Abstract

Durum wheat (Triticum durum Desf.) underpins semolina value chains in water-limited regions, yet Peru remains import-dependent due to constrained local adaptation. We evaluated eleven elite lines plus the commercial variety ‘INIA 412 Atahualpa’ across three contrasting semi-arid sites in Arequipa (Santa Elena, San Francisco de Paula, Santa Rita) during 2023–2024 to identify genotypes maximizing performance and stability. Grain yield, thousand-kernel weight (TKW), hectoliter weight, and plant height were analyzed with combined analysis of variance (ANOVA), the additive main effects and multiplicative interaction (AMMI) and genotype and genotype-by-environment (GGE) biplots, complemented by AMMI stability value (ASV) and weighted average of absolute scores and best yield index (WAASBY). Grain yield and hectoliter weight showed significant genotype × environment (G × E) interaction, while plant height was driven mainly by genotype and environment with limited interaction. For grain yield, AMMI (PC1: 55.2%) and GGE (PC1 + PC2: 90.2%) revealed crossover responses and three practical mega-environments: TD-053 “won” at San Francisco de Paula, TD-037 at Santa Elena, and TD-033 at Santa Rita. Additionally, WAASBY-integrated rankings favored TD-033 (93.7%) and TD-014 (84.72%), followed by TD-026/TD-020 (>57%), whereas TD-062 (9.1%) and TD-043/TD-061 underperformed. Quality traits highlighted TD-044 and TD-014 for high hectoliter weight and TD-014/TD-062 for high TKW with contrasting stability. Overall, TD-033 and TD-014 were adaptable across environments, providing selection guidance to strengthen Peru’s durum breeding pipeline under climate variability.

1. Introduction

Wheat (Triticum spp.) is a cornerstone of global food security and constitutes the most extensively cultivated cereal globally, providing approximately 55% of the world’s carbohydrate intake and 21% of its food calories [1], yet its value chains hinge on two biologically and technologically distinct species: durum and common (bread) wheat [2,3].

Durum wheat (Triticum durum Desf.; AABB, 2n = 4x = 28) produces very hard, vitreous kernels that mill into yellow-amber semolina rich in carotenoids, delivering strong but relatively inelastic gluten ideal for pasta and couscous [4,5]. Agronomically, durum wheat is traditionally favored in Mediterranean and other semi-arid systems, where it adapts well to heat and limited water availability. In regions facing heat and water constraints, identifying durum genotypes that combine competitive yield with stable semolina quality is therefore a strategic breeding priority [6,7]. In contrast, Common wheat (T. aestivum L.; AABBDD, 2n = 6x = 42) spans soft–hard classes, is milled chiefly into fine flour, and forms extensible gluten networks suited to leavened breads [1,8].

Despite South America’s agricultural capacity, a marked supply–demand gap persists due to the internal demand for grains [9]. In particular, Peru harvested barely 0.20 Mt of mostly soft wheat in 2024/2025 yet imported more than 2 Mt to satisfy domestic demand, leaving local farmers with less than a 20% market share and exposing consumers to external price volatility [10].

In recent decades, wheat yields in Peru have shown an upward trend, particularly in highland regions such as Arequipa, La Libertad, Junín, Cusco, and Ayacucho. In particular, Arequipa has consistently achieved the highest productivity, reaching a national record of 7.12 t ha−1 in 2013, which is nearly three times higher than the maximum yield reported in Junín (2.4 t ha−1 in 2015). However, by 2021, Arequipa and Junín accounted for only 6.4% and 3.3% of total national production, respectively, due to their limited harvested area (1.7% and 2.4%). Expanding the agricultural frontier in the coastal valleys, where climatic conditions are more favorable, could enhance national self-sufficiency if the mean yield of 6.78 t ha−1 obtained in Arequipa between 2012 and 2021 were replicated nationwide [10]. These trends highlight the strong influence of local adaptation and environmental factors on wheat productivity and emphasize the need to characterize genotype-by-environment (G × E) interactions to guide future breeding and yield-stability improvement efforts.

Wheat breeding has now reached a stage where local adaptation, rather than global, increasingly determines the ceiling for yield gains [11,12]. Experience with ostensibly “high-yield” lines shows that, once deployed outside their selection environment, performance becomes unpredictable unless genotype-by-environment (G × E) responses are first quantified in the target region [13].

Advances such as fully annotated reference genomes, pangenomic panels and genomic-selection pipelines have accelerated allele mining and parent selection [14]; however, wheat’s complex allotetraploid architecture and the magnitude of G × E interactions still limit the translation of genomic predictions into consistent field gains [15]. The crop’s broad genetic base underpins notable phenotypic plasticity, buffering yield across thermally and hydrologically heterogeneous landscapes [16].

Recent multi-actor, multi-environment trials confirm that advanced lines tested with farmers across contrasting semi-arid sites can expose genotypes that combine high mean yield with stability, while simultaneously generating agronomic information valued by end-users [17]. In Peru, where local durum wheat production remains limited and import dependence persists, identifying genotypes capable of maintaining yield stability across environments is a national priority. The introduction of locally adapted cultivars not only reduces dependence on imports but also helps conserve in situ genetic diversity, contributing to resilient food systems under the framework of the Convention on Biological Diversity [18,19].

To address this challenge, we implemented integrative stability analyses using the additive main effects and multiplicative interaction (AMMI), the genotype plus genotype-by-environment (GGE) biplot, and the weighted average of absolute scores (WAASBY) and AMMI stability value (ASV) models, which together provide complementary insights into yield performance, stability, and adaptability [8,12,17,19,20,21]. These approaches allow for the identification of both broadly and specifically adapted lines under semi-arid Peruvian conditions.

In wheat, AMMI models typically attribute more than 70% of the variance to environmental and interaction effects, efficiently distinguishing broadly adapted lines from those expressing specific adaptation [17,20,22,23]. Moreover, other studies reporting multi-environment trial (MET) syntheses in wheat indicate that environments still explain more than 40% of the total variation in grain yield, while genotypes and the G × E term contribute approximately 6–21% and 8–23%, respectively, figures that underscore the importance of interaction-focused statistical approaches [24]. In Eastern Europe, Jędzura et al. [25] reported that environmental main effects explained 89% of variation across six spring wheat locations, with the AMMI Stability Value (ASV) and Yield-Stability Index identifying STH 21-09 as the most widely adapted line.

Against this background, the present study evaluates eleven T. durum lines alongside the commercial variety ‘INIA 412 Atahualpa’ across three representative semi-arid sites in Arequipa, Peru. The findings not only advance Peru’s efforts toward wheat self-sufficiency but also exemplify how integrative G × E analytics can enhance breeding decisions in environments increasingly challenged by climate variability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ubication

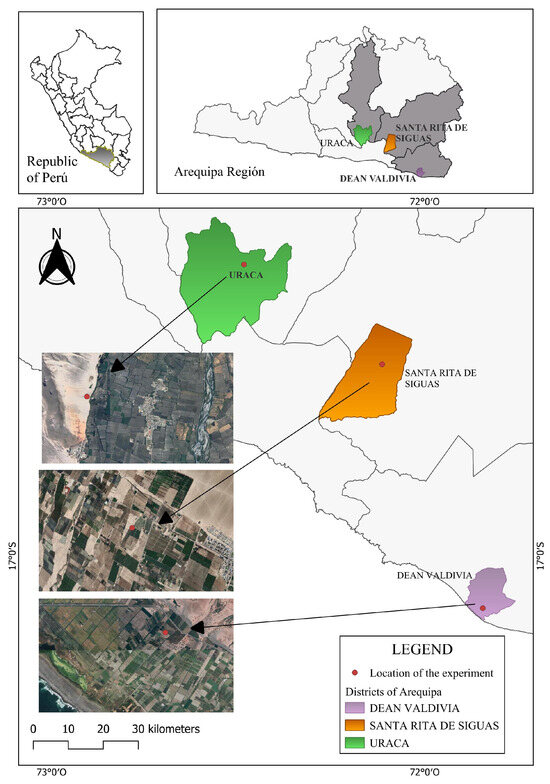

Field trials were conducted during the 2023–2024 growing season at three contrasting locations managed by the Arequipa Agricultural Experiment Station (EEA-Arequipa) of the National Institute for Agricultural Innovation (INIA). Although all sites are located within the Arequipa Region, Peru, they exhibit marked differences in elevation, climate, and soil characteristics, thereby capturing the environmental diversity of the main wheat-growing areas in southern Peru. For clarity, the term Environment in this manuscript specifically denotes the different experimental locations. As the evaluation was restricted to a single agronomic cycle (2023–2024), Year effects were not incorporated into the environmental source of variation.

The first site, the Santa Elena Research Center (Uraca District, Castilla Province; 16°13′15″ S, 72°28′50″ W; 480 m a.s.l.), is a lowland environment with warm conditions and silt loam soils. The second site, the San Francisco de Paula Center (Deán Valdivia District, Islay Province; 17°07′45″ S, 71°48′13″ W; 23 m a.s.l.), represents a coastal environment with hot temperatures and silt loam soils. The third site, the Santa Rita Center (Santa Rita de Siguas District, Arequipa Province; 16°35′05″ S, 71°59′20″ W; 1298 m a.s.l.), lies in a mid-altitude valley characterized by moderate temperatures and sandy loam soils. Collectively, these locations span a gradient of thermal regimes and edaphoclimatic conditions representative of the principal wheat production niches in southern Peru, enabling a robust assessment of genotype adaptability and performance across diverse environments (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Locations of the experimental sites in the Arequipa Region, southern Peru. Field trials were conducted during the 2024–2025 growing season at three contrasting locations managed by the Arequipa Agricultural Experiment Station (EEA-Arequipa) of the National Institute for Agricultural Innovation (INIA). (i) The Santa Elena Research Center (Uraca District) is highlighted in green, (ii) the Santa Rita Center (Santa Rita de Siguas District) is displayed in orange, and (iii) the San Francisco de Paula Center (Deán Valdivia District) is shown in purple. The satellite images on the left indicate the precise fields where the experimental plots were established.

2.2. Weather Records

Daily meteorological data were recorded from August 2024 to February 2025 to characterize the climatic context of the experiments. Data were retrieved from the nearest automated stations of Peru’s National Meteorological and Hydrological Service (SENAMHI): “Co Aplao” for the Santa Elena site, “Co Pampa Blanca” for San Francisco de Paula, and “Co Santa Rita de Siguas” for Santa Rita.

