Abstract

Presently, the rapid urbanization in contemporary cities in China has resulted in more buildings of low cultural value and high energy consumption. Many traditional Chinese villages exhibit special spaces that have been optimally adapted to the climatic and environmental features of the area using vernacular methods. The buildings in these villages can maintain the environment more sufficiently for the intended programs and consuming a lower level of resources. The construction technics and the artistic features in these spaces are invaluable and inspiring for contemporary architectural practices. This study aims to establish a pedigree of the artistic features exhibited in traditional Chinese villages to support sustainable development. This is to be achieved through thoroughly exploring the spatial design of these villages archived in a big-data resource. The pedigree integrates the dynamics (cultural changes over a certain period of time) and static (spatial features at a fixed time) of how the spaces in these villages have evolved. It is concluded that both a high level of sustainability and exceptional artistic quality have been achieved over a long history in many of these villages where traditional construction methods and design principals were employed.

1. Introduction

By the end of 2018, China’s urbanization rate had reached 59.58% [1], compared with 33.3% in 2000 [2], representing an increase of 23.38% in 18 years. As a consequence, more cities are crowded with new buildings and public spaces of low, if any, architectural identity to showcase the local culture and unique ways of living. This is because the construction industry is more interested in and has always been driven by the economic benefits: Rapid construction, cost-effective technological solutions [3]. Very little attention has been placed on creatively sustaining the cultural and artistic legacy of the local tradition, and ecologically maintaining a harmonized balance between the built and natural environment [4,5]. This explains why little local character can be found in most cities, and the environmental footprint is extremely high [6], a phenomenon nicknamed in the Chinese language as an identical boring face for thousands of cities (“千城一面”). The following three facts are responsible for this situation:

- The traditional culture is not thoroughly understood, therefore, insufficiently appreciated and represented in design.

- There is no suitable method and platform, incentives or resources to support the development plans attempting to address cultural issues.

- High-density cities opt to avoid the time-consuming and financially intensive development by sacrificing the value of traditional culture and building sustainability.

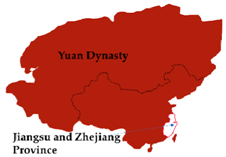

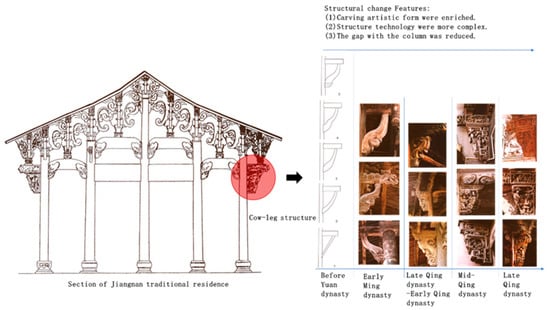

In the Jiangnan Region of China, the construction technology, and the culture of gardens and water towns in traditional villages have resulted in high-quality artistic value, culture, and environmental sustainability [7]. Local materials such as wood, bricks, stones were used in the building envelopes, effectively sheltering the wind and rain while sculptures embedded in these materials have gradually matured to highly recognizable local architectural features and a remarkable cultural symbol in Jiangnan region, a legacy that largely constitutes what is known as Jiangnan Minju (“江南民居”), also called Jiangnan traditional residences or Jiangnan dwellings [8]. For example, throughout a long history, the cow-leg structure [9] has been used to provide support to the roof and to transfer the load to the columns in the traditional architectures in the Jiangnan villages. It was simple and purely designed as a structural component before the Yuan Dynasty (see Figure 1) [10]. Since then, it has gradually evolved into a structural form largely enriched by the artistic and cultural connotations (Figure 1), obviously with historical signature of the dynasties (Ming, Qing, and Republic of China) coming after the Yuan Dynasty: While the structural function is maintained, the artistic expression of this interesting building components has gradually become more complex and detailed, more connected with the local cultures. While effectively maintaining the uniqueness and characters of local culture, these forms are buildable with low-tech construction strategies and are economically cost-effective. As a specific symbol of culture, the traditional residence has a positive influence on construction activities in a long history. Therefore, it is very beneficial for sustainable development if the knowledge, design and build methods that come from traditional culture are employed in contemporary architectural design. This research is aimed to develop this understanding through analyzing the artistic spatial form of Jiangnan traditional villages, and the mechanism of enrichment in which the local culture has been survived continuously for generations.

Figure 1.

The cow-leg structure from Jiangnan traditional village.

2. Literature Review

Most previous research on traditional villages and vernacular architecture in the Jiangnan Region, China focused on producing documentation of the tangible aspects (e.g., spatial form and structural features) [11], and the spiritual aspects (e.g., social and cultural features) [12], through on-site surveys [13,14], literature reviews [15], and modeling [16]. Based on their practice and research on the protection of traditional villages, some researchers have concluded that the survival of these villages and continuous enrichment of the traditional culture are mutually supportive and beneficial, especially in the time of dramatical social changes and/or natural disasters [17,18]. It is also commonly accepted that establishing a pedigree for traditional villages and vernacular architecture is essential for the inheritance, protection, and enrichment of both the tangible and intangible heritage of these villages, in which some primitive and less-intentional forms of sustainable technologies are extremely inspiring for the design of sustainable buildings and cities [19,20]. The heritage value and technological validity exhibited in these villages and architectures can certainly inspire us to design and build for a more sustainable future. Although the positive impacts of the spatial art form on the sustainability in these villages are largely recognized and appreciated, these studies did not sufficiently connect the technology with art in traditional culture, which are two essential properties of a single entity and should not be separated. The philosophic relationship between technology and art from traditional culture applied far beyond architecture, was investigated and thoroughly understood in the time when ancient Chinese language was created, nearly 3000 years ago [21]. An example is the phrase “技艺” (sounds jì-yì means technology appearing in an artistic form, or art implemented using technology) [22]. This phrase has become a term that is referred to as what is used to create the best architecture, villages, and cities. There are not enough studies that succeeded in integrally connecting technology and art, addressing the complex cultural issues related to traditional villages, and producing results to help promote sustainability in contemporary practice based on a thorough understanding of those primitive sustainable measures.

