Abstract

Purpose: The research explores the impact of change management practices—leadership support, employee involvement, and regulatory compliance —on the practice of sustainable healthcare in Saudi Arabia. Operational efficiency is treated not as a management practice but as a key outcome of effective change management. The research also examines patient readiness as a mediator influencing awareness, participation, and satisfaction. Design/methodology/approach: The study used a quantitative Saudi Arabian healthcare consumer survey. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was used to analyze change management, patient readiness, and sustainable healthcare relations adoption. Findings: Findings indicate that change management plays a strong role in increasing patient adoption (β = 0.322; p = 0.083), but with large effects on awareness (β = 0.873; p < 0.001), engagement (β = 0.841; p < 0.001), and satisfaction (β = 0.881; p < 0.001), as adoption reflected through awareness, engagement, and satisfaction. Patient readiness as a mediator was significant with strong effects between change management and adoption (β = 0.571; p < 0.001). Originality/value: This research expands the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) by synthesizing it with strategic change management to predict patient readiness as a mediator of long-term adoption of healthcare in the Arab environment. Patient readiness is hypothecated as an observable behavioral construct to mediate organizational change practices—leadership, communication, and regulation—with individual adoption outcomes. The research provides theoretical and practical contributions for evidence-based healthcare policy and patient-led healthcare revolution. In addition, the study conforms with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) including SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure), and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), and shows how effective change management not only assists national healthcare reforms but also global sustainability goals.

1. Introduction

The world’s drive towards sustainable healthcare is a reflection of countries’ attempts to align the health system with the agendas of social and environmental sustainability [1]. Saudi Arabia has been one of the first reformists in this regard with its Health Sector Transformation Program under its Vision 2030, which seeks to enhance infrastructure, incorporate digital health, and involve the private sector to enhance the quality and availability of services [2]. One of the highlight examples is the SEHA Virtual Hospital, inaugurated in 2022 and rated as the world’s largest virtual hospital [3]. Linking more than 150 hospitals and providing more than 30 premium digital services—remote consultations, diagnostics, and tele-intensive care included—it is the backbone of Saudi Arabia’s digital health policy and the fulfillment of Vision 2030 healthcare aspirations [4,5].

Despite all these achievements, significant knowledge gaps about patient attitudes, readiness, and participation in sustainable health programs [6] remain. To the extent that SEHA and similar interventions increased health access, their effect on environmental sustainability and their impact on individual-level behavior has not been rigorously explored [7]. Most of the recent research is centered on institutional and technological drivers of sustainable healthcare change, and little has been written on how patients themselves experience change, implement, and maintain it—especially for Saudi and Arab environments [8]. It is crucial to address this gap in order to ensure that healthcare reform ensues with not just systemic change but patient-centered sustainability.

Globally, empirical evidence suggests that change management frameworks involving leadership endorsement, workforce engagement, and regulatory drive deliver effective shifts towards sustainable healthcare [1,2,3]. Empirical evidence in Saudi hospitals reaffirms institutional and leadership preparedness supports adoption of digital health [2], and workforce engagement reduces resistance and enhances sustainability performance [3,4]. The same is true for Asia and Europe where effective change management executed enhances operational efficiency, workforce resilience, and patient satisfaction [5,6,7]. Yet, the existing literature predominantly takes an organizational lens, losing sight of the psychological and behavioral mechanisms by which patients translate institutional shifts to individual health behavior [6,8]. This research bridges that gap by critically exploring how change management practices influence patient readiness and hence sustainable uptake of healthcare in the context of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030.

Saudi Arabia’s health revolution also resonates with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure), SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), and SDG 13 (Climate Action). Projects like the SEHA Virtual Hospital are a prime example of how digitalization, energy efficiency, and green operations can be made to ensure national development and international pledges for sustainability.

For purposes of this research, sustainable healthcare is the delivery of care that balances patient quality results, environmental responsibility, and financial sustainability through digitalization, resource planning, and green innovation [6]. Strategic change management is systematic planning, execution, and assessment of reforms to align healthcare organizations with long-term sustainability objectives, with a focus on leadership commitment, employee engagement, and compliance regulation [2].

On this basis, the research investigates change management practices impacting patient engagement and adoption of sustainable healthcare in Saudi Arabia. Current literature has cited leadership and organizational readiness as the key, yet empirical tests are lacking on patients’ emotional and behavioral reactions to the same [8]. This study introduces patient readiness as a construct with multiple dimensions like recognition of the necessity to change cognition, emotional acceptance of practice change, and behavioural willingness to change. It is also influenced by trust in healthcare professionals, ICT literacy, and environmental mind-set, as an intervening variable between organizational planning and take-up outcomes at the individual level [9,10,11,12].

Previous research has analyzed organizational readiness (institutional capacity, leadership alignment) and technology readiness (user capability and system acceptance) [6,7,8], but patient readiness is a unique, behavior-based construct. It contrasts with previous models in that it specifies individuals’ emotional and psychological readiness to embrace systemic change and act in accordance with sustainability principles. Therefore, patient readiness broadens adoption frameworks like the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT), and Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) to include the human adjustment factor—how individuals convert organizational change signs into long-term behavioral commitment. This theoretical separation makes patient readiness a new mediator between change management and sustainable healthcare adoption in Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030.

Hence, this study attempts to answer the following research questions:

- 1.

- Does the implementation of change management strategy influence patient adoption in Saudi Arabia?

- (1a) Does implementation influence patient awareness?

- (1b) Does implementation influence patient engagement?

- (1c) Does implementation influence patient satisfaction?

- 2.

- Is patient readiness for change a mediator of change management implementation and patient adoption of sustainable healthcare?

In this framework, patient adoption is the outcome measure—encompassing awareness, participation, and satisfaction—and patient readiness is the mediating construct. In spite of worldwide progress toward sustainable healthcare, evidence within the Arab context has been scant. This research contributes by presenting patient-level data for Saudi Arabia, demonstrating how leadership, communication, and regulatory systems drive participation and satisfaction through readiness. The findings offer sound recommendations to healthcare managers and policymakers to facilitate the achievement of Vision 2030’s goals through digitalization, environmental sustainability, and sustainable healthcare in the long term.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Background

2.1. Strategic Change Management and Sustainable Healthcare

Shifting towards sustainable healthcare involves an integrated change management process that aligns institutional processes, human capital, and technology to long-term sustainability objectives [11]. Across the world, healthcare organizations have increasingly been embracing sustainability-driven models including digital transformation, optimal utilization of resources, and ecologically compatible operational systems aimed at reducing environmental footprint and improving the quality of service [12,13]. Leadership commitment, staff involvement, adherence to regulations, and technology-enabled delivery are the key strategic elements which are pillars in taking up successful transformation [14,15]. But their adoption depends on the country, based on infrastructure capacity, culture, and regulatory stringency [16].

Systematic empirical evidence in Europe, North America, and Asia all point to the fact that well-defined change management models accelerate the uptake of sustainability, enhancing efficiency and patient outcomes [17,18,19,20].

At a global level, Vision 2030 in Saudi Arabia is an inspiring environment to explore the dynamics between organizational change strategies and patient-level implementation [5,21]. Leadership commitment is now the key to success: CEOs prioritizing sustainability, investing funds, and holding someone accountable can make change a reality [17,18,19,20]. Or leadership resistance and budget limitations instead impair progress unless appeased with focused training and ingrained sustainability goals [22,23,24,25].

Equally, commitment of staff defines the extent to which sustainability initiatives are internalized. Empirical data indicate that participative staff involvement, staff development, and joint decision-making lower resistance as well as increase policy acceptance [24,25,26,27]. Saudi research underlines that participative management frameworks as well as reward systems ensure staff motivation but must be complemented by ongoing education to defeat well-established resistance [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40].