Although all sites share a semi-arid macroclimate, altitudinal differences produce distinct microclimatic profiles. Santa Elena exhibited the lowest mean temperatures (13.4–15.6 °C) and relative humidity (31–87%). In contrast, the San Francisco de Paula site experienced intermediate conditions, with maximum daytime temperatures ranging from 19.7 °C to 20.3 °C and humidity levels exceeding 39%. Finally, the Santa Rita de Siguas site displayed similar conditions to San Francisco de Paula, with average temperatures ranging from 17.8 °C to 20.4 °C and moderate relative humidity levels. As shown in Table S1, precipitation remained negligible throughout the cropping period, with cumulative rainfall close to 0 mm.

2.3. Soil Characteristics

Soil properties at each site were characterized prior to sowing. Composite samples (0–20 cm; n = 20 subsamples per plot) were collected and air-dried for analysis. The collected samples were securely sealed and transported to the Soil, Water, and Foliar Laboratory (LABSAF) at the Arequipa Agricultural Research Station (INIA) for subsequent analyses. The evaluated soil properties included texture and pH [26], while electrical conductivity was determined following the procedure described by Molua [27]. Organic matter content [28] and total nitrogen [29] were also quantified. Additionally, cation exchange capacity, available phosphorus, and potassium were extracted and analyzed according to the methodologies of Muindi [30] and Xu et al. [31], respectively.

At Santa Rita, the profile consisted of an excessively drained sandy loam dominated by coarse sand (78.6%). This texture favours rapid infiltration and root aeration but limits water and nutrient retention. The soil was slightly alkaline (pH 7.7) with modest organic matter (1.4%). By contrast, San Francisco de Paula and Santa Elena featured silt loam soils, with silt comprising 68% and 51%, respectively. Both sites were slightly alkaline (pH 7.6) and exhibited low organic matter and macronutrient reserves (Table 1).

Table 1.

Physicochemical Characteristics of the Soils Before Planting the Durum Wheat Crop.

2.4. Plant Material

Seeds for the trial were sourced through the long-standing collaboration between the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT, Texcoco, Mexico) and the National Institute for Agricultural Innovation (INIA, Lima, Peru). The elite durum wheat lines were developed by the Durum Wheat Improvement Program at CIMMYT and provided to INIA under collaborative breeding and evaluation agreements. These CIMMYT-derived lines were first multiplied at INIA’s National Wheat Gene Bank and subsequently transferred to the National Wheat Seed Production Program (PROSEM) for regional evaluation.

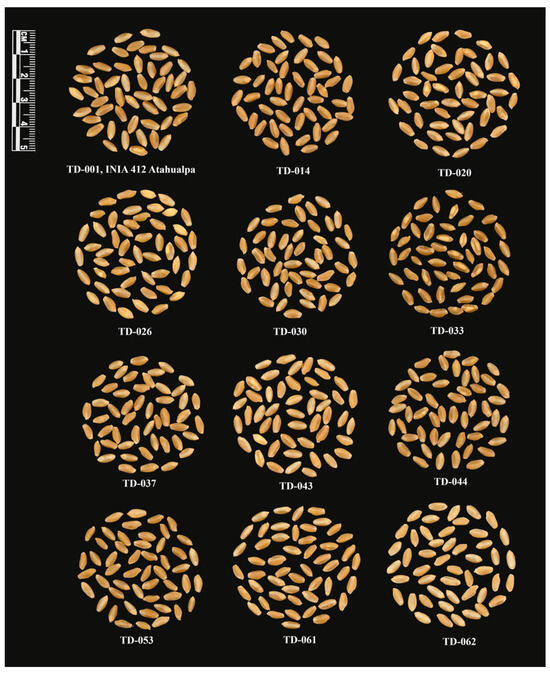

The commercial variety INIA 412 ‘Atahualpa’, widely cultivated in Peru’s southern coastal region, served as the local benchmark against eleven advanced breeding lines (Figure 2, Table S2). All experimental genotypes are durum wheat (Triticum durum Desf.) registered in the INIA Wheat Gene Bank (https://genebankperu.inia.gob.pe/, accessed on 9 October 2025).

Figure 2.

Eleven promising durum wheat genotypes and the commercial variety TD-001 (INIA 412 Atahualpa) used in the present study.

2.5. Experimental Design and Management

Once the seedbeds were prepared, field trials at the three sites were established as independent randomized complete block designs (RCBDs) with three replicates per location. Each experimental unit (4.8 m2) comprised four rows, 4 m in length, spaced 0.30 m apart. Seed was hand-sown at a rate of 100 kg ha−1. Basal fertilization totaled 200–100–100 kg ha−1 (N–P–K), with 100–50–50 kg ha−1 incorporated at sowing and 100–0–0 kg ha−1 top-dressed at early tillering. Furrow irrigation by gravity was scheduled according to phenological stage—primarily at emergence, tillering, stem elongation, and early grain filling.

2.6. Agronomic Measurements

Grain yield (GY, kg ha−1) was determined by harvesting a 1 m2 area from each plot at 120 days after sowing, followed by threshing and cleaning of the grains. The recorded weight was extrapolated to a hectare basis and adjusted to 12% moisture, following the methodology of CIMMYT (1988) [32], as explained by the following equation:

Plant height (cm) was measured at physiological maturity on ten plants per plot, from the soil surface to the tip of the fully expanded flag leaf, using a rigid ruler. Hectoliter weight (kg hL−1), as an indicator of grain quality, was obtained by filling a 0.6 L standardized container with clean grain, leveling, weighing, and converting the density to kg hL−1 according to International, American sociation of Cereal Chemists (AACC) [33]. Thousand-kernel weight (g) was assessed in wheat by counting seeds and then weighing with a precision scale, and the average of two independent determinations per plot was used for the analysis [34].

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The data were subjected to combined analysis of variance (ANOVA) to detect the significance of main effects and genotype × environment (G × E) interactions. Prior to ANOVA, data were checked for normality and homogeneity of variances using the Shapiro–Wilk and Levene’s tests, respectively. The AMMI (Additive Main Effects and Multiplicative Interaction) model was used to partition G × E interaction into principal components (PCAs) and to explore the interaction structure [35,36]. Stability was assessed using the AMMI Stability Value (ASV) and WAAS (Weighted Average of Absolute Scores) index [37]. The Weighted Average of Absolute Scores from the BLUPs and Yield (WAASBY) index was calculated to evaluate the simultaneous performance and stability of genotypes. This index is dimensionless but expressed on a 0–100 scale for interpretability, where values closer to 100 indicate higher yield combined with greater stability, and values closer to 0 reflect lower performance and/or high instability, following the methodology described by Olivoto et al. [38]. GGE biplots were used to visualize the “which-won-where” pattern of genotype performance across environments [24,39]. All statistical analyses were performed in R software (version: 4.5.0), using the metan package [40].

3. Results

3.1. Grain Yield (t ha−1)

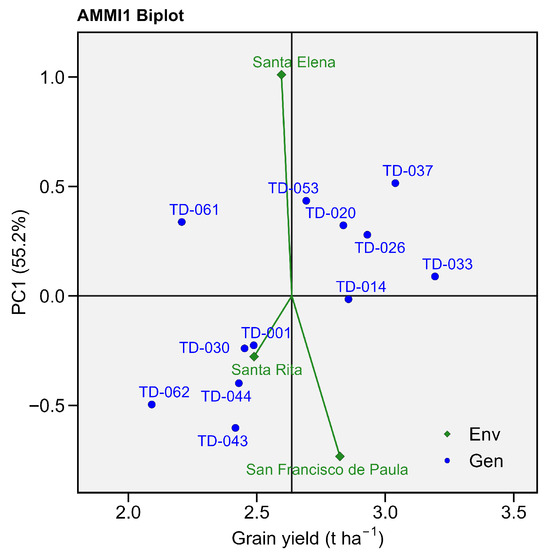

The AMMI-based analysis of variance revealed highly significant effects for both the genotype main factor (GEN; F = 2.85, p = 0.004) and the genotype × environment interaction (G × E; F = 1.80, p = 0.035). In contrast, differences among environments were not significant (ENV; F = 1.43, p = 0.309), indicating that the differential response of genotypes across sites was the principal source of variation in grain yield. The first principal component (PC1) alone accounted for 55.2% of the interaction variance and was marginally significant (p = 0.062), while the second principal component (PC2) explained the remaining 44.8% and was not significant (p = 0.083) (Table S3).

The AMMI1 biplot for grain yield explained 55.2% of the total G × E variation, with PC1 capturing the major interaction patterns among genotypes and environments. Across environments, observed yields ranged from 2.09 t ha−1 (TD-062) to 3.19 t ha−1 (TD-033), highlighting the broad phenotypic range among durum wheat lines. In particular, TD-033 combines high performance and stability, with small residuals across the locations (≤±0.4 t ha−1 g).

Genotypes TD-037 (3.03 t ha−1) and TD-033 (3.19 t ha−1) recorded the highest mean grain yields, consistent with the highly significant genotype effect detected in the AMMI analysis (p = 0.004), indicating strong performance and responsiveness to favorable environments. Both genotypes exhibited small residuals (≤±0.8 t ha−1). Conversely, TD-062 (2.09 t ha−1) and TD-061 (2.20 t ha−1) had maximum negative residuals, with −0.55 t ha−1 and −0.48 t ha−1, respectively.

Grain yield for Santa Elena showed positive PC1 scores, indicating that this environment contributed favorably to grain yield expression. Genotypes located near Santa Elena such as TD-061, TD-053, TD-020, and TD-037 displayed values ranging from 2.20 to 3.03 t ha−1, demonstrating a strong genotype–environment interaction affinity.

Genotypes close to San Francisco de Paula with negative PC1 scores revealed low values for grain yield, ranging from 2.09 t ha−1 (TD-062), 2.41 t ha−1 (TD-043) and 2.43 t ha−1 (TD-044), and moderate residuals (≤±0.6 t ha−1), and they can be considered locally adapted candidates capable of maintaining high grain yield under restrictive environmental conditions.

Finally, Santa Rita exhibited slightly negative PC1 scores, clustering genotypes such as TD-001 and TD-030 nearby. These genotypes demonstrated observed yields between 2.48 and 2.45 t ha−1 with moderate residuals (≤±0.4 t ha−1), confirming their adaptability and stability under moderately restrictive conditions. Consequently, these lines can be regarded as locally adapted candidates for stable grain yield performance under semi-arid stress, maintaining consistent productivity despite environmental variation (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

AMMI biplot for grain yield (t ha−1). Eleven wheat genotypes grown in three environments. The x-axis shows each genotype’s mean grain yield, while the y-axis depicts its first interaction principal component (PC1, 55.2%). Blue circles represent genotypes; green diamonds represent environments.

