Abstract

In China, an effective form of agricultural organization called an agri-industrialized union (AIU) has been on the rise and is recognized as making a great contribution to rural revitalization. However, individual AIUs appear to be conducted in different ways during their development. Some are successfully operated by active members in cohesive combinations, while some fail because of disconnection and instability. The purpose of this study is to encourage all members to take initiative and to act cooperatively to ensure high-quality resource usage in AIUs. Based on the theory of planned behavior (TPB) and the theory of perceived value, a structural equation model was used to examine the main factors affecting members’ willingness to cooperate in AIUs in Hebei Province. The data collected from a survey of 247 AIUs indicated that behavioral attitudes and subjective norms have a direct impact on cooperative initiatives. Perceived behavioral control indirectly affects cooperative initiatives. Perceived management ability influences subjective norms, while perceived interest–risk influences behavioral attitudes and perceived behavioral control, especially in hierarchical governance groups. The influences of behavioral attitudes, perceived behavioral control, and subjective norms are stronger in mixed-governance groups. The results of this research can provide recommendations for policymaking that may help to ensure the stable development of AIUs and rural development.

1. Introduction

With the specialization and organization of China’s rural economy, some limitations of the new agricultural operating entities are gradually emerging [1]. Both leading enterprises and farmers uneasily hold their own due to low agricultural-production efficiency and lack of advantage [2]. Cooperatives and family farms are in need of capital, technology, markets, and information. They have a shortage of intensive-processing ability, making it difficult for them to become larger and stronger on their own. One possible way for these cooperatives and family farms to attain more profits is mutually beneficial cooperation, involving many kinds of agricultural entity [3]. Some leading agricultural enterprises, cooperatives, family farms, and other new agriculture-related entities cooperate as agri-industrialized alliances. These organizations are based on specialized labor division and scale operations, aiming to pursue maximum profit [4]. This move is a successful example of agri-industrialization, and enriches the organization of new agricultural-management bodies. Furthermore, it builds connections between small farmers and modern agriculture effectively [5]. These industrial alliances form a close-interest mechanism among operating entities via a long-term cooperative relationship and the mutual integration of resources. The alliances strengthen the operation by the specific division of labor. This mechanism stabilizes the material connection via the optimal allocation of resources and improves agri-industrialization by integrating all members in a complete industrial chain, containing producing, processing, and marketing [6]. It also enhances interest by establishing rules of association and by having members sign contracts, both of which reduce transaction costs and, more importantly, increase competitiveness [7].

In 2016, the Leading Group of agri-industrialization of Hebei Province put forward a series of opinions guiding agri-industrialized unions (AIU). It was clearly stated that agricultural enterprises, cooperatives, and family farms functioned as the core leader, the intermediary, and the basis, respectively [8]. The AIUs in Hebei Province were established quite early in China. At present, a large number of them exist. Hebei Province has surpassed other provinces in both the quantity and the quality of AIUs. By the end of 2022, more than 200 AIUs were recognized as successful in Hebei Province. The most significant achievement of Hebei Province has been its full acceptance by the government [9]. For three consecutive years, since 2018, the AIUs have been included in Central Document No.1 policies. It was stated that the AIUs are important agri-organizations. When the central government began to take them as seriously as the local government, the AIUs received increasing attention at the national level [10]. The AIU is now commonly recognized as a rural revitalization strategy, and has gradually proven to be an important organization in supporting the development of modern agriculture [11].

With the continuous expansion and evolution of the AIUs, members may take some actions that deviate from the original intentions of the union. For example, as a part of an AIU, family farms engage in agricultural production according to the quantity and quality standards of the planting and breeding production chain [12]. However, some family farms with government subsidies and project support are completely taken over by cooperatives, which violates the purpose of policy support for organizational innovation and development. Similarly, in an AIU, some leading enterprises, after providing production materials and services at low prices or free of charge, are “betrayed” by farmers who are chasing a high market price. These enterprises have to passively bear more risks, resulting in the unfair phenomenon known as being “captured”. The AIU contains many relationships formed by common interests that unite a variety of agriculture-related members [13]. Industrialization management is mainly organized by the leading enterprises, cooperatives, family farms, and other subjects on the basis of labor division and contracts [14]. With industrial organization theory, the Harvard School considered subject behavior an important research object; the theory examined the intrinsic relationship between behavior and structure and performance [15]. It is believed that an enterprise’s behavior affects performance [16]. Various business entities in AIUs ask for higher returns and avoid practical difficulties. However, under the assumption that there are “rational people”, AIUs suffer from “moral hazard” and “adverse selection” because of the pursuit of individual interests during cooperation [17]. In order to enhance the cohesion of the interest connection between members and improve the performance and stability of AIUs, it is undeniable that understanding the behavior of business entities within AIUs is of great importance.

Members are the most essential parts of a group. The ways in which they behave and connect with others can affect how groups perform. Activating members’ desire to be more dependable and productive is vital for groups to achieve a greater goal. This raises certain questions that are related to the issue of initiative in AIUs: What are the main factors that influence members to take the initiative to cooperate and behave well? How do these factors make different operators work together; in other words, what is the effective mechanism in such relationships? In order to delineate the factors that influence members’ cooperation, this paper combines economic theory with the practices of new agricultural-management bodies and adopts the theory of planned behavior to analyze how perceived value, subjective norms, perceived behavior control, and behavioral attitudes affect members’ behavior. The structural equation model is used to examine the effect of factors influencing members’ behavior in 247 AIUs. Specifically, the main aims of this research are as follows:

- (i)

- To examine the effectiveness of influencing factors on cooperation to understand how these factors work and to establish the differences between influencing paths.

- (ii)

- To provide theoretical support for policymaking on the development of agri-cooperative organizations. This involves helping policymakers to promote AIUs’ and relative agri-operating bodies, so as to maintain the stable development of AIUs and realize the high-quality development of modern agriculture.

The main research objective pertains to factors influencing members’ cooperation initiative in AIUs. The main research objective is therefore to determine the factors in members’ initiation of cooperation in AIUs. The theoretical contribution of this paper is its presentation of the intrinsic mechanism of this process. Based on the theory of planned behavior and the theory of perceived value, this research unveils differences in the impact of the perceived value and factors mentioned in the theory of planned behavior on cooperative initiatives. The influencing path of perceived value, attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavior control, and initiative is clearly presented. This provides a new perspective from which to analyze members’ behavior in AIUs or other cooperatives. Furthermore, this study not only provides theoretical contributions but also practical benefits by identifying the relationships between members and groups. Cooperative-behavior initiatives increase the quantity of normalized AIUs and would help to devise reasonable policies. Through this study, individuals in charge of AIUs are offered some approaches to motivate cooperatives and family farms to be more active and focused, avoiding falling into Olson’s dilemma. For AIUs themselves, communities with bonds and cohesion enable members to be more productive, which ensures that groups gain more profits.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Theory of Planned Behavior and Perceived Value Theory

The theory of planned behavior was first proposed by the American psychologist Ajzen in the late 1980s, based on the theory of rational behavior [18]. It was used as a theoretical analysis tool to explain the factors affecting individual behavioral intention and choice [19]. The theory of planned behavior was widely used by researchers to analyze individual behavior. According to the theory of planning behavior, willingness is an important indicator of behavior [20], and it has the most direct effect [21]. Active behavioral attitudes, positive subjective norms, and strong perceived behavior control encourage individuals to adopt certain behaviors [22]. Behavioral attitude refers to the positive or negative evaluation that an individual forms of a certain behavior. Subjective norms refer to the social pressure felt by individuals in organizations or subjects that are significant within their external environment. Perceived behavior control refers to an individual’s perception [23,24,25] of the difficulty of exerting control over constraints. In addition to the influence mentioned in the theory of planned behavior, the perceived value theory states that the subject’s perception of value also affects behavioral decisions [26]. The theory of perceived value, which was proposed by Zeithaml in 1988 [27], was mainly used to study the comprehensive perception of products and service sales [28,29]. Perceived value arises from the comparison [30,31] between pre-behavioral expectations and outcomes after specific behavior. The more the perceived gains are, the higher the level of perceived value will be [32]. This ensures that individuals are more likely to choose to engage in specific behaviors [33].

