Abstract

Coordinating ecosystem services (ESs) and socioeconomic development is crucial for sustainability. This study examined Hebei Province, China, a representative region within the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei area with diverse ecosystems and sharp developmental contrasts. A comprehensive evaluation framework aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) was developed, integrating economic, social, and ES dimensions. The entropy weight-TOPSIS method was used for overall assessment, and self-organizing maps (SOM) were employed to analyze spatial coupling relationships. The results indicate that social and economic indicators often exhibit synergistic effects, whereas trade-offs dominate the relationship between socioeconomic indicators and ecosystem services. In the multidimensional coordinated development zone is coordinated, all three dimensions display integrated progress. Socioeconomic development in Hebei Province shows a “multi-sphere” pattern of spatial expansion, while ecosystem services reveal distinct “mountain–plain” contrasts. Ecological functions have undergone significant transformations across prefecture from 2005 to 2020, with the region as a whole demonstrating coordinated development—characterized by relatively stable ecosystem services alongside gradual improvement in the low socioeconomic development zone. This study clarifies the synergistic mechanisms between regional development and ES, providing a theoretical and methodological basis for differentiated sustainable development strategies under the SDG framework.

1. Introduction

The SDGs, introduced by the United Nations in 2015 as part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, constitute a comprehensive global framework for guiding development efforts [1,2]. They seek to mobilize nations toward the collective achievement of 17 core objectives by 2030, encompassing poverty eradication, ecological protection, the promotion of social equity, and the realization of peaceful and prosperous societies. To further advance the practical implementation of SDGs, the concept of pragmatic sustainability has gained increasing attention in recent years [3,4]. An expanding body of research has begun to explore feasible pathways toward sustainability from the perspectives of governance systems [5], energy transitions [6], and environmental management [7]. The realization of pragmatic sustainability depends on the scientific quantification of sustainability progress and the timely adjustment of policies and management strategies based on monitoring outcomes [8,9]. Within this process, economic growth, social progress, and ecological protection constitute the core dimensions for assessing regional sustainability and serve as the fundamental framework for constructing a pragmatic sustainability evaluation system [10]. As one of the fastest-growing and most populous countries, China faces significant challenges in reconciling socio-economic advancement with ecological sustainability [11], while also serving as a critical empirical case for informing global pathways toward sustainability. In this context, the quest for a dynamic balance between economic development, social progress, and ecological protection amid rapid industrialization and urbanization has emerged as a prominent research frontier, drawing substantial scholarly attention worldwide.

The interrelationships among economic development, social progress, and ecological sustainability are often examined through the dual lenses of trade-offs and synergies. In the early stages of economic growth, widening inequality constrains long-term development, though coordinated regional advancement can later alleviate these disparities and foster alignment between social well-being and economic performance [12,13,14]. The interaction between economic development and ecological outcomes is frequently explained by the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC), which describes an inverted U-shaped trajectory wherein ecological degradation intensifies with initial economic expansion but is gradually mitigated as economies adopt greener practices and sustainable innovations [15,16,17], Similarly, while rising social demands for resources are commonly associated with ecological degradation, a synergistic feedback mechanism has been theorized, whereby ecological restoration enhances social well-being, and improved social well-being, in turn, reinforces ecological protection [18,19,20,21].

Recent studies have increasingly focused on methods for identifying trade-offs and synergies among social progress, economic development, and ecological sustainability, examining their driving factors, spatial heterogeneity, and implications for policy and governance. A central approach has been the evaluation of the Coupling Coordination Degree (CCD) of socio-economic and ecological systems across multiple spatial scales, including nations [22,23], river basins [24,25], urban agglomeration [26], and provinces or prefecture-level cities [27]. These assessments capture the degree of consistency in development levels and growth rates among the three systems. Empirical analyses of 30 Chinese provinces [22] and resource-based cities in Northeast China [28] indicate that most regions remain at low to moderate levels of socio-ecological coordination, with some exhibiting declining CCD, reflecting delayed industrial restructuring alongside mounting ecological pressures. The Social–Economic–Resource–Environment CCD across prefectures in Hebei Province remain at relatively low levels [29]. Xu et al. [30] emphasize that the tension between socio-economic development and the ecological environment in Hebei necessitates further industrial restructuring to promote improvement.

To further reveal feedback dynamics and spatial heterogeneity, methods such as geographically weighted regression [31], structural equation modeling [32], and multilevel variable analysis [33] have been employed. Findings highlight characteristic spatial patterns of coordination, including “low in the northwest and high in the southeast” [22,34], “higher in urban than rural regions” [35], and “lower in mountainous areas than in plains” [36]. largely shaped by terrain, transportation, and related factors [35]. Building on these insights, researchers have proposed long-term strategies for region-specific collaborative development, emphasizing governance optimization, ecological compensation, and livelihood transformation [37,38]. Such strategies provide both theoretical foundations and practical pathways for advancing ecological civilization and achieving regional sustainable development.

However, existing studies have largely concentrated on overall coupling measurements at broad spatial scales, while paying insufficient attention to the spatial interrelationships, structural dependencies, and interactional characteristics of internal indicators within the three systems. Pragmatic sustainability requires a fine-grained understanding of internal spatial dynamics [39], as the absence of spatially explicit interaction analysis can cause decision-makers to overlook regional heterogeneity and misjudge local constraints, ultimately undermining the formulation of SDG-oriented targeted interventions [40]. Given that both ecosystem service assessments and SDG indicator analyses are inherently multidimensional, integrative approaches are required to better capture the trade-offs and synergies among indicators. To address this gap, the present study introduces the concept of the “ecosystem service bundles” and extends it into an “SDGs bundles” framework. These bundles denote recurring spatial–temporal combinations of ecosystem services, which help to reveal patterns of synergy, trade-off, and spatial aggregation across services [41]. Methods for identifying such bundles include principal component analysis (PCA) [42], cluster analysis [41], spatial autocorrelation [43], and SOM [44], with SOM offering particular advantages in handling high-dimensional data, reducing human interference, and identifying the optimal number of clusters.

Hebei Province—situated at the core of the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei coordinated development region—has diverse topography and complex urban functions [45]. From the perspective of the urban sustainability index [46], prefecture in the central region of Hebei Province are relatively stable, while those in the northern region are comparatively lower. Yang et al. [47] reported that Shijiazhuang exhibits the highest sustainable development capacity, whereas Chengde demonstrates a comparatively lower capacity relative to other regions. These observations indicate distinct regional characteristics in the sustainability evaluation of Hebei Province, and the CCD is shifting from a low–moderate coupling stage toward a moderate–high stage [48]. Accordingly, investigating governance pathways for multi-system coordination at geospatial and regional levels in Hebei carries substantial practical significance.

