Abstract

The ordinary Portland cement (OPC) manufacturing process is highly resource-intensive and contributes to over 5% of global CO2 emissions, thereby contributing to global warming. In this context, researchers are increasingly adopting geopolymers concrete due to their environmentally friendly production process. For decades, industrial byproducts such as fly ash, ground-granulated blast-furnace slag, and silica fume have been used as the primary binders for geopolymer concrete (GPC). However, due to uneven distribution and the decline of coal-fired power stations to meet carbon-neutrality targets, these binders may not be able to meet future demand. The UK intends to shut down coal power stations by 2025, while the EU projects an 83% drop in coal-generated electricity by 2030, resulting in a significant decrease in fly ash supply. Like fly ash, slag, and silica fume, natural clays are also abundant sources of silica, alumina, and other essential chemicals for geopolymer binders. Hence, natural clays possess good potential to replace these industrial byproducts. Recent research indicates that locally available clay has strong potential as a pozzolanic material when treated appropriately. This review article represents a comprehensive overview of the various treatment methods for different types of clays, their impacts on the fresh and hardened properties of geopolymer concrete by analysing the experimental datasets, including 1:1 clays, such as Kaolin and Halloysite, and 2:1 clays, such as Illite, Bentonite, Palygorskite, and Sepiolite. Furthermore, this review article summarises the most recent geopolymer-based prediction models for strength properties and their accuracy in overcoming the expense and time required for laboratory-based tests. This review article shows that the inclusion of clay reduces concrete workability because it increases water demand. However, workability can be maintained by incorporating a superplasticiser. Calcination and mechanical grinding of clay significantly enhance its pozzolanic reactivity, thereby improving its mechanical performance. Current research indicates that replacing 20% of calcined Kaolin with fly ash increases compressive strength by up to 18%. Additionally, up to 20% replacement of calcined or mechanically activated clay improved the durability and microstructural performance. The prediction-based models, such as Artificial Neural Network (ANN), Multi Expression Programming (MEP), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGB), and Bagging Regressor (BR), showed good accuracy in predicting the compressive strength, tensile strength and elastic modulus. The incorporation of clay in geopolymer concrete reduces reliance on industrial byproducts and fosters more sustainable production practices, thereby contributing to the development of a more sustainable built environment.

1. Introduction

It is widely acknowledged that the manufacturing and incorporation of OPC in the construction industry are catalysts not only for emitting staggering amounts of Carbon dioxide (CO2) into the environment, but also for being energy-intensive [1,2,3]. Approximately, producing 1 ton of OPC requires 3.4 gigajoules (GJ) of thermal energy, 110 kilowatt-hours (kWh) of electrical energy and emits substantial amounts of CO2, ranging from 802 to 855 kg [4,5]. The atmosphere’s CO2 content surpassed 417 parts per million (ppm) in 2020, the highest level observed in the past 2.5 million years [6]. The introduction of geopolymer concrete (GPC) into the construction sector presents a promising prospect for sustainability in future built engineering projects by addressing environmental concerns and ensuring the responsible management of natural resources [7,8].

GPC is an eco-friendly inorganic composite derived from rich alumina- and silica-based supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) with alkaline activators, which form a hardened binder through a chemical reaction called geopolymerisation—a polycondensation reaction that occurs under alkaline or acidic conditions [9,10]. In alkaline systems, aluminate and silicate species dissolve from their precursors and subsequently recombine to form sialate (-Si-O-Al-O-) and polysialate (-Si-O-Al-O–Si-O-) linkages, which are stabilised by alkali cations such as Na+ and K+ [11]. This process yields highly durable, chemically resistant binders that possess mechanical strengths exceeding those of many conventional cement-based systems [12]. Acidic activation remains less extensively studied; however, it is increasingly recognised for its role in forming aluminosilicate-phosphate networks (-Si-O-Al-O-P-), which enhance thermal stability and dielectric properties [13]. For decades, industrial byproducts and industrially processed aluminosilicate-based pozzolanic materials, such as fly ash [14], Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag (GGBFS) [15], silica fume [16], Metakaolin (MK) [17], glass powder [18], etc, have been used as SCMs for not only reducing carbon footprint, but also lowering the construction costs. These materials have been utilised as SCMs to partially replace OPC and to produce geopolymer concrete, with complete OPC replacement [19,20].

Research indicates that geopolymer concrete exhibits mechanical strength comparable to that of traditional concrete. Rahman and Al-Ameri [21] developed self-compacting geopolymer concrete using 100% fly ash, a single alkali activator, with no superplasticiser. This study achieved a compressive strength of 40 MPa after 28 days of ambient curing, comparable to that of conventional M40-grade concrete. Mayhoub et al. [22] investigated the development of geopolymer reactive powder concrete under varying curing conditions, including hot-air, heating, and microwave heating, by replacing 35%, 50%, and 100% of the OPC with slag. The results showed that 100% slag-containing samples achieved a compressive strength that was almost 9% higher than that of 50% slag-containing samples in microwave curing with a 4-min constant power level of 720 W. Srivastava et al. [23] also reported that the compressive strength of geopolymer concrete is identical or even higher than that of conventional concrete. Geopolymer concrete exhibited superior durability performance relative to traditional concrete. Generally, geopolymer concrete displays greater resistance to high temperatures and fire resistance due to its ceramic-like properties, in comparison to OPC concrete [23].

Nevertheless, the durability of geopolymer concrete primarily depends on the proportions of OPC and precursors, such as fly ash, slag, and other SCMs. Mehta and Siddique [24] reported that replacing up to 20% of OPC with fly ash significantly improved the mechanical strength, while porosity, water absorption, chloride permeability, and sorptivity decreased substantially. This reduction transpires due to the presence of both N-A-S-H and C-A-S-H, which contribute to the densification and compaction of the geopolymer matrix’s microstructure upon the addition of OPC [24].

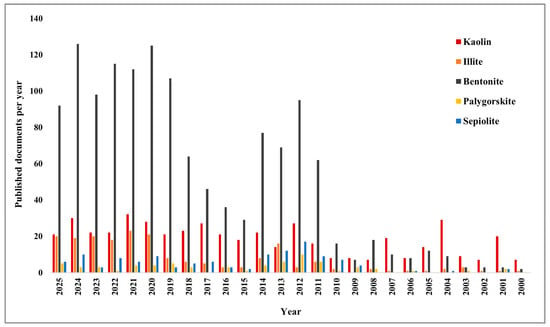

The yearly production of fly ash in the US, Canada, UK, Germany, Australia, France, Denmark, Italy, the Netherlands, India, and China is 75, 6, 15, 40, 10, 3, 2, 2, 2, 112, and 100 million tons, respectively and among them only 20% is being used in the construction sector, worldwide [25]. However, the supply of traditional SCMs, such as fly ash, is expected to decline due to rising demand for carbon neutrality across industries, ongoing construction, and the decline of coal-fired power stations [26,27]. Given the global distribution disparities, it’s uncertain whether blast furnace slag, silica fume, and other industrial byproducts will be available in sufficient quantities to meet rising demand [28,29]. Therefore, current research should focus on converting locally available natural clay, waste, or contaminated soil, mud, and sewage sludge into pozzolanic SCMs. Among them, natural clay can be a potent option due to its worldwide availability, cost-effectiveness, and eco-friendliness, as it is an earth-based material with various mineral contents [30]. Being an abundant source of silica and alumina, clay can be effectively used as a pozzolanic material through proper surface activation modification [31,32]. However, there are some criteria to choose a clay as an SCM. According to ASTM, the total amount of SiO2, Al2O3, and Fe2O3 should be at least 70% by weight, ≤34% should be retained on a 45 µm sieve, the moisture content should be ≤3.0%, and the Strength Activity Index (SAI) should be at least ≥75% than that of the control mix [33]. Although clays have significant potential as SCMs, there appears to be limited effort among researchers to investigate specific clay types and their suitability for these applications. Figure 1 illustrates the research trend about different natural clays over the past 25 years, as collected from the Scopus database.

Figure 1.

Research trend of various natural clays over the past 25 years.

Although naturally available clays may represent a prime alternative for substituting existing supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs), limited research has been conducted to date. Most of this research primarily centres on clay activation techniques for various raw clays and their mechanical properties [34,35]. Furthermore, an appropriate treatment or modification method for converting raw clay into pozzolanic clay has not been conspicuously identified. The various types of clay, different activation methods, untreated clay, and their impact on the workability and mechanical performance of geopolymer concrete have not been comprehensively understood due to the absence of a systematic review. Therefore, this review summarises recent research conducted by various researchers, including available clay treatment methods, workability, and strength properties of clay-based geopolymers composites.

Furthermore, various prediction-based models and their accuracy in forecasting the mechanical performance of geopolymer concrete have been summarised. Additionally, the existing research gap and the recommended areas for future investigation have been included. The authors believe that, after thoroughly reading this review, researchers in this field will have a clear understanding of the existing research and the type of research that needs to be conducted in the future to optimise clay-geopolymer composites for the safe and sustainable use of concrete.

