Abstract

Abandoned mines, as emblematic heritage spaces in the process of deindustrialization, preserve collective production memory and serve as vital symbols of local identity. However, current redevelopment practices primarily emphasize physical restoration while overlooking the visual expression and interactive communication of regional culture. This study introduces an augmented reality (AR)–based visual narrative framework that integrates regional culture to bridge the gap between spatial renewal and cultural regeneration. Drawing on semiotics and spatial narrative theory, a multidimensional “space–symbol–memory” translation mechanism is constructed, and a coupling model linking tangible material elements with intangible cultural connotations is established. Supported by technologies such as simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM), semantic segmentation, and level of detail (LOD) rendering, a multilayer “position–perception–presentation” module system is designed to achieve stable anchoring of virtual and physical spaces and enable multilevel narrative interaction. Through task-oriented mechanisms and user co-creation, the system effectively enhances immersion, cultural identity, and learning outcomes. Experimental validation in a representative mine site confirms the feasibility of the proposed framework. While the study focuses on a single case, the modular and mechanism-based design indicates that the framework can be adapted to cultural tourism, educational communication, and community engagement applications. The key innovation lies in introducing an iterative “evidence–experience–co-creation” model, providing a new methodological reference for the digital reuse of abandoned mines and the sustainable preservation of industrial heritage.

1. Introduction

With the transformation of global industrial structures and the acceleration of deindustrialization, abandoned mines—emblematic remnants of industrial civilization—are shifting from neglected “abandoned spaces” to critical carriers of cultural revitalization and regional identity reconstruction. They document the historical trajectory of local industrial development and embody the collective social memory and value symbols of mining communities [1]. In recent years, research from Europe, Australia, and other mining regions has shown that the transition and management of closed mines have become a common challenge worldwide, particularly within the broader context of green transformation and post-mining regional development [2,3,4]. However, current reuse practices mainly emphasize physical restoration, landscape redevelopment, and functional adaptation, while the deeper cultural connotations embedded in spatial forms and lived experiences remain insufficiently articulated [5,6]. Global post-mining studies similarly underscore that sustainable transformation requires not only ecological and functional renewal but also the preservation and reinterpretation of cultural narratives and community identities [2]. This disconnect between spatial renewal and cultural narrative weakens the long-term emotional resonance and identity appeal of heritage sites.

Research on the reuse of abandoned mines primarily concentrates on three major areas commonly identified in both domestic and international studies: (1) value assessment and feasibility evaluation, (2) spatial development and functional transformation, and (3) landscape renewal and the visual communication of regional culture. In terms of value assessment, Han [7] proposes a feasibility evaluation model for developing underground mining spaces as tourism resources and empirically verifies its applicability. Cui [8] establishes a comprehensive evaluation system for coal mine reuse, emphasizing the balanced integration of ecological restoration, economic transformation, and social benefits. Regarding spatial development, Hou [9] explores narrative utilization models of underground spaces from the perspective of experiential industrial tourism, providing methods for constructing immersive settings. In landscape renewal and visual communication, Xie. et al. [10] propose strategies rooted in regional culture, underscoring the role of visual design in enhancing heritage adaptability. Building upon these strands of research, studies from other regions similarly address the regeneration of post-mining landscapes, focusing on land-use frameworks and transition pathways [4], the social implications and community dimensions of mine closure [3] and the cultural interpretation of mining landscapes [11]. Parallel work on digital and immersive technologies further highlights the potential of AR/VR in supporting narrative construction and enhancing visitor engagement in heritage environments [12,13]. Although these studies contribute theoretical and practical insights into the regenerative use of abandoned mines, empirical validation remains limited in visualizing cultural information, systematizing narrative mechanisms, and assessing public perception.

Parallel to these developments, the rapid progress of digital technologies has shifted industrial heritage presentation from static exhibitions to interactive, immersive experiences [14]. Augmented reality (AR) has become a widely adopted medium in cultural heritage contexts, enabling the superimposition of spatial guidance and cultural symbols to enhance visitor orientation, comprehension, and engagement [15]. Existing studies have shown that AR applications can strengthen immersion, contextual understanding, and emotional involvement in heritage settings [16,17,18]. International research further demonstrates that integrating AR into heritage environments can improve authenticity, cultural comprehension, and visitor satisfaction, offering opportunities for reinterpreting industrial sites and enriching educational communication [11,12,13,19,20].

At the same time, narrative theory provides additional explanatory power for understanding cultural translation in complex heritage environments. Recent studies show that immersive storytelling enhances learning outcomes, user engagement, and emotional attachment in heritage settings [13,20]. Ryan’s [21] emphasizes user participation in constructing narrative meaning, while Tan [22] elaborates narrative hierarchies that inform the structuring of cultural information. Smith’s [23] concept of heritage as a cultural process highlights the dynamic and socially constructed nature of meaning-making, and Champion’s [24] virtual heritage studies offer technological pathways for reinforcing the sense of historical presence.

In summary, as an essential component of industrial heritage, the protection and reuse of abandoned mines have gradually expanded from physical restoration to cultural translation and digital interaction. However, systematic cultural reconstruction through narrative mechanisms and visual expression remains insufficient. AR demonstrates unique potential in spatial recognition, semantic reconstruction, and immersive visual storytelling, offering new approaches for the digital preservation and value communication of abandoned mines and opening feasible pathways to strengthen local identity and regenerate industrial memory. Therefore, developing a framework that integrates regional culture, visual design, and AR-based narrative mechanisms presents theoretical innovation and delivers practical value for industrial heritage revitalization, educational communication, and cultural sustainability.

2. Theories and Methods of AR-Based Visual Narratives for Regional Culture in Abandoned Mines

2.1. Spatial Narrative Mechanisms and Cultural Translation Pathways of Abandoned Mines

During prolonged extraction, closure, and reuse, abandoned mines undergo continuous spatial layering and functional transformation, producing environments with complex temporal strata. A single linear narrative cannot accommodate such multidimensional information. To reconstruct historical contexts and reactivate collective social memory, a systematic framework for expression must be established across spatial structure, cultural semantics, and visual communication. Shafts, roadways, work faces, and remaining equipment are more than physical remnants—they encapsulate organizational practices, accident memories, and localized working experiences. By linking these spatial units with associated event cues, an “event–space–memory” network can be constructed, providing a foundation for visitors to build coherent narrative pathways during exploration [25].

Spatial analysis methods provide technical support for constructing this narrative network. Space syntax and situational analysis quantify accessibility, connectivity, and visibility changes, thereby identifying key nodes and interactive points where information converges [26]. In underground mines, where lighting is limited, passages are enclosed, and elevation differences are significant, careful placement of narrative nodes, adjustment of path rhythm, and control of information density are particularly critical. Positioning core narrative content in areas with higher safety and accessibility, while placing directional cues at spatial transitions, helps maintain visitors’ sense of orientation and cognitive coherence, reducing perceptual fragmentation and excessive cognitive load caused by complex spaces.

Cultural semantic translation is a critical process linking physical space with social meaning. The regional culture embodied in abandoned mines typically presents both explicit and implicit dimensions. Explicit symbols—such as headframes, sleepers, pneumatic drills, and miners’ lamps—provide direct visual cues that reconstruct production processes and labor scenes. Implicit dimensions include collective psychological representations such as workers’ ethics of collaboration, safety memories, and religious or ritual practices. The semiotic triad of iconicity, indexicality, and symbolicity offers a structured pathway for semantic encoding: iconicity supports visual reconstruction and 3D modeling, indexicality reinforces causal links between events and physical remains, and symbolicity embeds local identity and collective values [27]. This multilayered symbol translation not only increases the cultural density of narratives but also establishes a foundation for semantic annotation and interactive experiences in subsequent digital media, particularly AR environments.

