Abstract

Agriculture is a sector that is subject to regulation and far-reaching public intervention, especially in developed countries. In Poland, a country that passed through a system transformation, inclusion in the European Union’s (EU) Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) mechanisms and the internal market has resulted in positive and multi-dimensional effects for farmers and rural development. This fact is reflected in the evolution of farmers’ attitudes toward the EU, changing from opposition and distrust to acceptance and support. The purpose of the paper is to trace shifts in the political dynamics surrounding the CAP and EU membership among farmers, and to explore their causes. The findings suggest that, following the most recent policy reform—which involved increased environmental and climate commitments alongside market uncertainty—farmers have begun to lean towards a Eurosceptic orientation once more, whilst simultaneously demonstrating ambivalent attitudes towards the CAP. In light of the fragmented representation, the recent protests highlighted a mobilization of grassroots efforts in the pursuit of farmers’ interests. Hence, a question arises regarding the stability of this critical perspective, particularly in the context of future reforms to CAP as well as the economic and climate-related challenges for sustainable agricultural development. This study is based on a literature review alongside economic and social data derived from surveys and public statistics.

1. Introduction

To date, different models of the relationship between the state and the agricultural sector have emerged. Generally, a regularity is observed whereby in economically developed countries, where the contribution of agriculture to GDP and employment is small, the level of interventionism and subsidisation of food production remains significant [1]. This is accompanied by an extensive regulatory and administrative mechanism. One example of how such a model for the functioning of the agricultural sector works is the EU, whose CAP, with its substantial budget, influences the situation on agricultural markets, subsidises production, and treats farms as an important element in achieving overall policy goals. Under the conditions of a globalised and financialised world economy, such an approach ensures the relative sustainability of the agri-food sector (European Agricultural Model) and food security. Nevertheless, it creates an inertial institutional order and reproduces the largely clientelist relations between public authority and farmers, referred to as an agricultural welfare state [2].

Polish agriculture has been operating within the EU CAP for two decades. During this period of unprecedented support and development of the agri-food sector, as well as implementation of modern agricultural and rural policy instruments, multidirectional processes of transformation of the agri-food system have occurred. As a result, a group of entrepreneurial farmers and food industry companies successfully operating in the common European market has emerged [3]. Irrespective of the scale of changes resulting from economic transformation and integration with the EU, many elements related to agricultural structures and farmers’ attitudes have become relatively stable. For example, the fragmentation and polarisation of family farms, the conservative-right ideological formation of farmers, their reluctance to cooperate in the market and political sphere, the belief in the need for regulation of markets and interventionism, and the widespread sense of socio-political alienation have remained relatively strong. The sources of persistence of these structures, orientations, and characteristics are diverse. Some are rooted in the past as part of a long history of informal and formal institutions (path dependency) [4]. For example, the relatively low level of trust Polish farmers exhibit in public institutions, and their reluctance to cooperate in business with other farmers to improve their bargaining position within the food chain (i.e., horizontal integration), are linked to the negative experience of formal collaboration during the time of communism and transition to market economy [5]. The dynamics and continuation of these structures, attitudes, and actions of farmers in Poland are well reflected in their relations with the EU CAP, ranging from opinions to practices expressed in the market, political, and social domains.

In this context, the purpose of the paper is to identify changes in Polish farmers’ attitudes towards the EU CAP and to explore selected economic, social, political, and cultural causes. This work also attempts to determine the policy implications of farmers’ changing attitudes towards the EU against the background of increasing socio-economic divisions and the evolution of public discourses on agriculture, rural development, and agricultural policy.

The paper presents farmers’ attitudes towards the EU and CAP in three subsequent periods:

- Transition and preparation for European integration (1989–2003);

- Poland’s EU accession and subsequent integration into the CAP framework (2004–2022);

- The recent CAP reform and the crisis in agricultural markets (2023–2024).

In each of these time periods, an attempt was made to present the economic and social determinants of specific orientations and practices towards the EU and CAP, which followed a simplified pattern: from concern through support to opposition.

The article is structured as follows. The next section briefly presents the data, method, and theoretical framework used in the study. The subsequent section focuses on economic transformation in Poland as an important context for shaping farmers’ attitudes towards EU CAP. Afterwards, the main reasons behind farmers’ increasing support for the EU CAP are explored. The following section identifies the motives for the shift in support for the EU CAP amongst farmers in 2023–2024, taking the form of growing criticism and opposition. The final section concludes with findings and policy reflections.

2. Materials and Methods

To examine changes in policy dynamics concerning the EU membership and the CAP amongst Polish farmers, the results from a series of social surveys, public statistics and academic literature were analysed.

The survey results were based on samples representative of the entire population and conducted by the Public Opinion Research Centre (CBOS). Across the selected waves of this research, the sample size varied, ranging from 937 to 1157 respondents. EU membership supporters were defined as the group of respondents who answered ‘I support’ to the question: ‘Do you personally support Poland’s membership in the European Union or are you against it?’ Other possible responses were ‘I am against’ and ‘Difficult to say’ [6,7,8].

Data on the economic situation in the agricultural sector were derived from official statistics (Statistics Poland) and included the index of price relations (‘price gap’), which constitutes the ratio of the price index of sold agricultural products to the price index of purchased goods and services [9].

Information to explore and interpret the observed changes in farmers’ attitudes towards the EU and CAP came primarily from the literature on the subject. The assessment of conclusions from research conducted so far was made in a scoping manner (scope literature review) [10]. The scoping literature review consisted of mapping relevant academic literature on a given topic and selecting and synthesizing conclusions resulting from it [11,12]. The research material relating to the diagnosis and assessment of farmers’ attitudes towards Poland’s EU membership and the CAP comprised thirty-eight purposefully selected and frequently cited scientific and expert papers, identified according to the Arksey and O’Malley framework [11,13]. The search strategy was flexible and involved an iterative process of identifying studies relevant to the research problem using the Google Scholar search engine. The article search employed keywords and phrases in both Polish and English, including ‘farmers and EU’, ‘farmers and CAP’, ‘farmers’ attitudes and EU accession’, ‘farmers’ attitudes and the CAP’, ‘farmers’ attitudes and EU membership’, and ‘agricultural protests’. The scope of these publications concerned mainly work by Polish scientists written in Polish and English in the field of social sciences, including rural sociology, rural studies, agricultural economics and political science and administration.

