Evaluation of Disaster Resilience and Optimization Strategies for Villages in the Hengduan Mountains Region, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

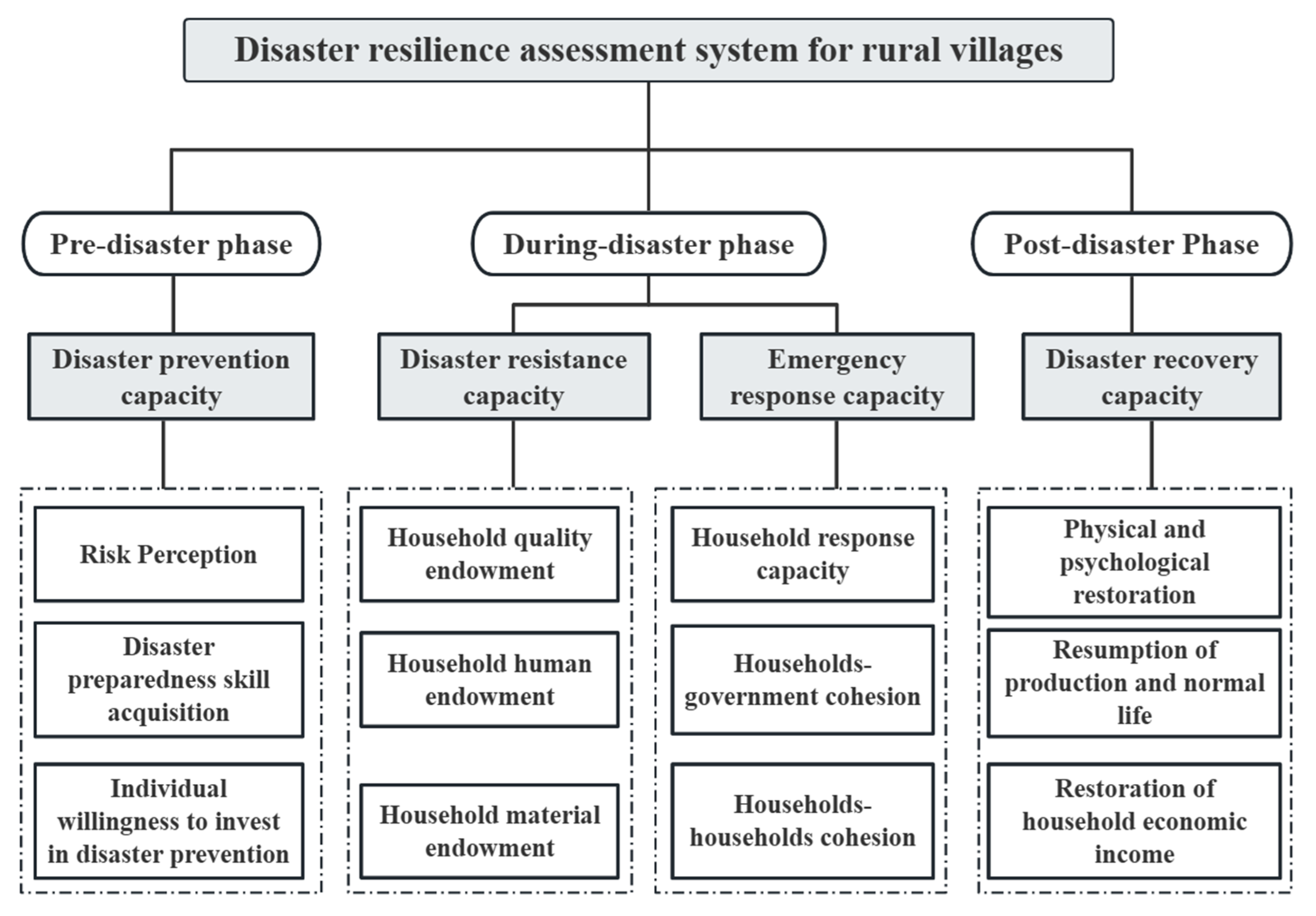

2.1. Assessment Framework for Village Disaster Resilience

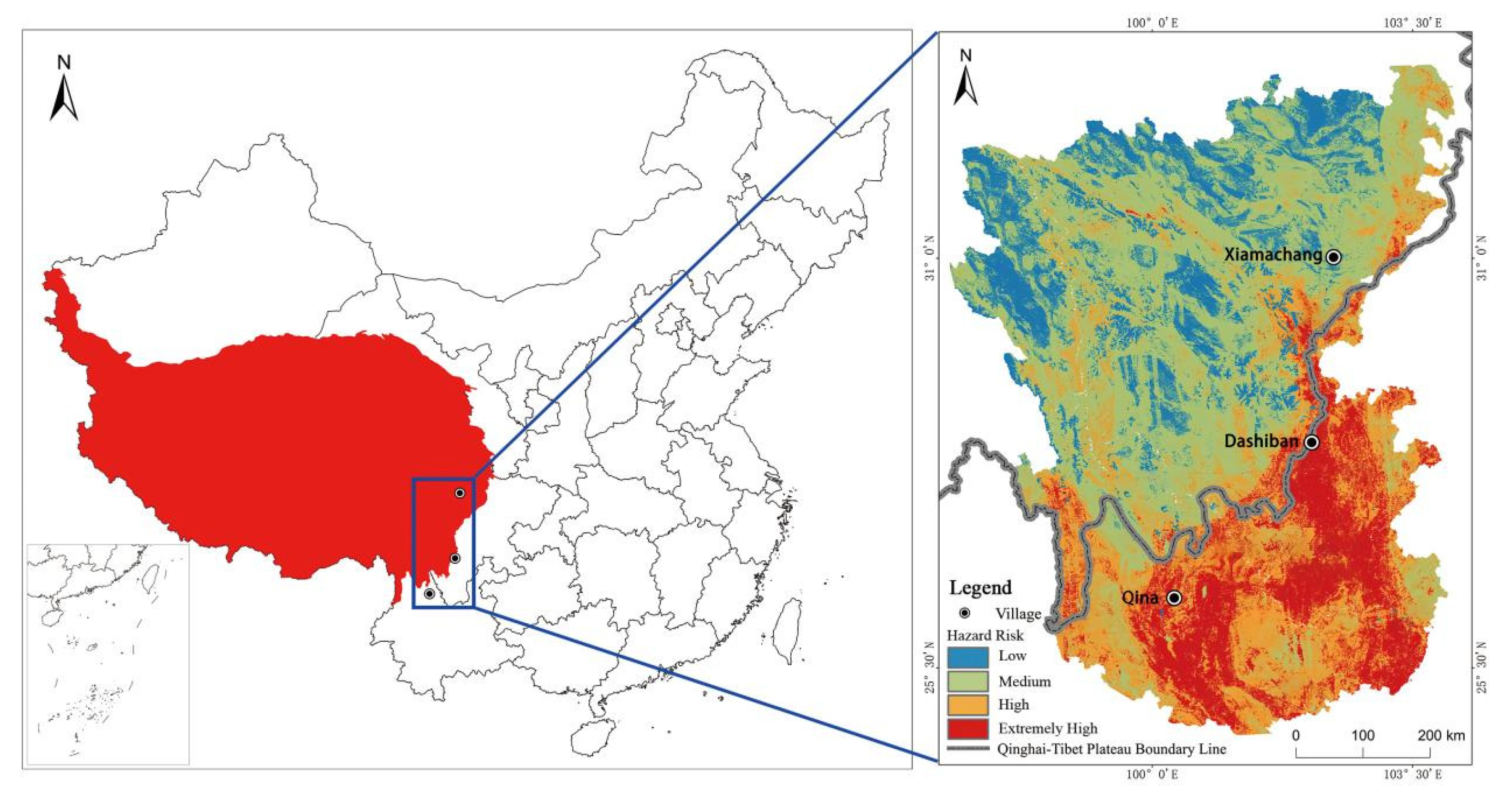

2.2. Case Study: Hengduan Mountains Region, China

2.3. Data Sources and Processing

2.3.1. Data Sources

2.3.2. Data Processing

- (1)

- The first step is to process the questionnaire survey data using the range standardization method to eliminate the differences caused by the attributes and dimensions of each indicator.

- (2)

- Step 2: Construct the initial indicator matrix based on the number of questionnaires and indicators. Let there be m first-level indicators, each with n second-level indicators, resulting in the initial evaluation indicator matrix:

- (3)

- Step 3: Calculate the proportion of all indicators. The formula for calculating the proportion of the value of the i-th first-level indicator under the j-th indicator is as follows:

- (4)

- Step 4: Calculate the entropy values for all indicator data. The formula for computing the entropy value of the j-th indicator is as follows:

- (5)

- Step 5: Calculate the differentiation coefficients for all indicator data. The formula for calculating the differentiation coefficient of evaluation indicator j is as follows:

- (6)

- Step 6: Calculate the weights of all indicator data. The formula for calculating the weight of evaluation index j is as follows:

2.4. Development of a Disaster Resilience Evaluation Index System for Villages

2.5. Village Disaster Resilience Assessment Model

3. Results

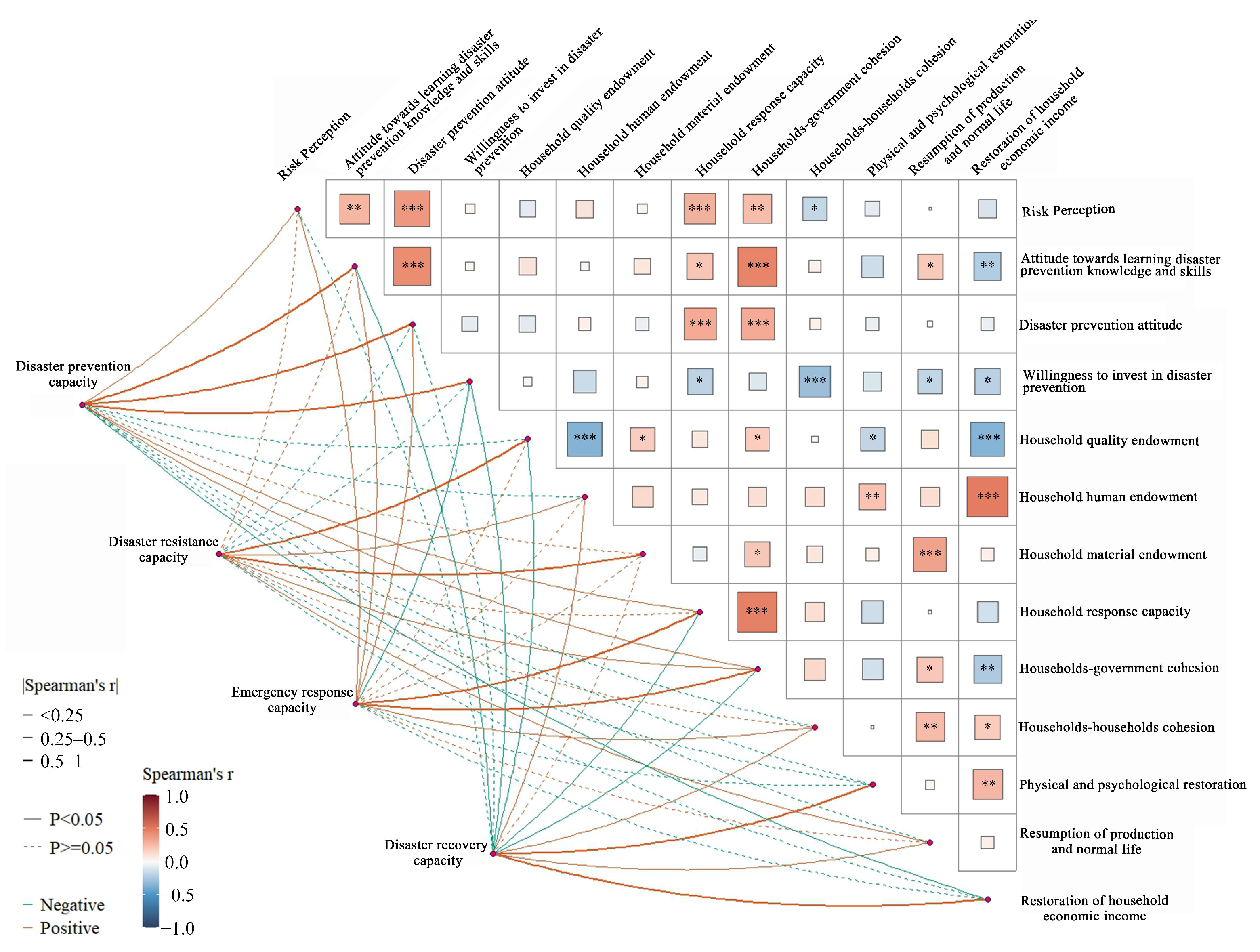

3.1. The Dominant Factors Influencing the Disaster Resilience of Villages

3.2. The Interaction Mechanisms Among Dimensions of Rural Disaster Resilience

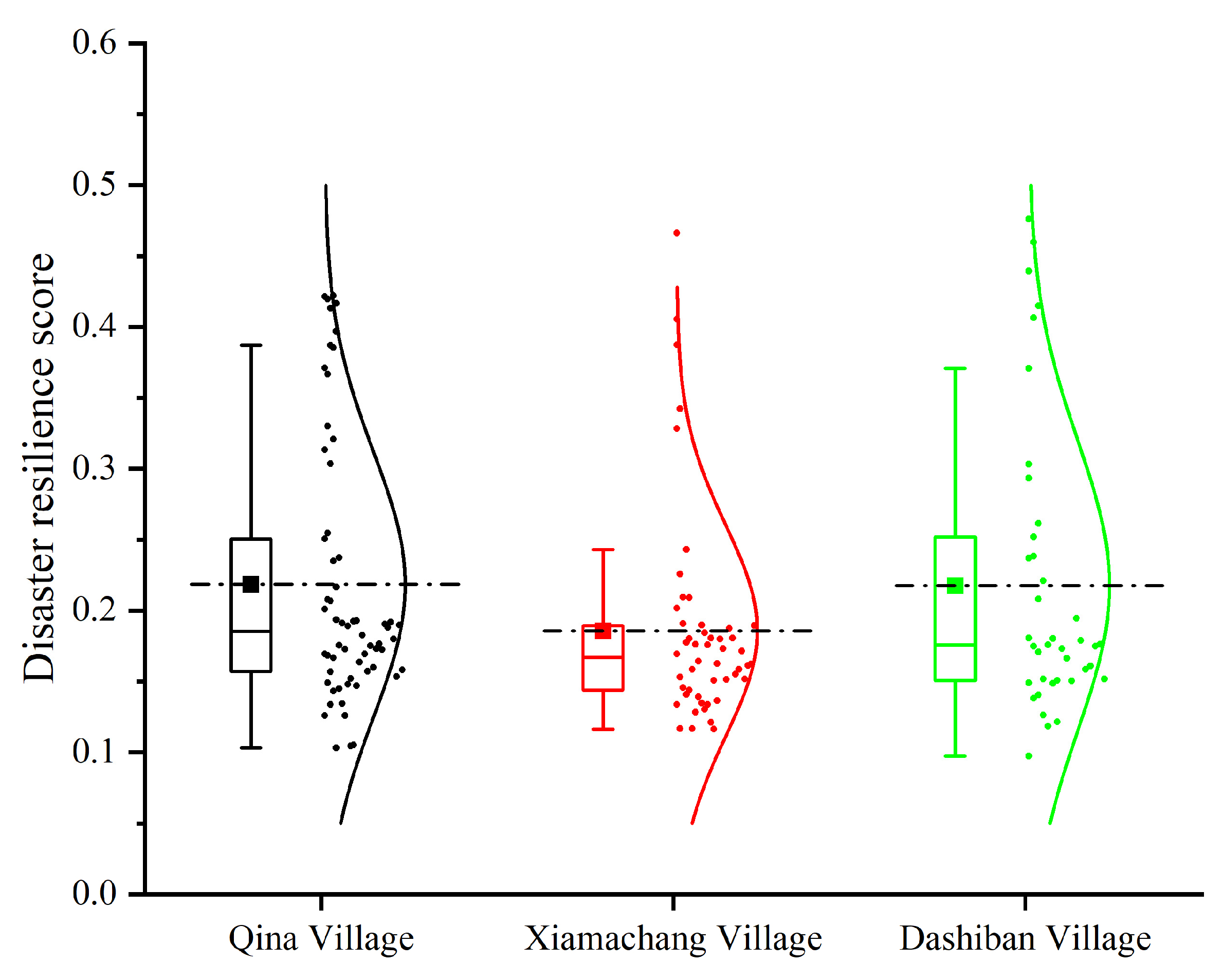

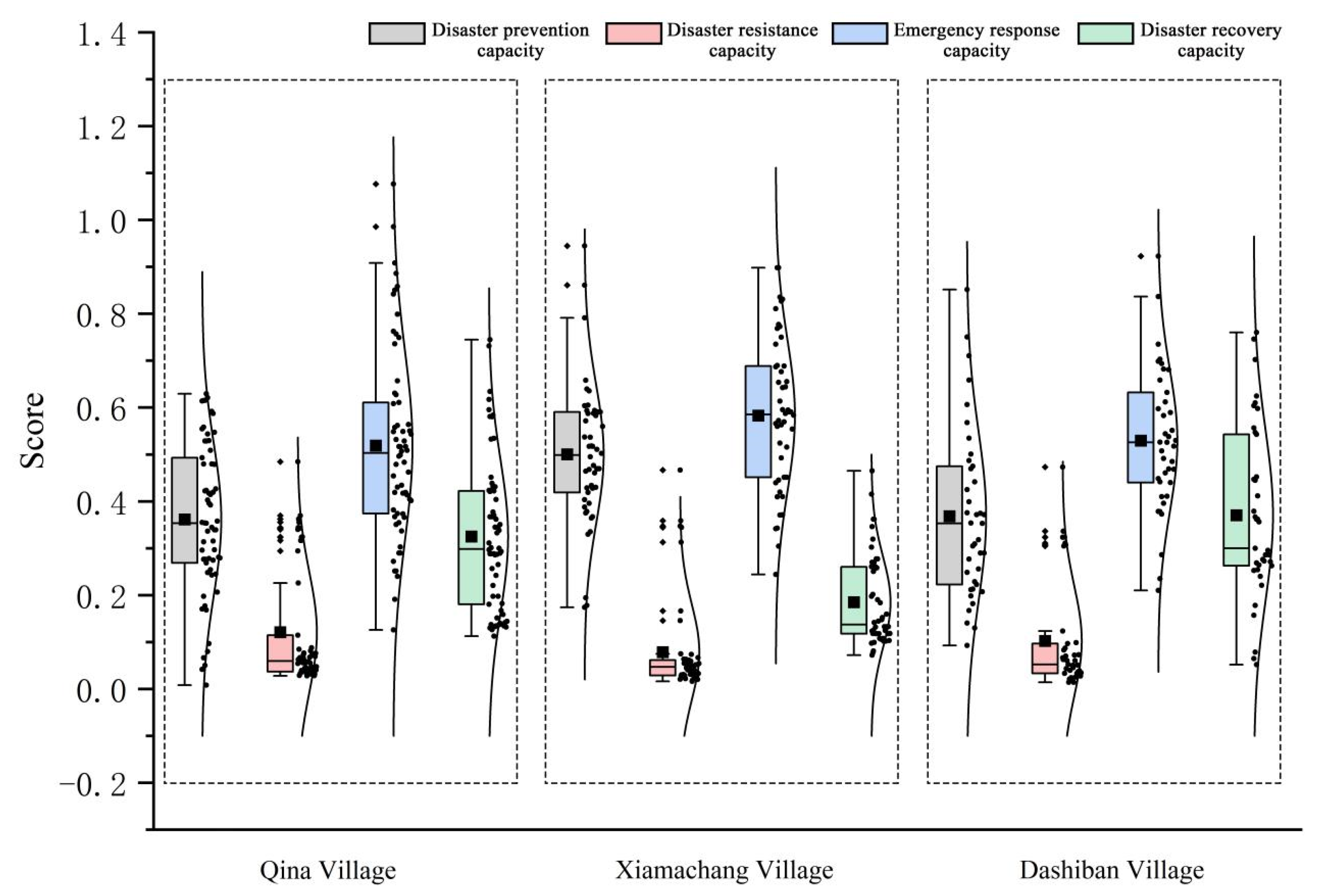

3.3. Analysis of Disaster Resilience Measurement Results in Typical Villages

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Factors Influencing Disaster Resilience in Mountainous Villages

4.2. Analysis of Differences in Disaster Resilience Among Typical Villages

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cui, P. Progress and prospects in research on mountain hazards in China. Prog. Geogr. 2014, 33, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Nan, X.; Shi, Z.Q.; Zhang, J.F.; Liu, B.T. Territory space characteristics and regional development of mountain region in China. Chin. J. Nat. 2018, 40, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Shao, Y.W. Resilient Cities: A New Shift to Urban Crisis Management. Urban Plan. Int. 2015, 30, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, X.L.; Zhang, X.H.; Zhang, J.F. Theme vein and frontier trend of research on disaster resilience at home and abroad. J. Nat. Disasters 2023, 32, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.J.; Qiao, G.M.; Pan, Z.Y.; Qian, Y. Study on the Spatio-Temporal Characteristics and Response Configuration Paths of Disaster Resilience in Coastal Zone Cities. J. Catastrophology 2025. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/61.1097.P.20251010.1434.002 (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Ren, J.; Wang, Z.H.; Wang, S.Y. Research on the assessment of urban safety resilience in the Yellow River Basin based on typical flood disaster chains. J. Saf. Environ. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.S.; Guo, B.Y.; Li, M.; Yao, Y.; Ghimire, S.K.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, C.; Wei, L.; Jiang, Y.; Li, X. Disparate perceived resilience of rural households at different altitude belts: An empirical study from the Wenchuan earthquake-stricken area, China. J. Mt. Sci. 2025, 22, 1151–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruslanjari, D.; Putri, R.A.P.; Puspitasari, D.; Djatmiko, R.H.; Tanaka, R.; Hasan, H.A.; Nabil, T.; Fajarian, N.A. From vulnerability to resilience: Examining the Sister Village program’s approach to volcanic disaster risk reduction using the DROP model. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2025, 26, 100439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhai, G.F. China’s urban disaster resilience evaluation and promotion. Planners 2017, 33, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, H.W.; Shi, M.J.; Cao, Q.; Ning, Z. Spatial distribution characteristics and disaster resilience assessment of traditional villages in earthquake-prone areas. J. Nat. Disasters 2024, 33, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, E.; Anderson, B.A.; Skerratt, S.; Farrington, J. A review of the rural-digital policy agenda from a community resilience perspective. J. Rural. Stud. 2017, 54, 372–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.T.; Lu, J.L. Two Models for Revitalizing Village: Enlightenments Under Resilient Perspective. Urban Plan. Int. 2017, 32, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, X.; Tao, W.; Liu, W.B. Literature review on the research progress of rural resilience. Hum. Geogr. 2023, 38, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.H.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, F.G.; Chen, Q.; Ma, W.D.; Zhou, Y.T. Research evolution and multi-dimensional prospect of disaster resilience. J. Catastrophology 2024, 39, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, G.F. Disaster Prevention, Mitigation, and Relief, and Resilient City Planning and Construction in China. Beijing Plan. Rev. 2018, 2, 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Drabek, T. Human System Responses to Disaster an Inventory of Sociological Findings; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1986; 479p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR). Hyogo Framework for Action 2005–2015: Building the Resilience of Nations and Communities to Disasters; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- The United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR). Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Drolet, J.; Dominelli, L.; Alston, M.; Ersing, R.; Mathbor, G.; Wu, H. Women rebuilding lives post-disaster: Innovative community practices for building resilience and promoting sustainable development. Gend. Dev. 2015, 23, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phibbs, S.; Kenney, C.; Severinsen, C.; Mitchell, J.; Hughes, R. Synergising public health concepts with the Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction: A conceptual glossary. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.B. Rural settlements research from the perspective of resilience theory. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 40, 556–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.Y.; G, C.L. Research on the Indicator System of Resilient Cities in China, Singapore Management and Sports Science Institute, Singapore. In Proceedings of the 2014 2nd International Conference on Social Sciences Research(SSR 2014 V6), Hong Kong, China, 10 December 2014; Singapore Management and Sports Science Institute: Singapore; Intelligent Information Technology Application Society: Zhuhai, China, 2014; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Z.X.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, W.H.; Song, C. Spatial pattern and attribution analysis of the regions with frequent geological disasters in the Tibetan Plateau and Hengduan Mountains. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2022, 77, 1211–1224. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.F.; Zhang, C.D.; Zhang, G.T. The development characteristics and formation modes of rainstorm-triggered flash flood disasters in the Hengduan Mountains. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2024, 79, 600–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.C.; Li, X.Z.; Hu, K.H.; Nie, Y.; Bian, J. A dynamic risk assessment for mountain hazards in the Hengduan mountain region, China. Mt. Res. 2020, 38, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.L. Coupling relationship and spatiotemporal characteristics of labor force flow and farmland transfer based on entropy method. J. Arid. Land Resour. Environ. 2020, 34, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.Y.; Su, G.W.; Wu, Q.; Qi, W.; Zhang, W. Features of awareness and response of rural households to earthquake disasters and their differences between inter-household: A case study of disaster area of Ms6.4 Ning’er, Yunnan, earthquake in 2007. J. Nat. Disasters 2012, 21, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, K.; Han, Z.Q.; Wang, D.M. Resilience of an Earthquake-Stricken Rural Community in Southwest China: Correlation with Disaster Risk Reduction Efforts. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, T.; Han, Z.Q.; Guo, C.L.; Lau, J.; Yu, J.; Su, G. Disaster preparedness, perceived community resilience, and place of rural villages in northwest China. Nat. Hazards 2021, 108, 907–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, L.; Barnes, G.D. Understanding household connectivity and resilience in marginal rural communities through social network analysis in the village of Habu, Botswana. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristow, G.; Healy, A. Handbook on Regional Economic Resilience; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Crookston, B.; Gray, B.; Gash, M.; Aleotti, V.; Payne, H.E.; Galbraith, N. How Do You Know ‘Resilience’ When You See It? Characteristics of Self-perceived Household Resilience among Rural Households in Burkina Faso. J. Int. Dev. 2018, 30, 917–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soetanto, R.; Mullins, A.; Achour, N. The perceptions of social responsibility for community resilience to flooding: The impact of past experience, age, gender and ethnicity. Nat. Hazards 2017, 86, 1105–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegney, D.; Ross, H.; Baker, P.; Rogers-Clark, C.; King, C.; Buikstra, E.; Watson-Luke, A.; McLachlan, K.; Stallard, L. Building Resilience in Rural Communities: Toolkit; The University of Queensland: St Lucia, QLD, Australia; University of Southern Queensland: Toowoomba, QLD, Australia, 2008; pp. 10–52. [Google Scholar]

- Rockenbauch, T.; Sakdapolrak, P. Social networks and the resilience of rural communities in the Global South: A critical review and conceptual reflections. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanazaki, N.; Berkes, F.; Seixas, C.S.; Peroni, N. Livelihood diversity, food security and resilience among the Caiçara of coastal Brazil. Hum. Ecol. 2013, 41, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, S.; Ishizaka, A.; Tasiou, M.; Torrisi, G. On the Methodological Framework of Composite Indices: A Review of the Issues of Weighting, Aggregation, and Robustness. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 141, 61–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.M.; Gerber, E.; Jung, S.; Agrawal, A. The role of human and social capital in earthquake recovery in Nepal. Nat. Sustain. 2022, 5, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.L.; Sim, T. Walsh Family Resilience Questionnaire Short Version (WFRQ-9): Development and Initial Validation for Disaster Scenarios. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2025, 19, e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaisie, E.; Han, S.S.; Kim, H.M. Complexity of resilience capacities: Household capitals and resilience outcomes on the disaster cycle in informal settlements. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 60, 102292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirmal, C.; Devraj, B. Building Community Resilience: A Study of Gorkha Reconstruction Initiatives. Molung Educ. Front. 2021, 11, 101–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.H.; Wang, S.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Du, G. The measurement of rural community resilience to natural disaster in China. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamjiry, Z.A.; Gifford, R. Earthquake Threat! Understanding the Intention to Prepare for the Big One. Risk Anal. 2022, 42, 487–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.L.; Sim, T.; Su, G.W. Individual Disaster Preparedness in Drought-and-Flood-Prone Villages in Northwest China: Impact of Place, Out-Migration and Community. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surjono, S.; Turniningtyas, A.R.; Adipandang, Y. Risk and Response to Disaster Assessment of Urban Village in The Framework of Sustainable Development. Evergreen 2024, 11, 1157–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.Y.; Su, G.W.; Li, Y.K.; Ma, Y. Livelihood Strategies of Rural Households in Ning’er Earthquake-Stricken Areas, Yunnan Province, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Male (n) | Female (n) | Mean Age (Years) | Mean Annual Household Income (CNY) | Percentage of the Population with a High-School Education or Higher (%) | Percentage of Persons with Disabilities (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xiamachang Village | 21 | 29 | 55 | 35,476 | 24 | 4.00 |

| Dashiban Village | 20 | 19 | 45 | 103,192 | 38 | 2.56 |

| Qina Village | 28 | 33 | 40 | 87,046 | 72 | 8.06 |

| Dimension | Weight Coefficient | Indicator | Weight Coefficient | Measurement Indicators and Directionality | Weight Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disaster prevention capacity | 0.12 | Risk perception [27] | 0.16 | Disaster preparedness knowledge (+) | 0.44 |

| Knowledge of disaster types (+) | 0.56 | ||||

| Attitude towards learning disaster prevention knowledge and skills | 0.16 | Attitudes toward learning about disaster risk reduction (+) | 0.73 | ||

| Attitudes toward learning disaster risk reduction skills (+) | 0.27 | ||||

| Disaster prevention attitude [28] | 0.34 | Attitudes toward coping with hazard-prone sites (+) | 0.23 | ||

| Attitudes toward disaster information (+) | 0.04 | ||||

| Coping attitudes toward disaster-preparedness cards (+) | 0.73 | ||||

| Willingness to invest in disaster prevention [29] | 0.34 | Willingness to pay for emergency relief supplies (+) | 1.00 | ||

| Disaster resistance capacity | 0.61 | Household quality endowment [30] | 0.12 | Age: proportion of vulnerable age groups (children < 14 yr; older adults ≥ 65 yr) (-) | 0.80 |

| proportion of females (-) | 0.09 | ||||

| Educational attainment (+) | 0.11 | ||||

| Household human endowment [31] | 0.71 | Proportion of persons with disabilities in household (−) | 0.60 | ||

| Labor force proportion in household(percentage of household members aged 16–59 who are economically active) (+) | 0.01 | ||||

| Proportion of village committee members in household (+) | 0.39 | ||||

| Household material endowment [32] | 0.17 | Household per capita annual income (+) | 0.19 | ||

| Proportion of wage and salaried income (+) | 0.09 | ||||

| Proportion of government transfer income (+) | 0.72 | ||||

| Emergency response capacity | 0.07 | Household response capacity [33] | 0.57 | Familiarity level with emergency evacuation routes (+) | 0.13 |

| Familiarity level with early warning signals (+) | 0.11 | ||||

| Disaster response operational experience (+) | 0.42 | ||||

| Self-preparedness level of emergency supplies (+) | 0.34 | ||||

| Households-government cohesion [34] | 0.32 | Perception of collaborative constraints (+) | 0.09 | ||

| Sense of community belonging (+) | 0.05 | ||||

| Government communication accessibility level (+) | 0.15 | ||||

| Government communication frequency level (+) | 0.41 | ||||

| Effectiveness level of collaborative assistance (+) | 0.08 | ||||

| Public knowledge level of government disaster management operations (+) | 0.12 | ||||

| Perception of equity (+) | 0.04 | ||||

| Perception of collaborative tolerance (+) | 0.04 | ||||

| Public understanding level of government risk preparedness measures (+) | 0.02 | ||||

| Households-households cohesion [35] | 0.11 | Number of mutual assistance neighbors (+) | 0.82 | ||

| Neighborly relations (+) | 0.18 | ||||

| Disaster recovery capacity | 0.20 | Physical and psychological restoration | 0.34 | Psychological recovery (+) | 0.88 |

| Physical recovery (+) | 0.12 | ||||

| Resumption of production and normal life | 0.14 | Number of insurance policies (+) | 0.79 | ||

| Number of close relatives and friends (+) | 0.21 | ||||

| Restoration of household economic income [36] | 0.52 | Percentage of employed household members (+) | 0.07 | ||

| Diversity of income sources (+) | 0.93 |

| Disaster Prevention Capacity | Disaster Resistance Capacity | Emergency Response Capacity | Disaster Recovery Capacity | Household Disaster Resilience | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qina Village | 0.043 | 0.074 | 0.036 | 0.065 | 0.218 |

| Xiamachang Village | 0.060 | 0.048 | 0.041 | 0.037 | 0.186 |

| Dashiban Village | 0.044 | 0.062 | 0.037 | 0.074 | 0.217 |

| Mean Value | 0.049 | 0.061 | 0.038 | 0.059 | 0.207 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, F.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, L.; Liu, F.; Ma, W.; Li, H.; Chen, Q.; Liu, Y. Evaluation of Disaster Resilience and Optimization Strategies for Villages in the Hengduan Mountains Region, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10176. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210176

Zhao F, Zhou Q, Liu L, Liu F, Ma W, Li H, Chen Q, Liu Y. Evaluation of Disaster Resilience and Optimization Strategies for Villages in the Hengduan Mountains Region, China. Sustainability. 2025; 17(22):10176. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210176

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Fuchang, Qiang Zhou, Lianyou Liu, Fenggui Liu, Weidong Ma, Hanmei Li, Qiong Chen, and Yuling Liu. 2025. "Evaluation of Disaster Resilience and Optimization Strategies for Villages in the Hengduan Mountains Region, China" Sustainability 17, no. 22: 10176. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210176

APA StyleZhao, F., Zhou, Q., Liu, L., Liu, F., Ma, W., Li, H., Chen, Q., & Liu, Y. (2025). Evaluation of Disaster Resilience and Optimization Strategies for Villages in the Hengduan Mountains Region, China. Sustainability, 17(22), 10176. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172210176