Abstract

Earth–Air Heat Exchangers (EAHEs) exploit stable subsurface temperatures to pre-condition supply air. To address limitations of conventional systems in hot–arid climates, this study investigates the performance of a hybrid EAHE prototype combining a serpentine subsurface pipe with a buried water tank. Installed in a residential building in Lichana, Biskra (Algeria), the system was designed to enhance land compactness, thermal stability, and soil–water heat harvesting. Experimental monitoring was conducted across 13 intervals strategically spanning seasonal transitions and extremes and was complemented by calibrated numerical simulations. From over 30,000 data points, outlet trajectories, thermal efficiency, Coefficient of Performance (COP), and energy savings were assessed against a straight-pipe baseline. Results showed that the hybrid EAHE delivered smoother outlet profiles under moderate gradients while the baseline achieved larger instantaneous ΔT. Thermal efficiencies exceeded 90% during high-gradient episodes and averaged above 70% annually. COP values scaled with the inlet–soil gradient, ranging from 1.5 to 4.0. Cumulative recovered energy reached 80.6 kWh (3.92 kWh/day), while the heat pump electricity referred to a temperature-dependent ASHP totaled 34.59 kWh (1.40 kWh/day). Accounting for the EAHE fan yields a net saving of 25.46 kWh across the campaign, only one interval (5) was net-negative, underscoring the value of bypass/fan shut-off under weak gradients. Overall, the hybrid EAHE emerges as a footprint-efficient option for arid housing, provided operation is dynamically controlled. Future work will focus on controlling logic and soil–moisture interactions to maximize net performance.

1. Introduction

Global energy systems face mounting challenges due to escalating demand, particularly in sectors reliant on thermal regulation. Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems currently account for 7% of global electricity consumption, contributing nearly 1 billion tons of CO2 emissions annually [1]. These statistics highlight the growing dependence on energy-intensive technologies, particularly for cooling, which is projected to intensify as global temperatures continue to rise [2]. Against this backdrop, efforts to develop climate-responsive and energy-efficient technologies have become increasingly urgent [3]. Reviews of Earth–Air Heat Exchanger (EAHE) systems emphasize their potential to reduce both energy use and operational costs across diverse climates, with energy savings exceeding 50% in specific applications [4,5].

This imperative is particularly critical in regions such as North Africa, where prolonged hot seasons, high solar radiation, and rising urbanization have significantly increased energy demand for space cooling. Countries in this region face structural vulnerabilities in balancing electricity supply with surging cooling loads. Within this context, Algeria presents a compelling case: its residential sector alone consumes 38% of the country’s total electricity, with a significant portion allocated to space cooling during extended summer heatwaves [6,7]. The country’s heavy reliance on natural gas, which comprises 67% of its energy profile, not only exposes vulnerabilities in its energy security but also underscores the necessity of adopting renewable and low-energy alternatives to alleviate dependency and environmental stress [7]. The burden placed on energy infrastructures, especially in arid and semi-arid regions, amplifies these pressures, pushing energy systems to operate under increasingly demanding conditions [8]. Studies specific to the region confirm the viability of standalone EAHE systems in coping with such stressors, achieving significant temperature modulation even without mechanical aids [9].

While policy frameworks such as Sustainable Development Goal 7 (SDG 7) advocate for affordable, reliable, and sustainable energy access, translating such goals into actionable solutions remains challenging. Algeria’s Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Development Plan (2015–2030) seeks to address these gaps by targeting 22,000 MW of renewable capacity by 2030, promoting the adoption of energy-efficient building technologies [10]. However, despite these efforts, the implementation of technical solutions at the building scale remains limited, necessitating research into passive cooling approaches that align with the region’s environmental context.

Among existing technologies, Earth–Air Heat Exchanger (EAHE) systems have emerged as promising passive heating and cooling solutions. These systems harness subsurface thermal stability to regulate indoor temperatures through a network of buried pipes, achieving energy savings of up to 63% compared to conventional HVAC systems [11]. Their reliance on natural thermal gradients rather than mechanical systems makes them ideal for off-grid applications, offering resilience and sustainability. Modeling efforts in arid climates have confirmed energy savings of over 60%, even under constrained soil and climatic conditions [12]. However, EAHE systems are sensitive to soil composition, thermal conductivity, and moisture levels, which can fluctuate significantly in arid environments [13].

Recent studies have revealed that thermal conductivity may decrease in dry soils compared to moist ones, resulting in reduced cooling efficiency [8]. Additionally, concerns over pressure losses, material degradation, and long-term performance variability necessitate integrating thermal buffering strategies [14]. To address the performance limitations of standalone EAHE systems, especially in arid climates where soil moisture and thermal conductivity vary, recent studies have proposed hybrid configurations that integrate thermal storage and complementary systems. One prominent approach involves coupling EAHEs with water reservoirs or tanks, leveraging water’s high specific heat capacity to buffer temperature fluctuations. Recent hybrid-cooling evaluations report that EAHE–air-source heat pump integrations yield ~9.6–13.8% annual cooling energy savings in warm U.S. climates, highlighting the value of preconditioning the air stream before the heat pump stage [15]. In parallel, experimental work shows that combining evaporative and groundwater-to-air cooling can reduce PV panel temperature sufficiently to increase electrical efficiency by approximately 12.7%, underscoring the broader promise of hybrid architectures for hot-arid regions [16]. Experimental studies confirm that such integration can reduce outlet air temperatures by up to 14.2 °C in summer and improve dehumidification by 36.2% [3]. This hybrid EAHE–heat pump system achieved up to 51% energy savings and nearly doubled the coefficient of performance (COP) of the air-source heat pump coupled with the EAHE during summer and winter operation.

Another innovative configuration combines EAHEs with evaporative cooling channels, where pre-cooled air is conditioned using sprayed water. This technique enables air temperature reductions below ambient wet-bulb temperatures, delivering cooling effectiveness exceeding 100% and making it highly viable in dry, hot climates [17]. Comparative research further highlights the role of underground thermal storage systems in enhancing EAHE effectiveness. Experimental comparisons between EAHEs and subterranean tanks show that underground tanks maintain lower outlet air temperatures and more consistent thermal outputs, especially under dry conditions [18].

