A Study on Psychospatial Perception of a Sustainable Urban Node: Semantic–Spatial Mapping of User-Generated Place Cognition at Hakata Station in Fukuoka, Japan

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

1.2. Literature Review

1.2.1. Environmental Psychology and Spatial Perception

1.2.2. User Experience in Transit and Commercial Environments

1.2.3. Multilingual UGC and NLP Approaches to Spatial Cognition

1.3. Research Purpose and Contributions

- (1)

- To identify major semantic themes in multilingual user-generated narratives and examine their correspondence with Hakata Station’s functional zones using TF–IDF vectorization, K-means clustering, and chi-square analysis.

- (2)

- To construct six environmental psychology indicators from multilingual UGC and evaluate their effects on emotional valence through logistic regression, particularly emphasizing the role of Functional Convenience.

- (3)

- To analyze psychospatial patterns across spatial areas—including emotional accumulation, cognitive strain, restorative effects, exploratory engagement, and social belonging—to derive user-centered design insights for sustainable urban nodes.

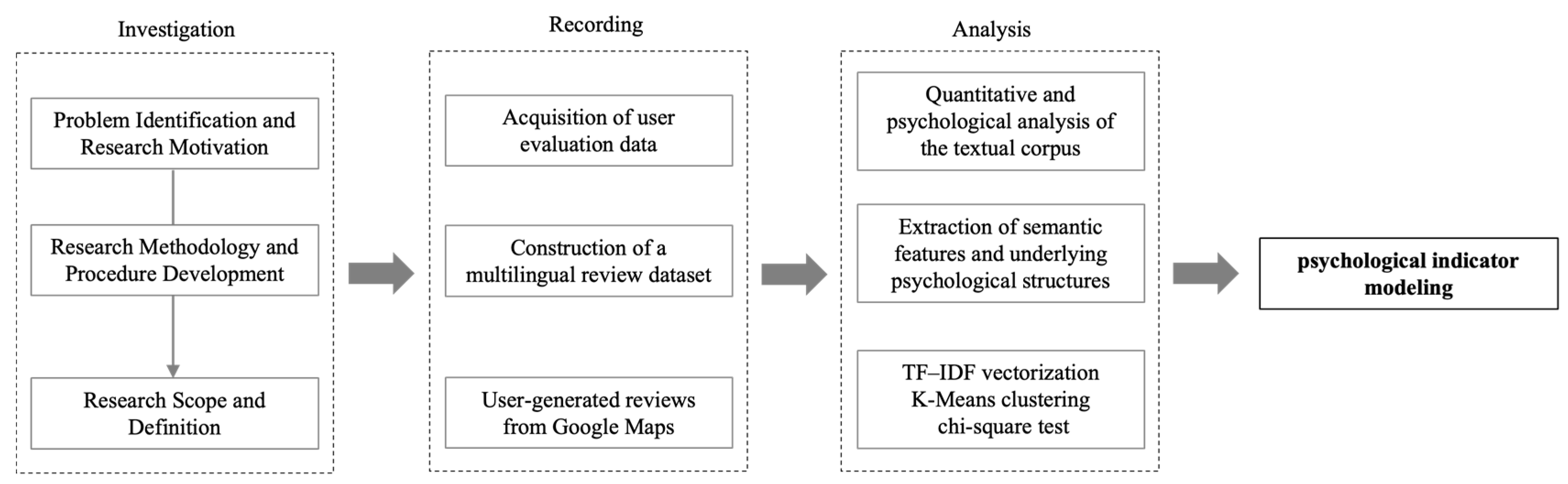

2. Materials and Methods

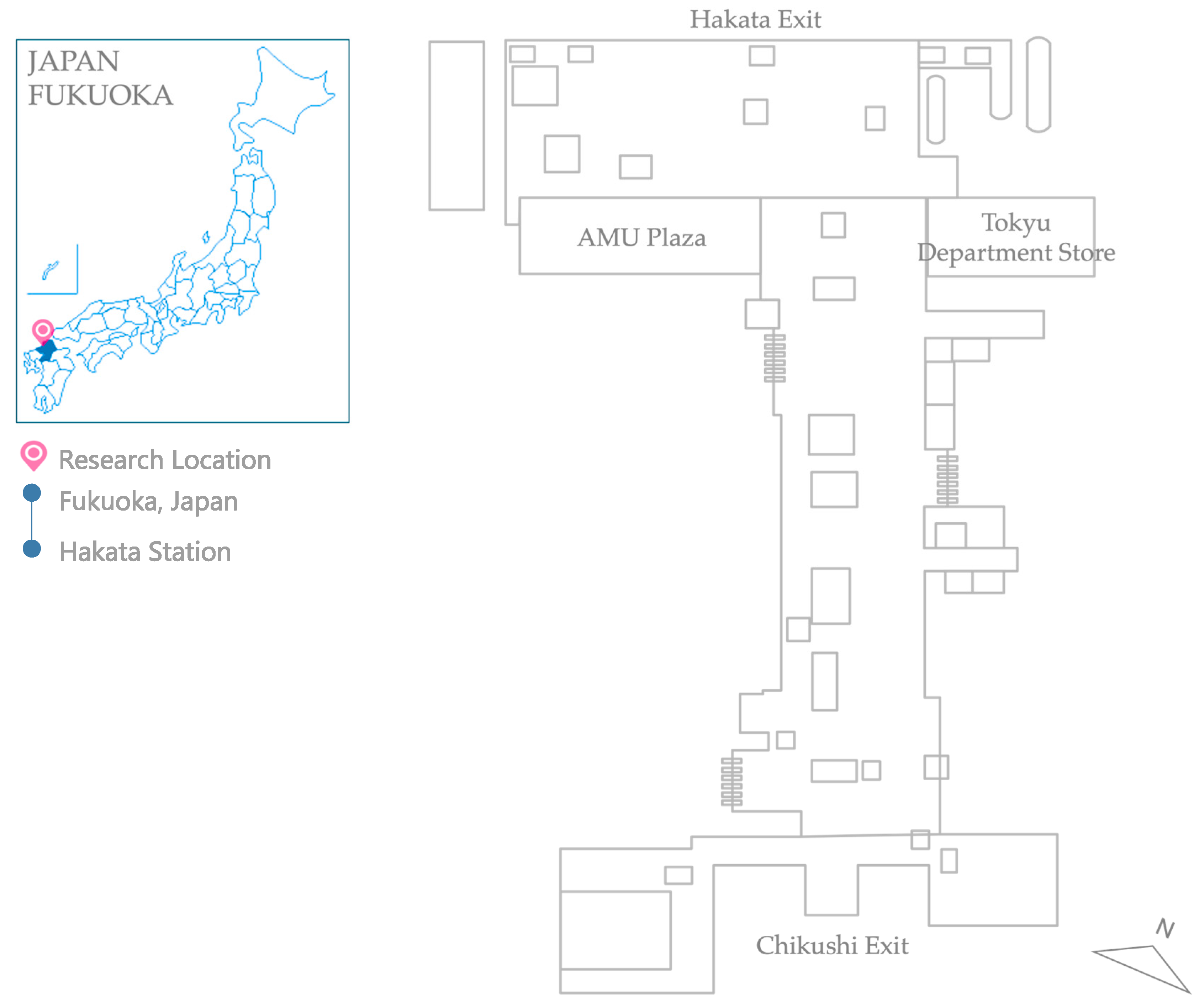

2.1. Research Area and Subjects

