Abstract

To enhance the operational efficiency of fuel cell engineering vehicles in transportation, reliable energy management strategies (EMSs) are essential for optimizing fuel consumption and power distribution. In this paper, we propose a novel energy management framework that utilizes a reinforcement learning-based adaptive hierarchical equivalent consumption minimization strategy (ECMS) to regulate fuel cell/battery hybrid system. The structure integrates deep Q-network (DQN), fuzzy logic, and ECMS algorithms and employs a long short-term memory neural network for working condition prediction. By combining DQN with the equivalence factor obtained using the battery state of charge penalty function and adjusting it using a fuzzy logic controller, the stability of the subsequent ECMS is enhanced. In a simulation environment, the proposed EMS achieves a 97.44% fuel economy compared to the dynamic programming-based global optimized EMS. Experimental findings indicate that the hierarchical ECMS effectively decreases the equivalent hydrogen consumption by 3.38%, 9.12%, and 16.39% compared to the adaptive ECMS, DQN-based ECMS, and classic ECMS, respectively. Therefore, the proposed methodology offers superior economic benefits.

1. Introduction

Recently, the frequency of extreme weather events has risen, indicating the increasing impact of global warming. To mitigate the consequences of climate change, there is an urgent need for clean energy to reduce carbon emissions. Environmental conservation efforts in the transportation sector are vital in this transition [1]. Engineering vehicles have traditionally presented challenges in reducing carbon emissions. The trend of electrification has become increasingly prominent in the modern transportation sector, with fuel-cell hybrid electric vehicles (FCHEVs) emerging as a viable alternative. The concept of the FCHEV was proposed by McElroy in 1983 and is a type of hybrid electric vehicle (HEV). Currently, combinations of fuel cell/battery and fuel cell/supercapacitor systems are being employed among the FCHEVs [2]. In a hybrid system, fuel cells and power batteries or supercapacitors are employed together to provide power, offering multiple operating modes and numerous advantages for hybrid vehicles [3,4,5]. However, due to variations in the optimal operating ranges of different power sources, energy management strategies (EMSs) are designed to optimize the allocation of each power source based on vehicle operating conditions. Consequently, EMSs have emerged as an important area in FCHEV research [6].

EMSs can be broadly grouped into rule-based, optimization-based, and intelligent approaches. [7]. Strategies based on rules rely on predefined rules rather than aiming for optimality and are often based on expert knowledge [8,9,10,11]. Although widely used in hybrid vehicles [12], such as fuzzy logic algorithms [13], rule-based strategies generally provide suboptimal control and lack adaptability. Optimization-based algorithms include global-based EMS [14] and local-based EMS [15], such as dynamic programming [16,17], heuristic dynamic programming [18], adaptive dynamic programming [19], an equivalent consumption minimization strategy (ECMS) [20], and model predictive control (MPC) [21,22]. As a representative of global optimization, dynamic programming computes the globally optimal sequence of control actions for a specified driving cycle. However, due to its high computational cost and low applicability in real-time scenarios, dynamic programming is generally used in EMS research as an evaluation criterion for other algorithms [23,24]. To address the challenges of the high cost and real-time application of dynamic programming, the ECMS algorithm enhances efficiency by optimizing the equivalence factor at each time step, thus minimizing fuel consumption across the entire driving cycle.

The ECMS estimates a univariate Hamiltonian cost function for equivalent fuel consumption by combining fuel consumption and the battery’s comparable electrical energy consumption. The key variable, the equivalence factor, reflects the equivalent scale value of electrical energy and fuel energy [25]. The ECMS with online equivalence-factor tuning is termed an adaptive ECMS (A-ECMS). Sinoquet et al. [26] derived the optimal constant value of the equivalence factor through offline optimization of the dynamic programming results. Zhang, L et al. [27] explored the coordination between speed planning and energy management and proposed a co-optimization method. This approach addresses the significant computational load and complexity associated with optimizing the coordination relationship.

Recent advances in artificial intelligence have accelerated the adoption of machine-learning-based control strategies, notably reinforcement learning. At the same time, many scholars have combined clustering algorithms with the research on HEVs [28]. Reinforcement learning algorithms combine the strengths of global optimization and real-time optimization. By employing reinforcement learning algorithms, significant progress has been made in energy management in different types of HEVs [29,30]. For example, T. Liu et al. demonstrated the superior fuel economy performance of the Q-learning algorithm in HEVs [31]. In addition, by using deep neural networks to fit multi-dimensional state inputs, deep reinforcement learning (DRL) is formed, which is more efficient than reinforcement learning. When dealing with FCHEVs, X. Tang et al. [29] minimized hydrogen consumption by using a deep Q-network (DQN) with a priority experience replay mechanism. In addition, to consider battery usage in FCHEVs, a collaborative optimization framework based on the DRL method has been proposed to achieve a tradeoff between battery size and EMS [32]. To overcome the limitations of discrete action spaces in DQN for FCHEV energy management, researchers have adopted continuous-control reinforcement learning methods. In particular, deterministic actor–critic algorithms such as the Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) [33,34] and Twin Delayed DDPG (TD3) [35] enable direct optimization over continuous power-split actions, mitigating quantization errors and improving control smoothness.

Currently, forward-looking scholars have begun to explore approaches to combining the DRL algorithm with other algorithms to achieve a better fuel efficiency. He et al. [36] innovatively used a well-trained DDPG neural network as an efficient planner for SoC references and then adopted the MPC algorithm to make decisions. Moreover, ref. [37] designed an energy management approach that couples Q-learning and the ECMS, which accelerates convergence of the algorithm and reduces the power volatility of the fuel cell.

Some studies have applied reinforcement learning to the real-time adjustment of the equivalence factor. To account for the interaction between the goal-oriented agent and the uncertain environment, an adaptive HEV hierarchical EMS is proposed by estimating the equivalence factor in the existing ECMS using a data-driven DDPG framework [38]. Sun et al. [39] proposed an A-ECMS based on driving behavior and used DRL based on spatial division for decision-making, and Lin et al. [40] proposed an adaptive hierarchical ECMS using the PPO algorithm for equivalent coefficient selection, but it lacks experimental verification.

Prior studies show that DRL has markedly advanced energy management for hybrid vehicles. Researchers also combine DRL with other algorithms. However, there are still the following deficiencies that need further exploration:

(1) In the algorithm combining DRL and the ECMS, how to reduce the influence of RL’s own shortcomings on the overall strategy is not considered [41]. For example, reinforcement learning itself includes unstable factors such as overfitting, overestimation, and hyperparameter fragility, which affect the solution of the equivalence factor.

(2) The existing DRL and ECMS combined algorithm is limited to the analysis of classic operating conditions of hybrid passenger vehicles, and it lacks analyses and research on the operating conditions of engineering vehicles.

