Abstract

Rural destinations face a difficult challenge in balancing economic vitality with the environmental and infrastructural pressures, including congestion of car-dependent destinations. Despite growing calls for more sustainable mobility, destination management organisations (DMOs) can assume that private vehicles are vital for rural access, fearing that alternatives such as soft mobility or public transport may have an adverse effect on visitor satisfaction and spending. Yet, empirical evidence to support or challenge these assumptions remains limited. This study addresses this gap by analysing visitor survey data (N = 512) from international and domestic tourists to a rural destination in County Clare, Ireland. Using one-way and two-way ANOVA, along with chi-square and logistic regression analyses, we examine how transport mode relates to visitor satisfaction, daily expenditure, and overnight stay behaviour. Results revealed that visitor satisfaction does not significantly differ across transport modes, suggesting that sustainable mobility options (e.g., walking, cycling, public transport) do not impact the visitor experience. While transport mode had a minimal impact on spending overall, overnight visitors, regardless of how they travelled, spent significantly more than day-trippers (p < 0.001), identifying length of stay as the key economic driver. Moreover, soft mobility users (walking and cycling) had a higher likelihood of staying overnight than car users, while tour bus users were significantly less likely to do so. However, among those who did stay overnight, tour bus users reported the highest daily spending, revealing a complex relationship between mobility type and economic impact. Overall, the results question long-held assumptions linking car use with rural tourism success. Low-impact transport options, such as soft mobility and public transport, were found to sustain visitor satisfaction and spending outcomes comparable to car travel, suggesting their integration could contribute to more balanced, sustainable mobility planning.

1. Introduction

Visitor mobility is increasingly recognised as a determining factor for the sustainability of a rural destination [1,2,3,4]. Globally, destination management organisations (DMOs) and policymakers increasingly face challenges in balancing visitor access with sustainability, as rural areas remain heavily dependent on private cars and have limited public transport for both visitor access and resident travel [5,6,7]. This over reliance creates congestion, emissions and infrastructure pressures [4,8,9,10]. In response, some destinations have had to introduce measures such as alternating licence plate systems [11], creating enforcement costs for authorities and disrupting the visitor experience. Still, a persistent assumption exists—that the mode of car travel is necessary to secure visitor satisfaction and to achieve local economic benefits [12,13]. Some of these assumptions are justified based on practical realities such as a lack of other infrastructure and funding for other modes of transport such as cycling in rural destinations [14]. There has been evidence of private cars remaining widely accepted as the ‘rural transport solution’ [15], with most tourists in the Swedish destination of Sälen choosing cars despite the availability of alternatives [15]. However, how do these visitor choices impact the visitor experience and the resulting spend in the rural destination? Interestingly, there has been some evidence that visitors arriving by bus reported higher satisfaction levels than those using rental cars in cities [16]. However, empirical studies in rural destinations have been limited. As a result, policy and planning decisions often continue to prioritise car-based access over sustainable mobility alternatives, despite a lack of supporting evidence.

This mobility dilemma unfolds within a broader, global, socio-economic context. Rural areas support approximately 44% of the world’s population and are essential for sustaining food production, biodiversity, and cultural heritage [17]. Yet, rural regions continue to face population decline, economic marginalisation, and infrastructural challenge—with 83% of the world’s population living in poverty in rural areas [6,15]. In response, rural tourism has been promoted as a strategy for regeneration, supporting local employment, and sustaining rural communities. In the face of this, destination management organisations (DMOs) and policymakers now recognise that within destination planning in delicate rural environments, rural mobility presents both a constraint and an opportunity. However, without empirical evidence to support destination strategies, DMOs are restricted to traditional methods of supporting visitor travel. To date, most research on rural mobility has emphasised environmental [3,18] impacts, particularly the need to reduce transport-related emissions [16,17,18]. This a fair approach, as it has been well-established that transport makes up the largest aspect of tourism’s environmental emissions [19]. While this aspect must inform an essential basis for a destination’s environmental strategy, it also highlights what is missing: understanding how such transitions in mobility coincide with visitor satisfaction and spending. Without evidence on whether sustainable transport alternatives maintain or improve visitor experience, meaningful policy change remains speculative. As researchers have argued [9,20], satisfaction and expectations should be central to applied sustainable tourism models when adopting a visitor-centred perspective [9,21], particularly in rural destinations where visitors are constrained by transport options.