This study examines the localized implementation of the SDGs at the regional scale. Grounded in the theoretical framework of coordinated development across social progress, economic growth, and ecological sustainability, it constructs an SDG assessment framework for Hebei Province through the integration of spatial indicators. By introducing the concept of the “bundles” and employing the SOM method, the study seeks to reveal the coupling interactions and spatial clustering patterns among multidimensional indicators across the three systems. This approach not only enhances the precision of geospatial identification and the representational capacity of spatial interactions but also extends the analytical capabilities of traditional coupling measurement methods. In doing so, it deepens the understanding of multi-system interaction mechanisms and provides both theoretical underpinnings and practical pathways for advancing multi-objective coordinated governance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

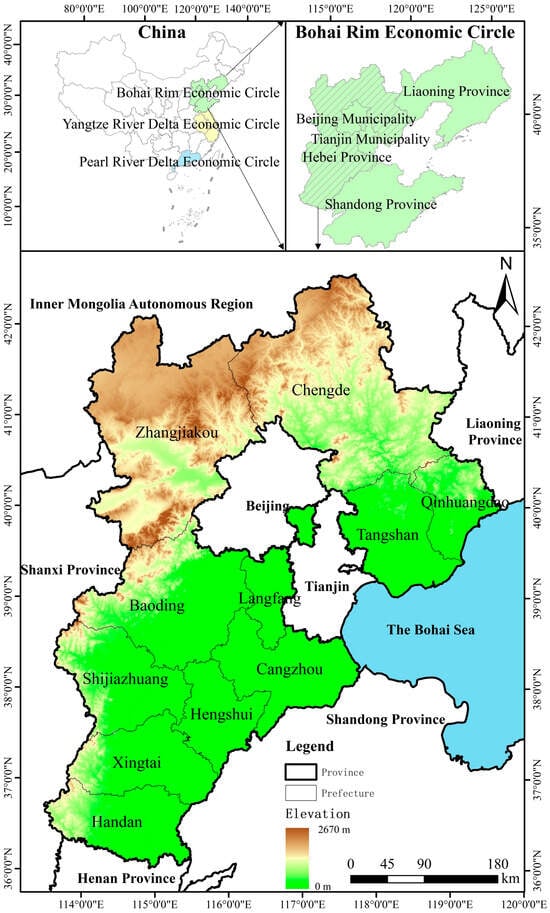

Hebei Province, situated within one of China’s three major urban agglomerations—the Circum-Bohai Sea Region—extends between E 113°27′–119°50′ and N 36°05′–42°40′. Encompassing and encircling the municipalities of Beijing and Tianjin, it serves as the core province of the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei metropolitan area. The province is characterized by a diverse urban landscape, including heavy industrial bases such as Tangshan and Handan, underdeveloped prefecture such as Hengshui and Cangzhou, ecological service-oriented prefectures such as Chengde and Zhangjiakou, and functional relocation hubs such as Langfang and Baoding that accommodate the transfer of non-capital functions from Beijing (Figure 1). Amid rapid industrialization and urbanization, Hebei has faced increasingly severe resource and ecological constraints, marked by heightened pressures on ecosystem services and the dual challenge of pursuing economic transformation while advancing green and sustainable development.

Figure 1.

Geographical configuration of the study area.

2.2. Data Sources and Processing

This study utilized multi-source datasets spanning the period 2005–2020, encompassing Digital Elevation Model (DEM), soil, land use, precipitation, evapotranspiration, depth to bedrock, river and road networks, Points of Interest (POI), socioeconomic statistics, and water resources. The majority of these datasets were acquired from authoritative national scientific data centers, supplemented by official statistical yearbooks and government bulletins, thereby ensuring both reliability and consistency. All raster datasets were resampled to a uniform spatial resolution of 1 km, and all spatial datasets were projected into the WGS 1984 UTM Zone 50N coordinate system (Table 1).

Table 1.

Data source.

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Indicator System Construction

In developing the indicator framework, this study adopts the principle of coordinated development across society, economy, and ecology. Considering Hebei Province’s status as an agricultural region, alongside its dual tasks of industrial transformation and ecological restoration, a systematic, multidimensional, and quantifiable framework comprising 28 indicators was established. The framework encompasses 12 social indicators, 12 economic indicators, and 4 ecosystem service indicators (Table 2).

Table 2.

SDGs-based Socio-Economic Ecosystem Services Evaluation System of indicators and their weights. Note: “+” denotes positive indicators, while “−” denotes negative indicators.

The social development dimension emphasizes basic livelihood security and agricultural productivity, incorporating indicators that reflect fundamental agricultural conditions, such as grain yield and total sown area. Indicators including total power of agricultural machinery and annual livestock numbers capture production efficiency and the level of animal husbandry in rural areas, while fertilizer application intensity reflects the potential ecological pressures arising from farming practices. Healthcare and education indicators—such as the number of hospital beds and physicians per 10,000 people, government expenditure on education, and university enrollment—represent levels of health security and educational equity. The extent of effectively irrigated farmland indicates the capacity for efficient water resource utilization, whereas road area and urban green space serve as measures of living environment quality in terms of infrastructure provision and residential livability.

The economic development dimension encompasses both the overall level of economic productivity and the structural composition of economic growth. Core indicators such as absolute GDP, national fixed asset investment, and total retail sales of consumer goods capture the scale and dynamism of economic activity. The average wage of employed workers and the actual utilization of foreign investment reflect the degree of economic openness and the quality of employment opportunities. With respect to industrial structure, the contributions of the primary, secondary, and tertiary sectors to GDP illustrate the configuration and transformation of the industrial system. Expenditure on science and technology highlights the pivotal role of innovation in driving high-quality development. At the same time, indicators of industrial pollutant discharge—such as industrial smoke and dust emissions and industrial SO2 emissions—serve to evaluate the trade-off between industrial productivity and environmental performance. Finally, sewage treatment volume reflects regional capacity for ecological management and pollution control.

The ecosystem service dimension highlights ecological regulation and sustainability. Key indicators include carbon storage [49], habitat quality [50], soil retention [51], and water yield [52], which collectively provide a comprehensive representation of ecosystem services and their contribution to sustainable regional development as referenced in previous research [53,54]. In this study, these ecosystem service indicators were quantified using the InVEST model, with provided computational procedures available in the official user guide (https://naturalcapitalproject.stanford.edu/software/invest, accessed on 10 September 2025).

2.3.2. Entropy Weight-TOPSIS Method

By integrating the relative strengths and weaknesses of individual indicators, this study employs an improved entropy weight–TOPSIS method [55], which integrates information entropy–based weighting with the Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to an Ideal Solution. This combined framework offers a rigorous and unbiased evaluation mechanism that has seen extensive use in research on regional development and ecological performance. In the entropy weight procedure, indicator importance is derived from their information entropy, representing the variability or dispersion observed among indicators. The weighted decision matrix generated through this step is subsequently processed using TOPSIS, which establishes ideal and anti-ideal reference solutions for the dimensions of social progress, economic development, and ecosystem services. The relative proximity of each assessment unit to these benchmark solutions is then calculated to facilitate ranking and performance differentiation. By simultaneously accounting for the comparative advantages and disadvantages of each indicator, this method enhances both the discriminative capacity and the reliability of the evaluation results. The corresponding formulas are presented below:

In the formula, represents the normalized value of the value of indicator in dimension . refers to the number of dimensions (social progress, economic development, and ecosystem services), while is the number of indicators (12 social progress indicators, 12 economic development indicators, and 4 ecosystem service indicators). is the entropy value of the indicator. represents the normalized matrix. and are the positive and negative ideal solutions for the indicator, respectively. and represent the distances of object from the positive and negative ideal solutions of the dimensions (social progress, economic development, and ecosystem services). indicates the relative closeness coefficient between each dimension and the ideal solution, with a higher value meaning a closer fit to the ideal solution.