3. Methodology

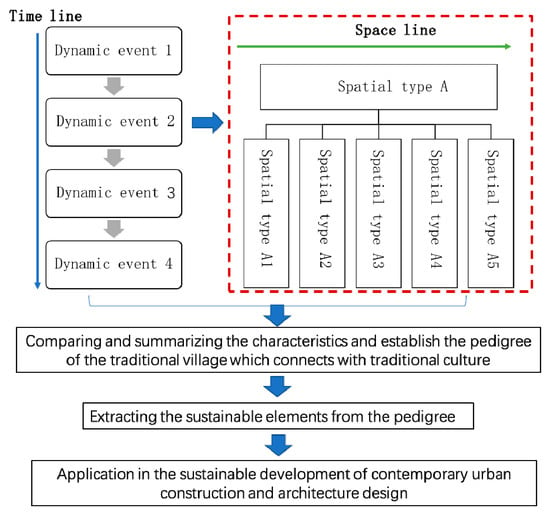

This study employed two methods for establishing an architectural pedigree, which is imaged and visualized features of the traditional culture [23,24,25,26] (Figure 2), namely DSA (dynamic spatial analysis) [27,28] and SSA (static spatial analysis) [29,30]. Through exploring historical milestone achievement along the timeline of architecture with a focus on the interaction between architecture and culture, the DSA method aims to investigate the evolution of architecture in different historical periods with regard to both social, cultural, and technological aspects and to obtain knowledge on how the experience from the past can be adapted for future applications. Information related to the diagrammatic representation of geographical changes, historical construction activities, and the cultural character was collected through historical literature reviews, archives of traditional villages, and big-data analysis. Through DSA, we aimed figure out the reason why Jiangnan traditional culture can develop continuously in the unstable social environment.

Figure 2.

The methodology of research on pedigrees of Jiangnan traditional village.

The SSA method mainly focuses on the types and characteristics of architecture at a certain time, mostly the present time. Information related to the form, spatial quality, the durability of materials and building assemblies, adaptivity of occupancy, and interaction between the built and natural environment was collected through on-site surveys, literature reviews, and big-data analysis. This allowed for a thorough understanding of how and why a certain architecture style can survive for a long time under given local conditions. It provided inspiration and guidance for optimized architecture design: Which design ideas work and which ones do not under the local culture and natural circumstances?

Although some scholars combine dynamic and static methods [31,32], they are focused on the description of the timeline of architecture development and space type, and the research on cultural value extraction from traditional villages is not sufficient. In this study, through a comparative study on the evolutionary processes of typical spatial typology of the traditional villages in Jiangnan Region (includes Shanghai, Southern Jiangsu, Southern Anhui, Northeastern Zhejiang, Northeastern Jiangxi), this study aims to build the pedigree and obtain an in-depth understanding of the residential forms and principles of integrating technology and art in the built environment, which were not sufficiently studied in the previous research. Based on this understanding, it is possible to extract the methods that can be applied to the sustainable development of contemporary urban construction.

4. Dynamic Spatial Analysis: Jiangnan Traditional Village Historical Pedigree

4.1. The Historical Development Features of Traditional Villages in Jiangnan Region

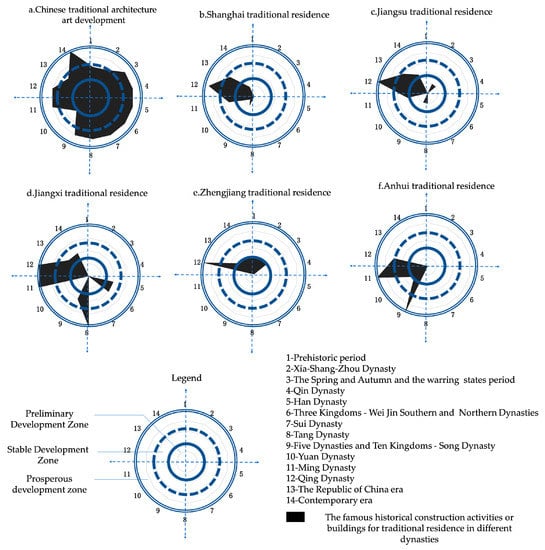

Compared with the history of Chinese architecture, the major traditional residences of Jiangnan Region are more intriguing and remarkable [33,34] (Figure 3, more information see Appendix A: Table A1) with regard to the level of construction activities. The traditional residences are the different types of vernacular architecture in Jiangnan traditional village [35]. Five types of residences have been formed in the Jiangnan Region, namely Shanghai traditional residence [36], Jiangsu traditional residence [37], Zhejiang traditional residence [9], Anhui traditional residence [38], Jiangxi traditional residence [39]. In China, Anhui, Shanghai, Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Jiangxi are five geographical areas in Jiangnan which use their name to identify the different types of traditional residences in the specific area directly [40].

Figure 3.

Jiangnan traditional dynamic spatial pedigree.

As shown in Figure 3a, a high level of diversity has always been a fundamental characteristic of Chinese traditional architectures. Over a long history, a set of traditional residences in the Jiangnan Region has been gradually formed, as summarized as follows:

- As shown in Figure 3b, little change could be found in Shanghai traditional residence before Qing Dynasty (before 1912AD) but significant changes and improvement occurred afterward. This is due to a large number of foreign leased territories in the Shanghai area after the Qing Dynasty, and traditional residences are gradually affected by modern industrial construction techniques [41].

- As shown in Figure 3c, before Yuan Dynasty (before 1368AD), Jiangsu traditional residences had experienced two periods of minor development, during The Spring and Autumn and the warring states period (770–221BC), and Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms-Song Dynasty respectively (907–1297AD). During these two war-tensive periods, the northern population began to move into Jiangnan Region [42], largely impacting the demand for residential buildings.

- Before Yuan Dynasty (before 1368AD), Jiangxi traditional residence experienced two significant developments throughout Han Dynasty (207BC–200AD) and Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms-Song Dynasty (907–1297AD, Figure 3d). This is because Jiangxi is deeply influenced by traditional Confucianism and Academies. These two periods witnessed extensive and frequent cultural blending [42,43].

- Before Yuan Dynasty (before 1368AD), Zhejiang traditional residence experienced a relatively stable development trend (Figure 3e). This is because there were various craftsmen and it was one of the origins of Tenon-mortise structure in early Chinese wood architecture [9].

- Anhui traditional residence had one huge development at Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms-Song Dynasty (907–1297AD, Figure 3f), during that period except for the wartime in Chinese history there were still a lot of Huizhou merchants who effectively bridged the communication between north and Jiangnan [38].