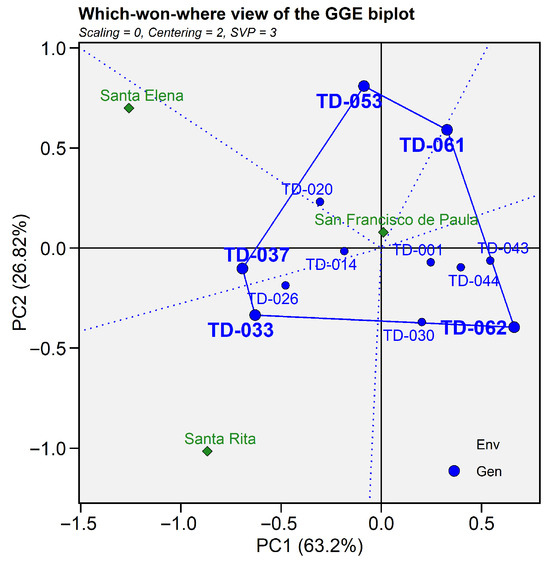

The GGE “which-won-where” biplot for grain yield (PC1 = 63.2%, PC2 = 26.8%; cumulative = 90.02% of the G + GE variation) partitioned the genotype–environment plane into five sectors. The San Francisco de Paula environment was located within the domain of vertex genotype TD-053, identifying this line as the highest-yielding and best-adapted entry under the edaphoclimatic conditions of this site. San Elena was captured by the sector represented by TD-037, indicating its specific adaptation at this location. In contrast, Santa Rita was located in the sector defined by TD-033, confirming its regional suitability and stable performance despite its negative PC1 score. The remaining sectors, defined by TD-061 and TD-062, did not include any of the tested environments. Meanwhile, genotypes located near the origin (TD-044, TD-020, and TD-001) combined intermediate grain yields with minimal interaction effects, reflecting broad, though not exceptional, adaptability across environments (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Which-won-where biplot GGE for grain yield (t ha−1). The first (PC1 = 63.2%) and second (PC2 = 28.8%) principal components jointly account for 90.02%. Blue circles represent genotypes and green diamonds represent environments. The outer polygon links the vertex genotypes TD-053, TD-061, TD-062, TD-037 and TD-033; dotted blue lines from the origin delimit the sectors.

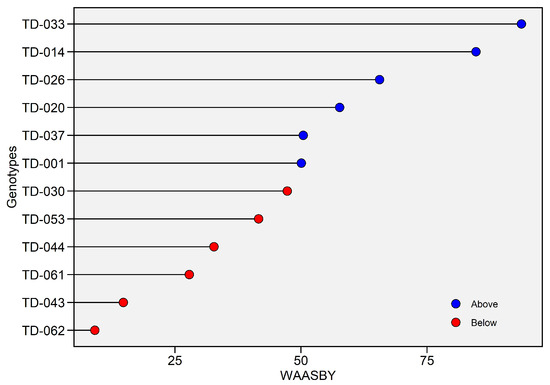

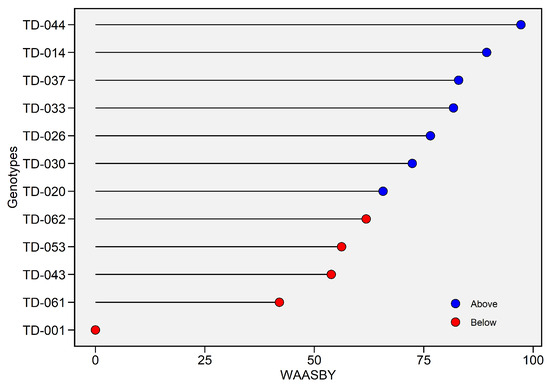

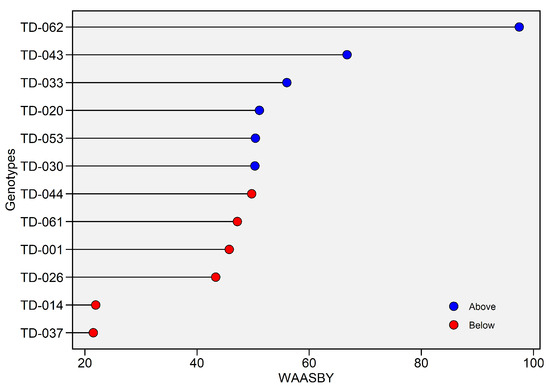

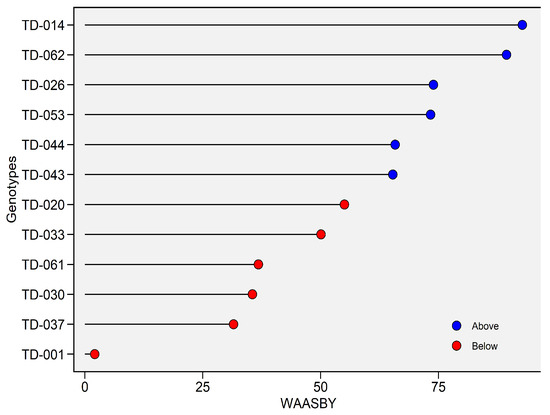

Weighted Average of Absolute Scores and Mean Performance Index (WAASBY), which balances mean performance with stability, clearly discriminated the 12 genotypes (Figure 4). Values ranged from 9.09% (TD-062) to 93.72% (TD-033). Based on WAASBY scores, genotypes above the mean threshold (47.27%) were considered statistically superior in yield–stability performance. Above-average performers (blue dots) includedTD-033, which ranked first, followed by TD-014 (84.72%), TD-026 (65.57%), TD-020 (57.67%), TD-037 (50.45%) and TD-001 (50.07%), all of which combined high grain yield with superior stability, achieving WAASBY values above 50%. Conversely, below-average performers (red dots) included TD-062 (9.09%), TD-043 (14.76%) and TD-061 (27.85%), which showed poor simultaneous performance and stability, whereas TD-053 (41.58%) and TD-044 (32.73%) displayed intermediate performance and stability (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Weighted Average of Absolute Scores and Yield (WAASBY) index for grain yield (t ha−1). The horizontal axis reports the WAASBY value—an integrated measure in which higher scores denote a more desirable combination of grain yield performance and stability—while the vertical axis lists genotypes in descending order of WAASBY. WAASBY values are expressed on a 0–100% scale. Points are colour-coded relative to the overall WAASBY mean (blue = above-average; red = below-average).

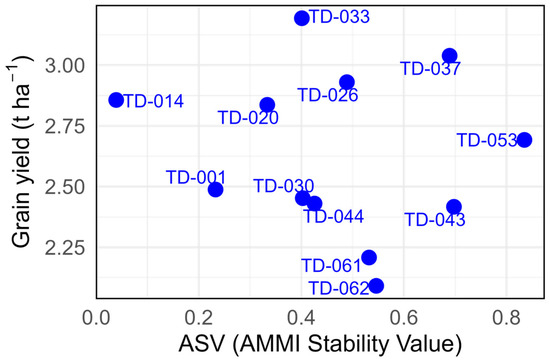

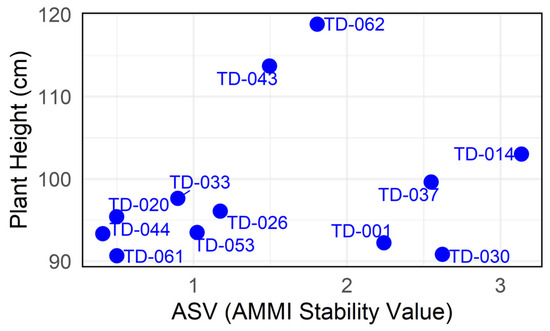

ASV values ranged from 0.03 (TD-014) to 0.83 (TD-053), while grain yield spanned 2.09 t ha−1 (TD-062) to 3.19 t ha−1 (TD-033). In the upper-left quadrant, TD-014 combined the lowest ASV with a yield of 2.85 t ha−1, identifying it as the most broadly adapted and stable genotype, while TD-001 (ASV: 0.23; 2.48 t ha−1) showed a similar but slightly less productive pattern. In the central band, TD-020 (ASV: 0.33; 2.83 t ha−1), TD-026 (ASV: 0.48; 2.90 t ha−1), and TD-033 (ASV: 0.40; 3.19 t ha−1) exhibited high productivity coupled with moderate interaction scores, indicating good but not absolute stability. In the upper-right quadrant, TD-037 (ASV: 0.68; 3.04 t ha−1) and TD-053 (ASV: 0.83; 2.68 t ha−1) achieved high yields at the expense of stability, reflecting greater genotype × environment interaction. Conversely, in the lower-right quadrant, TD-062, TD-061, and TD-043 combined below-average yields (<2.30 t ha−1) with ASV values exceeding 0.50, confirming their limited adaptability and poor agronomic performance (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Grain yield (t ha−1) and AMMI Stability Value (ASV) for the eleven durum wheat genotypes evaluated across three environments. The x-axis displays the ASV and y-axis shows the overall mean grain yield (t ha−1).

3.2. Hectoliter Weight (kg hL−1)

The AMMI-based analysis of variance revealed highly significant effects for the main factor genotype (GEN; F = 4.30, p = 0.0001), for the environment factor (ENV; F = 25.73, p = 0.001), and for the genotype × environment interaction (G × E; F = 4.26, p = 0.00001), indicating that the differential response of genotypes between sites was not the only source of variation in test weight. The first two multiplicative axes together explained the entire sum of squares of the interaction, with PC1 alone capturing 89.5% of the G × E variance and being highly significant (p = 0.0001), while PC2 accounted for the remaining 10.5% and was not significant (p = 0.461) (Table S3).

Genotypes TD-014 (79.65 Kg hL−1) and TD-044 (80.06 Kg hL−1) exhibited the highest mean electrolyte leakage, consistent with the highly significant genotype effect detected in the AMMI analysis (p = 0.0001). Conversely, TD-043 (78.31 Kg hL−1) and TD-061 (78.33 Kg hL−1) recorded the lowest mean values. Residuals for these genotypes were close to zero, reinforcing the reliability of the AMMI-predicted values.

The environment Santa Elena showed positive PC1 scores, indicating a strong positive contribution to electrolyte leakage expression. Genotypes located near Santa Elena, such as TD-061, TD-062 and TD-053, displayed values ranging from 78.33 to 78.89 Kg hL−1. This clustering reflects a positive association between Santa Elena and higher electrolyte leakage driven by local environmental conditions.

In contrast, San Francisco de Paula exhibited negative PC1 scores, associating with genotypes such as TD-001 (77.81 Kg hL−1), which displayed larger residuals (≤±3 Kg hL−1). This positioning indicates that these genotypes are more prone to membrane damage in limited conditions.

