Abstract

Conventional tourism planning in ecologically fragile regions often adopts a reductionist perspective, failing to address the synergistic spatial interactions between ecological conservation, resource utilization, and infrastructure. To bridge this gap, this study develops a multi-constraint synergistic assessment framework for the dry-hot valley of Lujiang Dam (LJD) in China. Grounded in the understanding of rural tourism as a complex adaptive system, the framework innovatively integrates the InVEST model, kernel density estimation, and cumulative cost-distance algorithms to identify Natural Spatial Suitability for Tourism Development (NSSTD). Key findings include (1) pronounced spatial heterogeneity in habitat quality, with high-quality zones in the west/southeast requiring strict conservation; (2) a “barbell-shaped” clustering of natural/cultural resources at the valley’s northern and southern extremities, highly congruent with ethnic settlements; and (3) a “concentric layered” accessibility pattern where 88.08% of resources are within a 90 min drive. Crucially, the spatial overlay analysis revealed that NSSTD (54.74 km2) emerges not from single high-value zones but from areas of synergy, such as those with medium habitat quality coupled with high resource endowment and accessibility. These results provide a scientifically robust, spatially explicit layer for China’s “Multi-plan Integration” territorial spatial planning. They enable differentiated strategies—channeling development to southern corridors, implementing niche tourism in northern “structural hole” villages, and enforcing conservation in western habitats—thereby offering a replicable methodology to balance ecological integrity with sustainable rural development.

1. Introduction

As a critical driver of regional socioeconomic development, tourism serves as a vital catalyst for urban–rural economic growth and cross-cultural exchange, generating substantial income, employment opportunities, and wealth accumulation [1,2]. Governments worldwide have prioritized tourism development through policy interventions to maximize its socioeconomic benefits, particularly in economically disadvantaged rural regions. Nevertheless, the unregulated expansion of rural tourism has precipitated significant environmental and cultural crises [3,4]. These challenges are particularly acute in mountainous ethnic regions, where fragile ecosystems and intangible cultural heritage are highly vulnerable to disruptive development models. The single-minded pursuit of economic gain jeopardizes ecological security through multiple pathways [5], such as overexploitation of land resources [6], degradation of habitat quality and biodiversity [7,8], and irreversible damage to cultural landscape heritage [9], posing a severe threat to the sustainable development of tourism of mountainous communities and their cultural identity. These impacts not only undermine tourism experiences but also contravene conservation objectives, ultimately diminishing regional sustainable development capacity. To reconcile the contradictions faced by mountainous regions that are ecologically fragile yet rich in cultural resources, this study advocates for a multi-constraint synergistic framework grounded in environmental and cultural preservation. By systematically investigating the spatial allocation mechanisms of tourism resources, our approach aims to inform evidence-based strategies for sustainable rural tourism planning.

Rural habitat quality and its spatial configuration constitute the ecological substrate of tourism attractiveness, fundamentally determining the sustainability of rural tourism development. As tourism intrinsically depends on habitat integrity, ecological resources emerge as both core experiential elements and primary attractions [10]. Effective ecosystem conservation is therefore imperative for securing sustained ecological dividends and maintaining tourism competitiveness. Habitat quality, defined as the capacity of ecosystems to provide viable conditions for species survival and reproduction [11], serves as a critical metric for biodiversity conservation [12]. This parameter engages in a dynamic equilibrium with tourism development. Graded habitat landscapes enhance destination appeal and facilitate spatial expansion of tourism activities [13], while intensive recreational utilization threatens habitat carrying capacity through landscape fragmentation [14]. Such tensions predominantly stem from unregulated tourist influxes and inadequate management protocols, which amplify nonlinear risks to fragile habitats through threshold effects [15]. Consequently, scientifically rigorous assessment of habitat quality is the first fundamental constraint for sustainable tourism planning. In this context, the InVEST model has gained recognition as an effective tool for spatially explicit habitat quality evaluation [16]. It has been well-established in applications such as lake ecosystems [17], watershed environments [18], and protected areas [19]. Its capacity to identify critical landscape elements and map habitat quality distributions provides a critical scientific basis for guiding the spatial allocation of tourism resources [20], thereby supporting sustainable tourism development through informed landscape management. These precedents provide a methodological foundation for its parameterization within the unique dry-hot valley context of this study, ensuring that the assessment of habitat quality as a constraint is both scientifically robust and contextually appropriate. However, while tools like InVEST excel in quantifying ecological conditions, a critical gap persists in systemically linking these habitat assessments with broader development decisions. Specifically, there is a lack of frameworks that effectively integrate this ecological constraint with other critical dimensions, such as resource endowment and facility accessibility, to identify tourism-compatible spaces. This disconnect underscores the necessity for a multidimensional approach that can simultaneously decipher ecological supply spaces and heterogeneous resource patterns.

Rural natural and cultural landscape resources are not only the core assets but also the spatial foundation of rural tourism economies. Their distribution patterns fundamentally shape development potential, making comprehensive insights into these patterns, alongside infrastructure conditions, essential for effective planning. The reliable inventory of these resources builds upon field investigations and community engagement [21]. Critically, advanced spatial analytics integrating remote sensing (RS) and geographic information systems (GIS) enable the precision mapping of their distribution, with kernel density estimation being particularly effective for identifying agglomeration patterns [22]. However, the spatial disparity and fragility of these resources pose a central challenge. Overexploitation and inappropriate development not only lead to resource depletion [23] but also degrade the very qualities that constitute the tourism appeal, thereby undermining sustainability. This highlights that the spatial distribution and carrying capacity of resource endowment form the second critical constraint for sustainable tourism. Therefore, moving beyond a mere inventory of resources to a precise assessment of their spatial agglomeration and vulnerability is paramount. This establishes “resource endowment” as a key constraint whose configuration must be synergistically evaluated with other spatial factors, such as habitat quality and infrastructure, to identify viable development zones.

The pressure systems influencing rural tourism development rarely manifest in isolation, with transport infrastructure expansion emerging as a predominant stressor alongside habitat quality and resource endowment constraints [24], thereby constituting a third critical constraint characterized by its dual role as both an enabler and a stressor. A robust bidirectional relationship exists between tourism growth and transport networks [25], as infrastructure development enhances regional accessibility [26] and fosters tourism-economic connectivity [27], while reciprocally, tourism prosperity stimulates peripheral infrastructure upgrades [28]. Yet, this development often comes at a significant ecological cost [29], particularly from road construction, which degrades habitat integrity through landscape fragmentation [30]. Spatial accessibility evaluation frameworks are recognized as pivotal tools for optimizing infrastructure equity and configuration [31], employing methodologies spanning buffer analysis, gravity modeling, cost-distance algorithms, and network analytics to inform destination management [32,33,34,35]. However, conventional approaches often treat accessibility in isolation, failing to capture its interdependencies with ecological and resource systems [36]. This isolation underscores why facility accessibility must be formally integrated as the third indispensable constraint within a multi-constraint synergistic framework, to simultaneously optimize connectivity, conserve habitats, and ensure community equity.

Despite significant advancements in existing research, three critical limitations persist, constraining the effectiveness of sustainable tourism planning in ecologically fragile regions: First, a reductionist perspective, where most studies focus in isolation on single subsystems such as habitat quality, resource development, or infrastructure, lacking multi-dimensional integrated analysis. Second, the decoupling of spatial configuration mechanisms, wherein the spatial correlation mechanisms between ecological conservation, facility networks, and tourism resource distribution—particularly the systematic identification of NSSTD through spatial overlay techniques—remain underexplored. Third, insufficient comprehensive analysis of multi-dimensional synergistic effects, failing to effectively reveal the synergies and conflicts between habitat quality, resource endowment, and facility accessibility, which consequently undermines the implementability of proposed development strategies. In ecologically fragile areas like dry-hot valleys, environmental sensitivity, resource fragmentation, and infrastructural deficiencies intertwine, causing these theoretical gaps to manifest as acute conservation-development conflicts in practice.

