Abstract

Taking Harbin morning market as a case study, this study explores sustainable production schemes for generating sense of place in urban spaces amid the trend of modernization. Employing grounded theory, it develops an analytical model consisting of three components: space, humans, and materials. The findings reveal that place identity emerges from functional redundancy and self-organizing spatial layouts, where the hybrid logic of spatial design, the non-programmed interactions of human actors, and the material networks together enable tourists to transform from spectators into embodied participants. Theoretically, this study proposes a hybrid logic and challenges high modernism. It emphasizes that fully mobilizing the spontaneous vitality of every actor in the space is more effective than unilaterally improving rules and functions, offering a sustainable path for nurturing localized cultural ecosystems against homogenization.

1. Introduction

In the context of modernization and globalization, the dissolution and reconstruction of local identity have emerged as central concerns in tourism sociology research, with the sustainable development of regional culture and tourism spaces being a key objective of this field. Contemporary urban development, driven by functionalist and efficiency-oriented logics, often pursues “pure and orderly” urban landscapes through spatial compartmentalization and regulated governance. This approach has led to the submersion of local cultural symbols under standardized and homogenized frameworks, resulting in a nationwide crisis of “indistinguishable streetscapes” in tourist destinations. Commercialization has encroached excessively on cultural spaces, reducing tourist experiences to mere commodity consumption rather than profound engagements with regional heritage. Against this backdrop, the morning market culture in Harbin, Heilongjiang Province, has emerged as a countercurrent, exemplifying the reconstruction of a sense of place.

According to a survey conducted by the Heilongjiang Provincial Bureau of Statistics on over 200 key tourism projects in the province involving nearly 40,000 business entities during the 2025 ice–snow tourism season, Harbin received 90.357 million tourist visits, generating CYN 137.22 billion in revenue, marking year-on-year increases of 9.7% and 16.6% compared to the previous two years. These survey data are mainly calculated based on the daily passenger flow and consumption volume of each business entity [1,2]. Notably, grassroot spaces like Hongzhuan Street Morning Market have become viral attractions, celebrated for their “everyday vitality” and “human warmth.” Tourists no longer settle for passive “spectatorial gazing” through glass partitions but instead seek immersive interactions in authentic urban real-life worlds, craving tactile encounters with the city’s lived textures [3]. This phenomenon not only reflects a paradigm shift in tourist attractions—from “landscape consumption” to “lived experience”—but also unveils the dynamic negotiation between tradition and modernity in constructing place identity. The entrance map of Hongzhuan Street Morning Market is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The entrance of Hongzhuan Street Morning Market.

The cultural tourism transformation of Harbin’s morning markets epitomizes a tactical expression of locality under modernizing pressures. Through policies such as the Harbin Municipal Policies on Boosting Development Confidence and Promoting Comprehensive Economic Recovery and Improvement, the municipal government has strategically endorsed “disorderly” spaces like morning and night markets as urban cultural icons, balancing livelihood preservation with economic revitalization [4,5]. By integrating localized symbolic practices with institutional governance, Hongzhuan Street Morning Market has been reconfigured into an affective arena fostering socio-spatial bonds [6]. As scholars such as Sun Jiuxia have pointed out, the construction of locality, informal order, and negotiation among multiple subjects in tourist sites has contributed to the success of Harbin’s tourism industry [7]. Wang Shusheng also argues that the development of the emotional value of the “hospitality” folk custom is of great significance in tourism development [8]. Wen Xin also took the tourism industries of Harbin, Zibo, and other places as examples, and summarized the importance of embodied experience and non-institutionalized environments [9]. These consensuses indicate that this hybrid space simultaneously satisfies tourists’ quest for “authenticity” and sustains the city’s distinctive local nature, forming a sustainable reproductive structure of “cultural performance–spatial construction–economic development.”

Therefore, taking Harbin’s morning markets as an entry point, this study attempts to propose a theoretical framework of “postmodern locality production.” It explores how urban neighborhoods can resist the risk of locality dissolution under the trend of modernization through multiple dimensions, including space, human actors, and non-human actors. Furthermore, it reveals the dynamic negotiation mechanism between tradition and modernity in the construction of a sense of place, aiming to provide a new path for the preservation of locality in the process of global urbanization.

2. Literature Review

2.1. High Modernism and the Erosion of Locality in Tourism

High modernism, as the ideological core of modern social engineering, seeks to construct a myth of linear progress through the absolutization of technological rationality. As James C. Scott notes in Seeing Like a State, “High Modernism is best conceived as a strong, one might even say muscle-bound, version of the self-confidence about scientific and technical progress, the expansion of production, the growing satisfaction of human needs, the mastery of nature (including human nature), and above all, the rational design of social order” [10]. High modernism dismisses local practices as “disordered chaos,” attempting to erase the organic nature of place-based cultures through functional zoning and spatial discipline, ultimately leading to the alienation and dissolution of locality. In tourism, this manifests as the instrumental transformation of local cultures. On one hand, functional zoning logic reduces place-based cultures to quantifiable “traditionality concentration” metrics, fabricating essentialist cultural imaginaries [11]. On the other hand, informal urban landscapes like markets and street vendors are deemed “misplaced existences,” subjected to a spatial discipline that strips them of cultural significance [12]. Consequently, local cultures are fragmented into modularized consumption experiences, and their authenticity is dismembered by technocratic governance, culminating in homogenized tourism spaces [13].

Existing studies under the high modernist paradigm primarily follow three interventions: First is the exclusion of “disordered” urban spaces through rigid functional zoning. For instance, Huang Gengzhi and Xue Desheng’s study on Guangzhou’s street vendor governance reveals how “vending zones” compress mobile vendors into surveilled administrative units [14]. Sun Zhijian advocates “strategic, politicized, and rule-based governance” to phase out informal vendors [15], while Zhuo Chengxia and Guo Caiqin critique such practices as reducing grassroot life into “standardized modules” compliant with modernist urban esthetics, erasing their organic cultural networks [16].

Second is the overemphasis on technological solutions in tourism development. Chen Rong argues that modern technologies expand tourism markets but threaten traditional landscapes [17]. Li Jingyi et al. critique the techno-fetishism in “smart tourism,” highlighting how reliance on systemic technologies formats cultural ecosystems [18]. Such contradictions expose tourism’s modernist project as simplifying cultural complexity into governable objects [19].

Third, the fusion of high modernism with linear historiography reinforces a “traditional–modern” binary, polarizing landscape production. Jiang Keke and Xiong Zhengxian’s study on cultural tourism towns highlights developers simplifying rural cultures into homogenized “pastoral fantasies” for urban consumers [20]. Guo Weifeng critiques modernity’s “rational gaze” disciplining landscapes into commodified stereotypes [21], while Peng Dan and Huang Yanting attribute Lijiang Ancient Town’s loss of authenticity to excessive commercialization and formulaic development [22].