(3) There is a lack of algorithms that combine DRL and the ECMS to predict operating conditions based on historical information. Many studies have shown that predictive information has a huge impact on energy management strategies [42,43,44].

In order to make up for the shortcomings of the above research, we proposed an adaptive hierarchical ECMS based on reinforcement learning. This method considers real-time operating conditions and uses a long short-term memory (LSTM) neural network to predict future FCHEV power demand. With access to a preview of power demand, DQN is used to output the first equivalence factor, and the SoC penalty function is used to adjust the equivalence factor online to obtain the second equivalence factor. These two equivalence factors are processed by a fuzzy logic controller to output the optimal equivalence factor, which becomes the key parameter of the equivalent consumption minimum strategy. With the required power and optimal equivalence factor known, the ECMS decides to output fuel cell power, and FCHEV’s actual power is used for subsequent cycle calculations.

In this paper, we propose an adaptive hierarchical intelligent EMS for engineering vehicles with minimum equivalent consumption based on reinforcement learning. This paper makes the following key contributions.

(1) A hierarchical adaptive ECMS framework is proposed, in which the upper layer focuses on equivalence factor optimization and the lower layer performs instantaneous ECMS power distribution. This layered design separates strategic optimization from real-time decision-making, improving coordination efficiency and scalability under complex working conditions.

(2) The power prediction model is established by using the loader V-type working data and the LSTM neural network to provide accurate power values for subsequent calculations. The agent learns and updates the model by accumulating historical power data to improve the prediction accuracy.

(3) An intelligent equivalence factor optimization mechanism integrating DQN reinforcement learning, SoC-based penalty adjustment, and fuzzy logic fusion is established. By fusing the DQN-derived and SoC-derived equivalence factors, the system achieves balanced adaptation between global optimization and real-time stability, improving control robustness and energy economy.

The remainder of this article is arranged as follows: Section 2 provides a comprehensive description of the system model, including its components and properties. In Section 3, the reinforcement learning-based adaptive hierarchical ECMS for a fuel cell/battery hybrid system is discussed. In Section 4, simulation results and a discussion are provided. Experimental results and discussions are then presented in Section 5. Section 6 concludes this paper with a summary.

2. System Model

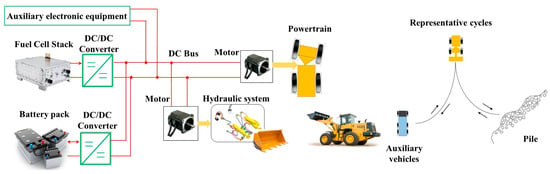

In this section, we discussed powertrain models and hybrid power system models. The main structure of an FCHEV consists of fuel cells and battery packs, as depicted in Figure 1. The fuel cell outputs energy by a unidirectional DC/DC converter, and the battery stores and outputs energy based on the vehicle’s power demand and the fuel cell’s output power. The power system of engineering vehicles comprises two main parts: the propulsion system and the operating system. The powertrain configuration includes an electric motor, drive axle, reducer, and wheels. The operating system utilizes an electrohydraulic system for bucket operation. The total power demand of an engineering vehicle equals the sum of propulsion-system demand and operating-system demand.

Figure 1.

Structure of the FCHEV.

We established an engineering-vehicle powertrain model based on dynamics theory. However, unstable conditions, such as tire slip due to unpredictable shovel resistance and driver behavior, may occur. Therefore, simplified dynamical system models are often used. The power system model of engineering vehicles can be developed using an energy balance equation:

where PFC, PB, PD, and PH represent the fuel cell power, battery power, power system motor power, and hydraulic system motor power, respectively. In the formula, ηDCFC and ηM represent the unidirectional DC/DC converter’s efficiency on the fuel cell side and the power system motor and hydraulic system motor’s efficiency.

We developed models for fuel cells, batteries, and DC/DC converters. To ensure the normal operation of the energy management system, we established the fuel cell’s polarization and battery models. These models are widely used in research on the fuel cell/battery hybrid system. The fuel cell model established in this article can be expressed as follows:

where q1, q2, and q3 are the fitting coefficients, and NFC, MH2, ne, F, and IFC, respectively, represent the fuel cell unit number, molar mass of hydrogen, electron number, Faraday’s constant, and fuel cell working current.

In the hybrid power system, the battery must be able to handle instantaneous excessive power changes in engineering vehicles. The system adopts a modular lithium-ion battery architecture in which cells are connected in series to form each module, and multiple modules are paralleled to assemble the power pack. Here, the battery model is simplified into an improved PNGV model by not considering the battery’s complex electrochemical process. The battery model can be expressed as follows:

where UB, UOCV, IB, and RP, respectively, represent the output voltage, open circuit voltage, output current, and battery’s internal resistance, UP signifies the initial polarization voltage, SoC represents the battery’s state of charge, and QB denotes the battery’s capacity.

We assume the load power is known at each instant. A DC–DC converter then regulates the battery’s terminal voltage and power and controls the fuel cell output. The DC/DC converter’s efficiency significantly affects the overall performance of the hybrid system; thus, a model is commonly built to characterize its properties. The model can be expressed as follows:

where PDCOUT and PIN represent the DC/DC converter’s output power and input power, UDCOUT and UDCIN represent the DC/DC converter’s output voltage and input voltage, and ηDC represents the DC/DC converter’s efficiency.

3. Energy Management Strategy Development

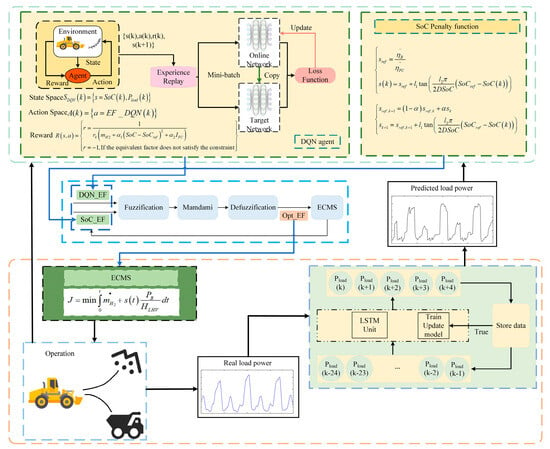

Based on the adaptive hierarchical ECMS (H-ECMS) of reinforcement learning, we developed the FCHEV energy management structure based on LSTM, DQN, fuzzy logic, and ECMS methods.

3.1. ECMS Energy Management Framework Based on Hierarchical Structure

The proposed method uses an ECMS algorithm to optimize the fuel cell’s output power. The objective function is defined as

In the formula, mH2 represents the fuel cell’s hydrogen consumption, PB represents battery power, s(t) represents the equivalent factor, and HLHV is hydrogen’s low calorific value.

