Effect of Sedimentary Environment on Mudrock Lithofacies and Organic Matter Enrichment in a Freshwater Lacustrine Basin: Insight from the Triassic Chang 7 Member in the Ordos Basin, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Geological Settings

2.1. Tectonic Setting and Sedimentary Characteristics

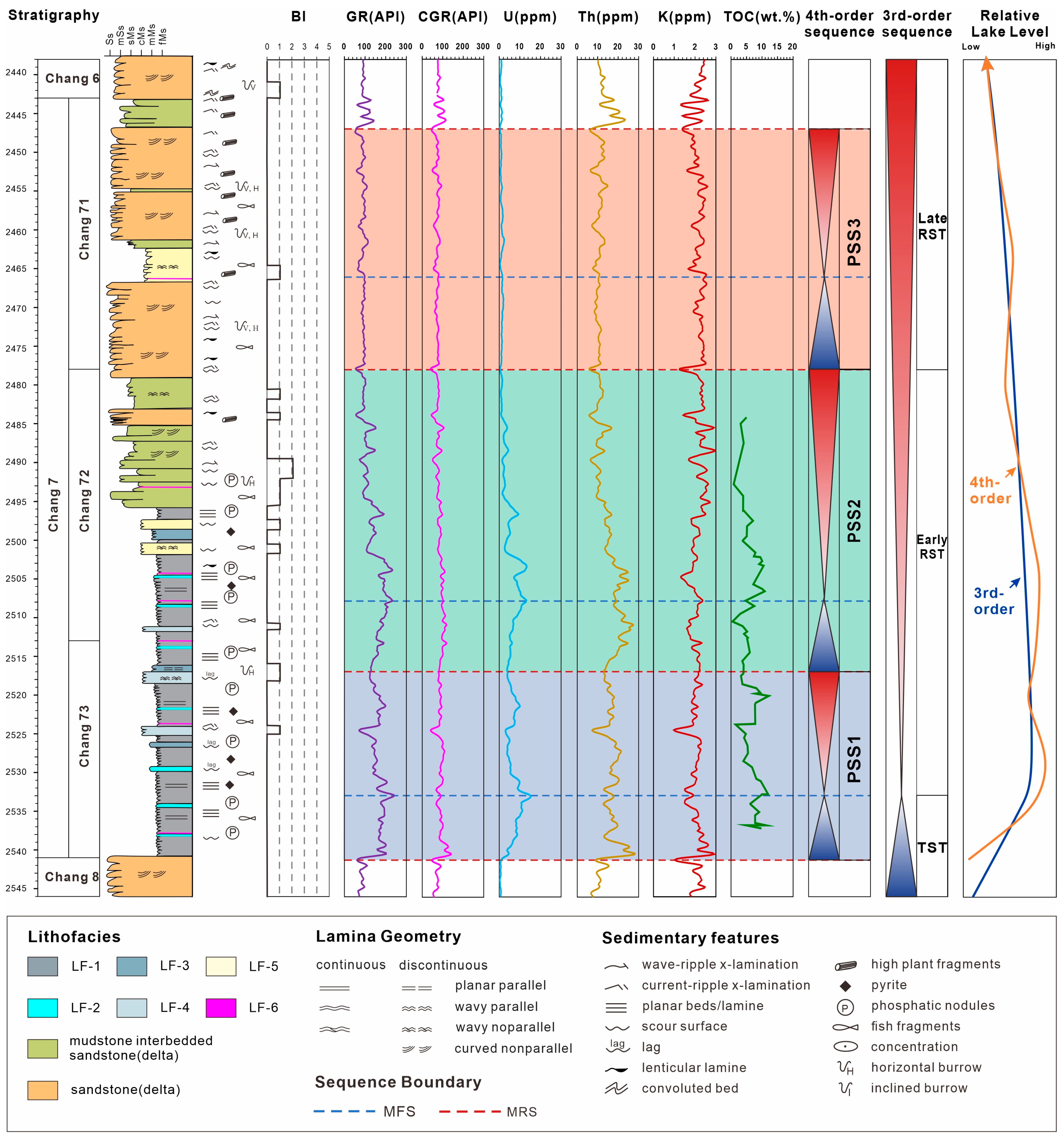

2.2. High-Resolution Sequence-Stratigraphic Framework

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Thin Sections and Electron Microscopy