2.2. Theoretical Pathways for Reconstructing a Sense of Place

The concept of sense of place originates from human geography’s philosophical distinction between “space” and “place.” Yi-Fu Tuan, in Space and Place, defines “space” as a neutral physical arena and “place” as a geographical unit imbued with human emotion, memory, and practice—a “center of meaning” [23]. Edward Relph’s authentic sense of place theory emphasizes the stability of place identity, contingent on the continuity of material landscapes, social relations, and cultural traditions [24]. Clifford Geertz’s local knowledge framework posits that place-specific cognitive systems are shaped by long-term environmental and socio-structural interactions, characterized by situatedness (embeddedness in context), non-universality (heterogeneous experience), and embodied praxis (knowledge reproduction through daily acts) [25]. Traditional theories assume that place identity relies on the sustained reproduction of local knowledge via community participation, oral traditions, and material preservation.

To counter tourism’s homogenization crisis, scholars propose reconstructing a sense of place through three pathways: First is narrative reconstruction via media. Tang Shunying and Zhou Shangyi argue that travel guides and blogs reinforce tourists’ cognitive and emotional engagement with cultural symbols across pre-trip anticipation, on-site experience, and post-trip reflection [26]. Gao Caixia et al. demonstrate how digital media transforms locality into communicable symbols, forging “imagined communities” among tourists [27]. Qi Yuan similarly highlights the media’s role in shaping tourists’ place perceptions [28]. Second is destination image design. Shaykh-Baygloo Raana’s study on Shiraz, Iran, proves that attraction quality strengthens place attachment through visual, functional, and affective dimensions [29]. Wen Yongwei advocates blending historical memory with contemporary practices in red tourism to achieve “traditional-modern” equilibrium [30]. Tang Wenyue and Zhang Ji measured tourists’ place identity in Jiuzhaigou, identifying natural landscapes as the primary affective driver [31]. Third is embodied place-making. Zeng Li, Gao Quan, and Chen Xiaoliang propose “embodied reconstruction,” where physical acts like walking and handicrafts internalize cultural memory [32]. Gao Yuhong and Xiang Lanlin find that traditional village homestays activate multisensory interactions to align with local esthetics [33]. Wang Le and Zhang Ying’s study on Shaanxi’s Yuanjia Village shows how immersive experiences foster holistic cultural engagement and collective identity [34].

2.3. Morning Markets as Informal Spaces for Place Identity Generation

As informal economic spaces, morning markets create unique spatial narratives through ritualized performances of daily life. These vernacular spaces defy functionalist urban planning, carving elastic cultural fields within modernist efficiency regimes.

Current research identifies three mechanisms for place identity generation in morning markets: First, spatial reappropriation by mobile vendors transforms transit zones into hybrid spaces of commerce and social interaction, enriching tourist experiences [35]. Second, resistant symbolic systems—local dialects, artisanal skills, and street esthetics—form a cultural grammar countering standardization. These multisensory symbols sustain place memory, offering tourists deeper cultural engagement beyond commodified spectacles [36,37]. Third, non-contractual vendor–customer interactions reproduce trust mechanisms rooted in local ethics. Such social networks foster tourist belonging, embedding emotional bonds within flexible spatial practices [38].

2.4. A Critical Evaluation of the Existing Literature

Existing studies, while revealing high modernism’s erosion of place identity and proposing reconstruction pathways, remain trapped in modernist paradigms. Three limitations persist: overemphasis on “participation” and “interaction” as foundational to locality, without addressing the sustainability of such processes; quantification of local knowledge—reducing place identity to calculable variables under institutional norms erodes its spontaneity; persistent social engineering logic—programmatic “orderliness” excludes “disordered” spaces like markets, neglecting their potential as living repositories of local knowledge.

These limitations reflect a theoretical blind spot: framing place-making as an “ordering project,” while overlooking the generative value of hybridity, redundancy, and self-organization. By analyzing Harbin’s morning markets, this study demonstrates how functional hybridity and surface disorder convert “inefficient redundancy”—vilified by high modernism—into mechanisms of place uniqueness. This challenges the “order participation,” proposing that place identity can arise not only in the absence of controlled interactions, but also in conjunction with the adaptive resilience observed in seemingly disordered environments. Such insights offer a new cognitive framework for sustaining locality in global urbanization.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Methodology

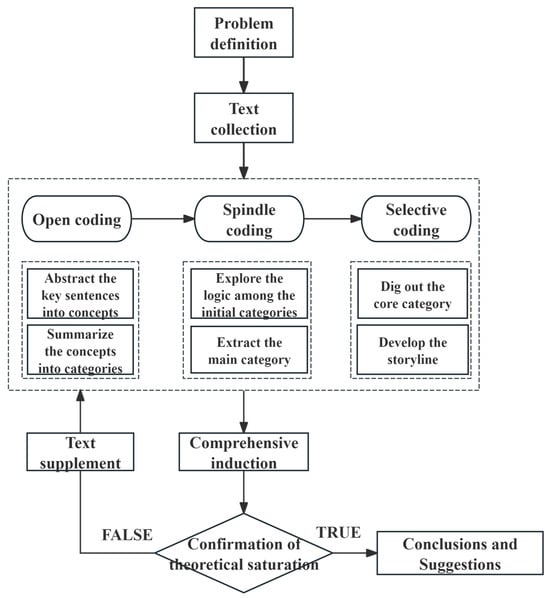

This study employs grounded theory [39], a qualitative methodology closely aligned with sociological inquiry, to uncover fundamental social processes underlying observed phenomena. Grounded theory bridges theoretical and empirical research by suspending pre-existing frameworks, prioritizing theory generation over verification, and emphasizing sociological creativity—making it ideal for under-theorized domains like informal tourism spaces, and the specific framework is shown in Figure 2. Crucially, while this study presents its theoretical stance upfront for clarity, the research process strictly adhered to grounded theory principles, avoiding a priori assumptions.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of grounded theory research.

3.2. Data Sources

This study employed one-on-one semi-structured interviews to collect empirical data. To ensure the representativeness and scientific rigor of the sample, the research team carefully considered participants’ demographic backgrounds and personal characteristics. A purposive sampling strategy—a non-random sampling method guided by the researchers’ expertise and the study’s objectives—was adopted to select participants. In-depth interviews were conducted with 13 participants, utilizing multiple formats including face-to-face meetings, WeChat voice calls, and Tencent video conferences. Prior to each interview, participants were informed of the study’s purpose and provided with privacy protection assurances, ensuring confidentiality through informed consent protocols.

Participants were recruited through online social media platforms and travel forums. Strict inclusion criteria were adopted. All participants must have visited Hongzhuan Street Morning Market during the designated study window (2025 winter season) to ensure the authenticity and timeliness of their experiences. To mitigate potential recall bias, we controlled the time intervals between market visits and interviews, with all time intervals not exceeding one month. For details, please refer to the table below. Preliminary data analysis and coding were conducted for the first 10 participants (FT-01 to FT-10), initially reaching theoretical saturation. The final three participants (FT-11 to FT-13) were recruited and interviewed as validation steps to confirm that no new substantive topics emerged, thereby strengthening the robustness of the research results. The following table provides detailed demographic information and key time data for all 13 participants.