The DSA based pedigree of traditional villages indicates that although the traditional types of residences in the Jiangnan Region featured the traditional Chinese culture and were developed along with Chinese history, the dynamic changes in all periods show significant differences. However, the historical development features of traditional residences still show many commonalities, which allow for traditional culture to survive in an unstable environment and promote the construction technology evolution. Before Yuan Dynasty (before 1368AD) the development of Jiangnan traditional residences was mainly influenced by the migration from northern China. After Ming Dynasty (after 1644AD), the foreign cultures (e.g., southern Asia, Europe) [44] have gradually developed increasing impacts on the design and construction of residences in Jiangnan Region. Industrialization, although limited and sluggishly progressed, largely changed the tectonics, artistic expression, and cultural representation in architecture, resulting in a very long period of transition, through which the Chinese traditional residences were gradually transformed into a modernized version [45,46].

The geographical variation of Jiangnan Region has been mapped from the historical data provided by Chinese History Network [47], which indicates that the development of Jiangnan traditional villages and residences can be divided into four historical periods (Table 1):

Table 1.

The geographical variation of Jiangnan in history.

- From the Xia Dynasty to East Han Dynasty (around 2070 BC–220 AD) in early incubation, when the culture of Jiangnan commenced to incubate and to slowly develop. At the beginning of the Xia Dynasty, the Jiangnan Region was very underdeveloped economically due to the remote location and inconvenient transportation.

- The period between Three Kingdoms and Song Dynasty (220 AD–1279 AD) was when the economy in Jiangnan Region slowly but firmly grew to significant financial power in China. The economic growth rate at Jiangnan Region was higher than that in Northern China which was frequently impacted by the large scale of wars. This also allowed for a steady culture growth in Jiangnan Region.

- From Yuan Dynasty to Qing Dynasty (1279–1911AD) was a period of fast development, the culture of Jiangnan became a symbol of an important ingredient for prosperity because of the stable social environment and the construction of the Grand Beijing-Hangzhou Canal.

- From the Republic of China to the present (1912–present) in the convergence and transformation period, when Jiangnan Region became an economically stable area (includes Shanghai, Southern Jiangsu, Southern Anhui, Northeastern Zhejiang, Northeastern Jiangxi) and one of the cultural centers in China. The sustainability and vitality of Jiangnan culture, including the art of traditional residences, have become significant, attracting enormous research interests.

4.2. The Cultural Sustainability of Jiangnan Villages

Along with the changeover of political power, ruling ethnicity, and cultural switch between dynasties, the defining features and the boundaries of Jiangnan Region have always varied during more than 5000 years ago. Geographically limited within and ecologically adapted to the area south of Yangtze River, the Jiangnan culture has been enriched and sustained by the ideas, theories, and practice of sustainability and adaptivity, although in primitive and not scientifically intentional forms in most circumstances. Especially the five types of traditional residences (including the Anhui residence, Shanghai residence, Jiangsu residence, Zhejiang residence, Jiangxi residences) in five different areas in Jiangnan region have been completely preserved, retaining the ability to serve the contemporary Chinese society. Specifically, this is mainly manifested in two aspects:

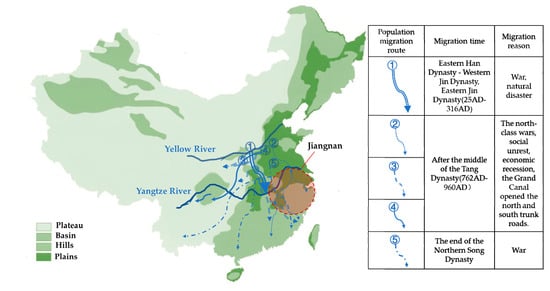

Firstly, in response to the natural disasters and the wars, five large-scale populations migrated from the north to south in the history of China [48] (Figure 4). In this process, Jiangnan Region became an important destination for large-scale migration, it not only enhanced the population and labor force of the region but also stimulated trading via both land and water-ways with Suzhou and Shanghai becoming major trading ports [49]. Among the migrants are bureaucrats, literati, merchants, and craftsmen who brought the necessary cultural development conditions such as advanced knowledge, education, and production technology to Jiangnan Region. After the construction of the Grand Beijing-Hangzhou Canal in Sui Dynasty (581–681AD), the trade between the north and Jiangnan became busy, which was vital for promoting economic prosperity, thus sustaining traditional culture development.

Figure 4.

Five major migrations from north to south.

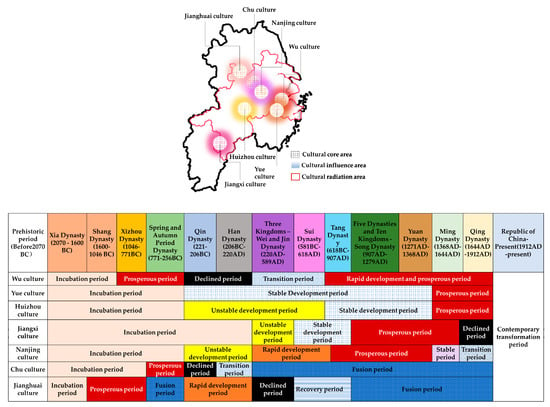

Secondly, cultural diversity was enhanced while multiple cultures could coexist harmoniously and integrate, even compete in a fair and peaceful manner, in the same region of Jiangnan. (Figure 5). These cultures are Wu-Yue culture (Wu culture and Yue culture) [50], Huizhou culture [51], Jiangxi culture [52], Nanjing culture [53], Chu culture (also called Han culture) [54], and Jianghuai culture [55]. The coexistence of these cultures was achieved by the combination of local nationality, the unification of language and characters, and the richness of traditionally diversified construction techniques, which include five types of traditional residences (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Regional culture coexistence.

Figure 6.

The cultural landscape of Jiangnan Region. (a) The coexistence of local nationality. (b) The unification of language and character. (c) Diversified construction techniques.

Although there are differences among the seven cultures, they constitute a stable Jiangnan culture. The relatively stable social environment within the geographical area allowed for sustained economic development, and these factors (including language, local nationality, traditional residences) strengthened cultural sustainability. Especially since the Sui-Tang Dynasty (581–907AD), frequent trades in the Jiangnan Region have enhanced cultural exchanges: Mutual learning and influence, and spread, leading to the maturation of the Jiangnan culture. In history, the division of administrative scope enhanced the degree of association between several cultures and finally established a stable bond in tangible, spiritual, and cultural aspects of a traditional residence.

