1. Introduction

Due to the limitations in the development of autonomous driving technology, the traffic system is expected to remain in a long-term mixed state of human driving and autonomous driving. Since human driving exhibits heterogeneity in driving behavior, in response to complex traffic scenarios, drivers of varying driving styles are likely to exhibit divergent behavioral patterns. This discrepancy poses a significant challenge for autonomous driving systems. Autonomous vehicles are typically trained on standardized datasets, whereas the behavior of human drivers in real-world conditions is inherently uncertain and stochastic. Consequently, their actions often exhibit significant deviations from the normative patterns encapsulated in the training data. In mixed-traffic environments, this gap can impair an autonomous vehicle’s ability to timely recognize a human driver’s style and anticipate their maneuvers. Such a failure in anticipation may lead to traffic accidents or force the autonomous vehicle into making sudden evasive maneuvers, which in turn compromises its safety, degrades overall traffic efficiency, and increases energy consumption.

Human drivers do not merely react passively to their environment; they proactively manage uncertainty. For instance, when their line of sight is obstructed, a driver’s decision to decelerate is not solely to avoid a known obstacle but is, more fundamentally, an act of information seeking to rule out latent, unobserved risks [

1]. This behavior exemplifies a proactive strategy for uncertainty resolution that necessitates precise modeling. This trend signifies a paradigm shift within the field: from modeling mere behavioral kinematics to modeling the cognitive agent—the driver. Researchers have begun to classify driver behaviors into distinct styles (e.g., “aggressive”, “cautious” or “eco-friendly”) [

2], with the goal of predicting a vehicle’s next action based on the driver’s intrinsic profile [

3]. For an autonomous vehicle, this approach is critical for generating robust predictions in novel or unseen scenarios, as a driver’s inherent disposition is often a reliable predictor of their future reactions [

4].

Driving style heterogeneity not only influences safety and traffic efficiency but also exerts a measurable impact on fuel consumption and CO

2 emissions [

5]. Aggressive drivers, who frequently accelerate and brake, create sharp fluctuations in power demand, thereby increasing instantaneous fuel consumption and emission rates. In contrast, smoother and more anticipatory driving behaviors contribute to energy savings and emission reduction [

6]. Consequently, enabling autonomous vehicles to recognize and classify human driving styles allows decision-making systems to jointly optimize safety, efficiency, and environmental sustainability through carbon-emission-aware behavioral control [

7].

In mixed-traffic environments, a fundamental challenge lies in interpreting and adapting to diverse human driving styles that embody different risk preferences, cognitive traits, and interaction patterns. Existing research on autonomous driving and driver behavior modelling has made significant advances, but several critical gaps remain. Behavioural representation remains constrained: most methods rely heavily on low-dimensional kinematic features and neglect richer attributes such as perception, intention changes, and driver risk-preference. For example, Fang et al. [

8] note that current behavioural-intention prediction datasets are still limited to simple labels and fail to capture latent cognitive and risk dimensions.

The central challenge is achieving a dynamic balance between fuel economy and emission constraints while maintaining safe and efficient traffic flow. Prior efforts, such as the Dynamic Programming (DP)–based fuel-optimal trajectory planning of Wang et al. [

9], and the emission-aware Model Predictive Control (MPC) strategy developed by Bakibillah A. S. M. et al. [

10], demonstrate the feasibility of jointly optimizing fuel consumption and emission outcomes. While MPC offers strong physical priors and safety guarantees, deep learning models often operate independently, leading to state representations that omit physical constraints. Norouzi et al. [

11] review ML-MPC integration in automotive systems and highlight that embedding MPC within neural training remains underexplored. Similarly, Mensing F. et al. [

12] and Deng J. et al. [

13] formulated eco-driving control strategies that incorporate emission penalties or multi-objective constraints to enhance energy efficiency. These studies suggest a clear trend: autonomous driving systems evolve toward unified optimization frameworks capable of harmonizing safety, efficiency, and environmental sustainability in complex human–machine traffic ecosystems.

At the decision-optimization level, recent studies attempt to extract the underlying behavior-generation mechanisms directly from human driving data and transfer them into autonomous driving frameworks, primarily through inverse reinforcement learning (IRL). For instance, Qiu et al. [

14] utilized maximum-entropy IRL to analyze car-following behaviors in the NGSIM dataset, successfully capturing cut-in tendencies while balancing multiple driving objectives. in dynamic and safety-critical driving scenarios, decision-making frameworks often face an imbalanced multi-objective optimisation problem: safety and efficiency objectives tend to be treated in isolation rather than coordinated within a unified structure. Finally, although driver behaviour strongly influences fuel consumption and CO

2 emissions, many current models overlook the behaviour–emission coupling, undermining the sustainability of learned driving strategies. Xing et al. [

15] demonstrate an initial attempt at “energy-aware deep learning for driving behaviour” but highlight that most behaviour models still neglect emission outcomes.

Despite notable progress in driving-style modeling and interactive decision-making, several key limitations persist:

Limited behavioral representation: Existing models rely mainly on low-dimensional kinematic features and fail to capture richer behavioral attributes such as perception, intention, and risk preference.

Insufficient integration of MPC and learning-based methods: Model Predictive Control (MPC) and data-driven approaches are often treated separately. The lack of MPC embedding within neural training leads to state representations that omit physical priors, thereby reducing prediction accuracy and decision reliability.

Imbalanced multi-objective optimization: In dynamic and safety-critical scenarios, decision-making frameworks struggle to balance safety and efficiency, often optimizing one objective at the expense of the other due to the absence of a coherent coordination mechanism.

Neglect of environmental factors: Driving behavior strongly influences fuel consumption and CO2 emissions, yet current models rarely account for behavior–emission coupling, undermining the sustainability of learned strategies.