2.3.3. Self-Organizing Map

The SOM clustering method [56] is a classical unsupervised neural network approach that integrates nonlinear dimensionality reduction with topology-preserving capabilities. Through a “competition–cooperation” learning mechanism, SOM projects high-dimensional input data onto a low-dimensional regular grid, ensuring that samples with similar distances in the original space remain spatially adjacent on the grid, thereby facilitating visualization and pattern recognition. The SOM architecture consists of grid nodes defined by position and weight vectors. For each input sample, the network first identifies the best matching unit (BMU) through competitive learning; subsequently, under gradually decreasing learning rates and neighborhood radii, the BMU and its neighboring nodes are iteratively adjusted toward the input sample. This process enables the establishment of a global structure at the initial stage and the refinement of local structures in later stages. Compared with traditional linear dimensionality reduction or direct clustering methods, SOM more effectively preserves topological relationships, captures nonlinear manifold structures, and enhances interpretability. Moreover, with the incorporation of batch or mini-batch training and neighborhood smoothing, SOM demonstrates superior robustness and computational efficiency in processing large-scale datasets and noisy inputs. The specific computational procedure is described as follows:

In the equations, denotes an input grid cell (a total of 184,289 grid cells in this study), with representing the normalized values for the social progress, economic development, and ecosystem service, respectively. denotes the weight vector of neuron , initialized randomly. The Best Matching Unit (BMU) is . The neighborhood kernel is Gaussian, and the learning rate is initialized at 0.01 and decays over time.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Spatiotemporal Distribution Characteristics of the Social, Economic, and Ecosystem Service Dimension

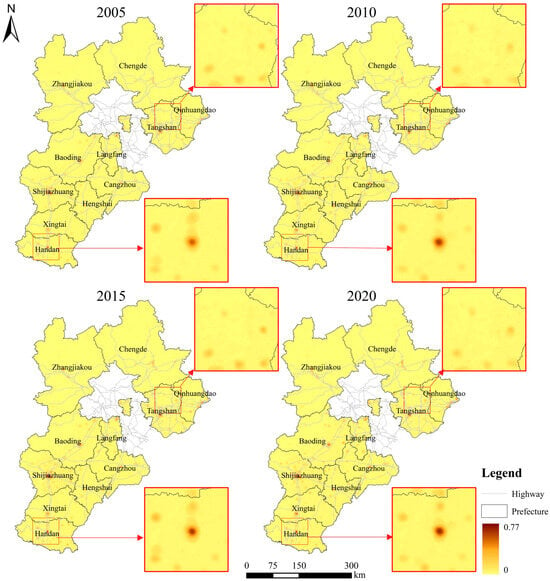

The spatial distribution of social progress in Hebei Province exhibits a “multi-core–belt-shaped” pattern (Figure 2), with high areas in the central districts of Shijiazhuang, Tangshan, and Handan [57], and extending along the high-speed railway corridors of the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei urban agglomeration. This reflects the stronger capacity of well-connected, resource-rich urban clusters to provide and diffuse social services [58,59]. In contrast, the mountainous and remote counties of northwestern Zhangjiakou, northern Chengde, and northwestern Baoding—characterized by complex terrain, limited transportation accessibility, and insufficient public resource investment—have persistently exhibited lagging levels of social progress. This observation aligns with the findings of Wu et al. [60], who highlighted that geographic limitations are a decisive factor influencing social organization in remote mountainous regions. Temporally, the diffusion intensity of social progress across Hebei Province has shown a steady upward trend throughout the study period. Following 2010, the accelerated rollout of the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei coordinated development initiative significantly strengthened the public service capacities of prefecture-level cities such as Cangzhou and Hengshui [61]. By 2020, several areas that had previously demonstrated moderate to low levels of social progress—such as southern Tangshan and parts of Handan—showed substantial improvement, overcoming their earlier lagging status. This result is consistent with the conclusions of Gautam et al. [62], which emphasize the positive effects of coordinated development strategies in strengthening public services in peripheral regions.

Figure 2.

Spatial distribution of social dimension in Hebei Province, 2005–2020.

The spatial distribution of economic development in Hebei Province closely mirrors that of social progress (Figure 3), with high-value areas forming a belt-like pattern along high-speed railway corridors and within the Circum-Bohai Sea Region (Figure 1), reflecting the critical role of transportation networks in fostering regional economic agglomeration [63,64]. Notably, Langfang and Baoding—situated in the core of the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei coordinated development zone—have experienced significantly faster growth than other regions by undertaking industrial transfers from Beijing and Tianjin, supported by favorable policy frameworks and resource spillover effects [27]. Tangshan, underpinned by its traditional industrial base and port infrastructure, has maintained a relatively high level of economic performance. Furthermore, the port economy has stimulated hinterland development, exemplifying the strategic prioritization of coastal development within the broader trajectory of urbanization [65].

Figure 3.

Spatial distribution of economic dimension in Hebei Province, 2005–2020.

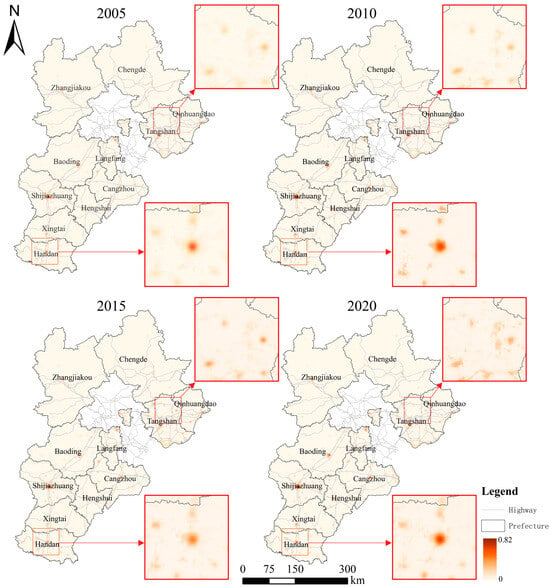

Ecosystem services in Hebei Province exhibit a pronounced mountain–plain contrast, with higher values concentrated in the northwest and northeast and lower values in the southeastern and central regions (Figure 4). This spatial pattern is consistent with the distribution trends identified by Du et al. [66] in ecosystem service assessments. Marked differences are also observed across distinct landforms. As noted by Wang et al. [67], mountainous areas—characterized by steep slopes, limited land development, and well-preserved vegetation—demonstrate stronger capacities for water conservation, carbon sequestration, and soil retention. In contrast, southeastern plain prefectures such as Langfang, Cangzhou, and Hengshui (Figure 1) are dominated by intensive human activities, resulting in significant ecosystem fragmentation and dense land use for urban and agricultural purposes. These pressures have substantially diminished their capacity to provide ecosystem services.

