Abstract

Stable operating conditions in electrolyzers are crucial for preserving system durability, ensuring highly pure hydrogen production, and enabling the sustainable utilization of surplus renewable electricity. However, in active distribution networks, the output uncertainty of distributed energy resources, such as renewable energy sources (RES) on the generation side and load demand side, can lead to voltage fluctuations that threaten the operational stability of electrolyzers and limit their contribution to a low-carbon energy transition. This paper proposes a novel framework for optimal electrolyzer placement, tailored to their operational requirements and to the planning of sustainable renewable-integrated distribution systems. First, probabilistic scenario generation is carried out for RES and load to capture the characteristics of their inherent uncertainties. Second, based on these scenarios, continuous power-flow-based P–V (power–voltage) curve analysis is conducted to evaluate voltage stability and identify the loadability and load margin for each bus. Finally, the optimal siting of electrolyzers is determined by analyzing the load margins obtained from the voltage stability assessment and deriving a probabilistic electrolyzer hosting capacity. A case study under various uncertainty scenarios examines how applying this method influences the ability to maintain acceptable voltage levels at each bus in the grid. The results indicate that the method can significantly improve the likelihood of stable electrolyzer operation, support the reliable integration of green hydrogen production into distribution networks, and contribute to the sustainable planning of other voltage-sensitive equipment.

1. Introduction

Global decarbonization efforts are accelerating in response to the ongoing climate crisis, with a strong emphasis on developing technologies that support the integration of renewable energy sources into power systems. Although renewable energy has significantly reduced carbon dioxide emissions, its inherent variability challenges consistent and reliable power generation. Hydrogen has recently emerged as a promising solution to address the uncertainty associated with renewable energy [1]. Green hydrogen, produced through water electrolysis, stabilizes power systems by converting surplus electricity into storable hydrogen. This stored hydrogen can later be used to generate electricity when renewable generation falls short of demand. As part of a global initiative to establish a comprehensive hydrogen value chain—including production, storage, and distribution—there is increasing demand for water electrolyzers capable of efficiently converting electricity into hydrogen. While electrolyzers currently contribute only about 0.1% to global hydrogen production, the rapid expansion of installed capacity—from 700 MW in 2022 to 2 GW within a year—indicates that green hydrogen is poised to play a transformative role in hydrogen production over the coming decades [2]. Moreover, from a system operation perspective, electrolyzers can be operated as long-duration, controllable loads that continuously absorb renewable variability and contribute to frequency regulation. At the same time, they convert surplus electricity into value-added hydrogen, which can be stored and utilized in other sectors, thereby enhancing overall economic viability. This distinguishes electrolyzers from conventional battery energy storage systems, which can provide similar short-term flexibility services but are inherently limited by their discharge duration and can only charge and discharge electrical energy without creating an additional energy carrier.

Two primary types of water electrolysis technologies exist: alkaline electrolysis (AEL) and proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolysis. AEL currently accounts for over 60% of installed electrolyzers, primarily due to its low capital cost and high durability. However, compared with PEM technology, AEL systems typically exhibit lower current density, a larger installation footprint, and a more restricted dynamic operating range, which makes their integration with variable renewable power more challenging [3].

In contrast, PEM electrolyzers can rapidly respond to load fluctuations due to their cationic polymer electrolyte. However, they are more expensive to produce, requiring rare metals for their electrodes [4]. Emerging technologies such as anion exchange membrane (AEM) electrolysis offer both fast dynamic response and cost-effectiveness but remain in the early stages of development [5]. While recent studies have focused on enhancing the robustness of electrolyzers under variable generation and load conditions [6], advancements in materials engineering often require extended timeframes to reach commercial viability. Given its relatively high level of technological maturity, the early-stage hydrogen industry is expected to rely heavily on AEL technology. Therefore, it is essential to develop technologies that enhance the operational efficiency and flexibility of AEL systems to facilitate the broader adoption of water electrolyzers and support the global roadmap for hydrogen expansion.

To ensure the stable operation of AEL systems, their specific operational requirements must be carefully considered. First, electrolyzer must be maintained within a specific voltage range to protect the electrical balance of plant (E-BOP). Second, a minimum operational load threshold must be upheld to preserve gas purity and the chemical stability of the electrolysis process. If the grid-side conditions fail to satisfy these constraints, the power converter is forced to shut down until acceptable operating conditions are restored, and frequent transitions across these limits may accelerate component aging [7,8].

Load fluctuations and the inherent unpredictability of renewable energy generation can lead to voltage instability within the distribution system. However, the extent of this impact varies depending on the specific bus location within the same grid. As a result, the probability of an AEL maintaining stable operation under such uncertain conditions may differ based on its point of connection. In this context, the present study proposes a methodology to evaluate the feasibility of various locations in sustaining the operational conditions required for AEL performance.

In the meantime, Relatively little research has been devoted to evaluating electrolyzer locations based on operational stability and efficiency, which represents a critical gap that deserves further investigation. Kim et al. [9] optimized electrolyzer placement based on voltage stability; however, they did not account for uncertainties arising from renewable generation and load variability. Therefore, it is essential to incorporate distribution system uncertainties into the evaluation process to assess suitable locations for electrolyzer deployment accurately. Numerous power system studies have incorporated uncertainty modeling for various purposes. Previous research has typically focused on uncertainty in determining the optimal location or size of distributed generation (DG). For example, the authors of [10] used a normal distribution to model probabilistic power demand. Similarly, refs. [11,12] proposed an optimization method for DG placement to reduce power losses in the distribution system, using a Weibull distribution for wind speed and a normal distribution for load demand.

Combining probabilistic models with voltage stability analysis has been used to assess whether the electrolyzer can reliably meet its operational requirements under uncertain conditions. Accordingly, several studies have applied probabilistic models to voltage stability assessment to account for distribution systems’ inherent unpredictability. For example, prior studies introduced probabilistic methods for evaluating voltage stability that emphasize the impacts of load variations and generator outages [13,14]. More recently, a non-parametric approach using vine copula and Gaussian process emulation was proposed to assess probabilistic load margins under renewable generation uncertainties while accounting for correlations among wind speeds, solar generation, and load demand [15].

Moreover, Xu et al. [16] introduced a global sensitivity analysis method to prioritize uncertainties in renewable energy sources by evaluating correlation and importance indices, thereby identifying critical variables that influence a grid’s load margin. In another study, Rawat et al. [17] applied a contingency ranking approach in combination with detailed load models to calculate probabilistic voltage stability margins. Similarly, the authors of [18] proposed a novel approach using a probabilistic transferable deep kernel emulator integrated with a deep neural network to examine how various uncertainty sources (e.g., wind generation and load demand) correlate with the load margin.