The research process also involved numerous elements within the morning market field, such as vendors, market stewards, facilities, and commodities. The functions performed by these elements in the morning market space are often immediate and contextual. On the one hand, these functions are presented through the statements made by tourists in interviews, which serve as the basic data for grounded theory construction. On the other hand, from 1 January 2025 to 7 February 2025 (the end of the statutory Spring Festival holiday), the researchers visited Hongzhuan Street Morning Market twice a week at irregular intervals to conduct field observations. While conducting fragmented interviews with on-site tourists and vendors, the researchers observed processes such as commodity transactions and dispute resolution and watched tourists dining and wandering; they then compiled field memos. These field materials and the interviewees’ statements mutually corroborate each other. The demographic characteristics of the research participants are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of study participants.

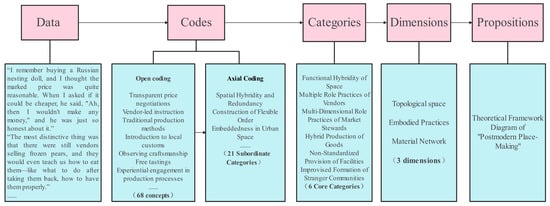

3.3. Open Coding

As the initial phase in grounded theory methodology, open coding involves decomposing raw data and extracting representative phenomena and statements to form primary concepts which are then categorized to achieve intuitive clarity of materials. All three authors participated in the coding, extracting, and condensing of the data collected during the interviews into semantic labels and refined them through coding elements to establish a preliminary conceptual framework. Through iterative coding cycles, revisions, and optimization, including regular discussions and peer reporting meetings to address coding differences and reach consensus, the team ultimately produced 68 key concepts. Guided by the core research propositions and logical connections between concepts, these were further synthesized into 21 distinct categories. This coding framework was subsequently proposed at the annual meeting of the Chinese Sociological Association and was recognized by peers, thus ensuring the rigor and credibility of its analysis. A representative example of open coding is presented in Table 2 (due to space constraints, similar textual materials are represented by single excerpts with one category group retained).

Table 2.

Example of open coding.

3.4. Axial Coding

Axial coding builds upon open coding by synthesizing inductive and deductive approaches to distill core categories that best encapsulate the research themes. The research team revisited the primary concepts and categories generated during open coding, systematically analyzing their logical relationships—such as inclusion, parallelism, and causality—within the original textual data. Through this iterative process, six core categories were identified: functional hybridity of space, multiple role practices of vendors, hybrid production of goods, non-standardized provision of facilities, improvised formation of stranger communities, and multi-dimensional role practices of market stewards. The axial coding framework is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Axial coding framework.

3.5. Selective Coding and Framework

Selective coding involves analyzing relationships between core categories, developing a storyline that synthesizes all observed phenomena, and identifying a central category that unifies all concepts through constant comparative analysis. The storyline, based on the collected data and derived concepts/categories, succinctly captures the essence of the studied phenomenon. This study’s storyline revolves around “tourists’ sense of place in Hongzhuan Street Morning Market,” integrating six core categories into the following narrative: As tourists approach the market, the hybrid architecture (blending Chinese and Western elements) and historic cobblestone paths subtly introduce the area’s “spatial hybridity.” This visual complexity primes visitors for the multisensory experience ahead. Upon entering, the market’s “embedded urban spatiality” becomes palpable: official signage mingles with improvised banners, stalls cluster in seemingly chaotic yet functionally coherent arrangements, and the cacophony of vendor calls merges with steam rising from insulated food containers, creating a resilient, self-organizing order. While queuing for snacks, spontaneous conversations arise between strangers. These unscripted interactions foster “emergent care networks”—passing tissues or sharing tips—that dissolve anonymity. At stalls, vendors engage in “non-scripted interactions,” adapting to tourists’ needs while imparting local knowledge and emotional warmth. Even law market stewards subvert expectations: clad in northeastern floral-patterned jackets, they mediate disputes with humor and folksy charm, embodying “improvised governance.” As tourists explore, they encounter goods imbued with symbolic meaning beyond utility. Some stalls invite participation in craft-making, transforming consumption into cultural immersion. Gradually, the space shifts from backdrop to protagonist—its “spatial meaning-making” connects personal memories to collective narratives, elevating individual experiences into cultural belonging. The interconnection of six main categories yields the theoretical framework for “postmodern place-making.” The theoretical generation flowchart is shown in Figure 3. Due to space limitations, only part of the original text conceptualization is presented. The bolded text in the figure represents the specific encoding process.

Figure 3.

Theoretical generation flowchart.

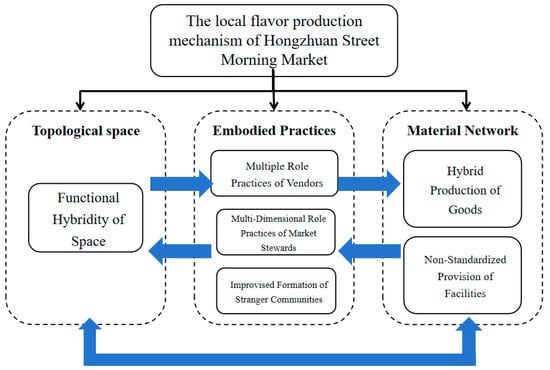

“Postmodern place-making” refers to dynamically and resiliently creating and maintaining local uniqueness, rather than aiming to pursue neatness, unity and efficient order, by embracing and utilizing the mixture of tradition and modernity, superficial chaos, and spontaneous activities. Within the “Postmodern Placeness Production” framework, three constitutive dimensions are evident: “topological space–embodied practice–material networks.” The “Postmodern Placeness Production” framework is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Theoretical framework of “Postmodern Place-Making”.

“Topological space” refers to an integrated whole where multiple social relations spontaneously intermingle, overlap, permeate, and transform while maintaining stability amid dynamics. Such a space does not emerge from functional planning or boundary design; instead, it exhibits functional redundancy and a flexible, random order. This definition derives from Henri Lefebvre’s and Jane Jacobs’ judgments on urban space. Lefebvre proposed that the core logic of spatial production lies in the triadic dialectical unity of “perceived space–representational spaces–spatial practice.” He advocated the construction of a coordinated and shareable urban space rooted in residents’ daily lives, emphasizing the dynamic and practical nature of space as a social product [40,41,42,43]. Jane Jacobs further identified “urban vitality” as a crucial cornerstone of sustainable urban development [44]. She specifically pointed out that the primary need for mixed uses and small-block layouts, the preservation of historic buildings, and the necessity of crowd aggregation are all key elements in maintaining urban vitality [45,46]. This aligns with the focus of “topology” in mathematics on “dynamic stability preserved under continuous deformation,” facilitating the description of complex spatial structures in urban neighborhoods where multiple elements intermingle and flow while presenting a unified order of dynamic stability.