Figure 4.

Spatial distribution of ecosystem services dimension in Hebei Province, 2005–2020.

3.2. SDGs Bundles’ Features

Using the SOM method, a cluster analysis of SDG indicators at the 1 km × 1 km grid scale in Hebei Province was conducted, identifying five distinct types of multi-system synergistic development zones: the low ecosystem service zone, the multidimensional coordinated development zone, the low socioeconomic development lag zone, the moderate ecosystem service zone and the high ecosystem service zone (Table 3). These categories exhibit pronounced differences across the three dimensions of ecosystem services, economic development, and social progress, thereby elucidating the structural composition and coupling relationships of regional multi-system functions.

Table 3.

SDGs bundles features Table.

Within the socio-economic zones—namely the low ecosystem service zone, the multidimensional coordinated development zone, and the low socioeconomic development lag zone—social progress and economic development consistently demonstrate synergistic relationships. However, in both the low ecosystem service zone and the low socioeconomic development zone, these dimensions exhibit weak trade-offs with ecosystem services, whereas the multidimensional coordinated development zone is characterized by balanced advancement across all three dimensions. Specifically, the low ecosystem service zone reflects a pattern in which rapid urbanization occurs at the expense of ecosystem service degradation, resulting in diminished ecological capacity alongside highly concentrated socio-economic development. This outcome corresponds to the widely observed phenomenon of ecological decline under conditions of intensive urban expansion [68,69]. by contrast, the multidimensional coordinated development zone encompasses regions where social progress, economic development, and ecosystem services advance in a harmonized manner. Unlike previous studies that have classified such areas as “urban–rural fringes” or “secondary development zones” [70,71], this typology more accurately captures their comprehensive functionality, providing finer evidence in terms of spatial resolution and functional differentiation. In the low socioeconomic development zone, social progress and economic development lag behind ecosystem services, indicating that these areas remain at an early stage of socio-economic development. Nevertheless, supported by existing ecological protection measures and guided by multidimensional coordinated development, these regions demonstrate potential to transition progressively toward the multidimensional coordinated development zone [72,73].

In contrast to ecosystem service-oriented zones, where both social progress and economic development remain relatively weak (i.e., the moderate ecosystem service zone and the high ecosystem service zone), previous studies have largely identified impoverished or underdeveloped regions on the basis of single economic indicators [74]. By incorporating the ecosystem service dimension, however, this study reveals that although these regions possess favorable ecological conditions, their development is constrained by natural barriers such as limited accessibility and complex topography. Consequently, they exemplify cases in which ecological resources have not been effectively transformed into socio-economic gains [75]. Furthermore, the differentiation between the Moderate and High Ecosystem Service-Oriented Zones establishes a hierarchical framework for more precisely identifying regions endowed with ecological advantages.

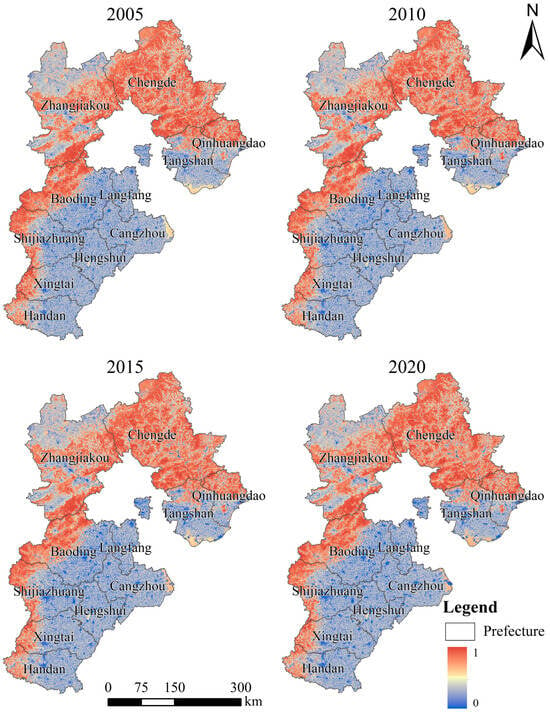

3.3. Spatiotemporal Distribution Characteristics of SDGs Bundles

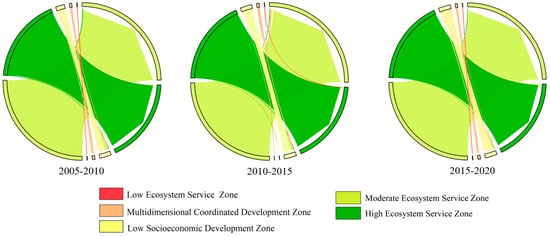

The ecosystem service-oriented zones (i.e., the high and moderate ecosystem service zones) constitute the overall dominant category, followed by the low socioeconomic development zone, the multidimensional coordinated development zone, and the low ecosystem service zone. This hierarchy reflects the strong stability and resilience to external disturbance of regions endowed with favorable ecological conditions [76] (Figure 5). The moderate ecosystem service zone has progressively transitioned into the low socioeconomic development zone under the impetus of initial socio-economic growth, thereby contributing to the expansion of the latter. This trajectory is consistent with the developmental patterns of the social and economic dimensions outlined in Section 3.1. The multidimensional coordinated development zone, shaped by the combined influence of multiple policy interventions—particularly the industrial relocation pressures during the early stages of the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei coordinated development strategy [54] and the implementation of stringent air pollution control measures [77]—has exhibited reciprocal transitions with the low ecosystem service zone.

Figure 5.

Temporal changes in SDGs bundles in Hebei Province, 2005–2020.

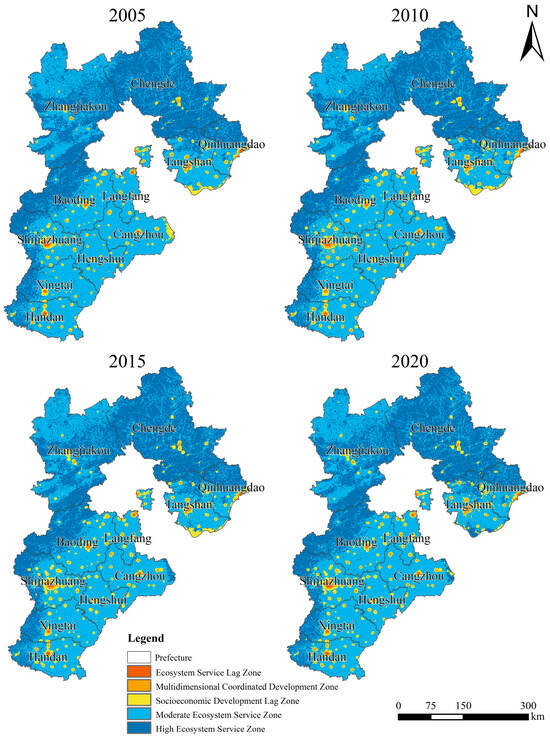

Overall, the socio-economic zones—namely the low ecosystem service zone, the multidimensional coordinated development zone, and the low socioeconomic development zone—exhibit a concentric spatial expansion pattern, radiating outward from urban core areas (Figure 6) and forming a distinct center–periphery distribution. These zones are predominantly situated in densely populated plain regions with advanced urbanization, such as the central districts of Shijiazhuang, Cangzhou, and Langfang. Driven by intensive land reclamation, industrial agglomeration, and highly concentrated infrastructure networks, these areas display comparatively limited ecosystem service performance.

