Plant Fibres as Reinforcing Material in Self-Compacting Concrete: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (a)

- What plant fibres are used in SCC, and what are their properties?

- (b)

- What is the current research maturity regarding the use of plant fibres in SCC?

- (c)

- What are the effects of plant fibres on the rheological and mechanical properties, durability, and microstructure of SCC?

- (d)

- What are the effects of fibre lengths, fibre treatments, and SCMs on the properties of PFRSCC?

- (e)

- What are the limitations, research gaps, and future opportunities for research and innovation in using plant fibres in SCC?

2. Significance of the Review

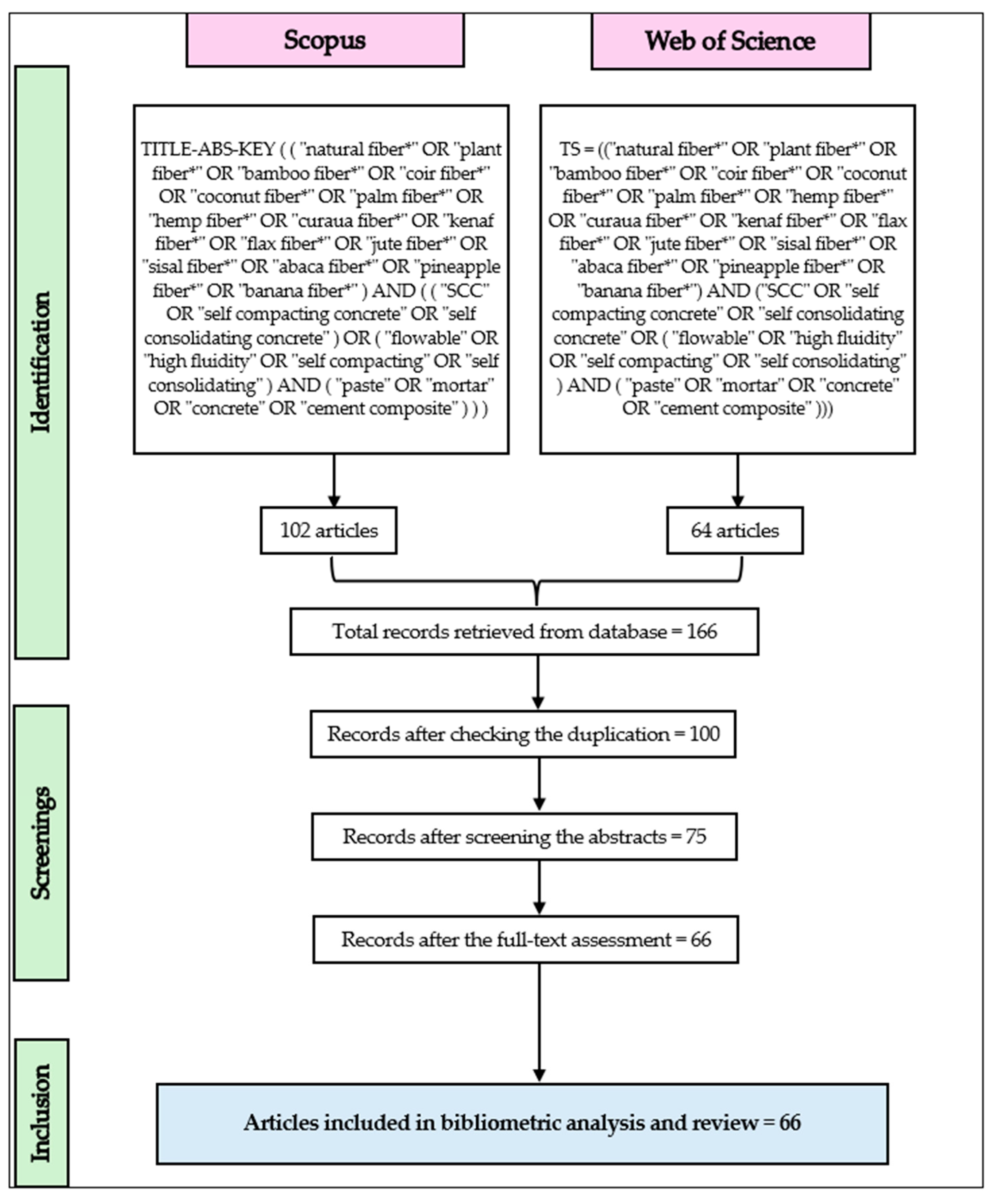

3. Methodology

4. Bibliometric Analysis

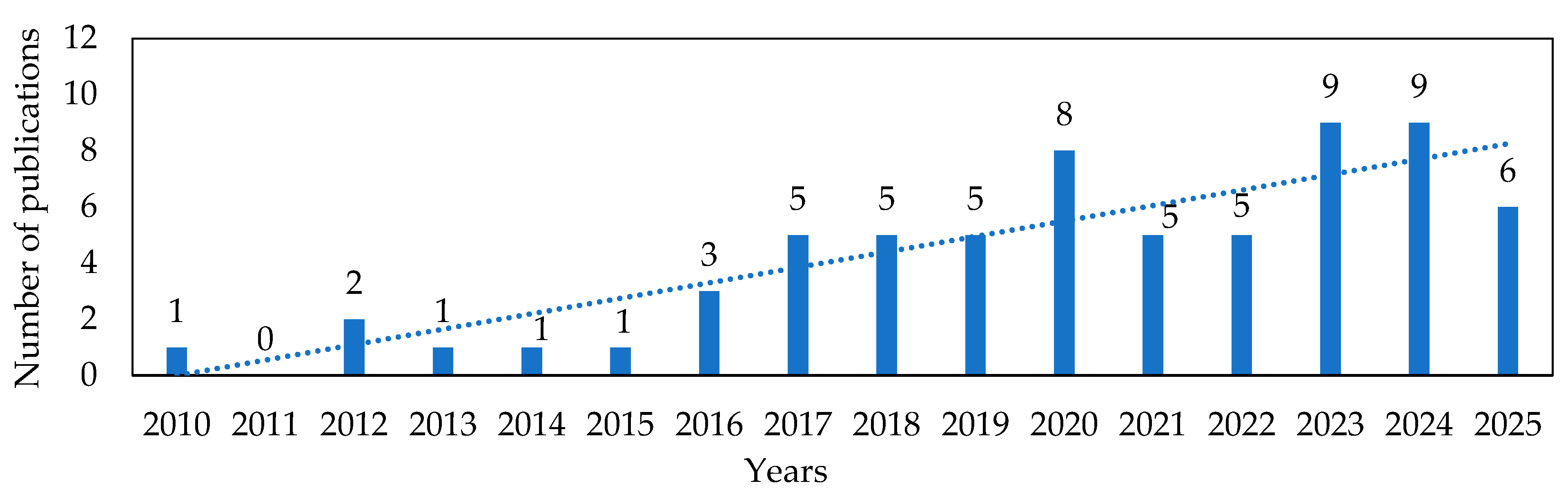

4.1. Annual Publication Trend

4.2. Publication Sources

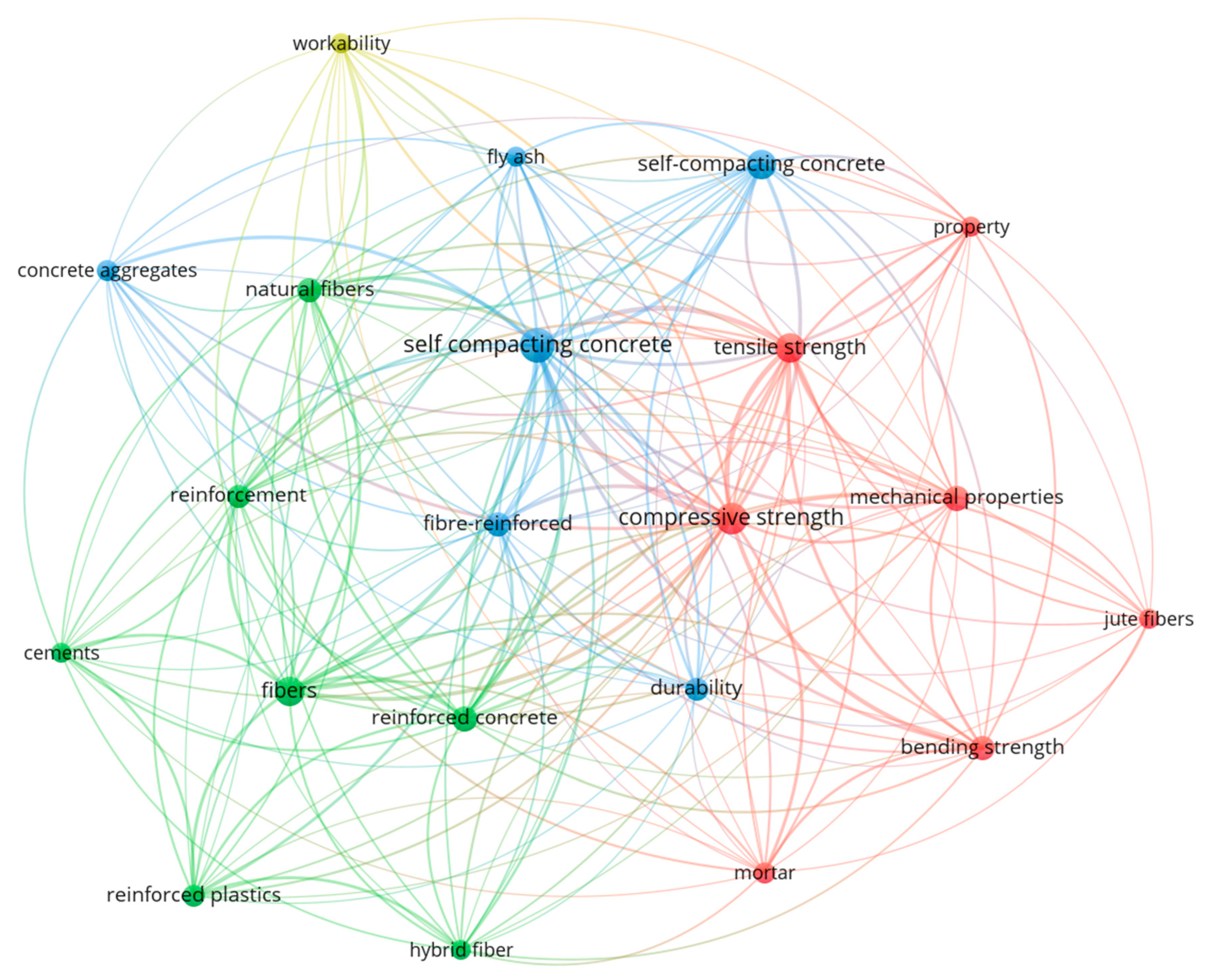

4.3. Most Popular Keywords

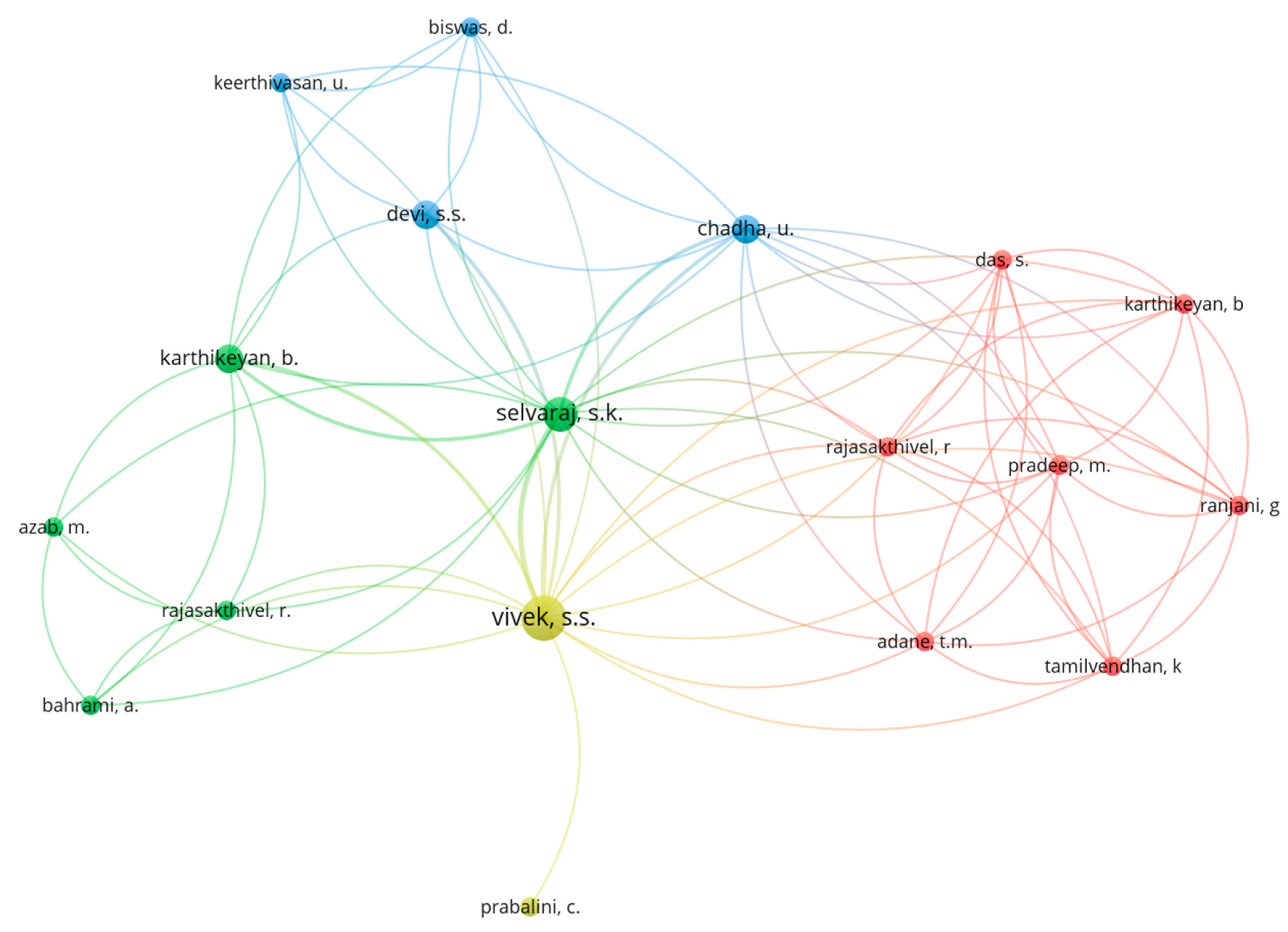

4.4. Top Contributing Authors and Countries

5. Characteristics of Plant Fibres Used in SCC

5.1. Physical and Mechanical Properties of Plant Fibres

5.2. Chemical Composition of Plant Fibres

5.3. Treatments of Plant Fibres

5.3.1. Alkaline Treatment

5.3.2. Coating

5.3.3. Heat Treatment

6. Effects of Plant Fibres on the Properties of SCC

6.1. Effects of Plant Fibres on the Rheological Properties of SCC

6.1.1. Slump Flow

6.1.2. V-Funnel

6.1.3. L-Box

6.1.4. J-Ring

6.1.5. Segregation Resistance by the Sieve Segregation Test

6.2. Effects of Plant Fibres on the Mechanical Properties of SCC

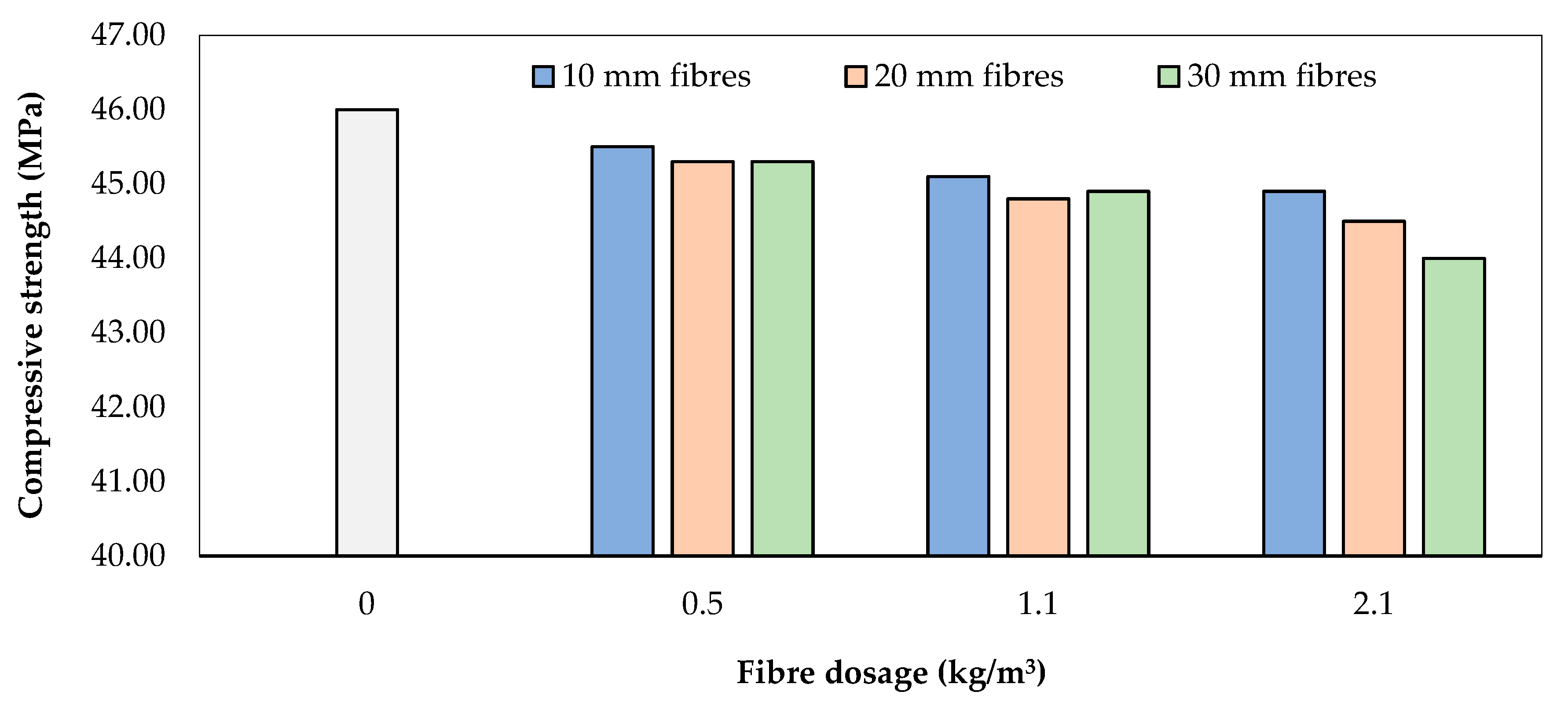

6.2.1. Compressive Strength

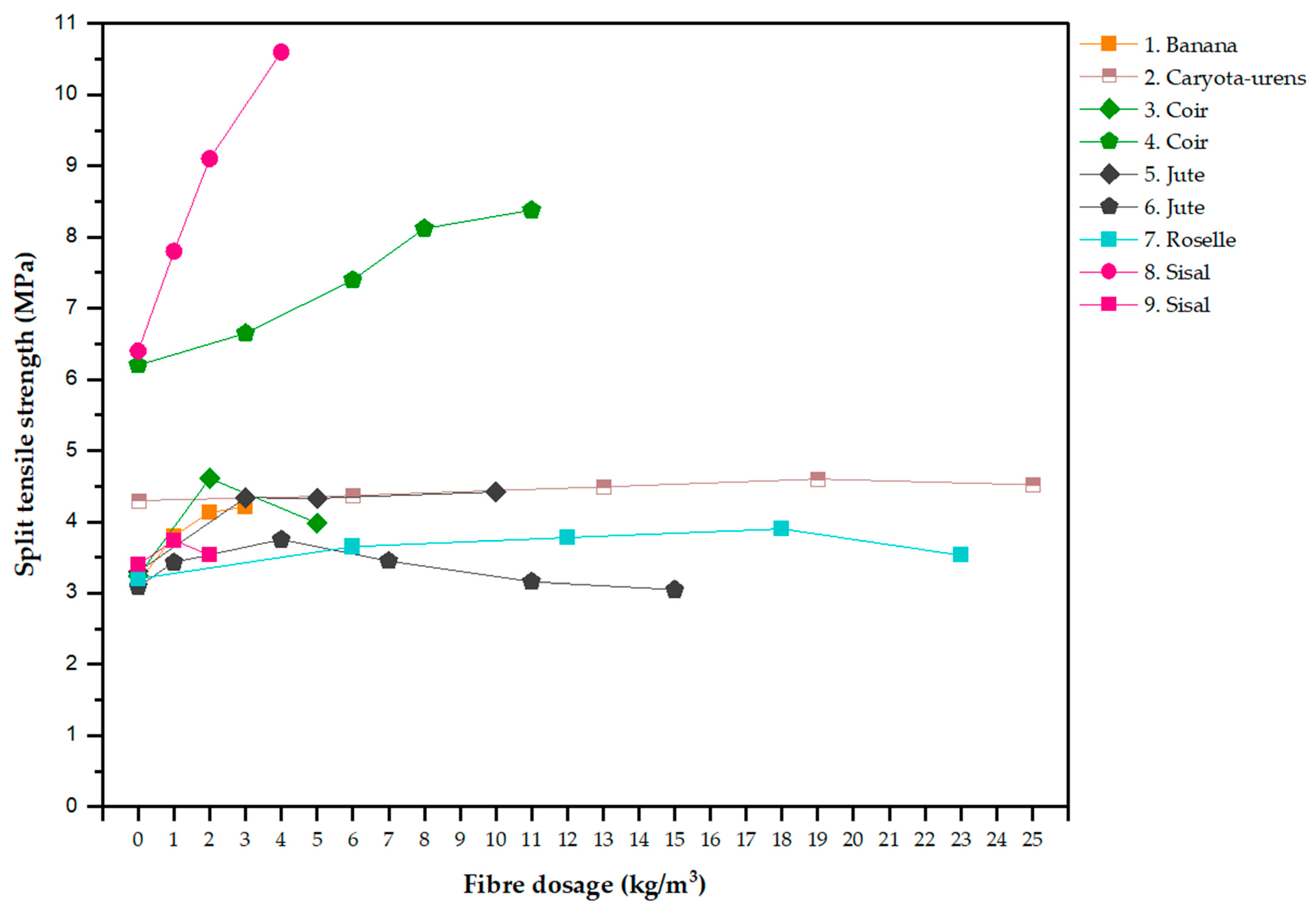

6.2.2. Split Tensile Strength

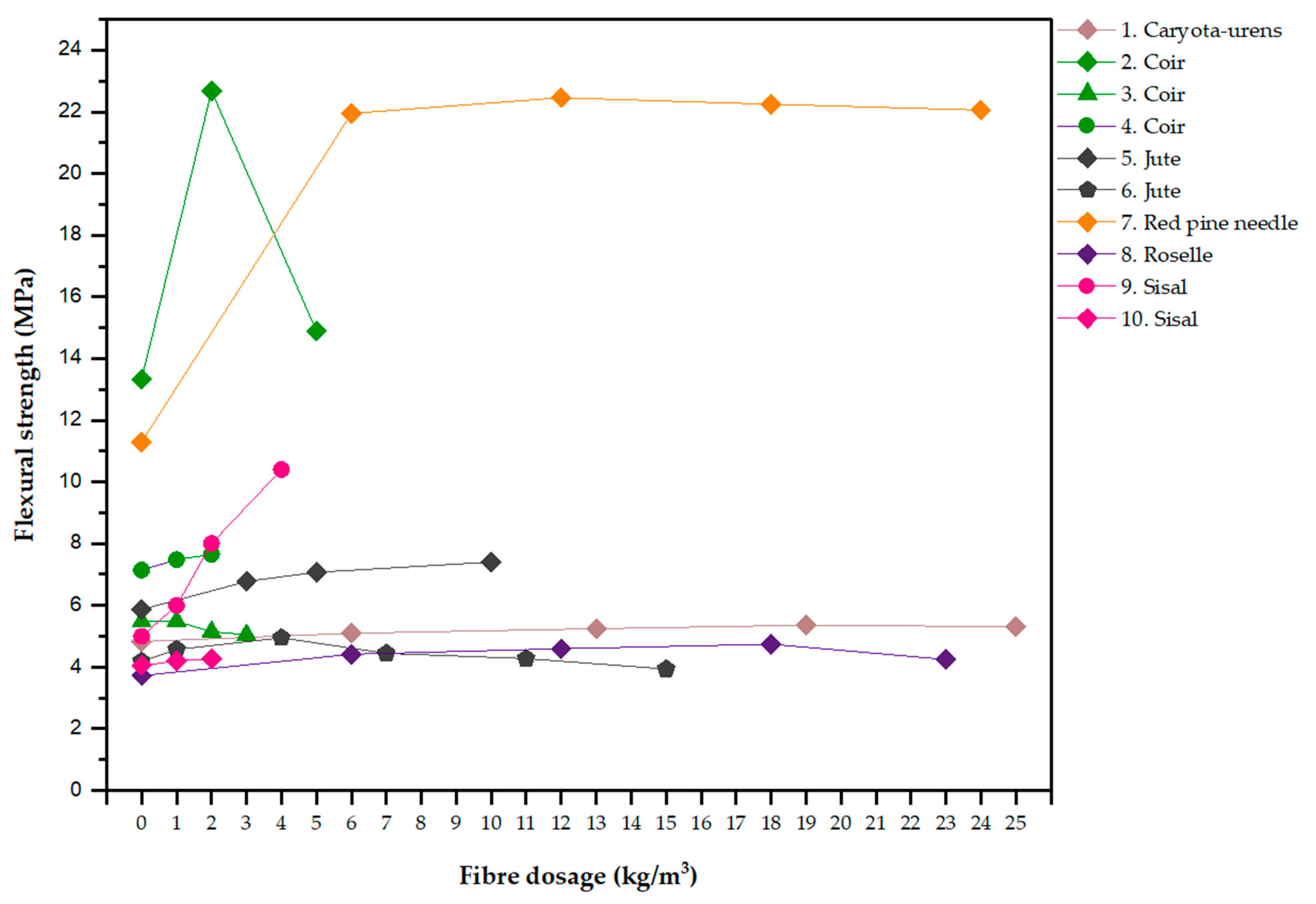

6.2.3. Flexural Strength

6.2.4. Modulus of Elasticity

6.2.5. Flexural Toughness

6.2.6. Impact Strength

6.3. Effects of Plant Fibres on the Durability of SCC

6.3.1. Resistance to Sulphate Attack

6.3.2. Resistance to Acid Attack

6.3.3. Drying Shrinkage

6.3.4. Water Absorption

6.3.5. Freeze and Thaw Resistance

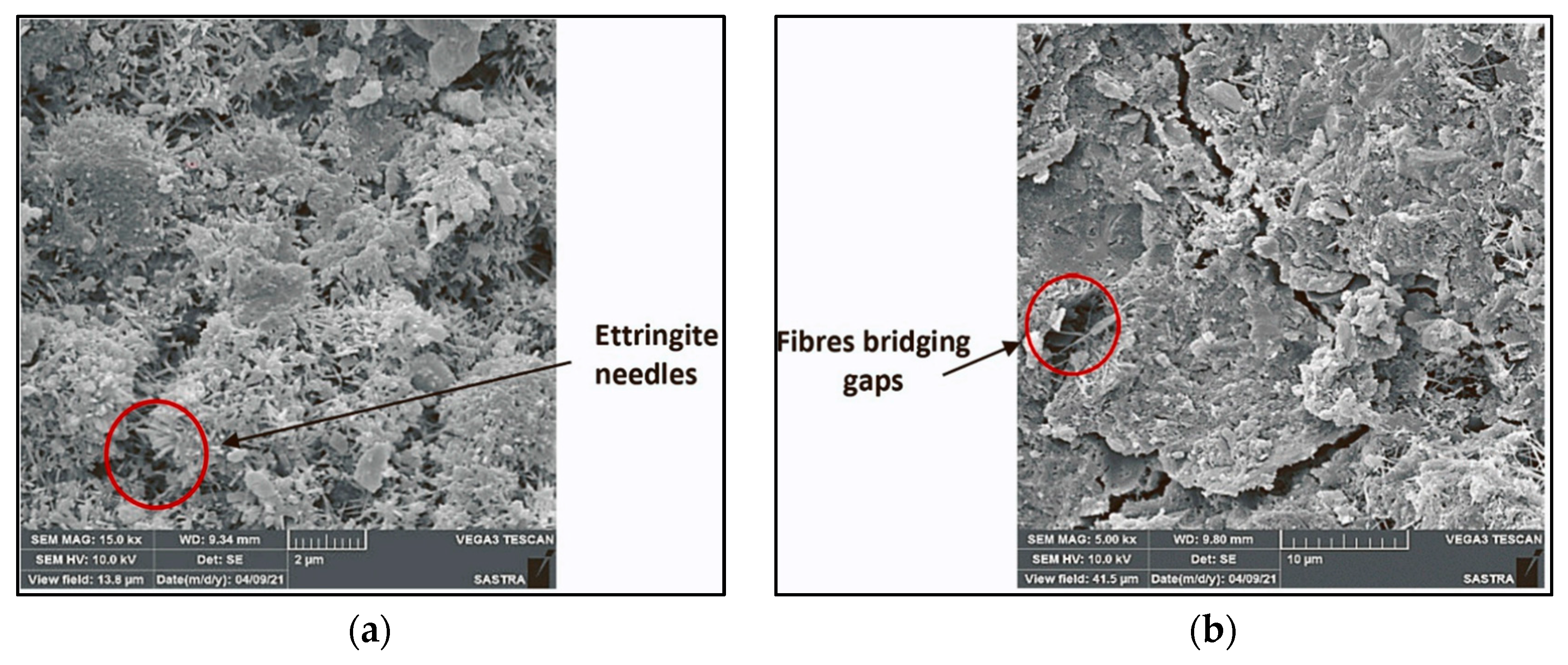

6.4. Effects of Plant Fibres on the Microstructure of SCC

7. Effects of Fibre Length on the Properties of PFRSCC

7.1. Effects of Fibre Length on the Rheological Properties of PFRSCC

7.2. Effects of Fibre Length on the Mechanical Properties of PFRSCC

7.3. Effects of Fibre Length on the Durability of PFRSCC

8. Effects of Fibre Treatments on the Properties of PFRSCC

8.1. Effects of Fibre Treatments on the Rheological Properties of PFRSCC

8.2. Effects of Fibre Treatments on the Mechanical Properties of PFRSCC

