Abstract

Rural landscapes play a key role in preserving ecological processes, cultural identity, and socio-economic well-being, yet these areas often face challenges such as land degradation, water scarcity, and an inadequate road network. A sustainable approach to rural landscape and tourism planning is essential for enhancing both environmental resilience and socio-economic vitality in areas facing degradation and global change. This study aims to develop and validate an integrated methodological workflow that combines Landscape Character Assessment (LCA), ECOVAST guidelines, SWOT analysis, and open-source GIS techniques, complemented by a bottom-up approach of spontaneous fruition mapped through Wikiloc heatmaps. The framework was applied to a case study in Paternò, Eastern Sicily, Italy—a territory distinguished by its key local values such as Calanchi formations, proximity to Mount Etna, and cultural heritage. Through this application, eight distinct Landscape Units (LUs) were delineated, and key strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats for sustainable development were identified. Using open-access data and a survey-free protocol, this approach facilitates detailed landscape assessment without extensive fieldwork. The methodology is readily transferable to other rural Italian and Mediterranean contexts, providing practical guidance for researchers, planners, and stakeholders engaged in sustainable tourism development and landscape management.

1. Introduction

Landscape includes the natural and cultural elements of an environment, while landscape character refers to the distinct, recognizable patterns formed through the interplay of human activities and natural processes. These characters reveal specific qualities and values present in today’s environment, offering essential information to those who live in, manage, use, and appreciate the land. By definition, a landscape is an area perceived by people, whose unique character arises from the continuous interaction of natural forces and human actions. It is through this dynamic relationship that landscapes develop their varied visual, physical, and sensory attributes [1,2,3].

Rural landscapes play a crucial role in maintaining ecological processes, supporting biodiversity, and sustaining local cultural identities and economies. In the Mediterranean basin and Italy, these types of landscapes often combine high natural and cultural value with increasing fragility due to complex pressures such as climate change, soil degradation, and unsustainable agricultural practices. As highlighted by the European Landscape Convention [3], protecting and enhancing all types of landscapes—including everyday and degraded ones—is essential to promote sustainable development and improve quality of life.

In Italy, many marginal rural areas—including parts of Sicily—are facing critical challenges such as water scarcity, soil erosion, infrastructural deficits, and the risk of cultural heritage loss. At the same time, these territories offer unique opportunities for regeneration through sustainable tourism, the valorization of local resources, and innovative forms of multifunctional land use (e.g., agrivoltaics). However, effective planning in these contexts requires methodologies capable of integrating spatial data, landscape character, community practices, and strategic priorities.

The municipality of Paternò (Metropolitan City of Catania, Sicily, Italy) is an emblematic case because it exhibits typical marginal-area vulnerabilities such as water scarcity, limited electrical supply, and deficient road infrastructure. However, it also holds significant potential due to the Calanchi (clay formations carved by erosion), its proximity to Mount Etna (Europe’s highest active volcano and a UNESCO site), and its rich historical-archaeological heritage. Within the municipality, the Landscape Plan of the Metropolitan City of Catania [4] identifies five Local Landscapes: territorial units sharing ecological, perceptual, historical, cultural, and functional characteristics that define their identity. This study focuses on Local Landscape No. 16, characterized by citrus fruits and arable hills crossed by hiking and cycling routes. These were documented through heatmaps and elaborated with data downloaded from the Wikiloc Web Platform [5], which demonstrates an example of spontaneous use in a context that has still not been investigated much.

Therefore, this study aims to demonstrate how an integrated, low-cost, and open-access methodological framework can support the regeneration and sustainable development of marginal rural landscapes by combining detailed landscape analysis with strategic planning and valorization of local heritage and recreational practices.

2. Literature Review

The international recognition of landscape as a key element for the sustainable development of territory reached a turning point with the adoption of the European Landscape Convention [3] in 2000, which established the protection and enhancement of all types of landscapes, including everyday and degraded ones. Accordingly, landscape research must follow an integrated approach that considers its physical, subjective, and cultural dimensions [6] This recognition aligns with broader global agendas, particularly the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 15 “Life on Land” and SDG 11 “Sustainable Cities and Communities”) [7,8], which emphasize the urgency of tackling soil and landscape degradation driven by urbanization, intensive farming, and climate change. Such degradation signals environmental, economic, and social vulnerability, making its mitigation essential to ensure territorial resilience, biodiversity conservation, and the well-being of local communities [9]. In recent years, these challenges have become even more evident: the pandemic experience further underscored the importance of urban and peri-urban green spaces for social well-being and resilience, highlighting how access to quality landscapes contributes to health and cohesion. This awareness is fully in line with the 2030 Agenda’s Sustainable Development Goals and the ecological transition strategies of Italy’s National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR) for biodiversity enhancement and climate resilience [10]. In a context of accelerating climate change and growing anthropogenic pressures, landscape design assumes a strategic role in mitigating environmental impacts and strengthening ecosystem functions, promoting solutions for increasing biodiversity, sustainably managing resources, and enhancing collective well-being.

To operationalize these principles in concrete territorial strategies, it is essential to adopt robust methodological frameworks capable of translating the integrated vision of landscape into actionable planning tools. In this perspective, and with the aim of supporting tourism valorization and sustainable fruition of a complex landscape, this work applies the Landscape Character Assessment (LCA) procedure [11,12]. LCA allows the classification and description of distinct Landscape Units—areas characterized by a degree of homogeneity or significant affinities in their natural, cultural, and anthropic elements—thus providing the necessary basis for informed decision-making. Indeed, the evaluation of landscape character through LCA today underpins environmental protection strategies and territorial management tools, guiding regional and local spatial planning by indicating appropriate areas for urban growth, determining suitable planning scales, and informing the preparation and review of environmental assessment documentation [2]. This methodology, widely applied in European and Asian contexts [1,6,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23] and less so in southern Italy [2], was conducted following ECOVAST guidelines [24] using GIS technologies to offer a multi-layered reading based on physical, biological, anthropogenic, and perceptual factors—as in the Sicilian studies [2,25]. Furthermore, integrating a SWOT analysis—a strategic method to identify strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats to support targeted decision-making and planning—provided a strategic reading of the landscape, guiding ideas and proposals for the area’s enhancement and fruition. A similar approach was adopted in a study on the sustainable management of public historic parks [19].