The study also employed a theoretical framework for identifying collective action by social groups, which included three aspects: genetic (reasons for the emergence of protest, possibilities for mobilization of farmers, identification of the category/membership base of the protest); structural (characteristics of collective action, i.e., method of organization, programme, scale of action); and functional (effects of collective action and its function in society) [14].

Political Representation of Polish Farmers: A Subject of Study

To understand the attitude of Polish farmers towards the EU CAP, it is important to briefly outline the main features of the institutionalized representation of their interests.

Historically, during the first half of the 20th century, the peasants constituted the largest social class in Poland, supported by strong political representation through peasant parties and various organisational structures, including agricultural unions, cooperatives and chambers [15,16]. Institutionalised peasant movements mobilised this population in pursuit of economic interests and democratic values, exemplified by the so-called Great Peasant Strike of 1937. Following the Second World War, however, the communist regime’s policies systematically prevented farmers from engaging in political and protest activities independent of state control. Until the emergence of anti-communist democratic opposition, farmer resistance was consequently limited to individualised forms of passive defiance [16]. Towards the end of the 20th century, formal political and social organizations of farmers began to re-emerge. A core group of entities constituting a space for the cooperation and representation of agricultural interests emerged during this period. The political representation of farmers is traditionally associated with the Polish People’s Party (PSL), one of Poland’s oldest political groups, whose roots date back to the late 19th century. Political and socioeconomic changes over the decades have resulted in the ideological evolution of this party from agrarianism to neo-agrarianism. Consequently, the party’s electoral base is increasingly composed of rural and small-town residents, rather than farmers [17].

In recent years, important socio-professional organizations for farmers include: chambers of agriculture (professional self-government of farmers to which membership is automatic for payers of agricultural tax), farmers’ trade unions (e.g., National Union of Farmers, Circles and Agricultural Organisations—KZRKiOR and The Independent and Self-Governing Trade Union of Private Farmers ‘Solidarność RI’—NSZZ RI ‘Solidarity RI’), agricultural producer groups, and new types of organizations (Agrounia, Oszunkana wieś—Cheated Countryside) [18]. The strength, functioning, and impact of these entities on farmers’ situations are challenging to determine due to their lack of transparency and wide dispersion [19]. Agricultural trade unions and farmers’ circles are characterized by their façade, centralized nature, and legitimization by legal regulations and state subsidies. These organizations have a limited base and low membership activity, which favors the representation of the interests of a narrow group of agricultural producers [19]. The weakness of these organizations can be attributed to farmers’ low awareness of the need to organize and act together, the diversity of farmers’ interests, and the lack of strong leadership [18]. New types of organizations, such as sectoral agricultural organizations bringing together producers of specific branches of agricultural production, as well as grassroots initiatives, have emerged in response to market and political realities (Agrounia, Cheated Countryside). These new initiatives are often European in scope and operate ad hoc using social media. Their activities were particularly visible during the recent farmers’ protests in Poland (2023–2024).

3. Results

3.1. Polish Farmers and EU Membership: Conditions of Early Concerns and Scepticism (1989–2003)

Before the systemic transformation of 1989, agriculture in Poland, as in other Central and Eastern European Countries (CEEC) like Hungary, Romania or Slovakia, played a significant economic and social role despite the industrialisation process. The agricultural sector contributed substantially to GDP (accounting for 10–20% of the total) and employed a considerable share of labour resources (over 20%) [20]. Whilst the sector experienced productivity increases in certain areas (e.g., wheat, barley, milk, and live pigs), its production structures remained inefficient, governed by the principles of a state-directed economy and characterised by excessive inputs [21]. Consequently, the sector contributed to persistent food shortages and achieved lower output levels than its Western European counterparts [20,21].

The agricultural sector in communist-era Poland was distinctive in its mixed character, comprising predominantly small, private family farms [22]. Unlike other countries in the region (e.g., Czechia, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania), Poland’s collectivisation efforts failed during the 1940s and 1950s, resulting in these farms being subject to what can be termed ‘repressive tolerance’ by the communist authorities [23]. Alongside this private sector existed a state-preferred system of socialised agriculture, which during the 80s utilised approximately one-fifth of all agricultural land through various organisational forms, including state farms and agricultural production cooperatives [20].

After the collapse of the communist party and the centrally controlled economy, Polish agriculture underwent a comprehensive transformation to adapt to the rules of the free market. Even though private farms avoided collectivization during the socialist regime and operated with limited state control, during the liberal economic order of the 1990s, farmers were significantly affected by the negative consequences of structural changes (shock therapy). The state, which was established after a period of dictatorship and had an underdeveloped economy and institutions, faced various problems such as inflation, unemployment, debt, an unstable international situation, and lack of financial resources for development. This led to limited state activity, leaving many areas of life to market forces, including agriculture, where significant changes occurred. The lack of public support resulted in the collapse of unprofitable state farms, leading to poverty and unemployment for thousands of workers [24]. Additionally, the opening of the economy to international trade and a decrease in food demand placed strong competitive pressures on inefficient domestic agricultural producers and food companies [25]. This, in turn, led to debt, unfavorable price relations, and lack of funds for family farms and the agri-food industry. The result was the liquidation of many farms and a decrease in the standard of living for farming families, along with an exodus of people from rural areas [26]. During this transformation period, rural areas played a crucial role in absorbing jobless workers from the restructuring industry sector, resulting in hidden unemployment and partial repeasantisation [24,27]. The survival of small family farms during these unfavorable economic conditions can be attributed to their adaptability [28].

Facing a difficult economic reality and insufficient state intervention during the transition years, farmers organized protests to defend their interests. Two main waves of agricultural protests took place: one from 1989 to 1993 and another from 1997 to 2001. The first, still referring to the post-communist political division, was organized by the central offices of the largest trade unions—KZRKiOR, NSZZ RI ‘Solidarność’ and ZZR ‘Samoobrona’ [29]. The second wave was relatively more focused on defending the interests of certain groups of agricultural producers [16]. Grassroots social movements also emerged at that time with demands aimed at improving the situation of farmers through greater support and protection of the domestic agricultural market (minimum prices, duties on imported products, low-interest loans) [30].