The energy management of hybrid power engineering vehicles involves optimizing multiple constraints. It further incorporates energy-use metrics, stack life, battery degradation, and hard constraints of the powertrain and chassis. These constraints are expressed as follows:

where SoCmax and SoCmin are the battery SoC constraints. IBmax and IBmin are the battery current constraints. ΔIBmax and ΔIBmin are the maximum and minimum currents of the lithium battery. PFCmax and PFCmin are the maximum and minimum powers of the fuel cell. IFCmax and IFCmin are the maximum and minimum currents of the fuel cell. ΔPFCmax and ΔPFCmin are the maximum and minimum allowable variations in fuel cell power. ΔIFCmax and ΔIFCmin are the maximum and minimum allowable variations in fuel cell current.

In this study, the ECMS control layer consists of a simple ECMS responsible for solving the objective function and optimizing FCHEV energy flow within its time scale. The equivalence factor optimization layer maintains the battery SoC within a specified range over long periods by adjusting equivalence factor values. This hierarchical structure enhances system adaptability to varying conditions. To obtain the optimal equivalent factor (Opt_EF), we combined the equivalent factor (DQN_EF) calculated using the DQN with the equivalent factor (SoC_EF) calculated using the SoC penalty function. Considering the cyclical characteristics of engineering-vehicle operations, we used the LSTM neural network to predict future power demand.

Specifically, the LSTM model first performs short-term power prediction based on historical load data, providing forward-looking information for upper-layer decision-making. The DQN agent then takes the predicted power, SoC status, and energy consumption feedback as inputs and outputs DQN_EF. Meanwhile, the SoC penalty function generates SoC_EF according to the deviation of the SoC to maintain the stability of the battery’s state of charge. Subsequently, the fuzzy logic module takes DQN_EF and SoC_EF as inputs, applies rule-based reasoning, and outputs Opt_EF, which is then passed to the lower-layer ECMS for power distribution. The energy management architecture proposed in this article is illustrated in Figure 2. The process description is shown in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 H-ECMS |

| 1: Initialize all variables and models NLSTM, QRE, QRT |

| 2: Import LSTM neural network training sample set |

| 3: Training NLSTM |

| 4: From historical environment data, retrieve training tuples Φ(st, a, r, st+1) and store them in the replay buffer R |

| 5: Perform the gradient descent step using QRE(s, a) |

| 6: Set QRT = QRE |

| 7: loop |

| 8: Forecast the demand power for the next five steps using NLSTM and obtain the known Ppred |

| 9: s (current row status from environment) |

| 10: Choose a(ε-greed(s, a)) |

| 11: Take a, reward r and st + 1 (select fuel cell output power through new equivalent factor a) |

| 12: Draw N oversamples (st, a, r, st+1) from R |

| 13: Perform gradient descent step using QRE |

| 14: Set QRT=QRE |

| 15: Based on the SoC penalty function, the SoC_EF at this time is obtained |

| 16: Taking action a, SoC_EF as fuzzy logic input, the output Opt_EF is obtained |

| 17: Use ECMS to output fuel cell output power through Ppred, Opt_EF, etc. |

| 18: And store the historical actual power into the LSTM memory bank |

| 19: if LSTM memory bank > 100 then |

| 20: Train NLSTM and update the model and LSTM memory library |

| 21: end if |

| 22: end loop |

Figure 2.

The proposed hierarchical EMS for FCHEV.

3.2. Equivalence Factor Regulator Based on DQN Reinforcement Learning

The SoC penalty function component is designed for online adaptive adjustment based on the battery’s SoC during real-time operation of the engineering vehicle by using the penalty function of the tangent function. This component plays a crucial role in the equivalence factor. Various methods, such as the S fitting curve, piecewise function processing, and tangent function processing, can be used to select the penalty function. In this study, we employed the tangent function processing method. By using the battery SoC penalty function of the tangent function, the system can quickly respond to SoC changes, effectively control the SoC within a reasonable range, and improve the adaptability of the equivalence factor to working conditions. This design helps balance system stability and adaptability. The effectiveness of the SoC penalty function has been demonstrated and verified in a previous study [45] (Equation (7)):

where sref is the initial equivalence factor reference value, are the battery’s and fuel cell’s average efficiency, respectively, DSoC is the allowed variation range of the battery SoC, and l1 and l2 are adjustment parameters.

By adjusting the values of l1 and l2, the shape of the penalty function can be changed to control its response speed to battery SoC changes. This adjustment can reduce the effect of changes in the equivalence factor reference value on vehicle fuel consumption economy. In this paper, the weighted translation method was used to adjust reference value of the equivalence factor. The adjustment formula is shown in Equation (8):

where k = 1, 2…, sref,k, sref,k+1 is the equivalent factor reference value for k and (k + 1) in the calculation, α is the weight value, and sk+1 is the equivalent factor of (k + 1) in the calculation.

In the DQN algorithm, the load power requirement and SoC are the state variables (s), DQN_EF(k) is control action (a), and the immediate reward (r) is defined by functions such as the current fuel consumption and deviation of current SoC from target SoC.

where SDQN(k) is the state space, A(k) is the action space, R(s, a) represents the reward, SoC(k) represents the previous battery SoC, Pload(k) is the load power requirement, DQN_EF(k) is the equivalent factor calculated based on DQN, α1 and α2 are weight coefficients, rk is the coefficient, IFC is the fuel cell current, mH2 is the current hydrogen consumption, SoC is the battery SoC value, and SoCref is the battery SoC final value.

3.3. Fuzzy Logic-Based Fusion Coefficient Adjustment

For the ECMS algorithm, the selection of the equivalence factor is crucial, as it directly affects the accuracy of power distribution and the stability of the strategy. Prior studies have made progress in this area. For example, ref. [37] proposed a reinforcement learning-based multi-objective ECMS for optimizing power allocation; ref. [46] presented an adaptive ECMS based on DDQN, which uses SoC and periodically predicted driving-cycle information as inputs to correct the EF in a feed-forward manner, while the ECMS is employed to compute engine torque and the drivetrain gear ratio.

However, most existing studies rely on a single method to adjust the EF, which can lead to limited adaptability and insensitivity to complex operating conditions. To address this, we propose an intelligent EF optimization mechanism that integrates DQN-based reinforcement learning, an SoC-based penalty adjustment, and fuzzy logic fusion. This approach leverages the adaptive learning capability of DQN, the physical constraints provided by the SoC penalty function, and the smooth decision-making of fuzzy logic, thereby enhancing algorithmic stability while effectively reducing training time.

