From Access to Impact: How Digital Financial Inclusion Drives Sustainable Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

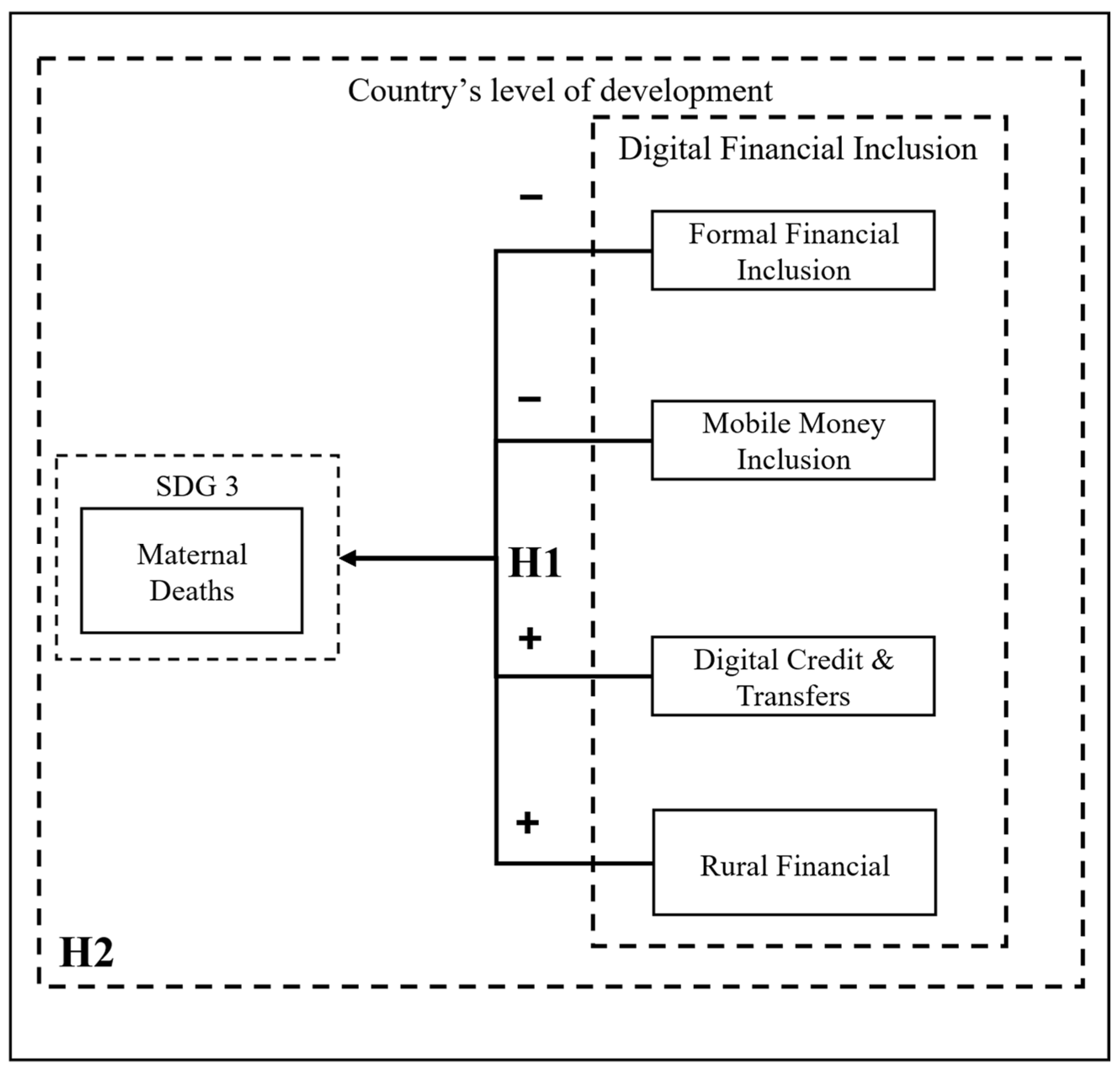

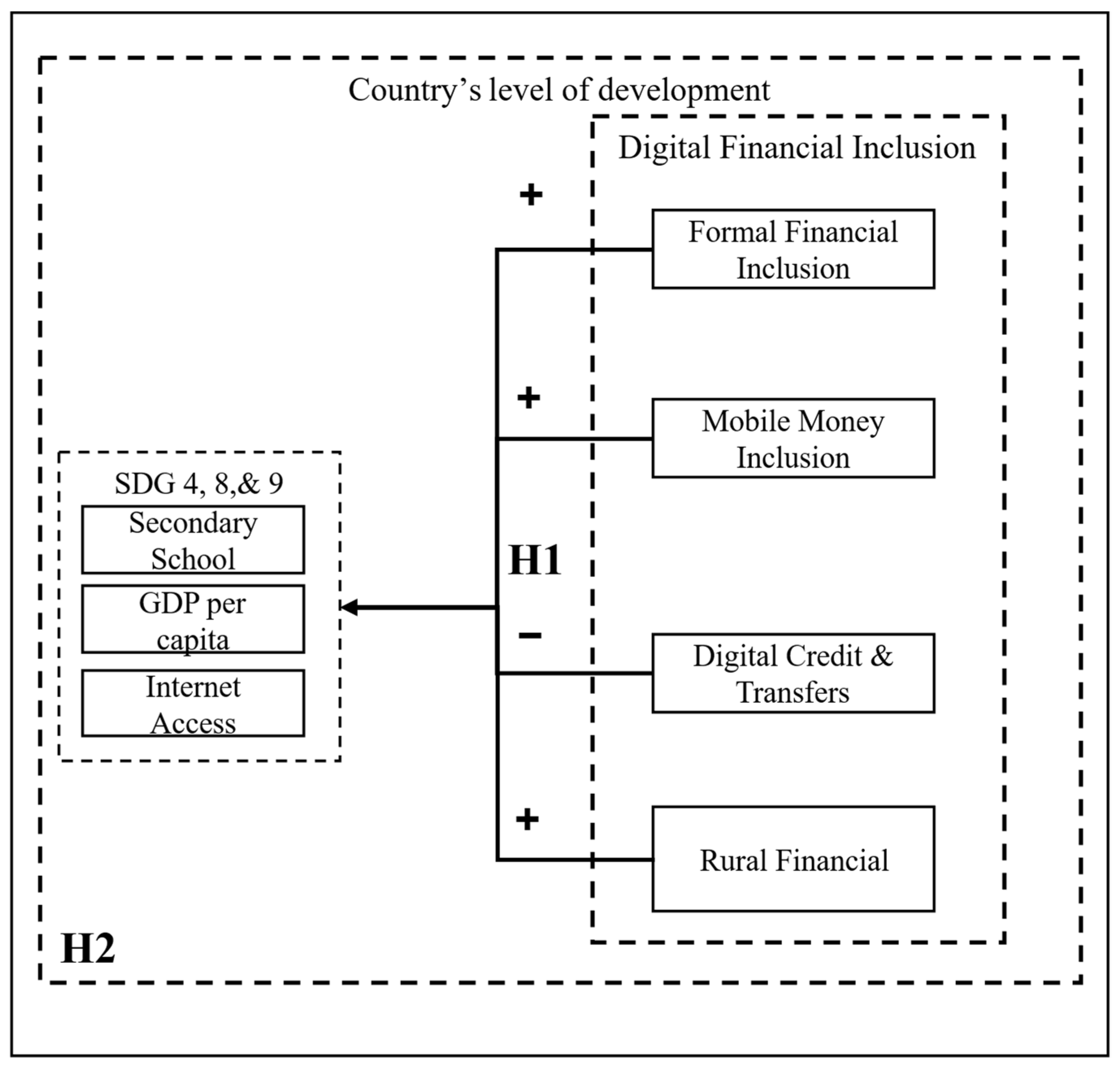

2. Theoretical Framework

3. Method

3.1. Sample and Data Sources

3.2. Variable Design

3.2.1. Dependent Variables

3.2.2. Explanatory Variables

3.2.3. Control Variables

3.2.4. Descriptive Statistics

3.3. Empirical Model

4. Results and Discussions

5. Robustness Tests

5.1. Income Analysis

5.2. Simultaneous Equation Model

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Countries

| Income Level Classification | Country | SWIID (Last Reported) | Country | SWIID (Last Reported) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Income | Australia | 34.4 | Netherlands | 25.7 |

