Abstract

Climate change observed in recent decades has, in most cases, negatively impacted on the operations of non-financial and agricultural enterprises. Filling a gap in the economic literature, this article presents the results of a study on the impact of rising temperature on the resilience to bankruptcy risk of over four thousand agricultural enterprises operating in Poland between 2016 and 2023, taking into account temperature and macroeconomic conditions of regions of their operation and assessing resilience with Altman (Z-score) and Zmijewski (X-score) methods. Using panel regression, it was demonstrated that temperature changes have a significant nonlinear (parabolic) effect on enterprise resilience. An increase in annual average temperatures above the long-term average weakens enterprise resilience. A generally similar, although individually variable relationship occurs for changes in average temperatures in spring, autumn, and winter. In the summer, this relationship is ambiguous. Furthermore, the resilience to bankruptcy risk improves growth in regional GDP and agricultural production, as well as enterprise’s assets, profitability and the share of equity in the financing structure. The conclusions can be used by agricultural enterprises in preparing contingency plans in the event of potential temperature shocks, and public administration for developing programs to protect agriculture against temperature shocks and food security plans.

1. Introduction

Gradual temperature increases, heavy and irregular rainfall, strong winds, floods, and other effects of a changing climate impact business operations and households in diverse ways. In the case of temperature, its dynamic increase typically negatively impacts crop yields and animal husbandry, public health, working conditions, and employee productivity. The existing research indicates that beyond certain temperature thresholds, not only does business efficiency deteriorate, but also the value of human capital, which is exposed to reduced concentration capacity and an increased risk of accidents, injuries, and illnesses [1,2,3]. Another significant consequence of climate warming for business operations is the migration of populations from drought-affected regions to highly industrialized countries, including the European Union, and from rural areas to cities [4]. This process, on the one hand, temporarily worsens the state of public finances in the host country due to the payment of increased social benefits, but on the other hand, it increases human capital resources and improves the demographic situation and the labor market [5].

Agriculture is one of the sectors most vulnerable to the risk of climate change [6]. Research findings most often point to the negative impact of rising temperatures and changing rainfall patterns on the yields of cereals and other agricultural crops [7,8,9,10,11,12,13], with this decline being most acute in the 21st century [14]. The deterioration in agricultural economic efficiency therefore contributes to significant losses for agricultural enterprises and, consequently, to an increased risk of bankruptcy.

In assessing the vulnerability of enterprises to rising atmospheric temperatures, studies conducted in the non-financial sector [3,15,16,17] and the agri-food sector [18,19,20,21] indicate that rising temperatures reduce the efficiency of enterprises. Research has shown that in many cases, a company’s geographic location, the environmental conditions prevailing in its surroundings, and the composition of agricultural crops have a significant impact on the relationship between temperature changes and company performance [22,23,24]. Rising temperatures worsen agricultural growing conditions in most countries, particularly in their southern regions. However, on the other hand, it contributes to the shift of many crops and increases in their production in northern regions, including in China [25,26], the USA [27], and Europe [28,29]. It also increases cultivated areas in northern regions and influences changes in the structure of cultivated plants [30,31], and their vegetation cycles [32].

Furthermore, the ability of companies to prevent negative impacts and adapt to climate change depends on the level of technological development of a given region or country and its ability to finance the necessary investments [33,34]. Due to the lack of research indicating how agricultural enterprises in Poland react to temperature changes occurring in the region of their operations, the following research questions should be asked:

- How does an increase in annual and seasonal temperatures above the long-term average affect the level of bankruptcy risk of an agricultural enterprise?

- What is the type of relationship between the increase in temperature above the long-term average and the level of bankruptcy risk of an agricultural enterprise?

To the authors’ knowledge, the literature on the impact of climate change on the level of risk in agricultural enterprises is limited. In most cases, the subject of research are enterprises from the banking [35,36,37,38], insurance [39,40], construction [41,42,43], and automotive [44] sectors. Another significant group of studies on the risks posed by climate change assesses the impact of rising atmospheric temperature on the national economy, including the size and dynamics of GDP growth [6,45], and domestic exports [46]. The results of the research presented contribute to the economic literature in four main areas. First, the study for the first time determines the level of bankruptcy risk for agricultural enterprises in Poland using the Altman Z-score and Zmijewski X-score models simultaneously. Second, the study assesses for the first time, the impact of climate change on the bankruptcy risk of agricultural enterprises, considering the climatic and macroeconomic characteristics of their home voivodeships (hereinafter referred to as regions). Third, the study confirms the negative nonlinear effect of rising temperature in the region where agricultural enterprises operate on their bankruptcy risk. Fourth, the study confirms the varying impact of rising temperature on the bankruptcy risk of agricultural enterprises for different seasons. The identification of these problems can be used in the preparation of: (i) credit risk assessment by credit and insurance institutions, (ii) long-term investment plans by agricultural enterprises, and (iii) investment strategies of government and local government administration aimed at making the local and national economy more resistant to the destructive impact of climate change and adapting its operations to changing weather conditions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Impact of Temperature Increases on Companies’ Performance

Reports from government and international organizations, as well as scientific research, indicate that the climate change currently experienced is, in most cases, negatively impacting the economy and society [47]. The study of the development of nineteen economic sectors and their contribution to China’s GDP in 2012, confirms that the increase in average annual temperature causes the greatest damage in agriculture, manufacturing, construction, wholesale and retail trade, real estate, and the financial sector [48]. Similarly, data on yields and insurance payments in the United States showed that prolonged droughts were the most important causes of the decline in corn production between 1991 and 2006 [49]. Furthermore, the study of the impact of temperature on working hours in the United States between 2003 and 2006 [50] shows that employees of agricultural enterprises, construction, and industrial processing industries are most vulnerable to the negative impact of climate warming.

Assessing the impact of rising air temperature on economic performance indicates that such relationship is diverse and depends, among other factors, on the level of economic development of a given country and its geographic location [46]. It also confirms that, particularly in low-income countries, climate warming negatively impacts their export capacity. The sectors most vulnerable to export disruptions are agriculture and the processing industry. In the case of agriculture, vulnerability to climate change is explained by the deterioration of plant growth conditions and a decline in agricultural production, while in the processing industry, vulnerability is explained by reduced employee productivity and increased costs of adapting to work in elevated temperatures.

Similarly, based on a study of national GDP values obtained between 1950 and 2003, it was found that rising temperatures weaken the rate of economic growth in low-income countries largely dependent on agriculture, while they do not significantly change it in high-income countries [45]. This relationship is justified by the fact that wealthier countries have a greater level of financial independence and greater opportunities to diversify sources of economic income and compensate for losses incurred, for example, in agriculture by increasing revenues from other economic sectors. Furthermore, in countries with high average annual temperatures, additional temperature increases further worsen their economic situation. Similar conclusions were drawn from a study of the relationship between temperature rise and production volume in 28 countries of the Caribbean region between 1970 and 2006 [51]. It was found that the change in average temperature statistically significantly impacts the production volume in agriculture and three non-agricultural sectors: (i) trade and tourism, (ii) mining, and (iii) other services.

Furthermore, the study considering the geographic diversity of countries and their climatic conditions indicates that a 1 °C-temperature increase can contribute to a 2.4% decrease in aggregate non-agricultural production and a 1% decrease in agricultural production. Conversely, in countries with low average annual temperatures, temperature increases have a beneficial impact on the economy and contribute to GDP growth and social well-being [52]. Furthermore, when assessing the economic damage caused by climate change in agriculture and the energy sector in the United States, it was found that the relationship between temperature rise, and economic performance is non-linear [53]. This is since the increase in average global temperature systematically and nonlinearly reduces labor productivity in the sectors studied. The research has also shown that climate risk is unevenly distributed geographically, particularly affecting the poorer southern states and leading to significant value transfers from the southern states to the northern and western states, deepening economic inequality within the country.

Another international study indicates that heat shock and the associated decline in labor productivity are problems most noticeable in low-income and technologically less developed countries [54]. The lack of financial resources to adapt the economy to conditions of increased temperature contributes to the deterioration of financial performance in most operating enterprises. Consequently, economic losses resulting from climate change occur primarily in technologically less developed and poorer countries in South and Southeast Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Central America. Furthermore, with more frequent droughts, the lower level of institutional and social development and strong dependence of these countries’ economies on agriculture, lead to economic crises and social unrest [55,56,57]. However, research conducted among Nigerian farmers indicates that while socio-economic factors (capital and assets such as land) are important determinants of climate change adaptation, there are also other key factors, such as perceptions, that can bridge capital and asset shortfalls [58].

