Abstract

Investigating the evolution mechanism of overlying strata fractures during mining and identifying the key factors that influence the development height of water-conducting fracture zones (WCFZs) are essential for preventing roof water inrush disasters, protecting mine water resources, and ensuring safe and sustainable mine development. To investigate the height of WCFZs and the evolution law of roof water inflow in a syncline structure working face under high-confined aquifer conditions, the 203 working face of Gaojiapu Coal Mine in Binchang Coalfield is selected as the engineering case. This paper analyzes the characteristics and control mechanisms of roof water inflow in a syncline structure mining area using UDEC 7.0 and COMSOL Multiphysics 6.0 multiphysics numerical simulation software. The results indicate that under different mining heights and advancing speeds, the height of the WCFZ in the overlying strata of a syncline structure working face continuously increases during the downward mining stage and in areas below the axis, and decreases thereafter, eventually stabilizing after reaching its maximum value at the initial stage of upward mining. When the WCFZ communicates with the strong aquifer of the Cretaceous Luohe Formation during the mining process, roof water inflow into the working face increases abruptly. The effectiveness of controlling water inflow by adjusting mining height is superior to that of controlling mining speed. Based on the response relationship between mining height, mining speed, and roof WCFZ, an on-site drainage prevention strategy was implemented involving reduced mining height and increased mining speed. Consequently, the roof water inflow at the working face has decreased from an initial rate of 950 m3/h to 360 m3/h. This study is of great significance for the safe and efficient extraction of coal seams under high-confined aquifers in the Binchang Coalfield, supporting the efficient development of coal resources while safeguarding regional water resources, thereby offering considerable engineering and practical value in promoting green mining and sustainable mining practices in large-scale coal production bases with similar geological conditions.

1. Introduction

The Jurassic coal resources, characterized by abundant reserves, high quality, and significant development potential, provide a crucial foundation for China’s energy security and the sustainable development of the coal industry [1,2,3,4]. With the increasing exploitation of coal resources in this region in recent years, several ultra-large mines with an annual output exceeding 10 million tons have been established [5,6]. During the late Jurassic period, the sedimentary layers underwent uplift and weathering erosion, forming a thick and highly fragmented weathered rock zone at the top of the Jurassic strata. This zone exhibits strong water storage capacity and is predominantly composed of strong aquifers [7,8,9,10]. Due to the shallow burial depth of the Jurassic coal seam and its proximity to the weathered bedrock aquifer, mining-induced fractures often connect the coal seam to the overlying aquifers [11]. Consequently, coal mines exploiting Jurassic coal resources generally face serious water hazard risks [12]. For instance, roof water inflow reached over 1100 m3/h during the extraction of the No. 21302 working face at Cuimu Coal Mine in Shaanxi Province [13]. If such intense roof water inflow is not promptly discharged, the working face may be rapidly flooded, resulting in mining interruptions and equipment abandonment, severely impeding mine sustainability [14,15]. Therefore, preventing roof water inrush and coordinating groundwater resource protection are essential for the sustainable development of mining operations.

As one of the major coal production bases in China, the Binchang Coalfield in Shaanxi Province is characterized by complex geological conditions, with most coal seams influenced by synclinal structures and a thick, highly permeable aquifer overlying the coal seams [16,17,18,19]. Regarding the roof water inrush problem in Jurassic coal seams, domestic and international scholars have primarily focused on classifying water inrush types and investigating the development laws of water-conducting fracture zones (WCFZs). Dong et al. classified the roof water inrush types in the Jurassic coalfields of the Ordos Basin into four categories: interlayer water inrush, thin bedrock water bursting with sand or mud inrush, thick sandstone water inrush, and weathered rock water inrush [20,21]. Xue et al. analyzed the roof water-infilling modes in the Jurassic coalfields of the Ordos Basin and proposed a qualitative classification of hydrogeological structural types [22]. Zhao et al. examined the characteristics of sandstone water inrush in Jurassic coal seams and proposed prevention and control technologies such as grouting sealing and dewatering depressurization [23]. Wang et al. investigated the water inrush behavior of sandstone aquifers in the roof of the Jurassic Xishanyao Formation coal seam and developed a roof sandstone water release control technique applicable under closed hydrogeological conditions [24]. Some researchers have derived empirical formulas for estimating the height of WCFZs under fully mechanized mining conditions through statistical analysis of extensive field measurement data [25,26,27,28]. Li et al. established predictive empirical formulas for the height of roof WCFZs by analyzing measured data from the Huanglong Coalfield, considering the combined influence of working face width and coal seam mining height [29,30]. Ivan, S. et al. proposed an algorithm for assessing aquifer water inrush risk based on ANSYS 17.2 simulations in a complex anticline bedding structure [31,32]. Although the mechanisms of water inrush in conventional, relatively flat-lying or monoclinic strata have been extensively studied [33,34,35], research specifically addressing the unique hydrogeological challenges in synclinal structural zones remains limited. Existing studies have mainly emphasized the role of synclinal axes as potential groundwater migration pathways or as water-saturated zones caused by localized stress concentration; however, a comprehensive understanding of the dynamic processes of water inrush under complex structural conditions is still lacking.

