Abstract

The environmental impact of trade liberalization hinges on a central tension between its ‘scale effect’ and its ‘technique and composition effects’. This study uses the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership’s (RCEP) influence on China-ASEAN green agricultural trade as a quasi-natural experiment to test the net outcome of this conflict. Leveraging panel data from 2003–2023 and a combined Difference-in-Differences (DID) and Instrumental Variables (IV) methodology, we find that while RCEP-driven agricultural expansion (the scale effect) did significantly increase NO2 emissions by 21.80 units (p = 0.011), the total effect of RCEP was counter-intuitively and significantly negative. The agreement produced a context-specific environmental co-benefit, achieving a net reduction of 99.45 of NO2 (p = 0.008). The agreement produced a specific reduction in combustion-related air pollution, achieving a net reduction of 99.45 of NO2 (p = 0.008). We caution that this outcome is contextual: it is driven not only by a still-weak green technology effect (a 0.55 unit reduction, p = 0.095) but more critically by a structural shift in trade towards lower-emission fruit and vegetable products (coefficient = −0.13, p = 0.077), suggesting that environmental gains are currently contingent on product composition rather than broad decarbonization. This reveals that environmental pressures from scale are, for now, being offset by structural optimization, highlighting the urgent need for refined emission monitoring and targeted green policies within RCEP to solidify these environmental gains.

1. Introduction

International trade reshapes production networks and mobility of goods, with well-documented environmental implications [1]. While greenhouse-gas (GHG) mitigation remains central to climate policy, combustion-related air pollutants such as nitrogen dioxide (NO2) provide a high-frequency signal of economic activity and environmental pressure [2,3,4]. This paper examines how RCEP—now the world’s largest regional trade agreement—shaped country-level NO2 among China and ASEAN members through scale, technique, and composition channels in agri-trade.

In the context of global climate change, greenhouse emissions caused by trade activities have received increasing attention [5]. While international trade reallocates resources and promotes economic growth, it also increases combustion-related emissions through the production of goods and cross-border transportation, posing challenges to environmental sustainability [6]. With increased global cooperation, how to reduce the environmental cost while promoting trade has become an important issue for the international community [7].

The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) officially came into effect in 2022, covering the world’s largest free trade zone, including China and the ten ASEAN countries [8]. RCEP aims to promote the free flow of goods, services, and investments within the region by reducing tariffs and non-tariff barriers. Taking the trade of green agricultural products, such as fruits and vegetables, between China and ASEAN as an entry point, the implementation of RCEP has significantly enhanced the connectivity of the regional agricultural product markets [9]. In recent years, agricultural imports from ASEAN countries to China have exhibited a steady upward trend, reflecting a notable expansion in trade flows [10]. Particularly evident is the substantial growth in fruit exports from ASEAN to China, with certain categories such as durians experiencing a pronounced year-on-year increase. These developments underscore the facilitating role of RCEP in enhancing regional agricultural trade and deepening economic integration.

However, the rapid expansion of trade also brings new environmental pressures. RCEP members generally commit to achieving carbon neutrality between 2050 and 2060. Therefore, while accelerating trade exchanges, how to control the carbon emissions arising from them has become an urgent problem. On the one hand, trade liberalization may trigger a “scale effect,” where production expansion promoted by trade could lead to an increase in total carbon emissions [11]. On the other hand, trade may also bring a “technology effect,” where the introduction of efficient technologies and management experience improves production efficiency and thus reduces carbon intensity per unit [12]. Existing research suggests that the full elimination of tariffs among RCEP member countries could lead to a measurable increase in global CO2 emissions associated with fuel combustion [13]. Similarly, while free trade agreements have been found to significantly boost China’s agricultural imports, they also tend to be accompanied by a disproportionately higher rise in combustion-related emissions [14]. These observations underscore the nuanced trade-offs and policy challenges inherent in promoting low-carbon agricultural trade under regional trade frameworks.

Based on this, this paper intends to construct a structured research framework, using quasi-natural experimental empirical identification methods to systematically assess the impact of RCEP’s implementation on carbon emissions in the China-ASEAN green agricultural product trade for fruits and vegetables (Figure 1). The research will start with bilateral trade data, combined with carbon emission accounting models, to identify the trend changes before and after the implementation of RCEP, and analyze the influencing pathways and transmission mechanisms, such as changes in transportation methods, origin substitution effects, and technology diffusion. At the same time, this paper will further explore how to effectively control carbon emissions while expanding green agricultural product trade, and propose targeted policy recommendations to support global low-carbon agricultural trade governance practices.

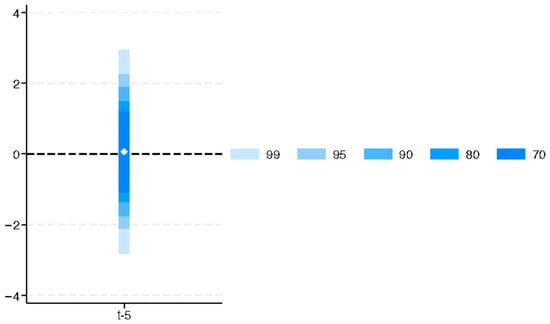

Figure 1.