According to the theory of perceived value, the individuals can perceive and evaluate the management ability, benefit acquisition, and risk management before they decide whether to choose positive cooperative behavior. The question is whether the perception of interest occurs before the three control conditions, according to the planned behavior theory. In other words, does the perceived value have an impact on the subjective norms, perceived behavior control and behavioral attitudes and, subsequently, does it indirectly affect the initiative toward cooperation of members? Does perceived value directly affect the members’ behavior, and does this effect significantly exceed the role of the three conditions mentioned in the theory of planned behavior? Does the perception of management ability and benefit–risk perception operate in the same ways as the factors that affect subjective behavior? In the discussion of the cooperation-initiative factors in AIUs, do subjective norms, perceived behavior control and behavioral attitudes all have a significant influence? According to previous studies and practical research, neither of the theories mentioned above is sufficient to fully reflect the behavioral practices of AIUs. This study offers a reasonable explanation for the positive cooperative behavior of new agricultural-business entities, and then provides reliable support for the cultivation of operating entities and the construction of agricultural-cooperative organizations by comprehensively considering the perception of operating entities, their own attitudes and external constraints. To this end, this paper constructs a research hypothesis from a more comprehensive perspective to answer the above questions through empirical examination.

2.2. Hypotheses and Theoretical Framework

2.2.1. Factors Affecting Cooperation Initiative

Scholars have conducted several valuable studies on the factors affecting the behavioral intentions of business entities. The theory of planned behavior was widely used as a tool to solve this issue. It chiefly holds that behavioral attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavior control have an effect on behavioral intention, based on which subjects decide to engage in specific behaviors [34]. The more positive the evaluation of behavioral attitudes, the greater the probability of engagement in a behavior [35]. In many previous studies, the significant effect of behavioral attitude on intention and behavior was verified [36,37,38,39]. Attitudes and subjective norms were related to participation among members; the participation activity increased in line with positive attitude [40,41]. This led to the acknowledgement that individuals’ behavior was influenced by attitudes and beliefs [42,43]. Farmers’ participation in activities was connected with their attitudes toward these activities [44]. Responsible attitudes motivated the farmers to choose responsible behavior [45]. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1 (H1):

Behavioral attitude positively affects cooperation initiative in AIUs.

Subjective norms reflect individuals’ perception of social pressure to engage in, or not engage in, specific behaviors [46]. The influence of subjective norms on behavior is often more important than the attitude evaluation. When the familiar or significantly related subjects or environments create more pressure to engage in a specific behavior, the likelihood of engaging in this behavior is strengthened. Farmers’ intentions were significantly affected by subjective norms, attitudes, and perceived behavioral control [47]. Responsible behavior was predicted by subjective norms and attitudes [48]. Farmers with more active behavior had more positive attitudes and subjective norms compared with those who had poor behavior [49]. The development of an organization needs the guidance of government support and a good public reputation. Individuals are more willing to engage in behaviors if many other individuals also choose to engage in the behavior and provide positive feedback. It has been proven that subjective norms affect behavior positively in many studies [50,51,52]. Furthermore, social pressure from friends, family, and culture have impact on individuals’ intentions and behavior [53,54]. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 2 (H2):

Subjective norms positively affect cooperation initiative in AIUs.

The theory of planned behavior presents many reasons why it is difficult to explain perceived behavioral control through behavioral attitudes and subjective norms [55]. Perceived behavioral control is composed of direct internal factors and indirect external factors [56]. It reflects the fact that the subject’s control over their behavior is objectively constrained by various elements [57]. When individuals find it less difficult to use resources, their tendency to take action is greater [58]. Nan Chen and Qingsheng Hao conducted a study from the perspective of enterprises to analyze the power of cooperation with farmers, and the cooperative organizations led by enterprises. They pointed out that the belief of enterprises in organization, information, and management, and their ability to maintain the relationships within their organizations help them to adopt behaviors that form connections between farmers [59]. Leading enterprises’ judgment of their expected earnings affects their behavior and attitudes, such as whether endogenous transaction costs and management costs are reduced. Furthermore, risk factors affect the behavioral attitudes and perceived behavioral control of leading enterprises [60]. The resources of enterprises affect their behavior by influencing their perceived behavioral control. Government behavior and public opinion influence the behavioral attitudes and subjective norms of enterprises leading cooperative organizations [61]. On this basis, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3 (H3):

Perceived behavior control positively affects cooperation initiative in AIUs.

2.2.2. Behavioral Attitudes, Subjective Norms, and Perceived Behavioral Control

There are interactive relationships between behavioral attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control in certain circumstances. Individuals’ subjective norms and perceived behavioral control can significantly affect their behavior and attitudes [62]. In the research on the source classification and treatment of household waste, Jing Shen et al. pointed out that subjective norms influenced behavioral intention through personal norms, behavioral attitudes, and perceived behavioral control, which in turn affected the classification of household waste [63]. Perceived behavioral control directly influenced subjective behavioral choices, while behavior indirectly affected these choices [64]. The factors that controlled the subjects’ ability was divided into internal and external factors. Both ability and external opportunities might influence subjective behavior indirectly through behavioral attitudes [65,66]. Agri-industrialized unions are more inclined to take the perception of management ability, interest, and risk as primary considerations. They then evaluate the degree of control over all resources and produce corresponding external pressure and attitudes. On this basis, this study puts forward the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 4a (H4a):

Perceived behavior control positively affects behavioral attitudes.

Hypothesis 4b (H4b):

Perceived behavior control positively affects subjective norms.

2.2.3. Perceived Value, Attitudes, Subjective Norms and Perceived Behavioral Control

In previous research, the application of the perceived value theory to explain behavioral intention or engagement in specific behaviors has yielded several results. Perceived value accurately predicted subjective-behavior results [67]. In behavior research on agricultural-management subjects, the ways in which scholars measure perceived value can be roughly divided into four categories. The first is to comprehensively measure perceived value in three dimensions: economic-value perception [68,69], social-value perception, and ecological-value perception. The second approach is to measured perceived value according to perceived benefit and perceived risk, which are presented in ratio form [70]. This measurement is based on the view that perceived value is a comprehensive evaluation [71,72] formed by comparing perceived benefits and perceived risk. The preponderance of good over harm encourages the occurrence of a specific behavior, while the preponderance of harm over good prevents this behavior, but results vary across different groups [73]. In the third approach, according to the actual situations of subjects, other factors, such as emotional and functional factors, are divided into social value, emotional value, and functional value for measurement [74,75]. In the last approach, multiple indicators are selected to form a weighted calculation as “perceived-value degree” to measure perceived value, or to directly introduce the observed variables to reflect the latent variable, “perceived value” [76]. The value perception of the subject exerts an impact on the values related to the surrounding environment, thus influencing behavioral choices through subjective norms [77]. In addition, rational actors follow the principle of profit maximization to generate the optimal combination of their own resources to achieve a state of general equilibrium state. The stronger the subject’s perception of value, the stronger their perception of their control over the elements related to their behavioral choices [78,79]. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 5 (H5):

Perceived management ability positively affects subjective norms.

