Abstract

Understanding luxury tourists required a more comprehensive approach than traditional expenditure-based segmentation, which often overlooked travelers’ financial capacity. This study therefore aimed to develop and validate a new typology of luxury tourists by jointly analyzing income and expenditure patterns using the International Visitor Survey of South Korea. The study addressed the need to capture both tourists’ economic capability and consumption behavior to enhance the precision of market segmentation and support sustainable destination management. Using the Jenks natural breaks classification and logistic regression, four distinct tourist types were identified: economy, spurious, scrooge, and premier, each reflecting unique combinations of income and expenditure. The results revealed that age, nationality, occupation, and trip purpose significantly influenced tourists’ classification. Younger and middle-aged professionals from East Asia were more likely to belong to high-income and high-expenditure groups, whereas Western tourists tended to spend more relative to their income. This income–expenditure typology advanced theoretical understanding of luxury tourism segmentation and provided practical insights for destination marketing organizations. The findings offered new insights for understanding how the alignment between tourists’ financial capacity and spending behavior can redefine strategies for sustainable and inclusive tourism development.

1. Introduction

International tourism significantly contributes to the economic development of host countries by generating foreign exchange earnings, which are crucial for balancing trade deficits and stabilizing national economies. Tourist expenditures on accommodation, food, transportation, and entertainment directly increase a country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). According to the World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC), tourism accounts for over 10% of global GDP in many countries, with some developing economies relying on it for more than 20% of their GDP [1]. Additionally, tourism stimulates employment opportunities, particularly in labor-intensive sectors such as hospitality, retail, and transportation. The sector often provides jobs for low-skilled and semi-skilled workers, reducing unemployment and improving livelihoods in rural and urban areas alike [2].

On the other hand, international travel and tourism plays an important role in stimulating the global demand for luxury products and services and enhancing the luxury phenomenon across regions and cultures [3,4]. The expansion of international travel enables affluent consumers to experience a wide range of luxury products and services such as special accommodations, fine dining, exclusive events, and premium retail opportunities, which in turn strengthens their tendency to consume luxury travel and tourism offerings [5,6]. As destinations compete to attract high-spending visitors, luxury tourism has become an important driver of innovation, destination image, and competitiveness in the hospitality and tourism sectors. According to a report of the 2014 Luxury Goods Worldwide Market Study, the total value of the global luxury market exceeded 850 billion euros in 2014, representing an overall growth rate of 7 percent. Among all luxury sectors, luxury hospitality (9%) and luxury automobiles (10%) were the two fastest-growing categories, suggesting that travel experiences and lifestyle-oriented consumption are key forces behind the expansion of the luxury economy. This pattern of growth shows that luxury tourism is no longer limited to the consumption of tangible goods but increasingly reflects intangible and experiential elements such as comfort, exclusivity, authenticity, and emotional satisfaction that travelers seek across international contexts. Therefore, international tourism not only stimulates economic demand for luxury sectors but also shapes evolving perceptions of luxury as a global cultural and experiential concept.

Several studies have conducted luxury travel and tourism consumption. Some focused on categorizing luxury travel products [7]. For instance, Vigneron and Johnson [8], and Park et al. [9] measured tourists’ subjective perceptions on the attributes of luxury travel products and experiences. These studies provide insights for better understanding luxury markets and identifying the types of luxury products. However, while previous studies have contributed to identifying the nature of luxury products or experiences, they have not fully captured the heterogeneity among luxury tourists from an economic standpoint. Segmenting tourists solely by expenditure provides a behavioral perspective [10,11,12] but neglects tourists’ underlying financial capacity to spend [13]. Consequently, two tourists with similar trip expenditures may represent entirely different market segments, one spending comfortably within means and the other overspending relative to income. To overcome this limitation, this study introduced a dual-dimensional segmentation approach that integrates both income (economic capability) and expenditure (actual consumption behavior).

The purpose of this study was to develop a new typology of international luxury tourists by jointly analyzing their income and expenditure patterns. Using a rigorous methodological approach, the study identified distinctive tourist segments and examined key demographic and behavioral determinants that distinguished affluent travelers from other market groups. This study offers a novel contribution by integrating both income and expenditure dimensions to classify luxury tourists. The findings provide actionable insights for destination marketing organizations and luxury service providers to better target high-value segments, enhance market efficiency, and strengthen sustainable luxury tourism development worldwide.

2. Literature Review

To provide a comprehensive understanding of prior research, the following review examines existing studies on luxury in hospitality and tourism, summarizes market segmentation research based on tourist expenditure, and introduces a conceptual framework that defines and classifies luxury tourists by considering both income and expenditure.

2.1. Luxury Studies in Hospitality and Tourism

Luxury has evolved from a symbol of material exclusivity to a multidimensional and experiential concept in hospitality and tourism. Earlier studies viewed luxury tourism as a rapidly growing niche market characterized by exclusivity, quality, and symbolic consumption [9]. Later research expanded this understanding by examining luxury not only through tangible products but also through experiences, identity, and sustainability. Japutra et al. [14] conducted a systematic review of sixty-three scholarly articles on luxury tourism and identified three principal dimensions of luxury consumption: functional, symbolic, and experiential. Their review revealed that while functional and symbolic attributes such as superior service quality, uniqueness, and social recognition remain dominant, experiential elements including authenticity, hedonism, and emotional engagement have gained importance. The study also emphasized that luxury tourism consumption is culturally sensitive, showing clear distinctions between Western and Asian markets, and that the existing body of research remains fragmented without a comprehensive conceptual framework.

Thirumaran et al. [15] contributed to this discussion by exploring how social media shapes perceptions and communications of luxury in tourism. The study showed that digital platforms have become essential in constructing and sharing experiences of luxury. Through visual storytelling and emotional appeal, social media enables travelers to co-create meanings of luxury while allowing businesses to project exclusivity and sophistication. Platforms such as Instagram and TripAdvisor have become critical spaces for marketing and consumer engagement, influencing how travelers perceive prestige, sustainability, and experiential value. This research also observed that the luxury tourism sector increasingly incorporates sustainable practices, reflecting a shift from conspicuous to responsible consumption.