8.3. Effects of Fibre Treatments on the Durability of PFRSCC

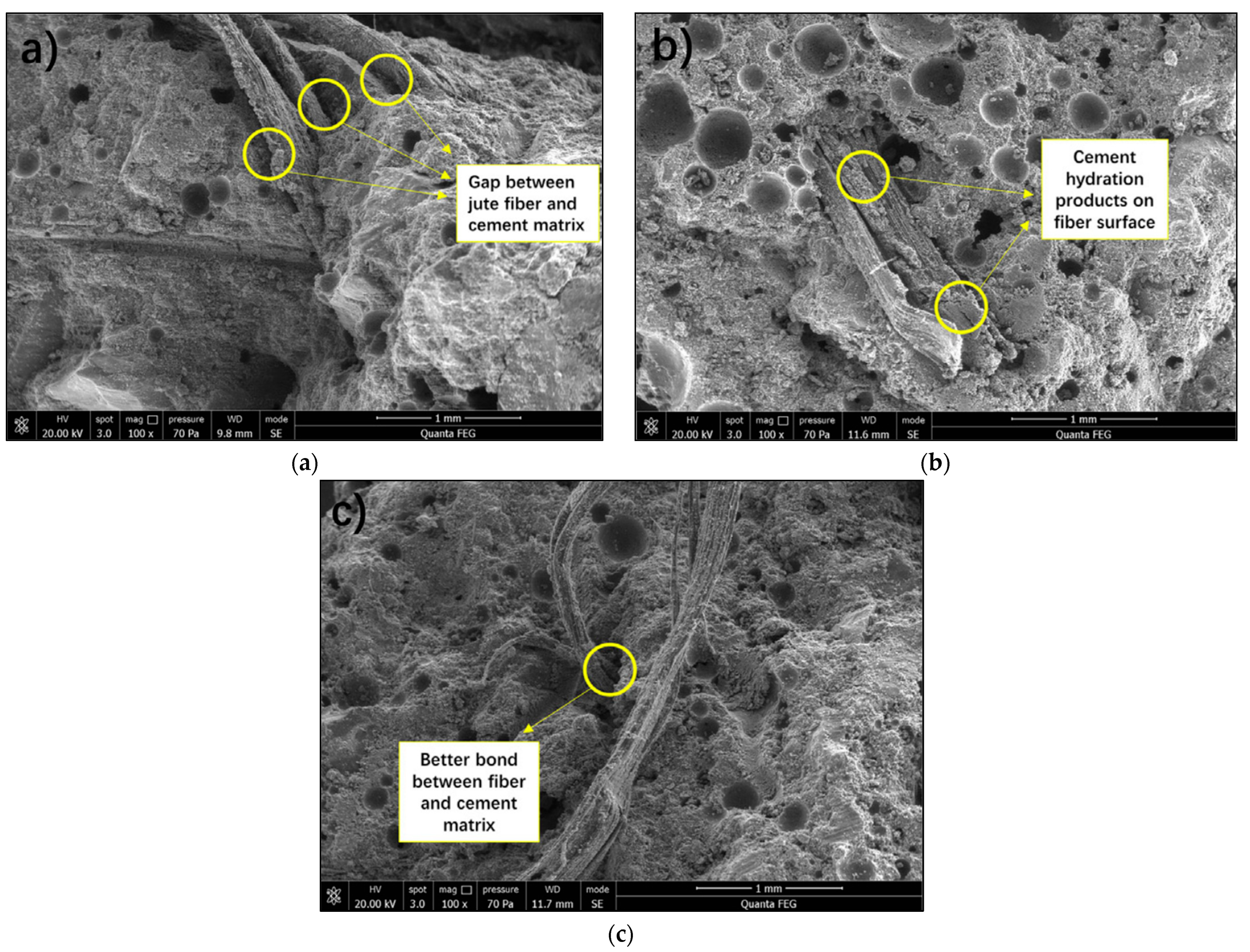

8.4. Effects of Fibre Treatments on the Microstructure of PFRSCC

9. Effects of SCMs on the Properties of PRSCC

9.1. Effects of SCMs on the Rheological Properties of PRSCC

9.2. Effects of SCMs on the Mechanical Properties of PRSCC

9.3. Effects of SCMs on the Durability of PRSCC

9.4. Effects of SCMs on the Microstructure of PRSCC

10. Life-Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Plant Fibre-Reinforced Concrete

11. Contributions of PFRSCC to the Construction Industry and Challenges

12. Limitations of the Study

13. Conclusions

13.1. Main Findings and Implications

- The effectiveness of plant fibres in SCC depends on the fibre type, fibre dosage, fibre length, fibre treatment, concrete mix proportion, and the incorporation of SCMs.

- Three main issues that hinder the extensive use of plant fibres in SCC are the hydrophilic nature of plant fibres, the fibre agglomeration effect, and the weak connection between plant fibres and the cement matrix.

- Using various plant fibres in SCC reduces the flowability, filling ability, and passing ability of SCC because of the high water absorption by plant fibres, the interlocking and friction between fibres and aggregates, and the fibre agglomeration effect. Adding plant fibres to SCC increases the viscosity and improves the segregation resistance of SCC due to the strong cohesion between plant fibres and the cement matrix. The reported decreases in slump flow vary from a slight reduction up to approximately 90%. The V-funnel flow time was reported to increase to approximately 145% when incorporating various plant fibres. The effect of plant fibres is not as significant in the L-box ratio when compared to the V-funnel flow time.

- The inclusion of plant fibres usually improves the mechanical properties of SCC because of the combined effects of fibres on crack-bridging and strain redistribution across the cross-section of SCC. The studies reported in the literature demonstrate a significant improvement in the split tensile strength, up to 65.6%, when plant fibres are incorporated into SCC. The effect of plant fibres on the flexural strength of SCC varies from a minor variation to as high as a 108% improvement.

- Embedding various plant fibres in SCC reduces the drying shrinkage and cracks because of the fibre bridging effect, while lowering the resistance to sulphate attack, acid attack, and freeze and thaw cycles, as well as increasing the water absorption rate of SCC due to the increased porosity of the mix.