The effectiveness of the initiated, spontaneous protests was low. Social tensions stemmed from the lack of adequate state action. Farmers had a feeling of abandonment (being left alone) by the state, whilst simultaneously experiencing a sense of social alienation, as a class marginalized by other groups included in the current of change set by the dominant liberal and modernisation discourse [31,32,33]. Throughout the transformation period, the share of budget expenditure on agriculture remained very low. In addition, agricultural and rural policy was implemented under conditions of a significant deficit of public funds (e.g., for interventions on agricultural markets or supporting investments in farms and food industry plants) and an insufficient level of development of public management structures. As a consequence, agriculture stagnated during this period, and only a very small group of farmers benefited from the free market changes.

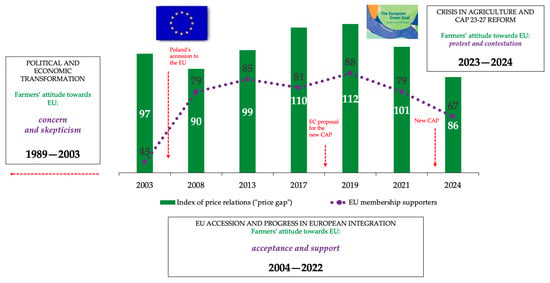

During the period of systemic transformation in Poland, the focus of economic and political reform was mainly on integrating with the EU. This integration aimed to link the national economy with the common European market, provide access to structural funds, improve public institutions by incorporating them into EU structures, and enable participation in EU policies. These efforts were met with high expectations and hopes from the political elite and wider society in Poland. However, there were also fears and distrust concerning integration with the EU. One group that particularly opposed Poland’s EU membership was farmers and rural residents, who generally held pessimistic and skeptical views about public institutions [34]. Prior to joining the EU, only 23% to 45% of farmers supported Poland’s membership in the EU, largely due to concerns about farm bankruptcies, land acquisition by foreigners, challenges in selling agricultural products, as well as increased poverty and unemployment (Figure 1) [35].

Figure 1.

Supporters of the EU membership among Polish farmers (%) and economic situation in agriculture (price scissors indicator). Index of price relations (‘price gap”) constitutes the ratio of price index of sold agricultural products to price index of purchased goods and services. Previous year = 100 [9]. EU membership supporters referred to the group of respondents who answered ‘I support’ for the question: ‘Do you personally support Poland’s membership in the European Union or are you against it?’. Other possible answers were: ‘I am against’ and ‘Difficult to say’. Source: own elaboration based on Public Opinion Research Center—CBOS data and Statistics Poland data, Statistical Yearbook of Agriculture and rural areas, 2007–2023 [6,7,8].

3.2. Political Dynamics Around the CAP After Poland’s Accession to the EU: A Period of Farmers’ Acceptance (2004–2022)

Due to the liberal transformation and reforms of the agricultural sector in Poland, as well as in other CEECs like in Hungary or Romania, agricultural structures diversified, leading to a division into large-scale commercial farms and a substantial number of small entities [36]. Over the past two decades, the inclusion of Polish agriculture in the CAP has significantly improved the economic and social situation of farmers and the entire agri-food sector. During Poland’s EU membership, despite persisting unfavorable price relations for agriculture (the relation of prices of agricultural products sold to goods and services purchased for current agricultural production and investments) and a downward trend in production profitability, farmers’ support for EU membership fluctuated between 80% and 90% for most of this period (Figure 1) [37,38].

The high level of farmers’ acceptance of the EU was mainly due to a significant increase in their income, enhanced stability of their activities, and the implementation of various agricultural and rural policy instruments aimed at modernising farms and maintaining social cohesion, such as mitigating farm liquidations. Direct payments were the most important form of support for domestic farms. From accession until 2022, they amounted to approximately PLN 240 billion (approximately EUR 57 billion). Additionally, financial support from the so-called second pillar of the CAP aimed at rural development was also significant and, according to estimates, after Poland’s accession to the EU, Polish agriculture gained the most structural funds amongst all Member States. By 2020, the value of such transfers had been set at PLN 140 billion (€33 billion) [39].

The impact of the EU CAP and the state’s post-accession agricultural policy has mainly brought economic benefits to different groups of farmers. This is evident in the marked decrease in farmers’ protest activity after 2004. Whilst protests did occur, their intensity and scale were much smaller than those observed in the 1990s and early 2000s [37]. These protests were largely sectoral, professional, and institutionalized in character, with little reference to religious and peasant slogans [30,37] Demonstrations were organized by cereal and milk producers (2008, 2012), individual farmers demanding a fairer distribution of state land, opponents of the embargo imposed on the export of agri-food products to Russia (2014), fruit and vegetable growers (2016), as well as farmers gathered in the organization Agrounia contesting the unfair practices of large retail chains (2018) [30,33].

The protests had minimal direct effects but led to increased activity in public institutions to address agricultural and rural development issues. Poland’s accession to the EU brought stability and improved agricultural and trade policies. However, it also led to the establishment of new institutional arrangements and public bodies to shape agricultural and rural policy in the sector. This included formal conditions for farm support, strategic agricultural policy design, and the creation of institutions responsible for planning, coordination, control, and financial support for the agricultural sector, with the Agency for Restructuring and Modernisation of Agriculture (ARMA) playing a crucial role. With EU accession, agricultural policy thus became a subject of planning and an element of the public policy system, which had the effect of increasing its effectiveness and efficiency, as well as its stability [39].

Whilst it improved the effectiveness, efficiency, and stability of agricultural policy, it also raised concerns about the uneven distribution of financial support, disappearance of small farms, rising agricultural land prices, environmental impact of industrial production methods, and a large group of farm users relying on subsidies for non-agricultural purposes [40,41]. In this context, however, it should be emphasized that a significant part of the CAP budget spent in Poland on social (welfare) objectives had its justifications as a factor alleviating the generalized social stress of the population associated with agriculture, resulting from dynamic structural changes in the sector [42]. Farmers’ satisfaction with EU membership and support for the CAP may have occurred due to favorable CAP interventions shaped at various levels, as well as the clear social character of EU and national agricultural policies in Poland, satisfying the expectations of the rural and small farmer electorate [42]. This balanced agricultural policy likely contributed to lower tensions and conflicts during Poland’s functioning under the CAP, possibly due to farmers’ lower interest in politics compared to the general population [43].

