1. Introduction

Enhancing the environmental safety of energy systems that significantly contribute to the depletion of non-renewable natural resources and atmospheric pollution represents one of the most critical challenges facing modern society [

1]. The generation of affordable and clean electricity aims to satisfy the constantly growing energy demand of the population and industry without exacerbating environmental degradation, thus ensuring decent living conditions for both current and future generations.

The decarbonization of the energy sector is particularly urgent in the context of evolving carbon pricing instruments, which are designed to create economic incentives for industrial enterprises to reduce anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions [

2]. Consequently, power generation companies operating cleaner energy complexes will pay less for carbon dioxide emissions per kilowatt-hour of electricity generated than stations utilizing less advanced energy units.

The impact of carbon pricing instruments on energy system efficiency must also be considered in countries lacking national carbon taxes or emission trading systems. This necessity is driven by the rapid development of cross-border carbon adjustment mechanisms (CBAMs) planned for full implementation in the near future. Under this mechanism, importers are required to report embedded direct and indirect CO

2 emissions and to purchase corresponding CBAM certificates to cover their residual carbon footprint. The most developed such instrument is operated by the European Union, where the price of CBAM certificates is aligned with the price of emission allowances under the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS). Consequently, advancing clean power generation is becoming a key strategy for maintaining the competitiveness of domestic export-oriented, energy-intensive industries [

3].

Within the framework of energy sector decarbonization, the transition to renewable energy sources holds a special place. Studies demonstrate that the integration of wind, solar, and hydroelectric power plants into the energy system is an effective means for reducing greenhouse gas emissions [

4,

5,

6]. However, despite the high environmental benefits of using renewables for energy production, these technologies possess several inherent characteristics that prevent their unlimited integration into the power system structure. Specifically, the deployment of new hydropower plants is constrained by the geographical features of a given region, while the scaling of wind and solar generation is challenged by the inherent variability of their energy output and high capital costs.

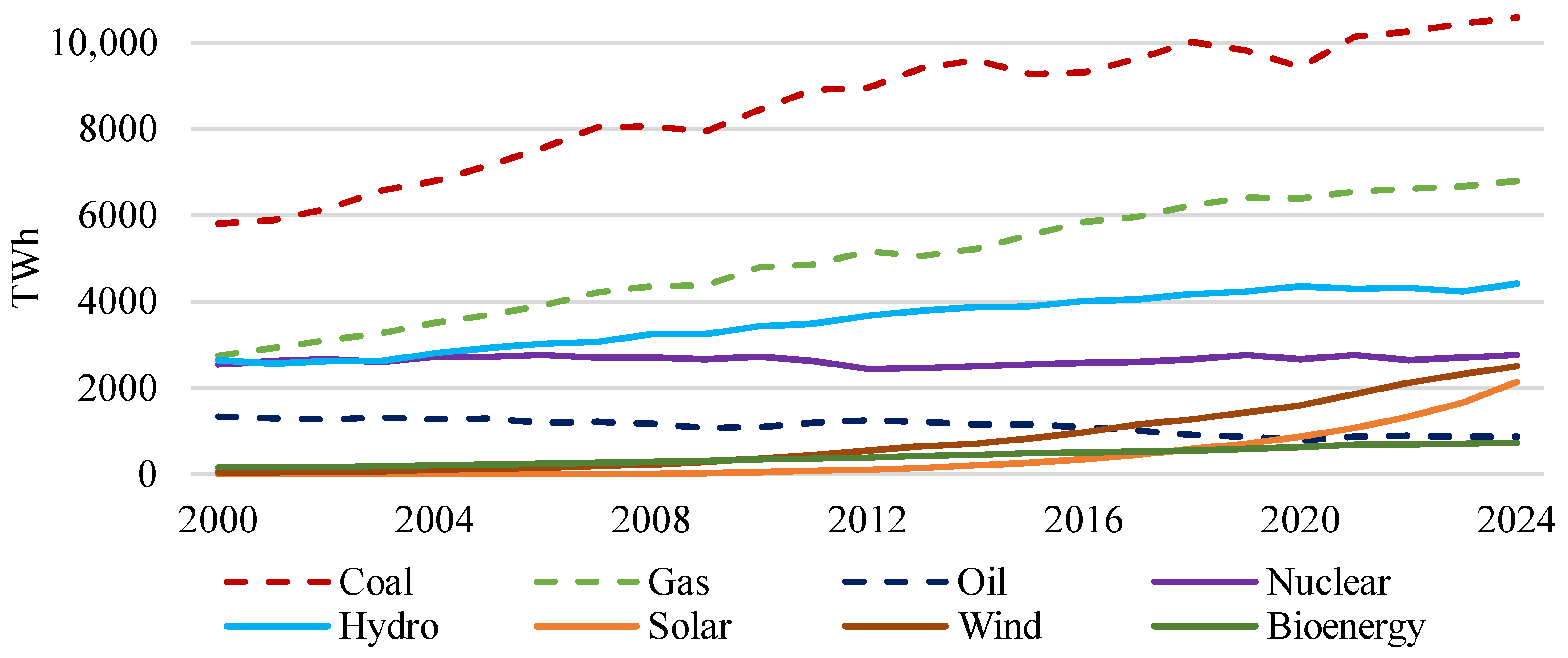

For these reasons, conventional fuels continue to serve as the primary energy sources in the power systems of most countries worldwide (

Figure 1). Within the context of the global climate agenda, natural gas is highlighted as the most promising among them. This is due to the resource’s accessibility and the lower volume of harmful emissions released into the atmosphere during its combustion compared to the amount of CO

2 emitted from burning coal and fuel oil [

7,

8].

Therefore, in light of current global trends in decarbonization and energy efficiency, a relevant direction for building sustainable energy systems is the development of highly efficient and low-carbon natural gas-fired energy complexes. Simultaneously, planning the structure of an energy system requires maintaining a balance between its energy, environmental, and economic performance indicators. Consequently, the selection of prospective generation technologies must consider multiple objectives, reflecting the economical use of fuel and energy resources, the extent of environmental damage, and the economic viability of operating advanced power units.

The issues of multi-objective optimization in the energy sector have been studied by [

10,

11,

12]. Notable research includes works focused on optimizing individual energy equipment [

13,

14,

15] and energy systems as a whole [

16,

17,

18]. However, a significant portion of research addresses optimization of renewable energy systems [

19,

20,

21], predominantly comprising solar, wind, and hydroelectric power facilities, as well as hybrid energy systems [

22,

23] that represent a compromise between renewable sources and conventional generation. In contrast, the application of multi-objective optimization methods to advanced natural gas-fired energy complexes is primarily limited to individual power units in the literature [

24]. Consequently, the problem of determining the optimal generation structure comprising advanced gas-fired technologies remains unaddressed and requires further investigation.