| Austria | 30.8 | Poland | 28.5 | |

| Belgium | 26.6 | Portugal | 34.6 | |

| Canada | 33.2 | Slovak Rep. | 24.1 | |

| Chile | 46.36 | Slovenia | 24.3 | |

| Czechia | 26.2 | Spain | 33.9 | |

| Denmark | 28.3 | Sweden | 29.8 | |

| Estonia | 31.8 | Switzerland | 32.43 | |

| Finland | 27.7 | United Kingdom | 32.4 | |

| Germany | 30.7 | USA | 39.7 | |

| Greece | 32.9 | Bulgaria | 39 | |

| Hungary | 29.2 | Croatia | 28.9 | |

| Iceland | 28.4 | Romania | 33.9 | |

| Ireland | 30.1 | Cyprus | 31.3 | |

| Israel | 37.9 | Malta | 28.9 | |

| Italy | 34.8 | Norway | 26.7 | |

| Japan | 32.9 | Panama | 50.9 | |

| South Korea | 32.9 | Qatar | 35.1 | |

| Latvia | 34.3 | Russia | 35.1 | |

| Lithuania | 36.7 | Trinidad and Tobago | 0 | |

| Luxembourg | 32.7 | UAE | 36.5 | |

| Uruguay | 40.8 | |||

| Total | 43 | |||

| Upper-Middle Income | Colombia | 55.1 | El Salvador | 39 |

| Costa Rica | 48.7 | Gabon | 38 | |

| Mexico | 43.5 | Georgia | 34.2 | |

| Türkiye | 44.4 | Guatemala | 48.3 | |

| Argentina | 42.4 | Iran | 35.5 | |

| Brazil | 52.9 | Iraq | 29.5 | |

| Indonesia | 35.5 | Jamaica | 40.2 | |

| Peru | 40.1 | Kazakhstan | 29.2 | |

| Thailand | 34.9 | Kosovo | 26,7 | |

| Albania | 35.1 | Malaysia | 40.7 | |

| Algeria | 27.6 | Maldives | 31.3 | |

| Armenia | 27.9 | Mauritius | 36.8 | |

| Azerbaijan | 0 | Moldova | 25.7 | |

| Belarus | 27.8 | Mongolia | 31.4 | |

| Belize | 0 | Montenegro | 34.3 | |

| Bosnia and Herz. | 33 | Namibia | 59.1 | |

| Botswana | 53.3 | North Macedonia | 35.5 | |

| China | 35.7 | Paraguay | 42.9 | |

| Dominican Republic | 38.5 | Serbia | 33.1 | |

| Ecuador | 45.8 | South Africa | 63 | |

| Turkmenistan | 0 | |||

| Ukraine | 23.3 | |||

| Total | 42 | |||

| Lower Middle Income | Angola | 51.3 | Lebanon | 31.8 |

| Bangladesh | 33.4 | Lesotho | 44.9 | |

| Benin | 34.4 | Mauritania | 32.6 | |

| Bhutan | 37.4 | Morocco | 39.5 | |

| Bolivia | 40.4 | Myanmar | 30.7 | |

| Cameroon | 42.2 | Nepal | 30 | |

| Comoros | 45.3 | Nicaragua | 46.2 | |

| Rep. Congo | 48.9 | Nigeria | 35.1 | |

| Cote d’Ivoire | 35.3 | Pakistan | 31.8 | |

| Djibouti | 41.6 | Philippines | 40.7 | |

| Egypt | 31.5 | Senegal | 36.2 | |

| Eswatini | 54.6 | Sri Lanka | 40.2 | |

| Ghana | 46.1 | Tajikistan | 34 | |

| Guinea | 32.33 | Tanzania | 37.8 | |

| Haiti | 41.1 | Tunisia | 33.7 | |

| Honduras | 50.1 | Uzbekistan | 31.2 | |

| India | 32.8 | Vietnam | 36.1 | |

| Jordan | 33.7 | West Bank and Gaza | 32.1 | |

| Kenya | 38.7 | Zambia | 51.5 | |

| Kyrgyz | 28.8 | Zimbabwe | 43.5 | |

| Lao PDR | 36.9 | |||

| Total | 41 | |||

| Low Income | Burkina Faso | 37.4 | Niger | 32.9 |

| Burundi | 38.2 | Rwanda | 40.4 | |

| Central African R. | 43 | Sierra Leone | 34 | |

| Chad | 37.4 | South Sudan | 44.1 | |

| Dem. Rep. Congo | 42.9 | Sudan | 34.2 | |

| Ethiopia | 35 | Syrian A.R. | 26.6 | |

| Gambia | 34.9 | Togo | 37.9 | |

| Liberia | 33.2 | Uganda | 42.8 | |

| Madagascar | 42.6 | Yemen | 36.7 | |

| Malawi | 46.7 | |||

| Mali | 35.7 | |||

| Mozambique | 55.2 | |||

| Total | 21 |

Appendix A.2. Income Analysis

| Variables | SDG 3 | SDG 4 | SDG 8 | SDG 9 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formal Financial Access (Index) | −0.060 | (0.081) | 0.189 ** | (0.085) | −0.025 | (0.054) | 0.369 *** | (0.054) |

| Mobile Money (Index) | 0.020 | (0.064) | −0.087 | (0.067) | −0.071 * | (0.042) | 0.078 * | (0.043) |

| Digital Credit & Transfers (Index) | 0.057 | (0.08) | −0.023 | (0.084) | 0.139 ** | (0.053) | 0.111 ** | (0.054) |

| Rural Finance (Index) | −0.024 | (0.066) | 0.006 | (0.069) | −0.053 | (0.044) | 0.138 *** | (0.044) |

| Inequality | 0.10 *** | (0.018) | −0.025 | (0.019) | −0.008 | (0.012) | −0.038 *** | (0.012) |

| Trade | 0.21 *** | (0.082) | 0.075 | (0.086) | 0.157 *** | (0.055) | 0.021 | (0.055) |

| Urbanisation | −0.059 | (0.081) | 0.139 | (0.085) | 0.096 * | (0.054) | 0.135 ** | (0.055) |

| Population Growth | −0.007 | (0.07) | −0.065 | (0.073) | 0.100 ** | (0.046) | 0.098 ** | (0.047) |

| Government Expenditure | −0.110 | (0.111) | 0.196 * | (0.116) | −0.119 | (0.074) | 0.064 | (0.075) |

| Water Facility | 0.093 | (0.066) | −0.020 | (0.069) | 0.008 | (0.044) | 0.028 | (0.044) |

| Health Expenditure | 0.27 *** | (0.105) | −0.079 | (0.111) | 0.134 * | (0.07) | 0.002 | (0.071) |

| GDP growth | 0.096 | (0.082) | 0.013 | (0.086) | 0.009 | (0.055) | 0.120 ** | (0.055) |

| Voice and Accountability | 0.012 | (0.11) | 0.39 *** | (0.116) | −0.256 *** | (0.073) | −0.342 *** | (0.074) |

| Government Effectiveness | −0.007 | (0.21) | −0.50 ** | (0.22) | 0.441 *** | (0.139) | 0.168 | (0.141) |

| Regulator Quality | −0.181 | (0.176) | −0.241 | (0.185) | −0.319 *** | (0.117) | −0.036 | (0.118) |

| Rule of Law | 0.158 | (0.298) | 0.150 | (0.313) | 0.493 ** | (0.198) | 0.302 | (0.201) |

| Political Stability | 0.143 | (0.097) | −0.151 | (0.102) | −0.119 * | (0.064) | 0.053 | (0.065) |

| Corruption Control | −0.273 | (0.209) | 0.348 | (0.22) | 0.326 ** | (0.139) | 0.102 | (0.141) |

| Constant | −3.52 *** | (0.589) | 0.871 | (0.619) | 0.237 | (0.392) | 1.236 *** | (0.397) |

| Observations | 172 | 172 | 172 | 172 | ||||

| R2 | 0.3688 | 0.2243 | 0.7569 | 0.7457 | ||||

| Variables | SDG3 | SDG4 | SDG8 | SDG9 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formal Financial Access (Index) | −0.198 *** | (0.069) | −0.001 | (0.09) | 0.081 | (0.087) | 0.253 *** | (0.072) |

| Mobile Money (Index) | 0.141 ** | (0.066) | 0.012 | (0.087) | −0.233 *** | (0.084) *** | 0.152 ** | (0.069) |

| Digital Credit & Transfers (Index) | 0.159 ** | (0.073) | −0.080 | (0.095) | 0.101 | (0.092) | 0.011 | (0.076) |

| Rural Finance (Index) | 0.022 | (0.059) | 0.100 | (0.077) | −0.024 | (0.074) | 0.139 ** | (0.061) |

| Inequality | 0.010 *** | (0.005) | −0.011 * | (0.007) | −0.007 | (0.006) | −0.023 *** | (0.005) |

| Trade | −0.215 *** | (0.061) | 0.023 | (0.079) | −0.091 | (0.076) | −0.075 | (0.063) |

| Urbanisation | 0.084 | (0.058) | 0.311 *** | (0.076) | 0.369 *** | (0.074) | 0.357 *** | (0.061) |

| Population Growth | 0.462 *** | (0.059) | −0.377 *** | (0.077) | 0.360 *** | (0.075) | −0.137 ** | (0.061) |

| Government Expenditure | 0.217 *** | (0.069) | −0.321 *** | (0.09) | −0.115 | (0.087) | −0.024 | (0.072) |

| Water Facility | 0.306 ** | (0.054) | 0.067 | (0.071) | −0.140 ** | (0.068) | 0.064 | (0.056) |

| Health Expenditure | −0.186 ** | (0.073) | 0.240 ** | (0.095) | 0.361 *** | (0.092) | 0.394 *** | (0.075) |

| GDP growth | 0.138 *** | (0.053) | −0.132 * | (0.069) | −0.037 | (0.067) | 0.064 | (0.055) |

| Voice and Accountability | 0.452 *** | (0.08) | 0.230 ** | (0.104) | −0.373 *** | (0.101) | −0.213 ** | (0.083) |

| Government Effectiveness | 0.131 | (0.097) | 0.268 ** | (0.126) | 0.161 | (0.122) | 0.041 | (0.101) |

| Regulator Quality | 0.033 | (0.111) | −0.003 | (0.144) | 0.073 | (0.14) | 0.445 *** | (0.115) |

| Rule of Law | 0.051 | (0.14) | −0.040 | (0.183) | 0.523 *** | (0.177) | 0.076 | (0.146) |

| Political Stability | −0.040 | (0.067) | −0.144 | (0.087) | 0.117 | (0.085) | −0.027 | (0.07) |

| Corruption Control | −0.246 ** | (0.098) | −0.051 | (0.127) | −0.151 | (0.123) | −0.149 | (0.101) |

| Constant | −0.377 ** | (0.189) | 0.411 * | (0.247) | 0.256 | (0.239) | 0.842 *** | (0.197) |

| Observations | 168 | 168 | 168 | 168 | ||||

| R2 | 0.6456 | 0.3982 | 0.436 | 0.6174 | ||||

| Variables | SDG3 | SDG4 | SDG8 | SDG9 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formal Financial Access (Index) | −0.115 | (0.074) | 0.152 ** | (0.08) | 0.178 *** | (0.065) | 0.271 *** | (0.07) |

| Mobile Money (Index) | 0.036 | (0.069) | −0.161 ** | (0.075) | −0.058 | (0.061) | 0.103 | (0.065) |

| Digital Credit & Transfers (Index) | 0.147 * | (0.087) | −0.053 | (0.095) | −0.009 | (0.077) | −0.069 | (0.083) |

| Rural Finance (Index) | −0.047 | (0.068) | 0.092 | (0.074) | 0.044 | (0.06) | 0.283 *** | (0.064) |

| Inequality | 0.021 ** | (0.01) | −0.022 ** | (0.011) | 0.039 *** | (0.009) | −0.026 *** | (0.01) |

| Trade | 0.045 | (0.078) | −0.316 *** | (0.085) | −0.070 | (0.069) | −0.048 | (0.074) |

| Urbanisation | −0.033 | (0.069) | −0.073 | (0.075) | 0.534 *** | (0.06) | 0.384 *** | (0.065) |

| Population Growth | −0.005 | (0.064) | 0.083 | (0.07) | −0.110 * | (0.057) | −0.137 ** | (0.061) |

| Government Expenditure | 0.005 | (0.087) | 0.213 ** | (0.094) | −0.151 * | (0.076) | 0.039 | (0.082) |

| Water Facility | −0.373 *** | (0.075) | 0.378 *** | (0.082) | 0.074 | (0.066) | 0.175 ** | (0.071) |

| Health Expenditure | −0.264 *** | (0.077) | −0.051 | (0.084) | 0.129 * | (0.068) | 0.166 ** | (0.073) |

| GDP growth | 0.003 | (0.065) | 0.145 ** | (0.071) | −0.056 | (0.057) | −0.109 * | (0.061) |

| Voice and Accountability | 0.320 *** | (0.072) | −0.063 | (0.079) | −0.219 *** | (0.063) | −0.127 * | (0.068) |

| Government Effectiveness | −0.213 * | (0.108) | 0.194 | (0.118) | 0.409 *** | (0.095) | 0.149 | (0.102) |