In assessing the relationship between climate risk and the performance of agriculture and operating in the rural areas SMEs, it is important to note that vulnerability and adaptability to global warming depend on the region’s geographic location and the type of agricultural activity conducted within it. Using panel weather and grain yield data from approximately 2500 counties in China over a 20-year period, it was demonstrated that the impact of temperature varies depending on agricultural specialization, i.e., grain cultivation, animal husbandry, forestry, and fisheries. Warming caused the greatest losses in regions specializing in grain cultivation and animal husbandry, while benefits were felt in areas dominated by the forestry sector [59].

Considering that a significant number of agricultural enterprises in Poland are relatively small and operate primarily within their own region, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1.

An increase in atmospheric temperature in an agricultural enterprise’s home region increases the risk of bankruptcy.

2.2. Nonlinearity of the Relationship Between Temperature Increase and Companies’ Performance

The second significant result of a study conducted on a sample of Chinese enterprises is the finding of a nonlinear relationship between temperature increases and their production volume [59]. Operating at temperatures below the 21–24 °C range, temperature increases positively contribute to increased employee productivity and, therefore, additional production growth for enterprises. However, beyond this range, additional temperature increases lead to a sharp decline in production growth.

In agriculture, using regional data on corn and soybean yields and daily weather data (including minimum and maximum temperatures), it was demonstrated that the relationship between weather changes and yields in China between 2000 and 2009 is nonlinear and inverted U-shaped [60]. At temperatures below this threshold, grain yields increase, but above it, they decrease. Similar conclusions regarding the nonlinear relationship between temperature increases and corn, soybean, and cotton yields were obtained from studies using daily weather data and yield data for individual counties in the United States [61]. A study of corn and soybean crop yields from 1950 to 2010, based on daily temperatures, indicates an asymmetric relationship between temperature increases and crop yields. Moderate temperature increases were found to improve yields, while yields declined sharply after exceeding extreme temperatures. Similar relationships were found for Sub-Saharan Africa [62]. A nonlinear effect of temperature on corn yield was also reported in the study conducted in 13 US Midwestern states from 1929 to 2014 [63].

Considering the results of the above studies, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2.

An increase in temperature has a nonlinear effect on the risk of bankruptcy of agricultural enterprises.

2.3. Seasonal Specificity of Temperature Impact on Companies’ Performance

Research conducted in the United States in selected economic sectors indicates that rising temperatures significantly and permanently weaken the GDP growth rate [6]. However, it was found that the impact of temperature varies depending on temperature changes in different seasons. Warming had the greatest impact on economic performance during the summer months. It was estimated that a 1 °F temperature increase contributes to a 0.15–0.25 percentage point reduction in the annual growth rate of state’s GDP. In autumn, however, climate warming has positive effects, although significantly smaller than the losses in the summer months. As a result, environmental warming throughout the year significantly worsens the economic situation of the state and the country.

Similarly, based on daily weather data and financial and location data on enterprises in China, it was found that temperature spikes in spring have a positive impact on business performance, while those in summer have a negative impact [60]. Based on global data on agricultural crops and climate change from 1984 to 2020, the relationship between temperature increase and crop yields was found to be nonlinear (inverted U-shaped). After a certain temperature is exceeded, further increases worsen crop performance, but the temperature thresholds for major cereals, including wheat, rice, and maize, differ. This means that the impact of temperature increases on agricultural performance in a given area depends on the crop structure, resulting in geographically diverse sensitivity of agricultural performance to temperature increases [64].

Since in Poland, plant vegetation and the organization of business activities vary in different seasons, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3.

In different seasons of the year, rising temperatures have a different impact on the risk of bankruptcy of agricultural enterprises.

3. Material and Methods

Methods for assessing corporate bankruptcy risk typically fall into two categories based on the type of data used: (i) accounting and (ii) market. The most frequently used method in the first group is Altman’s model (1968), which assesses a company’s credit quality using historical balance sheet data [64]. Zmijewski uses similar financial data to examine the level of resilience to bankruptcy risk [65]. The basic market method, however, is the “distance-to-default” method. This method determines the number of standard deviations of a company’s assets from the insolvency threshold, which can be explained by how much further the value of assets can change before the company becomes insolvent [66,67,68].

Although research on the risk of bankruptcy began in the first half of the twentieth century, it was not until Altman (1968) used a single indicator aggregating multiple variables describing the financial and market situation of a company that a comprehensive assessment of the risk of bankruptcy faced by the company was possible [64]. The parameters of this indicator have been repeatedly refined and adapted to economic changes and the specific nature of the analyzed economic sector or the state of the development of the regional economy [69,70].

Since the study sample consists almost entirely of small and medium-sized enterprises not listed on the stock exchange, Altman’s (2016) method, adapted to SMEs operating in emerging markets, was used to determine the level of bankruptcy risk [69]. This method was applied in a cross-sectional risk assessment of SMEs from various economic sectors [32,71,72] as well as those operating in the agri-food sector [73,74,75,76,77,78]. The model has the following form:

where: —bankruptcy risk indicator, X1—working capital/total assets, X2—retained earnings/total assets, X3—operating profits/total assets, X4—book value of equity/book value of total liabilities.

The value of the Z-score allows to classify companies into zones based on their probability of bankruptcy in the near future:

Z-score > 5.85—low risk of company bankruptcy (the company is in a safe zone),

3.75 < Z-score < 5.85—moderate risk of company bankruptcy (the company is in an intermediate zone),

Z-score < 3.75—high risk of company bankruptcy (the company is in the danger zone).

To improve the accuracy of the obtained results regarding the level of bankruptcy risk, the study utilized the second, relatively frequently used X-score method developed by Zmijewski (1984) [65]. In this method, indicators reflecting the company’s profitability, financial leverage, and financial liquidity are first determined using balance sheet data. Based on these data, the X-score is calculated. This method was used in cross-sectional assessments of non-financial enterprises in the SME sector [79,80,81]. The model has the following form:

where: —bankruptcy risk indicator, X1—net income/total assets (roa), X2—total liabilities/total assets (leverage), X3—current assets/current liabilities (current ratio). Both methods aim to indicate a company’s resilience to bankruptcy risk using a single indicator. The Altman method, in its various versions, utilizes data on sales, operating profit, retained earnings, working capital, and financial leverage. In the Zmijewski method, the final value of the X-score depends on only three components. Such designs mean that, on the one hand, a larger amount of input data allows the Altman method to obtain more precise results, while on the other hand, the smaller number of variables necessary to determine the X-score allows the study to be applied to a larger number of companies, particularly small ones. Such variables as “retained earnings” and often “operating profit” are rarely reported by small companies, which means that they cannot be the subject of bankruptcy risk assessment.

Unlike Altman’s model, which uses threshold levels for the Z-score to differentiate a company’s risk level, Zmijewski’s model assigns X-score values to two classes of companies. An X-score below zero indicates that the company is in good financial condition, while in other cases, it is considered that the company may experience financial difficulties in the near future.

Once values of Z-score and X-score were known, to assess the impact of the temperature change on the level of risk of company bankruptcy, panel estimation with fixed effects was used according to the model:

where: for the time t, region j, and company i: dependent variable Yit—Z-score, X-score; Xit—explanatory variables at the company level: assets—natural logarithm of the real value of the enterprise’s total assets adjusted by the GDP deflator, leverage—ratio of equity to total assets, roa—return on assets measured as net income to total assets, eff_asset—asset efficiency measured as sales over total assets, short_liab—share of short-term liabilities in total liabilities; and for each region: Macrojt—macroeconomic variables characterizing the region j: GDP—real GDP growth rate, GDPpc—GDP per capita, agri_prod—agricultural production; Tempjt—temperature variables characterizing the region j: ΔTyr—annual average of the differences between the monthly average and the long-term average temperature (long-term, i.e., the average in the period 2004–2023); ΔTyr2 − ΔTyr to the 2nd power; ΔTsp—quarterly average of the differences between the monthly average and the long-term average temperature; ΔTsp2 − ΔTsp to the 2nd power (ΔTsu, ΔTau, ΔTwi for summer, autumn and winter, respectively), µi_– unobservable and not included in the regression equation individual effect specific to a given company i; εit—random component of the model.

The choice of fixed-effects model estimation is based on the Hausman test which null hypothesis states that difference in coefficients is not systematic, i.e., that random-effects model is a correct estimation method. The null hypothesis is resoundingly rejected in our case (chi-2 statistic = 159.47, p-value = 0.0000 in case of the z-score model with divergence of temperature from the long-term average), thus pointing at fixed-effects estimation as a better choice.

The statistical tests of the panel regressions have revealed that models do not fulfil conditions of homoscedasticity (modified Wald test for groupwise heteroskedasticity with null hypothesis of homoscedasticity: chi-2 statistic = 6.6 × 1036, p-value = 0.0000) and lack of autocorrelation (Wooldridge test for autocorrelation in panel data will null hypothesis of no autocorrelation: F-stat = 92.080, p-value = 0.0000). To correct for this bias, the clustered standard error estimates, which are robust to disturbances being heteroscedastic and autocorrelated, were applied. In the context of fixed effects estimation, they specifically allow for the within-group correlation (here, group means each firm), relaxing the usual requirement for independence of observations.