To enhance the accuracy, reliability, and efficiency of decision-making processes, multi-objective optimization problems require an ensemble of mathematical tools. The energy sector has widely adopted combinations of Pareto optimization with variants of the Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS), differing in their approach to assessing the relative importance of optimality criteria: AHP-TOPSIS, EWM-TOPSIS, Fuzzy TOPSIS, among others [

25,

26]. However, energy modeling often involves strongly correlated optimality criteria, which can distort optimization outcomes. The objective reduction algorithm based on principal component analysis (PCA) employed in this study enables a reduction in the number of criteria for subsequent optimization while minimizing the loss of useful information, thereby yielding a more representative and higher-quality Pareto front.

Despite numerous studies addressing multi-objective optimization of energy production structures, existing research often relies on static models or short-term planning horizons, which inadequately represent the long-term nature of energy planning. Determining the optimal development pathway for an energy system requires accounting for the dynamics of external environmental parameters, which can manifest both as price factors within the model and as its constraints.

Therefore, the aim of our paper is to develop a multi-objective approach for determining the optimal electric power generation structure amidst the development of advanced natural gas-fired energy complexes, accounting for the dynamics of external parameters such as fuel costs, carbon prices, and evolving environmental performance requirements.

Compared to existing research in the field, this study employs an ensemble approach to solving a multi-objective optimization problem. This enables more comprehensive investigation of Pareto-optimal generation structures, enhancing the representativeness of modeling results. Furthermore, the implemented methodology accounts for the progressive tightening of environmental requirements for electric power generation systems over time, while incorporating analysis of observed trends in carbon allowance and hydrocarbon fuel markets. This distinctive feature facilitates focus on long-term energy planning horizons, thereby enabling the transition from analyzing contemporary energy systems to studying systems comprising innovative advanced generation technologies.

2. Analysis of Advanced Natural Gas-Fired Power Plants

With the strengthening of energy conservation and decarbonization trends in energy production, the most critical requirements for power generation units have become high fuel efficiency and minimal emissions to the atmosphere. Among existing generation facilities, combined cycle gas turbine (CCGT) plants most closely meet these requirements [

27]. The primary method for enhancing CCGT efficiency is associated with increasing the initial parameters of the working fluid. However, raising the temperature of the working medium at the gas turbine inlet necessitates the use of more heat-resistant and expensive steels and alloys in the power unit construction. Currently, this approach significantly increases the capital cost of CCGT plants and, consequently, the levelized cost of electricity they generate, which is not always offset by the fuel savings achieved through higher efficiency.

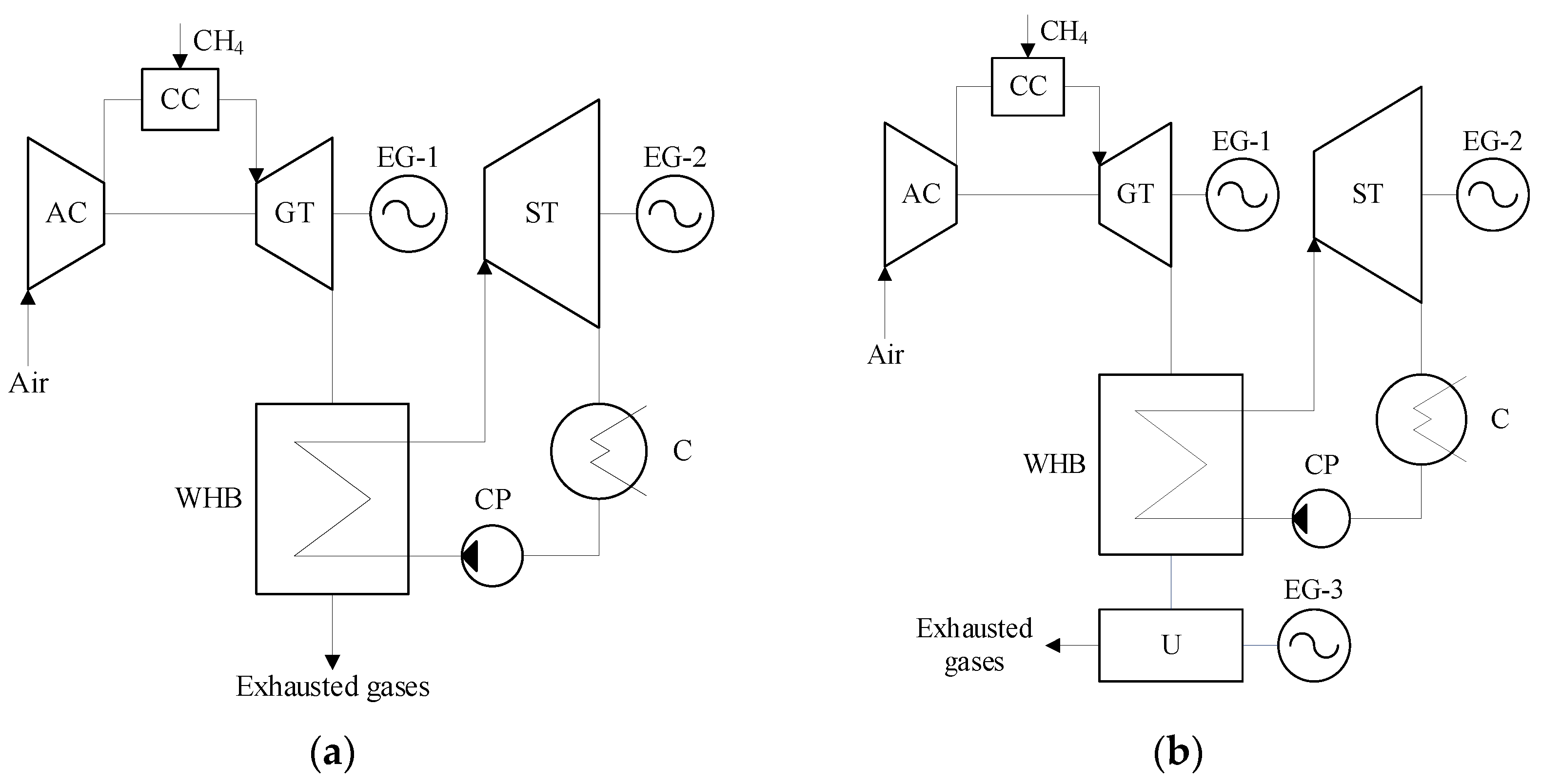

An alternative approach to improving the energy efficiency of a combined cycle plant is the productive utilization of the gas turbine’s exhaust heat potential [

28]. This method involves transitioning from binary combined cycle gas turbines (CCGTs) to trinary ones with integrated additional power cycles based on an organic working fluid, designed for efficient recovery of low-grade waste heat from flue gases. Such a modification of the CCGT thermal cycle increases the net electrical efficiency of the power unit, which helps reduce fuel consumption and, consequently, lowers the volume of greenhouse gases emitted into the atmosphere. The principal thermal diagrams of the prospective highly efficient energy complexes are shown in

Figure 2.