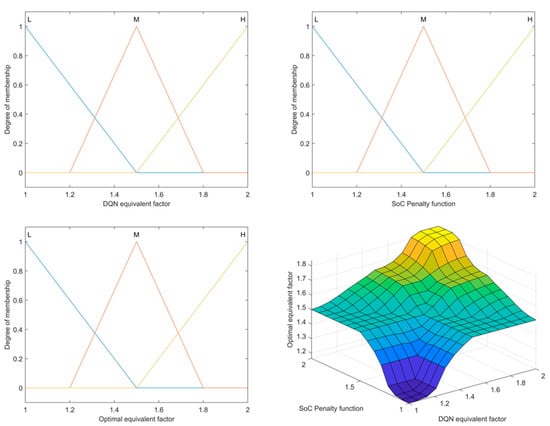

To obtain the optimal equivalent factor (Opt_EF), we combined the equivalence factor calculated using DQN (DQN_EF) with the equivalence factor calculated using the SoC penalty function (SoC_EF). The fuzzy logic method was used to fuse these two inputs and output an optimal equivalence factor for subsequent ECMS calculations. Using the fuzzy logic fusion equivalence factor designed by Mamdani, DQN_EF was selected as the first input to the fuzzy logic controller, and SoC_EF was selected as the second input. After normalization and fuzzy inference, the optimal equivalent factor (Opt_EF) was obtained.

The fuzzy logic fusion device has three states for each of the input variables, DQN_EF and SoC_EF, and three states for the output variable, Opt_EF. The membership functions of these variables and input–output relationship surface generated based fuzzy rules are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Input–output relationship under membership function and fuzzy rules.

3.4. Proof of Optimal Range of Equivalent Factors

When using the ECMS for energy management in hybrid power systems, there are maximum and minimum values for the equivalence factor [47]. The lower limit of the equivalence factor is 1 [47]:

where sopt(t) is optimal equivalent factor.

As the equivalence factor increases, the hybrid power systems increase the fuel cell’s output power. Equation (5) presents the optimization criterion. Theoretically, when the equivalence factor exceeds the maximum value, the fuel cell in the hybrid power system alone provides the power required for operation of the engineering vehicle. However, a hybrid power system relying solely on fuel cells cannot achieve an optimal fuel economy. Therefore, the maximum value of the equivalence factor must exist in the pure battery power supply or fuel cell and battery hybrid power supply mode. This relationship can be described as follows:

where HFC, HB, and HHY, respectively, represent the Hamiltonian functions when the hybrid power system provides energy by only the fuel cell, by only the battery, and when the fuel cell and battery jointly provide power for the engineering vehicle; and uFC, uB, and uHY, respectively, represent the fuel cell’s output power when the hybrid power system is powered only by the fuel cell, powered only by battery, and when the fuel cell and battery jointly provide energy for engineering vehicle. This can be expressed using Equation (12):

where ηFC(uFC) is the fuel cell’s efficiency when only the fuel cell provides the power required by the engineering vehicle. The engineering vehicle’s required power in each mode is defined as Pload, and Equation (12) can be simplified to Equation (13):

where ηB, ηFC, and ηDCFCg, respectively, represent the battery efficiency, the fuel-cell efficiency, and the efficiency of the unidirectional DC–DC converter at the fuel-cell side. From Equations (11)–(13), the upper limit of the optimal equivalence factor is defined as

Therefore, the optimal ECMS should limit the optimal equivalence factor to the upper and lower limits:

The interval of the equivalence factor is between 1 and 1.67. By operating within this range, the lower limit ensures that the ECMS does not assign an excessively small equivalence factor, which would encourage overuse of the battery, while the upper limit prevents the factor from becoming too large, which would lead the controller to rely too much on the fuel cell. In practice, the candidate equivalence factors produced by the DQN estimator and by the SoC-based penalty are fused and then clipped to this interval before entering the ECMS. The next section implements this constrained ECMS and evaluates its effect in a simulation and experiments.

4. Simulation Results and Discussion

The performance of the proposed strategy is validated via simulation. This paper adopts the most common V-type operation method with a short operation cycle time and high operation efficiency. The general working process of the loader can be described as moving forward to the pile of materials—shoveling—moving backward—moving forward to the dump truck—unloading—returning to the original work station. Repeating the above working process is the working condition of the sampling data in this paper. The representative work cycle of the loader outlined in this paper usually lasts about 60 s. The total workload is sampled for 1000 s, including about 15 typical work cycles, and the construction vehicle shows excellent operational repeatability, with highly similar load conditions in each cycle. These work cycles fully reflect the typical working conditions of the construction vehicle. Table 1 shows the basic hardware parameters of the vehicle used in the simulation.

Table 1.

Parameters of FCHEV.

4.1. LSTM Neural Network Prediction Effect

In the field of driving-cycle prediction, different prediction approaches should be selected according to specific application scenarios. Ref. [48] proposed an energy management strategy for fuel cell vehicles based on Pontryagin’s Minimum Principle (PMP), in which a tuna swarm optimization-optimized neural network was employed for driving-cycle recognition to update the co-state variables. Ref. [49] developed a combined prediction approach that integrates a fixed state transition matrix with rolling prediction based on driving states for driving-cycle forecasting. For loaders, however, the working environment is harsh, and the load power varies frequently with strong periodic characteristics. Therefore, this study adopts the LSTM network for driving-cycle prediction. The LSTM model can effectively capture short-term temporal dependencies and nonlinear relationships. It takes the previous 24 time steps of power data as inputs and predicts the subsequent 5 time steps, with a sampling period of 1 s. The model consists of two stacked LSTM layers, each containing 32 hidden units. We also established a storage database to store these predictions. When certain conditions are met by the storage database, the LSTM network is retrained to incorporate the actual power values into the training dataset. This prevents error accumulation and maintains the prediction accuracy.

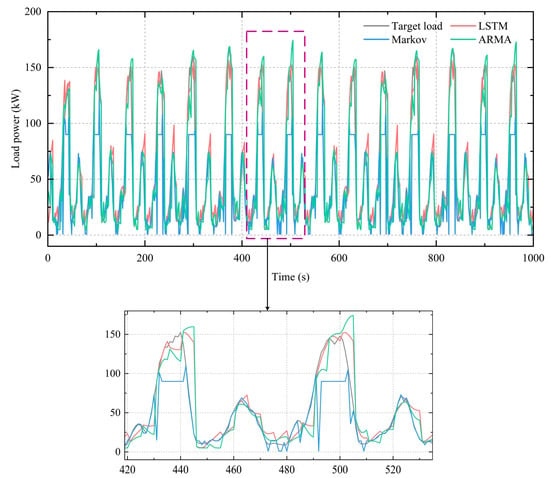

For the normal operation of the energy management framework, real-world operational data are collected in advance to train the proposed model. The dataset consists of 3000 training, 1000 validation, and 1000 testing samples. We compared the LSTM neural network model with a Markov chain prediction model and autoregressive moving average (ARMA) model to assess its prediction performance.