Visual communication serves as a bridge in the realization of narrative experiences. Existing studies show that information layering, progressive disclosure, and color-based emotional cues help visitors build a continuous cognitive chain from perception to understanding and ultimately to identification during spatial exploration [28,29,30,31,32]. In complex heritage environments, visual design strategies should move beyond superficial physical replication and instead optimize information processing and activate cultural memory through symbolic abstraction, schematic representation, and affective cues. Recent empirical research demonstrates that such approaches not only enhance immersion and the perception of cultural value but also foster emotional attachment and environmental responsibility [15]. These strategies are particularly applicable to mining spaces with high safety requirements and limited visual accessibility.

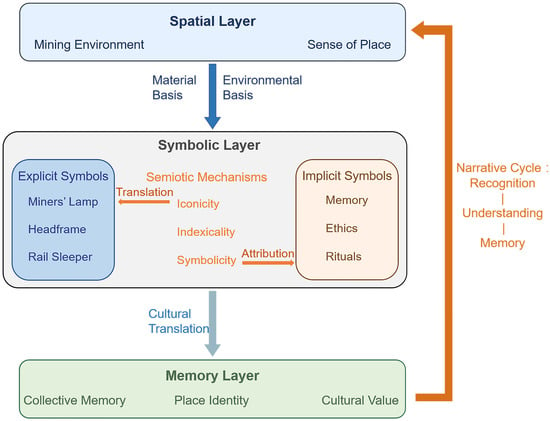

Building on spatial structure analysis, cultural semantic translation, and visual communication optimization, a narrative translation mechanism composed of the spatial layer–symbolic layer–memory layer can be established (Figure 1). This mechanism links the physical spaces of mines with both explicit and implicit cultural symbols and collective memory, providing a systematic pathway for transforming material features into constructed meaning. Through this model, heritage elements in complex underground environments can be effectively organized and converted into explanatory and participatory narrative systems, thereby laying a methodological foundation for immersive interaction and visual expression in subsequent AR applications.

Figure 1.

Spatial–Symbolic–Memory Narrative Framework for Abandoned Mines. Conceptual model of the spatial, symbolic, and memory layers in abandoned mine environments, illustrating how explicit and implicit symbols mediate the narrative cycle from recognition to understanding and memory.

2.2. AR-Supported Spatial Narrative Mechanisms

Digital and immersive media have reshaped spatial narrative practices by enabling multimodal interactions. AR overlays virtual information onto real physical environments, expanding the interpretive dimension while preserving spatial authenticity, making it suitable for use in structurally complex and low-light underground mines [12]. Compared with virtual reality (VR), AR does not alter the physical environment but overlays digital symbols onto it, allowing users to experience immersive interaction while perceiving the actual setting. These capabilities make AR particularly well-suited for the adaptive reuse of underground industrial heritage spaces [13].

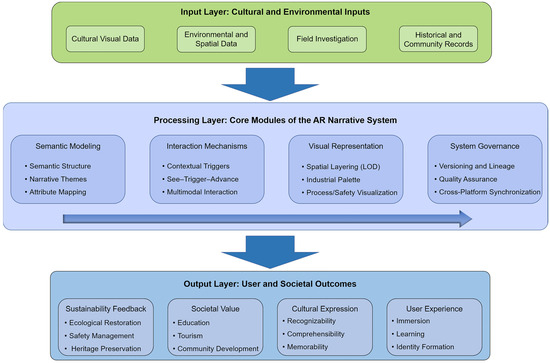

In the narrative practice of abandoned mines, AR constructs dynamic spatial semantics by integrating physical structures, digital symbols, and interactive pathways. Mine entrances serve as trigger nodes for historical events, while tunnels and work faces carry content such as production processes, accident records, and safety knowledge, enabling visitors to gradually establish connections among space, events, and memory during exploration [20]. Path organization based on interactive nodes frees narratives from a single linear sequence, allowing users to enter different narrative branches according to their interests, achieve differentiated experiences and personalized understanding, and at the same time maintain orientation and cognitive coherence. To further clarify the coupling of physical structures, digital symbols, and interactive pathways, the AR-supported spatial narrative mechanism can be abstracted into a systematic technical framework (Figure 2), visually presenting the overall process of data acquisition, semantic construction, and interactive delivery.

Figure 2.

System Framework of AR-Supported Spatial Narrative Mechanisms. Overall architecture of the augmented reality (AR) narrative system, showing how cultural and environmental inputs are transformed through core processing modules into user and societal outcomes.

The introduction of AR not only expands modes of information presentation but also supports the reactivation of cultural meaning. Explicit symbols in mining heritage—such as headframes, sleepers, and miners’ lamps—are visually reconstructed through 3D modeling and semantic tagging, while implicit elements—including the spirit of worker collaboration, local rituals, and collective memory—are transformed into perceivable cultural symbols within blended virtual and physical scenes. Through this integration of symbolization and digitization, visitors can more effectively comprehend historical content and establish emotional connections during spatial exploration, thereby strengthening local identity and the perception of cultural value [33,34]. Visual communication strategies play a crucial role in this process; techniques such as information layering, progressive disclosure, and color- and emotion-based guidance reduce cognitive load in complex spaces and help users transition gradually from perception to understanding.

In addition, AR provides an effective means to enhance the educational and communicative value of heritage presentation. Studies show that AR improves knowledge acquisition and memory retention while strengthening responsibility awareness and cultural resonance through interaction and contextual immersion [20,35,36]. These multidimensional capabilities make AR not only a tool for display but also a critical technological pathway supporting the digital preservation and narrative reconstruction of abandoned mines, providing a methodological foundation for the development of subsequent system platforms and the optimization of user experience.

2.3. Mechanism Integration and Framework Construction

The cultural narrative reconstruction of abandoned mines relies on the deep integration of spatial semantics and digital media. Sole reliance on the direct presentation of physical space is insufficient to convey deeper cultural meanings, while purely virtual displays may undermine the authenticity of heritage sites. Combining spatial narrative structures with the dynamic interactive capabilities of AR enables the hierarchical, contextual, and visualized representation of cultural information within real environments, constructing an integrated expression system that balances readability with immersion.

By analyzing the structural characteristics of shafts, tunnels, work faces, and residual equipment inside the mines, potential narrative nodes can be identified and event–space correspondences can be established. Explicit artifacts—such as headframes, sleepers, and miners’ lamps—and implicit elements—such as collaboration norms, accident memories, and ritual practices—are symbolically processed and organized into an interpretable semantic network. This structure provides a stable framework for transmitting cultural information within complex spaces and reduces cognitive fragmentation caused by environmental obstacles.

Supported by this semantic network, AR expands the expressive dimensions of narrative. Through real-time spatial positioning, scene recognition, and multimodal interaction, previously static symbolic nodes are transformed into dynamically activatable cultural information. Users can trigger different layers of content while moving and revisiting spaces, forming multi-path cognitive trajectories according to their interests. This flexible structure reduces the limitations of one-way linear storytelling, enhances engagement and immersion, and creates conditions for the diverse interpretation of cultural meaning.