According to previous studies, perceived value has a positive effect on both behavioral attitudes and subjective norms [80]. The higher the value of cooperation, the stronger the participatory attitude [81,82]; furthermore, the enhancement of value perception encourages participatory behavior [83]. In addition, there is a certain connection between interpersonal relationships, social pressure, and perceived value. This study measures the perceived value of AIUs in two dimensions, namely, management-ability perception and benefit–risk perception. The perception of benefit-sharing and perception of risk management were classified in the same dimension. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 6a (H6a):

Perception of benefit and risk positively affects behavioral attitudes.

Hypothesis 6b (H6b):

Perception of benefit and risk positively affects perceived behavioral control.

2.2.4. Theoretical Framework

In this paper, the theory of planned behavior is used, combined with the characteristics of AIU organizations and the investigation of members’ participation in cooperation. Particular attention was paid to the influencing factors that encouraged members to actively participate in the AIUs. The influence of behavioral intentions on choice is not discussed in the research framework. In the study of the influence of ecological awareness on farmers’ behavior of returning farmland to forest, we directly establish a logical framework, including behavioral attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and farmers’ behavior, considering the level of willingness to cooperate and cooperative behavior, in order to make the results more realistic and objective [84].

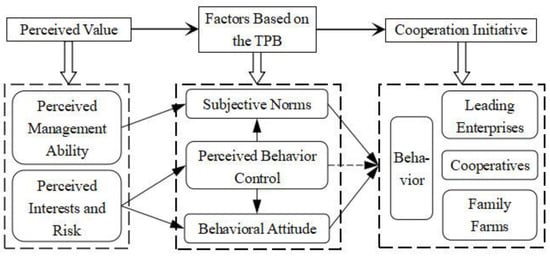

The hypothesis framework adopted in this study is given in Figure 1. The AIU managers’ perceptions of value exert effects on subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and behavioral attitudes, which in turn affected the subjects’ behavior. Furthermore, the influencing paths of management-ability perception and benefit–risk perception differ. Perceived behavioral control affects both subjective norms and behavioral attitudes.

Figure 1.

Hypothesis framework.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection

The survey data were collected in 2020 through questionnaires administered to all AIUs that were officially recognized as successful organizations in Hebei Province. The AIUs were present in almost equal numbers in Anhui Province and Hebei Province. They took various forms and boasted remarkable achievements. Hebei Province accumulated relatively rich experience in the development of agri-industrialized entities, providing a valuable learning opportunity. The questionnaire covered 126 counties and districts in 13 cities of Hebei Province. Individuals in charge of the AIUs were asked to participate in the survey and complete a face-to-face self-administered questionnaire. To save time, the authors also asked participants in supported projects to distribute the questionnaires. Furthermore, some questionnaires were completed by telephone survey. A total of 266 questionnaires were sent out to all provincial-level AIUs, of which 19 were excluded because of missing or invalid data and 247 questionnaires were collected, with an effective rate of 92.9%. The questionnaire included basic information of the AIUs and their main contents. The first part of the questionnaire focused on characteristic information, such as core enterprise rating, type, formation, governance structure, and years of operation. The characteristics of the survey are described in Table 1. It can be seen from the data in Table 1 that excluding the AIUs with unknown information, about 93% of the AIUs had been established for 10 years. There were 227 AIUs led by agri-enterprises at or above the provincial level, accounting for more than 90% of the total. In the early stage of formation, nearly 70% of the AIUs were formed by leading enterprises, which actively contacted cooperatives and family farms. The AIUs supported by government or other sources each accounted for about 15%. The AIUs whose management structure contained hierarchical government accounted for more than 90% of the total. The second part of the questionnaire was mainly related to factors that influence member initiatives in AIUs. These factors included perceived management ability, perceived benefits and risk, behavioral attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the survey data.

3.2. Measurement of Variables

According to the literature review and individual interviews, “initiative”, “behavioral attitude”, “subjective norms”, and “perceived behavioral control” were selected as the latent variables. “Initiative” was measured by the positive degree of three types of AIU member. “Behavioral attitude” included variables from three dimensions, that is, regional development, industrial development, and subjective development. The operational status of other AIUs and other members in surrounding counties were the three aspects of “subjective norms”. “Perceived behavioral control” was represented by the cognition of the objective elements and subjective factors. According to the theory of perceived value, “management ability perception” and “benefit–risk perception” were selected as exogenous latent variables. In particular, “perceived management ability” was reflected by the perception of cost reduction, industrial-chain efficiency, material supply, and quality management. “Perceived benefits and risk” were reflected by the perception of benefit acquisition, risk management, and organizational cohesion. The specific indicators are shown in Table 2. A five-point Likert scale ranging from 1, “strongly disagree”, to 5 “strongly agree”, was used to weigh different dimensions of these questions [85,86].

Table 2.

Variable Design.

3.3. Methods

Based on the intention and behavior logic of the cooperation initiatives in the AIUs, this paper uses the structural equation model for verification. The structural equation model includes a structural part and measurement part [87]. The former part reflects internal relationships between the latent variables, while the latter part reflects relationships between observed variables and latent variables [88]. In order to make full use of the prior information of the structural relationships between variables [89], this paper took “initiative”, “subjective norms”, “perceived behavioral control”, “behavioral attitudes”, “management-ability perception”, and “perceived benefits and risk” as latent variables. Each latent variable was reflected by several observable variables. The structural equation model was used to deal with the relationship between latent variables and measurable indicators [90], so it was suitable for establishing the relationship between latent variables to examine the theoretical framework and the research hypotheses shown above.

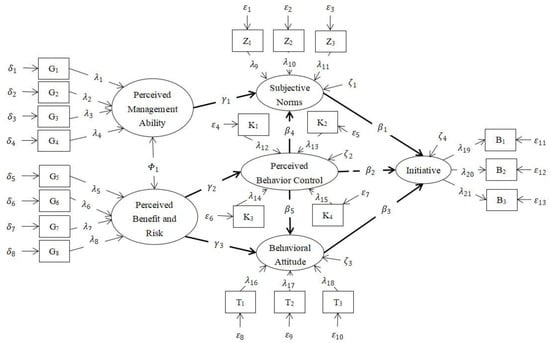

The factors directly affecting initiative included subjective norms, perceived behavior control, and behavioral attitudes. Management ability and benefit–risk perception indirectly influenced initiative. According to the preliminary examination conducted before constructing the final structural equation model, it was found that the model did not pass goodness-of-fit test and the coefficient results were not significant in the model, which supposed that ability perception affected behavioral attitude and perceived behavioral control, and benefit–risk perception affected subjective norms. Therefore, it was believed that the relationships between the above factors were not valid, and they were not included in the final model for analysis and discussion. The final structural equation model describing the path relationship is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Structural equation model of the factors influencing members’ initiatives.