The root mean square error (RMSE) of the LSTM, Markov, and ARMA load power forecasting methods are 18.18, 31.44, and 25.58, respectively. Figure 4 shows the prediction results of the three methods. The statistical parameters of each prediction algorithm are shown in Table 2. It can be seen that the RMSE of the LSTM forecasting method is smaller and can better reflect the change trend of future load power. Consequently, the prediction performance of the LSTM neural network is better than the other two models, which reflects remarkable results of the LSTM neural network in power forecasting and can provide reliable load power demand forecasting for subsequent EMS.

Figure 4.

Load power prediction effects of different prediction methods.

Table 2.

Prediction performance metrics.

4.2. Adaptability of Equivalence Factor Regulator Based on DQN

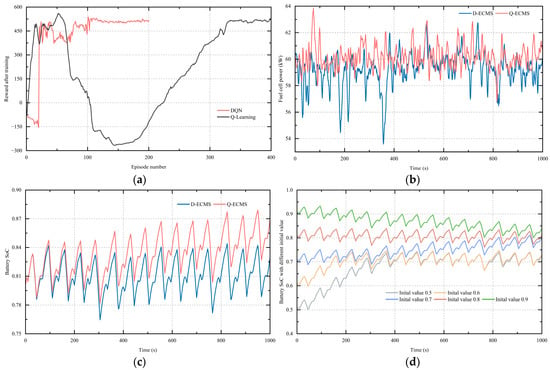

The reward curves for DQN and Q-Learning agents after training are shown in Figure 5a. According to the reward function in Equation (9), after 100 training rounds, the DQN algorithm consistently maintained a high return, with decreasing reward fluctuation over time. Compared with the DQN algorithm, the Q-learning algorithm converges more slowly; however, it also reaches a comparably high reward after about 400 episodes.

Figure 5.

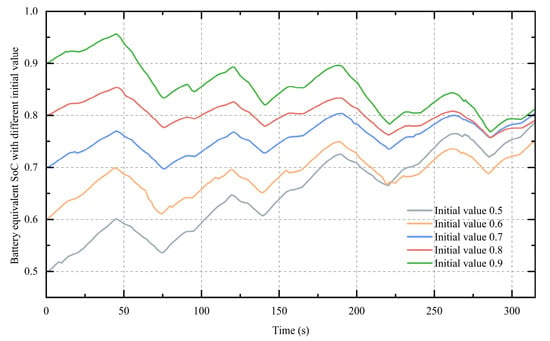

(a) Trained agent reward; (b) fuel cell power under different EMSs; (c) battery SoC under different EMSs; (d) battery SoC under different initial values.

Table 3 compares the equivalent hydrogen consumption of a Q-learning-based ECMS (Q-ECMS) and DQN-based ECMS (D-ECMS). The Q-ECMS’s consumption is 1.80% higher than the D-ECMS’s. Figure 5b shows that under the Q-ECMS, the fuel cell output power ranges from 55.73 kW to 64.40 kW, averaging 60.17 kW. Under the D-ECMS, it ranges from 52.41 kW to 63.13 kW, averaging 59.18 kW. The higher fuel cell power in the Q-ECMS results in greater hydrogen consumption. Figure 5c shows the lithium battery SoC, converging to 0.86 with the Q-ECMS and 0.83 with the D-ECMS. Overall, the DQN algorithm demonstrated a better convergence performance, speed, and efficiency than Q-Learning. The battery SoC is crucial in hybrid systems, affecting energy management. Initial SoC values were set to 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, and 0.9 to analyze the performance under different conditions. Figure 5d shows the SoC trajectory, which remained within an acceptable range and converged to around 0.8, demonstrating the proposed algorithm’s adaptability.

Table 3.

Equivalent hydrogen consumption under different learning algorithms.

4.3. Comparison of EMSs

The adaptive hierarchical ECMS proposed in this paper utilizes the ECMS as its control output. Therefore, we compared it with the theoretically optimal dynamic programming algorithm, the DQN-based ECMS (D-ECMS), the adaptive ECMS (A-ECMS) based on the SoC penalty function, and the ECMS based on constant equivalence factors (ECMS). The dynamic programming algorithm was considered an offline optimization algorithm and served as a benchmark for comparison. The evaluation function of the equivalent consumption minimum principle is shown in Equation (5). By comparing these strategies, we evaluated the performance of H-ECMS in practical applications and demonstrated its advantages under complex working conditions.

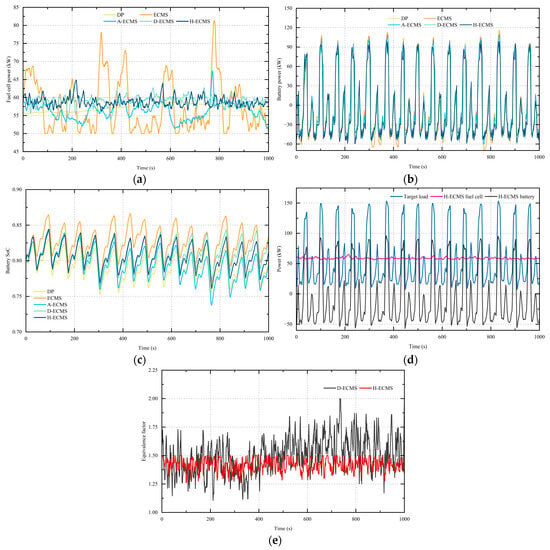

A comparison of fuel cell power under different EMSs is shown in Figure 6a. The dynamic programming algorithm maintained the most balanced fuel cell output power, with an average power of 57.18 kW and a standard deviation of 0.96 kW. In contrast, the ECMS algorithm exhibited the largest power fluctuations, with an average power of 57.43 kW, a standard deviation of 7.15 kW, and a variation range between 50 and 82.29 kW, resulting in significant SoC oscillations of the battery. Although the A-ECMS algorithm demonstrates smoother power variations than the ECMS, its fluctuations are still more pronounced than those of other algorithms. The D-ECMS and H-ECMS algorithms show similar power variation characteristics, with standard deviations of 1.47 kW and 1.54 kW, respectively, which are marginally higher than the outcomes produced by the dynamic programming algorithm. The average fuel cell power of the H-ECMS algorithm is 58.80 kW, which is closer to that of the dynamic programming algorithm. As shown in Figure 6b, in some cases, the battery power of the ECMS and A-ECMS fluctuates more, differing significantly from dynamic programming. The battery power of the H-ECMS is closer to that of dynamic programming. In summary, the H-ECMS is better at maintaining the fuel cell’s high-efficiency operation, enhancing the performance and stability of the hybrid power system and improving fuel utilization.