- Using longer plant fibres significantly reduces the workability of SCC when compared to the shorter fibres due to greater fibre agglomeration and fibre–aggregate interlocking effects. For the mechanical properties, using the optimum fibre length maximises the crack-bridging effect while minimising the porosity of SCC. Short fibres cannot form effective crack-bridging due to weak bonding, whereas using excessively long fibres causes fibre agglomeration and increases porosity, reducing the long-term durability of concrete when compared to using shorter fibres.

- Alkaline treatments and polymer coatings of plant fibres improve the workability of SCC, while heat treatments have minimal effects on the rheology of SCC. Fibre treatments roughen the fibre surface and remove surface impurities, thereby improving mechanical interlocking and chemical compatibility, and significantly enhancing the mechanical properties of PFRSCC. Heat and alkaline treatments significantly improve the durability of PFRC when subjected to accelerated ageing conditions. Microstructure investigations reveal that alkaline treatments and fibre coatings demonstrate an improved surface roughness and adherence of cement hydration products, leading to stronger mechanical bonding.

- Using suitable SCMs alongside plant fibres helps counteract the reduced workability of PFRSCC. Using appropriate SCMs significantly improves the mechanical properties of PFRSCC by densifying the matrix through pozzolanic reactions, reducing the alkalinity of concrete to slow fibre degradation and enhancing fibre–matrix interfacial bonding. Using suitable SCMs improves the durability of concrete by consuming CH through pozzolanic reactions, refining pore structures, and reducing permeability. The SEM images show that blend mixes with SCMs exhibit dense matrices and strong fibre–matrix bonds, enhancing the durability and reducing the permeability of the mix.

13.2. Research Gaps and Future Perspectives

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACI | American Concrete Institute |

| CH | Calcium hydroxide |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| C-S-H | Calcium silicate hydrate |

| FA | Fly ash |

| HCl | Hydrochloric acid |

| ITZ | Interfacial transition zone |

| MK | Metakaolin |

| MOE | Modulus of elasticity |

| Na2CO3 | Sodium carbonate |

| NaOH | Sodium hydroxide |

| PFRC | Plant fibre-reinforced concrete |

| PFRSCC | Plant fibre-reinforced self-compacting concrete |

| PM | Pumice powder |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| RHA | Rice husk ash |

| SCC | Self-compacting concrete |

| SCM | Supplementary cementitious material |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