Effective patient communication reinforces these interventions to make change familiar, believable, and acceptable at a cultural level [41,42,43]. In Saudi Arabia, cultural and linguistic differences between expatriate health care providers and home patients [14,21,29,44] exist, and therefore once more, problems with communication are maintained. Therefore, culture-specific models of communication and cultural competence training are necessary for sustainability-driven care provision.

Operational efficiency, the common result of change management, is not a by-product but a deliberate force behind sustainability. Lean processes, streamlined workflows, and electronic patient records reduce waste of carbon and resources [12,13,14,15,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56]. Process improvement equates to increased organizational performance and patient satisfaction. This is complemented by environmental training schemes that increase the environmental literacy and compliance behavior of healthcare professionals with sustainable standards [45,46,47,48,49]. Ultimately, compliance with regulation—dependent upon national policy settings and health authority standards—creates structural incentives for institutional compliance and learning [57,58,59,60,61,62].

Together, these dimensions—leadership, engagement, communication, efficiency, training, and regulation—are the strategic support framework that guides effective healthcare transformation. But it always hinges on how well patients internalize and react to such changes in the organization.

2.2. Patient Adoption of Sustainable Healthcare

From a behavioral point of view, patient uptake is the degree to which individuals take up sustainable healthcare practice—i.e., electronic consultation and environmentally friendly behavior—into care habits [33]. Adoption is expressed in terms of interconnected determinants: awareness (knowledge and familiarity with sustainability practice) [35], engagement (active use and ongoing use) [38], and satisfaction (self-confidence, quality of the service, and perceived efficiency) [40]. They dynamically interact with each other: awareness leads to engagement, engagement affects satisfaction, and satisfaction maintains long-term adoption [63,64,65,66,67,68].

While global research into the determinants of sustainability focuses on institutional and technological factors, there are few that explore the effect of patient attitudes on adoption behavior, particularly in Gulf healthcare systems [8]. Global evidence attests to increased uptake of sustainable healthcare through education and awareness of patients [69,70,71,72]. Likewise, electronic engagement processes including telemedicine and mobile health applications increase convenience but with reduced environmental effect [73,74,75,76,77,78]. In Saudi Arabia, flagship initiatives such as SEHA Virtual Hospital have improved access to healthcare but persistent digital literacy issues, especially among the rural population, continue to restrain inclusiveness [73,74,79,80].

Moreover, patient satisfaction on the basis of perceived quality, trust, and convenience is the key to long-term uptake [81,82,83,84]. Nevertheless, considerable concerns regarding data privacy, cultural assumptions, and perceived complexity may weaken patients’ enthusiasm to participate. Adoption of sustainable healthcare by patients is thus reliant not merely on technological readiness but also on social trust and context-dependent engagement strategies aligned with national culture.

2.3. Patient Readiness for Change

Patient readiness for change reflects a person’s emotional, psychological, and behavioral willingness to adopt change in new health practice [85,86,87,88]. It combines perceived need for change, emotional openness, intention to act, and enablement factors such as self-efficacy, trust, digital capability, and orientation to the environment [89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117]. International evidence still indicates readiness will be an intermediary in organizational action to individual action change—enabled, supported, and confident patients are much more likely to maintain actions [90,91,92,93,94,95,96].

In Saudi Arabia, proactive reform under Vision 2030 emphasizes the importance of preparedness. Alongside expanded health care and innovation, gaps in digital literacy and education among older and rural communities are persistent impediments [101,102,103,104,118,119,120]. Leadership training, employee participation, and patient communication lay the groundwork for empowerment but necessitate internal preparedness for behavioral modification—patients need to be convinced of worth, doability, and safety [23,33,56]. Hence, readiness becomes the intervening process that connects organizational strategies to adoption performance according to behavior theories like the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), where perceived behavioral control is at the center of intention formation [23,33,56].

Readiness is measured in this research through four dimensions:

- Perceived need for change—awareness of patients about the importance of sustainable healthcare practices [92,93,94,95,96];

- Emotional readiness—ease and familiarity with adopting digital and sustainable solutions [97,98,99,100];

- Behavioral readiness—willingness to change habits and routines with proper tools [105,106,107];

- Readiness enablers—self-efficacy, trust in providers, digital literacy, and pro-environmentalism [53,102,113,114,115,116,117].

National programs—mainly e-health literacy promotions and sustainability awareness programs—have boosted readiness among younger, urban populations [46,118,119,120]. But to allow for equitable adoption, efforts must address readiness gaps on demographic and geographic foundations.

2.4. Adoption and Engagement Outcomes

Synthesizing the evidence, it is clear that organizational change management—encompassing leadership, employee engagement, communication, training, operational efficiency, and regulatory oversight—is argued to bring about the structural preconditions for sustainable transformation in healthcare [11,12,13,14,15,16,24,25,26,27,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68]. The transformation, however, only takes root when patients’ readiness mediates between these organizational effects, leading to adoption of behavior as defined by awareness, engagement, satisfaction, and continuity of use. Although there has been extensive theoretical elaboration in international settings, empirical evidence for this mediating process in Arab healthcare systems is very rare [8].

The current research fills this void by developing a cross-level conceptual framework in which patient readiness is the mediator between the organizational (change management) and individual (adoption) levels. Synthesizing TAM/UTAUT and behavioral theory (TPB), the framework brings an insight into how strategic change processes are communicated as tangible patient behaviors in the Saudi Arabia Vision 2030 setting—a reality characterized by accelerated digitalization and robust policy imperatives.

2.5. Empirical Literature Review

Empirical research on change management and sustainable healthcare in Saudi Arabia is limited but converging with Vision 2030 priorities. Quantitative studies emphasize that the greatest determinants of employee acceptance and operational performance are commitment by leadership and transparent communication [118,119,120].

For example, [121] showed that digital transformation programs such as SEHA Virtual Hospital improved specialist service access substantially but did not necessarily lead to patient realization of benefits from sustainability. Parallel studies by [122] found organizational readiness at moderate levels and emphasized training gaps as ongoing obstacles to effective implementation.

Qualitative and mixed-method research add further depth of understanding regarding the patient aspect. Reference [123] concluded that most sustainability initiatives are viewed as top-down, restricting participation and ownership among staff and patients. Reference [124] also identified emotional readiness and perceived quality of the service as predictors for sustained behavioral uptake.

Taken together, these results indicate that while Saudi Arabia has made significant institutional development, patient responsiveness continues to be a factor that determines the long-run sustainability of reforms. The results lend credence to this research’s general thesis—that patient willingness to adapt is the intervening mechanism through which strategic change management enhances sustainable healthcare uptake.

From the previous discussion authors can develop the following hypotheses:

H1.

The implementation of change management strategies for sustainable healthcare has a strong impact on patient adoption in Saudi Arabia.

H1a.

The implementation of change management strategies for sustainable healthcare positively affects patient awareness in Saudi Arabia.

H1b.

The implementation of change management strategies for sustainable healthcare significantly influences patient engagement in Saudi Arabia.

H1c.

The implementation of change management strategies for sustainable healthcare strongly stimulates patient satisfaction in Saudi Arabia.

H2.

Patient readiness for change mediates the effect of the implementation of change management strategies for sustainable healthcare and patient adoption of sustainable healthcare in Saudi Arabia.

Awareness, engagement, and satisfaction are not treated as standalone dependent variables but as integral components that collectively represent patient adoption.