Despite these advances, reviews of hybrid EAHE applications emphasize a continued gap in field data, particularly under dynamic environmental and climatic contexts [15]. This lack of empirical validation limits confidence in existing models and hinders the practical adoption of hybrid systems in real-world settings. There is also growing interest in compact hybrid designs for urban integration, such as serpentine layouts combined with small water tanks or phase change materials (PCMs), which aim to balance land-use constraints with thermal performance [19]. In recognition of these challenges, the Algerian National Research Program (PNR) has prioritized applied research that promotes renewable energies towards bridging simulation and experimentation in passive cooling technologies.

Within this framework, an experimental hybrid EAHE is investigated, combining a serpentine subsurface layout with an embedded underground water tank. The serpentine was employed to increase soil contact at multiple depths while reducing the required footprint relative to conventional straight runs; the tank was incorporated to provide passive thermal buffering that smooths diurnal and seasonal temperature swings. The prototype is tested under real, dynamic environmental conditions and benchmarked against a straight-pipe baseline scenario to assess feasibility, outlet-temperature stability, and efficiency in a hot-arid climate. This configuration directly addresses footprint and stability constraints often associated with traditional EAHEs, without additional active equipment.

2. Methodology

As previously introduced, this study focuses on developing and validating a hybrid Earth-Air Heat Exchanger (EAHE) system designed to address the thermal regulation challenges of arid climates. The proposed system integrates an underground water tank as a thermal buffer with a serpentine layout, offering a compact and scalable solution to improve energy efficiency and thermal stability in land-constrained environments.

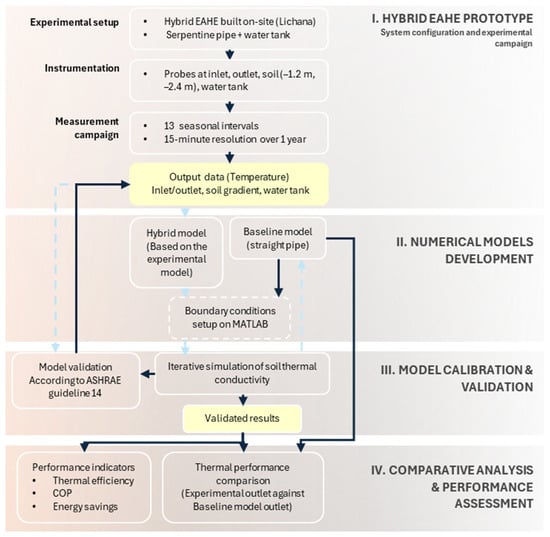

Building upon this framework, the methodology combines numerical modeling with experimental monitoring, enabling the validation of the proposed experimental hybrid EAHE configuration and its comparative assessment against a conventional design. The process follows a structured and interdependent sequence, introduced here and developed in more detail in the subsequent sections. The logic of the whole workflow is illustrated in Figure 1 and comprises the following stages:

Figure 1.

Methodology flowchart.

- 1.

- Experimental setup: covers the on-site construction and monitoring of the serpentine EAHE system, integrated with a subsurface water tank. The system was tested under real boundary conditions representative of a hot arid climate, and the instrumentation protocol was designed to capture air and soil thermal responses over selected periods (Section 2.2).

- 2.

- Numerical model development involves the construction of two transient heat transfer models in MATLAB R2024b: one reproducing the experimental hybrid configuration and the other representing a simplified conventional baseline model EAHE used as a reference. Both models are designed to operate under identical climatic and geometric inputs (Section 3).

- 3.

- Model calibration and validation focus on tuning the numerical model parameters, primarily the soil thermal conductivity and initial temperature field, using a selected subset of the experimental data.

- 4.

- Comparative analysis and performance assessment apply the experimental hybrid device and the numerical baseline model to representative scenarios under the same operating conditions to quantify the impact of the tank integration and pipe layout on efficiency. For the performance assessment, thermal efficiency, Coefficient of Performance (COP), and energy-saving potential are addressed.

2.1. Experimental Setup and Data Acquisition

2.1.1. Site and Climate

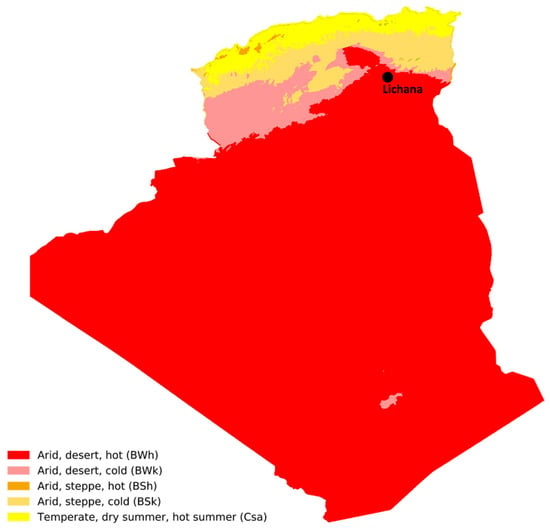

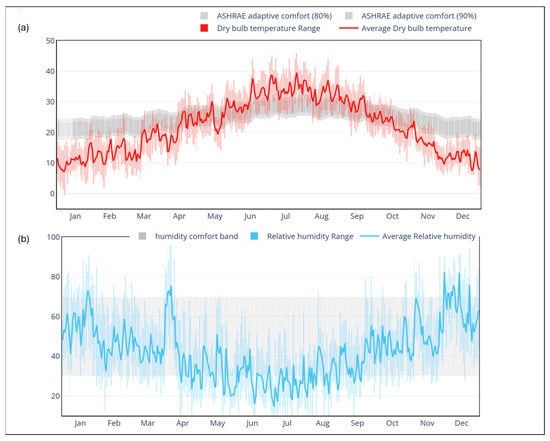

The experimental installation was implemented at a residential building in Lichana, in the Wilaya of Biskra in Algeria, deliberately selected for its representative hot arid climate. Figure 2 situates Lichana within the Köppen–Geiger climate map of Algeria (classification BWh), illustrating the broader climatic context. Lichana’s (Biskra) climate is characterized by extreme daytime heat and sharp nighttime cooling, with summer air temperatures frequently exceeding 45 °C and soil surface temperatures above 50 °C. In winter, nocturnal air temperatures can drop below 5 °C, producing steep diurnal thermal oscillations. The region’s low average humidity (often <20%) further reduces soil thermal conductivity, exacerbating temperature fluctuations. Figure 3, obtained through the CBE Clima tool (Berkley) [20] utilizing a TMY weather file of Biskra city, illustrates the typical diurnal air temperature variability at the site and seasonal humidity trends.

