Abstract

Understanding the dynamics of Land Resource Carrying Capacity (LRCC) under rapid urbanization requires not only retrospective assessment but also operational tools for supporting future planning. This study develops a spatially explicit LRCC framework for Xuchang City (2000–2020) that integrates economic, land-use, and resource subsystems, and encodes key policy instruments as time-varying variables. Entropy weighting is used as a data-driven baseline for indicator aggregation, with robustness checks conducted using equal weighting and the analytic hierarchy process (AHP). Results show that Xuchang’s citywide LRCC increased from 0.56 in 2000 to 0.81 in 2020, corresponding to a 44.6% rise over the study period. This growth exhibits marked spatial heterogeneity across the urban area and is closely associated with changes in urbanization level, industrial restructuring, and land development intensity. The overall pattern of LRCC change is robust to alternative weighting schemes, supporting the comparability of the estimates across time. To explore potential futures, a scenario-based simulation is conducted in which a +2% increase in urbanization rate and a −10% reduction in land development intensity are translated into LRCC responses, yielding a predicted increase of about +0.023 (from 0.81 to approximately 0.833). This scenario illustrates how the framework can be used to evaluate trade-offs and synergies among development and conservation objectives. By quantifying the contributions of policy-related and socio-economic indicators to LRCC dynamics, the study provides an evidence-based tool for optimizing land governance and promoting sustainable urban development in rapidly urbanizing regions.

1. Introduction

Rapid urban expansion has imposed unprecedented pressures on land systems in developing countries, particularly in China, where accelerated urbanization has reshaped land-use patterns and tightened resource constraints. Against this backdrop, Land Resource Carrying Capacity (LRCC)—integrating land availability, ecological resilience, and socio-economic demand—has become a critical metric for assessing sustainable urban development [1]. Beyond China, LRCC is increasingly invoked across rapidly developing economies in Asia, Africa, and Latin America as a decision-support framework for balancing economic growth with ecological preservation under binding land constraints.

A first body of LRCC research foregrounds ecological functions and environmental thresholds [2,3,4,5,6]. Early studies moved from the simple human–grain relationship to more complex, ecosystem-service-based perspectives [3,4,5], and to assessments of land productivity under ecological constraints [6]. This work sharpens the notion of biophysical limits and clarifies how ecological thresholds bound human activities. However, it tends to treat urbanization as an exogenous pressure and often relies on static snapshots that underplay temporal change and feedbacks. Recent city-level analyses that add a “carrier–load” perspective for major Chinese cities highlight precisely this limitation, calling for dynamic rather than purely static assessment under rapid urban growth [7]. Taken together, ecological approaches establish necessary thresholds, yet they insufficiently capture socio-economic feedbacks and spatio-temporal heterogeneity in fast-urbanizing regions [8]. Complementing these ecological studies, a second strand quantifies how economic development and land-use intensity shape LRCC [9,10,11,12]. Provincial-scale evaluations that combine cultivated, construction, and ecological land provide tractable indices for comparing development pressures [10]. Such models are valuable for policy screening at broad scales, but two weaknesses recur across studies. First, ecological resilience and policy interventions are frequently absorbed into composite indices rather than modeled explicitly. Second, indicator weighting schemes often rely on expert judgement, which can reduce comparability across time and space. Moreover, many analyses are conducted at regional or provincial scales, which risks masking intra-urban heterogeneity that is salient for city governance [11,12].

In response to these limitations, more recent studies assemble ecological, socio-economic, and land-use indicators within integrated, multi-criteria frameworks. Relative carrying capacity approaches combine single-factor and composite evaluations across cultivated, construction, and ecological land [13], while methodological reviews document the spread of entropy weighting and GIS-based spatialization and note the emerging, but still immature, use of multi-scale, dynamic, and machine-learning evaluations [14]. These frameworks represent a shift from inventorying indicators to synthesizing land systems. Nonetheless, important gaps remain: urban governance and policy are often treated qualitatively or as background context, and temporal dynamics at the city scale are still under-specified. A growing literature recognizes that zoning regulations, farmland protection “red lines”, and expansion controls—exemplified by major strategic initiatives such as the Xiongan New Area—play a formative role in shaping land-use trajectories and thus LRCC [15]. Yet, most studies do not quantitatively couple specific policy instruments with LRCC trajectories, offer limited analysis of spatial heterogeneity in policy effects, and under-specify temporal responses to policy shifts [16,17]. As a result, policy frequently remains a black box in LRCC frameworks, even though it is central to how land systems evolve in practice. Existing city-scale and temporal assessments (e.g., provincial-city panels and multi-year composites) therefore provide only a partial picture when policy is treated as contextual narrative rather than as time-varying, measurable levers within the modeling framework.

This study addresses these gaps by developing a spatially explicit LRCC framework for Xuchang (2000–2020), in which concrete policy instruments are operationalized as time-varying variables and aligned with land-use/land-cover change (LUCC) and LRCC dynamics at the city scale. We encode policy events and intensities and link them spatio-temporally to LRCC and LUCC, interpreting estimated relationships as associations rather than causal effects, given the three-period data structure. Methodologically, we combine GIS-based spatial analysis with data-driven indicator weighting and document-based coding of policy instruments to quantitatively couple governance with LRCC. Entropy weighting is used as a baseline scheme, and robustness is examined by comparing alternative weighting approaches (equal weighting and analytic hierarchy process, AHP) to enhance cross-regional comparability.

Our objectives are threefold: (1) to evaluate the spatio-temporal evolution of LRCC in Xuchang from 2000 to 2020; (2) to identify the dominant policy drivers associated with LRCC dynamics; and (3) to derive governance implications for land optimization in rapidly urbanizing regions. By integrating policy instruments explicitly into a dynamic, city-scale LRCC framework, this study aims to contribute both methodologically and empirically to the sustainable management of land resources in developing-country urban systems.

2. Study Area and Data

2.1. Study Area and Description

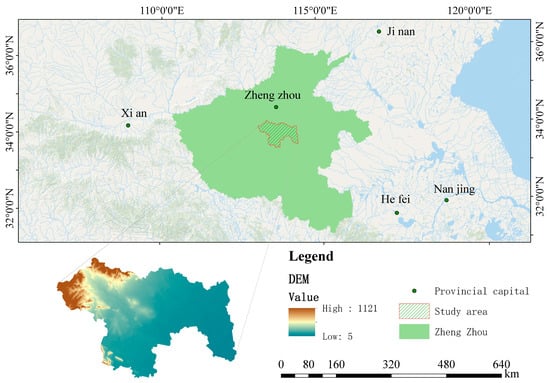

Xuchang City (33°42′ N to 34°24′ N) lies in central Henan Province, China, covering approximately 4996 km2 (Figure 1). It is a strategic node within the Central Plains Urban Agglomeration [18], connecting the provincial capital Zhengzhou to surrounding cities. Administratively, Xuchang comprises two municipal districts (Weidu and Jian’an), two county-level cities (Yuzhou and Changge), two counties (Xiangcheng and Yanling), and the Xuchang Economic and Technological Development Zone (ETDZ; established in 1994; statistical boundary per (Xuchang Statistical Yearbook) [19]).

Figure 1.

The study area in China.

The study area lies on the eastern edge of the Huang-Huai-Hai Plain, dominated by flat alluvial plains (>70%) with small hilly regions to the west [20,21]. The climate is warm temperate continental monsoon, with mean annual temperature 14.3–15.2 °C and annual precipitation 670–730 mm, mostly in summer [22].

From 2000 to 2020, Xuchang experienced rapid urbanization and industrial restructuring. The urbanization rate rose from about 20% in 2000 to over 50% in 2020 [23]. It was accompanied by substantial expansion of construction land mainly in central districts and along transport corridors, and concurrent reduction in cultivated land (especially dry farmland). Local policies, such as permanent basic farmland delineation and reforms on collective land entry into the market, have been implemented to mitigate ecological stress and improve land-use efficiency [24]. These geographic and institutional transitions make Xuchang a representative inland case for studying LRCC dynamics under combined pressures of urban development and policy change.

2.2. Data Sources

A multi-source dataset was compiled to evaluate the spatio-temporal evolution of LRCC in Xuchang City from 2000 to 2020, integrating satellite imagery, land-use maps, socio-economic indicators, policy documents, and auxiliary geospatial layers. A comprehensive inventory of datasets, acquisition years, and sources is provided in Supplementary Table S1, which includes detailed information on data types, sources, resolution, and their specific purpose in the study.

1. Remote sensing data.

Landsat imagery was obtained from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), including Landsat 5 TM (2000–2011), Landsat 7 ETM+ (2000–2013, SLC-off after 2003), and Landsat 8 OLI (2013–2020). For each analysis year, cloud-free images were selected within the July–September seasonal window to minimize phenological effects. Preprocessing included the following:

- Radiometric calibration;

- Atmospheric correction using LaSRC (for OLI) and LEDAPS (for TM/ETM+);

- Geometric rectification to WGS84 geographic (EPSG:4326);

- Cloud masking using the Fmask algorithm;

- Gap filling for SLC-off Landsat 7 data using temporal interpolation with adjacent-date imagery.