This work proposes and tests, for the first time in a rural context, an integrated approach combining:

- The LCA procedure according to ECOVAST guidelines for the identification and classification of Landscape Units (LUs).

- A bottom-up approach, referring to a planning perspective that starts from the local context, involving existing resources, spontaneous practices, and stakeholder knowledge to build strategies, rather than applying a top-down approach. In this study, the bottom-up approach focused on the valorization of endogenous landscape values: Calanchi, Mount Etna, archaeological heritage, and spontaneous recreational use.

- A SWOT analysis to outline strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats, and open-source GIS techniques for territorial data processing.

The primary objective is to counteract land degradation through territorial valorization by fostering sustainable tourism development in the territory of Paternò and promoting sustainable recreational use of its landscape. The novelty lies in the joint application of established methodologies and the bottom-up approach enabled by the area’s robust and well-known endogenous characteristics. Ultimately, this study aims to develop a replicable methodology that can serve as a territorial analysis tool and a foundation for sustainable rural tourism planning.

3. Materials and Methods

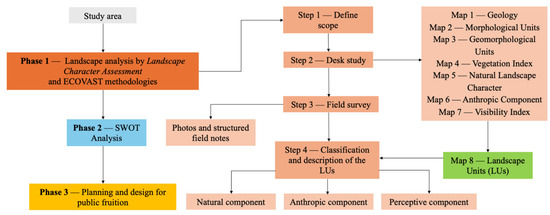

This study followed a three-phase methodology, including, for the first time, an integrated approach of consolidated methods of landscape analysis aimed at integrating the analysis of historical and contemporary territorial data with a strategic assessment of the landscape context, to develop proposals for the sustainable enhancement and public fruition of the territory.

In Phase 1, the landscape context was investigated through bibliographic and cartographic research in libraries and archives, and the current state was mapped using QGIS (LTR 3.34 Prizren) and CAD tools. During this phase, the Landscape Character Assessment procedure (LCA) [11,12] was applied following ECOVAST guidelines [24]. Several studies have applied the LCA procedure for landscape analysis: some following the ECOVAST guidelines [2], while others have applied the methodologies separately without integrating them [1,6,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,25]. Phase 2 entailed a SWOT analysis, as applied in a study on historical public park management [19], to identify internal and external factors—strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats—informing decisions on land use and enhancement interventions. Finally, Phase 3 translated the insights carried out from the precedent analysis into concrete proposals for interventions that respect and reinforce the landscape’s identity, building on the conservation guidelines for historic parks within the northern suburbs of Athens, Greece [19].

These phases can be summarized as follows:

- Landscape analysis by LCA and ECOVAST methodologies.

- SWOT analysis for strategic validation.

- Planning and design of interventions for public fruition.

This integrated sequence ensured that historical research, landscape characterization, and strategic evaluation directly informed sustainable planning proposals.

3.1. Study Area

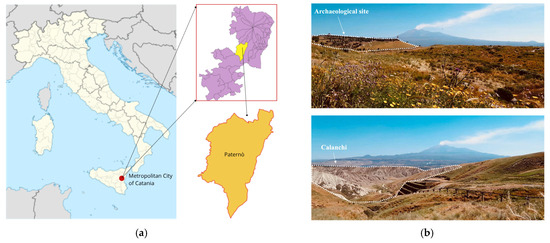

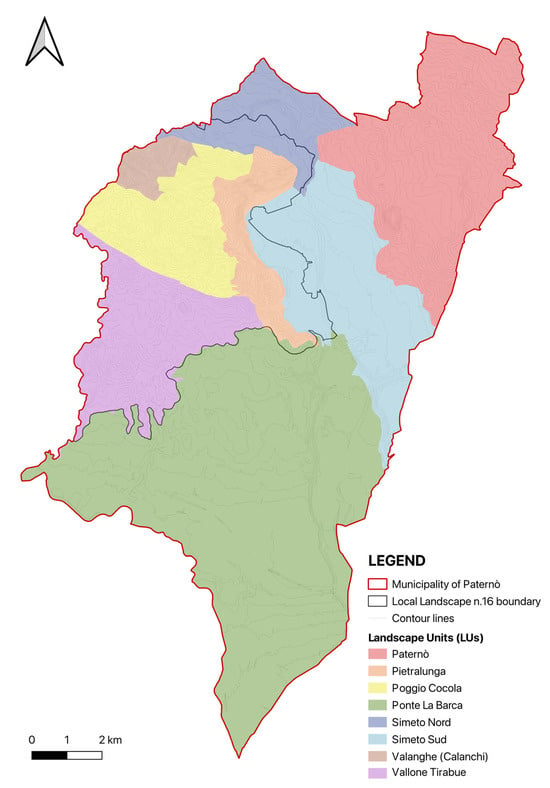

The study was conducted in the municipality of Paternò, an urban center located in the Metropolitan City of Catania, Sicily (Figure 1a), on the south-western foothills of Mount Etna (which is Europe’s highest active volcano and a UNESCO World Heritage site). The urban center lies approximately 18 km from Catania and extends over 144.68 km2.

Figure 1.

Description of the study area: (a) localization of the municipality of Paternò; (b) view of Archaeological site, Mount Etna, and Calanchi.

The choice of this area as the study focus is grounded in a bottom-up approach aimed at identifying and valorizing pre-existing landscape values and territorial dynamics. The decision is based on the recognition of a set of endogenous resources: the Calanchi (clay formations sculpted by erosion into ravines, gullies, and carved slopes), the proximity to Mount Etna, and a rich historical, archaeological, and environmental heritage (Figure 1b).

Within the municipality of Paternò, the Landscape Plan of the Metropolitan City of Catania [4] identifies several Local Landscapes (territorial units characterized by specific systems of ecological, perceptual, historical, cultural, and functional relations, between heterogeneous components that confer distinct and recognizable identities): Local Landscape No. 13 “South-West Urban Areas”, Local Landscape No. 16 “Paternò Hills Area”, Local Landscape No. 17 “Metropolitan Area—Western Territories of the Conurbation”, Local Landscape No. 21 “Plain of the Simeto, Dittaino and Gornalunga Rivers”, and Local Landscape No. 22 “Cliff of Motta Sant’Anastasia Area”.

