Abstract

With global warming intensifying, urban public spaces in cold-climate regions are increasingly exposed to heat beyond residents’ adaptive capacity. This study investigates whether smartphone use enhances thermal adaptation in Jingyue Central Park, Northeast China. A seven-day field campaign integrating microclimate monitoring and Passive Activity Observation (PAO) collected synchronized environmental and behavioral data. Results show that smartphone users had higher attendance and longer stays under high temperatures. Their Thermal Neutrality Threshold (NTT) and Critical Thermal Threshold (CTT) increased by about 2 °C and 3 °C, respectively, and up to 4.5 °C during optional activities, suggesting that voluntary media engagement improves heat tolerance and adaptive behavior. The study proposes mediated thermal adaptation to describe how digital media co-regulate environmental perception and adaptation. It extends thermal comfort research to cognitive-behavioral dimensions, links UTCI, NTT/CTT, and PAO data within one framework, and provides practical insights for optimizing thermal environments in cold-climate public spaces. Overall, the findings reveal the growing role of media-mediated behavior in enhancing human resilience to thermal stress.

1. Introduction

With the acceleration of global warming, extreme heat events are occurring with increasing frequency worldwide, exposing urban residents to ever-growing risks of heat exposure [1,2,3,4,5]. As essential venues for daily activities, urban public spaces play a critical role in shaping outdoor behavioral choices and thermal comfort, thereby influencing the health and well-being of city dwellers [6,7]. Notably, the impacts of climate change exhibit substantial regional variation. In cold-climate regions, thermal patterns have undergone significant shifts: while winters may exhibit increased cold extremes, summers are marked by more frequent and intense heat waves [8]. This dual burden of cold and heat presents unique challenges for cities in cold-climate regions, where thermal adaptation strategies must account for both climatic extremes in an integrated manner. Consequently, enhancing the thermal adaptation of urban public spaces has emerged as a central priority in climate-resilient design and sustainable urban development. This issue is particularly pressing in cold-climate regions, where conventional design paradigms often fail to adequately address the escalating threat of summer heat exposure.

In recent years, research on thermal comfort has evolved from a traditional paradigm centered on physical parameters—such as air temperature, humidity, and wind speed [9,10,11,12,13,14]—toward a multidimensional framework that incorporates both psychological cognition and physiological response [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. In outdoor settings, individuals often select adaptive behaviors—such as seeking shade, reducing physical activity, or limiting exposure time—to maintain thermal comfort. Behavioral thermal adaptation has emerged as a key regulatory mechanism in outdoor thermal regulation within urban environments [23,24,25,26]. Meanwhile, smartphones—a pervasive and immersive medium—are increasingly reshaping how people perceive and engage with public spaces, including their thermal surroundings. Recent studies on park use have moved beyond physical indicators such as vegetation, shading, and accessibility toward a broader understanding of how environmental, social, and informational factors jointly shape outdoor behavior. Park visitation is now seen as the outcome of both thermal comfort and digital engagement, influenced by spatial configuration, accessibility, and demographic differences across seasons [27,28,29]. These findings suggest that public parks operate as hybrid systems where environmental exposure and media interaction co-regulate users’ adaptive behavior. Existing studies indicate that smartphone users often experience a dual state of cognitive immersion [30,31,32,33,34,35] and reduced physical mobility [36,37,38,39,40], potentially resulting in prolonged exposure to uncomfortable thermal conditions and altered thermal tolerance. However, the mechanisms through which smartphone use modulates thermal adaptive behavior remain insufficiently explored. This research gap underscores the importance of systematic empirical investigation into the influence of digital media on thermal responses in outdoor urban environments.

Digital media are becoming more integrated into individual thermal adaptation behaviors due to climate warming, especially in summer public spaces in cold-climate cities, where this trend may manifest distinct characteristics. Compared to residents in tropical or subtropical climates, individuals in cold-climate regions tend to be less sensitive to high temperatures and have a lower awareness of heat risks [41]. As a result, they are more likely to rely on quick and adaptive behavioral adjustments when exposed to abnormal heat conditions. In this study, smartphone use may not only influence individuals’ environmental perception and enhance their thermal tolerance but also subtly influence their thermal regulation processes [42], creating a novel “media-driven” thermal regulation mechanism. Therefore, investigating how smartphone use contributes to thermal adaptation strategies in cold environments may enhance our understanding of behavioral thermal adaptation and provide new insights for addressing regional climatic variability.

To ensure both theoretical foundation and practical relevance in thermal environment assessment, this study selected the Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI) as the primary metric after comparing several widely used thermal comfort evaluation methods. Compared to indices such as PET (Physiologically Equivalent Temperature) and SET (Standard Effective Temperature), UTCI incorporates key climatic variables—including air temperature, wind speed, humidity, and solar radiation—alongside human physiological thermal regulatory mechanisms. It has been widely applied across various climatic contexts and has become one of the leading tools in urban microclimate research [43,44]. Moreover, its suitability for mid- to high-latitude regions has been confirmed, making it particularly suitable for cold-region cities like the research site in Northeast China [45]. To capture behavioral adaptation dynamics, this study introduces two additional indicators: the Neutral Temperature Threshold (NTT), representing the temperature at which individuals perceive thermal neutrality, and the Critical Temperature Threshold (CTT), indicating the temperature at which individuals voluntarily terminate outdoor activities. By linking UTCI with NTT and CTT, this approach ensures objective environmental assessment while incorporating dynamic behavioral adaptation, providing a more integrated and comprehensive understanding of thermal adaptation behavior [46,47].

To support this multi-dimensional framework, Passive Activity Observation (PAO) is employed as a replacement for the traditional Thermal Sensation Vote (TSV). PAO overcomes the limitations of TSV in outdoor settings, including sampling difficulties, delayed responses, and lack of synchronization with actual behavior. As a non-intrusive and continuous method, PAO enables the systematic collection of thermal adaptive behaviors—such as activity intensity, stay duration, and shade-seeking preference—across varying thermal conditions. These data not only aid in deriving NTT and CTT but also facilitate alignment with UTCI in time and space, enhancing the overall accuracy and explanatory power of the analysis [43,46,47]. Importantly, PAO also enables real-time recording of naturalistic behaviors such as smartphone use, ensuring continuous behavioral observation and relevance. This capability is essential for identifying the real impact of digital engagement on individuals’ thermal experiences and adaptive responses. Ultimately, this research offers fresh insights into media-mediated thermal adaptation and advances the theoretical framework of heat adaptation research in the digital age.

Based on the proposed framework, this study presents a series of scientific hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1):

Smartphone use enhances individuals’ thermal tolerance in summer public spaces within cold-region cities. If H1 is supported, the study will proceed to test.

Hypothesis 2 (H2):

Smartphone use significantly alters individuals’ thermal neutrality threshold (NTT) and critical temperature threshold (CTT). If H1 is not supported, the study will explore.

Hypothesis 3 (H3):

Different patterns of smartphone use may have varying effects on thermal tolerance, including increasing, decreasing, or having no effect. This hypothesis structure enables a flexible yet rigorous inquiry into the potential impact of digital media on shaping behavioral thermal adaptation.

Based on this framework, an urban park in Changchun—a representative city in a cold-climate region of Northeast China—was selected as the research site. Microclimate monitoring, combined with Passive Activity Observation (PAO), was used to systematically compare the thermal responses of smartphone users and non-users under varying heat exposure levels. Specifically, the research examined differences in behavioral patterns, including attendance and stay duration, under varying thermal conditions. Using observed data, the Neutral Temperature Threshold (NTT) and Critical Temperature Threshold (CTT) were derived for both groups to assess whether smartphone use enhances thermal tolerance. This integrated approach assesses the regulatory effect of smartphone use on thermal adaptation under warming conditions.

Theoretically, this study proposes the concept of smartphone-mediated thermal adaptation behavior as an exploratory extension, advancing the understanding of how media-mediated behaviors influence thermal comfort. Methodologically, the study establishes a triple coupling framework integrating observation, survey, and monitoring, which enables the dynamic identification of behavior–climate interactions. Practically, in the context of global warming, the findings provide targeted design recommendations and adaptive strategies to improve thermal comfort and spatial resilience in urban public spaces of cold-climate regions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Location

Thermal adaptation behavior is shaped by multiple factors, including activity type, individual characteristics, and spatial microclimate. This study selected Jingyue Central Park in Changchun City (43.82° N, 125.42° E) (Figure 1), a major city in Northeast China, as the field research object to provide a representative population and environmental sample basis. As a typical urban park in a cold-climate region, it integrates ecological, cultural, and recreational functions, serving as a high-frequency public activity space, especially during summer.