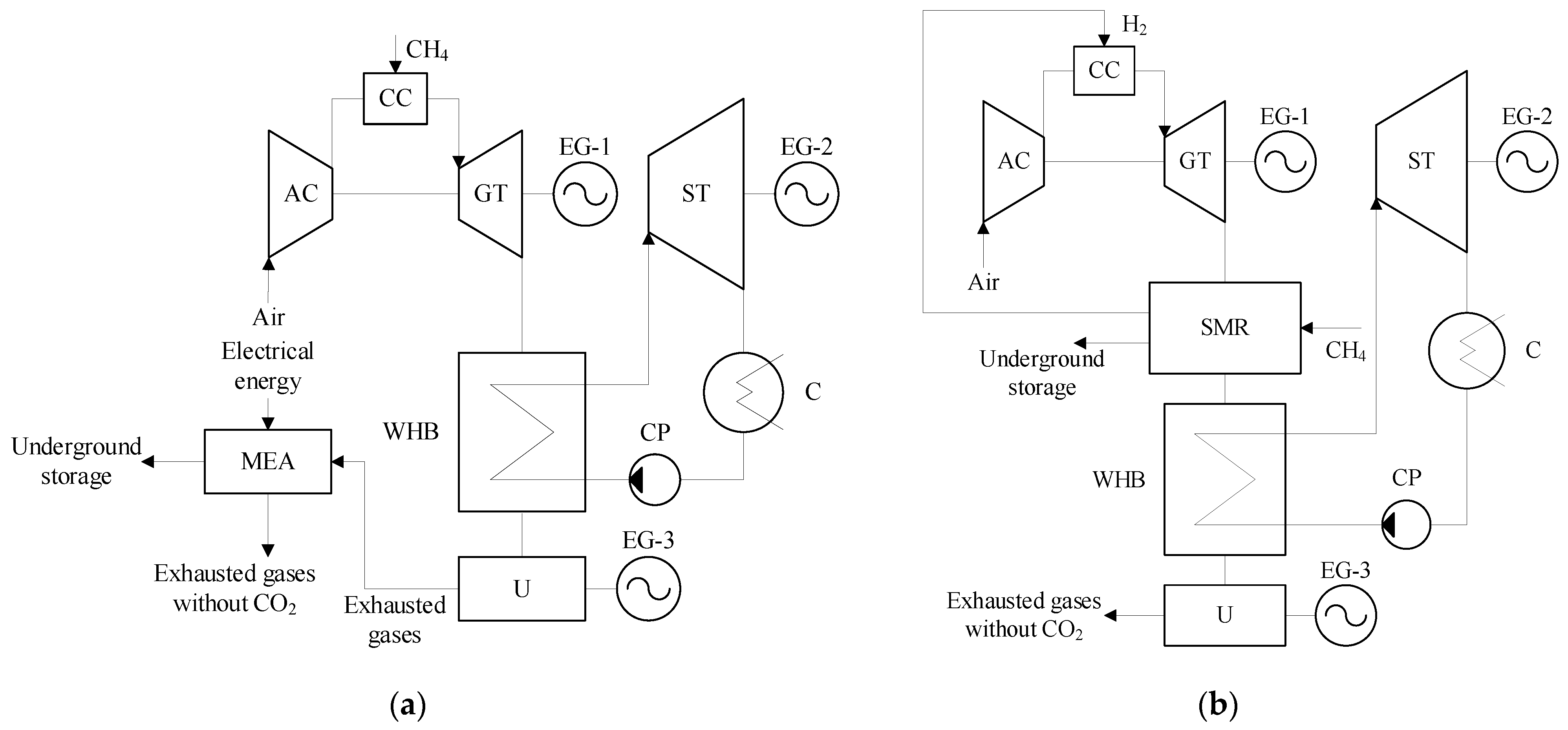

In addition to enhancing the fuel efficiency of combined cycle plants, ensuring the environmental safety of electricity production is equally important. Consequently, low-carbon power plants are being developed on the basis of highly efficient generation technologies, featuring integrated carbon capture systems implemented both before fuel combustion (pre-combustion technology) and after (post-combustion technology) [

29,

30]. The most widely used industrial technology for post-combustion capture is flue gas treatment with monoethanolamine (MEA) [

31,

32]. This process involves capturing carbon dioxide from the gas turbine exhaust gases through an absorption reaction between CO

2 and monoethanolamine. The resulting solution is then heated in a desorber, triggering the release of the captured carbon dioxide, which is subsequently directed for storage.

In turn, the most efficient and cost-effective method for removing CO

2 from fuel prior to combustion is the integration of power generation equipment with a steam methane reforming (SMR) unit [

33]. In the SMR process, steam reacts with natural gas inside a reformer furnace at high temperatures and moderate pressures in the presence of a nickel-based catalyst, leading to the production of a hydrogen-rich synthesis gas (syngas) [

34]. The syngas produced by steam methane reforming is then directed to an absorption unit, where nearly pure hydrogen is separated for use as fuel in a gas turbine. Concurrently, carbon dioxide is removed from the gas stream and is subsequently sent for storage. The principal thermal diagrams of the prospective low-carbon energy complexes are presented in

Figure 3.

Within the context of the global climate agenda, increasing attention is being paid to the development of carbon-free power plants based on oxy-fuel combustion technology [

35,

36]. In contrast to conventional power plants, oxy-fuel combustion cycles are characterized by the absence of greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere, achieved through the implementation of a closed-loop gas turbine cycle. In this process, a portion of the released CO

2 is recirculated back into the combustion chamber to act as a heat transfer medium, while the remaining carbon dioxide is directed for storage. Furthermore, this power generation technology offers high energy efficiency, attained by using oxygen instead of air as the oxidizer. The exclusion of inert nitrogen, which does not participate in combustion, enables higher fuel combustion temperatures, thereby increasing the power unit’s efficiency. However, this necessitates the use of more heat-resistant and expensive steels and alloys in the power unit construction, which increases the capital cost of the power plant, as well as subsequent maintenance and repair expenses. The principal thermal diagram of the carbon-free energy complexes is presented in

Figure 4.