“Embodied practice” refers to the agentic subjects who participate in place-making through embodied practices. Using the body as the vehicle, they generate local knowledge through sensorial actions and spontaneous interactions that transcend prescribed roles. Embodiment originates from the critique of mind–body dualism, asserting that bodily experience constitutes the fundamental source of cognition and mentality [47]. Other scholars have generally emphasized that humans are subjectively embodied in a real, interactive, and dynamic bodily process, rather than being statically confined to a physical body [48], thereby bringing “living human beings” into research across various fields [49]. Among these scholars, Chris Shilling argues that, on one hand, the body is a generative element of social life, and the embodied subject possesses a certain intentional capacity to influence the flow of daily life. On the other hand, the body is an entity with both materiality and sociality, capable of shaping society while also being shaped by society [50]. Following this theoretical tradition, this paper employs the dimension of “embodied practice” to demonstrate the dynamic process through which actors actively engage in space, experience space, and are shaped by space.

“Material networks” encompass material elements such as goods, facilities, and the climate. These elements are not merely passive backdrops; rather, they actively participate in the network of place meaning through cultural experience and practices of use. This dimension follows the Actor–Network Theory (ANT) proposed by Bruno Latour and others, which argues that non-human material entities themselves possess a certain degree of agency and dynamism [51]. Together with human actors, these non-human entities form a social action system and network, thereby shaping the patterns of our lives [52]. Tim Ingold’s “dwelling perspective” posits that the “environment” is no longer merely a separable surrounding entity that actors confront; instead, it continuously enters into actors’ activities through its characteristics and affordances, and mutually permeates and shapes actors. In this sense, actors and their environment constitute an indivisible whole, undergoing development together through interaction [53,54,55]. It should be noted that the “material network” dimension proposed in this paper employs the concept of “non-human actors” at a metaphorical level. Its purpose is to further demonstrate the dynamic co-construction between diverse human roles and material entities in the morning market, rather than being a strict application of the Actor–Network Theory.

This empirically derived “Postmodern Placeness Production” model is characterized by its core mechanism of hybridity logic. The “hybrid logic” referred to in this paper is a way of thinking that neither deliberately creates differentiation nor maintains order through coercive measures. Instead, it fully respects the overlapping nature of things’ functions, the spontaneity of actions, and the potential for self-organization. Existing research on place-making often falls into an ordered worship of “participation” and “interaction,” positing that standardized interactive behaviors and the accumulation of participatory opportunities suffice to construct a tourist community. This efficiency-driven logic is, in essence, a continuation of the “functionalist planning” critiqued by Jane Jacobs. Contemporary tourism planning strategies—such as adding interactive spaces and designing immersive experiences—ostensibly emphasize increased participation [46]. Yet they fundamentally remain within an efficiency-oriented, orderist framework. Interaction is presupposed as a standardized, replicable module, with the goal of achieving “predictable tourist experiences” through controlled variables. Harbin morning market, however, disrupts this paradigm through functional hybridity and surface-level disorder: vendors and customers, through various unplanned practices, form a spontaneously self-organized dynamic equilibrium among actors. This hybridity validates Jacobs’ assertion that urban diversity stems from the “continuous modification of countless unplanned actions” [46]. The market’s “disordered redundancies”—such as oil-stained floor tiles, tacit rules formed through competition for space, and colorful makeshift banners—precisely shape place distinctiveness by resisting homogenization. While mainstream practices obsessively eliminate incongruous elements, Harbin morning market successfully leverages this “disorder” and chaos. It demonstrates that authentic community-building lies not merely in increasing interaction and participation opportunities but in unleashing the self-organizing potential catalyzed by intersecting disorder, thereby developing the system’s inherent capacity for elastic adaptation.

While revealing the mechanism of place attachment production in morning markets, this framework also provides practical guidance for constructing sustainable “third spaces” in urban areas. Edward Soja argues that the “third space” integrates the real and the imaginary, the material and the spiritual, the subject and the object, the abstract and the concrete, the knowable and the unknowable, and the repetitive and the differential, thus featuring complexity and openness [56]. Ray Oldenburg defines the “third space” as an open, accessible-to-all public gathering place for leisure and recreation beyond home and work environments, and it serves as an informal space for free social interaction [57]. This study draws on the spatial potential of this concept—specifically its ability to stimulate residents’ social interaction, establish connections, and foster friendships and a sense of belonging [58]—and relies on the hybrid logic of sense of place production to offer insights for the further development of similar urban third spaces.

3.6. Theoretical Saturation Test

Glaser and Strauss did not explicitly propose indicators for judging theoretical saturation, but the fundamental principle is clear: when new data can no longer provide additional information and insights, this indicates that the themes currently generated are sufficient to cover the mechanisms and processes involved in the study, and the connections between the themes have also been fully clarified. To demonstrate the transparency and rigor of the research methodology, this paper takes the core category of “Multiple Role Practices of Vendors” as an example to present the generation trajectory of specific concepts within each subordinate category during the open coding and axial coding processes. At the same time, this paper presents text segments related to vendors from the 11th to 13th interviews, thereby enabling a more intuitive judgment of theoretical saturation. The concept generation memo is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

The concept generation memo of the “Multiple Role Practices of Vendors”.

FT-11: He cut off a small piece of Leba (a type of fermented food) for me and continued chatting: “Back in the day, there were many Russians in Harbin. This leba is an old local flavor here. My grandfather used to be an apprentice in a bakery run by Russians, and this skill has been passed down for three generations.” Later, when I bought two, he specially wrapped them in kraft paper, drew a small snowflake on it, and said, “This is a symbol of Harbin—it’ll look nice even if you take it back as a souvenir.”

FT-12: When I travel to other places, buying things is just a matter of asking the price, paying, and leaving. But here, I can chat with vendors, learn to make local delicacies, and even get to know other vendors through them—it feels especially welcoming. It’s like … I remember a vendor selling red sausage said, “What we sell at this morning market isn’t just goods, but the warmth and humanity of Harbin.” I think that’s absolutely right—it’s precisely because of these vendors that I feel, “This is the real Harbin.”

FT-13: I asked the sugar painting master, “Where can I buy authentic Northeast frozen pears?” He directly pointed to a stall diagonally opposite and said, “Go find Uncle Zhang. He uses autumn pears to make them—they’re sweeter than my sugar.” When I went over to buy some, Uncle Zhang also said, “Did Master Li tell you to come here? His sugar paintings are really famous at this morning market.” It didn’t feel like they were competing for business; instead, they were like a family, helping each other out.

Only a portion of the interview transcripts are presented here, yet they are representative of the interviewees’ overall statements. Theoretical saturation testing was conducted using the reserved interview texts, and no new concepts or categories were identified. Therefore, it can be concluded that the conceptual model of this study achieves theoretical saturation.

4. Results

4.1. The Topological Space in the Morning Market

In the “Postmodern Place-Making” model, spatial practices construct the material foundation of place uniqueness through the multi-layered superposition of physical environments. The functional redundancy of the morning market manifests in the composite nature of spatial uses: it serves as a venue for ingredient trading, a stage for folk cultural performances, and a repository of urban memory. The construction of flexible order maintains internal rules beneath surface-level disorder through dynamic equilibrium mechanisms, endowing the space with adaptable and orderly characteristics. Urban spatial embeddedness tightly connects the morning market to the broader urban context, making it an organic component of the city. Spatial meaning production, building on the above, stimulates tourists to perceive the vitality of the space through immersive experiences of festive ambiance, lively novelty, and urban entrepreneurial spirit. These elements are not isolated but mutually permeate and reinforce one another. The richness of functional hybridity and the dynamism of flexible order provide raw materials and frameworks for meaning production, while urban embeddedness imbues the space with urban depth and belonging. Together, they act upon tourists, enabling them to deeply perceive a unique and irreplicable sense of place during their engagement with the market.