5. Static Spatial Analysis: Jiangnan Traditional Village Spatial Art Pedigree

5.1. The Spatial Features of Traditional Villages in Jiangnan Region

The forms, sustainable features, and design principles of traditional residences of Jiangnan Region have been identified, illustrated, and classified to show the chronology of the architecture in this area. This is based on the data from archives [56], on-site surveys by the authors, and a comprehensive literature review [9,36,37,38,39,47]. The result shows that five types of traditional residences have gradually formed in traditional Jiangnan villages after a long history of evolution, influenced by the time, location, and political regime (Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6). These traditional residences consisted of a variety of architectural forms and distinguish their characters by their unique spatial art expressions, which include building layout, facade, structure, building materials, and programming. Therefore, five types of traditional residences in the traditional village space of Jiangnan are diverse and inherited through specific design and technology, among them each traditional residence, including different types, as summarized as follows:

Table 2.

Sustainable features in Anhui traditional residences.

Table 3.

Sustainable features in Shanghai traditional residences.

Table 4.

Sustainable features in Zhejiang traditional residences.

Table 5.

Sustainable features in Jiangsu traditional residence.

Table 6.

Sustainable features in Jiangxi traditional residences.

- There are four types of Anhui traditional residences in the southern Anhui region (Table 2). Except that the Huizhou Residence (“徽派民居”) is constructed with the enclosed courtyard, the remaining three types mainly reflect the adaptability to the environment. Especially the Bark residence (“树皮屋”) [57] uses tree barks as the material for the facade, the stone was used to build the foundation for Stone residence (“石头屋”), and the earth clay was used to build the wall in Earth wall residences (“土墙屋”). These materials were acquired from the mountain area in the southern Anhui.

- There are six types of Shanghai traditional residences in Shanghai region, they are called Shanghai Residences (Table 3). The Waterfront residence (“临水民居”) was influenced by the water-shed and/or across the village. Three types of traditional residences, including New Shikumen (“新石库门”), Modern house (“现代民居”), Shikumen (“石库门”), were largely influenced by the western architectures, which emphasized the integration of structure with the facade. That is because Shanghai gradually developed into a highly internationalized city since Qing Dynasty [46]. Two other types of traditional residences, including Courtyard Residence (“合院民居”), Street-facing residence (“临街民居”) influenced by Chinese traditional construction and built near the road which can use for economic.

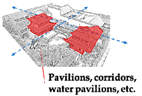

- There are nine types of Zhejiang traditional residences in the northeastern Zhejiang region, (Table 4). Compared with other areas in Jiangnan, this area is most diverse. Moreover, all of them are of a large scale in order to accommodate the large population. In the northeastern Zhejiang, there were very skillful craftsmen and many merchants to promote the construction activities, which had gradually established seven typical shapes of the courtyard [58].

- There are six types of Jiangsu traditional residences in the southern Jiangsu region, it also called Suzhou Residence (Table 5). Four types, including Waterfront Residence (“临水民居”), Multi-way multi-entry Residence (“多路多进民居”) or Large Residence (“大型民居”), Cross-water Residence (“大户民居”), Garden Residence (“园林式民居”) were influenced by a dense network of water-ways which inspired the architecture and was the essential element of landscape around residences that significantly improved the living quality and safety of the residents. It harmonizes the built environment and the water system. Shikumen Residences (“石库门”) could also be found in this area. This area also featured a simplified residence, known as the single-family residence, which was intended to accommodate small families.

- There are five types of Jiangxi traditional residences in the northeastern Jiangxi region (Table 6). Three of them are architectural forms with courtyards, including Courtyard Residence (“合院民居”), Dawu Residence (“大屋民居”), and Huizhou Residence (“徽派民居”), and the Huizhou residence is similar to Anhui traditional residence. It is highlighted by the integration of different architectural cultures found in Jiangnan regions [59]. Two other types, including Waterfront residence (“临水民居”) and Slope residence (“坡地民居”), were inspired by the natural environment, which makes full use of nature to build architecture and its village.

5.2. The Cultural Sustainability of Jiangnan From Traditional Residences

From the SSA based pedigree of Jiangnan traditional residence, these five types of Jiangnan residences show highly creative artistic value and sustainability which are connected deeply with Jiangnan traditional culture. It is mainly reflected in three aspects:

- Sustainability of the natural environment was mainly reflected in the adaptation to the water environment and the utilization of local materials. On one hand, due to the abundant water resources in Jiangnan Region, some buildings, such as waterfront residences, were built around water or water was introduced into the building. Water plays an important role in regulating the macro-climate, and it is also convenient for residents’ daily consumption. Additionally, craftsmen use water to vitalize gardens, courtyards, corridors, and other spaces for daily recreation and enhance the quality of residents’ lives [60]. On the other hand, building materials are extracted from local resources, such as wood for structure and the soil for the walls. Likewise, the roofs in all of the residences are pitched so that rainwater running off the roof can flow into the central courtyard equipped with water storage, maximizing rain-water retention. These strategies are sustainable, especially when the structure of the building is reusable, reducing the damage to nature and wasting resources.

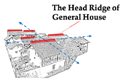

- The sustainability of construction culture was mainly reflected in the design of the courtyard. Most buildings in Jiangnan feature a courtyard and a long-lasting influence of the northern Han culture [61]. It shows the fusion of culture between northern and southern China. In traditional Chinese culture, the courtyard symbolizes the idea of accommodation, respect, harmony, and family value [62]. Meanwhile, this enclosed building form is a vernacular application of the modern passive design strategy. This form also encourages natural ventilation and daylight [63]. The floorplan of most residences is rectangular, favoring the use of wood as building material.

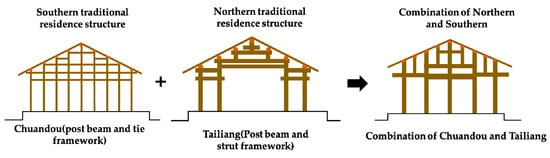

- The sustainability of the construction structure was mainly reflected in structural flexibility. Through this study, it was found that a combination of Chuandou (post beam and tie framework) and Tailiang (post beam and strut framework) is widely used (Figure 7) [64]. Historically, the Tailiang structure was mostly used in the north and the Chuandou in the south [65,66]. The Chuandouis possible due to large wood materials, normally associated with high costs. Meanwhile, because there is no triangular structural element in Chuandou, the overall stability is insufficient. The Tailiang is connected by a large number of columns and rafts, and the indoor space is badly segmented, resulting in low spatial efficiency. Therefore, Jiangnan traditional residences combine the advantages and disadvantages of Chuandou and Tailiang, forming a new structural form, which can satisfy the needs of users and reduce the consumption of wood.

Figure 7. A combination of Chuandou and Tailiang.

Figure 7. A combination of Chuandou and Tailiang.