Building on the coordination of space and media, a layered overarching framework is constructed, comprising four levels: data and cultural modeling, semantic organization, interactive narrative implementation, and user feedback optimization. This framework emphasizes the updatability of cultural data and semantic annotations, the real-time recording and analysis of interaction data, and the iterative adjustment of narrative pathways and visual representations. Such an approach maintains a balance between technological usability and the depth of cultural expression across different contexts and audiences. Similar multi-level architectures have been validated as feasible in digital heritage and interactive exhibition practices [24,25].

Beyond the technical integration described above, this study also clarifies the theoretical contribution of the proposed framework. Existing spatial-narrative and semiotic approaches often treat material evidence, symbolic interpretation, and user participation as independent components, resulting in fragmented cultural reconstruction in underground heritage environments. Addressing this gap, the present framework establishes a sequential relationship among spatial structure, symbolic elements, and memory formation that is specifically adapted to the spatial constraints and experiential characteristics of abandoned mines. Furthermore, the evidence–experience–co-creation model explicates the internal logic of meaning formation in AR settings: evidence anchors cultural authenticity, experience enables situated perceptual engagement, and co-creation incorporates visitors’ interpretive agency. By positioning these elements as interconnected mechanisms, the framework extends existing theoretical models and provides a more integrated basis for cultural interpretation beyond technical implementation.

Therefore, by organically coupling the semantic structure of spatial narratives with the interactive presentation capabilities of AR, a verifiable, iterative, and scalable implementation pathway is established. This pathway provides structured support for the digital preservation, cultural reconstruction, and public engagement of abandoned mines.

2.4. Research Methods

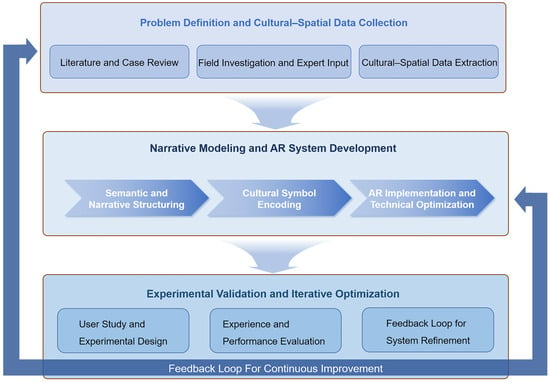

To realize the AR–based visual narrative construction of regional culture in abandoned mines, this study follows an integrated methodological approach of problem identification, mechanism development, application validation, and feedback optimization, forming a systematic pathway for technology implementation and verification (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

AR Narrative Research Framework. Research framework for the development of the AR narrative system, including problem definition, cultural–spatial data collection, narrative modeling, system implementation, and iterative experimental validation.

- (1)

- Problem Identification and Data Collection

At the outset, a systematic review of domestic and international studies on the reuse of abandoned mines and the digitalization of industrial heritage is conducted, followed by a comparative analysis with representative case studies. The review revealed that existing research primarily focuses on material restoration and spatial renewal, with limited efforts to construct integrated models linking spatial semantics, cultural symbols, and interactive logic. To address this gap, the research team conducts field investigations and expert interviews to collect both explicit elements—such as artifact remains and production processes—and implicit cultural data, including collaboration ethics, oral histories, and ritual practices. These data are compiled into a multi-layered cultural information database, providing the semantic foundation and contextual materials for subsequent narrative framework development.

- (2)

- Narrative Modeling and System Implementation

Based on the collected data, a semantic organization framework centered on space–symbol–memory is constructed, translating shafts, tunnels, work faces, and key event nodes within the mines into computable narrative units. The narrative structure adopts a non-linear logic to ensure both openness of information pathways and cognitive coherence. AR technology activates these narrative units through 3D modeling, semantic tagging, and multimodal interaction, enabling users to experience dynamic cultural content within real environments. During system implementation, technical optimizations—including feature enhancement, illumination compensation, local relocalization, and layered rendering—are applied to address the challenges of low lighting and complex underground structures. These measures ensure usability, interaction fluency, and visual immersion in both real and simulated mining environments.

- (3)

- Application Validation and Iterative Optimization

At the application stage, the developed AR-based visual narrative system is experimentally validated in representative mining environments. A quasi-experimental pretest–posttest design is adopted, dividing participants into a traditional display group and an AR narrative group. Quantitative evaluation is conducted using three key indicators—immersion, cultural identity, and knowledge acquisition—while questionnaires and interviews are used to capture subjective experiences and improvement suggestions. Experimental data are statistically tested under conditions ensuring ecological validity, forming a feedback loop of user experience–effect evaluation–system optimization to further refine the technical implementation and narrative strategies.

3. Systematic Implementation Methods and Platform Development

3.1. Data and Cultural Semantic Modeling

The complex spatial morphology and profound historical context of abandoned mines require the establishment of data and semantic foundations that integrate geometric accuracy with cultural significance before system implementation. To ensure AR content aligns with the real mine environment and supports meaningful interaction, we integrate multiple data sources for high-fidelity digital reconstruction. Specifically, we use laser scanning (LDAR, Zenmuse L1, DJI, Shenzhen, China) and multi-angle photography (Nikon D850 camera, Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) to capture fine details of underground structures—such as tunnel shapes and relic contours—while drones (DJI Mavic 3, DJI, Shenzhen, China) provide additional mapping of above-ground terrain. To further enhance geometric fidelity and ensure operational safety, geological drilling data and monitoring records—such as roof separation measurements and surrounding-rock stability observations—are incorporated to refine and calibrate the reconstructed model. Based on the corrected spatial geometry, key underground features, including geological structures, spatial dimensions, safe passages, and entry–exit points, are then systematically encoded within a Geographic Information System (GIS) platform (ArcGIS Pro 3.2, Esri, Redlands, CA, USA). This GIS-based semantic layer provides the spatial foundation for subsequent AR alignment, path planning, and risk assessment [37,38,39,40,41]. To improve spatial accuracy and safety, geological drilling data and monitoring records on roof separation and surrounding rock stability are integrated to correct model deviations. Geological structures, spatial dimensions, safety passages, and entry and exit points are then hierarchically annotated on a Geographic Information System (GIS) platform, forming a spatial information layer that supports path planning and risk assessment [42].

Building on the spatial model, cultural semantic modeling extends geometric data into social and historical dimensions. Archival texts, historical images, and engineering drawings are collected and combined with oral history interviews and process reconstruction experiments to capture material remains, production processes, lived experiences, and local ritual practices associated with the mines. To organize cultural information clearly, we apply a ‘material–behavior–spirit’ framework: ‘material’ includes physical relics such as miners’ lamps, ‘behavior’ refers to work routines and customs, and ‘spirit’ captures values such as miners’ dedication. Digital tools such as knowledge graphs link these elements—for example, connecting a pneumatic drill from the 1980s to stories of how miners used it [18]. This modeling approach not only facilitates dynamic information retrieval but also provides data support for extracting narrative themes and enabling the computable management of cultural symbols.