To bridge these gaps, this study establishes a multi-constraint assessment framework integrating the InVEST habitat model, kernel density estimation, and the cumulative cost distance algorithm. It aims to systematically address the following three research questions: (RQ1) What are the spatial heterogeneity characteristics of the three constraint subsystems—habitat quality, tourism resource endowment, and facility accessibility—within the ecologically fragile context of the Nujiang dry-hot valley? (RQ2) What spatial synergies and conflicts exist among these three subsystems, and through what mechanisms do they collectively shape the NSSTD? (RQ3) Based on the identification results of NSSTD, how can differentiated spatial planning and territorial spatial governance strategies be formulated to promote sustainable rural tourism in dry-hot valleys and similar fragile environments? Using the largest dry-hot valley LJD in the mid-reaches of the Nujiang River Basin as an empirical case study, this research seeks to decipher the spatial configuration patterns of the ecology—resource—infrastructure system in fragile environments. By answering the above questions, it aims to validate the effectiveness of the multi-constraint synergy framework in identifying potential development zones, ultimately providing a scientific basis and actionable pathways for planning practices that reconcile ecological conservation with rural development.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

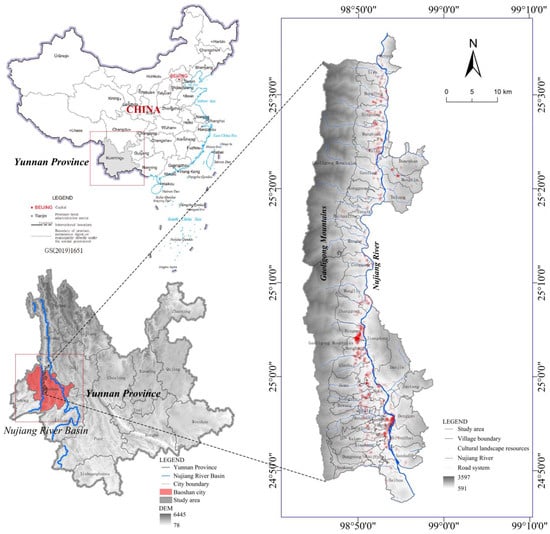

The Nu River-Salween, an international river traversing China and Myanmar, originates from the Tibetan Plateau and discharges into the Andaman Sea. Within this transboundary basin, the dry-hot valley of LJD constitutes the largest such geomorphological unit in the mid-reaches of the Nu River Basin (Figure 1). Bordered by the Gaoligong Mountains to the west and the Nu Mountains to the east, this 1308.88 km2 valley features parallel north–south mountain ranges and river systems, administratively encompassing Lujiang Town and Mangkuan Yi-Dai Ethnic Township with jurisdiction over 41 villages. Renowned for its ecological complexity and ethnic diversity, the area sustains unique vertical gradient microclimates and preserves the cultural heritage of Nu, Lisu, and Dai ethnic communities [37]. China’s rural revitalization initiatives, particularly Yunnan Province’s “Greater Western Yunnan Tourism Loop” development strategy, have catalyzed unprecedented tourism growth while intensifying pressures on fragile ecosystems and cultural landscapes [38]. Current research on heritage site threats predominantly addresses either environmental or anthropogenic factors [39], yet the compounding impacts of unregulated tourism infrastructure expansion remain understudied. Without systematic spatial planning integrating ecological and cultural preservation, escalating development may irreversibly degrade both natural capital and socioeconomic sustainability. As a critical ecotone exhibiting concentrated ethnic settlements, altitudinal biodiversity, and evolving development tensions, the LJD serves as an exemplary microcosm for examining sustainable tourism paradigms in China’s mountainous frontiers.

Figure 1.

Location of the Study Area.

2.2. Multi-Constraint Synergistic Analysis Framework

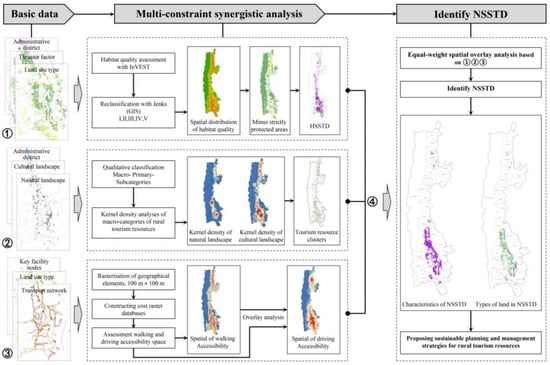

Rural tourism functions as a complex adaptive system where synergistic interactions and cascading effects coexist among ecological, resource, and infrastructural subsystems [3]. Achieving equilibrium within this system necessitates a holistic analytical approach. To this end, this study establishes a tri-constraint synergistic framework integrating habitat quality, resource endowment, and facility accessibility (Figure 2), where “constraints” denote critical systems that regulate rural tourism development potential through both limitation and optimization mechanisms. The habitat quality constraint operationalizes ecosystem service theories and habitat suitability modeling. The resource endowment constraint quantifies the spatial clustering of competitive assets that natural landscapes and cultural heritage drive regional tourism appeal [40]. Facility accessibility constraints derive from knowledge contributions such as spatial equity and gravity modeling [36], emphasizing the impact of infrastructure on the efficiency of rural tourism resource utilization, as well as the cost of tourist experience and the ease of community participation. Methodologically, interdisciplinary synthesis and complexity theory frameworks offer robust analytical paradigms, enabling the deconstruction of nonlinear dynamics and emergent interactions among evolving system components [41], provide methodological foundations for multi-constraint synergistic assessments that enhance resource utilization efficiency, system adaptability, and innovation capacity [27]. This theoretical basis allows us to decode the spatial allocation mechanisms through the following phases:

Figure 2.

Theoretical Framework of Multi-Constraint Synergy.

- (1)

- Habitat Quality Constraint: This constraint operationalizes ecosystem service theories via the InVEST model to assess the Habitat Space Suitable for Tourism Development (HSSTD).

- (2)

- Resource Endowment Constraint: This constraint quantifies the spatial clustering of competitive assets, where natural landscapes and cultural heritage drive regional tourism appeal [40], using kernel density analysis and other GIS techniques.

- (3)

- Facility Accessibility Constraint: Derived from spatial equity principles, this constraint emphasizes the impact of infrastructure on resource utilization efficiency and community participation, evaluated through cumulative cost-distance algorithms.

- (4)

- Given the absence of prior knowledge to justify preferential weighting, we adopt an equal-weight assumption for the constraint interactions—a rational initial strategy that acknowledges the fundamental role of each subsystem. The final phase involves identifying the NSSTD through a spatial superposition analysis of the three constrained dimensions.

2.3. Data Collection

The data utilized in this study are current as of November 2023 (Table 1). It should be noted that the land use was reclassified according to China’s ‘Guidelines for Classification of Land Use and Sea Use for Territorial Spatial Survey, Planning, and Use Control’. Rural tourism resource datasets were compiled through a synthesis of governmental statistical reports and field surveys conducted by the research team from March 2021 to November 2023 under the Landscape and Planning Management Practice Project conducted by the research team for the study area. Census protocols adhered to the ICOMOS Principles Concerning Rural Landscape Heritage (2017), defining cultural landscapes as integrated systems delivering multifunctional benefits—encompassing socioeconomic value, cultural sustenance, and ecosystem services. To systematically construct a township-scale tourism resource database, this study employed an integrated three-step methodology—multi-source pre-inventory, participatory field verification, and standardized classification—to ensure the scientific rigor and completeness in identifying, validating, and categorizing the 2875 resource sites.

Table 1.

Data Collection and Sources.

- (1)

- Multi-source pre-inventory: An initial inventory was compiled by synthesizing governmental planning documents, local gazetteers, tourism statistical reports, and user-generated content (check-in points, tracks) collected from outdoor trajectory platforms (2bulu APP). This step aimed to ensure broad coverage of potential resources.

- (2)

- Participatory field verification and data collection: Building upon the pre-inventory, a working group comprising researchers, local cultural and tourism department staff, and community representatives conducted field surveys. Employing Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA) techniques [42], including community workshops and on-site visits, the team verified the location, supplemented attributes, corrected GPS coordinates for each site, and documented local knowledge. This process served to validate and enrich the preliminary data.

- (3)

- Standardized classification and database construction: All verified resource sites were systematically classified and coded according to the “Chinese National Standard Classification, Investigation, and Evaluation of Tourism Resources (GB/T 18972-201)” [43]. A standardized geospatial database was then constructed, containing geographic coordinates, attributes, and classification codes for each site.

2.4. Methods

2.4.1. InVEST Model

This study employs the Habitat Quality (HQ) module of the Integrated Valuation of Ecosystem Services and Tradeoffs (InVEST) model (v3.14.1), developed by Stanford University, to assess spatial heterogeneity of habitat quality [44]. As a scientific toolkit for quantifying ecosystem services, ecological risk, and spatial planning outcomes, the model operationalizes threat source identification through land use typology analysis [45], establishing threat-habitat interaction matrices to compute adverse impacts via Habitat Degradation Degree (HDD) and Habitat Quality Index (HQI) core metrics. The analytical framework incorporates linear/exponential distance decay functions to simulate threat intensity attenuation across ecological spaces, with algorithm parameters calibrated following China’s ‘Guidelines for Classification of Land Use and Sea Use for Territorial Spatial Survey, Planning, and Use Control’. The formula is

where refers to the linear distance between grids and , and refers to the maximum action distance of the threat source .