6. Proposals: Artistic Element Extraction and Application Method

The form of the traditional residences in Jiangnan Region is not only suitable for serving the basic needs of residents’ safety and living quality but also ideal for them to achieve spiritual satisfaction through social events such as entertainment and communication. It shows that Jiangnan traditional culture will continue its development and influence the future. Meanwhile, the culture is realized and spread through technology. Through the process of change from the technical form to the ideology, three principles have been developed and widely employed at both the individual building and village levels, including minimizing the environmental footprint and using the ecological design strategies (“巧用自然”) [67], promoting diversity and accommodating differences (“兼容并蓄”) [68], adaptive reuse of old structures (“以古为新”) [69]. The ideal relationship that this approach aims to achieve between individual architecture and the natural environment, is analog to a tree and a forest: A living being of a large ecological system, mutually depending on and contributing to each other’s healthy survival.

Minimizing environmental footprint and using the ecological design strategies can be implemented through integrating diverse environmental elements into a means of creation, such as channeling water into the building, courtyard space of different themes, facade expression of different building materials [70]. Specific actions and methods include maximizing material recycling, reducing the damage to the natural environment caused by human settlements, rationalizing spatial design based on need and efficiency, improving the infrastructure, and appreciating and emphasizing the art of the natural environment in design. These can help reduce carbon emissions, maximizing the use of ecological resources, and retaining the uniqueness and cultural identity of buildings and villages [71].

Promoting diversity and accommodating differences of cultures largely contribute to the sustainable construction in the rapid modernization. The vast territory of China, together with the different natural climates, result in the different artistic expression forms of village spaces [72]. The choice of cultures and the development of technology jointly affect the logic and expression of art and culture in the spatial design process, and the use of grammar/patterns in artistic construction. The history of Jiangnan has demonstrated that the diversity and variability of culture are both important for its sustainability. Although the concept of culture is abstract, it can be linked to elements such as the environment, design conception, architectural features, landscape, and society, etc. [73]. This study has shown that combining DSA and SSA can be jointly employed to establish an architecture pedigree to highlight the common features shared by different cultures as well as the differences [19]. This pedigree provides designers in contemporary practice with more effective information needed for evaluating and promoting the sustainability of traditional culture.

Adaptive reuse of old structures: Without destroying the relationship between nature and human beings, the historical relics are treated as an integrated system, through appropriate techniques to maintain their physical form and architectural style, and preserve a comfortable indoor environment [74]. At the same time, designers can cooperate with the native residents, attention should be paid to the connotation of villages from the source of consciousness. Especially for the representative arts of important value, such as construction techniques, architectural details, painting, and sculpture, sustainable inheritance can be achieved in the light of educational practice, tours, learning and communication, and effective media and network resources can be utilized. We should inform and digitalize this kind of cultural elements and broaden the scope of artistic inheritance and exchange.

These principles can be employed to enhance the current construction industry in a variety of methods, including direct application, modified application, inheritance and innovation [68]:

Through direct application, art symbols with typical and epochal meanings are recognized and have been used in architecture for a long time. They have become specific architectural symbols and construction cultures. For example, the conceptual design of the traditional courtyard and the site through the layout to work with a climate which allows sufficient solar access, provides wind protection in the wintertime, as well as satisfying the traditional culture and users demanding [75]. Such beneficial design concepts and principles (including the courtyard, horse headwall, sloping roof, covered bridge, etc.) can be evaluated first and then directly used in contemporary residential design and creation as an important element [76]. Through modified application, complicated architectural features established through a long history are simplified or transferred to adapt for use in contemporary architecture design. These features include diverse spatial forms, patterns and textures, and craftsmanship which reflects the local culture. With high artistic values and cultural vitality, some of these spatial forms or structures are complicated, unsuitable or inconvenient for modern lifestyle and aesthetic tendency. Therefore, it needs to be refined, generalized, and redesigned [77]. In order to respond to different external impacts, we need to combine diverse cultures, change our living habits, modernize according to climatic factors, and re-create them according to modern pattern design principles [78].

For inheritance and innovation, the inheritance of art and cultural connotation, and a comfortable lifestyle [79], innovation lies in the combination of contemporary technological ideas to face new social contradictions and environmental problems [80]. Traditional residential culture has its own unique characteristics and cultural connotations. It is necessary to focus on the change of the culture and renew its patterns and features in response to contemporary demands. This innovation is mainly reflected in the use of new design concepts, sustainable building materials, flexible structure, and the combination of different cultures. Therefore, contemporary design needs to tight fit and loose fit the relationship between modern environment and culture, and fully understand the concept of open design for humanity [73].

7. Conclusions and Ongoing Research

The traditional villages and its residences featured in Jiangnan Region are representatives of traditional Chinese culture, and contain abundant historical information and heritage values. The characters of Jiangnan traditional residences contribute to the ability to adapt to the changing environment over a long history. Therefore, in addition to the coordinative means of technology and strategies, exploring the sustainability of Jiangnan villages through pedigree from both dynamic spatial analysis and static spatial analysis is essential, which can transfer the abstract culture to specific elements that are essential for thorough analysis and that have a great significance for the inheritance of traditional village and the practice of the contemporary architecture. As indicated by the pedigrees of Jiangnan traditional villages, the sustainability from its design is diverse and effective. The transformation of Jiangnan traditional villages not only includes tangible (such as the spatial pattern, water system, landscape, structural materials, etc.) but also intangible (such as culture, social, spiritual demanding, etc.), which will inevitably promote the change of traditional village spatial art. This sustainable impact allows the traditional villages and architectures in Jiangnan Region to live on for thousands of years, enriching a distinct cultural identity.

In order to thoroughly understand how the sustainable features exhibited in traditional villages can be adapted for use in contemporary architecture design, ongoing research activities include: (1) Extending the focus of study from individual buildings to the whole village, (2) scientifically studying the performance of the technical solutions and design part in traditional vernacular architecture and village and how they can be modified and applied to cope with more demanding requirements in designing sustainable cities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.L. and Z.L.; methodology, Q.L.; software, Q.L. and Y.Z.; validation, Q.L., Z.L. and Y.W.; formal analysis, Q.L.; investigation, Q.L.; resources, Y.W.; data curation, Y.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.L.; writing—review and editing, Z.L. and D.M.D.; visualization, Q.L. and Y.Z.; supervision, Z.L. and Y.W.; project administration, Y.W.; funding acquisition, Y.W.