From the analysis of the presented technological solutions, the key techno-economic characteristics of advanced natural gas-fired power plants have been identified (

Table 1). Specifically, high-efficiency generation technologies (binary and trinary cycles) are characterized by high fuel efficiency and low specific capital cost per unit of installed capacity, but exhibit a high volume of CO

2 emissions per unit of electricity generated. In contrast, low-carbon energy complexes (trinary cycle with MEA, trinary cycle with SMR) feature a lower specific carbon dioxide emission intensity, which leads to an increase in the power unit’s cost and a decrease in its electrical efficiency due to the additional energy required for carbon capture. Conversely, carbon-free power plants (trinary cycles with oxy-fuel combustion) are distinguished by the complete absence of greenhouse gas emissions and higher fuel efficiency compared to low-carbon plants, albeit with a higher observed specific capital cost.

3. Methods and Materials

In developing a multi-objective optimization methodology for the power generation structure, the first essential step is to define the energy system’s optimality criteria that capture its techno-economic attributes from the perspectives of energy efficiency, environmental safety, and economic competitiveness.

The economic efficiency of a power system is largely determined by the cost of the energy produced. For an individual power unit, the cost of annual electricity production,

C (

$), can generally be represented by the ratio:

where

CF—fuel costs,

$;

CD—depreciation charges,

$;

CW—labor costs and social security contributions,

$;

CR—repair costs,

$;

CO—other costs,

$;

CE—CO

2 emission costs,

$.

In turn, the volume of annual electrical energy production is described by the formula:

where

Q is the annual amount of electricity generated, kWh;

T is the number of hours of useful use of power, h.

Fuel costs constitute a substantial share of the structure of electricity production costs:

where

b is the consumption of equivalent fuel, grams of equivalent fuel/kWh;

is the calorific value of equivalent fuel, 7000 kcal/kg;

is the calorific value of natural gas, kcal/m

3;

Pfuel is the cost of natural gas,

$/thousand m

3.

To calculate depreciation charges, the straight-line method over the technical lifetime of the power unit was selected:

where

Tl is the useful service life of the power unit, years.

Labor and social insurance costs depend on the thermal power plant (TPP) staff size and the average annual wage level in the energy sector:

where

emp is the number of TPP personnel, persons;

is the average annual wage in the energy sector,

$;

α is the share of mandatory insurance contributions.

Repair and maintenance costs for generating equipment are estimated as a fraction of the power unit cost according to the expression:

where

β is the share of contributions to the repair fund.

Other costs represent expenses not included in the previously listed cost items and can be estimated as a portion of fixed costs:

where

γ is the share of other costs.

In turn, greenhouse gas emission costs are determined by the relation:

where

is the price per ton of CO

2 emissions,

$/t CO

2.

Evidently, the required annual electricity output can be achieved through an arbitrary combination of generating equipment. Thus, transitioning from the analysis of individual power units (or individual generation technologies) to the analysis of the entire energy system, the cost of producing 1 kWh is generally given by the expression:

where

n is the number of generation technologies in the system;

Qi is the annual electricity output from the

i-th generation technology, kWh.

Energy planning must account for observed trends in carbon allowance and fossil fuel markets. Accordingly, we conducted a time series analysis of wholesale natural gas prices regulated by the Federal Antimonopoly Service of Russia from January 2015 to August 2025, and carbon allowance prices in the European Union Emissions Trading System from January 2019 to April 2025 [

40]. The analysis yielded exponential and linear regression models with R

2 values of 0.84 and 0.61, respectively, demonstrating sufficient predictive capability for extrapolation and forecasting. These dependencies were integrated as arguments in Expression (9), transforming it into a time-dependent function:

where

is the vector of annual electricity outputs;

t is the time parameter, years;

Pfuel(

t) is the exponential regression equation approximating the natural gas price time series,

$/thousands m

3;

is the linear regression equation approximating the CO

2 emission price time series,

$/t CO

2.

The transition to relation (10) enables estimation of the average integrated production cost per 1 kWh for generation structure

Q, accounting for the power equipment’s useful service life

Tl:

where

t0 is the start of the modeling time period, years.

Thus, indicator (11) reflects the economic efficiency of the electric power generation structure throughout the entire operational lifespan of the generating equipment, enabling quantitative assessment of the energy system’s competitiveness at the design stage. All constant parameters involved in modeling the unit electricity production cost are presented in

Table 2.

In turn, the energy efficiency of a power system is manifested in the economical use of fuel and energy resources, while its environmental efficiency is determined by the extent of environmental damage. These optimality criteria can be described by the system’s characteristic indicators of reference fuel consumption and greenhouse gas emissions, respectively.

Another important optimality criterion for the electric power generation structure is the total construction cost of new generating facilities. Indeed, given equal energy, environmental, and economic efficiency, the system requiring the lowest initial investment is preferable. A lower initial capital investment at the project’s inception enhances the probability of its payback and reduces potential losses in case of failure. The total funds required for constructing new generating capacity are determined by the specific capital cost per unit of installed capacity of the power units comprising the energy system.

Note that different energy systems exhibit varying electricity production requirements. To eliminate these differences, the total annual electricity output of the energy system is normalized to a dimensionless quantity equal to 1. This normalization makes it unnecessary to consider limitations related to fluctuations in energy demand and the requirement for capacity expansion to maintain system reliability. Simultaneously, this approach does not hinder the analysis of specific energy systems. Under this assumption, the selected optimality criteria for the energy system can be described by the expressions presented in

Table 3.

Energy planning must account for natural constraints on the decision variables of the criterion functions presented in

Table 3. Specifically, the annual electricity output

Qi for individual generation technologies is by definition non-negative, while the total annual electricity output of the system remains constant across all possible generation structures. Furthermore, given current global trends in energy efficiency and decarbonization, the prospective energy system must comply with established limits on hydrocarbon fuel consumption and atmospheric greenhouse gas emissions.

Given the normalization of the total annual electricity output (

Q) and a fixed commissioning date for the generating equipment (

t0), the multi-objective optimization problem for the electric power generation structure can be formulated as follows:

where

bmax is the maximum permissible specific fuel consumption in the energy system, g of equivalent fuel/kWh;

GCO2,max is the maximum permissible specific CO

2 emissions in the energy system, g CO

2/kWh.

In multi-objective optimization, the first essential step involves testing the selected optimality criteria for redundancy [

41]. It is known that a large number of strongly correlated objectives in an optimization problem leads to excessive focus on non-conflicting alternatives. Consequently, decision-making with redundant criteria causes repeated implicit accounting of the same performance indicator, resulting in non-representative optimization outcomes. To identify redundant optimality criteria, this study employs an objective reduction algorithm based on principal component analysis (PCA). This statistical tool transforms a set of correlated criteria into uncorrelated variables called principal components, while retaining the largest share of the original variance and information [

42]. Subsequently, by analyzing the contributions (loadings) of the original objectives to the principal components, the most significant (alternative) optimality criteria are identified, which are then used for optimization. The detailed steps of the implemented objective reduction algorithm can be presented as follows:

Define the feasible decision space for the multi-objective optimization problem. Initialize the set of original objectives and the set of alternative objectives

Compute the correlation matrix RF of the original objectives.