Figure 2.

The geographical location of the experimental site (Lichana, Biskra) is overlaid on Algeria’s Köppen–Geiger climate classification map.

Figure 3.

(a) Dry bulb temperature variation in Biskra (°C); (b) Relative humidity variation in Biskra (%) [20].

Such climatic conditions impose a challenging thermal environment analogous to those in arid regions globally, where passive cooling strategies are most needed.

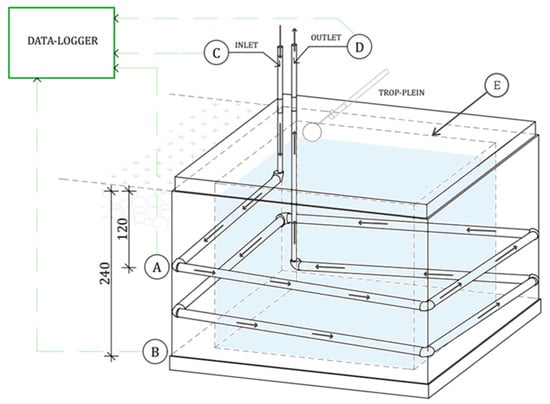

2.1.2. System Configuration

The hybrid EAHE system under study, constructed by LARGHYDE Laboratory, consists of a network of buried PVC pipes arranged in a compact serpentine loop around an underground water tank. Figure 4 illustrates the system schematic, showing eight horizontal pipe segments arranged peripherally around the rectangular water tank to form a continuous heat exchange loop. The pipes have an inner diameter of about 110 mm, a thickness of 5 mm and total length of 27 m and are buried from 1.2 m down to 2.4 m depth in the soil. The horizontal spacing between adjacent pipe runs is 0.50 m, and a soil gap of approximately 0.05 m is maintained between the tank wall and the nearest pipe.

Figure 4.

Schematic of the hybrid Earth–Air Heat Exchanger (EAHE) system installed in Lichana, Biskra, showing the serpentine pipe layout and integrated underground water tank (E). Temperature probes are located at A (−1.2 m soil depth), B (−2.4 m), C (air inlet), and D (air outlet), all connected to a central data logger for continuous thermal monitoring.

Notably, as described in Figure 4, the pipeline is installed with a gentle slope of 10% along its length to allow gravity drainage of condensate water flowing towards a condensate drain (presented in Figure 5b). This prevents moisture accumulation inside the pipes during cooling.

Figure 5.

Photographic view of the installed EAHE system on site. (a) Pipeline within the gypsum soil. (b) Condensate drainage system.

This multi-depth serpentine layout maximizes contact with cooler subsoil layers while significantly reducing the land area required compared to a traditional long straight run, an important factor for compact installations. The chosen pipe diameter and layout also help enhance convective heat transfer and maintain manageable pressure drops, in line with design recommendations for EAHE systems [21]. The underground 3.2 m × 2.6 m water tank, built of reinforced concrete (15 cm thick, lined with 15 cm brick) with an approximate volume of 20 m3, is buried centrally at 2.4 m depth.

The tank’s presence is justified by its ability to introduce a large thermal mass in direct contact with the surrounding soil and adjacent pipes. In detail, by virtue of water’s high specific heat, the tank acts as a thermal buffer that absorbs and releases heat slowly, smoothing out temperature fluctuations in the soil around the pipes. To reach such an effect, the tank remains filled with water (sealed with no active water flow or phase change), so that it acts as a passive thermal battery. Figure 5 shows a photograph of the installed experimental hybrid EAHE device on site, including the buried water tank and the coiled piping network prior to the backfilling phase; subsequent installation stages could not be documented due to the physical inaccessibility of the buried system.

Beyond its thermal function, including such a tank is also consistent with construction practices widely adopted in the Algerian context, where masonry or prefabricated water tanks are commonly integrated into building infrastructure. Their availability, low material and labor costs, and ease of implementation make this configuration particularly practical and economically viable for local applications.

A centrifugal fan (Inline blower), model Soler & Palau TD-MIXVENT TD800/200 N 3V (Barcelona, Spain), was used to maintain a constant airflow speed of 2.5 m/s through the buried pipes (85 m3/h volumetric flow rate) drawing 74 W. This ensured fully turbulent airflow for enhanced convective heat transfer while remaining within typical operational ranges for EAHE fans.

2.2. Instrumentation and Monitoring Protocol

The EAHE system was instrumented to track temperature at key points and to facilitate data collection for model validation. A total of six platinum resistance temperature sensors (PT100) (accuracy ±0.1 °C factory calibrated prior to burial) were installed: at the pipe inlet (ambient air entry), the pipe outlet (air exit into the building), inside the water tank, and two soil depths (−1.2 m and −2.4 m from the surface) near the pipes. These sensor locations provide a comprehensive thermal profile of the system, capturing the air temperature drop along the EAHE and the tank and soil temperature conditions. An additional ambient air sensor measures outdoor air temperature, serving as the EAHE inlet condition. The soil moisture conditions were also monitored qualitatively using probes in the vicinity of the pipes, since moisture variations can affect soil thermal conductivity [22,23]. All sensors were interfaced with a data acquisition system consisting of a National Instruments CompactDAQ-9188 chassis and National Instruments LabVIEW SignalExpress 2012 software for real-time logging.