Funding

This research was partially funded by (1) Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Construction of the People’s Republic of China “The Research on the artistic value of Chinese traditional villages”, grant number [Building a village NO. [2017]26]; (2) Jiangsu education department, China “Research on the Environmental Space Art Value of Traditional Villages in Jiangnan”, grant number [KYCX18_2481]; (3) Mitacs, Canada “Comparative research on sustainable construction techniques of vernacular architectures in Ontario, Canada, and Jiangnan, China” grant number [IT14936]. The APC was funded by [Building a village NO. [2017]26].

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Construction of the People’s Republic of China, Jiangsu education department, China and Mitacs, Canada.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The historical development information for Jiangnan traditional dynamic spatial pedigree.

Table A1.

The historical development information for Jiangnan traditional dynamic spatial pedigree.

| a. Chinese Traditional Architecture Art Development | b. Shanghai Traditional Residence | c. Jiangsu Traditional Residence | d. Jiangxi Traditional Residence | e. Zhejiang Traditional Residence | f. Anhui Traditional Residence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Prehistoric period | The ancient architecture style appeared, including: ①Nest Houses (in north of China); ② Cave Houses (in south of China); ③ Space for sacrifices or public events. | — | — | — | The ancient Nest Houses appeared: ①Hemudu Site | — |

| 2-Xia-Shang-Zhou Dynasty | The early principles for construction appeared, including: ①Built Ground Houses (cave houses were upwards, and the nest houses were downwards); ②Use the symmetrical and regular settlement space (in the north of China); ③ The specific level of spatial order. | The culture had an impact on architecture: ①Architectural technologies and principles are influenced by the North of China and Wu culture. | Early construction culture appeared:① Craftsman constructed traditional residences in Xiangshan area. | The culture had an impact on architecture: ①Architectural technologies and principles are influenced by the North of China. | The ancient Nest Houses appeared: ①Stilt House (干栏式建筑). | The culture had an impact on architecture: ①Architectural technologies and principles are influenced by the North of China and Hui culture. |

| 3-The Spring and Autumn and the warring states period | The architectural form began to change: ① The scale of buildings became bigger; ② Used bricks, soil, wood as building materials; ③ Defensive walls and moats appeared in city area; ④ Workshops, markets appeared around road space. | — | Large scale architectural palace appears: ①Gusu palace. | — | Built Ground House: ① Thatched House. | — |

| 4-Qin Dynasty | The public buildings appeared, including ①Palace; ② Pray temple; ③Tower; ④ Royal garden. | — | — | — | — | — |

| 5-Han Dynasty | — | — | Taoism building built: ①Qing palace. | Built Ground House: ①Brick wall House. | — | |

| 6-Three Kingdoms-Wei Jin Southern and Northern Dynasties | The Ancient Silk Road promoted the changes in traditional architectures, including: ① Color painting; ② Glass materials; ③ Private gardens; ④ Buddhism sculptures. | Early courtyard residences appeared, including: ① Luji House; ② Erlu Caotang House; ③ Erlang Reading House. | Traditional garden built: ① Pijiang garden. | Temple built: ① Yulong palace. | — | — |

| 7-Sui Dynasty | Large scale buildings appeared, including: ①Buddhism buildings; ②Taoism buildings; ③Temple; ④Memorial buildings. | — | — | — | — | Palace built: ① Nanjiao palace. |

| 8-Tang Dynasty | — | Successfully applied painting style to architectural sculpture: ① Baosheng Temple. | Buddhism buildings built: ① Tengwang Pavilion; ② Qiyin temple. | — | — | |

| 9-Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms - Song Dynasty | Architecture culture became diversity, including: ① Confucianism affected the symmetric layout of buildings; ② Courtyard space appeared inside the house; ③ Architecture decoration became complex; ④ The book ③ titled Chinese Architecture rules gave a standardized explanation for the process of traditional architecture. | Built ancient tower, including: ① Songjiang Square Tower; ② Longhua Tower. | Formed an organization of construction craftsmen: ① Xiangshan craftsmen. | The architecture of classical college built: ① Donghu classical college. | — | Diversity architectures built: ① Changqing Buddhism tower; ② Junpei garden; ③J inzi temple. |

| 10-Yuan Dynasty | The traditional architectures were influenced by religious cultures, including: ① Tibetan Buddhism; ② Islam. | Built a large bureaucracy house: ① Xian yi House. | — | — | — | Tombs show traditional forms of residence: ① The architectural stone carving in tombs. |

| 11-Ming Dynasty | Construction showed diversity in many aspects: ① The central axis space layout method, which is mainly based on the capital city, is widely used; ②Combined with the landscape, buildings such as clock towers, drum towers, and tablet pavilions became popular in the city area; ③There is a famous Chinese architectural style called “Style Lei” (样式雷); ④ A large number of books related to building construction were finished, such as “Luban classics” (鲁班经), “Building the Law” (营造法原), “Yuanye” (园冶), etc. | Built traditional residences with a private garden, including: ① Paradise garden; ② Xieyuan House; ③ Nan Chunhua House; ④ Lanrui House; ④ Baosu House. | Famous construction craftsmen appeared: ① Kuangxiang, who participated in the construction of the Forbidden City; ② Jicheng, who wrote the “Yuanye” for building a traditional garden. | Temple for sacrificing built: ① Zeng Temple in Jingxi; ② Yangchun ancient temple. | — | Traditional architectures built: ① Leshan House; ② Daguan pavilion. ③ Rebuilt of Daguan pavilion. |

| 12-Qing Dynasty | A large number of private gardens were built, including: ① Yu garden; ② Luxiang garden; ③ Duhe garden; ④ Rishe garden; ⑤ Qiuxia garden; ⑥ Zuibai pond garden; Built large scale traditional residences, including: ⑦ Panen House; ⑧ Shuyi House; ⑨ Feiye House; ⑩ Nei shidi House. | Diverse construction activities, including: ① Lujin built the Ou garden; ② Wen Zhenheng wrote the book “Zhang Wu Zhi (On Superfluous Things)”; ③ Gu Wenbing built Yi garden; ④ Ziyi craftsmen organization established. | Temple for sacrificing built: ① Temple of Confucius in Pingxiang; ② Liu temple; | Construction showed diversity in many aspects: ① Wood carving for decoration; ② Horse hand wall; ③ Building façade. | Diversity architectures built: ① Zhushan classical college; ② Tangyue Archway group. | |

| 13-The Republic of China era | Western industrial construction spread in China: ① Application of building materials such as cement, steel, and iron; ② Layout forms began to simplify; ③ Chinese and Western culture combined buildings are widely used. | Built Chinese and Western combined residences, including: ① Huang Qingnian House; ② Taojia House; ③ Ying Youmu House; ④ Yang Hongsheng House; ⑤ Zhong House; ⑥ Chen Guichun House. | Famous construction projects: ① Built Plum blossom pavilion; ② Built Lingyan mountain palace;③ Rebuilt the Yuhan House. | Built Chinese and Western combined residences, including: ① Zhangxun Mansion. | Formed an organization of construction craftsmen: ① Dongyang craftsmen. | — |