For instance, evaluating tourist satisfaction and behavioural responses in sustainable tourism models, particularly in rural settings where visitor expectations and infrastructural practicalities may differ, is essential [20]. This raises a critical question—if lower-impact modes of travel result in lower visitor satisfaction or reduced spending, can they realistically be considered viable alternatives? While the environmental rationale is clear, broader adoption must align mobility solutions with visitor expectations and economic outcomes if DMOS are to adopt change. UN Tourism underscores this need, identifying transport and digital connectivity as key enablers of sustainable rural development [17], stating that collaboration with transport agencies and strategic investment are needed to improve access, services, and the well-being of both visitors and rural communities. To support the required collaboration between destination managers, transport agencies, and local communities to improve access and to improve overall well-being of both residents and visitors in rural areas, this study empirically examines whether low-impact transport modes—specifically soft mobility (defined here as non-motorised movement such as walking or cycling) and public transport—can deliver levels of visitor satisfaction and economic contribution comparable to private car use. This study adds to the growing discussion on sustainable mobility in rural destinations by offering empirical evidence in an area where quantitative research is still limited. In contrast to much of the existing literature, which tends to focus on urban contexts [22], this research explores how visitor satisfaction, daily spending, and overnight behaviour vary across transport modes, highlighting how mobility shapes both experience and local economic outcomes. By directly comparing high- and low-impact travel options, including walking, cycling, and public transport, as alternatives to private car use, the study questions long-standing assumptions that car dependency is a necessity for rural tourism success. The findings provide practical insight into both transport and destination planning, showing that low-impact travel can maintain high satisfaction and support greater economic value when linked to overnight stays. Overall, the study offers new evidence to guide rural mobility strategies that balance competitiveness with environmental and community sustainability.

2. Theoretical Framework

This study draws on three complementary theoretical perspectives to interpret the relationship between transport mode, visitor satisfaction, and spending in rural tourism. Firstly, the expectancy-disconfirmation theory provides a lens to understanding tourist satisfaction. This theory proposes that satisfaction is felt when travel experiences meet or exceed expectations [23]. In rural tourism, this could be shown through access via tour buses, public transit, or private cars, shaping perceptions of convenience, comfort, and value. Applying this theory allows us to examine whether differences in mobility transposes into differences in visitor satisfaction. Secondly, tourism economic impact theories, such as that proposed by Bryden [24], frame the examination of visitor spending patterns. Visitor spending is a well-established key measurable contribution of rural tourism [25]. Spending levels vary by type of travel and length of stay, with overnight visitors often spending more money through accommodation, dining, and activities within destinations. Transport mode also informs visitor patterns—visitors travelling by tour bus may have more structure and be limited by infrastructure itineraries, while car users can disperse spending more flexibly across rural communities. This framework underpins our examination of whether transport choices affect economic spending within a rural destination. Thirdly, the mobilities paradigm [26,27] highlights that mobility is not merely a means of transport but shows that the act and method of travel informs part of the tourist experience itself. It is shown that modes of travel influence how visitors experience landscapes, interact with local communities, and perceive their visit to rural destinations. In destinations where car-dependence is often assumed necessary [12,13], this theory challenges whether varying types of transport systems can sustain visitor access and travel without negatively impacting visitor experiences. Using this lens supports the position of transport as not only an environmental concern, but as a key aspect of rural tourism planning.

Examined together, these theories provide a framework: expectancy-disconfirmation connects transport with satisfaction, tourism economic impact theories align mobility with local economic spend, and the mobilities paradigm presents the concept that transport choices themselves inform the tourist experience.

3. Research Questions

Our study directly addresses a research gap by analysing the relationship between transport mode, visitor type (day vs. overnight visitor), and two outcome variables, satisfaction and daily spending, through visitor surveys from visitors (international and domestic) to a rural destination in County Clare, Ireland. To explore how mobility choices intersect with visitor experience and economic contribution in a rural context, the following research questions were established:

- Research Question 1: Do satisfaction levels differ across transport modes?

- Research Question 2: Do spending patterns vary by transport mode?

- Research Question 3: Can low-impact transport modes (e.g., soft mobility, public transport) support high visitor satisfaction and economic contribution?

- Exploratory Question: Do soft mobility or tour bus users differ in overnight stay odds compared to car users?

This research addresses a critical gap in the literature by examining rural mobility with both the experiential and economic contributions of tourism. Although similar research has been conducted on urban environments [16], our findings have implications for tourism development in rural settings. In particular, for transport planning and marketing strategies, especially in destinations aiming to balance visitor access and economic contributions with sustainability.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Collection

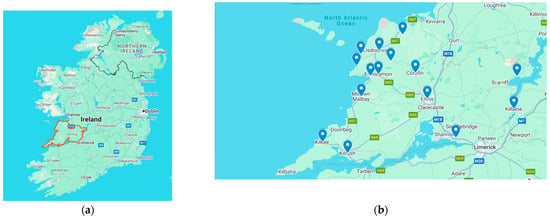

Primary data were collected through a structured visitor survey, with a sample size of 512 valid responses across the research destination of County Clare (Figure 1a). Approximately 90% of responses were gathered in person by the researchers at sites highlighted in Figure 1b while the remaining 10% were gathered online via QR codes displayed at key attraction sites. Data collection took place across between June 2022 and February 2023. The survey targeted both international and domestic visitors and recorded visitor market, transport modes, spending patterns, and satisfaction levels against indicators through the European tourism indicator system (ETIS), as shown in Table 1. Daily expenditure was collected from day visitors, which aligned with the ETIS indicator B.1.5 ‘Daily spending per same day visitor’. This included daily spending within the destination on food, travel, retail, etc. Daily spending per overnight tourist included accommodation, food and drinks, other services, as defined by ETIS indicator B.1.4 ‘Overnight Spend’. Visitor satisfaction was measured on a 5-point Likert scale, consistent with prior tourism mobility studies [9,20] and as described by ETIS indicator A.2.1 ‘Percentage of visitors that are satisfied with their overall experience in the destination’.