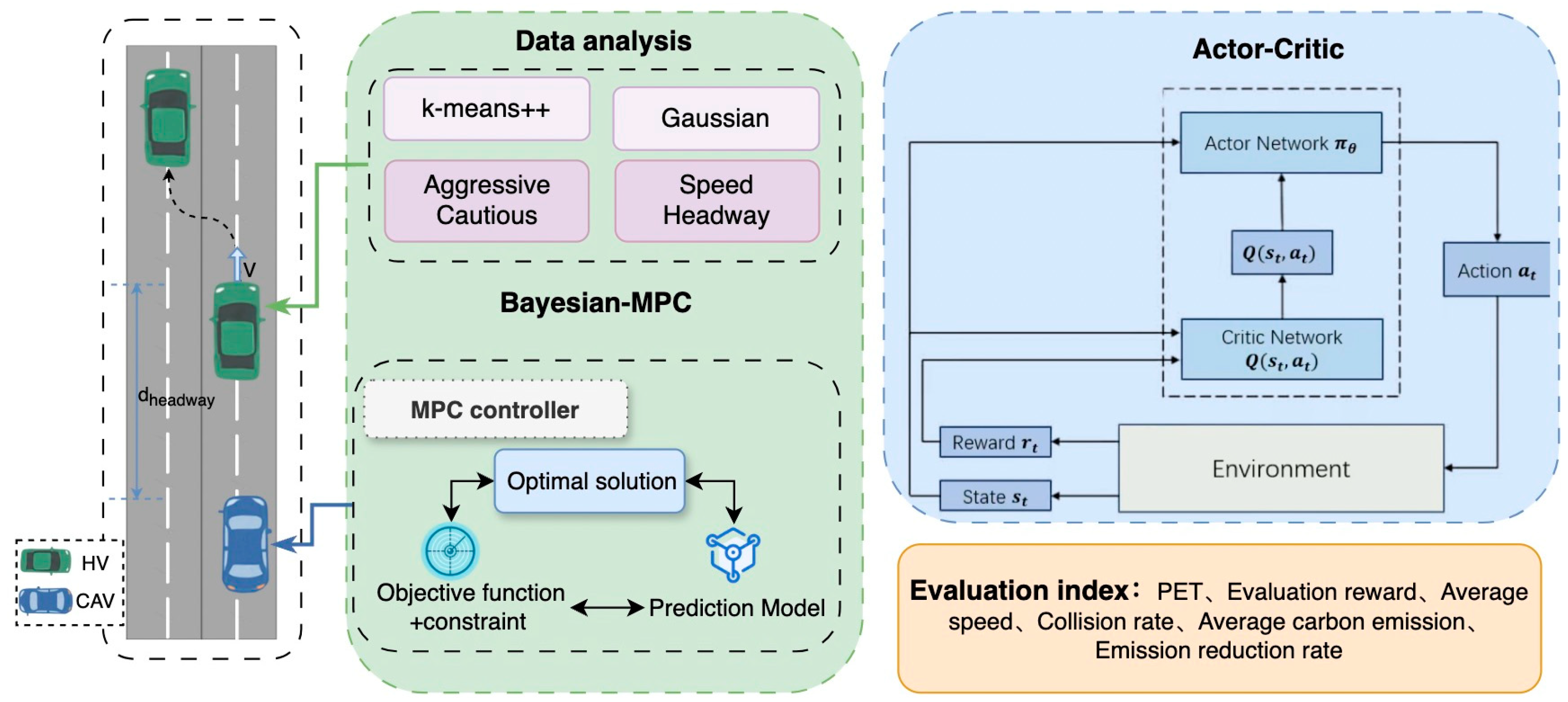

To address the above issues, this study proposes an overall framework consisting of four parts, as illustrated in

Figure 1: traffic scenario selection and data analysis, Bayesian–MPC predictive control, Actor–Critic reinforcement learning decision-making and comprehensive evaluation. The details are as follows:

Data-driven driving style analysis: In the offline phase, K-means++ clustering is applied to naturalistic driving datasets to extract representative behavioral patterns. Two typical driving styles—aggressive and cautious—are identified based on key motion and interaction features. These clusters serve as interpretable prior distributions for subsequent Bayesian reasoning, providing a structured behavioral foundation that captures inter-driver diversity and supports knowledge transfer to the online learning stage.

Bayesian–MPC prediction and control: During online interaction, the Bayesian inference module dynamically updates the posterior probabilities of each driving style using real-time indicators such as speed, acceleration, and headway distance. This probabilistic reasoning quantifies the behavioral uncertainty of surrounding vehicles. The posterior probabilities are then integrated into a Model Predictive Control (MPC) framework that combines behavioral uncertainty with physical vehicle dynamics, enabling foresighted trajectory prediction and robust control adjustments under varying traffic conditions.

Actor–Critic decision-making: The Actor–Critic reinforcement learning module takes the Bayesian–MPC outputs as adaptive inputs or weighting factors, guiding the decision process under uncertain multi-agent interactions. The actor network generates behavior-aware control actions, while the critic evaluates their long-term values by balancing safety, comfort, and efficiency. This probabilistic conditioning allows the policy to dynamically adapt to the most probable driver style, ensuring global optimality, robustness, and interpretability of decision-making.

Evaluation and validation: The effectiveness of the proposed framework is verified using Post-Encroachment Time (PET), average speed, reward, and collision rate.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 focuses on the methods and fundamental concepts of driving style recognition and trajectory prediction.

Section 3 provides a detailed description of the multi-agent reinforcement learning model constructed in this study.

Section 4 presents the experiments, results, and analysis. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Basic Methods

To capture these latent behavioral categories, this paper adopts the K-means++ clustering algorithm to extract representative driving patterns from the NGSIM US-101 trajectory dataset. As an unsupervised learning method, K-means++ offers two advantages that align with the target of driving-style abstraction. It avoids subjective labeling bias by allowing natural grouping of driving behaviors based on intrinsic feature similarity. Its optimized initialization enhances cluster robustness, improving convergence stability in large-scale trajectory data.

2.1. Driving Style Extraction Based on the K-Means ++ Algorithm

This study utilizes the publicly available NGSIM US-101 dataset, which provides continuous vehicle trajectory data—including position, velocity, acceleration, and headway—for driving behavior analysis, as shown in

Table 1.

Wu et al. [

16] combined K-means and D-S evidence theory decision methods to perform driving-style cluster analysis. Dörr [

17] and Aljaafreh et al. [

18] used fuzzy logic to design a driving style recognition system and realized online recognition of driving styles. Although K-means clustering has been widely used for driving style analysis, its performance remains sensitive to the initialization of cluster centers, leading to unstable and sometimes suboptimal clustering results [

19]. To improve clustering robustness, this study adopts the K-means++ algorithm, which optimizes centroid initialization by selecting the first centroid

randomly and choosing subsequent centroids based on a distance-weighted probability distribution. The specific parameters and their descriptions are presented in

Table 2.

After initialization, each sample is assigned to the nearest centroid

according to the minimum Euclidean distance criterion, expressed as:

where

denotes the Euclidean distance between sample

and cluster

.

Calculate the quality center of each cluster as the new cluster center. This process is repeated iteratively until centroids no longer change or the maximum number of iterations is reached, at which point the algorithm converges.

The Davies–Bouldin Index (DBI) was employed to evaluate the average similarity among clusters. A smaller DBI indicates stronger separability among clusters and improved clustering performance. When DBI approaches zero, overlap between clusters is minimized and boundaries are more distinct, indicating an ideal cluster structure.

where

represents the average intra-cluster dispersion of cluster

, and

represents the distance between the centroids of clusters

and

.

Additionally, the Calinski–Harabasz (CH) index was used to assess clustering quality. Its principle is based on the ratio between inter-cluster dispersion and intra-cluster compactness. A higher CH index implies greater separation between clusters and stronger cohesion within clusters, reflecting superior clustering performance. The calculation is given by:

where

is the trace of the between-cluster covariance matrix,

is the trace of the within-cluster covariance matrix,

is the number of clusters, and

is the total number of samples. The covariance matrices are computed as:

where

is the number of samples in cluster

,

is the centroid of cluster

, and

is the global centroid of all samples.

2.2. Behavior Prediction Based on Bayesian Model

Traditional MPC-based methods have been extended to adaptively tune their weight matrices under changing driving conditions. For instance, Chang et al. [

20] introduced a fuzzy rule-based mechanism for real-time MPC weight optimization, improving both tracking accuracy and ride comfort. Similarly, Pang et al. [

21] employed a fuzzy inference system to adapt MPC parameters to dynamic environments, while Tian et al. [

22] demonstrated that curvature-aware weight adjustment enhanced stability in high-speed scenarios. Building on these, Liu et al. [

23] integrated risk assessment into MPC to achieve adaptive shared control, and Liang et al. [

24] proposed a multi-MPC coordination strategy for extreme situations. These methods remain primarily rule-driven, relying on handcrafted adaptation mechanisms that limit their scalability and generalization.

To better address uncertainty in surrounding vehicle behaviors, this study employs a Bayesian inference framework to provide probabilistic state predictions for the MPC module [

25]. Velocity and time headway are selected as key behavioral features, and the posterior distribution

is computed using Bayes’ theorem based on historical observations, enabling short-term prediction of driving tendencies. These probabilistic predictions are then incorporated into MPC, which leverages its ability to handle dynamic constraints and optimize future trajectories, thereby achieving more anticipatory and stable motion planning [

26].

where

and

denote the mean and variance of key behavioral variables corresponding to style.

