Abstract

Power creates and changes space. Power may be various forms of authority, individual or social structure, complex situations or an unidentifiable force. This study focuses on understanding how power influences a space which is a social product of the exercise of power, thus re-defining power in spatial practices as an extensive introduction to the literature on power. This historical observation study conducts a case review on Seoul Plaza, a socio-political center of downtown Seoul, South Korea. A systematic review of widespread media coverage of the space and its events was performed, using newspaper articles and governmental database search systems for the time period from 1922 to 2016. Believing that power is as an endless structural process of competition and positing in which three social entities, authority, market and people, interplay towards an equilibrium stage of the process, this study concludes that a public space can be formed, transformed or characterized based on outcomes of such power competitions among social entities depending on their social status and how they are displayed.

1. Introduction

How does power influence space? Power creates space. Space is a product and a result of social processes—not as a neutral container of it but rather a tool of thought and action, a means of control, and a production of power [1,2,3]. Power also changes space. The production of space is a continual process of heterogeneous spatio-temporalities while power exists to a greater or lesser degree [2,4]. Space is the history of power, and power shapes all kinds of relationships from a micro- to a more global-level in its spatial practices [5,6].

What is power? How can we define power? Or otherwise, is the definition necessary? Many do not have a clear notion and definition of power, but its consequences are easily recognized [7]. People pursue power for dominating or influencing their relatively powerless counterparts. Common expressions, such as ‘have power’, ‘give power’ or ‘my power’, are used to draw its social, economic and political voice toward realization of power as explicit or implicit forms. The concept of power has been consistently contested throughout history in the understanding of how it works in contemporary societies and was developed as one of the most important organizing concepts in social and political theories [8,9]. Therefore, advancing the definition of power by review and comparison with the existing theoretical approximate concepts will be essential not only for disentangling different and confusing concepts, but also provides a better understanding of the distribution and exercise of power [10].

To understand how power influences space through various social interactions, this article argues that understanding—hence, redefining—the concept of power in the given social and political contexts can offer a reasonable approximation of the processes and consequences of the spatial practice of power and is a useful guide for the existing literature on the study of power. Additionally, from this standpoint, we expect that a better understanding about the relationship between power and space will be deepen in specific relation to sustainability in a complex urban context. The ideas of sustainability and democracy can be interdependent and complementary, and some even argue that the system of democracy and civic participation are among the key factors that underpin the sustainability of a society [11]. When we understand democracy is, in particular, a matter of power and its relations which determine whether democracy can emerge, stabilize, and maintain itself [12], it is worth examining how the pattern of power relations is reflected in our everyday life regarding the sustainability of its society. In this paper, we focus on an urban space as a medium to observe the power dynamics and the influences in our daily life over time.

Therefore, the purposes of this study are (a) to conduct a critical review of the existing definitions, debates and concepts of power (b) to redefine power as a driving force of spatial organization, practice and change in our everyday space, and; (c) further, to conduct an observation on a case study for illustrating the concept of power advanced by this study. Specifically, this study focuses on the different forms of power and social interaction that shape and change a public space, Seoul Plaza, which is one of the most popular open spaces and socio-political centers of Seoul, South Korea.

2. Defining Power in Space

“Space is fundamental in any form of communal life, space is fundamental in any exercise of power” [13].

What is power? Despite discussions over many years, scholars have not yet formulated a statement of the concept of power that is rigorous enough to be of use in the systematic study of this important social phenomenon. Commonly, power is defined in terms of a relationship between people and expressed in a simple symbolic notation [14]. Since the 1950s, social theorists have tried to conceptually formulize and categorize power in order to understand the socio-political phenomena that are believed to be controlled by power [14,15,16]. Similar to the definition provided by the 19th-century philosopher Max Weber, ‘the probability that one sector within a social relationship will be in a position to carry out his own will despite resistance, regardless of the basis on which this probability rests [17]’, social scientists tend to disregard mutually-functioning power relationships by focusing on the comparison between the more and less powerful.

In the 1950s and 1960s, power was commonly understood based on its structure, an ordered and stabilized system as a human institution [18]. Two main streams were established in conceptualizing power based on the perspectives of socialists and pluralists about the source of power. According to Bachrach and Baratz, socialists mainly wondered ‘who rules?’ employing the ruling elite models, whereas pluralists asked ‘does anyone have power?’ [15]. This is also connected to the Weberian sociologists’ concept of power as the ability of one group or person to influence another within a given system [19].

From the pluralists’ perspective, the sociological model of power involved participation through the decision-making process rather than in the top-down institutional core. In the pluralist view, Dahl argued that the elite model was too arbitrary and its evidence was so limiting that it did not cover all the different social cases in terms of social participation [20]. Further, Bachrach and Baratz even expanded Dahl’s scope to include the ‘public face’ considering the possibility that non-participation could have a powerful effect in preventing conflicts from starting [15].

In the 1970s, social scientists challenged the early pluralists like Dahl, who once aimed at A’s influence on B’s conduct. Their focus was widely expanded to examine A’s influence on B’s metaphysical responses, such as shaping preferences, interests and desires—the so called ‘third face’ of power [16,21]. Power was understood as a means of limiting human freedom even in the individual’s psychological terrain in the midst of social relations and social boundaries. Accordingly, in the late 1970s, scholars under new institutionalism started to ask about the ‘why’ of the exercise of power through social actions beyond only asking ‘who’ uses power and ‘how’ it can be used in particular social contexts [16].

Since then, structural power theorists have strengthened the theoretical focus on power relations as shaped by institutional roles and its structural relations, unlike previous students of power-with-a-face’s compelling argument on the dichotomized power structure between powerful agents and powerless actors [8,16,22,23,24]. They have attempted to offer a realistic concept of power with socially structured and enduring capacities for action beyond its empirical causations [22]. Hayward also highlighted the role of constitutive social boundaries to circumscribe all social actions—these social boundaries include rules, norms, and procedures, and also define the fields of social action [16].

In contrast to the structural perspectives of Hayward and others on the source of power, Lukes believed power to be an agent-centered concept [25]. Although the structural relationships between both structure and agency and power were commonly accepted, Lukes emphasized the ability of agents of power and took the moral and political responsibility for their consequences into account [26]. However, Lukes’ concept has been criticized due to the lack of explanation of its structure and the weakness in his analytical framework for the identification of power [10,26].