| SF | Silica fume |

| SG | Slag |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

References

- Suprakash, A.S.; Karthiyaini, S.; Shanmugasundaram, M. Future and scope for development of calcium and silica rich supplementary blends on properties of self-compacting concrete—A comparative review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 15, 5662–5681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayat, K.H. Workability, testing, and performance of self-consolidating concrete. ACI Mater. J. 1999, 96, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bani Ardalan, R.; Joshaghani, A.; Hooton, R.D. Workability retention and compressive strength of self-compacting concrete incorporating pumice powder and silica fume. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 134, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozière, E.; Granger, S.; Turcry, P.; Loukili, A. Influence of paste volume on shrinkage cracking and fracture properties of self-compacting concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2007, 29, 626–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snell, L. How Concrete Started—Part 1: Sun Dried Brick; American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MO, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, R.; Sobuz, M.H.R.; Akid, A.S.M.; Awall, M.R.; Houda, M.; Saha, A.; Meraz, M.M.; Islam, M.S.; Sutan, N.M. Eco-friendly self-consolidating concrete production with reinforcing jute fiber. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 63, 105519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hari, R.; Mini, K.M. Mechanical and durability properties of sisal-Nylon 6 hybrid fibre reinforced high strength SCC. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 204, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hadithi, A.I.; Hilal, N.N. The possibility of enhancing some properties of self-compacting concrete by adding waste plastic fibers. J. Build. Eng. 2016, 8, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haris, N.I.N.; Hassan, M.Z.; Ilyas, R.A.; Suhot, M.A.; Sapuan, S.M.; Dolah, R.; Mohammad, R.; Asyraf, M.R.M. Dynamic mechanical properties of natural fiber reinforced hybrid polymer composites: A review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 19, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawaid, M.; Siengchin, S. Hybrid Composites: A Versatile Materials for Future. Appl. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uğur, A.E.; Ünal, A. Assessing the structural behavior of reinforced concrete beams produced with macro synthetic fiber reinforced self-compacting concrete. Structures 2022, 38, 1226–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kina, C.; Turk, K. Bond strength of reinforcing bars in hybrid fiber-reinforced SCC with binary, ternary and quaternary blends of steel and PVA fibers. Mater. Struct. 2021, 54, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, K.; Cicek, N.; Katlav, M.; Donmez, I.; Turgut, P. Electrical conductivity and heating performance of hybrid steel fiber-reinforced SCC: The role of high-volume fiber and micro fiber length. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 76, 107392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, X.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, Y. Experimental study and prediction model for flexural behavior of reinforced SCC beam containing steel fibers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 93, 644–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Dieb, A.S.; Reda Taha, M.M. Flow characteristics and acceptance criteria of fiber-reinforced self-compacted concrete (FR-SCC). Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 27, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atewi, Y.R.; Hasan, M.F.; Güneyisi, E. Fracture and permeability properties of glass fiber reinforced self-compacting concrete with and without nanosilica. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 226, 993–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganta, J.K.; Seshagiri Rao, M.V.; Mousavi, S.S.; Srinivasa Reddy, V.; Bhojaraju, C. Hybrid steel/glass fiber-reinforced self-consolidating concrete considering packing factor: Mechanical and durability characteristics. Structures 2020, 28, 956–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Jin, Z.; Long, G.; Chen, L.; Fu, Q.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xiong, C. Impact resistance of steel fiber-reinforced self-compacting concrete (SCC) at high strain rates. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 38, 102212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Aviña, J.V.; Juárez-Alvarado, C.A.; Terán-Torres, B.T.; Mendoza-Rangel, J.M.; Durán-Herrera, A.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, J.A. Influence of fibers distribution on direct shear and flexural behavior of synthetic fiber-reinforced self-compacting concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 330, 127255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gali, S.; Sharma, D.; Subramaniam Kolluru, V.L. Influence of Steel Fibers on Fracture Energy and Shear Behavior of SCC. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2018, 30, 04018295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, G.J.; Mousavi, S.S.; Bhojaraju, C. Influence of thermal cycles and high-temperature exposures on the residual strength of hybrid steel/glass fiber-reinforced self-consolidating concrete. Structures 2023, 55, 1532–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hadithi, A.I.; Noaman, A.T.; Mosleh, W.K. Mechanical properties and impact behavior of PET fiber reinforced self-compacting concrete (SCC). Compos. Struct. 2019, 224, 111021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanem, S.Y.; Bowling, J.; Sun, Z. Mechanical Properties of Hybrid Synthetic Fiber Reinforced Self-Consolidating Concrete. Compos. Part C Open Access 2021, 5, 100154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaqin, C.; Haq, S.U.; Iqbal, S.; Khan, I.; Room, S.; Khan, S.A. Performance evaluation of indented macro synthetic polypropylene fibers in high strength self-compacting concrete (SCC). Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbdelAleem, B.H.; Ismail, M.K.; Hassan, A.A.A. The combined effect of crumb rubber and synthetic fibers on impact resistance of self-consolidating concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 162, 816–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaliq, W.; Kodur, V. Thermal and mechanical properties of fiber reinforced high performance self-consolidating concrete at elevated temperatures. Cem. Concr. Res. 2011, 41, 1112–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaee, K.; Khayat, K.H. Use of hybrid fibers and shrinkage mitigating materials in SCC for repair applications. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 413, 134903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, K.; Bassurucu, M.; Bitkin, R.E. Workability, strength and flexural toughness properties of hybrid steel fiber reinforced SCC with high-volume fiber. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 266, 120944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Lu, Z.; Wang, D. Working and mechanical properties of waste glass fiber reinforced self-compacting recycled concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 439, 137172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooqi, M.U.; Ali, M. Contribution of plant fibers in improving the behavior and capacity of reinforced concrete for structural applications. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 182, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittner, C.M.; Oettel, V. Fiber Reinforced Concrete with Natural Plant Fibers—Investigations on the Application of Bamboo Fibers in Ultra-High Performance Concrete. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.C. Hydration and internal curing properties of plant-based natural fiber-reinforced cement composites. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, B.; Azab, M.; Ahmed, H.; Kurda, R.; El Ouni, M.H.; Elhag, A.B. Investigation of physical, strength, and ductility characteristics of concrete reinforced with banana (Musaceae) stem fiber. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 61, 105024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Yin, Y.; Gong, Y.; Wang, L. Mechanical properties of jute fiber-reinforced high-strength concrete. Struct. Concr. 2020, 21, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaid, A.; Dawood, M.; Seracino, R.; Bobko, C. Mechanical properties of kenaf fiber reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 1991–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Lara, J.F.; Flores-Johnson, E.A.; Valadez-Gonzalez, A.; Herrera-Franco, P.J.; Carrillo, J.G.; Gonzalez-Chi, P.I.; Li, Q.M. Mechanical Properties of Natural Fiber Reinforced Foamed Concrete. Materials 2020, 13, 3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Z.; Mao, S.; Zheng, Y.; Liang, K. Pre-treated corn straw fiber for fiber-reinforced concrete preparation with high resistance to chloride ions corrosion. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 19, e02368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetty, C.A.; Krahl, P.A.; Almeida, L.C.; Trautwein, L.M.; Siqueira, G.H.; de Andrade Silva, F. Interfacial mechanics of steel fibers in a High-Strength Fiber-Reinforced Self Compacting Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 301, 124344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjeev, J.; Sai Nitesh, K.J.N. Study on the effect of steel and glass fibers on fresh and hardened properties of vibrated concrete and self-compacting concrete. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 27, 1559–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merta, I.; Tschegg, E.K. Fracture energy of natural fibre reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 40, 991–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iluţiu-Varvara, D.-A.; Aciu, C. Metallurgical Wastes as Resources for Sustainability of the Steel Industry. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signorini, C.; Marinelli, S.; Volpini, V.; Nobili, A.; Radi, E.; Rimini, B. Performance of concrete reinforced with synthetic fibres obtained from recycling end-of-life sport pitches. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 53, 104522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Azam, W. Natural resource scarcity, fossil fuel energy consumption, and total greenhouse gas emissions in top emitting countries. Geosci. Front. 2024, 15, 101757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.-H.; Tsai, Y.-S.; Yang, P.-Y. A Review of Glass Fibre Recycling Technology Using Chemical and Mechanical Separation of Surface Sizing Agents. Recycling 2021, 6, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, H.; Alattar, A.; Tayeh, B.; Yahaya, F.; Thomas, B. Effect of recycled waste glass on the properties of high-performance concrete: A critical review. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, M.; Shankar, S.; Goel, D.; Singh, S.; Rahul, J.; Rachna, K.; Singh, J. Microplastics pollution in the marine environment: A review of sources, impacts and mitigation. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 209, 117109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capolupo, M.; Sørensen, L.; Jayasena, K.D.R.; Booth, A.M.; Fabbri, E. Chemical composition and ecotoxicity of plastic and car tire rubber leachates to aquatic organisms. Water Res. 2020, 169, 115270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omotehinse, A.O.; Ako, B.D. The environmental implications of the exploration and exploitation of solid minerals in Nigeria with a special focus on Tin in Jos and Coal in Enugu. J. Sustain. Min. 2019, 18, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomayri, T.; Ali, B. Effect of plant fiber type and content on the strength and durability performance of high-strength concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 394, 132166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niels de Beus, M.C.; Barth, M. Carbon Footprint and Sustainability of Different Natural Fibres for Biocomposites and Insulation Material; Nova-Institut GmbH: Hürth, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nwankwo, C.O.; Mahachi, J.; Olukanni, D.O.; Musonda, I. Natural fibres and biopolymers in FRP composites for strengthening concrete structures: A mixed review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 363, 129661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragoubi, M.; Bienaimé, D.; Molina, S.; George, B.; Merlin, A. Impact of corona treated hemp fibres onto mechanical properties of polypropylene composites made thereof. Ind. Crops Prod. 2010, 31, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyanarayana, K.G.; Guimarães, J.L.; Wypych, F. Studies on lignocellulosic fibers of Brazil. Part I: Source, production, morphology, properties and applications. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2007, 38, 1694–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, H.M.; Shi, J.; Al Jawahery, M.S.; Majdi, A.; Yousif, S.T.; Kaplan, G. Application of natural fibres in cement concrete: A critical review. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 35, 105833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudayu, A.D.; Steuernagel, L.; Meiners, D.; Gideon, R. Effect of surface treatment on moisture absorption, thermal, and mechanical properties of sisal fiber. J. Ind. Text. 2020, 51, 2853S–2873S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yimer, T.; Gebre, A. Effect of Fiber Treatments on the Mechanical Properties of Sisal Fiber-Reinforced Concrete Composites. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2023, 2023, 2293857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.A.; Joekes, I. Tire rubber–sisal composites: Effect of mercerization and acetylation on reinforcement. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2003, 89, 2507–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Meyer, C. Improving degradation resistance of sisal fiber in concrete through fiber surface treatment. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 289, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Ma, S.; Thomas, D.S.G. Correlation between hydration of cement and durability of natural fiber-reinforced cement composites. Corros. Sci. 2016, 106, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poongodi, K.; Murthi, P. Impact strength enhancement of banana fibre reinforced lightweight self-compacting concrete. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 27, 1203–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Farooq, S.H.; Usman, M.; Khan, M.; Ahmad, A.; Aslam, F.; Yousef, R.A.; Abduljabbar, H.A.; Sufian, M. Effect of Coconut Fiber Length and Content on Properties of High Strength Concrete. Materials 2020, 13, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshaid, H.; Mishra, R.K.; Raza, A.; Hussain, U.; Rahman, M.L.; Nazari, S.; Chandan, V.; Muller, M.; Choteborsky, R. Natural Cellulosic Fiber Reinforced Concrete: Influence of Fiber Type and Loading Percentage on Mechanical and Water Absorption Performance. Materials 2022, 15, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Wang, X. Compressive and flexural properties of hemp fiber reinforced concrete. Fibers Polym. 2004, 5, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Panov, V.; Han, S.; Yun, K.-K. Natural fiber-reinforced shotcrete mixture: Quantitative assessment of the impact of fiber on fresh and plastic shrinkage cracking properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 366, 130032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, W-65–W-94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohanty, M.; Mohapatra, S.S.; Nayak, S. Efficacy of C&D waste in base/subbase layers of pavement—current trends and future prospectives: A systematic review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 340, 127726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, G.J.M.; Cox, J.A.; Hulme, A.; Naweed, A.; Salmon, P.M. What factors influence risk at rail level crossings? A systematic review and synthesis of findings using systems thinking. Saf. Sci. 2021, 138, 105207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savaresi, A. The Paris Agreement: A new beginning? J. Energy Nat. Resour. Law 2016, 34, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Gao, W.; Wang, F.; Zhou, N.; Kammen, D.M.; Ying, X. A Survey of the Status and Challenges of Green Building Development in Various Countries. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narong, D.K.; Hallinger, P. A Keyword Co-Occurrence Analysis of Research on Service Learning: Conceptual Foci and Emerging Research Trends. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Ahmad, A.; Ostrowski, K.A.; Aslam, F.; Joyklad, P. A scientometric review of waste material utilization in concrete for sustainable construction. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2021, 15, e00683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization; Agricultural Markets Analysis Team. Jute, Kenaf, Sisal, Abaca, Coir and Allied Fibres Statistical Bulletin 2024; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Textile Exchange. Materials Market Report 2024: The Global Fibre Market; Textile Exchange: Lamesa, TX, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Derdour, D.; Behim, M.; Mohammed, B. Effect of date palm and polypropylene fibers on the characteristics of self-compacting concrete: Comparative study. Frat. Integrità Strutt. 2023, 17, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bediako, M.; Ametefe, T.K.; Asante, N.; Adumatta, S. Incorporation of natural coconut fibers in concrete for sustainable construction: Mechanical and durability behavior. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Shen, A.; Cheng, Q.; Cai, Y.; Ren, G.; Pan, H.; Deng, S. A review of recent developments in application of plant fibers as reinforcements in concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 419, 138265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, M.; Abenojar, J.; Martínez, M.Á. Recent Progress in Hybrid Biocomposites: Mechanical Properties, Water Absorption, and Flame Retardancy. Materials 2020, 13, 5145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djafari Petroudy, S.R. 3-Physical and mechanical properties of natural fibers. In Advanced High Strength Natural Fibre Composites in Construction; Fan, M., Fu, F., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2017; pp. 59–83. [Google Scholar]