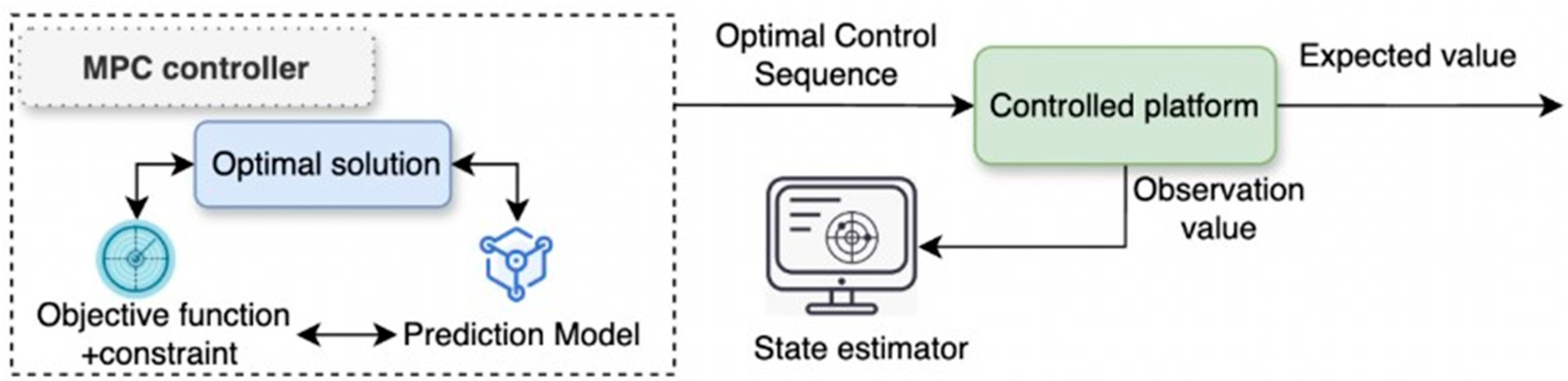

Building on the posterior distribution of driving styles, MPC was further incorporated. By leveraging Bayesian inference to predict the future trajectories of all vehicles within the observation range, the ego vehicle can make proactive decisions and perform path planning in advance, thereby avoiding emergency braking or sudden lane changes and ensuring driving safety. As shown in

Figure 2 the specific process is described as follows:

The MPC fuses sensor observation data and applies filtering to obtain the current state estimation of the ego vehicle and its surrounding vehicles.

The current state is then fed into the MPC prediction model, which performs receding-horizon simulation over a finite horizon

, generating candidate control sequences. These sequences include multiple potential trajectories of the ego vehicle as well as probabilistic motion distributions of surrounding vehicles [

27].

Candidate sequences that would lead to collisions or violate dynamic constraints are eliminated. The remaining safe sequences are evaluated through an objective function.

The optimal control sequence that minimizes the cost function is solved and transmitted as control commands to the vehicle for execution. This iterative process is repeated in real time, thereby achieving dynamic optimization.

2.3. Driving Style-Aware Trajectory Prediction and MPC Optimization

The decision planning of autonomous vehicles relies on accurate prediction of the future behaviors of surrounding vehicles. Since the primary influencing factor of vehicle behavior is the current kinematic state rather than complex long-term driver intentions, an efficient prediction can be achieved using a simplified kinematic model. Let the ego vehicle’s state at time

be

, where

denote position,

velocity, and

the heading angle [

28]. The optimal control sequence over a horizon

is denoted by:

where MPC optimization generates the optimal trajectory

.The specific values and definitions of the variables are shown in

Table 3:

Based on a simplified constant yaw rate and constant acceleration model, the kinematic state evolves as:

For ,where is the currently observed yaw rate and is the acceleration input. The trajectory point sequence is .

However, driving style significantly affects the distribution of acceleration. Drivers with different styles select distinct values for mean acceleration, headway, and lane-changing frequency, which in turn influence trajectory prediction [

29]. To address this, a Bayesian network is employed to identify the driving styles of vehicles within the observation

range in real time. By utilizing a set of short-term behavioral features as observational evidence and combining them with the posterior probability distribution

of the background vehicle’s driving style, each driving style corresponds to a specific acceleration adjustment strategy and a parameterized driver model with its parameter set

, thereby generating a style-specific acceleration

. For each driving-style cluster we estimate a style-specific parameter set

by fitting a linearized car-following function

where

is the parameter set characterizing driving style j. Consequently, the future acceleration of a vehicle is no longer constant but rather an expected acceleration

based on driving style probability:

The expected acceleration is introduced into the kinematic model to obtain probability-aware trajectory prediction:

The trajectory point sequence has been updated to , which means that the MPC now sees the most likely predicted trajectory that integrates the uncertainty of the opponent’s driving style.

Ultimately, the optimization objective function of MPC will be calculated based on this more accurate predicted trajectory:

Among them, the collision cost depends on the probability-aware predicted trajectory , thereby more accurately assessing future collision risks.

2.4. Carbon Emission Modeling

Building upon driving style recognition and trajectory prediction, the dynamic behavioral characteristics of a vehicle—particularly its speed and acceleration—have a direct impact on both energy consumption and carbon emissions. Different driving styles can alter the patterns of speed fluctuation and acceleration distribution, thereby shifting the engine operating point and influencing the energy conversion efficiency, which ultimately leads to notable differences in emission levels [

30]. To quantitatively characterize this coupling relationship between driving behavior and emissions, it is necessary to develop a carbon emission model that reflects the dynamic features of driver behavior.

Vehicle carbon emissions are primarily influenced by operational and environmental factors, such as driving speed and travel distance. For quantitatively assess the environmental impact of autonomous driving decisions and incorporate sustainability objectives into the optimization process, this study adopts the VT-Micro Microscopic Emission Model proposed by Ahn et al. [

31] as the core computational module for energy consumption and carbon emission analysis. The VT-Micro model uses instantaneous speed and acceleration as inputs and establishes a nonlinear mapping between instantaneous fuel consumption rate and kinematic states through polynomial regression equations derived from extensive real-world vehicle experiments.

In this way, the model accurately captures the influence of driving behavior on energy use and emissions without requiring detailed engine parameters. Its functional form can be expressed as:

where

denotes the instantaneous emission rate, and

represents empirically calibrated regression coefficients. Based on the parameter ranges inferred from relevant literature [

32,

33], where

typically falls within 0.02–0.05 g/m and

within 0.005–0.03 g/m, we select

and

in accordance with our experimental environment and traffic settings. By discrete integration, the total emission over a driving cycle can be computed as:

By integrating the VT-Micro model into the decision loop, the autonomous driving system can directly link behavioral choice to its corresponding emission consequence at the microscopic level [

5]. This enables the controller to explicitly avoid high-emission maneuvers such as aggressive acceleration and oscillatory car-following, thereby achieving smoother trajectories with lower fuel consumption and CO

2 output. In this way, carbon-aware decision-making becomes an inherent outcome of the control process rather than a post-evaluation metric, providing a practical pathway for autonomous driving to enhance both safety and environmental sustainability [

34].

3. Materials and Methods

The driving scenario considered in this study is a freeway straight road, where cooperative interactions among vehicles are modeled as a Partially Observable Markov Decision Process (POMDP). In this framework, each Connected and Autonomous Vehicle (CAV) can only access local observations of the environment and makes decisions based on reinforcement learning policies. The POMDP can be represented as a tuple:

where

is the state space set, describing the global traffic environment;

is the local observation set, where each agent perceives only part of the environment.;

is the action space set, representing the set of available actions for all agents.

denotes the joint state transition probability of moving from state

to

executing action

;

is the set of reward functions, where

represents the reward by agent

receives after executing action

in the global state.

is the discount factor that weighs the importance of future rewards relative to current ones; and

is the number of autonomous vehicles. Each agent is equipped with an independent Actor network and Critic network.