However, unlike these historical contests and traditional theories on the concept of power, Foucault re-conceptualized it based on the relationship between power and knowledge: power is prior to knowledge and involved in the production of knowledge [5,27,28]. This power-knowledge concept describes a historical transformation in the exercise of power [28,29]. Foucault conceptualized power as a network of social relationships like a mobilizable web—actors desiring outcomes may pull the strings of power to achieve it and all actors are subjected to the power relationship [30]. The actors are produced historically as constituted and correlative elements of power and knowledge [31].

Still, power is often understood as a tool against the powerless and commonly expressed as, ‘who has power?’—similar to the views of the early elitists or Weberian sociologists that focused on how A’s power influences the conduct of B, who would not otherwise act [14]. This view emphasizes the possibility of conflict and antagonism (A overcomes the resistance of B), but relatively ignores the possibility of mutual interests and functional balancing within the integrated social relationship [19]. However, as in previous debates, contemporary researchers support another aspect of power, so-called relational power, characterized by collaboration, sharing and mutuality [32,33,34].

From the debates and theoretical developments on power, we postulate that power can be understood not simply as a possessable control-tool or single entity over the powerless, but rather as being a part or whole of the social network, including social boundaries, such as laws, rules, institutional arrangements, and social identities and exclusions [16]. It is important to consider the structural contexts of power, structure and agency beyond agency-centered perspectives. We also agree upon the structural theorists’ views on the peripheral social agents who can exercise power in an additional capacity in the absence of responsible power agents through social organizing, institutionalization, and even daily life experiences.

The concept of power should not only be tied to the present. We may be able to focus on the current ruling power entity, but not yet discover the whole power structure as power relations are immanent in all social processes [5]. As part of creating a new network or regime of knowledge, power may be viewed as a historical process of conflictive and integrating activities among social actors. Considering the broad and complex capacity of the social network, time dimensions may be crucial for understanding the continuing transformation of social relations, and therefore, will lead us to have a wider lens to move from ‘Who has power, now?’ to ‘How to identify power before, now and after?’.

Focusing on the consequences of spatial practices (i.e., spatial planning and design), it is inevitable to ponder the question of power on what is actually happening as opposed to asking what we normatively would like to see happen [35,36,37]. With the lack of research demonstrating power relations in spatial practices, Flyvbjerg identified the interplay between rationality and power in defining winners and losers from real planning and policy practices [38,39]. Flyvbjerg believed Foucault’s approach, placing conflict and power at its center, was more realistic within a particularistic and contextual tradition, compared with Habermas’s idealistic view of power which was directly linked to judicial institutionalization [38].

Foucault’s interest in space was at the heart of advancing his concept of power. According to Foucault, the way power shapes all social relationships appears as a historical transformation in the exercise of power and the use of space, such as the geography of micro-powers, or ‘geopolitics’ [28,29]. Foucault’s concept is also linked to urban planning perspectives regarding power as an organism which is able to seek, change and define its own reality [39].

Power can also be a structural force made by people who want to use the space in the present [40], or just an immanent but imminent will embedded in urban culture and events in history and, therefore, used in political and spatial decisions in the future by citizens and public officials [41].

3. Redefining Power in Spatial Practice

3.1. Redefining Power

After critically reviewing the most important streams of conceptualizing power, we proposed a theoretical framework for understanding the relationship between power and space based on the assumption that a spatial practice represents certain consequences of the exercise of power and space is a social production by power in the given social and political contexts. Based on existing theories and arguments, in this study we suggest the following four working concepts of power to support our theoretical framework of power in spatial practice.

First, power is not a single entity to be possessed or enacted by an individual or group [42,43]. Rather, power, being a social structure itself, exists in a social relation, in other words, a social boundary or a social network [5,16]. Social relationships are dynamic and thus all social actors are involved with any kind of role in the network, regardless of seemingly being powerful or powerless. The social network or its mechanism may have different forms which are not limited to but may include social organizing, institutionalizing, social activities and the social actors themselves.

Second, power, as a social network, consists of social actors, which are adjacent to each other in terms of their knowledge, behaviors and interactions. The social actors may vary depending on the related social context. Focusing on the spatial exercise of power in this study, we narrowed the broad range of social actors in context of power into authority, market and people (individuals), which have often been found in typical social structures [37,39,44,45,46,47].

Third, the power structure changes over time. Social relationships evolve and change their form over a short to long time span, even many decades. This social structure keeps changing its form like an organism, and balances the mutual interests of authority, market and people [19,29,30,33,39]. We also embrace the agent’s political responsibility from the agent-centered concepts [25], but re-conceptualize it as power gravity in the midst of conflict as a major driving force to form or transform the social structure enacted by social actors, especially those in authority or political sectors. Additionally, the immanent influence from the ‘public face’ or non-participating people should be considered as an imminent force on the future power structure if they have been influenced by other social sectors [15,29,41,48].

Fourth, historical and structural transformation of the exercise of power has a direction toward a production state via conflicts and competition among the social actors. We agree that the dynamic transformation of power tends to be towards the production of knowledge as well as the equilibrium state between the mutual interests of each actor [5,19,27,30]. With the notion of space as a social production of power [1,2,4,6,39,49], we attempt to connect the structural mechanism of power to its spatial practice in terms of the power-knowledge relationship, and to identify the spatial form or performance produced by the exercise of power in an equilibrium state. However, we cannot say that this is a part of the process of rationalization, but rather, there is no general type of equilibrium due to the mutuality in social relationships [39,50].