| Regulator Quality | −0.172 * | (0.098) | 0.295 *** | (0.107) | −0.172 ** | (0.087) | 0.131 | (0.093) |

| Rule of Law | −0.136 | (0.143) | −0.446 *** | (0.156) | 0.343 *** | (0.126) | −0.109 | (0.135) |

| Political Stability | −0.123 | (0.079) | 0.181 ** | (0.086) | −0.154 ** | (0.069) | 0.102 | (0.074) |

| Corruption Control | 0.279 ** | (0.122) | 0.285 ** | (0.133) | −0.109 | (0.108) | 0.017 | (0.115) |

| Constant | −0.831 ** | (0.397) | 0.836 ** | (0.433) | −1.516 *** | (0.35) | 1.019 *** | (0.375) |

| Observations | 164 | 164 | 164 | 164 | ||||

| R2 | 0.5287 | 0.4393 | 0.6343 | 0.5793 | ||||

| Variables | SDG3 | SDG4 | SDG8 | SDG9 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formal Financial Access (Index) | −0.127 | (0.095) | −0.137 | (0.129) | 0.054 | (0.104) | 0.324 | (0.106) *** |

| Mobile Money (Index) | 0.011 | (0.111) | −0.117 | (0.151) | −0.244 | (0.121) ** | 0.192 | (0.124) |

| Digital Credit & Transfers (Index) | 0.015 | (0.124) | 0.158 | (0.169) | 0.100 | (0.135) | −0.127 | (0.139) |

| Rural Finance (Index) | 0.012 | (0.143) | −0.253 | (0.195) | 0.054 | (0.156) | 0.019 | (0.161) |

| Inequality | −0.024 | (0.02) | 0.027 | (0.027) | −0.011 | (0.021) | −0.008 | (0.022) |

| Trade | −0.084 | (0.121) | 0.155 | (0.166) | 0.616 *** | (0.133) | 0.181 | (0.136) |

| Urbanisation | −0.164 | (0.13) | 0.136 | (0.178) | −0.102 | (0.142) | 0.337 ** | (0.146) |

| Population Growth | 0.049 | (0.099) | 0.234 * | (0.135) | −0.344 *** | (0.108) | −0.155 | (0.111) |

| Government Expenditure | −0.028 | (0.131) | −0.014 | (0.178) | −0.753 *** | (0.143) | −0.010 | (0.146) |

| Water Facility | −0.431 *** | (0.138) | 0.218 | (0.188) | 0.299 * | (0.151) | 0.238 | (0.155) |

| Health Expenditure | −0.183 | (0.124) | 0.178 | (0.169) | −0.065 | (0.135) | 0.069 | (0.138) |

| GDP growth | 0.025 | (0.094) | 0.169 | (0.129) | −0.035 | (0.103) | −0.059 | (0.106) |

| Voice and Accountability | 0.010 | (0.135) | 0.042 | (0.184) | −0.020 | (0.147) | 0.027 | (0.151) |

| Government Effectiveness | −0.944 *** | (0.285) | 0.045 | (0.389) | −0.517 | (0.311) | 0.323 | (0.319) |

| Regulator Quality | 0.373 * | (0.218) | −0.214 | (0.297) | 0.440 * | (0.238) | −0.330 | (0.244) |

| Rule of Law | −0.133 | (0.322) | 0.223 | (0.44) | 0.972 *** | (0.352) | 0.350 | (0.361) |

| Political Stability | 0.460 *** | (0.15) | 0.004 | (0.205) | −0.559 *** | (0.164) | −0.240 | (0.169) |

| Corruption Control | 0.413 ** | (0.18) | −0.022 | (0.246) | −0.147 | (0.197) | 0.032 | (0.202) |

| Constant | 0.942 | (0.767) | −1.056 | (1.047) | 0.446 | (0.838) | 0.324 | (0.86) |

| Observations | 84 | 84 | 84 | 84 | ||||

| R2 | 0.5165 | 0.1001 | 0.4234 | 0.3924 | ||||

Appendix A.3. Simultaneous Equation Model for SDGs

| (1) SDG3 | (2) FFA | (3) MMI | (4) DCT | (5) Rural FI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDG3 | −1.335 *** | (0.173) | 1.194 *** | (0.378) | −0.729 ** | (0.391) | 0.457 | (0.423) | ||

| FFA | −1.030 *** | (0.173) | ||||||||

| MMI | 0.122 ** | (0.047) | ||||||||

| DCT | −0.573 ** | (0.247) | ||||||||

| Rural FI | 0.202 | (0.375) | ||||||||

| Inequality | 0.177 *** | (0.35) | 0.257 *** | (0.076) | −0.193 | (0.103) | 0.248 | (0.114) | −0.009 | (0.12) |

| Trade | 0.015 | (0.045) | −0.017 | (0.044) | 0.073 | (0.052) | −0.089 | (0.061) | 0.098 | (0.063) |

| Urbanisation | −0.032 | (0.04) | 0.158 * | (0.088) | −0.224 ** | (0.108) | −0.096 | (0.093) | ||

| Population Growth | 0.119 *** | (0.04) | 0.191 ** | (0.078) | −0.181 ** | (0.086) | 0.108 | (0.099) | −0.058 | (0.102) |

| Government Expenditure | −0.102 ** | (0.049 | −0.100 * | (0.052) | 0.074 | (0.064) | −0.109 | (0.067) | −0.039 | (0.076) |

| Water Facility | −0.140 *** | (0.038) | −0.146 ** | (0.045) | 0.031 | (0.055) | −0.043 | (0.076) | 0.181 *** | (0.065) |

| Health Expenditure | −0.166 *** | (0.054) | ||||||||

| GDP growth | −0.031 | (0.036) | −0.020 | (0.04) | −0.151 *** | (0.051) | 0.108 | (0.099) | 0.059 | (0.062) |

| Voice and Accountability | 0.084 | (0.084) | 0.063 | (0.113) | −0.185 | (0.122) | 0.214 | (0.137) | ||

| Government Effectiveness | −0.126 | (0.133) | 0.311 | (0.23) | 0.261 | (0.2) | −0.102 | (0.273) | ||

| Regulator Quality | −0.071 | (0.085) | −0.132 | (0.155) | 0.126 | (0.126) | −0.176 | (0.19) | ||

| Rule of Law | −0.053 | (0.112) | 0.170 | (0.179) | 0.018 | (0.142) | −0.196 | (0.25) | ||

| Political Stability | −0.110 * | (0.065) | 0.153 * | (0.081) | 0.018 | (0.052) | −0.008 | (0.097) | ||

| Corruption Control | 0.263 ** | (0.118) | −0.136 | (0.131) | −0.044 | (0.094) | 0.416 ** | (0.168) | ||

| MMI_lag1 | 0.807 *** | (0.083) | ||||||||

| DCT_lag1 | 0.037 | (0.062) | ||||||||

| RuralFI_lag1 | −0.070 | (0.148) | ||||||||

| Constant | −1.011 | (0.092) | −0.205 | (0.187) | −2.234 *** | (0.237) | −1.279 | (0.23) | ||

| Observations | 589 | 581 | 443 | 443 | 443 | |||||

| R2 | 0.4217 | 0.2422 | 0.2759 | 0.1767 | 0.0650 | |||||

| (1) SDG4 | (2) FFA | (3) MMI | (4) DCT | (5) Rural FI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDG4 | −0.034 | (0.819) | −0.575 | (1.427) | −1.249 | (1.008) | 0.457 | (0.423) | ||

| FFA | 0.305 * | (0.175) | ||||||||

| MMI | −0.166 ** | (0.061) | ||||||||

| DCT | 0.211 | (0.243) | ||||||||

| Rural FI | 0.202 | 0.375 | ||||||||

| Inequality | −0.008 | (0.036) | −0.042 | (0.074) | 0.116 | (0.089) | 0.004 | (0.092) | −0.009 | (0.12) |

| Trade | 0.008 | (0.045) | 0.036 | (0.082) | −0.027 | (0.134) | −0.128 | (0.112) | 0.098 | (0.063) |

| Urbanisation | 0.159 | (0.077) | 0.108 | (0.19) | −0.066 | (0.176) | −0.096 | (0.093) | ||

| Population Growth | −0.160 *** | (0.04) | 0.015 | (0.149) | −0.080 | (0.177) | −0.133 | (0.155) | −0.058 | (0.102) |

| Government Expenditure | −0.028 | (0.049) | −0.012 | (0.092) | 0.018 | (0.111) | −0.025 | (0.106) | −0.039 | (0.076) |

| Water Facility | 0.283 | (0.127) | 0.131 | (0.237) | 0.084 | (0.191) | 0.181 *** | (0.065) | ||

| Health Expenditure | 0.224 ** | (0.087) | ||||||||

| GDP growth | −0.052 | (0.082) | −0.033 | (0.134) | 0.114 | (0.119) | 0.059 | (0.062) | ||

| Voice and Accountability | 0.326 | (0.163) | −0.205 | (0.286) | 0.509 *** | (0.192) | 0.214 | (0.137) | ||

| Government Effectiveness | 0.889 | (0.359) | −0.369 | (0.468) | 0.953 *** | (0.329) | −0.102 | (0.273) | ||

| Regulator Quality | 0.223 * | (0.124) | −0.532 | (0.37) | 0.865 ** | (0.305) | −0.176 | (0.19) | ||

| Rule of Law | −0.257 | (0.275) | 0.680 | (0.509) | −0.952 *** | (0.385) | −0.196 | (0.25) | ||

| Political Stability | −0.176 | (0.118) | 0.168 | (0.132) | −0.144 *** | (0.083) | −0.008 *** | (0.097) | ||

| Corruption Control | −0.478 | (0.214) | 0.267 | (0.208) | 0.203 *** | (0.147) | 0.416 *** | (0.168) | ||

| MMI_lag1 | 0.888 *** | (0.301) | ||||||||

| DCT_lag1 | −0.072 | (0.092) | ||||||||

| RuralFI_lag1 | −0.070 | (0.148) | ||||||||

| Constant | 0.234 | (0.167) | −0.911 | (0.183) | −0.347 | (0.44) | −2.193 *** | (0.326) | −1.279 | (0.23) |

| Observations | 589 | 581 | 443 | 443 | 443 | |||||

| R2 | 0.4087 | 0.4089 | 0.2662 | 0.4045 | 0.0650 | |||||

| (1) SDG8 | (2) FFA | (3) MMI | (4) DCT | (5) Rural FI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDG8 | 0.658 ** | (0.293) | −0.991 *** | (0.345) | 0.141 | (0.34) | 0.285 | (0.411) | ||