Figure 6.

Spatial distribution of SDGs bundles in Hebei Province, 2005–2020.

The ecosystem service-oriented zones—comprising the moderate and high categories—are characterized by pronounced geomorphological differentiation. The high ecosystem service-oriented zone is predominantly distributed across the mountainous areas of northeastern Hebei Province (Figure 1), where rugged terrain, limited human disturbance, and well-preserved ecosystems contribute to exceptionally high ecological service value but relatively low levels of economic and social development. By contrast, the moderate ecosystem service-oriented zone is primarily located in the transitional areas between low mountains, hills, and plains in the southwest (Figure 1), where ecological service functions are moderate and development potential remains comparatively constrained.

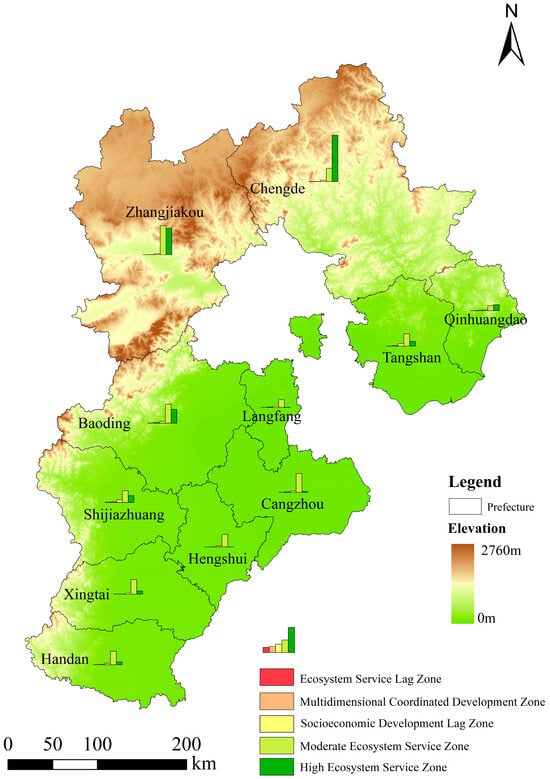

3.4. Comparison of SDGs Bundles Across Different Prefectures

Marked spatial disparities in SDG performance are evident across prefectures in Hebei Province (Figure 7), shaped primarily by the combined influences of topography, industrial structure, and urban functions [78,79,80]. Agriculture-based such as Hengshui and Cangzhou are dominated by moderate ecosystem service zones, with relatively limited representation of low ecosystem service zones. In several mountainous prefectures, including Baoding, Handan, and Xingtai, high ecosystem service zones account for a substantial proportion of the landscape, reflecting their favorable ecological conditions. Chengde and Zhangjiakou, as typical mountainous prefectures, display the most pronounced ecological service advantages, with high ecosystem service zones predominating, although socio-economic development in these areas remains comparatively constrained. By contrast, the provincial capital Shijiazhuang demonstrates the strongest socio-economic development, reflected in the predominance of low ecosystem service zones. Driven by the development of Beijing and Tianjin, Langfang has seen its rural development level rise [81], with a relatively high proportion of socio-economic zones. Meanwhile, Qinhuangdao and Tangshan, supported by port economies and processes of industrial transformation, experienced similar advancements.

Figure 7.

Comparison of SDG Bundles among Prefectures.

Xu et al. [46] ranked the sustainable development of prefectures in Hebei Province from a socio-economic-environmental perspective, with the results being: Shijiazhuang > Baoding > Tangshan. Yang et al. [47], however, pointed out that Langfang had the highest sustainable development indicators, primarily due to differences in the perspective of the selected evaluation indicators and criteria. Nevertheless, both studies indicate that Zhangjiakou and Chengde rank low in sustainable development evaluations, which corresponds to the findings in this research showing that Zhangjiakou and Chengde have a higher proportion of the ecosystem service-oriented zones. And prefectures with higher rankings are generally those with a higher proportion of the socio-economic zones, indicating a strong correlation between the spatial distribution of different bundles and the sustainable development rankings. Unlike studies that measure urban sustainability through composite assessment values [82,83,84], this research further reveals the strengths and weaknesses of prefectures across different dimensions. It also demonstrates the spatial distribution characteristics of various clusters, providing a more precise evaluation of sustainable development.

Among the prefectures of Hebei Province, Shijiazhuang demonstrates the strongest synergy between socio-economic development and ecosystem services, whereas Chengde and Zhangjiakou exhibit the weakest integration across the three dimensions. This divergence highlights the necessity of strengthening functional complementarity among prefectures to optimize regional development. Moving forward, mountainous prefectures such as Chengde and Zhangjiakou should capitalize on their ecological advantages by promoting green ecological tourism and implementing ecological compensation mechanisms to stimulate socio-economic vitality [85]. Economically advanced prefectures such as Shijiazhuang and Tangshan must intensify ecological restoration and accelerate green transformation initiatives to alleviate mounting environmental pressures. Agriculture-based prefectures, including Hengshui and Cangzhou, could enhance the alignment between ecological protection and economic growth through the promotion of efficient agricultural practices, the expansion of green manufacturing, and the adoption of other sustainable strategies. Meanwhile, coastal prefectures such as Tangshan and Qinhuangdao, reliant on port economies, should prioritize marine ecological protection while fostering the development of sustainable and environmentally responsible trade.

3.5. Comparison of Synergies Between Hebei Province and Other Regions

Since 2000, most regions in China have witnessed an overall enhancement in the coupling coordination between socio-economic development and ecological conditions. Nevertheless, pronounced regional disparities persist, with coordination levels generally higher in the southeastern regions than in the northwest [86]. Similarly to developed regions such as the Yangtze Delta [24] and the Pearl River Delta [87], Hebei Province exhibits a “core–periphery” spatial pattern in both socio-economic development and ecosystem services. Urban areas display significantly higher levels of socio-economic development but relatively lower ecosystem service capacity, whereas mountainous regions with favorable ecological conditions are constrained in economic development by factors such as terrain and limited transportation infrastructure. This spatial differentiation parallels the pattern observed in the Yangtze Delta, where central zones of ecological–economic conflict are surrounded by high-coordination areas, and resembles the gradient differences in the Pearl River Delta, where coordination is stronger in the east and weaker in the west. Furthermore, under the influence of policies such as the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei coordinated development strategy, the synergy between socio-economic development and ecosystem services in Hebei has shown marked improvement in certain areas. This trend aligns with regional coordination pathways facilitated by policy interventions in the Yangtze River Delta and the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macao Greater Bay Area.