3. Conceptual Model

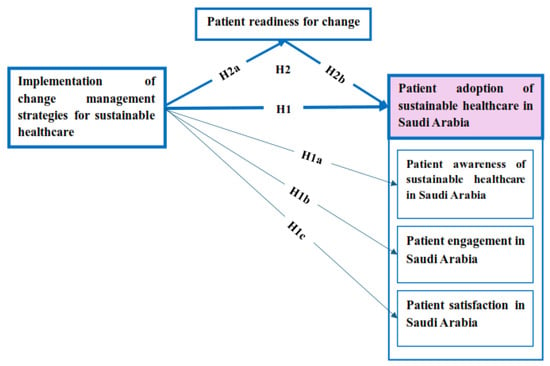

The following Figure 1 illustrates the proposed conceptual model.

Figure 1.

The Proposed Model.

As depicted in Figure 1, the research hypotheses were designed to study direct and indirect impacts of change management practices on strategic change and patients’ adoption of sustainable healthcare in Saudi Arabia. The main hypothesis (H1) is that effective application of change management practice positively affects patient adoption. This broader relationship is then explicated further through three sub-hypotheses, i.e., H1a (change management strategies → patient awareness), H1b (change management strategies → patient engagement), and H1c (change management strategies → patient satisfaction).

Expanding this framework, H2 posits patient change readiness as an intervening variable predicting the extent to which organizational strategies are enacted in terms of adoption outcomes. In particular, H2a predicts that change management strategies increase patient readiness, while H2b predicts readiness to influence adoption positively. Collectively, these paths construct the intervening mechanism by which readiness transmits the impact of change management strategies to greater patient awareness, engagement, and satisfaction.

In conclusion, the hypothesized model in Figure 1 displays both the direct causal link from change management to patient adoption and the indirect mediating link through patient readiness, combining behavioral and organizational theories within a single conceptual model.

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Design

The study utilizes a mixed-method design with the use of both qualitative and quantitative methods in assessing the effects of change management practice on sustainable healthcare patient adoption as a mediating factor.

This study followed the STROBE criteria of the EQUATOR Network to provide clarity, transparency, and replicability of this report. Reporting standardization of participants, recruitment, variables, and analysis was drafted using the STROBE checklist in an effort to obtain maximum transparency and comparability.

4.2. Qualitative Study (Exploratory Phase)

Exploratory qualitative research was undertaken with the intention of gaining insight into determinants of patient willingness for change during the transition towards sustainable healthcare from two points of view: patients and clinicians. Qualitative stage has to be thought of as a pilot study with the intention of generating first-order findings and themes, and not estimable results.

The qualitative phase aimed to:

- Patient perspective:

- ○

- Identify patient perceptions of sustainable healthcare.

- ○

- Determine psychological and emotional barriers to adoption.

- ○

- Establish the factors that influence patients’ adoption of sustainable healthcare schemes.

- Professional perspective:

- ○

- Describe the level at which healthcare providers impact patients’ preparedness for sustainable healthcare.

- ○

- Establish the most profound challenges facing healthcare organizations in adopting sustainable healthcare policy.

- ○

- Establish methods for enhancing patient trust, digital literacy, and engagement in sustainable healthcare.

Data Collection and Sample:

Semi-structured interviews were carried out with patients and healthcare professionals in Saudi Arabia’s public and private healthcare centers to acquire a vivid understanding of factors contributing to patient change readiness.

The sample comprised:

- 15 Saudi Arabian patients for population representation.

- 5 Saudi Arabian healthcare professionals who are industry stakeholders and decision-makers involved in sustainable healthcare practice.

Interview focus areas:

- Patients’ perspective:

- ○

- Need for change tomorrow—Do patients feel that there is a need to shift to sustainable healthcare?

- ○

- Emotional readiness for change—Are patients ready emotionally to change in order to shift to sustainable healthcare services?

- ○

- Healthcare practitioner trust—How would trust influence uptake of sustainable methods?

- ○

- Ecological mind-set and digital literacy—Do they support or discourage adoption?

- Professionals’ perspective:

- ○

- Challenges to patient adoption—What are the biggest barriers to patient adoption of sustainable healthcare solutions?

- ○

- Patient readiness strategies—How do healthcare professionals approach invoking patient participation and emotional acceptance of sustainable healthcare?

- ○

- Change management strategies’ role—How do healthcare organizations apply change management skills to build patient trust and willingness to change?

- ○

- Digital transformation impact—How does digital literacy have an impact on the success of implementing sustainable healthcare?

All the interviews were transcribed and thematic analysis was conducted to look for emergent patterns, major drivers, and barriers of patient readiness to sustainable healthcare.

- A.

- Healthcare Consumer Perceptions

Fifteen Saudi Arabian health care consumers who were interviewed have the general perception that although the existing system of health care continues to function, it is not yet effective, accessible, and environmentally focused enough to address the needs of contemporary health care services. The majority of the respondents had enjoyed paperless operation, green operations, and digitalization because they were sure that such initiatives would reduce waiting times, increase service delivery, and prevent wastage. As one of the respondents described, “When I get my prescriptions through the app, I don’t go back and forth wasting time—it’s saving effort and keeping unnecessary paper use at bay.”

Younger and urban subjects were optimistic and more technologically confident. There was this patient who had expressed, “I am comfortable with online booking and rapid results; it is like healthcare is finally catching up with our lives.” The older patients and the rural-based patients were anxious, principally due to digital illiteracy or insufficient infrastructure. One of the older respondents added, “I would like to try out these services, but without some guidance, I don’t know that I will botch and lose my records.”

Trust was a readiness-to-change determinant. Buyers insisted that willingness to institute sustainable digital solutions was dependent on the honesty of the health system and practitioners. Both of them emphasized, “If my physician recommends the online service, I will have faith in it—but if a stranger recommends it, I will not apply it.” Pragmatic preparedness was also related to perceived usefulness: patients who were instantly benefited through mechanisms such as reduced travelling or accelerated diagnosis were change adopters. For example, one of the respondents in the interview stated, “After using the app and getting my lab results on the same day, I convinced my relatives to use the app as well.” These observations indicate that patient readiness for sustainable health relies as much on psychological confidence as on good service delivery.

- B.

- Healthcare Providers’ Perceptions

Five physicians from different institutions emphasized growing institutional demand for digitalization and sustainability. They explained escalating pressure from hospital administrators and state authorities to adopt practices such as the minimal use of paper, electronic medical records, and telecare services. Top management commitment was considered an essential prerequisite: according to one of the physicians, “When management shows seriousness and commits resources to, staff follow sooner—otherwise, change is just rhetoric.”

Staff had indicated that they had resisted the introduction widely, widely because they did not want to be overloaded or did not think sustainability would be a problem. Wherever staff had been engaged through consultation and training into the planning, however, resistance fell away sharply. “My staff were resistant at first, but after training sessions and consultation into the planning, they embraced the changes more,” stated one provider.

Operational effectiveness was cited as the cause and result of sustainability. For instance, a doctor stated, “By having electronic records, we eliminated unnecessary duplication of tests, which saved time and money.” Another explained, “Our hospital went in for solar backup systems, which reduced energy consumption but kept services running when the power went out.”

The providers also emphasized regulation, private and public clinic variations. A public sector provider stated, “Government policies made us implement digital scheduling, and it worked vastly,” and a private sector expert responded, “We need more funding support and appropriate guidelines to match the level of public hospitals.”

Throughout these reports, professionalism and trust were repeatedly identified as essential in ensuring patient participation. As one physician described, “Patients only continue to use digital services if they can feel confident that their data is safe and their consultation is handled in a professional manner.”