3.1. State Space

The state of connected autonomous vehicle is defined as a matrix of dimensions , where is the number of vehicles within the perception range and is the number of vehicle state features. Each agent’s local state includes the following features:

: whether nearby vehicles are observed.

: Longitudinal position of surrounding vehicles relative to the ego vehicle.

: Lateral position of surrounding vehicles relative to the ego vehicle.

: Longitudinal velocity of surrounding vehicles relative to the ego vehicle.

: Lateral velocity of surrounding vehicles relative to the ego vehicle.

: Ego vehicle’s heading angle.

: The probability that the vehicle belongs to the aggressive driving style

: The probability that the vehicle belongs to the cautious driving style.

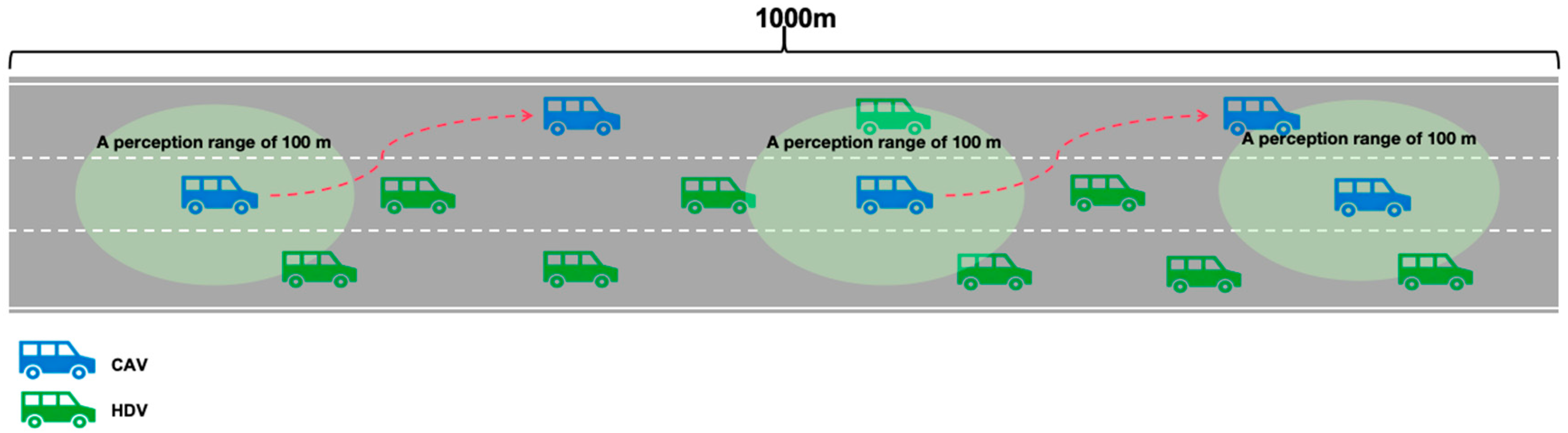

The ego vehicle’s perception range is set to [−100 m, 100 m]. Each vehicle can observe up to eight surrounding vehicles, including the leading and following vehicles in its own lane, as well as those in adjacent lanes. Therefore, the decision-making process of each autonomous vehicle is modeled as a POMDP.

3.2. Action Space

In the driving decision-making of connected autonomous vehicles, the action space

represents the set of feasible actions at each time step, including lane change (left/right), cruising, acceleration, and deceleration. The action set is defined as:

All vehicles’ actions collectively form a high-dimensional joint action space . In the decision-making process, reinforcement learning algorithms first learn high-level driving policies, while the low-level controller converts decision signals into steering and longitudinal control commands to drive the vehicle.

3.3. Reward

The reward function serves to assess an agent’s feedback when executing actions in specific states, thereby enabling each CAV to optimize its behavior for safe and efficient highway travel while proactively anticipating the driving styles of surrounding vehicles [

35]. Ultimately, the goal is to improve overall traffic flow efficiency under the constraints of safety and comfort.

Consistent with prior work, the collision penalty was assigned the highest weight to ensure that safety dominates the learning process and prevents agents from exploiting unsafe high-efficiency behaviors [

36,

37]. The speed-related weight is higher for the aggressive driving style and lower for the cautious one, reflecting established distinctions between efficiency-oriented and risk-averse behaviors [

38]. Comfort-related terms were given moderate weights, as suggested in previous studies indicating that comfort should influence decisions without overriding safety. Headway-related weights were set above comfort to maintain adequate following distance, consistent with multi-objective car-following models emphasizing Time-to-Collision (TTC) and spacing stability [

39]. A moderately weighted eco-driving term can be incorporated into the model to account for energy-related objectives without compromising safety or traffic performance [

40]. Accordingly, the reward function was formulated, and the associated weights were assigned following these principles, as presented in Equation (19) and

Table 4.

where

is the current distance to the preceding vehicle, and

is the minimum safe headway threshold,

is the instantaneous fuel consumption rate depending on vehiclevelocity

and acceleration

,

is the maximum fuel consumption rate.

Accordingly, denotes the collision penalty term, is the speed-efficiency reward, represents the comfort term, corresponds to headway maintenance, and denotes the eco-driving term based on the VT-Micro fuel consumption model.