In addition, several studies have focused on improving sampling methods for probabilistic analysis to enhance computational efficiency. For example, Zhang et al. [19] combined Latin hypercube sampling with a twice-permutation technique to improve probabilistic estimation while considering the direction of power increment. Similarly, Liu et al. [20] proposed a two-point estimation method integrated with continuation power flow (CPF) to determine the probability density function (PDF) of critical voltage stability and compared its computational efficiency with that of Monte Carlo simulation. However, ref. [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20] have not been devoted to the optimal placement of electrolyzers, indicating that, to the best of our knowledge, there has so far been almost no literature evaluating the power-system impacts of electrolyzer integration under uncertainty.

Based on the above literature review, Table 1 comparatively summarizes representative studies in terms of whether they address electrolyzer placement, power-system impacts, input uncertainties, and CPF-based P–V analysis.

Table 1.

Comparison of Proposed Method with Related Works.

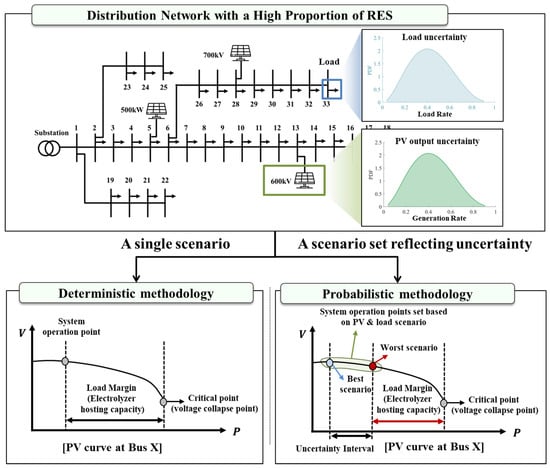

As summarized above, most existing studies on electrolyzer placement do not explicitly incorporate voltage stability assessment. In addition, the voltage stability studies traditionally addressed in the power systems literature are largely confined to transmission networks, which makes their direct application to the distribution system where electrolyzers are connected. However, since electrolyzers are strongly voltage-sensitive loads, a dedicated evaluation of the voltage stability margin at the prospective electrolyzer interconnection buses is essential. Even though the authors of [9] have introduced a voltage stability based electrolyzer placement strategy, the lack of uncertainty modeling limits its ability to evaluate the load margin at each bus. Figure 1 illustrates how uncertainties in PV output and load demand are incorporated into a voltage stability–based placement framework. In the deterministic approach of [9], the analysis is performed for a single scenario, which yields a single load margin (i.e., electrolyzer hosting capacity) at each bus. By contrast, in the probabilistic framework, a set of operating scenarios is generated, the corresponding system operating points are evaluated, and bus-level load margins are computed for each scenario. This enables the derivation of a probabilistic electrolyzer hosting capacity that reflects the range of system conditions under PV and load uncertainty, rather than a single deterministic value. As a result, a deterministic assessment may overlook the risk induced by PV and load uncertainties under grid-connected operating conditions and fail to identify buses where the electrolyzer faces a high probability of insufficient voltage stability margin.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the renewable-integrated distribution network and probabilistic voltage stability–based placement framework. The numbers at each node represent the bus indices of the distribution feeder.

To this end, a novel framework is proposed for the optimal placement of electrolyzers based on probabilistic voltage stability analysis in distribution networks. In this paper, PV output and load are modeled as random variables with prescribed PDFs to capture their inherent uncertainties. Monte Carlo sampling from these distributions yields a set of operating scenarios (i.e., PV and load samples), which are then used in the electrolyzer placement analysis. Subsequently, the loadability and load margin for each bus and scenario are evaluated through voltage stability analysis, taking into account the allowable voltage operating range of electrolyzers. Finally, the optimal location is determined as the bus with the largest load margin. This study contributes to improving the efficiency of green hydrogen production and mitigating electrolyzer degradation. The research employs MATPOWER [23] to perform CPF calculations, enabling the determination of load margins and power-voltage characteristics for each scenario. The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this study is the first to propose an optimal electrolyzer placement strategy that explicitly considers voltage stability under both demand- and supply-side uncertainties in active distribution networks. Since electrolyzers are highly sensitive to voltage fluctuations, conducting a voltage stability assessment that accounts for power system uncertainties is essential before integration. This approach is expected to enhance the quality of hydrogen production for existing electrolyzers.

- From the perspective of voltage stability analysis, unlike conventional load allocation methods that focus solely on identifying the maximum load margin, this study introduces a voltage-sensitive loadability assessment tailored to the operating range of voltage-sensitive equipment, such as electrolyzers. The proposed methodology also applies to other types of voltage-sensitive loads beyond electrolyzers.

- While conventional voltage stability assessment methods typically focus on system-wide violations, this study determines bus-specific loadability, enabling a more localized and effective approach for optimal placement of voltage-sensitive facilities in distribution networks.

This paper is organized as follows to determine the optimal location for electrolyzers: Section 2 presents probabilistic models that capture the uncertainties associated with load demand and renewable generation. Section 3 describes the proposed evaluation methodology, focusing on load margin calculation. Section 4 presents a case study that investigates the impact of grid conditions on voltage stability and the potential for electrolyzer operational failure. Finally, Section 5 provides a summary and highlights the key findings of the study.

2. Probabilistic Uncertainty Modeling in Distribution System

In this paper, the term probabilistic refers to an analysis framework where the uncertainties in PV output and load demand are modeled as random variables with PDFs. Instead of evaluating voltage stability at a single, fixed operating point, we generate a large number of scenarios by Monte Carlo sampling from these PDFs and, for each scenario, compute the corresponding loadability and load margin. As a result, loadability and failure risk are treated not as single deterministic values, but as random variables characterized by their probability distributions. Probabilistic modeling has been increasingly integrated into power system analysis due to the growing uncertainty associated with renewable generation and load variability. Unlike deterministic models, which assume fixed operating conditions, probabilistic models account for the inherent unpredictability of power system components, enabling evaluations across a wide range of conditions and scenarios.

Numerous prior studies have applied probabilistic models to power system analysis to address uncertainties in components such as load and generation. For example, Ref. [24] demonstrates the application of probabilistic models to uncertain system elements, including renewable generation, demand, faults, and electricity prices. Uncertain load profiles are commonly modeled using Gaussian or Gumbel probability distributions, while solar generation is often represented with Beta or Weibull distributions due to their skewed averages and narrow tails. The probabilistic approach provides a more robust assessment of voltage stability and other critical aspects of power system performance under uncertain conditions.