Prior to estimations, the outlier observations for Z-score and X-score values were identified using the rule of 1.5 times the interquartile range (IQR) of the data. All observations below the first quartile decreased by 1.5 times interquartile range (Q1 − 1.5·IQR) and above the third quartile enlarged by 1.5 times interquartile range (Q3 + 1.5·IQR), were discarded.

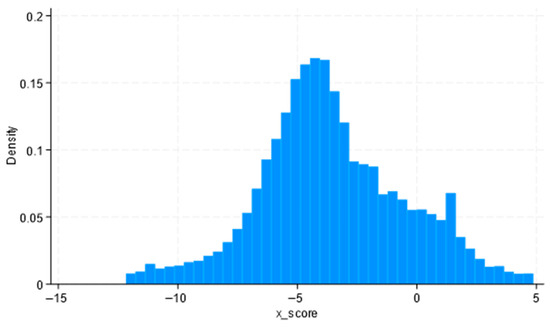

As a result, the research sample consists of enterprises whose primary area of activity is agriculture, including, among others: animal breeding, cultivation of cereals, legumes, fruit and vegetables, fishing, forestry and hunting (see Table 1). The distributions of the Z-score and X-score variables are generally similar, although minor differences are evident in the histograms (see Figure A1 and Figure A2).

Table 1.

Number of observations by year.

Based on previous studies [45,82,83,84], the main group of explanatory variables representing climate change consists of variables characterizing the deviation of the average annual temperature in year t from the long-term average (see Figure 1). The long-term average temperature was determined based on monthly data from IMGW-PIB in the years 2004–2023.

Figure 1.

Average annual temperature and deviation of the annual temperature from the long-term average by region in the years 2004–2023. Source: own calculations based on the IMGW-PIB data. Note: Tyr—average annual temperature, ΔTyr—deviation of the annual temperature from the long-term average, Opole—temperature data available until 2015.

In the next stage, considering the results of studies taking into account the specific vegetation of cultivated agricultural plants [6,46,53,60], the average temperatures in four quarters were determined, i.e., for spring, summer, autumn and winter, and then these deviations of the average temperatures from the long-term quarterly average for each quarter (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Average quarterly temperature by region in the years 2004–2023. Source: own calculations based on the IMGW-PIB data. Note: Tsp; Tsu; Tau; Twi—average quarterly temperatures in spring, summer, autumn, winter, respectively, Opole—temperature data available until 2015.

Analysis of temperature changes in individual regions between 2004 and 2023 indicates that, despite significant temporal variability, the deviations in the average annual temperature and the average quarterly temperatures across seasons are trending upward. For individual regions, the deviations in the average annual temperature and the average quarterly temperatures change in similar directions, but the amplitude of these changes varies noticeably. The greatest variability in these variables is observed in winter, and the least in summer. Geographical variation in temperature changes may become the cause of changes in the structure of crops and their sensitivity to temperature increases in Poland, similarly to what was observed in China in the form of shifting rice cultivation to the northern regions [25].

In characterizing the changes in the agricultural sector in Poland, within which the analyzed companies operated, it should be noted that, according to Central Statistical Office (Statistics Poland) data, approximately 14.5 million hectares of agricultural land were used in Poland between 2016 and 2023, including approximately 11 million hectares of arable land. Gross agricultural production and production per hectare of agricultural land showed an upward trend, reaching PLN 186.6 billion and PLN 12,685, respectively, in 2023 (see Table 2). Moreover, the value of exports of plant and animal products increased from PLN 52 billion in 2016 to PLN 62.9 billion in 2019 and PLN 106.3 billion in 2023.

Table 2.

Gross agricultural output and exports of food and agricultural products.

4. Results

The research sample of enterprises and the climatic and macroeconomic variables characterizing the regions are described in Table 3.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics analysed variables.

Table 3 presents descriptive statistics for the Z-score and explanatory variables. The number of observations exceeds 23,000 in all cases. Z-score has an average of 7.62, a median of 6.43 (indicating a slightly right-skewed distribution) and a standard deviation of 7.66, what means that on average companies in the sample are at the safe zone with expectation of low risk of company bankruptcy (the minimum Z-score value of 5.85). The number of X-score observations is close to 18,000 in all cases. X-score has an average of −4.17, a median of −3.56 (indicating a slightly left-skewed distribution) and a standard deviation of 4.89, which means that on average most companies in the sample are at the safe zone with X-score below zero. Histograms of the distributions of values of both indicators are presented in Figure A1 and Figure A2.

The significantly higher mean value (USD 2835 thou.) than the median (USD 699 thou.) for assets, indicates that the sample is significantly diverse, consisting of a smaller group of companies with large assets and a significantly larger group of small companies. The high standard deviation (USD 11,726 thou.) also indicates strong dispersion. In turn, the mean and median values of asset efficiency (eff_assets), return on assets, and financial leverage (total equity to total assets) indicate that most companies are characterized by lower asset efficiency, but also by a higher return on assets and a higher share of equity in total assets, which may indicate that the companies maintain safe operating conditions. Significant standard deviation values indicate, as in the case of assets, substantial variation within the sample in terms of their financial stability. Regarding the characteristics of corporate liabilities, the average (47.7%) share of short-term liabilities in total liabilities for the sampled companies is slightly higher than the median (45%), which, given the relatively low standard deviation (77.9%), indicates a relatively even distribution of this variable.

The next stage of the study assessed the impact of the deviation of the average annual and quarterly temperature from the long-term temperature (hereinafter referred to as temperature change) on the resilience of agricultural enterprises to bankruptcy risk, represented by the Z-score and X-score. Considering the results of previous studies [20,53,59,60], the assessment was performed by representing the temperature change in the first and second power. The analyzed models also included variables characterizing the enterprise. In addition, to investigate how temperature changes occurred in each season affect the resilience of agricultural enterprises to bankruptcy, the same estimates were performed using the average quarterly temperature deviations for winter (December–February), spring (March–May), summer (June–August), and autumn (September–November). When analyzing the results, it should be noted that an increase in the Z-score indicates an improvement, while the X-score indicates a deterioration in resilience to bankruptcy risk. The estimation results of the analyzed models are presented in Table 4 and Table 5, for the Z-score and X-score, respectively.

Table 4.

The impact of deviations from the long-term temperature on the resilience of enterprises to the risk of bankruptcy (Z-score).

Table 5.

The impact of deviations from the long-term temperature on the resilience to the risk of enterprise bankruptcy (X-score).

The obtained results indicate that resilience to the bankruptcy risk, measured by both the Z-score (model 1) and X-score (models 6), is significantly dependent on changes in temperature measured by the ΔTyr variable. This relationship is nonlinear and parabolic. The obtained result is consistent with the results of previous studies, among others, for the USA and China [19,59,61]. The negative value of the coefficient for the ΔTyr2 variable indicates that the risk resilience function measured by the Z-score has the shape of an inverted parabola. The nonlinear parabolic relationship between bankruptcy risk resilience and temperature increase is confirmed by the positive value of the coefficient for the ΔTyr2 variable in model 6 with the X-score. This means that annual temperatures lower than the threshold temperature contribute to improved bankruptcy resilience, while higher temperatures worsen it.

To verify the obtained results, models 1–6 were additionally estimated using mean annual and quarterly temperatures for the years 2004–2015 (see Table A1 and Table A4), as well as using other estimation methods, i.e., random-effects panel regression (see Table A2 and Table A5) and the dynamic model (Arellano–Bond estimator) (see Table A3 and Table A6). These estimates confirmed the basic results obtained.

Determining the vertex point of the parabola function for Z-score and X-score with respect to temperature changes (ΔTyr) indicates that temperature drops approximately below the long-term temperature (and in the case of model 6 with X-score below the long-term temperature reduced by 0.7 °C) contribute to improving the company’s resilience to bankruptcy risk, while temperature increases above these limit temperatures contribute to weakening the resilience (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Temperature turning points for Z-score and X-score functions dependent on the ΔT and the share of cases of their exceedance in regions in 2016–2023.

The relationship between resilience to the bankruptcy risk of agricultural enterprises and temperature changes in individual calendar seasons varies, which is consistent with the results obtained in studies conducted for agricultural companies in the USA and China [6,60]. In the winter, the threshold temperatures above which the direction of the temperature changes affect resilience to bankruptcy risk changes are 3 °C (Z-score) and 1.4 °C (X-score), respectively. Some differences between the results may result from differences in the distributions of the Z-score and X-score variables. In spring, the change from the positive to negative impact on enterprise resilience to bankruptcy occurs when the average spring temperature equals to the long-term average minus 1.5 °C (for the Z-score) and minus 1.2 °C (for the X-score). In the case of autumn, the limit temperature value is approximately the long-term temperature.

