143,144]. Empirical studies lend support to this direction, indicating positive associations between CSR engagement or disclosure quality and measures of IC and its components [25]. In the Saudi Arabian context, as companies increasingly undertake CSR initiatives to align with Vision 2030 and meet local expectations, they are concurrently, often implicitly, investing in the development of the GHC, GSC, and GRC needed to execute these initiatives effectively. Based on the logic that CSR necessitates and cultivates knowledge resources, supported by empirical findings, Hypothesis 8 is proposed.

H8:

CSR has a positive impact on IC.

3. Methods, Sample, and Materials

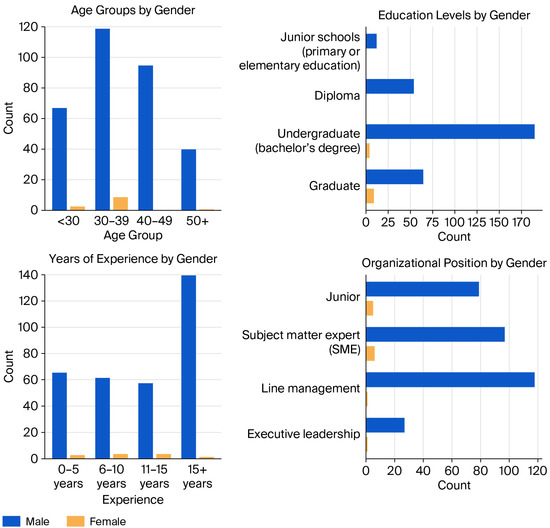

A quantitative methodology was adopted to effectively address the research objectives and questions. A structured, self-administered questionnaire was distributed electronically within Saudi Arabia’s drilling industry, where sustainability practices are gaining increasing relevance. The survey questions were carefully crafted to maintain confidentiality, clarity, and suitability to the specific context of the Saudi drilling sector. All items were adapted from the established literature to ensure construct validity. Participants held managerial, technical, and operational positions in which proficiency in business English is routinely expected or required; thus, the questionnaire, designed in English (consistent with formal business communication in Saudi Arabia), included 52 items representing four latent constructs: GSCM, CSR, IC, and SP. Responses were measured on a five-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree; 5 = Strongly Agree). Data were gathered from employees in the Eastern Region, the largest area in the Kingdom, as it hosts most of Saudi Arabia’s drilling operations and related supply chain activities. Data collection took place over five weeks via an online questionnaire designed specifically for this study using Google Forms. A total of 369 responses were collected. After rigorous data-cleaning procedures, including the removal of incomplete responses and those with indications of inattentive responding (e.g., response times under one minute or straight-lining), a final sample of 334 valid responses was retained. This sample size is appropriate for statistical analysis, meeting the recommended threshold for models of moderate complexity [145]. Although the sample is robust in size and balanced across roles, it is limited to one region and one industry. Informed consent for participation in the study was obtained (see questionnaire for more details). Refer to Figure 2 for participant demographics pertaining to gender, position, education, and years of work experience.

Figure 2.

Demographic profile.

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Measurement Model Analysis

GSCM was operationalized as a second-order construct comprising four dimensions: GP (four items, CR = 0.84, AVE = 0.57, loadings = 0.69–0.80), GM (four items, CR = 0.82, AVE = 0.54, loadings = 0.70–0.79), GL (two retained items (GL3 and GL4 were dropped), CR = 0.71, AVE = 0.55, loadings = 0.66–0.81), and RL (four items, CR = 0.81, AVE = 0.51, loadings = 0.69–0.73). CSR was modeled as a second-order construct with three dimensions: EnvR (four items, CR = 0.88, AVE = 0.64, loadings = 0.76–0.82), EcoR (four items, CR = 0.84, AVE = 0.57, loadings = 0.73–0.79), and SR (four items, CR = 0.85, AVE = 0.58, loadings = 0.73–0.79). IC was conceptualized as a higher-order construct encompassing GHC (four items, CR = 0.87, AVE = 0.63, loadings = 0.77–0.81), GSC (four items, CR = 0.89, AVE = 0.66, loadings = 0.76–0.85), and GRC (four items, CR = 0.86, AVE = 0.61, loadings = 0.76–0.82). SP was assessed using a multidimensional scale: EnvP (four items, CR = 0.85, AVE = 0.59, loadings = 0.74–0.80), SocP (four items, CR = 0.85, AVE = 0.60, loadings = 0.67–0.89), and EcoP (five items, CR = 0.84, AVE = 0.57, loadings = 0.69–0.79).