Calculation of the degree of habitat degradation, the formula is

where refers to the degree of habitat degradation of the th habitat image element in habitat type . refers to the number of threat factors for the habitat, refers to all rasters on the threat raster map, and refers to a set of rasters on the threat raster map. refers to the weight of the threat factor . refers to the number of threat factors on each raster. refers to the effect (linear or exponential) of threat factor on each raster of the habitat. refers to the effect of local conservation policies. refers to the relative sensitivity of each habitat to different threat factors.

Habitat quality index calculation, the formula is

where refers to the habitat quality score for the th habitat image element in habitat type , taking values in the range [0, 1]. refers to the suitability of habitat type . refers to the half-saturation parameter, which usually takes the value of 0.5. refers to the model default parameter.

The parameterization of threat factors for the InVEST model was based on its technical guidelines and precedents from applications in similar ecosystems, such as mountainous regions [46], river basins [47], and loess hilly areas [48,49]. We then systematically calibrated these parameters to reflect the unique environmental profile of the dry-hot valley, which is characterized by a land cover pattern dominated by orchards and dry farmland, with limited paddy fields and irrigated lands. The calibration rationale stems from the distinct mechanisms and spatial patterns of anthropogenic disturbance in dry-hot valleys compared to humid regions. Accordingly, key adjustments were made: urban zones and rural settlements were assigned higher degradation weights with an exponential decay function to simulate their intensive and far-reaching impacts. In contrast, orchards and bare lands were given lower weights, shorter maximum impact distances, and a linear decay to better represent their more localized and moderate disturbance. This localized parameter set aims to more accurately simulate the spatial process of habitat degradation in the local context. Six land use types were ultimately identified as threat factors (Table 2). The habitat quality index system was operationalized through two diagnostic dimensions: habitat suitability coefficients across land use types and threat sensitivity gradients (Table 3). This establishes the first standardized assessment protocol tailored to xeric valley ecosystems.

Table 2.

Habitat threat sources and related parameters.

Table 3.

Habitat suitability of land use types and sensitivity to different threat sources.

2.4.2. Geographic Concentration Index and Kernel Density Estimation

Geographic Concentration Index. The geographic concentration index quantifies the spatial agglomeration intensity and distribution equilibrium of rural tourism resource clusters [50]. This index ranges from 0% to 100%, with higher values indicating greater resource concentration across villages, whereas lower values denote dispersion patterns. Let be the benchmark concentration index under uniform distribution [51], , clustered distributions are identified when , with dispersed patterns otherwise. The formula is:

where refers to the number of resource sites in village , refers to the total number of resource sites, and refers to the total number of villages.

Kernel Density Estimation (KDE). The KDE was used to estimate the spatial agglomeration characteristics of natural and cultural landscape resources [52]. It is assumed that X1, X2, …, Xn are independent and identically distributed samples drawn from the overall population with distribution density function . The method nonparametrically estimates at any spatial coordinate . The formula is

where refers to the number of resource sites, ( refers to the distance from kernel density valuation point to , refers to the kernel function, and refers to the width of the surface extended in space with as the origin.

Coefficient of Variation (CV). A secondary validation was performed using the CV to quantify spatial dispersion patterns of potential tourism resources through Voronoi polygon area analysis. Validation thresholds were defined following Duyckaerts C’s operational framework [53], if then it is random distribution, if , it refers to uniform distribution, if , it refers to clustered distribution. This nonparametric approach statistically verifies the spatial autocorrelation intensity derived from kernel density estimations. The formula is

where refers to the total number of Voronoi polygons, refers to the area of the Voronoi polygon of th, and refers to the average value of .

2.4.3. Cumulative Cost Distance Algorithm

This study applies the cumulative cost distance algorithm to assess the accessibility of rural resource nodes, a GIS-based spatial optimization method that quantifies fine-grained accessibility patterns in small-scale spaces such as villages and towns through resistance surface modeling [54]. The formula is

where refers to the depletion value of the th image element, refers to the depletion value of the ()th image element in the direction of motion, and refers to the total number of image elements.

This study simulates multimodal accessibility (walking/driving) of rural tourism resources to assess regional cluster connectivity, accounting for their dual service roles to tourists and villagers. The methodology involves the following steps:

Rasterizing geographic elements such as land, water and roads within the study area are rasterized and the corresponding time-cost values are set. (1) In order to finely describe the accessibility of resource sites at the village and township scale, the raster size was selected to be 100 m × 100 m grids. (2) The road system is categorized into expressways, national highways, provincial highways, county roads, and township roads. This classification adheres to Clause 2.1.4 of the industry standard “Highway Route Design Specifications (JTG D20-2017)” of the People’s Republic of China, drawing upon existing research findings from comparable regions [55,56]. Based on the Third National Land and Spatial Survey database, various land elements were extracted, with water and land elements categorized into 17 types. Drawing on existing research findings [57], the assignment standards for various indicators were further optimized (Table 4). (3) The affiliated cost attributes of each type of vector elements are used to construct the cost raster databases. (4) The Cost Distance tool in ArcGIS 10.7 was used to calculate the cost-weighted distances between motorway exit stations, stations, market towns and resource sites, and to map the walking and driving accessibility features, respectively. (5) Considering that driving is the primary mode of transportation for tourists reaching scenic areas, and analysis indicates that the driving-accessible space covers 88.31% of the walkable area, this study ultimately adopts driving accessibility as the primary indicator for characterizing regional connectivity, to be used in subsequent overlay analysis.

Table 4.

Assignment of Accessibility Calculation.

2.4.4. GIS-Based Equal-Weight Spatial Overlay Analysis

In the spatial overlay analysis that synthesizes the three constraints, an equal-weight assumption was applied. This choice is motivated by the current lack of empirical basis or domain-specific studies that could robustly justify a differential weighting scheme for habitat quality, resource endowment, and facility accessibility within the unique context of dry-hot valleys. Adopting equal weights, while a simplification, provides a baseline, reproducible model that transparently avoids subjective weighting judgments. It allows the analysis to highlight areas where the three constraints spatially converge or conflict based on their own inherent distribution patterns, not on externally imposed hierarchies. As a proven spatial optimization technique [58], this method has demonstrated efficacy in territorial zoning [59] and land use planning [60]. The algorithm operationalizes Boolean logic combinations to delineate the NSSTD through three-dimensional constraint mapping, effectively revealing latent landscape configurations that balance ecological integrity with tourism infrastructure requirements. The formula is

where and refer to the vector targets of the resource agglomeration dataset and the accessibility dataset, respectively, and refers to the domain of influence for and to perform the overlay calculations in the ecological supply space. are analyzed as the smallest computational units in the overlay analysis, and these computations are independent of each other and parallelizable.

3. Results and Analyses

3.1. Characteristics of Spatial Distribution of Potential Ecological Supply

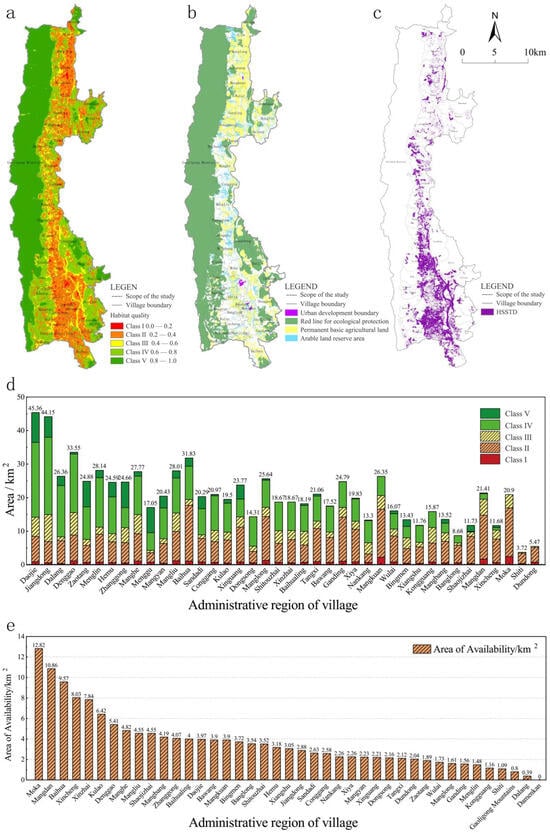

The InVEST model-derived habitat quality map (Figure 3a) reveals high overall habitat quality in the study area, with premium zones concentrated in western and southeastern sectors contrasting with degraded central habitats. The Gaoligongshan Nature Reserve was identified as the optimal habitat quality unit. The habitat distribution space was divided into five categories by the Jenks natural breaks classification [9], with category I regarded as low-quality habitat space, category II and III regarded as medium-quality habitat space, and category IV and V regarded as high-quality habitat space. Class I: 33.86 km2, 2.59%; Class II: 309.98 km2, 23.68%; Class III: 120.16 km2, 9.18%; Class IV: 344.64 km2, 26.33%; Class V: 500.24 km2, 38.22%.