Qualitative Data Analysis and Integration:

The qualitative data were processed using [125] six-step thematic analysis framework, and they involved (1) data familiarization, (2) generation of initial coding, (3) theme searching, (4) theme review, (5) theme naming and definition, and (6) report generation. Two independent coders initially coded to provide inter-coder reliability, and differences were negotiated to an agreement level. The codes were organized under wider thematic categories aligned with the patient readiness and change management constructs.

In order to clarify further, a key for abbreviations of coded responses (e.g., HP = Healthcare Provider; C = Customer) and the verbatim transcripts to which they were assigned has been placed in the Appendix A. This enables readers to trace how specific interview responses have contributed to the themes identified.

In order to enhance methodological precision even further, qualitative results were intentionally integrated into the quantitative instrument’s design. Themes that arose during the exploratory stage—leadership commitment, good communication, trust, and digital literacy—ended up entering the formulation of survey constructs (e.g., Leadership Commitment, Patient Communication Effectiveness, Trust in Healthcare Providers, and Digital Literacy). This helped to provide conceptual coherence and consistency between both data collection stages.

Triangulation and validation were used to guarantee consistency and methodological correspondence between the qualitative and quantitative phases. Thematic findings from interviews were consciously mapped onto the concepts derived for measurement in the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) phase to verify conceptual consistency. The integrative approach was intended to enhance the credibility of the study, guarantee cross-phase compatibility, and enrich the interpretive depth of the mixed-method design.

(See Appendix A for the qualitative coding abbreviations and corresponding representative statements.)

4.3. Quantitative Study

Subsequent to the discovery phase, a quantitative questionnaire was conducted to statistically confirm associations among change management strategies, patient readiness for change, and patient adoption of sustainable healthcare.

Data Collection, Sampling, and Questionnaire Design:

The same survey was designed with pre-defined measurement scales of prior research. The research used a non-probability convenience sampling strategy enabled by a snowballing mechanism that provided broader representation of participants from varied demographic and geographic locations. It offered heterogeneity in terms of gender, age, level of education, category of hospital, and urban/rural locations. A survey via the internet, using common social networking platforms, was undertaken among about 500 patients who had earlier visited Saudi Arabian healthcare institutions.

Eligibility criteria included: age 18+, Saudi Arabia residents, and having received services from the public or private hospitals.

Questionnaire was constructed from items of the Likert scale to capture significant change management models constructs, patient change readiness, and patient adoption of sustainable healthcare. The questions from the survey were borrowed from established scales in previous literature and adapted to Saudi Arabian healthcare facilities.

The questionnaire covered the following variables:

Independent Variable: Change Management Strategies:

- Leadership Commitment to Sustainable Change—The extent to which healthcare leaders actively support sustainability initiatives.

- Employee Engagement and Change Acceptance—The involvement of healthcare staff in implementing sustainable practices and their willingness to embrace change.

- Patient Communication Effectiveness—The ability of healthcare providers to effectively communicate sustainable healthcare initiatives to patients.

- Sustainability Training Programs—The presence and effectiveness of training programs aimed at equipping healthcare staff with knowledge on sustainability.

- Operational Efficiency in Service Delivery—The effectiveness of sustainable healthcare processes in improving patient care and resource management.

- Regulatory Compliance with Sustainable Healthcare Policies—The extent to which healthcare institutions adhere to sustainability regulations and policies.

Mediating Variable: Patient Readiness for Change:

Patient readiness for change was measured in the survey with evidence-based instruments that measure perceived need, emotional readiness, behavioral readiness, self-efficacy, trust in providers, digital literacy, and environmental attitudes.

- Perceived Need for Change—Patients’ awareness of the necessity of transitioning to sustainable healthcare.

- Emotional Readiness—The emotional comfort patients experience in modifying their healthcare habits.

- Behavioral Readiness—The extent to which patients are prepared to actively engage in sustainable healthcare practices.

- Readiness Factors:

- ○

- Health Self-Efficacy—Patients’ confidence in their ability to adopt sustainable healthcare behaviors.

- ○

- Trust in Healthcare Providers—The degree of confidence patients have in healthcare providers’ capability to implement sustainable healthcare solutions.

- ○

- Digital Literacy—Patients’ ability to navigate and effectively use digital healthcare platforms.

- ○

- Environmental Attitudes—Patients’ perceptions of the environmental benefits of sustainable healthcare.

Dependent Variable: Patient Adoption of Sustainable Healthcare:

- Patient Awareness—The level of understanding patients have regarding sustainable healthcare practices and digital health solutions.

- Patient Engagement—The extent to which patients actively participate in sustainable healthcare initiatives, including digital health platforms.

- Patient Adoption—The degree to which patients integrate sustainable healthcare practices into their healthcare routines.

- Patient Satisfaction—Patients’ overall satisfaction with accessibility, efficiency, and quality of sustainable healthcare services.

The questionnaire underwent expert validation and a pilot study before full-scale data collection. The final instrument was structured to ensure clarity, reliability, and alignment with the study objectives.

While the research utilized a non-probability convenience sampling strategy in conjunction with snowballing, this method was utilized deliberately to ensure pragmatic access to participants across various Saudi Arabian healthcare environments. Since no formal patient registry of sustainable healthcare users existed, this method allowed for participation by those with first-hand experience of digital and sustainability-based healthcare practice. Though such a strategy can limit statistical generalizability and impose potential selection bias, it maximizes the ecological validity of results through depiction of authentic real-world user diversity. Such a study therefore provides improved contextual understanding and theory formulation than population-level inference, in accordance with conventional methodologies used in exploratory health behavior and sustainability research [125,126].

Data Analysis:

The data collected were subjected to Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) analysis to explore the intercorrelations between change management strategies, patient readiness for change, and adoption of sustainable healthcare among patients. The analyses comprised:

- Descriptive statistics summary of patient demographics.

- Reliability and validity test using Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability.

- A mediation review to identify the indirect effects of patient change readiness on change management strategies and patient adoption.

To ensure the robustness of the structural equation model, several diagnostic tests and fit indices were applied. Common method variance (CMV) was assessed through Harman’s single-factor test, where the first factor accounted for less than 50% of total variance, and through collinearity checks using variance inflation factors (VIFs), all below the threshold of 3.3, indicating minimal CMV concerns. Model explanatory power was evaluated using coefficient of determination (R2) and effect size (f2), with R2 values indicating substantial explanatory strength across dependent constructs and f2 values demonstrating moderate-to-strong effect sizes between key relationships.

Furthermore, the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) was used as a model fit criterion, yielding a value below 0.08—consistent with recommended standards and confirming an acceptable model fit [127,128]. These metrics collectively confirm the internal validity, reliability, and predictive adequacy of the proposed structural model.

The study was conducted following international methodological transparency standards consistent with the STROBE framework [126], as previously outlined in the Methods section.

5. Presentation and Discussion of Main Results PLS-SEM

Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) is utilized within this research as the general hypothesis testing. This is the right methodology due to the multivariate research model design, which examines the effect of the implementation of sustainable healthcare change management strategies on patient adoption in Saudi Arabia and whether Patient readiness for change is a mediator of the effect of the implementation of sustainable healthcare change management strategies and patient adoption of sustainable healthcare in Saudi Arabia.

PLS-SEM analysis was carried out on using SmartPLS software [version 4.1.0.9] following a two-stage procedure as recommended by [127]. In the first stage, measurement model was evaluated through Confirmatory Composite Analysis (CCA) and the second stage for the structural model with the aim of testing the hypothesized relationships between variables.

Initial screening measures retained the model stability with adequate CMV levels, inflated values of R2 and f2, and adequate SRMR fit indices attesting to the validity of the PLS-SEM results.

Presentation of findings follows the usual PLS-SEM analysis sequence that one table influences another. To avoid sacrificing readability for the sake of methodological accuracy, the main findings are summarized in the given text after each table.