3.2. Total Organic Carbon and Rock-Eval Pyrolysis Analysis

3.3. Elements Analysis

3.4. Sequence-Stratigraphic Division

4. Results

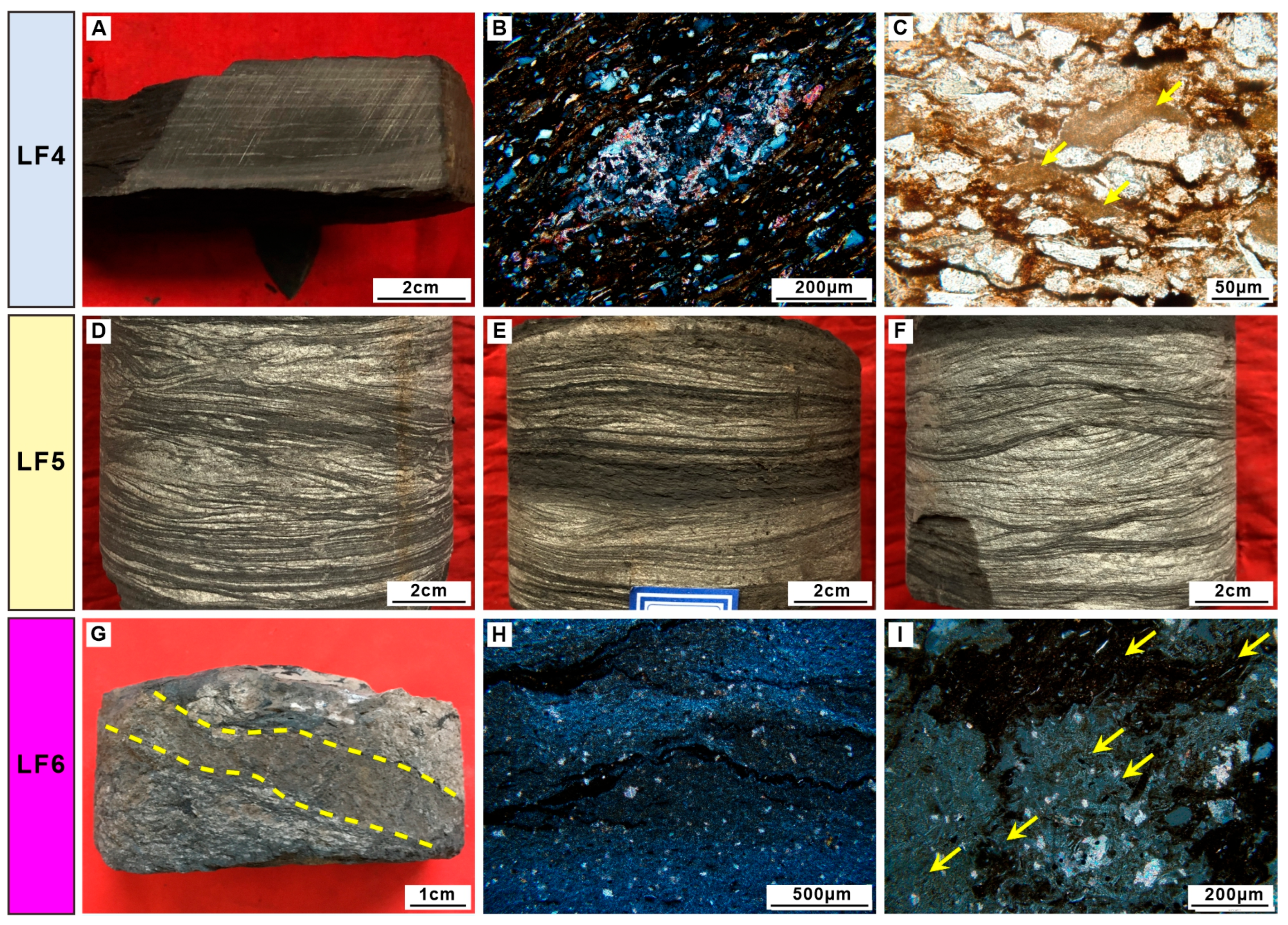

4.1. Description and Interpretation of Lithofacies

4.1.1. Organic-Rich Parallel-Laminated Fine Mudstone

Description

Interpretation

4.1.2. Phosphatic Fine Mudstone

Description

Interpretation

4.1.3. Massive to Faintly Laminated Medium–Fine Mudstone

Description

Interpretation

4.1.4. Current Ripple Coarse to Medium Mudstone

Description

Interpretation

4.1.5. Wavy Ripple Coarse Mudstone Interbedded Fine Mudstone

Description

Interpretation