Among these, the study focuses on Local Landscape No. 16, characterized by rolling hills planted with citrus and arable crops, with the presence of Calanchi along the Simeto river and a dense riparian vegetation band. The absence of compact historic centers allows isolated rural buildings and a notable archaeological site to stand out, contributing to the area’s cultural identity.

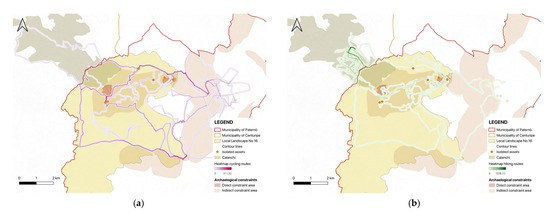

The focus on Local Landscape No. 16 is further motivated by the high level of spontaneous fruition documented via GPS tracks in GPX format downloaded from the Wikiloc platform, which is a community-based site where users share outdoor routes [5]. Specifically, a dataset of hiking and cycling tracks was collected, processed into an open-source GIS environment (QGIS LTR 3.34 Prizren) [26] and aggregated into density heatmaps through the “Concentration map (Kernel Density Estimation)” geoprocess: the points layer used was generated from the route traces using the ‘Points along geometry’ geoprocess, with a distance of 10 m between points, a radius value set to 50 m, and a raster output size set to 1 m × 1 m. In this way, it was possible to visualize the spatial concentration of activities across the study area. The resulting heatmaps reveal two main hotspots of outdoor recreational use. The first concentration of crossings is located in Contrada Poggio Cocola, an area of particular historical and landscape significance that includes the Baroness of Poira’s Castle, the Slave cave, the former Bourbon horse-breeding farm, the Rocca del Corvo, the Castellaccio Mounts, the Roman Bridge, and the historic road linking the former farm to the castle. The second marked concentration occurs in the Calanchi area, which extends into the municipality of Centuripe and is characterized by distinctive clay formations sculpted by erosion.

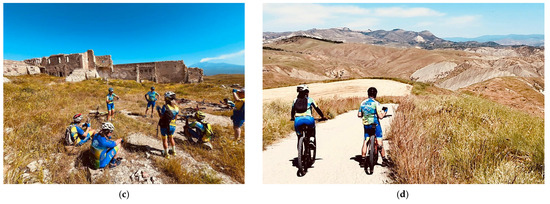

The following figures illustrate these results in detail. Figure 2a shows the density of cycling routes, while Figure 2b displays the distribution of hiking routes, demonstrating the growing interest in the area for outdoor activities. Furthermore, Figure 2c,d provides photographic evidence of groups of cyclists in situ near the ruins of the Baroness of Poira’s Castle and the Calanchi, respectively.

Figure 2.

Spontaneous fruition of the Local Landscape No. 16: (a) heatmap of cycling routes; (b) heatmap of hiking routes; (c) group of cyclists near the ruins of the Baroness of Poira’s Castle; (d) group of cyclists in the Calanchi area.

3.2. Landscape Character Assessment (LCA) and ECOVAST Methodologies

The first phase of the adopted method, that is, the landscape analysis of the municipality of Paternò, was carried out according to the LCA procedure on the ECOVAST guidelines. The integration of these two methodologies involved the selection, integration, and processing of territorial data to identify the landscape characters and the areas they occupy. These data were integrated into an open-source GIS environment (QGIS LTR 3.34 Prizren) [26] and processed using various geoprocessing tools to identify Landscape Units (LUs) offering a finer subdivision than the Local Landscape classification provided by the Landscape Plan of the Metropolitan City of Catania, to outline conservation strategies and the enhancement of local values.

The LCA procedure provides a systematic approach to analyze, describe, and classify landscapes based on their natural and anthropogenic characteristics, avoiding subjective judgments and offering a clear methodological framework for sustainable territory protection and development.

The LCA is structured into two main phases:

- Characterization: identification and classification of Landscape Units (LUs) according to geological, morphological, climatic, hydrographic, vegetational, and anthropogenic characteristics; analysis of visual landscape elements to assess perception and public use. Delineating these units allows for a deeper understanding of territorial diversity and complexity, serving as a basis for conservation, sustainable development, and planning actions.

- Judgment Formulation: identification of landscape values and potential criticalities; definition of guidelines for management, protection, and territorial planning.

Operationally, the methodology unfolds in six key steps: (1) define scope, (2) desk study, (3) field survey, (4) classification and description, (5) selection of evaluation approach, and (6) judgment formulation.

The ECOVAST methodology is an operational tool for the assessment of rural landscapes and the characterization of Landscape Units (LUs). This method is based on a ten-layer matrix that considers both physical aspects (geology, morphology, soils, and vegetation) and anthropogenic ones (land use, settlements, infrastructure, and cultural elements), as well as perceptual and emotional values. Each landscape element is evaluated according to its strength—classified as dominant, strong, moderate, or weak—based on its visibility and its contribution to landscape character. Because the method does not require complex instrumentation or advanced technical skills, it is accessible to individuals or small, non-expert groups, enabling structured community-based assessments to support planning, conservation, and landscape enhancement.

The LCA and ECOVAST methodologies (Phase 1) were applied, followed by a SWOT analysis (Phase 2) and Planning and Design for Public Fruition (Phase 3), according to the simplified workflow shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Simplified workflow of the methodology applied in the study.

The operational phases are described below in detail, from the definition of purpose through to the final delineation of Landscape Units (LUs):

- Define scope: the analysis aimed to delimit the different Landscape Units (LUs) within the municipality of Paternò, with a particular focus on Local Landscape No. 16, to support conservation and planning actions by recognizing the intrinsic values and identity of the local landscape. The analysis scale was 1:10.000, consistent with the data of the Landscape Plan of the Metropolitan City of Catania.

- Desk study: all processing described in Table 1 was carried out using the open-source software QGIS, employing official data provided by the Landscape Plan of the Metropolitan City of Catania and the Regional Technical Map 2012–2013 [27] downloaded from the Geoportal of Sicily Region. Eight thematic maps were produced, corresponding to the main steps of the analysis (Table 2).

Table 1. Spatial database utilized in the study.