| 14-Contemporary era | Multiculturalism promoted the revolution of architectures: ① High-rise building spread in the urban areas; ② The architectural decoration is simplified; ③ Traditional architecture begins to disappear; ④ Artificial intelligence begins to combine with building technology; ⑤ The city scale begins to expand. | There are two architecture style widely used in traditional villages, including: ① Shi Kumen/ Chinese and Western combined residences; ② Modern House/ Garden House. | The Jiangsu traditional garden built in foreign country: ① Su garden (built in America); ② Yuxiu garden (built in Singapore). | Traditional village rebuilt: ① Jinxi village. | A book related to Zhejiang traditional residence was published: ① Eastern Residence Legend Zhejiang Dongyang Residence. | Famous construction projects: ① Chuhua garden (built in German); ② The protection project of Hongcun in Xiexian. |

References

- Xinhua News Agency China’s Mainland at the End of 2018, the Total Population is Close to 1.4 Billion. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/shuju/2019-01/21/content_5359797.htm (accessed on 23 April 2019).

- National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China Census Urbanization Rate (%). Available online: http://data.stats.gov.cn/search.htm?s=2000年城镇化率 (accessed on 23 April 2019).

- Heikkila, E.J. Three questions regarding urbanization in China. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2007, 27, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Kesteloot, C.; Cook, I.G. Theorising Chinese urbanisation: A multi-layered perspective. Urban Stud. 2015, 52, 2564–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, G. The open and adaptive tradition: Applying the concepts of open building and multi-purpose design in traditional Chinese vernacular architecture. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2011, 10, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Wu, L.; Cook, I. Progress in research on Chinese urbanization. Front. Archit. Res. 2012, 1, 101–149. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, G.Z.; Gordon, C. Jiangnan: Views of a Contemporary Chinese Water Town. Cross Curr. East Asian Hist. Cult. Rev. 2016, 20, 127–135. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Pu, X.; Wang, R.; Zeng, Y.; Qi, X. A Study on Closed Halls in Traditional Dwellings in the Jiangnan Area, China. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2018, 15, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F. Eastern Residence Legend Zhejiang Dongyang Residence; Tianjin University Press: Tianjin, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chun, Q.; Jin, H.; Dong, Y.; Hua, Y.; Han, Y. Research on Mechanical Properties of Dingtougong Mortise-Tenon Joints of Chinese Traditional Hall-Style Timber Buildings Built in the Song and Yuan Dynasties Research on Mechanical Properties of Dingtougong Mortise-Tenon Joints of. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2019, 2, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wei, Y. Analysis of Water Environmental Space in Ancient Villages in Huizhou in China. J. Landsc. Res. 2012, 4, 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, L. One thousand years of historical relics: The Huizhou Documents. J. Mod. Chin. Hist. 2016, 10, 248–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Zhang, M.; Qing, Y.; Li, Y. Village resettlement and social relations in transition: The case of Suzhou, China. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2019, 41, 269–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J. Transcending the limitations of physical form: A case study of the Cang Lang Pavilion in Suzhou, China. J. Archit. 2016, 21, 691–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J. Negotiating Urban Space: Urbanization and Late Ming Nanjing by Si-yen Fei (review). China Rev. Int. 2019, 19, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.Y. Mapping Modernity in Shanghai: Space, Gender, and Visual Culture in the Sojourners’ City 1853-98; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L. The Value and Inheritance of Traditional Residence; China Building Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, X.; Ye, R.; Liu, X.; Han, G. Architectural planning and design based on the protection, development of rural folk custom ecotourism. Open House Int. 2018, 43, 88–92. [Google Scholar]

- Qing, C. Structure and Prospective of Chinese Vernacular Architectural Pedigrees an Objective Based on a Systematic Study of Sample Preservation and Holistic Regeneration. Archit. J. 2016, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, D. The Establishment of Chinese Traditional Villages. World Archit. 2014, 6, 104–107. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D. A Philosophy of Chinese Architecture: Past, Present, Future; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhen, L. A Comprehensive Study on Building Construction of Vernacular Architecture in the Greater Jiangnan Region Its Implications, Paths and Methods. Archit. J. 2016, 2, 78–83. [Google Scholar]

- Van Eck, C. The Style Empire and its Pedigree: Piranesi, Pompeii and Alexandria. Archit. Hist. 2018, 6, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goad, P. Constructing Pedigree: Robin Boyd’s “California-Victoria-New Empiricism” Axis. Fabrications 2012, 22, 4–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser Rabbat The Pedigreed Domain of Architecture: A View from the Cultural Margin. Perspecta 2017, 44, 6–11.

- Rudofsky, B. Architecture without Architects: A Short Introduction to Non-Pedigreed Architecture; University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, S.; Liu, S. Reserch On The Native Elements Of The British Architectural Technology Aesthetic Pedigree. Archit. J. 2013, A2, 116–119. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, J.-H. Review: A Genealogy of Tropical Architecture: Colonial Networks, Nature and Technoscience. J. Soc. Archit. Hist. 2017, 76, 551–554. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y. A Pedigree Study On The Wooden Bracket Of Vernacular Architectures In Southeast Coast Of China. Archit. J. 2016, A1, 103–107. [Google Scholar]

- Philippou, P. Cultural buildings’ genealogy of originality: The individual, the unique and the singular. J. Archit. 2015, 20, 1032–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehand, A.J.W.R.; Gu, K. Urban conservation in China: Historical development, current practice and morphological approach Urban conservation in China Historical development, current practice and morphological approach. Town Plan. Rev. 2019, 78, 643–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y. Regional Genealogy, The Evolution of Lingnan Region Modern Architecture. Time Archit. 2015, 5, 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhardt, N.S. Chinese Architecture; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, S.; Fairbank, W. A Pictorial History of Chinese Architecture: A Study of the Development of its Structural System and the Evolution of its Types; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, C. Renovation of Traditional Water Villages in Jiangnan: A Casa study of Renovation Planning of Wenchang Village. J. Landsc. Res. 2017, 9, 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Denison, E.; Ren, G.Y. Building Shanghai: The Story of China’s Gateway; Wiley-Academy: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, R.S. The Ancient City of Suzhou: Town Planning in the Sung Dynasty. Town Plan. Rev. 1983, 54, 194–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deqi, S. Anhui Traditional Residence; China Building Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Zhongrong, R. Study on the Inheritance of Landscape Culture in Traditional Ancient Province. J. Landsc. Res. 2015, 7, 64–66. [Google Scholar]