- Chahinez, A.; Belkadi, A.; Yacine, A.; Kessal, O. Experimental study on flexural creep of self-compacting concrete reinforced with vegetable and synthetic fibers. REM-Int. Eng. J. 2023, 76, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedan, D.; Pagnoux, C.; Smith, A.; Chotard, T. Propriétés mécaniques de matériaux enchevêtrés à base de fibre de chanvre et matrice cimentaire. In Proceedings of the CFM 2007-18ème Congrès Français de Mécanique, Grenoble, France, 27–31 August 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tengli, P.N.; Hassan, M.M.; Gobinath, R.; Saravanamoorthi, P.; Veeramachaneni, V. Strength Analysis of Self-Consolidating Concrete Using Jute Fiber and Coconut Shell Aggregates Using Luongo Attention Based Recurrent Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2025 3rd International Conference on Integrated Circuits and Communication Systems (ICICACS), Raichur, India, 21–22 February 2025; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.; Ali, A.; Bibi, T.; Wadood, F. Mechanical investigations of the durability performance of sustainable self-compacting and anti-spalling composite mortars. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 82, 108319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, R.; Raman, S.N.; Divyah, N.; Subramanian, C.; Vijayaprabha, C.; Praveenkumar, S. Fresh and mechanical characteristics of roselle fibre reinforced self-compacting concrete incorporating fly ash and metakaolin. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 290, 123209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wei, Y.; Meng, K.; Zhao, L.; Zhu, B.; Wei, B. Mechanical properties and stress-strain relationship of surface-treated bamboo fiber reinforced lightweight aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 424, 135914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Tang, J.; Li, Z.; Zhou, T.; Xiong, T. Experimental study on the static properties of bamboo fiber reinforced ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC). Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 453, 138974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlv, P.; Saha, P.; Pancharathi, R. Self compacting reinforced concrete beams strengthened with natural fiber under cyclic loading. Comput. Concr. 2016, 17, 597–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, U.; Majeed Sheikh, I. Investigating self-compacting-concrete reinforced with steel & coir fiber. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 45, 4948–4953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Shi, M.; Lee, S.; Lin, R.; Wang, K.-J.; Wang, X.-Y. Application of porous luffa fiber as a natural internal curing material in high-strength mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 455, 139169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivek, S.S.; Karthikeyan, B.; Bahrami, A.; Selvaraj, S.K.; Rajasakthivel, R.; Azab, M. Impact and durability properties of alccofine-based hybrid fibre-reinforced self-compacting concrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 19, e02275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poongodi, K.; Murthi, P.; Gobinath, R. Evaluation of ductility index enhancement level of banana fibre reinforced lightweight self-compacting concrete beam. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 39, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laifa, W.; Behim, M.; Turatsinze, A.; Ali-Boucetta, T. Caractérisation d’un béton autoplaçant avec addition de laitier cristallisé et renforcé par des fibres de polypropylène et de diss. Synthèse Rev. Sci. Technol. 2014, 29, 100–110. [Google Scholar]

- Dávila-Pompermayer, R.; Lopez-Yepez, L.G.; Valdez-Tamez, P.; Juárez, C.A.; Durán-Herrera, A. Lechugilla natural fiber as internal curing agent in self compacting concrete (SCC): Mechanical properties, shrinkage and durability. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 112, 103686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azwa, Z.N.; Yousif, B.F.; Manalo, A.C.; Karunasena, W. A review on the degradability of polymeric composites based on natural fibres. Mater. Des. 2013, 47, 424–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motaung, T.E.; Linganiso, L.Z. Critical review on agrowaste cellulose applications for biopolymers. Int. J. Plast. Technol. 2018, 22, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, M.J.; Thomas, S. Biofibres and biocomposites. Carbohydr. Polym. 2008, 71, 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summerscales, J.; Dissanayake, N.P.J.; Virk, A.S.; Hall, W. A review of bast fibres and their composites. Part 1—Fibres as reinforcements. Compos. Part A-Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2010, 41, 1329–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.R.; Santiago de Oliveira Patrício, P.; Soares dos Santos, F.; Monteiro, M.L.; de Carvalho Urashima, D.; de Souza Rodrigues, C. Effects of the climatic conditions of the southeastern Brazil on degradation the fibers of coir-geotextile: Evaluation of mechanical and structural properties. Geotext. Geomembr. 2014, 42, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bledzki, A.K.; Gassan, J. Composites reinforced with cellulose based fibres. Prog. Polym. Sci. 1999, 24, 221–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuqua, M.A.; Huo, S.; Ulven, C.A. Natural Fiber Reinforced Composites. Polym. Rev. 2012, 52, 259–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.J.; Yousif, B.F.; Low, K.O. The effects of alkali treatment on the interfacial adhesion of bamboo fibres. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part L J. Mater. Des. Appl. 2010, 224, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Meyer, C. Degradation mechanisms of natural fiber in the matrix of cement composites. Cem. Concr. Res. 2015, 73, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavitha, S.; Venkatesan, G.; Avudaiappan, S.; Zhang, C. Seismic behavior of steel and sisal fiber reinforced beam-column joint under cyclic loading. Struct. Eng. Mech. Int. J. 2023, 88, 481–492. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, P.S.; Satyanarayana, K.G. Structure and properties of some vegetable fibres. J. Mater. Sci. 1984, 19, 3925–3934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthilkumar, K.; Saba, N.; Rajini, N.; Chandrasekar, M.; Jawaid, M.; Siengchin, S.; Alotman, O.Y. Mechanical properties evaluation of sisal fibre reinforced polymer composites: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 174, 713–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Lu, S.; Pan, L.; Luo, Q.; Yang, J.; Hou, L.; Li, Y.; Yu, J. Enhanced thermal and mechanical properties of polypropylene composites with hyperbranched polyester grafted sisal microcrystalline. Fibers Polym. 2016, 17, 2153–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, M.J.; Anandjiwala, R.D. Recent developments in chemical modification and characterization of natural fiber-reinforced composites. Polym. Compos. 2008, 29, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, P.; Gupta, M. A review on the properties of natural fibres and its bio-composites: Effect of alkali treatment. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part L 2019, 234, 198–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardanuy, M.; Claramunt, J.; Toledo Filho, R.D. Cellulosic fiber reinforced cement-based composites: A review of recent research. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 79, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjay, M.R.; Arpitha, G.R.; Naik, L.; Gopalakrishna, K.; Yogesha, B. Applications of Natural Fibers and Its Composites: An Overview. Nat. Resour. 2016, 07, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashas Gowda, T.G.; Sanjay, M.R.; Subrahmanya Bhat, K.; Madhu, P.; Senthamaraikannan, P.; Yogesha, B. Polymer matrix-natural fiber composites: An overview. Cogent Eng. 2018, 5, 1446667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Kanstad, T.; Jacobsen, S.; Ji, G. Bonding property between fiber and cementitious matrix: A critical review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 378, 131169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, M.; Dwivedi, G. Effect of fiber treatment on flexural properties of natural fiber reinforced composites: A review. Egypt. J. Pet. 2018, 27, 775–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, A.K.; Misra, M.; Drzal, L.T. Surface modifications of natural fibers and performance of the resulting biocomposites: An overview. Compos. Interfaces 2001, 8, 313–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisa, O.-N.; Raditya, A.; Triastuti; Ananto, N.; Syamsunur, D.; Amiri, O. Sago palm fibers and ggbfs for sustainable high-tensile-strength self-compacting concrete. GEOMATE J. 2025, 28, 44–55. [Google Scholar]

- Ede, A.; Olofinnade, O.; Joshua, O.; Nduka, D.; Oshogbunu, O. Influence of bamboo fiber and limestone powder on the properties of self compacting concrete. Cogent Eng. 2020, 7, 1721410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chairunnisa, N.; Nurwidayati, R.; Madani, G. The effect of natural fiber (banana fiber) on the mechanical properties of self-compacting concrete. J. Appl. Eng. Sci. 2022, 20, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, A.; Saloma; Hanafiah, H.; Anen, M. Physical and mechanical properties of self-compacting concrete (SCC) with coconut fiber and polypropylene. AIP Conf. Proc. 2023, 2544, 020019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periyasamy, M.; Kanagaraj, R. Fiber reinforced self compacting concrete workability properties prediction and optimization of mix using machine learning modeling. Matéria 2024, 29, e20230309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Z.; Peng, C.; Sun, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, C.; Morsy, A.M.; Wang, X. Properties of sustainable self-compacting concrete containing activated jute fiber and waste mineral powders. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 19, 1740–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolga Cogurcu, M. Investigation of mechanical properties of red pine needle fiber reinforced self-compacting ultra high performance concrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 16, e00970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, C.; Kannan, N. Degradation study on sisal fibre reinforced self compacting concrete. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. 2018, 9, 784–794. [Google Scholar]

- Vivek, S.S.; Prabalini, C. Experimental and microstructure study on coconut fibre reinforced self compacting concrete (CFRSCC). Asian J. Civ. Eng. 2021, 22, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tioua, T.; Kriker, A.; Barluenga, G.; Palomar, I. Influence of date palm fiber and shrinkage reducing admixture on self-compacting concrete performance at early age in hot-dry environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 154, 721–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathia, R.; Vijayalakshmi, R. Fresh and mechanical property of caryota-urens fiber reinforced flowable concrete. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 15, 3647–3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milena, B.E.; José, A.; Freitas, E. Dwarf-green coconut fibers: A versatile natural renewable raw bioresource. Bioresources 2010, 4, 2478–2501. [Google Scholar]

- Barreto, A.C.H.; Esmeraldo, M.A.; Rosa, D.S.; Fechine, P.B.A.; Mazzetto, S.E. Cardanol biocomposites reinforced with jute fiber: Microstructure, biodegradability, and mechanical properties. Polym. Compos. 2010, 31, 1928–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Manchado, M.A.; Arroyo, M.; Biagiotti, J.; Kenny, J.M. Enhancement of mechanical properties and interfacial adhesion of PP/EPDM/flax fiber composites using maleic anhydride as a compatibilizer. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2003, 90, 2170–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, B.N.; Rana, A.K.; Mishra, S.C.; Mishra, H.K.; Nayak, S.K.; Tripathy, S.S. Novel low-cost jute–polyester composite. ii. SEM observation of the fractured surfaces. Polym. -Plast. Technol. Eng. 2000, 39, 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obi Reddy, K.; Uma Maheswari, C.; Shukla, M.; Song, J.I.; Varada Rajulu, A. Tensile and structural characterization of alkali treated Borassus fruit fine fibers. Compos. Part B Eng. 2013, 44, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.M.; Wang, H.; Lau, K.T.; Cardona, F. Chemical treatments on plant-based natural fibre reinforced polymer composites: An overview. Compos. Part B Eng. 2012, 43, 2883–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylsamy, G.; Krishnasamy, P. A Review on Natural Plant Fiber Epoxy and Polyester Composites—Coating and Performances. J. Nat. Fibers 2022, 19, 12772–12790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.R.; Silva, F.d.A.; Lima, P.R.L.; Toledo Filho, R.D. Effect of fiber treatments on the sisal fiber properties and fiber–matrix bond in cement based systems. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 101, 730–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Cui, S.; Xu, F.; Tuo, T. Impact of leaf fibre modification methods on compatibility between leaf fibres and cement-based materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 94, 502–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidelis, M.E.A.; Toledo Filho, R.D.; Silva, F.d.A.; Mechtcherine, V.; Butler, M.; Hempel, S. The effect of accelerated aging on the interface of jute textile reinforced concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2016, 74, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onésippe, C.; Passe-Coutrin, N.; Toro, F.; Delvasto, S.; Bilba, K.; Arsène, M.-A. Sugar cane bagasse fibres reinforced cement composites: Thermal considerations. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2010, 41, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirawattanasomkul, T.; Likitlersuang, S.; Wuttiwannasak, N.; Ueda, T.; Zhang, D.; Voravutvityaruk, T. Effects of Heat Treatment on Mechanical Properties of Jute Fiber–Reinforced Polymer Composites for Concrete Confinement. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2020, 32, 04020363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, T.; Reddy, H.N.J. Pretreatment of Woven Jute FRP Composite and Its Use in Strengthening of Reinforced Concrete Beams in Flexure. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2013, 2013, 128158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, M.M.; Adefrs Taye, E.; Roether, J.A.; Tilahun Redda, D.; Boccaccini, A.R. A Review on Natural Fiber-Reinforced Geopolymer and Cement-Based Composites. Materials 2020, 13, 4603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Committee for Standardization. Testing Fresh Concrete—Part 8: Self-Compacting Concrete—Slump Flow Test; CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Committee for Standardization. Testing Fresh Concrete—Part 9: Self-Compacting Concrete—V Funnel Test; CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Committee for Standardization. Testing Fresh Concrete—Part 10: Self-Compacting Concrete—L Box Test; CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Committee for Standardization. Testing Fresh Concrete—Part 12: Self-Compacting Concrete—J-Ring Test; CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Faraj, R.H.; Hama Ali, H.F.; Sherwani, A.F.H.; Hassan, B.R.; Karim, H. Use of recycled plastic in self-compacting concrete: A comprehensive review on fresh and mechanical properties. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 30, 101283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Committee for Standardization. Testing Fresh Concrete—Part 11: Self-Compacting Concrete—Sieve Segregation Test; CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Saingam, P.; Chatveera, B.; Promsawat, P.; Hussain, Q.; Nawaz, A.; Makul, N.; Sua-iam, G. Synergizing Portland Cement, high-volume fly ash and calcined calcium carbonate in producing self-compacting concrete: A comprehensive investigation of rheological, mechanical, and microstructural properties. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkadi, A.; Aggoun, S.; Amouri, C.; Geuttala, A.; Houari, H. Experimental investigation on the properties and performance of self-compacting concrete with vegetable and syntetic fibers. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Mechanics and Materials in Design (M2D2017), Albufeira, Portugal, 11–15 June 2017; pp. 919–924. [Google Scholar]

