Abstract

Solving important social problems and promoting sustainable development requires solutions involving multiple stakeholders. Nevertheless, previous social marketing studies were limited to individual behavioral changes and lacked a perspective to involve surrounding stakeholders. This study focused on education for sustainable development (ESD) on a field trip and clarified the factors that promote students’ knowledge diffusion from the viewpoint of network externalities. A questionnaire was distributed, and responses from 1950 high school students were collected. This study used factor analysis to unveil the factors related to students’ features and field trip experiences and clarified how these factors promote driving network externalities and expanding the network through regression analysis. The findings indicated that the experiential value obtained from visiting a site with actual social problems has a large positive effect on driving network externalities and expanding the network. Therefore, encouraging driving network externalities and expanding networks by providing ESD on a field trip can contribute to solve social problems and achieve sustainable development.

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Purpose

Encouraging more people to be aware of citizenship through education and to participate in problem-solving is necessary for sustainable development [1]. Social change can be realized by deepening the mutual understanding among various stakeholders [2]. Nevertheless, the next generation of young people lacks knowledge about sustainable development [3]. Therefore, the importance of research on education for sustainable development (ESD) in universities has been pointed out [4], and universities recognize the necessity for such education services [5]. However, because universities traditionally focus on teaching specialized knowledge in specific fields, providing ESD before high school is important to enhance learning effects and to achieve social change.

Student interest and knowledge can be increased using collaborative learning that enables them to learn from each other about real-life social problems and to go to the actual field related to these problems [6,7]. However, schools lack sufficient resources to prepare such actual field trips for students. This situation has caused companies to emerge that provide services that enable students to go on field trips to areas with various social problems (e.g., [8,9]). Social marketing is required to develop their social business on field trips because the demand for field trips is lower than that for a classroom education. Social marketing is a marketing framework or tool for consumers and their surrounding environment to realize the social good by encouraging consumers to change their behavior [10]. Traditionally, social marketing has focused on transforming downstream end-consumers’ behavior, while researchers and practitioners have broadened their interest in upstream social institutions in recent years [11]. However, achieving social change through downstream social marketing that aims to change the behavior of the target group of students is difficult because the number of students who participate in ESD field trips is limited. Additionally, succeeding in upstream social marketing is difficult because the various viewpoints of several stakeholders are intertwined in wicked social problems.

A bottom-up approach that expands from the micro to the macro perspective is effective. In other words, students who are given an education must not only take action to solve social problems but also must spread the knowledge that they learned to promote behavior changes in their surroundings. However, social marketing studies have focused mainly on program management [12] and social structure [13] and have not addressed behavioral changes related to consumers’ diffusion behavior. This study applies the concept of network externality. The direct effect of network externalities is that the gains from adopting a product or service increase depending on the increase in the size of the population using that product or service [14]. Satisfying the requirements for network externalities encourages students to disseminate what they have learned, which in turn promotes social change. Therefore, social marketing on ESD field trips should promote the direct effect of network externalities. The purpose of this study is to clarify the factors that drive network externalities and expand the network for social problem-solving through ESD field trips.

1.2. Research Design, Contributions, and Paper Structure

To achieve the research purpose, this study examines effects of students’ features and field trip experiences on driving network externalities and expanding the network for social problem-solving. The research design is as follows: First, this study a conducts questionnaire survey of high school students who participate in the actual ESD field trips by receiving support from a company providing ESD field trips. Then, collected data are analyzed by statistical analysis. As a result, the effects of students’ features and field trip experiences on driving network externalities and expanding the network for social problem-solving are discussed.

As a result, this study makes three main contributions. First, the findings on bottom-up approaches develop the social marketing literature through the application of network externalities. Second, this study contributes to the literature on ESD by clarifying the factors that encourage spreading the knowledge that students learned. Third, this study adds insights into the potential contribution to sustainable development from social enterprises that provide ESD.

The structure of this paper is as follows: In the next section, the research perspective of this study is provided through a literature review on ESD, social marketing, and network externality. Then, the survey conducted by this study is explained and the analysis results are provided. Finally, the contributions of this research and future research directions are discussed.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Education for Sustainable Development

Education is an essential tool for young people and future generations to use to solve social problems created by the current generation [15]. Education changes people’s behavior and consciousness and enables the pursuit of individual well-being as well as the sustainable well-being of the Earth and communities through problem-solving [16]. Education on the subject of social sustainability is called education for sustainable development (ESD), and the relevant research has been mainly conducted on universities’ curricula because generating new knowledge is easy and opportunities exist to adopt generated knowledge in society [17]. ESD includes not only environmental education but also education on economic and social problems [18]. Unlike traditional education, ESD students are required to acquire problem-solving skills rather than detailed knowledge of a particular discipline [19]; they also must acquire the ability to solve problems through consensus building with various stakeholders in actual societies [20].