Regarding the accurate prediction of mine water inflow and evaluation indicators for water inrush, Li et al. proposed a spatiotemporal dynamic prediction method for the release of static storage and dynamic replenishment of water in the roof aquifer during the mining process of Jurassic coal seams, which improved the prediction accuracy of water inflow from pore-fissure sandstone aquifers in the Jurassic coalfield [36]. Chen et al. investigated the correlation between roof water inflow at the working face and aquifer lithology, thickness, and groundwater flow field, and analyzed the influence mechanisms of mining factors on water inflow during mining [37]. Wang et al. applied the principle of equilibrium to analyze the components of mine inflow during water inrush events and developed evaluation indicators for the appropriate degree of mine drainage and pressure reduction [38]. Cui et al. examined the effects of different coal recovery ratios and advancement speeds on water inflow at fully mechanized caving faces and proposed a water control strategy integrating pre-drainage and restricted mining parameters [39]. Jin et al. introduced the concept of “wedging ratio,” defined as the ratio of the thickness of the WCFZ extending upward from the coal seam to the Luohe Formation sandstone, relative to the total thickness of the Luohe Formation, and proposed this ratio as a key control index for water-reduction mining [40]. The above studies demonstrate that scholars have conducted in-depth research on roof water hazards in Jurassic coal seams. However, there are relatively few investigations into the development laws of WCFZs and water inflow prediction under extremely complex geological conditions—such as those involving synclinal structures. Furthermore, research on the control mechanisms and effective mitigation measures for strong water inflow in syncline-structured working faces remains insufficiently comprehensive.

Hence, based on the hydrogeological conditions of the working face in the syncline structure area of Gaojiapu Coal Mine in the Binchang Mining Area, this study conducts the following three research tasks: (1) Analyzing the development regularity of the WCFZ in the roof and the water inrush characteristics at different mining stages of the 204 working face in the syncline structure area through numerical simulation; (2) Investigating the sensitivity of coal seam dip angle, mining height, and mining speed to the development height of the WCFZ and roof water inflow using the controlled-variable method; (3) Proposing the control mechanism and control measures for strong roof water inflow. By comprehensively analyzing the influence of mining height and speed on water inflow volume at the working face, a source-based prevention and control mechanism—achieved by rationally selecting mining height and speed—is proposed. This study is of significant importance for the efficient extraction and sustainable development of extra-thick coal seams located beneath thick and highly permeable aquifers in synclinal structural zones.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Research Area

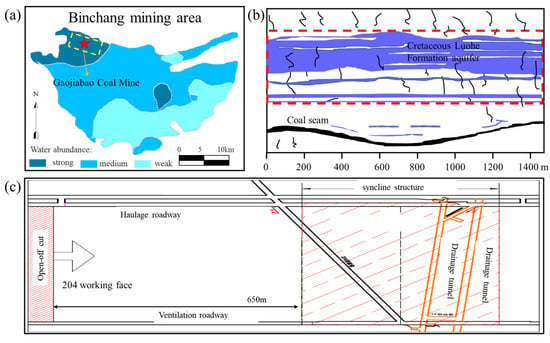

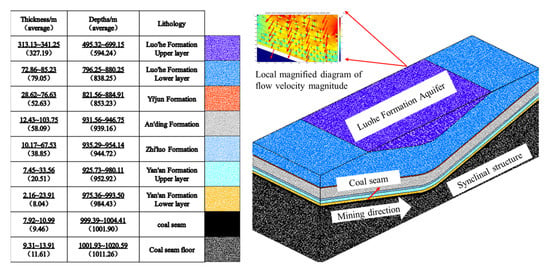

Gaojiapu Coal Mine is located in the northwest of the Binchang Mining Area, where the surface predominantly features ridge and tableland landforms, with the northern and eastern margins adjacent to the Jinghe River valley. The mine has a designed annual production capacity of 5 million tons, and the primary coal seam targeted for extraction is the No. 4 coal seam of the Middle Jurassic Yan’an Formation, which has an average thickness of 9.7 m. Overlying this seam is a thick confined aquifer within the Cretaceous Luohe Formation, reaching a maximum thickness of 580 m. The upper section of the Luohe Formation consists of thick, coarse-grained sandstone, with an average porosity of 15.44% and a permeability coefficient ranging from 0.2 to 1.55 m/day. This aquifer is highly water-rich, exhibits substantial water yield, and is characterized by pore pressure of up to 7.0 MPa. As shown in Figure 1, the 204 working face has a length of 200 m and an average coal seam thickness of approximately 10.6 m. It employs the fully mechanized longwall caving method, with a shearer cutting height of 3.75 m and a caved coal height of about 6 m. During mining operations, roof strata are managed through natural caving. Water inflow from the working face is discharged by gravity into the sump at the bottom of the shaft. A synclinal structure exists along its strike, with the syncline axis located 650 m from the initial mining open-off cut. As the working face advances, it sequentially undergoes distinct mining phases: downward-dipping mining and upward-dipping mining. The dip angles of the synclinal structures are uniformly 17°.

Figure 1.

Brief introduction of study area: (a) The water enrichment of Luohe Formation in Gaojiapu Coal Mine; (b) Spatial relationship between coal seam and aquifer; (c) Layout plan of roadway in 204 working face.

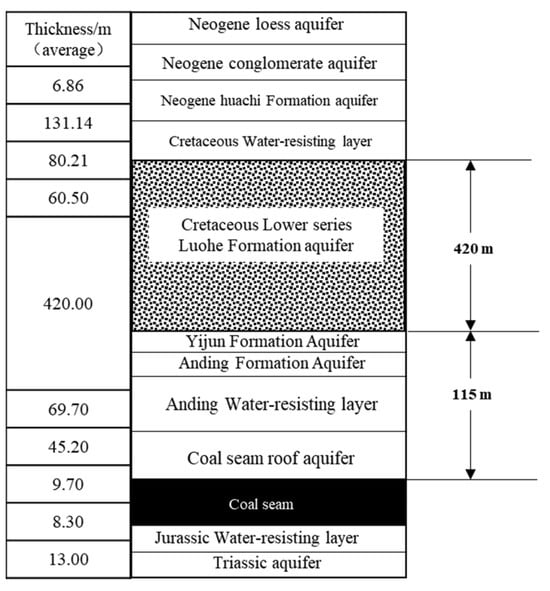

Figure 2 illustrates a borehole log for the 204 working face. During the mining process of the 204 working face, the primary water-bearing source in the roof is the sandstone aquifer within the Lower Cretaceous Luohe Formation, with a thickness ranging from approximately 320 to 420 m. The vertical distance between the coal seam and this aquifer is approximately 115 m. When the working face mining reaches approximately 400 m, the maximum roof water inflow exceeds 1100 m3/h, significantly disrupting normal mining operations at the working face.