Parallel Trend Chart. Note: We estimate dynamic leads and lags relative to each country’s RCEP entry-into-force (t = 0), normalizing t = −1. Pre-treatment leads test for parallel trends; post-treatment lags trace adjustment dynamics.

While many studies focus on aggregate CO2 emissions, this study uses nitrogen dioxide (NO2) as the primary environmental indicator for several critical reasons. While CO2 is the primary metric for climate change, Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2) offers a distinct advantage as a high-frequency proxy for combustion-related economic activity and transport intensity. Unlike aggregate CO2 data, which is often estimated annually, NO2 is directly observable via satellite and strongly correlates with the diesel combustion of agricultural machinery and cross-border logistics [15]. Therefore, this study adopts NO2 to capture the immediate environmental footprint of trade facilitation. Further, NO2 emissions in the agricultural sector are directly linked to key activities such as the use of nitrogen-based fertilizers, which is a primary driver of agricultural intensification [16]; NO2 is a major pollutant from the combustion of diesel fuel used in agricultural machinery and the cross-border transportation of goods [17]. Therefore, NO2 serves as a high-frequency, observable proxy for both the on-farm production intensity and the logistical footprint of China-ASEAN green agricultural trade, providing a more nuanced view than aggregate carbon accounting models alone.

This study contributes in three ways. First, we re-position NO2 as an air-pollution/economic-activity indicator and quantify RCEP’s environmental co-benefits using a staggered event-study DID that respects country-specific entry into force. Second, we open the black box by contrasting scale, technique, and composition channels and by linking product-mix shifts—especially toward fruit and vegetables—to changes in NO2 intensity. Third, we strengthen credibility with pre-trend diagnostics, alternative treatment timings, and placebo tests, offering policy-relevant evidence on how trade facilitation can be aligned with cleaner growth.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Relationship Between Trade and Carbon Emissions

With the intensification of global climate change, academic attention to the relationship between international trade and carbon emissions has been increasing. Many studies have pointed out that while international trade promotes the global redistribution of resources, it also increases combustion-related emissions through the production of goods and cross-border transportation, especially in high-emission industries such as agriculture and manufacturing [18,19,20,21]. The processes of trade liberalization and regional economic integration may, while increasing trade volume and economic activities, lead to more carbon emissions, posing challenges to global emission reduction goals [22].

Tian et al. (2022) analyzed the impact of tariff reductions under the RCEP on global CO2 emissions through scenario simulations [23]. The study found that RCEP’s implementation will significantly promote trade and output within the region, and global CO2 emissions are expected to increase by about 3.1%. Particularly in some developing countries, the increase in emissions is more pronounced. This suggests that although RCEP can promote economic growth and trade flows, it may exacerbate the carbon emissions burden, especially in countries with lax environmental regulations.

In contrast, Hu et al. (2024) empirically analyzed the impact of China’s various free trade agreements on implicit carbon emissions in the agricultural sector [24]. The study found that free trade agreements promoted the growth of agricultural imports, but at the same time, the implicit carbon emissions of imported goods also significantly increased, with a cumulative increase of up to 53%. This further highlights the “carbon cost” that trade liberalization may bring, i.e., an increase in carbon emissions.

2.2. The Emission Reduction Effects of Trade and the Diffusion of Green Technologies

While some studies argue that free trade leads to an increase in carbon emissions, other studies emphasize that trade can, under appropriate conditions, help reduce carbon emissions, particularly through the diffusion of green technologies and efficiency improvements. Li et al. (2024) found through research based on interprovincial panel data in China that agricultural trade, while promoting agricultural technological progress and industrial structure optimization, significantly suppressed agricultural carbon emissions [25]. This indicates that under the background of green technology promotion, trade can achieve low-carbon development by improving production efficiency, reducing resource waste, and lowering energy consumption.

Some scholars point out that the trade of green products may initially lead to an increase in combustion-related emissions due to factors like higher production costs for green technologies and energy consumption during transportation [26,27,28]. This phenomenon is known as the “green paradox.” Therefore, scholars suggest that countries should strengthen cooperation and ensure that green trade can truly achieve emission reduction goals through green policies and technological innovation [29,30].

2.3. Environmental Impacts of RCEP

The implementation of RCEP may have significant effects on carbon emissions within the region. RCEP may trigger a “scale effect,” i.e., increased trade leading to an expansion of production and transportation activities, thereby increasing carbon emissions. However, RCEP may also bring a “technology effect” through technology transfer and the promotion of green standards, which can improve production efficiency and reduce carbon emissions intensity per unit, thereby mitigating the growth of emissions [31].