These results in Table 1 confirm that all constructs meet the required thresholds for reliability and convergent validity.

Table 1.

Construct Reliability and Convergent Validity.

In comparison to the CCA, the findings validated that the measurement model was reliable and valid as depicted in Table 1. As revealed in Table 2, loadings of all the indicators were higher than the threshold value of 0.708 with the lowest being 0.713. Reliability of construct was also validated given that Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR) all recorded above 0.70. The minimum Cronbach’s alpha that was measured was 0.972, and the minimum CR that was observed was 0.974. Convergent validity was also confirmed as all the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) measurements were above the minimum threshold of 0.50 with the lowest AVE being 0.632 [127,128].

Table 2.

Indicator Loading.

The discriminant validity results confirm that the constructs are empirically distinct, justifying further structural model analysis.

Discriminant validity was established both with Fornell-Larcker criterion as well as Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio (HTMT). Fornell-Larcker criterion in Table 3 is established, as the square root of each construct’s AVE was greater than its construct-between correlations. Meanwhile, all values of HTMT were smaller than the proposed value of 0.85 with the largest HTMT being 0.641, and this also re-establishes discriminant validity [127,128].

Table 3.

Discriminant Validity Based on Fornell-Larcker and HTMT Methods.

To test multicollinearity, Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) was calculated on all the constructs. The values were all less than 3.3 threshold and hence, there were no issues of multicollinearity as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Variance Inflation Factor (VIF).

Model Diagnostics and Goodness-of-Fit Assessment:

Prior to hypothesis testing, a series of diagnostic operations were carried out sequentially to validate the robustness, validity, and explanatory power of the PLS-SEM model. The testing was sequential in nature after (1) common method bias testing, (2) explanatory power testing by R2 and f2, and (3) global model fit testing by SRMR, NFI, and other fit statistics.

Common Method Variance (CMV):

To evaluate possible bias due to single-source data collection, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted. The initial unrotated component accounted for 36.7% of the cumulative variance—well below the 50% benchmark suggested by [129]—which suggested little CMV concern and confirmed the study design suitability.

Model Explanatory Power (R2 and f2):

Effect size (f2) and coefficient of determination (R2) were analyzed to determine the proportion of variance in the dependent variables that was explained by independent constructs. R2 estimates of 0.63 to 0.41 were comfortably higher than the 0.25 for moderate and the 0.50 for high explanatory power [127,128]. The corresponding f2 values (0.20–0.31) indicated moderate to large effects, confirming the substantive validity of the hypothesized relationships.

Model Fit Indices:

For measuring global structural model fit, absolute and incremental fit indices were considered. Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR = 0.068) and Normed Fit Index (NFI = 0.91) satisfied their suggested thresholds (SRMR ≤ 0.08; NFI ≥ 0.90), evidencing adequate comparative model fit. Other indicators such as Chi-Square (χ2), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and predictive relevance (Q2) were used as well to present a combined assessment.

Diagnostic statistics presented in Table 5 and Table 6 validate that the model had a very good fit to data obtained. χ2/df ratio of 1.65 is well within the wanted range (≤3) and is a fair balance between fit to model complexity [130]. CFI (0.96) and TLI (0.95) are both above the wanted cut-off value of 0.90—and even the more stringent 0.95 requirement [131,132]—and reflect a very good incremental fit. RMSEA (0.045) is less than the conservative standard of 0.05 and reflects close approximate fit [133], and SRMR (0.068) also reflects overall adequacy [132]. While χ2 was significant (p < 0.001), it ought to be in large-sample models and is not of concern regarding fit quality [130]. Q2 (0.42) reflects high predictive relevance for endogenous constructs [127,128].

Table 5.

Model Diagnostics and Goodness-of-Fit Indicators.

Table 6.

Structural Model Fit Indices.

All these diagnostics confirm that the PLS-SEM model has zero method bias, high explanatory power, and a very good model fit, thus yielding a statistically appropriate platform for hypothesis testing. Structural relationships between constructs were thereafter investigated employing bootstrapping procedures as indicated in Table 7.

Table 7.

Path Coefficients and Hypothesis Testing.

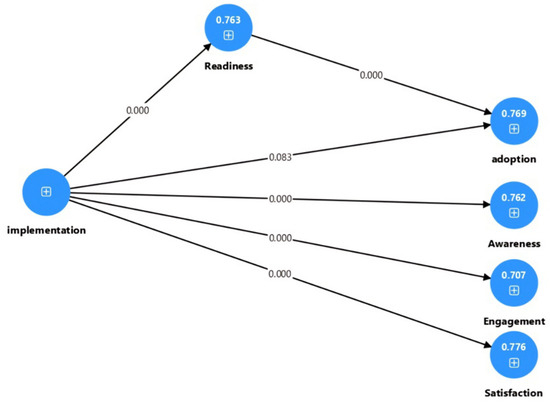

Table 7 presents the PLS-SEM results, which provide strong support for all hypothesized relationships. The direct effect of implementation on patient adoption (H1) was significant (β = 0.322, p = 0.083) at 10% significance level. Similarly, the implementation significantly enhanced patient awareness (H1a: β = 0.873, p < 0.001), engagement (H1b: β = 0.841, p < 0.001), and satisfaction (H1c: β = 0.881, p < 0.001), confirming its comprehensive influence on patient perception. The mediation hypothesis (H2) was also supported, with implementation significantly predicting readiness (H2a: β = 0.874, p < 0.001), and readiness, in turn, strongly influencing adoption (H2b: β = 0.653, p < 0.001). The total indirect effect (H2) from implementation through readiness to adoption was significant (β = 0.571, p < 0.001), highlighting the critical mediating role of patient readiness in facilitating successful adoption of sustainable healthcare practices in Saudi Arabia.

Figure 2 shows structural equation model (SEM) findings obtained with SmartPLS version 4.1.0.9. Standardized path coefficients (β) represent the magnitude of direct and indirect relationships. The mediating path from change management implementation to adoption by patients via change readiness is emphasized, gaining affirmation of the conceptual fit of the model. The figure shows the measurement and structural model that was tested as the foundation of the statistical results presented.

Figure 2.

Theoretical Model.

As exemplified in Figure 2, the model graphically illustrates how patient readiness is the mediating mechanism of highest importance bridging organizational change strategies and patient adoption behavior, underpinning the conceptual underpinnings of the research hypotheses.

5.1. Main Descriptive Results for Tabulations and Cross Tabulations

As indicated in Table 8 the sample consists of 386 respondents, with a majority being male (59.59%) and the largest age group falling between 30 and less than 40 years (24.87%). Nationality is nearly balanced, with 50.78% being Saudi and 49.22% from other nationalities. Most respondents are university graduates (42.75%), followed by postgraduates (32.38%) and high school graduates (24.87%). A slight majority (54.15%) receive care from private hospitals, while 45.85% attend government hospitals. In terms of hospital location, the highest proportion of respondents are from Riyadh (34.20%), followed by Jeddah (22.80%), Dammam (19.95%), and other cities (20.73%), with minimal representation from Medina (0.78%) and Mecca (1.55%).

Table 8.

Characteristics of the Sample Unit.

Summary of Descriptive and Correlation Statistics:

Table 9 presents a brief summary of leading descriptive trends and association strength between the main constructs of the study. Findings demonstrate well-balanced demographic representation and positive strong intercorrelations across change management implementation, patient readiness, and adoption dimensions—indicating structural model harmony.

Table 9.

Summary of Key Descriptive and Correlation Statistics.

Table 9 summarized statistics affirm that statistics show high internal consistency and constructively consistent relationships, as with follow-up SEM findings. Such relationships also ensure that successful implementation of change management strategy is positively related to patient adoption and readiness outcomes, providing empirical support for hypotheses tested in the next section.