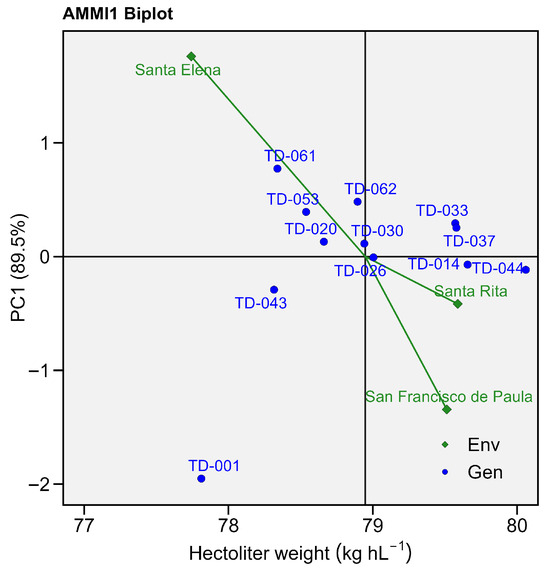

Finally, Santa Rita occupied a central position on the biplot, with small negative PC1 values, grouping genotypes TD-043, TD-044, and TD-014. These genotypes showed minimal residuals values (≤0.8 Kg hL−1) and can therefore be considered stable and less sensitive to electrolyte leakage fluctuations under moderately restrictive environments (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

AMMI biplot for hectoliter weight (Kg hL−1). Eleven wheat genotypes grown in three environments. The x-axis shows each genotype’s mean grain yield, while the y-axis depicts its first interaction principal component (PC1, 55.2%). Blue circles represent genotypes; green diamonds represent environments.

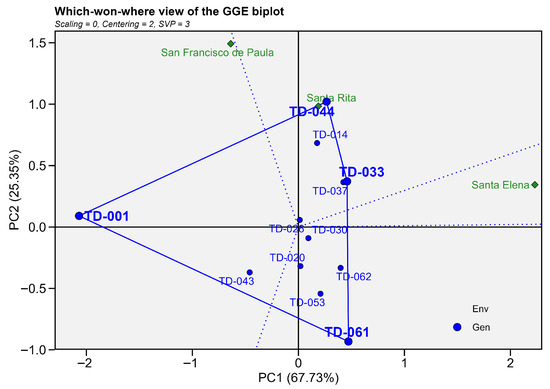

The “which-won-where” GGE biplot for hectoliter weight (PC1 = 67.73%, PC2 = 25.35%; cumulative = 93.08%) divided the genotype–environment plane into four sectors (Figure 7). In sector 1, corresponding to Santa Elena, the TD-061 genotype dominated this environmental point. Sector 2 encompassed Santa Rita, and in this environmental sector, genotypes TD-044 and TD-033 dominated, identifying them as the genotypes with the highest hectoliter weight under the soil and climate conditions at that site. Sector 3encompassed San Francisco de Paula, and this location was captured by the sector headed by TD-001, indicating specific conditions and a higher hectoliter weight of that genotype. In the remaining sectors, TD-061 vertices define sectors without an assessed environment. Genotypes located close to the origin (TD-026, TD-043, TD-020, TD-62, TD-037 and TD-053) combined intermediate hectoliter weight with minimal interaction, thus exhibiting broad, though not exceptional, adaptation (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Which-won-where biplot GGE for hectoliter weight (Kg hL−1). The first (PC1 = 67.73%) and second (PC2 = 25.35%) principal components jointly account for 93.08%. Blue circles represent genotypes and green diamonds represent environments. The outer polygon links the vertex genotypes TD-001, TD-044, TD-033 and TD-061; dotted blue lines from the origin delimit the sectors.

In the results obtained with the WAASBY superiority index, the genotype TD-044 achieved the highest score, positioned very close to 100%, followed by genotype TD-014 (89.39%) in terms of grain weight quality measured as hectoliter weight. The second group included genotypes TD-037 (82.96%), TD-033 (81.78%), TD-026 (76.52%), TD-030 (72.37%), and TD-020 (65.71%), with scores above 65% but below 90%. These genotypes could be selected for grain quality studies due to their moderate hectoliter weight. Genotypes TD-062 (61.86%), TD-053 (56.23%), TD-043 (53.88%), and TD-061 (42.02%) showed scores below the mean (in red). At the lowest end of the scoring spectrum was genotype TD-001 (77.81 Kg hL−1, 0%), which exhibited poor grain quality in terms of hectoliter weight and lower stability across environments (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Weighted Average of Absolute Scores and Yield (WAASBY) index for hectoliter weight (Kg hL−1). The horizontal axis reports the WAASBY value—an integrated measure in which higher scores denote a more desirable combination of grain yield performance and stability—while the vertical axis lists genotypes in descending order of WAASBY. WAASBY values are expressed on a 0–100% scale. Points are colour-coded relative to the overall WAASBY mean (blue = above-average; red = below-average).

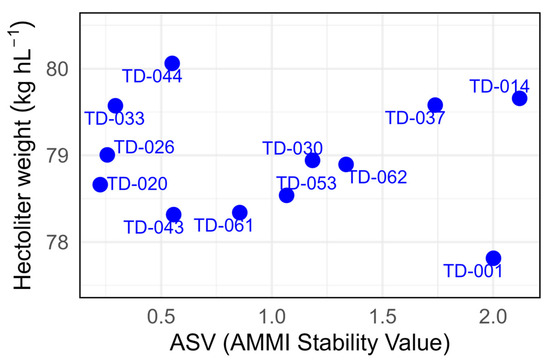

The ASV values indicate 0.29 for genotype TD-033, with a hectoliter weight of 79.57 kg hL−1, which is the most stable with the highest weight, followed by genotypes with a moderate hectoliter weight TD-020 (ASV: 0.22; 78.66 kg hL−1) and TD-026 (ASV: 0.25; 79.00 kg hL −1). These combine intermediate–high hectoliter weight and stability. Genotype TD-044 showed the highest grain hectoliter weight, with 80.06 kg hL−1, and a moderate ASV of 0.55. Likewise, TD-014 exhibited a favourable hectoliter weight of 79.66 kg hL−1, which indicates good grain quality. However, this genotype also recorded the highest AMMI Stability Value (ASV: 2.11). Finally, genotype TD-001 had one of the highest ASVs with 1.95 combined with the lowest hectoliter weight (77.81 kg hL−1), indicating poor stability across environments and low grain quality (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Hectoliter weight (kg hL−1) and AMMI Stability Value (ASV) for the eleven durum wheat genotypes evaluated across three environments. The x-axis displays the ASV and y-axis shows the overall mean grain yield (kg hL−1).

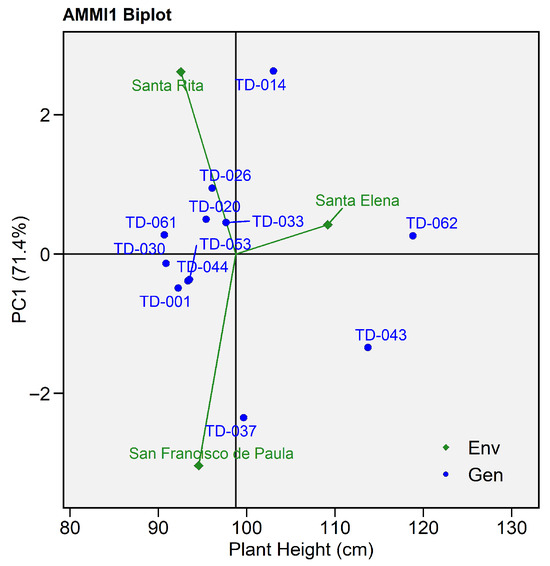

3.3. Plant Height (cm)

The AMMI-based analysis of variance (Table S3) revealed highly significant differences among genotypes and environments for plant height. The main effects of genotype (F = 14.35, p < 0.0001) and environment (F = 31.98, p < 0.0006) were statistically significant. However, the genotype × environment (G × E) interaction was not significant (F = 0.99, p < 0.48), indicating that the differential response of genotypes between sites was not the main source of variation in grain yield. The first two multiplicative axes explain the sum of squares of the interactions, with PC1 accounting for 71.4% (p = 0.2399) and PC2 for 28.6% (p = 0.7915), both showing no significant contribution to the interaction pattern

Among the evaluated genotypes, TD-062 (118.81 cm) and TD-043 (113.73 cm) exhibited the greatest mean plant heights, consistent with the significant genotype effect detected in the AMMI analysis (p < 0.0001), indicating vigorous vegetative growth under favorable conditions. Conversely, TD-030 (90.85 cm) and TD-061 (90.67 cm) displayed the lowest values, reflecting limited growth potential. Genotypes TD-026, TD-033, and TD-020 combined moderate height with small residuals (≤±3.5 cm).

The environment Santa Elena exhibited positive PC1 scores, closely associated with genotypes TD-033 and TD-062, which achieved mean values of 97.65 cm and 118.81 cm, respectively. This pattern indicates that the environmental conditions in Santa Elena favored increased plant height.

In contrast, San Francisco de Paula presented negative PC1 scores, with genotype TD-037 (99.64 cm) located nearby, suggesting restricted vegetative development under this environment. Meanwhile, Santa Rita, positioned close to genotypes TD-014 and TD-026, exhibited a more variable response, with larger residuals (≤±8.7 cm), indicating lower stability and a stronger sensitivity to environmental fluctuations (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

AMMI Biplot for plant height (cm). Eleven wheat genotypes grown in three environments. The x-axis shows each genotype’s mean grain yield, while the y-axis depicts its first interaction principal component (PC1, 55.2%). Blue circles represent genotypes; green diamonds represent environments.

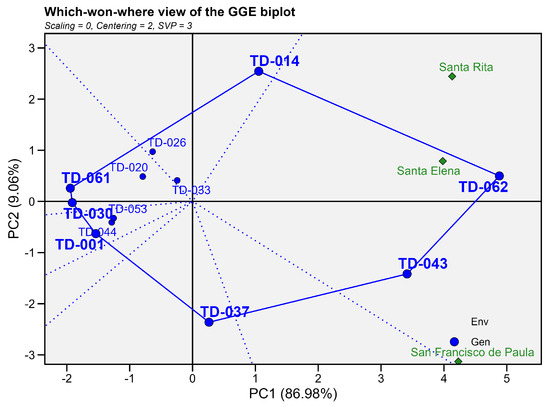

In the “which-won-where” GGE biplot for grain yield (PC1 = 87.88%, PC2 = 8.65%; Cumulative = 96.53), all three environments (Santa Elena, Santa Rita, and San Francisco de Paula) were grouped within the same sector defined by the vertex genotypes TD-062 and TD-043, indicating that these genotypes exhibited superior performance and broad adaptability under the prevailing edaphoclimatic conditions. In particular, TD-062 was associated with Santa Elena and Santa Rita, confirming its high responsiveness and favorable growth in these environments, whereas TD-043 aligned more closely with San Francisco de Paula.