| FFA | 0.908 *** | (0.146) | ||||||||

| MMI | −0.006 | (0.032) | ||||||||

| DCT | 0.835 *** | (0.251) | ||||||||

| Rural FI | −0.577 | (0.44) | ||||||||

| Inequality | −0.026 | (0.03) | −0.009 | (0.043) | 0.026 | (0.052) | 0.064 | (0.056) | 0.150 | (0.064) |

| Trade | 0.019 | (0.038) | 0.016 | (0.038) | 0.043 | (0.048) | −0.052 | (0.05) | 0.075 | (0.059) |

| Urbanisation | 0.106 | (0.111) | 0.313 ** | (0.141) | −0.146 | (0.152) | −0.510 *** | (0.149) | ||

| Population Growth | −0.020 | (0.034) | −0.012 | (0.044) | −0.041 | (0.052) | −0.019 | (0.057) | 0.043 | (0.065) |

| Government Expenditure | −0.075 * | (0.041) | 0.025 | (0.04) | −0.088 * | (0.052) | 0.006 | (0.053) | −0.025 | (0.063) |

| Water Facility | −0.003 | (0.024) | 0.016 *** | (0.051) | −0.094 * | (0.055) | 0.277 *** | (0.06) | ||

| Health Expenditure | 0.108 | (0.072) | ||||||||

| GDP growth | 0.014 | (0.03) | −0.023 | (0.033) | −0.124 *** | (0.046) | 0.060 | (0.05) | 0.051 | (0.058) |

| Voice and Accountability | −0.025 | (0.039) | 0.127 * | (0.077) | −0.065 | (0.049) | 0.121 * | (0.072) | ||

| Government Effectiveness | 0.148 | (0.148) | 0.364 * | (0.214) | 0.402 ** | (0.159) | −0.621 *** | (0.232) | ||

| Regulator Quality | 0.009 | (0.061) | −0.199 | (0.136) | 0.050 | (0.066) | −0.114 | (0.096) | ||

| Rule of Law | 0.114 | (0.123) | 0.270 | (0.198) | 0.164 | (0.133) | −0.308 | (0.228) | ||

| Political Stability | −0.128 ** | (0.055) | 0.150 ** | (0.073) | 0.045 | (0.041) | −0.003 | (0.09) | ||

| Corruption Control | −0.109 | (0.102) | −0.155 | (0.136) | −0.123 | (0.078) | 0.740 *** | (0.137) | ||

| MMI_lag1 | 0.927 *** | (0.067) | ||||||||

| DCT_lag1 | 0.114 ** | (0.061) | ||||||||

| RuralFI_lag1 | −0.185 * | (0.112) | ||||||||

| Constant | 0.794 *** | (0.139) | −0.863 *** | (0.076) | −0.373 ** | (0.168) | −2.046 *** | (0.175) | −1.456 *** | (0.201) |

| Observations | 589 | 581 | 443 | 443 | 443 | |||||

| R2 | 0.5906 | 0.5860 | 0.4586 | 0.3563 | 0.0409 | |||||

| (1) SDG9 | (2) FFA | (3) MMI | (4) DCT | (5) Rural FI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDG9 | 0.662 ** | (0.322) | −1.174 *** | (0.401) | 0.387 | (0.459) | 0.955 ** | (0.473) | ||

| FFA | 0.840 *** | (0.155) | ||||||||

| MMI | −0.020 | (0.034) | ||||||||

| DCT | 0.414 ** | (0.182) | ||||||||

| Rural FI | −0.157 | (0.288) | ||||||||

| Inequality | −0.045 | (0.032) | 0.003 | (0.049) | 0.007 | (0.059) | 0.086 | (0.069) | 0.212 *** | (0.072) |

| Trade | 0.048 | (0.04) | −0.011 | (0.043) | 0.070 | (0.051) | −0.092 | (0.059) | 0.109 * | (0.063) |

| Urbanisation | 0.114 | (0.1) | 0.365 ** | (0.155) | −0.229 | (0.191) | −0.679 ** | (0.177) | ||

| Population Growth | −0.068 * | (0.036) | 0.024 | (0.056) | −0.086 | (0.063) | 0.015 | (0.077) | 0.117 | (0.077) |

| Government Expenditure | −0.009 | (0.044) | −0.015 | (0.045) | 0.009 | (0.055) | 0.003 | (0.065) | −0.064 | (0.068) |

| Water Facility | 0.029 | (0.037) | 0.162 ** | (0.072) | −0.161 * | (0.085) | 0.166 | (0.089) | ||

| Health Expenditure | 0.199 *** | (0.039) | ||||||||

| GDP growth | −0.012 | (0.032) | −0.006 | (0.039) | −0.144 *** | (0.05) | 0.074 | (0.058) | 0.066 | (0.062) |

| Voice and Accountability | −0.066 | (0.058) | 0.112 | (0.095) | −0.246 ** | (0.096) | 0.433 *** | (0.113) | ||

| Government Effectiveness | 0.149 | (0.133) | 0.263 | (0.193) | 0.363 ** | (0.162) | −0.491 ** | (0.241) | ||

| Regulator Quality | 0.091 | (0.096) | −0.168 | (0.169) | 0.281 ** | (0.138) | −0.556 *** | (0.197) | ||

| Rule of Law | 0.064 | (0.122) | 0.223 | (0.192) | 0.139 | (0.15) | −0.325 | (0.249) | ||

| Political Stability | −0.094 | (0.062) | 0.147 * | (0.08) | 0.048 | (0.054) | −0.184 ** | (0.086) | ||

| Corruption Control | −0.046 | (0.115) | −0.181 | (0.146) | −0.190 | (0.116) | 0.573 *** | (0.185) | ||

| MMI_lag1 | 0.919 *** | (0.071) | ||||||||

| DCT_lag1 | 0.220 ** | (0.105) | ||||||||

| RuralFI_lag1 | −0.341 ** | (0.165) | ||||||||

| Constant | 0.028 | (0.148) | −0.398 | (0.25) | −1.303 | (0.373) | −1.695 *** | (0.372) | −0.732 * | (0.415) |

| Observations | 581 | 581 | 443 | 443 | 443 | |||||

| R2 | 0.5393 | 0.502 | 0.3432 | 0.275 | 0.0386 | |||||

Appendix A.4. Mechanism Framework Diagram

References

- Wicaksana, D.Y.; Dewi, H.S.C.P.; Erta, E. Fintech for SDGs: Driving Economic Development through Financial Innovation. J. Digit. Bus. Innov. Manag. 2023, 2, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A. Digital Finance: A Developing Country Perspective with Special Focus on Gender and Regional Disparity. Digit. Policy Regul. Gov. 2024, 26, 394–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danladi, S.; Prasad, M.S.V.; Modibbo, U.M.; Ahmadi, S.A.; Ghasemi, P. Attaining Sustainable Development Goals through Financial Inclusion: Exploring Collaborative Approaches to Fintech Adoption in Developing Economies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Fan, R. Digital Financial Inclusion and Poverty Alleviation: Evidence from the Sustainable Development of China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2023, 77, 418–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Kiran, R.; Sharma, R.K. Investigating the Impact of Financial Inclusion Drivers, Financial Literacy and Financial Initiatives in Fostering Sustainable Growth in North India. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauliukevičienė, G.; Stankevičienė, J. Assessment of the Impact of Sustainable Development Goals Indicators on the Sustainable Development of FinTech Industry. In Proceedings of the 12th International Scientific Conference “Business and Management 2022”, Vilnius, Lithuania, 12–13 May 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arner, D.W.; Buckley, R.P.; Zetzsche, D.A.; Veidt, R. Sustainability, Fintech and Financial Inclusion. Eur. Bus. Organ. Law Rev. 2020, 21, 7–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, A.; Pesqué-Cela, V.; Altunbas, Y.; Murinde, V. Fintech, Financial Inclusion and Income Inequality: A Quantile Regression Approach. Eur. J. Financ. 2022, 28, 86–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P.K. CBDC, Fintech and Cryptocurrency for Financial Inclusion and Financial Stability. Digit. Policy Regul. Gov. 2023, 25, 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Gong, X.; Guo, P.; Wu, T. What Drives Entrepreneurship in Digital Economy? Evidence from China. Econ. Model. 2019, 82, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauliukevičienė, G.; Stankevičienė, J. Assessment of the Impact of External Environment on FinTech Development. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference “Contemporary Issues in Business, Management and Economics Engineering 2021”, Vilnius, Lithuania, 13–14 May 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, O.; Talay, I.; Feridun, M. Can FinTech Promote Sustainable Finance? Policy Lessons from the Case of Turkey. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Klapper, L. Measuring Financial Inclusion: The Global Findex Database; World Bank Policy Research Working Paper; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER). World Income Inequality Database (WIID), Version 5.1. 2023. Available online: https://www.wider.unu.edu/database/world-income-inequality-database-wiid (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Choudhary, P.; Ghosh, C.; Thenmozhi, M. Impact of Fintech and Financial Inclusion on Sustainable Development Goals: Evidence from Cross-Country Analysis. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 72, 106573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daud, S.N.M.; Ahmad, A.H. Financial Inclusion, Economic Growth and the Role of Digital Technology. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 53, 103602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yawe, B.L.; Ddumba-Ssentamu, J.; Nnyanzi, J.B.; Mukisa, I. Role of Mobile Money and Digital Payments in Financial Inclusion for Sustainable Development Goals in Africa. In Globalization and Sustainability-Recent Advances, New Perspectives and Emerging Issues; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M.; Du, F. Nexus between Green Financial Development, Green Technological Innovation and Environmental Regulation in China. Renew. Energy 2023, 204, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhella, D.J. The classical and neoclassical perspectives: A theoretical framework for studying the advent and growth of mobile money—The Tanzanian experience. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2025, 29, 105–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Geng, Z. Impact of Digital Financial Inclusion on Optimization of Employment Structure: Evidence from China. Appl. Econ. 2022, 54, 662538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Gong, B. Digital Financial Inclusion and Public Service Equalization. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 71, 106440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, G.; Jin, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, Y. Broadband Infrastructure and Digital Financial Inclusion in Rural China. China Econ. Rev. 2022, 76, 101853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottah, V.E.; Ezugwu, A.L.; Ezike, T.C.; Chilaka, F.C. Digital Financial Inclusion: A Gateway to Sustainable Development. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M.; Singhal, A.; Quinlan, M.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- DeMarzo, P.M. Income Distribution and Macroeconomics. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1993, 60, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanelli, V.; Manta, F. Digital Financial Services and Open Banking Innovation: Are Banks Becoming ‘Invisible’? Glob. Bus. Rev. 2023, 199, 09721509231151491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meniago, C.; Asongu, S.A. Revisiting the Finance-Inequality Nexus in a Panel of African Countries. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2018, 46, 399–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Li, B.Z. Impact of Digital Financial Inclusion on Consumption Inequality in China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2022, 163, 529–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, L.; Hong, X.; Li, W. Can Digital Financial Inclusion Facilitate Intergenerational Income Mobility? Evidence from China. J. Comp. Econ. 2024, 52, 951–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G.; Drumm, E. Implementing the SDG Stimulus. Sustainable Development Report 2023; Dublin University Press: Dublin, Ireland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haini, H. Internet Penetration, Human Capital and Economic Growth in the ASEAN Economies: Evidence from a Translog Production Function. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2019, 26, 1774–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Telecommunication Union (ITU). Individuals Using the Internet (% of Population). Data Set. World Bank. 2023. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.USER.ZS (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- World Bank. GDP Per Capita Growth (Annual%). Data Set. 2023. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.KD.ZG (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- World Bank. GDP Per Capita, PPP (Constant 2021 International $). Data Set. 2023. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.KD (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- World Bank. General Government Final Consumption Expenditure (% of GDP). Data Set. 2023. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.CON.GOVT.ZS (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- World Bank. Maternal Mortality Ratio (Modeled Estimate, per 100,000 Live Births). Data Set. 2023. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.STA.MMRT (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- World Bank. School Enrollment, Secondary (% Gross). Data Set. 2023. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.SEC.ENRR (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- World Bank. Trade (% of GDP). Data Set. 2023. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.TRD.GNFS.ZS (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- World Bank. Worldwide Governance Indicators–Control of Corruption. Data Set. 2023. Available online: https://datos.bancomundial.org/indicador/CC.EST (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. 2023. Available online: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519 (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- World Bank. Worldwide Governance Indicators–Government Effectiveness. Data Set. 2023. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/GE.EST (accessed on 22 March 2025).