In the case of summer, the relationship between corporate resilience to bankruptcy risk and changes in average temperature is ambiguous. In the case of the Z-score measure, an increase in temperature linearly, although with a rather small coefficient value, improves the company’s risk resilience. For the X-score measure, however, this relationship is nonlinear and parabolic, with an extreme at the long-term average temperature, meaning that temperature increases above the average temperature worsen corporate resilience. Given the small value of the ΔTsu2 coefficient of 0.004, it can be assumed that the impact of summer temperature on corporate resilience, as measured by the X-score, is negligible. It can be assumed that the difference between the Z-score and X-score results is due to the difference between the distributions of Z-score and X-score values (see Figure A1 and Figure A2).

Furthermore, the results indicate that temperatures recorded between 2016 and 2023 relatively frequently exceeded the threshold temperatures. In the case of the average annual temperature, the threshold temperatures were exceeded in all Polish regions, in 58.3% of cases for the Z-score and 88.5% for the X-score, respectively (see Table 6). In the case of quarterly average temperatures, the threshold exceeded most frequently (over 90%) in spring and summer. This means that the threat of a negative impact of rising temperatures on the risk of bankruptcy of agricultural enterprises is concentrated mainly in the spring and summer months, what is consistent with, among others, the results of a study of cereal yields in Poland between 2013 and 2020, indicating that extreme high temperatures between March and September lead to yield declines [84].

In turn, the sensitivity analysis of the Z-score and X-score indicators to changes in the ΔTyr indicates that an increase in ΔTyr by 1 °C can weaken the resilience of enterprises to the bankruptcy risk by approximately 0.1, measured by both indicators (see Table 7). The sensitivity of Z-score and X-score to changes in ΔT in winter, spring, and autumn is similar in direction, although different in magnitude. In the case of summer, due to the different form of the relationship between Z-score and ΔT, an increase in temperature improves risk resistance by 0.07.

Table 7.

Marginal effect for an increase in the ΔT by 1 °C.

The next step in the study was to examine the nature of the relationship between temperature changes and resilience to bankruptcy risk among companies with different asset sizes. For this purpose, companies were divided into the following groups:

- Large enterprises—with assets greater than the asset median,

- Medium-sized enterprises—with assets greater than the 20th percentile and less than the asset median,

- Small enterprises—with assets less than the 20th percentile.

Model estimations showed that temperature changes most often affect risk resilience in large enterprises, using both the Z-score and X-score measures (see Table A7 and Table A10). Similarly to the entire sample, a non-linear relationship (in the shape of an inverted parabola) between temperature increase and resilience to bankruptcy risk occurs for both annual and quarterly temperature increases in winter, spring and autumn. In summer, as for the entire sample, temperature increases linearly increase enterprise risk resilience.

For medium-sized enterprises, increases in the annual temperature did not have statistically significant impact on risk resilience. In case of summer the temperature increases have a statistically significant positive impact on the Z-score value (see Table A8 and Table A11). Additionally, using the X-score measure, the results indicate a statistically significant negative impact of temperature increases in winter. The bankruptcy resilience of small enterprises, on the other hand, is statistically significantly dependent on changes in the average annual temperature, and this relationship, like the entire sample, has the form of an inverted parabola (see Table A9 and Table A12).

These results indicate the sensitivity of bankruptcy risk to temperature increases at different times of the year for all types of businesses. Considering the impact of average annual temperature, large and small businesses are most at risk of temperature increases. These results are similar to the findings of research, which showed that in the period 2015–2019, medium-sized agri-food enterprises in Serbia were not at risk of bankruptcy, unlike micro and small enterprises [75].

Models estimated for both measures of corporate resilience also indicate a statistically significant impact of corporate characteristics on their resilience to bankruptcy risk. Increases in corporate asset size, asset efficiency, asset profitability, equity, and the share of short-term liabilities in the debt structure contribute positively to improved resilience.

The next step in the study was to examine whether incorporating macroeconomic variables specific to the company’s home region altered the previously obtained relationship between firms’ risk resilience and temperature changes. The macroeconomic variables used were GDP growth, GDPpc, and agricultural production in the region (see Table 8 and Table 9). In all estimated models, increases in GDP growth, GDPpc and agricultural production in the region had a statistically significant positive impact on the stability of agricultural firms. Because the estimation results for the GDP growth and GDPpc variables are similar, only the results for the GDP growth variable are presented in this article. The model estimation results confirm the existence of a statistically significant relationship between firm bankruptcy resilience and deviation of temperature from the long-term average. Increases in the deviation of the annual average temperature and quarterly averages for winter, spring, and autumn contribute to a deterioration in firms’ resilience to bankruptcy risk. Only in the summer do temperature changes have a statistically significant impact on enterprise resilience. This result may be related to the specific nature of agricultural activity and the growing season of crops, for which changes in summer temperature may not have as strong an impact as changes in spring, autumn, and winter.

Table 8.

The impact of temperature changes on the resilience to the risk of enterprise bankruptcy controlled by macroeconomic variables (Z-score).

Table 9.

The impact of temperature changes on the resilience to the risk of enterprise bankruptcy controlled by macroeconomic variables (X-score).

Similarly to models that do not consider macroeconomic variables, corporate risk resilience is positively influenced by increases in asset efficiency, asset profitability, equity, and the share of short-term liabilities in the debt structure.

5. Discussion

The results obtained confirm the hypotheses formulated at the beginning of the study. Estimations of models 1, 6, 11, 12, and 22 indicate that company resilience to the risk of bankruptcy deteriorates when average annual temperatures exceed the long-term temperature (for Z-score) or the long-term temperature reduced by 0.7 °C (for X-score), what is in line with the most existing research conducted in China [19,59,60] and the USA [61,62,63]. Furthermore, estimates of models 1 and 6 indicate that the relationship between these two variables is nonlinear and parabolic relationship. For the Z-score measure, the company’s resilience function on temperature is inverted, while for the X-score, it is a straight parabola. These results are consistent with those obtained in studies [20,53,59,61] on the situation of national economies, enterprises in the US, and agricultural enterprises in China, where the function of the dependence of enterprise performance on temperature was inverted U-shaped. Therefore, it can be expected that lower temperatures allow agricultural enterprises to achieve better economic results. Exceeding a certain temperature threshold introduces additional risk into their operations, which increases with rising temperature.

Another important finding of the study indicates that temperature increases occurring in different seasons have a varying impact on companies’ risk of bankruptcy resilience. Such results were achieved for the risk resilience measured with Z-score and X-score. In winter, spring, and autumn, the nature of the temperature impact is similar, but the strength of this impact varies. In winter, temperature increases negatively impact resilience only after exceeding the long-term temperature increased by 3 °C (for the Z-score) or 1.4 °C (for the X-score). These results are consistent with the findings of a study of companies in the USA, which indicated that companies in the colder northern states improved their performance with increasing temperatures, unlike the warmer southern states [6]. Other studies based on international comparisons and in various parts of China also indicate benefits from temperature increases in regions with normal low temperatures [59,60].

Moreover, sensitivity analysis indicates that risk resilience is most sensitive to temperature changes in winter compared to other seasons. In turn, in spring, the threshold temperature from which a temperature increase reduces the resilience of companies to the risk of bankruptcy is the long-term temperature reduced by approximately 1.5 °C (for the Z-score and X-score). In autumn, the impact of changes in temperature on enterprise resilience shifts from positive to negative approximately once the long-term temperature is exceeded. Furthermore, the sensitivity of enterprise resilience to temperature changes in spring and autumn is similar.

In summer, the impact of temperature changes on company resilience is heterogeneous. On the one hand, in the case of the Z-score, the increase in temperature linearly improves the firm’s resilience, while in the case of the X-score the relationship has a weak non-linear parabolic character. Such difference may be caused by a slight difference between the distribution of the Z-score and X-score values. Moreover, the estimation results of models incorporating macroeconomic variables indicate no statistically significant impact of changes in average summer temperatures on company resilience. In turn, another explanation of the obtained results may be related to the typical characteristics of agricultural production in Poland during the summer period. Summer, for example, is the period of grain filling, when moderate temperature increases yield growth. In the event of extremely high temperatures, some farmers mitigate climate risk by using irrigation facilities. Potential adaptive behaviors of agricultural enterprises in response to the summer temperature changes, such as reducing risk by increasing the genetic diversity of plants or increasing irrigation investments, thus offsetting the negative impact of rising temperatures [84].