Although some global commonalities exist among the social problems addressed by ESD, learning knowledge related to the actual fields is essential because the situations and social backgrounds are different at each site [21], and students can learn deeply by going to the field at which the social problems occur and learning empirically [22]. However, conventional education programs are designed to enable the student to acquire specialized knowledge in a specific discipline, and an environment for integrating the interdisciplinary knowledge required for ESD has not yet been sufficiently established [23]. Therefore, changes in the educational curriculum are required [24]. Although previous studies focused primarily on the development of educational curricula at universities, an important topic is how students learn by ruminating on the knowledge and skills learned over a long period that enable them to transform society [25]. Consequently, ESD to increase interest in social sustainability through high school learning must be developed. When students are young, motivating them leads to problem-solving actions rather than direct knowledge of problem-solving [26]. Building sustainable development values from adolescence provides a foundation for students to change their behavior [27] and arouses the intrinsic motivation that leads to behavioral change for social change, which is not simply about getting good grades in the classroom [28].

Promoting ESD requires teachers to have multiple visions rooted in society’s actual situations [29]. Furthermore, engagement with diverse stakeholders is required to make progress in learning about the social problems that impede sustainable development [30]. However, transforming educational institutions for ESD is not easy [31]. Providing ESD using only school resources is difficult because teachers have limited knowledge and time [32]. Therefore, social enterprises have provided educational programs that promote ESD by utilizing external resources through field trips [8,9]. These social enterprises offer ESD on the basis of the knowledge and skills accumulated by learning in the field and introduce the field of social problems that match each school’s educational demands. This approach allows schoolteachers to avoid spending a lot of time on ESD and to provide students with advanced ESD even if they do not have interdisciplinary skills for teaching ESD. Students need to actively teach each other to encourage the actions that lead to social change [33]. In addition to providing such a learning environment, field trips create the opportunity for students to grasp problems from diverse perspectives by going to the actual fields where the social problems exist [34,35]. By participating in practical learning through field trips, students are expected to acquire new values and change their behavior [36]. Some students have already organized volunteer groups from their experience with ESD field trips [8]. However, students need to influence others to change their actions to realize social change, because the number of students is limited and the impact is very small if they try to solve social problems by themselves. Therefore, social marketing to drive network externalities and expand the networks is required.

2.2. Social Marketing

Social marketing has been studied as a tool to enhance the well-being of individuals and societies through business [37]. Social problems can be solved through field trips by engaging in social marketing to stimulate changes in students’ diffusion behavior. Although social marketing has already been adopted in tourism [38], traditional social marketing aims to change individual behavior, and researchers have overlooked the influence of spreading behavioral change [39]. The realization of social change is needed to simultaneously promote changes in both individual behavior and the environment that supports the individual’s behavioral change [40]. Promoting sustainable development through field trips requires that students are encouraged to take action to solve problems both by themselves and by involving the surrounding people in the problem-solving by spreading the knowledge and skills that they gained from field trips.

The importance of upstream social marketing in influencing the macro environment such as policies has been pointed out as opposed to traditional downstream social marketing that influences changes in individual behavior [41]. However, creating consensus over policies is difficult because of the diverse nature of stakeholder viewpoints of sustainable development. When attempting to promote behavioral change through social marketing, social norms rooted in values that differ from that of the behavioral change can be barriers [42]. Therefore, rather than attempting to directly change upstream policies from the beginning, downstream can affect upstream; that is, changing individuals’ surrounding environment can occur by encouraging individual action to change their environments. In other words, a bottom-up approach that broadens from downstream to upstream is necessary rather than separately considering downstream and upstream. Initially, individuals influence their family and friends to change their environment [43], and gradually changing their surrounding environment inevitably promotes the desirable behavioral changes in individuals [44]. As a result, macro social changes are realized through individual behavioral changes [45]. That is, social marketing that encourages students to diffuse what they have learned from field trips needs to be developed. Both education and marketing are significant tools for changing human behavior [46] and combining them can promote social change.

The logic that the value emerging from service is co-created has diffused throughout the social marketing research field [47,48]. This logic implies that the social good, which is the purpose of social marketing, is co-created by encouraging people’s participation [49,50]. The value of ESD in field trip services represents the social change created by students’ human networks because the value of services is created from human networks composed of consumers and is achieved through knowledge sharing and resource integration [51,52]. Value creation for society is realized by more people changing their behavior [53]. In other words, social change is achieved not only by social enterprises but also is co-creatively realized by encouraging many stakeholders to participate through students’ diffusion behavior. For this purpose, involving indifferent bystanders through social marketing is important [54]. Students’ diffusion behavior in spreading a new moral code to surrounding adults can establish social norms that solve problems across generations and achieve sustainable development [55,56].

2.3. Network Externality for the ESD

This study seeks to realize social change through ESD field trips and applies the network externality concept as a measure to demonstrate the effect of human networks. Network externality is a concept originally developed in economics and means that the gains that a group receives from adopting a product or service depend on the group’s size [14]. The telecommunication network is a typical example [14]. For example, the telephone offers almost no gains for users if no other user uses a telephone, and the gain increases gradually as the number of users increases. The gain received from a product or service and the number of users mutually and cyclically increase when such a mechanism works; thereby, the product or service is spread exponentially [57]. Two types of network externalities exist: direct and indirect effects—also called direct and indirect network effects. The former type is synonymous with the network externality previously explained. The latter is a phenomenon observed in markets that have a two-sided or multi-sided form through the platform (e.g., [58,59,60,61,62,63]). The indirect network effects mean that one group’s gains depend on the size of the other groups that exist on the same platform, and this works for every other group [60,64].