2. Land-use classification and validation.

Land-use/land-cover (LULC) mapping was performed using human–machine interactive visual interpretation. They were derived from high-resolution Google Earth imagery and field surveys conducted in 2020, with 50 independent validation points. Five land-cover types were classified, including construction land, farmland, forest land, water bodies, and unused land. LUCC data came from the Institute of Geographic Sciences and Resources, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Its classification was primarily based on human–computer interactive visual interpretation. To ensure the accuracy of the LUCC classification, systematic validation based on field observations was performed. Specifically, the verification points along representative transects were performed, which were then used for field investigations to validate the accuracy of the remote sensing interpretation of LUCC types. The validation process involved systematic point selection to ensure that the sample locations were representative of the broader study area. The accuracy of each LUCC type interpretation was checked based on these samples. The comprehensive evaluation showed that the remote sensing interpretation accuracy was 95.66%.

3. Socio-economic and resource indicators.

Socio-economic data, including (Gross Domestic Product) GDP, population, agricultural output, industrial value, and available water resources, were collected from the Xuchang Statistical Yearbook and related government bulletins (2000–2020). All indicators were normalized using min–max normalization prior to entropy-weight computation (see Section 3 for formulas). To produce raster-based LRCC maps, administrative-level data were disaggregated to a 1 km × 1 km grid using an area-weighting approach.

4. Policy documents and auxiliary layers.

Major land-related policy documents, including the Xuchang Land Use Master Plan (2001), Basic Farmland Redline (2014), and New Urbanization Strategy (2014), were collected from municipal and provincial government websites. Policy implementation years and spatial coverage were temporally coded for integration into LRCC trend analysis. All spatial datasets were initially referenced to the WGS84 geographic coordinate system (EPSG:4326). For area calculations and overlay analyses, datasets were reprojected to an Albers Equal-Area projection (standard parallels 25° N and 45° N, central meridian 105° E).

3. Methodology

3.1. Evaluation Framework of LRCC

To evaluate the sustainability of land use under rapid urbanization, LRCC was conceptualized as a composite index that captures the dynamic balance between land system pressure and its supporting capacity. Building upon existing theoretical frameworks and considering the specific socio-economic and ecological context of Xuchang City, a multi-criteria evaluation framework was established, following three core principles. Theoretical relevance indicators should reflect key dimensions of LRCC; data availability—long-term, spatially consistent, and statistically reliable data must be accessible; indicator independence—redundancy and multicollinearity among indicators should be minimized.

The framework integrates three interrelated subsystems (Table 1), each representing a critical dimension of land system sustainability. First, economic support subsystem reflects the socio-economic demands placed on land resources. Four indicators were selected, such as GDP, output value of the primary industry, output value of the secondary industry, and land development intensity. Second, resource supply subsystem represents the ecological and environmental carrying capacity of land systems. It includes total grain output, available water resources, population density, and unused land rate. Third, industrial capacity subsystem measures functional land-use efficiency and industrial structure. It consists of output of large-scale industrial enterprises, total agricultural machinery power, number of hospital beds, and urbanization rate.

Table 1.

Multi-level index system for evaluating LRCC and data sources.

These 12 indicators (Table 1) were selected based on their theoretical importance, sensitivity to urbanization-driven land transformation and the availability of long-term data. The consistent statistics from authoritative sources included the Xuchang Statistical Yearbook, Agricultural Statistics Yearbook, Health and Medical Yearbook, and Water Resources Bulletin.

3.2. Entropy Weighting and Composite Index Construction

To ensure comparability across indicators with different units and scales, all raw data were first standardized prior to index construction. Indicators were classified as positive or negative, depending on whether higher values contribute to stronger or weaker LRCC, respectively. To avoid numerical instability when max(Xi) = min(Xi) for any indicator (i.e., zero variance), a small constant epsilon (ε = 1 × 10−9) was added to the denominators of the normalization equations. This ensured that the normalized value was not affected by zero variance and maintained computational stability. For positive indicators (GDP, grain output, available water resources), the i-th indicator in sample j (year or region) was normalized using min–max scaling.

For negative indicators (population density, land development intensity, unused land rate), an inverse transformation was applied and followed by min–max scaling:

Here denoted the original (raw) value of indicator i in sample j, max() and min () were the maximum and minimum values of indicator i across all samples, and ϵ [0, 1] was the normalized value. When max() = min() for any indicator (i.e., zero variance), the standardized value was set to 0.5 for all samples of that indicator. To avoid numerical instability, a small constant ε = 1 × 10−9 was added to denominators where needed [25,26].

1. Entropy calculation.

Following normalization, entropy weighting was applied to objectively determine the importance of each indicator. Entropy measured the degree of variability; indicators with larger variation across time or space contribute more information, thereby receiving higher weights. The entropy value ei of indicator i was calculated as follows [27].

Here, n represented the total number of evaluation units, which in our case were the administrative regions (e.g., Weidu, Jian’an, Yuzhou, etc.). pij represented the proportional contribution of the j-th observation for indicator i. Following normalization, entropy weighting was applied to objectively determine the importance of each indicator. Entropy measured the degree of variability. The indicators with larger variation across time or space contributed more information, thereby receiving higher weights. The entropy value ei was calculated as follows [28]. The entropy weighting method was used to calculate the weight of each indicator based on its variability across the study period. It was originally described by [29] and further applied in land-use and environmental studies [30].

2. Degree of diversification and weight assignment.

The degree of diversification di for indicator i was defined as the previous study [31].

The entropy weight wi for indicator i was then calculated as follows.

where m was total number of indicators. A higher di corresponded to a higher wi, indicating that the indicator contributed more to differentiating LRCC levels across years or regions.

3. LRCC composite index construction.

Finally, the composite LRCC index for each evaluation unit was computed as a weighted linear combination of the standardized indicators [32].

where LRCCj denoted the composite score for the j-th unit (e.g., year or administrative region), wi was the entropy-derived weight, and x’ij was the standardized value. This approach ensured that indicators with greater discriminatory power, showing larger spatial or temporal variability, made proportionally larger contributions to the overall LRCC index. Compared to subjective weighting methods, the entropy-based approach provided an objective and data-driven representation of indicator importance, minimizing researcher bias.

4. Indicator weights.

Table 2 listed the 12 indicators used in the LRCC composite index, along with their entropy-derived weights. Indicators exhibiting higher dispersion across years and regions, such as GDP, urbanization rate, and land development intensity, received greater weights, reflecting their stronger influence on LRCC differentiation. To ensure methodological transparency, Supplementary Table S2 presented representative samples of raw, normalized, and weighted indicator data used in the LRCC computation. These samples illustrated the entropy-weighting procedure described above and correspond to the indicator weights summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Indicator system and entropy weights for LRCC evaluation.

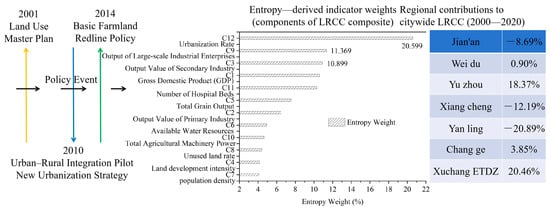

Table 2 reports the entropy weights (Wi) and direction handling for the 12 indicators used in the LRCC composite. To help readers situate the policy timeline–weighting–regional-contribution workflow at a glance, Figure 2 provides an integrated overview that links (1) the sequencing of major policy phases (2000–2020), (2) the entropy-weighting procedure introduced in this section, and (3) where regional contributions to LRCC are computed within the workflow. For a direct visualization of the relative weights Wi, please refer to Supplementary Figure S3; numerical values are those in Table 2. The numerical results and interpretation of regional contributions are presented in Results (Section 4.2 and Section 4.3) and discussed in Section 5.2.

Figure 2.

Integrated schematic linking policy timeline, entropy-derived indicator weights, and regional contributions to LRCC (2000–2020).

3.3. Benchmarking and Validation

We benchmark the entropy-weighted LRCC against two alternatives: (1) an equal-weight composite and (2) an AHP composite (consistency ratio CR < 0.10). Cross-scheme agreement is high: the citywide spatial ordering and the signs of 2000–2020 growth remain invariant, and a simple scatter comparison indicates close concordance of absolute LRCC values. We validate the LRCC surfaces using leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) and report RMSE/MAE in Section 4.3, with full diagnostics in the Supplement. Importantly, the policy-scenario results are robust to the weighting scheme: under the combined scenario defined in Section 3.6 (S3; +2% in the urbanization rate C12 and −10% in land development intensity C4), the entropy-weighted estimate yields ΔLRCC ≈ +0.0226, while the equal-weight estimate yields ΔLRCC ≈ +0.0246; the interpretation is unchanged. Given three benchmark years, all policy–LRCC links are interpreted as associational rather than causal. For completeness, the cross-scheme table is provided as Supplementary Table S4.

3.4. GIS-Based Spatio-Temporal Analysis

To investigate the spatial and temporal dynamics of LRCC in Xuchang City over the 20-year period from 2000 to 2020, GIS techniques were used to process, analyze, and visualize both spatial indicators and composite LRCC scores.