4.1.6. Massive to Layered Muddy Tuff/Tuff

Description

Interpretation

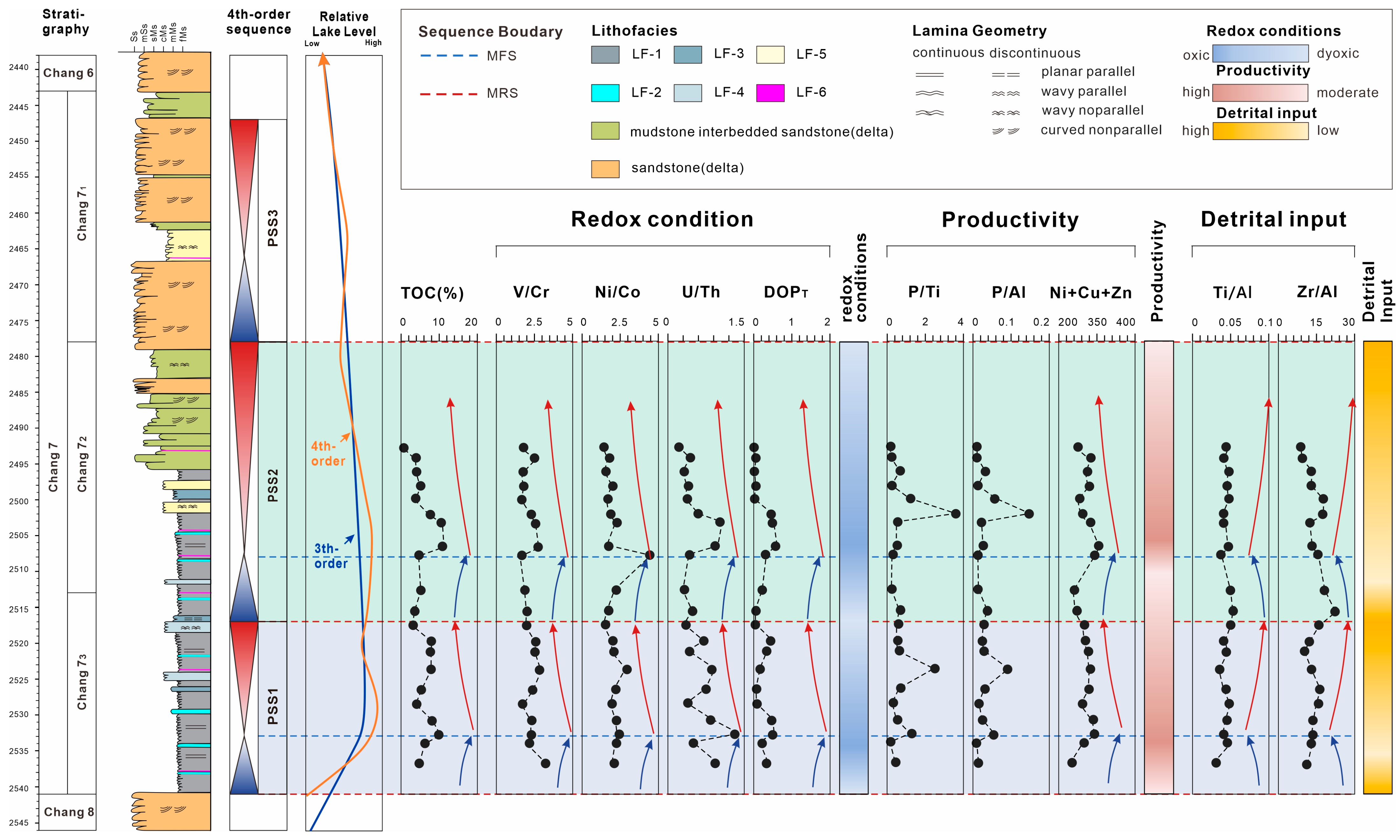

4.2. Sequence Stratigraphy

4.3. TOC and Rock-Eval Pyrolysis

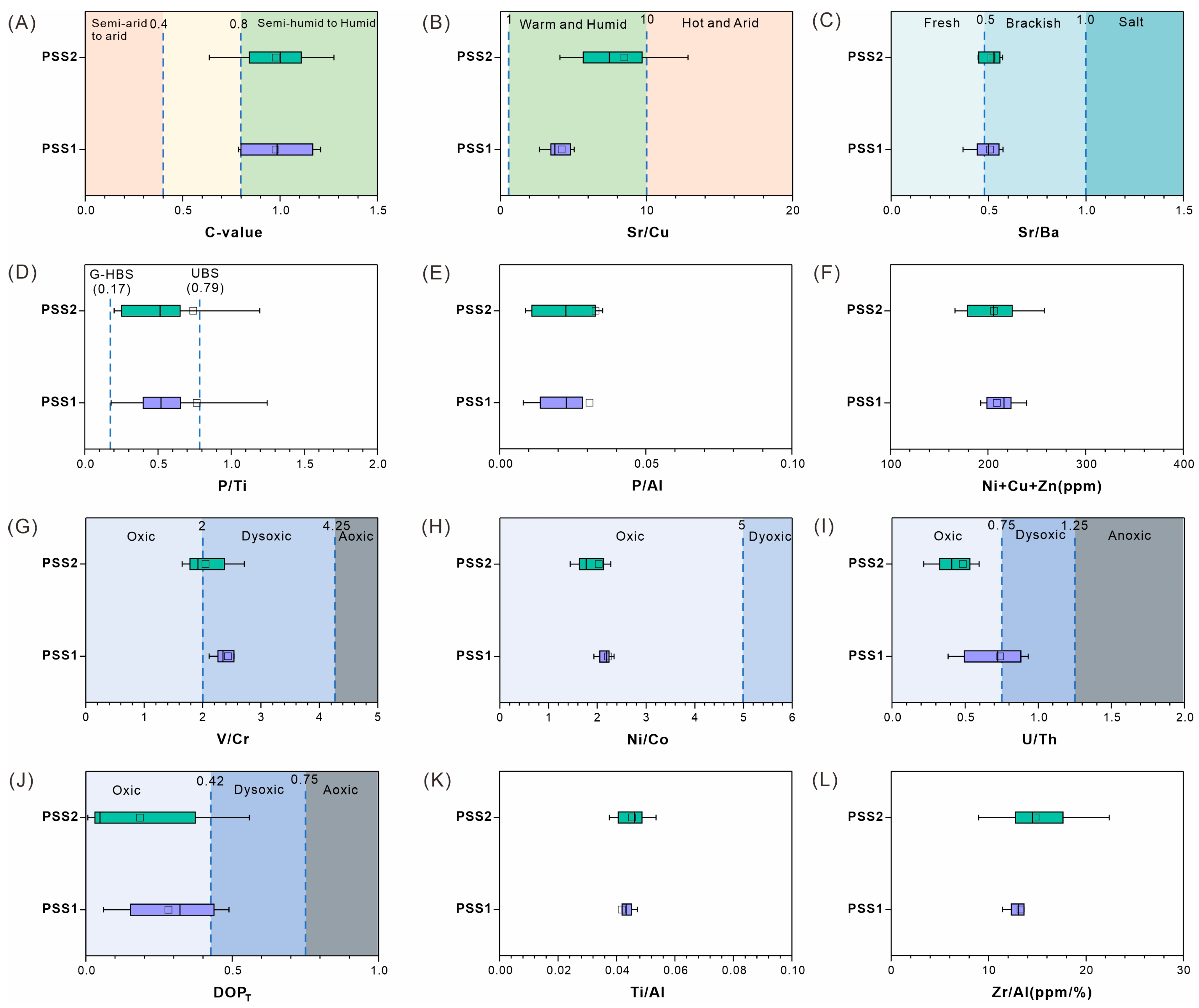

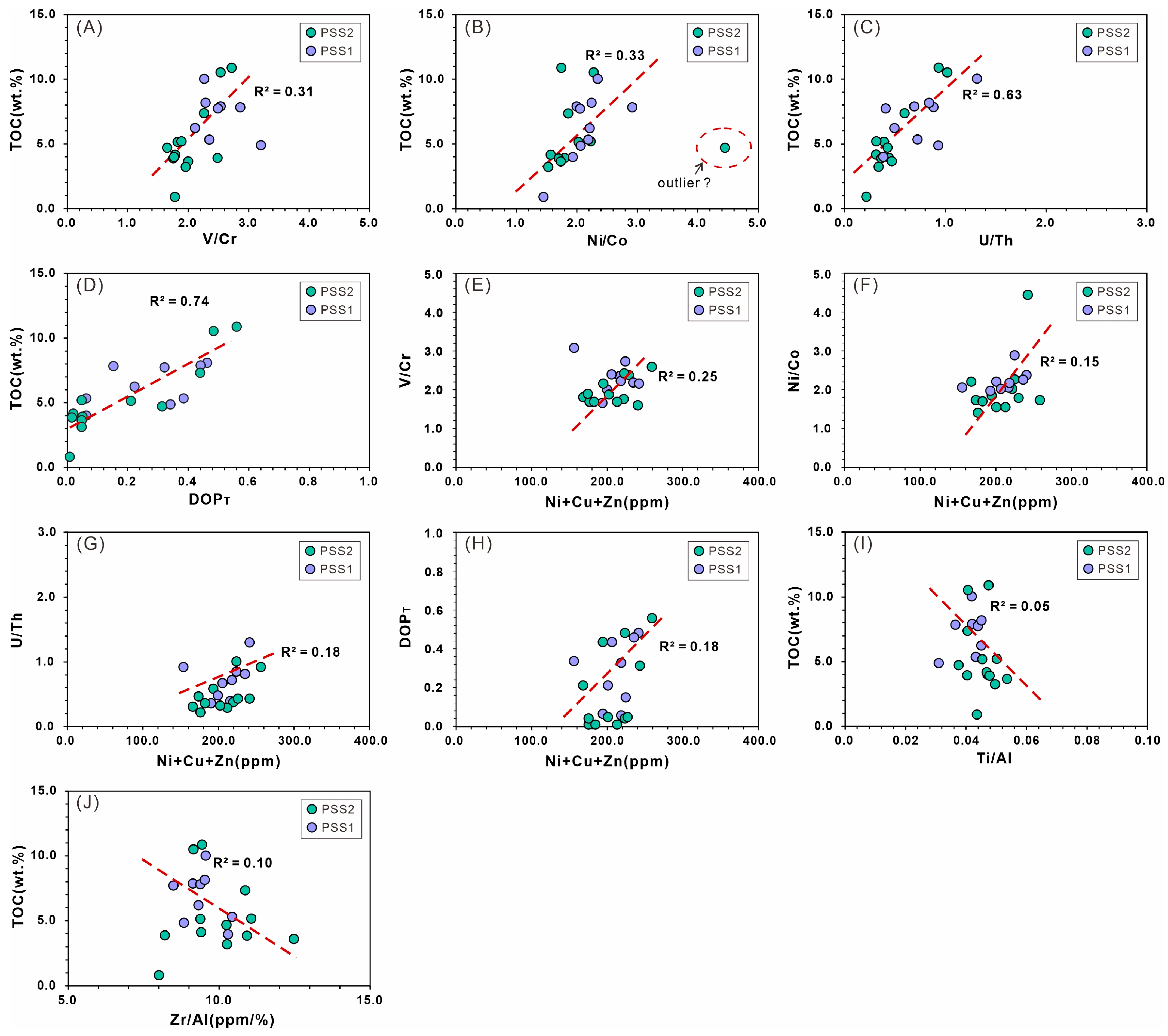

4.4. Paleoenvironmental Proxies

5. Discussion

5.1. Reconstruction of Paleoenvironment

5.1.1. Paleoclimate

5.1.2. Salinity

5.1.3. Paleoproductivity

5.1.4. Redox Condition

5.1.5. Detrital Input

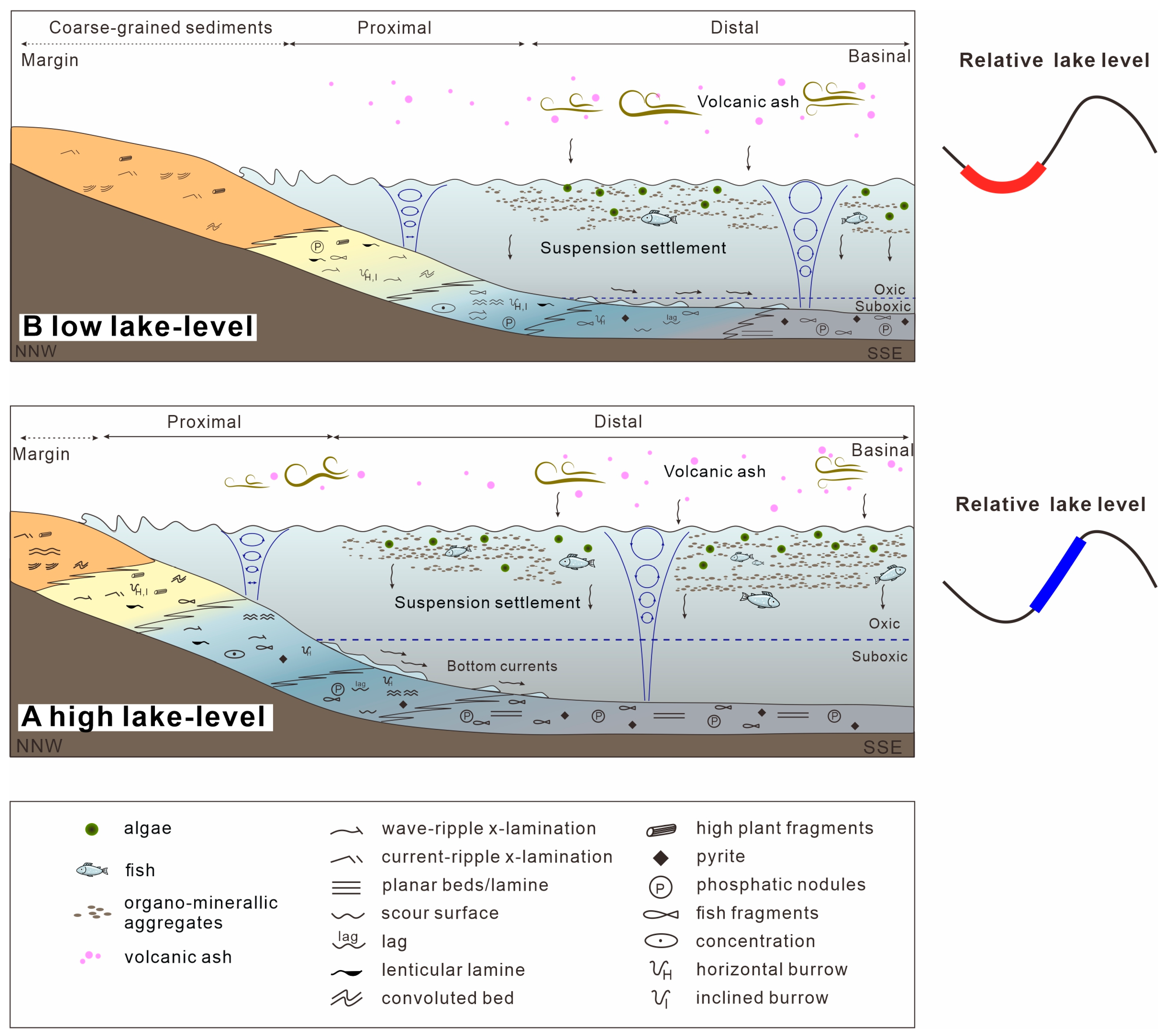

5.2. The Effect of Sedimentary Environment on Lithofacies

5.2.1. Fourth-Order Sequence PSS1

5.2.2. Fourth-Order Sequence PSS2

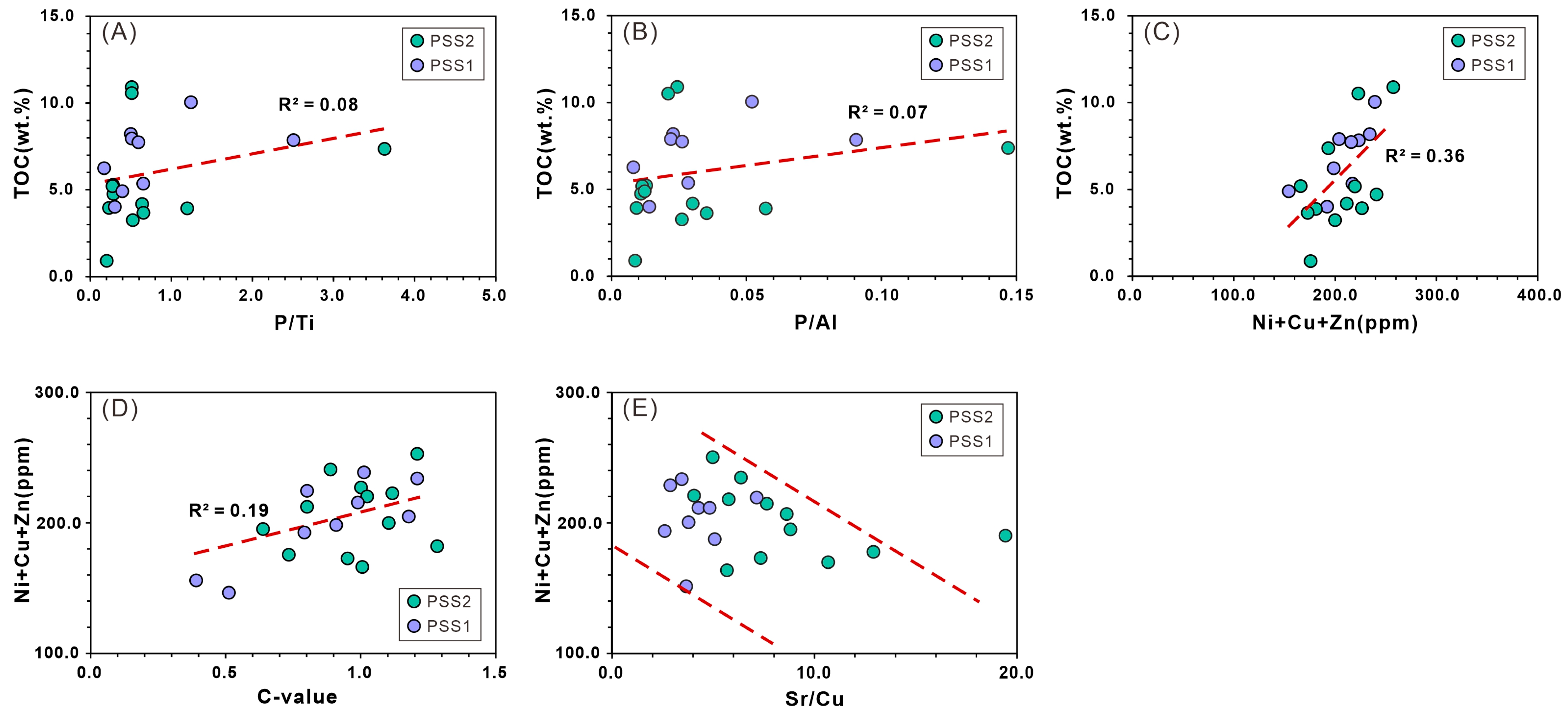

5.3. The Effect of Sedimentary Environment on Organic Matter Enrichment

5.3.1. Production

5.3.2. Destruction

5.3.3. Dilution

5.3.4. Influence of Lake Level Fluctuation on Organic Matter

5.4. A Depositional Model for a Freshwater Lacustrine Basin

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report. In Fourth Assessment; International National Panel on Climate Change: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007; p. 104. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. In Fifth Assessment; International Panel on Climate Change: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; p. 151. [Google Scholar]