Temperature readings were recorded at 15-min intervals throughout discontinuous monitoring windows distributed across a one-year campaign. As summarized in Table 1, the dataset is divided into 13 sequential intervals to capture seasonal dynamics. During this time, the system operated continuously, allowing evaluation of the EAHE’s performance under naturally fluctuating ambient conditions. In detail, the one-year record was partitioned into 13 contiguous monitoring windows according to three criteria: (i) continuous operation of the EAHE at the fixed fan setpoint with the full sensor suite active; (ii) predominance of a non-negligible inlet–soil temperature gradient ∣Tin – Tsoil∣ to ensure a discernible exchanger signal; and (iii) collective coverage of winter peaks, shoulder seasons, and summer peaks. By this screening, extended neutral periods were excluded to avoid diluting efficiency and COP estimates and redundant results, while sufficient 15-min samples were retained for stable statistics within each regime. The resulting set provides internally consistent windows that are mutually comparable across the year.

Table 1.

Measurement campaign and simulation periods (start and end times) and mean inlet temperature.

The interval structure is adopted to give comparable weight to the distinct operating regimes encountered across the year (winter heating peaks, shoulder seasons, and summer cooling peaks) and to avoid diluting the exchanger’s signal with long neutral periods where the inlet–soil gradient is small. Each interval is a contiguous block of continuous operation with identical airflow and instrumentation, selected to span the full range of inlet–soil temperature differences observed on site and to allow comparison under equivalent operational regimes.

3. Numerical Model Development

Two numerical models were implemented in MATLAB, a widely used environment for simulating thermal systems, including earth-to-air heat exchangers (EAHE), due to its robustness in handling transient energy balances and customized computational routines.

- 1.

- A hybrid model for the EAHE (serpentine pipes + water tank) was developed, calibrated and validated, corresponding to the experimental setup and against its reported measured data,

- 2.

- A baseline model of an EAHE consisting of a straight buried pipe without a water tank, used for comparison against the hybrid model’s performance. In detail, in this model, the EAHE is represented by a straight, uniformly buried pipe of 27 m length at −2.4 m depth, operating under the same ambient and soil conditions as the hybrid system. Notably, the conventional baseline model omits the water tank integration; thus, the soil thermal resistance remains unchanged along the entire length of the pipe.

Both models are one-dimensional and transient along the airflow direction, incorporating axial convective heat exchange between the air and pipe, conductive heat flow through the pipe wall, and radial heat dissipation into the surrounding soil. The pipeline was discretized into 0.50 m segments; the outlet of segment k served as the inlet of segment k + 1.

Key assumptions were adopted to simplify the analysis without significantly sacrificing accuracy, as justified by prior studies and the experimental conditions:

- The surrounding gypsum soil was thermally homogeneous and isotropic, with constant conductivity and diffusivity values. This is consistent with typical EAHE modeling practices and is supported by previous findings that soil thermal properties remain relatively stable over such time scales [24].

- Airflow inside the pipes was assumed to be fully developed and turbulent, allowing for a fixed convective heat transfer coefficient derived from Reynolds- and Nusselt-based correlations. Due to the ventilation system-controlled operation, transient fluctuations were neglected.

- Given its low thermal inertia and rapid equilibrium response, the thin PVC pipe wall was treated as conductive resistance with negligible thermal storage capacity.

- In the hybrid configuration, the buried water tank was modeled as a passive thermal mass. Its effect was represented by a stable boundary condition imposed on the adjacent soil, reflecting the tank’s high heat capacity and buffering role during the simulation period.

Using these assumptions, the governing equations for the EAHE were formulated. An energy balance on a differential pipe element can describe the heat exchange between the air inside the pipe and the soil. For a small pipe segment of length dx, the drop in air temperature dT is proportional to the difference between the air temperature and the local soil temperature. Integrating this balance from the pipe inlet (at length x = 0) to the outlet (at x = L) yields an exponential decay relationship for the air temperature along the pipe:

where

- is the air temperature at the pipe inlet.

- is the air temperature at the pipe after a length of pipe.

- is the undisturbed soil temperature far from the pipe (assumed constant over the segment).

- is the mass flow rate of air through the pipe.

- is the specific heat capacity of air.

- is the overall heat transfer coefficient between the air and the soil (W/m.K per unit length of pipe). It encompasses all the thermal resistances in series: convective resistance on the inner air side, conductive resistance of the pipe wall, and conductive resistance of the soil out to an effective far-field radius. In terms of thermal resistance. Therefore, is defined as follows:

As for the convective heat transfer coefficient, it is estimated using a Nusselt number correlation appropriate for turbulent flow inside a pipe [22], with:

where the Reynolds () and Prandtl () numbers are computed from the known properties of air and the measured flow conditions. Table 2 lists the key parameters employed in the simulation.

Table 2.

Key parameters and physical properties for numerical modeling.

Hybrid EAHE Numerical Model Validation

Before using the models for performance evaluation and comparative analysis, the hybrid model was calibrated against the experimental data during the whole measurement period to ensure its predictive accuracy. Statistical performance metrics, Normalized Mean Bias Error (MBE), and Coefficient of Variation of Root Mean Square Error (CVRMSE), were calculated. These indices are widely adopted for assessing model reliability, ensuring that deviations between measured values and simulated outputs remain within acceptable limits (ASHRAE Guideline 14-2014).

NMBE quantifies the systematic error by measuring the average bias between the observed and predicted values, indicating whether the model overestimates or underestimates the results. It is expressed mathematically as:

where

- is the experimental temperature at time .

- is the simulated temperature at time .

- is the number of data points.

According to ASHRAE Guideline 14-2014, a NMBE within ±10% is acceptable for hourly data, reflecting model reliability [25]. Furthermore, the sign of NMBE provides insight into the direction of bias, enabling adjustments during calibration phases.

CVRMSE, on the other hand, evaluates the random error or scatter by normalizing the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) to the mean observed value. This metric accounts for variability and is defined as:

where

And is the mean experimental temperature.

More specifically, a CVRMSE value below 30% is acceptable for models that predict hourly temperature trends (ASHRAE, 2014). This threshold ensures the model maintains accuracy across diverse climatic inputs and boundary conditions.

Calibration focused on fine-tuning the effective soil thermal conductivity. A series of iterative simulation runs were performed and calibration converged on an effective thermal conductivity of approximately λsoil = 0.54 W/m.K. This value suggests a modest enhancement in thermal conduction, likely due to localized soil moisture retention near the buried water tank. The final validation results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Calibration and validation metrics results for the numerical model.