Figure 1.

Actual view of the current situation of the site.

The site was chosen based on four core criteria to ensure scientific rigor and operational feasibility:

- (1)

- Functional Diversity: The park contains a variety of spatial types—fitness trails, children’s playgrounds, shaded woodland zones, and waterfront areas—capturing a broad spectrum of activity scenarios and enabling comparative analysis of thermal adaptation across behavioral contexts.

- (2)

- Environmental Stability: The site is equipped with benches, pavilions, and tree-lined paths, offering consistent opportunities for shaded rest and supporting sustained observation of heat-adaptive behaviors.

- (3)

- Demographic Diversity: The user base spans multiple age groups, including the elderly, youth, and families with children, facilitating age-stratified analysis of thermal response behavior.

- (4)

- Varied Shading Conditions: The park features diverse shading types—natural (trees), architectural (entrance canopies), and artificial semi-open structures (pavilions)—enabling the assessment of behavioral adaptation under different microclimate conditions.

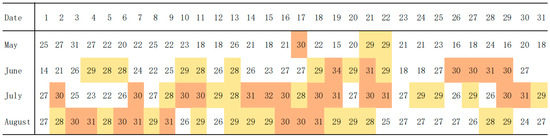

According to the Köppen–Geiger climate classification system [48], Changchun has a temperate continental climate (Dwa), characterized by large annual temperature fluctuations, distinct seasonal transitions, hot and humid summers, and cold, dry winters. Based on the “GB/T 6529-2005 Ergonomics Environmental Standards” [49], high-temperature levels are categorized as follows: “Summer Heat” (28.0–29.9 °C, Level III) and “Cool Heat” (30.0–34.9 °C, Level IV). Meteorological records from May to August 2024 (Figure 2) show that the city experienced 28 days with temperatures between 25.0 and 27.9 °C (classified as “hot”) and 31 days with temperatures between 28.0 and 34.9 °C (“cool heat”), with peak temperatures occasionally reaching nearly 35 °C. This continuous variation in thermal conditions provides a robust basis for analyzing behavioral responses to different levels of heat exposure in public spaces.

Figure 2.

Daily maximum temperature in Changchun from May to August 2024. Source: Meteorological database for thermal environment analysis of Chinese buildings (https://www.tianqi24.com/changchun/history.html (accessed on 20 September 2025)).

2.2. Survey Time and Data Collection Process

To ensure both sample typicality and behavioral authenticity, the fieldwork was conducted over nine non-consecutive weekdays between May and June 2025. Weekends and public holidays were deliberately avoided to prevent sampling bias due to atypically high visitor volumes. Preliminary observations indicated that morning visitation patterns exhibited a stronger correlation with temperature variations compared to those in the afternoon. Accordingly, the daily observation window was set from 9:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m. —a period characterized by intense solar radiation, steadily rising temperatures, and relatively stable pedestrian flows [50,51,52]. This time frame facilitated the alignment of changes with observable behavioral responses. In total, valid data were collected on seven observation days, covering a Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI) range of 7.3–37.13 °C, thereby capturing a broad spectrum of thermal conditions for analysis.

A combination of timed interval recording and continuous video sampling was employed to collect observational data. Attendance, thermal environment parameters, and behavioral characteristics of park users were recorded at five-minute intervals. The number of people attending and the length of stay were captured by fixed-point cameras, allowing for precise synchronization of behavioral and environmental data across both spatial and temporal dimensions. Throughout the survey, the research team strictly adhered to a non-intrusive observational protocol and obtained formal approval from the park administration, ensuring compliance with ethical standards and the integrity of the data collected.

To ensure precise synchronization between behavioral and environmental data, calibrated timers were used to simultaneously trigger behavioral recording (via video and manual counting) and microclimate measurements at the start of each 5 min interval. Before every observation session, all recording devices—including microclimate instruments and cameras—were time-synchronized and recalibrated to a unified clock. During data processing, the timestamps of video recordings were strictly matched with those of the microclimate dataset, ensuring that each behavioral observation corresponded to its concurrent environmental parameters. The temporal deviation between datasets was controlled within a few seconds, guaranteeing high temporal accuracy for integrated analysis.

2.3. Microclimate Monitoring and Instrumentation

Portable multi-parameter microclimate stations were employed to continuously monitor four key thermal comfort parameters: air temperature (Ta), relative humidity (RH), wind speed (Va), and black globe temperature (GT). The sensors were installed at a height of 1.1 m above ground level, following the standard measurement protocol for human thermal sensation as defined by ASHRAE Standard 55 [53] and ISO 7726 [54].

Mean radiant temperature (Tmrt) was calculated using the following Equation (1):

where D denotes the diameter of the black globe (0.05 m in this study) and represents the emissivity of the globe surface (0.95). This formulation incorporates both radiative and convective heat transfer components, thereby providing a robust foundation for calculating the Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI). Details regarding the instrument model, measurement range, precision, and resolution are provided in Table 1, ensuring the scientific validity and cross-comparability of the collected microclimate data.

Table 1.

Specifications of microclimate monitoring instruments.

2.4. Behavior Classification and Attendance Recording

This study employed the Passive Activity Observation (PAO) method [43,45,46] to systematically document on-site human activities, thereby avoiding the limitations of traditional subjective thermal sensation voting (TSV) approaches, which often suffer from small sample sizes and delayed responses in outdoor environments. A zoned counting approach was used to record the number of individuals within the study area while controlling for relevant variables. Based on activity type and age characteristics, the observed samples were classified into ten groups to facilitate comparison under controlled conditions.

When controlling for age, the middle-aged and elderly participants were divided into four subgroups: (1) smartphone users engaged in social activities, (2) smartphone users engaged in optional activities, (3) non-users engaged in social activities, and (4) non-users engaged in optional activities. When controlling for activity type, participants involved in optional activities were further categorized by age and smartphone use, including (5) smartphone-using youth, (6) non-using youth, (7) smartphone-using middle-aged adults, (8) non-using middle-aged adults, (9) smartphone-using elderly adults, and (10) non-using elderly adults. This classification allowed for a structured comparison of behavioral and thermal responses related to smartphone use across different demographic and activity contexts.

In this context, social activities refer to interactive behaviors involving two or more individuals—such as conversing or childcare—while optional activities denote solitary behaviors, including lounging, exercising, or sitting and reading. To enhance classification accuracy, if an individual changed activity types during an observation interval (e.g., transitioning from an optional to a social activity), the behavior was segmented and recorded based on the dominant activity within each time frame. All observational data were supported by video recordings and subsequently annotated to ensure temporal precision and accurate behavioral labeling [54].

In the age-group analysis, the “child” category was excluded due to the absence of valid smartphone use data, which would otherwise result in empty groups and unstable model estimation. Retaining this category could introduce estimation bias or categorical noise in the interaction terms. Removing the child group therefore ensured the model better reflected the actual data distribution. Based on differences in social and life stages, the remaining participants were classified into three age groups: youth (18–35 years), middle-aged (36–60 years), and elderly (above 60 years) [55].

2.5. Stay Duration Measurement and Smartphone Use Identification

Stay duration was measured in minutes, determined through a combination of real-time observation and video-based retrospective analysis. The time span was recorded from the moment an individual entered the observation zone until they exited. To ensure consistency in classification and enhance the comparability of results, this study adopted the “5 min rule” [56,57] for identifying smartphone use. Specifically, individuals who used a smartphone continuously for more than five minutes without engaging in meaningful social interaction were classified as smartphone users. In contrast, individuals who used smartphones intermittently in short, fragmented intervals—despite exceeding a cumulative five minutes—were not categorized as smartphone users due to the lack of behavioral immersion.

To verify the validity and robustness of the “≥5 min” criterion as the effective threshold for immersive smartphone use, a sensitivity analysis was conducted. The threshold was adjusted to 3, 7, and 10 min, respectively, while keeping other variables and model specifications constant. Regression analyses were then re-estimated to evaluate the sensitivity of the findings to the threshold definition. All models controlled for activity type, age group, shading condition, sitting posture, and the presence of accompanying children.