4. Results

4.1. Pre-Test of Model

4.1.1. Reliability and Validity Test

According to the study by Wang et al. and Zhao et al., the SPSS software was used to conduct the descriptive analyses, as well as the reliability test. The AMOS software was used to establish the structural-equation-modeling path and show the relationship between unobservable variables [91,92]. Based on the analysis framework of the planned-behavior theory and perceived-value theory, the system measured initiative, behavioral attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, management-ability perception, and benefit–risk perception (see Table 3). The IBM SPSS statistics version 22 was used to verify the reliability and validity of the variables in the questionnaires.

Table 3.

Reliability and validity scales of the test.

It can be seen from the results that the Cronbach’s alpha values for “perceived management ability” and “perceived benefits and risk” were 0.881 and 0.880, respectively. The Cronbach’s alpha values for “behavioral attitude”, “subjective norms”, and “perceived behavior control” were 0.776, 0.896, and 0.807, respectively. The Cronbach’s alpha value for “initiative” was 0.932 and the overall alpha value of 21 indicators was 0.936. All these variables passed the threshold (0.71) and lay within an acceptable range. Therefore, the questionnaire was considered to have a high level of reliability. A factor analysis was used to test the validity of the questionnaire. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) values for “perceived management ability” and “perceived interests and risk” were both 0.832. The KMO values for “behavioral attitude”, “subjective norms”, and “perceived behavioral control” were 0.653, 0.742, and 0.770, respectively. The KMO value of “initiative” was 0.726, at a 1% significance level, meaning that it performed well. It was determined that the standard factor loading of each observed variable for cooperation initiative was greater than 0.5, indicating that more than 50% of the variance of the observed variables was reflected by the latent variables. In general, the validity level of the questionnaire was acceptable, and the validity of the questionnaire was also relatively high.

4.1.2. Model Goodness-of-Fit Test

Table 4 presents the results of the goodness-of-fit test of the theoretical model. According to the conclusions of previous research, , RMSEA, NFI, and other indicators were selected to evaluate the fitting degree of the established model [93,94]. In Table 4, PGFI and PNFI are parsimony-fit indices. The RMR and RMSEA are absolute-fit indices. The TLI, CFI, and IFI are incremental-fit indices. Managanta and Yang both mentioned in their studies that the RMSEA can be accepted when <0.08; the values are 0.074 and 0.068, respectively. Furthermore, the conclusions are GOODFIT and WELL [95,96]. Compared to the evaluation standard of the overall adaptation-evaluation index of the structural equation model given by Minglong Wu, all the index values of the listed model were within the accepted standard range. Therefore, the overall fit of the model was highly acceptable.

Table 4.

Goodness-of-fit test results.

4.2. Result of the Structure Part

Based on the structural equation model constructed by the research hypotheses, the parameter-estimation results using the IBM Amos version 21 are shown in Table 5. The relationships between all the hypotheses were included in model I. Model II rejected H3, which stated that perceived behavioral control affects initiative. The direction of influence was consistent between the latent variables in the two models, and the presented levels of significance were similar. According to the estimation results in model I, H3 was not significant, and the coefficient of H1 was only significant at a 10% significance level. All the coefficients of the model II fit the facts economically, and were significant at a 0.1% significance level, meaning that model II was better than model I.

Table 5.

Structural model-estimation results.

According to the standardized coefficients, the effect degrees of behavioral attitudes and subjective norms on the cooperation initiatives in the AIUs were similar. On one hand, the operating entities evaluate the development of regional agricultural, main industry, and agricultural subjects, and take it as a reference. On the other hand, the operating entities can make judgements according to social pressure. It is believed that the operational status of other AIUs affects whether operating entities choose to participate. Combined with the observation variables, if a member believes that an AIU is beneficial to the regional agricultural development and industry, it is certain to make a positive prediction of its prospects. With the gradual deepening of recognition of and confidence in AIUs, members are more likely to cooperate with other entities. The attitude that AIUs help new agricultural managers can encourage members, as rational actors, to undertake initiatives more directly. Individuals’ behavioral decisions are often influenced by their surroundings. If they know that AIUs in other counties increase efficiency and income, subjects are much more likely to participate in AIUs. In rural, acquaintance-based societies, if subjects receive positive feedback from other familiar subjects who have joined AIUs and shared in their benefits, then they are likely to transfer their trust in the acquaintances to the AIUs themselves, which encourages them to choose to actively cooperate.

In this study, perceived behavioral control did not directly change the members’ initiative, so H3 was not accepted. Perceived behavioral control influenced initiative through two pathways: behavioral attitudes and subjective norms. A possible reason for this is that the latent variable “perceived behavior control” was not sufficient to encourage the subjects to engage in positive or negative cooperative behavior. The resources possessed by the operating subject and difficulty in obtaining these resources are not the main concerns. In relative terms, subjects care more about the final result of input versus output. The differences between the members of AIUs and those operating in industry are not important for the individual operating subject. This has little impact on whether members actively participate in the cooperation. As economic organizations including many subjects, AIUs are affected by various factors. The reason why perceived behavioral control affects behavioral attitudes and subjective norms is that, after the beginning period, operators benefit from AIUs. It is easier for them to actively cooperate and to form positive evaluations. They are more vulnerable to positive influences from their surroundings, and eventually engage in active behavior. Taking cooperatives and family farms as examples, membership in an AIU makes it easier for actors to obtain the production materials and value-added benefits from the industrial chain, resulting in a positive evaluation of the AIUs, which in turn strengthens the reasons to cooperate. Once they perceive those other nearby AIUs and cooperatives or family farms provide benefits, upstream business entities operate in accordance with AIUs ’organizational standards and engage in mutual assistance and cooperation with downstream business entities.

The influence of perceived value was divided into two pathways, with indirect effects. In one pathway, the perception of management ability affects initiative by influencing subjective norms. In the other, the perception of benefit–risk affects initiative through behavioral attitudes and perceived behavioral control. After the operating subject perceives the management ability of the AIU, it essentially evaluates the ability level of the AIU itself, which strengthens the positive influence brought by the positive feedback from the subject’s surroundings. Conformity makes business subjects vulnerable to the influence of others, producing the “herd effect”. The choice to adopt the same behavior as others adds a sense of security to the choice to engage in cooperative behavior [97], which helps to induce the business subject to actively participate in the organization. After operating subjects perceive the benefits of sharing and risk management offered by the AIUs, they engage in active or non-active cooperative behaviors according to their external conditions, other cooperative members, and their general judgment of the advantages and disadvantages of the AIUs. For example, when a subject senses that interest is difficult to guarantee, the price and stability of the factors involved in the decision to join the AIU are affected and transactions with other operating entities are affected in turn. The perceived limitations of actual active participatory behavior increase and, at the same time, attitudes to AIUs also change. When these factors combine, subjects are more likely to adopt negative cooperation behaviors. In general, the perceptions of management ability and benefit–risk are primary considerations for rational business subjects, affecting their behavior. Both perceptions have effects on the final cooperation behavior of the operating subject, in different ways. The effects on behavioral choices made regarding “behavioral attitudes” and “subjective norms” are more significant than those of “perceived behavior control”, but “perceived behavior control” can have an influence through “behavioral attitudes” and “subjective norms”.