Determine the eigenvectors (x) and eigenvalues (λ) of the correlation matrix RF.

Arrange the eigenvectors in descending order of their eigenvalues. Assign the eigenvectors to principal components such that the first eigenvector corresponds to the first principal component, the second eigenvector to the second principal component, and so on.

Calculate the proportion of total variance

TV explained by the first

k principal components:

where

m is the number of original objectives,

k ≤

m.

Retain the minimal subset of principal components with cumulative variance above 0.95.

Add to

F0 the criteria

Fh and

Fl with the largest positive and largest negative contributions to the eigenvector of the first principal component, respectively, where:

For the remaining principal components, add to F0 the criterion with the maximum absolute contribution value.

If , stop. Otherwise, compute the correlation matrix of the alternative objectives

If there exists a subset of alternative criteria with identical correlation coefficients to other objectives and positive pairwise correlations, retain from this subset the alternative criterion selected first.

The feasible decision space for the formulated problem was constructed using grid sampling with the following parameters: cell size—0.01, grid pattern—square lattice, sampling method—nodal point selection, initial sample size—5027 elements. This procedure generated a set of unique vectors Q through element-wise variation in their components Qi ranging from 0 to 1 with a step size of 0.01. Subsequently, vectors violating the constraints of system (12) were eliminated, thereby reducing the number of viable generation structures to 2346, which constitute the final feasible decision space for the optimization problem.

The primary method for solving optimization problems with multiple conflicting objectives is Pareto optimization, which yields a set of non-dominated solutions known as the Pareto front [

43]. A solution is considered non-dominated if no alternative exists that is not inferior in all optimality criteria and superior in at least one of them. However, the main limitation of this approach lies in the ambiguity of the obtained results. The Pareto-optimal set typically contains numerous compromised solutions, whereas practical applications often require selecting a single specific alternative.

To address this limitation, mathematical frameworks from multi-criteria decision-making theory are employed to identify a single “most efficient” solution from the set of non-dominated alternatives. One of the most universal and effective tools in this domain is the Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) [

44]. The implementation steps of the TOPSIS method can be outlined as follows:

The entropy weighting method (EWM) was employed to assess the relative importance of energy system performance indicators. This approach is based on calculating the informational entropy (a measure of uncertainty) for each optimality criterion included in the analysis. The method involves the objective assignment of weights to optimality criteria solely based on the information contained in the decision matrix. Criteria with lower uncertainty thus contain more useful information and are consequently assigned higher weights [

45].

The choice of optimal electric power generation structure evidently depends on the commissioning date of the generating equipment. This dependence arises primarily from the dynamics of natural gas prices and carbon prices, which determine temporal fluctuations in the unit electricity production cost. Secondly, extending the energy planning horizon typically involves tightening requirements for environmental safety and fuel efficiency of the power system. This alters the set of its possible configurations, thereby modifying the feasible decision space of the optimization problem.

Conducting multi-objective optimization of the electric power generation structure across different time intervals enables tracking changes in the optimal generating equipment composition within the energy system, thus identifying a priority pathway for sustainable energy development.

To solve the formulated problem, the following requirements for the energy and environmental efficiency of the prospective generation structure were adopted: the maximum permissible specific fuel consumption in the energy system

bmax was set as a constant, time-invariant value equal to 280 g of equivalent fuel/kWh; conversely, the maximum permissible specific CO

2 emissions in the energy system (g CO

2/kWh) is established according to the formula:

Implemented using the Python programming language version 3.12, the algorithm of the proposed multi-objective approach for determining the optimal electric power generation structure amid the development of advanced natural gas-fired energy complexes is presented in

Figure 5.

4. Results and Discussion

Correlation analysis of energy system performance indicators across all modeled time intervals revealed a strong positive relationship between electricity production cost and CO

2 emission criteria. The correlation analysis results for the generating equipment commissioning date of 2025 are presented in

Table 4.