Figure 2.

Composite column of 204 working face.

2.2. Model Establishment and Simulation Scheme Design

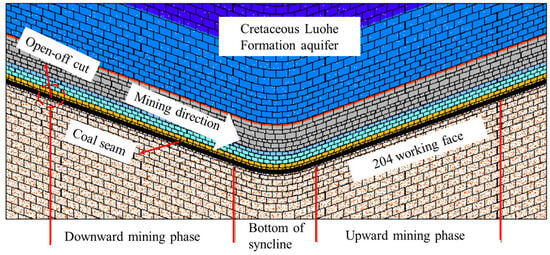

In order to analyze the development characteristics of the plastic zone and the WCFZ in the roof of the 204 working face within the syncline structural zone, a UDEC discrete element numerical model was established based on the stratigraphic profile actually exposed by the borehole at the 204 working face. The model had a strike length of 1500 m and a vertical height of 590 m. To minimize the influence of boundary effects on the simulation results, 100 m protective coal pillars were set on both sides of the model. According to the actual occurrence conditions of the coal seam, the dip angle was set at 17° for both the downward-dipping and upward-dipping mining stages, and the coal seam thickness was defined as 10 m, as shown in Figure 3. The physical and mechanical parameters of each stratum were assigned based on laboratory test results (Table 1). The contact properties between rock blocks were defined by reducing the cohesion and tensile strength of the intact rock by a factor of 0.7, while the internal friction angle was retained at the laboratory-measured value.

Figure 3.

Numerical model of coal working face in syncline area.

Table 1.

Physical and mechanical parameters of main rock strata in numerical model.

In numerical modeling, the failure and instability of rock masses are determined by applying the Mohr-Coulomb yield criterion, as described by the following strength criterion equation. Under typical stress conditions, the tensile strength of rock masses is inherently low, and tensile failure is evaluated using the tensile strength criterion:

where σ1 and σ3 represent the maximum and minimum principal stresses, respectively, MPa; σt denotes the tensile strength, MPa; c signifies the cohesion, MPa; and φ represents the angle of internal friction. Shear failure occurs when fs < 0, tensile failure occurs when ft < 0, and the material remains intact when fs > 0 and ft > 0.

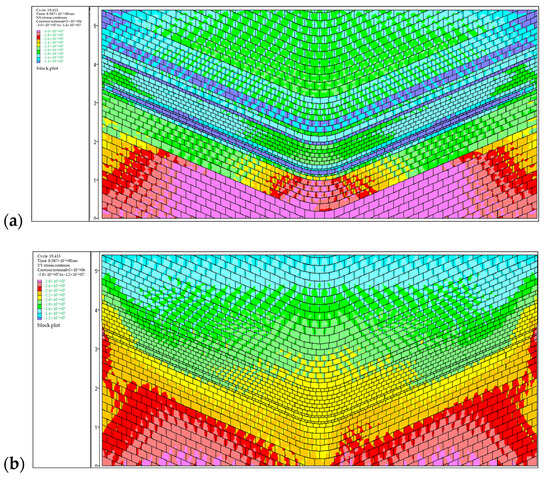

The measured in situ stress data from existing synclinal structural regions reveal distinct characteristics of stress distribution. In the synclinal limbs, both vertical and horizontal stresses show little variation, with minimal stress intensification observed. In contrast, along the synclinal axis, the vertical stress remains relatively constant and increases primarily with burial depth, whereas the horizontal stress exhibits significant concentration and amplification due to tectonic effects, superimposed on the gravitational stress component. The numerical model stress was applied in two steps. First, the self-weight stress field was simulated, the vertical displacement of the lower boundary of the model was fixed, the left and right boundaries were fixed, and the upper boundary was free. The equivalent gravity load was applied on the upper boundary according to the burial depth, and the overburden density was taken as 2.5 g/cm3 with an equivalent load of 12.5 MPa. Next, the increased horizontal stress affected by the tectonic stress was simulated, the left and right fixed boundaries were released, and the horizontal compressive stress increasing with the burial depth gradient was applied to the left and right boundaries according to the size of 12 MPa at the top and 30 MPa at the bottom of the model.

After the model calculation reached equilibrium, the vertical and horizontal stress distributions are shown in Figure 4. The results indicate that, in addition to increasing with depth, both the horizontal and vertical stresses exhibit a certain degree of vertical stress concentration in the axial area, which is approximately arc-shaped and symmetrical. This is similar to the existing research conclusions on the stress distribution patterns in syncline structural areas [4,11].

Figure 4.

Initial in situ stress distribution in the syncline structural area before mining: (a) Horizontal stress distribution diagram; (b) Vertical stress distribution diagram.