Earlier theoretical studies further explain the evolution of luxury behavior. Correia et al. [16] examined conspicuous consumption among elites and identified social status, conformity, and pleasure as the main motivational factors. The findings demonstrated that luxury travel choices serve as expressions of social identity and distinction, with high-status individuals favoring more subtle forms of display to communicate refinement. Similarly, Park et al. [9] identified several categories of luxury tourism such as shopping, cruises, and exclusive resorts, showing that luxury tourists are motivated by authenticity, self-fulfillment, and social prestige rather than material possession alone. The findings confirmed that personal service, privacy, and wellness represent the highest forms of contemporary luxury experience. Petrick and Durko [17] advanced the segmentation of luxury tourists by identifying distinct motivational groups among cruise travelers. The cluster analysis revealed five primary types (i.e., Relaxers, Socializers, Cultured, Unmotivated, and Highly Motivated) each displaying different patterns of behavior and expectation. Although comfort and quality were central to all segments, motivations varied across relaxation, social interaction, and cultural enrichment, suggesting that luxury tourists are a heterogeneous market requiring differentiated marketing strategies. Recent studies in hospitality marketing have deepened this perspective by investigating specific luxury sectors. Huh et al. [18] segmented spa guests in luxury hotels and resorts according to their motivations, identifying three clusters: pleasure pursuers, healing pursuers, and relaxation pursuers. Pleasure pursuers were motivated by social and entertainment benefits, healing pursuers sought spiritual and emotional restoration, and relaxation pursuers aimed to escape daily stress. The study revealed that luxury spa services are not only profit centers but also essential components of the overall luxury experience, enhancing guests’ psychological well-being and brand loyalty.

In sum, recent studies suggest that luxury tourism has progressed beyond the traditional focus on exclusivity, price, and comfort. The contemporary understanding of luxury encompasses sustainability, cultural context, digital engagement, and experiential authenticity. This evolution represents a transition from traditional luxury based on material prestige to new luxury characterized by personalization, meaningful experience, and social consciousness. These developments provide a robust theoretical foundation for examining income and expenditure as core determinants in the segmentation of luxury tourists.

2.2. Tourist Market Segmentation in Tourism

In general, tourism market segmentation research has traditionally employed two main approaches. The a priori approach classifies markets based on predetermined criteria, most commonly tourists’ income or expenditure levels [11,13,19], to establish economically meaningful segments. In contrast, the posteriori approach, also referred to as a data driven approach, uses statistical techniques such as factor, cluster, or discriminant analysis to identify distinct groups derived from tourists’ motivational or psychological characteristics [18,20,21]. This study adopted the a priori segmentation method, as it provides a direct and practical framework for understanding and targeting diverse tourist groups. This method is particularly advantageous for identifying high value segments and developing efficient marketing strategies, serving as a valuable foundation for both academic inquiry and managerial application in tourism markets.

Within the a priori segmentation framework, expenditure-based segmentation has been one of the most prevalent methods used to classify tourists. It provides a measurable and actionable means of distinguishing market segments, as expenditure directly reflects tourists’ purchasing power and consumption behavior. Market segmentation techniques must be measurable, accessible, substantial, and actionable, and expenditure based segmentation meets all these criteria, aligning with the conceptual foundation proposed by Kotler et al. [22]. Over time, tourism segmentation research has evolved methodologically. Early studies (e.g., [10,12,23]) often relied on frequency distribution techniques, whereas later research (e.g., [18,19,24,25,26,27]) adopted more advanced statistical methods such as AID, CHAID, factor, and cluster analysis.

Pizam and Reichel [28] grouped tourists as big or small spenders based on total vacation expenditure and identified significant differences in socio demographic characteristics between the two groups. Spotts and Mahoney [12] divided tourists into heavy, moderate, and light spenders using frequency distribution and reported meaningful variations in spending behavior. Mok and Iverson [10] similarly segmented tourists into three expenditure groups and found that heavy spenders differed from others in age, party size, trip purpose, and travel patterns. Extending their work, Dixon et al. [23] applied this method to sport tourists and revealed significant variations in spending behavior, trip characteristics, and preferences among low, medium, and high expenditure groups.

Legohérel [27] introduced more advanced techniques, applying the Automatic Interaction Detector and canonical analysis for tourism market segmentation based on actual and intended spending. Díaz-Pérez et al. [19] used decision tree methodology and the CHAID procedure to classify tourists by expenditure, showing that nationality and occupation were key determinants. Legohérel and Wong [25] further demonstrated that daily expenditure was strongly related to annual household income and emphasized the identification of high spending tourists. Similarly, Lima et al. [26] employed cluster analysis to classify tourists into four expenditure segments (i.e., light, medium, lodging and activities oriented, and food and shopping oriented) and found significant differences in socio demographic traits and travel behaviors across these segments.

In sum, expenditure-based segmentation has progressed from simple descriptive to statistically sophisticated approaches, revealing that tourists’ spending behaviors vary by demographic and behavioral characteristics. However, most studies have examined expenditure in isolation without considering income. To address this gap, this study integrates both income and expenditure within an a priori framework to develop a typology of luxury tourists and identify determinants of their market differences.

2.3. Typology and Conceptualization of Luxury Tourists

Tourism researchers have traditionally segmented tourists according to their expenditure patterns [14,23,26]. Although expenditure provides a measurable and convenient variable for market segmentation, it alone may not fully explain tourists’ consumption behavior in the luxury context. As noted by Dixon et al. [23], the level of tourist expenditure is influenced by discretionary income, which represents the amount of money available for leisure and non-essential activities. Therefore, understanding luxury tourists requires the consideration of both income and expenditure together, since income indicates the potential for luxury consumption, while expenditure reflects the actual spending decision made during travel.