Potential Challenges in Utilising Clay as an SCM

Clay-based SCMs offer promising sustainability benefits; however, their practical implementation encounters various challenges. A primary challenge lies in the variability of mineral composition, as natural clays exhibit considerable differences in reactive minerals such as kaolinite, illite, and montmorillonite. This variability influences pozzolanic reactivity and complicates quality control processes, primarily when clays originate from diverse geological sources [36]. Furthermore, the complexity of activation presents a significant challenge: clays generally require thermal treatment (calcination) at precisely controlled temperatures—typically between 600 and 950 °C—to achieve proper reactivity. Incorrect calcination, whether too high or too low, can negatively impact performance. Moreover, the energy-intensive nature of this process raises concerns about sustainability [37,38]. Furthermore, impurities such as quartz, carbonates, or organic matter can disrupt hydration reactions and diminish the effectiveness of the SCM process [39]. These factors underscore the need for rigorous characterisation and tailored activation protocols when incorporating clay into cementitious systems.

2. Clays and Their Chemical Compositions

Clay is widely available on Earth’s surface and results from the erosion of precursor minerals, such as quartz, feldspar, and other clays in small quantities [40]. Illite, kaolinite, and montmorillonite (MMT) are three common clay minerals. In recent years, Kaolinite-based clay has been reported as an auspicious pozzolanic material [41]. However, in recent years, there has been a growing interest in exploring the potential of other types of clays as SCMs, such as Illite [32], Bentonite/Montmorillonite (MMT) [33], Halloysite [34], Palygorskite [35], and Sepiolite [36], among others. The following section outlines the properties and chemical constituents of the clays currently under exploration.

2.1. Kaolinite Clay

Both natural minerals and industrial by-products (secondary clays) can be used to make kaolinitic clay-based pozzolans [42]. Structurally, kaolinite consists of a single tetrahedral sheet made up of disilicate anion (Si2O5)2− and a single octahedral sheet composed of dihydroxy aluminium cation (Al2(OH)4)2+, which is called a 1:1 layered structure [43,44]. Under ambient conditions, kaolinite is incredibly stable. The mineral loses its crystallinity upon sufficient heating through dehydroxylation, releasing active silica and alumina [45,46]. Therefore, this dehydroxylation process forms highly reactive metakaolin (MK), widely used as a pozzolanic material [47].

Chemically, silicon oxide (SiO2), aluminium oxide (Al2O3) and iron oxide (Fe2O3) are the major components of this clay. To maintain high levels of pozzolanic reaction, these three major components should comprise above 70% of the total components [48]. In OPC and geopolymer composites, these three components play a crucial role. For OPC, SiO2, combined with CaO, forms two primary silicates, dicalcium silicate (C2S) and tricalcium silicate (C3S). These silicates further react with water to form calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) gel, which is the primary strength-providing compound in concrete [49]. Whereas Al2O3 forms tricalcium aluminate (C3A), which further forms ettringite and monosulfate. These compounds help improve workability and strength properties [50]. In the case of geopolymer, under an alkaline environment, Al and Si dissociate from the MK, forming an aluminosilicate network that enhances workability and strength [51]. Minor chemical oxides present in kaolin, such as iron oxide (Fe2O3), calcium oxide (CaO), magnesium oxide (MgO), potassium oxide (K2O), titanium dioxide (TiO2), and phosphorus pentoxide (P2O5), are instrumental in the geopolymerisation process and its fundamental mechanisms. Fe2O3 can substitute for Al3+ within the kaolinite structure, resulting in lattice distortion that improves the mechanical strength and densification of the geopolymer matrix [52]. CaO and MgO affect secondary gel phases such as C-A-S-H and M-A-S-H, altering setting time and strength development. At the same time, K2O influences thermal properties and phase stability [52,53]. TiO2 and P2O5 can function as nucleation sites or alter the polymeric network through Ti-O-Si or P-O-Al bonds, thereby enhancing the chemical resistance and structural integrity of the final geopolymer [54].

Challenges involved in surface modification and activation: One major issue is the limited reactivity of raw kaolin, which necessitates high temperature (600 °C to 800 °C). This process is energy-intensive [55]. Furthermore, high-speed ball grinding of clay—a mechanical activation method—increases surface area and induces structural disorder. Nonetheless, it necessitates meticulous regulation to avert excessive energy consumption and particle agglomeration [56].

2.2. Illite Clay

Illite clay, primarily used in brick production, is abundant and relatively inexpensive. However, they are not widely used as pozzolanic materials for SCMs due to their lower pozzolanic activity compared to kaolinitic clay [57]. Structurally, Illite is a 2:1 layered mineral clay, which means that it contains two sheets of silicon tetrahedra () entrapped one single octahedral aluminium (Al2(OH)4) [40]. Raw Illite clay is not reactive. For them to be pozzolanic, they need to have amorphous crystal structures. This process involves removing or vaporising the hydroxyl group from the structure through high heating, a process known as dehydroxylation [58]. After dehydroxylation, Illite also produces MK as a pozzolanic material, but it is less reactive than kaolinitic clay, despite having the same energy consumption. It is due to the structure of Illite, which is 2:1, requiring more energy to break the ionic bond than that of the 1:1 layer kaolin. SiO2, Al2O3, K2O and Fe2O3 are the major components of this clay [59]. SiO2 and Al2O3 serve as the fundamental components of the aluminosilicate framework [60]. Fe2O3 can replace Al3+ within the tetrahedral or octahedral layers, forming Fe–O–Si or Fe–O–Al bonds that enhance the mechanical strength and durability of the geopolymer. K2O, primarily found in illite, acts as a natural alkali source, facilitating the dissolution of aluminosilicate phases and promoting the development of geopolymeric gels [61,62]. Minor oxides, including CaO and MgO, facilitate the formation of secondary phases such as C-A-S-H and M-A-S-H gels, thereby supporting early strength development and modifying setting behaviour. Concurrently, TiO2 and P2O5 enhance chemical resistance and improve microstructural integrity [60,62]. Challenges involved in surface modification and activation: The process of modifying and activating illite clay for geopolymerisation presents several challenges owing to its complex mineral composition and comparatively lower reactivity relative to kaolinite. Its layered structure and elevated potassium content diminish its responsiveness to conventional thermal activation, making complete dehydroxylation difficult and impeding its transformation into a reactive amorphous phase. Mechanical activation may increase surface area and induce structural disorder; however, this method alone generally does not significantly improve reactivity [63]. Furthermore, the surface modification of illite via surfactants or microwave-assisted treatments can alter its electrical conductivity and morphology. Nevertheless, these techniques necessitate meticulous control and may not be appropriate for large-scale industrial applications due to their expense and complexity [64].

2.3. Bentonite/Montmorillonite (MMT) Clay

Bentonite, a type of clay formed from weathered volcanic ash, is primarily composed of montmorillonite (MMT). Bentonite is a 2:1 layered mineral clay, consisting of two sheets of silicon tetrahedra enclosing a single octahedral aluminium or magnesium (AlO6 or MgO6) [65]. Surface modification is required to make bentonite clay pozzolanic. At standard conditions, bentonite is extremely non-reactive due to its strong Si-O and Al-O bonds. The dehydroxylation process may enhance its pozzolanic activity, but a strongly alkaline medium is more favourable for its full-fledged amorphisation [66]. SiO2, Al2O3, MgO and Fe2O3 are the significant components of this clay. In an alkaline environment, soluble silica produces a geopolymer gel.

Additionally, aluminates form alumino-silicate bonds during the geopolymerization process, which affects early strength. CaO and MgO facilitate the formation of secondary gel phases such as C-A-S-H and M-A-S-H, thereby enhancing early strength and influencing setting behaviour. Simultaneously, K2O and Na2O serve as alkali sources, assisting in the dissolution of aluminosilicate phases and promoting gel formation. Furthermore, TiO2 and P2O5 act as nucleation sites or modify the polymeric network, thereby improving the chemical resistance and microstructural integrity of the final geopolymer product [67,68].

Challenges involved in surface modification and activation: Surface modification and activation of bentonite clay for geopolymerisation pose challenges due to its complex mineral composition and high water absorption capacity. Natural bentonite, predominantly composed of montmorillonite, exhibits low surface activity and limited sorption capabilities in its unmodified state, necessitating chemical or thermal treatment to enhance its efficacy [69]. Furthermore, surfactant modification may reduce surface area and impede interlayer expansion, thereby potentially limiting its effectiveness within geopolymer matrices [69].

2.4. Halloysite Clay

Halloysite, a naturally occurring, harmless clay belonging to the kaolinite subgroup, has a unique hollow, nanotubular structure. Although it is classified in the kaolin subclass, its structural layer is 1:1, like kaolin [70]. Halloysite consists of a single sheet of silicon tetrahedra (SiO4, with four oxygen atoms) that entraps a single octahedral unit of aluminium or magnesium (AlO6 or MgO6). Its outer layer consists of silicon-oxygen (Si-O-Si) bonds, and the inner layer consists of aluminium or magnesium surrounded by a hydroxyl group [70,71]. Halloysite can be utilised as a pozzolanic material in conjunction with OPC and highly reactive geopolymer composites, such as MK, after undergoing surface modification or calcination. The particle size of this clay is finer, with a larger surface area and improved adsorption capabilities [72,73].