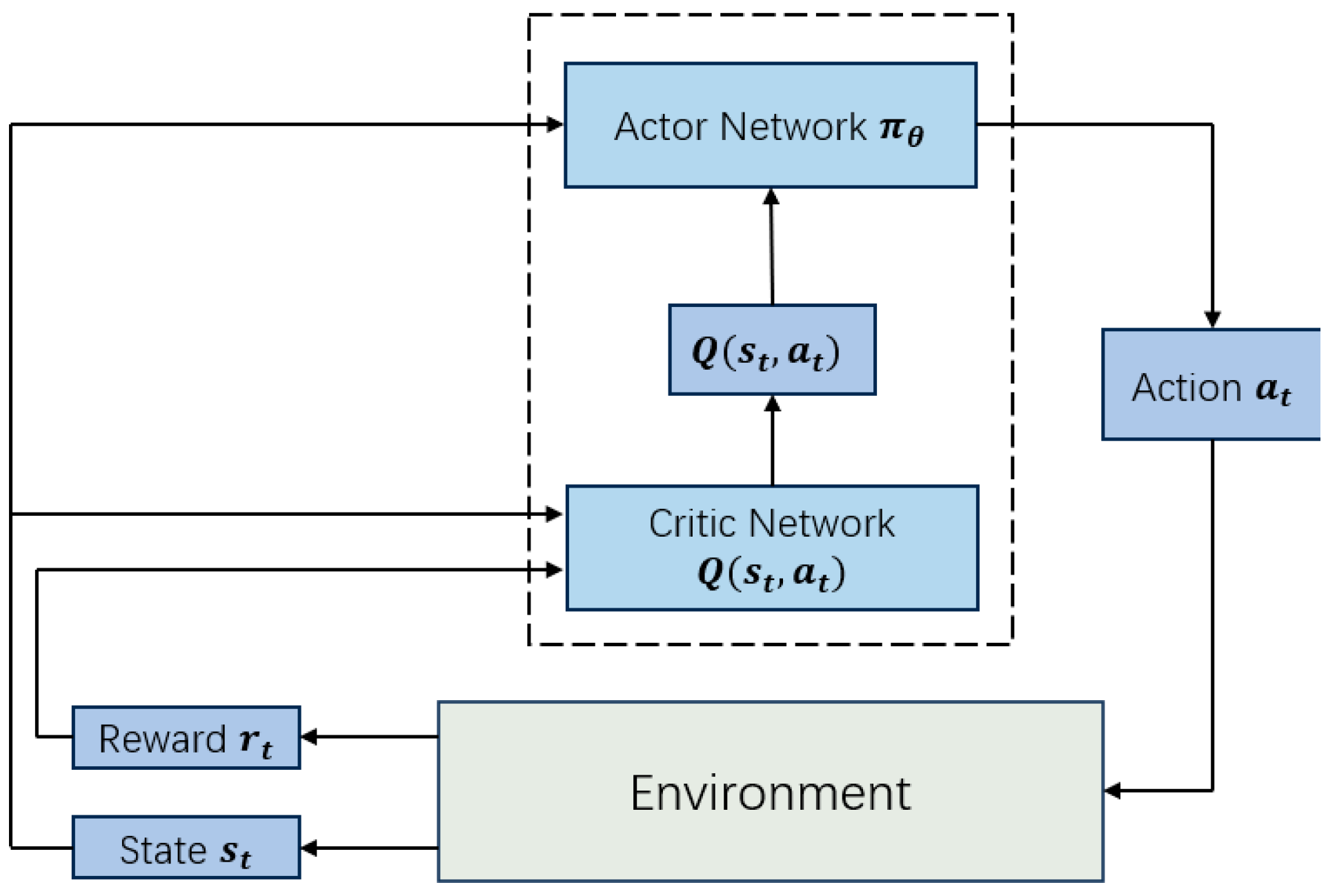

3.4. Actor–Critic Network

The Actor–Critic architecture is employed to improve learning efficiency and stability in complex continuous control tasks. In this framework, the Actor network determines the action to be executed based on the current state, while the Critic network evaluates the action-value, facilitating more effective policy optimization. The Actor learns a policy

, parameterized by

, which outputs a probability distribution over possibleactions

given the current state

, as detailed in

Figure 3.

After the Actor learns the policy

, the Critic is responsible for learning the action-value function to evaluate the long-term value

of executing a specific action in the current state. The agent selects actions according to the Actor’s policy, interacts with the environment, observes the next state, and obtains rewards. The Critic defines the action-value function

as:

The core task of the Critic is to evaluate the performance of the current policy by minimizing the estimation error of the value function. The advantage function is defined as:

Here, represents the expected cumulative discounted reward that an agent can obtain when following policy and executing all possible actions in state . The discount factor is applied to balance the importance of future rewards relative to immediate rewards. The advantage function measures the extent to which action in state outperforms or underperforms the average action under the current policy. A positive indicates superiority, while a negative value indicates inferiority. Therefore, the advantage function effectively identifies high-value actions, reduces estimation variance, and promotes efficient policy optimization.

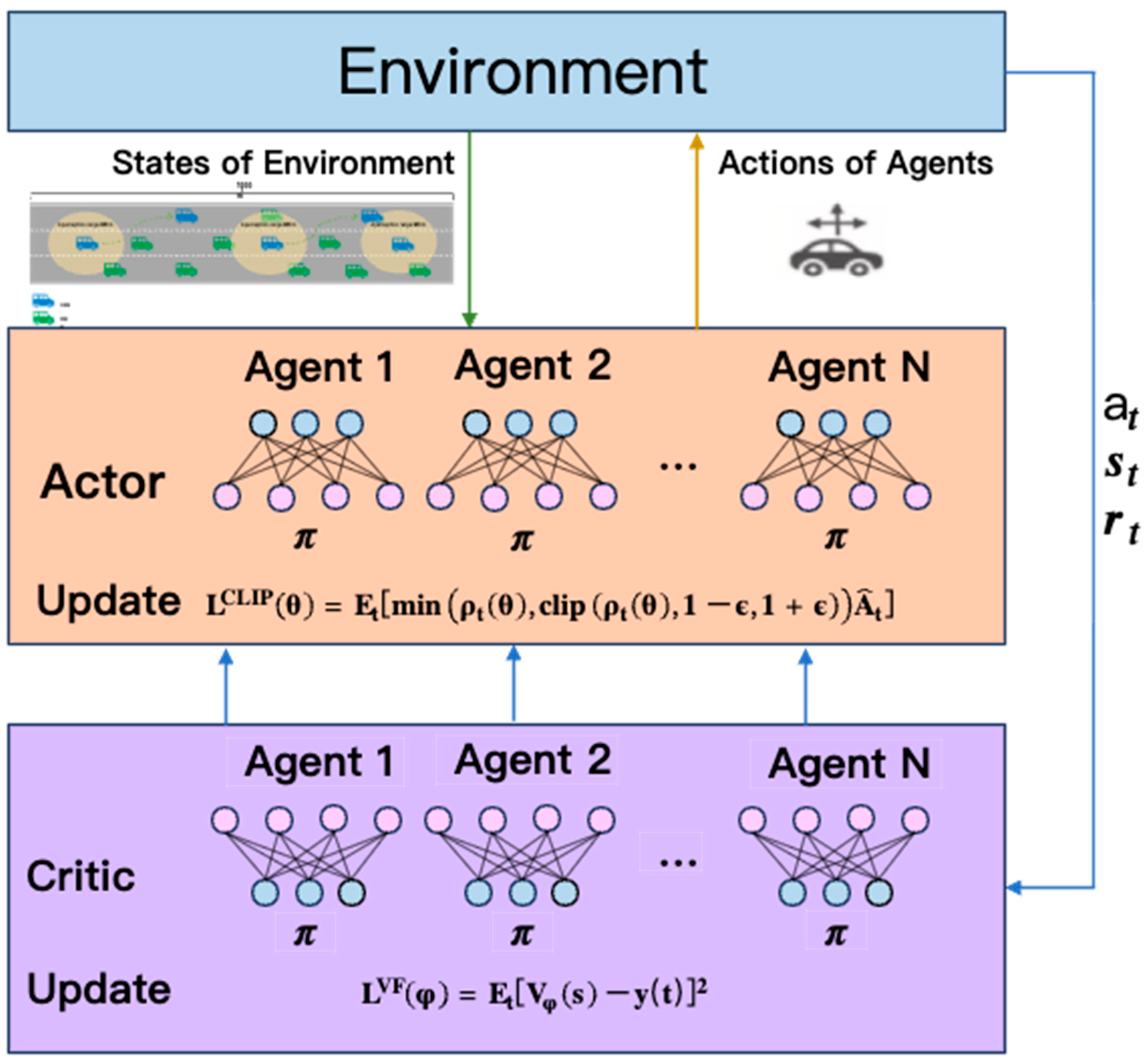

3.5. MAPPO Algorithm

The MAPPO algorithm [

41] is a policy gradient (PG)-based method that introduces a novel surrogate objective function to achieve mini-batch updates, effectively mitigating the sensitivity of traditional PG algorithms to learning rates and the difficulty of setting step sizes. The algorithm is derived from Trust Region Policy Optimization (TRPO) and incorporates a clipping mechanism to construct the surrogate objective function. We employ an Actor network

to approximate the policy function and a Critic network

to approximate the value function, where

and

are the network parameters [

42].

where

denotes the ratio between the new policy and the old policy, and clipping is applied to prevent instability caused by large policy updates.

represents the Generalized Advantage Estimator (GAE), which calculates the advantage of a specific action relative to the average policy performance. Its formula is:

The Critic network parameters

are updated by minimizing the following loss function:

where

denotes the target value. The overall structure of the MAPPO algorithm is illustrated in

Figure 4.