Figure 6.

Analysis of different EMSs. (a) Fuel cell power under different EMSs; (b) battery power under different EMSs; (c) SoC under different EMSs; (d) fuel cell-lithium battery power follower; (e) optimal equivalent factor values for different EMSs.

The battery SoC under different EMSs is shown in Figure 6c. The DP, ECMS, A-ECMS, D-ECMS, and H-ECMS effectively maintained an SoC around 0.8. The ECMS showed the largest SoC fluctuations, surpassing 0.8. Both the D-ECMS and H-ECMS demonstrated more stable SoC behavior, with trajectories closely approaching 0.8. The H-ECMS maintained an SoC at 0.81, slightly higher than DP’s 0.8, indicating a better performance in maintaining the battery SoC. This article uses the H-ECMS method as an example to add a relationship diagram between the loader demand power, fuel cell output power, and lithium battery output power in order to better understand and observe the power-following effect, as shown in Figure 6d.

In adaptive equivalent consumption minimization, selecting equivalent factors is crucial. We compared equivalence factors from the H-ECMS and D-ECMS. According to Equation (15), the optimal equivalence factor range is based on the average power of the fuel cell, battery, and DC/DC converter, with limits of 1.67 and 1. Figure 6e shows that the H-ECMS maintained an equivalence factor between 1.2 and 1.5, within the optimal range, making it more reasonable and cost-effective in reducing fuel consumption compared to the D-ECMS. This paper calculated the computational complexity of the method. It is noteworthy that the proposed H-ECMS algorithm takes 102.25 s and consumes 1776.1 MB of memory, whereas the LSTM neural network takes relatively less time, only 10.39 s, but consumes much more memory, 1745.8MB.

The final evaluation of equivalent fuel consumption minimization is the hydrogen consumed during the working cycle. Table 4 shows hydrogen consumption for the dynamic programming, ECMS, A-ECMS, D-ECMS, and H-ECMS, including fuel cell and equivalent lithium battery hydrogen consumption. The equivalent hydrogen consumption of the H-ECMS, A-ECMS, D-ECMS, and ECMS is 97.44%, 96.34%, 92.98%, and 91.71% of the dynamic programming benchmark, respectively. Among them, the H-ECMS achieves the closest performance to dynamic programming, indicating the superior fuel economy of the proposed method.

Table 4.

Simulation equivalent hydrogen consumption under different EMSs.

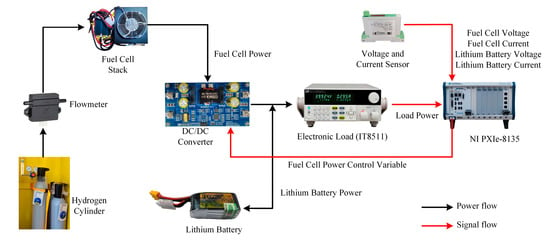

5. Experimental Results and Discussion

The EMS performance was verified by hardware-in-the-loop experiments, comparing diverse EMS algorithms. Each experiment used a PXIe system and LabVIEW instrument with electronic loads simulating construction machinery power requirements. The EMS calculated optimized control variables, delivering fuel cell output power to the unidirectional DC/DC. The control period was 1 s, with a 200 ms sampling period. Table 5 shows the experimental equipment parameters. Figure 7 illustrates the connection layout of each component in the hardware-in-the-loop experimental platform.

Table 5.

Experimental equipment parameters.

Figure 7.

Hardware-in-the-loop experimental platform.

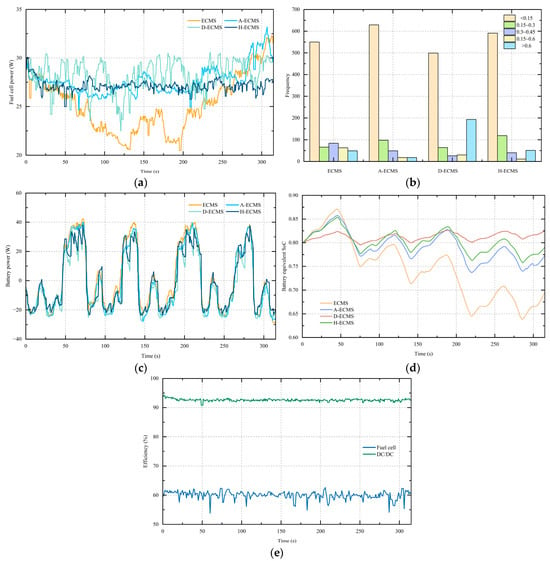

The proposed H-ECMS algorithm was compared with D-ECMS, A-ECMS, and ECMS algorithms, and its control performance was experimentally verified. Due to experimental limitations, we scaled the simulation data 2500 times and used a suitable lithium battery. Since no market lithium battery matched the scaled capacity, the SoCs in the experiment are equivalent SoCs derived from experimental data. Minor prediction errors and equipment performance fluctuations resulted in delays and errors in the outcomes. The experimental results for the four EMSs are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Experimental analysis of different EMSs. (a) Fuel cell power under different EMSs; (b) histogram of the fuel cell power under different EMSs; (c) battery power for different EMSs; (d) battery SoC for different EMSs; (e) real-time efficiency with H-ECMS.

Figure 8a shows the fuel cell power under four EMSs, with the power histogram in Figure 8b. From the figure, it can be observed that the conventional ECMS exhibits the largest fluctuation in fuel cell power, with frequent sharp rises and drops. This indicates that the traditional equivalent factor is not adaptive enough to rapidly changing load conditions, leading to less stable fuel cell operation. In contrast, both the D-ECMS and A-ECMS show smoother power trajectories, demonstrating improved adaptability due to the inclusion of dynamic or adaptive equivalence factor adjustment. However, their fluctuations are still noticeable during transient load variations. The proposed H-ECMS maintains the most stable fuel cell output throughout the entire cycle. The curve remains within a narrow fluctuation band, indicating that the hierarchical optimization and the use of LSTM prediction effectively suppress short-term disturbances. This stability contributes to smoother energy management, reduced transient stress on the fuel cell, and improved overall system efficiency.

Figure 8c presents the lithium battery output power, showing similar trends across all EMSs. Lithium batteries acted as auxiliary storage when the load power changed drastically. Figure 8d shows the SoC curves, where the H-ECMS maintained a final SoC of 0.798 from an initial 0.8, better than the other EMSs. The D-ECMS had a final SoC of 0.82 but larger power fluctuations than the H-ECMS. The A-ECMS and ECMS had final SoCs of 0.765 and 0.70, respectively, and a significant SoC drop over time could affect battery life. Thus, the H-ECMS outperformed the D-ECMS, A-ECMS, and ECMS in overall control effect.