Overall, existing research suggests that international trade, especially the implementation of free trade agreements (such as RCEP), may lead to an increase in carbon emissions, particularly in some developing countries and agriculture-intensive regions [32]. However, trade may also bring emission reduction effects through measures such as the diffusion of green technologies and mutual recognition of green standards. With the rise in green agricultural product trade, assessing the specific impact of RCEP on regional carbon emissions, particularly the carbon footprint of green agricultural product trade, has become an emerging direction for academic research. This study will continue to explore the impact of RCEP on carbon emissions, focusing on its potential in promoting regional green agricultural trade and low-carbon development.

3. Methods

3.1. Research Framework and Objectives

This study aims to evaluate the impact of RCEP on the combustion-related emissions (NO2 emissions) of agricultural crops in various countries after RCEP’s implementation. RCEP officially came into effect in countries like Indonesia and the Philippines in 2023, providing an excellent quasi-natural experimental opportunity. This allows us to utilize the policy shock of RCEP’s implementation to analyze the changes in agricultural NO2 emissions in different countries before and after the policy was implemented. First, we will use Difference-in-Differences (DID) analysis to examine the changes in NO2 emissions in different countries before and after RCEP’s implementation and use these differences to estimate the impact of RCEP on agricultural activities and related carbon emissions. Secondly, we will use Instrumental Variables (IV) method to further eliminate potential endogeneity issues and ensure the accuracy of the policy impact.

3.2. Research Hypotheses

3.2.1. Hypothesis 1 (Scale Effect)

After RCEP’s implementation, the expansion of trade promoted the growth of agricultural production, especially in the production of certain crops. Agricultural production growth is usually accompanied by higher energy consumption and combustion-related emissions. Specifically, the implementation of RCEP promoted the flow of agricultural products within the region, driving the expansion of agricultural production scale, leading to an increase in NO2 emissions.

3.2.2. Hypothesis 2 (Technology Effect)

With the introduction of green technologies, particularly in agricultural production, production efficiency has improved, and the adoption of low-carbon technologies may slow the emission of combustion-related emissions. The implementation of RCEP may have facilitated the diffusion of advanced agricultural technologies (such as energy-efficient irrigation, precision agriculture, and green planting technologies), thus reducing NO2 emissions in agricultural production processes in some regions. See Figure 1.

3.3. Econometric Model and Data

3.3.1. Preliminary Difference-in-Differences (DID)

We will first use Difference-in-Differences (DID) to conduct an analysis by comparing the differences in NO2 emission changes between member and non-member countries before and after RCEP’s implementation, in order to identify the policy’s impact on NO2 emissions [33].

The econometric model is as follows:

- Dependent variable: NO2 (emissions) .

- Core variables:

- post: the virtual variable in which RCEP takes effect (after it takes effect = 1, before it takes effect = 0).

- agri_post: Interaction between agricultural production values and the entry into force of the RCEP (Agri × Post).

- tech_post: Green technology (The total renewable energy usage of each country) interacts with RCEP (Tech × Post).

- agri: Agricultural Production Values.

- tech: green technology variables.

- grainexports: the amount of grain exported to China.

- fruitvegexports: the volume of fruits and vegetables exported to China.

- gdp: GDP value.

- city: The level of urbanization. Divide the urban population by the total population.

- : National fixed effect.

- : Time fixation effect.

- : Random error term.

3.3.2. Instrumental Variables (IV) Method

When using the Difference-in-Differences (DID) method, there are potential endogeneity issues, particularly the possible interrelationship between agricultural production expansion and combustion-related emissions [34]. The increase in agricultural production may be driven by multiple factors, including policy changes, market demand, and other unobserved factors. These factors may simultaneously affect both combustion-related emissions and agricultural production expansion, leading to endogeneity problems. Therefore, we need to introduce instrumental variables to address this issue.

In this study, we choose the geographical distance from the ten ASEAN countries to China as an instrumental variable. We argue that geographical distance satisfies the exclusion restriction required for a valid instrument. Geographical distance is a static, exogenous geographic feature that does not directly dictate a country’s domestic environmental policies or agricultural production intensity (NO2 levels). Its influence on emissions is mediated almost exclusively through the channel of trade volume and the associated logistics intensity. While distance affects transport emissions, this is precisely the ‘scale effect’ of trade we aim to capture, rather than a confounding omitted variable, making it a valid exogenous instrument [19]. Generally, countries that are geographically closer tend to have higher trade volumes. Moreover, distance is time-invariant and is absorbed by country fixed effects; our identification relies on its interaction with post-RCEP trade changes rather than any direct, time-varying impact on NO2. Therefore, the distance from the ASEAN countries to China can reflect the trade intensity between these countries and China, especially under the RCEP framework. At the same time, geographical distance itself does not directly affect agricultural production or combustion-related emissions, making it a suitable instrument for capturing changes in trade flows without directly influencing NO2 emissions.

IV Model Design

Based on the DID model, we will use geographic distance as an instrumental variable to estimate the impact of RCEP on NO2 emissions. The IV model will predict agricultural product trade volume (such as grain and fruit/vegetable exports) through geographic distance, thereby addressing the endogeneity issue between trade volume and NO2 emissions.

Specifically, our IV model consists of two stages:

Phase 1 (Forecasting Agricultural Exports):

- GrainExports: The volume of cereals exported by country by year it.