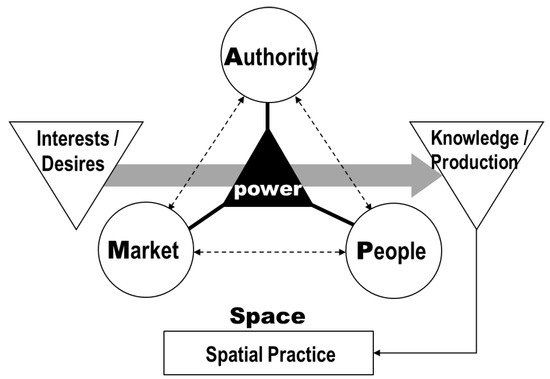

3.2. Power as a Structural Change Model

Based upon the redefined concepts of power mentioned above, this study proposes a theoretical framework for defining power as a structural change model consisting of the dynamic social interplays between three major social actors, authority (‘A’), market (‘M’) and people (‘P’)—typically involved in general spatial practices. Figure 1 shows our argumentation framework which illustrates the structural-change relationship between the social actors in the exercise of power. The relationships move towards the production of knowledge through competitions between the social actors. A space is an outcome of the geopolitical or geosocial knowledge produced by the social relationships and competitions, and power keeps transforming the space over time to a more equilibrium status of the production of knowledge or a more balanced status of the mutual interests between social actors.

Figure 1.

A conceptual framework of power.

The structural change theory was established to understand the nature of the competitive balance issues among agencies, groups and teams, and is also used to interpret progressive institutional changes in the power structure [51,52,53]. Similarly, our power model suggests that the social structure is not a fixed structure but is a process of constant competitions and conflicts over control of the structure and its function between ‘A’, ‘M’ and ‘P’. However, the power structural-change may not achieve any competitive balance during the process but nonetheless moves toward a state of structural equilibrium (Figure 1).

What about the social actors involved in spatial practices? In general, they are all creators, users and occupants of the space. A public space is differentiated from a private space in terms of its nature of ‘openness’ to public access but, in fact, the privatization of a public space is not new in contemporary urban contexts [54]. The form and functions of the space are determined and characterized, either temporarily or continuously, by the characteristics of those who have control over the space. Each social actor has a different view and expectation of the spatial situation and their own interest in trying to change the space. Their ideologies and values may conflict with each other. An authority may need a policy promoting, or limiting, the involvement of other social sectors in the space which meet its political propaganda and ideologies. Market forces use various means of media and communication techniques within/around the space or can attempt to directly privatize the space for maximizing their profits. People will also pursue the freedom of access and use of the space, and may want to voice their social demands or the right of citizenship against authoritarian rules and market-driven policies through occupancy, and sometimes illegal control, of the space. Likewise, as long as the desires and interests of each social actor exist, the social structural changes of power will never end and hence keep influencing spatial practice to an appropriate representation of knowledge and production.

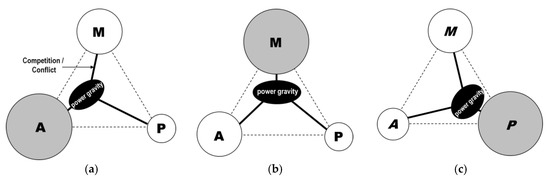

The space reflected by the current power structure may appear to be dominated by a certain social actor, but another change will occur by the imminent and potential conflicts over the place. We therefore again assume that no entity can ‘have power’ but instead can only get closer to ‘the center of the gravity of the power structure’ within a certain time period. Although the formality, intensity and duration of the process of the structural changes of power will vary depending on the society and culture, in this study, we suggest three types of representation in the power structure involving spatial practices: (a) authority-driven, (b) market-driven and (c) people-driven power, and an additional (d) ‘ideal type’ representing a form of the equilibrium relation among the social actors. The following sections will discuss each of these types in detail through observations from a real-world environment.

4. A Case Observation on Seoul Plaza

To refine and reaffirm our definition of power in our argumentation framework, this study conducted historical observations on the study case, Seoul Plaza. In particular, we focused on investigating what forms of power have been developed by the social structure and relationships, and how the plaza has been formed and transformed during the process of the exercise of power throughout the years from 1922 to 2016. We performed a systematic review of multi-media containing a series of collected photographs, newspaper articles, governmental reports, and other literature referring to the chronological spatial practices of Seoul Plaza using a newspaper article database system provided by Naver TM [55] and a governmental database system by the Seoul Metropolitan Government [56], which are full-text Korean language databases. In addition, the observation data derived from the data systems were translated into space-time dimensions.

4.1. Power and Spatial Practice in a Historical Context of Seoul Plaza

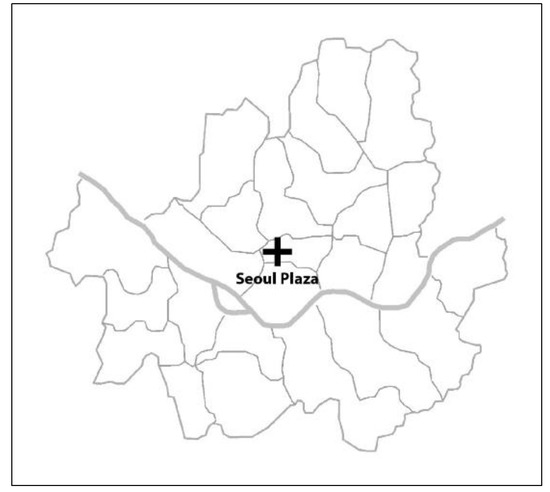

Seoul Plaza is located at the center of downtown Seoul, South Korea and is also known as Seoul City Hall Plaza because of its specific location in front of Seoul City Hall (Figure 2). Originally a part of Taepyeong-ro Street, the north-south main street of downtown Seoul, Seoul Plaza was first formed as a ‘gateway’ space in front of the main gate of Deoksugung Palace, Daehanmun, when the palace was reconstructed in 1905 during the late Joseon Dynasty, and is now used as a central public space that holds various cultural, social and political events for the citizens of Seoul.

Figure 2.

Location of Seoul Plaza. Note. The lines are the municipality boundaries of Seoul.