Major and minor chemical oxides in Halloysite, such as Fe2O3, CaO, MgO, K2O, and Na2O, along with trace oxides such as TiO2 and P2O5, are essential to the geopolymerisation process and its underlying mechanism. The primary oxides, SiO2 and Al2O3, constitute the framework of the aluminosilicate network, which is pivotal for the formation of geopolymer gel. Furthermore, Fe2O3 can replace Al3+ in octahedral sheets, thereby enhancing mechanical strength and facilitating the formation of Fe-O-Si or Fe-O-Al bonds [74]. K2O and Na2O, which are commonly present in halloysite, function as natural alkali sources that enable the dissolution of aluminosilicate phases and promote gel formation. CaO and MgO contribute to the formation of secondary phases such as C-A-S-H and M-A-S-H gels, thereby enhancing early strength and influencing setting behaviour [75]. Furthermore, trace oxides, including TiO2 and P2O5, can serve as nucleation sites or modify the polymeric network, thus improving chemical resistance and the microstructure of the final geopolymer [76].

Challenges involved in surface modification and activation: The process of modifying and activating Halloysite clay for geopolymerisation presents several difficulties, arising from its nanotubular morphology, hydrated state, and heterogeneous surface chemistry. In contrast to Kaolinite, Halloysite incorporates interlayer water molecules, rendering thermal activation more intricate. Heating within the range of 500–900 °C induces dehydroxylation and structural disruption; however, exposures exceeding 1000 °C may compromise or decompose the tubular architecture, thereby diminishing reactivity and surface area [77]. Furthermore, the heterogeneous surface charge and hydrogen bonding of Halloysite contribute to aggregation and inadequate dispersion, impeding its interaction with alkali activators and consequently reducing its efficacy within geopolymer matrices [78].

2.5. Palygorskite Clay

With its distinct 2:1 layer structure (two sheets of silicon tetrahedra () and one single octahedral aluminium or magnesium (AlO6 or MgO6), Palygorskites are a fibrous clay mineral that belongs to the phyllosilicate group [79]. Palygorskite has a fibrous or needle-like morphology in contrast to common clays with a flat or lamellar structure, such as montmorillonite or kaolinite. Its unique structure contributes to its large surface area and adsorptive qualities, making it useful for a range of industrial operations, including geopolymer technologies, adsorption, and catalysis [80,81]. SiO2, Al2O3, MgO and Fe2O3 are the significant components of this clay [79]. In geopolymer composites, the presence of silica facilitates geopolymerization. Additionally, substituting calcium ions with alumina and magnesium makes the geopolymer composites thermally stable and less susceptible to chemical degradation. Minor oxides such as K2O and N2O facilitate the dissolution of aluminosilicate phases. Trace oxides, such as TiO2, enhance microstructural integrity, chemical resistance, and catalytic activity [79,82].

Challenges involved in surface modification and activation: Surface modification and activation of palygorskite clay for geopolymerisation present considerable challenges due to its fibrous morphology, channel-filled structure, and heterogeneous chemical composition. The principal issue is that naturally occurring palygorskite often contains impurities and aggregated particles, which reduces reactive surface area [83]. Furthermore, the formation of silica–palygorskite heterostructures through acid activation and surfactant-assisted assembly enhances porosity and adsorption capacity; however, it also introduces additional complexity into the synthesis process and scalability [84].

2.6. Sepiolite Clay

Sepiolite is unique among 2:1 clays, as it has a fibrous structure similar to that of palygorskite. Its distinct 2:1 layer structure contains two sheets of silicon tetrahedra () and one single octahedral magnesium (MgO6) [85]. Sepiolite has a higher surface area due to its fibrous structure, which enhances adsorption capacity and makes it a significant material for the extraction of heavy metals or pollutants [85,86]. SiO2, MgO, and Al2O3 are the significant components of this clay [85]. Sepiolite can be used as an SCM after activation by calcination or an alkaline solution [87].

The primary oxides, including MgO, SiO2, and Al2O3, constitute the fundamental structure of sepiolite. MgO contributes to the formation of the trioctahedral sheet and facilitates the development of magnesium-aluminosilicate hydrate (M-A-S-H) gels during alkali activation [85]. Minor oxides, such as Fe2O3, CaO, K2O, Na2O, along with trace elements like TiO2 and P2O5, also influence the geopolymerisation process by affecting the rates of dissolution, ionic equilibrium, and gel formation. Fe2O3 substitutes for Al3+ within the octahedral sheets, resulting in the formation of Fe-O-Si or Fe-O-Al bonds that enhance mechanical strength and durability [88]. CaO and Na2O promote the development of secondary gel phases such as C-A-S-H, thereby improving early strength characteristics. Furthermore, TiO2 and P2O5 may act as nucleation sites or modify the polymeric network, thereby enhancing chemical resistance and the microstructure of the final geopolymer [89].

Challenges involved in surface modification and activation: Surface modification and activation of sepiolite clay for geopolymerisation pose several challenges due to its fibrous morphology, low cation-exchange capacity, and complex channel structure. Sepiolite’s natural structure resists swelling and dispersion in aqueous media, making mechanical activation difficult without inducing aggregation or fibre damage and requires precise control [90]. Again, acid activation increases surface area and porosity by eliminating impurities such as dolomite and calcite. Nevertheless, excessive acid concentrations may induce structural collapse and lead to the formation of amorphous silica [91]. Furthermore, surface modification using coupling agents, such as silanes or surfactants, can enhance compatibility with polymer matrices and improve dispersion. However, these techniques are frequently costly and pose challenges in scaling up for industrial application [92]. Table 1 summarises the chemical constituents of different types of clay.

Table 1.

Chemical compositions of different types of clay (average values from references).

Raw clay must undergo various treatments to become reactive and pozzolanic, making it suitable for use as an SCM. However, clay materials must meet specific, crucial chemical and physical parameters to be considered a potential pozzolanic material. In clay minerals, SiO2 and Al2O3 are the two prerequisite components that control pozzolanic activity [111]. The European standard EN 197-1 stipulates that the chemical composition of a pozzolanic material must contain at least 25% active SiO2 by weight [112]. According to the French standard NF P18 513, the total quantity of SiO2 and Al2O3 should be0% for MK [113]. According to ASTM C 618, a material can be considered pozzolanic if the sum of SiO2, Al2O3, and Fe2O3 is at least 70% by weight [33].

Moreover, the standards mentioned above specify additional physical requirements, including types of materials, ignition loss, fineness of the pozzolanic material, and strength activity index. Table 2 summarises and compares the standards, describing the chemical and physical requirements of pozzolanic materials used as SCMs.

Table 2.

Chemical and physical requirements of pozzolanic materials following ASTM C 618, EN 197-1 and NF P18 513.

3. Clay Activation/Treatment Methods

Raw clay’s crystalline structure is inert and exhibits minimal pozzolanic activity; therefore, it must undergo processing before utilisation as an SCM. The procedure entails amorphisation, which involves disintegrating the crystalline structure to enhance reactivity upon transformation into an amorphous state [114]. By increasing the amount of reactive silica and alumina available, this structural alteration enables the material to interact efficiently with calcium hydroxide in cement, generating more calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H) and thereby enhancing strength and durability [115]. Similarly, in geopolymer composites, reactive silica and alumina react with alkali activators to form sodium aluminosilicate hydrate (N-A-S-H) gel, similar to S-H in traditional cement [116].

The most popular clay treatment method is thermal/calcination, which has been employed in numerous studies [59,117,118,119,120]. However, considering the high energy requirements and high cost of the calcination process, researchers are diverting their interest to alternative treatment methods, including mechanical [121,122] and chemical [123,124,125,126]. Therefore, the following section contains various treatment methods for natural clay.

3.1. Thermal Activation

In thermal treatment, the clay material is heated to a specific temperature, which causes the octahedral layer to dehydroxylate-that is, the hydroxyl group (OH¯) is removed by water vapour. The crystalline structure of the clay is destroyed by this dehydroxylation process, which also turns it into an amorphous, disordered state [127,128,129]. This dehydration process may occur at temperatures exceeding 500 °C, which varies from clay to clay and is influenced by factors such as heating rate and duration, atmospheric conditions, and cooling rate [130]. However, excessive heat, typically exceeding 1000 °C, may alter recrystallisation, thereby decreasing the pozzolanic activity of calcined clay [38]. Table 3 shows various transformations of clay when exposed to high temperatures.

Table 3.

Effect of varying temperature ranges and changes in clay properties [37,38,131].

Earlier research concentrated on thermally activating natural clays at different temperatures, observing increased rates and durations. The following sections and Table 4 present the optimal calcination temperatures and durations for various types of clays.

For Kaolin, in most cases, the optimal calcination temperature to make MK ranges from 650 °C to 800 °C. However, according to Morat and Comel [132], Calcination temperatures between 700 °C and 800 °C are thought to provide the optimum thermal activation. In contrast, temperatures above 850 °C are thought to crystallise the MK and reduce its reactivity thereafter. The study by Gutiérrez et al. [133] reported that the optimal heating temperature for kaolin was between 700 °C and 800 °C. Recent studies by Elimbi et al. [134] and Adufu et al. [135] achieved the ideal temperature for Kaolin to convert highly pozzolanic MK at 700 °C for 10 h and 3 h, respectively. Many recent studies have determined that the optimal calcination temperature for kaolin is 750 °C, with varying calcination times. Salau et al. [117] and Albidah et al. [118] reported that the optimal calcination temperature for Kaolin was 750 °C. On the other hand, Zuhua et al. [136] calcined Kaolin-Based geopolymer and reported an optimal calcination temperature of 900 °C for 6 h.