Figure 3.

The HQ Assessment Features: (a) Spatial distribution of the HQ; (b) Strictly protected land; (c) the HSSTD delineation; (d) Village-scale HQ distribution; (e) Village-scale HSSTD distribution.

Class I areas represent village and town construction space with poor habitat quality, while Class IV and V areas are the core and buffer zones of the Gaoligongshan Nature Reserve, areas with the highest quality ecological resources and candidates for the proposed national park. According to Article 18 of the Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on Nature Reserves and Articles 17 and 18 of the Interim Measures for the Administration of National Parks, “human activities are prohibited in core protection zones in principle,” and “developmental and productive construction activities are prohibited in general control zones.” Therefore, the study determines that Class II and Class III areas are suitable habitat spaces for rural tourism development, collectively 430.14 km2, accounting for 32.86% of the total area of the region. However, the area also contains a large amount of ecological protection forest land, permanent basic farmland and arable land reserve (Figure 3b), with a total area of 162.82 km2. These sites must be strictly protected according to Article 4 of the “Administrative Measures for the Permanent Basic Farmland Protection Red Line” and Article 7 of the “Measures for Ecological Environment Supervision of Ecological Protection Redlines (Trial).” Through the spatial superposition of constrained deletion, the HSSTD was obtained (Figure 3c), with an area of 267.32 km2, which was distributed along the west side of the Nujiang River in a belt-like manner, concentrating in the southern part of the area. Village-scale analysis showed Daojie, Jiangdong, Dalang, Denggao, and Baotang containing the highest proportions of premium habitats in class IV and V, but the opposite is true for Dundong, Shiti, Moca, Xincheng, and Mangdan villages (Figure 3d), while southern Baihua, Moca, Mangdan and Xincheng villages, as well as central Mangliu and Manghe villages, and northern Mangkuan village, demonstrated superior tourism development potential, collectively accounting for 29.33% of HSSTD (Figure 3e). These findings reveal significant spatial heterogeneity in habitat quality constraints through quantification. The clear east–west differentiation and the identification of specific villages with high-or low-quality habitat establish the ecological baseline for tourism planning.

3.2. Typology and Spatial Aggregation Patterns of Rural Tourism Resources

The resource inventory classified 2875 tourism assets into 2 macro-categories, 7 primary classes, and 16 subclasses (Table 5), with natural landscapes dominating (2342 sites, 81.46%) over cultural resources (533 sites, 18.54%). The largest main categories of tourism resources are vegetation landscape resources, accounting for 76.21%, utilitarian buildings and core facilities, accounting for 9.91%, and intangible cultural heritage, accounting for 4.53%.

Table 5.

Types and Characteristics of Rural Tourism Resources.

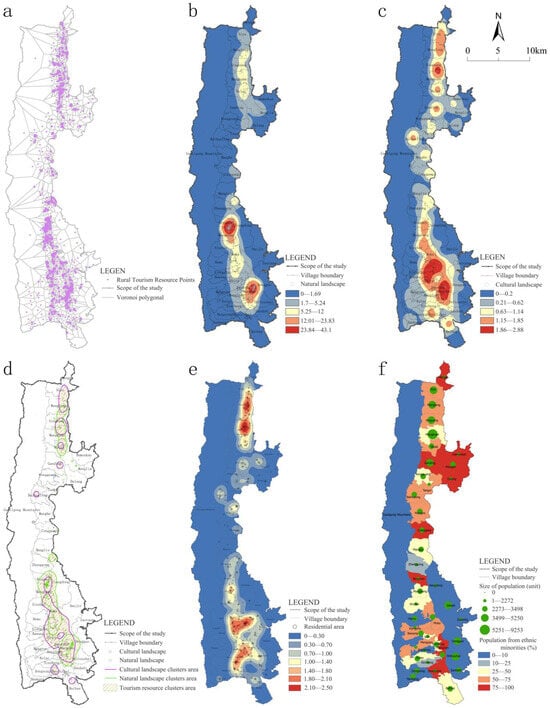

“Barbell-shaped” structure of agglomeration distribution characteristics. the geographic concentration index ( = 27.67, = 15.43) and Voronoi-derived coefficient of variation (CV = 548.20%, >64%) jointly confirmed clustered distributions (Figure 4a). For the kernel density analysis of natural landscapes, the Jenks of GIS is used, which is divided into five categories, and the kernel density characteristic map of natural landscape resources is obtained (Figure 4b). Considering the overall large number of natural resources and the relatively narrow development spillover effect, the range of threshold lower than 5.25 is regarded as a low resource agglomeration area, and those larger than 5 are regarded as a high resource agglomeration area, presenting Mangkuan-Xinguang Village agglomeration area, Propmiao Village agglomeration area and Mangdan Village agglomeration area. The same method is used to obtain the characteristic map of kernel density of cultural landscape resources (Figure 4c), because the overall number of cultural landscape resources is relatively small compared to natural landscape, we regard the range of threshold lower than 1.14 as low resource agglomeration area, and those greater than 1.14 as high resource agglomeration area, exhibited axial aggregation along the Nu River, which are Mangdan-Moca Village agglomeration area and Xinguang-Sia Village agglomeration area, albeit with greater dispersion than natural landscape assets.

Figure 4.

Spatial Distribution Characteristics of Tourism Resources: (a) Voronoi polygon analysis; (b) Kernel density of natural landscapes; (c) Kernel density of cultural landscapes; (d) Resource cluster distribution; (e) Community kernel density; (f) Ethnic minority population distribution.

Overlay analysis revealed a polarized “barbell-shape” spatial configuration, characterized by high-density resource clusters at the northern and southern extremities and a low-density belt in the central area (Figure 4d). This configuration is key to understanding the spatiality of the “ecology-resource-facility” complex system in the LJD. Its formation results from the long-term, synergistic shaping by natural geographical foundations, socio-historical sedimentation, and modern infrastructure networks. The relatively open terrain at the northern and southern ends of the study area has provided a longstanding spatial carrier for settlement expansion and agricultural activities. In contrast, the central area, confined by the deep Nu River Gorge and flanking mountains, features fragmented usable land, which inherently restricts the formation of large-scale resource agglomerations. Townships such as Mangkuan village and Mangdan village at the two ends are traditional centers for ethnic minorities (e.g., Dai, Lisu). Their rich intangible cultural heritage (e.g., Water-Splashing Festival, Kuoshi Festival) and the co-evolved tangible landscapes (e.g., religious architecture, vernacular dwellings) form the core of cultural landscape resources. This is corroborated by the high spatial congruence (82%) between resource clusters and ethnic settlements (Figure 4e,f). Provincial Highway 237, serving as the north–south arterial corridor, has attracted the layout of tourism service facilities at its key nodes, thereby reinforcing and consolidating the resource agglomeration at the two poles.

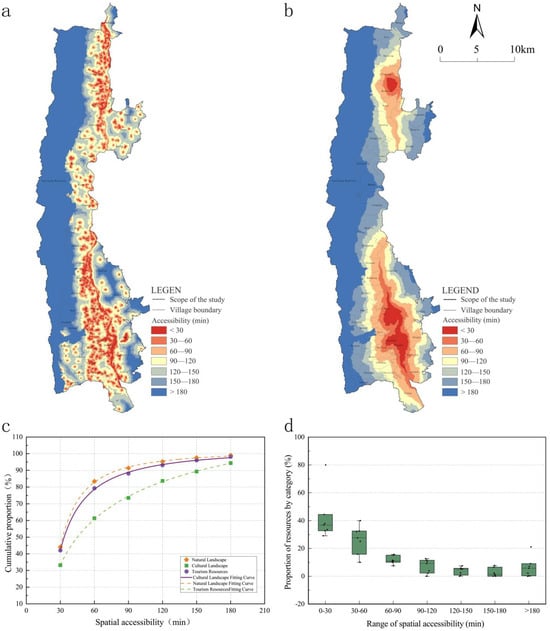

3.3. Spatial Accessibility Characteristics of Rural Tourism Resources

Accessibility analysis reveals a “concentric layered” pattern, which visually represents the spatial gradient of the facility accessibility constraint—a core dimension of our framework. By combining the spatial distribution of rural tourism resources in the LJD with the accessibility analysis, this study classifies the accessibility space into 3 classes and seven hierarchical tiers according to the traveling time. High accessibility area (<30 min), medium accessibility area (30–60 min, 60–90 min), and low accessibility area (90–120 min, 120–150 min, 150–180 min, >180 min). And the weight of each class range was counted according to the resource type, as a way to reveal the public infrastructure accessibility pointing characteristics of rural tourism resources. The distribution of rural tourism resources in terms of walking accessibility (Figure 5a) shows a distribution characteristic of ‘large dispersion and small aggregation’. Resource sites within the 30 min walking distance are mainly localized clusters along Provincial Highway 237, especially in the villages of Mangdan, Moca and Bengmiao in the southern part of the study area. Driving accessibility demonstrates distinct concentric zones (Figure 5b) with obvious differences in the distribution of rural tourism resources within different access ranges. Through the spatial superposition analysis of the accessibility range of walking and driving, it is found that the driving accessibility space covers 88.31% of the walking areas, establishing driving access as the primary analytical framework. This dominance underscores that regional connectivity and tourist flows are primarily channeled along the road network, reinforcing its role as a decisive enabling or limiting factor for resource utilization.