All higher-order constructs in this study—GSCM, CSR, and IC—were modeled as reflective–reflective constructs. In this configuration, the first-order dimensions (e.g., green procurement, green manufacturing, environmental responsibility, green human capital) are treated as reflective indicators of their respective higher-order construct, and the observed questionnaire items serve as reflective indicators of the first-order dimensions. This reflective–reflective modeling assumes that the first-order constructs and items are manifestations of the underlying higher-order latent variable, rather than forming it. Accordingly, the assessment of the measurement model focused on internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability), convergent validity (average variance extracted, AVE), and discriminant validity (Fornell–Larcker criterion and HTMT ratios). Each first-order construct was validated individually before specifying the corresponding second-order construct in the structural model, ensuring that the higher-order constructs were reliably and validly represented. All constructs exhibited strong internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha values exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.70. During the measurement model assessment, items GL3 and GL4 exhibited low factor loadings (0.40) on the green logistics dimension, falling below the commonly recommended threshold of 0.50 for reflective indicators [146]. Consequently, these items were removed from the analysis to improve the reliability and convergent validity of the construct. The remaining items retained strong loadings and demonstrated adequate composite reliability (CR = 0.71) and average variance extracted (AVE = 0.55), confirming that the green logistics dimension continued to validly and reliably represent its theoretical construct. Refer to Table 1 and Table 2 for goodness-of-fit measures and model measures.

Table 1.

Measures and Confirmatory Factor Analysis.

Table 2.

Goodness-of-Fit Index of the model.

This five-point Likert scale was used to assess each construct, and reliability, factor loadings, and goodness-of-fit analyses were conducted on each scale (see Appendix A for further details). The empirical data were also analyzed quantitatively to explore the relationships between variables. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was also utilized to test the mediating hypothesis, providing a more comprehensive approach than separate regression analyses [146].

4.2. Model Fit Justification

Model fit was assessed using multiple goodness-of-fit indices, following the recommendations in [147,148], to evaluate the adequacy of the structural model. The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) was 0.056, indicating a good fit, as it is below the recommended threshold of 0.08 [148]. The Comparative Fit Index (CFI = 0.900) and the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI = 0.890) both approached the conventional cutoff of 0.90, suggesting an acceptable model fit, though the TLI marginally fell short of the ideal benchmark. The chi-square-to-degrees-of-freedom ratio (CMIN/DF = 2.03) further supported the model’s adequacy, as it fell within the acceptable range of 1 to 3 [149]. Additionally, the Root Mean Square Residual (RMR = 0.053) was well within acceptable limits, indicating minimal discrepancies between observed and predicted covariances. However, the Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI = 0.762) remained below the commonly cited 0.90 threshold, suggesting a less-than-optimal global model fit. This suboptimal GFI may be attributable to the model’s complexity and the number of parameters estimated, consistent with prior findings that the GFI is particularly sensitive to sample size and model complexity [150]. Despite the low GFI, the overall configuration of the fit indices—including acceptable RMSEA, RMR, CFI, and TLI values—supports the adequacy of the model. Taken together with strong evidence of construct validity, reliability, and theoretical alignment, the fit indices provide sufficient justification for proceeding with hypothesis testing. Although the Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI = 0.762) is below the conventional threshold of 0.90, other widely accepted fit indices—including the Comparative Fit Index (CFI = 0.90), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI = 0.89), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA = 0.056)—indicate acceptable model fit, consistent with recommendations for complex structural equation models [147]. The relatively low GFI is likely a consequence of the model’s complexity, which incorporates multiple higher-order constructs and two parallel mediators, resulting in a larger number of estimated parameters. Importantly, the inclusion of multiple second-order constructs and two parallel mediators substantially increase the number of estimated paths and covariances in the model. Such complexity is known to disproportionately affect absolute fit indices such as the GFI, which tend to penalize models with many parameters [151]. Consequently, the comparatively low GFI observed here is consistent with expectations for higher-order and mediator-intensive models, rather than indicative of poor theoretical or empirical specification. In addition, it is worth mentioning that our proposed model incorporates 4 second-order constructs and 13 first-order constructs. According to [148], in models of substantial complexity, indices such as the CFI, TLI, and RMSEA are more reliable indicators of model adequacy than the GFI alone. Combined with strong factor loadings, high composite reliability, and convergent and discriminant validity, these results provide confidence that the measurement and structural models are adequately specified and represent the data well.