- Post: After the implementation of the policy, the dummy variable is 1 in the year after the RCEP takes effect, and 0 before the effective date .

- : Country Geographical distance to China .

- : Control variables such as GDP growth rate, energy consumption, etc.

- : National fixed effect.

- : Time fixation effect.

- : Random error term.

Stage 2 (Return to Emissions):

- GrainExportsit: The volume of grain exports predicted by the first phase (trade volume predicted using geographical distance) it.

- FruitVegExports: Forecasted fruit and vegetable export volumes using the same methodology it.

- Other variables: as in the DID model, including agricultural production expansion, technology introduction, control variables, and fixed effects.

- All monetary trade and production variables (agricultural exports, agricultural output, and sectoral trade values) enter the regressions in natural logarithms. When zero values occur, we adopt the transformation ln(1 + value) to retain observations.

3.3.3. Data

We compile an annual panel for China and ASEAN members from 2003–2023. The outcome is a country-level NO2 indicator (unit and source to be specified precisely), capturing combustion-related activity. Our dependent variable is the annual average tropospheric NO2 column density. We use daily Level-3 gridded satellite products released by NASA and ESA. For 2005–2018, we rely on the Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI) tropospheric NO2 column product (OMNO2d), which provides global coverage at a native nadir resolution of approximately 13 km × 24 km and is expressed in units of mol/m2. For 2018 onward, we use the Sentinel-5 Precursor TROPOMI tropospheric NO2 column product, which offers substantially finer spatial resolution (7 km × 3.5 km, improved to about 5.5 km × 3.5 km after August 2019) in the same physical units. We apply the recommended quality-flag filters to remove pixels affected by clouds, snow/ice, and retrieval artefacts (including the OMI row anomaly), and then aggregate daily pixels to annual country-level means using an area-weighted average over land grid cells that fall within each country’s borders. The resulting panel of annual tropospheric NO2 column densities (mol/m2) is interpreted as a high-frequency indicator of combustion-related air pollution associated with agricultural production and transport, rather than as a direct measure of ground-level concentrations.

RCEP treatment is coded at the country level with the exact entry-into-force year (staggered adoption). We construct our dependent variable using the tropospheric NO2 vertical column densities () derived from the Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI) and TROPOMI satellite sensors, accessed via the KNMI TEMIS database. Covariates include agricultural production (value), a green-technology proxy (e.g., renewable-energy penetration), bilateral exports of cereals and of fruits & vegetables to China, GDP, and urbanization. Full variable definitions and suggested sources are summarized in Table 1. We pre-specify data transformations (e.g., logs where appropriate) and will align trade product codes with a transparent “green agritrade” list for reproducibility.

Table 1.

Variable Definitions.

Given that all raw NO2 and CO2 series are directly downloadable from publicly accessible databases (TROPOMI/OMI, WDI, etc.), and can be exactly reconstructed following Table 1, we do not provide an additional compiled dataset.

4. Results

Figure 1 shows no statistically significant pre-trends, while post-RCEP coefficients turn negative on average. In pooled post-treatment contrasts, NO2 declines on average after entry into force. Mechanism splits reveal that agricultural-production expansion is positively associated with NO2 (scale), green-technology uptake is negatively associated (technique), and higher fruit-and-vegetable export intensity correlates with lower NO2 (composition).

We further estimate the DID econometric model using the reghdfe command, and the results are shown in Table 2 and Table 3. RCEP itself may reduce combustion-related emissions (p = 0.065), with the mechanisms including scale effects and technological effects. The scale effect increases combustion-related emissions through the expansion of agricultural production (p = 0.069), while the technological effect reduces emissions through the application of green technologies (p = 0.157). However, the impact of the scale effect is much larger than that of the technological effect, and the emission reduction effect of the technological effect is statistically insignificant.

Table 2.

DID Regression.

Table 3.

DID Regression Result.

Considering endogeneity, we further use instrumental variables (IV) for a two-stage estimation. Table 4 reports the first-stage results for the IV specification where current grain exports to China (grainexports) are instrumented with the interaction between bilateral geographic distance and the post-period dummy (distance × post). The coefficient on distance × post is positive and statistically significant at the 1% level (0.481 with a standard error of 0.064), indicating that, after the policy shock, more distant RCEP members experienced relatively larger increases in grain exports to China compared with geographically closer partners. The regression includes both country and year fixed effects, so identification comes from within-country variation over time relative to common shocks. The first-stage F-statistic on the instrument is 56.61, well above conventional thresholds for weak-instrument concerns, suggesting that geographic distance interacted with the post dummy is a strong predictor of grain exports in our sample of 200 country–year observations (R2 = 0.38).

Table 4.

First-stage regressions (geographic distance instrument).

The full IV results are shown in Table 5. It can be observed that the coefficients have changed significantly.

Table 5.

The IV Estimation.

