Abstract

Sustainable and resilient hydrologic urban ecosystem services rely on connectivity among gray, green, and blue infrastructures. We conducted a field study of post-urban landscape hydrology in inland (River Rouge) and coastal (Detroit River) catchments on the West and East sides, respectively, of Detroit, MI. Measurements of parcel (n = 36) soil hydraulics as infiltration and drainage rates, soil taxonomic data, and depth of the groundwater table were used to determine connectivity. Hydrologic data was parsed into “stoplight” categories (green, yellow, orange, red) that at once communicate connectivity and best uses for sustained rendering of ecosystem services from vacant parcels. Parcels with yellow, orange, and red infiltration rates would respond to tillage and cover cropping with an increase in gray-green connectivity, whereas drainage rates in the orange and red categories suggest redevelopment. Blue-green connectivity was constrained by high variation in drainage rate, perched versus deeper saturated zones, urban drainage affecting local groundwater gradients, and relatively little groundwater data to compare against. This assessment process can serve to optimally allocate city resources to effectively and efficiently identify best management practices (including redevelopment) for vacant sites and to sustain ecosystem services, where they are most strongly rendered as connectivity amongst gray, green, and blue water regimes.

1. Introduction

The challenge of maintaining effective stormwater and wastewater infrastructure is common to global cities, where impervious surfaces have replaced pervious areas, which themselves have been reduced in their extent and continuity [1]. The imperviousness of conurbations diminishes the role of natural hydrologic processes associated with pervious vegetated land covers, which include interception-abstraction, infiltration, percolation, and evapotranspiration [2,3]. To limit flooding and maintain mobility and infrastructure, excessive stormwater runoff volume is routed to sewer collection and conveyance infrastructure. The aging and breakdown of sewer infrastructure and uncertainty in hydroclimate regimes [4] jointly affect sewer capacity and often lead to more frequent and severe system overflows. Among gray (i.e., “hard” infrastructure as engineered pipes, pumps, storage) and green (i.e., leveraging natural or engineered plant–soil systems to infiltrate and store runoff) management of wastewater and stormwater, the latter has attracted a great deal of attention to mitigate the hydrologic impacts of gray infrastructure, and toward improved stormwater-wastewater management [5] and adaptation to a changing hydroclimate [6]. Reconnection of urbanized landscapes with the hydrologic processes of abstraction, infiltration, percolation, evapotranspiration, and connectivity to groundwater and streamflow can create both losses and storage [3], which may sustain system capacity and its resilience as recovery from an impactful runoff flooding event. We approach the urban hydrologic cycle more broadly, and in terms of a connected continuum described by Kaushal and Belt (2012) [7]. In this framing, potential connections in the urban hydrologic cycle can span across gray, green, and blue. Blue assets are defined here as landscape connectivity with subsurface hydrologic fluxes (e.g., groundwater) and dynamic connections with river systems.

The natural and built environments interact to generate ecosystem services [8] as benefits to humans. The post-urban soil ecosystem can render regulating services, such as runoff mitigation through infiltration; supporting services, such as soil moisture to support flora and, hence, habitat for fauna; and provisioning services, such as recharging the water table to connect landscapes with surface waters. These post-urban landscapes are often both extensive and contiguous—features of green infrastructure—carrying forward the potential for maximizing the rendering of services [9]. By way of example, at least 20 percent of Detroit, Michigan, land area is vacant and vegetated. Yet, it is unclear the extent to which hydrologic ecosystem services can connect landscapes to water resources across the broader blue-green-gray hydrologic continuum [3]. These are management opportunities that bring together elements of couplings among gray-green, green-blue infrastructures, and render ecosystem services from post-urban landscapes such as these vacant remnant spaces.

Much of the research related to green stormwater infrastructure (GSI) has focused on site suitability and placement of GSI. The effectiveness of any given GSI installation depends in great part on the extent and continuity of GSI to approach or exceed that of the runoff management challenge [2]. Equally critical is a matching between GSI and site-level hydrologic processes and mechanisms. Our survey of the literature showed that the gray, green, and blue domains are often studied in the context of modeling with data drawn from spatial databases that have widely varying levels of resolution and completeness insofar as representation of hydrologic processes [3,10,11]. Where community values were elicited to site blue-green infrastructures in Eastern Canada, Lacroix et al. (2024) [12] found significant trade-offs between larger, less-resolved spatial datasets versus key data available at the finer scale of single or multiple contiguous parcels. In a physical modeling approach, Cavadini et al. (2024) [6] used a calibrated combined sewer system network model to test different combinations of blue-green infrastructure (BGI) for their potential to decrease combined sewer overflow (CSO) activation volume and frequency. The catchment hydrology throughout the study was estimated by way of numerous assumptions for important hydrologic processes. Using the city of Detroit as a case study for their multicriteria green infrastructure planning model, Meerow and Newell (2017) [9] incorporated estimates of the Rational Method C coefficient to scale relative peak runoff from vacant land, though it relies on coarse estimation of this lumped parameter, and sensitivity to the specific nature of precipitation events. Despite the merits of these studies, each tends toward the presumptive and speculative with regard to the selection of vacant land for both their hydrologic capacities and to focus on management needs. The performance of rainfall-runoff models is overall highly dependent on the spatial resolution of land use—land cover (LULC) and soil hydrologic data, such that each regulates runoff generation and its routing [3]. Parcel-level hydrologic data to verify management opportunities and limitations is notably absent. This is also to say that there are fewer resources spent on measuring the hydrologic capacities of landscapes to survey potential connections among gray, green, and blue infrastructures. Another persistent challenge to data-driven management and policy-making is the translation and communication of measured data to improve environmental management, policies, and their outcomes. For example, the Brazos Valley WaterSmart (bvwatersmart.tamu.edu; accessed 11 October 2025) uses measured water-use data and other factors to signal where and when landscape watering is called for. This signaling is visualized in real time by resident ratepayers with a stoplight approach (green: needs watering, red: does not need watering). In this way, data is represented as user-friendly behavioral cues that have effectively driven conservation of scarce groundwater resources.