Considering both variables together offers a more logical and realistic framework for classifying luxury tourists. The inclusion of income captures a tourist’s financial capacity, while expenditure represents how such capacity is exercised in actual travel behavior. This dual perspective allows researchers to interpret whether tourists’ luxury consumption aligns with their financial means or represents aspirational behavior that exceeds their economic boundaries. Consequently, the relationship between income and expenditure becomes a key element in explaining tourists’ approach to luxury travel and in developing meaningful typologies for research and practice.

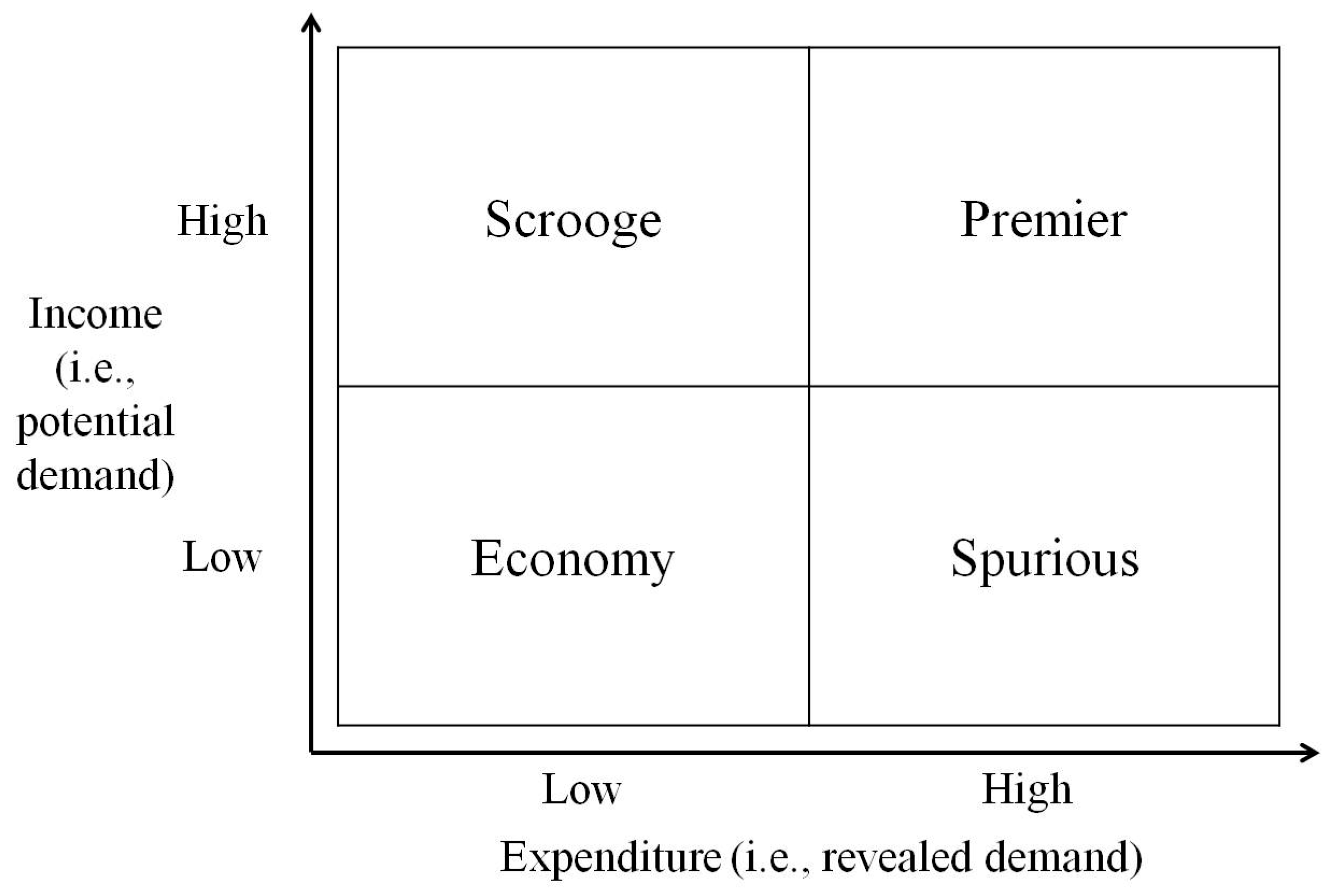

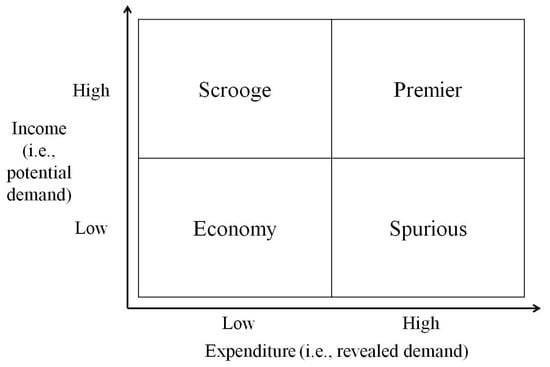

Based on this theoretical foundation, the study introduces a conceptual model that categorizes luxury tourists by considering income on the Y-axis and trip expenditure on the X-axis. As displayed in Figure 1, four distinct types emerge from the composition between income and expenditure. The “economy” type refers to tourists with low income and low trip expenditure, representing modest consumers with limited financial ability. The “premier” type includes tourists with high income and high expenditure, reflecting genuine luxury travelers whose consumption is consistent with their financial status. The “scrooge” type represents those who have high income but spend relatively little, suggesting careful or restrained consumption behavior. The “spurious” type includes tourists who have low income but spend heavily on travel, indicating aspirational or status-seeking consumption patterns.

Figure 1.

A conceptual model for luxury tourist segments.