While we prioritize the IV estimates to address potential endogeneity, it is worth noting that the standard Two-Way Fixed-Effects (TWFE) DID results in Table 2 present a directionally consistent finding (negative coefficient for RCEP). This robustness across both OLS and IV specifications strengthens our confidence that the observed emission reduction is not an artifact of model specification.

We computed variance inflation factors (VIFs) for the DID–IV specification with interaction terms. After mean-centering the logarithms of agricultural output and exports before constructing the interactions, the VIFs fall into an acceptable range: in our benchmark specification, the maximum VIF is about 7.21, while the VIFs for the underlying log variables remain around 6, reflecting the high but expected correlation between production and trade.

Further, we argue that the reliability of our estimates is fundamentally ensured by the exogenous nature of the RCEP policy shock, which serves as a quasi-natural experiment. The specific entry-into-force dates for each member country were determined by complex, high-level diplomatic negotiations and legislative ratification processes. These political timelines are strictly exogenous to the annual variations in agricultural production decisions or NO2 emission levels of any single nation. It is implausible that a country would time its treaty ratification based on that specific year’s agricultural pollution intensity.

5. Discussion

Our evidence indicates air-quality co-benefits after RCEP’s implementation, conditional on technology diffusion and product-mix shifts offsetting scale pressures. While we refrain from interpreting NO2 as a greenhouse-gas outcome, the results are consistent with cleaner combustion and operational efficiency associated with trade facilitation and green-technology uptake. Targeted policies that accelerate green-technology diffusion and incentivize lower-emission product mixes can strengthen these co-benefits.

5.1. Comparison of Scale Effects and Technological Effects

Our empirical specification is designed to map onto the standard decomposition of trade–environment linkages into scale, technique, and composition effects. The coefficient on Agri × Post reflects how RCEP-induced expansion of agricultural output scales up combustion-related activities such as fertilizer use, mechanization and cross-border logistics, thereby increasing tropospheric NO2 columns. The interaction Tech × Post captures the extent to which cleaner technologies—including more efficient irrigation, low-emission machinery and better input management—reduce emissions per unit of output and thus operate as a technique effect. Finally, the interaction terms involving agricultural trade composition—for example fruit and vegetable exports and their shares in total exports—measure whether RCEP is associated with a reallocation of exports toward products with lower embodied emissions and potentially shorter shipping distances, generating a composition effect.

In our DID-IV estimates, the scale channel remains positive and statistically significant, indicating that RCEP does indeed expand agricultural production and associated emissions pressures. However, the composition channel is negative and economically meaningful, suggesting that shifts toward green agritrade partially offset these pressures. The technique channel is positive but statistically weaker, consistent with the notion that technology upgrading in green agriculture is underway but has not yet fully caught up with the scale of trade expansion over our observation window.

In the OLS model before IV, the coefficient of post is −99.2539 (p = 0.034), indicating that, on average, NO2 emissions decreased by 99.2539 units after the implementation of RCEP (the unit depends on the definition of no2, e.g., it could be tons per million tons), which is statistically significant at the 5% level (p < 0.05). This suggests that RCEP may have reduced NO2 emissions through mechanisms such as trade structure adjustments and technological cooperation. In the IV model, the coefficient of post slightly changes to −99.4493 (p = 0.008), with the coefficient remaining almost unchanged, but the significance improves significantly (the p-value decreases from 0.034 to 0.008, significant at the 1% level). This change indicates that after controlling for the endogeneity of grainexports, the emission reduction effect of RCEP becomes more significant. The IV method, using an instrumental variable (grain_exports_hat, predicted by geographic distance), reduces endogeneity bias, improving the precision of the estimates (the standard error decreases from 39.61151 to 37.43471, and the z-statistic improves from −2.51 to −2.66). This supports the conclusion that RCEP itself reduces combustion-related emissions, with the IV results providing stronger statistical evidence.

The scale effect (Agri × Post) presents a significant positive coefficient (21.797, p = 0.011), confirming that agricultural expansion remains the primary driver of emission growth. Conversely, the technological effect (Tech × Post) shows a negative coefficient (−0.554, p = 0.095). Although statistically significant in the IV specification, its magnitude is considerably smaller than the scale effect, indicating that green technology diffusion has not yet reached a level sufficient to fully counteract production pressures.

The technological effect is measured by tech_post (Tech × Post), representing the additional impact of green technology (tech) on NO2 emissions after the implementation of RCEP. In the OLS model, the coefficient of tech_post is −0.6540603 (p = 0.132), indicating that for each unit increase in tech, NO2 emissions decrease by 0.6540603 units after RCEP’s implementation, but this effect is not statistically significant (p > 0.1). In the IV model, the coefficient of tech_post changes to −0.5537098 (p = 0.095), with the coefficient slightly decreasing, but its significance improving (the p-value decreases from 0.132 to 0.095, significant at the 10% level). This suggests that RCEP may have reduced NO2 emissions through technological cooperation and the promotion of green technologies (e.g., renewable energy use, energy-saving technologies). The IV model reduces endogeneity bias, making the emission reduction effect of the technological effect more statistically significant, but its impact remains small (the absolute value of the coefficient is only 0.5537098). This aligns with the previous conclusion that the technological effect reduces combustion-related emissions through the application of green technologies, but its effect is still statistically weak.

