Abstract

Landfills situated in karst terrains pose unique sustainability challenges due to the complex geological characteristics of these environments. This is mainly due to the well-developed underground drainage systems, including discontinuities and caves that can quickly transport contaminants over long distances, reaching the water sources and ecosystems. The focus of this study is on multi-geophysical assessment incorporating electrical resistivity tomography (ERT) and seismic refraction tomography (SRT) to evaluate the volume of the waste and to delineate the contact between the waste material and the karst, offering a more comprehensive view of subsurface conditions. The presented examples include geophysical mapping of the landfills Sodol and Sorinj, situated in the immediate vicinity of sensitive water bodies, increasing the potential risk of environmental contamination. At both sites, the boundary between waste material and bedrock was clearly delineated. Bedrock was identified with P-wave velocities of approximately 3000 m/s at Sodol Landfill and 2000 m/s at Sorinj Landfill. Waste material, observed at both sites, exhibited electrical resistivity values up to 120 Ω·m. The combined use of ERT and SRT provides extensive coverage of the landfill area, surpassing what can typically be achieved through traditional methods such as boreholes or excavations. Overall, the obtained results show promising potential for using integrated geophysical methods to accurately characterize landfill sites in karst terrains, thereby improving environmental protection strategies in karst regions and contributing to sustainable waste management.

1. Introduction

The remediation of municipal solid waste landfills requires a thorough understanding of the waste composition, the quantity of disposed material, as well the geological structure of the ground upon which the landfill is situated. One of the most significant challenges associated with older landfills is the generation and percolation of leachate into the subsurface. In the absence of a properly constructed barrier system, leachate can become a major environmental contaminant, potentially affecting areas below as well beyond the landfill boundary. This issue is particularly pronounced in landfills located in karst terrains [1,2], where the depth to bedrock and the presence of fractures, or karst voids, must be identified. To achieve a broader and non-destructive assessment of subsurface conditions, especially in complex settings like karst terrains, geophysical methods offer significant advantages. The necessity of applying geophysical methods arises from the fact that landfill investigations traditionally rely on only a few boreholes, which provide highly localized, point-based information. In karst terrain, characterized by extreme geological variability, this means that most of the subsurface remains essentially unknown. Non-destructive geophysical techniques therefore offer a critical advantage, as they allow the spatial characterization of karst features such as sinkholes, cavities, and major fracture zones that are easily missed by drilling. By mapping variations in seismic velocity and electrical resistivity, these methods provide a continuous spatial framework that enables a far more reliable interpretation of subsurface conditions than borehole data alone.

The use of geophysical techniques to investigate karst terrains is well established, with numerous studies demonstrating their effectiveness in mapping complex subsurface features. Techniques such as gravity, seismic, electrical, and electromagnetic methods have all been successfully applied, as summarized in a comprehensive review by Chalikakis et al. [3]. However, despite advancements in technology and more accessible field procedures, interpreting geophysical data in karst environments remains a challenge due to the inherent complexity and heterogeneity of these systems [4].

These geophysical tools are equally relevant in the context of landfill characterization. Various geophysical methods have also been successfully applied to landfill characterization, as given in a review by Morita et al. [5]. Electrical methods, in particular, have proven effective in detecting variations in subsurface properties, especially moisture content and leachate movement [6]. Depending on the goals of the study, seismic [7] and electromagnetic [8] methods have also been employed with good results. A detailed SWOT analysis of geophysical techniques in landfill investigations is provided by the Interreg RAWFILL project report [9], which outlines their strengths and limitations in various settings.

When landfills are located in karst regions, the challenges multiply. Karst terrains often contain hidden voids, conduits, and unpredictable porosity patterns, all of which can accelerate leachate migration. As a result, many studies have focused on case-specific assessments tailored to local geological conditions. In northern Italy, for example, electrical resistivity tomography (ERT) is used to reveal large karst cavities beneath a landfill near Asiago, helping to assess the risk of leachate leakage and inform closure strategies [10]. Similar concerns about leachate behavior in complex karst systems led to the application of magnetotelluric imaging in the Garraf Massif of Spain’s Catalan Coastal Ranges, where the method is used to trace subsurface contamination pathways [11]. In Kentucky’s karst region, ERT is employed to guide landfill siting decisions, where authors conclude that application of ERT decreases landfill siting risks, saving time, money and most importantly, provides more protection for karst groundwater resource [12].

Given the limitations of using ERT alone, particularly its sensitivity to moisture, which can obscure bedrock boundaries, researchers have increasingly adopted a multi-method approach. Combining ERT with Multichannel Analysis of Surface Waves (MASW) has become a common strategy, especially in regions where saturated waste complicates resistivity readings. This integrated approach is used in Missouri to investigate the subsurface beneath a solid waste site, where MASW helped to clarify the geological setting by reducing the influence of water on resistivity measurements [13]. In further work in the region [14], ERT and MASW are complemented with borehole data and geomechanical tests to identify karst features that could pose structural risks. The study noted that discrepancies between geophysical and borehole data increased with depth, likely due to uneven moisture distribution affecting resistivity measurements. A multi-method approach also proved effective at a rehabilitated landfill site in Kneginec Gornji, Croatia, where ERT, MASW, microseismic noise measurements, and ground-penetrating radar (GPR) are used together to define both the landfill structure and its contact with the rock mass [15]. The results are most reliable in areas with low moisture content, where the methods yielded consistent results. Finally, research linking ERT with Seismic Refraction Tomography (SRT) has shown that combining resistivity and P-wave velocity data can help identify groundwater levels, particularly when resistivity decreases and seismic velocities increase, indicating saturated zones [16]. All these studies underscore a clear research trend: as the limitations of single-method approaches became evident, multi-method strategies emerged as a robust solution for both mapping subsurface structure and managing environmental risks in karstic and landfill contexts. This trend reflects a broader shift in the field toward complementary methods that leverage the strengths of different geophysical signals to produce more accurate and spatially extensive subsurface models. Collectively, these developments provide a clear trajectory: from isolated, method-specific studies toward integrated, multi-parameter geophysical approaches capable of addressing the complexities of karst terrains and landfill sites.

Since the seismic methods and ERT classify the subsurface based on parameters that differ significantly between disposed waste, the leachate zone, and the ground below, they are commonly selected for use in the specific investigations of landfills located in karst terrain. SRT provides a 2D model where it is expected that the P-wave velocities in the waste body are significantly lower than those in the carbonate bedrock, allowing for a clear identification of the transition zone where velocities increase. ERT produces a 2D model where it is assumed that the waste material shows elevated and highly heterogeneous resistivity values, the leachate zone exhibits very low resistivity, and the carbonate bedrock has high resistivity. Therefore, although SRT effectively distinguishes low-velocity waste deposits from the significantly higher velocities of the underlying bedrock, it is not the optimal standalone method for detailed characterization of landfill internal structure. This limitation arises because the range of P-wave velocities within the waste body is relatively small, while ERT is far more sensitive to changes in moisture content, pore fluid conductivity, and material composition, enabling clearer identification of leachate-rich zones, variations in waste degradation, and internal layering. For this reason, SRT is used primarily as a complementary method to ERT, as its strength lies in accurately mapping the waste–bedrock interface, while ERT provides the detailed imaging needed to evaluate the internal heterogeneity of the landfill.