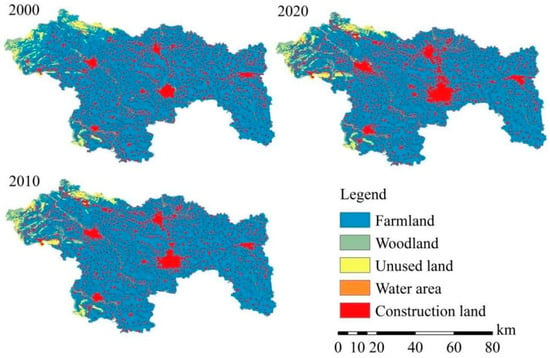

3.4.1. LUCC Analysis

LUCC data were derived from Landsat imagery for the years 2000, 2010, and 2020. The images were classified into five major categories: construction land, farmland, woodland, water area, and unused land. Classification was conducted using a supervised classification approach, with training samples defined for each land-cover type. The accuracy of classification was validated through field surveys and cross-validation with ground-truth data to ensure reliability. First, for LUCC classification and transition mapping, post-classification comparisons were applied to quantify land-use transitions and identify spatial conversion trajectories across the three periods. Change matrices and spatial overlay analyses in QGIS 3.82 were used to calculate the areal conversion among land-use types. Supplementary Table S5 summarizes the LUCC transition statistics, highlighting the dominant conversion processes such as construction land expansion and corresponding farmland reduction. The detailed spatial distribution and temporal trends of these transitions are presented in Section 4.1. Second, for post-classification comparison, the post-classification comparison method enabled tracking of land-use conversions between time periods and quantified the magnitude of each change. Construction land growth and farmland loss were mainly concentrated in peri-urban zones, while woodland and water bodies showed relatively minor variation. This analytical procedure provided the basis for interpreting LUCC dynamics and their linkage with LRCC evolution, as discussed in the Results section.

3.4.2. Spatial Interpolation of LRCC Values

To examine the spatial distribution patterns of LRCC across Xuchang City, spatial interpolation was conducted using the Inverse Distance Weighting (IDW) method in QGIS 3.82. The IDW approach was chosen for its robustness in capturing continuous spatial variations and its suitability for medium-scale urban–rural contexts such as Xuchang. In this method, each sample point contributes to the interpolated surface with a weight inversely proportional to its distance from the target cell. The parameters used for IDW were a power of 2 and a neighbor search radius of 15 points, which ensured adequate spatial smoothing while preserving local variation.

To assess interpolation accuracy, LOOCV was applied, yielding validation metrics such as the root mean square error (RMSE) and mean absolute error (MAE) for each time period. The detailed results of the LOOCV and residual spatial patterns are provided in Supplementary Table S6 and Figure S7. Due to the irregular administrative boundaries and heterogeneous data distribution in Xuchang, IDW was selected over alternative interpolation techniques such as Kriging or Spline. Unlike Kriging, which assumes a specific spatial autocorrelation model and is computationally intensive, IDW uses a deterministic weighting function that does not rely on statistical distribution assumptions. This makes it a practical and transparent choice for analyzing LRCC surfaces in this study. The resulting spatial interpolation maps for 2000, 2010, and 2020 are presented in Section 4.1.

3.4.3. Temporal Comparison and Change Mapping

To characterize the spatio-temporal evolution of LRCC, raster difference maps were produced for three intervals—2000–2010, 2010–2020, and 2000–2020. Each raster layer represents the pixel-wise change in LRCC scores between consecutive years, derived from the composite index surfaces generated in previous steps.

These maps quantitatively depict how LRCC varied across time and space, identifying both regions of significant improvement and areas of stagnation. Urban centers and development zones exhibited the largest positive changes, while peripheral agricultural counties showed slower increases or localized declines. The raster-based approach provided a reliable means to visualize the direction and intensity of LRCC change across Xuchang, forming the analytical foundation for the temporal-phase analysis presented in Section 4.1.2.

3.5. Policy Variables, Measurement, and Driver Analysis

We code policy timing (e.g., Land-Use Master Plan 2001; Farmland Redline 2014–2016; New Urbanization 2014→) and spatial coverage/intensity (e.g., share of protected farmland; construction land quota orientation; district-level policy jurisdiction) as time-varying attributes, then align them with LRCC change maps and LUCC transitions at the administrative-unit level. Specifically, we (i) compute Spearman rank correlations between LUCC indicators (e.g., construction land expansion rates) and LRCC changes by period, (ii) perform simple permutation tests to assess whether the observed correlations could arise by chance, and (iii) conduct grouped trend contrasts across districts with different baseline exposure to farmland protection and ecological constraints (Section 5.2). These checks provide light-weight, design-based controls for confounding under our three-period setting. Given only three benchmark years and seven districts, full econometric control is infeasible. Instead, we adopt a design-based triangulation strategy combining pre-trend checks, grouped contrasts, and efficiency-without-expansion indices to mitigate confounding.

The analysis of policy–LRCC linkages in this study adopted a spatio-temporal policy-event alignment framework rather than a formal causal modeling approach. Because LRCC and policy data were available for only three benchmark years (2000, 2010, and 2020), econometric regression or quasi-experimental inference was not feasible. Instead, the study integrated qualitative and spatial-quantitative methods to systematically identify how land governance policies coincided with changes in LRCC across time and space. This framework combines three complementary components. First, document-based policy coding—major land governance and urbanization policies implemented in Xuchang between 2000 and 2020 were identified and categorized (e.g., zoning and land-use planning, farmland protection, and regional integration initiatives). Second, spatial overlay analysis-raster-based LRCC difference maps and LUCC data were spatially overlaid with administrative boundaries to link observed capacity changes to specific policy jurisdictions. Third, temporal alignment—the timing of key policy interventions was matched with corresponding LRCC changes to determine the direction and relative magnitude of policy–capacity associations.

This integrated design enabled a structured evaluation of policy–LRCC associations rather than strict causality. The approach captured both spatial and temporal correspondence between policy implementation and LRCC dynamics, providing an empirical foundation for identifying policy-linked spatial heterogeneity.

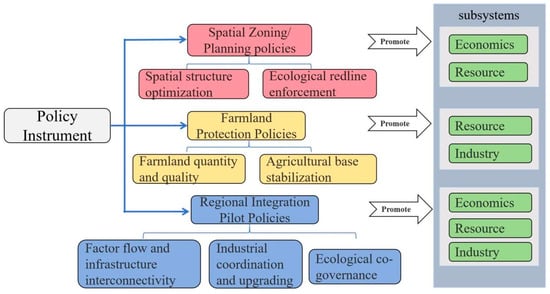

Figure 3 conceptually illustrated how three major policy categories (spatial zoning and planning, farmland protection, and regional integration pilots) influenced the economic, resource, and industrial subsystems of LRCC through distinct pathways. Arrows indicate the direction of influence between policy instruments, intermediate mechanisms, and LRCC subsystems.

Figure 3.

Conceptual schematic of policy–LRCC subsystem linkages. Arrows indicate the direction of influence between policy instruments, intermediate mechanisms, and LRCC subsystems.

3.6. Scenario Evaluation Protocol and Working Example

We project scenario outcomes by applying the fixed-weight LRCC composite to normalized indicator targets. Let Wi denote the indicator weights (Table 2) and Zi the 2000–2020 min–max normalized indicator values anchored to 2000–2020 (direction handled so that higher is always better for LRCC). For a post-2020 target, the normalized change is ∆Zi. The LRCC change is approximated by

∆LRCC ≈ ∑iWi·∆Zi

With full recomputation LRCC = ∑iWi·Zi. Normalized values are capped to [0, 1] for the normalization anchors and the KPI example. Table 3 reports anchors for the urbanization rate (C12) and land development intensity (C4). Using 2000–2020 min–max, a +2% urbanization increase (50→52%) gives ∆ZC12 = 0.063; a −10% reduction in land development intensity (16.33→14.70) gives ∆ZC4 = 0.232, with entropy weights WC12 = 0.20599 and WC4 = 0.04153 (Table 2). ∆LRCCC12 ≈ 0.20599 × 0.063 ≈ 0.0130, ∆LRCCC4 ≈ 0.04153 × 0.232 ≈ 0.0096. Combined, ∆LRCC ≈ 0.0226. Given the 2020 citywide LRCC baseline = 0.81 = 0.81 = 0.81, the scenario raises LRCC to ≈0.833. This quantitative demonstration shows how concrete KPI shifts translate into LRCC gains, establishing the framework’s operational utility. Because ∂LRCC/∂Zi = Wi, a +0.10 increase in any normalized indicator yields 0.10 × Wi LRCC points. Table 3 reports per-indicator leverage for practical targeting (weights from Table 2).

Table 3.

Policy-to-LRCC leverage by indicator (ΔLRCC per +0.10 increase in min–max normalized value; 2000–2020 anchors; entropy weights from Table 2).