Figure 5.

Spatial Accessibility Characteristics: (a) Walking accessibility distribution; (b) Driving accessibility distribution; (c) Cumulative resource proportion by travel time; (d) Resource category proportion by accessibility range.

By comparing the relationship between travel time consumption and the spatial distribution of rural tourism resources (Figure 5c), it is found that, with the increase in travel time, the cumulative percentage of the main categories of rural tourism resource sites increases, and the percentage of the resource sites within 30 min reaches 42.02%, within 60 min reaches 79.31%, within 90 min reaches 88.08%, and the travel time in the range of 180 min has reached 99.02%. The formation of this concentric pattern is primarily governed by the radial structure of the road network emanating from key settlements and transport nodes along Provincial Highway 237. However, the pronounced increase in travel time beyond 90–120 min, particularly in the central-northern sector, indicates a “structural hole” in accessibility. This discontinuity, mirroring the “barbell-shaped” resource distribution, results from the reliance on a single arterial road with limited lateral connectivity, thereby exposing a critical bottleneck where the facility constraint severely limits the development potential of otherwise resource-rich areas. Comparing the matching relationship between the spatial hierarchy of accessibility and the spatial distribution of the main category of rural tourism resource sites (Figure 5d), it is found that with the increase in the traveling time consuming, each main category of rural tourism resource sites gradually decreases. Sectoral analysis identifies water resources (85.7%), vegetation (86.2%), and tourism commodities (85.9%) as dominant within 90 min drive ranges, collectively constituting 74.37% of total assets. This spatial congruence between resource clusters and service infrastructure not only confirms high development viability with minimized implementation costs in the LJD, but also exemplifies a positive synergy between the resource endowment and facility accessibility constraints under the multi-constraint framework.

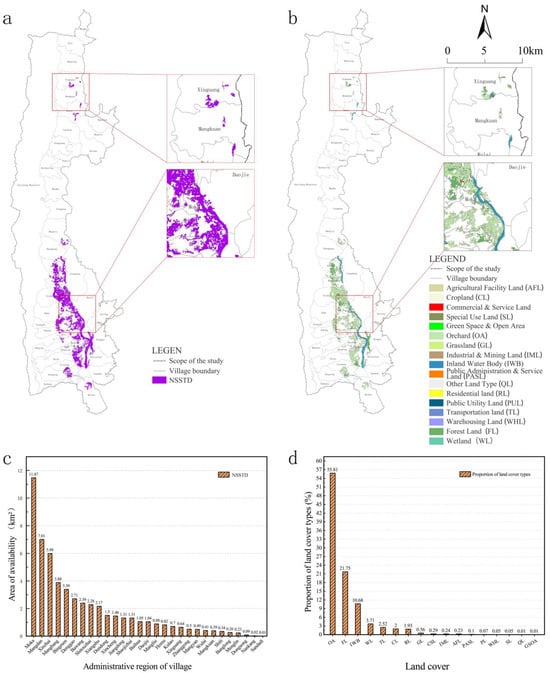

3.4. Delineating Natural Spatial Suitability for Tourism Development

The NSSTD identification focuses on potential development blocks of a certain scale that can form comprehensive service capabilities, targeting newly added development spaces that leverage natural and landscape resources. Integrating spatial overlay analysis with exclusion criteria that areas <10 ha that refers to the average construction land size of the built rural tourism scenic spots of 3A grade, and >180 min travel time excluded, this study identified 54.74 km2 of the NSSTD (4.18% of total area) by synthesizing habitat suitability (Figure 3c), resource clusters (Figure 4d), and vehicular accessibility (Figure 5b).

The delineation of NSSTD represents the spatial outcome of the synergistic interaction among the three constraints. It exhibits pronounced spatial heterogeneity (Figure 6a), with high-density southern clusters versus sparse northern distributions. This pattern directly reflects the convergence of favorable conditions, southern areas benefit from the synergy of medium habitat quality, high resource endowment, and high accessibility, whereas northern areas are limited by weaker accessibility and resource clustering. The NSSTD covers 29 villages, accounting for 70.73% of the total number of villages. Moka village dominates with 11.47 km2 (20.95% of total NSSTD), followed by four contiguous villages (Mangdan, Xinzai, Mangbang, Bingmen) contributing 31.74 km2 (57.98%). Linear distributions along the Nu River and Provincial Highway 237 account for 17.22 km2 (31.46%) across 10 villages (1–3 km2 each), while fragmented remnants (5.78 km2, 10.56%) occur in 14 peripheral villages (Figure 6c).

Figure 6.

Spatial Characteristics of the NSSTD: (a) the NSSTD spatial patterns; (b) Land cover types in the NSSTD; (c) the NSSTD per village; (d) Land cover differences.

The NSSTD comprises 17 land use types (Figure 6b), with three dominant categories identified through composition analysis, Orchard (OA: 30.55 km2, 55.81%), Forest Land (FL: 11.90 km2, 21.75%), and inland water bodies (IWB: 5.85 km2, 10.68%), collectively constituting 88.24% of NSSTD. Secondary contributors include wetland (WL: 3.71%), transportation land (TL: 2.52%), cropland (CL: 2.0%), and residential land (RL: 1.93%), with marginal categories aggregating 1.63% (Figure 6d). The spatial composition and land use profile of the NSSTD provide a concrete, spatially explicit basis for formulating the differentiated planning strategies. The predominance of horticultural land, woodland, and inland water bodies suggests that future development should prioritize low-impact, nature-based tourism models within these identified zones.

4. Discussion

4.1. Methodological Innovation and Validation of the Multi-Constraint Synergistic Evaluation Framework

This study proposes a multi-constraint synergistic framework as a paradigm shift from the reductionist approaches that have long constrained sustainable tourism planning in fragile regions. While previous research has excelled in examining individual subsystems—ecology, resources, or infrastructure—in isolation [9], it has consistently fallen short in addressing their critical spatial interdependencies. Our framework moves beyond this single-dimensional or two-dimensional lens by systematically integrating the InVEST model, KDE, and cumulative cost-distance algorithms into a unified spatial analytical workflow. The framework’s core innovation is its conceptualization of rural tourism as a complex adaptive system [3], where habitat quality, resource endowment, and facility accessibility are treated as fundamental, interacting constraints. This theoretical grounding allows us to transcend mere spatial overlay and instead model the dynamic equilibria and trade-offs within the system. A pivotal methodological decision that enables this integration is the adoption of an equal-weight assumption for constraint interactions. This is not an oversight but a rational initial strategy that acknowledges the foundational and non-negotiable role of each subsystem in the context of sustainable development, ensuring that no single dimension is prematurely marginalized in the analysis. The empirical validation of the LJD framework demonstrates that it not only maps spatial patterns of habitat quality, tourism resource endowment, and facility accessibility, but also reveals the synergistic and conflictual interactions between them to delineate the NSSTD. The framework proves uniquely capable of identifying latent landscape configurations that are invisible to single-dimension assessments, such as areas where development potential emerges from the synergy of medium habitat quality with high resource endowment and accessibility, or conversely, resource-rich zones that are rendered unsuitable due to ecological or infrastructural constraints.