3. Results

3.1. Development Law of Roof Plastic Zone and WCFZ

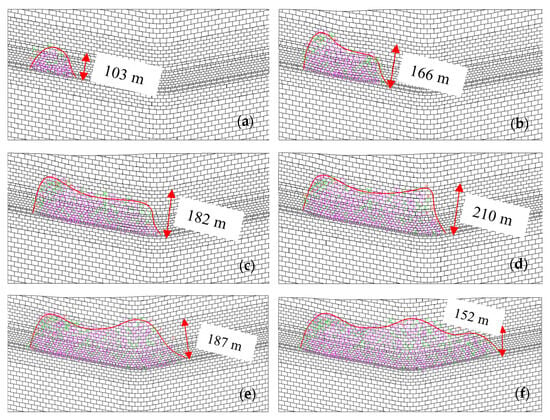

The mining speed of the 204 working face on site is approximately 3 m/d. Figure 5 and Figure 6 show the development characteristics of the roof plastic zone and WCFZ during the mining process. It can be observed that from the open-off cut position to the bottom of the syncline axis, the maximum development height of the WCFZ increased from 103 m to 182 m (see Figure 5a–c). This indicates that a continuous water inflow pathway is established and persists between the coal seam roof and the Luohe Formation aquifer once the working face advances beyond 350 m, as the WCFZ height exceeds the protective layer thickness 115 m. After the working face passes through the bottom of the syncline axis into the upward-dipping mining stage, the maximum development height of the WCFZ exhibits an initial increase followed by a gradual decrease. Specifically, when the working face has advanced 650 m from the cutting opening, the WCFZ reaches its maximum height of 210 m (see Figure 5d). Subsequently, with increasing advancing distance, the WCFZ height gradually decreases and stabilizes at approximately 150 m. Field measurements indicated that when the working face reached the syncline axis area (approximately 650 m), the maximum height of the WCFZ was approximately 205 m. This measured value is in close agreement with the simulated result of 210 m at the same location, yielding a relative error of less than 2.5%. Overall, during the downward-dipping mining phase, the maximum height of WCFZ development increases progressively with advancing distance and reaches its peak near the syncline axis area. This suggests higher stress concentration in this region, leading to more intense fracturing and failure of the overlying strata. Upon transitioning into the upward-dipping mining phase, the WCFZ height gradually decreases and eventually stabilizes. This reduction is attributed to the compaction of mining-induced fractures under stress concentration caused by the load from fractured overburden strata. These findings indicate that a continuous water inflow pathway persisted between the coal seam roof and the Luohe Formation aquifer throughout the entire face withdrawal process, resulting in sustained exposure of mining operations to significant roof water inflow over the whole withdrawal period.

Figure 5.

The variation law of the WCFZ with mining distance: (a) 150 m; (b) 350 m; (c) 550 m; (d) 650 m; (e) 800 m; (f) 1000 m. Note: The colored section represents the failure state in the UDEC model, where magenta indicates shear failure and green indicates tensile failure.

Figure 6.

Variation in development height of WCFZ.

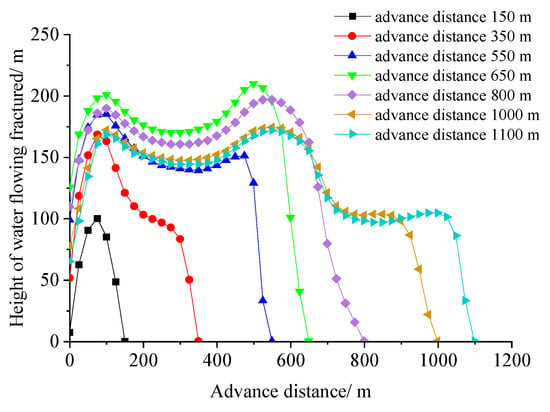

3.2. Analysis of the Characteristics of Roof Water Inflow During the Mining Period

To investigate the variation pattern of roof water inflow characteristics during the mining process, this paper establishes a COMSOL numerical model. Mining-induced fractures simulated using UDEC are imported into the COMSOL model, and the groundwater flow field is appropriately simplified. The coupling between mechanical deformation (UDEC) and fluid flow (COMSOL) was implemented as a one-way sequential scheme. The geometry and distribution of the plastic zones and fractures from each UDEC mining step were statically imported into COMSOL. In these zones, the permeability was dramatically increased by several orders of magnitude to represent the open WCFZ. The permeability of the intact rock matrix remained unchanged. Lateral boundaries are set at 125 m on both sides to minimize boundary effects. The upper boundary is defined by the maximum development height of the WCFZ, with a 200 m buffer above it, as this study focuses primarily on roof water inflow. The lower boundary is set at the lowest contour of the coal seam floor, with a minimum thickness of 50 m to ensure modeling accuracy. To reduce computational cost, the three-dimensional model is simplified into a two-dimensional representation along the dip direction of the working face. The total water inflow for the 3D working face is then estimated by integrating the water inflow along the goaf boundary in the inclined cross-section over the full inclined length. The model configuration is illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Hydrogeological model of working face 204. Note: Surface: Darcy velocity magnitude (m/s); Surface arrow vectors: Darcy velocity field.

Groundwater flow was simulated based on Darcy’s law, which is appropriate for laminar flow in porous media. The model assumes a constant water density (ρ) of 1000 kg/m3 and a dynamic viscosity (μ) of 0.001 Pa·s. The permeability field is treated as anisotropic, with horizontal permeability (k~x~) typically set at 5 to 10 times the vertical permeability (k~y~) to reflect sedimentary bedding characteristics, except those that were overridden by imported, highly permeable mining-induced fractures. The pore water pressure in the Luohe Formation aquifer can reach up to 7.0 MPa. Based on the aquifer’s depth and regional hydrogeological conditions, the piezometric elevation is approximately +750 m. Consequently, the pressure head applied to the upper boundary of the COMSOL model, corresponding to the base of the Luohe Formation aquifer, was set within the range of 5.5–6.5 MPa to account for the hydraulic gradient. Regarding the aquifer regime, the Luohe Formation constitutes a deep, thick confined aquifer with substantial storage capacity. Due to its considerable depth (exceeding 800 m) and isolation from short-term surface influences, its water level remains stable with negligible seasonal fluctuations. Therefore, a steady-state flow model was adopted, representing an appropriate simplification for this hydrogeological context. The hydrogeological parameter table utilized in the COMSOL numerical simulation model as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Hydrogeological parameters of numerical calculation model.