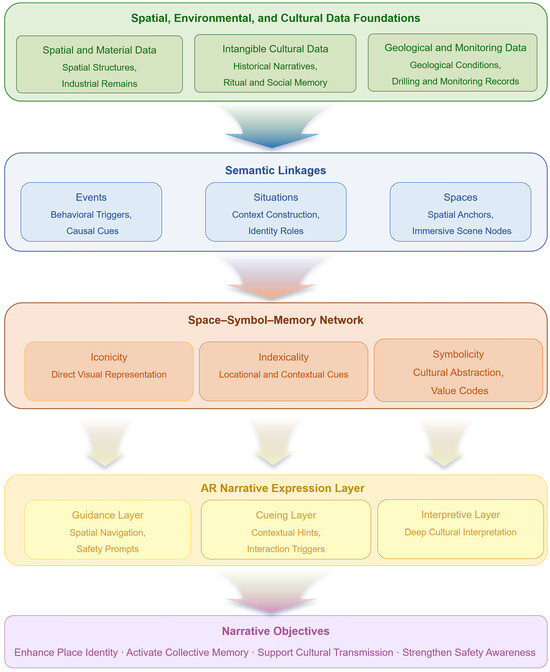

Expanding upon this semantic organization, a multi-layered space–symbol–memory network is established (Figure 4). By calculating semantic weights and narrative relevance, key nodes with high cultural information density and potential interactive hotspots are identified and linked to parameters such as spatial accessibility and visual continuity. The resulting network supports the optimization of narrative pathways and the design of user interactions. Such a data-driven modeling strategy provides a verifiable technical foundation for cultural information overlay, interactive triggering, and visual translation in AR environments, while ensuring the accuracy and immersive quality of narrative presentation within complex underground spaces.

Figure 4.

Cultural and semantic modeling framework. Spatial, environmental, and cultural data foundations and the space–symbol–memory framework used for semantic modeling and AR narrative expression in abandoned mines.

3.2. Interactive Pathways and Narrative Practice

After constructing the spatial and cultural semantic networks, the system transforms abstract data structures into perceivable and interactive immersive narrative experiences. To address the challenging underground conditions—such as dim illumination, winding passages, and limited surface textures—the system integrates Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) with visual–inertial odometry (VIO). Basic illumination compensation and feature enhancement techniques help maintain stable localization and consistent rendering in low-light and texture-sparse sections of the mine. The system is implemented using Unity and AR Foundation as core frameworks to ensure cross-device consistency in visualization and interaction.

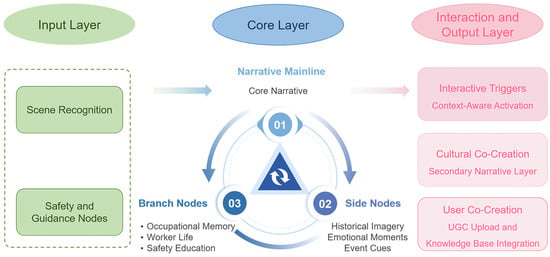

The interaction logic is organized around a non-linear narrative structure, in which storytelling pathways consist of both a main thread and multiple branches. The main thread focuses on key historical milestones such as mine construction, extraction, and closure, while the branches supplement safety culture, workers’ lived memories, and local customs. This approach preserves the continuous transmission of core information while increasing exploration freedom and supporting personalized experiences (Figure 5). To support the non-linear narrative structure, the system incorporates a context-aware triggering mechanism that monitors users’ position, orientation, and movement within the mine. When users approach specific spatial nodes or culturally significant relics, the system infers the corresponding narrative context and automatically activates related multimedia content, including animated process reconstructions, spatialized audio, and voice narration. This automatic triggering reduces unnecessary interaction steps and ensures a continuous and coherent narrative flow in constrained underground environments. This dynamic content scheduling strategy effectively reduces attention interruptions caused by manual selection and allows the narrative chain to unfold naturally.

Figure 5.

AR-Supported Spatial Narrative Structure. Node-based AR spatial narrative structure, linking the core narrative with branch and side nodes and connecting them to interaction and output layers.

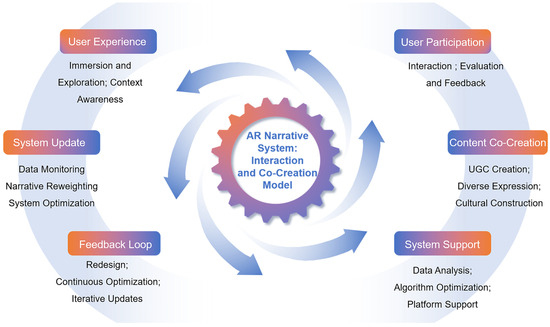

In terms of user participation, the platform supports multi-user collaborative interaction, allowing participants to annotate, leave voice comments, and share navigation trajectories within the same virtual scene. The system records and analyzes behavioral indicators—including node visit frequency, dwell duration, and users’ navigation paths—to refine narrative weighting and reorganize content scheduling, thereby establishing a data-driven adaptive updating mechanism that enhances narrative relevance and continuity (Figure 6). This mechanism not only enhances the flexibility and relevance of the narrative but also creates conditions for the co-construction and continuous expansion of local cultural knowledge [43].

Figure 6.

Interaction and Co-Creation Cycle of the AR Narrative System. Interaction and co-creation model of the AR narrative system, integrating user experience, user participation, content co-creation, system support, feedback, and system update.

Visual communication strategies permeate the entire interactive process, performing essential functions of information layering and cognitive guidance. Through symbolic abstraction, color gradients, and progressive disclosure, the platform helps users gradually transition from sensory perception to semantic understanding and emotional connection. These strategies reduce the cognitive load imposed by complex spatial environments while enhancing users’ sense of safety and orientation. Existing research shows that such design approaches significantly improve immersive experience, accessibility of cultural information, and the effectiveness of educational communication, making them particularly suitable for knowledge translation and contextualized learning in industrial heritage settings [44].

3.3. Visual and Experience Optimization

To ensure the AR narrative system achieves both cultural expressiveness and cognitive accessibility, the platform integrates visual design strategies that regulate information complexity and support user orientation. Visual expression draws from the industrial and geological characteristics of the mine environment, using simplified geometric forms and standardized color palettes to enhance the recognizability of virtual elements while preserving authenticity. This approach ensures that digital representations retain regional cultural distinctiveness and remain cognitively accessible for users constructing meaning in immersive environments [45].

On this basis, the system converts cultural information into a layered and progressive structure for visualization and narrative delivery. Instant prompts employ simplified symbols, directional markers, and color gradients to support spatial orientation and safety guidance. Contextual explanations integrate voice narration, animations, and data visualizations to enrich cultural background and strengthen users’ understanding of production processes, historical events, and social values. Deep narratives provide extended texts, archival images, and interactive data to enable multi-level information access and autonomous exploration [12,13].

User experience is continuously improved through a behavior-driven feedback loop. The system tracks engagement indicators—such as the duration and frequency of content interaction and the success of user actions—and supplements them with qualitative feedback related to cultural comprehension, spatial comfort, and visual clarity. These insights are used to adjust narrative emphasis and refine content flow, enabling iterative enhancement of immersion, usability, and cultural understanding. This process prevents content stagnation and ensures flexible adaptation of the system to diverse user pathways [34].

To strengthen immersion, visual and auditory cues—such as gradient lighting, dynamic particles, and localized soundscapes—are employed to guide attention and shape emotional involvement. These strategies align with findings that perceived authenticity and contextual realism significantly influence satisfaction and learning in heritage experiences [33]. The integration of these techniques reduces cognitive load, enhances safety, and deepens engagement with cultural memory.

4. System Implementation and Experimental Analysis

4.1. System Construction and Visual Narrative Implementation

This study designs and implements an AR visual narrative system based on an integrated framework of spatial storytelling, cultural semantics, and user interaction, tailored to the unique spatial and lighting conditions of abandoned mines. The system relies on SLAM and visual-inertial odometry as its core positioning technologies and is enhanced through three key technical optimizations:

- Low-light and texture-sparse adaptation—Feature enhancement and illumination compensation algorithms, combined with localized high dynamic range (HDR) rendering, maintain stable tracking and visual presentation even in extremely dimly lit tunnels.