FT-05: Harbin’s architectural landscape strikingly blends Russian influences with East-meets-West fusion. En route to the morning market, I passed an opulent music hall with gilded decorations, then abruptly transitioned to cobblestone streets of the market itself. This architectural juxtaposition feels intentional yet organic. The weathered bluestone bricks underfoot, preserved rather than replaced, whisper stories of history through their timeworn surfaces.

FT-06: Everyone seemed so positive and energetic. It gave me a special kind of experience—even with Harbin facing issues like population outflow and aging, Hongzhuan Street Morning Market left me feeling its uplifting, warm, and lively spirit. It felt so full of life and vitality—unlike the morning market I visited in Quzhou, where the vendors seemed somewhat listless.

Fieldwork Notes, 5 January 2025: This is a grilled sausage stall at Hongzhuan Street Morning Market. Behind the stall stands a typical Russian-style building, with elaborate reliefs decorating the window edges and a domed roof rising in the distance—an imposing and solemn sight rarely seen in other parts of China. At the base of the building, woks, grills, and steaming sausages fill the air with aroma. A red banner above the stall reads, “Welcome princesses and princes from across the nation to Hongzhuan Street Morning Market”—a phrase that embodies the Northeasterners’ sense of humor, as they seek to make visitors feel at home through such warm words. A loudspeaker at the stall’s edge repeats this message in the local dialect, often drawing chuckles from tourists. A long line has formed of customers waiting to buy, while two people in red waistcoats frequently interact with the crowd. These red waistcoats, once a nationally renowned characteristic costume of Heilongjiang Province, have evolved into a cultural symbol. Even locals rarely wear them in daily life, reserving them instead for casual at-home use. Here, solemnity mingles with leisure, humor with warmth, and the crisp cold air with the bustling energy of the scene. The Morning market streetscape is shown in Figure 5. Figure 5. Morning market streetscape.

Figure 5. Morning market streetscape.

When tourists engage with this spatial system, they undergo an embodied transformation of meaning. Functional hybridity creates dense sensory stimulation, flexible order guides autonomous behavioral adaptation, and urban embeddedness provides a cultural decoding reference. Together, they complete the embodied conversion of symbolic meaning through fluid experiences. The sense of place arising from such spatial practices is neither a purely material attribute nor a unidirectional emotional projection. Instead, it is a dynamic relational network continuously generated through the interaction of multiple spatial elements. Its essence lies in the reshaping of tourists’ cognitive schemas via the self-organizing system.

4.2. The Embodied Practices of Human Actors

Within the human actor dimension, vendors and market stewards dissolve the singular positioning of actors in traditional market contexts through hybrid role practices. Simultaneously, tourists undergo multi-dimensional meaning-capturing processes within the ritualistic field co-created by vendors, market stewards, and other actors. The non-programmed interaction networks they construct—such as using affectionate terms to build rapport, transparent price negotiations, and meticulous care—infuse warmth into transactional processes, fostering unique emotional bonds.

On one hand, vendors, as economic traders, cultural translators, and relational mediators, transform commercial activities into stages for ethical place-making through their hybrid roles. Their non-programmed interaction networks align with Jane Jacobs’ “street ballet” theory: seemingly disordered competition reflects the market ecosystem’s self-regulatory mechanisms. Non-standardized promotional strategies further amplify the market’s uniqueness, constructing a dynamically balanced market ecology that dismantles standardized commercial logic. Meanwhile, role hybridity enables the embodied performance of local knowledge. Vendors, as “imperfect information providers,” construct an anti-standardized “authenticity” through personalized hospitality and the transmission of local knowledge. Their bodies become mobile carriers of local chronicles, converting physical space into legible meaning systems through unscripted cultural outputs.

On the other hand, market stewards, as symbols of “order,” participate in place-based ritual performances, softening the tension between state authority and grassroot spontaneity. Vendors and market stewards collectively act as performers of place-making. Despite their structural opposition, they enact shared cultural practices within the unique field of the morning market. These practices transform the market into a liminal “anti-structure” space [59], where tourists shed their “insider–outsider” identities and enter an egalitarian, ambiguous transitional state. This state incubates new social relations and becomes a vital source of the sense of place. This is exemplified by the following statements of one interviewee:

FT-06: When buying sticky rice dumplings, I nervously asked the vendor, “Are these sweet?” The auntie instantly reassured me with maternal warmth: “Don’t fret, girl! These aren’t sweet at all. Want even less sweetness? I’ll wrap you a fresh batch right now!” Her enthusiasm embodied that quintessential Northeastern hospitality, turning a simple transaction into heartwarming cultural exchange.

FT-09: These market stewards are nothing like the “stern stewards” in people’s impressions. They are more like old neighbors who have lived here for years—knowing every vendor by name and exactly what tourists might need. Instead of enforcing rules to control people, they exude the warmth of Harbin through their way of speaking, their readiness to help, and even the perfect measure of their jokes.

The improvised formation of stranger communities reveals the dissolution of role boundaries in the market. Through non-contractual mutual aid, bodily co-presence activates emotional relational networks. When ad hoc alliances form during conflicts, the self-organizing wisdom beneath apparent disorder becomes evident. Collective memory production allows individual experiences to intertextually overlap through cultural mediation, enabling tourists to dialectically reconcile regional differences and place identity, ultimately synthesizing fragmented interactions into holistic cultural recognition.

Tourists’ interactions, mediated by the shared space of the morning market, position them as both service recipients and cultural participants. The joy of shared meals, resonance with influencing interactions, and fluid exchanges among strangers foster warmth and belonging in an unfamiliar environment. In collective memory production, the market’s festive atmosphere intertwines with tourists’ childhood nostalgia, evoking deep-seated emotions and forging unique place identity. The spontaneous care network exemplifies human warmth in the market, where acts of kindness dissolve urban alienation, constructing a vibrant community of strangers. Through participation, tourists profoundly internalize the market’s unique sense of place.

FT-02: When there were no seats, I asked the vendor, ‘How can I eat here?’ He said, ‘Wait, brother—I’ll find you a spot.’ Another tourist, finishing their meal, offered me their seat. Such small gestures made me feel the human warmth of this place.

FT-01: For instance, when I went to buy rice cakes over there, you could actually try pounding them yourself. Yeah, so I went over and gave it a try. The experience felt really unique, because rice cake pounding is probably a tradition or custom from nearby Korean ethnic culture. If I were in the south, I definitely wouldn’t have encountered anything like freshly pounded rice cakes. So it felt very experiential—I got to participate in it.