Figure 8 presents the Darcy velocity nephogram of the groundwater flow field around the 204 working face at different advancing distances, indicating that when the working face has advanced to 150 m, the WCFZ has not yet connected with the aquifer in the Luohe Formation. At this stage, roof water inflow primarily originates from the sandstone aquifers immediately above the coal seam. The highest water inflow occurs near the open-off cut, while the Darcy velocity and contribution to total inflow in the central goaf region are minimal. This is attributed to the fact that, as mining progresses, the static water reserves in the overlying roof aquifer within the central goaf have been largely depleted, and lateral recharge flows preferentially into the working face through the caved zones at both ends, leaving little or no replenishment to reach the middle of the goaf.

Figure 8.

Characteristics of water inflow in the stage of mining: (a) 150 m; (b) 350 m; (c) 550 m; (d) 650 m; (e) 800 m; (f)1000 m.

The total roof water inflow Q is calculated by line integration along the goaf roof and the front and rear abutments in the strike direction, as given in Equation (1).

where q = 0.3 kg/(m2·s), the working face length L is 200 m, h is the conversion ratio of hour to second, and M is the mass of a cubic meter of water.

When mining reached 350 m, the mining-induced fractures had extended into the aquifer of the Luohe Formation. At this stage, the roof water inflow consisted of both water from the immediate roof sandstone and water from the sandstone aquifer in the Luohe Formation. By performing line integration of the flow flux at each point along the goaf roof and abutments up to the 350 m mining position, the total water inflow into the working face was calculated as 446 m3/h. Similarly, the water inflow values were determined to be 960 m3/h, 1120 m3/h, 1065 m3/h, and 830 m3/h at advancing distances of 550 m, 650 m, 800 m, and 1000 m, respectively. Based on the comprehensive numerical simulation results, it is evident that the roof water inflow volume in the syncline structural area reaches its maximum near the axis trough. As mining advances upward, the roof fractures gradually close, and water inflow stabilizes.

4. Discussion

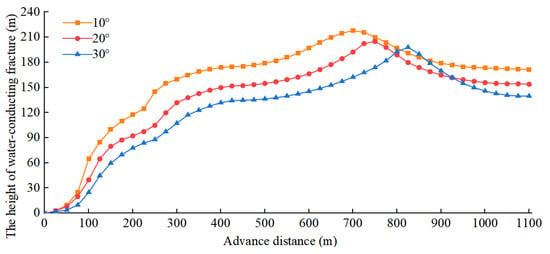

4.1. Relationship Between WCFZ and Syncline Structural Angles

Using the UDEC model established in Section 2.2, the influence of different syncline structural angles on the development of the WCFZ in the working face was investigated. In the simulation setup, the mining height was set at 10 m and the mining speed maintained at a constant 3 m/d, with syncline structural angles defined as 10°, 20°, and 30°, respectively. The response relationship between the development height of the WCFZ and the syncline structural inclination throughout the entire mining process is illustrated in Figure 9, revealing a negative correlation between the two variables. During the downward-dipping mining phase, the maximum development height of the WCFZ decreases as the syncline structural inclination increases, with corresponding values of 175 m, 152 m, and 135 m under the three inclination conditions. Upon entering the axis trough region, the growth rate of the WCFZ slows down and gradually stabilizes. At the onset of upward-dipping mining, the maximum development height under the 30° inclination condition is slightly higher than that under the other two conditions, after which it progressively declines. By the end of the recovery process, the final heights of the WCFZ are 172 m, 154 m, and 140 m for the respective inclination scenarios.

Figure 9.

Variation in development height of WCFZ with dip angle during the whole mining process of syncline structure.

The radius of curvature at the syncline axis is a key parameter governing stress concentration. A smaller radius (i.e., a tighter fold) typically leads to higher stress concentration, which may result in more intense fracturing and an increased development height of the WCFZ for a given dip angle, thereby amplifying sensitivity to structural variations. In contrast, a larger radius (i.e., a gentler fold) promotes more uniform stress distribution, potentially reducing the influence of dip angle changes. Moreover, an asymmetric syncline disrupts the stress symmetry present in the model. The steeper limb is likely to undergo more pronounced shear failure during its respective mining phase, potentially leading to asymmetrical WCFZ development and a more complex spatial pattern of water inflow along the strike of the working face. This study establishes the fundamental relationship between dip angle and WCFZ height under symmetric structural conditions. Future work will incorporate variable axial curvature, structural asymmetry, and more heterogeneous lithological sequences to develop a more comprehensive predictive modeling framework.