Applying probabilistic models to voltage stability assessment facilitates evaluating a power system’s ability to maintain acceptable voltage levels during disturbances and load fluctuations. This study adopts a probabilistic approach to voltage margin assessment by varying load levels, as proposed in [25]. Unlike traditional assessments focused on instability thresholds or voltage sensitivity, this research emphasizes the ratio of voltage violations within the E-BOP of electrolyzers. This perspective offers valuable insights into the robustness of voltage stability under probabilistic scenarios, thereby enhancing the reliability and operational efficiency of electrolyzer systems.

2.1. Supply Side Uncertainty Modeling

In this study, the uncertain generation profile is modeled as follows:

where represents the Beta distribution determined by its parameters, and . The PDF of is defined as follows:

where represents the Beta function, defined as follows

Note that is the Gamma function, defined as

The Beta distribution is a continuous probability distribution that confines the random variable within the range. The skewed bell-shaped distribution varies depending on the Beta function parameters, and .

2.2. Demand Side Uncertainty Modeling

Meanwhile, the load fluctuation is modeled as a random variable following a normal distribution as follows:

where represents the normal distribution and and are the parameters to determine the mean and the standard deviation of the distribution, respectively. The PDF of the normal distribution is defined as follows:

resulting in a symmetric bell-shaped curve of a normal distribution depending on and .

3. Optimal Electrolyzer Placement Strategy

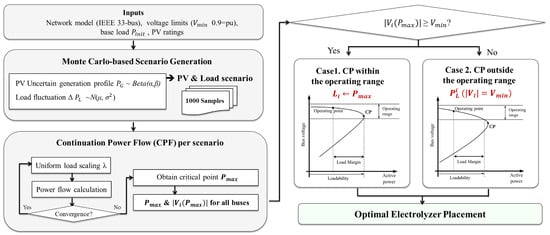

In this section, the probabilistic voltage stability assessment is carried out based on the generated scenarios in Section 2. Prior to presenting the proposed optimal placement strategy for the electrolyzer, this paper outlines the necessary preliminaries, including voltage stability assessment based on P–V analysis and the voltage operating range considerations of the electrolyzer. Figure 2 depicts the proposed framework for the proposed optimal electrolyzer placement strategy.

Figure 2.

Framework for the proposed optimal electrolyzer placement strategy.

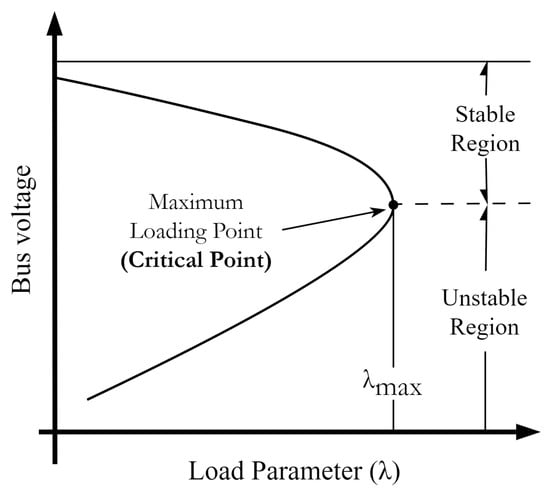

- Preliminary 1. Static Voltage Stability Evaluation

In power system studies, static voltage stability is of paramount importance [26], particularly during the planning stage. A conventional approach to assess voltage stability is to construct the power-voltage (P–V) curve of the system.

As illustrated in Figure 3, a typical P–V curve delineactes stable and unstable operating regions. From this curve, operators can determine the maximum power demand the grid can accommodate without triggering a system voltage collapse; this maximum occurs at the so-called “nose” point of the P–V curve. This operating condition corresponds to the system’s maximum loading point, also known as the critical point (CP).

Figure 3.

The typical P–V curve.

The CPF method is commonly employed to generate the P–V curve [27]. CPF incrementally scales the system load using a scalar parameter , and solves the power flow equations at each step. The CP is reached when no further feasible solution exists as increases, i.e.,

This maximum value corresponds to the total system load (i.e., system loadability) and defines the voltage stability boundary.

To derive the P–V curve and identify the CP, a widely used approach is the CPF method [27]. The CPF algorithm incrementally increases the total system load and computes the corresponding power flow solutions at each step using a prediction and correction scheme. This process traces the entire P–V curve to its nose point, thereby pinpointing the CP.

In principle, CPF augments the standard power flow equations by introducing an additional parameter that scales the total load level. This load parameter acts as a scalar multiplier on the base system load. The power flow equation at bus k can thus be expressed as follows:

where and represent the voltage magnitude and phase angle at bus k, respectively; and are the active and reactive power injection at bus k, respectively; and and are the conductance and susceptance of the branch connecting buses k and m, respectively.

The load parameter represents the incremental factor of the total system load and is integrated into the power flow equations as follows:

where and are the sum of active and reactive generation in the system, respectively. and are the sum of the active and reactive power demand, respectively. The CP on the P–V curve corresponds to the total active power demand when reaches its maximum value.

- Preliminary 2. Voltage Range Considerations

Electrolyzers require strict voltage and frequency conditions for stable operation. Specifically, the grid frequency must remain between 47 and 63 Hz, and the voltage must be maintained within 90–110% of the nominal level [28]. Power quality issues such as flicker, imbalance, and harmonic distortion must also be avoided.

In distribution systems, voltage deviations due to load or generation fluctuations can compromise electrolyzer stability. While the traditional load margin estimates the maximum load before voltage collapse, it does not guarantee compliance with device-specific voltage constraints. If the voltage at the collapse point falls below the electrolyzer’s minimum requirement, operational violations may occur before the collapse itself. To address this, the proposed method introduces a voltage-sensitive loadability that reflects the permissible voltage range. Unlike prior studies that consider system-wide violations [29], this work evaluates load margin and limit on a per-bus basis, enabling localized assessment of voltage stability. The approach can be extended to other voltage-sensitive loadability requiring strict voltage security.

3.1. Voltage-Sensitive Loadability

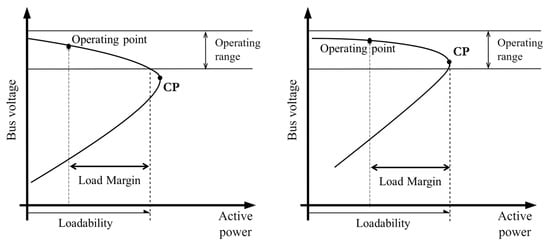

Unlike conventional methods, the proposed voltage-sensitive loadability assessment determines unique loadability for each bus. This study introduces a novel loadability concept, which is a concept accounting for a facility’s operating voltage range, referred to as the loading limit. The definition of the loadability depends on whether the operating condition of the power system at the CP falls within or outside the acceptable voltage range. The method for determining the loadability according to the voltage level of the CP is described as follows.