The real-time efficiency of the DC/DC converter and fuel cell used in the experiment is presented in Figure 8e. The DC/DC converter’s efficiency ranged from 90.78% to 94.23%, with an average efficiency of 92.61%. The fuel cell’s efficiency ranged from 53.81% to 62.64%, with an average efficiency of 59.98%. These results indicate that the fuel cell was operating under a high-efficiency range during the experiment. The experimental results confirmed that the efficiency settings of the DC/DC converter and fuel cell in the simulation environment are reasonable.

The equivalent hydrogen consumption under different EMSs is presented in Table 6. The H-ECMS exhibited the lowest hydrogen consumption. Compared to the D-ECMS, A-ECMS, and ECMS, the equivalent hydrogen consumption of the H-ECMS was lower by 3.38%, 9.12%, and 16.39%, respectively. Due to problems in the experimental conditions, such as hydrogen leakage and uneven hydrogen reaction, there were some differences between the experimental and simulation results.

Table 6.

Experimental equivalent hydrogen consumption under different EMSs.

The H-ECMS’s experimental results for diverse initial SoC values (0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9) are presented in Figure 9. Under the initial SoC of 0.6, the minimum termination value was 0.75. For an initial SoC of 0.9, the maximum termination value was 0.81, while other values converged around 0.8. These results demonstrate the H-ECMS’s strong performance and adaptability across different initial SoC values.

Figure 9.

Battery SoC for different initial values.

6. Conclusions

This paper primarily combines DQN, fuzzy logic, and the ECMS to design a novel reinforcement learning-based adaptive H-ECMS. This method has been successfully applied to typical working conditions of a loader. Through simulations and experiments, the proposed energy management framework has been verified to effectively reduce hydrogen consumption. The principal conclusions drawn from this study are as follows:

(1) The LSTM neural network is employed for working condition prediction. Compared with the Markov model and the ARMA model, the simulation results indicate the effectiveness of LSTM prediction model.

(2) Two equivalent factors are obtained using the DQN algorithm and the SoC penalty function. These factors are then fused using a fuzzy logic controller. The optimal equivalent factor derived from fuzzy logic is utilized in the subsequent ECMS algorithm, enhancing the efficiency of the ECMS.