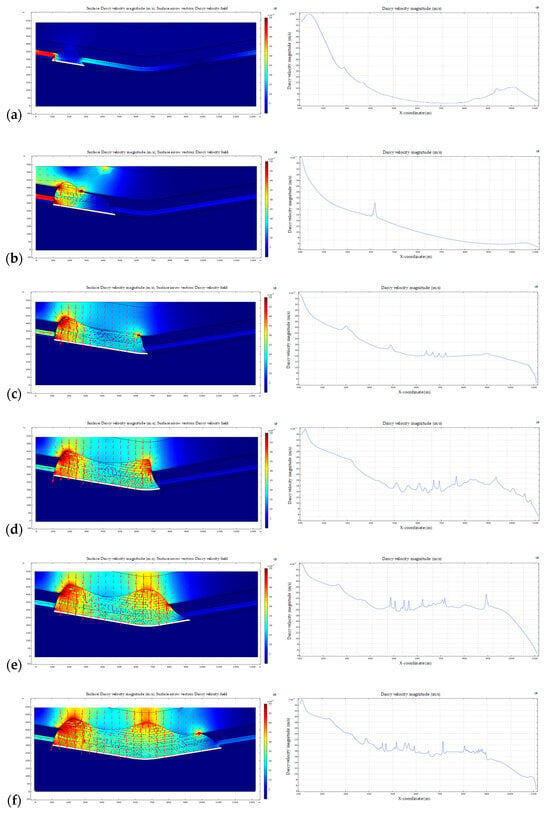

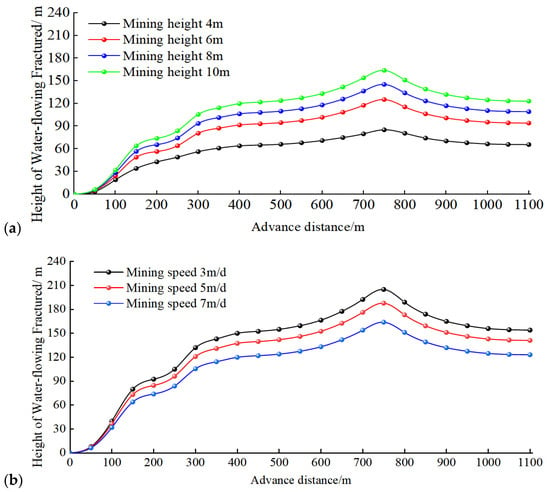

4.2. The Impact of Mining Height and Speed on Roof Water Inrush Characteristics

In order to analyze the influence law of mining height and mining speed on the roof water inflow, using the numerical model established in the previous section, this section studied the variation characteristics of water inflow of the working face in syncline structure area under the conditions of mining height of 4 m, 6 m, 8 m, 10 m and mining speed of 3 m/d, 5 m/d, 7 m/d, respectively. Figure 10a shows the variation curve of the development height of the WCFZ and roof water inflow with the mining height at the mining speed of 3 m/d. It can be seen that the maximum development height of the WCFZ increased with the mining height growth, which was 98 m, 144 m, 176 m and 210 m. Figure 10b shows the variation curve of the development height of the WCFZ and the roof water inflow with the mining speed of the working face when the mining height was 10 m. It can be seen that the maximum development height of the WCFZ decreased with the mining speed increase, which was 210 m, 188 m and 164 m in turn.

Figure 10.

Variation in WCFZ: (a) Mining height; (b) Mining speed.

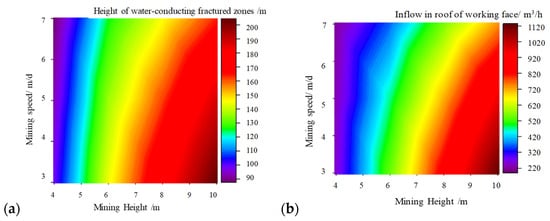

Figure 11 presents the vector diagram illustrating the development height of the WCFZ and the variation in working face water inflow under different mining heights and mining speeds. It is evident that the influence of these two parameters on both fracture development and water inflow is more pronounced for mining height than for mining speed. Reducing the mining height effectively suppresses the vertical extension of the WCFZ, but has a relatively limited effect on reducing water inflow. To quantitatively assess the regulatory influence of mining parameters, a reduction in mining height from 10 m to 4 m (a 6 m decrease) resulted in a 112 m reduction in fracture height, whereas an increase in mining speed from 3 m/d to 7 m/d (a 4 m/d increase) led to a 46 m reduction. The normalized sensitivity, defined as the change in fracture height per unit change in parameter, was approximately 18.7 m/m for mining height and 11.5 m/m for mining speed. This quantitative analysis indicates that mining height exerts a significantly greater influence on the development of the WCFZ than mining speed, thereby providing a robust scientific basis for prioritizing mitigation strategies. This can be attributed to the presence of the Anding Formation aquiclude in the overlying strata, whose effectiveness in blocking water flow varies with mining conditions. When the reduced fracture height falls within the low-permeability Anding Formation aquiclude, it contributes little to the reduction in working face water inflow. Significant reductions in water inflow are primarily achieved when the fracture zone’s development is restricted within the highly permeable Luohe Formation aquifer.

Figure 11.

Variation by mining speed and mining height: (a) the height of WCFZ; (b) Inflow in roof of working face.

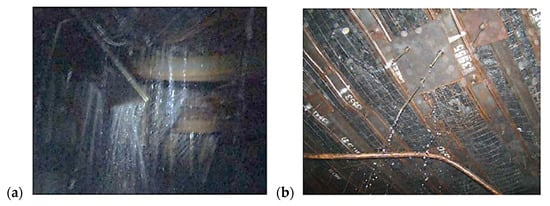

4.3. Guiding Significance for the in Site Production

To ensure that the observed reduction in water inflow can be unequivocally attributed to variations in mining height and speed, it was verified that no other significant changes occurred in the mining system during the implementation period. Specifically, the ventilation regime, the capacity and operation of the underground drainage system, the support design (lining), and grouting practices remained unchanged. This well-controlled setting enables a direct correlation between the reduction in water inflow and the modified mining parameters. As shown in Section 4.2, the development height of the WCFZ in the syncline structural area gradually decreases with decreasing mining height and increasing mining speed. However, in practical operations, reducing mining height significantly compromises the coal resource recovery rate. Reducing the mining height from 10 m to 8 m, while highly effective in controlling the WCFZ and minimizing water inflow, inevitably results in the loss of recoverable coal resources and thus reduces the overall recovery rate. In this case, the imperative to prevent a catastrophic water inrush, protect the regional aquifer, and ensure workforce safety. Increasing mining speed offers a partial mitigation of this trade-off by helping maintain production rates and economic viability while simultaneously reducing water inflow. Therefore, mining speed should be rationally controlled according to site-specific conditions to effectively manage roof water inflow while maintaining production efficiency. When mining at the 204 working face of Gaojiapu Coal Mine approaches the vicinity of the syncline axis, a significant increase in roof water inflow is expected. To address this issue, on-site adjustments were made to the mining height and advance speed: the mining height was reduced from 10 m to 8 m, and the advance speed was increased from 3 m/d to 5 m/d, the water inflow from the roof of the working face has decreased from an initial 950 m3/h to 360 m3/h. As can be seen from Figure 12, the roof water inflow condition has been significantly alleviated.