Table 1. Spatial database utilized in the study. Table 2. List of the eight thematic maps with data sources and the main processes applied.

Table 2. List of the eight thematic maps with data sources and the main processes applied.

The final Landscape Units (LUs) were defined through an integrated, objective interpretation of the seven thematic maps and field observations. Boundaries and names reflect the dominant morphological, environmental, and historical-cultural characteristics:

- Field survey: targeted site visits were carried out in the main Landscape Units (LUs), with a particular focus on Local Landscape No. 16. Special attention was paid to panoramic viewpoints, rural structures, and archaeological areas. Data were collected via photographic documentation and structured field notes, using a checklist to record the physical, perceptual, and cultural features of the landscape.

- Classification and description: the collected information was synthesized into descriptive datasheets for each Landscape Unit, combining cartographic data, field observations, qualitative assessments, and photographs. Geomorphological and vegetational traits, land-use patterns, settlement structures, and visual quality were all considered. For a comprehensive characterization of the landscape, a Viewshed Analysis—a GIS-based method that identifies which areas of terrain are visible from a given observation point—was conducted using the following parameters: observer height 1.60 m, observation radius 10 km, and DEM resolution 5 m. This type of analysis is increasingly employed by landscape planners as a decision-support tool to optimize spatial land-use arrangements and evaluate the visual impact of specific landscape features [2,28].

Because this work was confined to a preliminary landscape diagnosis and the construction of a strategic framework—without undertaking the final evaluative phase or assigning scores and rankings—phases 5 and 6 were deemed unnecessary. The real “judgment formulation” will be reserved for future feasibility studies or dedicated workshops.

3.3. Criteria for the Elements of SWOT Analysis

The SWOT Analysis carried out for this work followed these general criteria:

- Strategic relevance: only factors directly affecting sustainable tourism or renewable energy potential were chosen, ensuring alignment with project goals.

- Data source reliability: entries relied on recognized regulations and planning documents for legal constraints and incentives, complemented by field observations and GIS data to capture on-the-ground conditions and risks.

- Internal versus external scope: internal factors (strengths and weaknesses) refer to conditions already present and directly manageable locally. External factors (opportunities and threats) originate from the wider context and affect the area without being entirely controlled by local choices.

- Economic, environmental, and socio-cultural balance: each item was assessed for its economic implications (investment potential and local livelihoods), environmental impact (biodiversity and land degradation risks), and socio-cultural significance (community involvement and heritage protection).

- Transferability: criteria were chosen for their applicability in similar rural contexts, emphasizing approaches that do not depend on costly or highly specialized surveys.

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Results

The preliminary analysis carried out using the LCA and ECOVAST methodologies resulted in the identification and characterization of eight distinct Landscape Units (LUs) within the study area (Figure 4):

Figure 4.

Landscape Units (LUs) within the municipality of Paternò.

- LU Simeto Nord and LU Simeto Sud: both crossed by the Simeto River, characterized by typical riparian vegetation along the watercourse.

- LU Pietralunga: characterized by clay soils and steppe grasslands dominated by Mediterranean Poodle, with a strong presence of citrus groves.

- LU Valanghe (Calanchi): dominated by wild, uncultivated Calanchi formations, constituting a unique landscape unit.

- LU Paternò: includes the urban area of Paternò, characterized by nitrophilous-ruderal vegetation and artificial irrigation systems; despite urbanization, citrus groves remain prevalent.

- LU Ponte La Barca: a large unit composed of recent alluvial deposits, featuring a mosaic of nitrophilous-ruderal vegetation and citrus groves; named after the Ponte Barca Nature Reserve.

- LU Vallone Tirabue: distinguished by its geomorphology and sparse natural vegetation due to the predominance of cultivated agricultural lands.

- LU Poggio Cocola: defined by clay soils, steppe grasslands dominated by Mediterranean Poodle, and an agricultural landscape dominated by arable land.

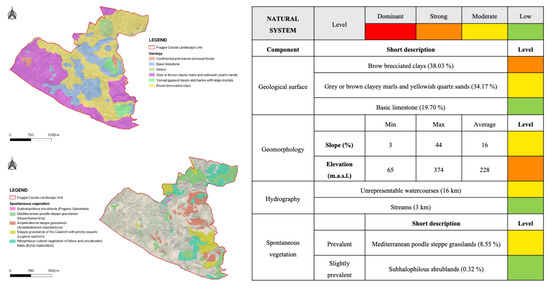

Poggio Cocola Landscape Unit

After defining the LUs, each unit was systematically characterized using structured data tables, cartographic and thematic maps, and photographic documentation, with the aim of describing the dominant morphological, vegetational, anthropogenic, and perceptual characteristics.

Since this study focused on Local Landscape No. 16, an example of the characterization of the LU Poggio Cocola—adjacent to the Calanchi geological formation and rich in historical-archaeological heritage—is presented below in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Example of thematic maps and data tables related to LU Poggio Cocola. The colours of the cells in the table on the right indicate the degree of relevance of each character: red = dominant, orange = strong, yellow = moderate, green = low.

The LU Poggio Cocola covers a total area of 1302 ha. From a geological point of view, 38.03% of the surface consists of brown brecciated clays (strong character) and 34.17% comprises gray-brown marl clays and yellowish quartz sands. The average elevation is 228 m a.s.l., with an average slope of 16%. The prevailing spontaneous vegetation is a Mediterranean Poodle steppe grassland.

The anthropogenic system is defined by dispersed rural settlements, primarily connected by unpaved secondary roads. Agricultural land use is dominated by arable crops, which cover 46.83% of the unit’s total area.

Regarding the perceptual system, the Viewshed Analysis revealed that, from the main road network and from observation points located at isolated heritage assets and archaeological areas, the most visible locations are the distant urban center of Paternò and, in part, the LUs Simeto Sud and Ponte la Barca.