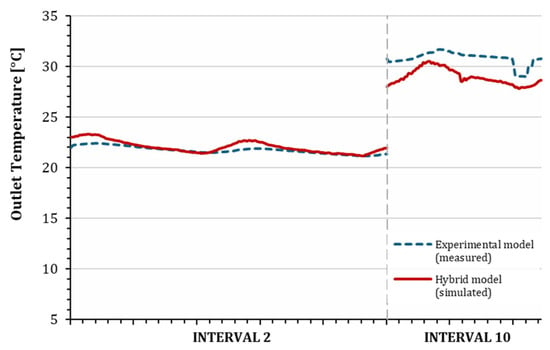

To illustrate model performance under operational extremes, two representative periods were selected:

- Interval 2 (10–11 December 2023): winter heating operation, with average inlet air temperature of 11.6 °C and outlet temperature near 22.4 °C.

- Interval 10 (4–June 2024): peak summer cooling, with inlet air temperatures exceeding 45 °C and average outlet reduction exceeding 12 °C.

Figure 6 displays the simulated and experimental outlet temperatures for these intervals. In both cases, the model successfully reproduced transient system behavior, with typical deviations within ±1.6 °C, and local peaks approaching 2.80 °C during interval 10 midday hours.

Figure 6.

Experimental and twin simulated hybrid EAHE systems outlet temperatures during Intervals 2 and 10.

This integrated calibration and validation phase confirms that the model is both statistically robust and dynamically reliable, and ready to support the performance analysis presented in the next section.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Thermal Performance Comparison

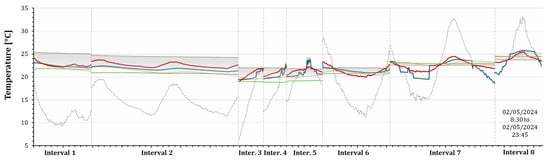

The experimental hybrid EAHE system (with subsurface water tank) was benchmarked against a conventional straight-pipe EAHE model using identical inlet air and soil temperature inputs. Outlet air temperatures for both systems were compared over 13 monitoring intervals (Figure 7). In each subplot, the solid line represents measured outlet temperature from the experimental installation, while the dashed line shows the simulated outlet temperature of the baseline EAHE model.

Figure 7.

Temperature profiles of the experimental hybrid and baseline simulated EAHE systems across 13 monitoring intervals.

Across most intervals, the baseline model yields larger temperature swings, heating and cooling, across most intervals. The hybrid system, on the other hand, moderates extremes through thermal buffering. This trade-off manifests as lower ΔT in the hybrid system under peak conditions and smoother, more stable outlet temperatures. Key observations are:

- Winter extremes (Interval 2: 10–11 December 2023). Baseline heating outperforms by ~0.8 °C, but both systems maintain outlet temperatures close to 22 °C from an inlet of ≈12 °C, demonstrating reliable heat gain in cold conditions.

- Moderate spring (Interval 8: 2–4 May 2024). The hybrid system slightly outperforms the baseline (ΔThybrid − ΔTbaseline ≈ +0.8 °C), indicating that the water tank’s thermal mass smooths soil–air exchange and enhances performance when inlet–soil gradients are moderate.

- Peak summer cooling (Interval 10: 17–18 June 2024). Baseline cooling exceeds hybrid by 2.6 °C (from inlet ≈ 42 °C to outlet ≈ 35 °C vs. 38 °C). While the baseline model thus attained a greater cooling magnitude, its outlet displayed larger daily swings linked to rapid soil-air heat transfer. The hybrid, buffered by the tank’s thermal inertia, produced a steadier outlet profile that tracked the ground temperature, offering moderate but more stable performance.

Soil temperatures at −1.2 m and −2.4 m (used as boundary conditions in both models) remained within 2 °C, confirming the consistency of subsurface thermal inputs. This comparison demonstrates that, although the conventional EAHE maximizes ΔT, the hybrid configuration offers a controlled and stable thermal performance that can be advantageous in real-world applications.

4.2. Performance Metrics and Energy Impact

Three complementary indicators were evaluated over the complete monitoring year to quantify the experimental EAHE’s performance beyond outlet temperature: thermal efficiency, coefficient of performance (COP), and estimated energy savings. Such metrics were calculated using 15-min interval data over the entire monitoring campaign, offering a high-resolution perspective of system dynamics under real climatic fluctuations.

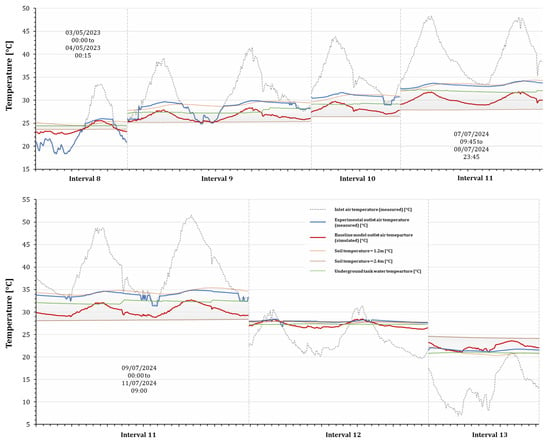

4.2.1. Thermal Efficiency

Thermal efficiency (η) is computed as the ratio between the temperature difference between the soil and the ambient inlet air, calculated at each timestep using the expression:

Here, is the outlet air temperature, is the ambient inlet temperature, and is the mean of the two soil probe measurements at −1.2 m and −2.4 m depths.

To ensure meaningful evaluation, thermal efficiency was computed only for periods where the temperature differential exceeded 2 °C. In detail, very low ΔT values in real operating conditions often reflect near-equilibrium thermal states where airflow may exchange negligible heat with the ground. In such cases, even minor environmental or sensor-induced fluctuations can cause apparent reversals in heat flow direction, obscuring the system’s performance.