In light of the multi-geophysical developments, this study addresses two key unresolved issues: (1) whether an integrated ERT–SRT approach can more reliably delineate the contact between waste material and karst bedrock than single-method geophysical surveys, particularly under conditions of elevated moisture that influence both waste and karst electrical resistivities and seismic velocities, and (2) whether combining resistivity and P-wave velocity data improves the estimation of waste volume and the identification of karst features that may influence leachate pathways. These hypotheses form the scientific basis for the methodological framework applied in the present study. The objective of this study is to apply a multi-geophysical approach to two landfill sites located in Croatia’s karst region, landfill Sorinj and landfill Sodol.

2. Methodology and Methods

2.1. Methodology Framework

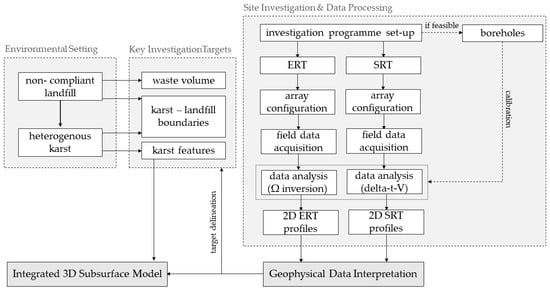

The methodological framework, Figure 1, applied in this study integrates targeted site investigation, geophysical surveying, data processing and data interpretation to develop a comprehensive model of a non-compliant landfill located within a heterogeneous karst environment. The process begins with defining the environmental setting, where the combination of landfill materials and irregular karst geology creates complex subsurface conditions. From this context, the main investigation targets are established, including the estimation of waste volume, the delineation of boundaries between landfill deposits and surrounding karst formations, and the detection of karst features. These targets inform the design of the geophysical data acquisition program.

Figure 1.

Workflow of the Integrated ERT–SRT Approach for Landfill Characterization.

The site investigation integrates ERT–SRT complementary geophysical methods. Survey line placement and array configurations for both methods are adapted to local site conditions, the expected depth of investigation, and the spatial resolution required to address the defined targets. Field data acquisition follows established quality-control protocols to minimize noise and ensure consistency across datasets. Where available, borehole information is incorporated into the investigation to provide ground truth for calibrating geophysical interpretations.

Following acquisition, the geophysical datasets undergo dedicated processing workflows. ERT measurements are inverted to produce two-dimensional resistivity profiles that reveal variations between landfill material and karst rock, potential voids, and moisture-rich zones. SRT travel-time data are processed to generate corresponding velocity profiles, supplying mechanical property information that complements the resistivity results. The set of processed 2D profiles forms the basis for an integrated interpretation. Interpretation combines ERT and SRT results with borehole information, when available, to addresses key unresolved issues. The interpreted datasets are subsequently synthesized into a coherent three-dimensional subsurface model, which supports the evaluation of environmental risks and informs future site management or remediation strategies.

2.2. Geophysical Methods Utilized

2.2.1. Seismic Refraction Tomography

Seismic Refraction Tomography (SRT) works by measuring how elastic seismic waves refract as they pass through different layers underground. This happens when the wave moves from a layer with a lower velocity (V1) to a layer with a higher velocity (V2). An elastic wave is generated at the surface and initially propagates through the upper layer at velocity V1. The key component of this method is the wave that reaches the interface at the critical angle (or angle of total reflection). At this angle, the wave continues to travel along the boundary at the higher velocity V2 and returns at the surface (according to Huygens’ principle), where its arrival is recorded by geophones. By analyzing the geometry of the geophone layout and shot points, along with the recorded first arrival times, Distance vs. Time diagrams, so-called dromochrones, are constructed. Using inverse modeling techniques, these travel-time curves are then interpreted to determine the depths and spatial distributions of elastic discontinuities within the subsurface. One such inverse modeling technique, utilized in this study, is the Delta-t-V method [17] which assumes a gradual change in seismic velocity with increasing depth. Unlike traditional methods, which assume that first arrivals correspond to hypothetical, mathematically idealized refractor layers, the Delta-t-V method operates on the assumption that the velocity gradient within each individual layer is constant [18]. This approach makes it possible to detect velocity inversion zones, i.e., lower-velocity layers situated beneath higher-velocity layers, something that traditional, direct interpretation methods typically cannot identify. The ability of the Delta-t-V method to detect velocity inversions is especially valuable in karst settings, where low-velocity zones (e.g., air-filled cavities or highly weathered rock) may lie beneath more competent rock layers.

While the method is suitable for the profiling of the underlying karst rocks, SRT can also help delineate the boundaries of the waste body by identifying changes in seismic velocity between compacted waste, cover material, and lower geological layers. SRT is particularly effective for determining the thickness of waste deposits and the depth to bedrock, owing to the significant contrast in seismic wave velocities between these materials. The method provides high vertical resolution, as it is relatively insensitive to the dispersion and attenuation of seismic waves in the vertical direction [19]. In addition to vertical profiling, SRT can be used to assess the lateral extent of landfills. However, to accurately distinguish between subsurface materials that exhibit similar seismic velocities, such as waste, clay, sand, and gravel, it is often necessary to integrate this technique with complementary geophysical methods. Furthermore, since compressional (P) waves are transmitted through fluids, the method can also be employed to identify the position of the groundwater table [16]. RAWFILL project [9] notes that the SRT may be used, but not as a best approach, to evaluate the landfill composition/structure and the water content, marking the method as of second interest when it comes to landfill assessment. For this purpose, it should ideally be combined with other methods, such as Electrical Resistivity Tomography (ERT), to overcome its limitations and improve interpretive accuracy.

2.2.2. Electrical Resistance Tomography

Electrical Resistivity Tomography (ERT) is a geophysical method that measures how strongly the ground resists the flow of electric current. The method works by injecting electrical current into the ground through electrodes placed on the surface, and measuring the resulting voltage differences. From these measurements, the resistivity of underground materials can be calculated. In a standard 2D ERT survey, many electrodes are placed along a profile. Different electrode array configurations can be used depending on the survey goal, where the most common ones are: (a) Dipole–dipole; (b) Wenner and (c) Schlumberger. Current is sent through two of the electrodes, and voltage is measured between two others. This process is repeated across many combinations of electrodes to collect a large amount of data. By changing the spacing between the electrodes, measurements are taken at different depths, producing a detailed vertical and horizontal image of how resistivity varies underground, so-called pseudosection. The initial resistivity data do not directly show the true resistivity of waste material and underground layers. To obtain more accurate results, a mathematical process called inversion is applied. This involves dividing the subsurface into many small rectangular blocks and adjusting the resistivity values of these blocks to match the measured data as closely as possible. The most commonly used technique for this is the least-squares method, which reduces the difference between measured and calculated resistivity values [20,21].