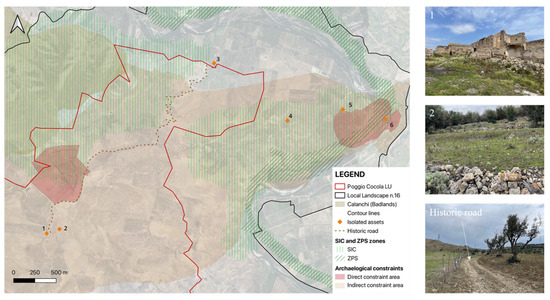

In terms of historical and cultural heritage, the unit contains an archaeological area under direct constraint, as well as a portion of a larger area subject to indirect constraint. Particular attention was given to the analysis of isolated assets within Local Landscape No. 16 (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Local assets and archaeological constraints within the Local Landscape No. 16: (1) Baroness of Poira’s Castle; (2) Slave cave area; (3) Former Bourbon Horse-Breeding Farm; (4) Rocca del Corvo; (5) Castellaccio Mounts; (6) Roman Bridge.

(1) Baroness of Poira’s Castle: now in ruins and located in a zone of high archaeological relevance, this ancient structure lies along the road connecting Paternò to Centuripe. Until the late 20th century, it was part of an active agricultural estate. The large architectural complex includes four main buildings used for residential purposes, storage, livestock shelter, and religious functions. (2) Slave cave area: on Poira hill, in 1995, the Superintendence for Cultural Heritage of Catania unearthed a Hellenistic necropolis dating to the 6th–5th century B.C., with tombs containing various styles of pottery. Nearby lies the so-called Slave cave, believed to have been a Roman ergastulum (a prison or labor camp). (3) Former Bourbon Horse-Breeding Farm: a rural complex established in 1883 by the Bourbon Ministry of War on the state-owned Pietra Lunga estate along the right bank of the Simeto River. It comprises housing for officers and troops, a canteen, administrative offices, a horse infirmary, and specialized stables for different breeds, intended for the selection of cavalry horses. Today, it is abandoned, but the original layout of the structures remains intact. Of fundamental importance is the historic paved road (a 19th-century cobblestone and dirt track) that connected the Former Bourbon Horse-Breeding Farm to Poira Castle. It is now an unpaved path immersed in Mediterranean scrub and frequented by hikers. (4) Rocca del Corvo: an isolated volcanic rock spire about 20 m high, rising in Contrada Pietralunga. Beyond its significant landscape impact, its summit serves as an important nesting site for raptors and other wild birds, contributing to the biodiversity of the “Tratto di Pietralunga del Fiume Simeto” Site of Community Importance (SIC). (5) Castellaccio Mounts: a hill alignment of basaltic ridges, with Monte Castellaccio reaching 225 m a.s.l. The area features ancient agricultural terraces, now partly abandoned, and constitutes an ecological corridor for wildlife along the “Strada delle Valanghe” between Paternò and Centuripe. (6) Roman Bridge: archaeological remains of a two-arched bridge in lava stone located in Contrada Pietralunga. Approximately 23 m long and 4.15 m wide, it also served to irrigate surrounding fields. Today, its piers and part of its abutments are visible, and 1997 excavations revealed traces of Bronze Age settlements nearby.

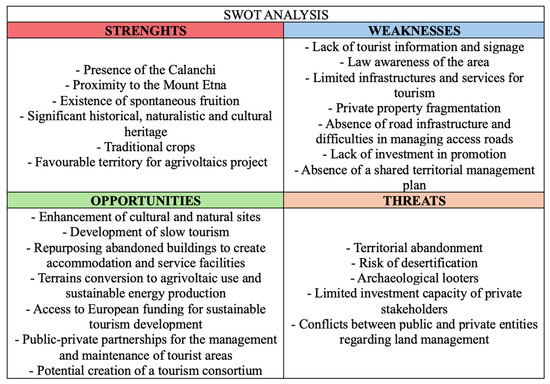

4.2. Swot Analysis

After phase 1 of this study (LCA and ECOVAST analysis), in phase 2, the critical points and potential were synthetically assessed through a SWOT analysis to identify strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats to support targeted decision-making and planning. Figure 7 lists the main strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats that emerged from the analysis.

Figure 7.

Main strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats emerged from the analysis.

The SWOT Analysis carried out in the Paternò area, especially within Local Landscape Unit No. 16, shows various internal and external factors that directly affect the area’s tourism potential and environmental sustainability.

Among the strengths, the landscape has high natural value because of the Calanchi formations and its proximity to the south-western side of Mount Etna. These are protected under the Italian Cultural Heritage and Landscape Code (Legislative Decree 42/2004) [29] and by the Regional Landscape Plan of the Metropolitan City of Catania. There is also a significant historical–archaeological heritage (many old farmhouses, pre-Hellenic and Roman sites), fully covered by Legislative Decree 42/2004. Traditional crops—vines, olives, and citrus—benefit from a unique microclimate. Because of its landforms and strong summer sunlight, the area is also well suited for agrivoltaic projects, some of which have already started. The environment also supports outdoor sports such as mountain biking and trekking. Although these activities are still mostly informal, there is already a flow of visitors using the landscape. With small improvements to infrastructure—without harming the area’s authenticity—this flow could grow.

Despite these strengths, several internal weaknesses prevent full development. First, land ownership is highly fragmented, divided into many small parcels under different heirs. This fact creates a lack of homogeneity, making it difficult to devise coherent, area-wide solutions. The lack of a Landscape Management Plan also prevents setting common rules for coordinated action, leaving only unconnected initiatives. On the infrastructure side, most roads are minor “vicinal” paths that are not officially mapped or regularly maintained. Although many of these roads are formally private, the public uses them. Their poor condition discourages tourism, hinders agrivoltaic installations, and isolates some areas. There is also not enough signage or updated tourist information: without thematic maps or information points, visitors struggle to find their way and discover the sites, reducing the benefit of the existing interest in hiking, mountain biking, and immersive trails.

Another weakness is the lack of a structured public–private coordination group. There is no consortium or governance table where public agencies and private owners can plan an integrated development project. This creates a negative cycle: private owners do not invest because rules are unclear and profitability is uncertain, and the local municipality does not do regular or extra maintenance on vicinal roads because of cost concerns. The lack of services—no quality lodging, few refreshment points, and limited public transport—makes the area a niche destination, reducing chances to attract private or public–private investments, even though the PNRR has funds for sustainable tourism regeneration.