Previous research has reported a marginally higher optimal calcination temperature for Illite, ranging from 850 °C to 950 °C, compared to Kaolin. Some researchers have identified the optimal calcination temperature for Illite used as a pozzolanic material as between 850 °C and 875 °C, with a calcination time of 1 to 3 h. For instance, Luzu et al. [59] and Hu et al. [137] reported optimal calcination temperatures of 850 °C for geopolymer and Illite-based composites, with calcination times of 2 h and 1 h, respectively. The study by Dietel et al. [127] demonstrated that the optimal calcination temperature for Illite was 875 °C, with a 3-h calcination period. Buchwald et al. [138] thermally treat illite at 550–950 °C for 1 h. This study observed a dramatic decrease in pozzolanic activity, accompanied by a lower Si-Al dissolution rate, at temperatures between 550 °C and 650 °C. By contrast, a trend of increased dissolution was observed from 750 °C to 950 °C. Similarly, Bonavetti et al. [120] and Seiffarth et al. [139] reported that the optimal calcination temperature for Illite-OPC-based composites was 950 °C for 1 h and 30 min, respectively.

It is interesting to note that most previous research has determined the optimal calcination temperature for Bentonite to be 800 °C, with calcination periods ranging from 3 to 4 h. Waqas et al. [140] calcined Bentonite at 800 °C for 3 h and reported sufficient geopolymerisation for a fly ash-based geopolymer with polypropylene fibres (PPF). Laidani et al. [141] reported that superior pozzolanic reactivity was observed when Bentonite was calcined at 800 °C for 4 h, and that up to 15% replacement of OPC with calcined Bentonite resulted in higher mechanical performance. Fode et al. [142], Reddy et al. [143] and Garg et al. [144] obtained the highest pozzolanic reactivity when OPC-based Bentonite was calcined at 800 °C. However, Ahmad et al. [102] achieved the highest pozzolanic reactivity for Bentonite calcined at 500 °C. For Halloysite, the optimal calcination temperature has been reported to be between 750 °C and 800 °C, with a calcination period of 2 to 3 h. Zhang et al. [145] demonstrated that 750 °C was the optimal temperature for achieving extensive dehydroxylation for Halloysite. Another study by Zhang et al. [146], Yu et al. [147] and MacKenzie et al. [148] also recommended that the optimal calcination temperature for Halloysite to achieve extensive geopolymerisation was 750 °C for 2 h. In contrast, Haw et al. [105] and Ranjbar et al. [149] reported optimal calcination temperatures of 800 °C for 3 h and 2 h, respectively.

Previous research indicates that the ideal calcination temperature for Palygorskite is 700–800 °C, with a duration of 1–3 h. Poussardin et al. [82] reported that Palygorskite calcined at 800 °C for 1 h exhibited the highest pozzolanic reactivity. Whereas Georgopoulos [150] and Hamid et al. [151] reported, at 750 °C, Palygorskite exhibited the highest pozzolanic reactivity in both OPC and geopolymer composites. Limited research has shown that the optimal calcination temperature for Sepiolite is between 800 °C and 900 °C. The study by Wu et al. [152] attributed the highest pozzolanic activity to the Sepiolite samples calcined at 800 °C. Another study by Saka et al. [153] reported that Sepiolite calcined at 900 °C, and replaced with 10% OPC, exhibited superior mechanical properties in the presence of 3% glass fibre.

To summarise the above discussion, it is evident that calcination activates all types of clays at varying temperatures and durations. This temperature variation might be related to the clay’s crystal structure. It is worth noting that 1:1 clays, such as Kaolin and Halloysite, require an optimal temperature range of 700 °C to 800 °C. Conversely, 2:1 clays, such as Illite, Bentonite, Palygorskite, and Sepiolite, require temperatures of 850 °C to 950 °C for complete dehydroxylation. For 1:1 clays, a relatively lower temperature for complete dehydroxylation can be attributed to the single sheet of silicon tetrahedra that encloses a single octahedral aluminium unit. 2:1 clays have two sheets of silicon tetrahedra and a single octahedral magnesium or aluminium, which requires more energy to remove the internal bound water and break the Si-Al bond than 1:1 clays do.

Table 4.

Optimal calcination temperature, duration, and increased rate of temperature for different types of clays.

Table 4.

Optimal calcination temperature, duration, and increased rate of temperature for different types of clays.

| Type of Clay | Optimal Temperature (°C) | Duration of Calcination (Hours)/Rate of Heat Increment | Remarks | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kaolinite | 650–850 | 3 | Kaolin with low alunite content was optimal at 650 °C, whereas kaolin with high alunite content required 850 °C. | [154] |

| 700–800 | 1 (2 °C/min) | Due to its high pozzolanic index, kaolin was transformed into metakaolin. | [133] | |

| 750 | 1 | Kaolin clay heated to this temperature and for this duration showed the highest strength when replaced with 10% cement. | [117] | |

| 750 | 3 | Metakaolin-based geopolymer concrete exhibits superior mechanical performance when heated to this specified temperature for the specified duration. | [118] | |

| 750 | 10 (2 °C/min) | Raw kaolin was heated to the specified temperature for the specified duration, converting it into a highly pozzolanic material. This pozzolanic clay was replaced with fly ash to make geopolymer composites. | [155] | |

| 700 | 10 (5 °C/min) | Above 700 °C, calcined kaolin began to lose its pozzolanic reactivity in geopolymer cement. | [134] | |

| 700 | 3 (10 °C/min) | To make geopolymer concrete, a variety of calcium-rich additives, including calcium carbide residue, lime, and OPC, were partially replaced with calcined kaolin. | [135] | |

| 600 | 1 | Kaolin clay heated to this temperature and for this duration showed mechanical performance when cured at 60 °C for 24 h. | [156] | |

| 750 | 1 | Kaolin heated at this temperature exhibited optimal pozzolanic activity when partially replaced with OPC. When heated at 850 °C, it displayed reduced pozzolanic activity due to recrystallisation. | [157] | |

| 650 | 1 (25 °C/min) | At this temperature, kaolin exhibited the highest dehydroxylation rate (>85%). | [158] | |

| 900 | 6 | At this temperature, kaolin exhibited the highest reactivity, and above it, reactivity sharply declined. | [136] | |

| Illite | 950 | 1 | Illite calcined at this temperature became a highly reactive geopolymer binder. | [138] |

| 950 | 1 | Calcined illite and limestone fillers were partially replaced with OPC. | [120] | |

| 950 | 0.5 | A higher soluble Si/Al ratio after treatment at 950 °C could improve the mechanical properties of the geopolymer binders. | [139] | |

| 850 | 2 | After treatment at this temperature, the illite clay became sufficiently pozzolanic for use in geopolymer composites. | [59] | |

| 875 | 3 | Achieved sufficient geopolymerisation and enhanced mechanical performance. | [119] | |

| 850 | 1 | An optimal quantity of a reactive and amorphous aluminosilicate precursor material has been observed at 850 °C. | [137] | |

| Bentonite | 800 | 3 | Bentonite thermally treated at this temperature demonstrated adequate pozzolanic performance, enabling it to replace 10% of the fly ash in geopolymer concrete. | [140] |

| 800 | 4 | Thermally activated bentonite partially substituted with OPC. A replacement rate of up to 15% was optimal for self-compacting concrete. | [141] | |

| 500 | 3 | Up to 30% replacement with OPC showed standard pozzolanic activity. | [102] | |

| 800 | 3 | A 20% replacement of OPC with calcined bentonite at 800 °C showed the highest pozzolanic activity compared to the replacements at 400 °C and 600 °C. | [142] | |

| 800 | - | A 20% replacement of OPC with calcined bentonite at 800 °C showed the highest pozzolanic activity compared to calcined bentonite at 700 °C. | [143] | |

| 800 | - | When calcined at this temperature, the maximum pozzolanic reactivity was observed with 30% replacement of OPC. | [144] | |

| Halloysite | 800 | 3 | Optimal pozzolanic activity was observed when the material was calcined at this temperature, with a 10% OPC replacement. | [105] |

| 750–850 | 2 | The highest geopolymerisation was observed at calcination temperatures between 750 °C and 850 °C, compared to 450 °C, 650 °C, and 1000 °C. | [145] | |

| 750 | 2 | Halloysite calcined at this temperature was able to participate in geopolymerisation along with fly ash and blast furnace slag. | [147] | |

| 750 | 2 | The highest level of geopolymerisation was observed at 750 °C, while the lowest was at 1000 °C. | [146] | |

| 800 | 2 | Halloysite calcined at this temperature exhibited the best pozzolanic activity in 3D-printed geopolymer composites. | [149] | |

| 750 | 1.6 | The highest pozzolanic reactivity was achieved when halloysite was calcined at 750 °C, and it sharply declined at 800 °C. | [148] | |

| Palygorskite | 800 | 1 (300 °C/h) | Enhanced pozzolanic reactivity was exhibited when 10% of the OPC was replaced. | [79] |

| 800 | 1 (5 °C/min) | Complete amorphisation and optimal pozzolanic activity were achieved when 20% of calcined palygorskite was replaced with OPC. | [82] | |

| 750 | 3 | The highest pozzolanic reactivity was observed when OPC replaced 20% of calcined palygorskite. | [150] | |

| 700 | 10 °C/min | Palygorskite calcined at 700 °C exhibited optimal pozzolanic reactivity in geopolymer. | [151] | |

| Sepiolite | 800 | 0.5 | Sepiolite calcined at this temperature exhibited optimal pozzolanic reactivity when used as a 20% replacement of OPC. | [152] |

| 900 | - | Optimal pozzolanic activity was observed with a 5% OPC replacement. | [153] | |

| 830 | - | Significant pozzolanic activity was observed when sepiolite was calcined at 830 °C, while sepiolite calcined at 370 °C and 570 °C showed no pozzolanic activity. | [120] |