- (1)

- Habitat Quality as the Foundational Ecological Constraint

Within our multi-constraint framework, habitat quality constitutes the non-negotiable ecological foundation for tourism development. Our assessment achieves a high overall habitat quality (844.88 km2, 64.55% of total area) yet with pronounced spatial heterogeneity. The identification of premium habitats concentrated in the western and southeastern sectors, contrasted with a central low-quality belt, provides a critical baseline for spatial planning. The core methodological innovation was a localized calibration of the InVEST model’s threat factors, tailored to the dry-hot valley’s unique land cover profile. To address this region’s abundance of fruit orchards and scarcity of paddy/irrigated fields, we consolidated the latter into a single ‘cultivated land’ threat factor and, critically, introduced ‘fruit orchard’ as an independent threat. This calibration, a departure from the generic parameters used in prior studies [18,19], enhances the precision of habitat degradation simulations in horticultural landscapes and increases the generalizability of the assessment framework for analogous arid regions. This refinement enhances the accuracy of habitat degradation simulations in landscapes dominated by orchards and horticulture, thereby improving the generalizability of the assessment system for similar dry-hot valleys.

Ecological resources, landscape types, and cultural heritage are pivotal assessment indicators for regional habitat ecological security [61]. The constraining mechanism of habitat quality is operationalized through a development exclusion principle based on stringent conservation policies. We emphasize that habitat quality assessment within ecological resource spaces necessitates the strict implementation of spatial development interventions to protect ecosystem integrity [62]. This perspective reinforces the sustainability of rural ecotourism development under our proposed multi-constraint synergistic framework. We demonstrated that not all high-quality natural spaces are suitable for tourism development. Specifically, in accordance with the “Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on Nature Reserves” and the “Interim Measures for the Administration of National Parks,” the core and buffer zones of the Gaoligongshan Nature Reserve—a candidate area for China’s national park system, encompassing Class IV and V habitats—were strictly excluded from development suitability assessment. This strategy was reinforced by overlaying legally protected zones, including the ecological protection redline, permanent basic farmland, and arable reserve land, all mandatorily delineated according to the “Administrative Measures for the Permanent Basic Farmland Protection Red Line” and the “Measures for Ecological Environment Supervision of Ecological Protection Redlines (Trial).” This policy-informed delineation refines the oversimplified principle that equates high habitat quality solely with tourism value [9], firmly re-establishing its primary role as a constraint for conservation.

Consequently, the habitat quality constraint effectively channels development away from the most sensitive western ecoregion towards the more adaptive central and southern corridors. The area along the Nu River is a settlement cluster with relatively scarce high-quality natural landscape resources; however, developing rural tourism here plays a key role in promoting comprehensive rural revitalization. For instance, villages like Mangdan and Moka, despite lacking premium natural landscapes, possess rich cultural heritage and distinctive ethnic characteristics. This disparity in resource endowment underscores the necessity to dynamically adjust and select an appropriate resource assessment index system during rural tourism development. Class I areas, characterized by dense human settlements and agricultural production with poor habitat quality, were identified through field surveys and comparative validation. These areas, often surrounded by abandoned and forested land, were prioritized for ecological restoration measures to improve habitat quality rather than for development. This spatial prioritization provides a scientifically robust and legally compliant basis for territorial spatial governance. This mechanism ensures that the ecological carrying capacity is not exceeded, thereby securing the long-term sustainability of tourism within this fragile landscape.

- (2)

- Resource Endowment as the Development Driver Constraint

The resource endowment constraint captures the spatial clustering of tourism assets; we compared and analyzed the results with similar studies, and found that while there were similarities with established studies, our study highlighted some feasibility differences. Our fine-grained inventory and kernel density analysis at the township scale revealed a distinct “barbell-shaped” distribution, with resource clusters polarized at the southern and northern extremities of the LJD valley. This finding advances beyond large-scale macro-analyses by pinpointing the exact locations and composition of resource agglomerations. A critical insight from our multi-constraint synergy is the spatial disjunction between resource wealth and ecological integrity. We found that high-resource concentration areas are predominantly located in low-to-medium habitat quality zones, creating two primary conflict types: medium-habitat and high-resource and low-habitat and high-resource areas. The latter, in particular, should not be prioritized for development but rather for ecological restoration, as initiating tourism without improving the foundational habitat quality would be unsustainable. This “spatial blind spot” is a key finding that traditional one-dimensional resource assessments consistently miss but is critical for sustainable planning.

Furthermore, we focused on mining the agglomeration characteristics of different types of rural tourism resources at the township scale, constructed a macro categories-primary classes-subclasses of rural tourism resources, and carried out a comprehensive and refined spatial configuration assessment from the two major categories of natural landscapes and cultural landscapes to make up for the inadequacy of the established large-scale macro-analysis framework based on panel data [40]. It is found that the high spatial congruence between resource clusters and ethnic settlements underscores that cultural landscapes are integral to the resource endowment. On the one hand, it shows that the rural tourism resource agglomerations in the study area are rich in ethnic and cultural characteristics, and the settlements can better protect the natural landscape and pass on the historical and cultural heritage in the process of expansion. In addition, sustainable development of rural tourism resources can both expand tourism development and effectively enhance the well-being of community residents. However, this synergy also presents a challenge: the “structural hole” in the central part of the study area, characterized by a break in both resource continuity and transport connectivity, creates a bottleneck for integrated regional development. Villages like Conggang and Baihualing, trapped in this structural hole between the river and the nature reserve, exemplify how resource accessibility, not just presence, defines development potential. Therefore, the resource endowment constraint is not merely about mapping assets but about evaluating their spatial feasibility within ecological and infrastructural limits. It dictates that development potential is not uniform across resource-rich zones and demands a diagnostic approach that identifies areas requiring restoration, those suitable for immediate development, and those needing targeted infrastructure investment to unlock their potential.

- (3)

- Facility Accessibility as the Dual-Nature Constraint

The facility accessibility constraint completes our multi-constraint framework by evaluating the efficiency of spatial connectivity, which enables a more scientific identification of the NSSTD. Rural infrastructure is a historical representation of the evolution of regional population migration and settlement, and is fundamental to guaranteeing the high quality and low-cost allocation of rural tourism resources, as well as the sustainability of rural communities’ participation in tourism. The synergistic analysis of the three is a lesser concern of established studies. Our analysis revealed a “concentric layered” pattern, with 88.08% of tourism resources accessible within a 90 min drive in the LJD valley. This high coverage confirms infrastructure’s role as a powerful development catalyst by defining the functional hinterland of existing resource clusters. However, the constraint’s dual nature is exposed when this analysis is synergized with research on habitat quality and resource endowment. The ‘concentric layered’ pattern exhibits a critical ‘structural hole’ in the central-northern sector, where travel times jump to 120–180 min due to reliance on a single provincial highway with weak feeder networks. This finding demonstrates that accessibility is not merely a function of distance but of network structure, creating a stark developmental discontinuity that mirrors the “barbell-shaped” resource distribution.

The case of the Baihualing 3A-level scenic spot within this structural hole is instructive. Despite poor accessibility, its success in attracting niche markets (e.g., birdwatchers, trekking enthusiasts) with unique ethnic Lisu culture and location in a nature reserve buffer zone validates a critical principle: highly specialized tourism demand can, to an extent, tolerate accessibility constraints. This exception proves that our framework does not mechanistically exclude all poorly accessible areas but highlights ones requiring tailored, low-impact development strategies and careful attention to their ecological sensitivity. Ultimately, the accessibility constraint forces a strategic prioritization. It directs initial infrastructure investments towards closing the structural hole to enhance regional integration, while simultaneously identifying sites where unique resources justify development despite access limitations, provided that stringent ecological safeguards from the habitat quality constraint are upheld. This nuanced understanding is essential for optimizing resource allocation in fragmented landscapes.

4.2. Implications for Territorial Space Governance in Ecologically Fragile Areas

The multi-constraint synergistic analysis framework developed in this study provides innovative insights and actionable pathways for territorial spatial governance in ecologically fragile regions such as the dry-hot valley.

- (1)

- Providing a Scientific Basis for “Multi-Plan Integration” and Zoning Regulation

The delineation of the NSSTD offers a scientifically robust and spatially explicit analytical method for formulating practical “Multi-plan Integration” village plans at the township scale. This delineation provides a transparent basis for zoning decisions by guiding tourism development towards the southern NSSTD corridors while enforcing strict protection in the Gaoligongshan Nature Reserve, thereby directly addressing the core challenge of balancing conservation and development. This science-informed zoning prevents the misallocation of tourism development into ecologically sensitive areas based on single-dimensional assessments, a common pitfall of growth-centric tourism planning. Operationally, we recommend that local governments formally incorporate the identified NSSTD into the dynamic revision of Practical Village Plans for “Multi-plan Integration,” clearly defining the spatial boundaries and regulatory requirements for rural tourism. This integration ensures that tourism planning transitions from an idealized, resource-centric boundless thinking to a governance-oriented, boundary-thinking approach grounded in territorial spatial management.