Looking at the external context, several opportunities—if handled in an integrated way—could turn weaknesses into strengths. For example, cultural and natural sites could be promoted through “slow tourism”, which answers growing demand for authentic, low-impact experiences. Abandoned buildings could be converted into accommodations like agro-campgrounds or service centers for visitors, making better use of existing heritage. The EU Rural Development Regulation (Reg. EU 2021/2115—PNRR FEASR) [30] and the Sicily Rural Development Programme (PSR Sicily 2023–2027) [31] include measures for agrivoltaics in vulnerable areas, recognizing the dual benefits of reducing soil erosion and producing clean energy. In this process, access to European funding for sustainable tourism and forming public–private partnerships could help maintain tourist and natural areas and set up a local entrepreneurs’ consortium.

On the external threats side, several factors can undermine even well-planned strategies. The lack of a good infrastructure system, public transport, and tourism information could increase the territorial abandonment phenomenon. The risk of desertification—caused by climate change and steadily shrinking water resources (ARPA Sicily Report 2023) [32]—threatens both farming activities and the stability of clay soils, raising the chance of landslides and collapses. Another serious threat is illegal digging by archaeological looters: reduced monitoring of heritage sites due to tight budgets encourages the theft of artifacts. This not only carries criminal penalties for those involved but also often causes irreversible damage to cultural heritage, reducing the area’s appeal to tourists. Conflicts over which authority is responsible—between public and private entities—can delay the approval of management plans, slowing down road repairs and trail maintenance. The lack of a clear tourism-economic development policy prevents access to structural funds for minor tourist infrastructure. Lastly, not enough involvement of young people and local associations in deciding how to enhance the landscape is causing cultural marginalization, encouraging an informal economy to grow, and worsening unemployment and social problems.

In conclusion, the analysis shows that Local Landscape Unit No. 16 has potential because of its natural assets, archaeological heritage, and agrivoltaic projects, but it needs an integrated approach to solve infrastructure bottlenecks, private land fragmentation, and regulatory gaps. To turn opportunities into real actions, it is essential to create and implement a Landscape Management Plan, encourage public–private cooperation, and begin maintaining vicinal roads through landowner consortia supported by PNRR and PSR funds. Only in this way can the risks of desertification and looting be reduced, while ensuring sustainable and integrated enhancement of this valuable landscape and cultural heritage.

5. Discussion

The integrated “bottom-up” LCA–ECOVAST workflow—combined with Viewshed and SWOT analyses at a 1:10,000 municipal scale—offers a novel middle ground between broad regional assessments [14,15,21,23] and highly localized studies [1,6,13,19]. Other studies [16] have worked and analyzed the territory at a municipal scale.

This study differs from earlier LCA applications by uniting these methods into a single, survey-free protocol that begins with spontaneous visitor routes (Wikiloc heatmaps) and key local values (Calanchi formations, proximity to Mount Etna, and cultural and historical heritage).

Mapping eight Landscape Units (LUs) in Paternò revealed marked heterogeneity in geomorphology, land use, and perceptual qualities. In particular, the Calanchi and Poggio Cocola units underscore contrasts between raw clay badlands and heritage-rich agricultural landscapes. Quantitative Viewshed Analysis distilled visible connections among LUs—information seldom captured by purely desk-based or participatory approaches—while the ten-layer ECOVAST matrix ensured intangible attributes (cultural and emotional) were systematically recorded.

The subsequent SWOT analysis translated these characterizations into strategic insights: endogenous strengths (unique landforms and existing informal trails) suggest immediate opportunities for ecotourism corridors; weaknesses (fragmented land tenure and limited infrastructure) highlight governance and logistical barriers; agrivoltaic funding streams and slow-tourism initiatives emerge as promising opportunities; and threats such as erosion and looting demand urgent mitigation. Recommendations focus on enhancing environmental resilience through expanded green areas, increased tree cover and erosion-control measures; the adaptive reuse of rural buildings as informational hubs, eco-museums, and agritourism or eco-lodges to promote archaeological and cultural heritage; the development of sustainable agritourism and educational farms in partnership with local schools to reinforce community identity and generate employment; improved soft-mobility networks linking panoramic routes, archaeological sites, and rural centers with cycle and pedestrian paths alongside a structured vicinal-road maintenance program; and the deployment of digital wayfinding, online booking platforms, and virtual heritage guides to furnish visitors with up-to-date information.

In addition to addressing weaknesses and leveraging opportunities, it is crucial to define clear strategies for preserving the identified strengths over the long term. For the unique Calanchi formations and natural landscape mosaic, the periodic monitoring of erosion processes and the implementation of controlled access measures are recommended to prevent damage from unregulated visits and off-road vehicles. The rich archaeological and historical heritage, including the Baroness of Poira’s Castle, the Roman Bridge, and the former Bourbon horse-breeding farm, requires the establishment of specific conservation agreements and maintenance schedules in collaboration with heritage authorities and private owners. Sustaining the traditional agricultural landscape—particularly citrus and olive groves—could be supported by incentive schemes and recognition labels (e.g., organic or landscape-friendly certifications) to encourage continued cultivation and prevent land abandonment. Regarding the favorable conditions for agrivoltaic projects, it is important to promote carefully planned installations that integrate renewable energy production with soil conservation, biodiversity enhancement, and visual compatibility with the landscape. Developing clear design guidelines and monitoring frameworks can ensure that agrivoltaic systems contribute positively without undermining other values. Finally, the network of informal trails and spontaneous recreational use, and the creation of an official trail register, combined with signage, basic facilities, and community monitoring, can help formalize and protect these routes without compromising their authenticity. Finally, awareness-raising activities and educational programs targeting local schools and associations are essential to fostering a shared responsibility for safeguarding these landscape strengths as a foundation for future development.

Research Ethics Statement

Regarding the ethical principles followed in this study, no personal or sensitive data were collected at any stage of the research process. All data sources utilized, including Wikiloc heatmaps, consist exclusively of publicly available and anonymized information that does not contain identifiable user details. The analysis of these data was conducted in full compliance with established ethical guidelines for research involving digital and geospatial data, with particular attention to privacy, confidentiality, and intellectual property rights.

6. Limitations of the Study

This study has several limitations that should be carefully considered when interpreting the results and assessing the potential for replicating the methodology in other contexts.