- World Bank. Domestic General Government Health Expenditure (% of GDP) [SH.XPD.GHED.GD.ZS]. World Development Indicators. 2023. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.GHED.GD.ZS (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- World Bank. Political Stability and Absence of Violence/Terrorism: Estimate [PV.EST]. Worldwide Governance Indicators. 2023. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/PV.EST (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- World Bank. Population Growth (Annual%) [SP.POP.GROW]. World Development Indicators. 2023. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.GROW (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- World Bank. Urban Population (% of Total Population) [SP.URB.TOTL.IN.ZS]. World Development Indicators. 2023. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.URB.TOTL.IN.ZS (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- World Bank. Regulatory Quality: Estimate [RQ.EST]. Worldwide Governance Indicators. 2023. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/RQ.EST (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- World Bank. Rule of Law: Estimate [RL.EST]. Worldwide Governance Indicators. 2023. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/RL.EST (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- World Bank. People Using at Least Basic Drinking Water Services (% of Population) [SH.H2O.BASW.ZS]. World Development Indicators. 2023. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.H2O.BASW.ZS (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- World Bank. Voice and Accountability: Estimate [VA.EST]. Worldwide Governance Indicators. 2023. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/VA.EST (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- The Global Findex Database 2025. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/globalfindex/report (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Sachs, J.; Lafortune, G.; Kroll, C.; Fuller, G.; Woelm, F. Sustainable Develoment Report 2022–From Crisis to Sustainable Development: The SDGs as Roadmap to 2030 and Beyond. 2022. Available online: https://www.sustainabledevelopment.report/reports/sustainable-development-report-2022/ (accessed on 21 March 2025).

- Schoofs, A. Promoting Financial Inclusion for Savings Groups: A Financial Education Programme in Rural Rwanda. J. Behav. Exp. Financ. 2022, 34, 100662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Yang, L.; Yang, C.; Wang, D.; Li, Y. Obscuring Effect of Income Inequality and Moderating Role of Financial Literacy in the Relationship between Digital Finance and China’s Household Carbon Emissions. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soriano, B.; Garrido, A. How Important Is Economic Growth for Reducing Undernourishment in Developing Countries? Food Policy 2016, 63, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glewwe, P.; Maïga, E.; Zheng, H. The Contribution of Education to Economic Growth: A Review of the Evidence, with Special Attention and an Application to Sub-Saharan Africa. World Dev. 2014, 59, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoye, L.U.; Adetiloye, K.A.; Erin, O.A. Financial Inclusion as a Strategy for Enhanced Economic Growth and Development. J. Internet Bank. Commer. 2017, 22 (Suppl. S8), 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Senyo, P.K.; Karanasios, S.; Agbloyor, E.K.; Choudrie, J. Government-Led Digital Transformation in FinTech Ecosystems. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2024, 33, 101849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, M.A.; Ibraheem, R.; Hussain, A.; Ahmad, T.I. Ahmad. Bridging the Digital Divide or Widening the Gap? Internet Penetration and Economic Growth in 85 Developing Countries. Pak. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2024, 12, 3474–3484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenzweig, E. Trustworthy Sustainable Cities. In Usability for the World: Building Better Cities and Communities; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 209–228. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, N.; Hassan, S.; Yusof, M.F.; Islam, A.; Rahim, M.M. Financial Inclusion as a Catalyst for Economic Growth: Evidence from Selected Developing Countries. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2024, 10, 2387907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tweneboah, G.; Nsiah, A.Y. Financial Inclusion, Financial Stability, and Poverty Reduction in Africa. Econ. Notes 2024, 53, e70000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghfiroh, S.I.; Purwono, R. Determinants of Financial Development: Impact of Human Capital in Emerging Markets Countries. Trikonomika 2021, 20, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, M.; Rauf, N.; Murtaza, Z. Unlocking Financial Inclusion and Economic Empowerment in Rural Pakistan: The Interplay of Financial Literacy and Infrastructure Development in the Impact of Digital Wallets. J. Excell. Manag. Sci. 2024, 3, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedemo Beyene, A. Income Inequality and Economic Complexity in Africa: The Moderating Role of Governance Quality. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2024, 10, 2341114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hametner, M. Economics without Ecology: How the SDGs Fail to Align Socioeconomic Development with Environmental Sustainability. Ecol. Econ. 2022, 199, 107490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gani, I.M.; Atiku, K.M. The Impact of Financial Inclusion on Income Equality and the Prospect of Cashless Policy for Economic Resilience in Nigeria. Jurnal Lemhannas RI 2024, 12, 228–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, B.A.; Rahman, M.N.; Sami, S. Impact of Belt and Road Initiative on Asian Economies. Glob. J. Emerg. Mark. Econ. 2019, 11, 260–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojanic, A.N. The Impact of Fiscal Decentralization on Growth, Inflation and Inequality in the Americas. CEPAL Rev. 2018, 124, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkurunziza, F.; Kabanda, R.; McSharry, P. Enhancing Poverty Classification in Developing Countries through Machine Learning: A Case Study of Household Consumption Prediction in Rwanda. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2025, 13, 2444374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetriades, P.O.; Rewilak, J.M.; Rousseau, P.L. Finance, Growth, and Fragility. J. Financ. Serv. Res. 2024, 66, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobuţă, G.I.; van Soest, H.; Bhattacharyya, S. Integrative Approaches to the Environmental and Socio-Economic SDGs. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 2024, 21, 2397609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Smadi, M.O. Examining the Relationship between Digital Finance and Financial Inclusion: Evidence from MENA Countries. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2023, 23, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, R.P.; Nair, M.S.; Hall, J.H.; Bennett, S.E.; Bahmani, S. Institutional Quality, ICT Infrastructure, Transportation, and Sustainable Development: The Case of Lower Income Countries. In Sustainable Economic Development; Ben Ali, M.S., Lechman, E., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P.K. Impact of Digital Finance on Financial Inclusion and Stability. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2018, 18, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, P.M. Increasing Returns and Long-Run Growth. J. Political Econ. 1986, 94, 1002–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, W.; Lafarre, A. Does Good Governance Mean Better Corporate Social Performance? A Comparative Study of OECD Countries. Int. Public Manag. J. 2021, 24, 762–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anifa, M.; Ramakrishnan, S.; Joghee, S.; Kabiraj, S.; Bishnoi, M.M. Bishnoi. Fintech Innovations in the Financial Service Industry. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gafoor, A.; Amilan, S. Fintech Adoption and Financial Well-Being of Persons with Disabilities: The Mediating Role of Financial Access, Financial Knowledge, and Financial Behaviour. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2024, 51, 1388–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henríquez, S.S.; Moltó, M.C.C.; Fernández, V.H.; Adell, M.J.B.; Carrillo, M.F. Sensibilidad intercultural en el alumnado y su relación con la actitud y estilo docente del profesorado ante la diversidad cultural. Interciencia 2021, 46, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca Montoya, S.; Requeiro Almeida, R.; Valdés Fonseca, A. La inclusión de estudiantes con necesidades educativas especiales vista desde el desempeño de los docentes de la educación básica ecuatoriana. Rev. Univ. Soc. 2020, 12, 438–444. [Google Scholar]