4. Results

4.1. Spatio-Temporal Changes in LRCC (2000–2020)

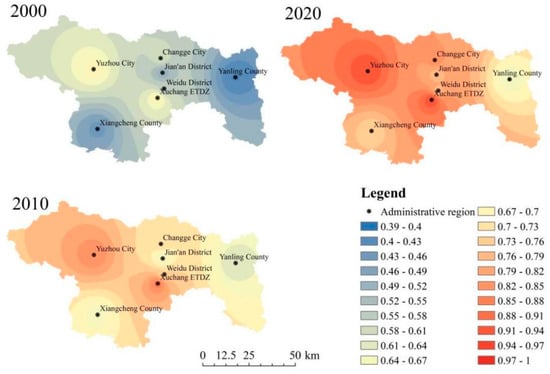

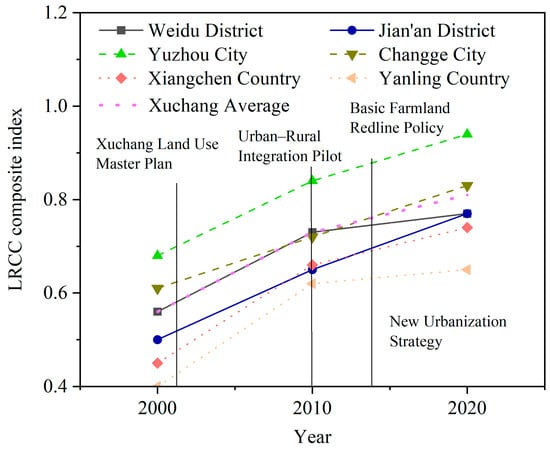

The temporal and spatial evolution of LRCC in Xuchang from 2000 to 2020 exhibited a consistent upward trend, though with pronounced spatial heterogeneity among administrative units (Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Land use and land cover change trends in Xuchang City (2000–2020).

Figure 5.

Spatial distribution of LRCC in 2000, 2010, and 2020 using IDW interpolation.

Table 4 summarized the LRCC values and their changes across all regions during the study period, providing a quantitative basis for the subsequent spatial and policy analyses. On average, the composite LRCC index rose from 0.56 in 2000 to 0.81 in 2020, representing a net gain of +0.25 (+44.6%) over two decades. However, the magnitude and pace of growth varied markedly among administrative regions due to differences in land-use transitions, industrial restructuring, and policy-driven development priorities.

Table 4.

LRCC values and changes across administrative regions in Xuchang City.

The IDW-interpolated maps (Figure 5) clearly illustrated the spatial evolution of LRCC: values were initially concentrated in the urban core areas and gradually expanded toward surrounding counties over time. These spatial shifts aligned closely with the land-use transitions depicted in Figure 4 and Figure 5, highlighting how construction land expansion and industrial development have driven LRCC improvements. This integrated analysis of LUCC and LRCC provided a coherent spatio-temporal overview of Xuchang’s land resource dynamics and established the empirical foundation for the phase-based analysis in Section 4.1.1, Section 4.1.2 and Section 4.1.3.

4.1.1. 2000: Low Baseline and Pronounced Core–Periphery Divide

In 2000, the overall LRCC level was low (Xuchang average = 0.56), displaying a strong “core–periphery” spatial structure. High baseline values were observed in Xuchang ETDZ (0.69), Yuzhou (0.68), and Weidu (0.56). They were supported by early industrialization, concentrated infrastructure, and active construction land expansion. In contrast, Yanling (0.40) and Xiangcheng (0.45) exhibited significantly lower LRCC, reflecting limited industrial diversification, weak service capacity, and high agricultural dependence.

This initial disparity laid the foundation for subsequent differentiated growth patterns, where central urban areas had the structural advantage to respond to development-oriented policies. The spatial analysis (Figure 4 and Figure 5) confirmed these spatial patterns, showing that urban centers exhibited higher LRCC values compared to peripheral areas.

4.1.2. 2000–2010: Rapid Urban-Driven Growth

Between 2000 and 2010, Xuchang entered a phase of accelerated urbanization, with the citywide LRCC rising from 0.56 to 0.73 (+0.17, +44.6%). The high-growth clusters emerged in the urban core and surrounding development zones, where land-use transformations were most significant. The spatial patterns of construction land expansion and the resulting LRCC gains were most pronounced in Xuchang ETDZ, Yuzhou, and Weidu.

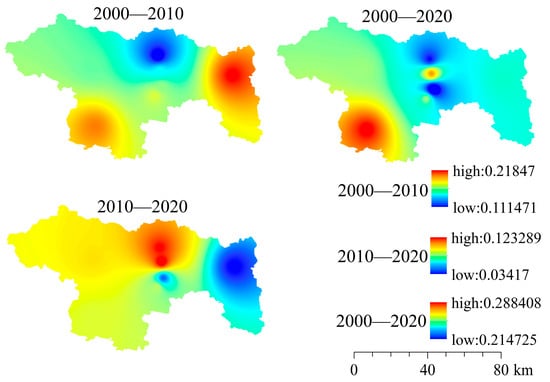

Raster difference mapping (Figure 6) further visualizes these spatio-temporal variations, clearly identifying the major zones of capacity increase between 2000–2010 and 2010–2020. The map highlights strong positive changes concentrated in urban-industrial centers and peri-urban corridors, confirming the dominance of policy-driven, urban-led growth. Fastest growth: Xiangcheng (+0.21), Yanling (+0.22), Xuchang ETDZ (+0.18), and Weidu (+0.17) all exhibited considerable increases in LRCC, driven by industrialization and infrastructure concentration. Moderate growth: Jian’an (+0.15) and Yuzhou (+0.16), largely benefiting from secondary-industry expansion and peri-urban construction. Lagging growth: Changge (+0.11), reflecting its more mature urbanization stage.

Figure 6.

Spatio-temporal variations in LRCC from 2000 to 2020 based on difference mapping.

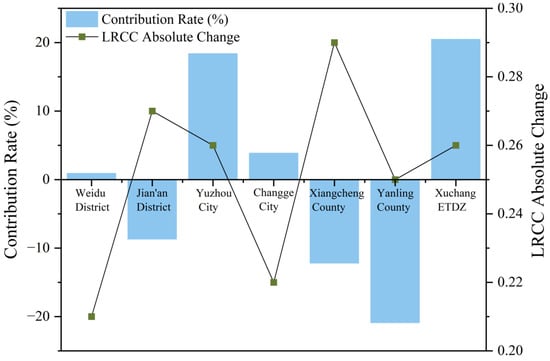

LUCC dynamics confirm that construction land in Weidu, Jian’an, and ETDZ expanded rapidly during this period, boosting LRCC in these zones. However, despite Xiangcheng and Yanling achieving the largest numerical LRCC gains, their overall contributions to citywide capacity were negative (Xiangcheng −12.19%, Yanling −20.89%) due to low initial baselines and limited integration with the urban core (Figure 7). Negative contribution values indicated regions with absolute high-weight indicators, including urbanization rate (C12 ≈ 20.6%) and large-scale industrial output (C9 ≈ 11.4%). The secondary-industry production (C3 ≈ 10.9%) amplified LRCC improvements in urban cores (ETDZ, Yuzhou, Weidu). In contrast, peripheral counties focusing on low-weight agricultural indicators (C5, C6) exhibited lower or even negative contributions, highlighting the policy–LUCC–LRCC coupling mechanism.

Figure 7.

Contribution rates and absolute LRCC changes across administrative units in Xuchang (2000–2020).

4.1.3. 2010–2020: Slowing Growth and Emerging Constraints

From 2010 to 2020, LRCC continued to increase but at a slower pace, rising from 0.73 to 0.81 on average. The spatial pattern shifted notably, with urban pilot regions and industrial hubs becoming the dominant drivers of improvement. Notable gains were observed in Jian’an (+0.12), Yuzhou (+0.10), and Changge (+0.11), with Jian’an showing the largest absolute growth in LRCC during this decade.

Spatially, the overall growth rate of LRCC slowed compared with the previous decade, reflecting the impact of increased ecological constraints and the implementation of stricter farmland protection policies. The spatio-temporal difference maps (Figure 6) clearly highlighted these trends, showing that while central urban areas maintained positive momentum, peripheral counties experienced a marked decline in growth intensity. When combined with the spatial distribution patterns in Figure 5, the results demonstrate a shift from broad urban expansion to more localized, policy-constrained development after 2010. Moderate improvements were recorded in ETDZ (+0.08) and Xiangcheng (+0.08), supported by continued industrial investment and farmland redline controls. Minimal gains occurred in Weidu (+0.04) and Yanling (+0.03), where urban land saturation, ecological zoning, and conversion restrictions limited further capacity expansion. These spatial patterns illustrate a transition toward a mature urban system, where growth was increasingly regulated by ecological and land policy constraints.