4.3. Common Method Bias

Given the use of a self-administered questionnaire and the single-source nature of the collected data, it was imperative to examine the possibility of common method bias (CMB), which can threaten the internal validity of the findings. To address this concern, multiple diagnostic techniques and procedural safeguards were employed. First, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted using principal axis factoring on all 49 measurement items without rotation. The results indicated that the first factor accounted for 44.59% of the total variance, below the commonly accepted threshold of 50%, suggesting that common method variance is unlikely to be a substantial problem [152]. While this test is widely used, it is recognized as a relatively weak diagnostic and cannot fully rule out CMB. To strengthen the assessment, additional statistical checks were performed. Variance inflation factors (VIFs) were computed for all constructs by regressing the dependent variable on the independent and mediator constructs. The VIF values ranged from 2.80 to 3.57, all below the commonly recommended threshold of 5 [153], indicating that multicollinearity among the constructs was not problematic. These results further suggest that CMB is unlikely to seriously distort the observed relationships. Procedural safeguards were also implemented during questionnaire design to minimize potential bias. These included ensuring respondent anonymity, clarifying that there were no right or wrong answers, randomizing item order where possible, and using constructs derived from previously validated scales. Theoretical distinctiveness among constructs and the absence of unusually high inter-construct correlations further mitigated the risk of method bias. Although a more robust approach, such as the unmeasured latent method construct (ULMC) within CFA, is recommended for future research to provide even greater confidence, the current combination of Harman’s test, VIF analysis, and procedural remedies provides reasonable assurance that common method bias is not a serious threat in this study. In future research, further procedural remedies such as source triangulation or temporal separation of measures may be employed to minimize potential bias. Nonetheless, based on the current assessment, common method bias does not appear to significantly distort the findings.