Figure 8 illustrates the distribution of efficiency values as a function of the inlet–soil temperature difference. Three distinct operational regimes emerge. When ΔT exceeds 8 °C, typically observed during winter heating and summer cooling peaks, efficiency consistently ranges between 75% and 95%, confirming the system’s capacity to exploit strong gradients fully. In transitional periods, where ΔT lies between 3 and 8 °C, efficiency remains high (between 50% and 90%) but shows more dispersion, reflecting moderate thermal gain softened by the water tank’s dampening effect. Across all intervals, the mean efficiency was 73% with occasional peaks. These values align with literature reports for comparable EAHE systems.

Figure 8.

Thermal efficiency of the hybrid EAHE plotted against inlet–soil temperature gradient (ΔT).

Cross-referencing the filtered data with seasonal intervals shows a precise alignment: winter intervals (1–5 and 13) are concentrated in the high-gradient zone with a median efficiency around 85%; spring and autumn intervals (6–9, 12) dominate the moderate-gradient band with median efficiency near 75%; and summer intervals (10–11) straddle both zones, reaching up to 94% efficiency during peak afternoon cooling. This confirms the system’s seasonal responsiveness and highlights its capacity to deliver sustained performance when climatic conditions offer strong thermal potential.

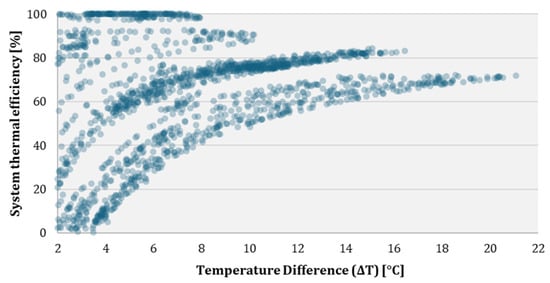

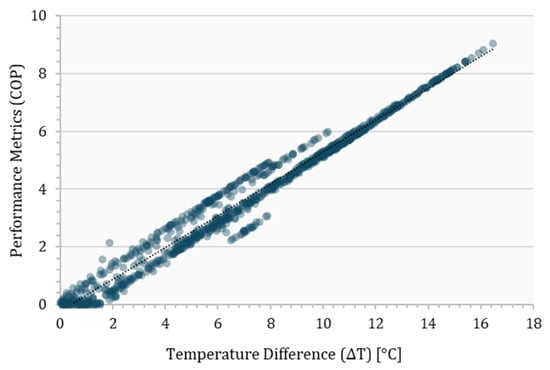

4.2.2. Coefficient of Performance (COP)

The effective Coefficient of Performance, as commonly used for EAHE configurations, is estimated via:

where (kg/s) is the mass flow rate of air, and is the electrical power input of the fan (W). As for the efficiency metric, this evaluation was also plotted against the inlet–soil temperature difference, , which represents the driving thermal gradient for heat exchange.

Figure 9 presents the resulting COP values. The graph reveals three distinct operational regimes:

Figure 9.

Variation of the experimental EAHE system’s Coefficient of Performance (COP) as a function of the inlet–soil temperature difference (ΔT).

- Low-gradient regime (): In this zone, the COP values are highly scattered and fluctuate near zero. This behavior reflects a physically marginal heat exchange under such weak thermal gradients. The system performs minimal practical work and becomes highly sensitive to noise, particularly under real-world experimental variability.

- Moderate-gradient regime (): COP stabilizes within a functional operating band, mostly between 1.0 and 2.5, indicating that for every watt of electrical input, the system provides 1–2.5 W of thermal output. These values correspond predominantly to spring and autumn intervals, where moderate gradients enable steady, if not extreme, thermal recovery.

- High-gradient regime (): During peak heating and cooling episodes, the COP rises significantly, often exceeding 3.0 and reaching values up to 4.0. These high values align with periods when ambient conditions create strong contrasts with the subsurface thermal reservoir (water tank), typically in deep winter (Intervals 1–5, 13) and summer (Intervals 10–11).

By relating COP to ΔT, the system presents adaptive performance: thermal recovery improves when climatic conditions enhance the gradient, while performance declines predictably under neutral conditions without imposing a significant electrical load. In such low-gradient periods, however, performance could be optimized by automatically disabling the EAHE fan or incorporating a motorized bypass valve that redirects airflow directly from the exterior. This solution would prevent unnecessary fan operation under unfavorable thermal conditions while maintaining adequate ventilation, enhancing the system’s overall energy efficiency.

4.2.3. Energy Saving Potential

The energy the hybrid EAHE recovers over each monitoring interval is evaluated by summing the sensible heat exchanged with the ventilation air. For a sampling step (s), mass flow rate , and specific heat , the cumulative thermal energy is:

where Δt is the time step in seconds (900 s for 15 min intervals), thermal energy is reported in kWh (downstream heating and cooling reduction due to EAHE pre-conditioning) throughout.

For contextual comparison to a mechanical baseline, and to express the result as a heat pump-electricity figure, the recovered thermal energy was compared to a reference air-source heat pump (ASHP) commonly used in Algeria, adopting temperature-dependent curves: COPHP in heating and EERHP(T) in cooling, and its performance mapping follows the same procedure obtained through a detailed methodology proven in a previous work [26]. The electricity that such a heat pump would need to deliver the same energy is:

Moreover, in addition to the variable COP and EER, the final electricity consumption associated with heating and cooling is adjusted by an overall efficiency factor ηsys = 0.91 (to reflect auxiliary and delivery effects).

Because the EAHE operates with its own ventilation fan, the electrical power required to overcome the exchanger’s pressure drop must be quantified. Following standard fluid-mechanics practice, the total pressure loss Δp of the buried pipe is calculated. The associated fan power is then:

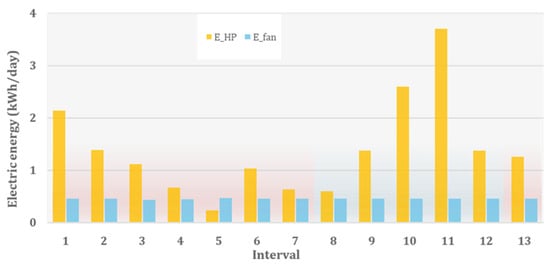

where is the air density and the total efficiency of the fan. Integrating over the operating period yields the fan energy consumption Efan. Figure 10 summarizes these impacts per interval. For each interval, the plot presents side-by-side daily bars of:

Figure 10.