- Friedemann, A.J. Life After Fossil Fuels: A Reality Check on Alternative Energy; Springer International Publishing: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Holechek, J.L.; Geli, H.M.E.; Sawalhah, M.N.; Valdez, R. A Global Assessment: Can Renewable Energy Replace Fossil Fuels by 2050? Sustainability 2022, 14, 4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.H.; Jones, R.A.; Haley, B.; Kwok, G.; Hargreaves, J.; Farbes, J.; Torn, M.S. Carbon-neutral pathways for the United States. AGU Adv. 2021, 2, e2020AV000284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.W.; Ma, X.X.; Jiang, Q.G.; Li, Z.M.; Pang, X.Q.; Zhang, C.T. Enlightenment from formation conditions and enrichment characteristics of marine shale oil in North America. Pet. Geol. Recovery Effic. 2019, 26, 13, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Z.J.; Bai, Z.R.; Gao, B.; Li, M.W. Has China ushered in the shale oil and gas revolution? Oil Gas Geol. 2019, 40, 451–458, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Bai, G.P.; Qiu, H.H.; Deng, Z.Z.; Wang, W.Y.; Chen, J. Distribution and main controls for shale oil resources in USA. Pet. Geol. Exp. 2020, 42, 524–532, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.S.; Cai, X.Y.; Zhao, P.R.; Hu, Z.Q.; Liu, H.M.; Gao, B.; Wang, W.Q.; Li, Z.M.; Zhang, Z.L. Geological characteristics and exploration practices of continental shale oil in China. Acta Geol. Sin. 2022, 96, 155–171, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.Z.; Zhu, R.K.; Liu, W.; Bian, C.S.; Wang, K. Enrichment conditions and distribution characteristics of lacustrine medium-to-high maturity shale oil in China. Earth Sci. Front. 2023, 30, 116–127, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Loucks, R.G.; Ruppel, S.C. Mississippian Barnett Shale: Lithofacies and depositional setting of a deep-water shale-gas succession in the Fort Worth Basin, Texas. AAPG Bull. 2007, 914, 579–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnahwi, A.; Loucks, R.G.; Ruppel, S.C.; Scott, R.W.; Tribovillard, N. Dip-related changes in stratigraphic architecture and associated sedimentological and geochemical variability in the Upper Cretaceous Eagle Ford Group in south Texas. AAPG Bull. 2018, 102, 2537–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnahwi, A.; Loucks, R.G. Mineralogical composition and total organic carbon quantification using X-ray fluorescence data from the Upper Cretaceous Eagle Ford Group in southern Texas. AAPG Bull. 2019, 103, 2891–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Jiang, S.; Lu, Y.; Xu, S.; Shu, Y.; Wang, Y. Productivity or preservation? The factors controlling the organic matter accumulation in the late Katian through Hirnantian Wufeng organic-rich shale, South China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2019, 109, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.L.; Qiu, Z.; Zou, C.N.; Fu, J.H.; Zhang, W.Z.; Tao, H.F.; Li, S.X.; Zhou, S.W.; Wang, L.; Chen, Z.Q. Environmental changes in the Middle Triassic lacustrine basin (Ordos, North China): Implication for biotic recovery of freshwater ecosystem following the Permian-Triassic mass extinction. Glob. Planet. Change 2021, 204, 103559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Liu, R.; Liu, Z. Sedimentary sequence evolution and organic matter accumulation characteristics of the Chang 8–Chang 7 members in the Upper Triassic Yanchang Formation, southwest Ordos Basin, central China. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 196, 107751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Dong, H.; Huang, X.W.; Liang, Y.F.; Deng, Z.Y.; Huang, L.; Jiang, S. The paleo-oceanic environment and organic matter enrichment mechanism of the early Cambrian in the southern Lower Yangtze platform, Chinas. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2024, 170, 107119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.Q.; Jiang, F.J.; Xu, Y.L.; Guo, J.; Xu, T.W.; Hu, T.; Shen, W.B.; Zheng, X.W.; Chen, D.; Jiang, Q.; et al. Middle Eocene Climatic Optimum drove palaeoenvironmental fluctuations and organic matter enrichment in lacustrine facies of the Bohai Bay Basin, China. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclim. Palaeoecol. 2025, 659, 112665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, A.; Wagreich, M.; Gentzis, T.; Ocubalidet, S.; Tahoun, S.S.; Elewa, A.M. Depositional and organic carbon-controlled regimes during the Coniacian-Santonian event: First results from the southern Tethys (Egypt). Mar. Pet. Geol. 2020, 115, 104285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, A.; Wagreich, M. Earth system changes during the cooling greenhouse phase of the Late Cretaceous: Coniacian-Santonian OAE3 subevents and fundamental variations in organic carbon deposition. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2022, 229, 104022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Jiang, Z.; Cao, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y.; Hao, F. Sedimentary characteristics and origin of lacustrine organic-rich shales in the salinized Eocene Dongying Depression. GSA Bull. 2018, 130, 154–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Wu, J.; Jiang, Z.X.; Cao, Y.C.; Song, G.Q. Sedimentary environmental controls on petrology and organic matter accumulation in the upper fourth member of the Shahejie Formation (Paleogene, Dongying depression, Bohai Bay Basin, China). Int. J. Coal Geol. 2018, 186, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xiao, D.; Lu, S.; Jiang, S.; Lu, S. Effect of sedimentary environment on the formation of organic-rich marine shale: Insights from major/trace elements and shale composition. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2019, 204, 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.L.; Huang, S.P.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, X.H.; Liu, Z.X.; Wen, Y.R.; Zhang, Y.L.; Sun, M.D. Palaeoenvironment evolution and organic matter enrichment mechanisms of the Wufeng-Longmaxi shales of Yuanán block in western Hubei, middle Yangtze: Implications for shale gas accumulation potential. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2023, 152, 106242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.M.; Cao, J.; Xia, L.W.; Bian, L.L.; Liu, J.C.; Zhang, R.J. Links between marine incursions, lacustrine anoxia and organic matter enrichment in the Upper Cretaceous Qingshankou Formation, Songliao Basin, China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2023, 158, 106536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Shen, J.; Yang, F.; Hu, Q.; Yu, Y.; Xiong, L.; Zhang, T.; Deng, H.C.; He, J. Provenance, sedimentary paleoenvironment and organic matter accumulation mechanisms in shales from the Lower Cambrian Qiongzhusi Formation, SW Yangtze Block, China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2025, 181, 107520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohacs, K.M.; Lazar, O.; Demko, T.M. Parasequence types in shelfal mudstone strata—Quantitative observations of lithofacies and stacking patterns, and conceptual link to modern depositional regimes. Geology 2014, 42, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, O.R.; Bohacs, K.M.; Macquaker, J.H.S.; Schieber, J.; Demko, T.M. Capturing key attributes of fine-grained sedimentary rocks in outcrops, cores, and thin sections: Nomenclature and description guidelines. J. Sediment. Res. 2015, 85, 230–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieber, J. Mud re-distribution in epicontinental basins-Exploring likely processes. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2016, 71, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W.M.; Hao, F.; Song, Y.; Tian, J.; Meng, M.M.; Huang, H.X. Organic geochemical and mineralogical characterization of the lower Silurian Longmaxi shale in the southeastern Chongqing area of China: Implications for organic matter accumulation. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2020, 220, 103412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sageman, B.B.; Murphy, A.E.; Werne, J.P.; Ver Straeten, C.A.; Hollander, D.J.; Lyons, T.W. A tale of shales: The relative roles of production, decomposition, and dilution in the accumulation of organic-rich strata, Middle-Upper Devonian, Appalachian basin. Chem. Geol. 2003, 195, 229–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumsack, H. The trace metal content of recent organic carbon-rich sediments; implications for Cretaceous black shale formation. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclim. Palaeoecol. 2006, 232, 344–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.Z.; Zhu, X.M.; Jiang, Z.X.; Zhu, D.Y.; Ye, L.; Chen, Z.Y. Main controlling factors of organic matter enrichment in continental freshwater lacustrine shale: A case study of the Jurassic Ziliujing Formation in northeastern Sichuan Basin. J. Paleogeography 2023, 25, 806–822, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, S.; Wang, J.; Fu, X.; Chen, W.; Feng, X.; Wang, D.; Song, C.; Wang, Z. Geochemical characteristics, redox conditions, and organic matter accumulation of marine oil shale from the Changliang Mountain area, northern Tibet, China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2015, 64, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doner, Z.; Kumral, M.; Demirel, I.H.; Hu, Q. Geochemical characteristics of the Silurian shales from the central Taurides, southern Turkey: Organic matter accumulation, preservation and depositional environment modeling. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2019, 102, 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohacs, K.M.; Grabowski, G.J.; Carroll, A.R.; Mankiewicz, P.J.; Miskell-Gerhardt, K.; Schwalbach, J.R.; Wegner, M.B.; Simo, J.A. Production, destruction, and dilution—The many paths to source-rock development. In The Deposition of Organic-Carbon-Rich Sediments: Models, Mechanisms, and Consequences; Harris, N.B., Ed.; SEPM Special Publication: Tulsa, OK, USA, 2005; Volume 82, pp. 61–101. [Google Scholar]