First, the reliance on Wikiloc heatmap data as the primary source for mapping spontaneous fruition, while innovative and low-cost, introduces certain biases. This dataset mainly captures recreational practices of digitally connected users who actively record and share their tracks. Consequently, important categories of visitors—such as residents, elderly users, or occasional tourists who do not use tracking devices—may be under-represented. This sampling bias could affect the completeness of the spatial distribution and intensity of landscape use. Complementary field surveys, structured questionnaires, or stakeholder interviews could provide a more nuanced understanding of user profiles and motivations.

Second, the absence of participatory processes involving local communities, landowners, and public authorities constitutes a limitation in terms of validating both the landscape character assessment and the SWOT analysis. Although the methodological framework is designed to be desk-based and transferable, integrating co-design workshops and consensus-building activities would strengthen the legitimacy and practical feasibility of the resulting proposals.

Third, fragmented land ownership and the lack of a shared Landscape Management Plan in the study area represent major challenges for implementation. Even when clear strategies and priorities are identified, their realization requires coordinated governance mechanisms, financial resources, and administrative support, which were beyond the scope of this preliminary study.

Fourth, landscape character and patterns of fruition are inherently dynamic. Changes in agricultural practices, climate impacts (e.g., droughts, extreme weather), and new infrastructure developments can quickly alter the conditions assessed in this work. For this reason, the framework should be periodically updated—ideally every 3 to 5 years—to ensure its continued relevance and accuracy.

Lastly, while the integration of LCA, ECOVAST guidelines, SWOT analysis, and GIS-based mapping demonstrates methodological coherence, it also requires a certain degree of technical expertise in spatial analysis and interpretation. This may limit its immediate adoption by small municipalities or communities with limited technical capacity, unless adequate training or technical support is provided.

Despite these limitations, the study contributes a transparent, replicable workflow that can serve as a starting point for further investigations, stakeholder engagement, and pilot applications in similar Mediterranean rural contexts.

7. Conclusions

In this study, we demonstrated the effectiveness of a replicable, open-access workflow for sustainable landscape and tourism planning in marginal rural contexts. The integration of Landscape Character Assessment, ECOVAST guidelines, SWOT analysis, and GIS-based mapping of spontaneous fruition has proven effective for preliminary landscape diagnosis and strategic planning at the 1:10,000 municipal scale in Paternò.

The identification of eight Landscape Units highlighted fine-scale heterogeneity in geomorphology, land use, cultural heritage, and recreational patterns, anchoring planning proposals in observed visitor behavior.

SWOT analysis translated these characterizations into actionable insights, framing endogenous strengths (e.g., Calanchi formations, proximity to Etna, and spontaneous fruition) alongside critical weaknesses (land fragmentation and insufficient infrastructure) and pinpointing targeted opportunities (slow tourism and agrivoltaic incentives) as well as pressing threats (desertification and archaeological looting).

Future work should extend to bigger areas with reference to run-down areas, with further testing on territorial sections of the province of Catania and Enna, e.g., Centuripe, to help the Superintendence of Landscape and Cultural Heritage preserve and improve them. Furthermore, these works should integrate stakeholder workshops and formal governance mechanisms to advance phases 5 and 6 (evaluation criteria selection and judgment formulation) of the LCA, thereby translating strategic recommendations into prioritized, actionable projects. The adopted strategies may also be useful in the application of the objectives of the Local Action Groups (GAL—Sicily, Italy) that follow PNRR parameters to provide local services to the municipalities involved.

In conclusion, this integrated LCA–ECOVAST–SWOT methodology provides a replicable, low-cost framework for rural landscape diagnosis and sustainable tourism planning in Paternò and similar Mediterranean municipalities, bridging the gap between diagnosis and design through a clear, desk-based workflow.

Based on the results of this study, several recommendations can be proposed to support sustainable tourism development and landscape management in Local Landscape No. 16 and similar rural contexts. It is advisable that the Assessorato Regionale dei Beni Culturali e dell’Identità Siciliana, in coordination with the Parco Archeologico e Paesaggistico di Catania e della Valle dell’Aci, develop integrated management strategies that include conservation measures for archaeological sites, the monitoring of erosion processes, and initiatives to enhance the visibility of local heritage. At the same time, the Assessorato Regionale del Turismo could promote dedicated programs to improve trail infrastructure, formalize hiking and cycling routes, and support the development of visitor services and digital tools to facilitate access and interpretation.

The involvement of GAL Etna will be essential to coordinate funding opportunities and encourage innovative projects, such as the adaptive reuse of rural buildings or the implementation of agrivoltaic solutions compatible with landscape conservation. In parallel, partnerships with local associations of tourist guides can help design authentic experiences that connect natural features, historical landmarks, and traditional agricultural practices, reinforcing the area’s identity and attractiveness.

Strengthening collaboration among these institutions, together with capacity-building actions targeting local operators and community stakeholders, can contribute to creating a balanced model that combines conservation, sustainable tourism development, and socio-economic benefits for residents.