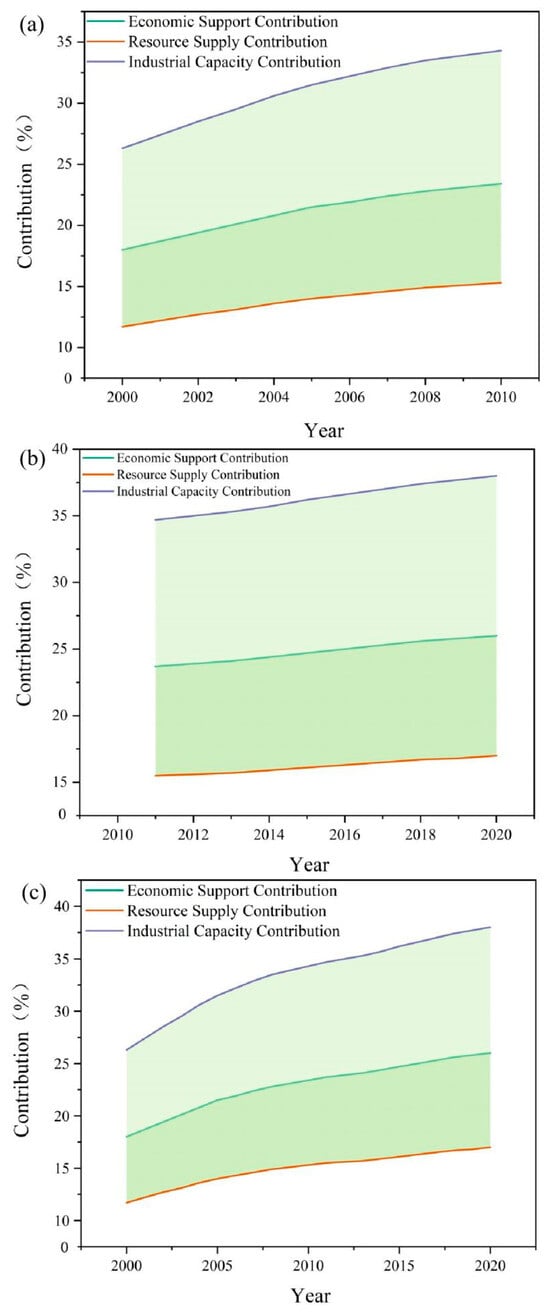

To summarize the spatio-temporal evolution of LRCC across the three periods (2000–2010, 2010–2020, and the overall 2000–2020 interval), Figure 8 presents a stacked-area chart illustrating how each LRCC subsystem, including economic support, resource supply, and industrial capacity contributed to total LRCC growth. The stacked-area chart illustrated the contribution of three subsystems, including economic support, resource supply, and industrial capacity to overall LRCC growth during the three periods: 2000–2010, 2010–2020, and the cumulative period from 2000 to 2020. Each color represented a subsystem, highlighting their changing roles over time. As shown in the figure, during 2000–2010, economic support and industrial capacity were the dominant drivers, while resource supply contributed steadily. Between 2010 and 2020, growth slowed mainly due to ecological constraints and farmland protection, yet industrial capacity and economic support remained important. The figure visually reinforces the changing dynamics and relative importance of each subsystem over time.

Figure 8.

Temporal decomposition of LRCC growth in Xuchang City, (a) from 2000–2010; (b) from 2010–2020; (c) from 2000 to 2020.

4.1.4. Spatio-Temporal Divergence and LUCC-LRCC Coupling

Figure 6 revealed persistent LRCC disparities between urban cores and peripheral counties as follows. The LRCC gap between the highest-value zone (ETDZ = 0.95) and the lowest-value zone (Yanling = 0.65) remained nearly constant in absolute magnitude (0.29 in 2000 vs. 0.30 in 2020), indicating persistent disparities in absolute terms. However, the disparities narrowed. The percentage gap (max − min)/max declined from 42.0% (=0.29/0.69 in 2000) to 31.6% (=0.30/0.95 in 2020), the min-to-max ratio increased from 0.58 (=0.40/0.69) to 0.68 (=0.65/0.95), and the cross-sectional coefficient of variation among the seven units fell from 0.186 to 0.124. Thus, the spatial pattern could be described as persistent in absolute magnitude but narrowing in relative disparity.

Figure 7 directly visualized the mismatch between absolute LRCC gains and entropy-weighted contribution rates across administrative units (bars = contribution rate; line = absolute LRCC change). ETDZ (+20.46%) and Yuzhou (+18.37%) showed the largest positive contributions. Conversely, Jian’an (−8.69%), Xiangcheng (−12.19%), and Yanling (−20.89%) exhibited negative contribution rates. This did not indicate declines in LRCC itself. It reflected relative weighting effects. Although Jian’an’s absolute LRCC increased substantially (+0.27 from 2000 to 2020), its share of the total citywide improvement decreased because faster growth in the core zones (Weidu, Yuzhou, ETDZ) dominated the entropy-weighted index. Within the entropy-weighting framework, indicators showed greater spatial and temporal variability, such as urbanization rate and industrial output, which received higher weights, inherently favoring urban cores. By contrast, districts with low-variability agricultural indicators contributed less, even when experiencing absolute growth. This explained why peripheral counties with improved LRCC values nonetheless yielded negative contribution rates.

The integrated relationships among policy stages, indicator weights, and regional contributions were illustrated in Figure 2. It visually linked policy timelines with indicator-weighting structures and observed contribution disparities. It provided a comprehensive explanation of how differential indicator variability and policy timing shaped spatial heterogeneity in LRCC evolution from 2000 to 2020. It was important to clarify the distinction between absolute growth and relative contribution. Jian’an achieved strong absolute LRCC growth (+0.27); its contribution rate (−8.69%) remained negative, because its dominant indicators, including agricultural output and land development intensity, showed low spatial variability. The entropy-weighting mechanism thus amplified the influence of urbanization-related indicators, enhancing the contributions of core areas.

Comparison with LUCC dynamics indicated a strong coupling between construction land expansion and LRCC improvement. Urban cores characterized by industrial clustering and infrastructure concentration consistently outperformed peripheral agricultural zones, where limited land-use efficiency and ecological constraints restricted capacity enhancement. Overall, Xuchang’s LRCC rose by 44.6% (from 0.56 in 2000 to 0.81 in 2020), but spatial contributions were highly uneven (Table 4). Urban districts such as Weidu and Jian’an, together with Xuchang ETDZ and the industrial hub Yuzhou, accounted for over 40% of total improvement, forming a contiguous high-capacity growth corridor. Peripheral counties (Yanling, Xiangcheng), despite positive LRCC gains, exhibited negative contribution rates, reflecting structural development constraints and limited integration into urban-centered growth dynamics.

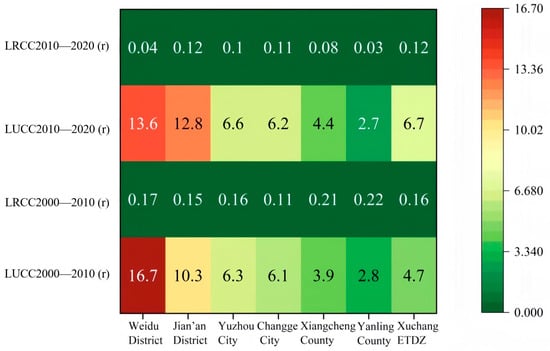

To quantify LUCC–LRCC coupling, we calculated rank correlations between construction land expansion rates and LRCC gains across the seven administrative units for each period. The Spearman coefficients are ρ = 0.41 (p = 0.36) for 2000–2010 and ρ = −0.50 (p = 0.25) for 2010–2020, based on a small sample (n = 7). The first decade thus shows a weak positive association, where districts with faster construction land expansion tended to record somewhat larger LRCC gains, whereas in the second decade LRCC improvements became partially decoupled from further expansion and were more strongly associated with efficiency-oriented and policy-driven adjustments. Although these correlations are not statistically significant at conventional levels, they provide a light-weight, quantitative check that complements the spatial contribution analysis. In Figure 9, each cell represents a period-specific correlation coefficient, with color intensity proportional to its magnitude, visualizing the strength and sign of the association between land-use transformation and LRCC change.

Figure 9.

A correlation heatmap visualizing the relationships between the construction land expansion rates and LRCC gains across the seven administrative units. Each cell represents the correlation coefficient between the respective pairs of variables, with the color intensity indicating the strength of the correlation.

4.2. Policy Impact Analysis

This section examines how major land-use policies shaped LRCC evolution across Xuchang’s administrative regions. Although the study was finalized in 2025, the analysis focuses on the period from 2000 to 2020, representing the most coherent and data-complete phase of land governance policies. Post-2020 initiatives are excluded due to limited monitoring data but will be evaluated in future work. Building on Section 4.1, the analysis integrates administrative LRCC changes, contribution rates, and policy timelines to identify temporally staged and spatially heterogeneous policy effects (Figure 2 and Figure 7). We interpret the policy–LRCC findings as associations derived from temporal alignment and spatial overlays, consistent with our non-causal design described in Section 3.5.

4.2.1. Temporal Alignment Between Policy Implementation and LRCC Shifts

First, Xuchang Land Use Master Plan (2001) presents initiating spatial restructuring (2000–2010). The Master Plan introduced spatial zoning and construction/farmland quotas, coinciding with the most rapid phase of LRCC growth. Between 2000 and 2010, the citywide LRCC increased by +0.17 index units, with substantial gains in Yanling (+0.22), Xiangcheng (+0.21), ETDZ (+0.18), and Weidu (+0.17). Figure 10 showed that these improvements clustered shortly after the Plan’s implementation, reflecting the combined effects of urban expansion guidance, farmland preservation, and infrastructure rollouts.

Figure 10.

Policy timeline vs. LRCC changes.

Second, Urban–Rural Integration Pilot (~2010) presents peri-urban consolidation (2010–2020). It launched around 2010; this program enhanced land-use efficiency and integrated rural areas into peri-urban industrial zones, especially in Yuzhou and Changge. During 2010–2020, LRCC rose by +0.10 in Yuzhou and +0.11 in Changge, while Jian’an District exhibited the largest increase (+0.12). Figure 10 indicated that these inflection points aligned closely with policy rollout, underscoring the effect of targeted land consolidation and infrastructure investment.