- Complex space positioning optimization—Layered spatial modeling and local relocalization strategies reduce drift and interaction latency within winding underground passages.

- Large-scale efficient rendering—A Level of Detail (LOD) mechanism and real-time resource scheduling ensure smooth rendering and immersive experience in extensive scenes containing numerous relics and cultural symbols.

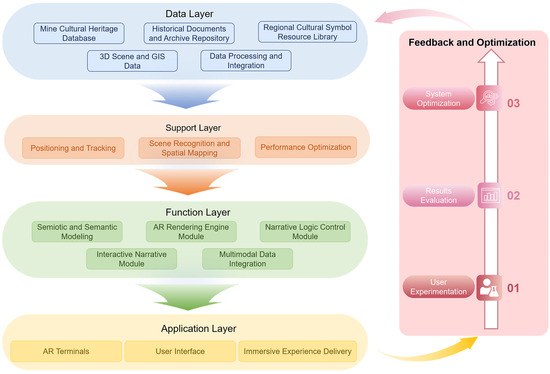

By integrating the technical implementation with visual narrative strategies, the system achieves stable operation, effective visualization, and contextualized storytelling under complex underground conditions, establishing a solid foundation for subsequent user experiments. As shown in Figure 7, a comprehensive framework is constructed, consisting of a data layer, support layer, functional layer, and application layer, combined with a feedback loop of user testing–result evaluation–system optimization to enable dynamic improvement driven by user experience. This framework not only delineates the complete chain from cultural resource acquisition to immersive interactive output but also provides a structured foundation for future system expansion and refinement.

Figure 7.

System Architecture and Iterative Optimization Framework. Layered AR system architecture comprising data, support, function, and application layers, together with a feedback and optimization mechanism based on user experimentation and results evaluation.

To ensure that the technical components directly support narrative expression, cultural-semantic elements are embedded at each layer of the system framework. Stable SLAM positioning anchors narrative nodes to spatially meaningful locations, low-light adaptation ensures the visibility of symbolic artifacts, and efficient rendering maintains the smooth unfolding of cultural scenes. Together, these integrations enable the system to function not merely as a technical platform but as a medium that reconstructs mining memory, spatial atmosphere, and historical continuity in immersive form.

4.2. User Experiment Design and Data Processing

Before conducting group comparisons, the internal reliability of the measurement scales was examined. Cronbach’s α values were 0.86 for immersion, 0.82 for cultural identity, and 0.89 for learning assessment, indicating good internal consistency.

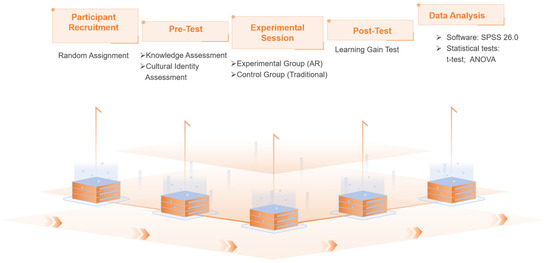

4.2.1. Experimental Design

The experiment consists of three main stages: ① Pre-test stage—After signing the informed consent form (Appendix A), participants provide demographic information and complete baseline questionnaires on immersion and cultural identity (Appendix B and Appendix C) as well as a knowledge test on abandoned mines (Appendix D). ② Implementation stage—Two groups are exposed to either a traditional static display or an AR-based immersive visual narrative experience. ③ Post-test stage—Participants complete the same immersion and cultural identity scales and the knowledge test again, and additionally fill out a system usability and overall satisfaction assessment (Appendix E) to evaluate the AR system’s performance in interactive experience and overall acceptance. Before the experimental tasks began, all participants were required to demonstrate basic ICT literacy, such as operating smartphones and touchscreen interfaces. Prior AR experience was not necessary, as a brief standardized orientation was provided to ensure that all participants were familiar with the basic AR interaction procedures. Baseline equivalence was ensured through pre-test knowledge scores, which indicated no significant differences between groups. Participants’ prior familiarity with mining culture was recorded and controlled during analysis. All testing procedures were conducted under identical environmental conditions to minimize external variability. The complete experimental procedure is illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Workflow of the User Experiment. Experimental design and sampling procedure for evaluating AR-supported learning and cultural identity, including participant recruitment, grouping, assessment, and statistical analysis.

The data analysis follows a standard statistical procedure. Normality is tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and homogeneity of variance is assessed with Levene’s test. When the assumptions are met, paired-sample and independent-sample t-tests are applied; when violated, Welch’s correction or nonparametric tests are used. The significance level is set at α = 0.05, with two-tailed p-values, effect sizes (Cohen’s d), and 95% confidence intervals reported. Environmental factors, device settings, and task sequences were standardized across sessions to ensure that between-group differences stemmed from narrative modality rather than contextual variation.

4.2.2. Experimental Results

Before presenting the experimental outcomes, the demographic characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table 1 to provide context for subsequent comparisons.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants (N = 62).

- Immersion

The immersion scale includes three dimensions: presence, realism, and interactivity (see Appendix A). A detailed breakdown of immersion performance across these three dimensions is presented in Table 2, allowing for a clear comparison between the two groups. The AR group scores significantly higher than the traditional display group on presence (M = 4.35, SD = 0.62), realism (M = 4.20, SD = 0.71), and interactivity (M = 4.45, SD = 0.58), compared with mean scores of approximately M = 3.7 in the control condition. An independent-samples t-test on the total immersion score shows a significant difference, t(60) = 3.92, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.87. These results indicate that the AR system maintains stable spatial rendering and interactive performance under challenging conditions such as low illumination and enclosed spaces, thereby providing a higher level of immersion.

Table 2.

Immersion results (5-point Likert scale).

- 2.

- Cultural Identity

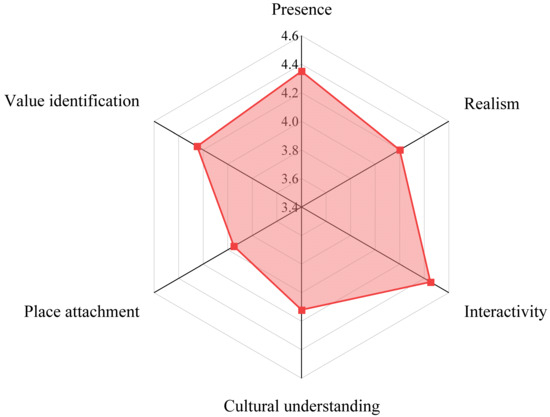

As shown in Table 3, the three cultural-identity dimensions—cultural understanding, place attachment, and value identification—differ notably between the two groups.

Table 3.

Cultural identity results (5-point Likert scale).

Figure 9 provides a visual comparison of presence-related responses and cultural-identity indicators between the two groups, complementing the statistical results.

Figure 9.

Comparison of presence and cultural-identity indicators between the two groups.

Overall, cultural identity scores were consistently higher in the AR group across all three dimensions, with value identification showing the largest difference between groups (t = 4.16, p < 0.001). These results suggest that AR-based spatial storytelling strengthens emotional connection and cultural recognition.

- 3.