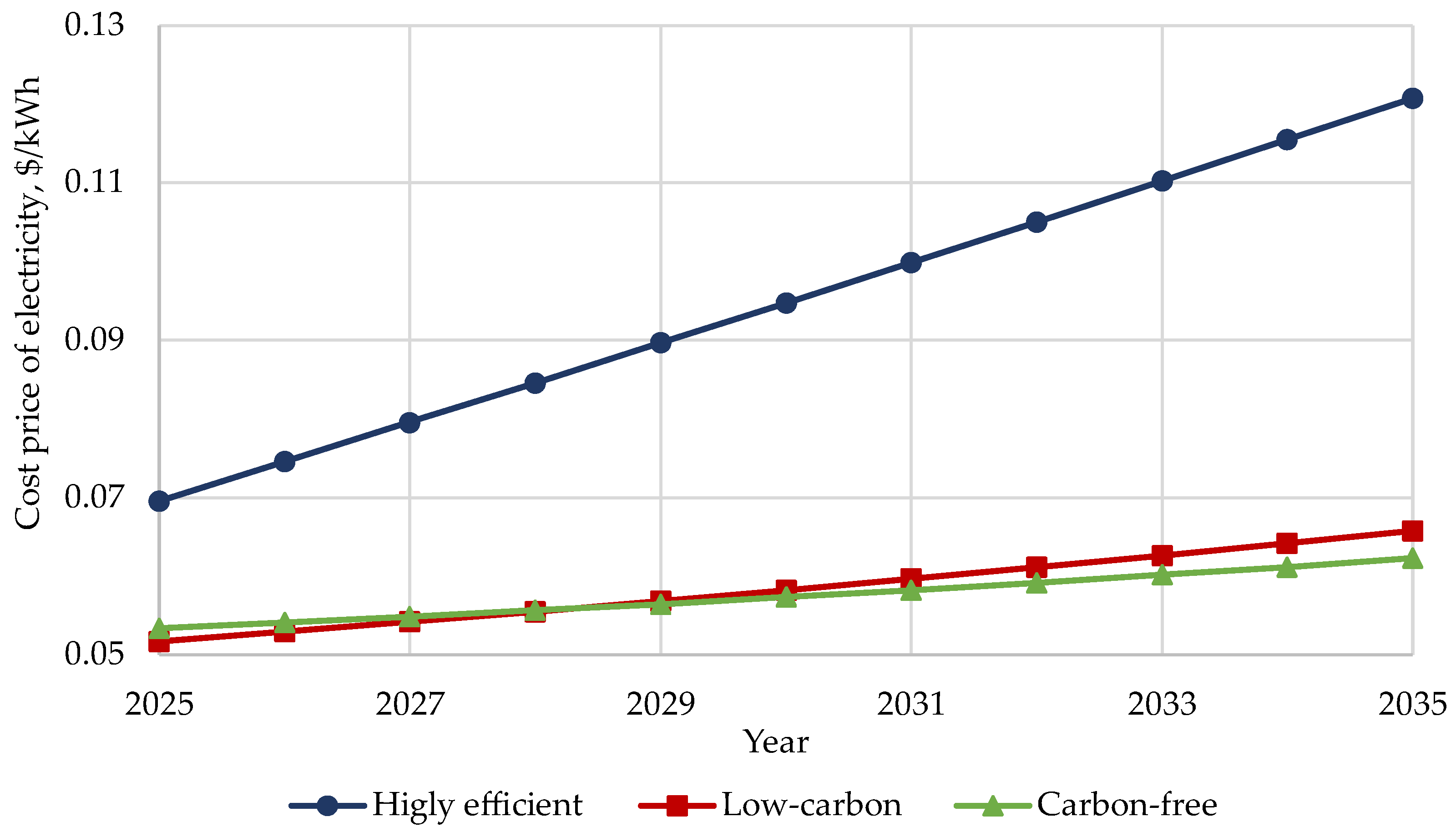

This strong direct correlation is attributed to the high projected carbon allowance prices in the EU ETS. The observed growth rate of CO

2 emission costs has a more substantial impact on energy production costs than the dynamics of hydrocarbon fuel prices in the Russian Federation, making carbon intensity the primary cost driver that overshadows the fuel efficiency of power units. Consequently, energy systems with the lowest cost of electricity predominantly consist of low-carbon and carbon-free energy complexes characterized by minimal specific CO

2 emission intensity. This conclusion is supported by the time-dependent specific electricity cost functions derived from Equation (10) for energy systems comprising individual advanced natural gas-fired generation technologies (highly efficient, low-carbon, or carbon-free). The modeling results are presented in

Figure 6.

An objective reduction algorithm based on principal component analysis was implemented to eliminate redundant criteria from further optimization. The results of the principal component analysis for energy system commissioning in 2025 are presented in

Table 5.

The presented estimates indicate that the first two principal components explain nearly all data variance, allowing the exclusion of objective loadings on the remaining components from further analysis. Analysis of loadings on the first principal component (explaining 87.3% of total variance) reveals that objectives c and GCO2 exhibit similar positive contributions, while objectives b and capex show comparable negative contributions. However, objectives c and capex demonstrate substantially stronger influence. Meanwhile, objective b displays the strongest association with the second principal component. Nevertheless, due to the positive correlation between objective b and capex, along with their similar correlation patterns with objective c, the objective reduction methodology excluded objective b from subsequent analysis.

Thus, two alternative objectives were selected for the multi-objective optimization of the electric power generation structure: electricity cost and capital cost of generation technology, thereby avoiding redundant objectives and enhancing the representativeness of modeling results. These optimality criteria are conflicting. Indeed, as shown earlier, under high carbon prices, generation structures with lower electricity costs predominantly consist of low-carbon energy complexes characterized by higher capital costs. Consequently, improving the economic efficiency of the energy system increases initial investments and operational expenses, thereby elevating project viability risks.