Of these two network externalities, this study focuses on the direct effects. The direct effects of network externality are used as a metaphor and gains are defined as the extent to which social problems are solved and sustainable development is promoted, and the direct effects of network externalities in this study are defined by “the size of the group of people who aim to solve social problems being linked to the degree of sustainable development promotion”. For this mechanism to work, the following three factors are needed: involvement (contact with a solution to social problems), engagement (willingness to take voluntary actions for a solution to social problems), and cooperation (cooperating with others’ activities). The number of people who actually take action to solve social problems increases if these factors are satisfied and, thereby, the efficiency and effectiveness of actions to solve social problems through stakeholder cooperation increase because they have the willingness to solve social problems as the number of people involved in the problem-solving increases.

Consequently, this study provides a metaphor for driving the direct effects of network externalities in a series of approaches for network function and expansion through the ESD. Therefore, this study focuses on the effects of three factors of network externalities (i.e., involvement, engagement, and cooperation) on ESD students. Furthermore, as previously mentioned, students’ changes in behavior that actively diffuse the knowledge and skills learned from ESD to surrounding people are also important. Hence, this study focuses on the influences of ESD field trips on students’ diffusion behavior in addition to the three previously mentioned factors.

3. Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Sample

The authors received support from Ridilover Inc. (Tokyo, Japan) [8], a social enterprise providing ESD field trips, in conducting a survey of high school students who have participated in a field trip. Ridilover has been providing ESD field trips that connect schools and social problems in Japan since 2011, and over 2000 students participate in their field trips every year. The survey was conducted before (pre-survey) and after (post-survey) the field trips. The questionnaire was distributed to 2654 students from twelve schools, and 1950 valid responses were used in the analysis. Less than 30% of the respondents answered the questions about age and gender because of time limitations and privacy, but all respondents were 16 to 17 years old, and every school that participated was coeducational.

On the field trips, small groups of approximately five students with similar interests in social problems were formed, and each group selected a field among the prepared themes, such as environmental conservation and economic development. An example schedule of a field trip is shown in Table 1. The field trips are held in one day and the students receive prior learning of approximately 10 h at school before the field trip. The field trip program is divided into morning and afternoon sessions. In the morning session, students visited the site and listened to lectures from activists or victims and then interviewed them. For example, on the theme of environmental conservation, students visited and observed the recycling plant of a company that provides recycling services to reduce waste and listened to approximately an hour of lectures by executives. In the afternoon session, each group discussed ideas for solving the social problem using the information they obtained in the morning session and prior learning. Finally, each group presented its ideas to all of the students. A pre-survey was conducted after prior learning, and a post-survey was conducted after the final presentation.

Table 1.

An example schedule of a field trip.

3.2. Measurements

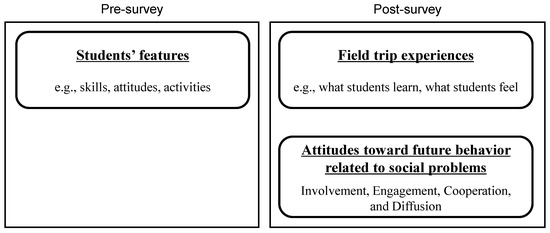

As shown in Figure 1, the questionnaire was divided into three categories: students’ features, field trip experiences, and attitudes toward future behavior related to social problems. The responses to all questions were given using a five-point Likert scale format. Questions about students’ features were asked in a pre-survey, and the other two groups of questions were asked in a post-survey. The bias was reduced by mixing the questions on field trip experiences and attitudes toward future behavior related to social problems.

Figure 1.

The structure of the questionnaire.

Questions on students’ features and field trip experiences were created and selected from previous studies [65,66,67], considering the program contents of the field trips. Because multiple indicators are more useful than a single indicator to measure tourist loyalty [68], the following four objective variables were represented in questions asked on the attitudes toward future behavior related to social problems from the viewpoint of driving network externalities and expanding the network: involvement (“I want to be involved in social problems in the future”), engagement (“I want to visit the site of social problems again”), cooperation (“I want to cooperate with people I met on the field trips”), and diffusion (“I want to tell other people what I learned from the field trips”).

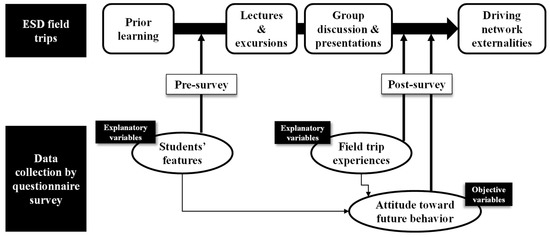

The research procedure is shown in Figure 2. To identify effects of explanatory variables (students’ features and field trip experiences) on objective variables (attitude toward future behavior related to social problems), this study reveals the factors that drive network externalities and expand the network for social problem-solving through ESD field trips.

Figure 2.

Research procedure.