3.3. Crisis in Agriculture 2023–2024 and CAP Reform: Main Actors and Demands, Forms of Protests and Their Effects

A significant shift in Polish farmers’ attitudes toward the CAP and the EU occurred at the beginning of the 2020s. The causes of this change, manifested in violent and widespread protests, were complex and multifaceted, sharing commonalities with developments in other European countries while also reflecting motives specific to local circumstances [44,45].

The COVID-19 pandemic led to disruptions in global and Polish food markets, resulting in higher food prices. However, Polish farmers were not severely affected during the peak of the coronavirus crisis due to favourable weather conditions and pricing. The situation changed after Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine, causing an initial increase in food prices followed by a sharp decline in the prices of basic agricultural commodities, especially cereals. Oversupply of cereals from major exporting countries, compounded by disruptions in Polish and EU food markets, led to a significant drop in prices. The EU’s abolition of import duties and quotas in mid-2022 resulted in a surge of imports from Ukraine, causing oversupply and saturated supply chains in the EU and Poland [46]. Concerns were raised about the low quality of agricultural raw materials from Ukraine not meeting EU production standards. The lifting of import barriers on agricultural products from Ukraine created a trade displacement effect, leading to grain surpluses in CEECs, including Poland [47].

Rising food production costs and disruptions in global supply chains caused by the coronavirus pandemic, followed by shocks to global agricultural markets as a result of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, coincided with the design and implementation of the new CAP in 2023–2027. Despite no change in the primary objective, it was decided to make it more oriented towards environmental and climate objectives set in the European Green Deal (EGD) strategy (Farm to Fork Strategy, Biodiversity Strategy) [48,49]. At the same time, a new element in the management of CAP implementation (the so-called New Delivery Model) was introduced to give more responsibility in this regard to the Member States. The new policy approach was based on an analysis of the needs of the national agricultural sector, the definition of measures, and the choice of instruments within the framework of National Strategic Plans (CSPs) in order to achieve the overall objectives defined at the EU level. In each Member State, the contribution to climate goals was to be made through appropriate voluntary agricultural practices (like so-called eco-schemes, i.e., instruments that additionally reward agricultural practices that serve the environment and climate) and a set of mandatory standards (Good Agricultural and Environmental Conditions—GAEC), on which the level of subsidies to farmers was made conditional [50].

The increase in environmental and climate commitments, particularly through GAEC standards—compliance with which became a condition for receiving direct payments—resulted in heightened administrative burdens [51]. Additionally, the conversion of certain subsidies into eco-schemes linked to green agricultural practices reduced support levels for farmers who did not benefit from these new instruments. These reforms were further complicated by the need for technical and procedural adjustments within the national agricultural administration, coupled with the absence of a stable information and training policy for beneficiaries [51].

In Poland, farmers’ protests began in late 2022 and early 2023. Initially, spontaneous protests were concentrated in selected regions of the country and were directed against the increased influx of agri-food products from Ukraine (mainly cereals) (Figure 2). Whether spontaneous or coordinated by new organisations (e.g., Deceived Village), the protests mainly gathered farmers specialising in crop production who, after a good season and whilst waiting for favourable prices, held back on sales and encountered oversupply on the domestic market and a sharp fall in prices. One of the protest leaders (Deceived Village) justified the blockade of the Polish-Ukrainian border crossing as follows [52]:

Figure 2.

Farmers’ protest in Lubelskie region near crossing border with Ukraine, June 2023. The slogans on the placards proclaim inter alia: ‘We help Ukrainians, not oligarchs, ‘No for industrial wheat’, ‘Do you really know what you’re eating?’, Prime Minister, minister—the truth will set you free’.

This is a protest by young farmers aged 35–40 who have a future ahead of them and are building our countryside. We won’t be able to compete with industrial Ukrainian agriculture. The European Union imposes technological requirements on us, and we have to produce to high standards. Yet we suddenly face prices 30% lower than in Europe and the complete liberalization of Ukrainian crops.

Spontaneous speeches in the form of pressure on policymakers gradually turned into more radical actions: road blockades in major cities, blockades of border crossings. Traditional organizations representing farmers’ interests also joined the protests. Farmers’ discontent in other countries also intensified, targeting the reformed CAP aimed at the implementation of the EGD and growing bureaucracy, and calling for greater protection of the EU internal market [50]. The demands against the CAP and the European Green Deal were also widely taken up by Polish farmers. The chairman of the NSZZ RI ‘Solidarity’ justified his opposition to the EU as follows [53]:

We must build solidarity among European farmers (…) and oppose all the threats coming from Brussels. We, as Poles, are collecting signatures for a referendum against the Green Deal to say a firm no, to say an end to this dictate and this green communism that has reached us. (…) We fought against the red communism that was here, and now we must fight against this green communism that is reaching us, which is destroying our farms, family farms, and multi-generational farms. We must say a firm no! European farmers together!

This reflected their waning support for Poland’s EU membership and the CAP. In 2024, 67% of farmers were in favour of membership and 26% were against, whilst as recently as 2021 the respective percentages were 79% and 15% [Figure 1]. By the time the protests intensified (2023), farmers’ political views had clearly evolved from a centrist self-identification to a right-wing one [43]. At the same time, it is worth noting that the farmers’ protests against the last CAP reform enjoyed particularly positive public support [54]. The level of support for Poland’s EU membership among farmers recorded in 2024 was the lowest since the year preceding accession. However, the protests against the new CAP were fundamentally rooted in the significant and long-term deterioration in market conditions and profitability in agriculture [55]. The decline in the sector’s price ratio in 2024 was relatively the highest (Figure 1).

If we consider the theoretical framework for collective action by a group of farmers, the genesis of the protests was political (opposition to the reformed CAP), economic (opposition to opening the EU market to agricultural products from third countries and deteriorating production profitability), and socio-cultural (a sense of political isolation, pressure from other social groups, and limited autonomy) [14]. The protests were driven by relatively young farmers focused on developing conventional agricultural production, particularly those specializing in arable farming [52].

Structurally, the 2023–2024 protests were unprecedented owing to their grassroots and dispersed mobilization, utilizing social media and bringing together a large proportion of farmers previously uninvolved in social or trade union activity. This may indicate the political activation of previously inactive agricultural producers in defense of their interests. Finally, the unprecedented dimension of the farmers’ protests concerned their social function and the outcomes achieved [14]. At both the EU and Polish levels, a significant portion of the protesters’ demands were met (especially short-term demands). Simultaneously, a notable effect of the protests was drawing other social groups’ attention to agricultural problems in Poland and gaining broader public support, at least in the short term, for the demands put forward [54].