- Odeyemi, S.O.; Adisa, M.A.; Atoyebi, O.D.; Adesina, A.; Lukman, A.; Olakiitan, A. Variability Analysis of Compressive and Flexural Performance of Coconut Fibre Reinforced Self-Compacting Concrete. Int. J. Eng. Res. Afr. 2023, 66, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tioua, T.; Kriker, A.; Salhi, A.; Barluenga, G. Effect of hot-dry environment on fiber-reinforced self-compacting concrete. AIP Conf. Proc. 2016, 1758, 030024. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.-S.; Lee, H.-J.; Choi, Y. Mechanical properties of natural fiber-reinforced normal strength and high-fluidity concretes. Comput. Concr. 2013, 11, 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavitha, S.; Govindan, V.; Avudaiappan, S.; Saavedra Flores, E. Mechanical and flexural performance of self compacting concrete with natural fiber. Rev. Construcción 2020, 19, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Schutter, G. Self-Compacting Concrete; Whittles Publishing Ltd.: Dunbeath, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- European Federation of National Associations Representing Producers and Applicators of Specialist Building Products for Concrete. The European Guidelines for Self-Compacting Concrete: Specification, Production, and Use; EFNARC: Singapore, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Martinie, L.; Rossi, P.; Roussel, N. Rheology of fiber reinforced cementitious materials: Classification and prediction. Cem. Concr. Res. 2010, 40, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velumani, S.K.; Venkatraman, S. Assessing the Impact of Fly Ash and Recycled Concrete Aggregates on Fibre-Reinforced Self-Compacting Concrete Strength and Durability. Processes 2024, 12, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, J.; Zhou, Z.; Deifalla, A.F. Steel Fiber Reinforced Self-Compacting Concrete: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2023, 17, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soo-Duck, H.; Khayat, K.H.; Bonneau, O. Performance-Based Specifications of Self-Consolidating Concrete Used in Structural Applications. ACI Mater. J. 2006, 103, 121–129. [Google Scholar]

- Lakhiar, M.T.; Mohamad, N.; Abdul Samad, A.A.; Muthusamy, K.; Othuman Mydin, M.A.; Goh, W.I.; George, S. Effect of banana skin powder and coir fibre on properties and flexural behaviour of precast SCC beam. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2021, 14, 1193–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, R.; Thenmozhi, R.; Raman, S.N.; Subramanian, C. Characterization of eco-friendly steel fiber-reinforced concrete containing waste coconut shell as coarse aggregates and fly ash as partial cement replacement. Struct. Concr. 2020, 21, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambhir, M.L. Concrete Technology: Theory and Practice; Tata McGraw-Hill Education: Columbus, OH, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yehia, S.; Douba, A.; Abdullahi, O.; Farrag, S. Mechanical and durability evaluation of fiber-reinforced self-compacting concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 121, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.M. Fibre-reinforced concrete: State-of-the-art-review on bridging mechanism, mechanical properties, durability, and eco-economic analysis. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Chen, Z.; Xie, Z.; Wei, L.; Hua, J.; Huang, L.; Yap, P.-S. Recent developments on natural fiber concrete: A review of properties, sustainability, applications, barriers, and opportunities. Dev. Built Environ. 2023, 16, 100255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iman, M.A.; Mohamad, N.; Raain, F.; Sufian, A.S.; Mydin, A.; Abdul Samad, A.A. Fresh State and Mechanical Properties of SCC-POFA-CF Mixture. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 498, 012034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Cheng, L.; Zhou, D. Study on the flexural performance and brittle fracture characteristics of steel fiber-reinforced concrete exposed to cryogenic temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 432, 136604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Qin, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Dong, Q.; Li, K.; Wang, X. Properties prediction for self-compacting concrete incorporating activated fiber and stone chips. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 33, 104615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Zhou, D.; Ashour, A.; Han, B.; Ou, J. Flexural toughness and calculation model of super-fine stainless wire reinforced reactive powder concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2019, 104, 103367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalaratnam, V.S.; Gettu, R. On the characterization of flexural toughness in fiber reinforced concretes. Cem. Concr. Compos. 1995, 17, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Wang, Q.; Shi, Q. Flexural toughness and its evaluation method of ultra-high performance concrete cured at room temperature. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 71, 106516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, J.; Burduhos-Nergis, D.D.; Arbili, M.M.; Alogla, S.M.; Majdi, A.; Deifalla, A.F. A Review on Failure Modes and Cracking Behaviors of Polypropylene Fibers Reinforced Concrete. Buildings 2022, 12, 1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Sharma, A.; Ray, S. Characterization of crack-bridging and size effect on ultra-high performance fibre reinforced concrete under fatigue loading. Int. J. Fatigue 2024, 182, 108158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaguru, P.N.; Shah, S.P. Fibre-Reinforced Cement Composites; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM C1018-97; Standard Test Method for Flexural Toughness and First-Crack Strength of Fiber-Reinforced Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1997.

- Özalp, F.; Yilmaz, H.D.; Akcay, B. Mechanical properties and impact resistance of concrete composites with hybrid steel fibers. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng. 2022, 16, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranade, R.; Li, V.C.; Heard, W.F.; Williams, B.A. Impact resistance of high strength-high ductility concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2017, 98, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.H.; Arockiasamy, M.; Balaguru, P.; Ball, C.G.; Ball Jr, H.P.; Batson, G.B.; Bentur, A.; Craig, R.J.; Criswell, M.E.; Freedman, S. Measurement of Properties of Fiber Reinforced Concrete; American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Laverde, V.; Marin, A.; Benjumea, J.M.; Rincón Ortiz, M. Use of vegetable fibers as reinforcements in cement-matrix composite materials: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 340, 127729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassios, K.G. A Review of the Pull-Out Mechanism in the Fracture of Brittle-Matrix Fibre-Reinforced Composites. Adv. Compos. Lett. 2007, 16, 096369350701600102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, L.A.; Nguyen, G.D.; Bui, H.H.; Sheikh, A.H.; Kotousov, A. Incorporation of micro-cracking and fibre bridging mechanisms in constitutive modelling of fibre reinforced concrete. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2019, 133, 103732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, T. Concrete Durability; Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Omikrine Metalssi, O.; Quiertant, M.; Jabbour, M.; Baroghel-Bouny, V. Effect of Exposure Conditions on Mortar Subjected to an External Sulfate Attack. Materials 2024, 17, 3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Bao, Y.; Yao, Y. Influence of HCl corrosion on the mechanical properties of concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2005, 35, 584–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tamimi, A.; Sonebi, M. Assessment of self-compacting concrete immersed in acidic solutions. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2003, 15, 354–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, P.C.; O’Connor, A. Comparing the durability of self-compacting concretes and conventionally vibrated concretes in chloride rich environments. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 120, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijay, R.; Vinod, A.; Lenin Singaravelu, D.; Sanjay, M.R.; Siengchin, S. Characterization of chemical treated and untreated natural fibers from Pennisetum orientale grass- A potential reinforcement for lightweight polymeric applications. Int. J. Lightweight Mater. Manuf. 2021, 4, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madraszewski, S.; Sielaff, A.M.; Stephan, D. Acid attack on concrete—Damage zones of concrete and kinetics of damage in a simulating laboratory test method for wastewater systems. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 366, 130121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, K.; Naidu, S.V. Chemical Resistance of Sisal/Glass Reinforced Unsaturated Polyester Hybrid Composites. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2007, 26, 373–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastali, M.; Kinnunen, P.; Dalvand, A.; Mohammadi Firouz, R.; Illikainen, M. Drying shrinkage in alkali-activated binders—A critical review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 190, 533–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Wang, T.; Wang, H.; Yu, Z.; Shen, X. A state-of-the-art review on the utilization of calcareous fillers in the alkali activated cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 357, 129348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, E.; Leivo, M. Cracking risks associated with early age shrinkage. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2004, 26, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golewski, G.L. Assessing of water absorption on concrete composites containing fly ash up to 30% in regards to structures completely immersed in water. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 19, e02337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, S.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, M. Water absorption behaviour of concrete: Novel experimental findings and model characterization. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 53, 104602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabir, B.B.; Wild, S.; O’Farrell, M. A water sorptivity test for mortar and concrete. Mater. Struct./Mater. Constr. 1998, 31, 568–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltais, Y.; Samson, E.; Marchand, J. Predicting the durability of Portland cement systems in aggressive environments—Laboratory validation. Cem. Concr. Res. 2004, 34, 1579–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.M.; Fuentes, C.A.; Van Vuure, A.W. Moisture sorption and swelling of flax fibre and flax fibre composites. Compos. Part B Eng. 2022, 231, 109538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neha, H.; Hassan, R.; Shaji, S.; Sreelakshmi, P.V.; Abin Thomas, C.A. Development of SCC Mix Using Jute and Coir as Additives. In Proceedings of the SECON’19, Angamaly, India, 15–16 May 2020; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 237–246. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Chen, X.; Zhang, N.; Wang, X.; Diao, H. Experimental and numerical research on triaxial mechanical behavior of self-compacting concrete subjected to freeze–thaw damage. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 288, 123110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, F.; Sicat, E.; Zhang, D.; Ueda, T. Stress Analysis for Concrete Materials under Multiple Freeze-Thaw Cycles. J. Adv. Concr. Technol. 2015, 13, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merta, I.; Serjun, V.Z.; Pranjić, A.M.; Šajna, A.; Štefančič, M.; Poletanović, B.; Ameri, F.; Mladenović, A. Investigating the synergistic impact of freeze-thaw cycles and deicing salts on the properties of cementitious composites incorporating natural fibers and fly ash. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2025, 24, 100853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Li, K.; Fen-chong, T.; Dangla, P. A study of the behaviors of cement-based materials subject to freezing. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Mechanic Automation and Control Engineering, Wuhan, China, 26–28 June 2010; pp. 1611–1616. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Y.; Fiedler, B.; Yang, W.; Feng, X.; Tang, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, P. Durability of Plant Fiber Composites for Structural Application: A Brief Review. Materials 2023, 16, 3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, X.; Wang, B.; Tao, J.; Shi, K. A Review on Interfacial Bonding Behavior between Fiber and Concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 105, 112455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Ma, Y.; Fu, J.; Hu, J.; Ouyang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, H. Utilization of fibers in ultra-high performance concrete: A review. Compos. Part B Eng. 2022, 241, 109995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özen, S.; Benlioğlu, A.; Mardani, A.; Altın, Y.; Bedeloğlu, A. Effect of graphene oxide-coated jute fiber on mechanical and durability properties of concrete mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 448, 138225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Tabil, L.G.; Panigrahi, S. Chemical Treatments of Natural Fiber for Use in Natural Fiber-Reinforced Composites: A Review. J. Polym. Environ. 2007, 15, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, B.W.; Chakraborty, S.; Kim, H. Efficacy of alkali-treated jute as fibre reinforcement in enhancing the mechanical properties of cement mortar. Mater. Struct. 2016, 49, 1093–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andiç-Çakir, Ö.; Sarikanat, M.; Tüfekçi, H.B.; Demirci, C.; Erdoğan, Ü.H. Physical and mechanical properties of randomly oriented coir fiber–cementitious composites. Compos. Part B Eng. 2014, 61, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poletanovic, B.; Janotka, I.; Janek, M.; Bacuvcik, M.; Merta, I. Influence of the NaOH-treated hemp fibres on the properties of fly-ash based alkali-activated mortars prior and after wet/dry cycles. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 309, 125072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedan, D.; Pagnoux, C.; Chotard, T.; Smith, A.; Lejolly, D.; Gloaguen, V.; Krausz, P. Effect of calcium rich and alkaline solutions on the chemical behaviour of hemp fibres. J. Mater. Sci. 2007, 42, 9336–9342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolêdo Filho, R.D.; Scrivener, K.; England, G.L.; Ghavami, K. Durability of alkali-sensitive sisal and coconut fibres in cement mortar composites. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2000, 22, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsegaye, M.; Nazerian, G.; El Kadi, M.; Aggelis, D.G.; Rahier, H.; Demissie, T.A.; Van Hemelrijck, D.; Tysmans, T. Improving degradation resistance of ensete ventricosum fibre in cement-based composites through fibre surface modification. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2024, 146, 105398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.d.A.; Mobasher, B.; Soranakom, C.; Filho, R.D.T. Effect of fiber shape and morphology on interfacial bond and cracking behaviors of sisal fiber cement based composites. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2011, 33, 814–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, S.P.; Chakraborty, S.; Roy, A.; Adhikari, B.; Majumder, S.B. Chemically modified jute fibre reinforced non-pressure (NP) concrete pipes with improved mechanical properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 37, 841–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Dai, Q.; Si, R. Experimental and numerical investigation of fracture behaviors of steel fiber–reinforced rubber self-compacting concrete. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2022, 34, 04021379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Dai, Q.; Si, R.; Guo, S. Investigation of properties and performances of Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) fiber-reinforced rubber concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 193, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingöl, A.F.; Tohumcu, İ. Effects of different curing regimes on the compressive strength properties of self compacting concrete incorporating fly ash and silica fume. Mater. Des. 2013, 51, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booya, E.; Gorospe, K.; Ghaednia, H.; Das, S. Durability properties of engineered pulp fibre reinforced concretes made with and without supplementary cementitious materials. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 172, 376–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, S.S.; Vivek, S.S. Self-Compacting Concrete Using Supplementary Cementitious Materials and Fibers: Review. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Civ. Eng. 2024, 48, 3899–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmaruzzaman, M. A review on the utilization of fly ash. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2010, 36, 327–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bir Singh, R.; Singh, B. Rheology of High-Volume Fly Ash Self-Compacting Recycled Aggregate Concrete. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2021, 33, 04021280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, R.K.; Siddique, R. Influence of rice husk ash (RHA) on the properties of self-compacting concrete: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 153, 751–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atan, M.D.; Awang, H. The compressive and flexural strengths of self-compacting concrete using raw rice husk ash. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2011, 6, 720–732. [Google Scholar]