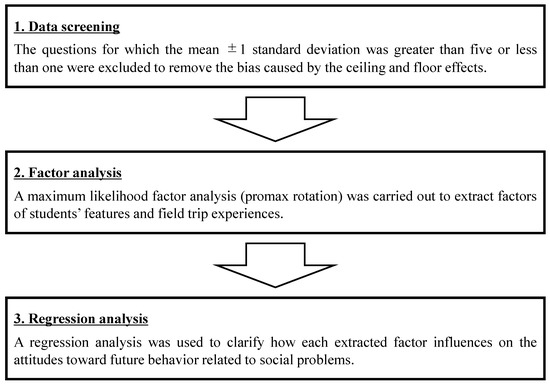

3.3. Methods of Analysis

This paper aims to clarify the factors that drive network externalities and expand the network for social problem-solving through ESD field trips. The analytic procedure is illustrated in Figure 3. First, questions were screened. To remove the bias caused by the ceiling and floor effects, the authors excluded the questions for which the mean ± standard deviation was greater than 5 or less than 1.

Figure 3.

Illustration of the analytic procedure.

Second, a maximum likelihood factor analysis followed by a promax rotation [69] was carried out to extract factors of students’ features and field trip experiences. The number of factors was determined according to the scree test, and only items with a factor loading of 0.5 or more were embraced [70].

Third, a regression analysis was used to clarify how each extracted factor influences attitudes toward future behavior related to social problems. In the regression models, four responses about the attitudes toward future behavior related to social problems (i.e., involvement, engagement, cooperation, and diffusion) were set as the objective variables and the factor scores on the above extracted factors were set as the explanatory variables. Here, since Likert scale responses have an ordinal nature (excluding their use with cumulative calculations), using parametric analysis is not recommended [71]. Therefore, the responses to the four objective variables were converted into binary data to be applied to logistic regression analysis. The answers were divided into two groups (i.e., one group consisting of the answers “agree” and “strongly agree” and one group consisting of the answers “disagree” and “strongly disagree”) and the answers consisting of “neutral” were removed. The logistic regression is an appropriate method for our purpose because this method enables researchers to analyze the effects of explanatory variables on a binary objective variable [72].

4. Results

4.1. Results of Factor Analysis

Table 2 provides the results of the factor analysis of students’ features. The scree test shows that four factors were valid. The sum of the ratios of the variance explained by the four factors was 56.8%. Although the recommended average variance extracted (AVE) is 0.5 or higher [73], the factor has appropriate reliability if the AVE is 0.4 or higher and the composite reliability (CR) is 0.6 or higher [74]. An acceptable Cronbach’s alpha is 0.7 or higher [75]. The four extracted factors met these criteria and are sufficiently reliable. Factor 1 is defined as communication skills because it consists of items representing the ability to communicate. Factor 2 is defined as tenderness because it consists of items that show warmth for friends. Factor 3 is defined as knowledge because it consists of items that represent the degree of knowledge about social problems. Factor 4 is defined as prosociality because it consists of items representing participation in social contribution activities.

Table 2.

Results of factor analysis on students’ features.

Table 3 provides the results of the factor analysis on field trip experiences. Three factors were found to be valid by the scree test. The sum of the ratios of variance explained by the four factors was 58.1%. All three factors are sufficiently reliable, because they met the AVE, CR, and α criteria. Factor 1 is defined as solidarity because it consists of items representing a sense of belongingness with group members. Factor 2 is defined as self-efficacy because it consists of items that highly evaluate one’s ability. Factor 3 is defined as experiential value because it consists of items related to the experience gained from visiting the site at which social problems occur.

Table 3.

Results of the factor analysis on field trip experiences.

4.2. Results of Logistic Regression Analysis

4.2.1. Specification of Regression Analysis

For the logistic regression analysis, seven factors extracted from the results of the factor analysis were used as explanatory variables, and four questions on attitudes toward future behavior related to social problems were used as binary objective variables. The logit model is shown as follows:

where i represents individual respondents, β is the coefficient of each variable, is an error term, and C is a constant. Table 4 provides the correlation matrix of the explanatory variables. Although some moderate correlations are observed, high correlations were not observed (maximum 0.59).

Table 4.

Correlation matrix of explanatory variables.

4.2.2. Regression Analysis Results

Table 5 provides the results of the logistic regression analysis. With respect to the effect on involvement, all of the explanatory variables, except for the tenderness factor, had a significant effect (all p < 0.01), and a negative effect was confirmed only for the communication skills factor. These results imply that the higher the knowledge, prosociality, solidarity, self-efficacy, and experiential value factors, the higher the possibility of involvement in social problems in the future. In contrast, the higher the communication skills factor, the lower the possibility of involvement in social problems in the future.

Table 5.

Results of logistic regression analysis.

With respect to the effect on engagement, all of the explanatory variables, except for the tenderness and solidarity factors, had a significant effect (all p < 0.01), and a negative effect was confirmed only for the communication skills factor. These results imply that the higher the knowledge, prosociality, self-efficacy, and experiential value factors, the higher the possibility of engagement in social problems in the future. In contrast, the higher the communication skills factor, the lower the possibility of engagement in social problems in the future.