- (2)

- Advocating for Differentiated Zoning and Cross-Regional Ecological Compensation

Our multi-constraint analysis reveals a heterogeneous landscape that necessitates differentiated governance strategies rather than a one-size-fits-all approach. By identifying areas with high tourism resource value coupled with either low accessibility or low habitat quality, we pinpoint regions requiring targeted infrastructure investment or ecological restoration to achieve regional integration. This supports a spatially sensitive strategy: prioritizing integrated development and branding in high-density southern NSSTD clusters (e.g., Moka and Mangdan villages), while implementing ‘micro-transformation and refined enhancement’ actions in northern structural hole villages to improve regional connectivity and develop niche tourism. Furthermore, the framework substantiates the necessity of establishing a horizontal ecological compensation mechanism. Communities in the western high-habitat-quality zones, which contribute to global ecological security by restricting development, should be compensated through fiscal transfers from tourism revenues generated in the southern development zones. This mechanism internalizes environmental costs and benefits, fostering regional equity and sustainable stewardship.

- (3)

- Enabling Dynamic Monitoring and Adaptive Management through Digital Governance

The static nature of conventional planning is ill-suited for managing dynamic socio-ecological systems and tourism development. Our framework, built upon GIS and spatial modeling, provides the foundational architecture for a “multi-constraint synergistic monitoring platform.” Such a digital platform could enable the real-time monitoring of land use changes, tourism resource development sequencing, infrastructure planning, and key ecological indicators within the region. This data-driven approach facilitates adaptive management, allowing planners to assess the effectiveness of strategies, detect external disturbances early, and make timely adjustments. This shifts the governance paradigm from a static, blueprint-based model to a dynamic, evidence-based process. Consequently, it provides the analytical methods and data support for the dynamic adjustment of China’s “Three Zones and Three Lines” (urban space, agricultural space, ecological space, corresponding, respectively, to the delineated urban development boundary, permanent basic farmland protection redline, and ecological protection redline) within territorial spatial governance.

4.3. Spatial Strategies for Sustainable Rural Tourism Development in Dry-Hot Valley Regions

Based on the NSSTD and the spatial heterogeneity of the constraints—habitat quality, resource endowment, and facility accessibility—this study formulates targeted spatial strategies to operationalize sustainable rural tourism development in the LJD. These strategies translate the assessment findings into actionable planning interventions, providing spatial guidance for rural tourism development in similar regions.

- (1)

- Integrated development in high-potential southern clusters. The southern NSSTD clusters (e.g., Moka and Mangdan villages) represent the primary catalyst for the regional tourism economy. Strategies here should prioritize comprehensive infrastructure upgrading and the creation of multi-functional spaces that deeply integrate local assets such as coffee cultivation, ethnic culture, and hot springs. This involves moving beyond isolated scenic spots to develop integrated circuits that offer immersive experiences, thereby maximizing the economic yield per unit of developed land, fostering a high-value tourism economy, and consolidating high-grade tourist attractions.

- (2)

- Niche tourism and connectivity enhancement in northern structural hole villages. For northern Baihualing villages within the “structural hole”—characterized by rich ethnic cultural resources but poor transport accessibility—a strategy of micro-transformation and refined enhancement is essential. Development should focus on low-impact, niche tourism products such as bird-watching, ethnic cultural experiences, and educational tourism, leveraging these unique local assets. Concurrently, strategic investments are required to upgrade critical transport nodes along Provincial Highway 237 and improve the feeder road network. Establishing additional tourist service centers will enhance the visitor experience while directly benefiting local communities.

- (3)

- Ecological restoration as a prerequisite for development in resource-rich, low-quality habitats. A critical finding of our framework is the identification of areas with high tourism resource value but low habitat quality. In these zones, tourism development must be preceded by ecological restoration. The core strategy involves implementing sustainable ecological restoration plans to improve habitat quality, while concurrently encouraging villagers to engage in low-impact agritourism and cultural activities (e.g., kapok viewing festivals, coffee picking). This approach ensures that future tourism development is built upon a restored and resilient ecological foundation, thereby transforming a potential liability into a long-term asset.

- (4)

- Strict ecological conservation and cross-regional compensation in western high-quality habitats. The western high-habitat-quality zones, primarily within the Gaoligongshan Nature Reserve, must be governed by a non-negotiable strategy of strict ecological conservation. Tourism development in these areas should be severely restricted, with the paramount task being the protection of biodiversity and ecosystem integrity. To mitigate the development restrictions imposed on local communities, it is crucial to establish a horizontal ecological compensation mechanism. This would channel a portion of the tourism revenues from the southern development clusters to support conservation efforts and sustainable livelihoods in the west, ensuring regional equity and reinforcing the value of preserved ecosystems.

4.4. Research Limitations and Further Guidance

While this study establishes a replicable and scientifically grounded assessment framework, several inherent limitations warrant acknowledgment and present avenues for future research. First, this study does not incorporate dynamic factors such as future land use changes or the evolution of infrastructure policies. This static approach may result in an incomplete assessment of areas with future tourism potential. Furthermore, the exclusion of areas smaller than 10 hectares, while pragmatic for identifying sizable development zones, inevitably omits numerous small-scale, culturally rich resources (e.g., homestays, micro-heritage sites). Future research should develop dynamic models that integrate time-series data, potentially from multi-spectral remote sensing and UAVs, to forecast land use changes. The potential of these omitted small-scale resources could be further explored through concepts like recreational network or corridor planning, linking them into a larger tourism circuit. Additionally, a core methodological choice was the adoption of an equal-weight assumption for the three constraints in the overlay analysis. Although this serves as a rational and transparent starting point in the absence of definitive prior knowledge, it may not accurately reflect the potential varying importance of habitat quality, resource endowment, and accessibility in different contexts. Subsequent studies should investigate differentiated weighting schemes, for instance, through Delphi expert surveys or the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), to enhance the model’s sophistication and context sensitivity. Despite these limitations, the analytical results of our multi-constraint synergistic framework demonstrate strong consistency with published governmental spatial planning schemes. This confirms its operational validity and its value in providing a scientifically robust and spatially explicit basis for territorial spatial planning, effectively complementing top-down plans with a detailed, resource-centric spatial configuration analysis. By addressing these limitations, subsequent research can further enhance the comprehensiveness and depth of the study.

5. Conclusions

This study developed and applied a multi-constraint synergistic assessment framework to address critical gaps in sustainable tourism planning for ecologically fragile regions. By systematically integrating the InVEST habitat model, kernel density estimation, and cumulative cost-distance algorithms, this research transcended the prevailing reductionist perspective and decoupled spatial analyses that have limited previous studies.

The framework quantified the distinct spatial heterogeneity of each constraint subsystem within the Nujiang dry-hot valley: (1) Habitat quality was high overall but exhibited a clear spatial dichotomy, with premium zones (Class IV–V, 844.88 km2) in the west/southeast contrasting with a central low-quality belt; (2) Tourism resources demonstrated a pronounced “barbell-shaped” clustered distribution at the northern and southern extremities, showing high congruence with ethnic settlements; (3) Facility accessibility formed a “concentric layered” pattern, with 79.31% and 99.02% of resources accessible within 60 and 180 min of driving time, respectively, establishing transport as a key development enabler.

More importantly, the overlay analysis revealed the synergistic and conflictual interactions that collectively shape development suitability. A key finding was the identification of the NSSTD (54.74 km2), which is not merely an aggregation of high-value areas from single constraints. The analysis showed that not all resource-rich areas are suitable (e.g., those in high-quality protected habitats), while development potential can emerge in areas of medium habitat quality when coupled with high resource endowment and accessibility. This mechanism effectively resolves spatial trade-offs and identifies latent suitable zones often missed by single-dimensional assessments.

Finally, based on the NSSTD and the constraint interactions, this study formulated actionable answers to tourism development plan by proposing differentiated spatial strategies for territorial governance. These include channeling integrated development to southern NSSTD clusters; implementing niche tourism and connectivity enhancement in northern “structural hole” villages; enforcing strict conservation in western high-quality habitats supported by cross-regional ecological compensation; and prioritizing ecological restoration in resource-rich, low-habitat-quality areas. These strategies demonstrate how the framework’s outputs can be operationalized to balance conservation and development.