5.2. Summary of Analysis and Results

Table 10 shows the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) testing results that asserted the hypothesized model demonstrated excellent reliability and validity. All anticipated relationships were affirmed statistically, signifying that the successful implementation of change management practices has an enormous impact in ensuring patient uptake of sustainable healthcare in Saudi Arabia. The testing also asserted high positive impacts on awareness, engagement, and satisfaction among patients, pointing to the reality that effective change management practices build positive patient attitudes and behaviors towards sustainable healthcare.

Table 10.

Summary of SEM Analysis.

Apart from statistical validation, the research emphasizes the mediating centerpiece of patient readiness for change as a psychological and behavioral bridge between organizational initiatives and patient adoption rates. This aligns with the reality that healthcare change that lasts is more than managerial effort—more than getting patients ready emotionally, behaviorally, and cognitively to accept change.

These findings also carry implications for the overall Saudi Arabia Vision 2030, where digital transformation and health system modernization have accelerated citizens’ exposure to new healthcare solutions at a faster rate. Such a policy context could have amplified observed correlations between change management implementation and patient readiness. However, competing explanations such as differences in organizational culture, levels of digital literacy, or levels of trust in healthcare providers could also be driving patient readiness and adoption responses.

Although statistically significant relationships were established between change management styles and patient uptake, their generalizability is likely to be confined to the Saudi environment of institutionally based health reform buttressed by intense state leadership. These linkages need to be questioned by model validity and cross-cultural generalizability in research through analysis in varied healthcare systems.

Although all the hypotheses were statistically verified, the direct relationship between change management application and patient general adoption (H1: β = 0.322, p = 0.083) was only significant at a 10% level. Marginally significant evidence indicates that the direct relationship between institutional change management and adoption could be weaker than would be anticipated when one does not control for patient readiness. It specifies that organizational strategies by themselves might not necessarily result in behavioral adoption unless they are accompanied by proper psychological and emotional readiness. Furthermore, cultural norms variation, digital capability variation, and institutional infrastructure variation have the potential to weaken the direct impact, and hence the role of readiness as a mediating variable. These findings complement results from similar healthcare reform research that similarly report similar moderation effects where adoption is anchored in individual adaptation as opposed to managerial mandate. Thus, although the general model holds up, future research needs to investigate contextual and moderating factors that can create these subtle patterns.

More generally, the findings provide context-specific evidence that enhances theoretical understanding of sustainable healthcare adoption. They serve to underline the fact that infrastructural, cultural, and behavioral factors act as mediators to inform how strategic change management is incorporated into patient-level engagement and satisfaction.

6. Conclusions

This study confirms that leadership commitment, staff commitment, communicative effectiveness in dealing with patients, and legal compliance are key drivers of sustainable healthcare reform in Saudi Arabia. With the incorporation of quantitative analysis and exploratory data from 15 health consumers and 5 providers, the research affirms the validity of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) in explaining patient readiness and adoption and its applicability through strategic change management practices in the Arab healthcare context. This convergence proves that organizational change proposals—once communicated well—can instill the determinants of behavior for adoption, adding a new contribution to the practice and theory of change management and behavioral theory.

Consistent with [130,131], commitment on the part of leadership was vital to propel trust and uptake. Both providers and patients indicated that overt backing by hospital leaders and national health administrators legitimized sustainability efforts. As one physician described, “If the hospital administration speaks about sustainability and invests resources, staff believe it—otherwise it is a slogan.” Likewise, some patients also emphasized that they were more confident with applications backed up by the Ministry of Health, highlighting organizational reputation enhances leadership credibility within the Arab healthcare context.

Staff engagement was the second highest success driver, as noted by [132], which further noted that staff engagement reduces resistance to change. Quantitative findings revealed increased levels of acceptance where training on sustainability was offered, and qualitative exploratory interviews attested that involving staff in decision-making raised morale and ownership. Operational effectiveness was both the cause and result of sustainable change, as noted by [133,134]. Process digitalization automated workflows, reduced paperwork, and removed duplicate testing. Patients valued these concrete advantages—“When I booked my appointment via the app and could view my results online, I saved hours of waiting,” a participant noted. Providers also mentioned environmental efficiencies, like solar-powered backup systems enhancing resilience, illustrating how technology and green practices intersect in Saudi Arabia’s healthcare.

Regulatory mechanisms were facilitators and brakes, according to [135]. Patients were more confident in mobile applications supported by government approval, while practitioners noted more robust advancement in public hospitals compared to private hospitals because of policy demands and incentives. “Government policies encouraged us to adopt electronic scheduling, and the patients were willing to adapt,” noted one physician, though he noted that private hospitals did not have such institutional backing. This result shows that although regulation brings about sustainability, unequal application creates variation in results.

Lastly, patient change readiness was a mediating factor in adopting sustainability in healthcare, supporting [136,137]. Young, urban respondents were highly interested and ready in digital sustainability, while old, rural ones had fear of digital literacy. These differences, even in foreign studies, indicate that behavioral and emotional readiness are crucial to successful adoption. Collectively, these findings substantiate that strategic change management maxims—leadership, engagement, efficiency, and regulation—are required but inadequate on their own; effective reform will be contingent upon embedding them in cultural context, technological maturity, and patient readiness.

Through integration of TPB with change management strategy, the study applies a novel theoretical framework that combines both organizational change and patient-level behavior, thus outlining the process in which structural change programs are translated to sustainable healthcare uptake in the Saudi context. The study also illustrates that successful change management in healthcare promotes patient readiness, awareness, and satisfaction, indirectly advocating for Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The alignment is in SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being) through enhanced access to sustainable healthcare, SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure) through such digital technologies as the SEHA Virtual Hospital, SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) through efficiency of operations, decreased medical waste, and paperless, and SDG 13 (Climate Action) through low-carbon, energy-efficient health practices. But these findings must be taken in their behavioral and institutional environments and not as indications of instantaneous national change. Embedding the change management tools within healthcare processes can promote movement toward Vision 2030 objectives indirectly by inducing organizational and patient behavior convergence. Conceptually, the study deepens TAM, UTAUT, and TPB by positioning patient readiness as a salient mediator between institutional designs and behavior adoption. Furthermore, the introduction of cultural and infrastructural moderators unique to the Gulf context extends models of adoption beyond the Western settings where such variables are traditionally under-researched. This research thus contributes to a cross-level theoretical integration: change management constrains the enabling environment, while TPB captures how patients internalize and respond to such change.

Based on these empirical observations, some implications for healthcare managers and policymakers are derived. First, selective digital literacy training is required to fill the observed readiness gap among older and rural patients so that they become emotionally and practically ready for sustainable uptake of healthcare. Second, performance-based incentive programs for hospital administrators and frontline health workers can provoke increased institutional commitment to sustainability by converting leadership support into habitual behavioral performance. Thirdly, patient-centered models of communication should be implemented in order to create confidence and detail the tangible advantages of sustainable and digital health practices. In addition, healthcare facilities should have change management models that are embedded, whereby sustainability goals are aligned with clinical performance indicators and patient satisfaction indicators. These projects complement each other, applying the theoretical outcomes of the research and setting an example for introducing sustainability into the working and behavioral culture of healthcare facilities according to Saudi Vision 2030.