- Learning Gain

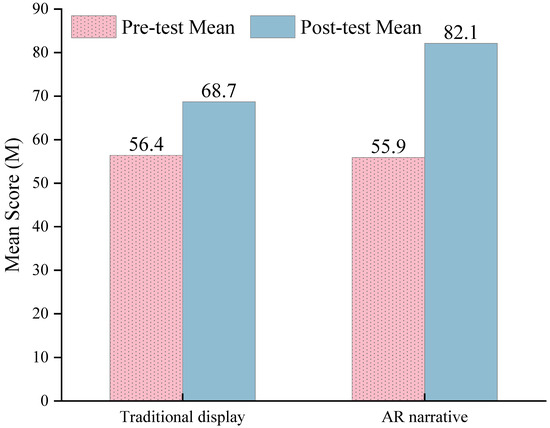

Independent-samples t-tests indicated significantly greater learning gains in the AR group compared to the traditional display group, t (60) = 7.21, p < 0.001 (see Table 4 for detailed statistics). Trends are visualized in Figure 10.

Table 4.

Learning gain results.

Figure 10.

Experimental Results of Learning Gain.

4.3. Results Analysis and Practical Implications

The AR visual narrative system demonstrates clear advantages across the three core dimensions of immersion, cultural identity, and learning gain.

- Immersion

Under low-light and spatially complex underground conditions, the system maintains stable visual rendering and smooth interaction flow through low-light adaptation and spatial relocalization technologies, resulting in high levels of presence, realism, and interactivity. These patterns align with spatial presence theory, which emphasizes that stable perceptual cues and coherent narrative progression strengthen users’ sense of “being there.” The system’s enhanced tracking minimizes disruptions, enabling the mine environment to be perceived as a continuous narrative space.

- 2.

- Cultural Identity

Analysis of cultural identity shows that visual symbol–based storytelling effectively integrates mining relics, process symbols, and local memory, enhancing participants’ understanding of historical value and regional culture while strengthening emotional connection. Cultural memory theory suggests that symbolic cues—such as artifacts, geological textures, and reconstructed historical scenes—serve as mnemonic triggers that help users reconstruct collective memory. Anchoring these cues spatially within the original mining setting facilitates deeper place attachment and value identification.

- 3.

- Learning Gain

The AR scene-based presentation not only improves knowledge acquisition efficiency but also supports information retention and cognitive transfer. This is consistent with dual-coding and contextual learning theories, which argue that learning improves when verbal information is paired with spatially meaningful visual representations. By embedding historical processes and cultural narratives within an embodied spatial experience, the system enables multi-channel encoding and deeper conceptual integration.

- 4.

- Practical and Research Implications

Our findings echo a trend that has been noted across recent AR heritage studies: when cultural symbols, spatial cues, and narrative content are presented within an immersive environment, users tend to show deeper engagement and stronger cultural understanding. What distinguishes the present study is that similar effects were observed in an underground mine—a setting where low illumination, irregular geometry, and texture scarcity typically make coherent cultural interpretation difficult. The results suggest that AR can sustain meaningful storytelling even in spaces that are not traditionally suited for narrative communication.

The evidence also sheds light on how the proposed space–semantics–interaction framework functions in practice. Rather than relying on technical optimization alone, the system blends layered visual information with spatially meaningful interaction paths and culturally grounded symbolic elements. This combination supports a form of immersion that is not only sensory but interpretive, enabling users to connect the visual narrative with regional cultural memory. Such integration offers a practical foundation for future applications in heritage education, cultural exhibition, and the adaptive reuse of industrial sites.

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

- (1)

- This research advances the digital regeneration of abandoned mines by establishing a space–symbol–memory coupling framework grounded in regional culture. Building on spatial narrative theory and visual communication approaches, the study constructs a narrative model that links cultural imagery, local memory, and contextual sense of place. Unlike existing digital-heritage methods that separately address geometric recording or symbolic interpretation, the proposed framework integrates spatial structure, cultural symbols, and memory formation into a coherent mechanism, reducing fragmentation in current industrial-heritage digitization practices. This conceptual model therefore broadens the theoretical basis for interpreting concealed or inaccessible cultural spaces.

- (2)

- An AR-based visual narrative system adaptable to the extreme conditions of underground mines is developed to address challenges such as low illumination, complex spatial geometry, and frequent localization failure. The system enhances illumination robustness, optimizes SLAM-based positioning, and accelerates LOD rendering while establishing a four-layer technical architecture of data, support, function, and application. The evidence–experience–co-creation logic proposed in this study further extends existing AR narrative-design paradigms by clarifying how authenticity, situated interacdisangetion, and interpretive participation operate as interconnected mechanisms in underground heritage communication. This architecture closely integrates cultural semantics with immersive interaction, providing strong technical support for the deep reconstruction and dynamic storytelling of cultural scenes.

- (3)

- User studies show that the AR-based narrative experience offers significantly higher immersion, cultural identity, and knowledge acquisition compared with traditional static presentations. Participants reported stronger spatial presence and perceived cultural value, while knowledge assessments indicated improved understanding, motivation, and memory retention. Taken together, the results demonstrate that the proposed space–symbol–memory network effectively enhances regional cultural communication by enabling multi-path interpretation and fostering deeper emotional resonance—outcomes that conventional linear displays cannot achieve. This evidence provides a solid empirical basis for improving educational and cultural experience design in industrial-heritage contexts.

- (4)

- Although the AR system demonstrates strong cultural and educational value, the present study is constrained by a relatively small and geographically concentrated participant sample, as well as limited application scenarios. Future research should expand the scale and diversity of participants and include additional types of mining sites to more comprehensively evaluate the system’s robustness in complex underground environments. Moreover, integrating emerging technologies—such as AI-driven adaptive storytelling, multi-modal affective feedback (e.g., gaze, gesture, or bio-signals), and mixed-reality (MR) fusion for large-scale industrial-heritage clusters—may enable more personalized, emotionally responsive, and spatially coherent narrative experiences. In addition, as larger and more diverse samples become available, future studies may incorporate regression analysis or structural equation modeling to examine potential causal pathways.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.D. and Z.Y.; methodology, W.D.; software, W.D.; validation, W.D. and Z.Y.; formal analysis, W.D.; investigation, W.D.; resources, W.D.; data curation, W.D.; writing—original draft preparation, W.D.; writing—review and editing, W.D. and Z.Y.; visualization, W.D.; supervision, Z.Y.; project administration, Z.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because it involved anonymous, non-invasive questionnaire procedures with adult participants, and no personally identifiable in-formation was collected.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Informed Consent Form

Dear Participant,

You are invited to take part in an academic study that explores how an augmented reality (AR) visual narrative system for abandoned mines affects immersion, cultural identity, and knowledge dissemination. The findings are intended to support research and practice in the digital preservation of industrial heritage and public cultural education.

Study Procedures

- Participants are randomly assigned to one of two experience conditions: an AR scene or a traditional multimedia display.

- The session lasts approximately 20–30 min and includes a brief pre-experience questionnaire, an immersive scene experience, and post-experience scales, together with a knowledge test.

- Your responses are used solely for academic analysis and not for commercial purposes.

Risks and Discomforts

No significant physical risks are anticipated. Because the experience simulates a mine environment (e.g., low light and sound effects), mild discomfort may occur for some participants. You may stop at any time without penalty.

Voluntary Participation and Withdrawal

Participation is entirely voluntary. You may withdraw at any stage without providing a reason and without any adverse consequences. If you choose to withdraw, your data will not be collected or used.

Privacy and Data Protection

All collected data are processed anonymously. Only the research team has access to raw data. No personally identifying information appears in reports, publications, or publicly shared datasets. Data are encrypted and handled in accordance with research ethics requirements.