3.2. Mechanical Activation

Mechanical activation of clay minerals through high-speed grinding, also known as mechanochemical activation, reduces the crystallinity of certain clays by increasing their specific surface area. Through dihydroxylation, mechanochemical milling causes the clay to fully delaminate, increasing the amount of water absorbed on its surface [159]. The chemical and physical alterations induced by the mechanochemical activation process enhance the pozzolanic reactivity of the treated clay, potentially surpassing that achieved through thermal treatment at equivalent cement replacement levels [160]. This mechanochemical activation results in a finer particle size, increasing surface area and facilitating the faster dissolution of Si and Al ions and their participation in the pozzolanic reaction [161]. However, the current research data reveal significant limitations of this activation method, whereas most previous studies have focused on thermal treatment. Among this limited knowledge, it is notable that mechanical activation proved effective for the 1:1 structured Kaolin clay, while other 1:1 clays, such as Halloysite, have not been extensively investigated. Moreover, using 2:1 clays, such as Illite, Bentonite, Palygorskite, and Sepiolite, may offer advantages over kaolinite (a 1:1 mineral) due to the additional silica layer, which could promote the formation of more calcium silicate hydrate [162]. The following sections and Table 5 describe the mechanical activation method used in previous research to activate different types of clays.

Clay activation through mechanical grinding depends on several factors, including grinding speed, the ratio of grinding body to clay powder, and the duration of the grinding process. To activate the clay, most previous research has employed ball grinding, maintaining a ball-to-powder ratio of 10–25, with grinding speeds of 300–600 rpm and varying grinding durations, depending on the ball diameter and grinding speed. Balczár et al. [163] demonstrated that early 100% amorphisation and the highest pozzolanic reactivity were observed with a ball-to-powder ratio of 11, a grind speed of 400 rpm, and a grinding duration of 240 min. Tole et al. [34] achieve optimal pozzolanic reactivity in kaolin clay by maintaining a ball-to-powder ratio of 25, using 3 mm stainless steel balls, and grinding for 20 min at 500 rpm. A higher grinding duration caused agglomeration.

In contrast, another study [164] reduced the grinding speed from 500 rpm to 300 rpm, increased the grinding duration from 20 min to 60 min, and decreased the ball-to-powder ratio from 25 to 10 mm diameter balls, to achieve optimal pozzolanic activity. However, Hounsi et al. [121] further reduced the grinding speed to 250 rpm and the ball-to-powder ratio to 1.56 by using balls of different diameters (19 mm and 10 mm) and achieved the highest amorphisation and pozzolanic reactivity of Kaolin clay. On the other hand, Ilić et al. [165] used the lowest grinding speed of 46 rpm and reported partial amorphisation.

Luzu et al. [59] achieved the optimal pozzolanic reactivity of Illite clay, maintaining a ball-to-powder ratio of 15, using 30 mm stainless balls, and grinding for 240 min at 400 rpm. In contrast, Zhao et al. [122] increased the grinding speed from 400 rpm to 500 rpm, decreased the grinding time from 240 min to 30 min, and raised the ball-to-powder ratio from 15 to 20 using 10 mm diameter balls. This study reported the highest dehydroxylation and pozzolanic reactivity of Illite up to 40% replacement of cement.

For Bentonite clay, Baki et al. [166] achieved optimal pozzolanic reactivity at a grinding speed of 500 rpm, using 10 mm zirconia balls, maintaining a ball-to-powder ratio of 10, and grinding for 60 min. Whereas Kovalchuk [167] reported the highest amorphisation of Bentonite using a grinding speed of 300 rpm, employing 20 mm Si3N4 balls, maintaining a ball-to-powder ratio of 10, and a grinding duration of 120 min.

MacKenzie et al. [148] employed two mechanical treatments for Halloysite: ball grinding and vibratory ring milling. For ball grinding, the grinding speed was 400 rpm, and the grinding duration was 1200 min. This study found a significant reduction in pozzolanic reactivity during ball grinding compared to vibratory ring milling. For Palygorskite clay, Georgopoulos et al. [168] reported the highest pozzolanic reactivity when ground for 15 min at 600 rpm. Limited research indicates that Sepiolite clay can also be pozzolanic upon mechanochemical activation. Tunç et al. [169] reported a 2.4% increase in pozzolanic reactivity after 60 min of grinding compared to 30 min, with a grinding speed of 600 rpm.

In conclusion, the documentation above demonstrates that mechanical ball grinding is an effective treatment method for converting crystal clay into highly pozzolanic amorphous clay. However, this activation method does not depend on the clay’s crystal structure (e.g., 1:1 or 2:1). Nevertheless, its efficiency depends on specific parameters, including grinding speed, duration, and the ball-to-clay ratio. It is advisable to optimise these parameters to obtain a highly pozzolanic clay. For instance, if the grinding speed and ball-to-clay ratio are high, the grinding duration should be decreased. Otherwise, the amorphous clay will agglomerate, reducing its specific surface area.

Table 5.

Clay activation through mechanical grinding (optimal condition).

Table 5.

Clay activation through mechanical grinding (optimal condition).

| Type of Clay | Grinding Body | Ball/Powder | Grinding Speed (rpm) and Time (min) | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kaolin | Zirconia ball of 10 mm in diameter | 11 | 400 rpm and 240 min | A nearly 100% degree of amorphisation and the highest strength were obtained. | [163] |

| Stainless steel ball of 3 mm in diameter | 25 | 500 rpm and 20 min | The highest amorphisation and strength were exhibited. | [34] | |

| Zirconia ball of 10 mm in diameter | 20 | 300 rpm and 60 min | Most of the hydroxyl groups were removed, and the kaolin was highly amorphous. | [164] | |

| 10 balls of 19 mm and five balls of 10 mm in diameter | 1.56 | 250 rpm and 60 min | Optimal activation was attained for geopolymer-based mortar. | [121] | |

| Zirconia ball of 10 mm in diameter | 20 | 350 rpm and 120 min | Exhibited optimal amorphisation and pozzolanic reactivity | [170] | |

| Steel balls ranging from 20 to 60 mm in diameter | 10 | 46 rpm and 1200 min | Kaolin was partially amorphised, and the specific surface area increased up to 31% at 20 h of grinding compared to 10 h. | [165] | |

| Illite | 30 mm diameter ball | 15 | 400 rpm and 240 min | The highest pozzolanic reactivity and strength were obtained. | [59] |

| Balls of 10 mm diameter | 20 | 500 rpm and 30 min | Optimal pozzolanic reactivity and strength increased by up to 40% with OPC replacement. | [122] | |

| Bentonite | Zirconia ball of 10 mm in diameter | 10 | 500 rpm and 60 min | Optimal hydroxylation and amorphisation occurred. A 20% replacement of OPC with activated bentonite resulted in an over 90% strength activity index. | [166] |

| Si3N4 balls of 20 mm in diameter | 10 | 300 rpm and 120 min | The particle size was considerably decreased. Optimal crystal structures were converted to amorphous states. | [167] | |

| Halloysite | Two types of grinding machines were used: (1) a planetary ball mill with 3 mm Zirconia balls, and (2) an energetic vibratory ring mill equipped with a tungsten carbide bowl and rings. | 50 (for planetary ball grinding) | 400 rpm and 1200 min (for planetary ball grinding), 15 min (vibratory ring mill) | Halloysite ground in a planetary grinder showed significantly lower pozzolanic reactivity than that ground in a vibratory ring mill grinder. | [148] |

| Palygorskite | Zirconia balls of 4–5 mm in diameter | 60 and 64 | 600 rpm and 15 min | The highest pozzolanic reactivity was achieved when palygorskite was ground at 600 rpm for 15 min. Whereas at 30 min, 45 min, and 60 min, pozzolanic reactivity sharply declined at the same grinding speed. | [168] |

| Sepiolite | Tungsten carbide balls of 10 mm in diameter | 25 | 600 rpm and 60 min | The highest degree of amorphisation occurred at 60 min, reaching 92.3%. In comparison, at 30 min, it was 89.9% with the same grinding speed. | [169] |

3.3. Chemical Activation

Limited Research has employed chemical activation in addition to calcination and mechanical activation [123,124,125,126]. For clays containing 73% montmorillonite that were obtained from an area near London, Ayati et al. [124] used acid activation. This study employed 5 M hydrochloric acid at 20 °C and 90 °C, with treatment times ranging from 1 h to 21 days. The authors obtained the best pozzolanic activity and 93% amorphous clays (25% cement replacement with clays) by treating clays with 5 M hydrochloric acid for 8 h at 90 °C. Additionally, they found that smectite clays exhibit superior pozzolanic reactivity upon acid activation compared to calcination. Noor-ul-Amin et al. [126] used aqueous calcium chloride in varying concentrations (1–6%) as a chemical activator for Pakistani mine-derived clays. The study did not provide a detailed description of the clay’s mineral composition. However, the authors found that natural clays could be successfully activated using a 4% aqueous calcium chloride solution, replacing 20% of the cement. However, it was observed that a high concentration of free Cl− existed in the pore solution. Therefore, due to the possibility of corrosion, the authors noted that this activation technique would not be suitable for concrete applications with embedded steel [126] Mwiti et al. [125] activated pre-calcined natural clays from Kenya using 0.5 M sodium sulphate. Additionally, the study’s clay mineral composition was unavailable. The authors produced a blended cement with 50% cement replacement and enhanced its mechanical performance by activating it with 0.5 M sodium sulphate.