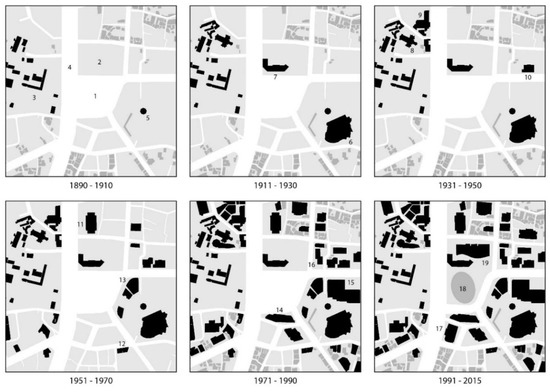

Seoul Plaza has undergone a serious of physical transformations since it was first established in the early 1900s [57,58]. After its surface was paved with asphalt and the city hall building was built adjacent to the site in the 1920s during the Japanese colonial era, Seoul Plaza has served as a major traffic junction of downtown Seoul and a national ‘parade space’ for nearly six decades. Between the 1950s and 1990s, many redevelopments surrounding the site occurred in the context of the post-Korean war reconstruction period, including high-rise hotels and large company headquarter buildings [58]. While serving as a ‘traffic rotary’ in front of the city hall until 2004, there had been little consideration for public access in and around the site and thus pedestrian accessibility became even more restricted due to the continuously increasing traffic volume [59,60]. However, meanwhile Seoul Plaza frequently functioned as a stage for various civic riots as well as political events during dictatorships and through transitional periods leading to democratization. In 2004, Seoul Plaza was re-designed and updated as an oval-grass space with the removal of the traffic rotary, and now still holds numerous social and political events for the citizens of Seoul (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Satellite images of Seoul Plaza in 1972 and 2005. Source: Seoul Metropolitan Government [61].

Beyond the physical changes to Seoul Plaza, we focus on addressing what affected these spatial practices in terms of the social structural changes of power among authority, market and people as mentioned in the above sections. The following sections are summaries and descriptions about the observed spatial practices that represent the major three types of the power structural stage, including authority-driven, market-driven and people-driven power stages (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Illustrations of three types of the power structure. Note: A is authority; M is market and P is people. (a) Authority-driven stage. (b) Market-driven stage. (c) People-driven stage.

Three Types of the Power Structure

- Authority-Driven Power Stage

During the Japanese colonial era (1910–1945), like many other cases in colonized countries during the time of imperialism, the gravity of socio-political power was exceedingly concentrated in the colonial government in order to rule, regulate and control over the citizens. Being against the colonial oppression, the Seoul Plaza site emerged as a place for congregation of patriotic crowds [59], such as the funeral of the Emperor Gojong in 1919 (Figure 5), and consequently, the ‘1st March Independence Movement’ in the same year. Nonetheless, the occupation of people power in the site was sporadic and did not last long because the coercive Japanese colonial policy for the colony had just begun and a number of protesters were jailed and executed by way of exemplary punishment.

Figure 5.

Crowds in the site at the funeral of the Emperor Gojong in 1919. Copyright by Gwangju Folk Museum.

Then, the Japanese colonial government started a series of urban planning and development projects in Seoul, demonstrating the colonial modernity of Japan. In 1912, the Japanese government destroyed almost half of a building in the Deoksugung Palace in order to widen Taepyeong-Ro Street. The surface of the site was first paved with asphalt in 1924 [62] and the city hall building was built adjacent to the site in 1926.

However, the site was used as a common public open space on ordinary days although there was little notion of pedestrian and vehicle segregation. In addition, the government even facilitated use of the space for the public. For example, Gyeong-Seong-Bu, the name of the Seoul city government in the Japanese colonial era, installed a fountain in the middle of the plaza to provide comfort to people during summer [63]. On the other hand, the visualized power of authority was noticeably evident when the site was transformed into a space for government propaganda representing the complete occupation of Japanese imperialism because it was positioned right in front of the city hall, an architectural symbol of the Japanese regime.

There have also been continuous events of national ceremony at the site. On every 3rd November, the plaza became a ritual space to celebrate the Japanese emperor’s birthday [64], and a gathering space for Japanese National Foundation Day on 11th February [65]. Additionally, it sometimes became an outdoor theater projecting films advertising governmental policies to the colony [66]. Moreover, during the Japanese invasion of China and other Asian countries, the site served as a parade-holding space to celebrate a war victory with a mobilized crowd [64]. In general, this period can be considered as an early stage of introducing modernity to this urban space. Yet, due to the characteristics of colonial rule, the reins on the space largely belonged to the government. Actually, it was merely the government’s authority who produced the physical setting at that time. Thus, the social meaning of the space in this period can be defined as the supremacy of, loyalty to, and modernization by authority infiltrating into everyday city life.

Similar marks of this authority-driven stage in the site have also been found in other historical periods. Right after the defeat of Japanese imperialism in 1945, the newly established U.S. Military Government came into power and utilized the space to display governmental authority. For example, hundreds of police gathered at night to practice riot training [67], and held a parade in front of high and distinguished officials [68]. In 1947, there was a ‘majestic’ military parade with a series of tanks and other military hardware for American Independence Day [69,70]. This government also operated the site for state funerals for patriots and national celebrities [71] similar to what was done for the Emperor Gojong during the early Japanese rule.

Especially from the 1960s to 1980s when Korea was under a military dictatorship, the dominance of authority in the site came to the front more obviously and continuously. Governmental ceremonies and propaganda campaigns had become a daily occurrence in the plaza. The triangular piece of the traffic circle in the site served as a platform for the government’s billboards and banners for nearly 40 years. The propaganda displayed often comprised slogans about the regime’s legitimacy, economic advancement of the nation, anticommunism including advertising the superiority of capitalism to North Korea and pro-U.S. campaigns referring to the most powerful allied nation in the Cold War era. Under the Eisenhower administration, the U.S. Government even presented the Seoul Metropolitan Government 64 roses to be planted in the traffic circle in order to celebrate the friendship between Korea and the U.S. [72].

The representation of the power of authority here was articulated in various ways. The site became an outdoor auditorium for regular events of central and municipal governments ranging from city hall’s morning assemblies to national commemoration events (Figure 6). Furthermore, it also held major religious and cultural events. Yearly lighting ceremonies to celebrate Christmas and Buddha’s birthday took place in the traffic circle, along with traditional performances on Korean Thanksgiving and New Year’s Day.

Figure 6.

Mobilized soldiers and citizens at the Korean War commemoration event in 1977. Source: Seoul Metropolitan Government [73].