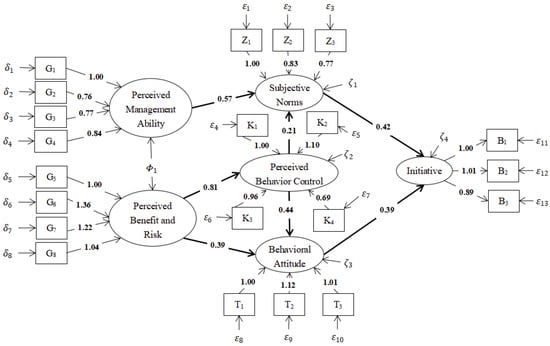

4.3. Results of the Measurement Part

As shown in Table 6, the coefficients of all the observed variables were significant with a 99.9% confidence interval. According to the standardized coefficients, the various coefficients reflecting perceived management ability, perceived benefits and risk, subjective norms, and initiative were not significantly different. They were generally above 0.7. The coefficients of T1 and T3 were 0.699 and 0.686, respectively, reflecting behavioral attitudes. The coefficient of variable K4, reflecting perceived behavior control, was 0.436, which was lower than the other observed variables that reflected the same latent variable.

Table 6.

Measurement model estimation results.

In order to visually present the quantitative relationships between the variables, the influencing path with coefficients is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The result of the factors influencing members’ initiative. Note: Bold numbers are used to highlight influential coefficients.

4.4. Heterogeneity Test

Based on the multi-group structural equation model, this study applied the heterogeneity test to verify whether the research hypothesis could still be accepted for different groups. Table 7 shows the results for model III and model IV, based on the governance structure and formation mode, respectively. Notably, the number of AIUs with “relationship-led governance” and those that were “other-motivated” was small and caused difficulties in the calculation. Thus, only groups with specific numbers were selected for the analysis. The goodness-of-fit results for model III showed that the was 1.859, the RMR was 0.041, and the RMSEA was 0.061. The goodness-of-fit results for model IV showed that the was 2.393, the RMR was 0.063, and the RMSEA was 0.076. The overall fitness and coefficient significance were not worse than in the original model.

Table 7.

Heterogeneity test results.

According to the results presented in Table 7, AIUs can be separated into the hierarchical-governance type and the mixed-governance type (hierarchy–relationship governance). According to the results, the coefficients of the structural equation models in both groups were significant, so the research hypothesis was valid. The degree to which perceived management ability affected the subjective norms and to which perceived benefit–risk affected behavioral attitudes and perceived behavior control were higher in the AIUs with hierarchical governance. In terms of the effects between the endogenous latent variables, their influence on the AIUs with mixed governance was stronger than that on the AIUs with hierarchical governance, and the path coefficient of the mixed-governance group was generally higher than that of model II. The significance of the path relations of the hierarchical-governance group was not weaker than that of the mixed-governance AIUs. This means that the positive effect of the factors influencing the behavior of the members was more clearly reflected in the hierarchical-governance group. The AIUs with hierarchical governance focused more on contract transactions and organizational management. The operating subjects were more inclined to engage in initiative behaviors based on the perception of management ability, benefits, and risk. In the AIUs with hierarchical governance and relationship governance, the effects of perceived behavior control on behavioral attitudes were stronger. The observed variables that presented the perceived behavioral control reflected the interactive relationships between different members, such as material and commodity trading in the industrial chain. It was easily concluded that perceived behavioral control influences behavioral attitudes in AIUs.

The formation mode reflected the role of member initiatives in the process of establishing AIUs. The formation modes were classified into three groups. In the enterprise-motivated group, the leading enterprises cooperate with other operating entities in the industrial chain for their own development needs in the process of production and operation. This was generally found in strong agri-enterprises. In the together-motivated group, the subjects upstream and downstream of the industrial chain generally found advantages in cooperation. They immediately established their labor division and cooperation. In this group, all the members make demands, while the strength of the leading enterprises is not sufficient. In the government-motivated group, the demand of the operating entities is not fully stimulated until the government shows its support. They cooperate after observing other AIUs. It was shown that the coefficients of the enterprise-motivated group were significant, and all the six hypotheses were accepted. Except for the coefficient of the H6a, which was not significant, the other relationships were significantly linked in the government-motivated group. Only the coefficients of H6b and H4a in the together-motivated group were significantly established. It was shown that the relationships in this model were mainly reflected in the government-motivated group and the enterprise-motivated group. In AIUs that are established through government support, operating subjects focus more closely on management ability, and less on the sharing of benefits and risk management. The evaluation of AIUs is heavily influenced by constraints on resources. The AIUs that are motivated by their members are more cohesive but are relatively lacking in competitiveness. They focus more on mutual benefits and risk management. Based on the difficulty of acquiring materials and the cooperative relationships in the industrial chain, members evaluate how well an AIU works through regional agricultural development, industrial-chain operation, and the cohesion between members. The reason why most of the influencing factors were not significant may be that the relationships between the operating entities in the together-motivated group were more complex, which cannot be effectively described by the logical framework and structural equation model used in this study, so it is necessary to expand the sample size and select other variables for examination.

5. Discussion

5.1. Further Interpretations

The study aimed to explore the factors influencing cooperation initiatives in AIUs based on the theory of planned behavior and perceived value. The SEM analysis showed that perceived values (perceived management ability, perceived benefits, and risk) and perceived behavioral control have an indirect influence on member initiatives, while behavioral attitudes and subjective norms directly affect initiative.

Perceived value was considered a key factor for future research on AIUs. Most studies have shown that cooperative behavior is associated with resources according to the theory of planned behavior. However, few studies mentioned subjective factors, such as feelings, which are quite important in cooperation. Our results were consistent with both perspectives. The perceptions of the level of organizational management ability, profit acquisition, and risk management occur before the other factors mentioned in this study, and they have different effects on individuals’ choice to actively participate in AIUs. This has not received sufficient attention in previous studies.

Previous research suggested that subjective norms, behavioral attitudes, and perceived behavioral control influenced willingness and behavior. High levels of these factors caused a greater desire to participate. In this study, the indirect effect of perceived behavior control on initiative was confirmed. Positive or negative attitudes towards AIUs and pressure from society directly affect the choice to actively participate in AIUs. The degree of confidence in the ability to perform a behavior has a more significant indirect effect on the behavioral choice of operators to participate in cooperation. The more strongly a managerial subject can conclude that it is relatively easy to actively participate, according to resource conditions, the more likely the subject is to adopt a positive attitude toward AIUs. When a positive evaluation is obtained from an external organization or subject, there is also a greater tendency to respond positively. It is believed that members of AIUs with strong managerial abilities hold positive opinions, and that this is coupled with the effect of the herd mentality, which strengthens the positive influence of positive external feedback. The choice to adopt the same behavior as others adds a sense of security to the choice of whether to cooperate. It was found that members of AIUs with higher levels of benefit acquisition and risk management usually thought that their resources and conditions affected their behavior and were more likely to form positive opinions of AIUs, which in turn encouraged them to actively participate in organization and cooperation with AIUs.

This study indicated that in the AIUs with hierarchical structures, management ability and benefit–risk perception were the main factors in their higher degree of active participatory behavior. In the AIUs with mixed structures, the operators that actively participated in groups were influenced by subjective attitudes and social pressure. The participatory and behavioral logic of the AIUs formed by the government or the leading enterprises can be explained by the logical framework constructed in this paper. The AIUs formed by the combined efforts of individuals were not included in the theoretical framework of this paper due to the immaturity of these organizations and the particularity of their operating mechanisms. This is a possible direction for further in-depth heterogeneity research.