4.4. Hypothesis Testing Results

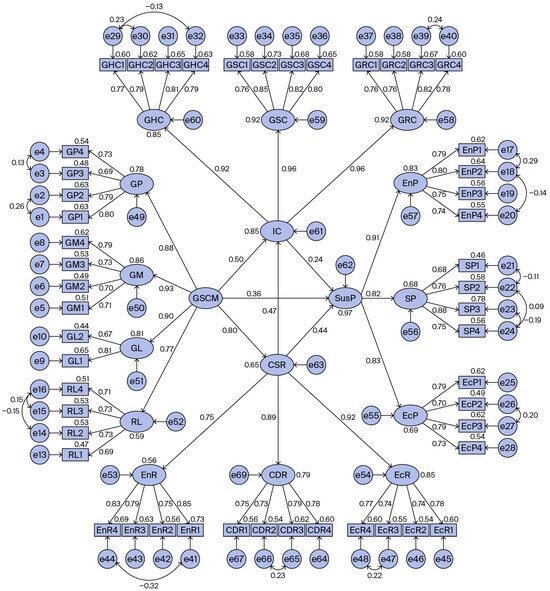

To ensure the validity and reliability of the measurement model, a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was performed using IBM AMOS (v.29), following the two-step modeling approach advocated by [154]. The CFA results confirmed that all latent constructs demonstrated acceptable psychometric properties in line with recommended thresholds [148]. Specifically, standardized factor loadings across all items were found to exceed the minimum acceptable level of 0.60, indicating adequate convergent validity. Composite reliability (CR) scores for each construct ranged from 0.71 to 0.94, all surpassing the commonly accepted threshold of 0.70. Furthermore, the average variance extracted (AVE) values were within the acceptable range of 0.50 to 0.66, suggesting that the constructs captured sufficient variance from their respective indicators. Internal consistency was affirmed through Cronbach’s alpha values, all of which exceeded 0.80, with some constructs, such as IC and GSCM, reporting values above 0.90, underscoring strong reliability. Additionally, discriminant validity was confirmed, as the square roots of the AVE values for each construct were higher than their respective inter-construct correlations. These results collectively indicate that the measurement model exhibits strong construct reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity, thereby justifying the use of latent constructs in the subsequent structural model analysis. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to test the hypothesized relationships using a bootstrapping approach with 5000 resamples at a 95% confidence level. The findings are presented below, with each hypothesis evaluated based on path coefficients, p-values, and theoretical implications. Refer to Figure 3 for the structural model with beta values and Table 3 for the betas of path analysis.

Figure 3.

Structural paths.

Table 3.

Path estimates.

Hypothesis 1 proposed that GSCM has a positive impact on SP. This hypothesis was supported by the analysis, with a statistically significant path coefficient (β = 0.357, p = 0.018). This result suggests that organizations implementing green procurement, manufacturing, logistics, and reverse logistics practices tend to enhance their environmental, social, and economic performance [11,70]. Hypothesis 2 posited that GSCM positively influences IC. The results confirm this relationship (β = 0.500, p = 0.010), indicating that environmentally oriented supply chain practices contribute to the development of green human capital, structural capital, and relational capital. This result is in line with previous studies, for example, ref. [83]. Hypothesis 3 asserted a positive relationship between GSCM and CSR. This hypothesis was strongly supported, with a high path coefficient (β = 0.805, p = 0.010), highlighting that organizations with advanced green supply chain practices are more likely to exhibit environmentally and socially responsible behavior [114]. A possible reason for this strong pathway is the emphasis on sustainability by the Saudi Vision framework, perceiving GSCM practices as a core CSR commitment. Hypothesis 4 stated that IC has a positive impact on SP. This was not supported by the data (β = 0.243, p = 0.283), as the p-value exceeds the conventional 0.05 threshold, diverging from findings in other industries where IC has been shown to enhance SP outcomes [20,121]. Although the RBV suggests that IC should improve SP, these studies emphasized that the components of IC—human, structural, and relational capital—should develop together, not in isolation. For example, a recent study [124] found that structural capital had no effect on SP. In general, organizations such as those in the drilling sector usually face challenges in measuring such intangible assets. Hypothesis 5 proposed that CSR positively affects SP. This hypothesis was supported (β = 0.440, p = 0.010), suggesting that CSR plays a significant direct role in enhancing organizational sustainability, which is in line with previous empirical studies, such as [26]. Hypothesis 6 proposed that IC mediates the relationship between GSCM and SP. The mediation effect was statistically insignificant (indirect β = 0.120, p = 0.283), failing to support this hypothesis and emphasizing that the performance benefits of GSCM are not necessarily transmitted through intellectual assets. This finding contrasts with the previous literature that supported this relationship [20,83]. Although this study theoretically hypothesizes that a desired outcome can be more beneficial when GSCM’s practices foster the underlying IC, the development of such intangible knowledge in the Saudi drilling sector might need more time. Hypothesis 7 posited the mediating role of CSR in the GSCM–SP relationship. The results indicate a significant indirect effect (β = 0.352, p = 0.010), confirming CSR as a meaningful conduit through which green supply chain practices influence sustainability outcomes. This pathway underscores the Stakeholder Theory perspective that legitimacy and trust are central to performance [25,137]. Hypothesis 8 proposed a positive relationship between CSR and IC. This hypothesis was also supported (β = 0.470, p = 0.010), indicating that CSR initiatives contribute to the enhancement of intellectual resources within firms by attracting talent and building knowledge-based capabilities [129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143].