By way of historical perspective, the year 1950 marked the peak population in Detroit (>1.8 M residents). At this time, the total impervious surface area was at a maximum, vacant regions were at a minimum, and sewer system capacity was fully utilized in a different hydroclimatic regime. With vacant land area now at a maximum, there is much opportunity to properly assess and leverage this land mass toward connectivity among gray, green, and blue infrastructures and gain ecosystem services. To meet current and ongoing management challenges in extensive urbanized landscapes, our research objectives are to leverage parcel-level hydrologic data to establish a range of variability in stormwater runoff potential, translate this data into the stoplight visual forum for effective communication, and simultaneously offer data-driven guidance on whether post-urban parcels should be conserved because they currently render hydrologic ecosystem services; managed according to specified deficiencies in services (i.e., low infiltration, drainage rate); or redeveloped (i.e., parcel is essentially impervious area) with contemporary low-impact development standards.

2. Site Description and Methods

2.1. Study Area

We study the Westside landscapes to the East of the Upper Reach of the River Rouge (where it enters Redford Township at Eliza Howell Park), which is not channelized, and eventually joins the Main Branch and outlets to the Detroit River. The land surface elevation ranges from approximately 182 m nearest to the River Rouge to 198 m (597 to 649 ft) in the interior. The Eastside nominally drains to the Detroit River, which drains South and into Lake Erie. The range of land elevation of the Eastside catchment area spans approximately from 190 m at the Western extent of our sampling to 179 m at the Eastern coastal sampling point (625 to 586 ft). All elevations are referenced to the North American Vertical Datum of 1988 (NAVD 88), which is the vertical control datum established in 1991 by the minimum-constraint adjustment of Canadian–Mexican–United States leveling observations.

2.2. Land Use—Land Cover and Site Selection Procedure

Land use—land cover (LULC) types in our sample set include residential and commercial vacant lots, parks, and public rights-of-way. The terrain in Detroit is generally gently sloping to flat topography that is inclined to the Southeast at a gradient of less than 0.2 m km−1 (ft mi−1). An initial list of potential vacant sites was supplied by the City of Detroit (ca. 180 sites), which we uploaded to a geographic information system, printed maps, and then did a windshield survey of each parcel in February 2013. We eliminated 130 sites due to a lack of safe access, obstruction of ingress and egress for tracked sampling equipment, or the structure was still on the parcel lot. From the 50 remaining available and accessible sites, we plotted them and found that they maximized geographic coverage to capture larger-scale variation in urbanized soil hydrology in Detroit and featured smaller clusters of sites to address smaller-scale variation in parcel-level hydrology (Figure 1). The final site selection was optimized on transit times among sites at an average pace of 3–4 sites per day for a 5-day workweek spent on each of the West and East sides of Detroit. This process led to a sample group that was stratified into a sampling plan by random factors, including availability (no structure on-site), restrictions due to safety concerns, and accessibility for equipment.

Figure 1.

(Upper): Map shows international-national geographic context for study sites in Detroit, MI. (Lower): (a) Site location summary and nominal watersheds for River Rouge on the West and Detroit River on the right, (b) Westside parcels in the River Rouge watershed, and (c) Eastside locations in the Detroit River watershed. Note that several neighborhoods on the West and East sides have clusters of parcels.

Field campaigns were conducted in the warm season (leaf-out) of 2013 and 2016, and we assessed a total of 36 parcels. We investigated 17 residential parcels or parks distributed across the Brightmoor and Grandmont communities, where the Upper Branch of the River Rouge descends from Redford Township, crosses Interstate 96 to the Main Branch of the River Rouge, and eventually empties into the Detroit River downstream of the Eastside study areas (Figure 1). In 2013, we assessed 14 sites across several Eastside communities (Hamtramck, Jefferson-Chalmers, Osborn, Poletown East), draining to the Detroit River in its course between Detroit, MI, and Windsor, Canada (CAN). In 2016, we assessed another set of 5 sites in the Eastside communities of Hamtramck and Poletown East (Figure 1).

2.3. Parcel Conditions and Soil Boring Method

The demolition procedure was as follows: structure demolished; basement and foundation excavated; backfill with human-altered, human-transported (HAHT) fill soil material; finish grading; and revegetation with a turf cover. Landscape cover was at least 90% for each parcel and composed of turf and a volunteer floral community. Deep-soil borings were taken in all 2013 assessments with direct-push soil sampling equipment (Geo-Probe, Salinas, KS, USA), and their full taxonomic characterization, including soil textural class, color, evidence of anthropogenic activity and artifacts, and water table depth at the time of assessment. Measurements were performed at the center of each parcel representing the most recently disturbed portion of the lot. For parks, right-of-way, and other unbounded parcels, we used the centroid of the area permitted for access as a reference point to set out equidistant measurement points along a line transect.

2.4. Measurement of Infiltration and Drainage Rates

We made field measurements of infiltration—the movement of water from the surface into underlying soils—and then the rate at which infiltrated water moved through a saturated soil matrix and subsoil as a proxy for drainage rate. We estimated infiltration as hydraulic conductivity (K) measured with a tension infiltrometer (Mini-Disk Infiltrometer, METER group, Pullman, WA, USA, metergroup.com). This measurement was made on each parcel in at least four locations, along a transect from the front to the rear of the parcel, with assessments within and outside the demolition envelope. The tension infiltrometer was set to a pressure head of −2 cm, placed on the soil surface (coarse organic matter brushed away, if necessary), and a time series of inflow rates were recorded at 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10, 15, 20 min, or until a consecutive three equal drops in water level at equal time intervals indicated the quasi-steady infiltration rate (cm h−1) at the specified tension. We used the recommended manufacturer procedures to calculate K (−2 cm). Measurement of subsurface saturated K in the centroidal, backfilled area of a parcel employed a constant head permeameter (Amoozemeter, Ksat, Inc., Raleigh, NC, USA; ksatinc.com) set to maintain a 15–25 cm depth of water in a borehole at slightly less than 1.2 ± 0.1 m (~4 ft) below ground surface, which is the average (±std. error of the mean) depth to the observed shallowest restrictive soil layer. Inflow to the borehole was observed at 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10, 15, 20 min., or until a quasi-steady inflow rate (cm h−1) was reached, which was then transformed to saturated K (0 cm) to estimate drainage rate [13].

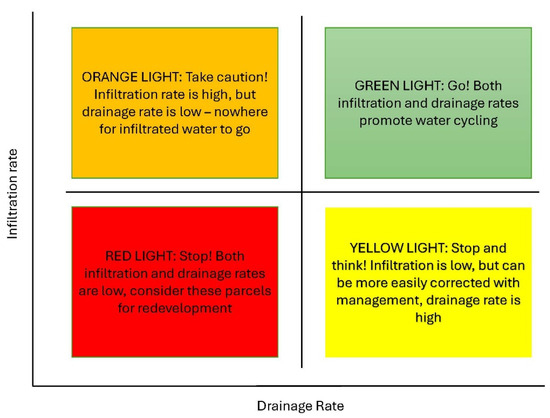

2.5. Sorting of Hydrologic Data with Stoplight System, Statistical Procedures

Hydrologic data was sorted into bins, with the lowest value assigned to red, the next-highest to orange, the next-highest to yellow, and then the highest values sorted into the green bin. The numerical ranges (bins) for hydrologic data were set according to nominal expectations for stormwater management using gray-green hydrology. The lowest end of color scales (i.e., red) for both infiltration and drainage rates is set at ≤1.27 cm h−1 (or ½ inch h−1). These are by nature the most frequent storm events (i.e., 1- and 2-year return periods) and have among the lowest total event rainfall depths with varying intensity [14,15]. The next higher bin starts at 1.28 cm h−1 and ends at ≤2.54 cm h−1 (or 1 inch h−1), and so on, using 2.54 cm h−1 to delineate between lower and higher ranges for both infiltration and drainage rates.

Parcel-level infiltration and drainage data were mapped on their own axes, and their symbology was assigned as per numerical bins corresponding to increasingly restrictive hydrologic conditions as green, yellow, orange, and red “lights” (Figure 2). By way of example, mapping field data onto this framing, parcels with green lights for infiltration and drainage metrics are highly functioning regarding hydrologic ecosystem services, such as regulation of stormwater runoff, and connectivity with blue assets. At the other extreme, red lights for both metrics direct the user to consider redevelopment of what is largely an impermeable parcel that minimally cycles rainfall or snowmelt inputs. The orange and yellow lights warn of higher infiltration rates without proper capacity to percolate this water and inform that slow infiltration is relatively easier to remedy than slow drainage. Note that yellow and orange signals are interchanged for drainage status. This arrangement emphasizes the impact of lower drainage rates on limiting connectivity and hydrologic services, as per the difficulty involved in improving drainage rates (e.g., by excavation, soil replacement, tile drainage, etc.).

Figure 2.

Summary stoplight approach to sorting infiltration and drainage rate field data. The descriptions embedded in each color field are worded for clear communication of prospects and limitations of observed parcel-level hydrology and, where applicable (Orange, Yellow), options for restorative management of parcel landscapes.

We used the Global Moran’s I geoprocessing algorithm in ArcGIS Pro (ver. 3.4.0, ESRI Inc., Redlands, CA, USA) to analyze spatial autocorrelation in surface soil textural class data. Categorical soil textural class data were reclassified to numerical codes (i.e., 10, 20, 30, …). The algorithm was set for spatial relationships among data points calculated by inverse distance, Euclidean (straight-line) distances between points, and the default spatial weight standardization by rows. Moran’s 1 value ranges from −1 (dispersion) to 1 (strong spatial patterning), and values closer to 0 indicate a random distribution of surface soil textural class. We report the Moran’s 1 value, and its significance as a p-value, which tests the null hypothesis that the data has a random spatial distribution. Fisher’s Exact Test (2-tailed) tested for independence among infiltration and drainage rate data sorted into stoplight categories. The test was conducted on a 2 × 2 contingency table for each of the Eastside and Westside hydrologic data. We combined the four stoplight categories into less and more restrictive categories (i.e., green-yellow, orange-red) with rows for infiltration, columns for drainage, and table elements were counts for each category. The test was performed in R (ver. 4.4.2, https://www.R-project.org/; fisher.test). The significance level for all statistical tests is defined as p < 0.10.

2.6. Identification and Characterization of Saturated Soil Layers

We characterized connectivity between green and blue assets (groundwater, surface waters) with measured depth to the saturated soil layer and Munsell soil color to estimate the legacy moisture regime as temporary or persistent [16,17]. This depth was identified by inspection of deep soil borings as the shallowest saturated layer of the soil profile. As a part of our soil taxonomy procedures, a Munsell soil color guide was used to classify the color of each distinct layer of the soil profile. Each color chip is named by its hue (e.g., 10YR (YR: Yellow-Red)), value (e.g., lightness, 3/), and chroma (strength of coloration, /3). The soil color under their natural condition estimated whether the soil moisture regime was wetter or drier. A gray (10YR 5/1) to pale brown (10YR 6/2) soil color indicated wetter, long-term reducing conditions. Likewise, if the soil were in the reddish-yellow-brown range (2.5YR 6/4), this would indicate a drier or temporarily wetter soil moisture regime, such as that found in a perched water table that is formed over a slowly permeable or impermeable soil layer.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of Gray to Green Connectivity

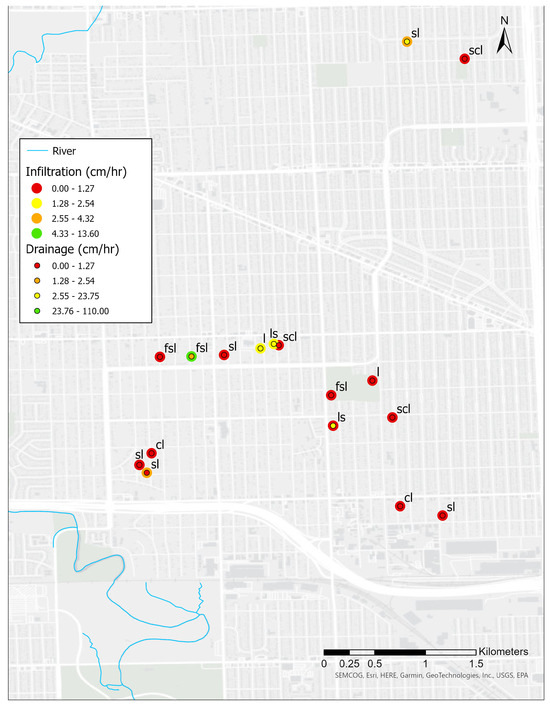

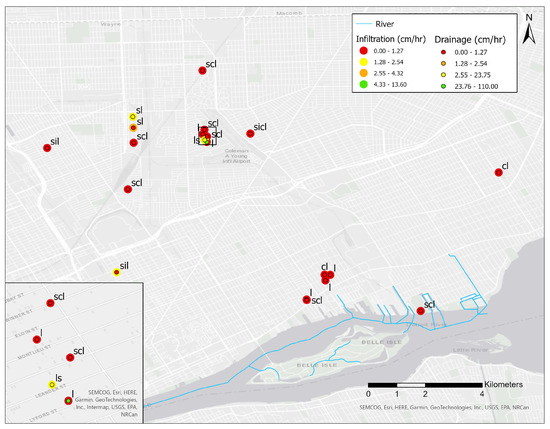

From most restrictive (red) to least restrictive (green) categories, most Westside parcel infiltration rates (Figure 3) ranked in the red category (12 out of 17), with two orange, two yellow, and one green. The range of surface soil textural classes spans from finer clay loams to the coarser loamy sand (Figure 3). Drainage rates are as follows: 12 sites sorted as red, one as orange, and four as yellow. For infiltration rates on the Eastside coastal catchment (Figure 4), 15 out of 19 parcels were at a red status, one orange, and three yellow, and none at a green status. Drainage on the East side ranked 16 out of 19 at red status, with two yellow and one green. Surficial soil textural classes were similar to Westside sites (Figure 4). Our analysis of spatial autocorrelation in surface soil textural class with Moran’s I indicated that the spatial arrangement of surface backfill soil texture was due to random chance for both the Westside (Moran’s I = −0.26, p-value = 0.34) and Eastside (Moran’s I = 0.19, p-value = 0.30) parcel groups. This result strongly indicates that the determinants of site selection yielded a randomized set of sites. Tests for independence among sorted Westside, Eastside infiltration and drainage rate data indicated for the Westside, that there is not a significant (p = 0.12) correspondence between less and more restrictive hydrologic categories; and for the Eastside, there is a significant (p = 0.05) correspondence between infiltration and drainage rates in their respective more restrictive orange-red categories.

Figure 3.

Westside Detroit River Rouge (Upper Branch) watershed with parcel locations and symbology according to infiltration rate (outer circle), and drainage rate (inner circle). Text abbreviations are soil textural class for surface soils (cl = clay loam, fsl = fine sandy loam, l = loam, ls = loamy sand, scl = sandy clay loam, sl = sandy loam).

Figure 4.

Eastside Detroit River watershed with parcel locations and symbology according to infiltration rate (outer circle), and drainage rate (inner circle). Text abbreviations are soil textural class for surface soils (cl = clay loam, fsl = fine sandy loam, l = loam, ls = loamy sand, scl = sandy clay loam, sicl = silty clay loam, sil = silt loam, sl = sandy loam).

3.2. Identification, Characterization of Saturated Soil Layers

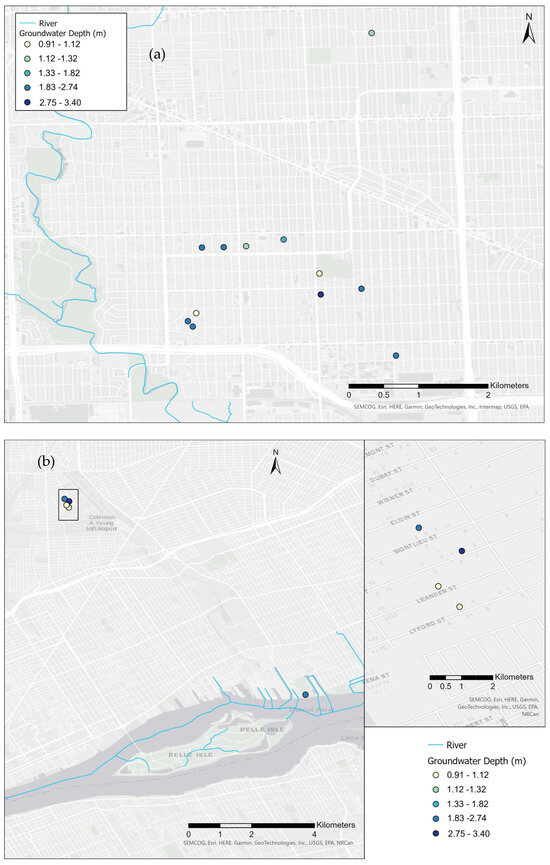

We observed water tables in either the more surficial HAHT fill material or in much deeper partially weathered bedrock, as C horizons or regolith (Figure 5). With few exceptions, we observed saturated zones of soil cores that exhibited soil color related to reducing conditions. The deeper saturated soil layers had colors that ranged from light gray (10YR 7/1) to pale brown (10YR 6/3), which indicates a persistently wet soil moisture status [16]. For shallower water tables, these are likely perched nearer to the surface, with some degree of aeration and a wetness regime that is more recent or at least less persistent than the deeper saturated zones. Soil redoximorphic cues in these zones were more oxidized and consequently had a light-yellow brown color (2.5YR 6/4) to very dark gray (10YR 3/1). Our observations of soil color and their wetness regime in the shallower and deeper parts of soil profiles are comparable to those found by Reuter and Bell (2001) [17] for iron-rich soils in East-Central Minnesota. This range of soil color is attributed to the relatively recent development of a perched water table after demolition (ca. 40 years) and backfill with HAHT material, compared to lighter gray soils observed in the deeper, legacy saturated zones [16,17]. For the Westside parcels, we found water tables predominantly clustered in the Southern half of the study catchment, distributed among the full range of depth categories (Figure 5a). On the Eastside, observation of water tables was sparser and separated by distance than that on the Westside, depth was highly variable in the Northwest cluster, and the hydraulic head at the site adjacent to the Detroit River (Maheras Gentry Park) was measured 175.3 m, slightly above the average Detroit River stage of 174.7 m, which was lower than normal in 2013 (Figure 5b). The similarity among these stages may indicate connectivity between these green and blue assets. Yet, this was a one-time measure and thus no dynamic relationship could be established.

Figure 5.

Groundwater depths observed at parcel scale for: (a) the Westside River Rouge (upper branch) catchment, and (b) the Eastside Detroit River catchment.

4. Discussion

4.1. Infiltration and Drainage Rates, Gray-Green Connectivity and Its Management

The gray-to-green hydrologic process in the vacant, post-urban landscape is driven by precipitation falling on both variably pervious (e.g., vegetated vacant lots, parks, and right-of-way) and impervious surfaces (e.g., roads, alleys, and other paved areas that drain to the sewer system). Through serial demolition to control blight, impervious areas such as sidewalks, roofs, driveways, and other related infrastructure have been removed. This leaves the landscape with a large proportion of disconnected impervious areas. Unmaintained roadways have weathered and now have substantial depression storage, which can limit the amount of runoff that flows into stormwater grate inlets, which are also commonly unmaintained, collapsed, and otherwise clogged. For these reasons, there is little impervious area left directly connected to the sewer system. Wastewater pipes are aged in place, and commonly have separated joints, cracks, and present opportunities for hydrologic via fluxes into and from the surrounding subsurface soils. Although the vacant lot’s residential sewer lateral has been disconnected from the neighborhood-level trunk wastewater conveyance, drainage into and through the backfilled parcel to the aged and leaky, buried wastewater infrastructure.

Our measurements quantified key regulators for infiltration and drainage processes. The slightly unsaturated measurement condition of K (−2 cm) simulates soil infiltration without macropore contribution. Given the uniform vegetation of the parcels, initial abstraction is high. For these reasons, the thresholds for infiltration rate stoplight signaling are conservative as there is likely more capacity for abstraction and infiltration on vacant parcels. Our sampling approach captured considerable variations in Human Altered Human Transported (HAHT) fill soil texture and its regulation of hydrologic properties. Based on our data, there is no spatial pattern in surficial soil textural class, which is attributed to non-standard sourcing of fill material and its placement. The major factor governing parcel-level infiltration and drainage was the HAHT soil texture and layering of backfilled soil material. We expected slow infiltration with the finer textures, though even these exhibited a wider range in stoplight status than we had expected. Different parcels with the same coarser surface soil textures exhibited contrasting infiltration rates. A fine sandy loam (fsl) soil has predominantly fine sands, which approach the size of silts, and should have a comparatively slower infiltration rate than an ordinary sandy loam [18]. Yet, adjacent parcels (Figure 3) with fsl textures have red and green infiltration status. This observation may be due to soil compaction during backfill operations, which can aggravate the tendency of fine sands to pack more densely and limit infiltration. The way soil was placed during backfill operations is thereby a likely factor influencing infiltration and drainage rates. Compaction from final grading would serve to limit infiltration from the surface to the depth of the excavation. Drainage rate would be diminished by typical backfill processes, which involve individual lifts of soil being compacted after placement. The overall demolition process, backfill soil sourcing, and its placement are all factors that can change the ecosystem services rendered by a vacant lot.

Since there is no discernible spatial pattern in surficial soil textural class at the parcel scale, this suggests that vacant parcels should be assessed prior to making any major decisions about re-use. Our data-driven approach would prevent lost opportunities to conserve parcels that signal green, identify and manage yellow areas, and engage in a no-regret consideration of low-impact development in parcels that were sorted (by both infiltration and drainage rates) into the orange or red quadrants. There were no parcels where hydrologic conditions signaled green for both infiltration and drainage. Parcels with infiltration rate data sorting into the yellow quadrant showed the greatest potential for restorative management to improve infiltration [11], followed by orange and red. The more restrictive orange and red parcels may call for more intensive interventions to correct deficiencies in infiltration rate. Selective tillage can be employed to break up slaked surface soils and subsurface hardpan (i.e., argillic horizons) and still retain soil structure. Soil management, such as cover cropping, can increase soil organic matter, tilth (the native Junegrass Koeleria macrantha; or otherwise, Red Clover Trifolium pratense; Oats Avina sativa), and create deeper rooting zones (e.g., Buckwheat, Fagopyrum esculentum) that can likewise improve infiltration and deeper drainage. These management approaches can be implemented to improve infiltration rates over time and shift parcel hydrologic response into the green quadrant.

In the broader scope of urban land management, our approach imparts clear guidance for prioritizing vacant land for further management. This field campaign was a 75,000 USD (2025) investment in assessing and measuring the range of variability in soil hydrologic conditions across post-urban landscapes in Detroit, MI. A single green infrastructure practice (e.g., rain garden) would cost at least 10,000 USD to install. Given our assessment results, it is likely that a rain garden would be placed on a parcel (or parcels) with red hydrologic status. Further, there is evidence that a parcel with more restrictive hydrologic conditions ranks in the orange-red category for both infiltration and drainage rates. Any further investment in an orange or red parcel would be risky regarding improvement in gray-green-blue connectivity. For parcels with the most restrictive hydrologic conditions, especially poor drainage rates, the LID approach may appropriately consider water features such as wet ponds, small wetlands, etc., according to community preferences. We posit that hydrologic services that regulate stormwater runoff can directly affect cultural services (e.g., aesthetics, neighborhood commonwealth). If GSI is not effective (e.g., overflowing, plant mortality, odors, breeding ground for disease vectors and pests (e.g., mosquitoes, Aedes, Culex, Anopheles spp.), then cultural ES are compromised as lost social capital and damage to a sense of well-being. It is also arguable that if the GSI structure is such that any of its functions are compromised, then the benefits of habitat (provisioning ES), or nutrient cycling and carbon storage (supporting ES) are also lost.

4.2. Perched, Permanent Saturated Soil Layers and Blue-Green Connectivity

The hydrologic process that connects green to blue assets is represented by the depth of the apparent groundwater table (Figure 5) and its corresponding soil color. In general, the spatial reach of a water table becomes more extensive (versus localized) with an increase in depth. The deeper groundwater resources are then more likely to interact with the adjacent blue assets, such as the River Rouge and Detroit River. A shallower (or perched) water table sits on an impermeable or slowly permeable soil layer or lens. Human-altered human-transported (HAHT) soil material filled the top 2–3 m of the basement excavations. The new, mixed backfill soils drive variation in soil and hydrologic properties, which can substantially differ among parcels, and even among those that are close to each other. Soil redoximorphic status in saturated soils is associated with iron-rich illitic clay minerals in temporary or persistent saturated conditions, wherein the iron is reduced, and soil color shifts to the gray range. There is scant evidence (Figure 3 and Figure 4) of sites with yellow or green drainage status overlying deeper (i.e., not perched) saturated soil layers that, given their soil color, are generally permanent. These sites would otherwise percolate and recharge deeper groundwater resources. It is possible that with the correction of low infiltration rates, parcels in the yellow drainage quadrant would drain or percolate to the shallower perched water tables. Even in the case of parcels that are designated orange, percolation over the longer term (ca. 50–100 years) would connect drainage from the near-surface with deeper water tables.

The Upper Reach of the River Rouge and the Detroit River courses are each highly urbanized, imparting to the subsurface drainage regime the urban karst effect discussed by Kaushal and Belt (2012) [7], which is expanded upon by Bonneau et al. (2017) [19]. The City of Detroit is on a combined sewer system, which collects both sanitary and stormwater flows in the same pipe. This system is at least 100 years old and increasingly in a state of hydraulic exchange with the surrounding subsurface strata and soil water. A difference in hydraulic head between the pipe and water table will dictate whether groundwater inflows to the pipe through cracks and separated joints [3], or if the pipe (closer to full flow) forces exfiltration into the bedding materials that surround the pipe. Additional sources of drainage from parcels are through their prior connection (via the residential sewer lateral pipe), such that all parcels are located adjacent to the neighborhood block-level combined sewer trunkline, and leakage from aged, pressurized drinking water pipes. Non-revenue drinking water pipe leaks are losses that may not be discovered for years and add to soil moisture and groundwater. On the other hand, perching may prevent shallow saturated layers from moving into fractured pipes that are placed deeper into the soil strata (i.e., 4–6 m). More generally, evapotranspiration losses during the warm growing season diminish the amount of precipitation available for percolation [19]. This seasonal effect would then be expected to more strongly affect the local water tables more proximate to the surface and subject to capillary fringe effects and root uptake of soil moisture, which are estimated to extend to 2 m depth.

To different degrees, each river course is at times isolated and influenced by its watershed areas (where the parcels are located), water table dynamics, and stormwater management in the freeway transit corridors. These features of urban karst interrupt both subsurface flow pathways and groundwater directional gradients [3,7]. Both the West (Interstate 96) and East (Interstate 94) freeway networks have pumped drainage systems that are in the paths between the parcels and their corresponding river reaches. These systems lower the proximate groundwater table (dewatering), and during stormflow, pump stormwater runoff from the freeways to the local combined sewer system [20]. Groundwater directional gradients have been distorted by obstructions and dewatering. The extent of these impacts on groundwater gradients in the Upper River Rouge catchment is largely uncharacterized due to a dearth of groundwater monitoring data. However, the Eastside had the benefit of ca. 7 years of groundwater level data from a dense well field (Recovery Park complex (42.369652, −83.043198)) from which Hoarde et al. [21] found that the groundwater directional gradient was primarily from the SE to NW direction, away from the Detroit River.

For these reasons, blue-green groundwater connectivity can engage in a losing and gaining dynamic with the River Rouge and Detroit River. Given infiltration and drainage limitations, soil layering, dewatering, and redirection of groundwater directional gradients, each can act to regulate the temporal scale and overall dynamic of connections with riverine systems. Yet, based on our measurements, the connection between green landscape and blue riverine assets as groundwater is not likely to be widespread. Blue-green connectivity is qualitative and estimated to be dominated by the larger regional network that would support ecological flows in river courses. We rely here entirely on boring soil data to generalize groundwater connectivity. What underlies any aspect of this analysis is that there is a great deal of variation in groundwater flow direction, which is attributed to what is a highly disturbed, urbanized regional strata, with many influences on groundwater directional gradients. These data deficits should be the focus of a different long-term field campaign that characterizes variability in shallow and deeper saturated zones, their connectivity, and dynamics as groundwater resources interact with the River Rouge and Detroit River.

5. Conclusions

We parsed vacant land parcels with their measured hydrologic capacities into “stoplight” categories (green, yellow, orange, red) that communicate best uses for sustained rendering of ecosystem services in post-urban landscapes, and surveyed the potential for blue-green infrastructure as a coupling between catchment areas with their respective river reaches in the city of Detroit, MI. Gray-green connectivity was limited, yet identified parcels that would respond to straightforward management. Blue-green connectivity was constrained by variation in perched versus deeper, more permanent saturated soils; the impacts of urban drainage on groundwater spatial gradients; and an overall dearth of data characterizing groundwater dynamics in each of the catchments studied. Despite the practical limitations on the number of sites assessed, our data suggest that the spatial distribution of sites is random, supporting the generalization of results, at least in the Detroit area. This work addresses a major gap in the urban environmental management literature by providing a straightforward application of field practice that defines best management practices that maximize regulating ecosystem services, such as runoff mitigation (as elimination or disconnection of impervious areas, gray infrastructure) and restoring some degree of connectivity between the landscape (green) and deeper water cycles (blue). We suggest that this straightforward assessment, as employed in this work, could be customarily conducted to strategically use vacant land to enhance hydrologic connectivity and to enhance stormwater management, among other hydrologic ecosystem services, for the larger urban environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.S., M.G., T.S., A.S. and S.P.; methodology, W.S.; formal analysis, W.S. and M.G.; investigation and fieldwork, W.S., T.S., A.S. and S.P.; writing—original draft preparation, W.S.; writing—review and editing, W.S., M.G., T.S., A.S. and S.P.; visualization, W.S. and M.G.; supervision, W.S.; project administration, W.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Over the course of work conducted for this study and according to their contributions, S.P., T.S., and A.S. were graduate fellows funded under a grant from the National Science Foundation, Grant No. 1735038.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The 2013 and 2016 data are published in a publicly available USEPA archive. Data have been deposited in the Environmental Protection Agency Science Hub repository (https://catalog.data.gov/harvest/about/epa-sciencehub, https://doi.org/10.23719/1407673, last accessed 10 October 2025).

Acknowledgments

Wayne State University rests on Waawiyaataanong, also referred to as Detroit, the ancestral and contemporary homeland of the Three Fires Confederacy. These sovereign lands were granted by the Ojibwe, Odawa, Potawatomi, and Wyandot nations in 1807 through the Treaty of Detroit. Wayne State University affirms Indigenous sovereignty and honors all tribes with a connection to Detroit.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MI | Michigan |

| GSI | Green Stormwater Infrastructure |

| CAN | Canada |

| NAVD88 | North American Vertical Datum of 1988 |

| BGI | Blue-green Infrastructure |

| CSO | Combined Sewer Overflow |

| LULC | Land Use Land Cover |

| USDA | United States Department of Agriculture |

| HAHT | Human Altered, Human Transported |

| PGI | Passive Green Infrastructure |

| cl | Clay loam |

| fsl | Fine sandy loam |

| l | Loam |

| ls | Loamy sand |

| scl | Sandy clay loam |

| sl | Sandy loam |

| sicl | Silty clay loam |

| sil | Silt loam |

| USGS | United States Geological Survey |

| SE | Southeast |

| NW | Northwest |

| LID | Low Impact Development |

| USD | United States Dollars |

| ES | Ecosystem Services |

References

- Klimanova, O.; Illarionova, O.; Grunewald, K.; Bukvareva, E. Green Infrastructure, Urbanization, and Ecosystem Services: The Main Challenges for Russia’s Largest Cities. Land 2021, 10, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.J.; Welty, C.; Duncan, J.M.; Baeck, M.L.; Smith, J.A. Assessing Urban Rainfall-runoff Response to Stormwater Management Extent. Hydrol. Process. 2021, 35, e14287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswald, C.J.; Kelleher, C.; Ledford, S.H.; Hopkins, K.G.; Sytsma, A.; Tetzlaff, D.; Toran, L.; Voter, C. Integrating Urban Water Fluxes and Moving beyond Impervious Surface Cover: A Review. J. Hydrol. 2023, 618, 129188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, S.; Coats, S.; Touma, D.; Cole, J.; Lehner, F.; Fasullo, J.; Otto-Bliesner, B. Twenty-First Century Hydroclimate: A Continually Changing Baseline, with More Frequent Extremes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2108124119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendricks, M.D.; Dowtin, A.L. Come Hybrid or High Water: Making the Case for a Green–Gray Approach toward Resilient Urban Stormwater Management. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2023, 59, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavadini, G.B.; Rodriguez, M.; Nguyen, T.; Cook, L.M. Can Blue–Green Infrastructure Counteract the Effects of Climate Change on Combined Sewer Overflows? Study of a Swiss Catchment. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 094025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, S.S.; Belt, K.T. The Urban Watershed Continuum: Evolving Spatial and Temporal Dimensions. Urban Ecosyst. 2012, 15, 409–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (Program) (Ed.) Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-1-59726-040-4. [Google Scholar]

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P. Spatial Planning for Multifunctional Green Infrastructure: Growing Resilience in Detroit. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 159, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanches, P.M.; Pellegrino, P.R.M. Greening Potential of Derelict and Vacant Lands in Urban Areas. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 19, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Guo, Z.; Li, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, X.; Liao, J. Integrating Hydrological and Economic Assessments of Soil Infiltration Enhancement for Urban Flood Resilience. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 1000, 180383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacroix, S.; Kuller, M.; Gougeon, G.; Petrucci, J.; Lemieux-Chalifour, F.; Rioux, A.; Dagenais, D.; Bichai, F. Can We Stop Reinventing the Wheel in Blue-Green Infrastructure Planning? Using Value-Focused Thinking to Enable Transferability of a Multicriteria Planning Support System. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2024, 252, 105188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoozegar, A. A Compact Constant—Head Permeameter for Measuring Saturated Hydraulic Conductivity of the Vadose Zone. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1989, 53, 1356–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, C.D.; Spahr, K.; Grubert, E.; Stokes-Draut, J.; Gallo, E.; McCray, J.E.; Hogue, T.S. Decision Making on the Gray-Green Stormwater Infrastructure Continuum. J. Sustain. Water Built Environ. 2019, 5, 04018016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perica, S.; Martin, D.; Pavlovic, S.; Roy, I.; Laurent, M.S.; Dale, C.T. Precipitation-Frequency Atlas of the United States, Midwestern States; NOAA Atlas 14; NOAA: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2013; Volume 8, Version 2. Available online: https://www.weather.gov/media/owp/oh/hdsc/docs/Atlas14_Volume8.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Smirnova, M.A.; Kozlov, D.N. Soil Properties as Indicators of Soil Water Regime: A Review. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2023, 56, 306–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, R.J.; Jay, C.B. Soils and Hydrology of a Wet—Sandy Catena in East—Central Minnesota. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2001, 65, 1559–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schifman, L.A.; Shuster, W.D. Comparison of Measured and Simulated Urban Soil Hydrologic Properties. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2019, 24, 04018056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonneau, J.; Fletcher, T.D.; Costelloe, J.F.; Burns, M.J. Stormwater Infiltration and the ‘Urban Karst’—A Review. J. Hydrol. 2017, 552, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haefner, R.J.; Hoard, C.J.; Shuster, W. Hydrologic Study of Green Infrastructure in Poorly Drained Urbanized Soils at RecoveryPark, Detroit, Michigan, 2014–2021; Scientific Investigations Report; US Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoard, C.J.; Haefner, R.J.; Shuster, W.D.; Pieschek, R.L.; Beeler, S. Full Water—Cycle Monitoring in an Urban Catchment Reveals Unexpected Water Transfers (Detroit MI, USA). J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2020, 56, 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).