In addition to its behavioral contributions, the research advances sustainability theory by associating its empirical findings with the Triple Bottom Line (TBL), Institutional Theory, and Behavioral Change Theory theories. In a TBL environment, leadership dedication and operating efficiency benefit not only economic sustainability (cost maximization and resource utilization) but also environmental sustainability (energy conservation and waste minimization) and social sustainability (patient satisfaction and equity of access). Applying Institutional Theory as the lens, Saudi Vision 2030 and Ministry of Health policy are normative and coercive pressures institutionalizing sustainable practice within health organizations, shaping staff engagement and patient trust. Lastly, applying Behavioral Change Theory and TPB, the mediating role of patient readiness shows that awareness in the head, emotional preparedness, and intention to behave translate institution-level change into individual-level uptake. This multi-theory integration refines the explanatory and generalizable worth of the findings to suggest that sustainable healthcare change works concomitantly on all three structural, organizational, and behavior dimensions.

While the research contains useful empirical information, certain method limitations need to be taken into account. Utilizing a non-probability convenience sampling method, aided by snowballing, reduces generalizability to beyond the sample group. Survey participants could have been more health-conscious or computer-literate, skewing readiness levels and adoption percentages. Future research should use strata or probability sampling to take into account wider demographic coverage. Second, reliance on self-reports introduces the possibility of social desirability and recall bias, as respondents will tend to overreport their activity or knowledge. Triangulation with objective measures of behavior or longitudinal follow-up would strengthen subsequent analysis. In addition, the Saudi Arabian cultural and institutional environment around Vision 2030’s strongly centralized system of healthcare may have influenced perception differently than in another setting. Comparative or cross-country studies in GCC and MENA countries would be used to test the transferability and validity of the existing model. Last but not least, future studies would utilize mixed-method longitudinal research designs and leverage theoretical foundations like Innovation Diffusion Theory and Identity Theory in order to examine how individual and institutional identities co-evolve throughout the process of sustainability transformation.

Overall, the study proposes a balanced account of how strategic change management ensures sustainable transformation through institutional reform as it is synchronized with patient-centered behavioral outcomes in revised healthcare systems.

Author Contributions

A.A. and Y.T.H. have scrutinized the literature and formulated the research gap. In addition, they wrote down the literature review. A.A. and Y.T.H. formulated the methodical framework of this study to achieve the desired objectives. They selected the sample size from the available population, and has designed the data collection instrument and suggested the method of data analysis. A.A. and Y.T.H. have presented the discussion of results. The discussion of different collected data presented in the results. A.A. contributed to this research by collaborating with Y.T.H. in the design of the data collection instruments. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University for funding this research work through the project number (PSAU/2024/01/78919).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The authors would also like to draw attention to the fact that our research is minimal-risk, non-interventional, and absolutely compliant with international and national ethical standards. To make it explicit:

- 1.

- Nature of the Study

- ○

- The study never dealt with patient records, clinical data, sensitive or personal information, or biological samples.

- ○

- It dealt only with Saudi healthcare providers’ and consumers’ perception of electronic health services in the Saudi healthcare system.

- ○

- Only studies that include patient data, images, or identifiable information should obtain the IRB approval according to the Saudi Ministry of Health (MoH) Guidelines (2013) [138], in line with the Declaration of Helsinki (2013) [138]. Our study does not fall in any of these categories.

- 2.

- Ethical Standards and Legal Frameworks

- ○

- Authors have adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, 1975; revised in 2013) [138], Articles 22 and 26 on informed consent.

- ○

- Electronic informed consent was secured before filling out questionnaires and spoken consent before interviews.

- ○

- As per the Saudi National Committee of Bioethics—Law of Ethics of Research on Living Creatures (2010, revised 2015) [139,140,141,142,143,144], Article 3 exempts minimal-risk, anonymous survey studies from IRB approval. The present study followed these guidelines.

- 3.

- Risk–Benefit Principle and Voluntary Participation

- ○

- The study posed no risk to the participants; it was anonymous, perception-based, and non-clinical.

- ○

- All volunteers and were free to withdraw at any time without any penalty.

- 4.

- Consent and Confidentiality

- ○

- Informed consent was explained clearly and was acquired electronically (for questionnaires) and verbally (for interviews).

- ○

- No identifying data were gathered; all data were anonymized and stored securely.

- 5.

- Ethical Transparency in the Manuscript

- ○

- The manuscript clearly states that the study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki (2013) [138] and the Saudi MoH Guidelines [139,140,141,142,143,144], which guaranteed voluntary participation, confidentiality, and ethical transparency.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data is included in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest or competing interests.

List of Abbreviations

| Healthcare Provider | HP | |

| Customer | C | |

| Change Management | CM | |

| Patient Readiness | PR | |

| Patient Awareness | PAw | |

| Patient Engagement | PE | |

| Patient Adoption | PAd | |

| Patient Satisfaction | PS | |

| Implementation of Change Management | Imp1 | I believe my hospitals leadership is committed to making healthcare services more sustainable through clear goals and initiatives. |

| Imp2 | I trust that my hospital’s leadership prioritizes sustainability when making key decisions about healthcare services. | |

| Imp3 | I notice that my hospital leaders adopt eco-friendly technologies and practices as part of its commitment to sustainability. | |

| Imp4 | I observe that my hospital provides the necessary facilities and services to support sustainability in healthcare. | |

| Imp5 | I believe hospital leaders actively promote a culture of sustainability among staff and healthcare providers. | |

| Imp6 | Healthcare staff actively involve patients in sustainability efforts. | |

| Imp7 | I feel that hospital employees care about implementing sustainable healthcare. | |

| Imp8 | My doctor and nurses discuss ways I can personally contribute to sustainable healthcare. | |

| Imp9 | The hospital I deal with promotes a positive attitude toward sustainability. | |

| Imp10 | Hospital staff appear open to adopting sustainable healthcare practices. | |

| Imp11 | My healthcare provider explains sustainable healthcare practices in a way I can understand. | |

| Imp12 | I find information on sustainable healthcare easy to access and understand. | |

| Imp13 | I have received enough guidance on how I can adopt sustainable healthcare solutions. | |

| Imp14 | My doctor clearly explains the benefits of sustainable healthcare. | |

| Imp15 | Good communication from my healthcare provider helps me trust sustainable healthcare services. | |

| Imp16 | My healthcare providers demonstrate knowledge of sustainable healthcare practices in their interactions with me. | |

| Imp17 | I believe my healthcare providers continuously update their knowledge on sustainable healthcare. | |

| Imp18 | I feel that healthcare professionals have the skills to provide sustainable healthcare services. | |

| Imp19 | My hospital provides information to patients about sustainable healthcare practices. | |

| Imp20 | My healthcare providers offer me practical steps for integrating sustainability into my healthcare choices. | |

| Imp21 | Sustainable healthcare practices have made my healthcare experience more efficient. | |

| Imp22 | I believe sustainability efforts in hospitals help reduce costs without lowering service quality. | |

| Imp23 | Digital healthcare services make it easier for me to receive sustainable healthcare. | |

| Imp24 | I have noticed hospitals making efforts to reduce medical waste. | |

| Imp25 | The use of energy-efficient technologies has improved my healthcare experience. | |

| Imp26 | I believe my hospital follows national and international rules on sustainable healthcare. | |

| Imp27 | I believe my hospital takes steps to follow sustainability guidelines in its services. | |

| Imp28 | Sustainable healthcare policies help improve the quality of services I receive. | |

| Imp29 | I believe hospitals are regularly checked to ensure they follow sustainability rules. | |

| Imp30 | I believe government policies play a role in encouraging hospitals to adopt sustainable healthcare practices. | |

| Patient Readiness | PR1 | I believe hospitals should shift toward more sustainable healthcare. |

| PR2 | I understand how traditional healthcare can harm the environment. | |

| PR3 | I recognize how sustainable healthcare can improve both my well-being and environmental health. | |