With respect to the effect on cooperation, all of the explanatory variables, except for the tenderness and prosociality factors, had a significant effect (p < 0.01 or 0.05), and a negative effect was confirmed only for the communication skills factor. These results imply that the higher the knowledge, solidarity, self-efficacy, and experiential value factors, the higher the possibility of cooperation in social problems in the future. The factors related to field trip experiences showed a stronger influence on cooperation than those related to students’ features. In contrast, the higher the communication skills factor, the lower the possibility of cooperation in social problems in the future.

With respect to the effect on diffusion, all of the explanatory variables, except for the knowledge factor, had a significant positive effect (p < 0.01 or 0.05), and a significant negative effect was confirmed only for the communication skills factor. These results imply that the higher the tenderness, prosociality, solidarity, self-efficacy, and experiential value factors, the higher the possibility of diffusion behavior regarding the knowledge learned in field trips in the future. In contrast, the higher the communication skills factor, the lower the possibility of diffusion behavior regarding the knowledge learned in field trips in the future.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

Social marketing has long evolved to focus on promoting behavioral changes in individuals who cause social problems [76]. Since then, researchers have pointed out the significance of not only changing end-consumers’ behavior but also promoting upstream social marketing that works on social norms from a more macroscopic perspective. However, although previous studies demonstrated that upstream social marketing could affect behavioral changes in individuals, its impacts have remained unidirectional and bottom-up impacts from downstream to upstream have been ignored [77]. Although the need for research on such upward social marketing has been pointed out [78], previous studies did not shed light on factors promoting individuals’ diffusion behavior. This study focused on a social business that provides an ESD field trip and analyzed factors that promote individual social problem-solving behavior and diffusion behavior from the viewpoint of network externalities. The findings of this study indicate that the experiential value obtained from visiting a site with actual social problems has a large positive effect on driving network externalities and expanding the network, whereas communication skills have a small negative effect. This result implies that experiential learning is more effective than direct dialogue in terms of promoting upward social marketing.

Diverse stakeholder participation is required to achieve sustainable development [79]. Social change can be realized by clarifying issues to be solved and necessary actions among various standpoints, and ESD has been studied as a means to promote such change. However, research on ESD has focused mainly on evaluating students’ problem-solving competencies [80]—ESD has rarely been analyzed in terms of spreading the knowledge that students have learned. The findings in this study indicate that field trip experience factors showed a stronger positive influence than factors related to students’ features on driving network externalities and expanding the network. In addition, among the students’ features factors, communication skills had a negative effect on driving network externalities and expanding the network. In other words, students who were usually good at expressing themselves were hesitant to spread what they learned about social problems. In this study, this phenomenon is called the “paradox of communication in sustainable development”. One reason for this phenomenon is that students realize that social problems exist that cannot be solved only by dialogue on an ESD field trips. They learned that to solve social problems, social and business changes might be required that they cannot immediately support due to their skill limitations.

Involving diverse stakeholders in solving social problems can lead to social change that benefits not only the victims but also others [81]. This research contributed to the literature on sustainable development by clarifying the role of the social enterprises that play an intermediate role. Existing research classified whether social enterprises play a role in sharing similar resources with stakeholders or promoting heterogeneous transactions [82]. This classification is useful for solving specific social problems, but taking a more comprehensive view from a meta-perspective is necessary if one company attempts to address diverse social problems related to sustainable development. For this research, a social enterprise plays the role of a platform to solve social problems by providing ESD field trips and aims at the direct effects of network externalities to solve problems by sharing knowledge of problem-solving among different sectors. They provide the knowledge of social activists and enterprises to students and schools. This role is different from the one that the conventional social enterprise plays by aiming to promote social change by concentrating similar knowledge in one place [82]. The social enterprise, which is our research target, aims to create new social norms by expanding knowledge to various sectors through consumers’ diffusion behavior in addition to increasing direct problem-solving behavior. They provide social marketing using the ESD field trips as a mean to efficiently achieve the integration of individual interests, which is indispensable for realizing cross-sectional collaboration to solve social problems [83]. The significance of the social enterprise is to allay the conflicts that occur when different stakeholders, such as the social sector and schools, are connected. This study found that they were effective in their aim to drive network externalities and expand the network starting from the questionnaire survey. The increase in the number of social enterprises that play such a role as a platform will lead to changes in various industries’ long-term customs and create significant social value through broader cooperation [84].

5.2. Practical Implications

The findings revealed that field trip experiences can affect driving network externalities and expanding the network more than students’ features. The results imply that an ESD field trip provided by social enterprises is useful to promote students’ diffusion behavior for solving social problems. Although stakeholder selection is important in solving social problems [85], the ESD field trip gives students an opportunity to access social problems and recognize which problem matches their short-term interests. Students deepen their understanding of others by interacting with people in the field and experiencing solutions to social problems using logic that differs from what they learn in school. In addition, the learning form that combines onsite visits and group discussions—the program of an ESD field trip—may be effective in cultivating students’ experiential value, self-efficacy, and solidarity. Through interviews at lectures and group discussions, students repeat exchanges of conversations and texts to create social value. Combining and repeating two types of communication—conversations and texts—are important for a collaborative organization to create social value [86].