2.2. Data Sources and Collection Procedure

2.3. Semantic Consistency Check

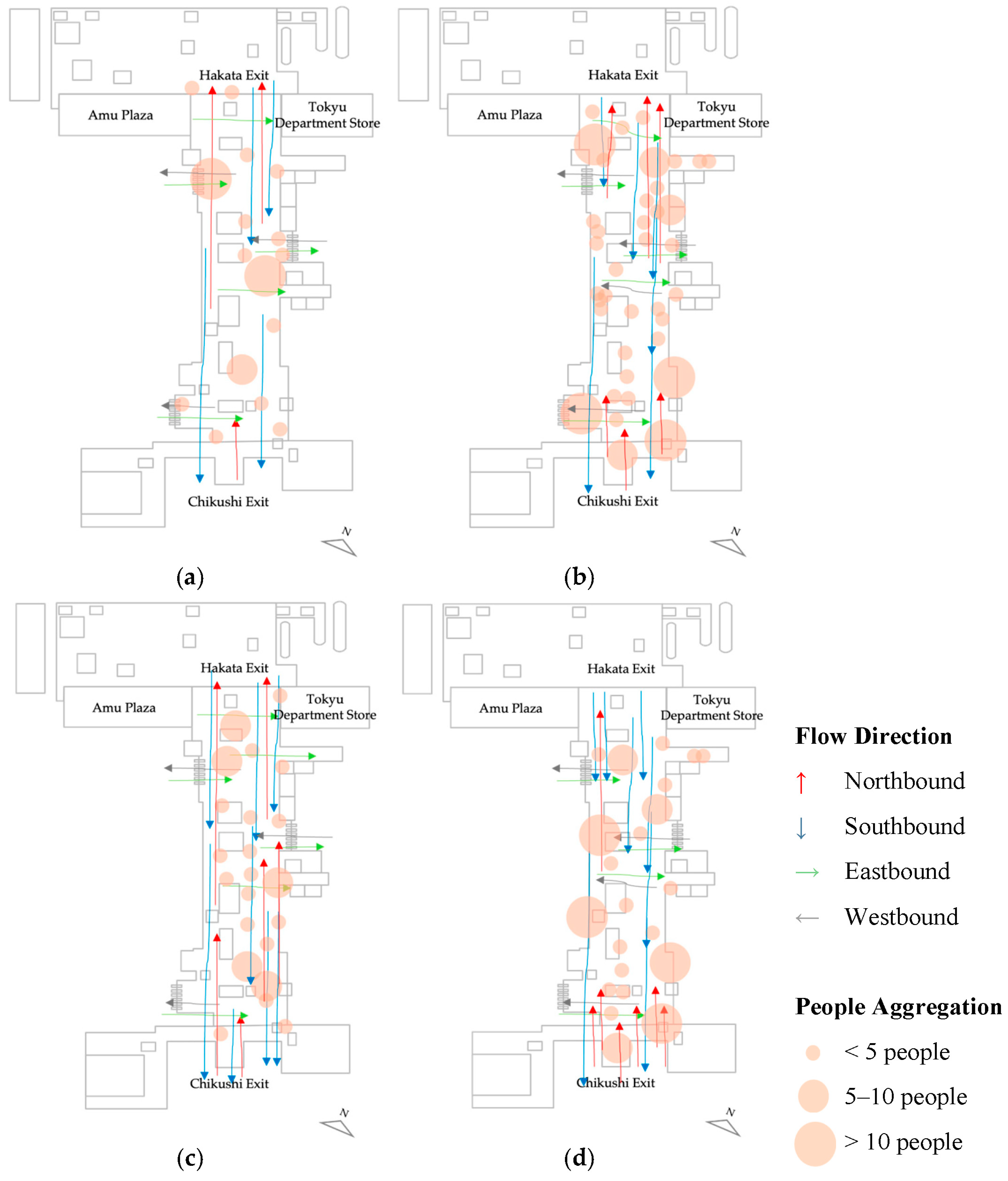

2.4. Functional Zoning and Review Mapping

2.5. Semantic Analysis and Clustering Procedure

2.6. Environmental Psychology Indicators and Hypothesis Testing

2.7. Methodological Innovation and Advantages

3. Results

3.1. Correspondence Between Semantic Clusters and Functional Zones

3.1.1. Term Frequency–Inverse Document Frequency (TF–IDF) Vectorization

- C0: Passenger flow and crowding;

- C1: Entrance impressions;

- C2: Ticketing and reservation processes;

- C3: Waiting and rest experiences;

- C4: Commercial convenience.