It also often became a space for mass-education campaigns such as a firefighting skills competition [74], new scientific technology exhibition [75], and a demonstration of new Korean industrial standard products [76]. In this sense, crowd mobilization, whether for the public or a particular section of society, was a frequent means to promote national and governmental events as observed in other autocratic states. The site also often became a central point of any type of street parade. An annual military parade on Armed Forces Day, the 1st of October, took place at the site before the May 16 Square, an alternative governmental exhibition space, was built in 1971 to serve as a venue for military parades and government-led mass events. The Korean national sports team after winning an international game, celebrities who enhanced national prestige abroad and national guests who made a state visit to Korea regularly marched down the street passing through the site [77,78]. Sometimes mobilized citizens even including high school students participated in a march in military gear to honor a patriot [79] or to remember the Korean War [80].

- Market-Driven Power Stage

There is limited evidence on the market’s influence on the site during the Japanese colonial period. However, after independence from Japanese imperialism in 1945, Korea’s state was largely characterized as authoritarian and developed conjoined capital, state, and labor in a virtuous cycle that facilitated rapid industrial growth [81]. Continuous development of the surrounding area has increasingly enlarged the population as well as the volume of traffic which led the site to become one of the most congested circulation spots in Seoul.

The development was intensified between the 1960s and 1990s (Figure 7). Capitalism became another powerful mechanism for imposing control over a space. Thus, the ideology of capitalism was directly represented in the space. A series of major buildings surrounding the site were built in this period such as the Jaeneung Building (1964), New Seoul Hotel (1969), Seoul President Hotel (1971), Seoul Plaza Hotel (1976), Korean Press Center (1985), Geumsaegi Building (1987), and Hanhwa Sogong Building (1998), which have become hosts for the influx of the urban population. This concentration of population and development eventually aroused a desire for public open spaces.

Figure 7.

Spatial changes of Seoul Plaza. Note: 1. Site; 2. City Hall Location; 3. Deoksugung Palace; 4. Taepyeong-ro Street; 5. Hwangudan (Altar of the Sky) (1897); 6. Chosun Hotel (1914); 7. Seoul City Hall (1926); 8. Anglican Church (1926); 9. Bumingwan (Seoul Municipal Assembly Hall) (1934); 10. Mitsui Building (1938); 11. The Seoul Shinmun (1968); 12. Dongyang Building (1968); 13. President Hotel (1970); 14. Seoul Plaza Hotel (1975); 15. Lotte Hotel (1979); 16. Geumsegi Building (1987); 17. Hanhwa Financial Tower (2001); 18. Seoul Plaza (2004); 19. New City Hall (2012).

Correspondingly, due to the large amount of floating population centered around the site, this space has drawn attention from private enterprises as a hot spot for their public relations. However, there was already criticism about what this rapid development might bring about. A lack of consideration for pedestrians in the area signified that the volume of car traffic was already too big to allow pedestrians to freely cross the plaza in the early 1960s [82]. This was when the traffic circle was rebuilt and pedestrian access to the area was limited for better vehicular circulation. Furthermore, there were also a number of complaints that too many advertisements and signboards around the site were causing visual pollution [83].

Besides the surrounding redevelopments, market-driven activities on site have occurred more frequently since the plaza was re-established with an oval-shaped landscape design in 2004. Actually, it was only after the 1990s that a series of public debates emerged to make the space more accessible to pedestrians, and the Seoul Metropolitan Government disclosed a plan to transform the area into a more walkable environment. However, the makeover came to a halt due to budget issues and the impact on traffic [59]. The discussion on the new public space resurfaced in 2002 after this place became a center for street cheering where hundreds of thousands of fervent fans in red shirts, the so called ‘Red Devils’, spontaneously gathered and cheered for the Korean national soccer team during the 2002 World Cup (Figure 8). Ever since this occurred, the place has become a fixture as a cheering ground with official government permission for any type of international sports game, especially when a Korean national team was competing. This provided corporations with ideas on how they could utilize the plaza as their business target. According to the 2002 economic white paper from the Ministry of Finance and Economy in Korea, the economic effect of corporate marketing and promotion during the 2002 World Cup had a value of about 13 billion US dollars [84].

Figure 8.

‘Red Devils’ street cheering in 2002. Source: Seoul Metropolitan Government [73].

Subsequently, right before the 2006 World Cup in Germany, a power game occurred among the city government, Red Devils, and corporate sponsors about the right to the use of Seoul Plaza. A conflict was sparked by the corporate commercialization of the plaza. As SK Telecom (SKT)’s first sponsorship for street cheering in 2002 drew the attention of other enterprises, the government decided to start open bidding on the right to use the plaza on behalf of equal accessibility. As a result, controversy about the commercialization of the space intensified when the right to use the plaza was awarded to the SKT Consortium (SKT, KBS, SBS, Chosun Ilbo, Donga Ilbo, and Seoul Newspapers). Even the Red Devils became suspicious about the sincerity of the organization when they participated in another conglomerate called the KTF Consortium (KTF, Hyundai Motors, and Red Devils) [85,86].

Street cheering in 2006 was a joint product of politics, capital, and the media. While the cheering activities themselves were of a public nature, the characteristics of the space changed from a public to privately-owned domain [59]. After this, many other commercial events have been hosted in the plaza such as a winter skating rink, a luminaire display during the Christmas holiday season, and several major pop music concerts which acquired financial sponsorship from corporate sponsors (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

A pop music concert packed with over 80,000 spectators in 2012. Source: Seoul Metropolitan Government [73].

These events have accelerated transformation of the site from a public to privately held ground. The forces of commercialization in the space and consequential loss of its inherent spontaneous and celebratory function were what Lefebvre meant by the concept of colonialization of everyday life or colonialization of temporal space [1,59].

- People-Driven Power Stage

The site was a traffic circle most of the time prior to its transformation to an open plaza, yet it was already a major stage for public congregation. Public protests and rallies with social and historic significance were continuously held since the end of the Joseon Dynasty such as the All People’s Congress (1898) protesting against foreign intimidation. One of the most remarkable events in the early days was the 1st March Independence Movement in 1919 when Emperor Gojong passed away under Japanese rule. A major protest was held in front of Deoksugung Palace which is the current location of the plaza, and thousands of mourners rallied in a non-violent demonstration that sparked nation-wide protests against the Japanese.