5.2. Implications

We found that perceived management ability and perceived benefit–risk affect cooperative initiatives in different ways. This finding may provide new ideas regarding the motivation of members in AIUs. For example, the feelings of members are the major influencing factors that should be valued, even though they are more likely to be taken into consideration after organization structure and management. An evaluation focused on overall ability may be designed to improve performance.

We also found that influences are significant in both government-motivated groups and enterprise-motivated groups. The government and enterprise are the two main bodies that affect the direction of AIUs and receive more attention. This study can provide a theoretical reference for the study of AIUs led by enterprises, inspiring more loyal and active member-cooperation initiatives.

5.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Further Research

The research in this study features some limitations. Firstly, this paper did not present a discussion of the effects and significance at different stages of the AIUs. Secondly, due to the limitations of the content and research duration, this paper did not feature an analysis of the situations and characteristics of AIUs in other provinces. This meant that the paper lacked comprehensiveness and comparative data. In addition, the paper failed to present a more detailed discussion of all kinds of new-type agricultural-business entities in AIUs, which limited the in-depth analysis of the behavioral factors of and interactive relationships between operating entities. Therefore, future studies will take the above deficiencies as a starting point from which to conduct more comprehensive research.

6. Conclusions

Based on the theory of planned behavior, this paper added the theory of perceived value to complete the theoretical model for accuracy. This study tested the main factors that affect the factors that motivate members to participate in AIUs more actively and make more contributions. It also determined the different influencing paths started by perceived ability and perceived benefit–risk, and provided a reference and possible direction for further research. Some of the main conclusions are as follows.

First, members’ behavioral attitudes and subjective norms have a significant, positive, and direct effect on members’ cooperative initiatives, while perceived behavioral control significantly and indirectly affects members’ cooperative initiatives by significantly influencing their behavioral attitudes and subjective norms. Second, the perception of management ability affects members’ cooperative initiatives by significantly affecting their subjective norms, whereas the perception of benefits and risk has a significant positive impact on behavioral attitudes and perceived behavioral control. Third, these results are still significant when the AIUs are divided into hierarchical-governance and mixed-governance groups. The effect of perceived value works strongly in the hierarchical-governance group, while the effects of behavioral attitudes, perceived behavioral control, and subjective norms play a stronger role in the mixed-governance group. In addition, the cooperative initiatives in AIUs are heterogeneous due to the formation mode.

According to the conclusions from the above analysis, to improve member initiatives in AIUs, and to ensure the efficient cooperation of AIUs, the following policy recommendations are suggested. First, the formation and development of AIUs in Hebei Province shows that the government plays different roles in different periods, since the AIUs have different degrees of development and members. More specifically, the formation of AIUs is the result of the mutual selection of new agricultural-management entities under specific conditions. At this stage, excessive participation by the government should be avoided. Excessive government involvement may have a negative impact, and the market should play a greater role. In the medium term, the internal structures of AIUs are separated into different types. Those that are qualified and suitable for transformation need less policy support. According to this research, business entities with joint requirements but with little experience make relatively large requests for government guidance and policy support. The AIUs without joint requirements and sufficient conditions have even less need of government intervention. Second, the concept and advantages of AIUs need to be promoted more widely at the national level. On one hand, the government should make extensive use of typical cases. On the other hand, the differences between the demands of different objectives should be respected, while avoiding the establishment of false AIUs by enterprises and cooperatives with weaker leadership in order to obtain project support. The government should formulate more targeted policies to support AIUs and encourage them to use their special structures to explore flexible resource-sharing methods to stimulate internal strength and apply the mutual-interest mechanism. Finally, traditional connections based on mutual interest inevitably restrict the development of AIUs. Innovations in the application of the combination mechanism and the establishment of a stable community of interests are required to achieve the common prosperity of all members of AIUs. Trust between the members of AIUs should be strengthened and internal credit-information and evaluation systems should be established. The notion of spontaneous self-management among members should be taken more seriously in order to improve the self-supervision of members and reduce transaction costs and the likelihood of opportunistic behavior.