(3) In the simulation environment, compared to the dynamic programming control strategy, the H-ECMS, A-ECMS, D-ECMS, and classic ECMS control strategies achieve lower equivalent hydrogen consumption, reaching 97.44%, 96.34%, 92.98%, and 91.71% of that under the dynamic programming strategy, respectively. Under experimental conditions, the H-ECMS exhibits the lowest hydrogen consumption, achieving equivalent hydrogen savings of 3.38%, 9.1%, and 16.39% in comparison with the D-ECMS, A-ECMS, and ECMS control strategies, respectively. Through simulations and experiments, the pro-posed H-ECMS algorithm has been proven to effectively reduce hydrogen consumption.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.L. (Huiying Liu) and H.X.; methodology, H.L. (Huiying Liu); software, H.L. (Haofa Li); validation, B.H. and Y.L.; formal analysis, H.L. (Huiying Liu); investigation, B.H. and Y.L.; resources, H.L. (Haofa Li); data curation, H.L. (Haofa Li); writing—original draft preparation, H.L. (Huiying Liu) and H.L. (Haofa Li); writing—review and editing, H.L. (Huiying Liu) and H.X.; visualization, B.H.; supervision, H.L. (Huiying Liu) and H.X.; project administration, H.X.; funding acquisition, H.L. (Huiying Liu). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Jilin Provincial Natural Science Foundation, grant number 20250102233JC.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Hai Xu was employed by the company Shenyang Aircraft Airworthiness Certification Center of CAAC. Author Haofa Li was employed by the company Weichai Power Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Sabri, M.F.M.; Danapalasingam, K.A.; Rahmat, M.F. A review on hybrid electric vehicles architecture and energy management strategies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 53, 1433–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Lin, M.; Lin, T.E.; Lan, T.; Liao, X.; Maréchal, F.; Van Herle, J.; Yang, Y.P.; Dong, C.Q.; Wang, L.G. Fuel cell-battery hybrid systems for mobility and off-grid applications: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 135, 110119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balali, Y.; Stegen, S. Review of energy storage systems for vehicles based on technology, environmental impacts, and costs. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 135, 110185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollet, B.G.; Kocha, S.S.; Staffell, I. Current status of automotive fuel cells for sustainable transport. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2019, 16, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Sen, S.; Ajayan, J. A comprehensive techno-economic analysis for hydrogen fuel-cell supported HEVs using predictive control approach. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 83, 396–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hames, Y.; Kaya, K.; Baltacioglu, E.; Turksoy, A. Analysis of the control strategies for fuel saving in the hydrogen fuel cell vehicles. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 10810–10821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Liu, W.; He, H.; Chau, K.T. Deep reinforcement learning-based energy management strategy for fuel cell buses integrating future road information and cabin comfort control. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 321, 119032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motapon, S.N.; Dessaint, L.A.; Al-Haddad, K. A Comparative Study of Energy Management Schemes for a Fuel-Cell Hybrid Emergency Power System of More-Electric Aircraft. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2014, 61, 1320–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Hofmann, H.; Li, J.; Hou, J.; Han, X.; Ouyang, M. Energy management strategies comparison for electric vehicles with hybrid energy storage system. Appl. Energy 2014, 134, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandi, M.; Payman, A.; Martin, J.P.; Pierfederici, S.; Davat, B.; Meibody-Tabar, F. Energy Management of a Fuel Cell/Supercapacitor/Battery Power Source for Electric Vehicular Applications. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2011, 60, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, C.; Liu, Y.; Ding, F.; Chen, Z.; Hao, W. A novel strategy for power sources management in connected plug-in hybrid electric vehicles based on mobile edge computation framework. J. Power Sources 2020, 477, 228650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; He, H.; Xiong, R. Rule based energy management strategy for a series–parallel plug-in hybrid electric bus optimized by dynamic programming. Appl. Energy 2017, 185, 1633–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.G.; Sharkh, S.M.; Walsh, F.C.; Zhang, C.N. Energy and Battery Management of a Plug-In Series Hybrid Electric Vehicle Using Fuzzy Logic. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2011, 60, 3571–3585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, C.M.; Hu, X.; Cao, D.; Velenis, E.; Gao, B.; Wellers, M. Energy Management in Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles: Recent Progress and a Connected Vehicles Perspective. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2017, 66, 4534–4549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Park, J.H. Development of equivalent fuel consumption minimization strategy for hybrid electric vehicles. Int. J. Automot. Technol. 2012, 13, 835–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Song, J. Correctional DP-Based Energy Management Strategy of Plug-In Hybrid Electric Bus for City-Bus Route. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2015, 64, 2792–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Tarsitano, D.; Hu, X.; Cheli, F. Real time energy management strategy for a fast charging electric urban bus powered by hybrid energy storage system. Energy 2016, 112, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Görges, D. Ecological Adaptive Cruise Control and Energy Management Strategy for Hybrid Electric Vehicles Based on Heuristic Dynamic Programming. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2019, 20, 3526–3535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Wei, Q. Policy Iteration Adaptive Dynamic Programming Algorithm for Discrete-Time Nonlinear Systems. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2014, 25, 621–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Yi, F.; Hu, D.; Li, J.; Yang, Q.; Wang, J. Online optimization of energy management strategy for FCV control parameters considering dual power source lifespan decay synergy. Appl. Energy 2023, 348, 121516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, H.; Khajepour, A.; He, H.; Ji, J. Model predictive control power management strategies for HEVs: A review. J. Power Sources 2017, 341, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzi, A.; Torchio, M.; Braatz, R.D.; Raimondo, D.M. Optimal charging of an electric vehicle battery pack: A real-time sensitivity-based model predictive control approach. J. Power Sources 2020, 461, 228133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Mi, C.C.; Xu, J.; Gong, X.; You, C. Energy Management for a Power-Split Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle Based on Dynamic Programming and Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2014, 63, 1567–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, W.; Shang, F.; Zhan, J. Hybrid-Trip-Model-Based Energy Management of a PHEV With Computation-Optimized Dynamic Programming. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2018, 67, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignesh, R.; Ashok, B. Intelligent energy management through neuro-fuzzy based adaptive ECMS approach for an optimal battery utilization in plugin parallel hybrid electric vehicle. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 280, 116792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinoquet, D.; Rousseau, G.; Milhau, Y. Design optimization and optimal control for hybrid vehicles. Optim. Eng. 2011, 12, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liao, R.; Wei, X.; Huang, W. PMP method with a cooperative optimization algorithm considering speed planning and energy management for fuel cell vehicles. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 79, 434–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.Z.; Huang, W.F.; Niu, T.; Liu, Z.T.; Li, G.F.; Cao, D.P. Review of Clustering Technology and Its Application in Coordinating Vehicle Subsystems. Automot. Innov. 2023, 6, 89–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Zhou, H.; Wang, F.; Wang, W.; Lin, X. Longevity-conscious energy management strategy of fuel cell hybrid electric Vehicle Based on deep reinforcement learning. Energy 2022, 238, 121593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Liu, W.; He, H.; Chau, K.T. Health-conscious energy management for fuel cell vehicles: An integrated thermal management strategy for cabin and energy source systems. Energy 2025, 333, 137330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zou, Y.; Liu, D.; Sun, F. Reinforcement Learning of Adaptive Energy Management With Transition Probability for a Hybrid Electric Tracked Vehicle. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2015, 62, 7837–7846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, H.; He, H.; Wei, Z.; Yang, Q.; Igic, P. Battery Optimal Sizing Under a Synergistic Framework With DQN-Based Power Managements for the Fuel Cell Hybrid Powertrain. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2022, 8, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Liu, W.; He, H.; Chau, K.T. Superior energy management for fuel cell vehicles guided by improved DDPG algorithm: Integrating driving intention speed prediction and health-aware control. Appl. Energy 2025, 394, 126195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Zhou, J.; Jia, C.; Yi, F.; Zhang, C. Energy sources durability energy management for fuel cell hybrid electric bus based on deep reinforcement learning considering future terrain information. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 52, 821–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; He, H.; Zhou, J.; Li, J.; Wei, Z.; Li, K.; Li, M. A novel deep reinforcement learning-based predictive energy management for fuel cell buses integrating speed and passenger prediction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 100, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Huang, R.; Meng, X.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, M. A novel hierarchical predictive energy management strategy for plug-in hybrid electric bus combined with deep deterministic policy gradient. J. Energy Storage 2022, 52, 104787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Fu, Z.; Tao, F.; Zhu, L.; Si, P. Data-driven reinforcement-learning-based hierarchical energy management strategy for fuel cell/battery/ultracapacitor hybrid electric vehicles. J. Power Sources 2020, 455, 227964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Li, J. An Adaptive Hierarchical Energy Management Strategy for Hybrid Electric Vehicles Combining Heuristic Domain Knowledge and Data-Driven Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2022, 8, 3275–3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Tao, F.; Fu, Z.; Gao, A.; Jiao, L. Driving-Behavior-Aware Optimal Energy Management Strategy for Multi-Source Fuel Cell Hybrid Electric Vehicles Based on Adaptive Soft Deep-Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 4127–4146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Chu, L.; Hu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, Z. DRL-ECMS: An Adaptive Hierarchical Equivalent Consumption Minimization Strategy Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Aachen, Germany, 4–9 June 2022; pp. 235–240. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, C.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, Y.; Li, W. Reinforcement learning-based energy management strategies of fuel cell hybrid vehicles with multi-objective control. J. Power Sources 2022, 543, 231841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Fu, J.; Yang, H.; Xie, M.; Liu, J. An energy management strategy for plug-in hybrid electric vehicles based on deep learning and improved model predictive control. Energy 2023, 269, 126772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Jia, T.; Hu, X.; Huang, Y.; Deng, Z.; Pu, H. Naturalistic Data-Driven Predictive Energy Management for Plug-In Hybrid Electric Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2021, 7, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Guo, X.; Yang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, D.; Xiang, C. A multi-objective optimization energy management strategy for power split HEV based on velocity prediction. Energy 2022, 238, 121714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Liu, X.; Li, H.; Li, Z. Equivalent consumption minimization strategy based on a variable equivalent factor. In Proceedings of the 2017 Chinese Automation Congress (CAC), Jinan, China, 20–22 October 2017; pp. 4215–4219. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, D.; Xu, H.; Wang, S.; Hu, J.; Chen, L.; Yin, C. Deep reinforcement learning based adaptive energy management for plug-in hybrid electric vehicle with double deep Q-network. Energy 2024, 305, 132402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, A.; Burl, J.B.; Zhou, B. Estimation of the ECMS Equivalent Factor Bounds for Hybrid Electric Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2018, 26, 2198–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, R.; Guo, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Chang, Y. A real-time energy management strategy for fuel cell vehicle based on Pontryagin’s minimum principle. iScience 2024, 27, 109473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, C.; Tao, Y.; Liu, Q.; He, Z.; Liang, J.; Zhou, W.; Wang, L. Grey wolf fuzzy optimal energy management for electric vehicles based on driving condition prediction. J. Energy Storage 2021, 44, 103398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).