- Muttaqin, I. Religiosity and Consumer Acceptance of the Use of Islamic Digital Banking Services in Indonesia: An Extension of the UTAUT Model. Jihbiz J. Ekon. Keuang. Dan Perbank. Syariah 2024, 8, 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratiwi, R. Uncovering Determinants, Barriers, and Impacts of Financial Inclusion in Indonesia: Major Empirical Analyses and Insights. Ph.D. Thesis, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, Q.; Zaidi, S.A.H. The Relationship among Financial Inclusion, Non-Performing Loans, and Economic Growth: Insights from OECD Countries. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 939426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, E.B.; Burgess, J.C. Institutional Quality, Governance and Progress towards the SDGs. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqi, M.M. Future of Digital Education: Inclusive, Immersive, Equitable. MediaSpace DME Media J. Commun. 2024, 5, 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirigia, J.M.; Muthuri, R.N.D.K. The Fiscal Value of Human Lives Lost from Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) in China. BMC Res. Notes 2020, 13, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anane, I.; Nie, F. Determinant Factors of Digital Financial Services Adoption and Usage Level: Empirical Evidence. Int. J. Manag. Technol. 2022, 9, 26–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McVea, H. Financial Services Regulation Under the Financial Services Authority: A Reassertion of the Market Failure Thesis? Camb. Law J. 2005, 64, 413–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jima, M.D.; Makoni, P.L. Causality between Financial Inclusion, Financial Stability and Economic Growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausman, J.A. Specification Tests in Econometrics. Econom. J. Econom. Soc. 1978, 46, 1251–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canay, I.A. A Simple Approach to Quantile Regression for Panel Data. Econom. J. 2011, 14, 368–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenker, R.; Bassett, G., Jr. Regression Quantiles. Econom. J. Econom. Soc. 1978, 46, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabor, D.; Brooks, S. The Digital Revolution in Financial Inclusion: International Development in the Fintech Era. New Political Econ. 2016, 22, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altunbaş, Y.; Thornton, J. The Impact of Financial Development on Income Inequality: A Quantile Regression Approach. Econ. Lett. 2019, 175, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, E.; Poku, K.; Domeher, D. Financial Inclusion, Human Capital Development and Economic Growth in Africa: An Examination of the Transmission Channel. Sage Open 2024, 14, 21582440241271285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vulcănescu, A.; Siminel, M.A.; Dinescu, S.N.; Dijmărescu, A.L.; Manolea, M.M.; Săndulescu, S.M. Neonatal Mortality Due to Early-Onset Sepsis in Eastern Europe: A Review of Current Monitoring Protocols During Pregnancy and Maternal Demographics in Eastern Europe, with an Emphasis on Romania—Comparison with Data Extracted from a Secondary Center in Southern Romania. Children 2025, 12, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihantamalala, F.A.; Randriamihaja, M.; Miller, A.C.; Rakotonanahary, R.J.; Raza-Fanomezanjanahary, M.; Kotchofa, J.A.; Randriamanambintsoa, M.; Ramarson, H.; Razafinjato, B.; Rasoanandrasana, V.; et al. Persistence of Geographic Barriers to Maternal Care Services Following a Health System Strengthening Initiative in Rural Madagascar. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2025, 25, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, R.; Lin, C.; Xie, W. Inclusive Financial Systems, Liquidity, and Health Outcomes. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 141, 1125–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Serván-Mori, E.; Pineda-Antúnez, C.; Cerecero-García, D.; Flamand, L.; Mohar-Betancourt, A.; Millett, C.; Hone, T.; Moreno-Serra, R.; Gómez-Dantés, O. Health System Financing Fragmentation and Maternal Mortality Transition in Mexico, 2000–2022. Int. J. Equity Health 2025, 24, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Fan, L. The Nexus of Financial Education, Literacy and Mobile Fintech: Unraveling Pathways to Financial Well-Being. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2024, 42, 1789–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, S.; Huang, B.; Hu, X. Research on the Impact of Digital Finance on the High-Quality Development of Education. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 70, 106188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, K.C.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, R. Adopting Digital Financial Technology in Madhya Pradesh, Central India: Opportunities, Challenges, and Determinants. J. Knowl. Econ. 2025, 16, 10599–10638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganimian, A.J.; Murnane, R.J. Improving Education in Developing Countries: Lessons from Rigorous Impact Evaluations. Rev. Educ. Res. 2016, 86, 719–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruhn, M.; Love, I. The Real Impact of Improved Access to Finance: Evidence from Mexico. J. Financ. 2014, 69, 1347–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Li, J.; Wu, X. Financial Inclusion, Education, and Employment: Empirical Evidence from 101 Countries. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloulou, M.; Grati, R.; Al-Qudah, A.A.; Al-Okaily, M. Does FinTech Adoption Increase the Diffusion Rate of Digital Financial Inclusion? A Study of the Banking Industry Sector. J. Financ. Report. Account. 2024, 22, 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavriya, S.; Sharma, G.D.; Mahendru, M. Financial Inclusion as a Tool for Sustainable Macroeconomic Growth: An Integrative Analysis. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2024, 95, 527–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, D. Does Digital Financial Inclusion Reduce the Risk of Returning to Poverty? Evidence from China. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2024, 29, 2927–2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Z.; He, G. Digital Financial Inclusion and Sustainable Employment: Evidence from Countries along the Belt and Road. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2021, 21, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkova, A.; Peter, K.S.; Svejnar, J. Labor Informality and Credit Market Accessibility. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.05803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Fátima Ferreiro, M.; Sousa, C.; Sheikh, F.A.; Novikova, M. Social Innovation and Rural Territories: Exploring Invisible Contexts and Actors in Portugal and India. J. Rural Stud. 2023, 99, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awa, T.; Abdou Khadre, D. Financial Inclusion, ICT Development and Economic Growth in WAEMU Countries: Evidence of Governance. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2025, 16, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpofu, F.Y. Industry 4.0 in Financial Services: Mobile Money Taxes, Revenue Mobilisation, Financial Inclusion, and the Realisation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in Africa. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.; Huang, L.; Wang, Z. Supply Chain Financing, Digital Financial Inclusion and Enterprise Innovation: Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 91, 103044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Wu, J.; Li, H.; Nguyen, D.K. Local Bank, Digital Financial Inclusion and SME Financing Constraints: Empirical Evidence from China. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2022, 58, 1712–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, N.; Bhuyan, R. Effect of Fintech on Sustainable Development Goals: An Empirical Analysis. Bull. Appl. Econ. 2024, 11, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Klapper, L.; Singer, D.; Ansar, S.; Hess, J. The Global Findex Database 2021: Financial Inclusion, Digital Payments, and Resilience in the Age of COVID-19. World Bank. 2022. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/globalfindex (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Azmeh, C.; Al-Raeei, M. Exploring the Dual Relationship between Fintech and Financial Inclusion in Developing Countries and Their Impact on Economic Growth: Supplement or Substitute? PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0315174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amemiya, T. Advanced Econometrics; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, W.H. Econometric Analysis; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh, A.A.; Glavee-Geo, R.; Karjaluoto, H.; Hinson, R.E. Mobile Money as a Driver of Digital Financial Inclusion. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 186, 122158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Duvendack, M. Digital Credit for All? An Empirical Analysis of Mobile Loans for Financial Inclusion in Kenya. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2025, 31, 559–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Amri, M.C.; Mohammed, M.O.; Shabani, R.M. A Survey of the Opinions of Regulators on the Impact of FinTech on the Islamic Finance Industry in Turkey and Malaysia. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Islamic Economics (ICONIE), Online, 30–31 March 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.; Zhang, W. Financial Inclusion in China: Policy, Experience, and Outlook; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Yuan, X. Financial Inclusion in China: An Overview. Front. Bus. Res. China 2021, 15, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lunku, H.S.; Yang, S. Financial Inclusion in the Digital Era: A Key Driver for Reducing Income Inequality. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2025, 31, 706–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Y. The Impact of Digital Finance on Insurance Participation. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 73, 106670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sensen, J. A Study on the Impact of Digital Financial Inclusion on the Performance of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises Under the Impact of COVID-19. J. Econ. Manag. Trade 2023, 29, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, M.; Triharyati, E.; Rimbano, D. Influence Financial Technology, Financial Literacy, and Intellectual Capital on Financial Inclusion in Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs). Ilomata Int. J. Tax Account. 2022, 3, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Definition and Measurement | Source |

|---|---|---|

| SDG 3 | Log of Maternal Death | World Development Indicators (WDI) |

| SDG 4 | School Enrollment (% population) | WDI |

| SDG 8 | Log GDP per capita | WDI |

| SDG 9 | Individuals using the Internet (% of population) | ITU |

| Inequality | Standardized World Income Inequality Database (SWIID). Gini Index: a Gini index of 0 represents perfect equality, while an index of 100 implies perfect inequality. | World Income Inequality Database |

| Formal Financial Access (Index) | “Used a mobile phone or the internet to check account balance (% age 15+), Made or received a digital payment (% age 15+), Financial institution account (% age 15+), Saved at a financial institution (% age 15+), Made a utility payment: using a financial institution account (% age 15+), Owns a debit card, (% age 15+), Owns a debit card, poorer (% age 15+), Received wages, into a financial institution account (% age 15+), Received wages, poorer (% age 15+). | Global Findex |

| Mobile Money Index | “Mobile money account (% age 15+), Mobile money account, income, poorest 40% (% ages 15+), Mobile money account, rural (% age 15+) | Global Findex |

| Digital Credit & Transfers (Index) | Use a mobile phone or the internet to make payment, Used a mobile phone or the internet to send money (% age 15+), Borrowed any money from a formal financial institution or using a mobile money account (% age 15+) | Global Findex |

| Rural Finance (Index) | Owns a debit card, rural (% ages 15–24), Received wages, rural (% ages 15–24) | Global Findex |

| Trade | Trade (%GDP) | WDI |

| Urbanisation | Urban Population (% of Total) | WDI |

| Population Growth | Population growth (annual %) | WDI |

| Government Expenditure | Government Expenditure (% of GDP) | WDI |

| Water Facility | People using at least basic drinking water services (% of population) | WDI |

| Health Expenditure | Domestic general government health expenditure (% of GDP) | WDI |

| GDP growth | GDP per capita growth (% annual) | WDI |

| Voice and Accountability | Voice and Accountability captures perceptions of the extent to which a country’s citizens are able to participate in selecting their government, as well as freedom of expression, freedom of association, and a free media. Estimate gives the country’s score on the aggregate indicator, in units of a standard normal distribution, i.e., ranging from approximately −2.5 to 2.5. | World Governance Indicators (WGI) |

| Government Effectiveness | Government Effectiveness captures perceptions of the quality of public services, the quality of the civil service and the degree of its independence from political pressures, the quality of policy formulation and implementation, and the credibility of the government’s commitment to such policies. Estimate gives the country’s score on the aggregate indicator, in units of a standard normal distribution, i.e., ranging from approximately −2.5 to 2.5. | WGI |

| Regulator Quality | The Regulatory Quality estimate in the World Development Indicators (WDI) reflects the perceived ability of a country’s government to formulate and implement sound policies and regulations that support private sector development. It is one of the six dimensions of governance measured by the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) (WGI), which are produced by the World Bank. The Regulatory Quality estimate is presented as a standardized score, typically ranging from −2.5 to 2.5, with higher scores indicating better regulatory quality. | WGI |

| Rule of Law | Rule of Law captures perceptions of the extent to which agents have confidence in and abide by the rules of society, and in particular the quality of contract enforcement, property rights, the police, and the courts, as well as the likelihood of crime and violence. Estimate gives the country’s score on the aggregate indicator, in units of a standard normal distribution, i.e., ranging from approximately −2.5 to 2.5. | WGI |

| Political Stability | Political Stability and Absence of Violence/Terrorism measures perceptions of the likelihood of political instability and/or politically-motivated violence, including terrorism. Estimate gives the country’s score on the aggregate indicator, in units of a standard normal distribution, i.e., ranging from approximately −2.5 to 2.5 | WGI |

| Corruption Control | Measures the extent to which public power is exercised for private gain, including petty and grand corruption, and the capture of the state by elites and private interests. It is an aggregate indicator ranging from approximately −2.5 to 2.5, with higher scores indicating lower levels of corruption. | WGI |

| Variable | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDG 3-Health | 163.7942 | 242.6934 | 0 | 1662 |

| SDG 4-Education | 0.6493123 | 0.442752 | 0 | 1.62422 |

| SFG 8-Decent work and economic growth | 14,503.58 | 21,676.79 | 0 | 134,965.8 |

| SDG 9-Industry, innovation and infrastructure | 0.4804598 | 0.3093509 | 0 | 1 |