In summary, the multi-constraint synergistic analysis model proposed in this study has a certain degree of universality, it transcends growth-centric paradigms, repositioning rural tourism as a catalyst for coupled cultural preservation and ecosystem resilience. Its operationalization in territorial spatial planning demonstrates consistency with governmental schemes, particularly in safeguarding Gaoligong’s core habitats while channeling development to southern corridors. Future applications should integrate dynamic land use modeling to enhance adaptive governance across mountainous frontiers. The multi-constraint synergistic analysis model can scientifically reveal the spatial distribution characteristics of rural tourism resources and identify the natural space suitable for tourism development, which not only reveals the characteristics of the territorial system of rural human-land relations, but also provides practical suggestions for the formulation of planning and management strategies for rural tourism resources and the compilation of rural detailed planning and territorial spatial planning.

Author Contributions

D.Z.: Writing—original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Visualization. J.C.: Writing—review and editing, Methodology, Conceptualization. H.L.: Writing—resources, Software, Visualization, Funding acquisition. Y.W.: Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant/Award Number: 52278048); Yunnan Provincial Federation of Social Sciences—Baoshan University Joint Special Project (Grant/Award Number: LHZX2025001; LHZX2025006); Applied Basic Research Program Project of Yunnan Province (Grant/Award Number: 202101BA070001-199) and the Research and Innovation Team Project of Baoshan University (Grant/Award Number: BYTD202302). We are grateful for the invaluable field research support extended by the government of Baoshan City, Yunnan Province.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LJD | Lujiang Dam |

| NSSTD | Natural spatial suitability for tourism development |

| HSSTD | Habitat space suitable for tourism development |

| RS | Remote sensing |

| GIS | Geographic information systems |

| HQ | Habitat Quality |

| HDD | Habitat degradation degree |

| HQI | Habitat quality index |

| CV | Coefficient of Variation |

References

- Jannat, A.; Islam, M.M.; Aruga, K. Revealing the Interrelationship of Economic, Environmental, and Social Factors with Globalization in G-7 Countries Tourism Growth: A CS-ARDL Approach. Sustain. Futures 2025, 9, 100483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Alam, Q. Is Tourism Expansion the Key to Economic Growth in India? An Aggregate-Level Time Series Analysis. Ann. Tour. Res. Empir. Insights 2024, 5, 100126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z. An Empirical Analysis of Tourism Eco-Efficiency in Ecological Protection Priority Areas Based on the DPSIR-SBM Model: A Case Study of the Yellow River Basin, China. Ecol. Inform. 2022, 70, 101720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, F. A New Approach to Sustainable Tourism Development: Moving beyond Environmental Protection. Nat. Resour. Forum 2003, 27, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Fang, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhu, F. Tourism Eco-Efficiency Measurement, Characteristics, and Its Influence Factors in China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Bai, X.; Zhang, D.; Wang, H. Spatiotemporal Characteristics and Multi-Scenario Simulation of Land Use Change and Ecological Security in the Mountainous Areas: Implications for Supporting Sustainable Land Management and Ecological Planning. Sustain. Futures 2024, 8, 100286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.G.; Dietz, T.; Liu, J. Global Relationships between Biodiversity and Nature-Based Tourism in Protected Areas. Ecosyst. Serv. 2018, 34, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehlomakhulu, Z.; Buschke, F.T. Natural and Built Capital as Factors Shaping Tourism in a South African Key Biodiversity Area. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2023, 43, 100670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Xiang, L.; Lin, A.; Hou, Y.; Dai, Y. Exploring the Spatial Configuration of Tourism Resources through Ecosystem Services and Ethnic Minority Villages. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 79, 102426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.W.; Ponsford, I.F. Confronting Tourism’s Environmental Paradox: Transitioning for Sustainable Tourism. Futures 2009, 41, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrado, M.; Sabater, S.; Chaplin-Kramer, B.; Mandle, L.; Ziv, G.; Acuña, V. Model Development for the Assessment of Terrestrial and Aquatic Habitat Quality in Conservation Planning. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 540, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallustio, L.; De Toni, A.; Strollo, A.; Di Febbraro, M.; Gissi, E.; Casella, L.; Geneletti, D.; Munafò, M.; Vizzarri, M.; Marchetti, M. Assessing Habitat Quality in Relation to the Spatial Distribution of Protected Areas in Italy. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 201, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zasada, I.; Häfner, K.; Schaller, L.; Van Zanten, B.T.; Lefebvre, M.; Malak-Rawlikowska, A.; Nikolov, D.; Rodríguez-Entrena, M.; Manrique, R.; Ungaro, F.; et al. A Conceptual Model to Integrate the Regional Context in Landscape Policy, Management and Contribution to Rural Development: Literature Review and European Case Study Evidence. Geoforum 2017, 82, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Wu, Z.; Zheng, W. Impact of Touristification and Landscape Pattern on Habitat Quality in the Longji Rice Terrace Ecosystem, Southern China, Based on Geographically Weighted Regression Models. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 166, 112259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canteiro, M.; Córdova-Tapia, F.; Brazeiro, A. Tourism Impact Assessment: A Tool to Evaluate the Environmental Impacts of Touristic Activities in Natural Protected Areas. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 28, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, S.; Li, Y. Multi-Scenario Simulation Analysis of Land Use Impacts on Habitat Quality in Tianjin Based on the PLUS Model Coupled with the InVEST Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Abudureheman, M.; Halike, A.; Yao, K.; Yao, L.; Tang, H.; Tuheti, B. Temporal and Spatial Variation Analysis of Habitat Quality on the PLUS-InVEST Model for Ebinur Lake Basin, China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 145, 109632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, W.B.; Dersseh, M.G.; Goshu, G.; Abera, W.; Abraham, E.; Mekonnen, M.A.; Fohrer, N.; Tilahun, S.A.; McClain, M.E.; Payne, W.A.; et al. Modeling Changes in Nutrient Retention Ecosystem Service Using the InVEST-NDR Model: A Case Study in the Gumara River of Lake Tana Basin, Ethiopia. Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol. 2025, 25, 776–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liao, L.; Huang, Y.; Fang, Q.; Lan, S.; Chi, M. Conservation Outcome Assessment of Wuyishan Protected Areas Based on InVEST and Propensity Score Matching. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2023, 45, e02516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Angella, F.; Maccioni, S.; De Carlo, M. Exploring Destination Sustainable Development Strategies: Triggers and Levels of Maturity. Sustain. Futures 2025, 9, 100515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mteti, S.H.; Mpambije, C.J.; Manyerere, D.J. Unlocking Cultural Tourism: Local Community Awareness and Perceptions of Cultural Heritage Resources in Katavi Region in Southern Circuit of Tanzania. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2025, 11, 101295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comino, E. Exploring the Environmental Value of Ecosystem Services for a River Basin through a Spatial Multicriteria Analysis. Land Use Policy 2014, 36, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Godil, D.I.; Bibi, M.; Khan, M.K.; Sarwat, S.; Anser, M.K. Caring for the Environment: How Human Capital, Natural Resources, and Economic Growth Interact with Environmental Degradation in Pakistan? A Dynamic ARDL Approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 774, 145553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Song, M.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Z. The Impact of High-Speed Rail Construction on the Development of Resource-Based Cities: A Temporal and Spatial Perspective. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2023, 90, 101742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, M.T.; Hagsten, E. A Threat to the Natural World Heritage Site Rarely Happens Alone. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 360, 121113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhong, L.; Ju, H.; Wang, Y. Land Border Tourism Resources in China: Spatial Patterns and Tourism Management. Sustainability 2019, 11, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, S.; Xia, N.; Gao, X.; Zhao, X.; Liang, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, M. Coupling Coordination Analysis between Railway Transport Accessibility and Tourism Economic Connection during 2010–2019: A Case Study of the Yangtze River Delta. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2024, 55, 101134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Hall, C.M. Does Active Transport Create a Win-Win Situation for Environmental and Human Health? The Moderating Effect of Leisure and Tourism Activity. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 52, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eugenio, F.B.; Rotarou, E.S. Sustainable Development or Eco-Collapse: Lessons for Tourism and Development from Easter Island. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, C.; Hu, T.; Zhang, M.; Ren, X.; Hou, L. Exploration of Roadway Factors and Habitat Quality Using InVEST. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 87, 102551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchiyama, Y.; Kohsaka, R. Cognitive Value of Tourism Resources and Their Relationship with Accessibility: A Case of Noto Region, Japan. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 19, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafeiadis, E.; Elldér, E. Correlates of Perceived Accessibility across Transport Modes and Trip Purposes: Insights from a Swedish Survey. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2024, 186, 104147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czesak, B.; Różycka-Czas, R. Assessing Accessibility and Crowding in Urban Green Spaces: A Comparative Study of Approaches. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2025, 257, 105301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H. Urban Landscape Accessibility Evaluation Model Based on GIS and Spatial Analysis. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 103723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L. Assessing Accessibility to Peri-Urban Parks Considering Supply, Demand, and Traffic Conditions. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2025, 257, 105313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]