The remaining vertex genotypes—TD-061, TD-030, TD-001, and TD-037—defined their own sectors without any associated environments, indicating that these accessions did not perform best in any particular location and likely possessed lower or unstable adaptability across sites. Genotypes TD-033, TD-026, TD-020, and TD-053, located near the origin of the biplot, combined intermediate plant height with minimal G × E interaction, reflecting high stability and consistent performance across environments. (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Which-won-where biplot GGE for plant height (cm). The first principal component (PC1 = 87.88%) and the second principal component (PC2 = 8.65%) jointly account for 96.53%. Blue circles represent genotypes and green diamonds represent environments. The outer polygon links the vertex genotypes TD-037, TD-043, TD-062, TD-014, TD-061 and TD-001; dotted blue lines from the origin delimit the sectors.

WAASBY values for plant height ranged from 21% (TD-037) to approximately 95% (TD-062). A threshold set at the overall average (approximately 50%) divided the genotypes into two groups: The first was genotypes with above-average performance (blue dots). TD-062 ranked first, followed by TD-043 and TD-033. These genotypes combined high performance with low WAASBY scores, resulting in WAASBY values above 50%. The second was genotypes with below-average performance (red dots). TD-037 and TD-014 showed simultaneous low height and stability (<25%), while TD-026, TD-001, TD-061, and TD-044 showed intermediate height (approximately 40–50%). The monotonic increase from TD-030 to TD-020 denotes a continuum rather than discrete classes, allowing the breeder to choose breakpoints tailored to specific risk levels (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Weighted Average of Absolute Scores and Yield (WAASBY) index for plant height (cm). The horizontal axis reports the WAASBY value—an integrated measure in which higher scores denote a more desirable combination of grain yield performance and stability—while the vertical axis lists genotypes in descending order of WAASBY. WAASBY values are expressed on a 0–100% scale. Points are colour-coded relative to the overall WAASBY mean (blue = above-average; red = below-average).

The ASV biplot assessed genotypic stability independently of mean yield. ASV values spanned nearly an order of magnitude, from 0.40 (TD-044) to 3.13 (TD-014), while height ranged from 90.67 cm (TD-061) to 118.82 cm (TD-062). High stability was observed with the lowest height (lower left quadrant). TD-061 achieved the lowest ASV (0.49) at 90.67 cm, marking it as the most adapted genotype. TD-001 (ASV: 2.24; 92.25 cm) followed a similar pattern, but with lower stability. High stability and lower height were observed (lower left quadrant). TD-020 (ASV:0.49; 95.41 cm), TD-044 (ASV: 0.40; 93.35 cm), TD-033, TD-053 (ASV: 1.02; 93.51 cm), and TD-026 (ASV: 1.17; 96.09 cm) offered desirable height and high stability; however, this may have impacted performance. Medium stability and higher height (upper middle quadrant) were observed; TD-043 (ASV: 1.49; 113.73 cm) and TD-062 (ASV: 1.80; 118.81 cm) had low height and lower stability (lower right quadrant). TD-001, TD-037 (ASV: 2.54; 99.65 cm), TD-030 (ASV: 2.62; 90.85 cm) and TD-1 (ASV: 2.24; 92.25 cm) combined below-average heights with high ASV, confirming their poor agronomic prospects (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Plant height (cm) and AMMI Stability Value (ASV) for the eleven durum wheat genotypes evaluated across three environments. The x-axis displays the ASV, and the y-axis shows the overall mean plant height (cm).

3.4. Thousand-Kernel Weight (g)

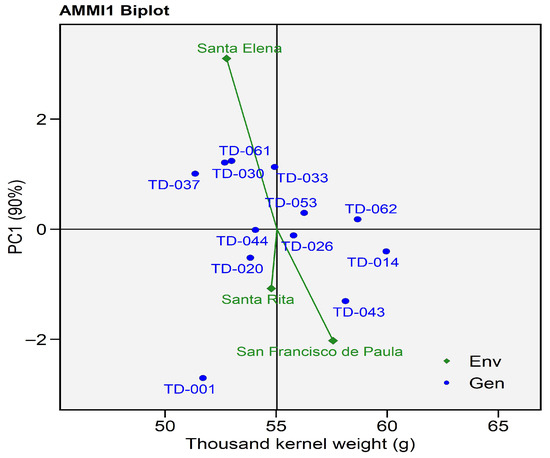

The combined ANOVA for wheat thousand-kernel weight (TKW) showed that genotype was by far the principal source of variation, accounting for 14.57% of the total sum of squares, whereas environment explained only 26.95%. The main effects of genotype (F = 6.68, p < 0.0297) and environment (F = 70.15, p < 0.0001) were statistically significant. However, the G × E interaction term was highly significant (F = 2.93, p < 0.0003) and contributed an additional 18.20% to the variance, thereby justifying a multivariate interrogation using the AMMI framework. The first interaction principal component (PC1) captured 90% of the interaction sum of squares with high significance (p = 0.0001), while the second (PC2) explained only 10% and was not significant (p = 0.77) (Table S3).

The AMMI1 biplot for thousand-kernel weight (TKW) explained 90% of the total genotype-by-environment (G × E) variation, with the first principal component (PC1) accounting for most of the interaction effects. This high percentage indicates that the AMMI model effectively captured the main interaction structure. The observed and predicted values (Y and Ypred) showed close agreement, with residuals generally below ±4 g across genotype–environment combinations, confirming the robustness and predictive accuracy of the model.

Genotypes TD-014 (59.95 g) and TD-062 (58. 67 g) exhibited the highest mean TKW values, indicating strong performance and stability under contrasting environments. These genotypes also presented low residuals (≤±2 g), reinforcing their stability across sites. Conversely, TD-001 (51.70 g) in Santa Elena and TD-030 (51.2 g) in San Francisco de Paula had large negative residuals with −8.71 g and −4.04 g, respectively, revealing poor adaptation and high sensitivity to environmental changes.

Santa Elena exhibited positive PC1 scores, indicating that this environment contributed positively to the expression of thousand-kernel weight. Genotypes positioned near Santa Elena on the positive PC1 axis (e.g., TD-037, TD-033, TD-030, and TD-061) displayed predicted AMMI values ranging from 51.35 to 52.9 g, suggesting that these lines responded favorably to the specific environmental conditions of this site. Such positioning implies a strong genotype–environment affinity, where the climatic and edaphic factors of Santa Elena favored kernel development and grain filling.

In San Francisco de Paula, the AMMI model revealed considerable variation in thousand-kernel weight (TKW) among genotypes, with observed values ranging from 51.70 g (TD-01) to 59.95 g (TD-014). Genotypes TD-014 and TD-043 exhibited the highest observed and predicted AMMI values, indicating superior grain development under this environment. Overall, San Francisco de Paula favored genotypes that combine above-average kernel weight with positive G × E interaction, notably TD-014 and TD-043, which can be considered locally adapted candidates capable of maintaining high TKW expression under restrictive environmental conditions.

In the AMMI1 biplot (Figure 15), Santa Rita exhibited negative PC1 scores, clustering genotypes such as TD-044, TD-020, and TD-026 nearby, confirming their adaptation to moderately restrictive conditions. These genotypes can be considered locally adapted candidates for high-TKW expression under restrictive environments, maintaining yield stability despite environmental stress.

Figure 15.

AMMI biplot for Thousand-Kernel Weight (g). Eleven wheat genotypes grown in three environments. The x-axis shows each genotype’s mean grain yield, while the y-axis depicts its first interaction principal component (PC1, 90%). Blue circles represent genotypes; green diamonds represent environments.

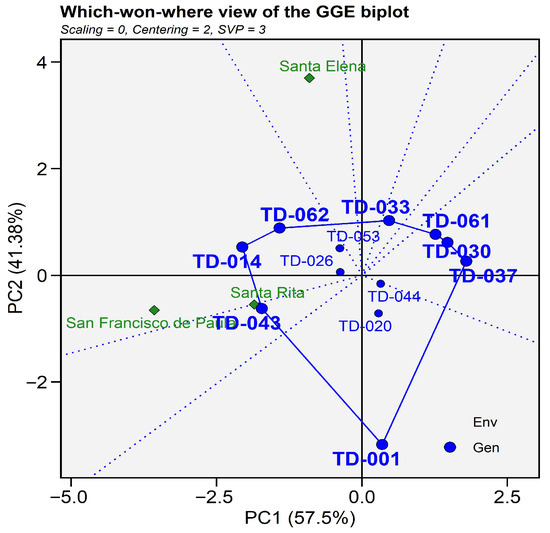

The “Which-won-Where” for thousand-kernel weight explained 98.88% of th total genotype + genotype-by-environment (G × E) variation, with PC1 accounting for 57.5% and PC2 for 41.38%, indicating that most of variability in grain yield traits was captured by the first two components. San Francisco de Paula and Santa Rita grouped closely, showing similar discriminating ability and representativeness, whereas Santa Elena formed an independent sector, reflecting its differentiated agro-climatic conditions. Genotypes positioned at the vertices of the polygon were identified as the highest-yielding in their respective environments: TD-014 and T-062 performed best and TD-026 and TD-053 had affinity in San Francisco de Paula, TD-043 excelled in Santa Rita, and no genotypes performed the best in Santa Elena. Some vertex genotypes (TD-033, TD-61, TD-030, TD-037 and TD-01) were not associated with any environment, indicating that they did not perform best in any of the tested locations. These genotypes exhibited specific responses that were not favored under the current environmental conditions, but they might outperform others under untested or more contrasting environments. Genotypes TD-014, TD-026, and TD-062, positioned near the origin, exhibited greater stability and average performance across environments. In contrast, genotypes TD-001 and TD-043, located far from the origin, displayed specific adaptability and higher sensitivity to environmental variation (Figure 16).

Figure 16.

The GGE biplot displays the first two principal components, which together account for 98.88% of the genotype + G × E variation (PC1 = 57.50%, PC2 = 41.38%). A convex polygon was drawn around genotypes with the most extreme scores; dashed rays emanating from the origin partition the plot into sectors. Any environment symbol falling within a given sector identifies the genotype at that sector’s vertex as the “winner” for that environment.