Figure 1.

(a) Geographical location of the research destination on the west coast of Ireland (County Clare). (b) Visitor survey location collections in County Clare between the period of June 2022–February 2023.

Table 1.

The European tourism indicators [28] used in the study.

In early field work, demographic questions were kept to a minimum to encourage participation during in-person data collection. Variables such as age, gender, and income were excluded to reduce perceived intrusiveness and respondent burden, which are noted as barriers for field-based research [29,30] and researchers in the field. However, demographic profiles from the National Tourism Agency [31,32] and other academic surveys [33] conducted within the destination were used to provide context for visitor demographic profiles. These external datasets were not included in the statistical analysis to avoid non-aligned sampling results but were used to support interpretation of the study’s findings.

4.2. Variables

- Transport mode: Car, tour bus, local public transport, walking, cycling, camper van, and others (ETIS indicator D.1.2).

- Expenditure: Self-reported spending per day in euros (ETIS indicators: B.1.4 and B.1.5).

- Satisfaction of visit: Likert scale (1 = very dissatisfied, 5 = very satisfied) (ETIS indicator: A.2.1).

- Overnight stay: Binary (Yes/No) (ETIS indicator: B.2.1).

4.3. Research Questions, Hypotheses, and Statistical Tests

This study addresses four research questions examining relationships between transport mode, overnight stay, visitor satisfaction, and spending behaviour of visitors. For each, null and alternative hypotheses were established. All statistical analyses were conducted using R (version 4.5), with effect sizes reported where applicable.

- Research Question 1: Do satisfaction levels differ across transport modes?

- Null hypothesis (H01): There is no statistically significant difference in visitor satisfaction between transport modes.

- Alternative hypothesis (H11): Visitor satisfaction differs significantly across transport modes.

Statistical test: One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD post hoc comparisons. Effect sizes were measured using partial eta-squared (η2) and Cohen’s f.

- Research Question 2: Do spending patterns vary by transport mode and visitor type (overnight vs. day-visitor)?

- Null hypothesis (H02): There is no statistically significant difference in visitor spending per day across transport modes or between overnight visitors and day-trippers.

- Alternative hypothesis (H12): Visitor spending per day differs significantly by transport mode and/or visitor type.

Statistical test: Two-way ANOVA (transport × overnight), with Tukey’s HSD for post hoc contrasts. Effect sizes reported using η2 and Cohen’s f.

- Research Question 3: Can low-impact transport modes (e.g., public transport, soft mobility) support high visitor satisfaction and economic contribution?

- Null hypothesis (H03): Visitors using low-impact transport modes (public transport and soft mobility) report no difference in satisfaction or spending compared to car users.

- Alternative hypothesis (H13): Visitors using low-impact transport modes (public transport and soft mobility) report significantly different satisfaction and/or spending compared to car users.

Statistical test: Targeted contrasts drawn from the ANOVA models, comparing low-impact modes with car users (Tukey-adjusted).

Exploratory Research Question: Do soft mobility or tour bus users differ in overnight stay odds compared to car users?

- Null hypothesis (H04): Odds of staying overnight do not differ by transport mode.

- Alternative hypothesis (H14): Odds of staying overnight differ significantly by transport mode.

Statistical Test: Pearson’s chi-square test of independence, with effect size assessed using Cramer’s V. Follow-up binary logistic regression (dependent variable: overnight stay Y/N; reference category: car users) reported as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals.

Although the research questions are presented separately for clarity, the analyses were carried out within a single, integrated framework. Insights from RQ1 and RQ2, which explored visitor satisfaction and daily spending, informed the combined analysis in RQ3. RQ4 then built on these results by examining patterns of overnight stay, placing the statistical findings within a wider understanding of visitor mobility and its links to economic behaviour at destination level.

Statistical Models Utilised

To ensure reproducibility, all analyses were conducted using standard parametric models. A one-way ANOVA was first applied to test differences in visitor satisfaction across transport modes (RQ1), followed by a one-way and two-way ANOVA to test daily spending patterns and the interaction between transport mode and overnight stay (RQ2–RQ3). These tests examined both main effects and interaction terms to identify whether satisfaction or spending varied significantly by travel mode or visitor type (overnight or day visitor). For RQ4, a chi-square test of independence and a binary logistic regression were used to examine the association between transport mode and the likelihood of staying overnight. The logistic model provided odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals to highlight how overnight behaviour differed by transport mode. Significance levels were set at α = 0.05. Effect sizes were reported using partial eta-squared (η2) and Cohen’s f for ANOVA models and odds ratios (ORs) for logistic regression outcomes.