Hebei Province, while experiencing rapid economic growth and industrial transformation, still lags significantly behind more developed regions in terms of achieving synergy among the three dimensions of social progress, economic development, and ecosystem services. The multidimensional coordinated development zones in Hebei display considerable instability, with frequent dynamic shifts between ecological and economic priorities. These zones are highly sensitive to policy interventions and industrial upgrading, yet they lack the sustained coordination and steady upward trajectories observed in regions such as the Yangtze River Delta and the Pearl River Delta. This contrast underscores the more stable and balanced development achieved in these advanced regions. Moreover, the prevalence of unbalanced states—characterized either by “strong ecosystem services but weak economic development” or by “strong economic development but weak ecosystem services”—remains widespread in Hebei. The continued expansion of low ecosystem service zones in economically developed prefectures such as Shijiazhuang mirrors the situation of resource-based prefectures in Northeast China [28]. In certain areas, despite favorable ecological conditions, socio-economic development remains sluggish, and the pace of transformation is constrained. Although the stability of ecosystem services in Hebei is comparatively stronger than that in Northeast China [35], the lack of sufficient ecological compensation mechanisms and green transformation measures has impeded the emergence of pivotal “node effects.” This contrasts with prefectures such as Guangzhou and Shenzhen in the Pearl River Delta [88], which play a critical role in driving coupling coordination through such mechanisms.

Hebei Province remains in the exploratory stage of coordinating socio-economic development with ecosystem services, with its spatial patterns and evolutionary pathways displaying marked periodicity and strong regional differentiation. Looking ahead, it will be essential to integrate regional ecological conditions with the characteristics of local industrial structures, thereby enhancing the synergy between socio-economic growth and ecosystem services in a context-specific manner. By drawing on the experiences of more developed regions in green transformation, ecological compensation, and industrial upgrading, Hebei can progressively advance toward sustainable and coordinated regional development.

4. Conclusions

This study established a multidimensional and comprehensive evaluation framework for SDGs, integrating three core dimensions: social progress, economic development, and ecosystem services. The entropy-weighted TOPSIS method was employed for overall assessment, while the SOM method was applied to the 1 km × 1 km grid of Hebei Province to systematically generate SDG bundles, thereby revealing the synergies between socio-economic development and ecosystem services from 2005 to 2020. The results indicate that the socio-economic dimension exhibits a “multi-core, belt-shaped” spatial pattern, with high-value areas concentrated in city centers and along major transportation corridors. The diffusion of social services is facilitated by convenient transportation networks and the concentration of public resources, whereas economic development has been stimulated by industrial relocation and locational advantages. In contrast, ecosystem services display a spatial pattern of “higher in mountainous areas and lower in plains,” reflecting the combined influences of topography and human activity intensity. The five SDG bundles identified through the SOM method reveal the dynamic evolution of socio-economic development and ecosystem services under the combined effects of urban expansion, industrial relocation, and ecological protection. Socio-economic clusters demonstrate a concentric expansion from urban cores to peripheral areas, while ecosystem service clusters show a pronounced “mountain–plain” differentiation. The evolution of functional types and inter-city spatial disparities is evident, with the overall trend suggesting a developmental trajectory characterized by stable ecological conditions alongside the gradual expansion of low socio-economic development zones.

Guided by SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), SDG 13 (Climate Action), and SDG 15 (Life on Land), Hebei Province should enhance inter-city coordination, functional complementarity, and the efficiency of factor flows to promote balanced improvements in social, economic, and ecosystem services. On the one hand, strengthening industrial coordination and the sharing of public services between urban and rural areas is essential for narrowing development gaps in socially and economically lagging regions. On the other hand, it is crucial to preserve the ecological advantages of mountainous areas by establishing ecological barrier zones and high-value ecosystem service corridors, thereby providing stable ecological support for high-quality regional development. By implementing differentiated and functionally oriented regional strategies based on spatial heterogeneity, Hebei Province can accelerate progress toward the inclusive, coordinated, and ecologically resilient development pathways emphasized by the SDGs.

The SDGs bundle identification method proposed in this study, based on the socio-economic ecosystem services framework, exhibits high operational feasibility and reproducibility. This method quantifies various dimensions of social, economic, and ecosystem services at the kilometer grid scale, identifies distinct SDGs bundles, and thereby reveals synergies among these dimensions. Due to its flexibility and versatility, this framework can be widely applied to other regions, providing a scientific basis for adjusting and optimizing regional governance policies. It assists policymakers in gaining a more precise understanding of the current state of socioeconomic conditions and ecosystem services within a region, offering robust support for achieving sustainable development goals.

Due to data limitations, this study assumes that all socioeconomic data are uniformly distributed within units, considering only the proportionate allocation of grid-level and city-level data. This may introduce some error into the results. Furthermore, the study did not sufficiently consider the comprehensiveness and continuity of indicators when selecting them. Future research can extend this framework to different geographic regions and socioeconomic contexts, conducting comparative analyses across regions and scales to develop more precise, tailored sustainable development strategies for each area. Simultaneously, dynamic evolutionary analysis and forecasting using time-series data can effectively track changes in SDG clusters, providing forward-looking guidance for regional policy adjustments. Furthermore, research should refine the indicator system to comprehensively evaluate sustainable development across regions, particularly when confronting dual challenges of ecological pressures and socioeconomic development. By integrating climate change and carbon neutrality scenarios, it should explore how to balance these dual imperatives, deepen understanding of regional development mechanisms and sustainable pathways, and provide more targeted decision support for advancing high-quality coordinated regional development and sustainable growth.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.C. and Q.Z.; methodology, Q.C., J.T. and L.S.; Conceptualization, Q.C., Q.Z. and K.Z.; methodology, Q.C., J.T. and L.S.; software, Q.C., J.T. and L.S.; validation, Q.C., Y.L., G.Q. and S.L.; formal analysis, L.S. and Q.Z.; data curation, Q.C., Y.L., G.Q. and S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.C.; writing—review and editing, Q.C., Y.L., G.Q., J.T. and S.L.; supervision, Q.Z. and K.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Science and Technology Planning Project of Hebei Academy of Sciences (25103) and Jing-Jin-Ji Regional Integrated Environmental Improvement-National Science and Technology Major Project (2025ZD1205000).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lee, B.X.; Kjaerulf, F.; Turner, S.; Cohen, L.; Donnelly, P.D.; Muggah, R.; Davis, R.; Realini, A.; Kieselbach, B.; MacGregor, L.S. Transforming our world: Implementing the 2030 agenda through sustainable development goal indicators. J. Public Health Policy 2016, 37 (Suppl. S1), 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colglazier, W. Sustainable development agenda: 2030. Science 2015, 349, 1048–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bălăceanu, C.-T.; Tăbîrcă, A.-I.; Radu, F.; Tilea, D.-M.; Radu, V.; Drăgulescu, I. Pragmatism in Eco-Economy and Social Influence in Environmental Policy Management. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerni, P. Innovation in times of crisis: A pragmatic and inclusive approach to cope with urgent global sustainability challenges. Front. Environ. Econ. 2025, 4, 1498138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamash, A.; Iyiola, K.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. The Role of Circular Economy Entrepreneurship, Cleaner Production, and Green Government Subsidy for Achieving Sustainability Goals in Business Performance. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, M.A. Energy sustainability: A pragmatic approach and illustrations. Sustainability 2009, 1, 55–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loman, O. A problem for environmental pragmatism: Value pluralism and the sustainability principle. Contemp. Pragmatism 2020, 17, 286–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, S.; Farioli, F.; Zamagni, A. Progress in sustainability science: Lessons learnt from current methodologies for sustainability assessment: Part 1. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2013, 18, 1653–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, M.; James, P.; Klinkers, L. Sustainable Measures: Evaluation and Reporting of Environmental and Social Performance; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gehringer, A.; Kowalski, S. Mapping Sustainability Measurement. Cham: Springer Nat. Switz. Access Date 2023, 29, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, S.; Lyu, Y.; Wang, J.; Shi, X. Addressing Environmental Health Challenges for Sustainable Development in China. China CDC Wkly. 2023, 5, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eliazar, I.; Cohen, M.H. On social inequality: Analyzing the rich–poor disparity. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2014, 401, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotsulyak, I.; Ivanova, N.; Rudaleva, I.; Markova, S. Social inequality in environment of economic growth. In Proceedings of the International Conference “ Economy in the Modern World” (ICEMW 2018), Kazan, Russia, 26–27 July 2018; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 328–332. [Google Scholar]