4. Results

4.1. Driving Style Clustering and Analysis

The CH index and DBI were used to evaluate clustering quality. Based on these metrics, driving styles were effectively divided into two categories—aggressive and cautious. As shown in

Table 5, when K = 2, CH = 234.94 and DBI = 0.48. When K = 3, CH = 214.31 and DBI = 0.87, with blurred cluster boundaries and unstable centroids, failing to improve style separability and reducing interpretability. Therefore, K = 2 was selected as it provided the clearest and most statistically distinct classification.

Figure 5 illustrates the clustering results of the driving style experiment using the K-means++ algorithm. Each point represents a sample of vehicle behavior, with colors indicating two primary driving style groups: aggressive (red) and cautious (blue). The scatter plots reveal clear separation patterns in the relationships among speed, acceleration, and time headway. The clustering centers provide quantitative insights into the driving styles:

Aggressive driving style: speed = 46.83 km/h, acceleration =0.45 m/s2, and time headway = 1.53 s.

Conservative driving style: speed = 41.80 km/h, acceleration = 0.39 m/s2, and time headway = 2.46 s.

From the clustering centers, the differences between driving styles are evident. Aggressive drivers maintain higher speeds (=46.83 km/h), slightly higher acceleration (=0.45 m/s2), and shorter time headways (=1.53 s), indicating a preference for efficiency, faster travel, and closer following. Conservative drivers travel at lower speeds (=41.80 km/h) with smoother acceleration (=0.39 m/s2) and longer headways (=2.46 s), reflecting a focus on safety, stability, and comfort.

To further characterize the behavioral differences across driving styles, this study employs Gaussian distributions to model key variables, including vehicle speed, acceleration, and headway. The probability density function is in the form of:

Gaussian distributions can capture both the central tendency and the stochastic variability of these variables. For aggressive driving behavior, vehicle speed follows a Gaussian distribution with a mean of 46.83 km/h and a variance of 5.54. Acceleration has a mean of 0.45 m/s2 and a variance of 0.38, while headway exhibits a mean of 1.53 s and a variance of 0.36. These statistics indicate that aggressive drivers generally maintain higher speeds, respond with more rapid acceleration, and keep shorter but more consistent following distances. In contrast, conservative driving behavior is characterized by a vehicle speed mean of 41.80 km/h with a variance of 6.95, an acceleration means of 0.39 m/s2 with a variance of 0.40, and a headway mean of 2.46 s with a variance of 0.73. These features suggest that conservative drivers tend to maintain lower speeds, exhibit smoother acceleration patterns, and keep longer yet more variable following distances.

Overall, the clustering centers highlight coherent behavioral patterns: aggressive drivers prioritize speed and dynamic maneuvers under acceptable risk, while conservative drivers adopt more cautious, stable driving strategies. These distinctions capture the heterogeneity of driving styles and provide a basis for assigning prior probabilities in subsequent Bayesian inference of driver behavior.

4.2. Scene Verification

4.2.1. Experimental Design

We designed a 1 km three-lane highway scenario, where the perception range of each autonomous vehicle was set to 100 m. According to different traffic densities, two groups of experimental conditions were established. The configurations of Connected and Autonomous Vehicles (CAVs) and Human-Driven Vehicles (HDVs) in each scenario were as follows. The highway traffic simulation scenario is illustrated in

Figure 6.

During training, all algorithms were trained for a total of 1 million steps. Model evaluation was performed every 200 training episodes, with ten independent evaluation runs executed at each evaluation point; the reported average reward is computed over these 200-episode intervals. In the simulation environment, initial vehicle speeds were sampled uniformly in the range 25–27 m/s, and a random perturbation in [−1.5, 1.5] m was added to initial vehicle positions to improve realism. The decision-making frequency was set to 5 Hz. Experiments were conducted on a Windows 10 workstation equipped with an NVIDIA A100 (40 GB) GPU (Nvidia, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and an Intel(R) Core (TM) Ultra 9 285K processor (Intel, Santa Clara, CA, USA); the implementation uses Python 3.8, while other network parameters are listed in

Table 6.

4.2.2. Risk Assessment

To quantify potential interaction risks, this study adopts the PET as the core metric. PET measures the time interval between two vehicles passing the same conflict point in succession, where a smaller PET indicates a higher collision likelihood [

44]. Compared with TTC, PET is more robust under trajectory uncertainty and better suited for assessing conflicts in complex multi-vehicle interactions. By integrating PET into the prediction–decision loop, autonomous vehicles can evaluate short-term collision risks in advance, enabling proactive and safer maneuver planning. When the Euclidean distance between two vehicles is less than their average vehicle length, it is determined that there is a conflict risk, and the PET calculation is triggered:

where

and

represent the positions of the two vehicles, respectively,

and

represent their lengths. Subsequently, the PET is calculated based on the time difference of the two vehicles passing through the conflict point:

where

and

respectively represent the time when vehicles

and

pass through the conflict point.

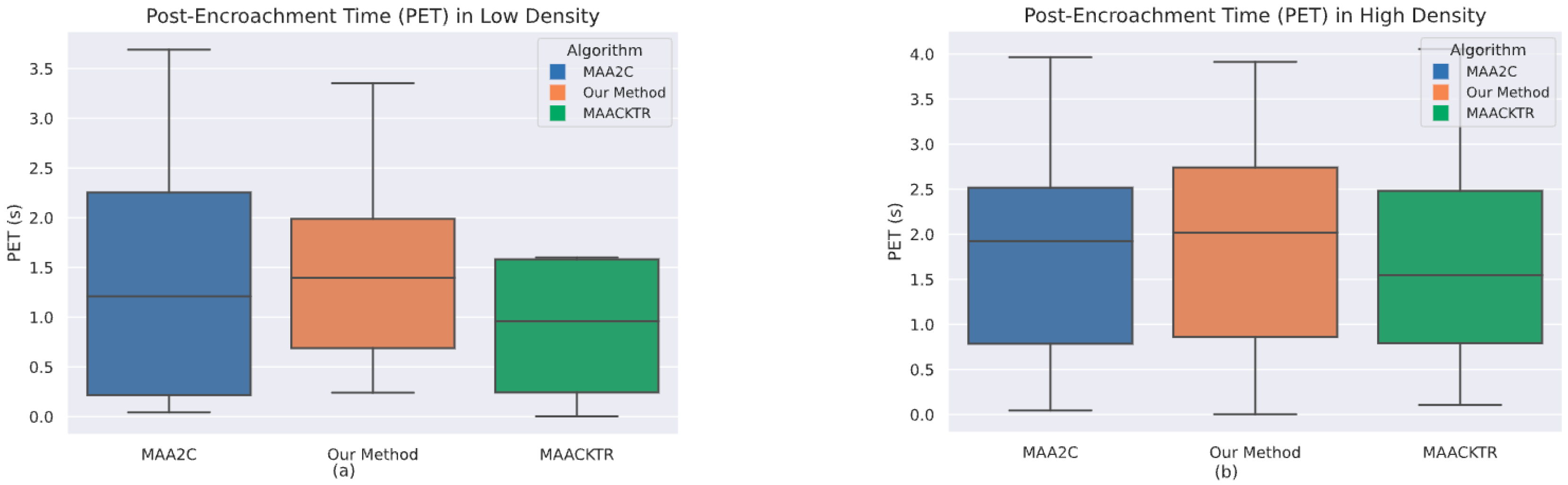

In

Figure 7a, in the low-density scenario, the proposed method achieved an average PET of 1.4 s, outperforming both Multi-Agent Advanced Actor–Critic (MAA2C, 1.2 s) and Multi-Agent Actor–Critic using Kronecker-Factored Trust Region (MAACKTR, 0.8 s). Since PET directly reflects the temporal safety margin at potential conflict points, its improvement provides quantitative evidence that our model more effectively suppresses short-term collision risk. The larger PET indicates that the ego vehicle preserves greater safety margins during interactions, highlighting the advantage of using PET as a risk-assessment metric.