ERT is considered as the first-order geophysical methods when it comes to landfill assessment, as it is valuable in identification of the composition/structure and water content [11], along with good vertical and horizontal resolution of the pseudosections. The method is effective in distinguishing between saturated and unsaturated zones within a landfill [22], as well as in determining the level of groundwater or leachate. It does have some limitations, such as requirement of a good electrical contact with soil, the fact that presence of geomembrane in landfill impedes electrical current flow, while the depth of investigation varies with the resistivity of media.

2.3. Investigation Configuration and Processing Parameters

Seismic Refraction Tomography (SRT) measurements were conducted with 24 channel PASI GEA-24 seismograph. Propagation of seismic waves were recorded with 10 Hz seismic geophones. As a source type 10 kg seismic hammer was used. On both Sodol and Sorinj landfills for SRT imaging 24 geophones were used, spaced five meters apart. Stack of five shots was determined to be enough to give good first brakes. 512 ms was used as recording length and sampling time was 0.125 ms. The collected seismic data were processed using the Delta-t-V method [17] in RAYFRACT software, version 3.33. [23]. Delta-t-V method was selected because it provides stable and reliable velocity models in highly heterogeneous landfill conditions, where strong contrasts between low-velocity waste and high-velocity karst bedrock must be accurately resolved. Its robustness to variable near-surface conditions and reduced sensitivity to small-scale lateral heterogeneity make it particularly suitable for producing dependable first-arrival–based velocity structures in this type of environment. For adequate linear interpolation Kriging method was used with error below 3%. In the inversion procedure, convergence was achieved when successive iterations produced less than a 5% change in the root-mean-square (RMS) travel-time misfit, and when no further reduction in the misfit was obtained without increasing model complexity. These criteria ensured a stable and geologically consistent velocity model.

Electrical Resistivity Tomography (ERT) measurements were conducted with PASI POLARES instrument. ERT surveys on both locations are conducted using the Wenner-Schlumberger array, with 32 electrodes spaced five meters apart. The Wenner–Schlumberger array was selected because it offers the best balance between vertical and horizontal resolution for imaging heterogeneous landfill conditions, while also maintaining a high signal-to-noise ratio. Pure Wenner arrays provide good vertical resolution but insufficient data density for resolving lateral variations typical of waste deposits, whereas Dipole–Dipole arrays offer better lateral resolution but are highly susceptible to noise in landfills, especially where metal, leachate, and variable compaction can degrade data quality. The Wenner–Schlumberger configuration combines the strengths of both arrays, producing a robust dataset with adequate depth penetration and sufficient lateral sensitivity to accurately delineate the waste body and its contact with the underlying bedrock. A five-meter electrode spacing was chosen as an optimal compromise between investigation depth, profile length, and resolution, allowing reliable imaging of the waste–bedrock interface while preserving data quality across both sites. The collected electrical resistivity data were processed using RES2DIN software, version 3.59 [24], which performs robust 2D inversion of apparent resistivity data using a smoothness-constrained least-squares algorithm, allowing stable recovery of subsurface resistivity distributions even in heterogeneous environments such as landfills. Its automatic optimization routines enable iterative refinement of the model until convergence is achieved, defined by minimal changes in RMS error between successive iterations, set in this study at 10%. This convergence values is deemed acceptable considering the complexity of the model.

3. Description of Case Study Locations

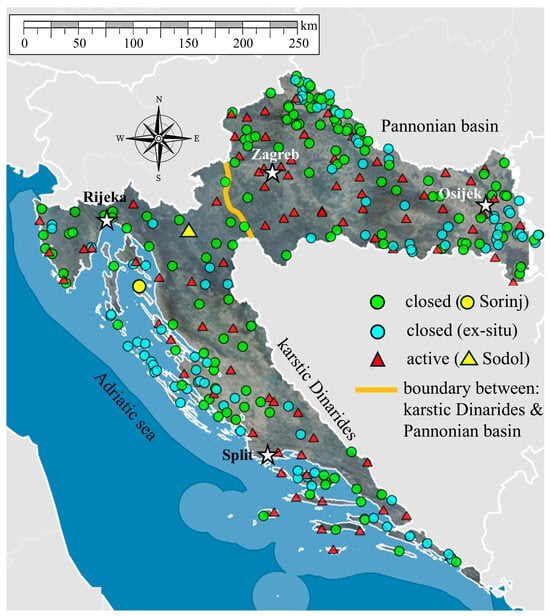

The objective of this study is to apply a multi-geophysical approach to two landfill sites located in Croatia’s karst region- landfill Sorinj and landfill Sodol (Figure 2). In these settings, geophysical methods serve to improve understanding of both the waste body and the underlying karstic subsurface, providing the information necessary for reliable characterization and interpretation within such complex environments.

Figure 2.

View on the case study landfills: (a) Sodol and (b) Sorinj (obtained from [25]).

Croatia is particularly relevant for such research, as approximately 50% of its land area is composed of karstic rock formations [26]. According to the most recent Eurostat data [27], Croatia continues to dispose a dominant share of municipal waste in landfills, with recycling rates being on the rise and only a small portion of waste being used for energy recovery. Despite gradual progress in separate waste collection, the overall proportion of recycled or valorized waste remains modest, while the share processed through waste-to-energy routes is minimal. Preferred alternatives such as anaerobic digestion [28], advanced mechanical-biological treatment [29], and thermal recovery technologies [30] remain underdeveloped or unevenly implemented across the country. These trends highlight the need for clearer strategic measures and stronger infrastructure investment to reduce reliance on landfilling. Consequently, landfills remain a central component of Croatia’s waste-management system and therefore a critical subject of technical assessment and environmental monitoring. According to the most recent data [31], 307 municipal landfills are located across the country, of which 77 are still operational and 230 have been closed, Figure 3. In many cases, these landfills were not developed through a formal planning process. Instead, natural karst features, such as sinkholes, small karst fields (poljas), and valleys, were commonly used as disposal sites. Over time, many of these informal dumps evolved into official municipal landfills. While some were later upgraded to meet minimal operational standards, they were not constructed in accordance with modern environmental regulations. As a result, the majority are now undergoing remediation and eventual closure. This situation highlights the urgent need for effective investigation and remediation methodologies specifically tailored to complex karst environments. Moreover, many of these landfills are situated in the immediate vicinity of sensitive water bodies, increasing the potential risk of environmental contamination. For example, the Sodol landfill is located near the Dobra River, a typical karst river characterized by sinking and resurfacing flows, which makes it particularly vulnerable to pollutants. Similarly, the Sorinj landfill lies just next to the Adriatic Sea, posing a direct threat to coastal and marine ecosystems.