Third, Basic Farmland Redline Policy (2014–2016) presents ecological protection and urban conversion constraints. This policy established permanent farmland protection zones, particularly affecting Yanling and Xiangcheng. After 2014, LRCC growth slowed in Yanling (+0.03) and moderately in Xiangcheng (+0.08). Although the policy stabilized agricultural output and ecosystem services, it constrained LRCC improvement in regions relying on construction land expansion. New Urbanization Strategy (2014 onward) presents compact, sustainable growth. Introduced in 2014, this strategy promoted compact, green, and efficient urban development, mainly in Weidu, Jian’an, and ETDZ. Between 2010 and 2020, these areas sustained steady LRCC increases (Jian’an +0.12, ETDZ +0.08, Weidu +0.04), reflecting industrial clustering and enhanced urban service capacity. Figure 10 confirmed that LRCC trajectories in urban cores accelerated following policy implementation.

Table 5 summarizes the objectives, spatial coverage, and potential LRCC impacts of major land-related policies (2000–2020), providing detailed context for the spatial and temporal dynamics discussed above.

Table 5.

Major land-related policies in Xuchang (2000–2020) and their relevance to LRCC.

4.2.2. Divergent Contribution Rates and the Role of Indicator Weights

A key finding is that absolute LRCC gains do not always translate into positive contributions to citywide improvements. Between 2000 and 2020, contribution rates varied considerably (Figure 7). Positive contributors included ETDZ (+20.46%), Yuzhou (+18.37%), Changge (+3.85%), and Weidu (+0.90%). Negative contributors were Jian’an (−8.69%), Xiangcheng (−12.19%), Yanling (−20.89%).

This apparent paradox stemmed from the entropy-weighted composite index structure (Table 2), in which indicators with greater variability across space and time received higher weights. High-weight indicators such as the urbanization rate (C12 ≈ 20.6%), output of large-scale industrial enterprises (C9 ≈ 11.4%), and secondary industry output (C3 ≈ 10.9%) dominated the LRCC composite score.

Urban-industrial hubs like ETDZ and Yuzhou performed strongly on these indicators, yielding disproportionately high positive contributions. In contrast, Yanling and Xiangcheng characterized with notable absolute LRCC gains (+0.25 and +0.29, respectively) showed improvements mainly in low-weight agricultural indicators (e.g., grain yield, agricultural machinery power). As a result, their overall impact on the citywide composite LRCC was limited, and their contribution rates remained negative.

4.2.3. Spatial Heterogeneity in Policy Responsiveness

Integrating temporal dynamics, contribution rates, and policy interventions reveals three distinct patterns of regional responsiveness. First, high-impact urban/industrial responders—ETDZ and Yuzhou—accounted for nearly 39% of total LRCC gains due to strong improvements in high-weight industrial and urbanization indicators. These regions benefited from intensive investment, infrastructure expansion, and industrial agglomeration encouraged by the Land Use Master Plan and New Urbanization Strategy.

Second, peri-urban beneficiaries—Changge and Jian’an—experienced substantial LRCC growth during the Urban–Rural Integration Pilot. Their lower improvements in high-weight indicators resulted in moderate contribution rates. Their development was characterized by transitional land conversion and moderate policy responsiveness.

Third, agricultural constraint zones—Yanling and Xiangcheng—exhibited considerable absolute LRCC increases yet recorded negative contribution rates, constrained by reliance on agricultural productivity and the restrictive effects of the Basic Farmland Redline Policy. The policy’s ecological benefits came at the cost of limiting construction land expansion and industrial diversification. These differentiated responses illustrate that the policy–LRCC coupling was strongly conditioned by both the indicator-weighting framework and the preexisting economic structure of each region.

4.2.4. Synthesis and Future Directions

Taken together, the LRCC, LUCC, and contribution patterns suggested that land-use policies were closely associated with LRCC dynamics in Xuchang from 2000 to 2020, though their effects were spatially uneven and indicator-dependent. Urban districts such as Weidu, Jian’an, Xuchang ETDZ, and Yuzhou formed a contiguous high-capacity growth corridor, while peripheral counties (Yanling, Xiangcheng) lagged behind despite positive LRCC gains. Grouped trend contrasts across urban/industrial cores, peri-urban connectors, and agricultural-constraint zones (Table 6) indicate that core areas with stronger exposure to zoning, industrial upgrading, and infrastructure investment achieved larger LRCC improvements per unit of construction land change than peripheral agricultural zones, consistent with a shift from purely expansion-driven to more efficiency-oriented capacity gains.

Table 6.

Design-based triangulation (grouped LRCC trend contrast): mean decadal change (Δ) by policy-exposure proxy, 2000–2010 (pre-trend) vs. 2010–2020 (policy period).

Policy tools thus exhibited spatially differentiated effects. Farmland protection and ecological zoning policies helped stabilize or enhance agricultural carrying capacity in peripheral counties, but contributed relatively little to the aggregate LRCC index when not combined with urban-industrial upgrades. By contrast, urbanization and industrial restructuring remained the most powerful levers for raising citywide LRCC, especially where targeted investments in infrastructure, industry, and urban services were concentrated in initially low-capacity districts. These patterns underscore the importance of differentiated development strategies: uniform ecological and farmland protection measures need to be complemented by rural industrial parks, logistics infrastructure, and more diversified local economies to avoid unintentionally reinforcing existing spatial disparities.

The 2000–2020 period provided a coherent baseline for understanding policy-driven LRCC dynamics under rapid urban growth and tightening land constraints. Since 2020, multiple new land-use management and ecological restoration initiatives have been introduced in Xuchang and across the region. Future work can extend the present analytical framework to longer monitoring records and richer panel data, allowing the use of more formal spatial and quasi-experimental designs to further disentangle policy impacts from broader structural trends while continuing to track efficiency-without-expansion pathways in LRCC evolution.

4.3. Weighting Robustness and Surface Validation

The spatial ordering of LRCC remains robust across different weighting schemes. Specifically, when comparing entropy-based weighting with equal-weight methods, we observe high consistency in the spatial ranking of regions, with the overlap between the top 3 regions consistently being 100% across both schemes, indicating that the overall spatial order of LRCC is not sensitive to the choice of weighting method.

Supplementary Table S4 provides a detailed comparison of the LRCC values across different regions in Xuchang from 2000 to 2020, illustrating the variation in LRCC scores between entropy-weighted and equal-weighted methods. ETDZ shows an increase from 0.41 in 2000 to 0.55 in 2020 with the entropy weighting, yielding a growth of 33.41%, while the equal-weight method shows a smaller increase from 0.46 to 0.49 (8.57%). This results in a −24.84% difference in growth rates between the two methods. Weidu shows a smaller difference in growth, with a 20.44% increase in entropy-weighted LRCC (0.42 to 0.50) compared to 3.35% with equal weighting (0.48 to 0.50), resulting in a −17.99% difference between the two methods. Jianan displays a modest increase in both weighting schemes, from 0.40 to 0.47 with entropy weighting (15.80%), and from 0.49 to 0.50 with equal weighting (2.26%), showing a −13.14% difference in growth.

These differences are further illustrated across the entire region, with some areas such as Xiangcheng and Yanling showing lower absolute growth in both weighting methods. For instance, Xiangcheng’s entropy-weighted LRCC increased by just 6.10% (0.37 to 0.39), while equal weighting showed a decrease of −3.95% (0.48 to 0.46), resulting in a −10.05% difference. Similarly, Yanling showed minimal growth in both methods, with a 10.17% increase with entropy weighting and a decrease of −0.25% with equal weighting, leading to a −10.42% difference.

The magnitude of citywide LRCC growth differs across schemes: the entropy method yields a +44.6% increase, whereas the equal-weight method produces a much more modest +3.17%. Despite this difference in absolute growth, both weighting schemes preserve a very similar spatial ordering of districts and consistently identify the same high- and low-LRCC areas, indicating that our qualitative conclusions about spatial patterns are robust to the choice of weights.

5. Discussion

5.1. Broader Patterns of Spatial Heterogeneity in LRCC Dynamics

The benchmarking and validation exercises in Section 3.3 and Section 4.3 show that the main spatial ordering of districts is robust across alternative weighting schemes (entropy, equal weight, AHP), and that LOOCV errors for the interpolated LRCC surfaces are small. These checks provide a stable basis for interpreting broader spatial patterns and their policy implications.

The results in Section 4 revealed a clear and structured pattern in the evolution of Xuchang’s LRCC from 2000 to 2020. Citywide LRCC increased by 44.6%, from 0.56 in 2000 to 0.81 in 2020 (Table 4), but this growth was strongly differentiated across space. As shown in Table 4 and the LRCC surfaces and change maps in Figure 5 and Figure 6, urban–industrial centers—including Weidu, Jian’an, the Economic and Technological Development Zone (ETDZ), and Yuzhou—account for more than 40% of the total LRCC increase and form a contiguous high-capacity growth corridor. By contrast, peripheral agricultural counties such as Yanling and Xiangcheng record smaller LRCC gains and even negative contribution rates, despite positive absolute improvements in their local indices. The contribution patterns in Figure 7 further underscore this imbalance, with ETDZ and Yuzhou making disproportionately large positive contributions, while Yanling and Xiangcheng exhibit negative contribution rates. Together, these results confirm a persistent core–periphery gradient in LRCC dynamics.