This classification model provides a comprehensive way to interpret the diversity of luxury tourists and their behavioral tendencies. By examining both economic capacity and actual expenditure, the typology distinguishes between authentic and aspirational luxury travelers, thereby improving the understanding of how luxury travel decisions are shaped. Such a conceptualization enables destination marketing organizations and tourism businesses to develop more accurate market strategies and product offerings based on the alignment between tourists’ income levels and their spending behavior. Ultimately, the integration of income and expenditure dimensions advances the theoretical understanding of luxury tourism segmentation and establishes a foundation for empirical analysis of the luxury tourist market.

3. Method

3.1. Study Participants

To achieve the purpose of the study, this study used International Visitor Survey (IVS) data conducted by Korea Culture and Tourism Institute (KCTI). This survey plays a critical role in capturing a wide range of information related to foreign visitors, helping the tourism economy of South Korea to better manage and promote its tourism industry. The IVS has collected international visitors’ socio-demographics, behaviors, motivations, satisfaction levels, and spending patterns of international tourists visiting the country since 2007 [29]. According to the International Visitor Survey, trained survey interviewers approach international visitors in departure waiting lounges at Incheon, Gimpo, Gimhae, Jeju, Daegu, and Yangyang international airports, and Busan and Incheon international ports. Participants are asked to respond about whether they stayed over a night and are over 15 years old. Over 1000 questionnaires are collected per month and an approximately total of 16,000 questionnaires are collected per year.

3.2. Study Data

While the international visitor survey data have been publicly available at Tourism Knowledge Information System from 2007 to 2024 [29], only the 2009 dataset contained both tourists’ household income and trip expenditure information. These two variables were essential for operationally defining the types of luxury tourists and empirically testing the proposed typology based on the composition of income and expenditure. Therefore, the 2009 dataset was selected as the only feasible and valid data source for this study. Additionally, before conducting the analyses, the reported amounts of income and expenditures were converted to U.S. dollars by applying the official exchange rates corresponding to the month and year of data collection.

The 2009 IVS dataset originally included 11,815 valid responses from international visitors to South Korea. However, because the present study required both household income and trip expenditure data, only 4411 cases contained complete information for these two key variables. After further screening for missing values and extreme outliers, the final analytical sample consisted of 4382 respondents. This refined dataset ensured data quality and statistical validity for the Jenks classification and subsequent logistic regression analyses.

3.3. Study Variables and Instrument

The definition and classification of all variables were based on the standardized categories used by the International Visitor Survey (IVS) to ensure consistency and minimize subjectivity. For example, “travel purpose” was coded according to official IVS options (business/professional vs. tourism/recreation), and “accommodation type” followed the IVS classification (hotel vs. others). These objective and replicable coding procedures improve the accuracy of classification and reliability of research results.

For the dependent variable, two sets of data were used. Expenditure data were obtained from the question: “The following questions refer to traveling expenses (total expenses & specific expenses). Please write the total amount of your travel expenses during your visit to Korea and choose the currency unit.” Income data were obtained from the question: “What is your household’s income? Please include the income of all family members. Please select the following type of currency, and write your annual income below.”

To classify the luxury tourist types, the Jenks natural breaks classification method [30] was employed to determine statistically optimal cut-off points in the distribution of tourists’ household income and trip expenditure. This method minimizes variance within each class and maximizes variance between classes, producing objective thresholds rather than arbitrary or researcher-defined ranges. The analysis procedure first arranged all income and expenditure data in ascending order and converted them into deciles. Then, the Jenks optimization algorithm identified breakpoints that maximized the Goodness of Variance Fit (GVF) statistic, ensuring the most stable and interpretable classification. The resulting typology included four groups, economy, premier, scrooge, and spurious, based on combinations of income and expenditure levels. The dependent variable, therefore, represented tourists’ type within this income–expenditure framework.

For the independent variables, the study included tourists’ demographic, behavioral, and post-trip evaluation characteristics, consistent with prior segmentation and expenditure-based research (e.g., [10,23,25]). Demographic variables comprised gender, education, age, occupation, and nationality. Behavioral variables included trip purpose, accommodation type, number of trips in the past three years, number of nights stayed, and number of travel companions. Post-trip evaluation variables included intention to revisit, level of satisfaction, and intention to recommend.

Demographic variables were categorically measured. Gender was recorded as “Male” or “Female.” Education was categorized as “Elementary school to High school,” “Graduate,” “Over postgraduate (MBA, Ph.D.),” or “Others,” and reclassified into “High school or less” and “Above university degree.” Age was recorded as “Year of birth” and categorized into “15–30 years,” “31–50 years,” and “Over 51 years.” Occupation categories included “Government or military,” “Business executive or manager,” “Clerical worker or technician/engineer,” “Sales or service worker,” “Professional (professor, doctor, lawyer, etc.),” “Factory worker/laborer,” “Self-employed,” “Student,” “Homemaker,” “Retired,” “Unemployed,” and “Other.” These were recoded as “Professionals/Executives,” “Officer/Production/Service,” “Self-employed,” and “Others (Retired, Homemaker, Student, etc.).” Nationality was recategorized into “China/Japan,” “Major Asian countries,” “Europe and North America,” and “Others (Middle East, Africa, etc.).”

Behavioral variables were measured as follows. Trip purpose was based on the question: “What was the main purpose of this visit? Please choose one.” Respondents chose among six options, which were reclassified into “Business/Professional” and “Tourism/Recreation.” Accommodation type was measured by the question: “What is the main type of accommodation you used while in Korea?” and reclassified into “Hotel” and “Others.” The number of trips in the past three years, number of nights stayed, and number of traveling companions were continuous variables measured by: “Including this visit, how many times have you visited Korea in the last three years?”, “How many nights did you spend on this trip to Korea?”, and “The number of people in your group excluding you,” respectively.