5. Results

After screening for validity, 512 survey responses (n = 512) were collected (as shown by Table 2), providing a sufficient statistical sample for analysis at the 95% confidence level (z = 1.96) with a margin of error of approximately ±4.3% relative to an annual visitor population in 2023, which was 1.3 million [34].

Table 2.

Demographic of visitor sample of research survey.

Although age, gender, and socio-demographic data were not directly collected within this survey, data from National and site-level datasets were referred to for contextual references of visitor profiles within the same sampling timelines.

Table 3 summarises secondary data visitor demographic profiles for County Clare and Ireland (2022–2023), providing contextual reference for this study. National and destination-level data show a predominantly mature visitor base, with 43% of domestic visitors aged 55+ and 40% of overseas visitors aged 25–44 years. The Cliffs of Moher Experience (2024) reports a similar mid-age distribution (27–58 years) and a balanced gender split (52% female/48% male). Socio-economic indicators suggest that 55% of Clare’s leisure visitors belong to higher professional groups (ABC1).

Table 3.

Summary of secondary data visitor demographic profiles (Co. Clare and Ireland, 2022–2023).

5.1. RQ1—Satisfaction Across Transport Modes

To assess whether satisfaction levels differed across transport modes, a one-way ANOVA was conducted. Results (as shown in Table 4) showed no statistically significant differences in visitor satisfaction across cars, tour bus, soft mobility, or public transport users, F (3, 507) = 1.07, p = 0.361. The effect size was trivial (η2 = 0.006; Cohen’s f = 0.08), and post hoc Tukey tests revealed no significant pairwise differences (all p ≥ 0.31). Satisfaction levels were uniformly high (Figure 2) across all groups (M = 4.8, SD = 0.55), with 1 measuring ‘Not satisfied at all’, to 5 ‘Very Satisfied’ for their visit, suggesting that transport choice had a negligible impact on visitor experience.

Table 4.

Results of one-way ANOVA test showing no statistically significant difference in visitor satisfaction across transport modes (p = 0.361).

Figure 2.

Visitor satisfaction (1 = low, 5 = high) by transport mode used within the destination. Grey violins show the distribution of satisfaction scores; points represent individual respondents; black circles with error bars indicate mean satisfaction (M = 4.8, SD = 0.55 overall) and 95% confidence intervals for each transport mode. Sample sizes (n) are shown above each group.

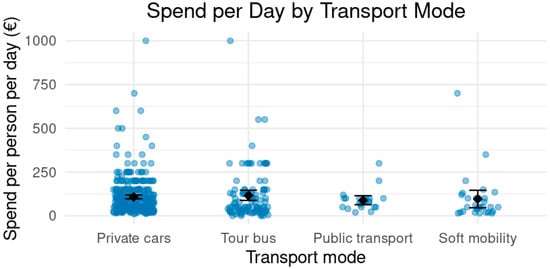

5.2. RQ2—Daily Spending by Transport Mode and Overnight Visitors

A one-way ANOVA was conducted to examine whether daily visitor spending differed by transport mode. It initially showed no significant differences in daily spending across transport modes, F (3, 490) = 0.53, p = 0.663 (Table 5).

Table 5.

Results of one-way ANOVA showing no significant difference in daily spending across transport modes (ANOVA, p = 0.663).

However, further analysis using a two-way ANOVA (Table 6) revealed significant main effects for both transport mode (F (3, 486) = 4.28, p = 0.005, η2 = 0.009) and overnight status (F (1, 486) = 83.85, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.147), as well as a significant interaction between the two (F (3, 486) = 8.94, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.052).

Table 6.

Two-way ANOVA for daily spending by transport mode and overnight status.

Additional post hoc comparisons showed that among day visitors spending did not differ significantly by transport mode (p > 0.90). In contrast, among overnight visitors those travelling by tour bus spent significantly more per day (€250.6) than car users (€135.1), walkers (€114.4), cyclists (€96.7), and public transport users (€99.7) (p < 0.001), as shown in Figure 3. These results highlight that overnight stay status, rather than transport mode alone, is the key reason for spending.

Figure 3.

Results showing visitor spend per day per transport mode.

5.3. RQ3—Can Low-Impact Transport Support Satisfaction and Spending?

To examine whether low-impact modes, e.g., soft mobility or public transport, can support high satisfaction and spending relative to car use, a two-way ANOVA was conducted (Table 7). No significant differences were observed in satisfaction between car and low-impact users (F (1, 488) = 0.21, p = 0.808, η2 < 0.001). Likewise, overnight status did not significantly affect satisfaction (F (1, 488) = 2.59, p = 0.108), and the interaction was non-significant (F (1, 488) = 0.71, p = 0.491).

Table 7.

Two-way ANOVA results for visitor satisfaction and daily spending (dependent variables) with transport mode and overnight stay as fixed factors.

In terms of daily spending, the main effect of transport was marginal (F (1, 488) = 2.52, p = 0.081), but overnight stay remained highly significant (F (1, 488) = 111.06, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.190) with a significant interaction (F (1, 488) = 6.26, p = 0.002). These findings confirm that low-impact transport modes do not reduce satisfaction and may support comparable or higher spending—especially when tied with overnight stays.