- Aghayeeabianeh, B. The Role of Social and Economic Inequality in Shaping Antisocial Personality Traits. Ment. Health Prev. 2025, 37, 200400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, S.; Deichmann, U.; Meisner, C.; Wheeler, D. Where is the poverty–environment nexus? Evidence from Cambodia, Lao PDR, and Vietnam. World Dev. 2005, 33, 617–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafik, N.; Bandyopadhyay, S. Economic Growth and Environmental Quality: Time-Series and Cross-Country Evidence; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 1992; Volume 904. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman, D.S.; de Bruyn, S.M. Probing into the environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis. Ecol. Econ. 1998, 25, 143–145. [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson, L.H.; Holling, C.S. Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science 2009, 325, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassl, M.; Löffler, J. Ecosystem services in coupled social–ecological systems: Closing the cycle of service provision and societal feedback. Ambio 2015, 44, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostrom, E.; Cox, M. Moving beyond panaceas: A multi-tiered diagnostic approach for social-ecological analysis. Environ. Conserv. 2010, 37, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Fang, C.; Zhang, Q. Coupling coordinated development between social economy and ecological environment in Chinese provincial capital cities-assessment and policy implications. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, B.; Chu, C.-j.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.-t.; Yang, S.-h.; Wang, Q. Assessing the coordinate development between economy and ecological environment in China’s 30 provinces from 2013 to 2019. Environ. Model. Assess. 2023, 28, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Fang, C.; Cheng, S.; Wang, J. Evolution of coordination degree of eco-economic system and early-warning in the Yangtze River Delta. J. Geogr. Sci. 2013, 23, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Qiao, Y.; Shi, T.; Zhou, Q. Study on coupling coordination and spatiotemporal heterogeneity between economic development and ecological environment of cities along the Yellow River Basin. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 6898–6912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, H.; Cao, Y. Research on the coordinated development of economic development and ecological environment of nine provinces (regions) in the Yellow River Basin. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yang, W. Coordinated Development Strategy of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region and Regional Economic Convergence. SHS Web Conf. 2023, 163, 01025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yi, P.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, Y. Assessment of coordinated development between social economy and ecological environment: Case study of resource-based cities in Northeastern China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 59, 102208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhu, T.; Guo, H.; Yang, X. Analysis of the coupling coordination degree of the Society-Economy-Resource-Environment system in urban areas: Case study of the Jingjinji urban agglomeration, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 146, 109851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yang, L.; Sun, K.; Zhu, J. Synergistic security relationships and risk measurement of water resources-social economy-ecological environment in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 175, 113512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Ma, R.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Guo, J.; Li, C.; Zhou, W. Identifying the trade-offs and synergies of land use functions and their influencing factors of Lanzhou-Xining urban agglomeration in the upper reaches of Yellow River Basin, China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, J. Nexus between ecological conservation and socio-economic development and its dynamics: Insights from a case in China. Water 2020, 12, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamatov, A.; Maltsev, Y.; Pavlov, N. Region innovative development in the Russian economy technological transformation: Ecosystem approach. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 258, 12004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Wang, J.; Chen, K. Coordinated development analysis of the “resources-environment-ecology-economy-society” complex system in China. Sustainability 2016, 8, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Fan, Z.; Feng, W.; Yuxin, C.; Keyu, Q. Coupling coordination degree spatial analysis and driving factor between socio-economic and eco-environment in northern China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 135, 108555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, K.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y. Investigating the coupled coordination of improved ecological environment and socio-economic development in alpine wetland areas: A case study of southwest China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 160, 111740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Zheng, X.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H. Coupling Coordination Development of the Ecological–Economic System in Hangzhou, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renard, D.; Rhemtulla, J.M.; Bennett, E.M. Historical dynamics in ecosystem service bundles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 13411–13416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiksel, J. Sustainability and resilience: Toward a systems approach. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2006, 2, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, M.; Chisholm, E.; Griggs, D.; Howden-Chapman, P.; McCollum, D.; Messerli, P.; Neumann, B.; Stevance, A.-S.; Visbeck, M.; Stafford-Smith, M.J.S.S. Mapping interactions between the sustainable development goals: Lessons learned and ways forward. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 1489–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Huang, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, X. Spatial identification of restored priority areas based on ecosystem service bundles and urbanization effects in a megalopolis area. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 308, 114627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Z.J.N.; Yang, Y. Trade-offs and synergies of ecosystem services in the Northeast region based on service clusters. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2020, 40, 2827–2837. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, P.J.F.; Wu, J. Study on the spatiotemporal evolution trajectory of ecosystem services in Shenzhen based on ecosystem service clusters. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2020, 40, 2545–2554. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Xie, B.; Zhou, K.; Li, J.; Yuan, C.; Xiao, J.; Xie, J. Mapping ecosystem service clusters and exploring their driving mechanisms in karst peak-cluster depression regions in China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Zheng, X.; Li, T.; Zhang, L.; Lu, Y. Urban Functional Interaction Patterns and Governance Strategies of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Urban Agglomeration. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2022, 77, 1374–1390. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Xie, N.; Wu, L. Evaluation on sustainable development of 11 regions in Hebei province. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 14189–14203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Yang, H.; Wang, H. Evaluating urban sustainability under different development pathways: A case study of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 61, 102226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, F.; Yu, X. Coupling analysis of urbanization and ecological total factor energy efficiency—A case study from Hebei province in China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 74, 103183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Guo, B.; Wang, C.; Zang, W.; Huang, X.; Wu, Z.; Xu, M.; Zhou, K.; Li, J.; Yang, Y. Carbon storage simulation and analysis in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region based on CA-plus model under dual-carbon background. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2023, 14, 2173661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. Evolution of habitat quality and association with land-use changes in mountainous areas: A case study of the Taihang Mountains in Hebei Province, China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 129, 107967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Long, Y.; Liang, W.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y. Analysis of Soil retention service function in the North Area of Guangdong based on the InVEST model. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Changsha, China, 18–20 September 2020; p. 032011. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Hou, X.; Cao, J. Identifying the driving impact factors on water yield service in mountainous areas of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region in China. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, P.; Chen, W.; Hou, Y.; Li, Y. Linking ecosystem services and ecosystem health to ecological risk assessment: A case study of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urban agglomeration. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 636, 1442–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Jin, X.; Chen, T.; Wu, J. Understanding trade-offs and synergies of ecosystem services to support the decision-making in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region. Land Use Policy 2021, 106, 105446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Luo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Fan, G.; Zhang, J. Suitability evaluation system for the shallow geothermal energy implementation in region by Entropy Weight Method and TOPSIS method. Renew. Energy 2022, 184, 564–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neagoe, V.-E.; Ropot, A.-D. Concurrent self-organizing maps for pattern classification. In Proceedings of the Proceedings First IEEE International Conference on Cognitive Informatics, Calgary, AB, Canada, 19–20 August 2002; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 304–312. [Google Scholar]