This divergence reflects a configuration common to rapidly urbanizing regions. LRCC tends to concentrate where industrial upgrading, urban infrastructure, and policy incentives align, while areas subject to strong ecological protection and limited industrial diversification experience slower relative improvement. In our case, the entropy-weighted framework amplifies these contrasts by assigning greater influence to dynamic socio-economic indicators, so that incremental LRCC gains in constrained peripheral counties contribute less to the citywide composite than similar gains in already advantaged urban cores. Under differentiated policy regimes, improvements in core districts therefore weigh more heavily in the aggregate capacity trajectory than those in structurally constrained hinterlands. The subsystem decomposition in Figure 8 is consistent with this interpretation: economic support and industrial capacity dominate LRCC gains in the early period, whereas resource- and constraint-related components become relatively more important after 2010, reflecting a shift from expansion-driven to more regulation- and efficiency-oriented capacity enhancement.

These findings are consistent with previous regional studies of the Pearl River Delta [39] and the Yangtze River Delta [26,40], where urban–industrial hubs such as Guangzhou and Shanghai dominate regional carrying capacity while rural hinterlands lag behind. However, the degree of spatial disparity in Xuchang is more moderate, reflecting its smaller metropolitan scale and less intensive industrial agglomeration. This suggests that mid-sized cities could achieve relatively balanced LRCC growth through policy coordination and land-use optimization, rather than relying on extremely concentrated growth poles.

Preliminary post-2020 observations (beyond the formal study period) also point to the emerging role of ecological restoration and farmland redline policies in improving LRCC through efficiency rather than additional land conversion. Although not analyzed quantitatively here, this is consistent with a gradual shift from expansion-driven to quality- and efficiency-oriented capacity enhancement, a trend increasingly noted in the literature on the Chinese new urbanization phase.

5.2. Policy Mechanisms, LUCC–LRCC Coupling, and Design-Based Triangulation

The joint evolution of LUCC, LRCC, and policy timing (Figure 10) points to three main policy-mediated mechanisms. As shown in Table 4 and the LRCC and LUCC maps in Section 4.2, the early 2000s are characterized by spatial restructuring and industrial clustering (from around 2001 onwards), which diverted activity toward peri-urban corridors and the ETDZ. In this phase, LRCC gains in core and peri-urban districts are achieved largely through reallocation and intensification of existing construction land, rather than through major net expansion. A second mechanism is peri-urban integration and industrial upgrading (from around 2010), reflected in improved connectivity between Yuzhou/Changge and the core, and in rising LRCC in these connector districts despite only moderate changes in construction land intensity. Simple pooled OLS summaries in the Supplement indicate that LUCC quantities alone explain only a limited share of LRCC variation, suggesting that quality-oriented changes in industrial structure and infrastructure play an important role. Third, ecological constraints under the Farmland Redline (2014–2016) stabilized agricultural carrying capacity and tightened construction in peripheral counties such as Yanling and Xiangcheng, which helped moderate outward expansion but also slowed LRCC gains in these heavily constrained areas. This pattern is broadly consistent with evidence that land-protection policies can increase land productivity while containing urban sprawl [41].

To strengthen inference beyond descriptive alignment, while acknowledging the limited number of time points, we complemented visual comparisons with three simple, design-based triangulation checks using group averages and decadal slopes (Table 6 and Supplementary Tables S8 and S9). First, grouped pre-trend and trend contrasts split districts by baseline exposure to farmland redline and ecological constraints. In 2000–2010, exposure groups display broadly similar LRCC slopes, suggesting comparable pre-trends. In 2010–2020, however, the higher-exposure group records larger LRCC gains alongside non-increasing land development intensity (C4), which is consistent with an “efficiency-without-expansion” pattern in more constrained areas. Second, an efficiency-oriented index summarized in Supplementary Table S8 shows a monotonic gradient: districts more strongly exposed to farmland redlines and ecological zoning tend to achieve greater LRCC improvements per unit reduction in construction land intensity. This aligns with studies reporting that ecological restoration and protection can enhance land productivity without necessarily expanding land conversion [42].Third, placebo-year contrasts centered on a pseudo cutoff in 2005 do not exhibit a systematic gradient, whereas contrasts centered on the 2014–2016 redline period do. This supports the interpretation that the observed improvements are aligned with the timing of land-protection policies rather than generic time trends alone.

Table 6 summarizes the decadal changes in LRCC by policy-exposure group, highlighting how these mechanisms play out across space. Urban and industrial cores (ETDZ, Weidu, Jian’an, Yuzhou) show relatively large LRCC gains in both decades; peri-urban Changge exhibits sustained improvements as it becomes better integrated with the core; and agricultural-constraint counties (Xiangcheng, Yanling) experience a sharper slowdown in 2010–2020 as ecological and farmland controls bind more tightly. Taken together with the quantitative LUCC–LRCC correlations reported in Section 4.1.4 and visualized in Figure 9, and with the scenario analysis in Section 5.5—where an illustrative package that raises C12 by 2% and reduces C4 by 10% yields a predicted ΔLRCC ≈ +0.0226\Delta LRCC\approx +0.0226ΔLRCC ≈ +0.0226 (Scenario S3)—these patterns suggest that mid-sized cities can raise LRCC through densification and productivity-oriented levers while tightening land pressure, without relying solely on extreme spatial concentration. Given only three benchmark years and observational data, we consistently characterize all policy–LRCC relationships as associational rather than causal.

5.3. Methodological and Temporal Considerations

By focusing on the 2000–2020 period, this study aligned with a coherent land governance policy cycle and ensured data comparability across three critical phases of reform in Xuchang. The three benchmark years capture the main transitions from expansion-oriented development to more efficiency- and protection-oriented land management, while keeping the indicator system and statistical sources consistent (Section 2 and Section 3). Post-2020 ecological and digital governance initiatives are therefore discussed qualitatively rather than modeled explicitly, as current data do not yet support statistically robust evaluation. This time-bounded design enhances interpretive clarity, but also underscores the need for longitudinal extensions such as spatial panel models or quasi-experimental designs to further disentangle policy impacts from broader structural trends in future research [16].

From a methodological perspective, the entropy-weighted framework adopted here integrates economic, land-use, and resource subsystems and allows LRCC to be mapped as a spatially explicit, time-varying index at the city scale (Section 3.2, Section 3.3, Section 4.1, Section 4.2 and Section 4.3). Compared with earlier static or single-dimensional LRCC assessments [43], this design provides a more nuanced, dynamic picture of how carrying capacity evolves under rapid urbanization and intensive policy intervention. At the same time, the close agreement between LRCC estimates obtained under entropy, equal-weight, and AHP schemes, together with low LOOCV errors for the interpolated LRCC surfaces, serves as a light-weight sensitivity and robustness check that the main spatial and temporal patterns reported in Section 4 are not artefacts of a particular weighting scheme or interpolation choice. Recent reviews emphasize that entropy-weight and multi-scale spatial methods have become relative mature, whereas the explicit incorporation of temporal policy dynamics in LRCC studies remains under-developed [3]. The present work contributes a step in this direction by embedding concrete policy instruments and their timing into an LRCC evaluation framework, while clearly treating all policy–LRCC relationships as associative and leaving room for more formal causal analysis as richer data and longer observation windows become available.

5.4. Policy Implications and Scenario-Based Evaluation

The empirical results point to the need for differentiated, indicator-aware development strategies that are tailored to the specific constraints and opportunities of each administrative region. The contribution analysis in Table 3, together with the spatial patterns in Table 4 and Figure 5 and Figure 6, shows that urban–industrial hubs, transitional zones, and peripheral agricultural counties play distinct roles in shaping citywide LRCC. To explore how these roles can be adjusted in practice, we use a set of simple, scenario-based simulations (Section 5.5) as illustrative “what-if” experiments rather than forecasts, quantifying the potential impact of targeted changes in key policy-related indicators.

1. Urban–Industrial Hubs (Weidu District, Jian’an District, Yuzhou City, and Xuchang ETDZ).

In these high-capacity districts, indicators such as urbanization rate (C12), large-scale industrial output (C9), and secondary-industry production (C3) have the largest marginal leverage on LRCC (Table 3). Scenario S1 (urban densification) shows that a modest increase in urbanization (e.g., +2% in C12) can yield an LRCC gain on the order of 0.01–0.013, while simulated increments in industrial output or secondary industry in Jian’an and Yuzhou produce LRCC changes of similar magnitude. For Xuchang ETDZ, a +5% increase in C9 translates into an LRCC gain of about 0.006 under the same framework. These results suggest that continued investment in infrastructure, innovation clusters, and service capacity in urban–industrial hubs can convert incremental improvements in C12, C9, and C3 into relatively large contributions to the citywide LRCC trajectory. Improvements in public transport and smart-city systems are also consistent with evidence that enhanced accessibility and information flows can increase land-use efficiency in dense urban regions [44].

2. Transitional and Peri-urban Zones (Changge and Xiangcheng).

Transitional areas link urban cores to rural peripheries and exhibit intermediate LRCC levels and growth rates (Table 4). Scenario experiments indicate that strengthening logistics functions and rural–urban linkages can have non-trivial effects: for example, a +5% increase in grain output (C5) in Changge is associated with an LRCC increase of about 0.008, while a rise in social-capacity indicators (e.g., C11) in Xiangcheng produces LRCC gains on the order of 0.01. In addition, developing green corridors along major transport axes in these zones is expected to deliver combined benefits for accessibility and ecological resilience, which is consistent with findings that green corridors enhance land-resource governance and support LRCC under urban–rural integration [45].