The key in the IV model is the use of grain_exports_hat (the fitted value of grainexports predicted by geographic distance) as an instrument to solve the endogeneity issue of grainexports. In the OLS model, the coefficient of grainexports is 0.0152021 (p = 0.790), which is not statistically significant, indicating that food exports have a very small direct impact on NO2 emissions. However, grainexports may suffer from endogeneity problems, such as NO2 emissions potentially affecting food exports in the opposite direction (high-emission countries may reduce exports to cope with environmental pressures), or unobserved factors (such as global food demand) simultaneously affecting both grainexports and no2. The IV model, using geographic distance (e.g., the distance from ASEAN countries to China) to predict grainexports, generates the exogenous variable grain_exports_hat, with a coefficient of 0.6709154 (p = 0.760), which is still not statistically significant. This suggests that food exports have indeed a small direct impact on NO2 emissions, but the IV method, by controlling for endogeneity, improves the precision of estimates for other variables (post, agri_post, tech_post) (the standard error decreases, and significance increases). Geographic distance serves as a strong instrument (assuming it is highly correlated with grainexports), enhancing the statistical power of the model.

In the IV model, the coefficients and significance of other covariates (fruitvegexports, gdp, city) also change. The coefficient of fruitvegexports changes from −0.173809 (p = 0.107, OLS) to −0.1335474 (p = 0.077, IV), with significance slightly improving (significant at the 10% level), suggesting that the negative impact of fruit and vegetable exports on NO2 emissions is more significant, possibly because their production activities are less associated with high-emission industries. The coefficient of gdp changes from 4.190825 (p = 0.114, OLS) to 1.717459 (p = 0.727, IV), with a significant reduction in significance, suggesting that after controlling for the endogeneity of grain exports, the positive impact of GDP growth on NO2 emissions is no longer significant, possibly because the IV model reduced the spurious correlation between GDP and emissions. The coefficient of city changes from 58.54973 (p = 0.124, OLS) to 39.9998 (p = 0.095, IV), with slight improvement in significance (significant at the 10% level), but the impact weakens, suggesting that urbanization’s positive effect on NO2 emissions is partially diminished in the IV model. These changes reflect how the IV method, by controlling for endogeneity, redistributes the causal effects between variables.

RCEP itself significantly reduces combustion-related emissions (p = 0.008), with mechanisms including scale effects and technological effects. The scale effect increases emissions through agricultural production expansion (p = 0.011), while the technological effect reduces emissions through the application of green technologies (p = 0.095), but the impact of the scale effect is much larger than that of the technological effect.

5.2. Composition Effects and Trade Reallocation

Our IV results indicate a significant negative correlation between fruit and vegetable exports and NO2 levels (p = 0.077), whereas grain exports show no significant impact. While we lack granular farm-level data to definitively confirm a technological upgrade in production methods, this divergence strongly suggests a ‘composition effect.’ The implementation of RCEP appears to have incentivized a reallocation of trade volume towards less emission-intensive crop categories (fruits and vegetables) and potentially more efficient logistic supply chains. This shift in the product mix—rather than a uniform reduction in emission intensity across all sectors—likely drives the observed net reduction in pollutants.

The reason for overlooking the composition effect is not an issue of model design, but rather statistical and data limitations. First, the granularity of the statistical data is insufficient. The current data only includes total agricultural production (agri), food exports (grainexports), and fruit and vegetable exports (fruitvegexports), without breaking down the data into specific agricultural products (such as rice, palm oil, fruits) or production methods (traditional agriculture vs. modern agriculture). This prevents the model from directly capturing structural changes within the agricultural sector, such as changes in the proportion of high-emission rice production to low-emission fruit production, or measuring shifts in production methods (such as the increase in organic farming) or changes in trade patterns (such as shortened transportation distances). If the data were detailed at these levels, the structural effects could be clearly captured through new variables, allowing for a more accurate decomposition of RCEP’s environmental effects.

Secondly, the short time span of the data limits the identification of composition effects. Structural effects typically take longer to materialize. For example, adjustments in agricultural production structure may take several years, while the data after RCEP’s implementation may cover only a short period (e.g., 1–2 years). This makes it difficult for the model to capture long-term structural changes, such as the gradual transformation from traditional agriculture to modern low-emission agriculture or shifts in trade patterns from long-distance transportation to regional short-distance trade.

Although our aggregate model does not strictly decompose the ‘composition effect’ versus ‘comparative advantage effect,’ the significant negative coefficient for fruit and vegetable exports (−0.13, p = 0.077) compared to the null effect of grain exports strongly implies an intra-sectoral shift. This suggests that RCEP has incentivized a reallocation of resources towards lower-emission crop types, rather than merely outsourcing dirty production to other nations.