Farmers’ strikes and disruptions in global agricultural markets negatively affecting farmers in Europe led to CAP changes accepted at the EU level and to national government intervention. Changes to the CAP 2023–2027 called as Simplification Package implemented in 2024 regarding mandatory environmental practices were introduced (abolition of fallowing of 4% of agricultural land—GAEC 8, introduction of a choice between diversification and rotation—GAEC 7, simplified soil cover maintenance standard—GAEC 6; exemption of small farms from conditionality controls and penalties related to the GAEC and SMR standards) [51]. Monitoring of imports of agri-food products from Ukraine into the EU has been introduced. If imports exceed certain threshold volumes, then the European Commission is obliged to introduce safeguard mechanisms (for e.g., sheep, sugar, eggs, poultry meat, maize) in the form of tariffs [56]. In July 2024, a regulation of the Council of the EU increasing tariffs on Russian and Belarusian cereals, oilseeds, and related products came into force. Prior to this, the Polish government granted financial compensation to farmers, mainly grain producers, and increased liquidity loan action negotiated with representatives of farmers’ organisations during the peak of the protests in March 2024 [57].

4. Discussion

The attitudes of Polish farmers towards agricultural policy, including the CAP, vary for several reasons. One of these reasons is the influence of the post-socialist heritage, which has shaped their specific ways of thinking and attitudes [58]. Regardless of historical, political, and economic differences and similarities, the dynamics surrounding farmers’ attitudes toward EU membership and the CAP in Poland illustrated in this article display certain commonalities with those observed in CEEC, for instance in Hungary or Romania. In the region, the trajectory of unstable attitudes toward the EU may have deep roots related to several institutional and political processes. Firstly, despite the benefits of financial, organisational, and technical support from the EU, sufficiently strong relationships based on cooperation, recognition, and trust have not developed between the siloed, relatively weak, and unstable post-transformation structures of public institutions and the dispersed farmers’ organisations on the social side [59,60].

Secondly, the technocratic implementation of agricultural policy and development strategies—largely based on an external EU model characteristic of Western European economic structures—has often been met with misunderstanding and has provoked resistance. This has been especially true in the long term, despite the Europeanisation of public governance structures and the achievement of tangible benefits for farmers (e.g., increased income through direct payments) and rural residents (implementation of infrastructure and social investments co-financed by EU funds). Contributing factors include the declining profitability of agricultural production, a growing sense of economic insecurity, and deepening class divisions vis-à-vis other socio-professional categories and urban residents [61]. In the CEEC countries, fertile ground has emerged for tendencies to replace conflict over economic issues with disputes over sovereignty, migrants, minorities, and an allegedly immoral EU threatening national identity and sovereignty—tendencies skilfully exploited by illiberal right-wing and far-right parties [60,61,62,63].

Thirdly, the Europeanisation of agricultural and rural structures and policies in Poland and the CEEC countries, imposed on post-socialist and post-transformation social institutions and mechanisms, has been accompanied to a certain extent by the emergence and consolidation of opportunistic and rent-seeking behaviour amongst agricultural and rural interest groups having considerable political power [64]. Consequently, political reforms involving the reorganisation of public support (to serve the interests of food consumers) or its reorientation towards alternative goals (e.g., the environmental and climate-related objectives of the European Green Deal) have been met with opposition.

Additionally, the evolving objectives of the EU’s CAP, with a greater emphasis on climate and environmental issues, have made support conditional on farmers’ compliance with various requirements related to reducing greenhouse gas emissions and pesticide use. This has led to opposition from both large-scale and smaller producers, with some expressing regressive populism [55]. Despite receiving support, farmers have shown skepticism and opposition to EU membership, likely due to their strong national self-identification, which has prevented them from seeing themselves as Europeans. Many farmers perceived EU actions as a limitation of national sovereignty, and they feel that the national government has insufficient influence on decisions made in Brussels [43]. Additionally, a right-wing political orientation and strong connection to religious values, particularly membership in the Catholic Church, are characteristic of many Polish farmers.

It is noteworthy that despite significant financial transfers, there is a relatively large group of farmers who are critical of the CAP’s functioning. This ‘paradoxical dissatisfaction’ has been attributed to reasons such as lack of protection of local producers from market shocks and foreign competition, malpractices by international retail food chains, unfair subsidization of inactive farms, and lack of equal treatment compared to farmers from other EU Member States [40]. Moreover, the unfavorable portrayal of protesting farm organizations and farmers by the media has contributed to low mobilization during Poland’s EU membership, often depicting them as populist and extreme right-wing [40]. Interestingly, criticism of agricultural policy was also expressed by the cooperative farm sector, which constitutes a significant minority in Polish agriculture (in 2018 there were 578 such entities managing 190,000 hectares of agricultural land). This disapproval targeted national authorities, with cooperative farmers arguing that government policies systematically favored family farms over their operations, both in the distribution of CAP funds and in agricultural legislation [65].

When analyzing the nature of farmers’ collective action, its structural dimension is important [14]. The grassroots, decentralized farmers’ protests in Poland 2023–2024 were organized to a large extent with the use of social media and sites occurred on a significant scale across the country. As for the genetic dimension of collective action, these protests, characterized by their opposition to both the unrestricted inflow of agricultural products from Ukraine and the assumptions of the new CAP, demonstrated considerable effectiveness in achieving their stated demands [14,43,51,56]. Paradoxically, despite their organizational dispersion or avoiding traditional unions and organizations, this bottom-up mobilization enabled them to reclaim their political voice retained by this declining socio-professional group (functional aspect of collective action) [66].