Author Contributions

The authors collaborated equally in structuring the content and therefore regard the work as a unified whole. The editorial responsibility for the individual texts is allocated as follows: Conceptualization, D.M., M.C.M.P., M.L., and S.M.C.P.; methodology, S.M.C.P.; software, D.M.; validation, M.C.M.P., M.L., and S.M.C.P.; formal analysis, M.C.M.P.; investigation, D.M.; resources, S.M.C.P. and M.L.; data curation, M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, D.M. and M.C.M.P.; writing—review and editing, D.M. and M.C.M.P.; visualization, S.M.C.P.; supervision, S.M.C.P.; project administration, S.M.C.P.; funding acquisition, S.M.C.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research study was carried out within the project: PIAno di inCEntivi per la RIcerca di Ateneo 2024/2026 (C.d.A. del 10.05.2024)—Linea di Intervento 1 “Progetti di ricerca collaborativa”—Progetto SIA3 Soluzioni InnovAtive e Strategie di sostenibilità per città, territori e società—Innovative solutions and strategies for sustainability of Cities, Land and Society. The APC was funded by the same program. Funded by University of Catania (UPB: 5A722192188).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the University Research Office for administrative and logistical support. The authors acknowledge the SICILIANBICI Associazione Sportiva Dilettantistica—located in Via Rettifilio 79, Santa Venerina (CT) 95010, Italy—for allowing the use of the photos in Figure 2c,d.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Atik, M.; Işıklı, R.C.; Ortaçeşme, V. Clusters of Landscape Characters as a Way of Communication in Characterisation: A Study from Side, Turkey. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 182, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzeo, A.; Arcidiacono, C.; Valenti, F.; Leonardi, M.; Porto, S.M.C. Viewshed Analysis-Based Method Integrated to Landscape Character Assessment: Application to Landscape Sustainability of Greenhouses Systems. Sustainability 2023, 15, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe Convenzione Europea Del Paesaggio. Available online: http://www.ecomusei.eu/ecomusei/wp-content/uploads/2010/05/convenzione_paesaggio.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Regione Siciliana Assessorato Beni Culturali Piano Paesaggistico Degli Ambiti 8, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16, 17 Ricadenti Nella Provincia Catania. Available online: https://www2.regione.sicilia.it/beniculturali/dirbenicult/bca/ptpr/documentazioneTecnicaCatania.html (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Wikiloc|Percorsi Nel Mondo. Available online: https://it.wikiloc.com/ (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Martín, B.; Ortega, E.; Otero, I.; Arce, R.M. Landscape Character Assessment with GIS Using Map-Based Indicators and Photographs in the Relationship between Landscape and Roads. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 180, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Goal 15|Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal15 (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- United Nations Goal 11|Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal11 (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Ferreira, C.S.S.; Seifollahi-Aghmiuni, S.; Destouni, G.; Ghajarnia, N.; Kalantari, Z. Soil Degradation in the European Mediterranean Region: Processes, Status and Consequences. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 805, 150106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministero dell’Economia e delle Finanze Italiano. National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR); Ministero dell’Economia e delle Finanze Italiano: Rome, Italy, 2021.

- Swanwick. Landscape Character Assessment: Guidance for England and Scotland; Cheltenham: Edinburgh, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Heritage Council. Landscape Character Assessment (LCA) in Ireland: Baseline Audit and Evaluation; Prepared by Julie Martin Associates in Association with Alison Farmer Associates; Heritage Council, Ed.; Heritage Council: Kilkenny, Ireland, 2006; ISBN 9781906304010. [Google Scholar]

- Atik, M.; Işikli, R.C.; Ortaçeşme, V.; Yildirim, E. Definition of Landscape Character Areas and Types in Side Region, Antalya-Turkey with Regard to Land Use Planning. Land Use Policy 2015, 44, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koç, A.; Yılmaz, S. Landscape Character Analysis and Assessment at the Lower Basin-Scale. Appl. Geogr. 2020, 125, 102359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trop, T. From Knowledge to Action: Bridging the Gaps toward Effective Incorporation of Landscape Character Assessment Approach in Land-Use Planning and Management in Israel. Land Use Policy 2017, 61, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solecka, I.; Raszka, B.; Krajewski, P. Landscape Analysis for Sustainable Land Use Policy: A Case Study in the Municipality of Popielów, Poland. Land Use Policy 2018, 75, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simensen, T.; Halvorsen, R.; Erikstad, L. Methods for Landscape Characterisation and Mapping: A Systematic Review. Land Use Policy 2018, 75, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, A.; Berglund, U. Landscape Character Assessment as an Approach to Understanding Public Interests within the European Landscape Convention. Landsc. Res. 2014, 39, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkoltsiou, A.; Paraskevopoulou, A. Landscape Character Assessment, Perception Surveys of Stakeholders and SWOT Analysis: A Holistic Approach to Historical Public Park Management. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2021, 35, 100418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y. Nesting Landscape Character and Personality Assessment to Intensify Rural Landscape Regionality and Uniqueness. Environ. Impact. Assess. Rev. 2025, 110, 107705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Shi, T. Landscape Character Assessment of Water-Land Ecotone in an Island Area for Landscape Environment Promotion. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 259, 120934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhou, Q.; Tian, D. Improved Landscape Sampling Method for Landscape Character Assessment. Front. Archit. Res. 2023, 12, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, D.; Gomez-Martin, E.; Milliken, S.; Parmer, D. Introducing Landscape Character Assessment and the Ecosystem Service Approach to India: A Case Study. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 167, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegler, A.; Dower, M. ECOVAST—Landscape Identification: A Guide to Good Practice; European Council for the Village and Small Town. 2006. Available online: https://www.ecovast.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/landscape_good_guid_corr_e.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Russo, P.; Carullo, L.; Riguccio, L.; Tomaselli, G. Identification of Landscapes for Drafting Natura 2000 Network Management Plans: A Case Study in Sicily. Landsc. Urban Plan 2011, 101, 228–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QGIS Web Site. Available online: https://qgis.org/ (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Regione Siciliana S.I.T.R—Sistema Informativo Territoriale Regionale. Available online: https://www.sitr.regione.sicilia.it/download/download-carta-tecnica-regionale-10000/ (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Bell, S. Landscape Pattern, Perception and Visualisation in the Visual Management of Forests. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2001, 54, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repubblica Italiana Decreto Legislativo 22 Gennaio 2004, n. 42: Codice Dei Beni Culturali e Del Paesaggio. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/atto/serie_generale/caricaDettaglioAtto/originario?atto.dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=2004-02-24&atto.codiceRedazionale=004G0066 (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- European Union Regulation (EU) 2021/2115 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 2 December 2021 on Support for Strategic Plans Under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP Strategic Plans) and Financed by the European Agricultural Guarantee Fund (EAGF) and by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD), and Repealing Regulations (EU) No 1305/2013 and (EU) No 1307/2013. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2021/2115/oj/eng (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Regione Siciliana—Dipartimento Agricoltura, S.R. e P.M. PSP 2023–2027—Piano Strategico Della PAC. Available online: https://www.psrsicilia.it/notizie/psp-2023-2027-piano-strategico-della-pac/ (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- ARPA SICILIA—Agenzia Regionale per la Protezione dell’Ambiente Annuario Dei Dati Ambientali—Edizione 2023—Arpa Sicilia. Available online: https://www.arpa.sicilia.it/documentazione-ambientale/gli-annuari-regionali-dei-dati-ambientali/annuario-dei-dati-ambientali-edizione-2023/ (accessed on 6 June 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).