- Junqing, D. Jiangnan Residence; Shanghai Jiaotong University Press: Shanghai, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne Bracken, G. The Shanghai Alleyway House: A Vanishing Urban Vernacular/Gregory Bracken; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yü, Y.-S. Chinese History and Culture: Sixth Century B.C.E. to Seventeenth Century; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, B.; Kuang, H.; Zhang, L.; Zou, L.; Xie, X. Correlation between Ancestral Temple Worship Sacrifice Culture and Clan Etiquettes in Traditional Settlements of Jiangxi Province. J. Landsc. Res. 2016, 8, 42–44. [Google Scholar]

- Dardess, J.W. Ming China, 1368-1644: A Concise History of a Resilient Empire; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yü, Y.-S. Chinese History and Culture: Seventeenth Century Through Twentieth Century; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Arkaraprasertkul, N. Gentrifying heritage: How historic preservation drives gentrification in urban Shanghai. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2019, 7258, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China History Network Chinese History Maps. Available online: http://lishi.zhuixue.net/ditu/ (accessed on 25 April 2019).

- Weng, L. Spatial Distribution of Traditional Chinese Villages and Factors Affecting Their Distribution. J. Landsc. Res. 2019, 11, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- History, C. From Suzhou To Shanghai: A Tale Of Two Systems. J. Chin. Hist. 2018, 3, 79–107. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.; Xu, W. Interpreting the Inheritance Mechanism of the Wu Yue Sacred Mountains in China Using Structuralist and Semiotic Approaches. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y. Locality, Literati and the Imagined Spatial Order: A Case of Huizhou, 1200–1550. J. Song Yuan Stud. 2019, 42, 407–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H. Text and Power: A study on Local Gazetteers of Wanzai County of Jiangxi Province from the Qing Dynasty to the Republic of China; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 4, ISBN 1146200900. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X. From Imperial City to Cosmopolitan Metropolis: Culture, Politics and State in Late Ming Nanjing. Ph.D. Thesis, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie, C. Defining Chu: Image and Reality in Ancient China. J. Asian Stud. 2000, 59, 990–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Wang, X.; Zhu, C.; Zhang, G.; Li, F.; Li, L.; Li, S. Ancient culture decline after the Han Dynasty in the Chaohu Lake basin, East China: A geoarchaeological perspective. Quat. Int. 2012, 275, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinese Traditional Village Protection and Development Research Center Chinese Traditional Village. Available online: http://www.chuantongcunluo.com/eng/ (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Construction of the People’s Republic of China. Analysis and Inheritance of Traditional Chinese Architecture Anhui; China Building Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2016.

- Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Construction of the People’s Republic of China. Analysis and Inheritance of Traditional Chinese Architecture Zhejiang; China Building Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2016.

- Hao, H. Jiangxi Traditional Residence; China Building Industry Press: Beijing, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Guo, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Q. Enlightenments of “White Space” in Traditional Chinese Painting on Landscape Architecture Design. J. Landsc. Res. 2013, 5, 79–82. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Q.; Guo, Q. The Formation and Early Development of Architecture in Northern China. Constr. Hist. 2001, 17, 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D. Courtyard Housing and Cultural Sustainability: Theory, Practice, and Product; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 2003; ISBN 1840643382. [Google Scholar]

- Gou, S.; Li, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Nik, V.M.; Scartezzini, J.L. Climate responsive strategies of traditional dwellings located in an ancient village in hot summer and cold winter region of China. Build. Environ. 2015, 86, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, B.; Jiang, Y. Flexibility of traditional buildings and craftsmanship in China. Open House Int. 2011, 36, 20–31. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, Z. Traditional Chinese wood structure joints with an experiment considering regional differences. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2014, 8, 224–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Park, S. Tectonic traditions in ancient chinese architecture, and their development. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2017, 16, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M. An explorative study of the ecological design of residence architecture in Ming and Qing dynasties in Yangzhou. MATEC Web Conf. 2017, 119, 01057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street, P.; Xie, J.; Heath, T. Conservation and revitalization of historic streets in China. J. Urban Des. 2017, 22, 455–476. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, X.; Li, Y. Promotion and Abandonment on the Traditional Local Residence in Northern Jiangsu during the New Rural Construction Sustainable Development of Urban Infrastructure. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 255, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Almodovar-Melendo, J.M.; Cabeza-Lainez, J.M. Environmental features of Chinese architectural heritage: The standardization of form in the pursuit of equilibrium with nature. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wu, Æ.J. Sustainable landscape architecture: Implications of the Chinese philosophy of “unity of man with nature” and beyond. Landsc. Ecol. 2009, 24, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, G.; Chen, S. Exploration of the Protective Development Model of Ancient Towns in Metropolitan Suburbs: A Case Study of Xinchang Ancient Town in the Pudong New Area of Shanghai. J. Landsc. Res. 2017, 9, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport, A. Culture, Architecture, and Design; Locke Science Publishing Co., Inc.: Chicago, IL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Cao, C.; Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Chen, B.L.; Li, S. The Evolution of the Timber Structure System of the Buddhist Buildings in the Regions South of the Yangtze River from 10th–14th Century Based on the Main Hall of Baoguo Temple. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2019, 13, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soflaei, F.; Shokouhian, M.; Zhu, W. Socio-environmental sustainability in traditional courtyard houses of Iran and China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 69, 1147–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Bellido, C.; Pulido-Arcas, J.A.; Cabeza-Lainez, J.M. Adaptation strategies and resilience to climate change of historic dwellings. Sustainability 2015, 7, 3695–3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misnat, N.; Surat, M.; Usman, I.M.S.; Binti Ahmad, N. Re-Adaptation of Traditional Malay House Concept as A Design Approach for Vertical Dwellings Malays. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bambang, W.; Ari, S.; Susilo, K.; Widya Fransiska Febriati, A. Cultural Approach of Sustainability in Dwellings Culture Riparian Community Musi River Palembang. DIMENSI (J. Archit. Built Environ.) 2016, 43, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhang, D. New courtyard houses of Beijing: Direction of future housing development. Urban Des. Int. 2006, 11, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. Juer Hutong New Courtyard Housing in Beijing a Review from the Residents’ Perspective. Int. J. Archit. Res. ArchNet-IJAR 2016, 10, 166–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).