By incorporating driving-style recognition and trajectory prediction, the proposed method enables the ego vehicle to anticipate surrounding maneuvers earlier, thereby reducing motion uncertainty and avoiding last-moment evasive actions [

45,

46]. This leads to smoother interaction strategies and more proactive risk mitigation, which ultimately enlarges the safety buffer and further validates the effectiveness of the enhanced prediction–decision framework.

4.2.3. Emissions Assessment

To quantitatively evaluate the carbon emission performance under different autonomous driving decision strategies, this study establishes a set of microscopic-level emission evaluation metrics based on an instantaneous emission rate model. Let the distance time steps be

with a sampling interval of

, and denote the instantaneous emission rate as

. The total emissions for a single trip can be expressed as:

The total distance traveled during the trip is computed as:

From the total emissions and total distance, the per-kilometer emission is calculated as:

This set of metrics allows for a consistent comparison of different autonomous driving strategies, linking instantaneous vehicle behavior to aggregate emission performance before further graphical and statistical analysis.

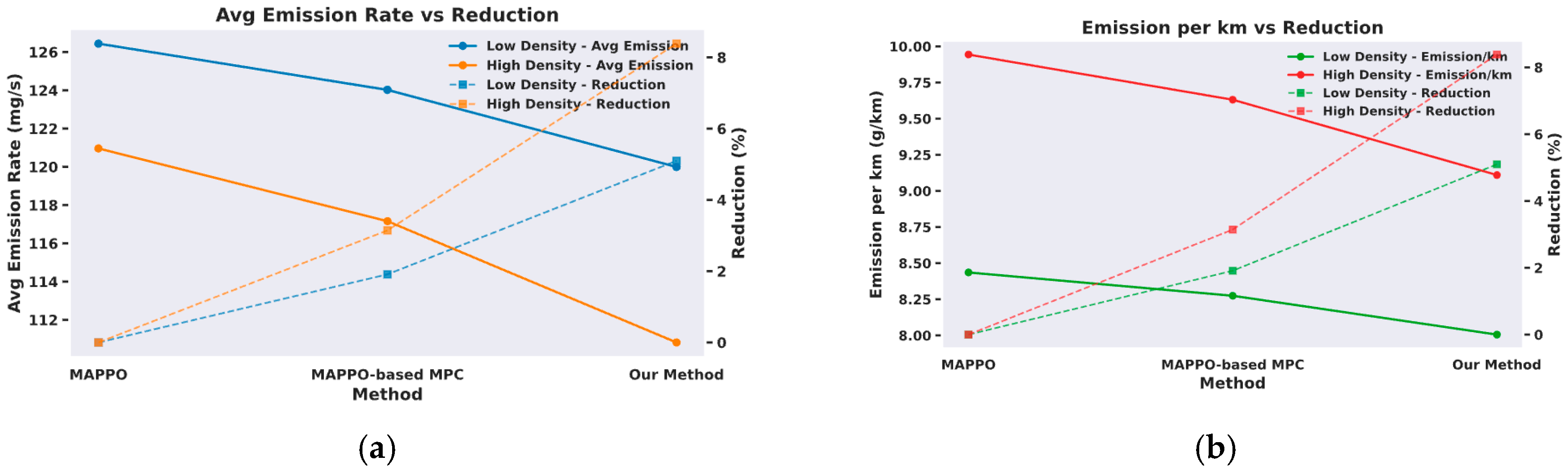

Figure 8 shows the variations in average emission rate (mg/s) and the corresponding carbon emission per kilometer (g/km), reflecting both instantaneous emission intensity and overall trip efficiency. Under the proposed method, emissions decrease from 126.44 mg/s to 120.0 mg/s (8.01 g/km) in low-density traffic, and from 120.96 mg/s to 110.82 mg/s (9.11 g/km) in high-density traffic, corresponding to reductions of 5.1% and 8.4%, respectively. These results indicate that the strategy effectively lowers carbon emissions by smoothing acceleration and regulating longitudinal control, with greater benefits under high-density conditions where frequent stop–go maneuvers amplify emission fluctuations.

4.2.4. Bayesian Inference Assessment

To evaluate the effectiveness of the Bayesian inference model in short-term prediction tasks, six sets of experiments were conducted with prediction horizons of 1 s, 2 s, and 3 s. The model integrates both ego-vehicle states and surrounding vehicle dynamics, including relative speed, distance, and lane position. By employing a Bayesian inference module, the method explicitly models the uncertainty of the predicted trajectory distribution during the inference phase, enabling probabilistic forecasting of future positions.

The prediction accuracy is quantitatively assessed using the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and Final Displacement Error (FDE) [

47], defined as follows:

where

and

denote the predicted and ground-truth positions at time step

, and

is the final prediction horizon.

As shown in

Figure 9, both RMSE and FDE increase gradually as the prediction horizon extends from 1 s to 3 s, reflecting the accumulation of predictive uncertainty over time. Under low-density conditions, the mean RMSE increases from 0.673 m (1 s) to 1.352 m (3 s), while FDE grows from 0.867 m to 1.850 m. This corresponds to an overall growth factor of 2.06× in RMSE, indicating a moderate accumulation of position deviation with time.

In contrast, under high-density conditions, the mean RMSE rises from 0.783 m to 1.868 m, and FDE from 0.923 m to 2.216 m, yielding a larger growth factor of 2.58×. This suggests that in dense traffic, not only are absolute errors higher, but the rate of error accumulation is also significantly faster. Such behavior highlights the nonlinear amplification effect of vehicle-to-vehicle interactions and trajectory uncertainty when surrounding vehicles’ motion becomes strongly coupled.

Although the RMSE values clearly increase with the prediction horizon, the magnitude of growth between RMSE-3s and RMSE-1s suggests that long-term errors are not merely an accumulation of short-term uncertainty. Instead, the larger deviation observed beyond 3 s likely stems from discrete driving decisions such as lane-changing and merging conflicts, which introduce abrupt trajectory deviations that cannot be captured by continuous kinematic prediction alone. This indicates that beyond short-range horizons, the stochasticity of interactive behaviors becomes the dominant source of prediction error.

Overall, even within a 3 s forecast horizon, the proposed Bayesian inference model maintains the mean RMSE and FDE within approximately 1.5–2.0 m across different densities, demonstrating robust generalization and credible short-term forecasting accuracy in complex multi-agent environments.

4.2.5. Ablation Study

To assess the effectiveness of the proposed method, we performed an ablation study in which the MPC module was removed from the framework. By comparing this ablated variant with the complete method, we evaluate the isolated contribution of MPC to overall performance in terms of efficiency, safety, and robustness across different traffic scenarios.