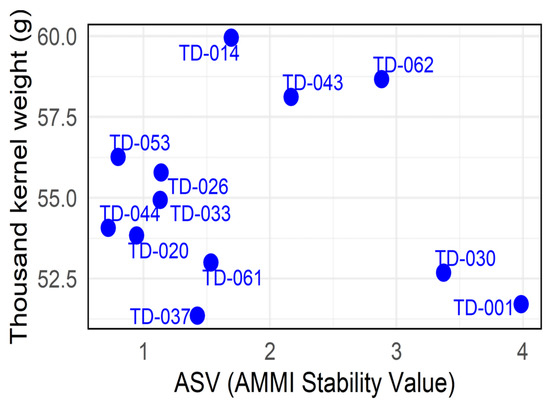

In the WAASBY analysis, TD-014 tops the list with 92.77%, evidencing its capacity to combine high thousand-kernel weight (TKW) with stability; TD-062 shows a similar pattern with 89.43%. These results corroborate the AMMI and GGE findings. Also above the 50% threshold are lines TD-044 and TD-043, with scores of 65.79 and 65.31, respectively. By contrast, the lower (red) tail is led by TD-001 (INIA Atahualpa), whose score of 2.07% indicates very low TKW (Figure 17).

Figure 17.

Weighted Average of Absolute Scores and Yield (WAASBY) index for Thousand-Kernel Weight (g). The horizontal axis reports the WAASBY value—an integrated measure in which higher scores denote a more desirable combination of grain yield performance and stability—while the vertical axis lists genotypes in descending order of WAASBY. WAASBY values are expressed on a 0–100% scale. Points are colour-coded relative to the overall WAASBY mean (blue = above-average; red = below-average).

Standing out in the lower-left quadrant is line TD-053 (ASV: 0.79; 56.26 g), indicating reliable performance with stable grain weight. In the upper-left quadrant, TD-014 (ASV: 1.69; 59.96 g) shows the highest thousand-kernel weight with low ASV. Conversely, the upper-right quadrant features TD-062 (ASV: 2.88; 58.67 g) with a high TKW but an elevated ASV, signaling instability. Finally, in the lower-right quadrant, the check variety TD-001 (ASV: 3.98; 51.70 g) exhibits the lowest TKW and high instability (Figure 18).

Figure 18.

Thousand-Kernel Weight (g) and AMMI Stability Value (ASV) for the eleven durum wheat genotypes evaluated across three environments. The x-axis displays the ASV, and the y-axis shows the overall mean plant height (cm).

4. Discussion

The multi-environment evaluation revealed that genotype performance in grain yield and quality traits was highly context-dependent, underscored by a significant genotype × environment (G × E) interaction for yield and hectoliter weight. In our trials, the environmental main effect on yield was relatively modest, whereas G × E effects were pronounced—indicating that yield rankings shifted substantially across the three Peruvian sites. This pattern aligns with the general experience in cereal METs, where environment often explains the majority of yield variation (e.g., ~80–90%) and G × E typically accounts for a sizeable remainder. Even so, the yield instability observed here emphasizes that selecting broadly adapted genotypes requires explicit G × E analysis. Our results mirror findings in tropical maize and other cereals where G × E can contribute over one-quarter of total variance [41,42] and confirm that yield performance in durum wheat is highly location-specific unless stable genotypes are identified. Consistent with this, we found that certain lines (e.g., TD-037 and TD-033) ranked top at one site but not others, whereas a few genotypes maintained near-average yields everywhere. This reinforces that “high-yielding” lines are only superior in a target region if their G × E responses align with local conditions. Genotypes showing extreme sensitivity to micro-environmental fluctuation—for instance, TD-062, which had both low mean yield and large yield swings—are typically undesirable for direct release. Breeding programs often discard such unstable lines or recycle them in crosses to break unfavorable linkages [43]. In our study, TD-062’s poor and inconsistent yield across environments exemplifies this: it likely carries alleles conferring stress susceptibility, making it a better candidate for trait introgression (to pass on specific qualities in new combinations) than for cultivation as a standalone variety.

The environmental contrasts among the test locations—though all are characterized as semi-arid—still imposed different stresses that drove crossover performance. The AMMI analysis indicated that the first interaction principal component (IPCA1) captured a dominant gradient, likely related to temperature and moisture differences across sites, as has been observed in other wheat trials. Indeed, studies in bread wheat and oats show that IPCA1 often reflects a composite environmental index (e.g., cooler/moister vs. hotter/drier sites) [44,45]. The second interaction axis (IPCA2) in our data also explained a large portion of G × E variance, suggesting an additional underlying factor—possibly solar radiation during grain fill or soil fertility—affecting yield stability. Controlled-environment research supports this interpretation; for example, Li et al. [46] showed that reduced radiation can depress wheat yields by ~15%. Such insights point to the value of measuring key environmental covariates in future trials (e.g., incident light, temperature extremes, and soil moisture) to better interpret G × E patterns. Furthermore, climate change is expected to accentuate these environmental effects; meta-analyses project that rising heat and drought will impact not only yields but also grain quality parameters concurrently [47,48]. This lends urgency to breeding strategies that prioritize stability and resilience in both productivity and end-use quality under erratic weather conditions.

Our findings highlight a couple of durum lines achieving the sought-after balance of high mean yield and stability. Notably, TD-014 and TD-001 (the local check ‘INIA 412 Atahualpa’) produced near-average yields with minimal G × E interaction, indicating broad adaptation. These genotypes were positioned near the origin in both AMMI and GGE biplots, a favorable property for general-purpose cultivars. From an agronomic standpoint, such broadly adapted lines are valuable for risk-prone semi-arid systems because they buffer yield across variable conditions—a trait increasingly prized under climate volatility [49]. In contrast, several other lines showed specific adaptation to particular site conditions. For example, TD-033 and TD-037 excelled in the higher-yielding environment of Santa Rita, while TD-053 and TD-061 thrived best at Santa Elena and San Francisco de Paula, respectively, as evidenced by their vertex positions on the GGE “which-won-where” biplot. Each of the three test locations effectively constituted a distinct mega-environment, with a different winning genotype—a scenario commonly seen in multi-site trials where crossover interactions lead to multiple mega-environments [50]. Our GGE biplot accounted for over 90% of the total G + G × E variation in just two principal components, exceeding the ~80% threshold suggested for reliable visualization [51,52]. This high explanatory power gave us confidence in the biplot’s identification of mega-environments and genotype niches. Similar GGE-based studies in wheat and maize have reported two to four mega-environments in a region, so our finding of three is in line with expectations for diverse semi-arid sites. It is worth noting that one genotype, TD-062, sat on an extremity of the biplot with no environment falling in its sector—meaning it “won” nowhere. This underscores that an extreme interaction score is not inherently beneficial; in TD-062’s case it reflected poor stability without any compensating yield advantage. Such cases have been documented in other GGE analyses of wheat, where outlier genotypes can be visually striking yet agronomically inferior [53]. Thus, even as we exploit specific adaptation (e.g., deploying TD-053 in the environment where it excels), we must also recognize when a genotype’s instability outweighs its merits.

From a breeding perspective, these results have direct implications for selection and advancement of durum lines in Peru and similar environments. First, the convergence of evidence from multiple analyses (AMMI, GGE, and stability indices) increases confidence in our selection of broadly adapted vs. specifically adapted candidates. TD-033, for instance, was identified as a top performer in Santa Rita by both AMMI and GGE, and crucially, it did so without sacrificing stability. This genotype also ranked first by the WAASBY index—a composite metric that integrates yield level with stability [38]—confirming that its high yield was accompanied by reliable performance across environments. Likewise, TD-014 and TD-026 achieved strong WAASBY scores in our study, reflecting a robust combination of productivity and consistency, which makes them strong candidates for wider release or further multi-location trials. In contrast, an environment-specific high-yielder like TD-053 (which topped yields at Santa Elena) was penalized in the WAASBY ranking, falling just below the overall mean. This occurred because WAASBY imposes a trade-off: genotypes with outstanding yield in one place but large fluctuations elsewhere receive a lower integrated score. Such outcomes echo recent reports in other crops—for example, in sugar beet and soybean METs—where tweaking the weighting of yield vs. stability in the WAASBY formula (e.g., 60:40 instead of the default 50:50) has been suggested to better suit cases of targeted adaptation. For our durum breeding program, this means that if a target environment is exceptionally stable or highly managed (such that specific adaptation is desirable), we might adjust the index weighting to favor raw performance more. However, under typical smallholder conditions in semi-arid regions, a balanced weighting (giving equal importance to yield and stability) seems prudent to avoid recommending “boom-and-bust” cultivars. The power of WAASBY lies in its ability to simplify decision-making by condensing two important criteria into one number—as evidenced by the close agreement we observed between the WAASBY-based ranking and the separate AMMI/GGE conclusions in this study.

We also evaluated the traditional AMMI Stability Value (ASV) to complement WAASBY [54]. ASV is valuable for pinpointing the most stable genotypes regardless of yield level, which is useful for early-generation selection when breeders may want to cull highly erratic lines. In our results, TD-014 had the lowest ASV, indicating the smallest interaction effect, and indeed this line proved to be an exceptionally consistent performer across sites. This outcome is consistent with other reports on durum wheat and even other crops like chickpea, where low-ASV genotypes show superior predictability under erratic rainfall regimes [55]. Importantly, the highest-yielding line, TD-033, exhibited only a moderate ASV (≈0.41 in our analysis). This suggests that TD-033’s yield advantage did not come at the cost of marked instability—a favorable scenario indicating a partial escape from the typical yield–stability trade-off. By contrast, genotypes such as TD-037 and TD-053, which were among the top yielders in specific environments, showed much higher ASV values (i.e., they contributed strongly to G × E). These two exemplify the classic trade-off: they can be “winners” under the right conditions but are less dependable across variable conditions. Similar trade-offs have been reported in other dryland cereals (e.g., pearl millet [56]), reinforcing that such genotypes should be deployed only in well-characterized target environments or else used in breeding to transfer their desirable traits into a more stable genetic background. It is instructive to integrate the outcomes for secondary traits like plant height, thousand-kernel weight (TKW), and hectoliter weight (grain test weight) into this discussion, since an ideal cultivar must harmonize all these aspects.

Interestingly, our results revealed that the tallest genotypes, TD-062 (118.8 cm) and TD-043 (113.7 cm), exhibited vigorous vegetative growth but produced comparatively lower yields (<2.5 t ha−1). In contrast, the highest-yielding genotypes (TD-020, TD-026, and TD-033) maintained intermediate stature close to 100 cm, suggesting that excessive plant height may divert assimilates toward structural biomass rather than grain filling. This inverse relationship between plant height and yield agrees with modern breeding outcomes reported by De Careddu et al. [57], who documented that genetic reductions in plant stature—largely resulting from the incorporation of semi-dwarf Rht alleles—enhanced the harvest index (HI) and yield stability in Italian durum wheat cultivars.