| Formal Financial Access | −4.84 × 10−16 | 1 | −2.318284 | 2.470754 |

| Mobile Money | −3.49 × 10−19 | 1 | −2.689258 | 6.418031 |

| Direct Credit and Transfers | −3.93 × 10−17 | 1 | −3.038604 | 4.72196 |

| Rural Financial Access | −2.93 × 10−18 | 1 | −2.560755 | 7.514234 |

| Inequality | 36.23246 | 9.670869 | 0 | 63 |

| Trade | 0.7961813 | 0.5014696 | 0 | 3.931412 |

| Urbanisation | 0.5794366 | 0.2192012 | 0 | 0.99278 |

| Population Growth | 0.012752 | 0.0155345 | 0.1092744 | 0.1158171 |

| Government Expenditure | 0.1474412 | 0.065312 | 0 | 0.3968057 |

| Water Facility | 0.8437025 | 0.209835 | 0 | 1 |

| Health Expenditure | 0.0343905 | 0.0237946 | 0 | 0.1020335 |

| GDP growth | 3.021634 | 3.994628 | −15.33669 | 33.76856 |

| Voice Accountability | −0.084633 | 0.9600761 | −2.259265 | 1.738036 |

| Government Effectiveness | −0.064277 | 0.9695092 | −2.440221 | 2.235192 |

| Regulator Quality | −0.016336 | 0.9475239 | −2.102013 | 2.040489 |

| Rule of Law | −0.10765 | 0.9660785 | −2.097953 | 2.124762 |

| Political Stability | −0.225219 | 0.9340703 | −2.934317 | 1.402653 |

| Corruption Control | −0.138072 | 0.9793363 | −1.836981 | 2.392884 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | (14) | (15) | (16) | (17) | (18) | (19) | (20) | (21) | (22) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Inequality | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| (2) Formal Financial Access | −0.20 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| (3) Mobile Money Index | 0.17 | −0.10 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||||||

| (4) Digital Credit & Transfers | −0.06 | 0.53 | 0.19 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||||

| (5) Rural Finance | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.39 | 0.30 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||||

| (6) SDG 3 | 0.40 | −0.58 | 0.33 | −0.15 | 0.08 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||

| (7) SDG 4 | −0.16 | 0.48 | −0.25 | 0.20 | 0.01 | −0.58 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||

| (8) SDG 8 | −0.25 | 0.67 | −0.28 | 0.25 | −0.07 | −0.81 | 0.60 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||

| (9) SDG 9 | −0.27 | 0.70 | −0.13 | 0.35 | 0.10 | −0.73 | 0.63 | 0.84 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

| (10) Trade | −0.15 | 0.31 | −0.12 | 0.10 | −0.03 | −0.39 | 0.25 | 0.40 | 0.39 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| (11) Urbanisation | −0.07 | 0.45 | −0.20 | 0.16 | −0.04 | −0.57 | 0.50 | 0.76 | 0.73 | 0.31 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| (12) Population Growth | 0.16 | −0.36 | 0.19 | −0.19 | 0.01 | 0.47 | −0.40 | −0.40 | −0.43 | −0.13 | −0.24 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| (13) Government Expenditure | −0.01 | 0.34 | −0.12 | 0.14 | −0.07 | −0.42 | 0.35 | 0.41 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.38 | −0.21 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| (14) Water Facility | −0.22 | 0.37 | −0.20 | 0.13 | −0.01 | −0.52 | 0.50 | 0.61 | 0.62 | 0.26 | 0.59 | −0.31 | 0.25 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| (15) Health Expenditure | −0.12 | 0.65 | −0.24 | 0.31 | −0.05 | −0.65 | 0.59 | 0.77 | 0.74 | 0.28 | 0.62 | −0.40 | 0.61 | 0.47 | 1.00 | |||||||

| (16) GDP growth | −0.03 | 0.13 | −0.06 | 0.27 | 0.12 | −0.13 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.00 | −0.30 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 1.00 | ||||||

| (17) Voice and Accountability | −0.07 | 0.54 | −0.15 | 0.19 | −0.04 | −0.51 | 0.56 | 0.69 | 0.60 | 0.30 | 0.49 | −0.32 | 0.44 | 0.39 | 0.73 | 0.11 | 1.00 | |||||

| (18) Government Effectiveness | −0.21 | 0.65 | −0.22 | 0.21 | −0.06 | −0.73 | 0.62 | 0.86 | 0.77 | 0.39 | 0.60 | −0.33 | 0.47 | 0.54 | 0.75 | 0.14 | 0.78 | 1.00 | ||||

| (19) Regulator Quality | −0.13 | 0.63 | −0.23 | 0.20 | −0.06 | −0.68 | 0.61 | 0.82 | 0.74 | 0.40 | 0.59 | −0.35 | 0.46 | 0.50 | 0.74 | 0.11 | 0.84 | 0.93 | 1.00 | |||

| (20) Rule of Law | −0.16 | 0.66 | −0.19 | 0.22 | −0.07 | −0.66 | 0.58 | 0.82 | 0.72 | 0.37 | 0.56 | −0.30 | 0.47 | 0.48 | 0.75 | 0.10 | 0.84 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 1.00 | ||

| (21) Political Stability | −0.12 | 0.49 | −0.15 | 0.16 | −0.06 | −0.55 | 0.45 | 0.69 | 0.59 | 0.43 | 0.45 | −0.27 | 0.36 | 0.39 | 0.62 | 0.20 | 0.70 | 0.75 | 0.71 | 0.77 | 1.00 | |

| (22) Corruption Control | −0.15 | 0.62 | −0.20 | 0.23 | −0.06 | −0.63 | 0.55 | 0.70 | 0.69 | 0.36 | 0.56 | −0.27 | 0.48 | 0.45 | 0.75 | 0.08 | 0.80 | 0.92 | 0.89 | 0.96 | 0.75 | 1.00 |

| Variable | VIF | 1/VIF |

|---|---|---|

| Rule of Law | 27.09 | 0.037 |

| Government Efficiency | 15.22 | 0.066 |

| Regulator Quality | 12.76 | 0.078 |

| Corruption Control | 12.55 | 0.080 |

| Voice and Accountability | 4.56 | 0.219 |

| Health Expenditure | 4.55 | 0.220 |

| Political Stability | 2.98 | 0.336 |

| Formal Financial Access | 2.85 | 0.350 |

| Urbanisation | 2.25 | 0.444 |

| Government Expenditure | 2.01 | 0.498 |

| Water Facility | 1.83 | 0.546 |

| Digital Credit and Transfers | 1.82 | 0.548 |

| Trade | 1.64 | 0.610 |

| Population Growth | 1.42 | 0.706 |

| Mobile Money | 1.40 | 0.713 |

| GDP growth | 1.31 | 0.765 |

| Rural Index | 1.30 | 0.770 |

| Inequality | 1.20 | 0.830 |

| Mean VIF | 5.49 |

| Variables | (1) Panel Data (FE) | (2) (0.25) | (3) (0.50) | (4) (0.75) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formal Financial Access (Index) | −0.028 ** | (0.014) | −0.006 | (0.009) | −0.013 | (0.01) | −0.031 *** | (0.01) |

| Mobile Money (Index) | −0.021 ** | (0.01) | −0.005 | (0.006) | −0.014 ** | (0.007) | −0.028 *** | (0.006) |

| Digital Credit & Transfers (Index) | 0.023 *** | (0.009) | 0.006 | (0.007) | 0.027 *** | (0.007) | 0.040 *** | (0.007) |

| Rural Finance (Index) | 0.019 ** | (0.008) | 0.011 * | (0.006) | 0.014 ** | (0.006) | 0.031 *** | (0.006) |

| Inequality | −0.100 *** | (0.038) | −0.099 *** | (0.005) | −0.103 *** | (0.006) | −0.101 *** | (0.006) |

| Trade | 0.039 * | (0.022) | 0.032 *** | (0.006) | 0.030 *** | (0.007) | 0.039 *** | (0.007) |

| Urbanisation | −0.318 ** | (0.143) | −0.255 *** | (0.007) | −0.245 *** | (0.008) | −0.233 *** | (0.008) |

| Population Growth | −0.013 | (0.01) | −0.011 * | (0.006) | −0.015 ** | (0.006) | −0.018 *** | (0.006) |

| Government Expenditure | −0.074 *** | (0.023) | −0.062 *** | (0.007) | −0.067 *** | (0.008) | −0.068 *** | (0.007) |

| Water Facility | −0.025 | (0.02) | −0.024 *** | (0.007) | −0.036 *** | (0.007) | −0.034 *** | (0.007) |

| Health Expenditure | 0.124 *** | (0.033) | 0.121 *** | (0.01) | 0.118 *** | (0.011) | 0.117 *** | (0.011) |

| GDP growth | 0.044 *** | (0.009) | 0.044 *** | (0.006) | 0.038 *** | (0.006) | 0.037 *** | (0.006) |

| Voice and Accountability | −0.008 | (0.05) | 0.000 | (0.01) | −0.008 | (0.011) | −0.011 | (0.011) |

| Government Effectiveness | −0.066 | (0.048) | −0.073 *** | (0.019) | −0.047 ** | (0.021) | −0.090 *** | (0.02) |

| Regulator Quality | −0.049 | (0.047) | −0.047 *** | (0.018) | −0.029 | (0.019) | −0.047 ** | (0.018) |

| Rule of Law | 0.068 | (0.061) | 0.036 | (0.026) | 0.032 | (0.028) | 0.095 *** | (0.027) |

| Political Stability | −0.016 | (0.027) | −0.013 | (0.008) | −0.007 | (0.009) | −0.013 | (0.009) |

| Corruption Control | −0.064 | (0.05) | −0.038 ** | (0.017) | −0.060 *** | (0.019) | −0.056 *** | (0.018) |

| Time effect | −0.001 | (0.004) | −0.028 *** | (0.006) | −0.020 *** | (0.007) | −0.007 | (0.006) |

| Constant | 1.910 | (7.218) | −0.004 | (0.016) | 0.042 ** | (0.018) | 0.076 *** | (0.017) |

| Observations | 589 | 589 | 589 | 589 | ||||

| Pseudo R2 (for quantile regressions) | 0.6938 | 0.6918 | 0.6765 | |||||

| R2 Within | ||||||||

| R2 Between | 0.1688 | |||||||

| R2 Overall | 0.1673 | |||||||

| Variables | (1) Panel Data (FE) | (2) (0.25) | (3) (0.50) | (4) (0.075) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formal Financial Access (Index) | 0.032 | (0.052) | 0.010 | (0.035) | 0.027 | (0.016) | 0.031 | (0.042) |

| Mobile Money (Index) | −0.001 | (0.038) | 0.014 | (0.023) | 0.001 | (0.011) | −0.008 | (0.028) |