This study aimed to explore the changes in attitudes of Polish farmers towards the EU CAP over different time periods: during the preparation for European integration, whilst operating under the CAP, and during the recent crisis in European agriculture [44,45]. Three main types of farmers’ attitudes were identified: skepticism and concern, followed by acceptance and support, and eventually criticism and opposition. This reflects a certain ambivalence and ambiguity in attitudes towards the EU and the CAP, also demonstrated in narrative research on Polish farmers [67]. Membership in the EU and the CAP provided Polish farmers with new opportunities for farming and to advocate for their interests in public policy. European integration has led to significant modernisation and economic strengthening of many farms, bringing stability to agricultural businesses and enhancing rural development programmes and strategies. Initial concerns about the EU CAP gave way to widespread acceptance and support but changed again due to a crisis in European agriculture attributed to disruptions in global agricultural markets and the new CAP focusing on climate and environmental objectives. From 2023 onwards, Polish farmers actively protested against EU institutions and the reformed CAP as a result. The shift in farmers’ attitudes toward EU membership, reflected in increased opposition, was significantly influenced by market conditions. In 2024, a marked deterioration in the profitability of agricultural activities, coupled with uncertainty about the terms of support and relative reductions in funding levels, generated widespread discontent among the farming community [3,56].

As a consequence of the progressive development of agriculture and general economic changes over the last decades of transition and Poland’s integration with the EU, the processes of disappearance of peasant and family farms and the transformation of the latter into highly commercial farms, functioning like business entities, have been reinforced. In the aforementioned group, which is relatively small in number, an approach to the farm as a business venture based on cost and profit accounting has developed, and the cultural and social orientation inherent in family farming is disappearing [68]. However, the development of these farms, within the agri-food system shaped by the CAP as it has functioned thus far, is increasingly encountering barriers. One stems from the growing globalization and competition of markets. Another relates to increasing conditions of public support dependent on meeting environmental and climatic objectives. The agricultural development model based on low production costs and intensive subsidies is being challenged. Therefore, the need for a thorough reform of the EU CAP has been raised more and more often, also by Polish farmers.

5. Conclusions

The paper demonstrates that Polish farmers’ attitudes toward the CAP have evolved from skepticism and fear during the pre-accession period to broad support following integration, and most recently to renewed criticism amid economic and environmental reforms. EU membership and CAP instruments substantially improved farm incomes, modernized agricultural structures, and stabilized the agri-food sector, contributing to Poland’s agricultural economy transformation and development. However, the persistence of structural dualism and the growing marginalization of family farms indicate that economic impacts and benefits have been perceived as unevenly distributed. Over the years, a division has been established among agricultural farms in Poland: the majority are small, multifunctional units, often unable to cope with competition and subsequently withdrawing from the market, while a minority consists of commercial, developing farms that are consolidating land and capital resources.

Recent farmers’ discontent and protests reflect tensions between traditional production-oriented expectations and demands and the new policy paradigm prioritizing sustainability and climate objectives. Farmers’ growing opposition also stems from excessive bureaucracy, regulatory disparity leading to unequal competition with non-EU agricultural producers (e.g., cereals, soft fruits), insufficient national influence within EU decision-making, which is associated with the perception of social and political pressure and the narrowing of the field of decision-making autonomy regarding production processes on the farm. Nonetheless, CAP support remains a key pillar of Poland’s agricultural stability, even as its legitimacy is increasingly contested. These dynamics highlight the need for policy adjustments that reconcile environmental goals with economic viability and maintain social cohesion in rural areas.

The question remains open regarding the development of farmers’ political influence on the shape of the CAP post-2027. Grassroots, democratic mobilization using social media, largely bypassing traditional organizations representing agricultural interests, has proven effective in implementing immediate demands (e.g., additional financial support, easing pro-environmental and pro-climate CAP regulations, and limiting the inflow of agricultural products from Ukraine). However, the causes of the deteriorating situation of small and medium-sized farmers are far deeper and stem from global economic processes (the weakening position of agricultural producers in the food chain relative to other actors, and structural changes in the global economy), market processes (price volatility and cyclicality, concentration of production resources and output, and growing competition in international trade), and environmental and climate processes (global warming, water shortages, soil degradation, and diminishing fossil fuel resources). These problems facing farmers in Poland and other European countries constitute a challenge for shaping a more inclusive, efficient, and fair agricultural policy, the assumptions of which should be developed through dialogue and extensive training and information activities. Therefore, early, comprehensible, and inclusive communication about the CAP by EU and national policymakers with farmers in various forms (such as deliberative panels, meetings, and training sessions) will be crucial.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in Statistics Poland at https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/agriculture-forestry/ (accessed on 6 April 2025) and the Public Opinion Research Center at https://www.cbos.pl/EN/home/home.php (accessed on 30 April 2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Poczta-Wajda, A. Polityka Wspierania Rolnictwa a Problem Deprywacji Dochodowej Rolników w Krajach o Różnym Poziomie Rozwoju; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sheingate, A. The Rise of the Agricultural Welfare State; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA; Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dudek, M. Changes in Polish Agriculture from 2004 to 2022 in the Light of Economic Conditions and European Union Membership. Probl. Agric. Econ. 2025, 384, 21–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Political Economy of Institutions and Decisions; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Milczarek-Andrzejewska, D.; Śpiewak, R. Farmers’ associations: Their resources and channels of influence. Evidence from Poland. Sociol. Rural. 2018, 58, 825–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBOS. Dwadzieścia Lat Członkostwa Polski w Unii Europejskiej [Twenty Years of Poland’s Membership in the EU]; Report No. 43/2024; CBOS: Warsaw, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- CBOS. Polska w Unii Europejskiej [Poland in the European Union]; Report No. 139/2021; CBOS: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- CBOS. Ocena Skutków Przystąpienia Polski Do UE po Trzech Latach Członkostwa [Assessment of the Effects of Poland’s Accession to the EU After Three Years of Membership]; CBOS: Warsaw, Poland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Poland. Statistical Yearbook of Agriculture; Statistics Poland: Warsaw, Poland, 2024.