3.4. Importance of PSD and SSD in Clay Treatment and Concrete Performance

Particle size distribution (PSD) and specific surface area (SSA) are critical parameters influencing the efficacy of clay treatment and the performance of clay-based geopolymer concrete. Calcination during processing alters the clay’s mineral structure, thereby enhancing its pozzolanic reactivity. Additionally, ball milling increases SSA by reducing particle size and dispersing agglomerates. Bai et al. [171] demonstrated that extended grinding durations yield a greater abundance of ultrafine particles, thereby enhancing pozzolanic activity and mechanical strength. Elevated calcination temperatures augment reactivity; however, they may concurrently diminish fluidity due to particle agglomeration. SSA directly affects water demand and workability; an increase in SSA enlarges the reactive surface area but necessitates additional water, which can adversely impact workability if not adequately controlled. Muzenda et al. [172] noted that SSA exerted a greater influence on early hydration and compressive strength than metakaolin content, with SSA values ranging from 14 to 45 m2/g depending on clay mineralogy and treatment methods. Calcination, especially at optimal temperatures, alters the mineral phase and may induce agglomeration, thereby reducing the SSA unless counteracted through grinding. Clays such as kaolin and halloysite respond effectively to thermal activation, whereas bentonite, illite, palygorskite, and sepiolite may benefit more from mechanical or chemical activation [173]. Again, PSD influences packing density and rheology; finer particles enhance strength but diminish fluidity, whereas a broader PSD improves workability [174]. Therefore, it is essential to adjust PSD and SSA through appropriate treatment methods to optimise the reactivity and mechanical properties of clay-GPC systems.

4. Effect of Clay on Concrete Workability

The workability of concrete is severely affected by the presence of clay particles. The high specific surface areas and finer particle sizes of clay minerals increase water demand and reduce workability [175]. The following sections and Table 6 show the impact of various types of clays on concrete.

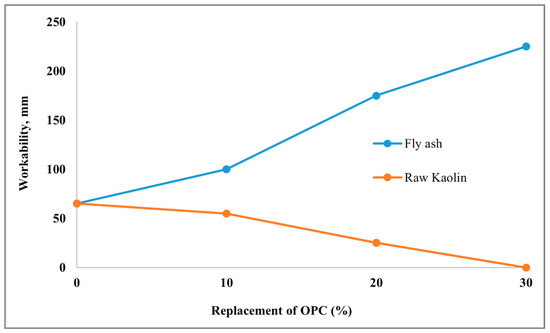

Ghais et al. [176] conducted a comparative study to evaluate the impact of fly ash and raw Kaolin clay on the replacement of 10% to 30% of OPC. For the fly ash-replaced specimen, a significant increase in the slump value has been observed. On the other hand, a dramatic decrease in slump has been observed for clay (Figure 2). The increase in the slump of fly ash can be attributed to its spherical shape, which improves workability. Whereas clay particles increase the water demand and, due to their plastic nature, significantly reduce the workability. The study by Salau et al. [117] replaced 10%, 20%, and 30% of calcined clay with OPC, maintaining a water-to-binder ratio (w/b) of 0.4. This study demonstrated high workability with a compacting factor of 0.95 for a 10% clay replacement, and medium workability for 20% and 30% clay replacements, with compacting factors of 0.92. The decrease in workability for the 20% and 30% clay inclusion was due to the high water demand created by the clay particles. However, this study suggested that a w/b of 0.5 might be suitable for achieving high workability with 30% replacement of OPC with calcined kaolin clay.

Figure 2.

Effect of fly ash and raw Kaolin on the workability [177].

To investigate the flowability of Illite-based mortar, Bonavetti et al. [120] calcined the Illite clay at 750 °C for 1 h, and 35% and 20of the limestone filler was replaced with OPC. The results showed that flowability decreased by 8% and 5% for the 35% clay and 20% filler, respectively. A study by Zhao et al. [122] investigated the flowability of Illite-rich waste shalusing calcination and mechanical activation methods to compare and replace 20%, 30%, and 40% of the waste with OPC, while maintaining a water-to-binder ratio of 0.485. The obtained results showed that, compared to mechanically activated Illite-rich samples, thermally activated samples had a more negative impact on flowability, resulting in a 30.8% reduction in flowability for 40% OPC replacement compared to mechanical activation. This greater reduction in flow for thermally activated samples can be linked to the increased water demand resulting from the porous structures caused by calcination [178].

The study by Waqas et al. [140] investigated the combined effects of raw and calcined Bentonite (800 °C), with and without polypropylene fibres (PPF), on the workability of fly ash-based geopolymer concrete. The results demonstrated that raw clay exhibited an almost 10% reduction in slump compared to calcined clay. This reduction in slump can be attributed to the higher specific surface area of the fly ash and its higher water demand. However, a slight increase in the slump of the calcined clay may be due to a decrease in surface area during calcination. This similar trend was also mentioned in the other research [179]. However, the addition of PPF further reduced the slump by up to 37% due to internal friction [180]. This phenomenon is consistent with typical findings in clay activation, in which thermal treatment can cause interlayer spaces to collapse and reduce the number of active sites, resulting in a less absorptive or workable material in fresh concrete mixes [63].

In contrast, Reddy et al. [143] compared Bentonite at room temperature (RT) and calcined at 700 °C and 800 °C, replacing OPC by 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, 25%, and 30% by weight. The results obtained showed a decreasing trend in the slump value with increasing Bentonite content, and this decrease became more pronounced with higher calcination temperatures. This study indicated that higher calcination temperatures increased water demand, exceeding that of the RT Bentonite. This finding contrasts with that of Waqas et al. [140], who reported that raw Bentonite concrete had a lower slump than calcined concrete. The difference in slump behaviour between calcined bentonite observed by Waqas et al. [140] and Reddy et al. [143] can be explained by the nature and extent of calcination and its impact on bentonite’s physical and chemical properties. Moderate calcination, as reported by Waqas et al. [140], may reduce surface area due to partial dehydroxylation and collapse of interlayer spaces, thereby lowering water demand and improving workability, resulting in a slight increase in slump. In contrast, intense calcination at higher temperatures (700–800 °C), as studied by Reddy et al. [143] can cause structural disruption and increased internal porosity, creating more reactive sites that absorb water more aggressively, thereby reducing slump. Furthermore, the replacement level of Bentonite and the interaction with other mix components, such as fly ash and polypropylene fibres, significantly influence the rheological behaviour of the concrete, making direct comparisons between studies complex and context-dependent.

To examine the impact of raw Halloysite on the fresh properties of cement mortar, Dungca et al. [181] replaced 2.5% Halloysite nano clay (HNCL) with OPC by weight, maintaining a w/b ratio of 0.58. This study reported a 33.33% reduction in slump for 2.5% HNCL compared to the control sample. This decrease in workability is associated with the effect of clay particles on the water distribution within the cement mortar.

The study by Georgopoulos et al. examined the slump of mortar made with OPC and calcined Palygorskite (750 °C for 3 h) at a w/b ratio of 0.485. Replacing 20% of the calcined clay with OPC reduced the slump value, primarily due to its high water absorption capacity. The authors suggested that the required slump value can be achieved by increasing the superplasticiser dose while maintaining a constant water-to-binder ratio.

Jemina et al. [88] replaced OPC with 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, and 25 sepiolite by weight, and replaced 10%, 20%, 30%, 40%, and 50% of the coarse aggregate with recycled aggregate. This study reported that clay negatively impacts the fresh properties by increasing water demand. This study maintained the target fresh properties by expanding the superplasticiser dosage by 32.7%, from 5% to 25% of sepiolite inclusion, while keeping the water-to-binder ratio constant at 0.47.