Figure 12.

In site roof water inflow pictures: (a) original; (b) after implementing control measures.

It is important to emphasize that the influence patterns of coal seam dip angle, mining speed, and mining height on the development height of WCFZ in the coal mining working face, as obtained in this study, are derived from specific geological conditions—namely, synclinal structural zones with dip angles of 10°, 20°, and 30°, coal seam burial depths ranging from 800 to 1000 m, and coal seam thicknesses of 4~10 m. Our findings reveal the fundamental relationships among various factors influencing the development height of WCFZ within this specific engineering context. When applying these results to geological settings beyond the specified conditions, appropriate adjustments and model validations are required to ensure reliability.

5. Conclusions

This paper systematically investigates the development mechanism of the WCFZ in the roof and the characteristics of water inrush at the working face during coal seam mining within syncline structural areas underlain by strong, water-rich aquifers. It examines the influence of mining height and mining speed on both the height of the WCFZ and the magnitude of water inflow. The main research conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- During coal mining in the syncline structural area, the development height of the WCFZ increases with advancing distance in the downward-dipping mining phase. The maximum development height is reached near the axis trough, exceeding 210 m. Upon entering the upward-dipping mining phase, the development height gradually decreases and eventually stabilizes.

- (2)

- As the inclination of the syncline structure increases, the development height of the WCFZ gradually decreases, while the advancing distance required to reach its maximum value increases progressively. With decreasing mining height, the development height of the WCFZ decreases progressively, and this reduction becomes more pronounced; reducing the mining height from 10 m to 4 m decreases the maximum WCFZ height from 210 m to 98 m. As mining speed increases, the development height of the WCFZ also gradually decreases, reducing the maximum height from 210 m to 164 m. Through comparative analysis of these variation patterns, it is found that reducing mining height is more effective in controlling the development height of the WCFZ.

- (3)

- Based on the response relationship between mining height, mining speed, and roof WCFZ development, the field application of reducing mining height from 10 m to 8 m and increasing advance speed from 3 m/d to 5 m/d successfully reduced roof water inflow from 950 m3/h to 360 m3/h. The research findings can serve as a basis for guiding the design of mining parameters in extra-thick coal seams underlain by thick and strong aquifers in syncline structural areas. Furthermore, these findings can also inform the prevention and control of roof water hazards and support sustainable mining practices in large-scale coal production bases with similar geological conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.L.; methodology, G.F.; software, S.Z.; validation, Z.K. and L.Z.; formal analysis, S.L.; investigation, T.L. and S.Z.; resources, G.F.; data curation, T.L.; writing—original draft preparation, T.L.; writing—review and editing, T.L. and G.F.; visualization, S.Z.; supervision, Z.W.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, grant number 2025QN1009, the National Key Research and Development Program of China, grant number 2024YFC3909304, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 52574177, 52204161.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We also thank Huining Ni, Shijie Hua, Ruiliang Shen and Yibo Fan for their fruitful discussions about this work. Special thanks to the anonymous reviewers and the editors for their insightful comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Niu, C.; Tian, Q.; Xue, L.; Zhang, R.; Xu, D.; Luo, S. Principal Causes of Water Damage in Mining Roofs under Giant Thick Topsoil–lilou Coal Mine. Appl. Water Sci. 2024, 14, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; Meng, X.; Li, L.; Han, Y. A Prediction Model of Coal Seam Roof Water Abundance Based on PSO-GA-BP Neural Network. Water 2023, 15, 4117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wu, C.; Yao, Q.; Li, X.; Chen, S.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Zhu, G. Instability Mechanism and Control Method of Surrounding Rock of Water-Rich Roadway Roof. Minerals 2022, 12, 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Gao, Y.; Yang, T.; Zhang, P.; Zhao, Y.; Deng, W.; Liu, H.; Liu, F. Integrated simulation and monitoring to analyze failure mechanism of the anti-dip layered slope with soft and hard rock interbedding. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2023, 33, 1147–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, T.; Deng, W.; Du, S.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, H.; Wang, H.; Guo, J.; Liu, L. Evaluating failure mechanisms of excavation-induced large-scale landslides in Xinjing open-pit coal mine through integrated UAV imagery and 3D simulation. Landslides 2025, 22, 2021–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Fang, X.; Liang, M.; Wu, G.; Chen, N.; Song, Y. Analysis and Application of Dual-Control Single-Exponential Water Inrush Prediction Mechanism for Excavation Roadways Based on Peridynamics. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, Q.; He, M.; Li, S.; Gao, Y. Study on Strike Failure Characteristics of Floor in a New Type of Pillarless Gob-side Entry Retaining Technology Above Confined Water. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2025, 161, 106596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Xu, G.; Li, H.; Su, D.; Liu, Y. Bed Separation Formation Mechanism and Water Inrush Evaluation in Coal Seam Mining under a Karst Cave Landform. Processes 2023, 11, 3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, L.; Li, H. Finite–Discrete Element Method Simulation Study on Development of Water-Conducting Fractures in Fault-Bearing Roof under Repeated Mining of Extra-Thick Coal Seams. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Jiang, Y.; Ren, Q. Roof Hydraulic Fracturing for Preventing Floor Water Inrush under Multi Aquifers and Mining Disturbance: A Case Study. Energies 2022, 15, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, L. Study on Fracture Evolution and Water-Conducting Fracture Zone Height beneath the Sandstone Fissure Confined Aquifer. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, W.; Yang, Z.; Gu, T.; Wang, Z. Predicting the Height of the Water-Conducting Fractured Zone in Fully Mechanized Top Coal Caving Longwall Mining of Very Thick Jurassic Coal Seams in Western China Based on the NNBR Model. Mine Water Environ. 2023, 42, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, G.; Qiu, M.; Shi, L. Tectonic controls on the development of water-conducting fracture zones in the North China Block. Measurement 2025, 246, 116726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Bian, K.; Wang, T.; Jin, Z.; Liu, B.; Sun, H.; Chang, J. Risk Assessment and Water Inrush Mechanism Study of Through-Type Fault Zone Based on Grey Correlation Degree. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Q.; Guo, R.; Xu, Y. Minimizing the Damage of Underground Coal Mining to a Village Through Integrating Room-and-Pillar Method with Backfilling: A Case Study in Weibei Coalfield, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Zhang, C.; He, X.; Wang, X.; Qiao, Y. DEM Fluid–solid Coupling Method for Progressive Failure Simulation of Roadways in a Fault Structure Area with Water-rich Roofs. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour. 2022, 8, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, K.; Tu, S.; Li, W.; Li, J.; Tian, J.; Zhao, H.; Ma, J. Effects of Lithology Combination Compaction Seepage Characteristics on Groundwater Prevention and Control in Shallow Coal Seam Group Mining. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Ma, L.; Zhang, D. Characteristics of Roof Ground Subsidence While Applying a Continuous Excavation Continuous Backfill Method in Longwall Mining. Energies 2020, 13, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, B.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, L.; Ma, Z. Physical and Numerical Investigations of Target Stratum Selection for Ground Hydraulic Fracturing of Multiple Hard Roofs. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2024, 5, 699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Ji, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhao, B.; Cao, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ji, Z.; Liu, B. Prevention and Control Technology and Application of Roof Water Disaster in Jurassic Coal Field of Ordos Basin. J. China Coal Soc. 2020, 45, 2367–2375. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, S.; Wang, H.; Guo, X.; Zhou, Z. Characteristics of Water Hazards in China’s Coal Mines: A Review. Mine Water Environ. 2021, 40, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Wang, H.; Zhao, C.; Yang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Li, D. Prediction of the Height of Water-conducting Fracture Zone and Water-filling Model of Roof Aquifer in Jurassic Coalfield in Ordos Basin. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 2020, 37, 1222–1230. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, B.; Lv, Y. Research on Characteristics and Prevention and Control Technology of Sandstone Water Disaster in Coal Seam Floor in Jurassic Coalfield. China Coal 2021, 47, 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, G.; Kong, D.; Xiong, Y. Characteristics of Rock Strength Failure and Identification of Hazardous Areas in the Roof of Deep Mining Stope. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 167, 109027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Deng, J.; Yang, T.; Zhang, J.; Lin, H.; Liu, H.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Y. Research on Disaster Prevention and Control Technology for Directional Hydraulic Fracturing and Roof Plate Unloading. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Fan, G.; Zhang, D.; Luo, T.; Han, X.; Xu, G.; Tong, H. Mechanism of Burial Depth Effect on Recovery Under Different Coupling Models: Response and Simplification. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Yin, S.; Wang, X.; Li, S.; Li, Q.; Di, Y. Degradation and Migration Characteristics and Water-Inrush Mechanism of Overburden Roof Under High-Intensity Mining. Energy Sci. Eng. 2025, 4, 1896–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Park, W.; Cha, G.; Hong, W. Quantifying Asbestos Fibers in Post-disaster Situations: Preventive Strategies for Damage Control. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 48, 101563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Hu, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, L. Comprehensive Detection Technique for Coal Seam Roof Water Flowing Fractured Zone Height. Coal Geol. Explor. 2018, 46, 101–107. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C. Characteristics of Height of Water Flowing Fractured Zone Caused during Fully–mechanized Caving Mining in Huanglong Coalfield. Coal Geol. Explor. 2019, 47, 129–136. [Google Scholar]