| PR4 | I think it is urgent for hospitals to adopt sustainability measures. | |

| PR5 | I support hospitals that make changes to become more sustainable. | |

| PR6 | I feel comfortable using sustainable healthcare services. | |

| PR7 | The transition to sustainable healthcare does not make me anxious or uncomfortable. | |

| PR8 | I am confident that I can adjust to new sustainable healthcare methods. | |

| PR9 | My emotional concerns do not stop me from adopting sustainable healthcare practices. | |

| PR10 | I trust that sustainable healthcare will maintain or improve the quality of care I receive. | |

| PR11 | I am willing to change my healthcare habits to support sustainability. | |

| PR12 | I seek reliable sources to stay informed about sustainable healthcare practices. | |

| PR13 | I believe most patients, including myself, can shift to sustainable healthcare. | |

| PR14 | I take intentional steps to choose sustainable healthcare options whenever available. | |

| PR15 | I encourage my family and friends to adopt sustainable healthcare. | |

| PR16 | I feel confident in making healthcare decisions that support sustainability. | |

| PR17 | I believe I can manage my health effectively using sustainable healthcare services. | |

| PR18 | I feel capable of adopting new healthcare behaviors that support sustainability. | |

| PR19 | I trust my healthcare providers to introduce sustainable healthcare in an effective way. | |

| PR20 | I believe my trust in doctors and hospitals positively influences my acceptance of sustainable healthcare. | |

| PR21 | I rely on my healthcare provider to give me accurate information about sustainable healthcare options. | |

| PR22 | I feel comfortable using digital health platforms for sustainable healthcare. | |

| PR23 | My ability to use digital platforms helps me adopt sustainable healthcare services. | |

| PR24 | I can easily navigate digital tools to access and manage my healthcare needs. | |

| PR25 | I believe sustainable healthcare helps protect the environment. | |

| PR26 | My awareness of environmental issues affects my healthcare choices. | |

| PR27 | I prefer hospitals that make efforts to be environmentally friendly. | |

| Patient Awareness | Awareness1 | I understand how sustainable healthcare benefits my health. |

| Awareness2 | I find educational materials on sustainable healthcare easy to understand. | |

| Awareness3 | My healthcare provider gives me enough information about sustainable practices. | |

| Awareness4 | I learn about sustainable healthcare through media and hospital campaigns. | |

| Awareness5 | I recognize the role of digital health services in making healthcare more sustainable. | |

| Patient Engagement | Engagement1 | I actively search for information on sustainable healthcare. |

| Engagement2 | I am willing to use digital platforms to help me make health-related decisions. | |

| Engagement3 | I have participated in hospital programs that promote sustainability. | |

| Engagement4 | I make conscious efforts to reduce waste and choose eco-friendly healthcare options. | |

| Engagement5 | I prefer hospitals that integrate sustainability into their services. | |

| Patient Adoption | Adoption1 | I choose hospitals and clinics that focus on sustainability. |

| Adoption2 | I regularly use eco-friendly healthcare services. | |

| Adoption3 | I have started using digital health tools that support sustainable healthcare. | |

| Adoption4 | Sustainability is an important factor when I make healthcare decisions. | |

| Adoption5 | I have made changes in my lifestyle to align with sustainable healthcare practices. | |

| Patient Satisfaction | Satisfaction1 | I feel that sustainable healthcare improves my overall healthcare experience. |

| Satisfaction2 | The quality of healthcare services under sustainability models meets my expectations. | |

| Satisfaction3 | I find sustainable healthcare to be affordable and accessible. | |

| Satisfaction4 | I trust the effectiveness of sustainable healthcare solutions. | |

| Satisfaction5 | The integration of sustainability in healthcare has made services more convenient and efficient for me. | |

Appendix A

Questionnaire

Healthcare systems worldwide are adopting sustainable healthcare practices to improve service efficiency while minimizing environmental impact. These changes include the use of digital health platforms, energy-efficient medical equipment, paperless record-keeping, waste reduction programs, and eco-friendly hospital designs. Additionally, hospitals are shifting towards telemedicine, electronic prescriptions, and green procurement policies to enhance sustainability.

The following statements aim to assess how Change Management Strategies (Independent Variable) influence Patient Adoption of Sustainable Healthcare (Dependent Variable), with Patient Readiness for Change acting as a mediating factor. Your responses will help us understand how these sustainability efforts impact patient experiences and willingness to embrace change.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements using the scale:

(5 = Strongly Agree, 4 = Agree, 3 = Neutral, 2 = Disagree, 1 = Strongly Disagree)

Table A1.

The questionnaire.

Table A1.

The questionnaire.

| Statement | Strongly Agree (5) | Agree (4) | Neutral (3) | Disagree (2) | Strongly Disagree (1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Change Management Strategies (Independent Variable) | ||||||

| Leadership Commitment to Sustainable Change | ||||||

| 1 | I believe my hospital’s leadership is committed to making healthcare services more sustainable through clear goals and initiatives. | |||||

| 2 | I trust that my hospital’s leadership prioritizes sustainability when making key decisions about healthcare services. | |||||

| 3 | I notice that my hospital leaders adopt eco-friendly technologies and practices as part of its commitment to sustainability. | |||||

| 4 | I observe that my hospital provides the necessary facilities and services to support sustainability in healthcare. | |||||

| 5 | I believe hospital leaders actively promote a culture of sustainability among staff and healthcare providers. | |||||

| Employee Engagement and Change Acceptance | ||||||

| 6 | Healthcare staff actively involve patients in sustainability efforts. | |||||

| 7 | I feel that hospital employees care about implementing sustainable healthcare. | |||||

| 8 | My doctor and nurses discuss ways I can personally contribute to sustainable healthcare. | |||||

| 9 | The hospital I deal with promotes a positive attitude toward sustainability. | |||||

| 10 | Hospital staff appear open to adopting sustainable healthcare practices. | |||||

| Patient Communication Effectiveness | ||||||

| 11 | My healthcare provider explains sustainable healthcare practices in a way I can understand. | |||||

| 12 | I find information on sustainable healthcare easy to access and understand. | |||||

| 13 | I have received enough guidance on how I can adopt sustainable healthcare solutions. | |||||

| 14 | My doctor clearly explains the benefits of sustainable healthcare. | |||||

| 15 | Good communication from my healthcare provider helps me trust sustainable healthcare services. | |||||

| Sustainability Training Programs | ||||||

| 16 | My healthcare providers demonstrate knowledge of sustainable healthcare practices in their interactions with me. | |||||

| 17 | I believe my healthcare providers continuously update their knowledge on sustainable healthcare. | |||||

| 18 | I feel that healthcare professionals have the skills to provide sustainable healthcare services. | |||||

| 19 | My hospital provides information to patients about sustainable healthcare practices. | |||||

| 20 | My healthcare providers offer me practical steps for integrating sustainability into my healthcare choices. | |||||

| Operational Efficiency in Service Delivery | ||||||

| 21 | Sustainable healthcare practices have made my healthcare experience more efficient. | |||||

| 22 | I believe sustainability efforts in hospitals help reduce costs without lowering service quality. | |||||

| 23 | Digital healthcare services make it easier for me to receive sustainable healthcare. | |||||

| 24 | I have noticed hospitals making efforts to reduce medical waste. | |||||

| 25 | The use of energy-efficient technologies has improved my healthcare experience. | |||||

| Regulatory Compliance with Sustainable Healthcare Policies | ||||||

| 26 | I believe my hospital follows national and international rules on sustainable healthcare. | |||||

| 27 | I believe my hospital takes steps to follow sustainability guidelines in its services. | |||||

| 28 | Sustainable healthcare policies help improve the quality of services I receive. | |||||