3.1.1. Case 1: CP Within the Acceptable Voltage Range

If the CP lies within this range, the loadability is assessed like the conventional voltage stability margin. At the voltage collapse point of the corresponding bus, stable hydrogen production by the electrolyzer is no longer feasible. Accordingly, the operating point of the electrolyzer (i.e., the loading level) cannot be increased any further, even if the voltage at the CP does not fall below the lower bound of the acceptable voltage range. Therefore, the increase in the operating point up to the CP is defined as the load margin at the corresponding bus.

3.1.2. Case 2: CP Outside the Acceptable Voltage Range

Conversely, if the CP lies outside the acceptable voltage range, any further increase in the operating point of the electrolyzer must be restricted to prevent violation of the voltage constraints. Even if the voltage collapse point is not reached as the operating point increases, the electrolyzer must be disconnected from the system if the voltage falls outside its allowable operating range to ensure equipment protection. Accordingly, the increase in the operating point up to the lower voltage limit is defined as the load margin at the corresponding bus. That is, loadability refers to the absolute maximum net load for each bus at which all operational constraints remain satisfied while monitoring a particular bus (i.e., the highest operable loading level consistent with that bus’s allowable voltage range). In contrast, the load margin denotes the additional load that can be accommodated from the initial operating point up to the loadability. Hence, loadability is an absolute threshold, whereas load margin is the corresponding increment from the initial load to that threshold. Figure 4 illustrates the loadability concepts for both scenarios.

Figure 4.

The loadability concept considering the operation conditions of the electrolyzer when the CP is below (left) or above (right) the lower boundary of the voltage range.

The CPF method computes successive points along the P–V curve, yielding the voltage magnitude and phase angle for each incremental loading condition. However, the CPF process does not explicitly identify the operating point at which bus voltages reach the boundaries of the permissible voltage range. As voltage magnitudes vary across buses for a given load level, the onset of voltage limit violations is bus-dependent, leading to distinct operable loadability for each bus. To determine the loadability for each bus, intermediate operating points on the P–V curve—skipped by the CPF process—are estimated using spline interpolation. This approach enables calculating the maximum acceptable system loading while ensuring that the voltage magnitude at a specific target bus remains within the allowable range. The system load margin of the entire grid is defined as the difference between the maximum net load the system can accommodate and the initial load condition.

For each bus i, we first define the voltage-sensitive loadability , and then the corresponding load margin (i.e., the increment from the initial load) as follows.

Here, denotes the system loadability obtained at the CPF nose point, i.e., the maximum net system load; is the initial net system load at the base operating point. The quantity is the bus-i loadability limit when the voltage constraint at bus i is enforced, and is the additional load that can be accommodated from up to . The symbol represents the voltage magnitude (per-unit) at bus i under a given total system load, while is the lower bound of the admissible voltage range for the facility (e.g., pu in this study). Finally, indicates the total net system load at which along the CPF trajectory. In this study, the lower voltage bound is set to 0.9 pu, which corresponds to the electrolyzer’s minimum operating point. Accordingly, if the CP lies at or below 0.9 pu (i.e., with pu), denotes the total net system load at the lower-bound operating point, that is, at pu.

3.2. Probabilistic Voltage Stability Assessment

To address uncertainty in renewable generation and load, this study adopts a scenario-based probabilistic approach using Monte Carlo simulation. Key uncertainties include photovoltaic (PV) generation and system load, both modeled with appropriate probability distributions. PV output is represented by a Beta distribution, which confines the generation rate to the physical range [0, 1], ensuring realistic output levels relative to rated capacity. Load variation is modeled using a normal distribution, consistent with the central limit theorem, which reflects the aggregate behavior of diverse loads. Each simulation scenario yields a load margin and limit per bus. The bus with the highest probabilistic loadability is identified as the optimal electrolyzer location.

A scenario-based probabilistic assessment is recommended to effectively account for uncertainty and support the development of robust solutions for power system planning and operation. As described in Section 2, a probabilistic model is constructed by identifying the key factors of uncertainty and selecting appropriate PDFs to characterize them. This study determines the outputs of DGs and system load demand as probabilistic inputs. Then, a Monte Carlo simulation is employed to evaluate the resulting distribution of the loadability under varying operating conditions.

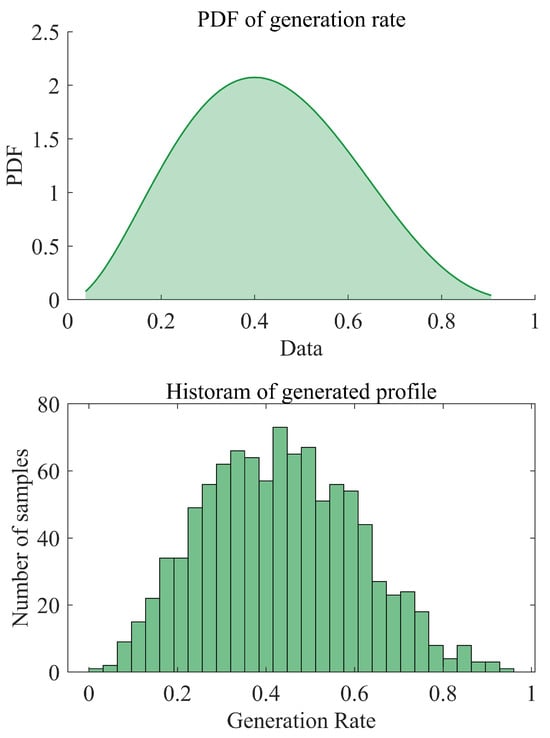

Uncertain PV generation is modeled using a Beta distribution to generate a random generation rate confined within the interval [0, 1]. This generation rate represents the actual output of a PV generator as a fraction of its rated capacity. The Beta distribution is particularly well-suited for this application because it inherently restricts the random variable within physical bounds—ensuring that the output does not fall below zero or exceed the generator’s full capacity. Figure 5 presents the PDF of the generation rate alongside the histogram of the sampled generated rates used in the assessment.

Figure 5.

The PDF of the generation rate of the renewable generation (top) and the histogram of the sampled generation rate (bottom).