Author Contributions

Questionnaire design and distribution, data processing and analysis, writing—original draft: H.L. Methodology, writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition: R.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (grant no. 22BGL179), the Hebei Province Postgraduate Innovation Funding Project (grant no. CXZZBS2021040), and the Hebei Province Humanities and Social Science Research Project (grant no. BJ2019063).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Questionnaires.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the members of the agro-industrialized unions for participating in the interviews. They also thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments, which helped to improve this paper. We confirmed that all authors were informed about the purpose of the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chang, M. Institutional Environment and Agricultural Cooperative Economic Organization in China. J. Party Sch. Cent. Comm. C. P. C. Chin. Acad. Gov. 2012, 16, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.R.; Kong, X.Z. Economic Performance of Farmers’ Participation in Agricultural Value Chain: An Empirical Study Based on Tea Industry. J. Agro-For. Econ. Manag. 2020, 19, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.C.; Guan, N.N.; Yang, J. The Logic and Path of Promoting the Scale of Agricultural Management by the Mode of Production Organization: Analysis Based on the Typical Case of Jiangsu Province. Issues Agric. Econ. 2021, 11, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, S. The Multiple Logic of Innovation and Evolution of Agricultural Management Model: Based on the Analysis of Land Trusteeship Mode. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2019, 19, 123–130+159–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.X. The Internal Correlation and Countermeasures of Agri-Industrialization Union and Agricultural High-Quality Development. Agric. Technol. 2020, 40, 164–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.L.; Li, J.Y. The Key for Small Farmers to Connect with Modern Agriculture is to Integrate into the Modern Agricultural Value Chain. Rural Manag. 2021, 6, 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, R.G.; Han, L.H.; Wang, Q. On Financing Mode of Rural Cooperation Organization in China—From Perspective of Agri-Industrialized Unions. J. Bohai Univ. Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2021, 43, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L. The Collaborative Development between the New Agricultural Business Entites and Small Farmers: Practical Value and Pattern Innovation. Contemp. Econ. Manag. 2020, 42, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Nong, F. Preliminary Exploration and Path Optimization of Modern Agri-Industrialized Union—Based on the Case Study of Huaihe Grain Industry Union in Suzhou City, Anhui province. Rural Econ. Sci.-Technol. 2016, 27, 69–72. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Z.P. Research on Coordinated Management Mechanism of Agriculture Industrialization Union. J. Beijing Vocat. Coll. Agric. 2021, 35, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, X.M.; Chen, C.; Peng, L. Discussion on the Typical Mode of Promoting the Integration and Development of the First, Second and Third Industries in the Countryside—Taking Suzhou Modern Agriculture Industrialization Association of Anhui Province as An Example. J. Shaanxi Acad. Gov. 2018, 32, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.B.; Shao, Z.L.; Gao, Y.; Yang, H.H. Research on the Development Model of Xinjiang Agricultural Industrialization Consortium—Taking the Pepper Industry in Yanqi County as an Example. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2020, 48, 225–229. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.D. An Analysis of Modern Agricultural Industrialization Union’s Operating Benefits—A Basic Analytical Framework and Empirical Study. East China Econ. Manag. 2015, 29, 108–112. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, W.H. Study on the Union Mechanism of Agricultural Industrialization Consortium—Also on Jiangxi “Green Energy” Industrialization Consortium. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2020, 48, 214–216+220. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.S. The Theories and Practices of “Structure-Conduct-Performance” Pattern. Reform. Strategy 2008, 179, 109–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wu, H.Z.; Han, Z.A. Transfer Mode of Enterprise, Localized Embedding Behavior and Knowledge Transfer Performance—An Analysis Framework from SCP Model. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2019, 36, 119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, N.D. Behavior game and optimization strategy of stakeholders in the agri-industrialization production management mode. Theor. Investig. 2013, 2, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erul, E.; Woosnam, K.; McIntosh, W. Considering emotional solidarity and the theory of planned behavior in explaining behavioral intentions to support tourism development. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Hunecke, M.; Blöbaum, A. Social Context, Personal Norms and the use of Public Transportation: Two Field Studies. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Qi, Y.B. An Empirical Study on the Formation Mechanism of Farmers’ Green Production Behavior: Based on the Investigation of Fertilization Behavior of 860 Citus Growers in Sichuan and Chongqing. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basi 2021, 30, 493–506. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.L.; Guo, G.C.; Tan, L.Y. Study on Farmers’ Willingness to Exit Homestead and Its Influencing Factors—Based on the Survey Data of 1292 Farmers in Suzhou and Suqian. J. Agro-For. Econ. Manag. 2023, 22, 123–132. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Z.H.; Cui, M.; Zhang, H. Study on Farmers’ Green Production Willingness Based on Expanded Planning Behavior Theory. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2020, 34, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Zhou, H.M.; Yu, Z.N.; Wu, G.C. Study on the Influence of Environmental Perception on Farmers’ Homestead Withdrawal Willingness from the Perspective of the Theory of Planned Behavior—Based on the Survey of Farmers in Rural Suburbs in Shanghai. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2022, 43, 141–149. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived Behavioral Control, Self-Efficacy, Locus of Control, and the Theory of Planned Behavior1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L.; Wang, M. Influence of Value Perception Differences on Circulation Behavior of Farmers’ Homesteads. J. Agro-For. Econ. Manag. 2022, 21, 744–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V. Consumer Perceptions of Price. Quality, and Value: A Means-End Model and Synthesis of Evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, L.; Gan, C.L.; Wu, M.; Chen, Y.R. Impacts of Farmers’ Farmland Perceived Value on Farmers’ Land Investment Behaviors in Urban Suburb: A Typical Sample Survey of Wuhan and Ezhou. China Land Sci. 2018, 32, 42–50. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.G.; Yang, C.M.; Dong, W.J.; Qi, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, S.D. Farmers’ Homestead Exit Behavior Based on Perceived Value Theory: A Case of Jinzhai County in Anhui Province. Resour. Sci. 2020, 42, 685–695. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.H.; Wang, L.L.; Lu, Q. Research on Behavior of Farmers’ Adoption of Soil and Water Conservation Technology—An Empirical Analysis Based on Data Collected From 1 152 Households on Loess Plateau. J. Northwest AF Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2019, 19, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, R.B. Customer value: The next source for competitive advantage. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1997, 25, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.Y.; Chen, K. An Empirical Analysis of Farmers’ Willingness and Behaviors in Green Agriculture Production. J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2020, 4, 10–19+173–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, C. Value-driven Relational Marketing: From Products to Resources and Competencies. J. Mark. Manag. 1997, 13, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.Y.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, M.Y.; Li, H.H. Mechanism of Green Production Decision-Making under the Improved Theory of Planned Behavior Framework for New Agrarian Business Entities. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2021, 29, 1636–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergevoet, R.H.M.; Ondersteijn, C.J.M.; Saatkamp, H.W.; van Woerkum, C.M.J.; Huirne, R.B.M. Entrepreneurial behaviour of dutch dairy farmers under a milk quota system: Goals, objectives and attitudes. Agric. Syst. 2004, 80, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J., Jr.; Taylor, S. Measuring Service Quality—A Reexamination And Extension. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, D.; Sutton, S.; Hennings, S.; Mitchell, J.; Wareham, N.; Griffin, S.; Hardeman, W.; Kinmonth, A. The Importance of Affective Beliefs and Attitudes in the Theory of Planned Behavior: Predicting Intention to Increase Physical Activity1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 35, 1824–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopi, M.; Ramayah, T. Applicability of theory of planned behavior in predicting intention to trade online. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2007, 2, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Han, H. Intention to pay conventional-hotel prices at a green hotel—A modification of the theory of planned behavior. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 997–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, b.; McCaughtry, N.; Martin, J. Urban adolescents’ exercise intentions and behaviors: An exploratory study of a trans-contextual model. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2008, 33, 841–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-J.; Kim, E.S. Analysis of Korean Fencing Club Members’ Participation Intention Using the TPB Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanclay, F.; Lawrence, G. Farmer rationality and the adoption of environmentally sound practices; A critique of the assumptions of traditional agricultural extension. Eur. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 1994, 1, 59–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerin, L. Constraints to the adoption of innovations in Agricultural Research and Environmental Management: A review. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 1994, 34, 549–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.; Turner, L.; Kilpatrick, S. Using the theory of planned behaviour framework to understand Tasmanian dairy farmer engagement with extension activities to inform future delivery. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2019, 25, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghoubi Farani, A.; Mohammadi, Y.; Ghahremani, F. Modeling farmers’ responsible environmental attitude and behaviour: A case from Iran. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 28146–28161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senger, I.; Borges, J.A.R.; Machado, J.A.D. Using the theory of planned behavior to understand the intention of small farmers in diversifying their agricultural production. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 49, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Sun, P.; Zhao, F.; Han, X.; Yang, G.; Feng, Y. Analysis of the ecological conservation behavior of farmers in payment for ecosystem service programs in eco-environmentally fragile areas using social psychology models. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 550, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, J.; Cao, J.; Hu, H.; Yu, P. The influence of environmental background on tourists’ environmentally responsible behaviour. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 231, 804–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, S.S.; Catacutan, D.; Sileshi, G.W.; Nieuwenhuis, M. Tree planting by smallholder farmers in Malawi: Using the theory of planned behaviour to examine the relationship between attitudes and behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 43, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Todd, P.A. Understanding Information Technology Usage: A Test of Competing Models. Inf. Syst. Res. 1995, 5, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F. A Theoretical Extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four Longitudinal Field Studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.-C.; Lu, M.-T. Understanding Internet Banking Adoption and Use Behavior. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2004, 12, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Liang, S.; Wu, W.; Hong, Y. Practicing Green Residence Business Model Based on TPB Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Momani, A.H. Structuring information on residential building: A model of preference. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2000, 7, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, M.; Armitage, C.J. Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior: A Review and Avenues for Further Research. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 28, 1429–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellino, T. Relationships between Patient Attitudes, Subjective Norms, Perceived Control, and Analgesic Use Following Elective Orthopedic Surgery. Res. Nurs. Health 1997, 20, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, B.; Ying, R.Y. Investigating the Low Carbon Agricultural Production from the Scattered Peasant Production Behavior—An Empirical Analysis Based on TPB and SEM. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2015, 2, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Qi, Z.H.; Huang, W.H.; Ye, S.H. Research on the Influence of Capital Endowment Heterogeneity on Farmers’ Ecological Production: Analysis from Horizontal and Structural Perspectives. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2019, 29, 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, N.; Hao, Q.S. Analysis on Behavior Dynamics of Leading Enterprise Driving Farmer’s Organization Based on TPB. J. Chin. Agric. Mech. 2013, 34, 64–68. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, R.; Lu, Q.; He, X.S. Economic Analysis of Cooperation Between Leading Enterprises and Cooperative Organizations of Specialized Farmer Househoulds. J. Teach. Educ. 2006, 1, 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, N. An Empirical Study on Behavior Intention of Leading Enterprise Driving Farmer’s Organization—On Basis of TPB Theory and Leading Enterprises Survey in Jilin Province. J. Chin. Agric. Mech. 2013, 34, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhu, Y.C.; Ren, Y. Willingness Analysis of Farmers’ Participation in Smallholder Water Pipe from the Perspective of Income Differences. Rural Econ. 2018, 1, 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Qu, M.; Zheng, D.H.; Zhang, Y.X. Research on the Farmers’ Behavior of Domestic Waste Source Sorting—Based on TPB and NAM Integration Framework. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2020, 34, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.S. Analysis of Influencing Factors of Resident Participation in Community Governance Based on Theory of Planned Behavior—A Case Study of Tianjin. J. Tianjin Univ. Soc. Sci. 2015, 17, 523–528. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, J.H.; Yang, G.Q.; Zhang, J.; Wang, G. Mechanism of Farmers’ E cological Cognition Affecting Their Clean Energy Utilization Behaviors in the Yangtze River Economic Belt: An Empirical Analysis of Farmers in 5 Disitricts (Cities). J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2021, 40, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.X.; Yang, G.Q. Study on Mechanization of Farmers’ Participation Behavior in Agricultural Land Consolidation Projects. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2014, 24, 102–110. [Google Scholar]