- Kannan, V.; Ganesan, K. Effect of Tricalcium Aluminate on Durability Properties of Self-Compacting Concrete Incorporating Rice Husk Ash and Metakaolin. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2016, 28, 04015063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H.T.; Ludwig, H.-M. Effect of rice husk ash and other mineral admixtures on properties of self-compacting high performance concrete. Mater. Des. 2016, 89, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almohammad-albakkar, M.; Behfarnia, K. Water penetration resistance of the self-compacting concrete by the combined addition of micro and nano-silica. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 2021, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Chu, J.; Mo, K.H.; Yap, P.-S. Recent developments in utilization of nano silica in self-compacting concrete: A review. Struct. Concr. 2023, 24, 7524–7548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayeh, B.A.; Hakamy, A.A.; Fattouh, M.S.; Mostafa, S.A. The effect of using nano agriculture wastes on microstructure and electrochemical performance of ultra-high-performance fiber reinforced self-compacting concrete under normal and acceleration conditions. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 18, e01721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oner, A.; Akyuz, S.; Yildiz, R. An experimental study on strength development of concrete containing fly ash and optimum usage of fly ash in concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2005, 35, 1165–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhou, X.; Ma, H.; Hou, D. Advanced Concrete Technology; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Baghabra Al-Amoudi, O.S. Attack on plain and blended cements exposed to aggressive sulfate environments. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2002, 24, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linderoth, O.; Johansson, P.; Wadsö, L. Development of pore structure, moisture sorption and transport properties in fly ash blended cement-based materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 261, 120007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güneyisi, E.; Özturan, T.; Gesogˇlu, M. Effect of initial curing on chloride ingress and corrosion resistance characteristics of concretes made with plain and blended cements. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 2676–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, K.S.; Zhang, M.-H. Water permeability and chloride penetrability of high-strength lightweight aggregate concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2002, 32, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Meyer, C. Utilization of rice husk ash in green natural fiber-reinforced cement composites: Mitigating degradation of sisal fiber. Cem. Concr. Res. 2016, 81, 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Shi, S.Q.; Chen, Z.; Cai, L.; Smith, L. Comparative environmental life cycle assessment of fiber reinforced cement panel between kenaf and glass fibers. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 200, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Calderon, S.; Gordillo-Silva, P.; García-Troncoso, N.; Bompa, D.V.; Flores-Rada, J. Comparative Evaluation of Sisal and Polypropylene Fiber Reinforced Concrete Properties. Fibers 2022, 10, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMAScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Sources | Documents | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Construction and Building Materials | 6 | 476 |

| 2 | Materials Today: Proceedings | 4 | 89 |

| 3 | Journal of Building Engineering | 3 | 69 |

| 4 | International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology | 3 | 18 |

| 5 | AIP Conference Proceedings | 3 | 1 |

| 6 | IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science | 3 | 3 |

| 7 | Case Studies in Construction Materials | 2 | 41 |

| 8 | Journal of Materials Research and Technology | 2 | 27 |

| 9 | Computers and Concrete | 2 | 20 |

| 10 | Asian Journal of Civil Engineering | 2 | 17 |

| No. | Keywords | Occurrences | Total Link Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Self compacting concrete | 34 | 655 |

| 2 | Compressive strength | 26 | 529 |

| 3 | Fibers | 20 | 391 |

| 4 | Tensile strength | 19 | 386 |

| 5 | Self-compacting concrete | 19 | 262 |

| 6 | Reinforced concrete | 12 | 282 |

| 7 | Mechanical properties | 12 | 212 |

| 8 | Natural fibers | 10 | 225 |

| 9 | Fibre-reinforced | 10 | 219 |

| 10 | Bending strength | 10 | 217 |

| 11 | Reinforcement | 9 | 191 |

| 12 | Durability | 9 | 145 |

| 13 | Reinforced plastics | 8 | 183 |

| 14 | Concrete aggregates | 7 | 157 |

| 15 | Mortar | 7 | 139 |

| 16 | Jute fibers | 6 | 147 |

| 17 | Cements | 6 | 145 |

| 18 | Hybrid fiber | 6 | 144 |

| 19 | Property | 6 | 137 |

| 20 | Fly ash | 6 | 120 |

| No. | Author | Documents | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Vivek, S.S. | 5 | 35 |

| 2 | Barluenga, G. | 3 | 44 |

| 3 | Kriker, A. | 3 | 44 |

| 4 | Tioua, T. | 3 | 44 |

| 5 | Kavitha, S. | 3 | 25 |

| 6 | Selvaraj, S.K. | 3 | 21 |

| 7 | Mohamad, N. | 3 | 11 |

| 8 | Murthi, P. | 2 | 63 |

| 9 | Poongodi, K. | 2 | 63 |

| 10 | Venkatesan, G. | 2 | 20 |

| No. | Country | Documents | Citations | Total Link Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | India | 31 | 335 | 12 |

| 2 | Malaysia | 8 | 183 | 7 |

| 3 | Algeria | 8 | 62 | 4 |

| 4 | Canada | 5 | 20 | 7 |

| 5 | China | 4 | 24 | 9 |

| 6 | Indonesia | 4 | 9 | 3 |

| 7 | United States | 3 | 50 | 7 |

| 8 | Spain | 3 | 44 | 3 |

| 9 | Nigeria | 3 | 40 | 1 |

| 10 | Brazil | 3 | 39 | 1 |

| 11 | South Korea | 3 | 27 | 3 |

| 12 | Kuwait | 2 | 64 | 5 |

| 13 | Australia | 2 | 21 | 4 |

| 14 | Chile | 2 | 20 | 3 |

| 15 | Pakistan | 2 | 11 | 2 |

| 16 | Iran | 1 | 275 | 0 |

| 17 | Bangladesh | 1 | 50 | 3 |

| 18 | Mexico | 1 | 42 | 0 |

| 19 | Turkey | 1 | 27 | 0 |

| 20 | Egypt | 1 | 21 | 3 |

| Refs. | Fibres | Classification by Source | Length (mm) | Diameter (µm) | Density (g/cm3) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Modulus of Elasticity (GPa) | Water Absorption (%) | Elongation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [80,81] | Hemp | Bast | 20 | 110 | 1.58 | 600–1100 | - | 158 | - |

| [82] | Jute | - | - | 1.30–1.46 | 393–800 | 10–30 | - | - | |

| [83] | Jute | 12 | - | 1.30 | 390 | 11 | - | - | |

| [84] | Roselle | 35 | 200–300 | 1.35 | 150–400 | 2.76 | - | - | |

| [85] | Bamboo | Culm | 10–30 | 300–400 | 1.52 | 520 | 24 | 10 | - |

| [86] | Bamboo | 6–18 | 224–278 | 1.30 | 335–500 | - | - | 2.5–5.5 | |

| [87] | Coir | Fruit | 20 | - | 0.97 | 215 | 3.50 | 115 | - |

| [88] | Coir | 40 | 500 | 1.14 | - | 20 | - | - | |

| [89] | Luffa | - | 200–750 | 0.90–1.30 | - | 10–20 | - | 8–13 | |

| [90] | Abaca | Leaf | 20–25 | 150–260 | 1.50 | 857 | 41 | - | - |

| [91] | Banana | 30–40 | 150–300 | 1.29–1.32 | 275–350 | 12.00–13.50 | - | - | |

| [75] | Date palm | 12 | 400–500 | 1.58 | 94.73 | 2.05 | 63.58 | 15.22 | |

| [80,92] | Diss | 20 | 900–2480 | 1.32 | 376 | - | 90 | - | |

| [93] | Lechuguilla | 5 | 221 | 1.19 | 68 | - | 97.80 | - |

| Refs. | Fibres | Classification by Source | Cellulose (%) | Hemi-Cellulose (%) | Lignin (%) | Pectin (%) | Pentosan (%) | Moisture Content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [80,81] | Hemp | Bast | 56.10 | 10.90 | 6 | - | - | - |

| [6] | Jute | 68.90 | 11.89 | 14.56 | 0.38 | - | - | |

| [82] | Jute | 60 | 22 | 12 | - | - | - | |

| [84] | Roselle | 65 | 17.60 | 4.50 | 1.10 | 3.90 | 7 | |

| [75] | Date palm | Leaf | 32.00–35.80 | 24.40–28.10 | 26.70–28.70 | - | - | - |

| [80,92] | Diss | 43 | 8 | 35 | - | - | - | |

| [103,104] | Sisal | 65 | 12 | 9.9 |

| Ref. | Fibre | Treatments | Procedure of Treatment | Effects on Fibre Properties |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [116] | Bamboo | Alkaline treatment | The fibres were soaked in a 2% NaOH solution for 24 h. | Alkaline treatment reduced the water absorption of fibres. Treated fibres demonstrated improved surface roughness and were more compatible with the binding matrix due to their enhanced adhesion and surface. |

| [117] | Banana | Alkaline treatment | The fibres were immersed in a 5% NaOH solution for 24 h. The fibres were then washed and soaked in distilled water to remove excess NaOH, and subsequently sun-dried for 24 h. | - |

| [118] | Coir | Alkaline treatment | Coir fibres were treated with a 5% NaOH solution by soaking with occasional stirring. The fibres were then washed with clean water, rinsed, and dried. | - |

| [119] | Kenaf | Alkaline treatment | The fibres were submerged in a 5% NaOH solution. | Alkaline treatment enhanced the mechanical and compatibility properties of fibres with the cement matrix. |

| [80] | Hemp and diss | Alkaline treatment | The fibres were treated with a 5% NaOH solution at 20 °C for 2 h. The fibres were then dried in front of a heater at 40 °C to remove the moisture. Furthermore, the fibres were immersed in a styrene–butadiene rubber solution for 20 min, then dried at 25 °C. | Alkaline treatment removed lignin and waxy substances from the fibre surface. The treatment also reduced the water absorption of fibres and improved fibre–matrix adhesion. |

| [120] | Jute | Alkaline treatment | Jute fibres were soaked in a 1% NaOH solution for 20 min and air-dried at ambient temperature. | - |

| [121] | Red pine needle | Alkaline treatment | The fibres were immersed in a 5% NaOH solution to remove organic substances. | Fibre colours changed to light green for the middle part and black for the edge parts. |

| [7] | Sisal | Alkaline treatment | The fibres were submerged in a 4% NaOH solution. | - |

| [122] | Sisal | Alkaline treatment and coated with a polymer | The fibres were soaked in a 5% NaOH solution for 1 h and then dried. The fibres were consequently soaked in 6% Benzoyl Peroxide in acetone for 30 min and dried again. The fibres were next soaked for 10 min in a polymer solution prepared by diluting carboxylate SBR emulsion with distilled water. The coated fibres were then dried. | - |

| [123] | Coir | Boiling treatment | The fibres were placed in boiling water for 2 h, then washed and sun-dried. | Boiling treatment induced morphological changes in the fibre surface. |

| [124] | Date palm | Boiling treatment | The treatment consisted of boiling date palm fibres, draining the water, and thoroughly washing the fibres to remove organic substances. | - |

| [123] | Coir | Coating with silica fume and metakaolin | Soaked fibres were immersed in an adhesive solution (gum) for 1 min to generate bonding. Silica fume and metakaolin were mixed in equal ratios around the fibres and allowed to dry. | Coating treatment induced morphological changes in the fibre surface. |

| [125] | Caryota-urens | Silane treatment | The silane solution was prepared by diluting a vinyl tri-ethoxy silane chemical with an ethanol and water mixture (80:20). The fibres were soaked in the silane solution for 15 min and then dried at room temperature. The dried fibres were washed in ethanol three to four times and oven-dried at 105 °C for 12 h to remove excess chemicals. | The treatment reduced hemicellulose and lignin content in fibres. |

| [123] | Coir | Soaking in water | The fibres were soaked in water for 30 min, washed, and then the process was repeated three times, followed by sun-drying. | Soaking in water induced morphological changes in the fibre surface. |

| [120] | Jute | Ultrasonic vibration coating | The treatment was conducted using an intelligent ultrasonic processor. A nano-sized silica sand was adopted as a wrapping agent to form a fibre coating with a 0.9% mass ratio of the jute fibre. | - |

| Ref. | Type of Plant Fibres | Treatment Method | Fibre Length (mm) | Fibre Dosage (kg/m3) | Rheological Properties of SCC Mixes | Variations in the Rheological Properties of PFRSCC Compared to the Unreinforced Mix (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slump Flow Diameter (mm) | V- Funnel Time (s) | L-Box Ratio | J-Ring Height (mm) | Segregated Portion (%) | Slump Flow Diameter | V- Funnel Time | L-Box Ratio | J-Ring Height | Segregated Portion | |||||

| [147] | Alfa | Untreated | - | 0 | 730 | 10.73 | 0.91 | 1.50 | 15.40 | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| 2.0 | 680 | 11.98 | 0.84 | 17.00 | 5.40 | −6.8% | 11.6% | −7.7% | 1033.3% | −64.9% | ||||

| [117] | Banana | Untreated | - | 0 | 565 | - | - | - | - | 0% | - | - | - | - |