5.3. Policy Recommendation

5.3.1. Strengthen Regional Coordination Mechanisms for Agricultural Emissions

This study finds that the implementation of RCEP itself has a significant combustion-related emissions mitigation effect. To further consolidate this outcome, it is recommended that a regional agricultural emission governance framework be established within RCEP. This could include carbon data sharing, mutual recognition of emission accounting standards, and enhanced transparency. Drawing on the EU’s carbon accounting practices, the region could develop an “Emissions Accounting Guideline for Agriculture” and publish annual “Trade Carbon Footprint Reports,” encouraging member states to align market openness with environmental responsibility and prevent carbon leakage across borders.

5.3.2. Mitigate Emissions Growth from Agricultural Scale Expansion

Empirical results indicate that the expansion of agricultural production following RCEP implementation leads to a more pronounced increase in emissions (scale effects dominate technological effects). To address this risk, countries should strengthen regulatory oversight of high-emission agricultural inputs, establish emission control thresholds for agricultural expansion, and adopt differentiated green subsidy policies. For instance, environmental impact assessments could be required for expanding rice or palm oil cultivation, while fiscal incentives could be offered for low-carbon practices such as drip irrigation or organic fertilizer use. These measures would steer agricultural growth toward sustainability and help control scale-driven emissions.

5.3.3. Promote the Diffusion of Green Agricultural Technologies Across the Region

Although the technological effect exists, its impact is weak and statistically insignificant. This suggests that green technologies have not yet formed a systemic influence. It is recommended to establish a “Green Agricultural Innovation Alliance” under the RCEP economic and technical cooperation framework. The alliance could focus on joint R&D and demonstration projects in areas such as energy-efficient farm equipment, bio-fertilizers, precision agriculture, and carbon sequestration in farmland. A regional green technology list and cross-border transfer mechanism should also be created to facilitate the adoption of advanced technologies—particularly from China—across ASEAN countries, enhancing the region’s overall mitigation capacity.

6. Conclusions

This study finds that the implementation of RCEP contributes to an overall reduction in agricultural combustion-related emissions, primarily driven by regional technological cooperation and trade structure optimization. On the one hand, the promotion of green technologies plays a role in curbing emissions; on the other hand, the increase in exports of low-emission agricultural products such as fruits and vegetables may be pushing the sector toward a lower-carbon structure. However, this reduction effect is still offset to some extent by increased emissions caused by agricultural expansion, indicating that while RCEP has begun to promote greener agricultural development, stronger policy guidance and supporting mechanisms are still needed. It is important to note that these co-benefits are observed specifically in NO2 emissions and are largely driven by the specific trade composition of fruits and vegetables. These findings should not be automatically extrapolated to aggregate GHG emissions (CO2) or other heavy-industry sectors without further verification.

We acknowledge that national renewable energy usage is a broad proxy for specific agricultural green technologies. However, due to the lack of consistent cross-country data on agricultural electrification or precision farming equipment in the ASEAN region, we use the national renewable share as a macro-level indicator of a country’s overall capacity to adopt cleaner production technologies. Future research should aim to utilize sector-specific technological indicators.

In addition to scale and technological effects, the potential role of structural adjustments in reducing emissions should not be overlooked. RCEP may be gradually facilitating a shift from high-emission to low-emission and modern agricultural practices among its members. However, due to current limitations in data granularity and the short time span since implementation, these structural effects remain difficult to capture. Going forward, efforts should be made to collect more detailed data on crop types, production methods, and transport routes, thereby improving the region’s capacity for emission monitoring and policy evaluation. This would allow for a more systematic promotion of green agricultural transformation and support the dual goals of economic development and environmental protection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.W.; Methodology, Y.Y.; Software, X.W.; Formal analysis, M.X., X.W. and H.W.; Investigation, M.X.; Resources, Y.Y.; Data curation, Y.G., X.W. and H.W.; Writing—original draft, Y.G. and H.W.; Writing—review & editing, Y.G., H.W. and Y.W.; Project administration, Y.W. and X.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2024YFC3713500), Shanghai University Young Talents Sailing Program (N.13-G210-23-251).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets analyzed in this study are publicly available online from the sources cited in the text. No further data are provided by the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Meng Xu is from the Institute of Electronic Computing Technologies, China Academy of Railway Sciences Corporation Limited. The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ganapati, S.; Wong, W.F. How far goods travel: Global transport and supply chains from 1965–2020. J. Econ. Perspect. 2023, 37, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keola, S.; Hayakawa, K. Do lockdown policies reduce economic and social activities? Evidence from NO2 emissions. Dev. Econ. 2021, 59, 178–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Yammahi, A.; Aung, Z. A study of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) periodicity over the United Arab Emirates using wavelet analysis. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 18144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichler, R.; Bittner, M. Comparison between economic growth and satellite-based measurements of NO2 pollution over northern Italy. Atmos. Environ. 2022, 272, 118948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; He, R. The Impact of Carbon Emissions Trading Policy on the ESG Performance of Heavy-Polluting Enterprises: The Mediating Role of Green Technological Innovation and Financing Constraints. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, M.E.; Karim, R.; Islam, M.T.; Muhammad-Sukki, F.; Bani, N.A.; Muhtazaruddin, M.N. Renewable energy for sustainable growth and development: An evaluation of law and policy of Bangladesh. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Wang, Y. Globalization and environment: Effects of international trade on emission intensity reduction of pollutants causing global and local concerns. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 297, 113249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, S.; Drysdale, P. The Implications of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership for Asian Regional Architecture. In RCEP: Implications, Challenges, and Future Growth of East Asia and ASEAN; Jakarta ERIA: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2022; pp. 247–267. [Google Scholar]