| Digital Credit & Transfers (Index) | −0.015 | (0.034) | −0.027 | (0.026) | −0.037 *** | (0.012) | −0.003 | (0.031) |

| Rural Finance (Index) | 0.020 | (0.03) | −0.004 | (0.022) | 0.003 | (0.01) | −0.003 | (0.026) |

| Inequality | −0.123 | (0.144) | −0.107 *** | (0.021) | −0.123 *** | (0.01) | −0.104 *** | (0.025) |

| Trade | 0.104 | (0.083) | 0.107 *** | (0.024) | 0.084 *** | (0.011) | 0.082 *** | (0.029) |

| Urbanisation | 0.080 | (0.547) | 0.049 * | (0.028) | 0.093 *** | (0.013) | 0.079 ** | (0.034) |

| Population Growth | 0.009 | (0.038) | −0.003 | (0.023) | −0.002 | (0.011) | −0.023 | (0.027) |

| Government Expenditure | −0.135 | (0.086) | −0.119 *** | (0.027) | −0.121 *** | (0.013) | −0.133 *** | (0.032) |

| Water Facility | 0.012 | (0.078) | 0.003 | (0.026) | 0.007 | (0.012) | 0.029 | (0.031) |

| Health Expenditure | 0.140 | (0.125) | 0.132 *** | (0.04) | 0.123 *** | (0.019) | 0.110 ** | (0.048) |

| GDP growth | 0.007 | (0.034) | 0.006 | (0.022) | 0.016 | (0.01) | 0.005 | (0.026) |

| Voice and Accountability | 0.356 * | (0.192) | 0.448 *** | (0.04) | 0.347 *** | (0.019) | 0.286 *** | (0.048) |

| Government Effectiveness | 0.279 | (0.185) | 0.313 *** | (0.074) | 0.221 *** | (0.035) | 0.109 | (0.089) |

| Regulator Quality | 0.266 | (0.182) | 0.328 *** | (0.067) | 0.273 *** | (0.032) | 0.230 *** | (0.081) |

| Rule of Law | −0.282 | (0.236) | −0.378 *** | (0.098) | −0.217 *** | (0.046) | −0.145 | (0.118) |

| Political Stability | −0.035 | (0.104) | −0.069 ** | (0.033) | −0.027 *** | (0.015) | −0.027 | (0.039) |

| Corruption Control | 0.021 | (0.192) | 0.053 | (0.067) | 0.021 | (0.031) | 0.126 | (0.08) |

| Time effect | 0.009 | (0.014) | 0.034 | (0.024) | 0.017 | (0.011) | 0.028 | (0.028) |

| Constant | −18.486 | (27.71) | −0.215 *** | (0.062) | −0.021 | (0.029) | 0.115 | (0.074) |

| Observations | 589 | 589 | 589 | 589 | ||||

| Pseudo R2 (for quantile regressions) | 0.5475 | 0.6233 | 0.6053 | |||||

| R2 Within | 0.0568 | |||||||

| R2 Between | 0.5243 | |||||||

| R2 Overall | 0.4207 | |||||||

| Variables | (1) Panel Data (FE) | (2) (0.25) | (3) (0.50) | (4) (0.75) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formal Financial Access (Index) | −0.009 | (0.011) | −0.006 | (0.009) | −0.010 | (0.007) | −0.022 ** | (0.01) |

| Mobile Money (Index) | −0.005 | (0.008) | −0.005 | (0.006) | −0.005 | (0.005) | −0.010 | (0.007) |

| Digital Credit & Transfers (Index) | 0.018 ** | (0.007) | 0.018 *** | (0.007) | 0.018 *** | (0.005) | 0.031 *** | (0.008) |

| Rural Finance (Index) | 0.003 | (0.006) | 0.004 | (0.006) | 0.004 | (0.004) | 0.003 | (0.007) |

| Inequality | 0.039 | (0.03) | 0.039 *** | (0.005) | 0.045 *** | (0.004) | 0.039 *** | (0.006) |

| Trade | 0.006 | (0.018) | 0.008 | (0.006) | 0.005 | (0.005) | 0.006 | (0.007) |

| Urbanisation | 0.057 | (0.115) | 0.058 *** | (0.007) | 0.068 *** | (0.006) | 0.079 *** | (0.008) |

| Population Growth | 0.015 * | (0.008) | 0.018 *** | (0.006) | 0.021 *** | (0.005) | 0.014 ** | (0.007) |

| Government Expenditure | 0.020 | (0.018) | 0.029 *** | (0.007) | 0.018 *** | (0.005) | 0.008 | (0.008) |

| Water Facility | −0.001 | (0.016) | 0.000 | (0.007) | −0.002 | (0.005) | −0.003 | (0.008) |

| Health Expenditure | 0.016 | (0.026) | 0.008 | (0.01) | 0.026 *** | (0.008) | 0.025 ** | (0.012) |

| GDP growth | 0.014 ** | (0.007) | 0.011 ** | (0.006) | 0.017 *** | (0.004) | 0.020 *** | (0.007) |

| Voice and Accountability | −0.121 *** | (0.041) | −0.104 *** | (0.01) | −0.120 *** | (0.008) | −0.129 *** | (0.012) |

| Government Effectiveness | 0.100 ** | (0.039) | 0.094 *** | (0.019) | 0.110 *** | (0.015) | 0.115 *** | (0.022) |

| Regulator Quality | 0.024 | (0.038) | 0.039 ** | (0.017) | 0.023 *** | (0.014) | −0.014 | (0.02) |

| Rule of Law | 0.184 *** | (0.05) | 0.159 *** | (0.025) | 0.167 *** | (0.02) | 0.207 *** | (0.029) |

| Political Stability | 0.032 | (0.022) | 0.029 *** | (0.008) | 0.028 *** | (0.007) | 0.033 *** | (0.01) |

| Corruption Control | 0.009 | (0.041) | 0.028 | (0.017) | 0.017 | (0.014) | −0.002 | (0.02) |

| Time Effect | 0.005 * | (0.003) | 0.018 *** | (0.006) | 0.015 *** | (0.005) | 0.014 ** | (0.007) |

| Constant | −10.72 * | (5.845) | −0.096 *** | (0.016) | −0.037 *** | (0.013) | 0.022 | (0.019) |

| Observations | 589 | 589 | 589 | 589 | ||||

| Pseudo R2 (for quantile regressions) | 0.7200 | 0.7367 | 0.7414 | |||||

| R2 Within | 0.2376 | |||||||

| R2 Between | 0.7451 | |||||||

| R2 Overall | 0.7271 | |||||||

| Variables | (1) Panel Data (FE) | (2) (0.25) | (3) (0.50) | (4) (0.75) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formal Financial Access (Index) | −0.030 | (0.026) | −0.016 | (0.021) | −0.022 | (0.016) | −0.068 ** | (0.027) | |

| Mobile Money (Index) | 0.038 ** | (0.019) | 0.026 * | (0.014) | 0.056 *** | (0.011) | 0.027 | (0.018) | |

| Digital Credit & Transfers (Index) | −0.060 *** | (0.017) | −0.061 *** | (0.016) | −0.056 *** | (0.012) | −0.035 * | (0.02) | |

| Rural Finance (Index) | 0.065 *** | (0.015) | 0.059 *** | (0.013) | 0.072 *** | (0.01) | 0.083 *** | (0.017) | |

| Inequality | −0.043 | (0.071) | −0.035 *** | (0.013) | −0.051 *** | (0.01) | −0.066 *** | (0.016) | |

| Trade | 0.077 * | (0.041) | 0.087 *** | (0.015) | 0.085 *** | (0.011) | 0.092 *** | (0.018) | |

| Urbanisation | 0.530 ** | (0.267) | 0.520 *** | (0.017) | 0.556 *** | (0.013) | 0.527 *** | (0.022) | |

| Population Growth | −0.021 | (0.019) | −0.023 | (0.014) | −0.029 *** | (0.01) | −0.008 | (0.017) | |

| Government Expenditure | −0.001 | (0.043) | −0.006 | (0.016) | −0.008 | (0.012) | 0.010 | (0.02) | |

| Water Facility | −0.026 | (0.038) | −0.028 * | (0.016) | −0.040 *** | (0.012) | −0.035 * | (0.02) | |

| Health Expenditure | 0.169 *** | (0.062) | 0.173 *** | (0.025) | 0.182 *** | (0.019) | 0.161 *** | (0.031) | |

| GDP growth | −0.015 | (0.017) | −0.007 | (0.013) | −0.013 | (0.01) | −0.016 | (0.017) | |

| Voice and Accountability | 0.086 | (0.095) | 0.115 *** | (0.025) | 0.062 *** | (0.019) | 0.085 *** | (0.031) | |

| Government Effectiveness | 0.120 | (0.091) | 0.128 *** | (0.046) | 0.106 *** | (0.035) | 0.094 * | (0.057) | |

| Regulator Quality | 0.089 | (0.09) | 0.092 ** | (0.041) | 0.076 *** | (0.031) | 0.032 | (0.052) | |

| Rule of Law | 0.129 | (0.116) | 0.136 ** | (0.06) | 0.158 *** | (0.046) | 0.151 ** | (0.075) | |

| Political Stability | 0.024 | (0.052) | 0.023 | (0.02) | 0.006 | (0.015) | 0.007 | (0.025) | |

| Corruption Control | −0.098 | (0.095) | −0.138 *** | (0.041) | −0.098 *** | (0.031) | −0.030 | (0.051) | |

| Time effect | 0.275 *** | (0.022) | 0.261 *** | (0.015) | 0.255 *** | (0.011) | 0.289 *** | (0.018) | |

| Constant | −0.688 | (0.055) | −0.787 *** | (0.038) | −0.642 *** | (0.029) | −0.577 *** | (0.048) | |

| Observations | 589 | 589 | 589 | 589 | |||||

| Pseudo R2 (for quantile regressions) | 0.7906 | 0.8076 | 0.7908 | ||||||

| R2 Within | 0.7186 | ||||||||

| R2 Between | 0.8238 | ||||||||

| R2 Overall | 0.8035 | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kattan-Rodríguez, G.E.; Galindo-Manrique, A.F. From Access to Impact: How Digital Financial Inclusion Drives Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10799. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310799

Kattan-Rodríguez GE, Galindo-Manrique AF. From Access to Impact: How Digital Financial Inclusion Drives Sustainable Development. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10799. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310799

Chicago/Turabian StyleKattan-Rodríguez, Gerardo Enrique, and Alicia Fernanda Galindo-Manrique. 2025. "From Access to Impact: How Digital Financial Inclusion Drives Sustainable Development" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10799. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310799

APA StyleKattan-Rodríguez, G. E., & Galindo-Manrique, A. F. (2025). From Access to Impact: How Digital Financial Inclusion Drives Sustainable Development. Sustainability, 17(23), 10799. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310799