The role hybridity of three actor groups (vendors, market stewards, strangers) collectively constitutes the dynamic mechanism of place-making. Vendors and market stewards weave place meaning through functional overlaps, while strangers activate experiential dimensions through identity fluidity. Here, disorder becomes the generative source of place uniqueness. In this dynamic interplay, surface-level chaos transforms into systemic resilience, with role redundancy and identity fluidity co-constructing a “homogenization-resistant locality”.

4.3. The Material Network in the Morning Market

In the non-human actor dimension, the hybrid production of goods constructs a materialized representation system of local culture. The diversity of goods facilitates cross-cultural fusion, with their heterogeneity achieving cultural translation through symbolic encoding. When production processes are opened to tourist participation, physical consumption evolves into embodied practice, elevating goods into carriers of collective memory and place identity. This hybrid production essentially stages place uniqueness through the polyphonic narratives of commodity symbols, enabling tourists to reconstruct local cultural DNA.

Through tourist engagement, goods with hybrid traits deeply contribute to place-making. Their diversity reflects inclusive multiculturalism, satisfying varied preferences and showcasing the richness of local culture. The symbolic meanings of goods further amplify this sense of place. When selecting goods, tourists transcend materiality to touch the emotional core of local culture. Unplanned consumer behaviors transform consumption into deep cultural interaction, where goods act as cultural mediators guiding tourists to perceive place uniqueness.

FT-04: Visiting the morning market truly unveils Harbin’s culinary DNA. Beyond the expected Northeastern staples, it’s a living cultural mosaic—Russian influences manifest in da lieba (sourdough bread) stalls, Korean rice cake artisans pound rhythms into the frosty air, while universal Chinese breakfast classics like fried dough sticks anchor the scene. This edible diversity mirrors the city’s historical crossroads identity. Even handicraft vendors contribute to the narrative, their intricate paper-cuts and birch bark carvings not mere souvenirs, but testaments to locals’ philosophy: life’s richness blooms through everyday artistry.

The non-standardized provision of facilities reveals the self-organizing logic of material environments. Official and grassroot facilities achieve a dynamic balance between institutional and spontaneous systems. Spatial practices beneath apparent disorder—rational vendor layouts and regular crowd flow—follow implicit rules derived from local experience. When facilities intervene in tourist perception as “agentic mediators,” their hybrid traits become tangible evidence of place vitality. The absence of standardization paradoxically strengthens the cognitive construction of authenticity.

Tourists perceive “controlled chaos” in hybrid facilities. Non-standardized supply breaks the monotony of uniform infrastructure, offering convenient and culturally distinctive experiences. Hybrid signage (official themes, dialect slogans, informal banners) creates unique visual cultural encounters. Self-organization in disorder reflects latent order: vendor layouts, though spontaneous, follow tacit spatial norms, forming the market’s unique spatial character. These facility-related practices immerse tourists in a vibrant, place-specific ambiance.

FT-06: The stall signs themselves were cultural artifacts—“Gaga Xiang Egg Burger”, “Authentic Harbin Sausage—Fake? We’ll Pay You 10,000×!”, and the pièce de résistance: “Northeast Na Gada Mega Rice Wrap”. These linguistic gems transformed storefronts into living dictionaries of Northeastern vernacular, where every character vibrated with unapologetic local pride.

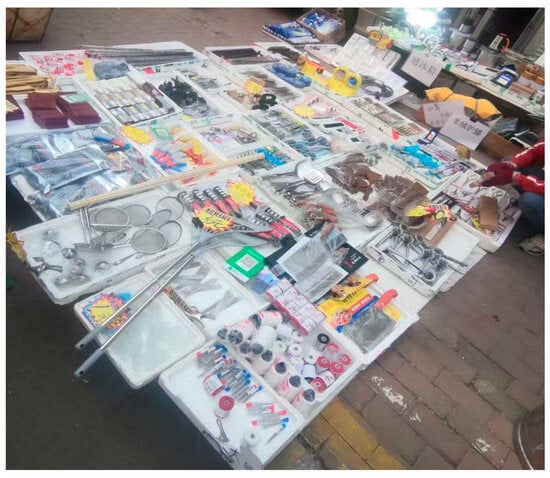

Fieldwork Notes, 10 January 2025: On the flagstones of the early morning, nuts and spices in bamboo baskets and plastic basins spread out in a seemingly unruly “labyrinth of flavors”—amber-colored roasted peanuts nestle next to dark brown cassia bark, snow-white sunflower seeds sit beside crimson star anise, and price tags scrawled in chalk by vendors are crookedly stuck in the piles of goods. The nuts and spices sold at the morning market are shown in Figure 6. Yet they beckon tourists’ fingertips to flit back and forth between different heaps. An aunt wearing a woolen hat squats in front of the roasted nuts stall, burying her face in the fragrant steam, and calls out to her companion in Northeastern dialect: “Smell these sunflower seeds! They taste just like the ones at the alley corner when we were kids!” At a nearby used goods stall not far away, dented aluminum lunch boxes, faded old flashlights, and tool pliers wrapped in tape are jumbled together on a plastic sheet. Several tourists and the vendor chat animatedly, ranging from “prices back in the day” to “craftsmanship nowadays”, and the distance between strangers quietly fades away amid these haphazardly placed old items. These small commodities, in their messy arrangement, make tourists willingly bend down and lean forward, and in the process of selecting, inquiring, and sharing, they become part of the morning market space. The used items and sundries sold in the morning market are shown in Figure 7. Figure 6. Nuts and spices sold in the morning market.

Figure 6. Nuts and spices sold in the morning market. Figure 7. Used items and sundries sold in the morning market.

Figure 7. Used items and sundries sold in the morning market.

The synergy between facilities and goods constitutes the non-human actor dimension of place-making. Non-standardized facilities provide the material basis for cultural translation, while symbolically hybrid goods enrich facility semantics. As tourists navigate greasy tiles and layered banners, they decode place uniqueness through material hybridity. An authentic sense of place emerges not from meticulously designed scripts but from the cross-empowerment of material performances and human practices.

5. Conclusions

This study constructs a theoretical framework of “Postmodern Place-Making” through grounded theory, revealing the critical role of spontaneous order among diverse actors in the production of place meaning within the morning market. The key findings are as follows:

The generation of a sense of place does not rely on meticulously designed, ordered interactions but is closely associated with contexts characterized by functional redundancy and self-organizing potential within apparent disorder. In the triadic model, each dimension contains abundant hybrid and redundant elements. However, through interactions with tourists, these elements construct legible meaning networks that foster community formation. Collectively, they demonstrate that place uniqueness is rooted in hybrid systems resistant to homogenization, rather than in formulaic spatial planning or interaction design. This research finding aligns with conclusions from the existing literature on topics such as the therapeutic function of “vitality and warmth” in tourist destinations, the spatial construction of “night culture” in Guangdong Province, and the sustainable development of traditional village spaces in Guizhou Province [60,61,62]. However, this study goes a step further by exploring the interactive relationships among the diverse actors that constitute such disordered spaces and their impacts on tourist experiences—rather than merely stopping at verifying the effectiveness of disorder and hybridity.