From an agronomic perspective, genotypes exceeding 100 cm in height, such as TD-062 and TD-043, displayed vigorous vegetative growth under favorable environments (Santa Elena and Santa Rita) but may be prone to reduced yield efficiency or lodging in more stressful sites. Conversely, intermediate genotypes (TD-033, TD-026, and TD-020), positioned near the origin of the GGE biplot, exhibited high stability and consistent performance across environments, indicating broad adaptability rather than site-specific preference. These findings highlight the importance of balancing plant stature and environmental adaptability in durum wheat breeding, supporting targeted selection for both stable and responsive genotypes in southern Peru.

Plant height in our study was influenced strongly by genotype (G) and environment (E) main effects, but notably showed no significant G × E interaction. In practical terms, this means each genotype maintained a relatively consistent height ranking across the three sites. This is a common observation in the absence of major stress differentials—for instance, other wheat and barley studies have found G and E effects on height (and heading date) to outweigh any interaction under moderate conditions [24,36]. Environmental factors did, however, shift the absolute plant heights: the first IPCA for height (71.4% variance) suggested an underlying gradient such as altitude or temperature. Indeed, our warmest, lowest-elevation site (Santa Elena, with sandy soils) tended to produce the tallest plants—e.g., TD-062 reached ~119 cm there—whereas the cooler site favored shorter stature. This reflects known physiological responses: higher temperatures and possibly lower soil fertility at Santa Elena likely extended internode elongation in susceptible genotypes, albeit at the cost of stability. Agronomically, extremely tall plants in wheat are undesirable in modern systems due to lodging risk and harvest difficulty, while very short plants can suffer from reduced biomass and light capture [49]. Therefore, the breeding goal for plant height is an intermediate, stable stature—and encouragingly, we identified lines like TD-020, TD-026, and TD-033 that fit this profile (~95–97 cm with minimal height variation). These lines combine manageable plant architecture with the yield and stability advantages discussed earlier, making them promising candidates for climate-resilient, mechanization-friendly cropping systems. By contrast, TD-062 and TD-043, which were the tallest entries and also among the most interaction-prone, would likely incur higher lodging risk and are less suitable for broad cultivation. The GGE biplot for plant height provided a parallel insight: it showed TD-062 at a vertex capturing the hotter environments (Santa Elena and Santa Rita), confirming that this genotype’s height was notably plastic to those conditions. Meanwhile, genotypes like TD-014 and TD-037 formed vertices not associated with any specific environment, again indicating that extreme phenotypes (very short or very tall) did not translate to an adaptive advantage in our test locations. The stability indices reinforced these points: WAASBY and ASV for height identified TD-061 and TD-044 as the most stable short-statured genotypes (ideal for intensive management), whereas TD-037 and TD-014 had high ASV (unstable height) and thus would be risky choices for farmers without further improvement. This suggests that our breeding program should prioritize medium-height lines and perhaps explore indirect selection tools (such as canopy temperature or stay-green traits) to screen for genotypes that maintain yield stability without extreme stature. In fact, incorporating physiological covariates into stability analysis has been advocated in recent studies—for example, Al-Ashkar et al. [58] successfully combined ASV with canopy temperature data to identify stress-resilient wheat genotypes. Similar multi-trait approaches in durum could help pinpoint genotypes with optimal architecture and water-use efficiency for semi-arid agriculture.

Grain quality traits displayed their own interaction patterns. Thousand-kernel weight (TKW), a yield component and proxy for grain size, was found to be predominantly controlled by genetic differences in our genotypes (genotype accounted for ~47% of TKW variance in the ANOVA, vs. < 10% by environment; Table S3). However, TKW still showed a significant G × E, indicating that some genotypes filled grains better in certain environments. For instance, TD-053 achieved the highest TKW (>55 g) with low interaction, excelling especially at Santa Elena (the coastal valley site). TD-062 also produced large kernels (≈59 g) and was relatively stable for TKW, even though, paradoxically, this did not translate into high yield—possibly due to trade-offs like fewer grains per spike or poor tillering. On the other hand, TD-014 attained an outstanding TKW (~60 g) but only under specific conditions (showing a clear affinity for the San Francisco de Paula environment) at the cost of stability. This suggests that TD-014’s large grain size manifests when cooler or more favorable filling conditions occur, whereas in harsher sites its advantage diminishes. Such G × E for grain weight is reminiscent of farmers’ observations that certain landraces have plumper grains “only in good years.” The GGE biplot for TKW indicated that Santa Rita was dominated by one genotype (perhaps TD-044) while several high-TKW lines (TD-033, TD-061, TD-037, etc.) did not specifically “win” any environment, clustering as non-winning vertices. This again underscores that extreme performance in one trait (grain size) doesn’t guarantee broad adaptation—a genotype needs a whole-suite balance. The hectoliter weight (HLW)—a key grain quality metric reflecting bulk density—showed significant effects of G, E, and G × E, meaning that test weight is also subject to environmental modulation. We observed that some environments (likely the cooler, higher-altitude site) produced generally higher HLW than others, which aligns with known effects of heat and drought stress in reducing grain filling and density [59]. Two lines, TD-044 and TD-014, stood out with superior HLW (>79 kg hL−1) and near-origin positions in biplots, indicating they combined high grain density with stability. Interestingly, these were also among the top yield-stable genotypes, suggesting a positive correlation between yield stability and maintaining grain quality. This is encouraging for breeding, as it means we did not have to sacrifice quality for yield in those lines. Previous work has similarly found that certain durum genotypes can achieve both high test weight and adaptation to arid zones [22]. In contrast, the check variety (TD-001, Atahualpa) had the lowest HLW (~77.8 kg hL−1) and also high instability (ASV > 1.9). Its GGE placement indicated specific adaptation to one environment (San Francisco) but poor performance elsewhere, reflecting its older genetic background’s limitations in grain filling under stress. From a quality standpoint, low and erratic HLW is problematic for semolina processors, so this underscores why newer lines like TD-044 and TD-014 are preferable. The WAASBY index applied to HLW further confirmed the superiority of TD-044 and TD-014—they had the best combined performance–stability scores for grain density. On the other hand, genotypes such as TD-062, TD-043, and TD-001 fell well below the average in HLW and stability. For these, their inconsistent quality across environments would likely translate to unacceptable variation in end-use (for example, flour blend inconsistencies), so they are better suited as parents in breeding (to perhaps transfer specific disease resistances or physiological traits) rather than as cultivars. It is noteworthy that TD-062—while agronomically poor in yield—did have large, dense grains; this could make it useful in crosses aiming to improve grain size or quality in a more adapted genetic background.

Overall, our study demonstrates the value of leveraging integrated stability analyses to drive breeding decisions. By using complementary tools (AMMI, GGE, WAASBY, and ASV), we obtained a nuanced understanding of each genotype’s profile. In many cases these methods agreed, which strengthens our conclusions. For example, all approaches identified TD-014 and TD-033 as among the most desirable lines, whereas TD-062 and TD-043 consistently ranked at the bottom. Such concordance is reassuring and has been noted in other recent studies that combine multiple indices for selection. In practice, we propose a two-stage selection strategy: (1) use ASV (or similar strictly stability measures) early in the breeding cycle to eliminate highly unstable genotypes (as we would now do with TD-062, TD-061, etc.), and (2) in later stages, apply WAASBY or multi-trait indices to choose those entries that best balance yield with stability. This approach ensures that promising high-yield lines are not discarded simply due to one-time poor performance, as WAASBY will appropriately reward their mean yield if they are not too erratic. Conversely, it prevents the advancement of high-yield “flakes” that might look good in one trial but fail elsewhere. Our recommendations echo the findings of Kyratzis et al. [60], who emphasized assessing several stability parameters (AMMI- and regression-based, among others) for both agronomic and quality traits to inform durum wheat breeding under Mediterranean conditions. They found that different stability metrics can correlate poorly with one another and with trait means, implying that a multi-criteria approach is needed for reliable selection—a point substantiated by our experience here. Furthermore, recent advances suggest that incorporating physiological and molecular indicators alongside statistical indices can enhance selection precision. For instance, Rutkoski et al. [61] demonstrated improved G × E predictability when stability indices were coupled with traits like canopy temperature depression or NDVI, while genomic tools can also assist in predicting stability. Such integrative methods could be trialed in our program to accelerate gains in drought tolerance and stability of yield. Notably, our top-yielding stable lines (e.g., TD-033 and TD-014) may serve as excellent parental stock for crossing, as they likely carry alleles for both performance and resilience. In parallel, the identification of specifically adapted lines (like TD-053 for one sub-region) allows the breeding program to consider releasing them directly in their niche environments, where they can outperform broadly adapted ones.

5. Conclusions

This study identified several elite durum wheat genotypes that combine high yield potential with stability across the challenging, semi-arid environments of southern Peru. Genotypes such as TD-033 and TD-014 emerged as particularly outstanding: they not only yielded competitively (rivaling or exceeding the commercial check) but did so reliably and also exhibited desirable traits like moderate plant height and good grain quality. These lines are strong candidates for cultivar release after verification in on-farm trials, as their broad adaptation would benefit farmers facing climate uncertainties. Other lines, like TD-026 and TD-020, also showed a favorable yield–stability balance and merit further evaluation for possible release in specific zones or management systems. On the contrary, genotypes that were low-yielding and unstable (e.g., TD-043, TD-061, and TD-062) can be retained as donor parents if they harbor unique characteristics (for example, TD-062’s large grain size could be useful if combined with a stable background). The use of multi-environment data and indices was critical in making these decisions—had we relied on single-environment results or mean yield alone, we might have misidentified the best breeding materials. The congruence among different analytical methods in classifying our genotypes provides robust evidence for our recommendations. Our experience here also contributes to the broader effort of durum improvement in water-limited environments. In Peru’s case, where national wheat production meets less than 20% of demand, the introduction of high-performing, stable durum varieties could revitalize local wheat farming—especially if coupled with agronomic support to manage drought and soil fertility. In conclusion, our study not only provides specific candidates for immediate advancement (e.g., TD-014, TD-033, and TD-044) but also illustrates a rigorous approach to selection under G × E that will be increasingly pertinent as climate variability intensifies. Integrating quantitative stability metrics into the breeding pipeline ensures that new durum wheat releases will deliver reliable yields and quality to farmers and industry, thereby supporting sustainable cereal production in Peru’s semi-arid highlands and valleys.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijpb16040127/s1, Table S1. Meteorological data recorded during the experimental period (2024–2025).; Table S2. Origin of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) genotypes evaluated.; Table S3. The AMMI analysis of variance for agronomic traits over three environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P.-A. and D.M.; methodology, A.P.-A.; validation, A.P.-A. and M.E.T.; formal analysis, A.P.-A. and D.M.; investigation, A.P.-A. and M.E.T.; resources, D.M.; data curation, D.M.; writing—original draft preparation, H.C.-S. and D.M.; writing—review and editing, H.C.-S. and D.M.; visualization, D.M.; supervision, D.M.; project administration, L.D.-M.; funding acquisition, L.D.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