Contact Information

For any questions or concerns about the study, please get in touch with the principal investigator:

Name: __________________________

Email: __________________________

Phone: __________________________

By signing below, you confirm that you have read and understood the information above, that your questions (if any) have been answered, and that you voluntarily agree to participate.

Participant Signature: __________________________ Date: __________________

Principal Investigator Signature: ________________ Date: __________________

Appendix B. Immersion Scale

Please rate your experience with the AR system.

1 = Strongly disagree 5 = Strongly agree

Presence

B1. I feel as if I am physically present in a real mining environment.

B2. I feel able to move freely within the virtual mine space.

B3. I feel a genuine sense of spatial awareness in the surrounding environment.

B4. I feel that the objects and spaces in the system merge seamlessly with reality.

Realism

B5. The mining scenes presented by the system appear realistic and credible.

B6. Changes in lighting and shadows enhance the sense of realism in the environment.

B7. The sounds match the visual content, making the environment feel more authentic.

B8. The integration of virtual elements with the physical space feels natural and coherent.

Interactivity

B9. I am able to explore content of personal interest through interaction.

B10. The system responds quickly and accurately to my actions.

B11. I can easily trigger or switch between different narrative content.

B12. My actions influence the information or pathways presented in the system.

Appendix C. Cultural Identity Scale

Please rate your cultural understanding and emotional connection during the experience.

1 = Strongly disagree 5 = Strongly agree

Cultural Understanding

C1. I gain a clearer understanding of the historical background of the mine.

C2. The system helps me understand miners’ working conditions and production processes.

C3. I learn about miners’ lifestyles and social culture.

C4. I recognize the mine’s impact on local economic and social development.

Place Attachment

C5. I feel a sense of familiarity or closeness toward the mining area.

C6. I feel an emotional connection with the place during the experience.

C7. I hope to visit or help preserve such mining heritage sites in the future.

C8. I develop a greater interest in the region’s industrial culture.

Value Identity

C9. I identify with the miners’ spirit of dedication and cooperation.

C10. I understand and respect the commemorative rituals associated with the mine.

C11. I believe that preserving and passing on mine-related culture is of great importance.

C12. I am willing to share the cultural information I experienced with others.

Appendix D. Knowledge Test

Please select the most appropriate answer for each question. Only one option is correct. (10 single-choice questions; total score = 100)

D1. The most common support structure used in abandoned mines is:

A. Reinforced concrete arch B. Rock bolts and mesh

C. Wooden support frame D. Plastic panel

D2. The facility most commonly used to maintain airflow and ensure safety in mines is:

A. Drainage ditch B. Ventilation shaft tower

C. Rail sleeper D. Belt conveyor

D3. The primary geological safety hazard that often occurs after a mine is sealed is:

A. Rock weathering B. Rising groundwater

C. Roof collapse D. Gas accumulation

D4. Workers’ rituals or ceremonial activities in mining culture primarily symbolize:

A. Production efficiency B. Safety and solidarity

C. Technological innovation D. Economic benefits

D5. In mining culture, the “miners’ lamp” mainly symbolizes:

A. Light and safety B. Wealth and prosperity

C. Leadership and power D. Technological development

D6. The primary function of mine rail sleepers in the underground space is:

A. Transport support B. Moisture and heat insulation

C. Preventing collapse D. Direction marking

D7. A common safe practice mentioned in miners’ oral histories is:

A. Acting alone B. Randomly removing supports

C. Following team-based collaboration D. Entering without lighting

D8. One key value of reusing abandoned mines is:

A. Tourism only B. Cultural heritage preservation and education

C. Waste disposal D. Real estate development

D9. The main function of AR technology in industrial heritage is:

A. Gaming and entertainment

B. Information overlay and immersive storytelling

C. Mining operations monitoring

D. Maintenance of mining machinery

D10. Which of the following helps improve users’ sense of safety in a mine AR system?

A. Complex light and shadow changes

B. Layered information display and real-time prompts

C. Random content triggers

D. Reduced system interactivity

Appendix E. System Usability and Overall Satisfaction Scale

Please rate your experience using the system.

1 = Strongly disagree 5 = Strongly agree

E1. I want to use this system frequently.

E2. I find this system unnecessarily complex. (reverse-coded)

E3. I find this system easy to use.

E4. I need technical support to be able to use this system. (reverse-coded)

E5. I find the system’s various functions well integrated.

E6. I find too much inconsistency in this system. (reverse-coded)

E7. I believe most people would learn to use this system very quickly.

E8. I find the system cumbersome to use. (reverse-coded)

E9. I feel confident when using this system.

E10. I need to learn a lot before I can use this system. (reverse-coded)

References

- Dai, X.Y.; Que, W.M. Temporal-spatial distribution of mining heritages in China: The perspective of officially protect-ed site/entity. Geogr. Res. 2011, 30, 747–757. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=ewTrO3D4JaPeNm4GgIIi0jDtwib4Yq2cdcjOqp_Jy7NxI9dvmxdSUF9xuGC6wD8jYn-oSJMdD22RNPWuZf37_pYbrSNcc-hrBJdNtTlGO52t98orC8VsdwsscqSmIm7Qwo8eY6XIQljB-HEXfSq755EHtXXL95Et9MYPomABtxkE9ElJVWteXw==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 3 December 2025). (In Chinese).

- Measham, T.; Walker, J.; McKenzie, F.H.; Kirby, J.; Williams, C.; D'URso, J.; Littleboy, A.; Samper, A.; Rey, R.; Maybee, B.; et al. Beyond closure: A literature review and research agenda for post-mining transitions. Resour. Policy 2024, 90, 104859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bainton, N.; Holcombe, S. A critical review of the social aspects of mine closure. Resour. Policy 2018, 59, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagouni, C.; Pavloudakis, F.; Kapageridis, I.; Yiannakou, A. Transitional and post-mining land uses: A global review of regulatory frameworks, decision-making criteria, and methods. Land 2024, 13, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.Z.; Ding, K. Community Renewal from the Perspective of Industrial Heritage Transformation and Reuse. Inter. Archit. China 2025, 10, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, X.M. The primary study of exploitation of industrial heritage tourism in resource-based city: A case study of Haizhou Strip National Mine Park. Urban Dev. Stud. 2010, 17, 90–94. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=ewTrO3D4JaPsx_EsP6-eVuP1OaQayJROKN-wFJkuYDAfjIl-xs9NLh5r_K-ahY-rpH7pV76O9hsPwkmKF2fglRAb-b_EJhFFiGjT-akk5SaKfHy0y28RWAfOzG-6WLVTtBfS1myo8R_zOT2OynpSdoTKGdziyrqQySOwtxhd4zmhqGqPBWDSlg==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 3 December 2025). (In Chinese).

- Han, Y. Construction and Application of a Feasibility Evaluation Model for Tourism Resources Development in Abandoned Underground Mines. Master’s Thesis, Anhui University of Science and Technology, Huainan, China, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.Q. Research on Evaluation Models for Abandoned Coal Mine Reutilization and Their Applications. Ph.D. Thesis, China University of Mining and Technology, Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.Y. Design of Abandoned Mine Underground Space Oriented by Experiential Industrial Tourism. Master’s Thesis, China University of Mining and Technology, Xuzhou, China, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.Y.; Fei, X.; Zhu, S.H. Renewal design strategy of Hengyang City industrial heritage based on regional culture. Screen Print. 2025, 11, 123–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, S.; Davies, P.; Hil, G.; Rutherfurd, I.; Grove, J.; Turnbull, J.; Silvester, E.; Colombi, F.; Macklin, M. Characterising mine wastes as archaeological landscapes. Geoarchaeology 2023, 38, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratisto, E.H.; Thompson, N.; Potdar, V. Immersive technologies for tourism: A systematic review. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2022, 24, 181–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiee, M.; Esmaeelbeigi, F. Viewpoints on AR and VR in heritage tourism. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 2024, 33, e00333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z. Prospects for value creation of virtual reality and augmented reality technologies. Ind. Innov. 2025, 12, 100–102. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=ewTrO3D4JaNb6UvmYuuOhyoecGVvwNAt9-Q5wb-ikXn6YQJHNq9wZQDn1E4UQ6XKevhX49GWuPZNKGXby7mo77rj2E8bohKpW28uxw680PzlkDgrwWOJRwhSpL8WdmIY-CQZ2M8x-ShXfp2rPUNkgugStn8eIC4tnp1vCHLBkMWY7MmLs-e2XA==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 3 December 2025). (In Chinese).

- Zhuo, F.; Han, G.Q.; Yi, X.W. Text interpretation and visual narration: Application of orientation tracking AR technology in the visual design of cultural heritage districts. Masterpieces Nat. 2024, 31, 39–43. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=ewTrO3D4JaOI43wGia2vNDgAKI5LQsbTQBMKZ9RSciuVENY1KWJl7oKBQqaEZNhua3_WbxJSrwLdwBsf7iWjxDdwbRagnkd3SkHExQDJzHZoV-tjzom3YpFUGnLbGG6_ybTFxMuAlVAMxKg8NbNL4M--_9z233D1SDis55T6kAPun6nJePdzjA==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHSCHS (accessed on 3 December 2025). (In Chinese).

- Hu, J. Individually integrated virtual/augmented reality environment for interactive perception of cultural heritage. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2024, 17, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.O. Creative expression and immersive experience in the integration of AR technology and visual communication design. Art Panor. 2024, 11, 22–24. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=ewTrO3D4JaMtcMq4sq-lJByxVIbQDpaPyM5reivHf3r24_ZBWbm651HEDZISyJ_2Moq2CRs6GGzus6COSZldvBpguS5nKsO4CJPVxGqQca0nR8uAQM9YmrzdKqWPk_auTnOeB8bfxvr7g9PGVOOfCE48Rs_K2a6Lxyd79Oskf0I9Elm8nw9W3A==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 3 December 2025). (In Chinese).

- Qiu, L.L. Digital protection of cultural heritage: The application and challenge of AR technology in traditional art exhibitions. Shoes Technol. Des. 2024, 19, 20–22. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=ewTrO3D4JaNZK8qStyB5RDt1_fWUxVxpZRQNtUKWGGkqKFYnXhalX9v4UIkf_qqpaMMWpqbqJPOkFaOy_NIjRLtWhttrhTeICOfEf_G5WiHZQ5aXHIy-iHIqWRCA8g6oDKk97QDhBkFhbzS-u_qXoBpBwQTHJtLhfNzZJfu9TiUAf2p99g4ONA==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 3 December 2025). (In Chinese).

- Williams, M.; Yao, K.K.K.; Nurse, J.R.C. ToARist: An augmented reality tourism app created through user-centred design. In Proceedings of the 31st International BCS Human Computer Interaction Conference (HCI 2017), Sunderland, UK, 3–6 July 2017; BCS Learning and Development: Swindon, UK, 2017; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Le, B.; Wang, L. Why people use augmented reality in heritage museums: A socio-technical perspective. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M.L. Narrative as Virtual Reality 2: Revisiting Immersion and Interactivity in Literature and Electronic Media; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, J.Q. Narratology: An Introduction to Narrative Theory; Beijing Normal University Press: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L.J. The Uses of Heritage; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Champion, E.M. Critical Gaming: Interactive History and Virtual Heritage. In Proceedings of the Digital Heritage 2015, Granada, Spain, 28 September–2 October 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:115015333 (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Douet, J. Industrial Heritage Re-Tooled: The TICCIH Guide to Industrial Heritage Conservation; Carnegie Publishing: Lancaster, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kan, Y.X. Research on Renewal Design of Industrial Heritage Under Scenario Theory—Taking JinanYuanshou Knitting Factory as an Example. Master’s Thesis, Shandong University of Art & Design, Jinan, China, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.Y. Dream Core Aesthetics: A Study of Transmedia Symbols and Visual Expression from the Perspective of the Birmingham School. Ph.D. Thesis, Tianjin Academy of Fine Arts, Tianjin, China, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Y.; Shang, X.Y. Research on the application of AR technology in Middle East Railway heritage protection: A case study of the South Line. Study Nat. Cult. Herit. 2018, 6, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Peng, X.; Wang, Y.; Fan, W.; Wang, K.; Du, Y. Adopting AR wayfinding in heritage tourism: Extending the UTAUT in cultural contexts. Npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Vecchio, V.; Lazoi, M.; Marche, C.; Mettouris, C.; Montagud, M.; Specchia, G.; Ali, M.Z. Designing innovative digital solutions in the cultural heritage and tourism industry: Best practices for an immersive user experience. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, B.; Ito, H.; Zhang, T. Architectural influence on narrative content in cultural heritage projection mapping. Npj Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.; Nam, K.; Dutt, C.S. A user experience perspective on heritage tourism in the metaverse: Empirical evidence and design dilemmas for VR. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2023, 25, 265–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.; Nam, Y. Do presence and authenticity in VR experience enhance visitor satisfaction and museum revisitation intentions? Int. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 26, e2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.I.D.; Tom Dieck, M.C.; Jung, T. Augmented reality smart glasses (ARSG) visitor adoption in cultural tourism. Leis. Stud. 2019, 38, 618–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Yoon, J.; Kwon, J. Impact of Experiential Value of Augmented Reality: The Context of Heritage Tourism. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavián, C.; Ibáñez-Sánchez, S.; Orús, C. The impact of virtual, augmented, and mixed reality technologies on the customer experience. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 100, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Baek, J.; Park, S. Review of GIS-based applications for mining: Planning, operation, and environmental management. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Abd El-Aziz, A.; Elwageeh, M. Optimization of escape routes during mine fire using GIS. Min. Technol. Trans. Inst. Min. Metall. 2023, 132, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şalap-Ayca, S.; Karslıoğlu, M.O.; Demirel, N. Development of a GIS-based monitoring and management system for underground coal mining safety. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2009, 80, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavelka, K.; Beloch, L.; Pavelka, K., Jr. Modern methods of documentation and visualization of historical mines in the UNESCO mining region in the Ore Mountains. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2023, X-M-1, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makkonen, T.; Heikkilä, R.; Jylänki, J.; Fraser, S. Reopening an abandoned underground mine—3D digital mine inventory model from historical data and rapid laser scanning. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Symposium on Automation and Robotics in Construction and Mining (ISARC 2015), Oulu, Finland, 15–18 June 2015; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, J. An overview of GIS-based assessment and mapping of mining-induced subsidence. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boboc, R.G.; Băutu, E.; Gîrbacia, F.; Popovici, N.; Popovici, D.M. Augmented reality in cultural heritage: An overview of the last decade of applications. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanvi, P.; Derek, B.; Eleni, T. Augmented reality and experience co-creation in heritage settings. J. Mark. Manag. 2023, 39, 470–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusaporci, S.; Maiezza, P. Smart architectural and urban heritage: An applied reflection. Heritage 2021, 4, 2044–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).