Summarizing the results of models that consider changes in average temperature during specific seasons, it should be noted that plant growth conditions and the specific nature of agricultural activities cause these enterprises to exhibit varying sensitivity to temperature increases. Precisely identification of these characteristics may allow for the intensification of adaptive and protective measures against excessive warming during specific seasons. For agricultural businesses, such a concentration of protective measures can yield better results while incurring lower operating costs.

6. Conclusions

Climate change impacts business operations and households in diverse ways. Temperature increases observed in recent decades have, in most cases, negatively impacted on grain harvests and animal husbandry, as well as public health, working conditions, and employee productivity. Based on a wide range of research on the impact of temperature on the financial situation of enterprises in both the financial and non-financial sectors, this study fills the gap in the economic literature by presenting the results of the research on the impact of temperature increase on the resilience to bankruptcy risk of agricultural enterprises operating in the years 2016–2023, taking into account the temperature and macroeconomic conditions prevailing in the regions of their operation and measuring the resilience to bankruptcy risk using the Altman (Z-score) and Zmijewski (X-score) methods.

Financial data for over four thousand Polish enterprises were obtained from the EMIS database, the data of temperature in regions from the Institute of Meteorology and Water Management (IMGW-PIB), and regional macroeconomic data from the Central Statistical Office (Statistics Poland). The impact of temperature changes on the Z-score and X-score values was examined using fixed-effects panel regression. Research has shown that in all regions of Poland between 2004 and 2023, average annual and quarterly temperatures were characterized by significant variability, with a long-term upward trend. Geographical variation in temperature changes may become the cause of changes in the structure of crops and their sensitivity to temperature increases in Poland, similarly to what was observed in China in the form of shifting rice cultivation to the northern regions [25].

Temperature changes had a significant impact on the resilience of enterprises to bankruptcy risk, and this relationship had a nonlinear, parabolic nature, which is consistent with the results of research conducted for agriculture in China [19,59,60] and the USA [61,62,63]. An increase in the average annual temperature above the long-term temperature (for the X-score, reduced by 0.7 °C) contributes to a decrease in the resilience of agricultural firms to bankruptcy. The nonlinear, parabolic nature of this relationship means that, due to the significance of the temperature factor in the square of the power, an incidental larger temperature spike above the long-term average can significantly impair the stability of agricultural firms. As a result, such a situation can negatively impact the safety of the entire national agricultural sector.

Enterprise resilience to bankruptcy risk is differentially exposed to temperature increases in different calendar seasons, which is consistent with the results of research conducted for agriculture in China [60] and USA [6]. In general, for winter, spring and autumn the investigated relationship has a similar non-linear, parabolic nature, like the relationship considering the average annual temperature. However, differences exist in (i) the temperature thresholds, beyond which further increases impair companies’ resilience, and (ii) the sensitivity of Z-score and X-score indicators to temperature changes. Temperature increases in winter can provide a potential negative impact on company’s resilience may occur after exceeding the long-term temperature plus 3 °C (for the Z-score) or plus 1.4 °C (for the X-score). This excess over the long-term temperature provides some kind of safety buffer for companies. In autumn, however, the deterioration of the resilience of enterprises may occur immediately after exceeding the long-term temperature, and in spring after exceeding the long-term temperature reduced by approximately 1.5 °C

A significant feature of the relationship between risk resilience and temperature changes is its varying sensitivity across seasons. Risk resilience responds most rapidly to temperature changes in winter and autumn, and slightly slower in spring. Summer temperature changes do not have a significant or variable impact on enterprise resilience. The variables characterizing (i) the company (asset value, asset sales efficiency, asset profitability, share of equity, and share of short-term liabilities in the financing structure) and (ii) the region (regional GDP growth rate, GDPpc value, and agricultural production value) also have a positive, statistically significant impact on the resilience of enterprises to bankruptcy risk.

The study’s conclusions may have significant applications in agricultural enterprises’ preparation of contingency plans for potential climate shocks, as well as in public administration institutions’ preparation of programs to protect the agricultural sector from excessive increases in atmospheric temperature, adaptation of agricultural operations to new climatic conditions, and development of plans to ensure food security.

The authors are aware of certain weaknesses in the study. These stem largely from the imperfections of the reporting database for enterprises, particularly small enterprises that use simplified accounting principles. Furthermore, the study’s shortcomings arise from, among other things, uneven time series of variables characterizing the enterprises, as well as significant differences in the size of the enterprises studied. To deepen the research on the impact of temperature changes on the resilience of agricultural enterprises, we plan to expand the geographical scope of the study to include Central and Eastern European countries, and also presenting climate change using the current measure, i.e., the difference from long-term temperature as well as the Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) available on the NSF National Center for Atmospheric Research website (https://ncar.ucar.edu/; accessed on 25 June 2025).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K. and A.W.; Methodology S.K. and A.W.; validation, S.K. and A.W.; Formal analysis, S.K. and A.W.; Investigation, S.K. and A.W.; Data curation, S.K. and A.W.; Writing—original draft preparation, S.K. and A.W.; writing—review and editing, S.K. and A.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

The Z-score distribution after eliminating outliers.

Figure A2.

The X-score distribution after eliminating outliers.

Table A1.

The impact of deviations from the long-term temperature on the resilience of enterprises to the risk of bankruptcy (Z-score).

Table A1.

The impact of deviations from the long-term temperature on the resilience of enterprises to the risk of bankruptcy (Z-score).

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| assets | 0.303 * | 0.274 * | 0.262 | 0.298 * | 0.304 * |

| (0.161) | (0.160) | (0.160) | (0.162) | (0.162) | |

| eff_asset | 0.038 * | 0.039 * | 0.038 * | 0.039 * | 0.039 * |

| (0.020) | (0.020) | (0.020) | (0.020) | (0.020) | |

| roa | 0.040 * | 0.040 * | 0.040 * | 0.040 * | 0.040 * |

| (0.022) | (0.022) | (0.022) | (0.022) | (0.022) | |

| lev | 0.122 | 0.124 | 0.125 | 0.122 | 0.121 |

| (0.087) | (0.087) | (0.087) | (0.087) | (0.087) | |

| short_liab | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| ΔTyr | 0.000 | ||||

| (0.036) | |||||

| ΔTyr2 | −0.049 *** | ||||

| (0.017) | |||||

| ΔTwi | 0.212 *** | ||||

| (0.042) | |||||

| ΔTwi2 | −0.035 *** | ||||

| (0.012) | |||||

| ΔTsp | −0.085 *** | ||||

| (0.022) | |||||

| ΔTsp2 | −0.031 *** | ||||

| (0.007) | |||||

| ΔTsu | 0.069 * | ||||

| (0.036) | |||||

| ΔTsu2 | −0.003 | ||||

| (0.006) | |||||

| ΔTau | −0.018 | ||||

| (0.051) | |||||

| ΔTau2 | −0.098 *** | ||||

| (0.030) | |||||

| cons | 5.366 *** | 5.284 *** | 5.713 *** | 5.288 *** | 5.397 *** |

| (1.007) | (1.012) | (1.005) | (1.011) | (1.009) | |

| Observations | 22,397 | 22,397 | 22,397 | 22,397 | 22,397 |

| Groups | 4555 | 4555 | 4555 | 4555 | 4555 |

| F-stat | 6.925 | 12.729 | 16.134 | 6.421 | 8.810 |

| R-squared | 0.079 | 0.080 | 0.081 | 0.080 | 0.079 |

Note: * p < 0.1, *** p < 0.01; long-term average temperature for 2004–2015. Source: own calculations based on the data of EMIS, IMGW-PIB and Statistics Poland.

Table A2.

The impact of deviations from the long-term temperature on the resilience of enterprises to the risk of bankruptcy (Z-score)—random effects regression model.

Table A2.

The impact of deviations from the long-term temperature on the resilience of enterprises to the risk of bankruptcy (Z-score)—random effects regression model.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| assets | 0.370 *** | 0.357 *** | 0.353 *** | 0.368 *** | 0.371 *** |

| (0.077) | (0.077) | (0.077) | (0.077) | (0.077) | |

| eff_asset | 0.035 * | 0.035 * | 0.034 * | 0.035 * | 0.035 * |

| (0.018) | (0.018) | (0.018) | (0.018) | (0.018) | |

| roa | 0.037 ** | 0.036 ** | 0.036 ** | 0.037 ** | 0.037 ** |

| (0.017) | (0.017) | (0.017) | (0.017) | (0.017) | |

| lev | 0.154 * | 0.156 * | 0.156 * | 0.154 * | 0.154 * |

| (0.081) | (0.081) | (0.080) | (0.081) | (0.081) | |

| short_liab | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| ΔTyr | 0.000 | ||||

| (0.035) | |||||

| ΔTyr2 | −0.050 *** | ||||

| (0.017) | |||||

| ΔTwi | 0.183 *** | ||||

| (0.036) | |||||

| ΔTwi2 | −0.027 ** | ||||

| (0.012) | |||||

| ΔTsp | −0.106 *** | ||||

| (0.021) | |||||

| ΔTsp2 | −0.035 *** | ||||

| (0.007) | |||||

| ΔTsu | 0.066 ** | ||||

| (0.031) | |||||

| ΔTsu2 | −0.004 | ||||

| (0.006) | |||||

| ΔTau | 0.010 | ||||

| (0.060) | |||||

| ΔTau2 | −0.077 ** | ||||

| (0.030) | |||||

| cons | 5.293 *** | 5.154 *** | 5.473 *** | 5.203 *** | 5.321 *** |

| (0.482) | (0.485) | (0.480) | (0.482) | (0.482) | |

| Observations | 22,397 | 22,397 | 22,397 | 22,397 | 22,397 |

| Groups | 4555 | 4555 | 4555 | 4555 | 4555 |

| R-squared | 0.083 | 0.085 | 0.085 | 0.084 | 0.083 |

Note: * p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01; long-term average temperature for 2004–2023. Source: own calculations based on the data of EMIS, IMGW-PIB and Statistics Poland.