Post-trip evaluations were measured on a five-point Likert scale. Intention to revisit was assessed by the question: “Will you visit Korea again for travel within the next three years?” (1 = very likely, 5 = very unlikely). Level of satisfaction and intention to recommend were measured by “Rate your overall satisfaction of this trip to Korea” and “Will you recommend Korea as a tourist destination to other people?,” respectively. Responses were reverse-coded so that higher scores indicated stronger positive evaluations.

The inclusion of these independent variables was guided by theoretical and empirical relevance identified in prior studies, which consistently show that tourists’ demographic, behavioral, and evaluative characteristics are strong predictors of expenditure behavior and market segmentation. This variable selection process was designed to enhance the accuracy and explanatory power of the logistic regression model while ensuring conceptual consistency with established tourism segmentation research.

3.4. Jenks Natural Breaks Classification Method

The Jenks natural breaks classification method (also known as the Jenks optimization method) was employed to determine statistically optimal cutoff points for classifying tourists based on their household income and trip expenditure levels. This method was chosen because it objectively identifies natural groupings in data by minimizing variance within each class and maximizing variance between classes [30]. Unlike arbitrary methods that divide data into equal intervals or subjective groupings (e.g., low, middle, high), the Jenks method provides data-driven thresholds that improve the validity and reproducibility of classification outcomes.

The algorithm operates by evaluating the Goodness of Variance Fit (GVF), expressed as:

where SDAM represents the squared deviations from the array mean, and SDCM represents the squared deviations from the class means. A higher GVF indicates that the classification successfully minimizes within-group variance and maximizes between-group differences, resulting in a more accurate representation of the data structure.

In this study, tourists’ household incomes and total trip expenditures were first arranged in ascending order and converted into deciles. A decile represents any of the nine values that divide the ordered data into ten equal parts, with each segment corresponding to one-tenth of the sample or population [31]. The Jenks optimization process was applied to identify the decile boundaries that achieved the highest GVF value, thereby establishing the most stable and meaningful cutoff points for segmenting the luxury tourist market. These verified breakpoints were subsequently used to classify tourists into four types, economy, premier, scrooge, and spurious, based on the composition between their income and expenditure levels.

3.5. Logistic Regression Model

Following the classification of luxury tourist types using the Jenks natural breaks method, a multinomial logistic regression model was applied to examine the factors that distinguish each group. Logistic regression is suitable for predicting the probability of outcomes with categorical dependent variables and estimating the influence of multiple independent variables simultaneously. Because the dependent variable in this study consisted of four nominal categories (economy, premier, spurious, and scrooge) the multinomial logistic model was considered the most appropriate analytical technique. This approach allows for simultaneous estimation of multiple predictors, providing a multivariate analytical framework to identify how demographic, behavioral, and attitudinal variables collectively influence the probability of belonging to each luxury tourist group.

A multinomial logistic regression model compares each non-reference category of the dependent variable against a chosen baseline category [32]. In this study, economy tourists were designated as the baseline, and the model estimated the likelihood that a tourist would belong to one of the three other categories (premier, spurious, or scrooge) relative to the economy group. The model can be expressed as follows:

where J represents economy tourists as a baseline category, j refers to each response category (premier, spurious, and scrooge). denotes the regression coefficients for category j and variable k, and represents independent variables.

To facilitate interpretation, the odds ratio (Exp(β)) was computed for each independent variable. The odds ratio indicates the proportional change in the likelihood of belonging to a specific tourist type for a one-unit increase in a predictor variable. The percentage change in odds can be expressed as:

∆% = 100 (exp (b) − 1)

The model enabled the identification of significant determinants that differentiated between types of luxury tourists, revealing how demographic, behavioral, and post-trip evaluation factors influenced the probability of being classified as premier, spurious, or scrooge compared to the economy group. All analyses, including descriptive statistics and logistic regression estimation, were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 28.0.

4. Results

4.1. Segmenting the Luxury Tourist Market

Luxury tourists were classified into four categories: economy, premier, spurious, and scrooge, based on the relationship between their income levels and travel expenditures, as described in the literature review. To empirically validate this classification, the Jenks natural breaks optimization method [30] was applied. This method identifies natural groupings within a dataset by minimizing the variance within each class while maximizing the variance between different classes, providing an objective statistical basis for segmentation.

Respondents’ household incomes and trip expenditures were arranged in descending order and divided into ten equal parts called deciles to identify meaningful cutoff points. The average annual household income and the average trip expenditure were 104,301 dollars and 1256 dollars, respectively. As shown in Table 1, nearly half of the respondents were located in the tenth and ninth deciles for both income and expenditure. This indicates that these two deciles effectively distinguished the upper and lower ranges of both variables. Therefore, the ninth decile was selected as the cutoff point for income and expenditure since it represented the best point for reducing variation within each group and increasing variation between the groups.

Table 1.

A result of Jenks Optimization Method applied to income and trip expenditure (N = 4382).

Based on these cutoff points, four distinct tourist groups were identified. The economy group included tourists whose income was 197,253 dollars or less and whose trip expenditure was 2140 dollars or less. The spurious group included those whose income was 197,253 dollars or less but whose trip expenditure was 2140 dollars or more. The scrooge group included those whose income was 197,253 dollars or more but whose trip expenditure was 2140 dollars or less. The premier group included those whose income and trip expenditure were both 197,253 dollars or more and 2140 dollars or more, respectively.

These classifications were consistent with the conceptual model proposed earlier, confirming that the Jenks optimization method effectively separated luxury tourist types according to their levels of income and expenditure, as presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Identification of luxury tourist segments.

4.2. Profiles of Luxury Tourist Segments

Following the classification of tourists into four distinct categories based on income and expenditure levels, further analysis was conducted to explore the key characteristics of each group. The results presented in Table 3 show that while some general similarities existed across the groups, several demographic and behavioral differences distinguished one segment from another.

Table 3.

Profiles of luxury tourist segments.