This study transcends the traditional “human–place” dualism in tourism sociology, uncovering the co-productive synergy of space, human actors, and non-human actors in generating place meaning through dynamic interactions. Spatial practices provide the material foundation and cultural context for human interactions; the performance of humans in their roles animates spaces and non-human elements with social vitality; and the symbolic encoding of non-human elements reciprocally enriches the depth of interpersonal interactions. This triadic cross-empowerment elevates tourists’ experiences from fragmented perceptions to holistic cultural identity. Scholars such as Wang Qiang and Yuan Chao have conducted in-depth analyses of the role of materials in translating the emotional atmosphere and complex interpersonal relationships within tourist spaces, and their findings resonate with this study. Building on this foundation, this study further demonstrates how the translation process of these materials acts upon tourists’ bodies and senses to shape their experiences. Meanwhile, we not only recognize the agency of materials in tourist spaces but also understand this agency within the context of local culture [63,64,65].

Different from the traditional image of tourists as one-sided “gazers,” this study details that tourists’ roles undergo a continuous transformation from onlookers to embodied participants. As tourists move from spatial wandering in the initial stage to embodied integration into the culturally symbolic space constructed by materials and the social relational network built by vendors and strangers, a sense of place is generated spontaneously and unreflectively in the process of continuous dialog between the body and space.

On this basis, this study aims to put forward a series of practical recommendations to assist operators and market stewards in further exploring the potential of disorderliness in the process of spatial production. This, in turn, will help to facilitate the shift in their fundamental strategies from “functional optimization” to “mediatic activation”—that is, to move away from the traditional approach of unilaterally emphasizing the optimization of interactive functions in tourist attractions, which has gradually led them into the predicament of functional convergence and formal standardization, and instead turn to the full utilization of diverse media such as bodies, materials, and spaces within urban neighborhoods. The specific recommendations are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Recommendations for construction of urban street space.

By foregrounding relational materiality, embodied multiplicity, and self-organizing hybridity, this study redefines place-making as a dynamic, co-creative process where chaos and order, humans and non-humans, and memory and matter converge to forge irreplicable localities. Despite these theoretical and practical contributions, this study acknowledges several limitations that warrant consideration. First, the sampling strategy focused exclusively on tourists, potentially overlooking the equally critical perspectives of local residents, vendors, and market stewards, whose lived experiences and practices are fundamental to the social construction of the morning market. Second, while theoretical saturation was achieved with the initial sample and validated with additional participants, the relatively small size and the unique “viral” context of the case may influence the transferability of the findings to other, less prominent local markets. Third, the data collection process conducted solely within the winter season might introduce a seasonal bias, as visitor motivations, market dynamics, and spatial practices could vary significantly during other times of the year. Future research would benefit from longitudinal designs that track the evolution of place-making across different seasons, incorporate a more diverse range of actor perspectives, and extend the inquiry to various types of markets to refine and test the proposed “Postmodern Place-Making” framework in broader contexts.

Author Contributions

Validation, X.C.; Formal analysis, Y.G. and Z.L.; Data curation, Y.G.; Writing—original draft, Y.G.; Writing—review & editing, Z.L.; Visualization, Z.L.; Supervision, X.C.; Funding acquisition, X.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities grant number HIT.HSS.WG202505; Annual Project of Heilongjiang Provincial Philosophy and Social Sciences Research Program grant number 24SHC010; National Social Science Fund of China grant number 21CSH002; China Postdoctoral Science Foundation grant number 2022M710036.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was received ethical approval from Harbin Institute of Technology’s Institutional Review Board (Ethics Approval Number: HIT-2025087, data of approval 4 January 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

All participants in this study provided their informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Department of Culture and Tourism of Heilongjiang Province. Harbin Received 90.357 Million Tourists During the 2024–2025 Ice and Snow Season. 2025. Available online: https://wlt.hlj.gov.cn/wlt/c114212/202503/c00_31817830.shtml (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Heilongjiang Provincial Department of Culture and Tourism. Daily Passenger Flow at Mao’ershan Ski Resort Exceeded 3000 in February. Available online: https://wlt.hlj.gov.cn/wlt/c114212/202502/c00_31813483.shtml (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Harbin Municipal People’s Government. Out-Of-Town Tourists Love the “Yanhuoqi” (Lively Atmosphere) of Ice City the Most. 2025. Available online: https://www.harbin.gov.cn/haerbin/c104696/202501/c01_1036652.shtml (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Harbin Municipal People’s Government. Implementation Rules for Several Financial Policy Measures to Boost Development Confidence and Promote the Accelerated Recovery and Overall Improvement of the City’s Economy. 2024. Available online: https://www.harbin.gov.cn/haerbin/c108433/202401/c01_960647.shtml (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- Harbin Municipal People’s Government. Ten Measures for Utilizing Urban Public Space to Invigorate Circulation and Promote Consumption in Harbin. 2020. Available online: https://www.harbin.gov.cn/haerbin/c104546/202007/c01_177199.shtml (accessed on 7 July 2020).

- Harbin News Network. Hongzhuan Street Morning Market: Where the ‘Yanhuo’ Rises, New Chapters of Traffic Begin. 2025. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1820414571761831797&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Sun, J.X.; Zhang, L.Y. Co-created place: The reconstruction of ice-snow tourism destinations and the revitalization effect of Northeast China. Geogr. Res. 2025, 44, 1327–1341. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.S. The construction of attractions, the creation of authenticity, and the development of emotions in the regional tourism boom: An investigation based on Heilongjiang Province and Harbin City. Heilongjiang Soc. Sci. 2025, 1, 50–62. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, X. Local Reconstruction and Cultural Interpretation of the Urban Cultural Tourism Boom. Tour. Trib. 2025, 40, 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J.C. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed; Social Sciences Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2004. Original work published 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y.; Zhou, L.; Xiao, H. Tourists’ “ambivalence” towards modernity: A discussion based on linear and cyclical historical perspectives. Tour. Trib. 2024, 39, 132–140. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Z. Modernity and Ambivalence; The Commercial Press: Shanghai, China, 2003; pp. 3–27. Original work published 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Zolberg, V.L. Review of the book Culture and power: The sociology of Pierre Bourdieu, by D. Swartz. Soc. Forces 1999, 77, 1232–1234. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Xue, D. Formalization of the informal economy: Spatial governance models and effects of street vending in Guangzhou. Urban Dev. Stud. 2015, 22, 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z. “Marginal governance” of city governments: A comparative study of street vendor supervision policies. Public Adm. Rev. 2012, 5, 30–58+179–180. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo, C.; Guo, C. High modernism in national governance: Malpractices and remedies. Henan Soc. Sci. 2015, 23, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R. Opportunities and challenges brought by the development of modern science and technology to the tourism industry. J. Jiangxi Sci. Technol. Norm. Univ. 2008, 6, 36–38. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Li, Y.; Ning, Z.; Chen, W. The concept and connotation of smart tourism from the perspective of rational choice. Tour. Hosp. Prospect. 2021, 5, 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kamete, A.Y. Missing the point? Urban planning and the normalization of ‘pathological’ spaces in southern Africa. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2013, 38, 639–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Xiong, Z. Research on homogenization problems and differentiation strategies of cultural tourism characteristic towns: Case studies of Anren Ancient Town and Luodai Ancient Town in Sichuan. J. Yangtze Norm. Univ. 2019, 35, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W. From landscape gaze to lifestyle: The postmodern turn in tourism. J. Sichuan Univ. Arts Sci. 2013, 23, 142–146. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, D.; Huang, Y. Research on the destination image of Lijiang Ancient Town: Content analysis based on online texts. Tour. Trib. 2019, 34, 80–89. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, Y.-F. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience; China Renmin University Press: Beijing, China, 2017. Original work published 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Relph, E. Place and Placelessness; The Commercial Press: Shanghai, China, 2021. Original work published 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, C. The Interpretation of Cultures; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 8–30. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, S.; Zhou, S. The role of text in constructing tourists’ sense of place: An analysis based on travel notes of Qufu. Geogr. Geo-Inf. Sci. 2013, 29, 100–104. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, C.; Tao, H.; Liu, J.; Lü, N.; Zhang, X.; Xue, T. Digital place-making in tourist resorts from the perspective of media geography: A case study of Aranya in Qinhuangdao. Tour. Trib. 2024, 39, 151–162. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, Y. Discussion on the influence of mass media on shaping local tourism image. Frontline 2015, 7, 118–119. [Google Scholar]