- Passey, Q.R.; Bohacs, K.M.; Esch, W.L.; Klimentidis, R.E.; Sinha, S. From Oil-Prone Source Rock to Gas-Producing Shale Reservoir-Geologic and Petrophysical Characterization of Unconventional Shale Gas Reservoirs. In Proceedings of the International Oil and Gas Conference and Exhibition in China, Beijing, China, 8–10 June 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, L. Control actions of sedimentary environments and sedimentation rates on lacustrine oil shale distribution, an example of the oil shale in the Upper Triassic Yanchang Formation, southeastern Ordos Basin (NW China). Mar. Pet. Geol. 2019, 102, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wu, S.H.; Xia, D.L.; You, X.L.; Zhang, H.M.; Lu, H. Major and trace element geochemistry of the lacustrine organic-rich shales from the Upper Triassic Chang 7 Member in the southwestern Ordos Basin, China: Implications for paleoenvironment and organic matter accumulation. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2019, 111, 852–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Liu, R.; Liu, Z.J.; Li, B.L.; Han, J.B.; Zhao, K.G. Influence of volcanic and hydrothermal activity on organic matter enrichment in the Upper Triassic Yanchang Formation, southern Ordos Basin, Central China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2020, 112, 104059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.Z.; Zhu, R.K.; Hu, S.Y.; Hou, L.H.; Wu, S.T. Accumulation contribution differences between lacustrine organic-rich shales and mudstones and their significance in shale oil evaluation. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2020, 47, 1160–1171, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Ji, L.M.; Su, A.; Wu, Y.D.; Zhang, M.Z.; Zhou, S.X.; Li, J.; Hao, L.W.; Ma, Y. Source-rock evaluation and depositional environment of black shales in the Triassic Yanchang Formation, southern Ordos Basin, north-central China. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 173, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Ji, L.M.; Wu, Y.D.; Su, A.; Zhang, M.Z. Characteristics of hydrothermal sedimentation process in the Yanchang Formation, south Ordos Basin, China: Evidence from element geochemistry. Sediment. Geol. 2016, 345, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.Y.; Wang, J.Q.; Qiu, X.W.; Zhang, D.D.; Zhao, J.F.; Zhao, H.G.; Deng, Y. Geodynamic environment and tectonic attributes of the hydrocarbon-rich sag in Yanchang Period of Middle-Late Triassic, Ordos Basin. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2020, 36, 1913–1930, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Scotese, C.R.; Wright, N. PALEOMAP Paleodigital Elevation Models(PaleoDEMS) for the Phaerozoic PALEOMAP Project. Available online: https://www.earthbyte.org/paleodem-resource-scotese-and-wright-2018/ (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Xian, B.Z.; Wang, J.H.; Gong, C.L.; Yin, Y.; Chao, C.Z.; Liu, J.P.; Zhang, G.D.; Yan, Q. Classification and sedimentary characteristics of lacustrine hyperpycnal channels: Triassic outcrops in the south Ordos Basin, central China. Sediment. Geol. 2018, 368, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Xian, B.Z.; Li, M.J.; Liang, X.W.; Wu, Q.R.; Zhang, W.M.; Wang, J.H.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.P. A giant lacustrine flood-related turbidite system in the Triassic Ordos Basin, China: Sedimentary processes and depositional architecture. Sedimentology 2021, 687, 3279–3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.S.; Hu, S.Y.; Bu, Q.U.; Bai, B.; Tao, S.Z.; Chen, Y.Y.; Pan, Z.J.; Lin, S.H.; Pang, Z.L.; Xu, W.L.; et al. Effects of lacustrine depositional sequences on organic matter enrichment in the Chang 7 Shale, Ordos Basin, China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2021, 124, 104778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Li, S.L.; Yu, X.H.; He, F.Q.; Li, S.L.; Qi, R. Sedimentary characteristics and evolution model of turbidites within a fourth-order sequence stratigraphic framework: A case study of the Triassic Chang 7 Member in Zhenjing area, Ordos Basin. Oil Gas Geol. 2022, 43, 859–876, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Nio, S.D.; Brouwer, J.H.; Smith, D.; Jong, M.D.; Böhm, A.R. Spectral trend attribute analysis: Applications in the stratigraphic analysis of wireline logs. First Break. 2005, 23, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ge, J.W.; Zhao, X.M.; Yin, G.F.; Zhou, X.S.; Wang, J.W.; Dai, M.L.; Sun, L.; Fan, T.G. Time scale and quantitative identification of sequence boundaries for the Oligocene Huagang Formation in the Xihu Sag, East China Sea Shelf Basin. Oil Gas Geol. 2022, 43, 990–1004, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Shi, H.C.; Xian, B.Z.; Liu, Y.C.; Yu, Z.Y.; Zhao, L.; Geng, J.Y.; Tian, R.H.; Wu, Q.R.; Liu, L.; Shuai, Y.J.; et al. High-frequency sequence patterns in lacustrine basins: Insights from delta-hyperpycnal flow systems in the Middle Jurassic shale interval, Sichuan Basin, China. Sediment. Geol. 2025, 487, 106948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, D.P.; He, Y.L.; Hou, X.L.; Zhou, B.; Wang, L.F.; Zhang, X.P.; Li, G.S.; Liu, J.Y.; Xiang, C.L.; Zhang, H.; et al. Sedimentary characteristics and evolution of sub-lacustrine fan in high-resolution sequence stratigraphic framework: A case study of the chang 7 member in qingbei area, Ordos basin, China. J. Palaeogeogr. 2025, 27, 611–624, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Gang, W.Z.; Liu, Y.Z.; Wang, N.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, C.Z.; Cao, Q.Y. High-resolution sediment accumulation rate determined by cyclostratigraphy and its impact on the organic matter abundance of the hydrocarbon source rock in the Yanchang Formation, Ordos Basin, China. Marine. Pet. Geol. 2019, 103, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.W.; Xian, B.Z.; Feng, S.B.; Chen, P.; You, Y.; Wu, Q.R.; Dan, W.D.; Zhang, W.M. Architecture and Main Controls of Gravity-flow Sandbodies in Chang 7 Member, Longdong Area, Ordos Basin. Acta Sedimentol. Sin. 2022, 40, 641–652, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 19145-2003; Specifications for 1:50000 regional geological survey in volcanic rock areas. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2003.

- GB/T 18602-2012; General rules for travel agency services. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2012.

- Espitalié, J.; Madec, M.; Tissot, B.; Mennig, J.; Leplat, P. Source Rock Characterization Method for Petroleum Exploration. In Proceedings of the Offshore Technology Conference, Houston, TX, USA, 1–4 May 1977; pp. 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 14506.28-2010; Methods for chemical analysis of silicate rocks—Part 28: Determination of sixteen major and minor elements content. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2010.

- GB/T 14506.30-2010; Methods for chemical analysis of silicate rocks—Part 30: Determination of forty-four elements content. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2010.

- Zhao, Z.Y.; Zhao, J.H.; Wang, H.J.; Liao, J.D.; Liu, C.M. Distribution characteristics and applications of trace elements in Junggar basin. Nat. Gas Explor. Dev. 2007, 30, 30–32. [Google Scholar]