Overall, the economy, spurious, scrooge, and premier tourists shared comparable demographic traits. Most respondents were male, held a university degree or higher, and were between 31 and 50 years old. In addition, hotel accommodation was the most common choice among all four segments, indicating that hotel stays were preferred regardless of spending capacity or income level.

Notable distinctions appeared in occupation, nationality, and trip purpose. More than half of all respondents in each group were professionals or executives. However, the premier group included a relatively higher share of self-employed individuals, suggesting a strong presence of entrepreneurial travelers among those with higher income and expenditure levels. Regarding nationality, the economy and spurious tourists were mainly from Europe and North America, whereas the scrooge group was dominated by visitors from major Asian countries, and the premier group consisted largely of tourists from China and Japan. These differences suggest that regional proximity and economic background influence both travel motivation and spending behavior.

Variations were also observed in travel purpose and post-travel evaluation. The economy and scrooge tourists traveled primarily for business or professional reasons, while the spurious and premier groups traveled mostly for leisure and recreation. The spurious tourists stayed the longest, averaging about twelve nights, while the scrooge tourists had the shortest stays. The premier group showed the strongest post-trip evaluations, including the highest intentions to revisit and recommend the destination, which reflects their overall satisfaction with the travel experience.

In summary, although the four groups shared broad demographic similarities, they differed meaningfully in nationality, purpose of travel, and satisfaction levels. These distinctions provide valuable insight into the behavioral and motivational diversity that exists within the international luxury tourism market.

4.3. Determinants of Luxury Tourist Segments

Building upon the classification and descriptive profiles of the luxury tourist groups, further analysis was conducted to identify the key factors that distinguish one type from another. A series of binary logistic regression analyses was performed to compare each luxury segment (the spurious, the scrooge, and the premier) against the economy group, which served as the baseline category. This approach allowed examination of the demographic, behavioral, and attitudinal variables that significantly influenced tourists’ likelihood of belonging to each luxury category.

The overall model demonstrated a good fit to the data, as indicated by the Pearson Chi-square statistic (χ2 = 6151, df = 6039, Sig. = 0.153). The likelihood ratio tests confirmed that the full model significantly improved the prediction of luxury tourist types compared with the intercept-only model (χ2 = 351.08, df = 54, Sig. = 0.000). These results validated the appropriateness of the regression model for identifying significant determinants across the four tourist groups (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Determinants of Luxury Tourist Segments.

For the spurious segment compared with the economy group, several factors were found to be statistically significant. Tourists under 29 years old and those aged between 31 and 50 years were more likely to belong to this group than tourists aged above 51 years. The likelihood of being spurious also increased among tourists who traveled for leisure or recreation, stayed in hotels, and had longer stays. However, tourists from Europe and North America were less likely to belong to this segment. These results suggest that younger tourists with strong leisure motivations and longer stays tend to spend beyond their income levels.

For the scrooge segment, significant predictors included education, age, occupation, nationality, and travel frequency. Tourists with a university degree or higher, those under 29 years of age, and those working as professionals or executives were more likely to be identified as scrooge tourists. Nationality was a strong factor, with tourists from China, Japan, and other Asian countries showing higher odds of being in this group. In contrast, a higher number of past visits and longer stays were associated with a lower likelihood of being classified as scrooge tourists. This pattern implies that highly educated and professionally active visitors from nearby Asian countries tend to spend less despite having higher income levels, possibly due to shorter travel distances and greater familiarity with the destination.

For the premier segment, significant determinants included age, occupation, nationality, trip purpose, accommodation type, and intention to revisit. Tourists under 29 years old and those aged 31 to 50 years were more likely to belong to this group compared with older tourists. The probability of being a premier tourist was also higher among professionals, executives, and self-employed individuals. Visitors from China and Japan, those traveling for leisure or recreation, and those staying in hotels were more likely to be classified as premier tourists. Moreover, a stronger intention to revisit was positively associated with belonging to this group, indicating that highly satisfied and loyal visitors tend to represent genuine luxury tourists. These findings demonstrate that the differences among the four types are not merely descriptive but statistically derived through multivariate modeling.

In summary, the logistic regression analysis revealed that age, occupation, nationality, and trip purpose were the most influential predictors of luxury tourist types. Younger and middle-aged professionals, particularly from East Asia, were more likely to be high-income and high-expenditure travelers. These findings underscore the importance of demographic and motivational variables in shaping luxury travel behavior and provide valuable insights for market segmentation and targeted destination marketing strategies.

5. Discussion

This study contributes to the sustainable tourism literature by proposing a new perspective on luxury tourist segmentation that considers both tourists’ income and expenditure simultaneously. By employing the Jenks natural breaks classification and logistic regression analyses, the study identified four distinct categories of tourists (economy, spurious, scrooge, and premier) each representing a unique balance between financial capacity and spending behavior. These findings provide a richer understanding of how economic characteristics influence consumption behavior in luxury tourism and demonstrate how this relationship can inform sustainable destination management and marketing practices.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

From a theoretical perspective, this study extends the existing tourism market segmentation theory by introducing an income–expenditure typology that combines economic and behavioral segmentation. Previous studies have primarily relied on expenditure-based segmentation, often neglecting the role of financial capacity that underlies spending decisions. The study addresses this limitation by conceptualizing luxury tourist types as a function of both income and expenditure, thereby offering a more comprehensive and operational framework for luxury tourism research. This approach advances segmentation theory by showing that income–expenditure alignment captures deeper behavioral distinctions that single-variable methods overlook.

The results revealed that age and nationality are significant predictors of the types of luxury tourists. Younger tourists under 29 years old tended to belong to the spurious and scrooge groups, which suggests that they may either aspire to experience luxury beyond their financial means or display constrained spending patterns due to limited income. In contrast, tourists aged between 31 and 50 years were more likely to be classified as premier tourists, representing mature consumers with established income and higher discretionary spending power. These findings align with life cycle and behavioral economics theories, which posit that consumption preferences evolve alongside an individual’s financial stability and life stage.