5.4. RQ4—Association Between Transport Mode and Overnight Stay

To examine whether transport mode influences visitor behaviour beyond satisfaction and spending, we examined its association with overnight stay likelihood. A chi-square test revealed (Table 8) a statistically significant association between transport mode and the likelihood of staying overnight, χ2 (3, N = 511) = 27.58, p < 0.001, Cramer’s V = 0.23. The proportion staying overnight was highest among soft mobility users (78.1%), followed by public transport users (65.2%) and car users (61.3%), and lowest among tour bus travellers (36.4%).

Table 8.

A chi-square test indicated a significant association between transport mode and overnight stay, χ2 (3, N = 511) = 27.58, p < 0.001, Cramer’s V = 0.23.

A logistic regression (using the baseline of car users) showed that tour bus users were significantly less likely to stay overnight (OR = 0.36, 95% CI [0.23, 0.56], p < 0.001), while soft mobility users were more likely to stay (OR = 2.25, 95% CI [0.99, 5.78], p = 0.066). Public transport users did not differ significantly from car users (p = 0.710). These findings suggest that soft mobility may encourage overnight stays, while tour buses are primarily associated with day visits within the examined destination.

6. Discussion

6.1. Rethinking Assumptions of Car-Dependent Satisfaction

The findings of this study challenge assumptions in rural tourism policy and planning that correlate high visitor satisfaction with private car use. Rural tourism policy and planning often assume that private car access is essential for achieving high visitor satisfaction and access, e.g., self-drive solutions in tourism planning [35]. However, across all transport modes in this study, including soft mobility and public transport, satisfaction remained uniformly high, with no identified statistically significant differences between transport modes. These results suggest that visitor satisfaction in a rural destination in County Clare may be shaped more by the assets provided by the destination itself and the experienced services than by the convenience or perceived requirement of private car travel. This visitor satisfaction coincides with results seen in similar urban studies [9,16,20] and reinforces the relevance of the expectancy-disconfirmation theory [23] in explaining how expectations interact with experience, including across transport types.

6.2. Economic Benefits: A Measure of Length Stay and Not Transport Mode

Spending outcomes revealed that measure of overnight stay (or day visitation) was the main account of visitor expenditure. Although no significant differences were found in daily spending across transport modes in the overall sample, a more nuanced result was highlighted among overnight visitors. Private car and tour bus users accounted for the majority of respondents, reflecting their current, central role in the economy of this rural destination in Co. Clare. This pattern aligns with broader visitor demographics reported for the destination, with mid- to older-aged and higher-income visitors accounting for the majority of visitors [31,32,33]. Such groups of visitors lean towards convenience-oriented travel [36], in particular, organised tours or private car use, and can report greater spending capacity [37]. Tour bus travellers—traditionally associated with shorter visits and lower spend—reported the highest per-day spending; however, this was importantly driven by a smaller sample who stayed overnight in the destination. It is recognised that visitor income and demographic characteristics play an important role in shaping both transport choices and spending behaviour. According to Fáilte Ireland in 2023 [32], 55% of Clare’s leisure visitors fall within higher professional socio-economic groups (ABC1). The visitor profile is also relatively mature, with 43% of domestic visitors aged 55 or older and 40% of overseas visitors between 25 and 44 years of age [31]. Together, these patterns point to a market with comparatively high disposable income and a preference for convenience and comfort-focused travel methods.

The higher daily expenditure recorded among overnight tour bus visitors may therefore reflect the presence of medium- to high-income travellers who can afford multi-day, higher-value packages rather than the inherent effect of the transport mode itself. Even so, this remains a meaningful result in a rural tourism context. As short, low-spend coach excursions experienced by global destinations, such as brief stops at the Cliffs of Moher, are still common, identifying circumstances where organised tours generate stronger per-visitor returns offer valuable guidance for destination planning. These findings suggest that coach travel is not intrinsically low value; however, its contribution depends largely on the inclusion of overnight stays and the nature of the tour. These results point to the complexity of spending patterns and suggest that transport mode alone does not reliably measure economic impact. Instead, the visitors’ length of stay appears to be the factor that dictates the relationship between mobility and economic contribution. Similar findings have been observed in other rural destinations, where group travel generated high per capita spend only when associated with overnight itineraries [6,38]. It is acknowledged that the demographic make-up of visitors to the destination [31,32,33] may have influenced the results. Older and higher-income travellers—who account for a significant share of Clare’s tourism market—often measure higher overall satisfaction [37] and are more inclined to use convenient or/and premium modes of transport. This may partly explain the consistently high satisfaction levels observed across groups. Future studies that include detailed age and income segments could help to uncover further nuances in how visitor characteristics interact with mobility choices and associated economic outcomes. These findings have important implications for rural tourism planning. Rather than focusing on increasing visitor numbers, rural destinations, such as Clare, may gain more by encouraging longer overnight stays and improving access through practical, lower-impact transport options.