- Moradi, A.V.; Sarı, A.; Akkaya, P. Geochemistry of the miocene oil shale (hançili formation) in the Çankırı-Çorum basin, central Turkey: Implications for paleoclimate conditions, source-area weathering, provenance and tectonic setting. Sediment. Geol. 2016, 341, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbanks, M.D.; Ruppel, S.C.; Rowe, H. High-resolution stratigraphy and facies architecture of the Upper Cretaceous Cenomanian-Turonian. Eagle Ford Group, Central Texas. AAPG Bull. 2016, 1003, 379–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J. Sedimentology of the Upper Pennsylvanian organic-rich Cline Shale, Midland Basin: From gravity flows to pelagic suspension fallout. Sedimentology 2020, 68, 805–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.M.; Goldring, R. Description and analysis of bioturbation and ichnofabric. J. Geol. Soc. 1993, 150, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Gao, Y.; Wang, C. Process and Prospects of Lacustrine Varve Research. Acta Sedimentol. Sin. 2023, 41, 1645–1661. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, W.; Liu, G.D.; Stebbins, A.; Xu, L.M.; Niu, X.B.; Luo, W.; Li, C. Reconstruction of redox conditions during deposition of organic-rich shales of the Upper Triassic Yanchang Formation, Ordos Basin, China. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2017, 486, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Wan, S.M.; Liu, X.T. Research progress on geochemical behavior of minerals and elements in early diagenesis of marine sediments. Acta Sedimentol. Sin. 2022, 40, 1172–1187. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.B.; Liu, H.Q.; Pan, S.X.; Wang, J. The past, present and future of research on deep-water sedimentary gravity flow in lake basins of China. Acta Sedimentol. Sin. 2019, 37, 904–921. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.Y.; Li, P.; Jiang, L.; Jin, Z.J.; Liang, X.P.; Zhu, D.Y.; Pang, Q.; Zhang, R.; Liu, J.Y. Distinctive volcanic ash-rich lacustrine shale deposition related to chemical weathering intensity during the Late Triassic: Evidence from lithium contents and isotopes. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, 6594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, R.C. Astronomical calibration of a ten-million-year Triassic lacustrine record in the Ordos Basin, North China. Sedimentology 2023, 70, 407–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.K.; Cui, J.W.; Deng, S.H.; Luo, Z.; Lu, Y.Z.; Qiu, Z. High-precision dating and geological significance of chang 7 tuff zircon of the Triassic Yanchang formation, ordos basin in central China. Acta Geol. Sin. Engl. Ed. 2019, 93, 1823–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.W.; Zhu, R.K.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Jahandar, R.; Li, Y. High Resolution ID-TIMS Redefines the Distribution and Age of the Main Mesozoic Lacustrine Hydrocarbon Source Rocks in the Ordos Basin, China. Acta Geol. Sin. Engl. Ed. 2023, 97, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.L.; Ma, S.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Mao, Z.G.; Han, T.Y.; Shi, Z.Q. U-Pb ages of tuff from the Triassic Yanchang Formation in the Ordos Basin: Constraints on palaeoclimate and tectonics. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2023, 150, 106128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embry, A.F. Transgressive-regressive (T-R) sequence analysis of the Jurassic succession of the sverdrup basin, Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Can. J. Earth Sci. 1993, 30, 301–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embry, A.F. Practical sequence stratigraphy XIV: Correlation. Can. Soc. Pet. Geologists 2009, 36, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Embry, A.F.; Johannessen, E.P. Two approaches to sequence stratigraphy. Stratigr. Timescales 2017, 2, 85–118. [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer, E.W. The influence of source rock type, chemical weathering and sorting on the geochemistry of clastic sediments from the Quetico metasedimentary belt, Superior Province. Can. Chem. Geol. 1986, 55, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.H.; Zeng, W.R.; Li, Z.P.; Chen, X.; Man, K.X.; Zhang, Z.H.; Wang, G.L.; Shi, S. Differential enrichment mechanisms of organic matter in the Chang 7 Member mudstone and shale in Ordos Basin, China: Constraints from organic geochemistry and element geochemistry. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2022, 601, 111126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.M.; Wu, T.; Li, L.T. Paleoclimatic characteristics during sedimentary period of main source rocks of Yanchang Formation (Triassic) in eastern Gansu. Acta Sedimentol. Sin. 2006, 24, 426–431, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Ji, L.M.; Wang, S.F.; Xu, J.L. Acritarch assemblage in Yanchang Formation in eastern Gansu province and its environmental implications. Earth Sci.—J. China Univ. Geosci. 2006, 31, 798–806. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.Y.; Liu, Y.Q.; Zhou, D.W.; Jiao, X.; Cao, Q.; Meng, Z.Y.; Zhao, M.R. Lithotypes, organic matter and paleoenvironment characteristics in the Chang73 submember of the Triassic Yanchang Formation, Ordos Basin, China: Implications for organic matter accumulation and favourable target lithotype. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 216, 110691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G. Organic Matter Enrichment of Fine-Grained Source Rock in Shollow Lake Facies: An Example from Chang 7 Unit Source Rock in Yanchi-Dingbian Area. Ph.D. Thesis, China University of Petroleum, Beijing, China, 2021; p. 147. [Google Scholar]

- Vink, S.; Chambers, R.M.; Smith, S.V. Distribution of phosphorus in sediments from tomales bay, California. Mar. Geol. 1997, 139, 157–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribovillard, N.; Algeo, T.W.; Lyons, T.; Riboulleau, A. Trace metals as paleoredox and paleo-productivity proxies: An update. Chem. Geol. 2006, 232, 12–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.F.; Shao, D.Y.; Lv, H.G.; Zhang, X.L.; Shao, D.Y.; Yan, J.P.; Zhang, T.W. A relationship between elemental geochemical characteristics and organic matter enrichment in marine shale of Wufeng Formation, Sichuan Basin. Acta Petrol. Sinca 2015, 36, 1470–1483, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Algeo, T.J.; Kuwahara, K.; Sano, H.; Bates, S.; Lyons, T.; Elswick, E.; Maynard, J.B. Spatial variation in sediment fluxes, redox conditions, and productivity in the Permian-Triassic Panthalassic Ocean. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2011, 308, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.; Manning, D.A.C. Comparison of geochemical indices used for the interpretation of palaeoredox conditions in ancient mudstones. Chem. Geol. 1994, 111, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raiswell, R.; Buckley, F.; Berner, R.A.; Anderson, T.F. Degree of Pyritization of Iron as a Paleoenvironmental Indicator of Bottom-Water Oxygenation. J. Sediment. Res. 1988, 58, 812–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raiswell, R.; Berner, R.A. Pyrite and organic matter in Phanerozoic normal marine shales. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1986, 50, 1967–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimmer, S.M. Geochemical paleoredox indicators in Devonian-Mississippian black shales, central Appalachian Basin (USA). Chemical Geology 2004, 206, 373–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, A.; Gentzis, T.; Ied, I.M.; Ahmed, M.S.; Wagreich, M. Paleoenvironmental Conditions and Factors Controlling Organic Carbon Accumulation during the Jurassic–Early Cretaceous, Egypt: Organic and Inorganic Geochemical Approach. Minerals 2022, 12, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, A.; Martizzi, P.; Ahmed, M.S.; Chiyonobu, S.; Gentzis, T. Weathering Intensity, Paleoclimatic, and Progressive Expansion of Bottom-Water Anoxia in the Middle Jurassic Khatatba Formation, Southern Tethys: Geochemical Perspectives. Minerals 2024, 14, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zheng, D.; Xie, G.; Jenkyns, H.C.; Guan, C.; Fang, Y.; He, J.; Yuan, X.; Xue, N.; Wang, H.; et al. Recovery of lacustrine ecosystems after the end-Permian mass extinction. Geology 2020, 48, 609–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelts, K.R. Environments of deposition of lacustrine petroleum source rocks: An introduction. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spéc. Publ. 1988, 40, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample NO. | Well | Depth (m) | Fourth-Order Sequence | TOC (%) | Tmax (°C) | HI (mgHC/gTOC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | H269 | 2492.8 | PSS2 | 0.88 | 441.00 | 65.77 |