- Ćwiklicki, M. Metodyka Przeglądu Zakresu Literatury (Scoping Review); Munich Personal RePEc Archive 2022; Paper No. 104370; University Library LMU Munich: Munich, Germany, 2020; Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/104370/ (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquhoun, H.L.; Levac, D.; O’Brien, K.K.; Straus, S.; Tricco, A.C.; Perrier, L.; Moher, D. Scoping Reviews: Time for Clarity in Definition, Methods, and Reporting. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 1291–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadie, S.N.H. ABC of a scoping review: A simplified JBI scoping review guideline. Educ. Med. J. 2024, 16, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorlach, K. Socjologia Obszarów Wiejskich: Problemy i Perspektywy; Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar: Warszawa, Poland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Molenda, J. Chłopi naród niepodległość. In Kształtowanie Się Postaw Narodowych i Obywatelskich Chłopów w Galicji i Królestwie Polskim w Przededniu Odrodzenia Polski [Peasants, Nation, Independence: The Development of National and Civic Attitudes Among Peasants in Galicia and the Kingdom of Poland on the Eve of Poland’s Rebirth]; Instytut Historii PAN: Warszawa, Poland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gorlach, K.; Foryś, G. Ruchy społeczne jako instrument walki o sprawiedliwość społeczną [Social movements as an instrument to fight for a social justice: Some considerations based on protests developed (not only) by Polish farmers]. Wieś i Rol. 2023, 1, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szustakiewicz, P. Ideologia Polskiego Stronnictwa Ludowego na początku XXI wieku [The ideology of the Polish Peasant Party at the beginning of the twenty-first century]. Stud. Politol. 2010, 18, 221–241. [Google Scholar]

- Milczarek-Andrzejewska, D. Zagadnienie Siły w Ekonomii—Na Przykładzie Sektora Rolno-Spożywczego w Polsce [Power in Economics: The Case of the Agri-Food Sector in Poland]; IRWiR PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Halamska, M. Organizacje rolników: Bilans niesentymentalny. In Wiejskie Organizacje Pozarządowe; Halamska, M., Ed.; IRWiR PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Poczta, W. Przemiany w rolnictwie polskim w okresie transformacji ustrojowej i akcesji Polski do UE [Changes in Polish agriculture in the period of political transformation and accession of Poland to the EU]. Wieś i Rol. 2020, 187, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorzelak, E. Polskie rolnictwo w XX wieku. In Produkcja i Ludność [Polish Agriculture in XXth Century. Output and Population]; Prace i Materiały 84; Instytut Rozwoju Gospodarczego Szkoły Głównej Handlowej: Warszawa, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gorlach, K.; Seręga, Z. Rodzinna własność rolna w procesie transformacji ustrojowej [Family farm ownership in the process of political transformation]. Stud. Socjol. 1991, 3–4, 93–105. [Google Scholar]

- Gorlach, K. On repressive tolerance: State and peasant farm in Poland. Sociol. Rural. 1989, 29, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halamska, M. Dekolektywizacja Rolnictwa w Europie Środkowej i jej Społeczne Konsekwencje [Decollectivization of Agriculture in Central Europe and Its Social Consequences]; IRWiR PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hunek, T. Convergence of Agriculture in the Market-Oriented Economy. Changes in land use, employment in agriculture and agricultural policy instruments. In Problems of Village and Agriculture During Market Reorientation of the Economy; Rosner, A., Ed.; IRWiR PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 2004; pp. 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel, I. Selected Problems of the Rural Labour Market in Poland. In Rural Development in the Enlarged European Union; Zawalińska, K., Ed.; IRWiR PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 2005; pp. 165–185. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkin, J. Przekształcenia sektora państwowych gospodarstw rolnych w Polsce w opinii władz lokalnych i mieszkańców „osiedli pegeerowskich”. In Ludzie i Ziemia po Upadku Pegeerów; SGGW: Warsaw, Poland, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Czyżewski, A. Kwestia agrarna we współczesnej ekonomii—problemy i wyzwania [The Agrarian Question in Contemporary Economics—Problems and Challenges]. In Kwestia Agrarna. Zagadnienia Prawne i Ekonomiczne; Litwiniuk, P., Ed.; Wydział Nauk Ekonomicznych SGGW; Fundacja FAPA: Warsaw, Poland, 2016; pp. 441–460. [Google Scholar]

- Foryś, G. Dynamika sporu. In Protesty Rolników w III Rzeczypospolitej [The Dynamics of Dispute: Farmers’ Protests in the Third Republic of Poland]; Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar: Warsaw, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gorlach, K.; Foryś, G. Mobilizacja polityczna poza metropolią: Aktywność protestacyjna rolników polskich [Political Mobilization beyond the Metropolis: Protest Activity of Polish Farmers]. In W Metropolii i Poza Metropolią: Społeczny Potencjał Odrodzenia i Rozwoju Społeczności Lokalnych. Księga Jubileuszowa Profesora Pawła Starosty; Michalska-Żyła, A., Zajda, K., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego: Łódź, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkin, J. Postrzeganie przez ludność wiejską roli państwa w transformacji polskiego rolnictwa [The rural population’s perception of the role of the state in the transformation of Polish agriculture]. In Chłop, Rolnik Czy Farmer? [Peasant, Farmer or Agricultural Entrepreneur?]; Instytut Spraw Publicznych: Warsaw, Poland, 2000; pp. 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Czapiński, J.; Panek, T. Diagnoza społeczna 2003. In Warunki i Jakość Życia Polaków [Social Diagnosis 2003. Quality of Life in Poland]; Wyższa Szkoła Finansów i Zarządzania: Warsaw, Poland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bilewicz, A.M. Beyond the Modernisation Paradigm: Elements of a Food Sovereignty Discourse in Farmer Protest Movements and Alternative Food Networks in Poland. Sociol. Rural. 2020, 60, 754–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedyszak-Radziejowska, B.; Frenkel, I.; Klepacka, D.; Liro, A.; Milczarek, D.; Poczta, W.; Tabor, S.; Żukowski, T.; Budzisz-Szukała, U.; Jasiński, J. Polska Wieś po Wejściu do Unii Europejskiej [Polish Countryside After Accession to the European Union]; Fundacja na Rzecz Rozwoju Polskiego Rolnictwa: Warsaw, Poland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Poczta, W. Największe korzyści z akcesji Polski do UE w sektorze rolno-żywnościowym [The greatest benefits of Poland’s accession to the EU in the agri-food sector]. In Gdzie Naprawdę są Konfitury? [Juicy opportunities—where they really are?]; Orłowski, W.M., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego: Warsaw, Poland, 2021; pp. 136–151. [Google Scholar]

- Csaki, C.; Forgacs, C.; Milczarek-Andrzejewska, D.; Wilkin, J. (Eds.) Restructuring Market Relations in Food and Agriculture of Central and Eastern Europe: Impacts upon Small Farmers; Agroinform Publisher Co. Ltd.: Budapest, Hungary, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Foryś, G. Kulturowe aspekty aktywności protestacyjnej rolników w Polsce [Cultural Aspects of Farmers’ Protest Activity in Poland]. Stud. Socjol. 2016, 1, 19–43. [Google Scholar]