In modeling load uncertainty, the central limit theorem suggests that the total load demand will approximate a normal distribution, assuming that individual load components vary independently with distinct characteristics. The normal distribution is advantageous as it yields realistic extreme values that can occasionally occur in actual power systems. Consequently, this study adopts a normal distribution to represent load variations from the test system’s base load value, thereby enhancing the robustness of the evaluation. The load margin and limit for each bus and scenario are evaluated, and the bus with the largest load margin and loadability is selected as the optimal location for the electrolyzer.

4. Simulation Results

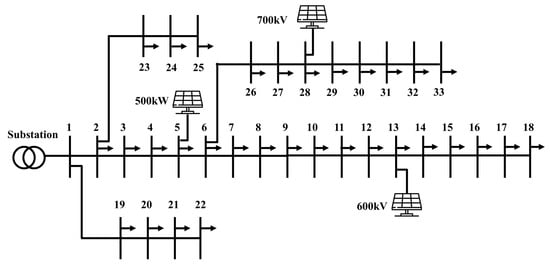

The proposed method was simulated and verified using the IEEE 33-bus test feeder [30], which has been modified to include distributed generators. In this study, it is assumed that DGs are already installed at predefined buses. Accordingly, three additional DG units are arbitrarily placed at buses 5, 12, and 28, with rated capacities of 500 kW, 600 kW, and 700 kW, respectively. The power output of each unit is modeled probabilistically by applying a random generation rate to its rated capacity. The single-line diagram of the modified test system is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The modified IEEE 33-bus test system. The numbers at each node denote the bus indices.

4.1. Voltage-Sensitive Loadability Assessment

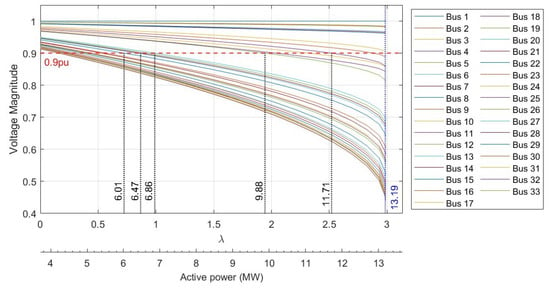

To establish the framework for calculating the proposed loadability, a deterministic evaluation was performed using the base case of the IEEE 33-bus test bus feeder without any probabilistic scenarios for generation or load demand. The deterministic evaluation results are shown in Figure 7, displaying the P–V curves for each bus. The vertical dashed lines and annotations indicate the loadability values in MW for some buses, which do not coincide with the CP.

Figure 7.

The results of deterministic loadability assessment of each bus in the modified IEEE 33-bus test feeder.

As described in Section 3.1, when the P–V curve of a bus has a CP above 0.9 pu, the loadability is determined by the additional load from the current operating point to the maximum loading point. Conversely, if the CP is below 0.9 pu, the loadability is determined by the additional load from the current operating point to the intersection of the P–V curve and the horizontal line indicating the lower voltage limit. Table 2 presents the loadability values for each bus when the generation rate is 30%, with the sum of active load and generation in the base case being 3.71 MW. It is important to note that represents the difference between the initial load and .

Table 2.

Loadability by Deterministic Stability Evaluation.

4.2. Probabilistic Loadability Assessment

In modern power systems, the rapid integration of renewable generation has introduced increasing uncertainty, making stability evaluations more challenging. Traditional deterministic methods may not capture these variations effectively; therefore, it is crucial to model unpredictable factors as probabilistic variables. This approach enables robust decision-making under harsh operating conditions. Consequently, loadability are represented as PDFs that incorporate these probabilistic input factors.

The absolute value of the loadability can be influenced by the random variables involved in generating scenarios for the generation rate or additional load demand. These variations could obscure the evaluation of each bus’s robustness. To address this issue, the loadability of each bus is normalized by expressing it as a ratio relative to the maximum loadability of the P–V curve. This normalized metric, known as the loadability rate (), can be used to indicate voltage stability. Since a bus’s loadability cannot exceed the system’s maximum loadability , the value of ranges from zero to one. Specifically, the loading rate for bus i is calculated using Equation (14).

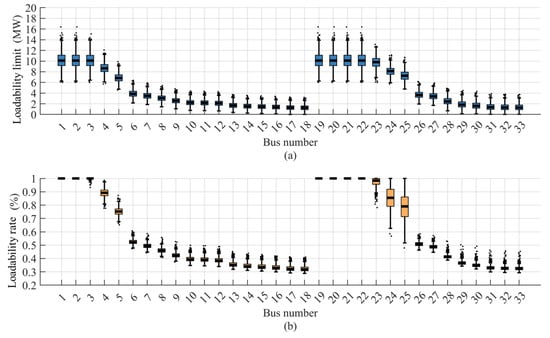

A Monte Carlo simulation with 1000 random scenarios was conducted to assess the probabilistic loadability of the modified IEEE 33-bus test system. These scenarios were generated based on randomized generation rates and load demands. In this study, the number of Monte Carlo scenarios is set to as a compromise between statistical accuracy and computational effort, since each scenario requires a full CPF-based P–V curve analysis of the IEEE 33-bus system under different realizations of PV output and load demand. From standard Monte Carlo theory, the sampling error of estimated probabilities decreases on the order of [31]. For example, when estimating the probability that a given bus becomes insecure (i.e., the load margin falls below the electrolyzer capacity), the worst-case standard error of a binomial estimator with is approximately . This level of accuracy is sufficient for the planning-oriented decisions considered in this work, where the objective is to classify buses as secure or insecure hosting locations rather than to compute extremely precise tail probabilities. Moreover, the adopted scenario size is consistent with existing probabilistic power-system studies, where a few hundred to a few thousand Monte Carlo samples are typically used when each scenario involves computationally intensive AC power flow or CPF-based analyses [31]. Specifically, the generation rate was modeled using a Beta distribution with parameters , while the fluctuations in load demand at each bus were represented by a normal distribution with parameters . The Beta distribution parameters were selected to reflect the typical PV capacity factors observed in Jeju, Korea, during summer midday hours (12:00–14:00) [32], whereas the normal-distribution parameters for load fluctuations were assumed arbitrarily to construct an illustrative uncertainty range. This implies that the standard deviation of the load consumption is 50% of the initial load at bus i.

Figure 8 presents a box plot comparing the absolute loadability and the loadability rates for each bus in the IEEE 33-bus test feeder. Table 3 summarizes these loadability statistically. In the plot, outlier values are marked as black dots. Because the distribution system is connected to the main grid via bus 1, buses electrically closer to bus 1 exhibit high stability. Additionally, the variation in the loadability rate increases with the electrical distance from bus 1. A higher standard deviation in the loadability indicates that those buses are more significantly affected by fluctuations in load or generation. The evaluation results show that buses electrically closer to the main grid (bus 1) tend to exhibit higher voltage stability. In contrast, buses located farther away demonstrate greater variation in their loadability rates. This indicates that such buses are more susceptible to fluctuations in load and generation, as reflected in the higher standard deviation of their load margins.