- Sakhno, I.; Zuievska, N.; Li, X.; Zuievskyi, Y.; Sakhno, S.; Semchuk, R. Prediction of water inrush hazard in fully mechanized coal seams’ mining under aquifers by numerical simulation in ANSYS software. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakhno, I.; Sakhno, S.; Vovna, O. Surface Subsidence Response to Safety Pillar Width Between Reactor Cavities in the Underground Gasification of Thin Coal Seams. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Spatial Distribution of Strain Energy Changes Due to Mining-induced Fault Coseismic Slip: Insights from a Rockburst at the Yuejin Coal Mine, China. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2025, 58, 1693–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Gao, X. Fault slip amplification mechanisms in deep mining due to heterogeneous geological layers. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 169, 109155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Ma, K.; Chen, J.; Xue, Y.; Wang, Z.; Cui, B. Mechanical Model on Water Inrush Assessment Related to Deep Mining Above Multiple Aquifers. Mine Water Environ. 2019, 38, 827–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ji, D.; Han, P.; Li, Q.; Zhao, H.; He, F. Study of Water-conducting Fractured Zone Development Law and Assessment Method in Longwall Mining of Shallow Coal Seam. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xu, Z.; Cen, G. Hydrogeological Characteristics and Water Hazard Control in the New Auxiliary Wellbore of Zhangshuanglou Dry mine. Coal Sci. Technol. Mag. 2006, 4, 40–42. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Yin, S.; Lian, H.; Cao, M.; Hou, E.; Xia, X.; Yi, S.; Yan, T.; Li, Q.; Wang, H. Softening and Instability Evolution of Strip Coal Pillar under Water Immersion in Goaf. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 29478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z. First Application of Top Coal Caving Method in Coal Mine with Soft sandy Strata and Enriched Aquifer. Coal Min. Technol. 2018, 23, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, D.; Liu, Y.; Wang, T. Water–reducing Mining Technology for Fully Mechanized Top–coal Caving Mining in Thick Coal Seams under Ultra–thick Sandstone Aquifer. Coal Sci. Technol. 2020, 48, 88–95. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).