Nationality also emerged as an important determinant in explaining the segmentation. Tourists from Europe and North America were more likely to be categorized as spurious, indicating that long-haul travel and once-in-a-lifetime experiences may drive higher expenditures relative to income. Conversely, tourists from China and Japan were more often classified as scrooge or premier types, reflecting both their geographical proximity to South Korea and differing economic contexts. These findings empirically support distance-decay theory and contribute to cross-cultural frameworks that explain variations in luxury consumption behavior across global markets.

Behavioral characteristics such as length of stay and revisit intention also contributed significantly to differentiating tourist types. Longer stays were associated with the spurious type, whereas higher revisit intention predicted the premier type. This suggests that sustainable tourism is not only driven by the number of arrivals but also by the development of high-value, repeat visitors who generate consistent economic and cultural benefits for destinations. The linkage between revisit intention and the premier type reinforces the importance of relationship marketing and visitor satisfaction for achieving sustainable tourism growth. Consequently, this study contributes to the theoretical integration of economic segmentation and sustainable consumption behavior within the context of luxury tourism.

In sum, the use of logistic regression moves beyond descriptive segmentation by exploring the underlying causal associations between economic capacity, behavioral patterns, and demographic factors. The findings indicate that the alignment of income and expenditure interacts with age, nationality, and motivation, revealing deeper structural relationships among luxury tourist segments.

5.2. Managerial and Sustainable Implications

The logistic regression results revealed that age, occupation, nationality, and trip purpose were significant predictors of luxury tourist types, indicating meaningful behavioral and psychological distinctions among them. Younger tourists under 29 years old were more likely to belong to the spurious and scrooge categories, while those aged 31–50 years were associated with the premier group. This pattern suggests that younger tourists may exhibit more exploratory and aspirational consumption behaviors, whereas middle-aged travelers display more stable financial capability and confidence in luxury consumption, consistent with life-cycle consumption theories [16].

Nationality also reflected diverse cultural and decision-making patterns. Tourists from China and Japan were more likely to be categorized as premier or scrooge, suggesting more experience-based and pragmatic consumption behaviors shaped by proximity and familiarity with the destination. In contrast, European and North American tourists, who were more likely to belong to the spurious category, tended to spend more on once-in-a-lifetime travel experiences, echoing findings from Park et al. [9] and Petrick and Durko [17] that Western luxury tourists emphasize emotional value and experiential authenticity in their decisions.

The influence of trip purpose and accommodation type further demonstrates that behavioral intentions differ by market segment. Leisure-oriented travelers, particularly those staying in hotels, were strongly associated with the premier and spurious types, indicating a desire for comfort, prestige, and experiential quality—core psychological motivators in luxury tourism consumption [4,8]. Conversely, business-oriented travelers and those choosing non-hotel accommodations were more likely to fall within the economy or scrooge groups, reflecting more functional and efficiency-driven decision patterns. These results collectively support that consumption behavior and decision-making in luxury tourism are influenced by both economic capability and experiential motivations, confirming that tourists’ expenditure behavior aligns with their financial and psychological profiles.

Based on these findings, destinations and enterprises can refine marketing strategies grounded in observed behavior. For example, the premier group (high income, high expenditure, strong revisit intention) should be targeted with loyalty-based relationship marketing and culturally authentic experiences to sustain long-term engagement. The spurious group can be approached through value-added packages and emotional storytelling emphasizing symbolic prestige. The scrooge group, characterized by high income but restrained expenditure, may respond better to transparent pricing and efficient service quality assurance. Finally, the economy group can be gradually cultivated through affordable entry-level luxury offerings that encourage repeat visitation.

These empirically supported strategies align with prior studies on luxury marketing [9,15] and sustainable destination management [14], providing practical guidance for enterprises to match marketing approaches with distinct behavioral profiles.

6. Conclusions

This study developed and validated a novel typology of luxury tourists by integrating income and expenditure data into a single segmentation framework. The identification of four tourist types (economy, spurious, scrooge, and premier) provides new insights into how financial capacity interacts with spending behavior to shape tourism demand. Through this framework, the study contributes theoretically by offering an empirically grounded and economically meaningful approach to luxury market segmentation.

The results demonstrate that distinct behavioral and decision-making traits correspond to each luxury tourist type. Age, nationality, and trip purpose collectively explain how individuals approach luxury consumption—whether as aspirational experiences, habitual preferences, or value-conscious choices. These empirically supported patterns allow destination managers to apply evidence-based marketing segmentation. For instance, premier tourists’ high revisit intention reflects brand loyalty potential, while spurious tourists’ long stays but lower incomes point to aspirational consumption that can be nurtured through accessible luxury programs. Such targeted approaches provide actionable guidance for policy makers and enterprises aiming to enhance competitiveness and sustainability.

The practical implications of this typology are equally significant. By understanding the alignment between tourists’ income and expenditure, destination managers and luxury service providers can develop marketing and product strategies that enhance long-term sustainability. Targeting high-value, repeat visitors such as the premier type can foster economic stability, while encouraging aspirational or value-conscious travelers through sustainable experiences can broaden market inclusivity. Overall, this study underscores that effective market segmentation not only drives destination competitiveness but also contributes to sustainable tourism development by promoting balanced and responsible consumption.

7. Limitations and Future Research

Several limitations should be recognized. The first limitation concerns the availability of data. Although the International Visitor Survey (IVS) has been conducted annually, only the 2009 dataset contained both household income and trip expenditure variables, which were essential for developing the income–expenditure typology. Therefore, the findings should be regarded as a theoretical and methodological foundation rather than a direct reflection of the current luxury tourism market. Future studies should replicate this approach using more recent datasets once comparable variables become accessible to verify the robustness of the model across time.

The second limitation relates to potential recall bias, as expenditure data were collected through self-report surveys at departure points. Although the IVS adhered to established guidelines for data collection, participants may have over- or underestimated their spending. Future research could utilize digital payment systems, transaction records, or real-time mobile surveys to enhance data accuracy and reliability.