Additionally, to quantitatively assess the impact of thermal conditions on behavior, the maximum UTCI value experienced by each individual during their stay was recorded. This value was defined as the individual’s thermal exposure limit and was subsequently linked to their total stay duration. This approach enabled the identification of boundary conditions between behavioral thresholds and environmental thermal stress.

2.6. Thermal Comfort Indicator System and Analysis Methods

In this study, the Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI) was selected as the primary indicator for assessing thermal comfort. UTCI is an internationally recognized dynamic evaluation tool that quantifies thermal exposure by integrating the human body’s thermal balance and regulatory mechanisms. It incorporates key meteorological factors, including air temperature, humidity, wind speed, and solar radiation [50,51,52,58]. UTCI calculation uses relevant calculator simulation results and combines them with field data for correction [59] to enhance the practical applicability and accuracy of the index.

To more precisely capture individual behavioral responses to thermal environments, this study introduces two key indicators that delineate the boundaries of thermal adaptation, based on the observed variations in attendance with changes in UTCI [45,46]. The “Neutral Thermal Threshold (NTT)” refers to the UTCI value at which attendance begins to decline after reaching its peak, representing the upper limit of thermal comfort as perceived by the public. In contrast, the “Critical Thermal Threshold (CTT)” denotes the UTCI value corresponding to the lowest attendance, indicating the behavioral endurance limit under thermal stress. Together, NTT and CTT effectively reflect the adaptive range of individuals under varying thermal exposures, offering valuable empirical insight into the thermal behavioral responses of residents in cold-climate regions.

2.7. Segmented Regression Modeling Analysis

Given the nonlinear relationship between attendance and the thermal environment, particularly at inflection points within specific temperature ranges, this study employs the Segmented Regression model for analysis. This model can automatically identify critical points between behavioral variables (e.g., number of people, stay duration) and thermal environment variables (e.g., UTCI) and fit linear trends for the phases before and after these inflection points. This approach provides a more precise representation of the segmented influence of the thermal environment on crowd behavior [60,61]. In addition, to examine the interaction effects of smartphone use and activity type on stay duration, as well as the interaction between smartphone use and population composition, two multiple linear regression models incorporating interaction terms were constructed.

Data were processed using Excel and Prism to ensure the diversity of model calculations and the effective visualization of data. During the data cleaning process, outliers were excluded using the “3σ rule” [62], with data points beyond the mean ±3 standard deviations identified and removed to enhance the stability and reliability of the regression model. Finally, the R2 value and the significance of the breakpoints (p < 0.05) were used as evaluation criteria to assess the model’s fit and analytical reliability.

3. Results

This study analyzed seven days of field observation data from Jingyue Central Park in Changchun to quantify human behavioral responses under varying thermal conditions. The primary aim was to compare the thermal adaptation characteristics—such as attendance, duration of stay, and thermal thresholds (NTT and CTT)—between smartphone users and non-users. The findings are presented from multiple dimensions: background, population structure, behavioral responses, and threshold differentiation.

3.1. Conditions and Population Composition

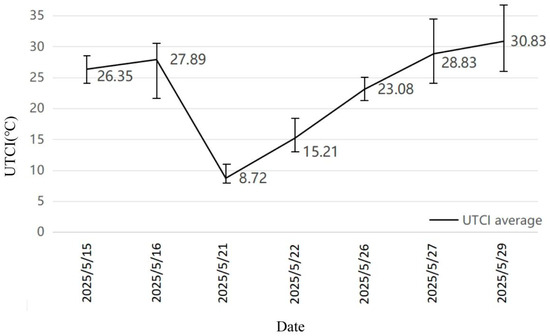

During the study period, thermal conditions fluctuated significantly, with UTCI values ranging from 7.3 °C to 37.13 °C and daily thermal amplitude between 4 °C and 11 °C (Figure 3), reflecting the instability and variability of summer microclimates in high-latitude cities. This variability provided a robust natural setting for investigating thermal adaptive behavior.

Figure 3.

Microclimate measurement data.

The total sample covered four population groups (Table 2): elderly individuals constituted the largest proportion (36%), followed by children (28%), middle-aged adults (24%), and youth (12%). Although youth made up a smaller proportion, they were the dominant group in smartphone usage.

Table 2.

The proportion of different groups.

In terms of activity type (Table 3), the proportions of social and optional activities were nearly equal—53% and 47%, respectively. Within social activities, childcare accounted for 39%, while optional activities were dominated by fitness (26%) and resting (21%). This diversity in behavior and user characteristics provided a solid foundation for comparing the thermal adaptation effects of smartphone use.

Table 3.

Activity type proportion.

3.2. Effective Time Sensitivity Analysis

The sensitivity analysis (Table 4), confirms the robustness of our findings. The direction and magnitude of the estimated effects remained stable across various thresholds defining smartphone usage. The positive impact of smartphone use on stay duration was most pronounced when applying the 5 min threshold (F = 11.572, p < 0.001), suggesting that sustained engagement is a key factor. Moreover, the effect remained positive and statistically significant at alternative thresholds of 3, 7, and 10 min (3 min: F = 10.206, p < 0.001; 7 min: F = 7.554, p < 0.001; 10 min: F = 6.997, p = 0.001), indicating that the results are not highly sensitive to the specific criterion for usage duration. The attenuated statistical significance at the 10 min threshold is likely attributable to the reduced sample size and a corresponding loss of statistical power. Collectively, these analyses validate the ≥5 min criterion as a reasonable and robust operational definition for immersive smartphone use and provide strong empirical support for the conclusion that this engagement significantly modulates outdoor stay behavior, thereby reinforcing the reliability of the study’s primary findings.

Table 4.

Sensitivity comparison of mobile phone usage time of “3”, “5”, “7” and “10 min”.

3.3. Attendance and UTCI Relationship

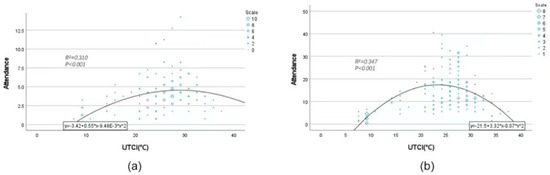

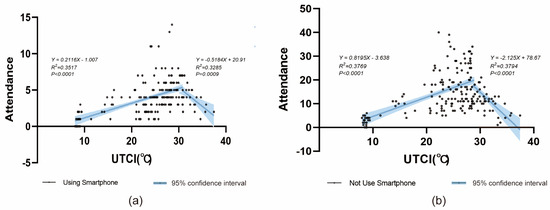

As shown in Figure 4, the number of people in the park exhibited an inverted U-shaped trend with increasing UTCI—peaking at moderate temperatures and declining at both low and high extremes. Notably, distinct differences were observed between smartphone users and non-users. Smartphone users showed rapid growth in attendance below 20 °C and maintained high attendance levels even near 30 °C, indicating stronger heat tolerance. In contrast, non-users’ attendance growth slowed after 18 °C and dropped sharply after 28 °C, suggesting a lower thermal adaptation threshold.

Figure 4.

The relationship between Attendance and UTCI; (a) Using smartphones, (b) Not using smartphones.

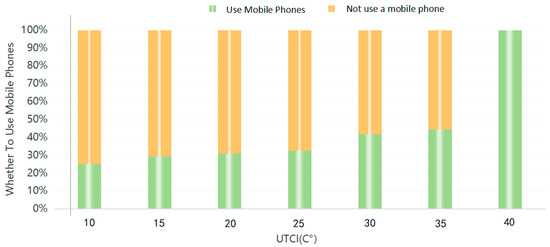

Further analysis of the proportion of smartphone users across varying UTCI levels (Figure 5) revealed that as temperature increased, the share of smartphone users within the total population rose continuously. Model predictions indicate that when UTCI approaches 40 °C, the proportion of smartphone users is expected to reach nearly 100%. This suggests that under extreme heat, only smartphone users remained in the space, reinforcing their higher behavioral resilience in thermally stressful conditions.

Figure 5.

The relationship between whether to use mobile phone proportion and UTCI. (Mobile phone usage rate reaches 100% at 37 °C, and 100% at 40 °C is a predicted value).

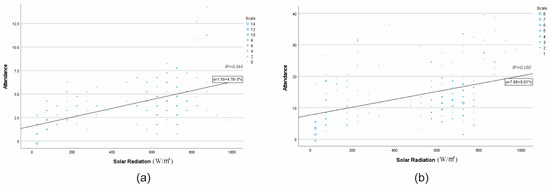

Figure 6 highlights the relationship between solar radiation and attendance. Among smartphone users, attendance was strongly correlated with radiation intensity (high R2), indicating sensitivity and persistence under high solar exposure. In contrast, attendance among non-users showed no clear pattern and low model fit, suggesting that their behavior was more influenced by other environmental or personal factors.