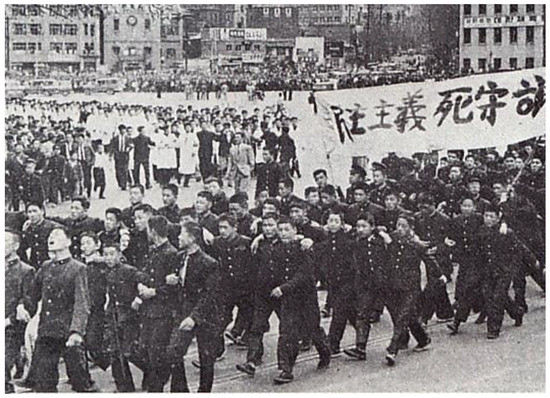

After Korea became independent from Japan in 1945, the area came to bear new symbolic representation as an outlet for upward public voice against persisting political corruption and military dictatorship. At the time of the 19th April Revolution in 1960, thousands of college students and citizens gathered at the area to protest against the fraudulent election (15 March 1960) and call for democracy (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Student demonstration in Seoul Plaza (19 April 1960). Source: Seoul Metropolitan Government [73].

From the 1960s to 1980s, a series of sporadic rallies, great and small, were held against the repeated military governments. However, the 10th June Pro-Democracy Protest in 1987 conveyed the greatest symbolic meaning to the area as an open public square. President Chun’s Fifth Republic tried to have an indirect election by changing the nation’s constitution in an attempt to perpetuate his rule. Hundreds of thousands of citizens including students, office workers and laborers gathered in the street around Seoul City Hall. This grassroots opposition to the dictatorship became a catalyst for attaining a direct presidential election, which has eventually led to the current democratic state. In summary, until the late 1990s, this area was a political rather than a cultural realm, a symbol of division and conflict, and existed and was perceived strictly from the perspective of political interest [59].

However, it began to be recognized as an open public space when the 2002 World Cup Game was held. Street cheerers helped redefine the plaza as a place for spontaneous and temporal celebration not for the nation but for their own beliefs and entertainment. While it was still a traffic rotary for the sake of appearance in the realm under the power of authority and market, this event shed a new light on the plaza as place for individual citizens’ political opinions and festivals. In 2002, a government poll asked 1000 citizens if they wanted a pedestrian-oriented plaza, and 79% agreed [73]. As a result, instead of simply being a pathway for vehicles, a real plaza was established as a domain for civic cultural events which allowed likeminded groups to share and disseminate common cultural agendas.

Furthermore, there was a convincing case on how public-leading self-regulating systems in the space could work to resolve conflict. Upon the criticism that the Red Devils were involved in the commercialization of the plaza after the 2006 World Cup, the Red Devils declared that they would give away the use of the plaza before the 2010 World Cup in South Africa. Nonetheless, this declaration aroused critical public opinion and pressed the city government to become the main management body since the public supported the symbolic significance of the Red Devils in street cheering and did not want to have street cheering without them. As a result, the metropolitan government accepted the Red Devils’ claim that any type of private enterprises’ marketing and advertising activities which attempt to take advantage of the Red Devils’ events should be regulated in the area [85]. Indeed, Seoul Plaza adopted this spontaneity, and the space was finally returned to the public during the 2010 World Cup.

However, there have been frequent conflicts not only between different power entities such as the government, market, and public, but also among social groups with different political perspectives. For example, currently the right to use of the plaza is operated by a permit system from the city government based on specific standards for permission. Some groups of people abuse this permission system since the right of use is given to those who apply first and obstruct the use of other groups with different opinions who plan to hold a rally. In 2008, in order to monopolistically occupy the space and intentionally hinder the use of the plaza for others, some conservative groups applied for and gained permission for a rally in the plaza on 500 days out of 18 months (from 2008 January to 2009 June) while they only held one rally [87].

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Our redefinition of power employs the following fundamental insights of understanding power in spatial practice: power is ‘non-possessable’ but exists as a social relation; power consists of social actors in the relational structure; the power structure keeps changing over time through conflicts and competition among the social actors; and thus, the structural change of power is a process for advancing toward the realization of knowledge constructed from and through social relations.

More specifically, based upon observations on Seoul Plaza, the physical and institutional improvements of the space by those in authority could leverage the public welfare of people and the interest of market participants as social infrastructure. However, Lefebvre argued that the space of bureaucratic politics can be a tool of power through producing and reinforcing social homogeneity [1], and we observed that authority often utilizes the space as a showcase for state power such as mobilization of people, collective enlightenment movements, and propaganda billboard displays particularly when the form of government is a monarchy or dictatorial. On the other hand, the power gravity on market force seeks the capital value of the space regardless of its quality. Additionally, whether it is authority or people, markets tend to collaborate or collude with other entities allowing them to pursuing their own interests—an example can be drawn from the intensive and rapid redevelopments surrounding Seoul Plaza during the industrialization period of Korea, from the 1970s to 1990s, under the institutional support from authority. While the life of the citizens is a major component of the daily landscape of the plaza, the dominance of people’s power in space is distinctively observed as political demonstrations and cultural festivity. As shown by several cultural and political events, however, people-driven activities at the site could attract market makers and stimulate governmental interventions capable of limiting or promoting the activities.

Further, we postulate an ideal stage of the structural change of power as an equilibrium set of competitions and conflicts among the social actors. Having observed the series of processes underlying how three different power entities have played a role in shaping and transforming Seoul Plaza, we noticed the process of the power dynamic appears to be more transparent to the eyes of the observer over time even though there are still numerous struggles occurring in and around the site. One of the important changes at this stage—an institutional compromise between the social actors—is the enactment and amendment process of the ‘Seoul Metropolitan Government Ordinance on Use and Management of Seoul Plaza’ (enacted in 20 May 2004 and amended in December 2007, 28 May 2005 and 27 September 2010). This ordinance laid down detailed standards and rules for all possible activities and uses of Seoul Plaza when this site was re-established as an ‘oval-grass’ open space in 2004. Today this site functions as an urban open space allowing all possible activities from all social actors that meet the ordinance.

Compared to the past, the current state of Seoul Plaza is a good example of this stage. Such institutional and physical transformations of Seoul Plaza, especially in 2014, helped maintain and guarantee the freedom of use and better access to the site for unspecified people. However, at the same time, the authority’s legitimacy was strengthened—13% of people-driven on-site events were not approved by the Seoul Metropolitan Government from 2007 to 2010 whereas 47.3% of the approved events were authority-driven or government-related, including both central and local governments, during the same period of time [88]. According to the ordinance, private commercial activities are fundamentally banned in the site. However, in reality, the sponsorship and participation of private companies have been welcomed and encouraged by most event organizers.