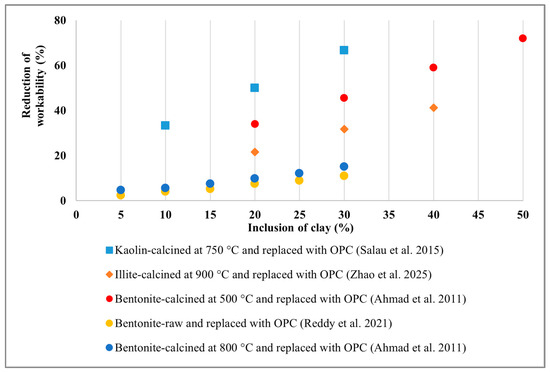

From the above discussion, it is recognised that including any type of clay, whether raw or treated, adversely affects workability due to its high water demand. Figure 3 illustrates the relationship between the reduced workability trend and clay inclusion. Workability started to decline as the clay inclusion rate increased. An almost 80% reduction in workability has been reported for a 50% replacement of Bentonite clay, and other clays exhibited a similar trend. However, up to 30% inclusion of Bentonite, either raw or calcined, showed minimal reduction in workability. By comparing the negative impacts of calcinated clay and mechanically activated clay, limited research suggests that calcinated clay generates a higher water demand than mechanically activated clay, due to its porous structure resulting from calcination. However, this statement is not sufficiently established due to insufficient evidence. On the other hand, some research statements [140] contradict each other regarding the workability assessment of raw and calcined Bentonite. Therefore, a more thorough investigation should be conducted in the future.

Figure 3.

Relationship between concrete workability and clay inclusion [102,117,122,143].

Table 6.

Effect of different types of clays on the workability of concrete.

Table 6.

Effect of different types of clays on the workability of concrete.

| Type of Clay | Pre-Treatment or Raw Condition of the Clay | Type of Composites | % of Clay Inclusion | Alkali/Binder (a/b) & Water/Binder (w/b) | Types of Workability Tests Performed | Remarks | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kaolin | Raw | OPC with FA, OPC with kaolin (concrete) | 0%, 10%,20% and 30% OPC replaced by FA and kaolin | w/b 0.4 | Slump test | Inclusion of up to 30% fly ash significantly increased the slump value. The inclusion of kaolin from 10% to 30% dramatically reduced workability due to higher water demand and plastic behaviour. | [176] |

| Calcined | OPC with clay (concrete) | 0%, 10%,20% and 30% OPC replaced by clay | w/b 0.4 | Slump test | From 0% to 30%, kaolin calcined at 750 °C for 1 h, exhibited a medium slump value. The author suggested an appropriate w/b of 0.5 for higher workability. | [117] | |

| Illite | Calcined | OPC with calcined clay (CC) and limestone filler (LF) (mortar) | 0%, 20%, LF and 35% CC with OPC | w/b 0.5 | flow | Mortar with 35% CC and 20% LF, reduced slump flow by 8% and 5%, respectively, compared to the reference sample. | [120] |

| Calcined and mechanically activated | OPC with illite-rich waste shale (mortar) | 0%, 20%, 30% and 40% OPC replaced by clay | w/b 0.485 | flow | For calcined clay, the mortar’s flow decreased from 21.6% to 41.2% when 20% to 40% of the clay was replaced with cement, compared to the control mix, due to the high-water demand. On the other hand, the mechanically activated clay exhibited a reduced reduction in flow, which is 8.5% to 10.4% compared to the reference sample. | [122] | |

| Bentonite | Raw and calcined | Fly ash (FA) with raw and calcined clay, polypropylene fibre (PPF) (geopolymer concrete) | 0%, 10% FA replaced with raw and calcined clay. 0.5%, 0.75% and 1% PPF. | a/b 0.4 | slump | A reduced trend of slump value was observed for raw clay compared to calcined clay. Additionally, the inclusion of PPF negatively impacted workability due to internal friction. | [140] |

| Raw | OPC, bentonite, recycled aggregate (RAC) and natural aggregate (NAC) (concrete) | 0%, 5%, 10%, 15% and 20% clay replaced by OPC. 100% NAC and RAC used | w/b 0.5, 0.53, 0.56, 0.59, 0.63 | Slump | The inclusion of bentonite negatively affected the workability of both RAC and NAC concrete, due to bentonite’s higher surface area compared to OPC. However, the addition of superplasticiser improved workability. | [182] | |

| Calcined | OPC replaced by calcined clay (self-compacting concrete) | 0%, 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, 25%, and 30% OPC replaced by clay | w/b 0.4 | Slump flow, V-funnel and T-500 | The slump value decreased with increasing clay content in the concrete due to enhanced viscosity; therefore, the superplasticiser (SP) dose needed to be increased to achieve the required slump. For 25% and 30% of clay, SP doses were 1.2% and 1.67%, respectively. | [141] | |

| Calcined | OPC replaced by calcined clay (mortar) | 0%, 20%, 25%, 30%, 40% and 50% OPC replaced by clay | w/b 0.55 | Slump | The slump value was significantly reduced by almost 31.76% to 70.50% for 20% to 50% clay inclusion compared to the reference sample. This decrease in slump value is attributed to the higher water demand generated by the clay. | [102] | |

| Room temperature and calcined | OPC replaced by calcined clay (mortar) | 0%, 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, 25%, and 30% OPC replaced by clay | - | Slump | A reduced trend of workability was observed with the inclusion of both types of clays. However, calcined clay showed a greater reduction in workability than room-temperature clay due to its higher water absorption capacity. | [143] | |

| Raw | OPC replaced raw clay (concrete) | 0%, 3%, 6%, 9%, 12%, 18%, and 21% OPC replaced by clay | w/b 0.58 | Slump | The slump values steadily decreased as the clay inclusion increased. This downward trend is due to the clay’s larger surface area. | [103] | |

| Halloysite | Raw | OPC replaced raw clay (mortar) | 0%, 2.5% OPC replaced by clay | w/b 0.58 | Slump | A 33.33% reduction in the slump value was observed for the 2.5% halloysite clay sample compared to the control sample. | [181] |

| Palygorskite | Calcined | OPC replaced calcined clay (mortar) | 0% and 20% OPC replaced by clay | w/b 0.485 | Slump | A reduced trend in slump value was observed with the inclusion of calcined clay, due to its high water-absorption capacity. The required slump value can be maintained by increasing the superplasticiser dose while maintaining a constant water-to-binder (w/b) ratio. | [150] |

| Sepiolite | - | OPC replaced clay, and coarse aggregate (CA) was replaced by recycled coarse aggregate (RCA) (self-compacting concrete) | 0%, 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, and 25% OPC replaced by clay. 0%, 10%, 20%, 30%, 40%, and 50% CA replaced by RCA. | w/b 0.47 | Slump flow, T50, J-ring height, V-funnel flow, L-box | A combination of 41.78% fly ash (by weight of OPC) and sepiolite powder maintained workability within the required limits for all replacement levels by adjusting plasticiser dose. The highest flow value was achieved with a 25% clay and 50% RCA mixture. | [88] |

5. Effect of Clay on the Mechanical Properties of Concrete

The effect of raw and treated (primarily calcined) clays on the performance of cement-based materials has been evidenced by pioneering studies. The optimally calcined [155] and mechanically ground [163] clays improve the mechanical strength of concrete, whereas raw clay reduces the strength [34]. Since raw clays are crystalline, a dramatic reduction in strength has been observed when OPC replaces them. Although some studies reported an increase in strength up to a specific limit, thereafter, strength reduced. This increase may have resulted from the filling effect of fine clay particles [142]. However, some studies, especially those on Bentonite [183], have shown that a high amount of raw clay inclusion can increase strength due to the pozzolanic reactivity of Bentonite clay. These controversial results for clay must be highlighted in future research. However, most previous research has achieved increased mechanical performance by employing optimal calcination. During calcination, the clay’s crystalline structure is destroyed through dehydroxylation, transforming it into an amorphous, disordered state that renders it highly reactive in the cement and alkaline environment [127,128,129]. While limited research also indicated a similar increase in strength during mechanical activation. Mechanochemical activation involves reducing the crystallinity of certain clays by increasing their specific surface area through high-speed mechanical grinding [159]. The following sections illustrates the impact of raw and treated clays on the mechanical performance of concrete.

5.1. Compressive Strength

Most previous research incorporated calcination treatment to activate Kaolin clay. The study by Salau et al. [117] reports a greater decrease in strength when Kaolin was calcined above 750 °C. This decline in strength was due to the recrystallisation of the clay and the reduction of pozzolanic reactivity. In comparison, Boakye and Khorami [155] calcined clay at 750 °C for 2 h. Results showed that the highest compressive strength was achieved at a 20% replacement level, and that from 40% to 100% all samples demonstrated improved strength, indicating that the calcination process enhanced geopolymerisation. Again, the addition of calcium-rich additives also enhances geopolymerisation as shown by the study of Adufu et al. [135]. This study revealed that adding calcium-rich additives, especially quick lime (QLM), significantly enhanced geopolymerisation, and replacing up to 10% of calcined Kaolin with QLM improved compressive strength by 77.9% compared to control samples. However, limited research has examined the effect of mechanical activation on the compressive strength of Kaolin. For instance, Balczár et al. [163] demonstrated that the highest compressive strength (55.6 MPa) of mechanochemically activated samples surpassed that of the best thermally activated sample (43.0 MPa). Another study by Tole et al. [34] showed that raw Kaolin did not exhibit any compressive strength due to its lack of pozzolanic reactivity. Mechanically activated Kaolin exhibited high compressive strength.