Figure 6.

The relationship between attendance and solar radiation (a) Using a mobile phone, (b) Not using a mobile phone.

These findings suggest a “media buffering effect,” in which immersion from smartphone use may reduce sensitivity to solar discomfort and delay behavioral withdrawal from thermally stressful environments.

3.4. Analysis of NTT and CTT

Through the application of a segmented regression model to identify the inflection point in the relationship between the Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI) and public attendance, the Neutral Thermal Threshold (NTT) was established for two distinct cohorts. A Critical Tipping Threshold (CTT) was subsequently predicted using regression analysis. For mobile phone users, the NTT was determined to be approximately 30 °C (95% CI: 29.24–30.62 °C), with a predicted CTT of 43.0 °C (95% CI: 37.36–50.42 °C). In contrast, non-users exhibited an NTT of approximately 28 °C (95% CI: 27.31–28.27 °C) and a CTT of 37 °C (95% CI: 35.27–40.33 °C) (Figure 7). These results (Figure 8) reveal a significant disparity between the groups, with the NTT and CTT of mobile phone users being approximately 2 °C and 6 °C higher, respectively, than those of non-users. This suggests that individuals engaged with mobile devices tend to sustain their presence in environments with higher thermal loads, indicating a greater cognitive tolerance for thermal discomfort and a higher temperature threshold for behavioral withdrawal. This observed divergence implies that media engagement may delay an individual’s perceptual and behavioral responses to heat, a hypothesis that requires further investigation to confirm its generalizability.

Figure 7.

Number of attendances and segmented return of UTCI (a) People using smartphones, (b) People not using smartphones.

Figure 8.

Comparison of NTT and predicted CTT for smartphones (Attendances) (a) People using smartphones (The blue dotted line is the prediction model), (b) People not using smartphones.

Smartphone users exhibited significantly higher thermal thresholds. Their NTT increased by 2 °C and CTT by 3 °C compared to non-users. This indicates a higher tolerance not only at the perceptual level (comfort zone) but also at the behavioral limit (retreat threshold).

These differences are practically meaningful. For instance, in 2024, over 60% of summer days in Changchun fell within the 28–30 °C range, meaning smartphone users could sustain outdoor activity on more hot days, thus improving public space usage under heat stress.

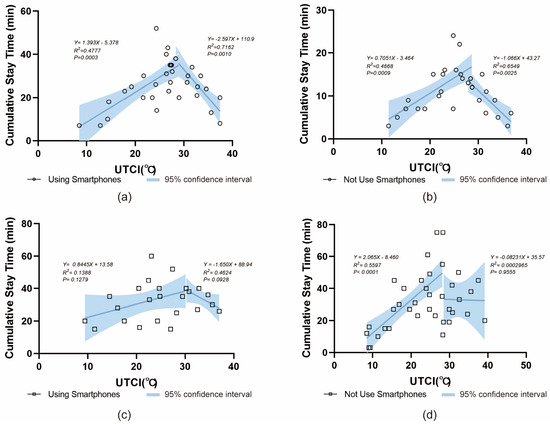

3.5. Stay Duration and Thermal Conditions

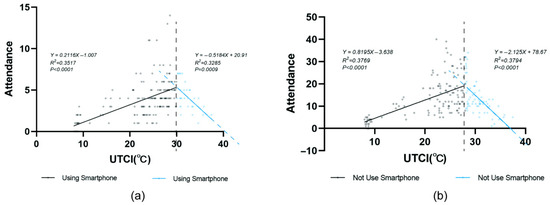

Figure 9a,b show that stay duration followed an inverted U-shaped pattern with respect to UTCI, similar to attendance. Social activities generally had longer durations but were less sensitive to temperature. Optional activities, however, were more strongly influenced by thermal conditions.

Figure 9.

The relationship between cumulative stay time and UTCI (a) using a mobile phone, (b) not using a mobile phone, (c) social activities, (d) optional activities.

In social activities (Figure 9a,c), both smartphone users and non-users had average stay durations of around 30 min. However, beyond 30 °C, smartphone users maintained durations of approximately 33 min, while non-users dropped to 30 min. This suggests higher heat tolerance among users, with less behavioral reduction under elevated temperatures.

In optional activities (Figure 9b,d), smartphone use had a greater impact. Users stayed around 25 min on average, while non-users stayed only 10 min. Smartphone users thus remained over 15 min longer than non-users, indicating that voluntary, self-directed activities are more susceptible to media-enhanced thermal adaptation.

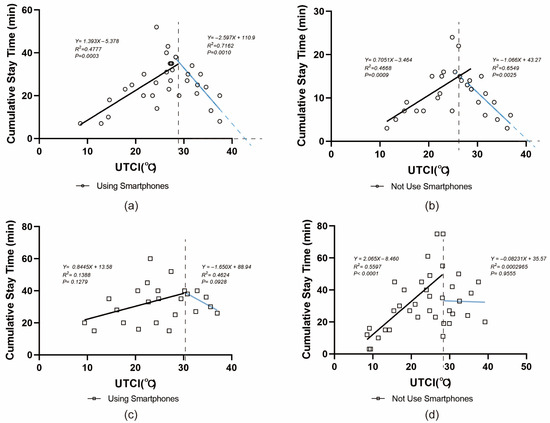

3.6. Differences in NTT for Different Combinations of Behaviors

Figure 8 demonstrates that cell phone use contributes to higher heat tolerance compared to non-cell phone users, with the NTT of cell phone users being approximately 2 °C higher. Although this difference is significant, it is not large enough to warrant conclusive results. Therefore, by modeling the relationship between stay duration and UTCI while controlling for specific age groups and shading conditions, we further investigate the relationship between dwell time and UTCI to examine which types of activities are more strongly associated with cell phone use and which are not.

To examine the interaction effects between smartphone use and activity type, the sample was further divided into four groups, and the corresponding NTT values were calculated. The results indicate that in the context of optional activities, smartphone users exhibited an NTT of approximately 29.5 °C (95% CI: 28.41–29.53 °C), whereas non-users had an NTT of about 25 °C (95% CI: 24.3–27.42 °C) (Figure 10), representing a difference of roughly 4.5 °C (Figure 11). Social activities (Figure 10c, d) showed no significant correlation, with confidence intervals approaching infinity. In contrast, within the context of social activities, the NTT difference between the two groups was less than 1 °C and not statistically significant. Overall, the elevation of the neutral thermal threshold associated with smartphone use primarily occurs during non-interactive, individually driven activities. This pattern may arise because individuals in such activities are more directly exposed to external thermal conditions, and sustained smartphone engagement can redirect attention and cognitive focus, thereby reducing the subjective perception of heat discomfort, prolonging stay duration, and correspondingly raising thermal tolerance thresholds.

Figure 10.

Segmented regression of cumulative stay time and UTCI (Activity Type); (a) Using smartphones + optional activities, (b) Using smartphones + optional activities, (c) Not use smartphones + social activities, (d) Not use smartphones + social activities.

Figure 11.

Comparison of NTT and predicted CTT for smartphones (cumulative stay time) (Activity Type (The blue dotted line is the prediction model) (a) Using smartphones + optional activities, (b) Using smartphones + optional activities, (c) Not use smartphones + social activities, (d) Not use smartphones + social activities.

To further quantify the interaction between smartphone use and activity type, a multiple linear regression analysis was conducted (Table 5). The overall model was statistically significant (F = 9.379, p = 0.003) and explained 30.9% of the variance in stay duration (R2 = 0.309). After controlling for main effects, the interaction term “smartphone use × activity type” remained highly significant (B = 14.266, p = 0.003), providing strong statistical evidence that the influence of smartphone use on stay duration varies across different activity types. Specifically, when the activity context shifted from social to optional activities, the positive effect of smartphone use on stay duration was significantly amplified.

Table 5.

Analysis of the interaction term of “activity type * use smartphone”.