Table A3.

The impact of deviations from the long-term temperature on the resilience of enterprises to the risk of bankruptcy (Z-score)—Dynamic model (Arellano–Bond estimator).

Table A3.

The impact of deviations from the long-term temperature on the resilience of enterprises to the risk of bankruptcy (Z-score)—Dynamic model (Arellano–Bond estimator).

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lag_z-score | 0.059 | 0.062 * | 0.082 ** | 0.055 | 0.060 |

| (0.037) | (0.037) | (0.035) | (0.037) | (0.037) | |

| assets | −0.317 | −0.339 * | −0.387 * | −0.352 * | −0.319 |

| (0.202) | (0.202) | (0.204) | (0.204) | (0.201) | |

| eff_asset | −0.000 | 0.000 | −0.001 | −0.001 | −0.000 |

| (0.021) | (0.021) | (0.021) | (0.021) | (0.021) | |

| roa | 0.125 *** | 0.125 *** | 0.126 *** | 0.125 *** | 0.125 *** |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | |

| lev | −0.044 | −0.044 | −0.047 | −0.043 | −0.044 |

| (0.358) | (0.357) | (0.359) | (0.358) | (0.358) | |

| short_liab | −0.001 | −0.001 | −0.001 | −0.001 | −0.001 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| ΔTyr | −0.007 | ||||

| (0.037) | |||||

| ΔTyr2 | −0.027 | ||||

| (0.018) | |||||

| ΔTwi | 0.125 *** | ||||

| (0.032) | |||||

| ΔTwi2 | −0.030 *** | ||||

| (0.010) | |||||

| ΔTsp | −0.129 *** | ||||

| (0.025) | |||||

| ΔTsp2 | −0.011 | ||||

| (0.008) | |||||

| ΔTsu | 0.098 *** | ||||

| (0.035) | |||||

| ΔTsu2 | 0.014 ** | ||||

| (0.006) | |||||

| ΔTau | −0.092 | ||||

| (0.066) | |||||

| ΔTau2 | 0.008 | ||||

| (0.030) | |||||

| cons | 8.668 *** | 8.679 *** | 9.008 *** | 8.788 *** | 8.700 *** |

| (1.353) | (1.355) | (1.370) | (1.364) | (1.351) | |

| Observations | 12,761 | 12,761 | 12,761 | 12,761 | 12,761 |

| Groups | 3478 | 3478 | 3478 | 3478 | 3478 |

Note: * p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01; long-term average temperature for 2004–2023. Source: own calculations based on the data of EMIS, IMGW-PIB and Statistics Poland.

Table A4.

The impact of deviations from the long-term temperature on the resilience to the risk of enterprise bankruptcy (X-score).

Table A4.

The impact of deviations from the long-term temperature on the resilience to the risk of enterprise bankruptcy (X-score).

| (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| assets | −0.005 | 0.001 | 0.008 | −0.002 | −0.007 |

| (0.056) | (0.057) | (0.057) | (0.057) | (0.056) | |

| eff_asset | −1.197 *** | −1.199 *** | −1.198 *** | −1.200 *** | −1.194 *** |

| (0.462) | (0.462) | (0.462) | (0.462) | (0.461) | |

| roa | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| lev | −3.891 *** | −3.886 *** | −3.878 *** | −3.892 *** | −3.887 *** |

| (0.451) | (0.452) | (0.452) | (0.452) | (0.451) | |

| short_liab | −0.000 *** | −0.000 *** | −0.000 *** | −0.000 *** | −0.000 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| ΔTyr | 0.032 *** | ||||

| (0.010) | |||||

| ΔTyr2 | 0.021 *** | ||||

| (0.005) | |||||

| ΔTwi | −0.054 *** | ||||

| (0.014) | |||||

| ΔTwi2 | 0.017 *** | ||||

| (0.004) | |||||

| ΔTsp | 0.012 * | ||||

| (0.007) | |||||

| ΔTsp2 | 0.006 *** | ||||

| (0.002) | |||||

| ΔTsu | 0.009 | ||||

| (0.010) | |||||

| ΔTsu2 | 0.004 ** | ||||

| (0.002) | |||||

| ΔTau | 0.035 *** | ||||

| (0.014) | |||||

| ΔTau2 | 0.035 *** | ||||

| (0.008) | |||||

| cons | −0.955 | −0.922 | −1.011 | −0.908 | −0.939 |

| (0.718) | (0.717) | (0.731) | (0.716) | (0.716) | |

| Observations | 17,486 | 17,486 | 17,486 | 17,486 | 17,486 |

| Groups | 3565 | 3565 | 3565 | 3565 | 3565 |

| F-stat | 27.963 | 31.242 | 38.575 | 20.763 | 41.281 |

| R-squared | 0.692 | 0.692 | 0.691 | 0.692 | 0.691 |

Note: * p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01; long-term average temperature for 2004–2015, negative X-score values indicate a good financial situation for the company. Source: own calculations based on the data of EMIS, IMGW-PIB and Statistics Poland.

Table A5.

The impact of deviations from the long-term temperature on the resilience to the risk of enterprise bankruptcy (X-score)—random effects regression model.

Table A5.

The impact of deviations from the long-term temperature on the resilience to the risk of enterprise bankruptcy (X-score)—random effects regression model.

| (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| assets | −0.114 *** | −0.113 *** | −0.111 *** | −0.113 *** | −0.114 *** |

| (0.017) | (0.017) | (0.017) | (0.017) | (0.017) | |

| eff_asset | −1.545 *** | −1.550 *** | −1.549 *** | −1.548 *** | −1.543 *** |

| (0.518) | (0.518) | (0.518) | (0.518) | (0.518) | |

| roa | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| lev | −4.330 *** | −4.329 *** | −4.325 *** | −4.332 *** | −4.327 *** |

| (0.349) | (0.349) | (0.349) | (0.349) | (0.349) | |

| short_liab | −0.000 *** | −0.000 *** | −0.000 *** | −0.000 *** | −0.000 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| ΔTyr | 0.039 *** | ||||

| (0.010) | |||||

| ΔTyr2 | 0.019 *** | ||||

| (0.005) | |||||

| ΔTwi | −0.045 *** | ||||

| (0.012) | |||||

| ΔTwi2 | 0.016 *** | ||||

| (0.004) | |||||

| ΔTsp | 0.022 *** | ||||

| (0.007) | |||||

| ΔTsp2 | 0.005 *** | ||||

| (0.002) | |||||

| ΔTsu | 0.018 ** | ||||

| (0.008) | |||||

| ΔTsu2 | 0.004 *** | ||||

| (0.001) | |||||

| ΔTau | 0.025 * | ||||

| (0.015) | |||||

| ΔTau2 | 0.024 *** | ||||

| (0.008) | |||||

| cons | 0.219 | 0.270 | 0.234 | 0.263 | 0.223 |

| (0.446) | (0.439) | (0.445) | (0.440) | (0.447) | |

| Observations | 17,486 | 17,486 | 17,486 | 17,486 | 17,486 |

| Groups | 3565 | 3565 | 3565 | 3565 | 3565 |

| F-stat | 28.913 | 29.495 | 38.762 | 20.821 | 41.298 |

| R-squared | 0.692 | 0.692 | 0.691 | 0.692 | 0.691 |

Note: * p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01; long-term average temperature for 2004–2023, negative X-score values indicate a good financial situation for the company. Source: own calculations based on the data of EMIS, IMGW-PIB and Statistics Poland.

Table A6.

The impact of deviations from the long-term temperature on the resilience to the risk of enterprise bankruptcy (X-score)—Dynamic model (Arellano–Bond estimator).

Table A6.