Figure 8.

The results for probabilistic loadability assessment of the IEEE 33-bus test feeder evaluated with 1000 scenarios: (a) the absolute value of loadability for each bus and (b) the ratio of the maximum loadability for the entire grid to the loadability value, defined as loading rate for each bus i.

Table 3.

Statistics for probabilistic loadability rate of each bus.

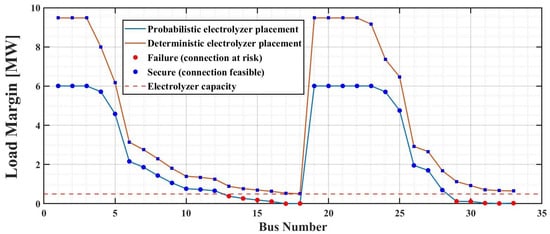

Figure 9 visualizes the load margins at each bus obtained from the deterministic and probabilistic frameworks for the IEEE 33-bus system. The solid and dashed curves correspond to the probabilistic and deterministic load margins, respectively, while the horizontal line at 500 kW represents the electrolyzer capacity. For each bus, red markers indicate that the load margin falls below 500 kW and the electrolyzer connection is therefore classified as a failure (i.e., connection at risk), whereas blue markers indicate that the hosting capacity at that bus is sufficient to accommodate the 500 kW electrolyzer. In the probabilistic framework, the load margin at each bus is evaluated with respect to the worst-case scenario, i.e., the scenario that yields the load margin at each bus. As shown in Figure 9, the deterministic assessment classifies all buses as secure for a 500 kW electrolyzer, because the deterministic load margins remain above 500 kW at every bus. In contrast, the probabilistic assessment identifies several buses (e.g., buses 13–18 and 29–33) where the load margin drops below 500 kW under PV and load uncertainty, and thus the electrolyzer hosting capacity is deemed insufficient. These results are consistent with Table 4 and Table 5, and clearly demonstrate that the proposed probabilistic framework provides a more conservative and risk-aware evaluation of electrolyzer siting than a purely deterministic approach. Table 4 compares the hosting decisions for a 500 kW electrolyzer between the deterministic and probabilistic frameworks. While the deterministic method classifies all 33 buses as secure ( kW), the proposed probabilistic assessment identifies 11 buses as insecure due to their reduced load margins under PV and load uncertainty. The detailed values for these buses are listed in Table 5, which shows that a purely deterministic evaluation would fail to detect locations where the electrolyzer is actually exposed to an insufficient hosting capacity. and denote the load margins obtained from the deterministic and probabilistic frameworks, respectively.

Figure 9.

Comparison of Load Margin at Each Bus between Probabilistic and Deterministic Electrolyzer Placement.

Table 4.

Summary of hosting decisions for a 500 kW electrolyzer in the IEEE 33-bus system.

Table 5.

Buses classified as secure by the deterministic method but insecure by the probabilistic method for a 0.5 MW electrolyzer in the IEEE 33-bus system.

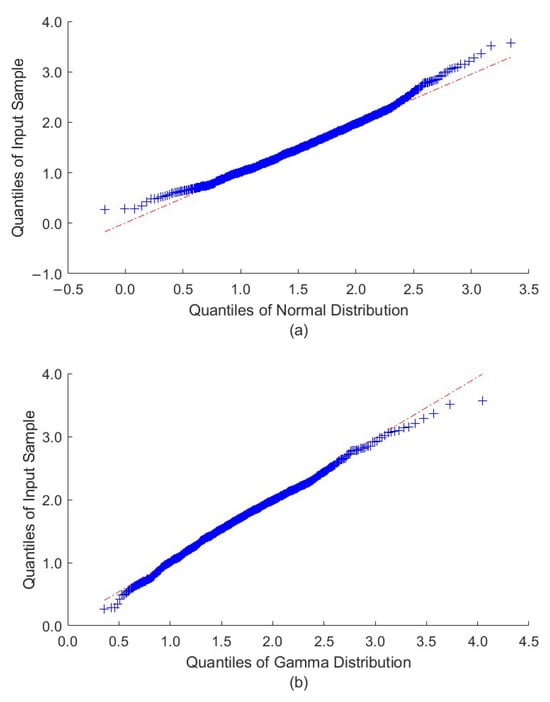

The probabilistic loadability evaluated at bus 14 exhibits a slightly right-skewed distribution. To model this behavior, both standard normal and Gamma distributions were fitted to the calculated sample values. Figure 10 presents the quantile–quantile (Q–Q) plot comparing the sample data with these fitted distributions. In Figure 10a, the data deviate from the diagonal line, indicating a mismatch with the normal distribution. In contrast, Figure 10b shows close alignment with the reference line for the Gamma distribution. Similar patterns were observed at other buses in the system.

Figure 10.

The quantile–quantile plot of the load margin at bus 14 with respect to (a) normal and (b) gamma distributions. The red dotted line represents the theoretical quantiles of each fitted distribution, while the blue plus signs indicate the empirical quantiles of the load-margin samples.

4.3. Electrolyzer Connection Based on Load Margin

The proposed probabilistic loadability quantifies the extra load demand a bus can support while keeping voltage levels within acceptable limits. The loadability rate—defined as the ratio of a bus’s loadability to its maximum loading capacity—offers a comparative measure of voltage stability across the system. A loadability rate closer to one indicates that the bus is capable of accommodating additional load with minimal voltage drop, even in the face of unpredictable generation and load fluctuations.

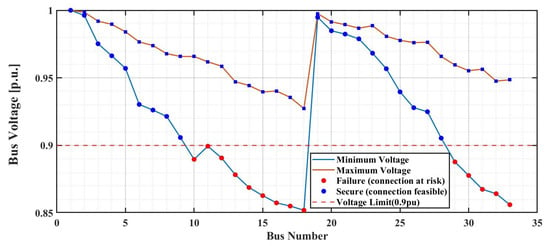

A case study was conducted to demonstrate the relationship between the loadability rate and the voltage security of each bus. In this study, an electrolyzer facility was connected to every bus, and the voltage at each connection point was monitored under various probabilistic scenarios of generation and load demand. Figure 11 provides a visual representation of these results. The curves show the minimum and maximum bus voltages across all scenarios, while the 0.9 p.u. line indicates the voltage limit. Buses marked with red symbols experience a minimum voltage below 0.9 p.u. in at least one scenario and are therefore classified as failure (connection at risk), whereas buses with blue symbols remain above the limit in all scenarios and are classified as secure.