- Nurzyńska, I.; Drygas, M.; Dudek, M.; Wieliczko, B. Ocena WPR w Polsce—Intensyfikacja Innowacyjności Warunkiem Koniecznym Przetrwania Polskiego Rolnictwa [Assessment of the CAP in Poland—Intensification of Innovation Is a Necessary Condition for the Survival of Polish Agriculture]; EFRWP; IRWiR PAN: Warszawa, Poland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkin, J. Bilans 10 lat członkostwa Polski w Unii Europejskiej dla rolnictwa i obszarów wiejskich [The balance of 10 years of Poland’s membership in the European Union for agriculture and rural areas]. In Polska Wieś 2014. Raport o Stanie wsi; Nurzyńska, I., Poczta, W., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar; FDPA: Warsaw, Poland, 2014; pp. 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bilewicz, A.; Mamonova, N.; Burdyka, K. “Paradoxical” Dissatisfaction among Post-Socialist Farmers with the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy: A Study of Farmers’ Subjectivities in Rural Poland. East Eur. Politics Soc. 2022, 36, 892–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilewicz, A.; Bukraba-Rylska, I. Deagrarianization in the Making: The Decline of Family Farming in Central Poland, Its Roots and Social Consequences. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 88, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, O.; Fałkowski, J. On structural change, the social stress of a farming population, and the political economy of farm support. Econ. Transit. Institutional Change 2019, 27, 201–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBOS. Mieszkańcy wsi i polityka [Rural Population and Politics]; Report No. 5/2024; CBOS: Warsaw, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mc Loughlin, E. Protesting the future: The evolution of the European farmer. Anthropol. Today 2024, 40, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, A. Farmer protests and the 2024 European Parliament elections. Intereconomics 2024, 59, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bułkowska, M.; Bazhenova, H. Direct and indirect consequences of the war in Ukraine for Polish trade in agri-food products. Probl. Agric. Econ. 2023, 376, 66–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamulczuk, M.; Cherevyk, D.; Makarchuk, O.; Kuts, T.; Voliak, L. Integration of Ukrainian grain markets with foreign markets during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Probl. Agric. Econ. 2023, 377, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Factsheet—A Greener and Fairer CAP; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2023; Available online: https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/document/download/89b607ec-8a43-4073-bafd-f2493da7699e_en (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- European Commission. Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council: Summary of CAP Strategic Plans for 2023–2027—Joint Effort and Collective Ambition; COM (2023) 707 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Czubak, W.; Kalinowski, S.; Pelpliński, B. Ziarno Niezgody: Analiza Protestów Rolniczych [Grain of Discord: Analysis of Farmers’ Protests]; Instytut Finansów Publicznych: Warsaw, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Study on Simplification and Administrative Burden for Farmers and Other Beneficiaries Under the CAP; EU CAP Network Report; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2025; Available online: https://eu-cap-network.ec.europa.eu/publications/study-simplification-and-administrative-burden-farmers-and-other-beneficiaries-under_en (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Chlebosz, M.; Drugi Dzień Blokad na Granicy Polsko-Ukraińskiej. Jak Minęła Noc? Farmer.pl, 3 February 2023. Available online: https://www.farmer.pl/fakty/drugi-dzien-blokad-na-granicy-polsko-ukrainskiej-jak-minela-noc,127978.html (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Katana, A. Protest w Brukseli—rolnicy żądają zmian w Unii Europejskiej. WRP.pl. 6 June 2024. Available online: https://www.wrp.pl/protest-w-brukseli-rolnicy-zadaja-zmian-w-unii-europejskiej/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- CBOS. Co Polacy Sądzą o Protestach Rolników [What Do Poles Think of Farmers’ Protests]; Report No. 11/2024; CBOS: Warsaw, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Ploeg, J.D. Farmers’ Upheaval, Climate Crisis and Populism. J. Peasant. Stud. 2020, 47, 589–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, A.; Pawłowska, A.; Dudek, M. Eco-Scheme—Carbon Farming and Nutrient Management—A New Tool to Support Sustainable Agriculture in Poland. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzgodnienia w Jasionce [Agreements in Jasionka]. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/rolnictwo/uzgodnienia-w-jasionce (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Swain, N. Agriculture ‘East of the Elbe’ and the Common Agricultural Policy. Sociol. Rural. 2013, 53, 369–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruszt, L.; Langbein, J. Strategies of regulatory integration via development: The integration of the Polish and Romanian dairy industries into the EU single market. In Levelling the Playing Field: Transnational Regulatory Integration and Development; Bruszt, L., Mcdermott, G.A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 58–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzogány, A.; Varga, M. Breaking the rural underdevelopment trap? Eastern Enlargement, agricultural policy and lessons for Ukraine. J. Eur. Public Policy 2025, 32, 2914–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żuk, P. The European Green Deal and the peasant cause: Class frustration, cultural backlash and right-wing nationalist populism in farmers’ protests in Poland. J. Rural. Stud. 2025, 119, 103708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ost, D. Stuck in the past and the future: Class analysis in post-communist Poland. East Eur. Polit. Soc. 2015, 29, 610–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujdei-Tebeica, V. Green Policies, Gray Areas. Civ. Szle. 2024, 21, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fałkowski, J. Together we stand, divided we fall? Smallholders’ access to political power and their place in Poland’s agricultural system. J. Agrar. Change 2018, 18, 893–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamski, M. Determinanty Funkcjonowania Spółdzielczych Gospodarstw Rolnych w Polsce; Studia i Monografie 205; IERiGŻ PIB: Warszwa, Poland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Milczarek-Andrzejewska, D.; Widła-Domaradzki, Ł. Co wpływa na postrzeganą siłę organizacji rolniczych? Wnioski na podstawie opinii członków organizacji. Wieś i Rol. 2025, 2, 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radowska-Lisak, M.; Kowalska, M. Nothing Changed, Nothing Gained? Emotional Responses towards European Integration in the Memoirs of Polish Farmers. Cult. Sociol. 2024, 18, 280–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorlach, K.; Starosta, P. Rodzinne gospodarstwa rolne w społecznościach wiejskich: Zmiany organizacji życia społecznego wsi w świecie nowoczesnym i ponowoczesnym. Rocz. Nauk. Społecznych 2018, 10, 17–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).