- Shaykh-Baygloo, R. Foreign tourists’ experience: The tri-partite relationships among sense of place toward destination city, tourism attractions and tourists’ overall satisfaction—Evidence from Shiraz, Iran. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y. Cultivating Sense of Place: A New Path for the Development of Red Sports Tourism Industry in Jiangxi Province. Master’s Thesis, Gannan Normal University, Ganzhou, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, W.; Zhang, J.; Luo, H.; Yang, X.; Li, D. Characteristics of tourists’ sense of place in a natural sightseeing destination: A case study of Jiuzhaigou. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2007, 62, 599–608. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, L.; Gao, Q.; Chen, X. Place restructuring in traditional rural tourism destinations from the perspective of tourists’ embodied experience: A case study of Wuyuan. Tour. Trib. 2021, 36, 69–79. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Xiang, L. Research on the place-making of rural homestays in traditional villages from an embodied perspective. In Proceedings of the 2023 China Urban Planning Annual Conference (16 Rural Planning) China Urban Planning Society, People’s City, Planning Empowerment, Tianjin, China, 28 June–2 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, Y. Research on rural tourism experience from an embodied perspective: A case study of Yuanjia Village, Shaanxi. J. Xianyang Norm. Univ. 2022, 37, 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Hu, X.; Ai, S. Identity, mobility and power: Spatial practices of street vendors. Hum. Geogr. 2020, 35, 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, C.; Wang, F. Street vendors and the city. Huazhong Archit. 2008, 26, 106–108. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Suo, Y. Mobile vendors and popular culture in modern Chinese cities. Gansu Soc. Sci. 2012, 176, 164–167. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z. Vitality and quality: The resilient production of urban vendor space and reflections on its governance. Soc. Sci. Yunnan 2021, 188, 139–146. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G. The Grounded Theory Perspective: Conceptualization Contrasted with Description; Sociology Press: Mill Valley, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y. Between space, relational sociology, and Lefebvre’s critique of modernity: An understanding of relational spatiality in trans-actional perspective. Sociol. Forum 2024, 40, 342–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Räcker, T.; Geiger, D.; Seidl, D. From coordinating in space to coordinating through space: A spatial perspective on coordinating. Organ. Theory 2024, 5, 26317877241270124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvr, H. The Production of Space; Blackwell Publisher: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1991; pp. 38–39. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, J. How Can We Share Space? Ontologies of Spatial Pluralism in Lefebvre, Butler, and Massey. Space Cult. 2019, 25, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, O.; Lee, S. Jane Jacobs’s urban vitality focusing on three-facet criteria and its confluence with urban physical complexity. Cities 2024, 155, 105446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal Domper, N.; Hoyos-Bucheli, G.; Benages Albert, M. Jane Jacobs’s Criteria for Urban Vitality: A Geospatial Analysis of Morphological Conditions in Quito, Ecuador. Sustainability 2024, 15, 8597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1961; pp. 3+29–54. [Google Scholar]

- Merleau-Ponty, M. Phenomenology of Perception; Taylor and Francis e-Library: Abingdon, UK, 2005; p. 43. [Google Scholar]

- Waskul, D.D.; Vannini, P. Body/Embodiment Symbolic Interaction and the Sociology of the Body; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 2006; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Xuan, C.Q.; Feng, B.Y. The research dilemma and theoretical breakthrough of “embodiment”. Nankai J. (Philos. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 114–125. [Google Scholar]

- Shilling, C. Physical Capital and Situated Action:A New Direction Ore Corpo-Real Sociology. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2004, 25, 1473–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latour, B. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network Theory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 63–86. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.Y. Garbage as a Dynamic Entity: A Study of Waste from the Perspective of Materiality. Sociol. Stud. 2021, 36, 204–224+230. [Google Scholar]

- Tim, I. From science to art and back again: The pendulum of an anthropologis. Anuac 2016, 5, 5–23. [Google Scholar]

- Tim, I. One world anthropology. J. Ethnogr. Theory 2018, 8, 158–171. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, M.F. An Attempt to Transcend Nature and Humanity: On Tim Ingold’s “Dwelling Perspective”. J. Qinghai Minzu Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2017, 43, 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Soja, E.W. Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-lmagined Places; Blackwell Publisher: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1996; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Oldenburg, R. The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community; DA CAPO Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1989; pp. 44–62. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. The Street as a Stage: A Study on the Construction of the “Third Space” in Youth Street Music Practice. China Youth Study 2025, 8, 14–22+40. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, V. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure; Jianbo, H.; Boyun, L., Translators; China Renmin University Press: Beijing, China, 2006. Original work published 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.C.; Wu, X.N. A study on the therapeutic mechanism of “vitality and warmth” in tourist destinations: From the perspective of rhythm analysis. Tour. Trib. 2025, 40, 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Zhong, W.Q. A study on the formation mechanism of locality in urban night cultural and tourism consumption clusters: A case study of Foshan City, Guangdong Province. World Reg. Stud. 2025, 34, 178–194. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Y.M.; Ma, Y.Q. Research on the protection and development of traditional villages based on local knowledge: A case study of Xijiang Qianhu Miao Village. Archit. Cult. 2025, 6, 233–236. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.F.; Chen, H.Y. Re-examining tourist experience: From the perspective of assemblage theory. Chin. Ecotourism 2025, 15, 219–229. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, C.; Xu, L.Z. Reconsidering tourist landscapes from the actor-network theory perspective: Theoretical origins, conceptual connotations, and research approaches. Hum. Geogr. 2025, 40, 175–183. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, X.M.; Li, Y. Mobile place: The spatial construction of Xinduqiao inns led by tourism operators. Hum. Geogr. 2025, 40, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).