Interval-wise daily heat-pump electricity consumption referenced to a temperature-dependent ASHP baseline and EAHE fan energy consumption.

- The heat-pump electricity requirement EHP (kWh/day),

- The fan energy consumption Efan (kWh/day).

In detail, across the 13 monitored intervals, the EAHE recovered 80.59 kWh, corresponding to a mean of 3.92 kWh/day. The ASHP-referenced electricity consumption now sums to 34.59 kWh, averaging 1.40 kWh/day. Fan consumption over the same periods totals 9.13 kWh.

Two summer and late-year intervals (Nos. 11 and 13) still dominate the totals, contributing nearly 53% of and 35% of Efan, reflecting sustained gradients and longer favorable exposure. Shoulder-season windows yield modest but steady avoided electricity consistently with reduced ΔT.

Subtracting the fan energy consumption shows that most intervals remain beneficial, but interval five exhibits negative net savings. In detail, in this interval’s period, the fan consumed a total of 0.23 kWh, while the ASHP electricity requirement was only 0.12 kWh, leading to net losses of −0.11 kWh. All other intervals produced positive net savings, with the most significant net gains (2.89 kWh and 3.09 kWh) occurring during the long summer and late-year runs (11 and 13).

These results underscore the importance of dynamic fan control; When the inlet–soil gradient is small and recovered heat is insufficient to offset fan power, bypassing the EAHE or shutting off the fan will prevent the system from acting as a net electrical load.

Conversely, the EAHE should operate continuously under favorable gradients to maximize heat recovery. Expressed as energy density, the campaign average remains 0.132 kWh/day m−1, affirming that the compact 27 m exchanger delivers appropriate energy densities for pre-conditioning while preserving footprint efficiency.

It should be noted that Intervals 8 and 12 exhibit similar average inlet temperatures (24.69 °C against 24.31 °C respectively), yet the cumulative recovered energy and heat-pump-equivalent electricity differ markedly. The difference is related to the time-resolved behavior; during Interval 8, the outlet remained close to the inlet for most of the period (∣Tout − Tin∣ was small), so each 15-min step contributed little sensible heat and the integrated Erecovered remained low. By contrast, Interval 12 presented sustained periods with larger ∣Tin − Tout∣ and stronger ∣Tin − Tsoil∣, producing higher per-step exchange and, under the temperature-dependent COP/EER mapping, a higher EHP.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the performance of a hybrid Earth–Air Heat Exchanger (EAHE) system combining a serpentine pipe layout with a subsurface water tank, designed for passive air pre-conditioning in a hot–arid Algerian context. Through year-round experimental monitoring and numerically calibrated simulations, the system’s behavior was examined across thirteen operational intervals, encompassing seasonal extremes and transitional periods. The proposed configuration contributes a novel approach to optimizing thermal regularity and land efficiency in residential or semi-urban environments.

The findings demonstrate that the hybrid EAHE provided a consistent thermal modulation across seasons. The hybrid system showed improved output regularity and performance, particularly under moderate gradients; COP values reached up to 4.0 and thermal efficiencies exceeded 90% during high-gradient periods, with an average above 70% over the year and reaching near-optimal values during thermal peak loads, confirming effective energy recovery. Energy saving calculations revealed substantial reductions in ventilation heating and cooling loads, particularly under peak demand conditions, reaching up to 80.6 kWh recovered and 34.59 kWh of avoided ASHP electricity based on a variable temperature-dependent performance COP/EER. After 9.13 kWh of fan use, the net saving is 25.46 kWh. Daily, this corresponds to about 3.92 kWh/day recovered and about 1.4 kWh/day as heat-pump electricity requirement on average across the campaign. Seasonally, the long summer and late-year windows (Intervals 11, 13) dominate both recovery and net benefits, whereas shoulder-season intervals yield modest gains; only Interval 5 is net-negative under weak gradients, underscoring the value of bypass/fan shut-off to prevent net electrical losses.

The water tank’s thermal inertia played a central role in dampening temperature fluctuations, and the serpentine layout allowed deeper and more distributed soil heat harvesting, particularly advantageous during spring and autumn. Notably, when analyzed against inlet–soil gradients, efficiency and COP followed physically meaningful trends, reinforcing the robustness of the real-world measurement.

This configuration proves particularly suitable for compact, space-constrained, or thermally sensitive applications in arid climates, where thermal stability, soil–water synergies, and moderate land occupation are prioritized. While the hybrid system may not maximize ΔT under all conditions, it offers a more controlled and spatially efficient alternative, an attribute increasingly valuable in dense urban settings.

It is worth noting that certain limitations remain, chief among which are:

- Soil temperature data were limited to two depths in proximity to the water tank, which may not fully capture spatial thermal heterogeneity across the installation zone.

- The comparative baseline employs a single-depth straight pipe at −2.4 m, whereas the hybrid uses a depth-distributed serpentine (−1.2 to −2.4 m); the geometries are therefore not strictly equivalent. While results are normalized to the inlet–soil temperature difference (ΔT) and analyzed in season-specific intervals, depth selection can favor higher ΔT in the baseline.

- The baseline simulation model, although calibrated, is governed by simplified assumptions that do not incorporate transient soil thermal inertia or dynamic environmental coupling, potentially affecting short-term predictive accuracy.

- Experimental monitoring was conducted over a single climatic year, and while intervals were selected to reflect seasonal diversity, long-term performance consistency under atypical weather patterns remains unverified.

- Although incorporating subsurface water tanks aligns with widely adopted construction practices in Algeria and the hybrid configuration demonstrates measurable thermal stability benefits, its economic advantage over a conventional EAHE is not yet established. Accordingly, a dedicated life-cycle cost assessment, supported by multi-site validation across different soil types and climatic conditions, is required to verify scalability and confirm cost-effectiveness beyond thermal performance alone.

- The proposed configuration was tested on a single experimental rig, implying that broader generalizations across soil types, geographic locations, and design scales should be approached cautiously until further multi-site or parametric studies are conducted.