“Stability and Performance of Durum Wheat (Triticum durum Desf.) Genotypes Across Three Semi-Arid Environments in Southern Peru Using AMMI, GGE and WAASBY Analyses” was funded by the investment project 2361771, “Improving the availability, access, and use of quality seeds for potato, amylaceous maize, grain legumes, and cereals in the regions of Junín, Ayacucho, Cusco, and Puno (4 departments)”, supported by Instituto Nacional de Innovación Agraria, (INIA) Perú.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the technical support provided by the PROSEM project team. Special thanks go to Ing. Kevin García, technician Isabel Córdova and Bach. Alejandra Valdivia for their dedicated assistance in plot preparation, sowing, and harvesting activities. The authors also thank technicians Uber Castro and Juan Román from the Arequipa Agricultural Experimental Station (EEA Arequipa) for their support in irrigation management at the experimental fields. They also thank the National Institute of Agrarian Innovation (INIA) for providing the institutional framework and logistical support for this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMMI | Additive Main Effects and Multiplicative Interaction |

| ASV | AMMI Stability Value |

| CIMMYT | International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center |

| EEA | Agricultural Experiment Station |

| ENV | Environment |

| G × E | Genotype × Environment interaction |

| GEN | Genotype |

| GGE | Genotype and Genotype × Environment interaction |

| INIA | National Institute for Agricultural Innovation |

| PC1/PC2 | First/Second Principal Component |

| RCBD | Randomized Complete Block Design |

| SENAMHI | National Service of Meteorology and Hydrology of Peru |

| WAAS | Weighted Average of Absolute Scores |

| WAASBY | Weighted Average of Absolute Scores and Mean Performance Index |

References

- Khalid, A.; Hameed, A.; Tahir, M.F. Wheat Quality: A Review on Chemical Composition, Nutritional Attributes, Grain Anatomy, Types, Classification, and Function of Seed Storage Proteins in Bread Making Quality. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1053196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastrangelo, A.M.; Cattivelli, L. What Makes Bread and Durum Wheat Different? Trends Plant Sci. 2021, 26, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafiandra, D.; Sestili, F.; Sissons, M.; Kiszonas, A.; Morris, C.F. Increasing the Versatility of Durum Wheat through Modifications of Protein and Starch Composition and Grain Hardness. Foods 2022, 11, 1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoun, M.; Boukid, F. Novel Quality Features to Expand Durum Wheat Applications. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2023, 103, 4268–4274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakir, S.; Ahmad, S.; Naz, A.; Raza, N. Nutritional Aspects of Durum Wheat. In Bioactive Compounds from Multifarious Natural Foods for Human Health; Apple Academic Press: Palm Bay, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 21–41. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Moreno, F.; Ammar, K.; Solís, I. Global Changes in Cultivated Area and Breeding Activities of Durum Wheat from 1800 to Date: A Historical Review. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceglar, A.; Toreti, A.; Zampieri, M.; Royo, C. Global Loss of Climatically Suitable Areas for Durum Wheat Growth in the Future. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 104049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, A.; Gupta, V.; Tripathy, P.P. Exploring Compositional and Technological Strategies to Enhance the Quality of Millet-Based Bread: An Overview of Current and Prospective Outlooks. Food Rev. Int. 2025, 41, 1771–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramburu Merlos, F.; Monzon, J.P.; Mercau, J.L.; Taboada, M.; Andrade, F.H.; Hall, A.J.; Jobbagy, E.; Cassman, K.G.; Grassini, P. Potential for Crop Production Increase in Argentina through Closure of Existing Yield Gaps. Field Crops Res. 2015, 184, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro Angeles, O.F.; Diez Matallana, R.A.; Gómez Oscorima, R.M.; Leyva Pedraza, T.A. Factors of Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Production in Peru. Period 1960–2021. Rev. Latinoam. Cienc. Soc. Humanidades 2005, 6, 555–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesesse, C.A.; Nigir, B.; de Sousa, K.; Gianfranceschi, L.; Gallo, G.R.; Poland, J.; Kidane, Y.G.; Desta, E.A.; Fadda, C.; Pè, M.E.; et al. Genomics-Driven Breeding for Local Adaptation of Durum Wheat Is Enhanced by Farmers’ Traditional Knowledge. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2205774119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, W.; Sanchez-Garcia, M.; Gizaw, S.; Amri, A.; Bishaw, Z.; Ogbonnaya, F.; Baum, M. Genetic Gains in Wheat Breeding and Its Role in Feeding the World. Crop Breed. Genet. Genom. 2019, 1, e190005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkowiak, S.; Pozniak, C.J.; Nilsen, K.T. Recent Advances in Sequencing of Cereal Genomes. In Accelerated Breeding of Cereal Crops; Bilichak, A., Laurie, J.D., Eds.; Springer Protocols Handbooks; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenegro, J.D.; Golicz, A.A.; Bayer, P.E.; Hurgobin, B.; Lee, H.T.; Chan, C.K.K.; Visendi, P.; Lai, K.; Doležel, J.; Batley, J.; et al. The Pangenome of Hexaploid Bread Wheat. Plant J. 2017, 90, 1007–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Park, H.-M.; Lee, S.-G.; Kim, E.-H.; Imran, M.; Choi, H.; Kim, M.-J.; Oh, S. Current Trends in Wheat Breeding Strategies for Developing Domestic Wheat Cultivars in Korea. Korean Soc. Breed. Sci. 2024, 56, 491–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saieed, M.A.U.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, K.; Rahman, S.; Zhang, J.; Islam, S.; Ma, W. Phenotypic Plasticity of Yield and Yield-Related Traits Contributing to the Wheat Yield in a Doubled Haploid Population. Plants 2024, 13, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poudel, M.R.; Neupane, M.; Kushwaha, U.K.S.; Lamshal, N.; Solanki, P. Expression and Performance of Nepalese Wheat Genotypes under Irrigated and Multiple Abiotic Stress Conditions. Agric. Sci. Dig. 2025, 45, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, K.; Arrowsmith, N.; Gladis, T. Agrobiodiversity with Emphasis on Plant Genetic Resources. Naturwissenschaften 2003, 90, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, M.P.; Lewis, J.M.; Ammar, K.; Basnet, B.R.; Crespo-Herrera, L.; Crossa, J.; Dhugga, K.S.; Dreisigacker, S.; Juliana, P.; Karwat, H.; et al. Harnessing Translational Research in Wheat for Climate Resilience. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 5134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, H.; Bhandari, R.; Dhakal, A.; Nyaupane, S.; Panthi, B.; Ram Poudel, M. Response of Wheat to Different Abiotic Stress Conditions: A Review. Sci. Herit. J. GWS 2023, 7, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cséplő, M.; Puskás, K.; Vida, G.; Bencze, S.; Veisz, O. Performance of a Durum Wheat Diversity Panel under Different Management Systems. Cereal Res. Commun. 2025, 53, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchetat, F.; Ghanai, R.; Himour, S.; Bouaroudj, S.; Benfkih, L.A. Effect of Genotype by Environment Interactions on Quality Parameters and Grain Yield of Durum Wheat. Biodiversitas 2023, 24, 5565–5571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, R.; Roostaei, M.; Armion, M.; Abdipour, M.; Rahmati, M.; Shahbazi, K. Deciphering Genotype × Environment Interaction for Grain Yield in Durum Wheat: An Integration of Analytical and Empirical Approaches for Increased Yield Stability and Adaptability. Eur. J. Agron. 2025, 168, 127656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omrani, A.; Omrani, S.; Shojaei, S.H.; Holasou, H.A.; Türkoğlu, A.; Afzalifar, A. Analyzing Wheat Productivity: Using GGE Biplot and Machine Learning to Understand Agronomic Traits and Yield. Cereal Res. Commun. 2024, 53, 1861–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jędzura, S.; Bocianowski, J.; Matysik, P. The AMMI Model Application to Analyze the Genotype–Environmental Interaction of Spring Wheat Grain Yield for the Breeding Program Purposes. Cereal Res. Commun. 2023, 51, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neina, D. The Role of Soil PH in Plant Nutrition and Soil Remediation. Appl. Environ. Soil Sci. 2019, 2019, 5794869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molua, C.O. Investigating the Influence of Soil Electrical Conductivity on Crop Yield for Precision Agriculture Advancements. Int. J. Agric. Anim. Prod. 2021, 1, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.E.; Ali, G.A.; Gillespie, A.W.; Wagner-Riddle, C. Soil Organic Matter as Catalyst of Crop Resource Capture. Front. Environ. Sci. 2020, 8, 539141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Jabeen, N.; Farruhbek, R.; Chachar, Z.; Laghari, A.A.; Chachar, S.; Ahmed, N.; Ahmed, S.; Yang, Z. Enhancing Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Agriculture by Integrating Agronomic Practices and Genetic Advances. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1543714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muindi, E.M. Understanding Soil Phosphorus. Int. J. Plant Soil Sci. 2019, 31, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Du, X.; Wang, F.; Sha, J.; Chen, Q.; Tian, G.; Zhu, Z.; Ge, S.; Jiang, Y. Effects of Potassium Levels on Plant Growth, Accumulation and Distribution of Carbon, and Nitrate Metabolism in Apple Dwarf Rootstock Seedlings. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 534048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CIMMYT. From Agronomic Data to Farmer Recommendations: An Economics Training Manual, Rev. ed.; International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center: Mexico, Mexico, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- American Association of Cereal Chemists (AACC). Approved Methods of Analysis. Available online: https://www.cerealsgrains.org/resources/methods/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Zafar, S.; Hasnain, Z.; Danish, S.; Battaglia, M.L.; Fahad, S.; Ansari, M.J.; Alharbi, S.A. Modulations of Wheat Growth by Selenium Nanoparticles under Salinity Stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishwas, K.C.; Poudel, M.R.; Regmi, D. AMMI and GGE Biplot Analysis of Yield of Different Elite Wheat Line under Terminal Heat Stress and Irrigated Environments. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari Nazarabadi, T.; Asghar Nasrollahnejad Ghomi, A.; Kordenaeej, A.; Zainalinezhad, K. Stability Analysis of Advanced Bread Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Lines Using AMMI Method. J. Plant Prod. Res. 2022, 29, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ashkar, I. Multivariate Analysis Techniques and Tolerance Indices for Detecting Bread Wheat Genotypes of Drought Tolerance. Diversity 2024, 16, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]