Previous studies divided the knowledge of sustainable development into knowledge related to environmental conservation mechanisms (e.g., how greenhouse gases lead to higher temperatures) and knowledge related to the impact of consumer behavior on environmental conservation [87]. In addition to such a classification, the meta-knowledge of how to spread the learned knowledge should be acquired to promote students’ diffusion behavior. The knowledge factor derived from the factor analysis is also acquired in classroom studies. Therefore, providing an educational program for the classroom that can enable the acquisition of such meta-knowledge is required to concentrate the power of the population. In addition, among the factors related to field trip experiences, the self-efficacy and solidarity factors can be also fostered in classroom studies, and our findings imply that promoting these factors contributes to the diffusion of knowledge. The findings of this study are useful for improving classroom study programs designed to promote sustainable development.

The results of the logistic regression analysis showed that altruistic factors, such as the tenderness and prosociality factors, sometimes did not affect driving network externalities and expanding the network. The reason for this is the difficulty in solving the problem. Because social problems are complicated, students are aware that the problem may become even larger if they are involved in solving them. This awareness can be inferred from the result that every explanatory variable has weaker effects on involvement (i.e., direct solving behavior) than other objective variables, and only the knowledge factor among the students’ features factors had a positive effect on cooperation (i.e., indirect solving behavior). That is, when the problem-solving ability does not seem sufficient, students with higher altruism attempt to stay away from social problems. In contrast, the self-efficacy and experiential value factors among field trip experience factors showed a stronger influence than students’ features factors on objective variables. Therefore, focusing on program design to improve students’ self-efficacy and experiential value on field trips might possibly mitigate the tendency of altruistic students to avoid accessing social problems.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

This study observed a phenomenon called the “paradox of communication in sustainable development”. This phenomenon indicates that students with stronger daily communication skills tend to avoid communication about the knowledge that they have learned about sustainable development. Furthermore, this study identified that the tenderness factor does not promote involvement, engagement, and cooperation in solving social problems, and the prosociality factor does not promote cooperation in solving social problems. Future research should explore the causes of these empirically contradictory results. More effective ESD can be provided by clarifying the concrete factors in education programs that lead to these contradictory results.

Although this study clarified the factors that promote driving network externalities and expanding the network, how these factors encourage subsequent university education needs to be explored. Today’s wicked social problems are caused by the structure of human relations and social interactions [88], and stakeholders perceive problems differently depending on their standpoints [89]. When cross-sector stakeholders work together to create momentous social value, the success of the collaboration is strongly influenced by the process of relationship construction [90]. Therefore, further research is needed on the network structure and diffusion process regarding how the effects of network externality expand.

Our findings specify the factors of an ESD field trip that affect students’ behavior for driving network externalities and expanding the network. Although an ESD field trip could be a trigger for some students, this study has a limitation that the data were gathered only using a questionnaire survey on a field trip and effects outside of the field trip were not discussed. A longitudinal study that compares students’ behavior before and after the ESD field trip would be useful for confirming or refuting the findings of this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.Q.H. and Y.I.; methodology, B.Q.H. and Y.I.; software, Y.I.; validation, Y.I. and B.Q.H.; formal analysis, B.Q.H. and Y.I.; investigation, B.Q.H.; resources, B.Q.H.; data curation, B.Q.H.; writing—original draft preparation, B.Q.H. and Y.I.; writing—review and editing, B.Q.H. and Y.I.; visualization, B.Q.H.; supervision, Y.I.; project administration, B.Q.H.; funding acquisition, B.Q.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, grant number 19K20564.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ridilover Inc. for its data collection support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Boni, A.; Calabuig, C. Education for global citizenship at universities: Potentialities of formal and informal learning spaces to foster cosmopolitanism. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2017, 21, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlouhá, J.; Pospíšilová, M. Education for Sustainable Development Goals in public debate: The importance of participatory research in reflecting and supporting the consultation process in developing a vision for Czech education. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 4314–4327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora-Polo, F.; Sánchez-Martín, J.; Corrales-Serrano, M.; Espejo-Antúnez, L. What do university students know about sustainable development goals? A realistic approach to the reception of this UN program amongst the youth population. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora-Polo, F.; Sánchez-Martín, J. Teaching for a better world: Sustainability and Sustainable Development Goals in the construction of a change-maker university. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, W.L.; Shiel, C.; Paço, A.; Mifsud, M.; Ávila, L.V.; Brandli, L.L.; Molthan-Hill, P.; Pace, P.; Azeiteiro, U.M.; Vargas, V.R.; et al. Sustainable Development Goals and sustainability teaching at universities: Falling behind or getting ahead of the pack? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnaur, D.; Svidt, K.; Thygesen, M.K. Developing students’ collaborative skills in interdisciplinary learning environments. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2015, 31, 257–266. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, B.Q.; Hara, T. Analysis of study tour enhancing social concern of high school students to local communities. J. Jpn. Assoc. Rgnl. Dev. Vital. 2019, 10, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ridilover. Ridilover Homepage. Available online: https://ridilover.jp/ (accessed on 8 June 2020).

- Educa & Quest. Educa & Quest Homepage. Available online: https://eduq.jp/ (accessed on 3 August 2020).