3. Peripheral agricultural counties (Yanling County).

Peripheral counties start from lower LRCC levels, face tighter ecological constraints, and have limited scope for extensive urban expansion. For Yanling, scenario-based adjustments emphasize the integration of eco-industrial parks (e.g., agricultural processing, biomass energy) with improved agri-logistics and cold-chain infrastructure. Within the modeling framework, a +5% improvement in logistics-related capacity can increase LRCC by around 0.008, while modest reductions in land development intensity (C4) through conservation-oriented initiatives are associated with LRCC gains of roughly 0.004. These measures are consistent with the literature on eco-industrial parks as a viable strategy for enhancing economic capacity in peripheral regions without undermining ecological functions [9]. In practice, such strategies could allow counties like Yanling to move away from purely extensive expansion and toward quality-oriented LRCC improvements within ecological limits.

4. Citywide governance and prioritization.

At the city scale, effective land-resource governance requires a multi-scale monitoring of both the composite LRCC and its underlying subsystems. The indicator-level leverage values in Table 3 show that C12 (urbanization rate) has the strongest marginal effect on LRCC (approximately ΔLRCC ≈ +0.0206 per 0.10 increase), followed by C9 and C3. Scenario S2 (ecological tightening) further demonstrates that a 10% reduction in land development intensity (C4) can raise LRCC by about 0.0096, while the combined package in Scenario S3 (densification plus ecological tightening) yields an LRCC gain of approximately 0.0226, lifting the citywide index from about 0.81 to 0.833. These scenario outcomes, which are broadly robust across entropy, equal-weight, and AHP schemes (Section 4.3), provide transparent benchmarks for prioritizing policy levers.

In operational terms, a citywide dashboard that tracks changes in key indicators (C3, C4, C9, C12, C11, C5) alongside their implied LRCC responses could support adaptive land governance decisions. Policymakers can use the entropy-weighted scenario framework to compare alternative policy bundles—for example, trading off incremental densification against stricter ecological constraints—and to assess how different combinations of actions in core, transitional, and peripheral districts jointly shape the citywide LRCC trajectory. Given the three-period design and observational nature of the data, these policy implications are framed as associative and exploratory. Nonetheless, they offer a structured, quantitative basis for aligning land-use, industrial, and ecological policies with the goal of improving land-resource carrying capacity in mid-sized cities.

5.5. Operational Scenario Validation and Policy Prioritization

The empirical patterns described above raise a practical question: to what extent can concrete policy adjustments in key indicators translate into measurable LRCC improvements? To explore this, we apply the scenario protocol introduced in Section 3.6, using the entropy weights in Table 2 and the normalization anchors in Table 3. Within this linear aggregation framework, small shifts in min–max normalized indicators Zi (higher = better after direction handling), weighted by their entropy weights Wi, provide an approximate indication of how LRCC would respond to policy-induced changes in specific KPIs. Full recomputation yields values that are numerically indistinguishable from the linear approximation at the level of precision reported here.

We consider three stylized post-2020 packages. Scenario S1 represents urban densification, implemented as a modest increase in urbanization rate (C12) by 2%. Under 2000–2020 anchors, this corresponds to a normalized shift ∆ZC12 of 0.063, which, when multiplied by the entropy weight of C12 (0.206; Table 2), implies an LRCC gain of approximately 0.013. Scenario S2 captures ecological tightening, modeled as a 10% reduction in land development intensity (C4). With the corresponding change in ∆ZC4 of about 0.232 and a weight of 0.042, the implied LRCC gain is roughly 0.010.

Scenario S3 combines these two levers, yielding an overall LRCC increase of about 0.0226, which would raise the citywide composite from 0.81 in 2020 to approximately 0.833. These scenario magnitudes are consistent with the indicator-level leverage values in Table 3 and illustrate how relatively modest KPI shifts in C12 and C4 can cumulatively reshape the LRCC trajectory.

The scenario conclusions are robust to alternative weighting schemes. Under equal weighting (1/12 per indicator), the combined S3 package still generates an LRCC increase of roughly 0.025, and AHP-based weights with acceptable consistency ratios (CR < 0.10) yield similar orders of magnitude (Supplementary Tables). Thus, while absolute values vary slightly across schemes, the ranking of high-impact levers and the basic message—that moderate densification and ecological tightening can jointly improve LRCC—remain stable. This is in line with recent scenario-based studies that use multiscale simulations to assess how different urbanization and protection pathways affect land-use efficiency and carrying capacity in Chinese cities [46].

Because entropy weights and normalization anchors are defined at the city scale, uniform KPI shifts imply similar incremental LRCC changes at district level when applied consistently across all districts. In practice, this means that district-level LRCC targets under a combined package like S3 can be constructed by adding the expected LRCC increment (≈0.023) to each district’s 2020 baseline, with implicit capping as indicators approach their normalized upper bounds (reflecting diminishing returns near saturation). This provides a simple way to translate citywide policy packages into district-level capacity goals, while still recognizing spatial heterogeneity in starting levels (Table 4; Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7).

The indicator-level marginal leverage values in Table 3 further support policy prioritization. Under the entropy scheme, a 0.10 increase in the normalized value of C12 (urbanization rate) is associated with an LRCC gain on the order of 0.0206, followed by C9 (large-scale industrial output, ≈0.0114), C3 (secondary industry, ≈0.0109), and C11 (hospital beds, ≈0.0103), with GDP (C1) and grain output (C5) also exhibiting non-trivial leverage. Once directionality is handled, reverse-coded land-pressure indicators (C4, C7, C8) contribute positively as their pressures are reduced. These rankings are consistent with broader findings that identify a small set of high-leverage economic and land-use indicators as critical for effective land policy in rapidly urbanizing regions [47].

The combined insights from S1–S3 highlight both complementarities and trade-offs. Densification (C12) and ecological tightening (C4) are complementary in the sense that they produce additive LRCC gains under S3, but tighter land supply may need to be accompanied by productivity-enhancing levers (C9, C3) and strengthened social capacity (C11) to avoid unintended bottlenecks. From a governance perspective, a multi-level monitoring dashboard that tracks period-by-period movements in key indicators ΔZi, their implied LRCC responses, and realized LRCC values would enable auditable mid-course corrections and more adaptive policy design. Such monitoring architectures have been shown to be important for iterative policy adjustment and performance-based land governance [48]. Within these limits, the present scenario exercises should be viewed as operational validation and heuristic guidance rather than precise forecasts, illustrating how the LRCC framework can be used to structure and compare alternative policy bundles in mid-sized cities.

6. Conclusions

This study develops a spatially explicit, entropy-weighted framework to assess LRCC under rapid urbanization, using Xuchang (2000–2020) as a representative inland case. By integrating economic, land-use, and resource subsystems with explicitly coded policy instruments and LUCC dynamics, the framework links territorial governance to observable changes in carrying capacity at the city scale in a way that can be transferred to other rapidly developing urban regions.

The results reveal several generalizable spatial–temporal patterns. LRCC gains tend to concentrate in urban–industrial cores, while peripheral agricultural counties show slower relative improvement despite positive absolute gains, reflecting a persistent core–periphery gradient. Over time, LRCC growth shifts from an expansion-dominated phase towards one in which efficiency improvements, ecological constraints, and policy design play a stronger role, as land development intensity and protection measures begin to bind. These trajectories underscore that carrying capacity in urban land systems is co-produced by governance, infrastructure, and industrial structure rather than determined by biophysical conditions alone.

Methodologically and for practice, the study provides a flexible LRCC evaluation and policy analysis toolkit. An entropy-weighted, multi-subsystem indicator system captures spatial heterogeneity and temporal change while remaining compatible with alternative weighting schemes; simple design-based checks offer light-weight support for interpreting LUCC–LRCC coupling and policy associations under data limitations. An operational scenario protocol translates concrete, monitorable indicators (such as urbanization rate and land development intensity) into predicted LRCC changes; in the Xuchang application, a combined densification and ecological-tightening package yields a ΔLRCC of about +0.0226, illustrating how mid-sized cities can enhance LRCC without relying solely on extensive land expansion. Extending this framework to multi-city, multi-decade panels would allow more rigorous causal analysis and deeper integration with broader land-system and urban-sustainability research.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su172310858/s1, Table S1: Overview of data sources and their usage in LRCC assessment; Table S2: Representative Sample of Raw, Normalized and Weighted Indicator Data for LRCC Assessment (Xuchang City, 2000–2020); Figure S3: Visualization of Entropy-Derived Weights for LRCC Evaluation Indicators (2000–2020); Table S4: Comparison of LRCC Values for Xuchang Regions from 2000 to 2020 under Entropy-based and Equal-weighting Methods and AHP; Table S5: Land Use and Land Cover Change in Xuchang City (2000–2020); Table S6: Leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) statistics for IDW interpolation of LRCC (2000, 2010, 2020); Figure S7: Spatial distribution of IDW cross-validation residuals for LRCC estimation in 2000 (S4a), 2010 (S4b), and 2020 (S4c). Residuals were calculated as predicted minus observed values. Among the three years, 2010 shows relatively lower predictive accuracy (R2 = 0.17), resulting in lar; Table S8: Dose–response proxy between baseline exposure to Redline/ecological constraints and LRCC gains (ΔLRCC); Table S9: Grouped trend contrast of LRCC changes (mean Δ per decade) by exposure group (pre- and post-policy periods, 2000–2010 and 2010–2020). References [19,49,50,51] are citied in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions