Abstract

This research examines the pursuit of behavioral change for climate-resilient tourism along the Catalan coast by engaging territorial stakeholders in a co-creation process. This study is guided by the following research question: how can the co-creation of integrated climate services, water and energy management, and beach-dune conservation foster behavioral change among stakeholders towards climate-resilient tourism along the Catalan coast? Focusing on two destinations in Catalonia (Costa Daurada and Terres de l’Ebre), it examines three interconnected dimensions of tourism activity: (1) weather, climate, and climate change; (2) energy and water; and (3) beach-dune systems. Through our analysis, we pursue three secondary objectives: (1) to assess the influence of meteo-climatic conditions on tourist activity, (2) to identify necessary adaptation measures related to water and energy management, and (3) to explore how historical photographs can shape stakeholders’ perceptions regarding the relevance and conservation of the beach-dune system. By bringing together expertise in climate services, resource management, and ecosystem conservation, this study explores how collaborative engagement with public and private stakeholders can foster adaptive strategies that enhance the sustainability and resilience of coastal tourism. The findings directly respond to the research question by showing that co-creation processes integrating climate, resource, and ecosystem management can effectively foster behavioral change among stakeholders. Specifically, the main results highlight (1) a clear relationship between meteo-climatic conditions and tourism activities, underscoring the importance of climate awareness; (2) stakeholder recognition of practical adaptation measures focused on water and energy management to increase sector resilience; and (3) the use of the historical photographs as an effective tool to enhance participants’ understanding of beach-dune systems, improving their knowledge of these ecosystems’ dynamics, formation, and evolution.

Keywords:

co-creation; stakeholders; climate change; adaptation; tourism; energy; water; beach management 1. Introduction

While many studies have explored sustainability initiatives in tourism, few have examined how the integrated management of climate services, water, energy, and beach-dune systems can drive behavioral changes among diverse stakeholders. Current research often overlooks the factors influencing stakeholders’ willingness to engage in sustainable practices and how these factors interact within the context of integrated environmental management. Furthermore, there is a limited exploration of how co-creation processes, where stakeholders collaborate in designing sustainable strategies, can foster a shift in behavior that supports long-term sustainability in coastal tourism.

This paper addresses this gap by examining stakeholder perceptions on the potential for co-creating pathways to sustainable tourism through the integrated management of climate services, water, energy, and beach-dune systems. Given the increasing sustainability challenges facing the tourism sector along the Catalan coast, it is essential to evaluate stakeholders’ perceptions regarding climate-resilient tourism to promote behavioral change within industry.

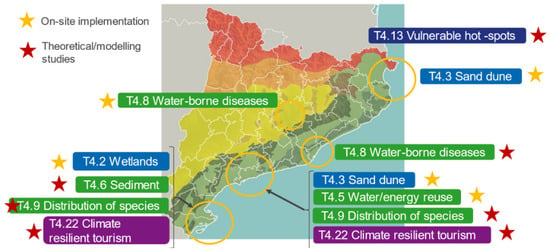

This paper’s primary objective within this framework is to pursue behavioral change for climate-resilient tourism along the Catalan coast, specifically in the Costa Daurada and Terres de l’Ebre destinations, by engaging territorial stakeholders in a co-creation process. The present research’s demo site is established within the Catalan Coast demo site of the IMPETUS project (https://climate-impetus.eu/, accessed on 17 September 2025), where various climate change adaptation solutions are developed. This paper’s case study focuses on climate-resilient tourism (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Activity’s location in the IMPETUS project.

With our analysis, we achieve three secondary objectives: (1) to understand how meteo-climate conditions influence tourist activity, (2) to describe what mitigation and adaptation measures have to be implemented regarding water and energy management, and (3) to explore how the use of historical photographs can modify stakeholders’ perception of the relevance and conservation of the beach-dune system. In this regard, we aim to make a modest contribution to implementing adaptation measures in the tourism sector, in accordance with the Catalan Climate Change Adaptation Strategy (ESCACC30). The study also aligns with the EU’s 2050 climate goals, translating commitments into actionable steps for community and planetary protection. This research also aligns with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Climate Action (13), Responsible Consumption and Production (12), Clean Water and Sanitation (6), Affordable and Clean Energy (7), and Life on Land (15) by promoting climate resilience, sustainable resource management, and the integration of renewable energy solutions in tourism and territorial planning.

Building on these objectives, this study is guided by the following research question: How can the co-creation of integrated climate services, water and energy management, and beach-dune conservation foster behavioral change among stakeholders towards climate-resilient tourism along the Catalan coast? To operationalize this, we further address three sub-questions: (1) How do meteo-climatic conditions influence tourist activities and perceptions of climate risks? (2) What mitigation and adaptation strategies related to water and energy management do stakeholders consider most relevant? (3) How does the use of historical photographs affect stakeholders’ understanding of the relevance of beach-dune systems and their willingness to support conservation efforts?

However, despite the clear need for such practices, a significant gap remains in understanding how to effectively promote and sustain behavioral change in coastal tourist destinations. Within this context, in the next section, the literature review supports this gap by highlighting the challenges and complexities involved in fostering sustainable behaviour among tourists and stakeholders.

2. Literature Review

This literature review explores key topics at the intersection of climate change and tourism. It examines climates, tourism, and sustainability; climate assessments for tourist activities; the impacts of climate change on tourism; and the need for effective adaptation strategies. Additionally, it addresses the challenges of maladaptation, the role of water and energy management in tourism, and the vulnerability of beach-dune systems. These themes underscore the complex relationship between climate change and tourism, emphasizing the need for integrated and sustainable approaches to ensure resilience in tourist destinations.

2.1. Climate, Tourism, and Sustainability: A General Overview

Nowadays, the impact of climate on human activities is noticeable; even without considering fatalistic thoughts, it is evident that human beings adjust their activities in response to the climate and environment [1]. Tourism is a widely recognized climate-sensitive sector that involves diverse global leisure activities, such as sun, sea, and sand (3S), cultural experiences, cycling, golf, skiing, hiking, and sailing. Climate variability and change influence source markets and tourist behaviors (including travel motivations and destination choices), tourism operators (such as accommodations, infrastructure design, and transport), and the destinations themselves [2].

In this context, the climate is one of the factors that influence travel planning. The concept of climate influences travel plans made months in advance. Climatology contributes to destination choice, travel timing, activity planning, and insurance needs. Weather forecasts influence short-planned travel and are taken into consideration when selecting last-minute holidays. Once tourists are on the trip, the weather strongly impacts their activity selection and behavior at the destination. Weather will also indicate when trip activities require specific actions, such as using, avoiding, changing, adapting, or accepting alternate options. Weather also influences spending behavior and trip satisfaction [3]. Additionally, some research [4] noted, climate can serve as an essential resource or a necessary complement to tourist activity. At some destinations, in addition to geographical location, topography, landscape, flora, and fauna, weather and climate also constitute the natural resource base for recreation and tourism [5]. Climate services play a crucial role in tourism by transforming climate data into actionable information, enabling informed decision-making for climate-smart strategies that enhance resilience, sustainability, and visitor experience [6,7].

Coastal tourism is a significant economic driver globally. However, it is also highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change [8], such as rising sea levels [9,10], extreme weather events [11,12], and ecosystem degradation [13].

As the tourism sector increasingly acknowledges its contribution to climate change [14], it also plays a critical role in addressing climate challenges through mitigation and adaptation strategies [9,15,16]. These strategies help the sector reduce its environmental impact and adapt to the evolving threats posed by climate change [9]. There is a growing recognition of the need for behavioral change among tourists and local communities [17,18,19,20]. Sustainable practices [21,22]—such as responsible waste management [23,24], water conservation [25,26], eco-friendly transportation [27,28] and supporting environmentally conscious businesses [29,30]—are essential for reducing the sector’s carbon footprint and preserving fragile coastal ecosystems [31]. However, despite the clear need for such practices, a significant gap remains in understanding how to promote and sustain behavioral change in coastal tourist destinations effectively.

2.2. Climate Assessment for Tourist Activities

From a climatological research perspective, climate assessment for tourism has been traditionally studied through the Tourism Climate Index (TCI) [32]. Different studies have applied this index to assess the tourist climate potential; for instance, some research [33] utilized it in the Canary Islands. Other research [34] applied the TCI to assess the climatic suitability of Afriski Mountain Resort for outdoor tourism. They quantified the climatic sustainability tourism in Namibia by also using the TCI [34]. Fang et al. [35] followed a similar approach for China. Scott et al. [36] evaluated the distribution of climatic resources for tourism in North America by utilizing the TCI.

Even so, new research has explored the design of indicators to assess climate suitability for various activities and the assessment of tourist climate suitability through comparisons of different indices. A study [37] compared the Holiday Climate Index (HCI) with the Tourism Climate Index (TCI) in Europe. Similar studies [38] compared the Holiday Climate Index (HCI: Beach) and the Tourism Climate Index (TCI) to explain Canadian tourism arrivals to the Caribbean. Other examples include the work of [39] compare the holiday climate index (HCI) and the tourism climate index (TCI) in desert regions and the Markazi coast of Iran. Moreover, a comparison between TCI and HCI in major European destinations was conducted in previous research [40] compared TCI and HCI in major European destinations. Another example of computing the TCI for a tourist destination can be found in the research, in that case, they [41], which investigated not only the changes in five climatic variables over 21 years in Narok, Kenya, by using the TCI but also determined trends in changes in the climatic variables and TCI over the study period, linear regression models were fitted to the data and the significance of the ensuing slopes computed. Based on the study’s results, it is recommended that the country take deliberate action to mitigate the adverse effects of climate change through targeted approaches, such as accelerated reforestation, sustainable land-use practices, and conservation.

New indices to assess climate suitability were also designed. For example, a Coastal Tourism Climate Index (CTCI) was developed to evaluate the suitability of the tourism climate in Chinese coastal cities, focusing on pollution [42]. Others [43] (2008) developed a second-generation climate index for tourism (CIT). Similar research [44] evaluated human thermal comfort using the Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI). Others [44] analyzed present and future climate potential for outdoor tourism activities in Spain. For sea-based tourism were [45] (2022) developed indices to evaluate the climatic suitability of seawater activities, including surfing, windsurfing, and paddleboarding. With a similar perspective, were [46] identified opportunities for wind sport tourism destinations by considering the number of days that contained at least two consecutive hours with an average wind speed above a certain threshold (3.6 m/s, 7.7 m/s, and 10 m/s).

2.3. Climate Change Impacts and Tourism

Research not only examines climate suitability based on historical data but also explores its future implications. For example, we found the study [47] that applies the HCI in the Near-Future Climate using an ensemble model in the context of RCP45 and RCP85. Similarly, other research [48] (2023) analyzed urban climate comfort in the Peninsula and Balearic Islands during summer using the HCI model, focusing on mid-century (2041–2060) and late-century (2081–2100) scenarios under RCP 4.5 and 8.5. Results show significant increases in comfort in northern and northwestern Spain. At the same time, southern regions such as Extremadura, Murcia, Andalusia, and the Balearic Islands are experiencing a decline, leading to shifts in tourism patterns. Despite room for improvement, the HCI Urban Index is valuable for urban planning and decision-making in the evolving tourism context. Other studies, [49], have examined the implications of climate change for tourism and outdoor recreation based on projected changes to Indiana’s climate. They found that the direct impacts of climate change on Indiana include increases in hot and extremely hot days each summer, fewer mild days, increased rainfall, and reduced snowfall. Each direct impact will affect tourism and recreation. Moreover, they stated that various expected indirect consequences could arise, including alterations in health concerns related to climate change, the emergence of new infrastructure requirements, modifications to forests and alternative leisure spaces, and shifts in consumer perspectives on travel and recreational activities. While they can predict the direct consequences, it becomes more challenging to anticipate the indirect effects on the intricate tourism system. Therefore, the tourism and recreation industry must cultivate resilience to adapt to forthcoming changes effectively.

As seen above, some studies focus directly on the impacts of climate change on tourism. Other studies [50] highlighted the primary impacts of climate change on surf tourism. Surfing has gained significant global cultural, social, and economic importance; however, its future is at risk because of climate change. This paper reviews the physical processes that influence surf locations —wave generation, breaking, and coastal dynamics —and examines how these processes can be affected by climate change. The authors propose a framework for categorizing these impacts based on their direct or indirect nature and magnitude, highlighting that some threats, such as rising sea levels, may emerge gradually. In contrast, others, such as coastal armouring, pose immediate dangers. The framework emphasizes the importance of local knowledge in assessing surf break vulnerability to climate change. It introduces SurfCAT to help resource managers and stakeholders protect waves amid climate change.

Similar research [51] investigated the impact of climate change patterns on tourism activities in Uganda. The study’s correlation analysis revealed a consistent, significant positive relationship between climate change indicators—such as droughts, floods, and landslides—and various aspects of tourism, including food supply, travel services, and accommodation. Moreover, regression analyses revealed that climate variability factors—specifically droughts, floods, and landslides—were more effective predictors of changes in tourism activity. Among these factors, flooding emerged as the most influential predictor, followed by landslides and droughts, which collectively explain variations in tourism activity.

In summary, these studies underscore the complex and multifaceted impacts of climate change on tourism, highlighting both direct and indirect effects across various regions and activities. While some research focuses on assessing future climate suitability, others emphasize the sector’s vulnerabilities and the need for adaptation strategies. This growing body of literature underscores the need for tourism stakeholders to incorporate climate considerations into their planning and decision-making processes to ensure long-term sustainability and resilience.

2.4. Climate Change Adaptation and Maladaptation

Climate change is having a significant impact on the global tourism industry. However, this sector is considered less prepared compared to others in addressing the challenges and opportunities posed by climate change. Efforts are underway to enhance the industry’s understanding of climate change and its impact on tourism, aiming to educate businesses, communities, and governments about the issues and potential solutions [52].

On the one hand, the tourism industry may be one of the greatest economic victims of climate change. However, on the other hand, the broader tourism sector is also a significant contributor to greenhouse gas emissions [53,54,55]. Adaptation refers to adjusting to the impacts of climate change to minimize damage and identify new opportunities. At the same time, mitigation involves interventions aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions and addressing the root causes of climate change. The dilemma arises when considering which approach to prioritize given the world’s limited resources: whether to focus on adapting defensively to the consequences or taking an offensive approach by mitigating the causes of climate change in the tourism sector [56]. Therefore, it is crucial to discuss the dual challenges of adaptation and mitigation in tourism science, not just as isolated responses but with a focus on transforming the tourism industry towards sustainable practices that promote responsible landscape management. This transition is crucial for enhancing the resilience of tourist regions and ensuring their long-term viability in the face of climate change [56].

Several studies focus on examining actions for climate change adaptation. For example, it was proposed India’s first coastal protection guidelines for climate-change adaptation [57]. The guidelines provide a comprehensive approach, considering various aspects such as engineering, economics, environment, and governance, to protect coastal residents in India from the impacts of climate change. The study presents 57 recommendations across nine categories, including administrative and best-practice measures for coastal protection. It also introduces a scientific tool, the Environmental Softness Ladder, to guide policy development and project implementation. The study involved numerous experts, agencies, and stakeholders, acknowledging the diverse dynamics along India’s coastline.

In the ski industry, resorts employ three key climate change adaptation strategies: artificial snow production, product diversification, and year-round operation. Understanding stakeholder perceptions towards these strategies is vital for successful adaptation. This study examines stakeholder opinions in Pamporovo, Bulgaria, involving tourists, local tourism representatives, and the local population. Surveys and interviews reveal that while local businesses favor artificial snow, tourists seek a unique atmosphere, diverse activities, and year-round operation. Residents support product diversification and year-round operations to create employment opportunities. Combining these strategies is crucial for sustainable adaptation and addressing various crises beyond climate change [58]. Other research indicates that climate change is causing glacier retreat in high-mountain environments, impacting glacier tourism sites. This article suggests three adaptation strategies: developing tourism, transforming last-chance tourism into “dark tourism,” and utilizing virtual reality to recreate disappearing glaciers. The cases of the Aletsch Glacier, the Mer de Glace, and the Mortaretsch Glacier are discussed as examples of these strategies [59].

The tourism industry is characterized by constant adaptation [60], which confronts both demographic and economic changes, as well as health crises such as COVID-19 [61], and climate crises. In response to the effects of climate change, tourist destinations are implementing adaptation strategies, which are approaches aimed at adjusting to the current or expected climate and its consequences to mitigate harmful effects and exploit beneficial ones [62]. Examples include the use of protective structures on coastlines [63,64,65], technical solutions like snow production in ski resorts [66], or the deployment of diversified tourism activities in mountainous regions [67].

However, not all adaptation strategies are successful; some can unintentionally increase the risk of adverse consequences, becoming examples of maladaptation [68]. Maladaptation refers to actions taken to reduce vulnerability to climate change that increase vulnerability in other systems, sectors, or social groups. Practical examples demonstrate the importance of understanding and avoiding maladaptation in climate change adaptation efforts [69]. In this context, the technical adaptation, such as snow production in ski resorts, can sometimes be linked to maladaptation. As an example, it was found that snowmaking is highly context-specific, varying across individual operators and regional markets, representing a continuum from successful adaptation to maladaptation [70].

Existing literature emphasize the need for developing context-specific guidelines to help funding bodies make informed decisions that support adaptation while better capturing the risks of maladaptation. These guidelines can also help practitioners design adaptation strategies that minimize the risk of maladaptation [71].

2.5. Water, Energy, and Beach-Dune Systems in Tourism: Balancing Resources and Resilience?

The tourism industry is highly vulnerable to the indirect impacts of climate change, including reduced water availability and quality, increased food and energy costs, rising sea levels, beach erosion, and more frequent wildfires [12,71,72]. Among these challenges, water and energy consumption in tourism are particularly significant. Tourist water use is a critical issue, as demand is expected to grow alongside the expansion of tourist accommodations and attractions such as spas, pools, and golf courses [73]. This increasing demand, combined with potential reductions in water availability due to climate change, poses a significant sustainability concern [72,74,75].

Coastal dune systems are dynamic environments formed just above the high-tide line, where sediment exchange between the beach and dunes occurs through wind and storm activity, functioning as a single, interconnected system [76]. These ecosystems are crucial for coastal protection and biodiversity, yet they are disappearing at an alarming rate. By the end of the 20th century, nearly 70% of dune habitats had been lost in Europe, with the situation being even more critical along the Catalan coast, where up to 90% of dune areas have suffered severe degradation [77]). This decline is strongly linked to coastal urbanization and beach tourism, which are primary drivers of dune landscape degradation.

In response to these challenges, related studies [78] propose a strategy to integrate tourism into efforts to mitigate coastal climate change. This approach advocates transforming coastal destinations into carbon sinks by restoring blue carbon ecosystems, such as marshes, mangroves, and seagrass meadows, through coordinated restoration projects. Tourism can play a pivotal role in supporting these initiatives by providing financial resources, maintaining a sustained presence, and adopting a business model that relies on healthy ecosystems. By leveraging tourism in this way, large-scale restoration efforts can become more feasible and impactful.

Furthermore, the landscape features of coastal areas significantly influence the resilience of tourism infrastructure and, consequently, the local economy. Climate change exacerbates the vulnerability of these areas to natural disasters, including tsunamis, storm surges, and erosion. The topography of coastal destinations, therefore, must be a key consideration in tourism planning to enhance resilience and minimize risks [79].

Given these interconnections, sustainable tourism development must address the challenges related to water and energy use, the degradation of beach-dune systems, and the broader impacts of climate change. Integrating adaptive management strategies that prioritize resource efficiency and ecosystem restoration will be essential for ensuring the long-term viability of coastal tourism.

3. Study Area and Methodology

3.1. Study Area

Spain is a top global tourist destination that has been significantly impacted by climate change. Its favorable year-round weather has enabled the development of various outdoor leisure activities beyond beach-based tourism, thereby reducing the high seasonality of tourism. While the climate is currently an asset, it may become a constraint for these activities in the future [80]. The Mediterranean region is one of the areas most affected by the impacts of climate change [81,82,83,84].

Admittedly, Spain will have to face the challenges imposed by climate change through mitigation and adaptation strategies at both local and regional scales for the tourism industry, which is the most important economic sector in terms of income revenues and employment. According to the UNWTO highlights [85], Spain became the world’s second-largest destination in 2017, with 81.8 million international tourist arrivals and $68 billion in tourist receipts. Moreover, it was the leading European country in terms of the number of overnight stays by foreign visitors. Climate change will likely degrade the present favorable conditions for outdoor tourist activities during the Mediterranean summer by 2050, while climatic conditions are expected to improve during spring and autumn [86,87,88]. Considering this framework, this study assesses environmental challenges at a regional level, with a primary focus on two prominent coastal destinations: Costa Daurada and Terres de l’Ebre, located in Catalonia, northeastern Spain, within the southeastern Mediterranean region. These areas serve as key demonstration sites due to their dynamic interaction between tourism, natural ecosystems, and climate-related pressures. This area stands out as a tourism hotspot where natural and societal factors intersect with economic activities, urbanization, agriculture, and critical infrastructure. The high concentration of these competing interests makes the region particularly susceptible to the impacts of climate change.

3.2. Approach to User Engagement

As mentioned in the introduction, climate plays a crucial role in shaping tourist and leisure activities [3], and tourism is highly dependent on the climatic conditions of a given destination. For this reason, previous investigations [89] examined the impact of two degrees of global warming on European summer tourism from a climate comfort perspective.

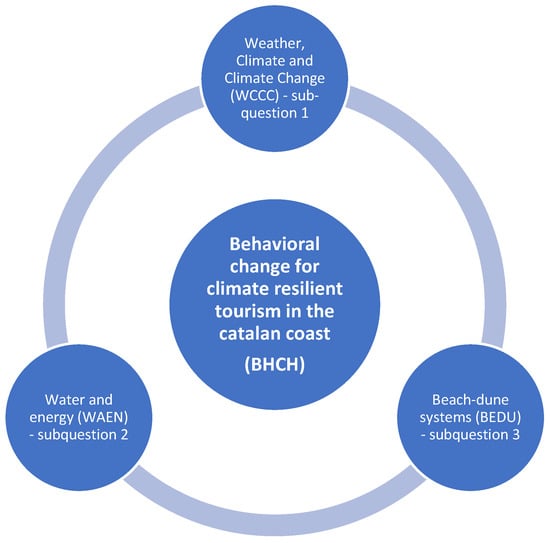

In this context, there is a need for behavioral change (BHCH, from here on) to promote climate-resilient tourism. This research presents a new and integrated approach to exploring stakeholders’ perceptions of how various environmental elements influence tourist activity. To achieve this purpose, we adopt the methodology for co-creating climate services across various European tourist destinations [90]. The new approach considers not only weather, climate, and climate change (WCCC, from now on) but also water and energy (WAEN) and beach-dune system (BEDU) stakeholders’ roundtables. This approach aims to integrate these three spheres of knowledge (linked to the three sub-research questions) to understand stakeholders’ perceptions of environmental challenges in their tourist destinations (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Join spheres to pursue behavioral change for climate resilient tourism on the Catalan coast.

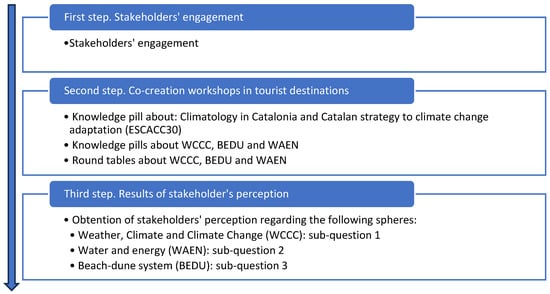

To gather stakeholders’ perceptions (Figure 3), we engaged with stakeholders in the first step. Then, two co-creation workshops were held in two different tourist destinations (second step), with the same structure applied to both. The workshop included a brief presentation from the Meteorological Service of Catalonia on the climatology of Catalonia. Then, the Catalan Office for Climate Change gave a speech on the Catalan strategy for climate change adaptation (https://canviclimatic.gencat.cat/ca/ambits/adaptacio/estrategia-catalana-dadaptacio-al-canvi-climatic-2021-2030/, accessed on 2 September 2025). Following this, brief knowledge sessions were held on WCCC, BEDU, and WAEN. After those presentations, co-creation roundtables were held in heterogeneous stakeholder groups.

Figure 3.

Procedure to gather stakeholders’ perceptions to pursue a behavioral change for climate resilient tourism.

The co-creation process involved public and private stakeholders from Costa Daurada and Terres de l’Ebre, who actively participated in the workshops. Each workshop had a roundtable for each knowledge sphere: WCCC, BEDU, WAEN. The present study focuses on presenting the results of stakeholders’ perceptions (step three).

3.3. Co-Creation Methodology for Understanding Stakeholders’ Perception

The study adopted the methodology developed by Font-Barnet et al. [90] to co-create climate services for tourism in European destinations. In this method, stakeholders were asked about tourist activities at their destination. After selecting the specific tourist activities, the technique of Font-Barnet et al. [90] was applied. Some adjustments to the co-creation method were made to align with the purpose of this research.

The methodology was adapted for the WCCC round tables (sub-question 1) to explore the relationships between tourism and climate in the Costa Daurada and the Terres de l’Ebre. Focus groups were designed to address the main coastal tourist activities in these areas. The methodology consists of three main steps. The first step is identifying the relationship between climate and tourist activities. This step aims to characterize tourist activities and gather qualitative information that complements quantitative data. Stakeholders are asked to discuss how extreme weather events (e.g., water scarcity, temperature rise, sea level rise) affect their activities and identify non-climatic factors influencing tourism, including reasons for booking cancellations. The second step focuses on analyzing the impact of meteorological and climatic conditions. It aims to assess how specific meteorological and climatic conditions benefit or harm various tourist activities. Stakeholders identify and rank the conditions that impact their activities, from most harmful to least beneficial. Finally, the third step aims to identify adaptation measures for climate variability and change, focusing on potential strategies to mitigate its effects. Stakeholders discuss adaptation strategies, considering the roles of different actors (e.g., local administration and private companies) in implementing these measures.

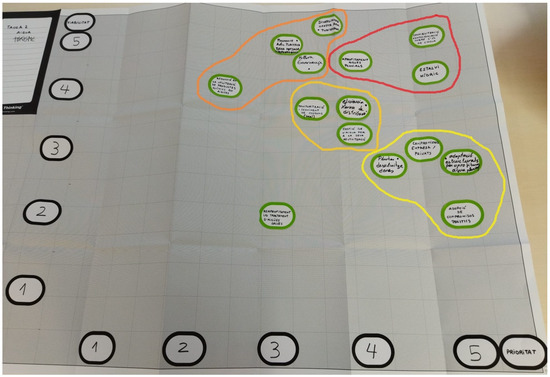

For the WAEN round tables (sub-question 2), an exhaustive list of stakeholders from both the public and private sectors linked to the tourism industry in Costa Daurada was compiled and contacted via email. In the initial communication, they were informed about the workshop’s structure and objectives. However, in many cases there was no response, and in others participation was impossible due to scheduling conflicts. Ultimately, nine people participated in the first workshop and ten people in the second workshop. Table 1 displays their distribution based on whether they belonged to the public or private area, the type of company they represented, their position within the organization, and gender. Even so, the representation of the stakeholder for each WAEN in the two held workshops is similar (regarding quantity and profile type) to previous research using similar methodology [90]. The participatory process was divided into two phases. In the first phase, each stakeholder was required to complete an individual questionnaire regarding their level of concern about the impact of various physical hazards on coastal tourism, primarily climatic and meteorological, and exacerbated by climate change. A five-point Likert-type scale ranged from 1 (not concerned) to 5 (very concerned). The second phase involved the workshop, adapting a methodology developed by Font-Barnet et al. [90]. First, the participants were asked to identify the potential impacts of climate change on tourism activities. Secondly, they had to propose mitigation and adaptation strategies for energy and water consumption. A five-point Likert-type scale ranged from 1 (low priority/feasibility) to 5 (high priority/feasibility). Contributions in this phase were recorded using mental maps and stickers (Figure 4).

Table 1.

Type and number of organizations by workshops.

Figure 4.

Mind map: Identification of adaptation and mitigation measures, showing their relationship to assigned priority and feasibility (1 = lowest, 5 = highest).

The activity was not a conventional questionnaire or survey for the BEDU round tables (sub-question 3), but rather a participatory process designed to explore local perceptions of beach-dune systems and their evolution over time. Through a series of structured questions (See Supplementary Materials), the exercise captured participants’ subjective interpretations and shared knowledge of the dynamics, management, and socio-ecological value of a specific coastal system they all knew well. The goal was to promote collective reflection and discussion around environmental change, rather than to collect isolated individual responses.

The session was organized into three small discussion groups, each composed of 3 to 5 participants (Figure 5), who worked with three different beach-dune systems: Els Muntanyans Beach (semi-natural beach), Northern Ebro Delta Beaches (semi-urban beaches), and Southern Ebro Delta Beaches (natural beaches). Participants interacted with questions printed on individual cards on a table, fostering open dialogue and collaborative reflection on each site’s specific characteristics and evolution. This format encouraged open dialogue, negotiation, and consensus-building, making it easy to revise or adjust answers collaboratively as the discussion evolved. The method favored deliberation and facilitated a deeper understanding of how people perceive changes in coastal landscapes and their underlying causes.

Figure 5.

Participants engaged in the participatory process (Case, discussing and reflecting on the questions collaboratively during the group session. (A) Co-creation process for Costa Daurada. (B) Co-creation process for Terres de l’Ebre I. (C) Co-creation process for Terres de l’Ebre II.

The participatory process unfolded in two rounds. In the first part, participants responded to questions after viewing aerial and ground-level photographs of the site in its current state. In the second round, once all questions had been discussed and answered, the groups were shown historical photographs from the early 20th century. Participants were then invited to reconsider and, if needed, modify their previous responses, considering this historical context. This temporal comparison helped to clarify long-term changes and tested the consistency of current perceptions against visual evidence from the past.

The content of the activity was organized into three thematic blocks—Beach (1), Dune (2), and Landscape (3)—each composed of eight questions, single-choice, multiple-choice and ranking questions (Supplementary Materials). The Beach block focused on changes in beach surface since 1950 and possible drivers of these dynamics, such as sediment supply, coastal infrastructure, and storm events. The Dune block addressed shifts in dune surface area, conservation status, and perceived threats like urbanization, trampling, and mechanical maintenance. Finally, the Landscape block explored the site’s broader visual and ecological qualities, asking participants to assess changes in the coastal landscape and identify the elements that most influence their perception, including biodiversity, natural surroundings, and artificial structures.

The analysis was structured in two phases. First, we examined whether participants modified their answers between the first and second rounds, following the presentation of historical photographs. Second, we assessed the quality of the responses, regardless of whether they were changed, to determine whether the revision improved understanding of the beach-dune system.

Table 1 presents data from stakeholder engagement events held in two locations in Catalonia, Spain: Vila-seca, Costa Daurada, and Tortosa, Terres de l’Ebre. These events occurred on 7 November 2023, and 18 December 2023. The stakeholders involved in these events were categorized into six groups: policy makers, local tourism offices, research centers/universities, conservation/civil organizations, private entrepreneurs, and private consultancies.

The table shows the number of representatives from each stakeholder group who attended each location and event and the total number of attendees. The events are denoted by three abbreviations: WCCC, WAEN, and BEDU.

In Vila-seca, Costa Daurada (7 November 2023), the WCCC event had 1 policy maker, 0 local tourism offices, 5 research centers/universities, 0 conservation/civil organizations, 0 private entrepreneurs, and 3 private consultancies, with a total of 22 attendees. The WAEN event had 3 policy makers, 1 local tourism office, 2 research centers/universities, 0 conservation/civil organizations, 3 private entrepreneurs, and 0 private consultancies. The BEDU event had 1 policy makers, 0 local tourism offices, 2 research centers/universities, 1 conservation/civil organizations, 0 private entrepreneurs, and 0 private consultancies.

In Tortosa, Terres de l’Ebre (18 December 2023), the WCCC event featured 4 policymakers, 0 local tourism offices, 1 research center or university, 0 conservation or civil organizations, 5 private entrepreneurs, and 0 private consultancies, with a total of 29 attendees. The WAEN event had 7 policy makers, 0 local tourism offices, 0 research centers/universities, 1 conservation/civil organization, 1 private entrepreneur, and 1 private consultancy. The BEDU event had 7 policy makers, 0 local tourism offices, 0 research centers/universities, 1 conservation/civil organization, 0 private entrepreneurs, and 1 private consultancy.

4. Results

This section provides a concise overview of the information collected during the workshops. The findings from all destinations are presented using graphical representations and summary tables.

4.1. Optimal Meteo-Climatic Conditions for Each Tourism Activity: Sub-Question 1

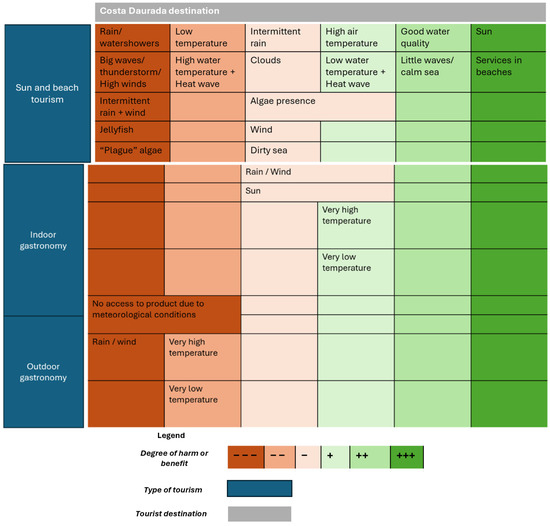

Figure 6 illustrates how meteo-climatic conditions impact different tourism activities. For the Costa Daurada tourist destination, territorial stakeholders have highlighted the following activities: sun and beach tourism (1), indoor gastronomy (2), and outdoor gastronomy (3).

Figure 6.

Identification of tourist activities and the degree of impact by meteorological and climatic conditions in the Costa Daurada.

The analysis results in the impact of climatic conditions on Costa Daurada’s tourism activities focus on sun and beach tourism and gastronomy. Regarding sun and beach tourism, extreme climatic conditions such as heavy rain, storms, and strong winds negatively affect the tourist experience, leading to problems such as dirty seawater and the proliferation of algae and jellyfish. On the other hand, optimal conditions—sun, high temperatures, and clean water—enhance the perceived quality of the destination and increase demand for services. Strong waves and high water temperatures can be detrimental, while calm conditions encourage visitor influx. This highlights the need for coastal destinations to prepare to mitigate climate change’s negative impacts.

Weather conditions also play a crucial role in indoor and outdoor gastronomy tourism. In indoor gastronomy, adverse weather primarily affects the supply chain, making it difficult to access fresh products, though it does not directly affect diner comfort. However, adverse conditions for outdoor gastronomy reduce the feasibility of enjoying outdoor dining. In contrast, sunny weather and mild temperatures enhance the outdoor dining experience, making these conditions key to its success. This analysis provides valuable insights for planning and adapting tourism activities in response to climate variability.

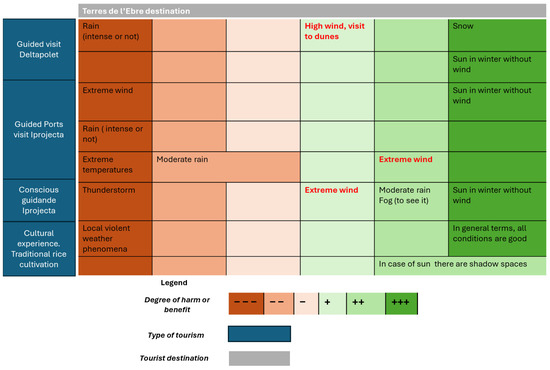

For the case of the tourist destination of Terres de l’Ebre (Figure 7), the territorial stakeholders who participated in the co-creation workshop identified various activities: the Deltapolet guided tour (1), the guided tour of the Parc Natural dels Ports by Iprojecta (2), the conscious guiding by Iprojecta (3), and the cultural experience of traditional rice cultivation (4)—considering that Iprojecta is a multidisciplinary team dedicated to guiding and environmental education.

Figure 7.

Identification of tourist activities and the degree of impact by meteorological and climatic conditions in Terres de l’Ebre.

The analysis results in the impact of climatic conditions on tourism activities in Terres de l’Ebre focus on guided tours and cultural experiences. The Ebro Delta and Ports Iprojecta guided tours are affected differently by climatic conditions. Heavy or moderate rain and extreme wind adversely affect the Delta, while winter sunshine and low wind intensity are favorable. In Ports Iprojecta, moderate rain and storms pose greater challenges and disrupt activities, while sunshine and low wind in winter enhance landscape appreciation.

Cultural experiences, such as conscious guiding and activities related to rice cultivation, are also sensitive to weather conditions. Storms and extreme weather events can negatively impact on these activities, although conditions are usually favorable overall. The presence of sun and shade on hot days improves the experience, and in some cases, moderate rain or fog can add visual value to the landscapes.

4.2. Adaptive Actions for Tourism Destinations, WCCC Perspective: Sub-Question 1

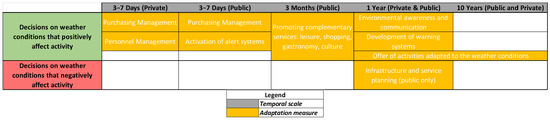

In an analysis of adaptation measures related to meteorological and climatic conditions in Costa Daurada, specific actions are identified by time horizon (Figure 8). For a 3 to 7-day period, both the private and public sectors manage purchases and personnel, and an alert system is activated to respond quickly to climatic conditions. No decisions are made for adverse conditions in this short timeframe.

Figure 8.

Adaptation actions identified by stakeholders in different time scales for the Costa Daurada destination.

In a 3-month horizon, public actions include informational campaigns to convince the population and promote complementary services such as leisure and gastronomy. In addition, infrastructure and services are planned to mitigate negative impacts. At the 1-year mark, alert systems are developed, and activities adapted to meteorological conditions are offered. Finally, in a 10-year horizon, environmental awareness and communication are prioritized to raise awareness about adaptation to climatic conditions.

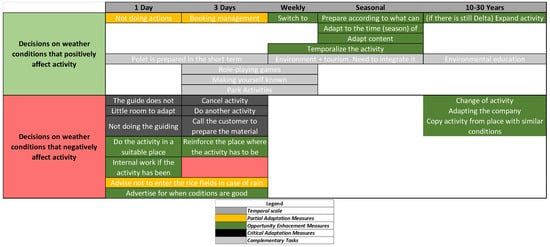

Regarding the adaptation measures identified in Terres de l’Ebre (Figure 9), for a 1-day horizon, no specific actions are taken for favorable weather conditions. In contrast, the guide does not get paid for adverse conditions, and activities are canceled, leaving little room for adaptation. For 3 days, reservations are managed and can be changed to viable activities. If conditions are adverse, a change in activity is chosen, although this also implies the need to adapt the business.

Figure 9.

Adaptation actions identified by stakeholders in different time scales for the Terres de l’Ebre destination.

Preparations are made weekly based on what can be done based on the season. This includes adjusting the content of activities and timing them. If conditions are unfavorable, the activity location is reinforced, and clients are informed of the need to prepare specific materials.

Integrating the environment with tourism and environmental education is emphasized at the seasonal level. Role-playing games, park activities, and strategies for becoming known are considered. Finally, over a 10 to 30-year horizon, it is proposed to advertise to promote activities in favorable conditions and replicate activities from places with similar conditions, ensuring greater adaptability over time.

4.3. Mitigation and Adaptive Measures Based on Their Priority and Feasibility, WAEN Perspective: Sub-Question 2

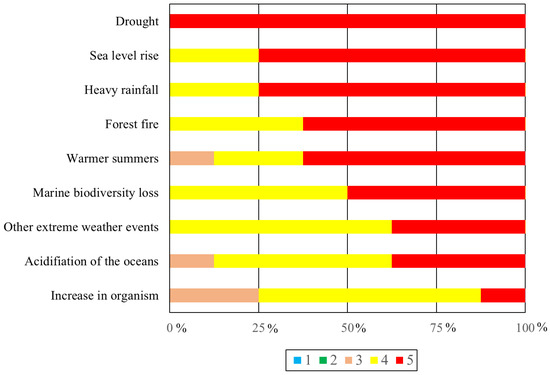

Figure 10 displays the workshop participants’ responses regarding their level of concern about physical hazards, primarily climatic and meteorological, exacerbated by climate change. No stakeholder reported a level of concern regarding the physical hazards identified during the workshop of 1 (no concern) or 2.

Figure 10.

Stakeholder concern levels regarding physical hazards identified during the workshop.

With its intensification and increased frequency, drought is the only hazard where all stakeholders share the highest concern (very concerned—5). Sea level rise and heavy rainfall also elicit very concerned responses from 75% of stakeholders. Almost two-thirds of participants consider the increased frequency and intensity of forest fires, and the rising temperatures, very concerning. On the other hand, stakeholders are not particularly concerned about the proliferation of organisms, ocean acidification, and other extreme meteorological events (i.e., heatwaves and marine storms).

The stakeholders also identified the impacts linked to the aforementioned physical hazards, which could diminish the attractiveness of tourist destinations and increase their vulnerability. Droughts result in water restrictions, and the stakeholders noted that droughts create heightened insecurity, affecting the enjoyment of the tourist experience and the overall product. Regarding the destination’s surroundings, droughts can lead to aquifer salinization, affecting water quality for various uses, including tourism. There is a close relationship between three physical hazards: rising sea levels, heavy rainfall, and extreme weather events. Sea level rise, caused by the thermal expansion of water and ice melting, is one of the most significant physical hazards to stakeholders. In addition to the risk of aquifer salinization, it directly impacts the beach. The beach’s regression, loss, or disappearance is accompanied by damage to infrastructures and buildings. Stakeholders were also concerned about the impact of extreme weather events, such as heavy rainfall, on infrastructure and the potential for these events to lead to the cancellation of scheduled tourist activities. The cancellation of tourist activities, in turn, can lead to a decrease in the number of tourists and visitors, ultimately affecting the destination’s competitiveness and ability to offer a high-quality tourism product. The cancellation of activities, the decline in tourist numbers, and the loss of competitiveness are also associated with rising temperatures, particularly during the summer or peak season, which impacts tourist comfort.

Increasing temperatures are also linked to two other physical hazards that can negatively impact tourist destinations: forest fires and the proliferation of disease-carrying organisms. This latter hazard can significantly impair tourist satisfaction during their stay, either through the emergence of invasive species that restrict certain activities, such as certain algae that affect swimming, or through the emergence of infectious diseases that pose a risk to humans. Regarding the increased frequency and intensity of forest fires, the danger is centered in destinations where natural areas play a significant role, whether protected or not. The consequences are a loss of landscape quality and natural heritage. The stakeholders interviewed perceive that these fires can significantly impact ecosystem modification, accessibility loss, and outdoor tourist activities in natural areas. Forest fires (or a high risk) mean access restrictions to certain areas, especially natural ones, and therefore prevent planned activities in these spaces from being carried out. Finally, the modification of marine ecosystems and seawater acidification are of less concern to stakeholders. However, they highlight the impacts of the loss of water quality, the decline in marine species diversity, and the potential effects of aquatic and underwater activities.

Table 2 summarizes the measures proposed by the stakeholder for climate change mitigation and adaptation related to water and energy, determining and ranking their priority and feasibility. The first measures group include those classified as high priority and highly feasible. Awareness and sensitivity campaigns on water use stand out, whether aimed at tourists or the resident population of the tourist destination, promoting education on water consumption and conservation habits. Reducing or conserving water consumption and harnessing rainwater are other measures that stakeholders consider priorities and are easily achievable. A second group of measures would include those proposed by stakeholders and considered highly or very feasible, but of medium priority. These measures are more focused on tourism activities and aim to diversify the supply and promote those with a low water footprint. Improving governance in the destination is also a highly viable measure, but of medium priority. Although stakeholders consider it highly viable, reducing the use of chemicals in water is often viewed as a low priority. A third group of measures has medium priority and feasibility. This group encompasses measures aimed at enhancing the efficiency of the distribution network, managing water for reuse, and monitoring and tracking consumption at the local level. A fourth and final group of measures consists of those that, despite having high or very high priority, are of medium or low feasibility. The stakeholders identified up to four different measures. On the one hand, public and private stakeholders need to make commitments to manage and conserve water resources more effectively in the destination. On the other hand, stakeholders point to more executive measures, such as constructing plants to supply both the tourism sector and the local population, and structural modifications to buildings and infrastructure to utilize rainwater. Finally, the reuse and/or treatment of greywater is a measure that, according to the stakeholders participating in the workshop, has medium priority and low feasibility due to its complex implementation.

Table 2.

Measures identified by stakeholders for the water and energy spheres linked with the tourism sector.

Regarding the proposals for mitigation of climate change and adaptation related to energy, the first group of measures would include those highly prioritized for implementation and are viable. The stakeholders agreed that the primary measure in this regard should be tightening current regulations regarding compliance with energy consumption and savings measures, with the consequent application of sanctions. Regarding sanctions for non-compliance with current regulations, they explained that these regulations are sometimes implemented late, or violations are not detected. They also stated that incentives for compliance with current legislation and regulations would be more effective than sanctions. Monitoring and tracking energy consumption is another notable measure in this classification, as it would support decision-making related to energy resource planning and management. On the other hand, they believed it was equally essential to continue promoting and implementing awareness and education campaigns on consumption habits and energy conservation, not only from a tourism perspective, but also to impact society at large, in order to transfer these good habits to individuals when consuming tourism products.

A second group of measures would include those with high and very high viability and those with high priority. Among the measures highlighted is the consensus on promoting low-energy tourism activities. The tourism sector must rethink the activities it offers its tourists and prioritize those that require low energy consumption or less energy dependence. Other measures within this group aim to reduce energy consumption, which can be achieved by establishing or investing in more efficient infrastructure or by modifying the infrastructure of the tourist destination to lower energy consumption. The proposal to contract energy from renewable sources would fall within this group of measures. A third group of measures considers those that, despite having high or very high priority, are considered moderately feasible. Participating stakeholders indicated that improving tourism mobility management within the destination and adopting commitments by the private sector are somewhat challenging to implement. Technological innovations are viewed as a basic measure, but compared to the previous measures considered in this group, they are perceived as somewhat challenging to implement and therefore less feasible. It is worth noting that stakeholders consider private stakeholders’ commitment to the optimal management and use of energy resources more feasible than that of public stakeholders. The adoption of commitments by public stakeholders, along with the internal production of green or renewable energy, which should lead to the destination’s energy self-sufficiency, are measures that, despite being considered high priority, are viewed as highly difficult to implement and, therefore, have low feasibility.

The final group of measures identified by the stakeholders participating in the workshop consists of those classified as high-priority measures but with low or very low feasibility. These are more comprehensive measures related to how tourists arrive at the destination and the need to change the current economic model to prioritize sustainability.

4.4. Perception of Beach Dune Systems in Tourist Destinations, BEDU Perspective: Sub-Question 3

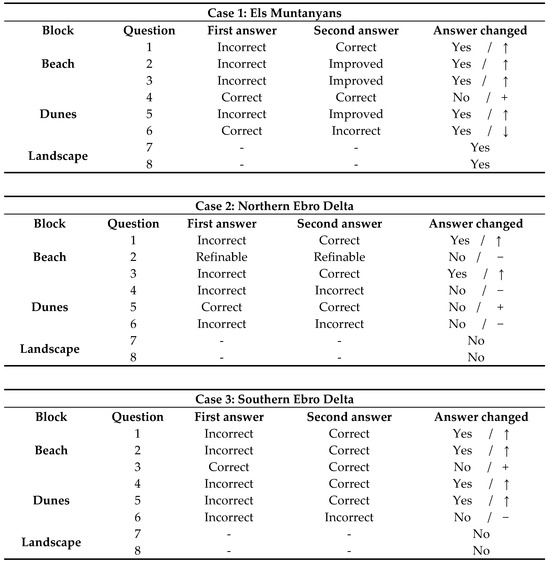

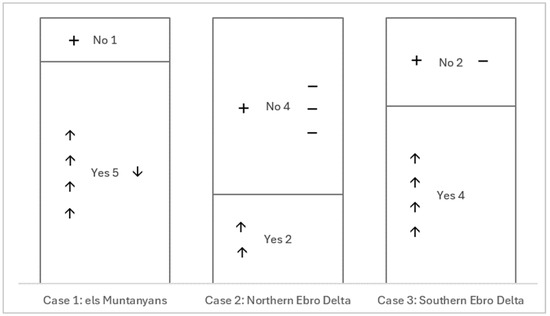

The results reveal significant differences across the three case studies. In Case 1 (els Muntanyans Beach), participants modified 7 out of 8 possible answers between the two rounds. In contrast, in Case 2 (Northern Ebro Delta beaches), only 2 answers were changed, while in Case 3 (Southern Ebro Delta beaches), participants changed 4 answers, representing 50% of the total (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Analysis of the results obtained during the participatory workshop (Sup. Mat. X) based on stakeholders’ knowledge of the different thematic blocks before (first answer) and after (second answer) being shown historical images. Note that responses related to the landscape block were not evaluated as right or wrong, as they reflect subjective perceptions in which all options are considered valid. The “answer changed” label indicates whether a change occurred between the two rounds and whether it resulted in increased (↑) or decreased (↓) knowledge. In cases where no change occurred, it is indicated whether participants demonstrated knowledge (+) or not (−) of the topic.

Focusing specifically on the Beach and Dune thematic blocks—those most directly related to system dynamics—the number of changes increased in all cases except Case 2, which still showed only 2 modified responses (Figure 12). In nearly all instances where changes occurred (10 out of 11), the revisions led to more accurate or informed answers, indicating an improved understanding of coastal processes. Case 2 stands out negatively, as participants retained 4 incorrect answers into the second round, suggesting a lower interpretative capacity or a more deeply ingrained prior perception that was less influenced by the visual comparison. This may also point to a more limited initial knowledge base.

Figure 12.

Number of changed answers between the two rounds. “Yes” indicates the number of questions that participants changed their answer and “No” indicates the number of questions that participants did not change it. Arrows indicate if the change resulted in increased (↑) or decreased (↓) knowledge. In cases where no change occurred, it is indicated whether participants demonstrated knowledge (+) or not (−) of the topic.

Overall, the three cases demonstrate that exposure to historical photographs had a clear positive effect on participants’ understanding of the beach-dune system. Those who revised their answers showed significant improvement, highlighting the value of this participatory methodology as a tool for fostering collective reflection and deeper insight into environmental change in coastal dynamics.

Responses related to the Landscape block were not necessarily linked to participants’ level of knowledge, as they reflect subjective perceptions where all options are equally valid. In this sense, only one group—Case 1—modified their responses upon the second round of questioning, while the other groups maintained their initial answers when asked again about the landscape values.

4.5. Key Takeaways on Climate Adaptation for Tourism: Integrated Perspectives on Optimal Conditions, Adaptive Actions, and Stakeholder Perceptions

Guided by the main research question—how the co-creation of integrated climate services, water and energy management, and beach-dune conservation can foster behavioral change towards climate-resilient tourism—this study’s findings address the three sub-questions and offer key insights for climate adaptation in tourism.

Regarding the first sub-question on the influence of meteo-climatic conditions on tourism activity, the results highlight the critical importance of identifying optimal weather and climate conditions for each tourism type, as these factors profoundly affect visitor experiences and the sustainability of tourism operations. This underlines the need for adaptive actions informed by a comprehensive understanding of weather, climate, and ongoing climate change to protect tourism destinations over the long term.

In response to the second sub-question, focusing on necessary adaptation measures related to water and energy management, the research emphasizes prioritizing practical strategies within tourism infrastructure to enhance resilience and sustainability. Stakeholders consistently recognized the importance of integrated water and energy management as central components of successful climate adaptation efforts.

Concerning the third sub-question, which explores the impact of historical photographs on stakeholder perceptions, the findings reveal that such visual tools substantially increase awareness of the ecological importance of beach-dune systems. This elevated understanding reinforces stakeholder commitment to preserving these natural defences, crucial for protecting coastal tourism destinations from erosion and maintaining their attractiveness.

Together, these insights confirm that an integrated, coordinated approach—engaging stakeholders across climate services, resource management, and ecosystem conservation—is essential for effective climate adaptation in tourism. Such collaborative engagement is fundamental to fostering behavioral change that supports the long-term resilience and sustainability of coastal tourism destinations.

5. Discussion

This study contributes to expanding the discussion on the integration of climate services, water and energy management, and coastal ecosystem conservation within tourism studies [3,7].

In times of widespread climate misinformation [91] it becomes crucial for economic sectors such as tourism to strengthen their adaptive capacity to both climate variability and change [3,6,90].

The findings support the assertion that tourism is a climate-sensitive sector in which environmental and behavioral dimensions are deeply interconnected [2,3,45]. The results from stakeholder interactions along the Catalan coast demonstrate that the integration of environmental management tools—when embedded in co-creation processes—can enhance awareness and motivation for behavioral change toward sustainable practices. This supports recent literature calling for participatory approaches that couple technical adaptation with social engagement to achieve effective resilience [90].

Our results indicate that stakeholders perceive climate information and meteorological patterns as key determinants of tourism planning, echoing prior studies that recognized weather and climate as both limiting factors and valuable resources for tourism [45,46,47,92]. In particular, seasonal shifts, extreme events, and water limitations are increasingly altering not only the attractiveness of destinations but also the operational strategies of local businesses and municipalities [90]. The co-creation process revealed growing interest among tourism operators and policy actors in adopting adaptive and energy efficiency measures, in line with previous findings on the importance of sustainable resource management for destination resilience [25,26].

An innovative aspect of this work lies in exploring how visual tools, such as historical photographs, influence stakeholder perceptions of dune ecosystem degradation. Consistent with previous research [77,78], participants recognized the symbolic and ecological value of coastal dunes as both tourism assets and natural buffers against climate impacts. The visual evidence helped translate abstract climate risks into tangible local challenges, prompting greater willingness to participate in dune restoration and coastal adaptation actions. These perceptual shifts reinforce the role of experiential and place-based communication in driving behavioral change toward conservation goals.

Furthermore, this research underscores that fostering behavioral change in tourism requires continuous dialogue between science, governance, and local stakeholders. Aligning with the Catalan Climate Change Adaptation Strategy (ESCACC30) and the EU 2050 Climate Strategy, our results advocate for systemic approaches where integrated management of climate services, water, energy, and beach-dune systems become part of destination governance. By situating adaptive measures within a participatory co-creation process, this study helps translate global climate and sustainability goals—such as SDGs 6, 7, 12, 13, and 15—into place-specific actions that strengthen resilience along the Catalan coast.

This study is the first, at a regional scale, to integrate climate services, water and energy management, and beach-dune conservation into a single framework applied to two coastal tourism destinations. By linking these three spheres through co-creation, it advances a holistic perspective on climate-resilient tourism.

However, the results are influenced by stakeholders’ evolving perceptions and the specific local context of the Catalan coast. While the proposed methodology is easily replicable in other coastal areas with dune systems and tourism, outcomes may differ depending on stakeholder engagement and environmental conditions.

Limitations related to sample size, representativeness, and locality also restrict broad generalization. Moreover, the unique socio-environmental characteristics of the Catalan coast strongly influence the applicability of our conclusions to other contexts. Potential biases inherent in the consensus-based co-creation approach are also acknowledged.

Despite these limitations, the approach offers a valuable, transferable model for fostering integrated adaptation and behavioral changes in coastal tourism planning. Future studies should include comparative analyses in other regions to validate the universality and broader relevance of these findings.

Future research could expand upon this study by designing and administering structured questionnaires informed by current stakeholder perceptions, enabling multidimensional statistical analyses to further explore causal relationships between meteorological conditions, resource management strategies, and behavioral change in coastal tourism.

In short, most existing studies tend to focus on the impact of single systems on the tourism industry, such as climate services or coastal ecosystem conservation in isolation. Our study fills this gap by adopting a multi-system integrated perspective that links climate services, water and energy management, and beach-dune conservation through a co-creation process. This holistic approach advances the theoretical understanding by recognizing the complex interdependencies among these systems and how they jointly influence climate-resilient tourism. It thus provides a comprehensive framework that moves beyond siloed analyses, offering richer insights into integrated adaptation strategies and stakeholder behavior in coastal tourism contexts.

6. Conclusions

This research was guided by the main question of how the co-creation of integrated climate services, water and energy management, and beach-dune conservation can foster behavioral change among stakeholders towards climate-resilient tourism along the Catalan coast. To answer this, we explored three sub-questions focusing on (1) the influence of meteo-climatic conditions on tourism activity, (2) stakeholder perceptions of mitigation and adaptation measures, and (3) the role of historical photographs in shaping awareness of beach-dune systems.

Regarding the influence of meteo-climatic conditions on tourism activities (sub-question 1), our findings reveal that extreme weather events such as storms and heatwaves significantly impact recreational and cultural tourism in the Costa Daurada and Terres de l’Ebre regions. These climatic challenges highlight the vulnerability of traditional sun-and-beach tourism, emphasizing the need to diversify tourism offerings and integrate sustainable practices that mitigate negative impacts while leveraging favorable conditions. This directly responds to the first sub-question by demonstrating how meteo-climatic factors shape tourism dynamics and opportunities for climate-resilient adaptation.

With respect to stakeholders’ views on mitigation and adaptation strategies related to water and energy management (sub-question 2), this study underscores the priority of adopting sustainable technologies and integrated resource management. Stakeholders emphasized that the sustainable use of resources is fundamental for managing tourism destinations in the context of climate change. This finding addresses the second sub-question by identifying actionable strategies that align with climate resilience goals and stakeholder priorities.

Concerning the role of historical photographs in raising awareness and shaping perceptions of beach-dune ecosystem conservation (sub-question 3), our results show that using such visual tools enhances stakeholders’ understanding of ecosystem relevance and promotes willingness to support restoration and conservation efforts. Given the alarming degradation rates of dune ecosystems along the Catalan coast, this contributes valuable insight into communication strategies that foster environmental stewardship, thereby answering the third sub-question.

Overall, these findings collectively answer the main research question by illustrating how engaging stakeholders in co-creation processes that integrate climate services, resource management, and ecosystem conservation can effectively foster behavioral change towards climate-resilient tourism along the Catalan coast. The integration of diverse perspectives has enabled the identification and promotion of innovative, sustainable tourism experiences aligned with regional environmental realities.

In summary, this research demonstrates that a holistic approach combining climate adaptation, sustainable tourism diversification, ecosystem preservation, and resource-efficient management is vital to ensure the viability of coastal tourism amidst increasing climate variability. Only through collective behavioral change at all levels, fostered by inclusive co-creation, can the tourism industry navigate the challenges of climate change and secure a sustainable future. Overall, these findings collectively answer the main research question by showing how co-creation and integrated management can foster behavioral change for climate-resilient tourism.

Importantly, while this study focuses on the Catalan coast, the research questions and findings possess broader applicability, offering valuable insights into how collaborative, integrated approaches to climate adaptation can inform resilient tourism development in diverse coastal regions globally facing similar climate risks and sustainability challenges.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su172210163/s1, Survey.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B.-C., Ò.S., M.T.R.-S. and C.G.-L.; methodology, Ò.S., C.G.-L., M.T.R.-S. and A.B.-C.; formal analysis, A.B.-C., C.G.-L., M.T.R.-S. and Ò.S.; investigation, A.B.-C.; resources, E.A., Ò.S., G.B. and C.M.; data curation, A.B.-C., C.G.-L., M.T.R.-S. and Ò.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B.-C.; writing—review and editing, A.B.-C., Ò.S., M.T.R.-S., C.G.-L., C.M., M.T., G.B. and E.A.; visualization, C.G.-L., A.B.-C. and Ò.S.; supervision, E.A.; project administration, A.B.-C.; funding acquisition, E.A., Ò.S., C.M. and G.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Impetus project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under Grant Agreement No. 101037084, which was funded in the EU Horizon 2020 Green Deal call.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study is waived for ethical review as Law 14/2007 on Biomedical Research by Institution Committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy or restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contributions of Itziar Labairu and Georgina Giné in the early stages of this research. We sincerely thank all stakeholders for their valuable participation and input, which were essential to this research. We want to acknowledge the Servei Meteorològic de Catalunya for their valuable contribution to the knowledge pills, which greatly enrich this research.

Conflicts of Interest

Co-author Maria Trinitat Rovira-Soto was employed by the EURECAT Centre Tecnològic de Catalunya but does not have any conflict of interest. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WAEN | Water and Energy |

| BHCH | Behavioral change |

| WCCC | Weather, Climate, and Climate Change |

| BEDU | Beach-dune system |

References

- Ebrahimzadeh, I.; Ziaee, M.; Farzin, M.R. Feasibility Studies of the West Coast Sample of Tourism (Chabahar); Geosciences Research Institute of Sistan and Baluchestan: Zahedan, Iran, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, D.; Lemieux, C. Weather and climate information for tourism. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2010, 1, 146–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becken, S. The importance of climate and weather for tourism: Literature review. Land Environ. People 2010. Available online: https://researcharchive.lincoln.ac.nz/server/api/core/bitstreams/868f02cb-bcea-4ccf-8db1-038839a2ec7b/content (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Gómez-Martín, M.B. Weather, climate and tourism: A geographical perspective. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 571–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas, C.R. Tourism climatology: Evaluating environmental information for decision making and business planning in the recreation and tourism sector. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2003, 48, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, D.J.; Lemieux, C.J.; Malone, L. Climate services to support sustainable tourism and adaptation to climate change. Clim. Res. 2011, 47, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damm, A.; Köberl, J.; Stegmaier, P.; Alonso, E.J.; Harjanne, A. The market for climate services in the tourism sector–An analysis of Austrian stakeholders’ perceptions. Clim. Serv. 2020, 17, 100094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, M.; Hardy, D. Economic drivers of change and their oceanic-coastal ecological impacts. In Ecological Economics of the Oceans and Coasts; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2008; Volume 15, pp. 187–209. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, D.; Sim, R.; Simpson, M. Sea level rise impacts on coastal resorts in the Caribbean. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 883–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garola, A.; López-Dóriga, U.; Jiménez, J.A. The economic impact of sea level rise-induced decrease in the carrying capacity of Catalan beaches (NW Mediterranean, Spain). Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2022, 218, 106034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigano, A.; Goria, A.; Hamilton, J.; Tol, R.S. The Effect of Climate Change and Extreme Weather Events on Tourism; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2005; pp. 173–190. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, N.A.; Tobin, R.C.; Marshall, P.A.; Gooch, M.; Hobday, A.J. Social vulnerability of marine resource users to extreme weather events. Ecosystems 2013, 16, 797–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, M.M.G.; Leon, C.J.; García, C.; Lam-González, Y.E. Assessing the climate-related risk of marine biodiversity degradation for coastal and marine tourism. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2023, 232, 106436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bows, A.; Anderson, K.; Peeters, P. Air transport, climate change and tourism. Tour. Hosp. Plan. Dev. 2009, 6, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michailidou, A.V.; Vlachokostas, C.; Moussiopoulos, Ν. Interactions between climate change and the tourism sector: Multiple-criteria decision analysis to assess mitigation and adaptation options in tourism areas. Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukadin, I.M.; Islam, N.U.; Baus, D.; Krešić, D. Capacities of adaptation and mitigation measures in tourism to answer challenges of the climate crisis. In Tourism in a VUCA World: Managing the Future of Tourism; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2024; pp. 43–63. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Coca-Stefaniak, J.A.; Nguyen, T.H.H.; Morrison, A.M. Sustainable tourist behavior: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 3356–3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olya, H.; Kim, N.; Kim, M.J. Climate change and pro-sustainable behaviors: Application of nudge theory. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 32, 1077–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, D.; Demeter, C.; Dolnicar, S. The comparative effectiveness of interventions aimed at making tourists behave in more environmentally sustainable ways: A meta-analysis. J. Travel Res. 2024, 63, 1239–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, A.F.; Balakrishnan, J. Shaping sustainable tourism: How minimalism and citizenship behavior influence tourists’ proenvironmental behavior. Consum. Behav. Tour. Hosp. 2024, 19, 590–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, R. Sustainable Tourism Development: A Systematic Literature Review of Best Practices and Emerging Trends. Int. J. Multidiscip. Approach Sci. Technol. 2024, 1, 97–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, P.; Correia, A. Beyond sun and sand: How the Algarve region is pioneering innovative sustainable practices in tourism. In From Overtourism to Sustainability Governance; Routledge: London, UK, 2024; pp. 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Vashishth, T.K.; Sharma, V.; Agarwal, S.; Gupta, N.; Singh, S.; Sharma, R. Embracing the current challenges in sustainable waste management in tourism and hospitality. In Hotel and Travel Management in the AI Era; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 219–256. [Google Scholar]

- Kaseva, M.E.; Moirana, J.L. Problems of solid waste management on Mount Kilimanjaro: A challenge to tourism. Waste Manag. Res. 2010, 28, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.H.; Lee, S.S.; Perng, Y.S.; Yu, S.T. Investigation about the impact of tourism development on a water conservation area in Taiwan. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.; Chompreeda, K. The relative effect of message-based appeals to promote water conservation at a tourist resort in the Gulf of Thailand. Environ. Commun. 2015, 9, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdoğan, S.; Gedikli, A.; Cevik, E.I.; Erdoğan, F. Eco-friendly technologies, international tourism and carbon emissions: Evidence from the most visited countries. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 180, 121705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sushchenko, O.A.; Kozubova, N.V.; Prokopishyna, O.V. Eco-friendly behavior of local population, tourists and companies as a factor of sustainable tourism development. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 7, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.L. Tourists’ perceptions of environmentally responsible innovations at tourism businesses. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasim, A. Socio-environmentally responsible hotel business: Do tourists to Penang Island, Malaysia care? J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 2004, 11, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]