- Cherrier, H.; Gurrieri, L. Framing social marketing as a system of interaction: A neo-institutional approach to alcohol abstinence. J. Market. Manag. 2014, 30, 607–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibb, S. Up, up and away: Social marketing breaks free. J. Market. Manag. 2014, 30, 1159–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stead, M.; Arnott, L.; Dempsey, E. Healthy heroes, magic meals, and a visiting alien: Community-led assets-based social marketing. Soc. Market. Q. 2013, 19, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luca, N.R.; Hibbert, S.; McDonald, R. Understanding behaviour change in context: Examining the role of midstream social marketing programmes. Sociol. Health Illn. 2019, 41, 1373–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, M.L.; Shapiro, C. Network externalities, competition, and compatibility. Am. Econ. Rev. 1985, 75, 424–440. [Google Scholar]

- Jucker, R. “Sustainability? Never heard of it!”: Some basics we shouldn’t ignore when engaging in education for sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2002, 3, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, C. Sustainable happiness: How happiness studies can contribute to a more sustainable future. Can. Psychol. 2008, 49, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Emblen-Perry, K.; Molthan-Hill, P.; Mifsud, M.; Verhoef, L.; Azeiteiro, U.M.; Bacelar-Nicolau, P.; de Sousa, L.O.; Castro, P.; Beynaghi, A.; et al. Implementing innovation on environmental sustainability at universities around the world. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corney, G.; Reid, A. Student teachers’ learning about subject matter and pedagogy in education for sustainable development. Environ. Educ. Res. 2007, 13, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, G.; Posch, A. Higher education for sustainability by means of transdisciplinary case studies: An innovative approach for solving complex, real-world problems. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 877–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayles, C.S.; Holdsworth, S.E. Curriculum change for sustainability. J. Educ. Built Environ. 2008, 3, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manteaw, O.O. Education for sustainable development in Africa: The search for pedagogical logic. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2012, 32, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, K. Deep learning and education for sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2003, 4, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdsworth, S.; Wyborn, C.; Bekessy, S.; Thomas, I. Professional development for education for sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2008, 9, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Su, L.; Liu, J. Developing sustainability curricula using the PBL method in a Chinese context. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 61, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viegas, C.V.; Bond, A.J.; Vaz, C.R.; Borchardt, M.; Pereira, G.M.; Selig, P.M.; Varvakis, G. Critical attributes of sustainability in higher education: A categorization from literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 126, 260–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roczen, N.; Kaiser, F.G.; Bogner, F.X.; Wilson, M. A competence model for environmental education. Environ. Behav. 2014, 46, 972–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, S.; Irwin, B. Using e-learning for student sustainability literacy: Framework and review. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2013, 14, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, S.; Pensini, P. Nature-based environmental education of children: Environmental knowledge and connectedness to nature, together, are related to ecological behaviour. Global Environ. Chang. 2017, 47, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, T.; Gericke, N.; Chang Rundgren, S.N. The implementation of education for sustainable development in Sweden: Investigating the sustainability consciousness among upper secondary students. Res. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2014, 32, 318–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinakou, E.; Pauw, J.B.D.; Goossens, M.; van Petegem, P. Academics in the field of education for sustainable development: Their conceptions of sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 184, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnveden, G.; Newman, J.; Verhoef, L.A. Sustainable development and higher education: Acting with a purpose. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, C.; Gericke, N.; Höglund, H.O.; Bergman, E. The barriers encountered by teachers implementing education for sustainable development: Discipline bound differences and teaching traditions. Res. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2012, 30, 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinakou, E.; Donche, V.; Pauw, J.B.D.; van Petegem, P. Designing powerful learning environments in education for sustainable development: A conceptual framework. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zint, M.; Kraemer, A.; Northway, H.; Lim, M. Evaluation of the Chesapeake Bay Foundation’s conservation education programs. Conserv. Biol. 2002, 16, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyburz-Graber, R. Environmental education as critical education: How teachers and students handle the challenge. Camb. J. Educ. 1999, 29, 415–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haigh, M.J. Promoting environmental education for sustainable development: The value of links between higher education and non-government organizations (NGOs). J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2006, 30, 327–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, H. The who, where, and when of social marketing. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2010, 22, 288–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Framing behavioral approaches to understanding and governing sustainable tourism consumption: Beyond neoliberalism, “nudging” and “green growth”? J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 1091–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wymer, W. Rethinking the boundaries of social marketing: Activism or advertising? J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, R. Unlocking the potential of upstream social marketing. Eur. J. Market. 2013, 47, 1525–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Intervening in academic interventions: Framing social marketing’s potential for successful sustainable tourism behavioural change. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 350–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, B.; Kubacki, K. The four Es of social marketing: Ethicality, expensiveness, exaggeration and effectiveness. J. Soc. Mark. 2015, 5, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreasen, A.R. Social marketing: Its definition and domain. J. Public Policy Mark. 1994, 13, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, M. Resilience research and social marketing: The route to sustainable behaviour change. J. Soc. Mark. 2019, 9, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenane-Antoniadis, A.; Whitwell, G.; Bell, S.J.; Menguc, B. Extending the vision of social marketing through social capital theory: Marketing in the context of intricate exchange and market failure. Mark. Theory 2003, 3, 323–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothschild, M.L. Carrots, sticks, and promises: A conceptual framework for the management of public health and social issue behaviours. J. Mark. 1999, 63, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luca, N.R.; Hibbert, S.; McDonald, R. Towards a service-dominant approach to social marketing. Mark. Theory 2015, 16, 194–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szablewska, N.; Kubacki, K. A human rights-based approach to the social good in social marketing. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 155, 871–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenkert, G.G. Ethical challenges of social marketing. J. Public Policy Mark. 2002, 21, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L. Toward a transcending conceptualization of relationship: A service-dominant logic perspective. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2009, 24, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luca, N.R.; Hibbert, S.; McDonald, R. Midstream value creation in social marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 2016, 32, 1145–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainuddin, N.; Gordon, R. Value creation and destruction in social marketing services: A review and research agenda. J. Serv. Mark. 2020, 34, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manikam, S.; Russell-Bennett, R. The social marketing theory-based (SMT) approach for designing interventions. J. Soc. Mark. 2016, 6, 18–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchell, K.; Rettie, R.; Patel, K. Marketing social norms: Social marketing and the ‘social norm approach’. J. Consum. Behav. 2013, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.; Reno, R.R.; Kallgren, C.A. A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Tsujimoto, M. New market development of platform ecosystems: A case study of the Nintendo Wii. Technol. Forecast Soc. Chang. 2018, 136, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenmann, T.R.; Parker, G.; Alstyne, M.W.V. Strategies for two sided markets. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 92–101. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, D.S. Some empirical aspects of multi-sided platform industries. Rev. Netw. Econ. 2003, 2, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagiu, A.; Wright, J. Multi-sided platforms. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 2015, 43, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochet, J.C.; Tirole, J. Platform competition in two-sided markets. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2003, 1, 990–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochet, J.C.; Tirole, J. Two-sided markets: A progress report. RAND J. Econ. 2006, 37, 645–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rysman, M. The economics of two-sided markets. J. Econ. Perspect. 2009, 23, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, M. Competition in two-sided markets. RAND J. Econ. 2006, 37, 668–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I.; Toyama, R.; Konno, N. SECI, Ba and leadership: A unified model of dynamic knowledge creation. Long Range Plan. 2000, 33, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crandall, J.E. A scale for social interest. J. Individ. Psychol. 1991, 47, 106–114. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Gully, S.M.; Eden, D. Validation of a new general self-efficacy scale. Organ. Res. Methods 2001, 4, 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campón, A.M.; Alves, H.; Hernández, J.M. Loyalty measurement in tourism: A theoretical reflection. In Quantitative Methods in Tourism Economics; Matias, Á., Nijkamp, P., Sarmento, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 13–40. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, L.R.; Lewis, C. A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika 1973, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattell, R.B. The scree test for the number of factors. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1966, 1, 245–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carifio, J.; Perla, R. Resolving the 50-year debate around using and misusing Likert scales. Med. Educ. 2008, 42, 1150–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menard, S. Applied Logistic Regression Analysis; Sage: California, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, B.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Prentice Hall: New Jersey, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation modeling with unobservable variable and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen, A.R. Prescriptions for theory-driven social marketing research: A response to Goldberg’s alarms. J. Consum. Psychol. 1997, 6, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, J.D.; Newton, F.J.; Rep, S. Evaluating social marketing’s upstream metaphor: Does it capture the flows of behavioural influence between ‘upstream’ and ‘downstream’ actors? J. Mark. Manag. 2016, 32, 1103–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borden, D.S.; Cohn, S.I.; Gooderham, C. Transitioning “upward” when “downstream” efforts are insufficient. Soc. Mark. Q. 2018, 24, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackstock, K.L.; Kelly, G.; Horsey, B. Developing and applying a framework to evaluate participatory research for sustainability. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 60, 726–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, M.; Michelsen, G. Learning for change: An educational contribution to sustainability science. Sustain. Sci. 2013, 8, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S.A.; Post, J.E. Catalytic alliances for social problem solving. Hum. Relat. 1995, 48, 951–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, A.W.; Dacin, P.A.; Dacin, M.T. Collective social entrepreneurship: Collaboratively shaping social good. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 111, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logsdon, J.M. Interests and interdependence in the formation of social problem-solving collaborations. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 1991, 27, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quélin, B.V.; Kivleniece, I.; Lazzarini, S. Public-private collaboration, hybridity and social value: Towards new theoretical perspective. J. Manag. Stud. 2017, 54, 763–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, B. Conditions facilitating interorganizational collaboration. Hum. Relat. 1985, 38, 911–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koschmann, M.A.; Kuhn, T.R.; Pfarrer, M.D. A communicative framework of value in cross-sector partnerships. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2012, 37, 332–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, J.; Kaiser, F.G.; Wilson, M. Environmental knowledge and conservation behavior: Exploring prevalence and structure in a representative sample. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2004, 37, 1597–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittel, H.; Webber, M. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, S.L. Complexity economics, wicked problems and consumer education. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyton, J.; Ford, D.J.; Smith, F.I. A mesolevel communicative model of collaboration. Commun. Theory 2008, 18, 376–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).