The impact of deviations from the long-term temperature on the resilience to the risk of enterprise bankruptcy (X-score)—Dynamic model (Arellano–Bond estimator).

| (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lag_x-score | 0.170 *** | 0.118 ** | 0.113 ** | 0.124 *** | 0.157 *** |

| (0.054) | (0.049) | (0.045) | (0.047) | (0.052) | |

| assets | 0.145 | 0.132 | 0.148 | 0.117 | 0.146 |

| (0.093) | (0.092) | (0.093) | (0.096) | (0.093) | |

| eff_asset | −1.974 *** | −1.961 *** | −1.969 *** | −1.968 *** | −1.967 *** |

| (0.319) | (0.314) | (0.316) | (0.314) | (0.318) | |

| roa | −0.002 | −0.002 | −0.002 | −0.002 | −0.002 |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| lev | −3.956 *** | −3.957 *** | −3.957 *** | −3.976 *** | −3.953 *** |

| (0.599) | (0.598) | (0.599) | (0.599) | (0.598) | |

| short_liab | −0.000 | −0.001 | −0.001 | −0.001 | −0.000 |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| ΔTyr | 0.061 *** | ||||

| (0.016) | |||||

| ΔTyr2 | 0.024 *** | ||||

| (0.007) | |||||

| ΔTwi | −0.019 * | ||||

| (0.011) | |||||

| ΔTwi2 | 0.016 *** | ||||

| (0.004) | |||||

| ΔTsp | 0.006 | ||||

| (0.007) | |||||

| ΔTsp2 | 0.001 | ||||

| (0.002) | |||||

| ΔTsu | 0.060 *** | ||||

| (0.017) | |||||

| ΔTsu2 | 0.008 *** | ||||

| (0.003) | |||||

| ΔTau | 0.053 ** | ||||

| (0.021) | |||||

| ΔTau2 | 0.015 | ||||

| (0.009) | |||||

| cons | −0.964 | −1.014 | −1.099 | −0.878 | −1.000 |

| (0.814) | (0.810) | (0.813) | (0.822) | (0.811) | |

| Observations | 10,011 | 10,011 | 10,011 | 10,011 | 10,011 |

| Groups | 2685 | 2685 | 2685 | 2685 | 2685 |

Note: * p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01; long-term average temperature for 2004–2023, negative X-score values indicate a good financial situation for the company. Source: own calculations based on the data of EMIS, IMGW-PIB and Statistics Poland.

Table A7.

The impact of deviations from the long-term temperature on the resilience to the risk of enterprise bankruptcy (Z-score)—large enterprises.

Table A7.

The impact of deviations from the long-term temperature on the resilience to the risk of enterprise bankruptcy (Z-score)—large enterprises.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| log_asset | −0.330 | −0.404 * | −0.412 * | −0.369 | −0.321 |

| (0.234) | (0.234) | (0.233) | (0.235) | (0.235) | |

| eff_asset | 0.108 | 0.109 | 0.081 | 0.106 | 0.098 |

| (0.149) | (0.148) | (0.145) | (0.150) | (0.149) | |

| roa | 0.127 *** | 0.127 *** | 0.126 *** | 0.128 *** | 0.127 *** |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | |

| lev | 4.060 ** | 4.043 ** | 4.043 ** | 4.047 ** | 4.066 ** |

| (2.033) | (2.011) | (2.010) | (2.025) | (2.035) | |

| st_lt_liab | 0.009 ** | 0.008 ** | 0.008 ** | 0.009 ** | 0.009 ** |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| long_temp_diff_av | 0.063 * | ||||

| (0.034) | |||||

| tempdiff2 | −0.027 * | ||||

| (0.015) | |||||

| temp_diff_winter | 0.233 *** | ||||

| (0.045) | |||||

| temp_diff_winter2 | −0.034 *** | ||||

| (0.013) | |||||

| temp_diff_spring | −0.126 *** | ||||

| (0.023) | |||||

| temp_diff_spring2 | −0.038 *** | ||||

| (0.007) | |||||

| temp_diff_summer | 0.148 *** | ||||

| (0.032) | |||||

| temp_diff_summer2 | 0.008 | ||||

| (0.005) | |||||

| temp_diff_autumn | 0.025 | ||||

| (0.062) | |||||

| temp_diff_autumn2 | −0.057 * | ||||

| (0.031) | |||||

| _cons | 7.663 *** | 8.103 *** | 8.555 *** | 7.896 *** | 7.683 *** |

| (2.028) | (2.038) | (2.056) | (2.037) | (2.034) | |

| Observations | 12,371 | 12,371 | 12,371 | 12,371 | 12,371 |

| Groups | 2440 | 2440 | 2440 | 2440 | 2440 |

| F-stat | 145.286 | 166.480 | 182.244 | 142.561 | 144.205 |

| R-squared | 0.378 | 0.376 | 0.375 | 0.377 | 0.378 |

Note: * p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01; long-term average temperature for 2004–2023. Source: own calculations based on the data of EMIS, IMGW-PIB and Statistics Poland.

Table A8.

The impact of deviations from the long-term temperature on the resilience to the risk of enterprise bankruptcy (Z-score)—medium-sized enterprises.

Table A8.

The impact of deviations from the long-term temperature on the resilience to the risk of enterprise bankruptcy (Z-score)—medium-sized enterprises.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| log_asset | −1.096 *** | −1.117 *** | −1.105 *** | −1.101 *** | −1.091 *** |

| (0.243) | (0.243) | (0.244) | (0.243) | (0.243) | |

| eff_asset | −0.020 | −0.018 | −0.019 | −0.022 | −0.021 |

| (0.031) | (0.030) | (0.030) | (0.031) | (0.031) | |

| roa | 0.113 *** | 0.113 *** | 0.113 *** | 0.113 *** | 0.113 *** |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | |

| lev | 5.696 *** | 5.698 *** | 5.689 *** | 5.694 *** | 5.692 *** |

| (1.171) | (1.171) | (1.170) | (1.171) | (1.171) | |

| st_lt_liab | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| long_temp_diff_av | 0.078 | ||||

| (0.051) | |||||

| tempdiff2 | 0.020 | ||||

| (0.025) | |||||

| temp_diff_winter | 0.051 | ||||

| (0.052) | |||||

| temp_diff_winter2 | 0.014 | ||||

| (0.018) | |||||

| temp_diff_spring | −0.048 | ||||

| (0.029) | |||||

| temp_diff_spring2 | −0.006 | ||||

| (0.009) | |||||

| temp_diff_summer | 0.126 ** | ||||

| (0.049) | |||||

| temp_diff_summer2 | 0.015 * | ||||

| (0.009) | |||||

| temp_diff_autumn | 0.067 | ||||

| (0.082) | |||||

| temp_diff_autumn2 | −0.028 | ||||

| (0.045) | |||||

| _cons | 10.722 *** | 10.801 *** | 10.908 *** | 10.757 *** | 10.776 *** |

| (1.393) | (1.387) | (1.399) | (1.387) | (1.387) | |

| Observations | 7283 | 7283 | 7283 | 7283 | 7283 |

| Groups | 1967 | 1967 | 1967 | 1967 | 1967 |

| F-stat | 134.234 | 141.179 | 134.341 | 134.198 | 135.002 |

| R-squared | 0.362 | 0.362 | 0.362 | 0.362 | 0.362 |

Note: * p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01; long-term average temperature for 2004–2023. Source: own calculations based on the data of EMIS, IMGW-PIB and Statistics Poland.

Table A9.

The impact of deviations from the long-term temperature on the resilience to the risk of enterprise bankruptcy (Z-score)—small enterprises.

Table A9.