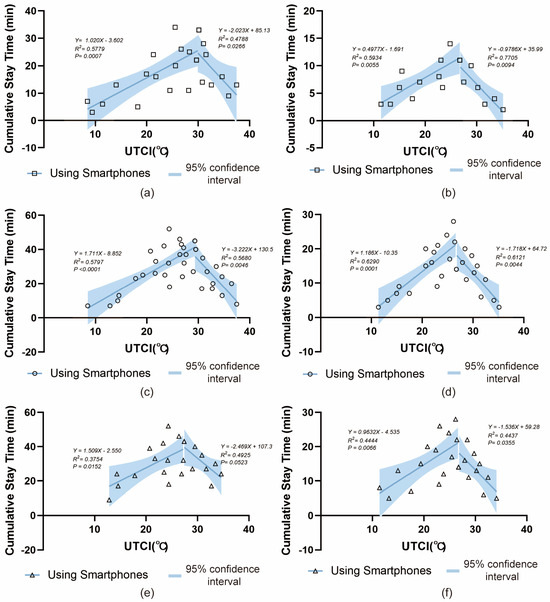

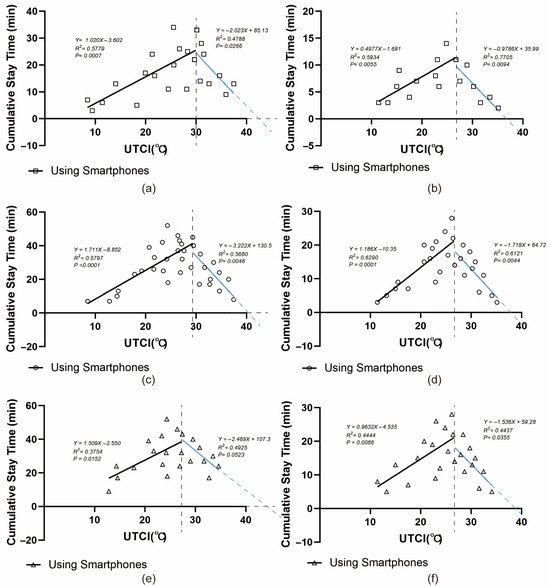

3.7. Age Group Analysis

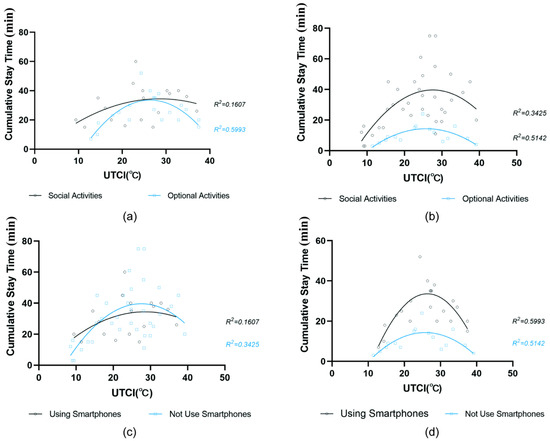

In the preceding analysis (Figure 11), after controlling for solar exposure and other environmental variables, it was found that the increase in the Neutral Thermal Threshold (NTT) associated with smartphone use was concentrated primarily in the context of optional activities, with a difference of approximately 4.5 °C between users and non-users, whereas the difference in social activities was less than 1 °C. This indicates that the elevation of thermal thresholds due to smartphone use mainly occurs in non-interactive, individually oriented activities, potentially linked to mechanisms of attentional distraction and cognitive shift.

To further explore how this mediated effect varies across age groups, an age-stratified analysis was conducted while controlling for activity type and shading conditions (Figure 12). The sample was divided into three groups: young adults (18–35 years), middle-aged adults (36–60 years), and older adults (>60 years). The NTT values of smartphone users and non-users were then calculated for each group (Figure 13). The results revealed that the enhancement of heat tolerance induced by smartphone use was most pronounced among young adults. Specifically, in the young group, smartphone users had an NTT of approximately 29.8 °C (95% CI: 27.05–31.24 °C), while non-users had an NTT of about 27.0 °C (95% CI: 22.57–27.52 °C), indicating a difference of 2.8 °C. Among middle-aged adults, the corresponding NTTs were 29.0 °C (95% CI: 25.80–30.33 °C) and 27.0 °C (95% CI: 26.80–27.65 °C), a difference of 2.0 °C. In the older group, smartphone users showed an NTT of 27.5 °C (95% CI: 25.02–29.46 °C) compared to 26.3 °C (95% CI: 24.27–26.85 °C) for non-users, a modest difference of 1.2 °C. Overall, the heat tolerance enhancement associated with smartphone use exhibited a clear age gradient, progressively weakening with age (young > middle-aged > older).

Figure 12.

Segmented regression of cumulative stay time and UTCI (age); (a) Using smartphones + young people, (b) Not use smartphone + young people, (c) Using smartphones + middle-aged people, (d) Not use smartphones + middle-aged people, (e) Using smartphones + elderly people, (f) Not use smartphones + elderly people.

Figure 13.

Comparison of NTT and predicted CTT for smartphones (cumulative stay time) (age) (The blue dotted line is the prediction model) (a) Using smartphones + young people, (b) Not use smartphone + young people, (c) Using smartphones + middle-aged people, (d) Not use smartphones + middle-aged people, (e) Using smartphones + elderly people, (f) Not use smartphones + elderly people.

This gradient aligns closely with the digital media engagement characteristics of different age cohorts. Younger individuals typically demonstrate higher smartphone use frequency and stronger immersion, making them more susceptible to the “cognitive distraction effect,” in which attention becomes absorbed by digital content, thereby reducing the perception of external heat discomfort. Consequently, they are able to remain active and prolong their stay even under higher temperature conditions. In contrast, older adults tend to rely less on smartphones and experience lower levels of media immersion, leaving their thermal regulation processes primarily driven by direct environmental stimuli, which weakens the mediating influence of smartphone use.

To examine the interactive effect between age and mobile phone use, this study constructed a multivariate linear regression model with dwell time as the dependent variable and mobile phone use, age group, and their interaction as independent variables (Table 6). The model fit showed a high overall goodness of fit (R2 = 0.407, adjusted R2 = 0.395), with all main effects reaching significance: mobile phone use had a significant positive impact on dwell time (B = 10.067, p < 0.001), and age group also showed a significant positive effect (B = 3.296, p = 0.021). However, the “mobile phone use × age group” interaction, while positive (B = 3.001), did not reach significance (p = 0.123), suggesting that the promoting effect of mobile phone use on dwell time is stronger among younger adults, but that the overall age difference was not significant enough to reach statistical significance.

Table 6.

Analysis of the interaction term of “age group * use smartphone”.

In summary, the influence of smartphone use on the neutral thermal threshold (NTT) exhibits a distinct stratification across age groups, with the degree of enhancement positively associated with individuals’ level of media immersion. Younger participants, characterized by higher usage frequency and deeper engagement, demonstrated a stronger “psychological desensitization effect,” in which attentional absorption and cognitive distraction reduce the subjective perception of thermal discomfort, thereby enhancing heat tolerance. In contrast, older participants, constrained by limited digital engagement and higher environmental sensitivity, showed relatively weaker media-mediated thermal regulation. Further analysis indicated that this pattern and its statistical significance remained consistent when the threshold of “effective smartphone use” was adjusted to 3, 5, 7, or 10 min, confirming the robustness of the media-mediated effect. These findings highlight the importance of incorporating age-related differences in digital media use into thermal adaptation research in cold-climate public spaces, offering valuable insights for behavior-oriented interventions and climate-responsive spatial design.

3.8. Summary and Milestones

In summary, the findings provide multi-dimensional evidence supporting the hypothesis that smartphone use may enhance thermal adaptation behaviors. Compared with non-users, smartphone users exhibited stronger attendance willingness and greater behavioral persistence under thermal exposure, with both their neutral thermal threshold (NTT) and critical thermal threshold (CTT) shifting toward higher temperature ranges, indicating a broader range of thermal tolerance. During high-temperature periods, users tended to maintain longer stay durations, particularly in optional or self-directed activity contexts. Further analyses revealed that this mediating effect of smartphone use was jointly moderated by activity type and age structure: the enhancement of thermal adaptation was more pronounced in individual, non-interactive activities than in social interactions, and showed a clear age-dependent gradient—most significant among young adults, moderate among middle-aged participants, and weakest among older adults. This stratified pattern corresponds closely with differences in digital media immersion, suggesting that younger users may experience a stronger desensitization effect through attention absorption and cognitive diversion, which mitigates heat discomfort perception and extends outdoor engagement. Overall, smartphone use appears to foster a mediated thermal adaptation mechanism that reshapes human-environment interactions, offering new empirical insight and design implications for adaptive public spaces in cold-climate regions.