Figure 3.

Location of landfills on the orthophoto map of Croatia, data based on [31] (green circles–closed landfills, blue circles–closed (ex situ) landfills, red triangles–active landfills).

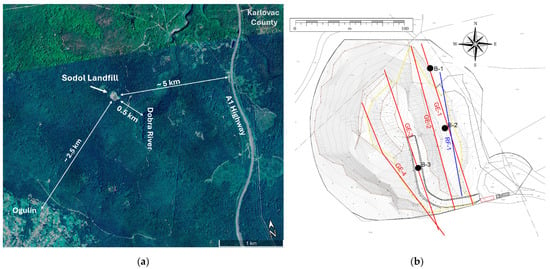

3.1. Description of the Sodol Landfill near Ogulin

The Sodol landfill is located in Ogulin, Karlovac County (Figure 4a). Geologically, wider landfill area is composed of Lower Cretaceous sediments. The waste was disposed into a karst sinkhole approximately 150 × 80 m in size and up to 50 m deep. The waste is scattered across the full depth of the sinkhole, particularly along its eastern side.

Figure 4.

Sodol landfill: (a) Microlocation of the landfill, (b) Layout of geophysical profiles (GE are ERT profiles, RF is SRT profile).

For the purposes of the remediation and, at later stage, closure of the Sodol landfill, it is essential to obtain reliable data on the volume of disposed waste and the condition of the underlying bedrock. Due to the unreliability of historical waste disposal records, in situ investigations are required. A combined approach using geophysical methods and exploratory drilling is selected, providing necessary data to develop a 3D model of the landfill. The methods applied included combination of SRT (one RF,115 m’, profile), ERT (four GE profiles, each 155 m’) and exploratory drilling (three boreholes–5 m, 23 m and 17 m). Figure 4b shows the layout of the geophysical profiles and boreholes. The length and positioning of the geophysical profiles are determined by the 30 m target investigation depth and field accessibility. Interpretation of the results is carried out by correlating the resistivity and seismic velocity values, characteristic of waste, leachate zones, and carbonate bedrock, with borehole data to ensure accurate classification of subsurface materials.

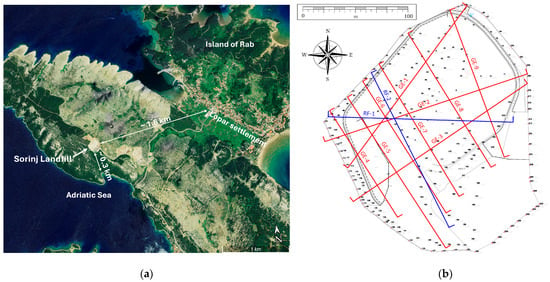

3.2. Description of the Sorinj Landfill on the Island of Rab

The Sorinj landfill is located on the island of Rab, within the municipality of Lopar, Figure 5a. The Sorinj landfill covers an area of about 34,000 m2 and has served as the official municipal waste disposal site for the island of Rab since 1969. Waste disposal at the site has been carried out in an unsanitary manner, with waste being dumped in an unmanaged area where no measures have been implemented to reduce its harmful environmental impact. The average elevation of the landfill is 103 m above sea level, with steep slopes on the western and southern sides. Some sections of the landfill are situated nearly directly on these slopes. The study area is predominantly composed of Cretaceous limestone and Paleogene (Eocene) marls. Here, the layers typically strike in the Dinaric direction (SI–JZ) with an inclination angle of 15–50 degrees. The southern part of the area is marked by a syncline, which contains younger deposits (marl) at its core, while older Cretaceous deposits are present on the flanks. To the northeast of the study area, a karstic bauxite formation, created by surface weathering of clay materials, has been observed.

Figure 5.

Sorinj landfill: (a) Microlocation of the landfill, (b) Layout of geophysical profiles (GE are ERT profiles, RF are SRT profile).

Geophysical investigations are carried out as part of the remediation project to obtain data on the volume of waste and the depth to the natural ground layer. A total of nine ERT (GE) profiles, with a combined length of 1534 m, and two SRT (RF) profiles, totaling 350 m, are recorded at the landfill site, Figure 5b. Profile placement is carefully selected to provide maximum coverage of the landfill area, taking into account accessibility and the practical constraints of deploying geophysical equipment.

4. Results of Geophysical Investigations

To facilitate a clear and structured interpretation of the geophysical investigation, the results are presented separately for the two landfill sites. Each subsection integrates ERT and SRT information to provide a comprehensive understanding of subsurface conditions and to highlight the specific geological and geomorphological characteristics of each location.

4.1. Results from Sodol Landfill

Based on the obtained resistivity and velocity values for Sodol landfill, a conditional material classification is developed, Table 1.

Table 1.

Classification of waste/soil/rock mass according to measured electrical resistivity values and measured P-wave velocities on the location of Sodol landfill.

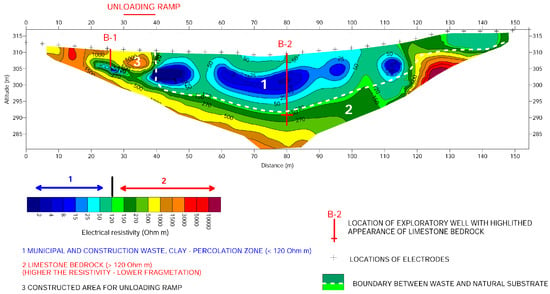

Figure 6 presents the results of ERT processing as a representative 2D cross-section (ERT Profile GE-1), illustrating subsurface variations in electrical resistivity with depth. The profile includes the locations of boreholes and provides an approximation of the boundary between the waste body and the underlying rock. The section reveals zones characterized by waste, rubble, clay, and leachate, exhibiting resistivity values of up to 120 Ω·m. These materials are primarily located between the 40 m mark and the end of the profile, extending to an average depth of approximately 13 m. Within this zone, resistivity values below 120 Ω·m reach depths of around 15 m, with the most prominent values observed in the central part of the profile, particularly at borehole B-2, where they extend to 17 m. In contrast, at the lateral edge of the profile (between 110 and 150 m), low-resistivity values are confined to a shallower depth of approximately 5 m.

Figure 6.

Sodol landfill interpreted ERT GE-1 profile.

Resistivity values exceeding 120 Ω·m are indicative of the underlying carbonate bedrock. These higher values suggest decreasing fracturing of the carbonate rock with increasing resistivity, marking the transition from weathered to more competent bedrock, typically located below an average depth of 13 m. At the beginning of the profile (0 to 40 m), a developed surface previously used as an unloading ramp for waste deposition is evident. Overall, the ERT data reflect significant heterogeneity in the subsurface, including varying extents of surface waste, zones of leachate accumulation, and differing depths to the bedrock interface. The resistivity profiles also suggest complex lithological conditions, with potential structural features such as fractures or fault zones and variable degrees of material degradation along the length of the profile.

Three exploratory boreholes are drilled at the landfill site as part of the field investigation. Boreholes B-2 and B-3, drilled to depths of 23 m and 17 m, respectively, are located within the landfill to determine waste thickness, while borehole B-1, drilled to 5 m outside the landfill, is used to assess the type and layering of the underlying soil. Borehole B-2 revealed a 19.3 m thick waste layer above fractured carbonate rock, consistent with the boundary shown on the geoelectrical tomography profile.

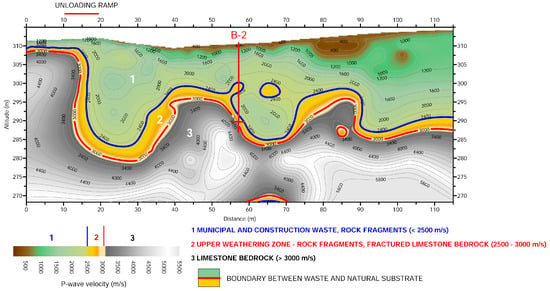

Figure 7 presents the seismic data processed into a depth cross-section, Profile RF-1, which illustrates the variations in P-wave velocity with depth. The interpreted 2-D profile reveals several key features. From the beginning of the profile to the middle of the unloading ramp (approximately 15 m), bedrock is expected at a depth of about 1.5 m, where seismic velocities exceed 2500 m/s, with overlying rubble and highly fractured rock. Between 15 and 35 m, the bedrock deepens to approximately 27 m. From 35 to 55 m, the bedrock is expected at a depth of around 10 m, after which it deepens again to about 25 m. At depths between 75 and 90 m, bedrock is anticipated around 10 m, and from 90 m to the end of the profile, it is expected to be at approximately 26 m.

Figure 7.

Sodol landfill interpreted SRT RF-1 profile.

The estimated waste volume at the Sodol landfill, based on pre-disposal terrain topography models, is approximately 77,000 m3. However, geophysical surveys indicate a larger volume of about 93,000 m3. Because the waste was deposited in a depression that terrain mapping methods could not accurately capture, and given the strong agreement between ERT results and exploratory drilling data, the waste volume determined through geophysical methods is considered more reliable than that estimated from spatial models.

4.2. Results from Sorinj Landfill

The interpretation of the geophysical survey results for Sorinj landfill are carried out by correlating the measured electrical resistivity and seismic velocity values, with characteristic of loose waste, leachate zones, and carbonate bedrock. Based on the obtained resistivity and velocity values, a conditional material classification is developed, Table 2.

Table 2.

Classification of waste/soil/rock mass according to measured electrical resistivity values and measured P-wave velocities on the location of Sorinj landfill.

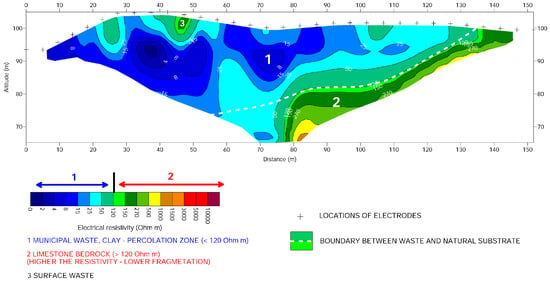

Figure 8 presents one representative ERT profile (GE-6), out of a total of nine profiles conducted. The profile extends 150 m and is positioned approximately parallel to the seismic refraction tomography profile (Figure 5b). Based on the measured electrical resistivity values, a distinct zone is identified corresponding to resistivity values typical of construction and municipal waste as well as clay (resistivity up to 120 Ω·m). This zone extends from the surface to an average depth of approximately 20 m. Resistivity values below 120 Ω·m are also recorded at depths greater than 20 m between 60 and 80 m along the profile, which may indicate a fractured zone with accumulated leachate. Resistivity values exceeding 120 Ω·m are interpreted as the carbonate bedrock, where increasing resistivity corresponds to a decrease in fracturing of the carbonate substrate. The bedrock generally occurs at depths greater than 20 m, though a shallowing of the bedrock is observed near the end of the profile, where the depth gradually decreases from around 20 m to the surface. This feature likely corresponds to the margin of the landfill site.

Figure 8.

Sorinj landfill interpreted ERT GE-6 profile.

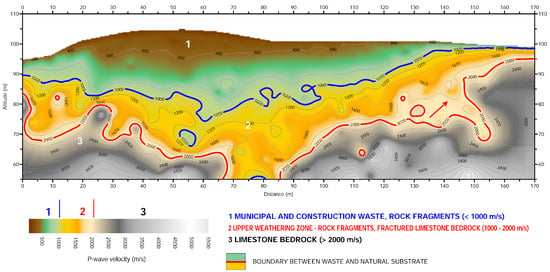

The seismic refraction profile RF-2 (Figure 9) extends over 170 m and is positioned approximately parallel to the electrical tomography profile (Figure 5b). On the interpreted profile, the boundary between the waste, including the leachate zone, and the underlying rock is delineated by a blue line. At this site, the rock mass corresponds to the upper weathering zone, composed of scree and highly fractured carbonate rock. The seismic wave velocities within the rock mass exceed 1000 m/s, with velocities above 2000 m/s indicating reduced fracturing and a more competent carbonate bedrock.

Figure 9.

Sorinj landfill interpreted SRT RF-2 profile.

5. Discussion

The ERT resistivity patterns on both Sodol and Sorinj landfill reflect real variations in waste thickness, moisture distribution, and leachate presence. The locally increased thickness of the low-resistivity zone likely reflects that more waste was deposited in this area. Likewise, the shallower waste layers correspond to thinner anthropogenic deposits. The ERT results from case study sites show several consistent patterns while also revealing distinct site-specific differences that reflect their subsurface conditions. In both profiles, resistivity values below approximately 120 Ω·m correspond to municipal and construction waste, clayey material, and leachate-rich zones. This similarity reinforces the reliability of this threshold for identifying electrically conductive waste deposits. Published studies [32,33,34] report that municipal solid waste typically exhibits low electrical resistivity, commonly in the range of a few tens of ohm-meters, particularly under moist or leachate-rich conditions. These values reflect the conductive nature of decomposing organic material and the presence of leachate. In our case, resistivities below approximately 120 Ω·m were interpreted as waste, which is consistent with the expected variability of MSW electrical properties. Such elevated upper-range values can occur where the waste is only partially saturated, where less conductive materials such as rubble, clay, or degraded construction debris are mixed within the deposit, where compaction or decomposition has altered pore structure, or simply due to the inherent heterogeneity of landfill material. This broader threshold therefore remains appropriate for capturing the full range of waste characteristics present at the study sites. Likewise, both sites exhibit a clear contrast between the relatively low resistivities of the waste body and the significantly higher values associated with the carbonate bedrock. Increasing resistivity with depth at both locations marks the transition from weathered and fractured bedrock to more competent carbonate units. This shared pattern is consistent with the expected geoelectrical behavior of karstified limestone, where voids, fractures, and weathered horizons contribute to heterogeneity in the resistivity distribution.

Despite these general similarities, the ERT results from two sites differ in several important ways. The most notable distinction is the thickness of the waste material. At Sodol, the waste layer commonly reaches depths of around 13 m, thickening locally to 17 m, but becoming significantly thinner toward the eastern margin, where it is only about 5 m. In contrast, the Sorinj profile reveals a substantially thicker waste zone, extending down to roughly 20 m along most of the profile. The presence of an additional low-resistivity anomaly below 20 m at Sorinj, particularly between 60 and 80 m, suggests either deeper leachate accumulation within a fractured bedrock zone or the presence of a subsurface depression that has been filled by more conductive material. Such a feature is not observed at Sodol, where conductive zones below the principal waste layer are limited in extent. This indicates that vertical leachate migration or deeper structural disruption may be more pronounced at Sorinj than at Sodol. The geometry of the waste–bedrock interface, determined through ERT, also differs between the two locations. At Sodol, the bedrock surface is highly irregular, with multiple undulations that reflect typical karst dissolution features such as pinnacles, pockets, and small depressions. The bedrock is generally encountered at shallower depths compared to Sorinj, averaging around 13 m but with local deepening beneath the thickest waste zones. By contrast, the Sorinj profile reveals a more uniformly deep bedrock surface, positioned near 20 m for most of the profile length, with a gradual rise toward the landfill margin.

The SRT results from the Sodol and Sorinj landfills display clear similarities in the way P-wave velocities reflect waste materials, fractured bedrock, and competent carbonate units, while also revealing important differences in the depth and structure of the bedrock surface beneath each site. Published studies on the seismic properties of municipal solid waste report a wide but characteristic range of P-wave velocities, generally spanning a few hundred to around 1000 m/s. A synthesis of eight landfill sites [35] shows that MSW typically exhibits velocities between roughly 500 and 1700 m/s, reflecting variations in compaction, degree of decomposition and waste composition. Another refraction study from [36] documented an P-wave velocity range of approximately 231–1160 m/s, further emphasizing the strong heterogeneity of waste materials. In our study, the observed low-velocity values assigned to the waste body fall within these published ranges and are therefore consistent with expected MSW elastic properties. Velocity variations within this interval may result from differences in saturation, the presence of rubble or construction debris and contrasting degrees of degradation and compaction. This variability is typical of landfills and reflects the highly heterogeneous mechanical behavior of municipal solid waste. At both case study locations, the seismic velocity distributions are consistent with typical carbonate karst environments, where strong lateral and vertical velocity contrasts reflect variations in rock quality, degree of fracturing, and the presence of voids or weathered zones. In each profile, relatively low velocities are associated with waste materials, loose deposits, and highly fractured rock, whereas higher velocities correspond to more intact carbonate bedrock. These relationships align with established interpretations of P-wave velocity behavior in karstified terrains and provide a reliable basis for identifying the waste–bedrock interface and assessing subsurface heterogeneity.

Although the general velocity patterns are comparable, the depth to bedrock and the geometry of the underlying surface differ noticeably between the two sites. At Sodol, the seismic profile exhibits pronounced vertical variability, with the bedrock encountered at depths ranging from only about 1.5 m near the unloading ramp to more than 25 m in deeper depressions farther along the profile. This highly irregular bedrock surface, characterized by sharp transitions between shallow and deep zones, suggests a strongly developed karst system with solution pockets, widened joints, and localized dissolution features. The repeated deepening and shallowing of the velocity interface indicates that the waste–bedrock boundary at Sodol is highly variable both laterally and vertically. These variations also reflect differences in bedrock quality: lower velocities in deeper sections are likely associated with more intensely weathered or fractured carbonate units, whereas the higher velocities observed near the shallower bedrock highs represent more competent and intact bedrock. In contrast, the seismic profile at Sorinj reveals a markedly different subsurface structure. Although the waste and leachate zone is still clearly distinguished from the underlying rock by a substantial increase in P-wave velocity, the transition to the carbonate substrate occurs far more uniformly with depth than at Sodol. The boundary between waste and bedrock is smoother, lacking the abrupt depressions and pinnacled highs observed at Sodol. However, unlike at Sodol, where the weathered interval is relatively thin and spatially variable, Sorinj displays a considerably thicker and more laterally continuous zone of weathered and fractured carbonate rock. Velocities greater than 1000 m/s correspond to this extensive upper weathering zone, composed of scree, broken carbonate fragments, and highly fractured material. Only where velocities exceed approximately 2000 m/s does the subsurface transition into less fractured and more competent carbonate bedrock.

Overall, the geophysical comparison of the Sodol and Sorinj landfills reveals that, although both sites share characteristic features of waste accumulation over karstified carbonate substrates, their subsurface structures differ in several ways. In both landfills, ERT and SRT consistently identify conductive waste and leachate-rich zones, thicker accumulations of material where waste was more extensively deposited, and a transition to fractured and competent carbonate bedrock marked by increases in resistivity and P-wave velocity. These shared patterns reflect typical geoelectrical and seismic signatures of karst environments, where heterogeneity in moisture content, weathering, and fracture density governs both electrical and elastic properties. However, the contrasts between the sites are equally important. Sodol exhibits a markedly irregular waste–bedrock interface, strong lateral changes in waste thickness, and a highly variable bedrock surface characterized by pinnacled highs, deep pockets, and pronounced velocity contrasts-features that point to a more rugged, mature, and spatially heterogeneous karst system. Sorinj, in contrast, is defined by a substantially thicker waste body, the presence of deeper low-resistivity anomalies that may indicate enhanced leachate penetration or structural depressions, and a smoother, more uniformly deep bedrock surface. The weathered carbonate zone at Sorinj is also significantly thicker and more laterally continuous than at Sodol, implying a different style or degree of karstification. These distinctions underline the need for site-specific interpretation even within similar geological settings and demonstrate how the combined ERT–SRT approach is capable of resolving both the common behaviors of landfills in carbonate terrains and the local variations that control leachate migration pathways and environmental risk.

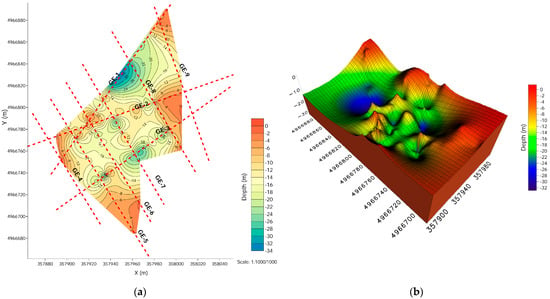

To provide a clearer visualization of the interpreted depth to the rock mass from the previously described geophysical investigations, presented as 2D interpreted depth profiles, a plan-view 2D representation and a 3D model are created. The 2D map for Sorinj landfill (Figure 10a) illustrates the spatial distribution of the depth to the rock mass, referenced to geodetic survey data, and integrates the positions of all completed ERT and SRT profiles. This spatial arrangement also illustrates where the density of geophysical data is highest and where the interpreted surface relies more on interpolation, highlighting the strengths and limitations of the subsurface model. This view enables direct comparison of depth variations between profiles and reveals lateral changes in the subsurface that cannot be fully appreciated from individual 2D sections alone.