- Dou, L. Tourists’ Perception Value, Satisfaction and Environmentally Responsible Bahaviors. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2016, 30, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, T.Y.; Wang, Z.B. Influence of Farmers’ Social Networks and Perceived Value on Their Choice of Cultivated Land Quality Protection Behavior. J. Northwest AF Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2021, 21, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, M.; Xia, X.L. Influence of Perceived Value and Policy Incentive on Farmers’ Willingness and Behavior to Maintain the Achievement of Returning Farmland to Conservation. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2022, 36, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, R.R.; Li, S.P.; Nan, L. Effects of Capital Endowment, Perceived Value, and Government Subsides on Farming Households’ Adoption Behavior of Clean Heating. Resour. Sci. 2022, 44, 809–819. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.Q.; Chi, M.M.; Wang, W.J. Research on Online Consumer Preference Prediction Based on Perceived Value. Chin. J. Manag. 2021, 18, 912–918. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H.Q.; Li, M.Q. The Definition, Features and Assessment of Customer Value. J. Northwest AF Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2007, 2, 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.H.; Cai, J. The Influences of Perceived Values and Capability Approach on Farmers’ Willingness to Exit Rural Residential Land and Its Intergenerational Difference. China Land Sci. 2016, 30, 64–72. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.H.; Wang, G.X.; Luan, S.Z. The Impact of Reference Group and Perceived Value on Environmental Protection Investment Behavior of Farmers. J. Hunan Agric. Univ. Soc. Sci. 2021, 22, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Newman, B.I.; Gross, B.L. Why we buy what we buy: A theory of consumption values. J. Bus. Res. 1991, 22, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.Q.; Huo, X.X.; Liu, J.D. Analysis on the Satisfaction and Influencing Factors of Cooperative Farmers with Agricultural Technology Service: Based on the Survey Data of 299 Fruit Growers. J. Hunan Agric. Univ. Soc. Sci. 2017, 18, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, P.J.; Lu, F.J.; Shen, Z.J. Strategic Thought on Constructing the Circulation Mode of Agricultural Products Market in China. Issues Agric. Econ. 2002, 8, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.L.; Zhang, J.B.; Feng, J.H. Farmers’ Willingness to Participate in the Market Circulation of Crop Straws and Its Influence Factors. Issues Agric. Econ. 2017, 31, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Zhao, K. Influence Factors and Effect Decomposition of Households’ Intention of Chemical Fertilizer Reduction: An Empirical Analysis Based on VBN-TPB. J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2018, 6, 29–38+152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.J.; Bai, X.S.; Hu, Y.H. An Empirical Study on Perceived Value and Anticipated Regret Affecting Intention to Purchase Green Food. Soft Sci. 2016, 30, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.F.; Yu, B.; Liu, H.Z.; Meng, Q.H.; Qian, Q.Y.H.; Zhao, Y. The Behavioral Intention and the Influencing Factors of Yunnan Traditional Chinese Medicine Health Tourism Based on an Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Model. J. Yunnan Univ. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2021, 44, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.C.; Soutar, G.N. Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordlund, A.M.; Garvill, J. Value Structures behind Proenvironmental Behavior. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 740–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.T.; Wang, Z.Y.; Yan, L. The Influence of Ecological Cognition on Farmers’ Grain for Green Behavior: Based on TPB and Multi-group SEM. China Land Sci. 2019, 33, 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Matell, M.; Jacoby, J. Is There an Optimal Number of Alternatives for Likert-scale Items? Effects of Testing Time and Scale Properties. J. Appl. Psychol. 1972, 56, 506–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubke, G.H.; Muthén, B.O. Applying Multigroup Confirmatory Factor Models for Continuous Outcomes to Likert Scale Data Complicates Meaningful Group Comparisons. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2004, 11, 514–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.H.; Ma, Y.L.; Sun, Y.Z. The Behavioral Intention of Enhancing Effective Participation by Members for the Directors of Farmers’ Cooperatives. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2021, 11, 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.H.; Hou, B.; Gao, S.R. An Analysis of Individual Farmers’ Households’ Perception on Pesticide Residues and the Main Determinants Based on Structural Equation Modeling. Chin. Rural Econ. 2011, 3, 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, L.Y.; Zhao, M.J.; Xu, T. Economic Rationality or Ecological Literacy? Logic of Peasant Households’ Soil Conservation Practices. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2016, 16, 86–95+156. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, H.T.; Zhao, M.J. Willingness to Pay Differences Across Ecosystem Services and Total Economic Valuation Based on Choice Experiments Approach. Resour. Sci. 2015, 37, 351–359. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Li, C.; Liu, J.; Zhang, S. Research on Farmers’ Willingness of Land Transfer Behavior Based on Food Security. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Xue, Y.; Geng, L.; Xu, Y.; Meline, N.N. The Influence of Environmental Values on Consumer Intentions to Participate in Agritourism—A Model to Extend TPB. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2022, 35, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Q.K.; Li, F.; Chen, X.X.; Wang, W.L.; Meng, Q.M. Performance of Fit Indices in Different Conditions and the Selection of Cut-off Value. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2008, 01, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Liang, Y.S. The Essence of Testing Structural Equation Models Using Popular Fit Indexes. J. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 38, 987–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Managanta, A.A.; Sumardjo; Sadono, D.; Tjitropranoto, P. Strategy to Increase Farmers’ Productivity Cocoa Using Structural Equation Modeling. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1107, 012105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.T.; Yao, M.; Yang, Y.W.; Ye, Q.; Lin, T. Relationships Between Children-Related Factors, Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction, and Multiple Happiness Among Urban Empty-Nesters in China: A Structural Equation Modeling. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.H.; Li, S.P.; Li, H. Adoption Behaviors of Farmers’ Chemical Fertilizer Reduction Measures Based on the Perspective of Social Norms. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2018, 32, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).