4. Discussion

4.1. Potential Mechanisms Linking Smartphone Use and Thermal Adaptation

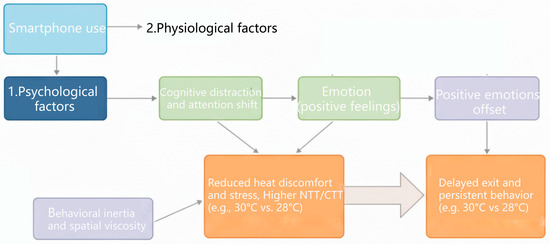

The results demonstrated that smartphone use was consistently associated with stronger behavioral tolerance to heat stress, including higher attendance under elevated UTCI values, longer stay durations, and delayed withdrawal at critical thermal thresholds. These findings resonate with existing psychological theories but also extend them into the context of outdoor thermal environments (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Illustration of the mechanism of heat adaptation.

From the perspective of cognitive distraction, immersion in digital content occupies attentional resources and reduces sensitivity to external stimuli, thereby attenuating the perception of discomfort caused by heat and solar radiation [35,63]. From the perspective of emotional regulation, smartphone-based entertainment or communication can elicit positive affect, which may counterbalance the negative emotions associated with thermal stress [34,64]. Finally, theories of behavioral inertia and spatial stickiness suggest that once individuals are engaged in an activity, they tend to persist rather than terminate prematurely [65,66]. Smartphones reinforce this inertia by sustaining engagement, thus delaying the behavioral response to discomfort.

The present study therefore situates these psychological mechanisms within the thermal adaptation domain, proposing that smartphone use functions as a “behavioral mediator” that alters the timing and intensity of adaptive responses. Rather than replacing existing theories, our contribution lies in contextualizing and integrating them, highlighting how digital immersion interacts with environmental stressors to reshape adaptation behavior.

4.2. NTT and CTT Elevation in Cold-Climate Contexts

Segmented regression analysis revealed that smartphone users had higher NTTs and CTTs compared to non-users (30 °C vs. 28 °C, and 40 °C vs. 37 °C, respectively). Although modest in absolute value, these shifts carry particular significance in cold-climate cities. For instance, in Changchun, nearly one-quarter of summer days fall within the 28–30 °C range. On these days, non-users are likely to approach or exceed their thermal neutrality threshold, while smartphone users can still sustain activity. Consequently, smartphone use effectively enlarges the “usable thermal window” of public spaces, enhancing attendance and spatial efficiency under heat stress.

Although a seemingly minor difference of 2 °C, this gap carries substantial implications in cold-climate regions. Taking Changchun as an example, meteorological records indicate that days with maximum temperatures between 28 °C and 30 °C account for roughly one-quarter of the entire summer season. This suggests that during a significant portion of summer days, non-users of smartphones are already approaching their upper thermal tolerance limit, while users remain capable of continued activity and spatial engagement. In other words, smartphone use effectively expands the “thermally active window” within which residents can comfortably occupy public spaces, thereby enhancing spatial utilization and opportunities for social interaction.

If this analysis were applied to tropical regions, the results might differ. In high-temperature and high-humidity cities, residents generally possess stronger thermal adaptability, and their neutral thermal thresholds (NTT) may already reach or exceed 30 °C. Under such conditions, the “threshold-elevating” effect of smartphone use may be less pronounced, or even offset by physiological limits under extreme heat. Hence, the distinctive value of this study lies in uncovering the unique dynamics of summer thermal adaptation in cold-climate contexts: when the population’s thermal tolerance baseline is relatively low, digital media use functions as a critical psychological buffering mechanism, sustaining outdoor engagement and spatial activity far more effectively than in regions where high heat is the norm.

4.3. Moderating Role of Activity Types

The moderating effect of activity type was evident in the results: while smartphone use increased NTT by only ~1 °C during social activities, the difference reached 4.5 °C during optional activities. This finding suggests that the adaptive value of smartphones is highly context-dependent.

In social activities, collective interaction itself provides psychological support and emotional buffering [67], thereby reducing the marginal role of smartphones. By contrast, in optional or solitary activities—where individuals lack external reinforcement—exposure to environmental stress is more immediate [68]. In these scenarios, digital immersion serves as an effective compensatory mechanism, delaying withdrawal and prolonging stay. The evidence therefore indicates that smartphone use does not uniformly enhance heat tolerance but rather interacts dynamically with the type and motivation of activity.

4.4. Theoretical Contributions: A Media–Environment–Behavior Coupling Framework

Traditional thermal adaptation research has emphasized the coupling of physical exposure and physiological feedback, with limited attention to cognitive and media-related factors. This study extends the theoretical boundaries by introducing a media–environment–behavior coupling framework.

This framework posits that media immersion alters the perceived intensity of thermal stimuli; environmental exposure, when mediated by digital engagement, is reconstructed into a new perception–behavior chain; and behavioral feedback is no longer a direct reaction to temperature but rather a delayed or modified response shaped by media-driven cognitive modulation.

This exploratory framework integrates insights from psychology and media studies into the field of outdoor thermal comfort, illustrating how digital behaviors reconfigure human–environment interactions. It highlights the growing necessity of considering technological immersion as a co-regulatory factor in adaptation studies, particularly under climate warming.

4.5. Practical Implications for Public Space Design

From a practical perspective, the findings of this study indicate that climate-adaptive design for public spaces in cold-climate regions should not be confined to traditional physical cooling measures such as shading, greening, and ventilation optimization. It should also incorporate the emerging behavioral characteristic of digital media use. The results reveal that smartphone use can significantly enhance individuals’ thermal adaptability, particularly among younger groups and during non-interactive activities. This suggests that media use has become a key mediating variable in human–environment interactions, and its spatial requirements should be integrated into future design paradigms.

Against this backdrop, designers can foster thermal comfort and behavioral continuity across different user groups by constructing media-friendly, climate-adaptive spaces. For instance, in areas with higher summer heat risk, shaded rest points equipped with Wi-Fi and charging facilities can allow users to continue digital engagement in a safe and comfortable environment. Seating arrangements with high backrests and adequate spacing can meet ergonomic and ventilation needs while improving posture comfort for prolonged smartphone use. Meanwhile, smart park systems can be employed to monitor real-time crowd distribution and heat exposure, enabling dynamic spatial regulation and feedback through digital infrastructure—ultimately enhancing overall spatial resilience.

Furthermore, attention should be given to the heterogeneity of media use across age groups. Younger users, characterized by higher media immersion, demonstrate stronger heat tolerance and spatial attachment, whereas middle-aged and elderly groups, with lower digital engagement, remain more dependent on direct physical comfort regulation. Therefore, climate-adaptive design should adopt differentiated strategies: for younger users, emphasize the integration of digital experience with environmental comfort; for older adults, prioritize direct physical improvements such as shading, ventilation, and accessible resting areas. Through this dual-friendly strategy—mediated and physiological—designers can balance generational differences in thermal behavior patterns and create public spaces in cold regions that combine digital convenience with climate adaptability.

It is worth emphasizing that the conclusions of this study do not advocate relying on smartphones to offset heat risks but rather indicate that digital media has become an important behavioral regulating factor whose potential role in climate-adaptive design should be recognized. In addition, the protective association of smartphone use does not imply that vulnerable groups (such as the elderly and children) obtain the same level of thermal adaptation benefits [69,70]. On the contrary, these groups may rely more on physical environmental modifications and social support [71,72]. Therefore, policy recommendations should simultaneously include shading, cooling, and warning measures targeted at vulnerable groups.