6.3. Mode of Transport and Overnight Stays

The exploratory analysis in this study showed a significant association between transport mode and likelihood of a visitor’s overnight stay. Visitors that travelled through soft mobility options (cycling or walking) were more likely to stay overnight than those using private cars or tour buses, with soft mobility users 2.25 times more likely to stay (p = 0.066). Tour bus visitors, on the other hand, were significantly less likely to stay overnight, reinforcing observed results in other contexts where coach-based tourism showed shorter but more concentrated visits [39]. These findings highlight that transport choice is not just a logistical aspect, but one that can influence broader visitor behaviour while travelling within a destination. While private cars currently support most of rural tourism’s overnight market, the potential of soft mobility to support a destination’s economic benefit by extending length of stay deserves further attention in transport and destination planning.

The link between mobility and overnight stay deserves further attention. Walkers and cyclists often travel at a slower pace and seek more immersive experiences, which can naturally lead to longer visits [40,41], route-based adventure and exploration, or multi-day itineraries. In contrast, car users usually have greater flexibility in distance and timing, making shorter or day trips more feasible. These differences suggest that soft mobility visitors may form a distinct type of traveller—one with stronger potential for local economic benefit through extended engagement and increased length of stay within the destination. This pattern highlights an opportunity for further research into the motivations, trip purposes, and route-based behaviours of soft mobility visitors to better understand how they contribute to sustainable rural tourism.

In this context, our findings coincide with the tourism carrying capacity literature [42,43], which highlights that managing visitor flows and impacts may be more effective than targeting increasing per capita spend within destinations. This implies that destinations may risk facing increased issues of congestion, parking pressure, and environmental degradation [44] without maximising economic gains if car access continues to be the destinations’ primary method of transport.

6.4. Implications for Planning and Policy

For rural destinations, such as the study destination of County Clare, the findings suggest that reducing car dependency is not necessarily at odds with maintaining high visitor satisfaction or supporting economic contribution. In fact, the lack of shown significant differences in satisfaction or spending across transport modes supports planning for low-impact mobility infrastructure. Given the demographics of mid- to older-ages and higher-income visitors to the destination [31,32,33], planning for increasing sustainable mobility options for visitors should include strong accessibility and convenience aspects to ensure alignment with the older adult demographic of the destination [45,46].

In particular, the study implies that investment in walking and cycling infrastructure and integrated public transport could increase destination accessibility without compromising competitiveness, an outcome aligned with the UNWTO’s sustainable rural tourism frameworks for competitiveness [17]. This is particularly relevant as visitor generational transitions are expected to shape visitor mobility expectations. As younger, sustainability aware generations, e.g., Millennials and Generation Z, represent a growing percentage of the tourism market, the demand for active and lower-impact transport is likely to rise [47]. Moreover, given that overnight visitors contribute more economically, strategies that combine sustainable transport options with incentives or infrastructure for overnight accommodation may produce effective dual benefits, i.e., increased access to accommodation through such transport modes. Without such integration, destinations risk reinforcing the current observed pattern where the economically valuable tourists (in terms of numbers) remain tied to the most environmentally intensive and congestion-inducing modes of travel [48,49], i.e., car use.

6.5. Study Limitations and Future Research Directions

It is acknowledged that these findings are from a single rural setting in one destination. As such, further research is required to validate whether the observed patterns will be shown across other rural destinations. Additionally, although transport mode, satisfaction, and spending were measured quantitatively, further insight into visitor motivations, perceptions of access, and preferences of transport mode could be examined through qualitative methods. A further limitation of this study is that detailed demographic data such as age, gender, or income were not collected, which limits the ability to analyse accessibility needs or socio-economic influences in greater depth. This decision was shaped by both methodological and practical considerations linked to in-field data collection in rural visitor settings. Previous research has shown that questions on age, gender, or income can be perceived as intrusive or overly personal, particularly in interviewer-administered surveys, and may lead to higher refusal rates [29]. During early fieldwork, the researchers observed similar reactions, with some respondents showing visible discomfort or withdrawing when these questions were asked [39].

To maintain engagement and to ensure a statistically sound sample size was achieved, the questionnaire was therefore refined to focus on visitor behaviour, mobility, satisfaction, spending, and sustainable transport practices. Future studies could address this limitation by using anonymous online formats, which might reduce the sensitivity of demographic questions while remaining mindful of the potential bias toward digitally engaged respondents. Because income and purchasing power were not directly measured, some of the observed relationships between transport mode and spending may reflect underlying socio-economic demographics of visitors. Including income and related indicators in future research would help to clarify the extent to which visitor spending power shapes travel behaviour and economic outcomes. Additionally, the survey was conducted primarily during the summer peak season (June–September 2022), with limited sampling in the winter months. As such, the findings most strongly reflect visitor behaviour during the period of highest tourism activity. While Ireland experiences relatively moderate seasonal variation, winter weather may reduce soft mobility use (walking and cycling). Future studies could include additional seasonal data to assess whether these observed patterns remain consistent year-round.