Figure 10.

(a) 2D and (b) 3D representation of the depth to the bedrock beneath the Sorinj landfill.

In the 3D visualization for Sorinj landfill (Figure 10b), the highly irregular geometry of the rock mass surface becomes much more apparent, revealing a series of depressions and closed basins that correspond to karst sinkholes and cavities. These features manifest as localized zones of greater depth (blue–green colors), forming steep-sided depressions that are not easily interpretable from 2D profiles alone. The elevated areas (yellow–red colors) represent shallower bedrock surfaces where the carbonate rock rises closer to the landfill base, indicating zones of reduced waste thickness. The 3D surface also highlights the strong spatial variability in bedrock depth across short distances, which is a typical characteristic of karst environments. This variability is essential for understanding how leachate may preferentially migrate: deeper depressions may act as accumulation zones or vertical infiltration pathways, while elevated ridges can redirect subsurface flow laterally. The model therefore provides a spatially coherent visualization that links geophysical interpretation with geomorphological processes of karstification.

Overall, the integrated 2D and 3D representations provide a comprehensive spatial framework that supports more accurate environmental risk assessment and more informed decision-making for landfill remediation planning.

6. Conclusions

In planning landfill remediation projects, it is crucial to determine both the volume of deposited waste and the characteristics of the bedrock beneath the site. Geophysical methods are particularly valuable in this context due to their ability to provide extensive spatial coverage and their practical applicability in the field. However, landfills situated on karstic terrain present unique challenges. The heterogeneous and anisotropic nature of karst environments can lead to ambiguous or misleading geophysical signals, requiring cautious interpretation and cross-validation with other data sources. As demonstrated in this study, electrical resistivity tomography (ERT) and seismic refraction tomography (SRT) have proven especially suitable for such investigations. Their non-invasive nature and adaptability for deployment directly on landfill surfaces make them ideal for assessing subsurface conditions.

Using two case studies from Croatia, the Sodol and Sorinj landfills, this research highlights the effectiveness of these methods in estimating waste volume, identifying the depth to bedrock, and evaluating bedrock condition. At both locations, resistivity values up to 120 Ω·m were found to correspond to waste material, while higher values reflected variations in the underlying rock. Fractured zones were typically associated with lower resistivity values. Similarly, P-wave velocity data allowed for a clear distinction between waste and competent bedrock: compact bedrock was identified by velocities of approximately 3000 m/s at Sodol and 2000 m/s at Sorinj. At Sodol landfill, based on conducted survey, waste volume was estimated at 93,000 m3, which is significantly larger than previously estimated at 77,000 m3 (based on pre-disposal terrain topography models). Such data is vital for landfill rehabilitation planning. At Sorinj landfill, 2D and 3D representations of terrain configuration below waste material offers significant insight into karst features like sinkholes. Knowing the amount and spread of such karst features is vital for better assessment of waste material volume and possible pollution paths.

Overall, the results from both landfills demonstrate that the combined use of ERT and SRT is essential for obtaining a reliable and comprehensive characterization of waste deposits in karstified carbonate terrains. Each method compensates for the limitations of the other: SRT is highly effective in distinguishing competent bedrock from overlying waste materials, yet seismic signal attenuation within the heterogeneous waste layer often reduces data quality, leading to poorly defined first arrivals and requiring multistacking to achieve interpretable records. Conversely, while ERT provides detailed imaging of internal heterogeneity within the waste body, its performance is strongly dependent on proper electrode contact, which can be difficult to achieve in loose or highly resistive surface conditions. Additional uncertainty arises from the influence of leachate infiltration into fractures, which creates saturated, conductive zones that may extend into the bedrock and complicate the interpretation of both methods. Despite these limitations, the integration of SRT and ERT significantly improves the reliability of subsurface interpretation, enabling clearer delineation of the waste–bedrock interface, better identification of structurally weakened or leachate-rich zones, and a more robust understanding of the geological controls on landfill behavior. The integration of geophysical results with borehole data further improved the accuracy and reliability of the subsurface models, supporting the development of detailed 2D and 3D representations of the depth to the rock mass surface. These models are essential for informed planning and risk assessment in landfill remediation, particularly in sensitive karst environments.

Looking ahead, future work should prioritize integrating geophysical monitoring with long-term hydrogeological observations to better understand how waste degradation and leachate migration evolve over time. For engineering practice, we recommend the routine use of combined ERT–SRT surveys during landfill remediation planning, particularly in karst settings where subsurface complexity demands multi-method validation to ensure safe, cost-effective, and environmentally sound rehabilitation strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.P. and M.B.; methodology, B.P., M.B. and M.S.K.; software, B.P. and V.M.; validation, L.L. and M.S.K.; formal analysis, B.P., V.M. and M.B.; investigation, B.P. and V.M.; resources, B.P. and M.S.K.; writing—original draft preparation, B.P. and M.B.; writing—review and editing, V.M., L.L. and M.S.K.; visualization, B.P., V.M., M.B. and L.L.; supervision, M.S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to restrictions related to the commissioning party. The data were obtained as part of activities conducted for the commissioning entity and cannot be shared without their prior approval.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Božo Padovan and author Valentino Mejrušić are employed by Terra Compacta Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ERT | Electrical Resistivity Tomography |