- Zaborovskaya, O.V.; Gorovoy, A.A. Allocation Of Regional Social Infrastructure Objects As A Factor Of Integrated Area Development. J. Int. Sci. Publ. Econ. Bus. 2015, 9, 422–432. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Liu, M.; Hu, Y.; Shi, T.; Qu, X.; Walter, M.T. Effects of urbanization on direct runoff characteristics in urban functional zones. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 643, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L. Study on treatment effects and spatial spillover effects of Beijing–Shanghai HSR on the cities along the line. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2021, 67, 671–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y. What constrains impoverished rural regions: A case study of Henan Province in central China. Habitat Int. 2022, 119, 102477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhang, C.; Tan, Q. Factors influencing the coordinated development of urbanization and its spatial effects: A case study of Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, A. Role of coordination in effective public service delivery system. J. Public Adm. Gov. 2020, 10, 158–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Li, W.; Song, H.; Yue, H. Analysis on the difference of regional high-quality development in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei city cluster. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 199, 1184–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Chang, W.; Song, M.; Zhu, H. Measurement of Urban–Rural Integration Development Level and Diagnosis of Obstacle Factors: Evidence from the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Urban Agglomeration, China. Land 2025, 14, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Li, G. Empirical study on effect of industrial structure change on regional economic growth of Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Metropolitan Region. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2011, 21, 708–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, P.; Li, J.; Yu, S. Ecological compensation in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region based on ecosystem services flow. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 331, 117230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Liu, L.; Yin, L.; Shen, J.; Li, S. Exploring the complex relationships and drivers of ecosystem services across different geomorphological types in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region, China (2000–2018). Ecol. Indic. 2021, 121, 107116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajjar, V.; Sharma, U. Relevance of urban ecosystem services for sustaining urban ecology in cities-a case study of Ahmedabad City. In Innovating Strategies and Solutions for Urban Performance and Regeneration; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 233–246. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Responses of Ecosystem Services to Land Use/Cover Changes in Rapidly Urbanizing Areas: A Case Study of the Shandong Peninsula Urban Agglomeration. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Tian, M.; Li, P. Coordinated development of urbanization and ecosystem services in Tibet Autonomous Region. Prog. Geogr. 2023, 42, 1947–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Zhao, J.; Lin, Y.; Chen, G. Coupling and coordination relationship of economic–social–natural composite ecosystem in central Yunnan urban agglomeration. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaeva, E.; Magomadova, M.; Abalakin, A.; Abalakina, T. Internal and External Components Of The Socio-Economic Regional Development. In Proceedings of the SCTCGM 2018—Social and Cultural Transformations in the Context of Modern Globalism, Grozny, Russia, 1–3 November 2019; European Proceedings of Social Behavioural Sciences: Cyprus, Russia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Komornicki, T.; Czapiewski, K. Economically Lagging Regions and Regional Development—Some Narrative Stories from Podkarpackie, Poland. In Responses to Geographical Marginality and Marginalization: From Social Innovation to Regional Development; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 65–83. [Google Scholar]

- Wau, T. Economic growth, human capital, public investment, and poverty in underdeveloped regions in Indonesia. J. Ekon. Studi Pembang. 2022, 23, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhalsaraeva Ekaterina Alexandrovna, D.M.A.; Vyacheslavovna, S.A. Ecological limitations of spatial development in the practice of Russian regions. Her. Plekhanov Russ. Univ. Econ. 2019, 6, 32–42. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, J.; Wang, G.; Yu, R.; Su, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Fang, Q. Investigating the regional ecological environment stability and its feedback effect on interference using a novel vegetation resilience assessment model. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 930, 172728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Tibet Network. Joint Submission by Member Groups of the International Tibet Network to Session 17 of Universal Periodic Review—People’s Republic of China (UPR-17, China). UPR-Info. 2013. Available online: https://upr-info.org/sites/default/files/documents/2013-12/js14_upr17_chn_e_main.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Chen, S.; Huang, Q.; Liu, Z.; Meng, S.; Yin, D.; Zhu, L.; He, C. Assessing the regional sustainability of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urban agglomeration from 2000 to 2015 using the human sustainable development index. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Feng, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, K. Progress toward some of sustainable development goals in China’s population-shrinking cities. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 448, 141672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Li, Z.; Cui, X.; Zhao, M.; Shi, Y.; Lin, H.; Zhu, T. Analysis of sustainable spatial structure of cities under the framework of “Economy-Society-Environment”: A case study Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urban agglomeration. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 173, 113416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Liang, L.; Wang, Z. Quantitative simulation and verification of upgrade law of sustainable development in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urban agglomeration. Sci. China Earth Sci. 2019, 62, 2031–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strezov, V.; Evans, A.; Evans, T.J. Assessment of the economic, social and environmental dimensions of the indicators for sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 25, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J.; Zhang, L.; Chen, B.; Liao, J.; Hashim, M.; Sutrisno, D.; Hasan, M.E.; Mahmood, R.; Sani, D.A. Assessment of coastal sustainable development along the maritime silk road using an integrated natural-economic-social (NES) ecosystem. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Liu, X.; Li, F.; Tao, Y.; Song, Y. Comprehensive evaluation of different scale cities’ sustainable development for economy, society, and ecological infrastructure in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 163, S329–S337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liang, L.; Sun, Z.; Wang, X. Spatiotemporal differentiation and the factors influencing urbanization and ecological environment synergistic effects within the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urban agglomeration. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 243, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Xu, T.; Shi, L. Analysis on sustainable urban development levels and trends in China’s cities. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 868–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Z.; Ge, Q.; Zhang, L. Research on the Spatial Correlation Pattern of Sustainable Development of Cities in the Yangtze River Delta Region of China, Based on the Dynamic Coupling Perspective of “Ecology-Economy”. Systems 2025, 13, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Luo, H. Mismatch and coupling: A study on the synergistic development of tourism-economy-ecology Systems in the Pearl River Delta. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).