Figure 11.

Minimum and maximum bus voltages across all scenarios in the IEEE 33-bus system when a 500 kW electrolyzer is connected.

Table 6 lists, for each bus in the IEEE 33-bus system, the minimum and maximum voltage magnitudes observed across all scenarios when a 500 kW electrolyzer is connected. The minimum values correspond to the worst-case scenario for each bus in terms of voltage depression, whereas the maximum values represent the most favorable operating condition under the same scenario set.

Table 6.

Minimum and maximum bus voltage magnitudes across all scenarios in the IEEE 33-bus system when a 500 kW electrolyzer is connected.

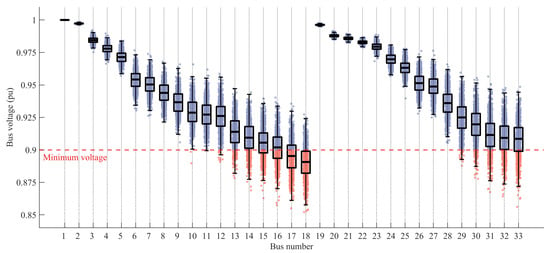

Figure 12 illustrates the voltage distribution under various scenarios of load and renewable generation uncertainty when a 500-kW electrolyzer is connected at each bus, where the 500-kW rating is an illustrative value chosen arbitrarily. For bus i, the Y-axis displays its voltage under the electrolyzer connection. The voltages across multiple scenarios are shown as a boxplot overlaid with a transparent jitter plot in the background. The blue area highlights scenarios where the operating conditions remain within the electrolyzer’s operational voltage range, while the red area marks cases where the voltage at the connection point falls below the minimum threshold, resulting in electrolyzer failure.

Figure 12.

Bus voltages among random scenarios while an electrolyzer connection is applied for the individual bus. The red area indicates the scenarios where electrolyzer failure occurs due to the voltage condition, while the blue area represents the scenarios in which the electrolyzer remains stably connected with the bus voltage staying within the acceptable limits.

Thus, the ratio of the blue and red areas for each bus indicates the probability of electrolyzer failure due to undervoltage at the connection point under uncertainties in renewable generation and load demand. The exact failure ratios for each bus are detailed in Table 7. The results demonstrate that the likelihood of electrolyzer failure increases as the bus is located further from the main grid, highlighting the correlation between electrical distance and voltage stability.

Table 7.

Electrolyzer Failure Rate While Connected to Individual Bus.

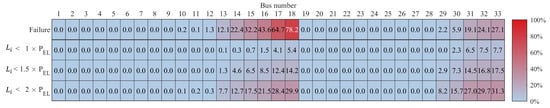

4.4. Electrolyzer Location Evaluation

While the failure rate evaluates voltage security when an electrolyzer is connected to each bus, thousands of power flow calculations are required to assess probabilistic scenarios across the entire grid. This section compares the proposed voltage-sensitive loadability metric and examines its correlation with the voltage security failure rate. Since the P–V curve used to calculate the loadability scales the total load uniformly, the probability of the loadability exceeding the electrolyzer capacity may not exactly correspond to the actual failure rate. To capture different operational margins, electrolyzer capacities of 1, 1.5, and 2 times the base value are considered when computing the ratio.

In Figure 13, the probability that the voltage at the connection point violates the electrolyzer operating range for each bus is compared to the probability that the probabilistic loadability is smaller than 1, 1.5, and 2 times the electrolyzer capacity, . This comparison suggests that while the failure rate must be determined individually for each bus, the probabilistic loadability provides a reliable approximation of this rate. Consequently, employing the probabilistic loadability can significantly reduce the number of calculations required compared to performing a complete probabilistic evaluation of voltage security. As distribution systems grow increasingly complex, the computational benefits of this approach become even more significant. Furthermore, the effectiveness of the proposed probabilistic loadability is validated for the placement of electrolyzers and other voltage-sensitive facilities, ensuring voltage security amidst the inherent uncertainties in distribution systems.

Figure 13.

Comparison of the facility failure rate for 1000 scenarios when an electrolyzer connection is simulated for each bus and the probability that the load margin on each bus is smaller than 1, 1.5, and 2 times the target electrolyzer capacity.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study proposed a probabilistic method for the placement of electrolyzers in renewable-integrated distribution systems, introducing a voltage-constrained load margin that reflects the operating constraints of voltage-sensitive equipment. In contrast to conventional approaches that focus primarily on economic optimization or rely on deterministic voltage stability analysis, the proposed framework explicitly incorporates both supply- and demand-side uncertainties, yielding bus-specific loadability derived from voltage stability considerations.

A key contribution of this work lies in its emphasis on operational reliability rather than purely economic feasibility. Prior studies have either neglected the voltage-sensitive characteristics of electrolyzers or, when considered, evaluated voltage stability without accounting for stochastic uncertainties in generation and load. Such approaches fail to capture the voltage instability that directly impacts the feasibility of connecting sensitive devices such as electrolyzers. In contrast, our method evaluates the vulnerability of individual buses under uncertainty, enabling a more accurate and granular assessment of suitable installation points. Monte Carlo simulations on the IEEE 33-bus system confirm that the proposed metric strongly correlates with actual disconnection risks, offering a computationally efficient yet robust alternative to exhaustive scenario-based analysis.