It may be difficult to conclude that Seoul Plaza is at a perfect equilibrium stage of power but fair to say that the structural change process has been advanced further towards less conflict and competition between the actors. This implies that the space can become socially resilient if the power gravity becomes more balanced, and thus more democratic after all. However, this argument assumes that the society to which this kind of public space belongs is only supported by institutional control of authority, ethically sound market forces, and active and participatory citizens.

This study expands the existing knowledge on the study and analysis of power by focusing on the appreciation of the spatial practice of a given structure of power. We hope this paper can bring our discussion of power into a conversation with a wide range of audiences, including policy makers, practitioners, researchers and community members, who question how a given society functions and have the abilities to make a better space for the public good. Additionally, this study may find a common ground with the concept of sustainability, as it is to be considered in a dynamic situation, which will change over time [89]. Unlike other social sustainability studies, mainly focusing on outcome-oriented sustainability factors (either physical and non-physical, and pre-and post-changes), this study can contribute to the literature with a more focus on the drivers, relationships and processes of the changes. In addition, we believe that our overarching concept of the equilibrium stage of power may reflect the notion of social sustainability, which is about the continued viability and functioning of a whole entity of society [89]. Several limitations need to be noted. First, one of the major disadvantages of any observational study using limited multi-media data sources is reliability. However, in order to increase the reliability, all the collected data and analysis results were triangulated through cross-checked agreements between the authors. Additionally, there were limited historical multi-media data about Seoul Plaza before 1960s due to some major events in Korea, such as the Korean War (1950–1953). Interviews and public surveys could be useful to justify our theoretical frameworks. Second, our categorization scheme for addressing the power stage types and the three social actors could be an oversimplification as they should rather be viewed as wider and more complex stages and entities. However, we found that these categories could be simple but commonly accepted, and the distinctions are clear enough to address the interplays among them, not themselves, especially in a way to change the physical forms of Seoul Plaza. We hope that future studies will further explore the more in-depth, intricate and small-scale relationships of power situated in such a public space. Third, the study case may not fully represent all different public space types and power relationships across the world. In the future, we hope to examine the power relationships and changes situated in our everyday spaces which can highlight some important issues about social equity and sustainability of urban communities.

Author Contributions

All authors made significant contributions to manuscript writing efforts. H.J.K. conceived of this research and led the development of the theoretical framework. B.M. led data analysis and the case study, and developed funding support for this research. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Kyung Hee University, grant number 20150512.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Oxford Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1991; Volume 142. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, D. For Space; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, D. Talking of space-time. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2001, 26, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D.L. Agency and community: A critical realist paradigm. J. Theory Soc. Behav. 2002, 32, 163–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucault, M. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972-1977; Pantheon: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. Space, Knowledge and Power; Harvester Wheatsheaf: London, UK, 1986; pp. 239–256. [Google Scholar]

- Salancik, G.R.; Pfeffer, J. Who gets power—And how they hold on to it: A strategic-contingency model of power. Organ. Dyn. 1978, 5, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, T. New face of power. In Rethinking Power; Wartenberg, T., Ed.; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 14–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hoy, D.C. Power, repression, progress: Foucault, Lukes, and the Frankfurt school. Triquarterly 1986, 52, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Hay, C. State of the art: Divided by a common language: Political theory and the concept of power. Politics 1997, 17, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohashi, T. The Analysis of Results of Research into’the Ideal Society’in Japan, Sweden and Bhutan: Using the indicator of Human Satisfaction Measure (HSM). In Proceedings of the 2008 Fourth International Conference on Gross National Happiness, Thimphu, Bhutan, 24–26 November 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rueschemeyer, D.; Stephens, E.H.; Stephens, J.D. Capitalist Development and Democracy; Cambridge Polity: Cambridge, UK, 1992; Volume 22. [Google Scholar]

- Elden, S. Space, Knowledge and Power: Foucault and Geography; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, R.A. The concept of power. Behav. Sci. 1957, 2, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachrach, P.; Baratz, M.S. Two faces of power. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1962, 56, 947–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, C.R. De-facing Power; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, M. The Theory of Economic and Social Organization; Trans. AM Henderson and Talcott Parsons; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, F. Community Power Structure: A Study of Decision Makers; University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, R. The concept of power: A critical defence. Br. J. Sociol. 1971, 22, 240–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, R.A. A critique of the ruling elite model. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1958, 52, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaventa, J. Power and Powerlessness; University of Illinois Press: Urbana Champaign, IL, USA, 1980; Volume 36, pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Isaac, J.C. Beyond the three faces of power: A realist critique. Polity 1987, 20, 4–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, T. Models of power: Past and present. J. Hist. Behav. Sci. 1975, 11, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wartenberg, T.E. The Forms of Power: From Domination to Transformation; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lukes, S. Power and agency. Br. J. Sociol. 2002, 53, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, S.R. Re-structuring Power. Polity 2010, 42, 352–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digeser, P. The fourth face of power. J. Politics 1992, 54, 977–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driver, F. Power, space, and the body: A critical assessment of Foucault’s Discipline and Punish. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 1985, 3, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucault, M. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison; Vintage: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, C.; Leiba-O’Sullivan, S. The power behind empowerment: Implications for research and practice. Hum. Relat. 1998, 51, 451–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townley, B. Foucault, power/knowledge, and its relevance for human resource management. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1993, 18, 518–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreisberg, S. Transforming Power: Domination, Empowerment, and Education; SUNY Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lappé, F.M.; Du Bois, P.M. The Quickening of America: Rebuilding Our Nation, Remaking Our Lives; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Page, N.; Czuba, C.E. Empowerment: What is it. J. Ext. 1999, 37, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann, J. Planning theory revisited. Eur. Plan. Stud. 1998, 6, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flyvbjerg, B. Bringing Power to Planning Research One Researcher’s Praxis Story. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2002, 21, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrechts, L. Planning and power: Towards an emancipatory planning approach. Environ. Plan. C 2003, 21, 905–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flyvbjerg, B. Habermas and Foucault: Thinkers for civil society? Br. J. Sociol. 1998, 49, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flyvbjerg, B. Rationality and Power: Democracy in Practice; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P. Urban Complexity and Spatial Strategies: Towards a Relational Planning for Our Times; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hayden, D. The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History; MIT press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Haugaard, M. Rethinking the four dimensions of power: Domination and empowerment. J. Political Power 2012, 5, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugiagbe, E.O.; Oseye, S. Power to the People or Power in the People, Reflections on the Nigerian Democratic System: Implication for Policy Development. Acad. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 2014, 3, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, G.G.; Biggart, N.W. Market, culture, and authority: A comparative analysis of management and organization in the Far East. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, S52–S94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streeck, W.; Schmitter, P.C. Community, market, state—And associations? The prospective contribution of interest governance to social order. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 1985, 1, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potůček, M. Not Only the Market: The Role of the Market, Government, and The Civic Sector in the Development of Postcommunist Societies; Central European University Press: Budapest, Hungary, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Smismans, S. Civil society and European governance: From concepts to research agenda. In Civil Society and Legitimate European Governance; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2006; pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P. Collaborative Planning: Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies, 2nd ed.; Palgrave Macmillian: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, D. Concepts of space and power in theory and in political practice. Doc. D’anàlisi Geogràfica 2009, 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. The subject and power. Crit. Inq. 1982, 8, 777–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaney, J.A. A coevolutionary model of structural change. J. Econ. Issues 1986, 20, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.B.; Berri, D.J. On the evolution of competitive balance: The impact of an increasing global search. Econ. Inq. 2003, 41, 692–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fort, R.; Lee, Y.H. Structural change, competitive balance, and the rest of the major leagues. Econ. Inq. 2007, 45, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D. The end of public space? People’s Park, definitions of the public, and democracy. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1995, 85, 108–133. [Google Scholar]