| GPR | Ground Penetrating Radar |

| MASW | Multi-channel Analysis of Surface Waves |

| MSW | Municipal Solid Waste |

| SRT | Seismic Refraction Tomography |

References

- Hughes, T.H.; Memon, B.A.; Lamoreaux, P.E. Landfills in karst terrains. Environ. Eng. Geosci. 1994, 31, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.Z.; Drumm, E.C. Stability evaluation for the siting of municipal landfills in karst. Eng. Geol. 2002, 65, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalikakis, K.; Plagnes, V.; Guerin, V.; Valois, R.; Bosch, F.P. Contribution of geophysical methods to karst-system exploration: An overview. Hydrogeol. J. 2011, 19, 1169–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bačić, M.; Librić, L.; Kaćunić, D.J.; Kovačević, M.S. The usefulness of seismic surveys for geotechnical engineering in karst: Some practical examples. Geosciences 2020, 10, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, A.K.M.; Ibelli-Bianco, C.; Anache, J.A.A.; Coutinho, J.V.; Pelinson, N.S.; Nobrega, J.; Rosalem, L.M.P.; Leite, C.M.C.; Niviadonski, L.M.; Manastella, C.; et al. Pollution threat to water and soil quality by dumpsites and non-sanitary landfills in Brazil: A review. Waste Manag. 2021, 131, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinea, A.; Bicknell, J.; Cox, N.; Swan, H.; Simmons, N. Characterization of legacy landfills with electrical resistivity tomography: A comparative study. J. Appl. Geophys. 2022, 203, 104716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Iaco, R.; Green, A.; Maurer, H.-R.; Horstmeyer, H. A combined seismic reflection and refraction study of a landfill and its host sediments. J. Appl. Geophys. 2003, 52, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, P.J.; Toland, M.L.; Floyd, J.D. Forensic analysis of landfills using EM methods. In Proceedings of the Symposium on the Application of Geophysics to Engineering and Environmental Problems (SAGEEP), Denver, CO, USA, 20–24 March 2016; pp. 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RAWFILL. SWOT Analysis of LF Characterisation Methods. T1.3 Deliverable. RAWFILL Project (Supporting a New Circular Economy for Raw Materials Recovered from Landfills), Interreg NW Europe, 2019. Available online: https://vb.nweurope.eu/media/10040/swot_analysis_geophysics.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Mary, B.; Sottani, A.; Boaga, J.; Camerin, I.; Deiana, R.; Cassiani, G. Non-invasive investigations of closed landfills: An example in a karstic area. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 905, 167083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martí, A.; Queralt, P.; Marcuello, A.; Ledo, J.; Mitjanas, G.; Piña-Varas, P.; Freixes, A.; Solà, J.; Pons, P.; López, J. Imaging leachate runoff from a landfill using magnetotellurics: The Garraf karst case. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 920, 170827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, M.T.; Brackman, T.B.; May, E.C.; Edwards, T.W. Use of electrical resistivity tomography to reduce landfill siting risks in the south-central Kentucky karst. Environ. Earth Sci. 2024, 83, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R. Delineation of a Coal Combustion Residue Landfill and Underlying Karst Subsurface in Southwest Missouri Using ERT and MASW Surveys. Ph.D. Thesis, Missouri University of Science and Technology, Rolla, MO, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Varnavina, A.V.; Khamzin, A.K.; Kidanu, S.T.; Anderson, N.L. Geophysical site assessment in karst terrain: A case study from southwestern Missouri. J. Appl. Geophys. 2019, 170, 103838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strelec, S.; Grabar, K.; Gazdek, M.; Špiranec, M.; Stanko, D.; Jug, J. Geophysical–geotechnical landfill site investigation. Environ. Eng. 2014, 1, 103–112. [Google Scholar]

- Soupios, P.; Papadopoulos, N.; Papadopoulos, I.; Kouli, M.; Vallianatos, F.; Sarris, A.; Manios, T. Application of integrated methods in mapping waste disposal areas. Environ. Geol. 2007, 53, 661–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebrande, H.; Miller, H. Refraktionsseismik. In Angewandte Geowissenschaften II; Bender, F., Ed.; Ferdinand Enke: Stuttgart, Germany, 1985; pp. 226–260. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, B.S.; Odegard, M.E.; Sutton, G.H. Nonlinear least-squares inversion of traveltime data for a linear velocity-depth relationship. Geophysics 1979, 44, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanz, E.; Maurer, H.; Green, A.G. Refraction tomography over a buried waste disposal site. Geophysics 1998, 63, 1414–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loke, M.H.; Barker, R.D. Rapid least-squares inversion of apparent resistivity pseudosections by a quasi-Newton method. Geophys. Prospect. 1996, 44, 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loke, M.H.; Dahlin, T. A comparison of the Gauss–Newton and quasi-Newton methods in resistivity imaging inversion. J. Appl. Geophys. 2002, 49, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstone, C.; Dahlin, T.; Ohlsson, T.; Hogland, H. DC-resistivity mapping of internal landfill structures: Two pre-excavation surveys. Environ. Geol. 2000, 39, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intelligent Resources Inc. Rayfract Seismic Refraction and Tomography Software. Available online: https://rayfract.com/pub/prospect.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Loke, M. Rapid 2-D Resistivity and IP Inversion Using the Least-Squares Method; Instruction Manual for RES2DINVx64 Version 4.07; Geotomosoft Solutions: Gelugor, Malaysia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- City of Rab. Remediation and Closure of the Sorinj Waste Disposal Site. Available online: https://www.rab.hr/sanacija-i-zatvaranje-odlagalista-otpada-sorinj/ (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Garasic, M.; Kovacevic, M.S.; Juric-Kacunic, D. Investigation and remediation of the cavern in the Vrata Tunnel on the Zagreb–Rijeka highway (Croatia). Acta Carsol. 2010, 39, 61–77. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. Waste Generation, Excluding Major Mineral Waste. 2022. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Waste_statistics (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Swami, S.; Suthar, S.; Singh, R.; Singh, P.; Tyagi, V.K.; Yoshihito, S.; Wong, J.W.C. Integration of anaerobic digestion with artificial intelligence to optimise biogas plant operation. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 27, 9773–9803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, F.; Wen, Z.; Huang, S.; De Clercq, D. Mechanical biological treatment of municipal solid waste: Energy efficiency, environmental impact and economic feasibility analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 178, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahnazari, A.; Rafiee, M.; Rohani, A.; Nagar, B.B.; Ebrahiminik, M.A.; Aghkhani, M.H. Identification of effective factors to select energy recovery technologies from municipal solid waste using multi-criteria decision making (MCDM): A review of thermochemical technologies. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2020, 40, 100737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Environmental Protection and Green Transition, Republic of Croatia. Available online: https://envi.azo.hr/ (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Zhan, L.T.; Xu, H.; Jiang, X.M.; Lan, J.W.; Chen, Y.M.; Zhang, Z.Y. Use of electrical resistivity tomography for detecting the distribution of leachate and gas in a large-scale MSW landfill cell. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 20325–20343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koda, E.; Tkaczyk, A.; Lech, M.; Osiński, P. Application of electrical resistivity data sets for the evaluation of the pollution concentration level within landfill subsoil. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itota, G.O.; Balogun, A.O. The impact of a municipal solid waste dumpsite on soil and groundwater using 2-D resistivity imaging technique. Phys. Sci. Int. J. 2016, 11, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, N.; Prado, R.L.; Elis, V.R.; Miguel, M.G.; Gandolfo, O.C.B.; Conicelli, B. Evaluating elastic wave velocities in Brazilian municipal solid waste. Environ. Earth Sci. 2019, 78, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, V.; Guedes, V.; Borges, W.; Rocha, M.; Cunha, L. Analysis of seismic refraction and surface wave data for the evaluation of layers and saturation of solid waste from a landfill in Brasília, Brazil. Braz. J. Geophys. 2022, 40, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).