The methodology provides practical advantages for planning and operation in active distribution networks with high renewable penetration, where uncertainty and spatial variability are pronounced. Future research will expand the framework to incorporate multi-objective optimization, encompassing both economic and operational constraints. Comparative evaluation with other voltage stability indices and application to larger, more diverse systems will further validate its effectiveness and scalability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.W. and S.C.; methodology, H.W., X.Z. and S.C.; software, H.W. and Y.Y.; validation, Y.Y. and J.C.; formal analysis, H.W. and J.C.; investigation, Y.Y.; resources, J.C.; data curation, H.W.; writing—original draft preparation, H.W., X.Z. and S.C.; writing—review and editing, X.Z. and S.C.; visualization, H.W.; supervision, S.C.; project administration, S.C.; funding acquisition, S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP) grant funded by the Korea government (MOTIE) (No. RS-2025-02313547).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Haelee Kim for her valuable contributions to this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Su, J.; Zhang, R.; Dehghanian, P.; Kapourchali, M.H.; Choi, S.; Ding, Z. Renewable-dominated mobility-as-a-service framework for resilience delivery in hydrogen-accommodated microgrids. Int. J. Elect. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 159, 110047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Global Hydrogen Review 2023; Technical Report; IEA: Paris, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Brauns, J.; Turek, T. Alkaline water electrolysis powered by renewable energy: A review. Processes 2020, 8, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernt, M.; Hartig-Weiß, A.; Tovini, M.F.; El-Sayed, H.A.; Schramm, C.; Schröter, J.; Gebauer, C.; Gasteiger, H.A. Current challenges in catalyst development for PEM water electrolyzers. Chem. Ing. Tech. 2020, 92, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.S.; Himabindu, V. Hydrogen production by PEM water electrolysis—A review. Mater. Sci. Energy Technol. 2019, 2, 442–454. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.; Shin, K.; Park, Y.; Yun, Y.H.; Doo, G.; Jung, G.H.; Kim, M.; Cho, W.C.; Kim, C.H.; Lee, H.M.; et al. Catalyst-Support Interactions in Zr2ON2-Supported IrOx Electrocatalysts to Break the Trade-Off Relationship Between the Activity and Stability in the Acidic Oxygen Evolution Reaction. Adv. Func. Mater. 2023, 33, 2301557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, V.M.; Ziar, H.; Haverkort, J.; Zeman, M.; Isabella, O. Dynamic operation of water electrolyzers: A review for applications in photovoltaic systems integration. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 182, 113407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, M.; Sun, J.; Shangguan, Z. Dynamic simulation and performance analysis of alkaline water electrolyzers for renewable energy-powered hydrogen production. Energies 2024, 17, 4915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Kang, M.; Kim, H.T.; Kim, H.; Choi, S.; Choi, B.B. Selecting an Installation Site for MW-Scale Water Electrolysis Systems Based on Grid Voltage Stability. Energies 2025, 18, 2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemeida, M.G.; Alkhalaf, S.; Senjyu, T.; Ibrahim, A.; Ahmed, M.; Bahaa-Eldin, A.M. Optimal probabilistic location of DGs using Monte Carlo simulation based different bio-inspired algorithms. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2021, 12, 2735–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Fosso, O.B.; Marafioti, G. Probabilistic planning of distribution networks with optimal dg placement under uncertainties. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2023, 59, 2731–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, L.A.; Franco, J.F.; Cordero, L.G. A fast-specialized point estimate method for the probabilistic optimal power flow in distribution systems with renewable distributed generation. Int. J. Elect. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 131, 107049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haesen, E.; Bastiaensen, C.; Driesen, J.; Belmans, R. A Probabilistic Formulation of Load Margins in Power Systems with Stochastic Generation. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2009, 24, 951–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, J.C.; Cañizares, C.A.; Bhattacharya, K.; Vaccaro, A. An Affine Arithmetic-Based Method for Voltage Stability Assessment of Power Systems with Intermittent Generation Sources. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2013, 28, 4475–4487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Karra, K.; Mili, L.; Korkali, M.; Chen, X.; Hu, Z. Probabilistic Load-Margin Assessment using Vine Copula and Gaussian Process Emulation. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM), Montreal, QC, Canada, 2–6 August 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Yan, Z.; Shahidehpour, M.; Wang, H.; Chen, S. Power System Voltage Stability Evaluation Considering Renewable Energy with Correlated Variabilities. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2018, 33, 3236–3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, M.S.; Vadhera, S. Probabilistic Steady State Voltage Stability Assessment Method for Correlated Wind Energy and Solar Photovoltaic Integrated Power Systems. Energy Technol. 2021, 9, 2000732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.; Zhao, J.; Xie, L. Transferable Deep Kernel Emulator for Probabilistic Load Margin Assessment with Topology Changes, Uncertain Renewable Generations and Loads. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2023, 38, 5740–5754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Fan, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, G.; Yu, P.; Xiong, G.; Meng, K.; Chen, X.; Zhang, R.; Dong, Z. A Probabilistic Assessment Method for Voltage Stability Considering Large Scale Correlated Stochastic Variables. IEEE Access 2019, 8, 5407–5415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.y.; Sheng, W.; Hu, L.; Liu, Y.; Meng, X.; Jia, D. Simplified probabilistic voltage stability evaluation considering variable renewable distributed generation in distribution systems. IET Gen. Transm. Distrib. 2015, 9, 1464–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morren, J.; Swarts, T. Determining the Optimal Location of Electrolysers in a Medium Voltage Distribution Network; Technical Report; Eindhoven University of Technology: Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Perau, C.; Glaser, K.; Ruppert, M.; Fichtner, W. Strategic Electrolyzer Placement for Green Hydrogen Production in Central Europe: A Comparative Analysis of Res-Driven and Demand-Driven Approaches Using the Synerginet Model. 2023. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4628263 (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Zimmerman, R.D.; Murillo-Sánchez, C.E.; Thomas, R.J. MATPOWER: Steady-State Operations, Planning, and Analysis Tools for Power Systems Research and Education. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2011, 26, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, K.N.; Preece, R.; Milanović, J.V. Existing approaches and trends in uncertainty modelling and probabilistic stability analysis of power systems with renewable generation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 101, 168–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brucoli, M.; La Scala, M.; Torelli, F. A probabilistic approach to the voltage stability analysis of interconnected power systems. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 1986, 10, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundur, P.; Paserba, J.; Ajjarapu, V.; Andersson, G.; Bose, A.K.; Bose, A.; Cañizares, C.A.; Hatziargyriou, N.D.; Hill, D.J.; Stanković, A.M.; et al. Definition and classification of power system stability IEEE/CIGRE joint task force on stability terms and definitions. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2004, 19, 1387–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajjarapu, V.; Christy, C. The continuation power flow: A tool for steady state voltage stability analysis. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 1992, 7, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Chou, S.F.; Blaabjerg, F.; Davari, P. Overview of Power Electronic Converter Topologies Enabling Large-Scale Hydrogen Production via Water Electrolysis. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdloo, F.; Manbachi, M.; Aghamohammadi, M.R. Network loadability maximization by changing the reactance of transmission lines applying Genetic Algorithm and voltage stability considerations. In Proceedings of the 2010 Modern Electric Power Systems, Wroclaw, Poland, 20–22 September 2010; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Baran, M.; Wu, F. Network reconfiguration in distribution systems for loss reduction and load balancing. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 1989, 4, 1401–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billinton, R.; Allan, R.N. Reliability Evaluation of Power Systems, 2nd ed.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Otgongerel, Z.; Baatarbileg, A.; Lee, G. Capacity factor of renewable energy power plants during electric power peak times in Jeju Island. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Transportation Electrification Conference and Expo, Asia-Pacific (ITEC Asia-Pacific), Seogwipo, Republic of Korea, 8–10 May 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).