The current study provides noteworthy findings. While both IC and CSR were tested as potential mediators in the relationship between GSCM and SP, only CSR was significant, highlighting the predominant pathway through which green supply initiatives generate sustainability benefits. Notably, the findings demonstrate that the complementary roles of intangible resources (IC) are less critical than socially responsible practices (CSR) in converting environmental strategies into tangible sustainability outcomes. Furthermore, the demonstrated influence of CSR on IC underscores the interdependence of social and knowledge-based assets in modern sustainable management. These insights have valuable theoretical and managerial implications, particularly for firms in the industrial sector of Saudi Arabia, suggesting that an integrated approach leveraging these focal variables can drive superior performance in sustainability.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to explain the relationships between GSCM practices, IC, CSR, and overall SP within the specific context of Saudi Arabia’s drilling industry, an area undergoing significant transformation under Vision 2030. The findings provide valuable insights into how environmental strategies translate into performance outcomes, highlighting the differential roles of intangible knowledge assets and corporate social positioning.

The results demonstrate that adopting GSCM has a significant positive direct effect on SP, supporting Hypothesis 1. This aligns with previous studies suggesting that GSCM practices (GP, GM, GL, RL) function as valuable organizational capabilities [104,105]. By integrating environmental considerations into operations, firms can achieve resource efficiencies, reduce waste and emissions (contributing to EnvP and EcoP), enhance corporate image, and potentially improve stakeholder relations (SocP), ultimately leading to better overall SP [11,49,61,70]. This is particularly pertinent in the Saudi context, where regulatory pressures and national sustainability goals under Vision 2030 amplify the strategic importance of GSCM [43].

Furthermore, this study confirms that GSCM implementation significantly enhances both organizational IC (Hypothesis 2 supported) and CSR (Hypothesis 3 supported). The GSCM–CSR relationship (β = 0.805) underscores that GSCM practices serve as tangible mechanisms for operationalizing environmental and related social commitments [40,114], signaling responsible conduct to stakeholders [25]. Concurrently, adopting GSCM necessitates organizational learning, fostering the development of green-specific knowledge, skills (GHC), systems (GSC), and external relationships (GRC), thereby building IC [11,20]. These findings highlight GSCM’s dual role in driving both demonstrable responsibility and internal capability development.

Regarding the impact of the mediating variables on SP, the results diverge. CSR was found to have a significant positive impact on SP (Hypothesis 5 supported), consistent with the extensive literature and meta-analyses suggesting that responsible corporate behavior builds stakeholder trust, enhances reputation, mitigates risk, and can foster innovation, contributing to holistic performance [26,126,127]. This appears particularly relevant in Saudi Arabia, where fulfilling social and environmental expectations aligns with national priorities and likely strengthens the social license to operate. Surprisingly, no statistically significant direct relationship was found between IC and SP (Hypothesis 4 not supported). This contrasts with theoretical expectations based on the RBV and empirical findings in other contexts where IC is often linked to performance and innovation [20,83]. Several factors might explain this in the Saudi drilling sector: the specific green dimensions of IC measured might still be developing or be less critical for immediate SP compared to operational efficiencies or compliance; the time lag for IC investments to translate into measurable SP might be longer; or the strong influence of CSR and direct GSCM impacts may overshadow the independent contribution of IC in this specific, high-pressure industrial environment. Additionally, while the results disprove the hypothesis that IC affects the SP of the Saudi drilling sector, certain facets of the IC construct, such as GRC, may increase its effect if explored further in a similar context. Examples of these constructs include shared resources and knowledge with other organizations to increase collaboration and public perception to enhance stakeholders’ involvement.