| 0.6 | 523 | −7.4% | ||||||||||||

| 1.6 | 325 | −42.5% | ||||||||||||

| 2.6 | 307 | −45.7% | ||||||||||||

| Alkaline treatment | - | 0 | 565 | - | - | - | - | 0% | - | - | - | - | ||

| 0.6 | 375 | −33.6% | ||||||||||||

| 1.6 | 317 | −43.9% | ||||||||||||

| 2.6 | 310 | −45.1% | ||||||||||||

| [60] | Banana | Untreated | - | 0 | 785 | - | - | - | - | 0% | - | - | - | - |

| 1.0 | 760 | −3.2% | ||||||||||||

| 2.0 | 746 | −5.0% | ||||||||||||

| 3.0 | 725 | −7.6% | ||||||||||||

| 4.0 | 711 | −9.4% | ||||||||||||

| 5.0 | 697 | −11.2% | ||||||||||||

| 6.0 | 649 | −17.3% | ||||||||||||

| [125] | Caryota-urens | Silane treatment | - | 0 | 680 | 6.00 | 1.00 | 1.50 | - | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | - |

| 6.3 | 670 | 7.00 | 0.97 | 2.00 | −1.5% | 16.7% | −3.0% | 33.3% | ||||||

| 12.6 | 662 | 8.00 | 0.95 | 4.00 | −2.6% | 33.3% | −5.0% | 166.7% | ||||||

| 18.9 | 655 | 10.00 | 0.93 | 6.00 | −3.7% | 66.7% | −7.0% | 300.0% | ||||||

| 25.2 | 650 | 12.00 | 0.90 | 8.00 | −4.4% | 100.0% | −10.0% | 433.3% | ||||||

| 31.5 | 640 | 14.00 | 0.85 | 10.00 | −5.9% | 133.3% | −15.0% | 566.7% | ||||||

| [148] | Coir | Untreated | - | 0 | 690 | - | 0.86 | - | - | 0% | - | 0% | - | - |

| 0.9 | 670 | 0.84 | −2.9% | −2.3% | ||||||||||

| 1.8 | 630 | 0.82 | −8.7% | −4.7% | ||||||||||

| 2.7 | 600 | 0.81 | −13.0% | −5.8% | ||||||||||

| [88] | Coir | Untreated | 40 mm | 0 | 720 | 6.00 | - | - | - | 0% | 0% | - | - | - |

| 2.8 | 690 | 8.00 | −4.2% | 33.3% | ||||||||||

| 5.6 | 660 | 8.50 | −8.3% | 41.7% | ||||||||||

| 8.4 | 645 | 9.00 | −10.4% | 50.0% | ||||||||||

| 11.2 | 630 | 10.00 | −12.5% | 66.7% | ||||||||||

| [118] | Coir | Alkaline treatment | - | 0 | 760 | 6.90 | 0.98 | - | - | 0% | 0% | 0% | - | - |

| 1.2 | 690 | 9.00 | 0.91 | −9.2% | 30.4% | −7.2% | ||||||||

| 1.8 | 650 | 12.80 | 0.88 | −14.5% | 85.5% | −10.3% | ||||||||

| 2.4 | 605 | 13.80 | 0.85 | −20.4% | 100.0% | −13.3% | ||||||||

| [87] | Coir | Untreated | 20 mm | 0 | 725 | 6.15 | 0.92 | - | - | 0% | 0% | 0% | - | - |

| 4.3 | 720 | 6.80 | 0.89 | −0.7% | 10.6% | −3.3% | ||||||||

| 8.7 | 720 | 7.00 | 0.88 | −0.7% | 13.8% | −4.3% | ||||||||

| 13.2 | 715 | 8.65 | 0.88 | −1.4% | 40.7% | −4.3% | ||||||||

| 17.8 | 680 | 9.72 | 0.82 | −6.2% | 58.0% | −10.9% | ||||||||

| 22.6 | 640 | 12.5 | 0.75 | −11.7% | 103.3% | −18.5% | ||||||||

| [123] | Coir | Soaking in water | 25 mm | 0 | 625 | - | - | - | - | 0% | - | - | - | - |

| 2.5 | 615 | −1.6% | ||||||||||||

| 5.0 | 595 | −4.8% | ||||||||||||

| Boiling treatment | 0 | 625 | - | - | - | - | 0% | - | - | - | - | |||

| 2.5 | 610 | −2.4% | ||||||||||||

| 5.0 | 590 | −5.6% | ||||||||||||

| Coating with silica fume and metakaolin | 0 | 625 | - | - | - | - | 0% | - | - | - | - | |||

| 2.5 | 615 | −1.6% | ||||||||||||

| 5.0 | 585 | −6.4% | ||||||||||||

| [75] | Date palm | Untreated | - | 0 | 750 | - | 1.00 | - | 15.80 | 0% | - | 0% | - | 0% |

| 0.6 | 655 | 0.83 | 8.40 | −12.7% | −17.5% | −46.8% | ||||||||

| 0.9 | 620 | 0.82 | 7.60 | −17.3% | −18.0% | −51.9% | ||||||||

| 1.2 | 600 | 0.80 | 6.80 | −20.0% | −20.0% | −57.0% | ||||||||

| [124] | Date palm | Boiling treatment | 10 mm | 0 | 790 | - | - | - | - | 0% | - | - | - | - |

| 1.1 | 740 | −6.3% | ||||||||||||

| 2.1 | 700 | −11.4% | ||||||||||||

| 20 mm | 0 | 790 | - | - | - | - | 0% | - | - | - | - | |||

| 1.1 | 670 | −15.2% | ||||||||||||

| 2.1 | 655 | −17.1% | ||||||||||||

| [149] | Date palm | Untreated | 10 mm | 0 | 700 | 10.20 | 0.97 | - | - | 0% | 0% | 0% | - | - |

| 0.5 | 680 | 11.40 | 0.94 | −2.9% | 11.8% | −3.1% | ||||||||

| 1.1 | 680 | 11.90 | 0.92 | −2.9% | 16.7% | −5.2% | ||||||||

| 2.1 | 670 | 12.30 | 0.89 | −4.3% | 20.6% | −8.2% | ||||||||

| 20 mm | 0 | 700 | 10.20 | 0.97 | - | - | 0% | 0% | 0% | - | - | |||

| 0.5 | 690 | 10.90 | 0.95 | −1.4% | 6.9% | −2.1% | ||||||||

| 1.1 | 680 | 12.30 | 0.92 | −2.9% | 20.6% | −5.2% | ||||||||

| 2.1 | 680 | 13.70 | 0.87 | −2.9% | 34.3% | −10.3% | ||||||||

| 30 mm | 0 | 700 | 10.20 | 0.97 | - | - | 0% | 0% | 0% | - | - | |||

| 0.5 | 700 | 11.20 | 0.95 | 0% | 9.8% | −2.1% | ||||||||

| 1.1 | 690 | 13.40 | 0.89 | −1.4% | 31.4% | −8.3% | ||||||||

| 2.1 | 670 | 15.90 | 0.83 | −4.3% | 55.9% | −14.4% | ||||||||

| [147] | Date palm | Untreated | - | 0 | 730 | 10.73 | 0.91 | 1.50 | 15.40 | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| 2.0 | 690 | 13.89 | 0.83 | 16.1 | 6.13 | −5.5% | 29.5% | −8.8% | 973.3% | −60.2% | ||||

| [147] | Diss | Untreated | - | 0 | 730 | 10.73 | 0.91 | 1.50 | 15.40 | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| 2.0 | 715 | 16.30 | 0.75 | 14.3 | 7.87 | −2.1% | 51.9% | −17.6% | 853.3% | −48.9% | ||||

| [80] | Diss | Alkaline treatment | 20 mm | 0 | 730 | - | - | - | - | 0% | - | - | - | - |

| 2.0 | 670 | −8.2% | ||||||||||||

| Polymer-coated | 0 | 730 | - | - | - | - | 0% | - | - | - | - | |||

| 2.0 | 690 | −5.5% | ||||||||||||

| [80] | Hemp | Alkaline treatment | 20 mm | 0 | 730 | - | - | - | - | 0% | - | - | - | - |

| 2.0 | 600 | −17.8% | ||||||||||||

| Polymer-coated | 0 | 730 | - | - | - | - | 0% | - | - | - | - | |||

| 2.0 | 620 | −15.1% | ||||||||||||

| [6] | Jute | Untreated | 20 mm | 0 | 671 | 5.50 | 0.95 | 6.25 | 9.50 | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| 1.5 | 648 | 8.00 | 0.88 | 7.50 | 8.70 | −3.4% | 45.5% | −7.4% | 20.0% | −8.4% | ||||

| 3.7 | 632 | 10.00 | 0.82 | 9.00 | 8.50 | −5.8% | 81.8% | −13.7% | 44.0% | −10.5% | ||||

| 7.3 | 620 | 11.00 | 0.75 | 11.75 | 8.20 | −7.6% | 100.0% | −21.1% | 88.0% | −13.7% | ||||

| 11.0 | 575 | 11.8 | 0.71 | 13.00 | 7.90 | −14.3% | 114.5% | −25.3% | 108.0% | −16.8% | ||||

| 14.6 | 550 | 13.5 | 0.70 | 15.25 | 6.50 | −18.0% | 145.5% | −26.3% | 144.0% | −31.6% | ||||

| [150] | Jute | Untreated | 9 mm | 0 | 620 | - | - | - | - | 0% | - | - | - | - |

| 2.6 | 380 | −38.7% | ||||||||||||

| 5.2 | 200 | −67.7% | ||||||||||||

| 10.3 | 60 | −90.3% | ||||||||||||

| [93] | Lechuguilla | Untreated | 5 mm | 0 | 610 | - | - | 56.00 | - | 0% | - | - | 0% | - |

| 11.9 | 600 | 50.00 | −1.6% | −10.7% | ||||||||||

| [121] | Red pine needle | Alkaline treatment | 30 mm | 0 | 735 | 12.10 | - | - | - | 0% | 0% | - | - | - |

| 5.9 | 715 | 13.40 | −2.7% | 10.7% | ||||||||||

| 11.8 | 725 | 14.40 | −1.4% | 19.0% | ||||||||||

| 17.7 | 685 | 16.70 | −6.8% | 38.0% | ||||||||||

| 23.6 | 665 | 20.00 | −9.5% | 65.3% | ||||||||||

| 40 mm | 0 | 735 | 12.10 | - | - | - | 0% | 0% | - | - | - | |||

| 7.4 | 650 | 14.30 | −11.6% | 18.2% | ||||||||||

| 14.8 | 670 | 16.60 | −8.8% | 37.2% | ||||||||||

| 22.2 | 640 | 18.70 | −12.9% | 54.5% | ||||||||||

| 29.6 | 615 | 20.60 | −16.3% | 70.2% | ||||||||||

| 50 mm | 0 | 735 | 12.10 | - | - | - | 0% | 0% | - | - | - | |||

| 9.8 | 605 | 15.80 | −17.7% | 30.6% | ||||||||||

| 19.6 | 615 | 17.20 | −16.3% | 42.1% | ||||||||||

| 29.4 | 575 | 18.50 | −21.8% | 52.9% | ||||||||||

| 39.2 | 550 | 22.30 | −25.2% | 84.3% | ||||||||||

| [84] | Roselle | Untreated | 35 mm | 0 | 682 | 7.00 | 1.00 | 6.00 | - | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | - |

| 5.8 | 677 | 9.00 | 0.98 | 6.50 | −0.7% | 28.6% | −2.0% | 8.3% | ||||||

| 11.7 | 655 | 10.00 | 0.95 | 7.50 | −4.0% | 42.9% | −5.0% | 25.0% | ||||||

| 17.5 | 650 | 11.00 | 0.93 | 9.00 | −4.7% | 57.1% | −7.0% | 50.0% | ||||||

| 23.3 | 638 | 13.00 | 0.87 | 11.50 | −6.5% | 85.7% | −13.0% | 91.7% | ||||||

| [151] | Sisal | Untreated | 50 mm | 0 | 685 | 8.00 | 1.00 | 8.00 | - | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | - |

| 0.5 | 665 | 8.00 | 0.98 | 7.00 | −2.9% | 0.0% | −2.0% | −12.5% | ||||||

| 1.0 | 655 | 8.00 | 0.97 | 8.00 | −4.4% | 0.0% | −3.0% | 0.0% | ||||||

| 1.5 | 653 | 8.00 | 0.95 | 8.00 | −4.7% | 0.0% | −5.0% | 0.0% | ||||||

| 2.0 | 650 | 9.00 | 0.93 | 9.00 | −5.1% | 12.5% | −7.0% | 12.5% | ||||||

| [7] | Sisal | Alkaline treatment | 25 mm | 0 | 750 | 8.03 | 1.00 | - | - | 0% | 0% | 0% | - | - |

| 1.2 | 740 | 9.51 | 0.95 | −1.3% | 18.4% | −5.0% | ||||||||

| 2.4 | 700 | 10.18 | 0.82 | −6.7% | 26.8% | −18.0% | ||||||||

| 3.6 | 645 | 11.41 | 0.75 | −14.0% | 42.1% | −25.0% | ||||||||

| [122] | Sisal | Untreated | 20 mm | 0 | 780 | 7.50 | 0.94 | - | - | 0% | 0% | 0% | - | |

| 1.9 | 755 | 8.50 | 0.89 | −3.2% | 13.3% | −5.3% | ||||||||

| 3.8 | 720 | 11.00 | 0.85 | −7.7% | 46.7% | −9.6% | - | |||||||

| 5.7 | 690 | 12.00 | 0.81 | −11.5% | 60.0% | −13.8% | ||||||||

| 7.6 | 655 | 15.00 | 0.79 | −16.0% | 100.0% | −16.0% | ||||||||