- Naver. Naver News Library. Available online: http://newslibrary.naver.com (accessed on 8 May 2016).

- Government, S.M. Seoul’s Database. Available online: http://data.seoul.go.kr (accessed on 8 May 2016).

- Henry, T.A. Assimilating Seoul: Japanese Rule and the Politics of Public Space in Colonial Korea, 1910–1945; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2016; Volume 12. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.-J. The study of urban form in South Korea. Urban Morphol. 2012, 16, 149. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, H. Politics of Spatial Representation and Practice: Applying Lefebvre’s Spatial Triad to Seoul Plaza. Geogr. J. Korea 2007, 41, 123–137. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.-W.; Ahn, S.-H.; Zoh, K.-J. Design proposal of Seoul City Hall Plaza. J. Korea Inst. Landsc. Archit. 2003, 31, 34–45. [Google Scholar]

- Government, S.M. Seoul’s Aerogis Service. Available online: http://aerogis.seoul.go.kr (accessed on 15 August 2016).

- Anonymous. ‘Coal-tar’ Road. The Dong-A Ilbo, 5 September 1924; 3. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Fountain for Plaza, Water Tap for Roadside. The Dong-A Ilbo, 25 May 1935; 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Emperor’s Birthday Ceremony on the 3rd of November. The Dong-A Ilbo, 4 November 1937; 1. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. National Foundation Day on February 11th. The Dong-A Ilbo, 11 February 1940; 1. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Free Movies for People. The Dong-A Ilbo, 16 August 1927; 5. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Police Training for Offensive and Defensive Battle. The Kyunghyang Shinmun, 24 October 1946; 3. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. A Parade in front of High and Distinguished Officials. The Dong-A Ilbo, 17 January 1947; 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. A March-past in the Rain and Fireworks in Namsan Mountain. The Dong-A Ilbo, 5 July 1947; 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Solemn March. The Kyunghyang Shinmun, 5 July 1947; 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. State Funeral for Mr. Jang Postponed to 8th. The Dong-A Ilbo, 6 December 1947; 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. 64 Roses from U.S.A. The Dong-A Ilbo, 24 March 1960; 3. [Google Scholar]

- Government, S.M. Seoul Plaza. Available online: https://plaza.seoul.go.kr/archives/367 (accessed on 5 May 2016).

- Anonymous. Firefighting Skills Competition. The Dong-A Ilbo, 22 October 1961; 3. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Opening for a New Energy Exhibition. The Dong-A Ilbo, 3 December 1966; 8. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. The Second KS Goods Exhibition. Maeil Business News, 23 April 1966; 2. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Welcome Parade in the City Hall Plaza. The Kyunghyang Shinmun, 23 April 1973; 1. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Welcome of a Million Crowd. The Dong-A Ilbo, 16 August 1984; 1. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. High School Students’ Pilgrimage for Admiral Yi Sun-shin in Seoul. The Kyunghyang Shinmun, 26 April 1975; 7. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Seoul Citizen March Wishing Homeland Protection. The Dong-A Ilbo, 25 June 1975; 7. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.-O.; Kim, S.-J.; Wainwright, J. Mad cow militancy: Neoliberal hegemony and social resistance in South Korea. Political Geogr. 2010, 29, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonymous. Unconvenient City Hall Street. The Kyunghyang Shinmun, 2 November 1960; 3. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Too Many Billboards and Promotional Materials. The Dong-A Ilbo, 15 May 1976; 6. [Google Scholar]

- Shinyoon, D. Season of Patriotism, Take Easy on Advertisement. Hankyoreh 21. 7 March 2006. Available online: http://legacy.h21.hani.co.kr/section-021015000/2006/03/021015000200603020599046.html (accessed on 11 November 2016).

- Park, B. The Privatization of street cheering space by a capital: A case study of Hyundai Fan Park 2010. Korean J. Sociol. Sport 2010, 23, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S. Seoul Plaza, Selling Enthusiasm. The Hakyoreh21, 14 March 2006; 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- SBS. 500 Days Permission, 1 Day Use of Seoul Plaza. In SBS 8 O’clock News; Seoul Broadcasting System: Seoul, Korea, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.; Yoon, Y. Half of Seoul Plaza Use Is “Governmental”. Hankyoreh, 4 August 2010; 1. [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey, N.; Bramley, G.; Power, S.; Brown, C. The social dimension of sustainable development: Defining urban social sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 19, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).