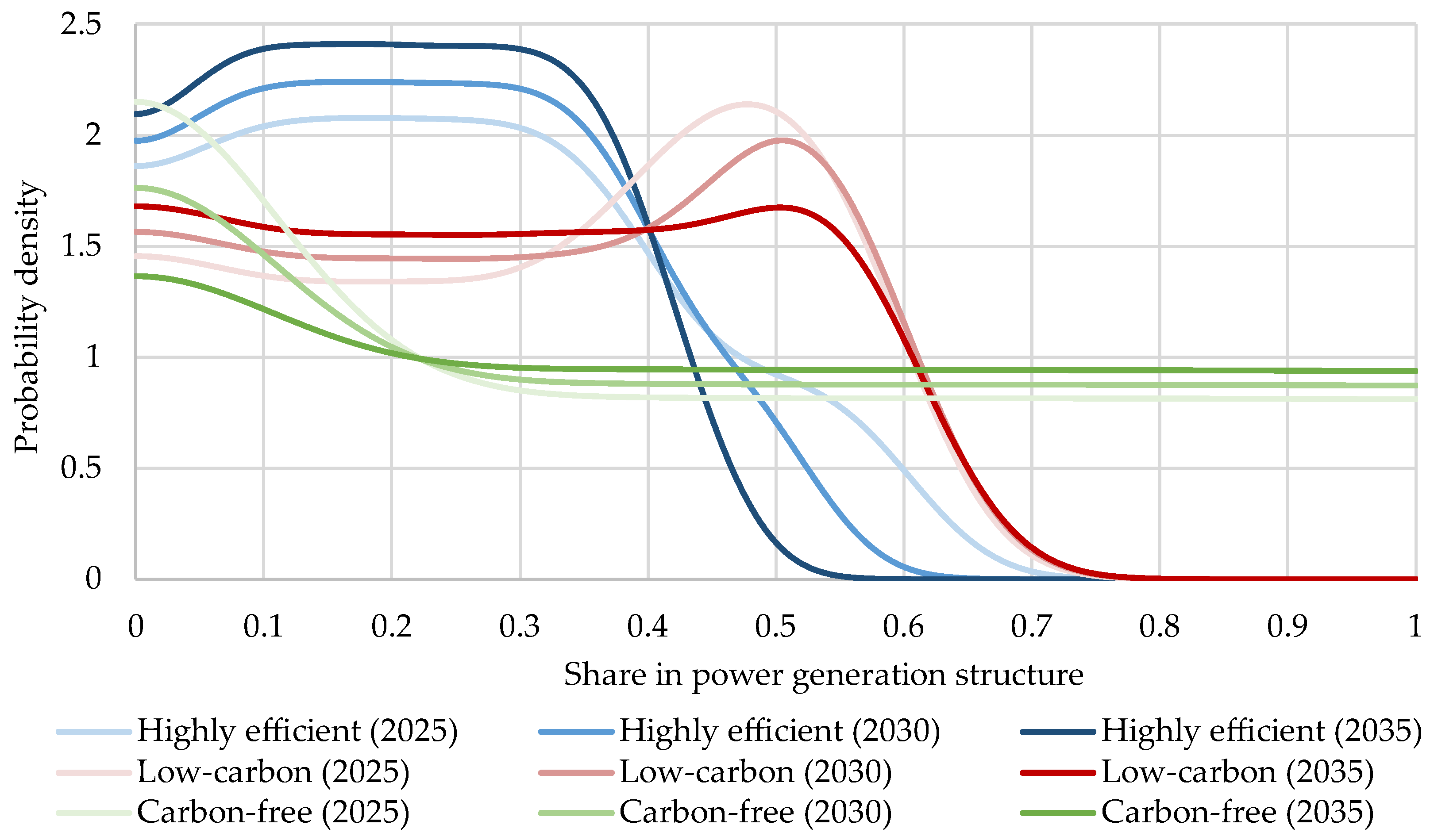

The Pareto-optimal electric power generation structures were identified using a non-dominated sorting procedure that searches for non-dominated solutions across the discrete feasible decision space of the optimization problem. Since the problem’s feasible decision space is explicitly defined as a low-dimensional discrete set, this approach was selected over the widely used NSGA-II genetic algorithm due to its superior computational efficiency and enhanced reliability in obtaining Pareto-optimal solutions. The distribution density analysis of advanced energy complex shares in Pareto-optimal systems revealed the evolution of non-dominated alternatives across different time intervals (

Figure 7).

Figure 7 reveals that in Pareto-optimal systems, the share of highly efficient energy complexes rarely exceeds 40% of total generating capacity, with this trend becoming more pronounced as the energy planning horizon extends. Meanwhile, low-carbon power plants in non-dominated generation structures typically occupy no more than 60%, whereas carbon-free technologies demonstrate a more uniform distribution across the capacity spectrum.

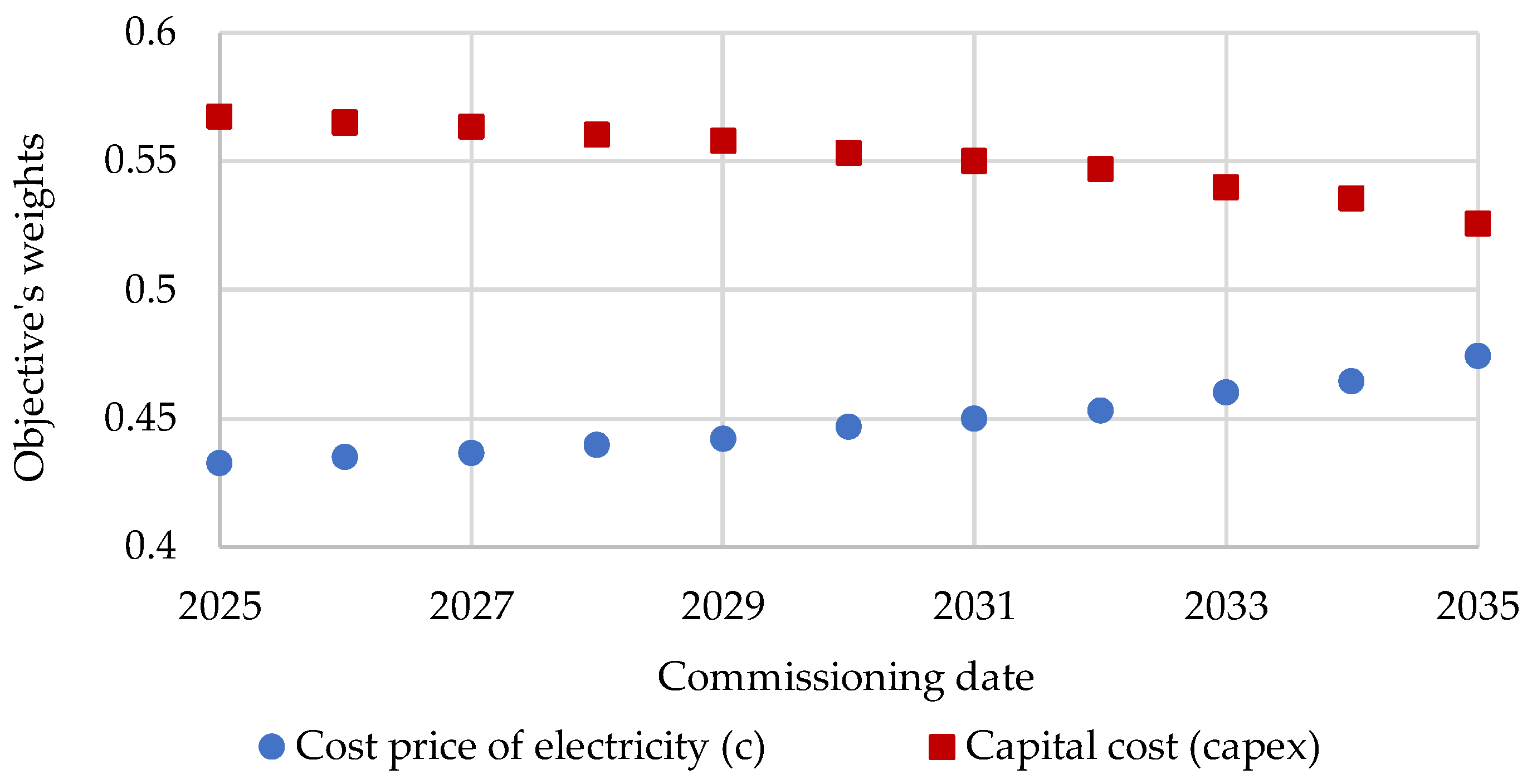

Based on the obtained Pareto-optimal sets, the entropy weighted method was applied to assess the relative importance of energy system performance indicators for each modeled time interval. The dependence of objective weights on generating equipment commissioning date is presented in

Figure 8.

The presented results indicate that the capital cost (capex) objective demonstrates higher relative importance compared to the electricity cost (c) objective. This suggests that Pareto-optimal alternatives exhibit closer values in terms of electricity cost, thereby providing less discriminative information for distinguishing between solutions. In contrast, non-dominated alternatives show greater variation in capital cost values. Consequently, this objective carries higher informational value and proves more significant for subsequent ranking within the TOPSIS methodology implementation.