The impact of deviations from the long-term temperature on the resilience to the risk of enterprise bankruptcy (Z-score)—small enterprises.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| log_asset | 1.005 | 0.992 | 0.985 | 0.995 | 1.013 |

| (0.692) | (0.696) | (0.694) | (0.692) | (0.691) | |

| eff_asset | 0.020 | 0.021 | 0.021 | 0.021 | 0.022 |

| (0.021) | (0.021) | (0.021) | (0.021) | (0.021) | |

| roa | 0.068 *** | 0.068 *** | 0.067 *** | 0.067 *** | 0.068 *** |

| (0.016) | (0.016) | (0.016) | (0.016) | (0.016) | |

| lev | 0.298 * | 0.291 * | 0.299 * | 0.295 * | 0.300 * |

| (0.176) | (0.176) | (0.177) | (0.177) | (0.176) | |

| st_lt_liab | −0.006 | −0.005 | −0.005 | −0.005 | −0.005 |

| (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | |

| long_temp_diff_av | −0.211 | ||||

| (0.191) | |||||

| tempdiff2 | −0.222 ** | ||||

| (0.106) | |||||

| temp_diff_winter | 0.031 | ||||

| (0.136) | |||||

| temp_diff_winter2 | −0.053 | ||||

| (0.046) | |||||

| temp_diff_spring | −0.015 | ||||

| (0.115) | |||||

| temp_diff_spring2 | −0.018 | ||||

| (0.043) | |||||

| temp_diff_summer | −0.107 | ||||

| (0.126) | |||||

| temp_diff_summer2 | −0.043 | ||||

| (0.032) | |||||

| temp_diff_autumn | −0.033 | ||||

| (0.342) | |||||

| temp_diff_autumn2 | −0.186 | ||||

| (0.156) | |||||

| _cons | 4.460 ** | 4.147 ** | 4.002 ** | 4.094 ** | 4.195 ** |

| (1.791) | (1.773) | (1.763) | (1.759) | (1.735) | |

| Observations | 2743 | 2743 | 2743 | 2743 | 2743 |

| Groups | 967 | 967 | 967 | 967 | 967 |

| F-stat | 14.127 | 11.577 | 11.563 | 12.046 | 14.350 |

| R-squared | 0.060 | 0.060 | 0.061 | 0.061 | 0.060 |

Note: * p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01; long-term average temperature for 2004–2023. Source: own calculations based on the data of EMIS, IMGW-PIB and Statistics Poland.

Table A10.

The impact of deviations from the long-term temperature on the resilience to the risk of enterprise bankruptcy (X-score)—large enterprises.

Table A10.

The impact of deviations from the long-term temperature on the resilience to the risk of enterprise bankruptcy (X-score)—large enterprises.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| log_asset | −0.043 | −0.032 | −0.028 | −0.041 | −0.043 |

| (0.057) | (0.056) | (0.056) | (0.057) | (0.057) | |

| eff_asset | −3.514 *** | −3.516 *** | −3.508 *** | −3.518 *** | −3.510 *** |

| (0.228) | (0.228) | (0.228) | (0.228) | (0.230) | |

| roa | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| lev | −4.007 *** | −3.992 *** | −3.983 *** | −4.005 *** | −4.008 *** |

| (0.645) | (0.649) | (0.648) | (0.646) | (0.645) | |

| st_lt_liab | −0.000 *** | −0.000 *** | −0.000 *** | −0.000 *** | −0.000 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| long_temp_diff_avg | 0.004 | ||||

| (0.007) | |||||

| tempdiff2 | 0.011 *** | ||||

| (0.004) | |||||

| temp_diff_winter | −0.028 * | ||||

| (0.015) | |||||

| temp_diff_winter2 | 0.006 * | ||||

| (0.003) | |||||

| temp_diff_spring | 0.014 * | ||||

| (0.007) | |||||

| temp_diff_spring2 | 0.005 ** | ||||

| (0.002) | |||||

| temp_diff_summer | −0.002 | ||||

| (0.006) | |||||

| temp_diff_summer2 | 0.002 | ||||

| (0.001) | |||||

| temp_diff_autumn | −0.008 | ||||

| (0.012) | |||||

| temp_diff_autumn2 | 0.019 *** | ||||

| (0.006) | |||||

| _cons | 0.474 | 0.416 | 0.336 | 0.480 | 0.470 |

| (0.564) | (0.579) | (0.593) | (0.568) | (0.563) | |

| Observations | 11,463 | 11,463 | 11,463 | 11,463 | 11,463 |

| Groups | 2239 | 2239 | 2239 | 2239 | 2239 |

| F-stat | 71.443 | 142.869 | 153.948 | 70.755 | 101.442 |

| R-squared | 0.924 | 0.924 | 0.924 | 0.924 | 0.924 |

Note: * p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01; long-term average temperature for 2004–2023, negative X-score values indicate a good financial situation for the company. Source: own calculations based on the data of EMIS, IMGW-PIB and Statistics Poland.

Table A11.

The impact of deviations from the long-term temperature on the resilience to the risk of enterprise bankruptcy (X-score)—medium-sized enterprises.

Table A11.

The impact of deviations from the long-term temperature on the resilience to the risk of enterprise bankruptcy (X-score)—medium-sized enterprises.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| log_asset | −0.256 *** | −0.258 *** | −0.255 *** | −0.256 *** | −0.256 *** |

| (0.079) | (0.078) | (0.079) | (0.079) | (0.079) | |

| eff_asset | −2.962 *** | −2.963 *** | −2.964 *** | −2.964 *** | −2.959 *** |

| (0.305) | (0.305) | (0.305) | (0.305) | (0.305) | |

| roa | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| lev | −4.890 *** | −4.884 *** | −4.890 *** | −4.893 *** | −4.889 *** |

| (0.307) | (0.306) | (0.307) | (0.309) | (0.306) | |

| st_lt_liab | −0.000 *** | −0.000 *** | −0.000 *** | −0.000 *** | −0.000 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| long_temp_diff_avg | 0.012 | ||||

| (0.017) | |||||

| tempdiff2 | 0.012 | ||||

| (0.010) | |||||

| temp_diff_winter | −0.038 *** | ||||

| (0.013) | |||||

| temp_diff_winter2 | 0.017 *** | ||||

| (0.005) | |||||

| temp_diff_spring | −0.004 | ||||

| (0.009) | |||||

| temp_diff_spring2 | 0.002 | ||||

| (0.003) | |||||

| temp_diff_summer | 0.016 | ||||

| (0.015) | |||||

| temp_diff_summer2 | 0.004 | ||||

| (0.003) | |||||

| temp_diff_autumn | −0.024 | ||||

| (0.026) | |||||

| temp_diff_autumn2 | 0.035 | ||||

| (0.033) | |||||

| _cons | 2.116 *** | 2.133 *** | 2.135 *** | 2.132 *** | 2.112 *** |

| (0.573) | (0.569) | (0.566) | (0.571) | (0.572) | |

| Observations | 4984 | 4984 | 4984 | 4984 | 4984 |

| Groups | 1408 | 1408 | 1408 | 1408 | 1408 |

| F-stat | 83.423 | 97.154 | 84.913 | 85.567 | 89.156 |

| R-squared | 0.858 | 0.858 | 0.858 | 0.858 | 0.858 |

Note: *** p < 0.01; long-term average temperature for 2004–2023, negative X-score values indicate a good financial situation for the company. Source: own calculations based on the data of EMIS, IMGW-PIB and Statistics Poland.

Table A12.

The impact of deviations from the long-term temperature on the resilience to the risk of enterprise bankruptcy (X-score)—small enterprises.

Table A12.

The impact of deviations from the long-term temperature on the resilience to the risk of enterprise bankruptcy (X-score)—small enterprises.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| log_asset | −0.431 | −0.434 | −0.414 | −0.428 | −0.443 |

| (0.289) | (0.294) | (0.297) | (0.294) | (0.289) | |

| eff_asset | −0.271 * | −0.273 * | −0.272 * | −0.273 * | −0.270 * |

| (0.163) | (0.163) | (0.163) | (0.164) | (0.163) | |

| roa | −0.003 | −0.003 | −0.003 | −0.003 | −0.003 |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| lev | −1.479 | −1.472 | −1.502 | −1.493 | −1.487 |

| (1.522) | (1.517) | (1.515) | (1.516) | (1.529) | |

| st_lt_liab | −0.001 | −0.001 | −0.002 | −0.002 | −0.001 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| long_temp_diff_avg | 0.220 ** | ||||

| (0.195) | |||||

| tempdiff2 | 0.055 * | ||||

| (0.031) | |||||

| temp_diff_winter | 0.000 | ||||

| (0.087) | |||||

| temp_diff_winter2 | 0.030 | ||||

| (0.027) | |||||

| temp_diff_spring | 0.049 | ||||

| (0.059) | |||||

| temp_diff_spring2 | −0.027 | ||||

| (0.021) | |||||

| temp_diff_summer | 0.074 | ||||

| (0.072) | |||||

| temp_diff_summer2 | −0.012 | ||||

| (0.017) | |||||

| temp_diff_autumn | 0.172 | ||||

| (0.192) | |||||

| temp_diff_autumn2 | 0.126 * | ||||

| (0.071) | |||||

| _cons | −0.444 | −0.389 | −0.235 | −0.259 | −0.444 |

| (0.827) | (0.844) | (0.842) | (0.830) | (0.820) | |

| Observations | 1038 | 1038 | 1038 | 1038 | 1038 |

| Groups | 434 | 434 | 434 | 434 | 434 |

| F-stat | 3.590 | 2.987 | 2.375 | 2.353 | 3.909 |

| R-squared | 0.294 | 0.295 | 0.296 | 0.296 | 0.293 |

Note: * p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05; long-term average temperature for 2004–2023, negative X-score values indicate a good financial situation for the company. Source: own calculations based on the data of EMIS, IMGW-PIB and Statistics Poland.

References