Most previous research on Illite employed thermal activation to enhance its pozzolanic properties. Bonavetti et al. [120] calcined Illite clay at 750 °C for 1 h, with 35% of the OPC replaced by clay. The obtained results showed a reduction in strength. However, the addition of limestone filler improved strength. Fernández et al. [40] calcined the Illite clay at 600 °C for 1 h and obtained a reduction in strength of up to 36% for a 30% replacement of OPC. Another study by Eliche-Quesada et al. [183] revealed that up to 50% replacement of MK by Illite clay significantly enhanced the compressive strength by 66% and 62% at 28 days and 90 days of ambient curing, respectively. This increase in strength may be attributed to both the altered properties of the formed gel and the marginal increase in bulk density. The Si-O-Al bonds in the geopolymer gel diminished as the Si/Al ratio increased, whereas the Si-O-Si connections became more prominent. This phenomenon contributed to the gel’s enhanced mechanical strength, as the Si-O bond is inherently stronger than the Al-O bond. Moreover, the C-A-S-H gel was formed in the presence of calcium within the clay matrix [184]. A further investigation by Zhao et al. [122] revealed that mechanical activation significantly enhanced the compressive strength of Illite by altering its surface morphology, resulting in a synergistic effect due to high-speed grinding.

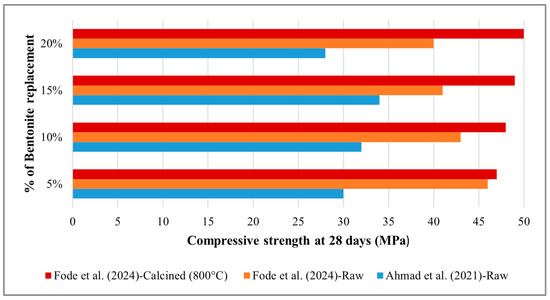

The study by Waqas et al. [140] demonstrated that the compressive strength increased by 10% for raw bentonite-GPC and by 18% for the calcined mixtures compared to the control samples. Adding PPF further enhanced the compressive strength. Another study conducted by Karthikeyan [185] further examined the mechanical performance of raw Bentonite by substituting 25%, 30%, and 35% by weight with OPC. The results indicated a 14.10% reduction in compressive strength for a 25% inclusion. Conversely, an increase of 19.3% was observed at 30% inclusion, followed by a further decrease of 61.72% at 35% inclusion, relative to the control mix. Although this study recommended a 20% to 30% replacement of raw Bentonite as sustainable, the strength reduction observed with a 25% inclusion of Bentonite is controversial. Another study by Ahmad et al. [177] reported a 7.14% reduction in strength with a 20% replacement of raw Bentonite with OPC and suggested that a 15% replacement might be optimal. At the same time, Fode et al. [142] obtained the opposite result in comparison to Ahmad et al. [177]. This study observed a slight increase in compressive strength with 5% raw Bentonite replacement, then a continuous decrease from 10% to 20% replacement. Conversely, calcined clay showed an increasing trend in compressive strength with increasing OPC replacement from 5% to 20%. Figure 4 illustrates the opposite trend in compressive strength when incorporating raw Bentonite, as observed by Ahmad et al. [177] and Fode et al. [142]. This research found that raw Bentonite does not exhibit pozzolanic properties unless calcined. These findings are inconsistent with those of prior research conducted by Karthikeyan et al. [185], Ahmad et al. [177] and Liu et al. [186]. These variations in compressive strength across studies using raw and calcined bentonite are attributable to several factors. Waqas et al. [140] documented enhancements in strength with both variants, particularly with the inclusion of PPF, likely owing to improved crack resistance and matrix densification. Conversely, Karthikeyan [185] observed inconsistent outcomes with raw Bentonite, noting a reduction in strength at a 25% replacement level and improvements at 30%, potentially due to optimal particle packing or filler effects. Ahmad et al. [177] and Fode et al. [142] demonstrated conflicting trends: Ahmad et al. [177] observed a 7.14% decrease at 20% replacement and recommended 15% as optimal, whereas Fode et al. [142] identified initial strength improvements at 5%, followed by declines, suggesting that raw bentonite may lack pozzolanic activity unless subjected to calcination. These discrepancies may arise from differences in Bentonite source, calcination conditions, mix design, and testing methodologies, thereby highlighting the necessity for standardised evaluation procedures.

Figure 4.

Opposite trend of compressive strength of concrete containing raw Bentonite [142,177].

The study by Yu et al. [147] examined the mechanical performance of geopolymer mortar containing fly ash and GGBFS, with 1%, 2%, 4%, 6%, and 8% of calcined Halloysite (heated to 750 °C for 2 h) replacing fly ash and GGBFS. In the 2% replacement group, this study achieved the most significant increase in compressive strength after 28 days. A further investigation conducted by Zhang et al. [145] reported that Halloysite calcined at 750 °C exhibited the highest compressive strength with optimal geopolymerisation. The lowest compressive strength was observed at 1000 °C, which was attributed to recrystallisation.

Limited research has shown that the optimal calcination temperature for Palygorskite is between 750 °C and 800 °C. Poussardin et al. [79] reported that the compressive strength decreased slightly by approximately 2.5% with a 20% inclusion of calcined Palygorskite (750 °C) in OPC, which was considered negligible. Georgopoulos et al. [150] demonstrated that replacing 20% of OPC with Mg-rich calcined Palygorskite (heated to 800 °C for 1 h) resulted in a 0.96% increase in compressive strength compared to the control sample.

The study by Pu et al. [187] used raw Sepiolite clay to replace MK and fly ash in geopolymer paste. The results showed that including Sepiolite positively affected compressive strength, with the highest strength at 10% replacement; beyond that level, compressive strength began to decline due to the lack of pozzolanic material. Another study by Wu et al. [152] indicated that the optimal calcination temperature for Sepiolite was 800 °C for 30 min. This research replaced 20% of OPC with calcined Sepiolite. After 28 days, the compressive strength was nearly identical to that of the reference sample. In another investigation, Wu et al. [87] employed acid treatment to activate the Sepiolite. This study indicated that a strong acid at a higher concentration (HCl, 1 M) enhanced the strength by partially dissolving Si and Al. Nonetheless, this treatment was not as effective as calcination.

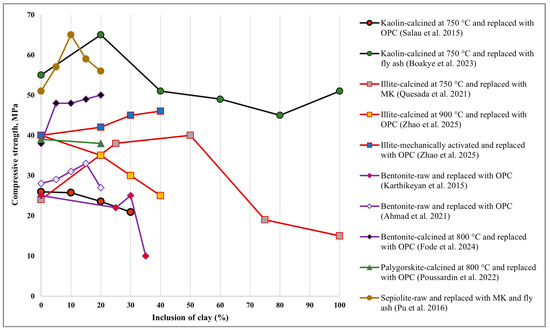

From the available literature, it is evident that the inclusion of different types of clays, either raw or treated, enhances the compressive strength up to a specific limit, beyond which the compressive strength starts to decline, as shown in Figure 5. It is recognised that calcination enhances the compressive strength of all types of clays, up to a replacement level of 20% to 40%. Limited research has shown that mechanically activated Illite can increase compressive strength by up to 50% with up to 50% replacement. It is interesting to note that raw clays, such as Sepiolite and Bentonite, also increased the compressive strength. For Sepiolite, 10% inclusion showed identical strength compared to calcined Kaolin.

Figure 5.

Effect of clays on the compressive strength of concrete [79,117,122,142,155,177,183,185,187].

On the other hand, inclusion of raw Bentonite at 15–30% increased strength. However, a 20% inclusion of calcined Bentonite showed an upward trend in compressive strength, suggesting that higher inclusions beyond 20% may be achievable with calcination. The current state of research does not clearly establish the impact of mechanical activation on different types of clay and their replacement levels. Therefore, further research is needed.

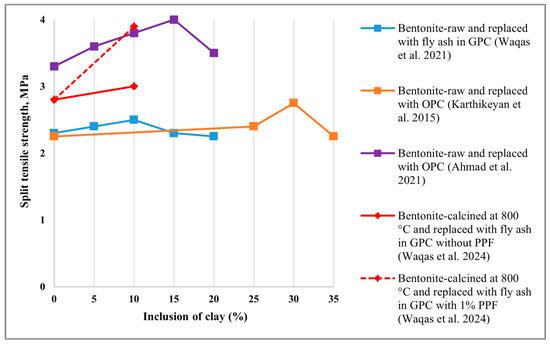

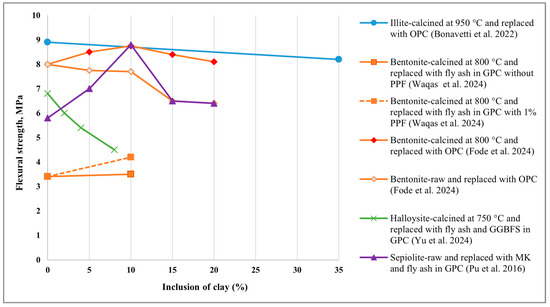

5.2. Split Tensile Strength