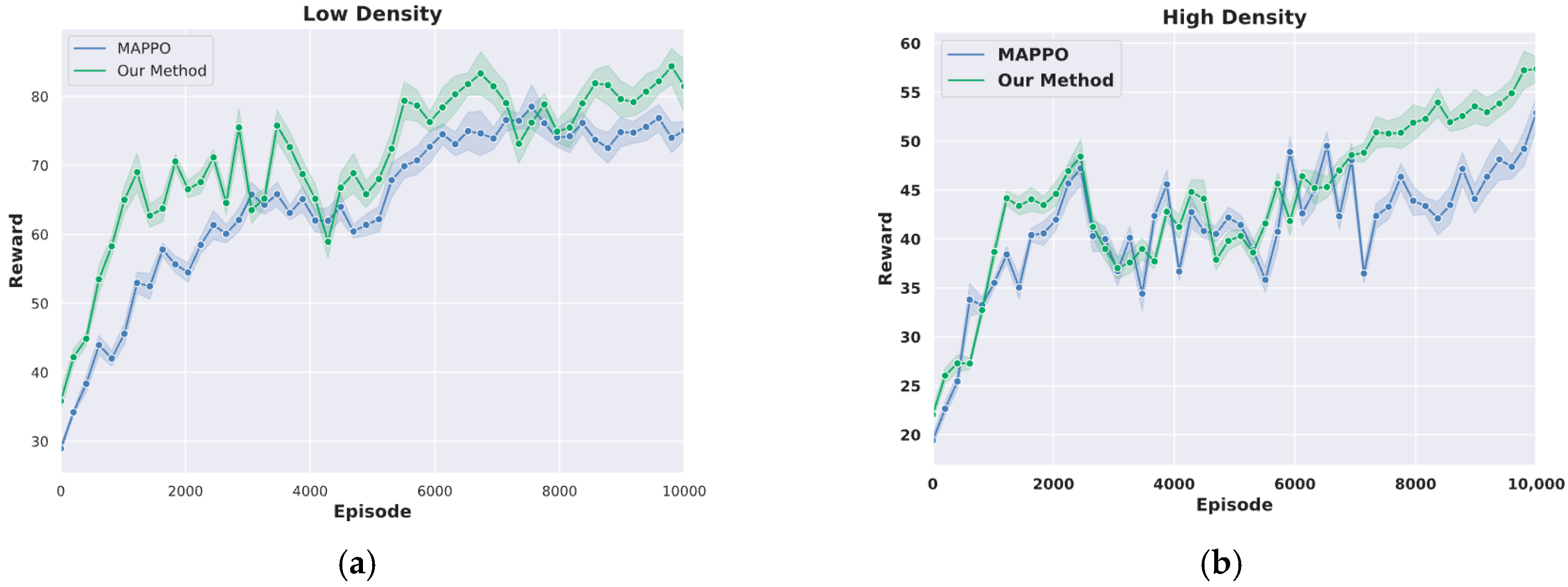

Overall Performance: As shown in

Figure 10a, the average reward curves during training reveal that our method exhibits a relatively gradual improvement in the early stages, but after approximately 8000 episodes, the average reward rapidly increases to 74.25 and finally stabilizes at 83.30. In contrast, the baseline MAPPO converges to only 75.31, representing an improvement of about 10.6%. As shown in

Figure 10b, in high-density scenarios, our method achieves an average reward of 58.28, exceeding the baseline MAPPO’s 52.38 by 11.26%. Moreover, our method demonstrates superior performance stability. In the low-density scenario, our method achieved an average speed of 25.52 m/s, compared with 23.03 m/s for baseline MAPPO (an improvement of 10.81%). In the high-density scenario, although average speeds of both methods declined to around 22 m/s due to congestion, our method exhibited a smaller standard deviation, indicating more stable driving performance.

These results clearly indicate that the integration of the Bayesian–MPC prediction module significantly improves agent performance, with reward values enhanced by approximately 10% compared with baseline MAPPO. Notably, under higher traffic density and increased environmental complexity, our method continues to maintain strong performance, demonstrating superior robustness and adaptability.

Safety Analysis: To assess safety, we conducted 30 randomized scenario tests across different traffic densities and measured the collision rate, defined as the proportion of collision steps relative to the total steps. Results are shown in

Table 7. Our method achieved collision rates of 0.00 (low density) and 0.01 (high density), while baseline MAPPO achieved 0.00 under low density but rose to 0.03 in high density. We also evaluated robustness in heterogeneous traffic scenarios containing HVs.

In summary, simulation experiments and analysis confirm that our method effectively improves driving safety across multiple traffic scenarios and demonstrates strong generalization ability in high-density and complex environments.

4.2.6. Algorithm Comparison

In this subsection, we employ two representative multi-agent reinforcement learning algorithms, MAACKTR and MAA2C, as comparative baselines to evaluate the proposed framework. The comparison across different traffic scenarios enables a comprehensive assessment of safety, efficiency, comfort, and carbon-emission performance.

The proposed method exhibits clear advantages in safety, efficiency, and robustness across both low- and high-density traffic conditions. As shown in

Figure 11, performance improvements are consistent when compared with MAACKTR and MAA2C. In low-density scenarios, our method achieves a high evaluation reward of 83.30, outperforming MAACKTR and MAA2C by 40.9% and 31.4%, respectively, while maintaining a zero-collision rate. The average speed increases to 25.52 m/s, representing over 10% improvement relative to both baselines.

In high-density scenarios, our method similarly attains the highest evaluation reward (58.28), exceeding MAACKTR by 7.11% and MAA2C by 16.62%, while reducing the collision rate to 0.01. The average speed also increases to 22.72 m/s, corresponding to 10.08–15.15% gains over MAACKTR and MAA2C. These results indicate that our approach demonstrates stronger foresight and more stable control under dense interactions.

Beyond quantitative improvements, the learned policies reveal interpretable behavior patterns: style-aware priors guide smoother acceleration, more consistent following distances, and reduced unnecessary lane changes, contributing to enhanced safety and driving comfort. Supported by the comparative metrics summarized in

Table 7, these findings confirm that the proposed Bayesian style-aware framework not only delivers superior performance but also translates into safer, more efficient, and more human-aligned driving strategies in mixed-traffic environments.

By leveraging driving style recognition and the rolling optimization mechanism of MPC, the proposed method can proactively identify potential conflicts and avoid high-risk situations, leading to substantial safety improvements even in complex, high-density environments. Beyond safety, the style-aware reward function effectively constrains acceleration fluctuations and jerk, ensuring smoother motion profiles and enhanced ride comfort despite tighter control constraints. Furthermore, the integration of multi-step prediction and behavioral priors enables the policy to maintain stable performance under diverse interaction patterns, thereby enhancing robustness and generalization capability.

Collectively, these results confirm that the proposed approach achieves a balanced advancement in safety, comfort, and robustness by unifying predictive optimization with adaptive behavior modeling.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents an integrated autonomous driving decision-making framework that unifies Bayesian driving style inference, risk-aware trajectory prediction, and multi-agent cooperative reinforcement learning within a closed-loop “Identification–Prediction–Decision” architecture. By embedding Bayesian trajectory inference into the MPC module, the framework enhances multi-step motion prediction under uncertainty, enabling vehicles to anticipate potential conflicts and maintain safe, smooth trajectories. The recognition of heterogeneous driving styles provides high-level semantic priors that guide adaptive policy updates, improving decision robustness in complex mixed-traffic environments. Furthermore, through smoothing acceleration profiles and suppressing abrupt maneuvers, the proposed method effectively balances safety and comfort while reducing carbon emissions. This integration of predictive reasoning, behavioral semantics, and ecological awareness demonstrates a comprehensive advancement in safety, robustness, and sustainability for autonomous driving systems.

Despite the promising results, the prediction accuracy, particularly RMSE, tends to degrade over longer horizons, indicating the need for more advanced sequential models such as LSTM for future trajectory prediction [

44]. Additionally, the current study mainly considers simple lane-change scenarios, and future work will extend to more complex settings involving intersecting lanes and denser traffic interactions.