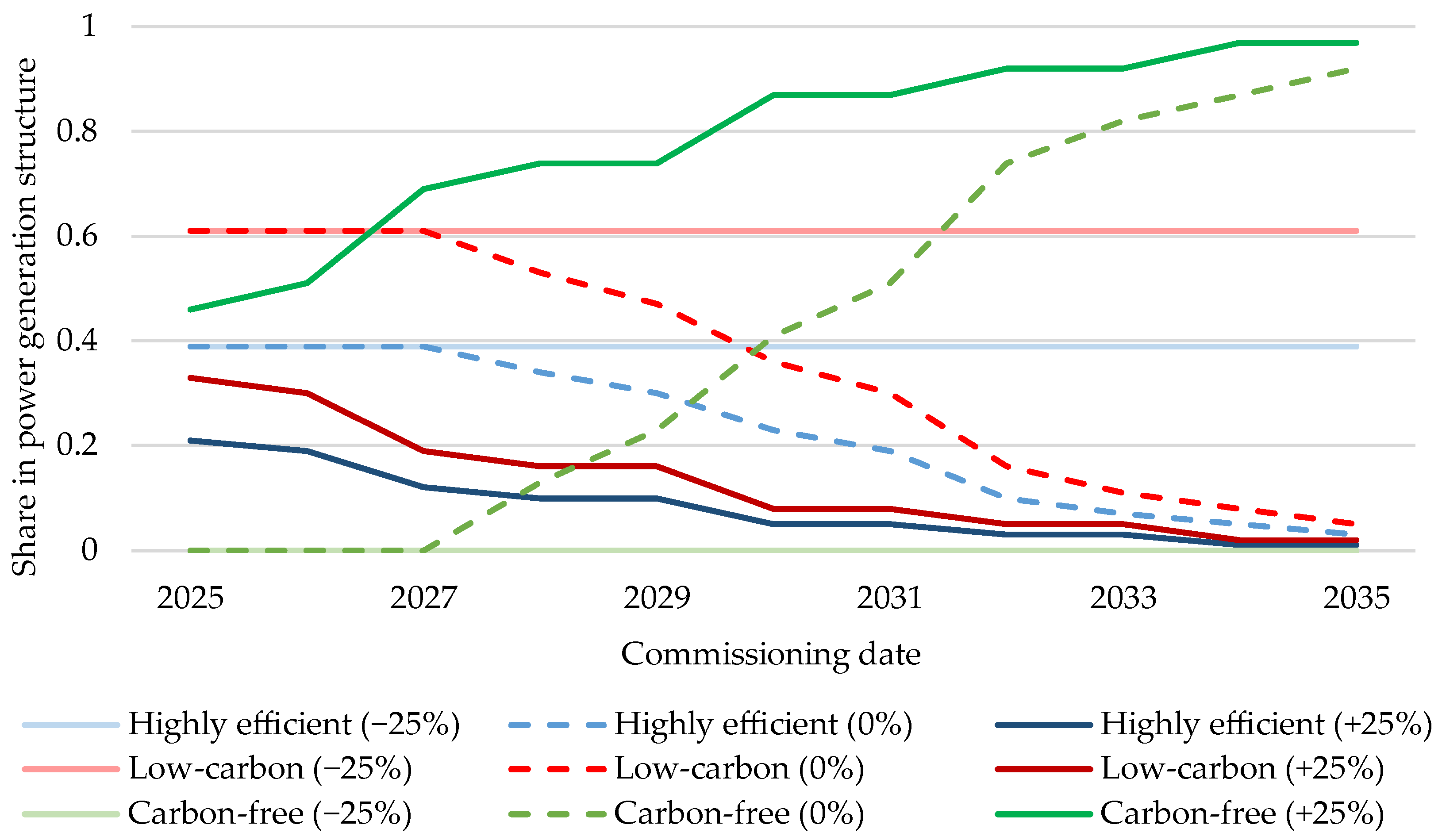

By ranking the identified Pareto-optimal energy systems according to their closeness to the ideal (best) solution and distance from the negative-ideal (worst) solution, the most efficient electric power generation structure was determined for each modeled time interval. The results of applying the TOPSIS method to the Pareto set of non-dominated generation structures are presented in

Figure 9.

The graph indicates that extending the energy planning horizon increases the share of carbon-free generation technologies in the most efficient energy systems. For generating equipment commissioned in 2031, it becomes feasible to source over half of the electricity output from carbon-free power plants, while a 2035 commissioning date raises their recommended share to 92%.

To assess the influence of price factors on the optimal electric power generation structure, we conducted a sensitivity analysis of the modeling results to key input parameters of the economic-mathematical model, specifically natural gas prices (

Pfuel) and CO

2 emission costs (

PCO2). The sensitivity analysis results for natural gas prices are presented in

Figure 10.

The graph indicates that a 25% increase in energy carrier prices reduces the share of carbon-free energy complexes in the optimal generation structure by an average of 17.5%. This results from the enhanced economic competitiveness of highly efficient generation technologies with superior electrical efficiency, which displaces some environmentally friendly power units. However, the analysis also reveals that rising natural gas prices increase the proportion of low-carbon power plants in the optimal configuration (by an average of 20%), despite their inherent lower fuel efficiency. This suggests that under the model’s constraints, low-carbon generation technologies are more advantageous to deploy in conjunction with highly efficient power units than carbon-free alternatives, as they feature significantly lower capital costs per unit of installed capacity while maintaining comparable electricity production costs.

Thus, under observed carbon market dynamics, low-carbon generation technologies can serve as a transitional solution toward the complete decarbonization of the energy sector. Their inclusion in the energy production structure enables a phased transition to carbon-free generation technologies without compromising economic efficiency or energy system security, which aligns with previous research findings [

30,

33].

Conversely, the sensitivity analysis of modeling results to changes in CO

2 emission prices demonstrated opposite trends, as presented in

Figure 11.

The graph demonstrates that a 25% increase in carbon prices leads to a rise in the share of carbon-free energy complexes within the optimal generation structure, averaging 36.6%. Conversely, a 25% reduction in carbon allowance prices makes carbon-free generation technologies suboptimal across the entire energy planning horizon. Moreover, these changes exhibit a rapid nature. For instance, merely a 5% carbon price increase raises the share of carbon-free technologies in the optimal generation structure by an average of 10%, while an equivalent price reduction leads to the displacement of environmentally friendly power units by an average of 9%. Meanwhile, a 15% carbon price increase raises carbon-free generating capacity in the optimal generation structure by 26%, while a 15% carbon price reduction decreases it by 30%.

Thus, the effectiveness of clean power generation technologies is closely linked to the presence of functioning carbon pricing instruments in a given region. Furthermore, the economic viability of deploying carbon-free technologies is directly determined by the price per ton of atmospheric carbon dioxide emissions.

The comparative analysis of

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 demonstrates that, under the observed price dynamics, CO

2 price volatility has a stronger impact on the optimal energy equipment composition than hydrocarbon fuel price fluctuations. Specifically, natural gas price variations shift the optimal generation share curves toward earlier or later timeframes, whereas carbon allowance price changes can fundamentally transform the energy transition trajectory. Consequently, carbon pricing emerges as the primary policy instrument for incentivizing the transition to carbon-free natural gas-fired power plants.