Finally, this study focused primarily on economic and behavioral factors, whereas future research could integrate psychographic, cultural, and environmental variables to develop a more holistic understanding of sustainable luxury tourism. Comparative analyses across destinations and longitudinal research designs would further clarify how economic capacity and sustainability preferences evolve over time. Through these extensions, the income–expenditure framework could serve as a valuable tool for advancing both theoretical development and sustainable tourism practices worldwide.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.T.L., S.H.K. and Y.-R.K.; Methodology, Y.-R.K.; Software, Y.-R.K.; Validation, G.T.L., S.H.K. and C.H.; Formal analysis, S.H.K. and Y.-R.K.; Investigation, G.T.L., S.H.K., Y.-R.K. and C.H.; Resources, G.T.L. and S.H.K.; Data curation, Y.-R.K.; Writing—original draft, G.T.L., S.H.K. and Y.-R.K.; Writing—review & editing, C.H.; Visualization, Y.-R.K. and C.H.; Project administration, G.T.L.; Funding acquisition, G.T.L. and S.H.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Shinhan University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This study analyzed secondary data that are publicly accessible and do not contain any personal or identifiable information.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. The study utilized publicly available secondary data collected and provided by a government agency in South Korea.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available dataset was analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://know.tour.go.kr/stat/tourStatSearchDis19Re.do# (accessed on 25 October 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Travel and Tourism Council. Travel & Tourism Economic Impact Research (EIR). 2025. Available online: https://wttc.org/research/economic-impact (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Tourism and Competitiveness. 2025. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/competitiveness/brief/tourism-and-competitiveness#1/ (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Silverstein, M.J.; Fiske, N.; Butman, J. Trading Up: Why Consumers Want New Luxury Goods and How Companies Create Them; Penguin: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Yeoman, I.; McMahon-Beattie, U. Luxury markets and premium pricing. J. Revenue Pricing Manag. 2006, 4, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, G.I. A meta-analysis of tourism demand. Ann. Tour. Res. 1995, 22, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stabler, M.J.; Papatheodorou, A.; Sinclair, M.T. The Economics of Tourism, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, M. Luxury and Tailor Made Holidays, Travel and Tourism Analyst; Mintel International Group Ltd.: Chicago, IL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Vigneron, F.; Johnson, L.W. Measuring perceptions of brand luxury. J. Brand Manag. 2004, 11, 484–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.S.; Reisinger, Y.; Noh, E.H. Luxury shopping in tourism. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2010, 12, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, C.; Iverson, T.J. Expenditure-based segmentation: Taiwanese tourists to Guam. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Bai, B.; Hong, G.-S.; O’Leary, J.T. Understanding travel expenditure patterns: A study of Japanese pleasure travelers to the United States by income level. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spotts, D.M.; Mahoney, E.M. Segmenting visitors to a destination region based on the volume of their expenditures. J. Travel Res. 1991, 29, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S.; Crouch, G.I.; Devinney, T.; Huybers, T.; Louviere, J.J.; Oppewal, H. Tourism and discretionary income allocation. Heterogeneity among households. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Japutra, A.; Loureiro, S.M.C.; Li, T.; Bilro, R.G.; Han, H. Luxury tourism: Where we go from now? Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2022, 27, 871–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirumaran, K.; Jang, H.; Pourabedin, Z.; Wood, J. The role of social media in the luxury tourism business: A research review and trajectory assessment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, A.; Kozak, M.; Reis, H. Conspicuous consumption of the elite: Social and self-congruity in tourism choices. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 738–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrick, J.F.; Durko, A.M. Segmenting luxury cruise tourists based on their motivations. Tour. Mar. Environ. 2015, 10, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, C.; Lee, M.J.; Lee, S. A profile of spa-goers in the US luxury hotels and resorts: A posteriori market segmentation approach. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2019, 28, 1032–1052. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Pérez, F.M.; Bethencourt-Cejas, M.; Álvarez-González, J. The segmentation of canary island tourism markets by expenditure: Implications for tourism policy. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 961–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, C.; Singh, A. Families travelling with a disabled member: Analysing the potential of an emerging niche market segment. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2007, 7, 212–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolnicar, S. A review of data-driven market segmentation in tourism. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2002, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Bowen, J.T.; Baloglu, S. Marketing for Hospitality and Tourism, 8th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA; Pearson Education, Inc.: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, A.W.; Backman, S.; Backman, K.; Norman, W. Expenditure-based segmentation of sport tourists. J. Sport Tour. 2012, 17, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legohérel, P.; Hsu, C.H.; Daucé, B. Variety-seeking: Using the CHAID segmentation approach in analyzing the international traveler market. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legohérel, P.; Wong, K.K.F. Market Segmentation in the Tourism Industry and Consumers’ Spending. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2006, 20, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, J.; Eusébio, C.; Kastenholz, E. Expenditure-based segmentation of a mountain destination tourist market. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2012, 29, 695–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legohérel, P. Toward a Market Segmentation of the Tourism Trade: Expenditure Levels and Consumer Behavior Instability. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1998, 7, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizam, A.; Reichel, A. Big spenders and little spenders in US tourism. J. Travel Res. 1979, 18, 42–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Visitor Survey. Available online: https://know.tour.go.kr/stat/tourStatSearchDis19Re.do#/ (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Jenks, G.F. The data model concept in statistical mapping. In International Yearbook of Cartography; Bertelsmann Verlag: Gütersloh, Germany, 1967; Volume 7, pp. 186–190. [Google Scholar]

- Lockhart, R.S. Introduction to Statistics and Data Analysis: For the Behavioral Sciences; Macmillan: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Long, J.S.; Freese, J. Regression Models for Categorical Dependent Variables Using Stata; Stata Press: College Station, TX, USA, 2006; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).