- Bin, L.; Jiawei, L.; Aiqiang, C.; Theodorakis, P.E.; Zongsheng, Z.; Jinzhe, Y. Selection of the cold logistics model based on the carbon footprint of fruits and vegetables in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 334, 130251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, M.; Khan, F.; Devadason, E.S. Agri-food trade channel and the ASEAN macroeconomic impacts from output and price shocks. Agric. Econ. 2024, 55, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Jiang, Z. Exploring the impact of trade openness on carbon emissions: Do scale, environmental regulations, and structural effects matter? Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Hu, S.; Li, R. Could information and communication technology (ICT) reduce carbon emissions? The role of trade openness and financial development. Telecommun. Policy 2024, 48, 102699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idroes, G.M.; Rahman, H.; Uddin, I.; Hardi, I.; Falcone, P.M. Towards sustainable environment in North African countries: The role of military expenditure, renewable energy, tourism, manufacture, and globalization on environmental degradation. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 368, 122077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Liu, Y.; Bezama, A.; Thrän, D. Agricultural carbon emission efficiency and agricultural practices: Implications for balancing carbon emissions reduction and agricultural productivity increment. Environ. Dev. 2024, 50, 101004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loreto, V.; Haklay, M.; Hotho, A.; Servedio, V.D.; Stumme, G.; Theunis, J.; Tria, F. Participatory Sensing, Opinions and Collective Awareness; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, B.; Karimi, M.S.; Mohammed, K.S.; Shahzadi, I.; Dai, J. Nexus between climate change, agricultural output, fertilizer use, agriculture soil emissions: Novel implications in the context of environmental management. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 450, 141801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, F.S. A Comprehensive Analysis of Air Pollution in Dhaka City, Bangladesh, and the Application of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning for Enhanced Management and Forecasting. Int. J. Appl. Nat. Sci. 2025, 3, 131–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, G.; Huang, M.; Sun, C. Revealing the hidden carbon flows in global industrial sectors—Based on the perspective of linkage network structure. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 356, 120531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chen, Y.; Pei, X. Can agricultural trade openness facilitate agricultural carbon reduction? Evidence from Chinese provincial data. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 441, 140877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evro, S.; Oni, B.A.; Tomomewo, O.S. Global strategies for a low-carbon future: Lessons from the US, China, and EU’s pursuit of carbon neutrality. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 461, 142635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, J.-M.; Kass-Hanna, T.; Masterson, L.; Paret, A.-C.; Thube, S.D. Cross-Border Impacts of Climate Policy Packages in North America; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, F.; Li, R. Free trade and carbon emissions revisited: The asymmetric impacts of trade diversification and trade openness. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 876–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, K.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Ming, X.; Jiang, S.; Duan, H.; Yang, C.; Wang, S. Regional trade agreement burdens global carbon emissions mitigation. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Zou, Z.; Wu, J.; Meng, Z. Double-edged sword: China’s free trade agreements reinforces embodied greenhouse gas transfers in agricultural products. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Dou, W.; Han, J.; Zhang, W. Industrial structure optimization and green growth in China based on a population heterogeneity perspective. In Natural Resources Forum; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lenzen, M.; Dey, C.J. Economic, energy and greenhouse emissions impacts of some consumer choice, technology and government outlay options. Energy Econ. 2002, 24, 377–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liobikienė, G.; Butkus, M. Scale, composition, and technique effects through which the economic growth, foreign direct investment, urbanization, and trade affect greenhouse gas emissions. Renew. Energy 2019, 132, 1310–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, D.L.; Baker, H.H., Jr.; Plotkin, S.E. Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions from US Transportation; National Transportation Library’s Repository: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M.; Salzman, J. The next generation of trade and environment conflicts: The rise of green industrial policy. Northwest. Univ. Law Rev. 2013, 108, 401. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, B.; Wang, S. Opening up, international trade, and green technology progress. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 1002–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiral, M.; Demiral, Ö. Global value chains participation and trade-embodied net carbon exports in group of seven and emerging seven countries. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 347, 119027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Research Council, Division on Earth, Board on Atmospheric Sciences, Committee on Methods for Estimating Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Verifying Greenhouse gas Emissions: Methods to Support International Climate Agreements; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, M.; Crossley, T.F.; Joyce, R. Inference with difference-in-differences revisited. J. Econom. Methods 2018, 7, 20170005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Zhang, C.; Song, H.; Wang, Q. How does emission trading reduce China’s carbon intensity? An exploration using a decomposition and difference-in-differences approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 676, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).