Furthermore, future studies may benefit from adopting a mixed-methods approach, as recommended in other sustainability indicator studies [50]. This approach could help capture the nuanced relationship between infrastructure, experience, and visitor behaviours. Finally, it would also be beneficial for longitudinal designs to be conducted to support stronger claims about successes in investment in sustainable mobility and the observed measurable changes in overnight stays or economic outcomes over time within destinations.

7. Conclusions

This study challenges the idea that private car use is essential to creating value in rural tourism. Across all transport modes, visitors reported similarly high levels of satisfaction, while spending was influenced mainly by how long people stayed rather than how they travelled. Soft mobility users were more likely to stay overnight, suggesting that low-impact travel can support longer, higher-value visits. In contrast, tour bus travellers who did not stay overnight spent the least, while those who stayed overnight recorded the highest daily spend. This points to the need to look beyond simple mode comparisons and recognise that different forms of travel contribute in different ways—soft mobility by encouraging longer engagement and organised tours by generating concentrated spending. Overall, the findings point to a potential for reducing car dependence without compromising rural tourism performance. Supporting walking, cycling, and public transport infrastructure—alongside high-value overnight options, including those linked to tour bus travel—can help rural destinations, such as Clare, to strengthen the local economy and ease environmental and congestion pressures while maintaining high levels of visitor satisfaction and spend.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.J.M. and J.H.; Methodology, F.J.M. and J.H.; Software, F.J.M.; Validation, F.J.M. and J.H.; Formal analysis, F.J.M.; Investigation, F.J.M. and J.H.; Resources, J.H.; Writing—original draft, F.J.M.; Writing—review & editing, F.J.M. and J.H.; Visualization, F.J.M.; Supervision, J.H.; Funding acquisition, J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Atlantic Technological University (formerly IT Sligo) through the President’s Bursary Scheme.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institute Research Ethics Committee of Technology, Sligo (protocol code 2022006, 28 February 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study, as determined by the Ethics Approval of Atlantic Technological University.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Høyer, K.G. Sustainable tourism or sustainable mobility? The Norwegian case. J. Sustain. Tour. 2000, 8, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashper, K.E. Rural Tourism: An International Perspective; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. Tourism and Rural Development: Understanding Challenges on the Ground—Lessons Learned from the Best Tourism Villages by UNWTO Initiative; World Tourism Organization (UNWTO): Madrid, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Ahonen, V.; Karasu, T.; Leviäkangas, P. Sustainability of smart rural mobility and tourism: A key performance indicators-based approach. Technol. Soc. 2023, 74, 102287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fáilte Ireland. Wild Atlantic Way Regional Tourism Development Strategy; Fáilte Ireland: Galway, Ireland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. Recommendations on Tourism and Rural Development—A Guide to Making Tourism an Effective Tool for Rural Development; World Tourism Organization (UNWTO): Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Tourism and the Sustainable Development Goals—Journey to 2030; World Tourism Organization (UNWTO): Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Guidance for a More Sustainable Mobility in Rural Tourism Regions; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- An, W.; Alarcón, S. How can rural tourism be sustainable? A systematic review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiftung, H.B. European Mobility Atlas. Facts and Figures About Transport and Mobility in Europe. 2021. Available online: https://eu.boell.org/European-Mobility-Atlas (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Distretto Turistico Costa D’Amalfi. Distretto Turistico Costa dAmalfi-Traffic Regulation System. 2024. Available online: https://distrettocostadamalfi.it/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Distretto-Turistico-Costa-dAmalfi-Traffic-Regulation-Sytem-2024.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- AlAli, A.M.; Hassan, T.H.; Abdelmoaty, M.A. Tourist Values and Well-Being in Rural Tourism: Insights from Biodiversity Protection and Rational Automobile Use in Al-Ahsa Oasis, Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briedenhann, J.; Wickens, E. Tourism routes as a tool for the economic development of rural areas-vibrant hope or impossible dream? Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UTIP. The Rural Mobility Challenge for Public Transport: How Combined Mobility Can Help: Knowledge Brief. 2022. Available online: https://www.sutp.org/files/contents/documents/resources/H_- (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Waleghwa, B. Rethinking car-dependent rural tourism mobility. Appl. Mobilities 2025, 10, 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.C.; Román, C.; Moreira, P.; Moreno, R.; Oyarce, F. Does the access transport mode affect visitors’ satisfaction in a World Heritage City? The case of Valparaiso, Chile. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021, 91, 102969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. Tourism for Rural Development Programme—Impact Report 2021–2024; UN Tourism: Madrid, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loras-Gimeno, D.; Díaz-Lanchas, J.; Gómez-Bengoechea, G. Rural depopulation in the 21st century: A systematic review of policy assessments. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2025, 17, 100176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conefrey, A.; Hanrahan, J. Climate Change and Tourism: The Carbon Footprint of Irish Tourism; Atlantic Technological University: Galway, Ireland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, G.; Popescu, C.A.; Iancu, T.; Brad, I.; Peț, E.; Adamov, T.; Ciolac, R. Sustainability through Rural Tourism in Moieciu Area-Development Analysis and Future Proposals. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, L.; Lu, C.; Chen, X. Evaluation of Rural Tourism Resources Based on the Tourists’ Perspective: A Case Study of Lanzhou City, China. J. Resour. Ecol. 2022, 13, 1087–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poltimäe, H.; Rehema, M.; Raun, J.; Poom, A. In search of sustainable and inclusive mobility solutions for rural areas. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2022, 14, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. A Cognitive Model of the Antecedents and Consequences of Satisfaction Decisions. J. Mark. Res. 1980, 17, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryden, J.M. Tourism and Development: A Case Study of the Commonwealth Caribbean; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.L.; Chiang, J.T.; Ko, P.F. The benefits of tourism for rural community development. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urry, J. The New Mobilities and Transport; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sheller, M.; Urry, J. Mobilizing the new mobilities paradigm. Appl. Mobilities 2016, 1, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The European Tourism Indicator System ETIS Toolkit for Sustainable Destination Management; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutwin, S. Current Knowledge and Considerations Regarding Survey Refusals. 2014. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Timothy-Johnson-9/publication/265413651_Current_Knowledge_and_Considerations_Regarding_Survey_Refusals_AAPOR_Task_Force_on_Survey_Refusals_Prepared_for_AAPOR_Council_by_the_Task_Force_on_Survey_Refusals_operating_under_the_auspices_of_the_A/links/540e49b70cf2df04e756ce16/Current-Knowledge-and-Considerations-Regarding-Survey-Refusals-AAPOR-Task-Force-on-Survey-Refusals-Prepared-for-AAPOR-Council-by-the-Task-Force-on-Survey-Refusals-operating-under-the-auspices-of-the-A.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Menold, N.; Zuell, C. Reasons for Refusals, Their Collection in Surveys and Interviewer Impact. GESIS—Leibniz-Institut für Sozialwissenschaften Lennéstraße 30, 53113 Bonn. 2010. Available online: https://www.gesis.org/fileadmin/upload/forschung/publikationen/gesis_reihen/gesis_arbeitsberichte/Working_Paper_2010_11_online.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Fáilte Ireland. Key Tourism Facts 2023 What Was Overseas Tourists Main Reason for Visiting Ireland? Fáilte Ireland: Galway, Ireland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Fáilte Ireland. Key Tourism Facts 2023; Fáilte Ireland: Galway, Ireland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Deegan, J.; Sánchez, E.B. Cliffs of Moher Experience Activity Report 2024. National Centre for Tourism Policy Studies. Clare County Council. 2024. Available online: https://share.google/Nm0en4EErLVLy9njm (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Failte Ireland. Visitor Numbers to Attractions Dashboard; Fáilte Ireland: Galway, Ireland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Paulino, I.; Zaragozí, B.; Medina-Chavarria, M.E.; Gutiérrez, A. Designing Public Transportation Services for Car-Dependent Rural Destinations: An Application in the Case of the Ebro Delta (Spain). Int. J. Tour. Res. 2025, 27, e70037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazeminia, A.; Del Chiappa, G.; Jafari, J. Seniors’ Travel Constraints and Their Coping Strategies. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Gursoy, D. An Investigation of Tourists’ Destination Loyalty and Preferences. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2001, 13, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Global trends in length of stay: Implications for destination management and climate change. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 2087–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becken, S.; Simmons, D. Using the concept of yield to assess the sustainability of different tourist types. Sci. Direct 2008, 67, 402–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, J.; Lumsdon, L. Slow Travel and Tourism, 1st ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, J.E.; Lumsdon, L.M.; Robbins, D. Slow travel: Issues for tourism and climate change. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 281–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. Can. Geogr. 1980, 24, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESPON. Carrying Capacity Methodology for Tourism (Final Report); ESPON EGTC: Nagano, Japan, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pino, J.B.; Garcia, D.B.; Zapico, E.; Mayor, M. Optimal carrying capacity in rural tourism: Crowding, quality deterioration, and productive inefficiency. Tour. Mangement 2024, 105, 104968. [Google Scholar]

- Ravensbergen, L.; Van Liefferinge, M.; Isabella, J.; Merrina, Z.; El-Geneidy, A. Accessibility by public transport for older adults: A systematic review. J. Transp. Geogr. 2022, 103, 103408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utama, I.G.B.R.; Susanto, P.C. Destination Development Model for Foreign Senior Tourists. J. Bus. Hosp. Tour. 2016, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketter, E. Millennial travel: Tourism micro-trends of European Generation Y. J. Tour. Futures 2020, 7, 192–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proost, S. What Sustainable Road Transport Future? Trends And Policy Options; OECD: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Banister, D. Reducing the Need to Travel. Environ. Plann. B Plann. Des. 1997, 24, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, F.; Hanrahan, J. Meaningful community engagement through advanced indicator systems for sustainable destination planning. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2024, 22, 100392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).