4.6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Several limitations should be noted. First, the short observation period restricted the capture of long-term or extreme heat adaptation patterns. In addition, the observation window (09:00–12:00) captures only the morning period, when solar radiation and air temperature are still rising. Because thermal perception and behavioral adaptation vary diurnally, the Neutral Thermal Threshold (NTT) and Critical Thermal Threshold (CTT) identified in this study may differ in the afternoon, particularly around the peak radiation hours. The thresholds reported here should therefore be interpreted as morning-specific estimates. Future studies should extend observations into the afternoon to capture potential variations in NTT and CTT across the full diurnal cycle. Moreover, observations of extreme temperatures above 35 °C were scarce, which constrained the model’s goodness of fit and the reliability of conclusions in the high-temperature range. Consequently, the estimation of the critical thermal tolerance (CTT), particularly the predicted value approaching 40 °C, carries a degree of uncertainty and should be regarded as an extrapolation based on observed trends rather than direct empirical evidence. Future studies should extend the monitoring period—especially during heatwave events—to improve the robustness and validity of the model under conditions of high thermal exposure. Second, the sample was not stratified by age, gender, or shade-seeking behavior, which may influence adaptive responses. Third, the study relied solely on passive observation, lacking subjective thermal perception and physiological measures; thus, proposed mechanisms remain partly inferential. Third, this study relied solely on passive observation, lacking concurrent measurements of subjective thermal perception and physiological indicators, which limits the explanatory power of the underlying mechanisms. Future research could incorporate questionnaire-based surveys or physiological monitoring to more directly assess the actual effects of smartphone use on thermal perception and physiological stress responses. Such an approach would provide stronger empirical evidence for the causal mechanisms underlying “mediated thermal adaptation.” In addition, smartphone use types were not differentiated, and data were limited to a single cold-climate park. Future research should extend observation periods, incorporate subjective and physiological data, conduct stratified analyses, and compare across climatic zones to establish a more comprehensive understanding of media–thermal adaptation mechanisms.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the role of smartphone use in shaping thermal adaptation behaviors in outdoor public spaces in a cold-climate city. Based on field microclimate monitoring and Passive Activity Observation in Jingyue Central Park, the results consistently showed that smartphone users exhibited greater behavioral resilience to heat exposure than non-users. Specifically, their Neutral Temperature Threshold (NTT) and Critical Temperature Threshold (CTT) increased by approximately 2 °C and 3 °C, respectively, with the effect most pronounced during optional activities, where the NTT difference reached 4.5 °C.

Although modest in absolute terms, these threshold shifts are particularly significant in cold-climate regions. In Changchun, nearly one-quarter of summer days fall between 28 and 30 °C. On such days, non-users approach their thermal limits, while smartphone users can continue outdoor activity, thereby expanding the “usable thermal window” of public spaces. This indicates that smartphones act as a compensatory factor for populations with lower baseline heat tolerance, a dynamic that may differ in warmer climates.

Theoretically, the study introduces a media–environment–behavior coupling framework, highlighting how smartphones reshape thermal adaptation through distraction, emotional regulation, and behavioral persistence. This extends conventional thermal comfort research beyond physical and physiological dimensions, offering a new perspective on digitally mediated adaptation.

Practically, the findings suggest that climate adaptation design in cold-climate cities should integrate media-friendly elements, such as shaded areas with Wi-Fi and charging facilities, ergonomic seating, and smart park infrastructure. Recognizing digital engagement as part of adaptive behavior can improve both the resilience and usability of urban spaces under warming conditions.

Limitations include the short observation period, absence of subjective and physiological measures, and lack of demographic stratification or smartphone-use typologies. Future research should expand temporal and spatial coverage, incorporate multi-method data, and compare across different climatic zones to refine understanding of media-driven thermal adaptation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L. and Z.L.; Methodology, H.Z., M.L. and Z.L.; software, H.Z. and Z.L.; validation, H.Z., X.J. and Z.L.; formal analysis, X.J. and Z.L.; data curation, X.J. and Z.L.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Z. and Z.L.; writing—review and editing, H.Z., X.J., M.L. and Z.L.; supervision, H.Z., X.J. and M.L.; funding acquisition, H.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52178042). Receiver: Hongyu Zhao, the Key projects of Jilin Provincial Department of Science and Technology (grant number 20210203213SF), and the Grantee is Hongyu Zhao.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the grants support from the Key projects of Jilin Provincial Department of Science and Technology (grant number 20210203213SF), and the Grantee is Hongyu Zhao.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exits in the submission of this manuscript, and manuscript is approved by all authors for publication.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GT | black globe temperature (°C) |

| T | air temperature (°C) |

| V | wind speed (m/s) |

| the emissivity of the globe surface (0.95) | |

| D | the diameter of the black globe (0.05 m) |

| Tmrt | Mean radiant temperature (°C) |

References

- Lam, C.Y.; Gallant, E.; Tapper, N.J. Short-term changes in thermal perception associated with heatwave conditions in Melbourne, Australia. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2018, 136, 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ouyang, W.; Yin, S.; Tan, Z.; Ren, C. Microclimate and its influencing factors in residential public spaces during heat waves: An empirical study in Hong Kong. Build. Environ. 2023, 236, 110225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, N.; Yin, X.; Wu, C.; Chen, M.; Jiao, Y.; Yue, T. Global future population exposure to heatwaves. Environ. Int. 2023, 178, 108049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Chen, H. Anthropogenic Influence Has Increased the Nighttime Heat Stress Risks in Eastern China. Earth’s Future 2024, 12, e2023EF004406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relvas, H.; Monjo, R.; Coelho, S.; Ferreira, J. Rising Temperatures, Rising Risks: Heat-Related Mortality in Europe Under Climate Change. Earth Syst. Environ. 2025, 25, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, D.; Liu, W.; Gan, T.; Liu, K.; Chen, Q. A review of mitigating strategies to improve the thermal environment and thermal comfort in urban outdoor spaces. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 661, 337–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wang, Y.; Xue, S. Research on the Heat Comfort in Winter in Urban Parks in Cold Areas Based on Different Activity Intensities. Build. Sci. 2023, 39, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Zhang, L.; Schlink, U.; Hu, X.; Meng, Q.; Gao, J. Impact of urban land use and anthropogenic heat on winter and summer outdoor thermal comfort in Beijing. Urban Clim. 2025, 59, 102306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olwig, K.R. Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space. Landsc. J. 1989, 8, 54–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shashua-Bar, L.; Tzamir, Y.; Hoffman, M.E. Thermal effects of building geometry and spacing on the urban canopy layer microclimate in a hot-humid climate in summer. Int. J. Climatol. 2004, 24, 1729–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, E. Influence of urban geometry on outdoor thermal comfort in a hot dry climate: A study in Fez, Morocco. Build. Environ. 2006, 41, 1326–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-P.; Matzarakis, A.; Hwang, R.-L. Shading effect on long-term outdoor thermal comfort. Build. Environ. 2010, 45, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, E.; Ruiz, M.A.; Canton, A.; Lesino, G. Thermal comfort in forested urban canyons of low building density. An assessment for the city of Mendoza, Argentina. Build. Environ. 2012, 58, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellei, M.; Herrera, M.; Fosas, D.; Natarajan, S. The influence of relative humidity on adaptive thermal comfort. Build. Environ. 2017, 124, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, S.L.; Chow, W.T.L. How “hot” is too hot? Evaluating acceptable outdoor thermal comfort ranges in an equatorial urban park. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2019, 63, 801–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, A.; Becerik-Gerber, B. A comparative study of predicting individual thermal sensation and satisfaction using wrist-worn temperature sensor, thermal camera and ambient temperature sensor. Build. Environ. 2019, 160, 106223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkurikiyeyezu, K.N.; Suzuki, Y.; Lopez, G.F. Heart rate variability as a predictive biomarker of thermal comfort. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2020, 9, 1465–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, D.; Lian, Z.; Liu, W.; Guo, C.; Liu, W.; Liu, K.; Chen, Q. A comprehensive review of thermal comfort studies in urban open spaces. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 742, 140092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana, M.; Schiavon, S.; Tartarini, F.; Kim, J.; Miller, C. Cohort comfort models–Using occupants’ similarity to predict personal thermal preference with less data. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2208.03078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissetto, R.; Rambow, R.; Schweiker, M. Assessing comfort in the workplace: A unified theory of behavioral and thermal expectations. Build. Environ. 2022, 216, 109015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Zhang, X.; Yang, L.; Liu, Y.; Cong, Y.; Gao, W. Correlation analysis of thermal comfort and physiological responses under different microclimates of urban park. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2022, 34, 102044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avci, A.B.; Balci, G.A.; Basaran, T. Exercise and resting periods: Thermal comfort dynamics in gym environments. Build. Simul. 2024, 17, 1557–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Liu, W.; Liu, K. Influence of Thermal Environment on Attendance and Adaptive Behaviors in Outdoor Spaces: A Study in a Cold-Climate University Campus. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Yao, R.; Xu, T.; Zhang, S. The impact of heatwaves on human perceived thermal comfort and thermal resilience potential in urban public open spaces. Build. Environ. 2023, 242, 110586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, E.; Cheng, V. Urban human thermal comfort in hot and humid Hong Kong. Energy Build. 2012, 55, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-P.; Tsai, K.-T.; Liao, C.-C.; Huang, Y.-C. Effects of thermal comfort and adaptation on park attendance regarding different shading levels and activity types. Build. Environ. 2013, 59, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Guan, X.; Lu, Y. Deciphering the effect of user-generated content on park visitation: A comparative study of nine Chinese cities in the Pearl River Delta. Land Use Policy 2024, 144, 107259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Lin, X.; Shi, H. Exploring associations between the elders’ seasonal park visitation and the built environment through the lens of urban location’s irreplaceability. Appl. Geogr. 2025, 186, 103826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Liu, P.; Song, Y. Seasonal variations in urban park characteristics and visitation patterns in Atlanta: A big data study using smartphone user mobility. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 91, 128166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, M.; Cooper, N.R.; Andrews, L.; Hacker Hughes, J.; Juanchich, M.; Rakow, T.; Orbell, S. Outdoor recreational activity experiences improve psychological wellbeing of military veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder: Positive findings from a pilot study and a randomised controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilhelmson, B.; Thulin, E.; Elldér, E. Where does time spent on the Internet come from? Tracing the influence of information and communications technology use on daily activities, Information. Commun. Soc. 2016, 20, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraut, R.; Patterson, M.; Lundmark, V.; Kiesler, S.; Mukophadhyay, T.; Scherlis, W. Internet paradox: A social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being? Am. Psychol. 1998, 53, 1017–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, N.H. Sociability, Interpersonal Relations, and the Internet. Am. Behav. Sci. 2001, 45, 420–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebold, M.J.; Lepp, A.; Sanders, G.J.; Barkley, J.E. The Impact of Cell Phone Use on the Intensity and Liking of a Bout of Treadmill Exercise. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, S.; Henrich, C. Texting as a distraction to learning in college students. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 36, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J.S.; Chen, C.-C. Does using a smartphone for work purposes “ruin” your leisure? Examining the role of smartphone use in work–leisure conflict and life satisfaction. J. Leis. Res. 2018, 49, 236–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepp, A.; Li, J.; Barkley, J.E.; Salehi-Esfahani, S. Exploring the relationships between college students’ cell phone use, personality and leisure. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 43, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amerson, K.; Rose, J.; Lepp, A.; Dustin, D. Time on the trail, smartphone use, and place attachment among Pacific Crest Trail thru-hikers. J. Leis. Res. 2019, 51, 308–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennell, C.; Barkley, J.E.; Lepp, A. The relationship between cell phone use, physical activity, and sedentary behavior in adults aged 18–80. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 90, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorp, A.A.; Owen, N.; Neuhaus, M.; Dunstan, D.W. Sedentary Behaviors and Subsequent Health Outcomes in Adults. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 41, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tochihara, Y.; Wakabayashi, H.; Lee, J.-Y.; Wijayanto, T.; Hashiguchi, N.; Saat, M. How humans adapt to hot climates learned from the recent research on tropical indigenes. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2022, 41, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Choi, H.; Park, S.; Park, C.; Lee, J.; Lee, U.; Lee, S.J. Fire in Your Hands: Understanding Thermal Behavior of Smartphones. In Proceedings of the MOBICOM’19: 25th Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking, Los Cabos, Mexico, 21–25 October 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, E.; Boland, J. Passive activity observation (PAO) method to estimate outdoor thermal adaptation in public space: Case studies in Australian cities. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2018, 64, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potchter, O.; Cohen, P.; Lin, T.-P.; Matzarakis, A. A systematic review advocating a framework and benchmarks for assessing outdoor human thermal perception. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 833, 155128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, W.; Qin, Z.; Mu, T.; Ge, Z.; Dong, Y. Evaluating thermal comfort indices for outdoor spaces on a university campus. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, E.; Boland, J. Limits of thermal adaptation in cities: Outdoor heat-activity dynamics in Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2018, 61, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, E.; Sivam, A.; Boland, J. Resilience to heat in public space: A case study of Adelaide, South Australia. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2015, 59, 1833–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, H.E.; Zimmermann, N.E.; McVicar, T.R.; Vergopolan, N.; Berg, A.; Wood, E.F. Present and Future Köppen-Geiger Climate Classification Maps at 1-km Resolution. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 180214, Erratum in: Present and future Köppen-Geiger climate classification maps at 1-km resolution. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 274. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-020-00616-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bröde, P.; Fiala, D.; Błażejczyk, K.; Holmér, I.; Jendritzky, G.; Kampmann, B.; Tinz, B.; Havenith, G. Deriving the operational procedure for the Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI). Int. J. Biometeorol. 2011, 56, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, D.; Chen, B.; Liu, K. Quantification of the influence of thermal comfort and life patterns on outdoor space activities. Build. Simul. 2019, 13, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Gao, X.; Lindquist, M.; Song, Y.; Shen, X. Temporal and spatial dynamics of peak-time urban park visitation: Investigating influencing factors across scales in post-pandemic detroit. Urban For. Urban Green. 2025, 112, 128871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 55-2020; Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy (New Standard). ASHRAE—American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, Inc.: Peachtree Corners, Georgia, 2020.

- International Standard 7726 ISO; Thermal Environments. Instruments and Methods for Measuring Physical Quantities. International Standard Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Gehl, J.; Svarre, B. How To Study Public Life; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.H.; Tian, L.; Zhu, L.; Cao, Y.; Chan, S.K.W.; Dong, D.; Cheung, W.L.A.; Wong, E.L.Y. Age Differences in Electronic Mental Health Literacy: Qualitative Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e59131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, M.; Oosterbroek, J. Applications, and Services. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Pattern Recognition—ICPR 2012, Tsukuba, Japan, 11–15 November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Roehrick, K.; Vaid, S.S.; Harari, G.M. Situating smartphones in daily life: Big Five traits and contexts associated with young adults’ smartphone use. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 125, 1096–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazejczyk, K.; Epstein, Y.; Jendritzky, G.; Staiger, H.; Tinz, B. Comparison of UTCI to selected thermal indices. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2011, 56, 515–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Cheng, W.; Jim, C.Y.; Morakinyo, T.E.; Shi, Y.; Ng, E. Heat mitigation benefits of urban green and blue infrastructures: A systematic review of modeling techniques, validation and scenario simulation in ENVI-met V4. Build. Environ. 2021, 200, 107939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Chen, S.X. Statistical Inference for Four-Regime Segmented Regression Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.04384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priulla, A.; D’Angelo, N. Sequential hypothesis testing for selecting the number of changepoints in segmented regression models. Environ. Ecol. Stat. 2024, 31, 583–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pukelsheim, F. The Three Sigma Rule. Am. Stat. 1994, 48, 88–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breves, P.; Stein, J.-P. Cognitive load in immersive media settings: The role of spatial presence and cybersickness. Virtual Real. 2022, 27, 1077–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Koval, P.; Kostakos, V.; Goncalves, J.; Wadley, G. “Instant Happiness”: Smartphones as tools for everyday emotion regulation. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2023, 170, 102958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebers, T.; Beyens, I.; Valkenburg, P.M. The effects of fragmented and sticky smartphone use on distraction and task delay. Mob. Media Commun. 2023, 12, 45–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostopoulos, I.; Stocchi, L.; Pourazad, N.; Michaelidou, N. Mobile applications’ stickiness: A review and future research program. J. Strateg. Mark. 2025, 76, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Main, A.; Yung, S.T.; Chen, Y.; Zawadzki, M.J. Predicting emotion regulation strategies from aspects of the social context in everyday life. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2024, 42, 568–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S. Proximity to nature prevents problematic smartphone use: The role of mindfulness. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 16699–16710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, Z.; Chen, H.; Li, Y. Problematic Smartphone Use Among Middle School and High School Students in China: A Cross-Sectional Survey Study. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2024, 32, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, J.M.; Helmer, C.K.; Al-Shoaibi, A.A. Beyond Screen Time—Addictive Screen Use Patterns and Adolescent Mental Health. JAMA 2025, 334, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.; He, G.; Zheng, H.; Ai, J. What makes Chinese adolescents glued to their smartphones? Using network analysis and three-wave longitudinal analysis to assess how adverse childhood experiences influence smartphone addiction. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 163, 108484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Ren, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Li, L. What affects the use of smartphones by the elderly? A hybrid survey from China. Natl. Account. Rev. 2023, 5, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).