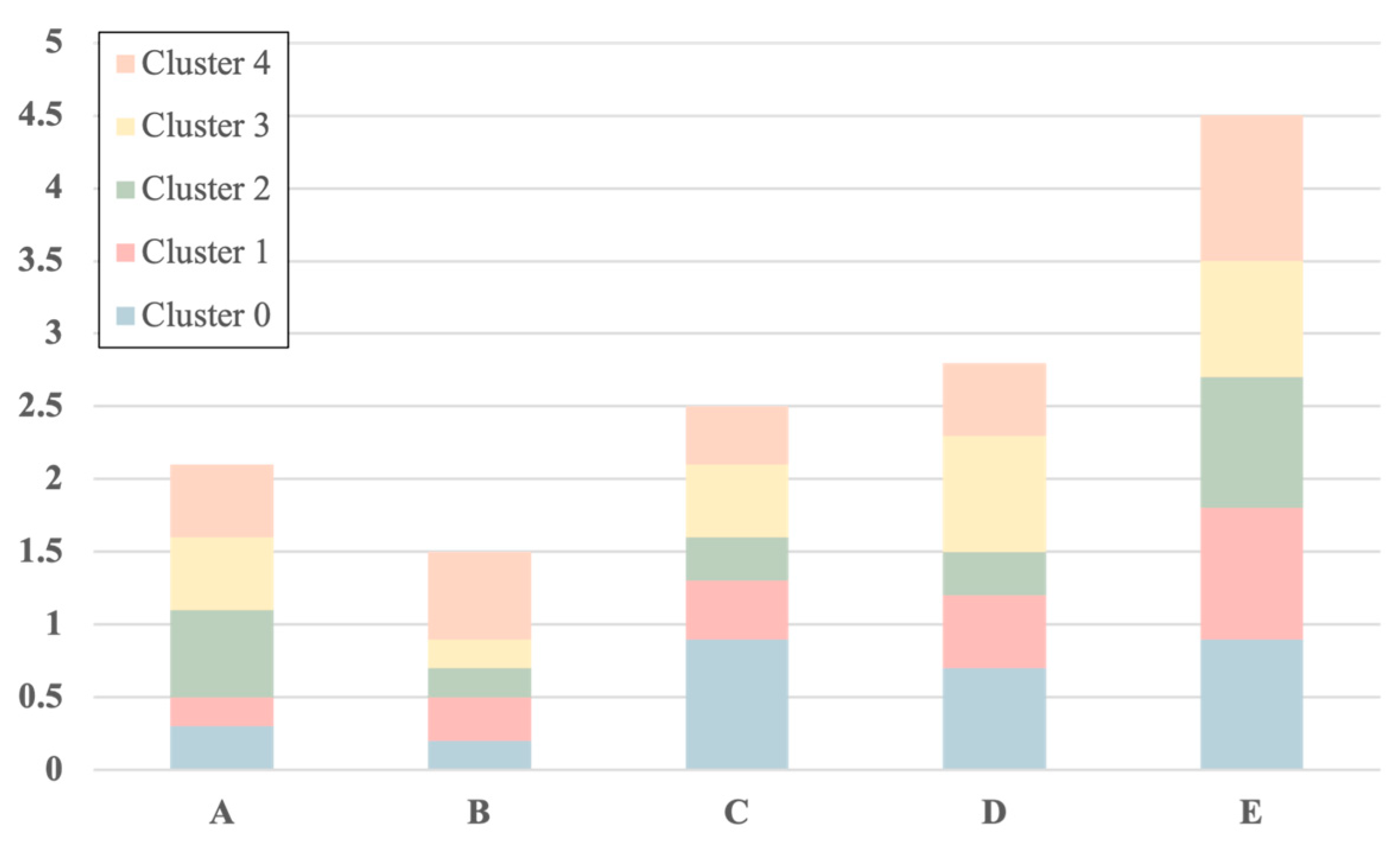

3.1.2. The K-Means Clustering Method

- C0 was highly concentrated in the transfer corridors (Zone B);

- C2 appeared exclusively in the ticketing area (Zone A);

- C3 was mainly located in the waiting and rest areas (Zone C);

- C1 was closely associated with the entrance hall (Zone D);

- C4 was predominantly concentrated in the commercial and dining spaces (Zone E).

3.2. Environmental Psychology Indicators and Emotional Responses

3.2.1. Positive Emotion Proportions and Observed Versus Expected Values

3.2.2. Correlation and Predictive Effects of Environmental Psychology Indicators

3.3. Semantic Patterns Across Functional Zones

4. Discussion

4.1. Alignment with Existing Theories

4.2. Divergence and Added Contributions

5. Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

6.1. Validation of Semantic Clusters and Spatial Zones

6.2. Quantifying Environmental Psychology Indicators

6.3. Psychospatial Preferences Reflected in User Reviews

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| ID | Usable Comment (5/158/607) | Language | Cluster | Spatial Zone | Sentiment | Confidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 도시인구에 비해 크고 인파 엄청남. 신칸센. | KR | 0 | B | Positive | 0.98 |

| 2 | Needs to be more modern | EN | 1 | D | Positive | 0.62 |

| 3 | The station itself is relatively well signed, Shink platforms are the higher numbers, but there are plenty of boards showing the departure times. … | EN | 3 | C | Positive | 0.98 |

| 4 | Long queues for reservations, but can just help u reserve for 1 journey! Just ask passengers to queue up again. | EN | 2 | A | Negative | 0.94 |

| 5 | お土産屋さんが多数あり、お土産をここで 全て買えるで便利です。 | JP | 4 | E | Positive | 0.83 |

References

- La Paix, L.; Geurs, K.T. Train Station Access and Train Use: A joint Stated and Revealed Preference Choice Modelling Study. In Accessibility, Equity and Efficiency; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2016; pp. 144–166. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, R.; Au, W.T. Scale Development for Environmental Perception of Public Space. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 596790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong-Jian, Y. Approaches and Effectiveness of Sustainable Environment and Development Planning. J. Nat. Resour. 1998, 13, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H.-S. Environmental Psychology for Architecture; Tianyuan City Culture Affairs: Taipei, Taiwan, 1996.

- Barker, R.G. Ecological Psychology: Concepts and Methods for Studying the Environment of Human Behavior; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Lei-Ching, H.; Kung-Hsia, Y. Environmental Psychology: Environment, Perception, and Behavior; Wunan Books Publishing Co., Ltd.: Taipei, Taiwan, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.-J. Exploring the Relationships Between Colors in Lighting and Environment on Emotional Experience and Visual Preference. Master’s Thesis, National Taiwan University, Taipei City, Taiwan, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, W.-C. The Effect of Environmental Color Composition and Harmony on Emotional Experience and Landscape Preference. Master’s Thesis, National Taiwan University, Taipei City, Taiwan, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, S.-H.; Chung, W.-L.; Chang, C.-Y. The Lungs in the Urban-Using attention restorative theory, preference matrix, and eight perceived dimensions to discuss the environmental design and configuration of Daan Forest Park. Landsc. Archit. Q. 2021, 28–39. [Google Scholar]

- Rushton, G. Analysis of spatial behavior by revealed space preference. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1969, 59, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin, L. Theories and Extensions of Environmental Behavior in Environmental Behavior Studies. Archit. J. 2008, 30–33. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, W.-Y. The Effect of Facility in the Open Space on Waiting Behavior. Master’s Thesis, Chung Yuan Christian University, Taoyuan City, Taiwan, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Nasar, J.L. The Evaluative Image of the City. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1990, 56, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; The M.I.T. Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Canter, D. The Psychology of Place. In Readings on the Psychology of Place; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2023; pp. 70–75. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.-J. Cognitive Map and Preference Matrix-An Introduction to the Study of Environmental Psychology. J. Build. Plan. Natl. Taiwan Univ. 1990, 5, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonet, M.; Vater, C.; Abati, C.; Zhong, S.; Mavros, P.; Schwering, A.; Raubal, M.; Hölscher, C.; Krukar, J. Probing mental representations of space through sketch mapping: A scoping review. Cogn. Res. Princ. Implic. 2025, 10, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.-Y. Re-Examining the Relationships Between Mystery and Landscape Preference. Master’s Thesis, National Taiwan University, Taipei City, Taiwan, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.-C. Relationships Between Visual Complexity and Landscape Preference. Master’s Thesis, National Taiwan University, Taipei City, Taiwan, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.-H. Consumers’ Visual Preference in Mall Shopping. Master’s Thesis, National Taipei University of Technology, Taipei City, Taiwan, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, W.-L. The Effects of Spatial Attributes on Consumers’ Shopping Time at the Night Market: Case Studies of Feng Chia Night Market in Taichung City, Taiwan and Nishijin Market in Fukuoka City, Japan. Master’s Thesis, Feng Chia University, Taichung, Taiwan, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.-C.; Chen, H.-H.; Lin, W.K.; Lee, P.-H. Formulizing the Mental Model for Customer’s Expectation of Consuming Experience: A Prospective of Environmental Psychology. J. E-Bus. 2018, 20, 33–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, S.-C. A Study of Environmental Psychology of the Commercial space—A Case Study of the Food Courts of Department Store in Taipei. Master’s Thesis, Chung Yuan Christian University, Taoyuan City, Taiwan, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.H. The Construction and Representation of Consumption Space in Taipei Main Station Eslite Underground Mall. J. Soc. Sci. Public Aff. Univ. Taipei 2013, 60–91. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, P.-C.; Chang, H.-L. Measuring the Passengers’ Behavior and Related Psychological Influence on Patronizing Intercity Public Transportation Service. Master’s Thesis, National Chiao Tung University, Hsinchu City, Taiwan, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bécu, M.; Sheynikhovich, D.; Tatur, G.; Agathos, C.P.; Bologna, L.L.; Sahel, J.-A.; Arleo, A. Age-related preference for geometric spatial cues during real-world navigation. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazova, I.; Laczó, J.; Rubinova, E.; Mokrisova, I.; Hyncicova, E.; Andel, R.; Vyhnalek, M.; Sheardova, K.; Coulson, E.J.; Hort, J. Spatial navigation in young versus older adults. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2013, 5, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying-Ren, C. A Study on the Relationships Among Leisure Motivation, Leisure Participation, and Leisure Environment Preference of the Elderly. Master’s Thesis, Chaoyang University of Technology, Taichung County, Taiwan, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, H.M.; Hoebel, C.; Loftis, K.; Gilbert, P.E. Spatial pattern separation in cognitively normal young and older adults. Hippocampus 2012, 22, 1826–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhakka, R.; Poikolainen, J.; Karisto, A. Spatial practises and preferences of older and younger people: Findings from the Finnish studies. J. Soc. Work. Pract. 2015, 29, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhi, H.-D. Resources in Environmental Psychology. J. Build. Plan. Natl. Taiwan Univ. 1989, 4, 115–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvin, K. How Far, by Which Route and Why? A Spatial Analysis of Pedestrian Preference. J. Urban Des. 2008, 13, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tas, D.; Sanatani, R.P. Geo-located aspect based sentiment analysis (ABSA) for crowdsourced evaluation of urban environments. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.12253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, M.L.C.; Boeing, L.P.; Carvalho, W.S.; Duarte, R.B. Natural Language Processing, Sentiment Analysis, and Urban Studies: A Systematic Review. In Proceedings of the XXVII International Conference of the Ibero-American Society of Digital Graphics, Punta del Este, Uruguay, 29 November–1 December 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholamnia, M.; Eslamirad, N.; Sajadi, P.; Zarin, Z.; Pilla, F. Leveraging large language models for citizen-centric urban accessibility analysis: A case study using Airbnb reviews in Dublin. Spat. Inf. Res. 2025, 33, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tori, F.; Tori, S.; Keseru, I.; Ginis, V. Performing sentiment analysis using natural language models for urban policymaking: An analysis of Twitter data in Brussels. Data Sci. Transp. 2024, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, M.-H. What Makes an Online Review Helpful to Consumers? Master’s Thesis, Chaoyang University of Technology, Taichung City, Taiwan, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.-C. Extraction and Analysis of Research Topics Based on NLP Technologies. In Proceedings of the Research on Computational Linguistics Conference XV, Hsinchu, Taiwan, September 2003; pp. 231–255. Available online: https://aclanthology.org/volumes/O03-1/ (accessed on 1 December 2025). (In Chinese).

- Tsai, C.-C. Sentiment Analysis with Google Map Reviews and Recommender System. Master’s Thesis, National Taiwan University of Science and Technology, Taipei, Taiwan, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, C. Review Application of Aspect Based Sentiment Analysis. Master’s Thesis, National Central University, Taoyuan City, Taiwan, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, C.-Y.; Zhao, S. A Study on the Spatial Structure of Urban Nodes and the Psychological Impact of Users’ Environment–A Case Study of the Hakata Station, Fukuoka. In Proceedings of the 14th International Symposium on City Planning and Environmental Management in Asian Countries, Fukuoka, Japan, 11–13 January 2025; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, T.; Okazaki, J.; Tokunaga, T. Visual Search in Way-Finding at Subway Stations. J. Archit. Plan. Archit. Inst. Jpn. 2001, 66, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.-N. A Study on a Universal Design Perspective to Review the Indicator System Design–The Case Study of MRT Taipei Main Station and Station Front Metro Mall. Master’s Thesis, National Taipei University of Technology, Taipei City, Taiwan, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kuan, M.-Y. With a Perspective of Universal Design to Review the Demand of the Aged Using Transferring Sign System of Taipei Main Station. Master’s Thesis, National Taipei University of Technology, Taipei City, Taiwan, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, B.; Liu, C.; Mu, T.; Xu, X.; Tian, G.; Zhang, Y.; Kim, G. Spatiotemporal fluctuations in urban park spatial vitality determined by on-site observation and behavior mapping: A case study of three parks in Zhengzhou City, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 64, 127246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunping, Z.; Jianxin, Z. Place Identity: An Analysis from the Perspective of Environmental Psychology. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 19, 1387–1396. [Google Scholar]

| Zone | Functional Area Description | Pedestrian-Density Proxy (per 100 Chars) |

|---|---|---|

| A | Ticketing & Reservation Area | 1.82 |

| B | Transfer Corridors/ Main Passageways | 3.04 |

| C | Waiting/Open Rest Areas | 0 |

| D | Entrance/Navigation Nodes | 1.44 |

| E | Dining & Amenity Zone | 0.53 |

| Cluster Index | Theme Label | Example Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Passenger flow and crowding | people, crowded, congestion, design, walkways |

| 1 | Entrance impressions | lobby, entrance, scale, impression, landmark |

| 2 | Ticketing and reservation processes | tickets, booking, queues, waiting, services |

| 3 | Waiting and rest experiences | rest, comfort, relaxation, clean, tidy |

| 4 | Commercial convenience | food, dining, shopping, stores, convenient |

| Cluster | User Review | TF–IDF Score |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Quite a crowded station, especially during rush hours. | 2.00 |

| 0 | It gets really crowded here. | 1.08 |

| 1 | It’s always so crowded. | 1.00 |

| 1 | The station is huge. | 1.00 |

| 0 | The connection between JR and the subway is bad. | 1.00 |

| 4 | There aren’t enough restrooms. | 1.00 |

| 1 | Not enough bathrooms, seriously. | 1.00 |

| 1 | Pretty average. | 1.00 |

| 0 | Always packed with people. | 1.00 |

| 1 | Just an ordinary station. | 1.00 |

| 0 | Very clean but always crowded. | 1.00 |

| 0 | Always full of people. | 1.00 |

| 0 | The biggest station in Kyushu, with lots of shops and train lines. | 1.00 |

| 0 | Crazy crowded during rush hours. | 1.00 |

| 0 | Always packed with people. | 1.00 |

| 4 | The atmosphere is lively. | 1.00 |

| 0 | A busy area with lots going on. | 1.00 |

| 3 | Pretty big space. | 1.00 |

| 3 | It’s a major station. | 1.00 |

| 4 | Subway access is easy. | 0.97 |

| 4 | Transportation is super convenient. | 0.95 |

| 4 | There are lots of souvenir shops around. | 0.94 |

| 4 | Plenty of restaurants here. | 0.89 |

| 4 | So many shops everywhere. | 0.85 |

| 4 | Really convenient. | 0.71 |

| 1 | Beautiful place. | 0.71 |

| 1 | Coming to Hakata always feels energetic. | 0.71 |

| 1 | Always feels comfortable using this station. | 0.71 |

| 4 | It’s close to the airport, which is great. | 0.71 |

| 4 | Gets super crowded during winter holidays. | 0.71 |

| 1 | The staff here are awesome. | 0.71 |

| 1 | This is the heart of Kyushu. | 0.71 |

| 3 | Right at the center of Kyushu. | 0.58 |

| 2 | Had to wait in a long line when booking. | 0.58 |

| 3 | Hakata Station is huge. | 0.58 |

| 2 | A bit of a hassle sometimes. | 0.58 |

| 3 | Taking the train can be tricky. | 0.58 |

| 3 | You’ll see lots of locals and tourists. | 0.58 |

| 3 | It’s a large-scale station. | 0.58 |

| 3 | The staff are friendly. | 0.58 |

| 2 | Even for first-timers, it should be easier to understand. | 0.58 |

| 2 | They only help with one-way ticket bookings. | 0.58 |

| 2 | Makes passengers line up repeatedly. | 0.58 |

| 2 | You have to exit the gate to buy a new ticket when transferring to the Shinkansen. | 0.58 |

| 2 | Needless to say. | 0.45 |

| 2 | Speechless. | 0.45 |

| 2 | So now I use other stations to pick up my tickets carefully. | 0.45 |

| 2 | It’s the biggest terminal station in Kyushu. | 0.45 |

| 3 | Feels nostalgic coming back. | 0.41 |

| 3 | More and more rail lines are opening—it’s getting even more convenient. | 0.41 |

| Spatial Zone | Negative | Positive | Positive Ratio (%) | Negative Ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A: Ticketing and reservation areas | 5 | 5 | 50 | 50 |

| B: Transfer corridors | 12 | 42 | 77.8 | 22.2 |

| C: Waiting and rest areas | 2 | 8 | 80 | 20 |

| D: Entrance and wayfinding areas | 3 | 18 | 85.7 | 14.3 |

| E: Dining and service facilities | 6 | 56 | 90.3 | 9.7 |

| Cluster | Zone A | Zone B | Zone C | Zone D | Zone E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 54 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 0 |

| 2 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 63 |

| Cluster | Zone A | Zone B | Zone C | Zone D | Zone E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3.42 | 18.46 | 3.42 | 7.18 | 21.53 |

| 1 | 1.33 | 7.18 | 1.33 | 2.79 | 8.37 |

| 2 | 0.63 | 3.42 | 0.63 | 1.33 | 3.99 |

| 3 | 0.63 | 3.42 | 0.63 | 1.33 | 3.99 |

| 4 | 3.99 | 21.53 | 3.99 | 8.37 | 57.12 |

| Cluster | Zone A | Zone B | Zone C | Zone D | Zone E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3.42 | 68.46 | 3.42 | 7.18 | 21.53 |

| 1 | 1.33 | 7.18 | 1.33 | 118.79 | 8.37 |

| 2 | 138.63 | 3.42 | 0.63 | 1.33 | 3.99 |

| 3 | 0.63 | 3.42 | 138.63 | 1.33 | 3.99 |

| 4 | 3.99 | 21.53 | 3.99 | 8.37 | 57.12 |

| Functional Zoning | Wayfinding Usability | Crowding Density | Seating and Rest Availability | Functional Convenience | Environmental Quality | Information Legibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0 | 0.03 | 0 | 0.28 | 0 | 0 |

| B | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| C | 0 | 0 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0 | 0 |

| D | 0.02 | 0 | 0.05 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| E | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0 |

| Functional Zoning | Pearson | Logit | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wayfinding Usability | 0.04 | 1.9 | 0.31 |

| Crowding density | −0.01 | −0.51 | 0.64 |

| Seating and rest availability | 0.02 | 0.79 | 0.53 |

| Functional convenience | 0.18 | 3.45 | 0.05 |

| Environmental quality | 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.87 |

| Information legibility | 0.03 | 1.1 | 0.42 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tsai, C.; Zhao, S. A Study on Psychospatial Perception of a Sustainable Urban Node: Semantic–Spatial Mapping of User-Generated Place Cognition at Hakata Station in Fukuoka, Japan. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10959. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410959

Tsai C, Zhao S. A Study on Psychospatial Perception of a Sustainable Urban Node: Semantic–Spatial Mapping of User-Generated Place Cognition at Hakata Station in Fukuoka, Japan. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):10959. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410959

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsai, Chiayu, and Shichen Zhao. 2025. "A Study on Psychospatial Perception of a Sustainable Urban Node: Semantic–Spatial Mapping of User-Generated Place Cognition at Hakata Station in Fukuoka, Japan" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 10959. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410959

APA StyleTsai, C., & Zhao, S. (2025). A Study on Psychospatial Perception of a Sustainable Urban Node: Semantic–Spatial Mapping of User-Generated Place Cognition at Hakata Station in Fukuoka, Japan. Sustainability, 17(24), 10959. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410959