| 2 | H269 | 2494.3 | PSS2 | 3.92 | 450.00 | 240.32 |

| 3 | H269 | 2496.2 | PSS2 | 4.17 | 450.00 | 199.14 |

| 4 | H269 | 2498.2 | PSS2 | 5.17 | 445.00 | 198.34 |

| 5 | H269 | 2500.0 | PSS2 | 3.90 | 441.00 | 158.15 |

| 6 | H269 | 2502.1 | PSS2 | 7.37 | 442.00 | 224.09 |

| 7 | H269 | 2503.1 | PSS2 | 10.53 | 448.00 | 294.78 |

| 8 | H269 | 2506.6 | PSS2 | 10.89 | 450.00 | 265.01 |

| 9 | H269 | 2507.8 | PSS2 | 4.71 | 446.00 | 289.78 |

| 10 | H269 | 2512.7 | PSS2 | 5.20 | 442.00 | 269.41 |

| 11 | H269 | 2515.6 | PSS2 | 3.65 | 439.00 | 233.63 |

| 12 | H269 | 2517.5 | PSS2 | 3.23 | 436.00 | 229.41 |

| 13 | H269 | 2519.8 | PSS1 | 7.90 | 449.00 | 293.14 |

| 14 | H269 | 2521.2 | PSS1 | 7.74 | 449.00 | 282.95 |

| 15 | H269 | 2523.7 | PSS1 | 7.84 | 450.00 | 300.32 |

| 16 | H269 | 2526.5 | PSS1 | 5.34 | 439.00 | 262.12 |

| 17 | H269 | 2528.5 | PSS1 | 3.99 | 444.00 | 293.26 |

| 18 | H269 | 2530.8 | PSS1 | 8.18 | 448.00 | 267.33 |

| 19 | H269 | 2532.8 | PSS1 | 10.04 | 450.00 | 291.04 |

| 20 | H269 | 2534.0 | PSS1 | 6.23 | 446.00 | 304.91 |

| 21 | H269 | 2536.8 | PSS1 | 4.88 | 446.00 | 319.60 |

| Sample NO. | Well | Depth | Sequence | C-Value | Sr/Cu | Sr/Ba | V/Cr | Ni/Co | U/Th | DOPT | P/Ti | P/Al | Ni + Cu + Zn (ppm) | Ti/Al | Zr/Al (ppm/%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | H269 | 2492.8 | PSS2 | 0.73 | 7.30 | 0.29 | 1.78 | 1.44 | 0.22 | 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.01 | 176.24 | 0.04 | 8.95 |

| S2 | H269 | 2494.3 | PSS2 | 1.00 | 4.07 | 0.32 | 2.48 | 1.80 | 0.44 | 0.05 | 0.23 | 0.01 | 226.72 | 0.04 | 9.55 |

| S3 | H269 | 2496.2 | PSS2 | 0.80 | 8.56 | 0.45 | 1.78 | 1.57 | 0.31 | 0.02 | 0.65 | 0.03 | 211.58 | 0.05 | 13.17 |

| S4 | H269 | 2498.2 | PSS2 | 1.02 | 7.62 | 0.45 | 1.82 | 2.03 | 0.39 | 0.05 | 0.25 | 0.01 | 219.80 | 0.05 | 13.09 |

| S5 | H269 | 2500.0 | PSS2 | 1.28 | 12.84 | 0.56 | 1.75 | 1.70 | 0.36 | 0.01 | 1.20 | 0.06 | 181.82 | 0.05 | 17.73 |

| S6 | H269 | 2502.1 | PSS2 | 0.64 | 19.34 | 0.91 | 2.26 | 1.86 | 0.60 | 0.44 | 3.62 | 0.15 | 193.82 | 0.04 | 17.55 |

| S7 | H269 | 2503.3 | PSS2 | 1.12 | 5.74 | 0.54 | 2.53 | 2.28 | 1.02 | 0.48 | 0.52 | 0.02 | 223.07 | 0.04 | 12.41 |

| S8 | H269 | 2506.6 | PSS2 | 1.21 | 4.93 | 0.55 | 2.72 | 1.74 | 0.93 | 0.56 | 0.51 | 0.02 | 257.74 | 0.05 | 13.26 |

| S9 | H269 | 2507.8 | PSS2 | 0.89 | 6.35 | 0.57 | 1.65 | 4.45 | 0.43 | 0.31 | 0.29 | 0.01 | 241.19 | 0.04 | 15.69 |

| S10 | H269 | 2512.7 | PSS2 | 1.00 | 5.59 | 0.52 | 1.89 | 2.23 | 0.31 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.01 | 166.22 | 0.05 | 18.16 |

| S11 | H269 | 2515.6 | PSS2 | 0.95 | 10.63 | 0.54 | 2.00 | 1.74 | 0.47 | 0.05 | 0.66 | 0.04 | 173.32 | 0.05 | 22.40 |

| S12 | H269 | 2517.5 | PSS2 | 1.10 | 8.76 | 0.48 | 1.96 | 1.53 | 0.34 | 0.04 | 0.53 | 0.03 | 200.04 | 0.05 | 15.75 |

| S13 | H269 | 2519.8 | PSS1 | 1.17 | 3.73 | 0.44 | 2.54 | 1.99 | 0.69 | 0.44 | 0.52 | 0.02 | 204.49 | 0.04 | 12.34 |

| S14 | H269 | 2521.2 | PSS1 | 0.99 | 4.80 | 0.50 | 2.49 | 2.05 | 0.41 | 0.32 | 0.60 | 0.03 | 216.27 | 0.04 | 10.40 |

| S15 | H269 | 2523.7 | PSS1 | 0.80 | 7.19 | 0.57 | 2.86 | 2.92 | 0.88 | 0.15 | 2.48 | 0.09 | 223.59 | 0.04 | 13.08 |

| S16 | H269 | 2526.5 | PSS1 | 1.55 | 4.22 | 0.55 | 2.35 | 2.19 | 0.72 | 0.06 | 0.66 | 0.03 | 217.44 | 0.04 | 16.26 |

| S17 | H269 | 2528.5 | PSS1 | 0.79 | 5.05 | 0.45 | 1.77 | 1.93 | 0.38 | 0.06 | 0.30 | 0.01 | 192.47 | 0.05 | 15.85 |

| S18 | H269 | 2530.8 | PSS1 | 1.21 | 2.92 | 0.50 | 2.29 | 2.24 | 0.84 | 0.46 | 0.51 | 0.02 | 234.43 | 0.05 | 13.52 |

| S19 | H269 | 2532.8 | PSS1 | 1.01 | 3.46 | 0.76 | 2.26 | 2.34 | 1.31 | 0.49 | 1.25 | 0.05 | 239.44 | 0.04 | 13.62 |

| S20 | H269 | 2534.0 | PSS1 | 0.90 | 2.68 | 0.42 | 2.11 | 2.21 | 0.49 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.01 | 198.81 | 0.05 | 12.89 |

| S21 | H269 | 2536.8 | PSS1 | 0.38 | 3.68 | 0.37 | 3.21 | 2.06 | 0.93 | 0.34 | 0.40 | 0.01 | 154.60 | 0.03 | 11.44 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, M.; Zhu, X.; Ji, W.; Lin, X.; Ye, L. Effect of Sedimentary Environment on Mudrock Lithofacies and Organic Matter Enrichment in a Freshwater Lacustrine Basin: Insight from the Triassic Chang 7 Member in the Ordos Basin, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10248. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210248

Zhang M, Zhu X, Ji W, Lin X, Ye L. Effect of Sedimentary Environment on Mudrock Lithofacies and Organic Matter Enrichment in a Freshwater Lacustrine Basin: Insight from the Triassic Chang 7 Member in the Ordos Basin, China. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):10248. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210248

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Meizhou, Xiaomin Zhu, Wenming Ji, Xingyue Lin, and Lei Ye. 2025. "Effect of Sedimentary Environment on Mudrock Lithofacies and Organic Matter Enrichment in a Freshwater Lacustrine Basin: Insight from the Triassic Chang 7 Member in the Ordos Basin, China" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 10248. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210248

APA StyleZhang, M., Zhu, X., Ji, W., Lin, X., & Ye, L. (2025). Effect of Sedimentary Environment on Mudrock Lithofacies and Organic Matter Enrichment in a Freshwater Lacustrine Basin: Insight from the Triassic Chang 7 Member in the Ordos Basin, China. Sustainability, 17(22), 10248. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210248