- In the numerical analysis, ambient air temperature was used as the inlet boundary condition. Coupling the EAHE to a specific building’s envelope and internal gains would require an integrated building energy model and is deferred to future studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.O. and A.M.; methodology, S.O., A.M., F.L., M.M.G. and C.D.P.; software, S.O. and O.B.; validation, S.O.; formal analysis; S.O. and A.M.; investigation, S.O., A.M. and O.B.; resources, A.M.; data curation, S.O., A.M. and O.B.; writing—original draft preparation, S.O.; writing—review and editing, S.O., A.M., F.L., C.D.P., T.A.K.B., D.B. and M.M.G.; visualization, S.O.; supervision, A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- IEA. World Energy Outlook 2024; IEA: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Deroubaix, A.; Labuhn, I.; Camredon, M.; Gaubert, B.; Monerie, P.-A.; Popp, M.; Ramarohetra, J.; Ruprich-Robert, Y.; Silvers, L.G.; Siour, G. Large Uncertainties in Trends of Energy Demand for Heating and Cooling under Climate Change. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Wei, H.; He, X.; Du, J.; Yang, D. Experimental Evaluation of an Earth–to–Air Heat Exchanger and Air Source Heat Pump Hybrid Indoor Air Conditioning System. Energy Build. 2021, 246, 111752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Huang, B.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Y. Comprehensive Review on Climatic Feasibility and Economic Benefits of Earth-to-Air Heat Exchanger (EAHE) Systems. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2024, 68, 103862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordoloi, N.; Sharma, A.; Nautiyal, H.; Goel, V. An Intense Review on the Latest Advancements of Earth Air Heat Exchangers. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 89, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enerdata. Algeria Energy Report 2022; Enerdata: Grenoble, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Statista. Algeria’s Energy Profile: Natural Gas and Electricity Consumption in 2024; Statista: Hamburg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Albarghooth, A.; Ramiar, A.; Ramyar, R. Earth-to-Air Heat Exchanger for Cooling Applications in a Hot and Dry Climate: Numerical and Experimental Study. Int. J. Eng. 2023, 36, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakhri, N.; Benzaoui, A. Experimental Investigation of the Performance of Earth-to-Air Heat Exchangers in Arid Environments. J. Arid. Environ. 2021, 180, 104215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Energy and Mines. Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Development Plan (2015–2030); Ministry of Energy and Mines: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fazlikhani, F.; Goudarzi, H.; Solgi, E. Numerical Analysis of the Efficiency of Earth to Air Heat Exchange Systems in Cold and Hot-Arid Climates. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 148, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, J.; Li, L.; Wang, F.; Gang, W. Performance Evaluation of EAHE in Arid and Semi-Arid Climates Based on Parametric Simulation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darius, D.; Misaran, M.S.; Rahman, M.M.; Ismail, M.; Amaludin, A. Effects of Soil Moisture and Type on Thermal Performance of EAHE. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 226, 012120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouki, N.; D’Agostino, D.; Vityi, A. Properties of Earth-to-Air Heat Exchangers (EAHE): Insights and Perspectives Based on System Performance. Energies 2025, 18, 1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshlak, H. A Review of Earth-Air Heat Exchangers: From Fundamental Principles to Hybrid Systems with Renewable Energy Integration. Energies 2025, 18, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, D.M.N.; Aljubury, I.M.A.; Al Maimuri, N.M.L.; Al-Obaidi, M.A.; Rashid, F.L.; Ameen, A.; Dong, S.; Mukhtar, Y. Experimental Evaluation of a Hybrid Evaporative and Groundwater Cooling System for Enhancing Photovoltaic Efficiency in Arid Climates. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 35571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadi, S.; Shahrestani, M.I.; Sayadian, S.; Maerefat, M.; Poshtiri, A.H. Performance Analysis of an Integrated Cooling System Consisted of Earth-to-Air Heat Exchanger (EAHE) and Water Spray Channel. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2020, 143, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzaama, M.H.; Menhoudj, S.; Mokhtari, A.M.; Lachi, M. Comparative Study of the Thermal Performance of an Earth Air Heat Exchanger and Seasonal Storage Systems: Experimental Validation of Artificial Neural Networks Model. J. Energy Storage 2022, 53, 105177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, N.; Rosa, N.; Monteiro, H.; Costa, J.J. Advances in Standalone and Hybrid Earth-Air Heat Exchanger (EAHE) Systems for Buildings: A Review. Energy Build. 2021, 240, 111532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betti, G.; Tartarini, F.; Nguyen, C.; Schiavon, S. CBE Clima Tool: A Free and Open-Source Web Application for Climate Analysis Tailored to Sustainable Building Design. Build. Simul. 2024, 17, 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ajmi, F.; Loveday, D.L.; Hanby, V.I. The Cooling Potential of Earth–Air Heat Exchangers for Domestic Buildings in a Desert Climate. Build. Environ. 2006, 41, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdane, S.; Mahboub, C.; Moummi, A. Numerical Approach to Predict the Outlet Temperature of Earth-to-Air-Heat-Exchanger. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2021, 21, 100806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdane, S. Parametric Study of Air/Soil Heat Exchanger Destined for Cooling/Heating the Local in Arid and Semi-Arid Regions. Ph.D. Thesis, University Mohamed Khider of Biskra, Biskra, Algeria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mehdid, C.-E.; Benchabane, A.; Rouag, A.; Moummi, N.; Melhegueg, M.-A.; Moummi, A.; Benabdi, M.-L.; Brima, A. Thermal Design of Earth-to-Air Heat Exchanger. Part II: A New Transient Semi-Analytical Model and Experimental Validation for Estimating Air Temperature. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 538–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE. Guideline 14-2014; Measurement of Energy, Demand, and Water Savings; American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ounis, S.; Aste, N.; Butera, F.M.; Del Pero, C.; Leonforte, F.; Adhikari, R.S. Optimal Balance between Heating, Cooling and Environmental Impacts: A Method for Appropriate Assessment of Building Envelope’s U-Value. Energies 2022, 15, 3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).